Submitted:

17 January 2025

Posted:

17 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Strains and culture condition

2.2. Molecular characterization of the yeast isolate

2.3. Probiotic Evaluation of the K. marxianus isolate

2.3.1. Growth at 37 °C

2.3.2. Acid and Bile Salt Tolerance

2.3.3. Auto-Aggregation Capacity

2.3.4. Hydrophobicity Assay

2.3.5. Antioxidant Activity

2.3.6. Assessment of biofilm formation

2.3.7. A-431 cells

2.3.8. Adhesion to A-431 cells

2.4. Safety Assessment of the K. marxianus isolate

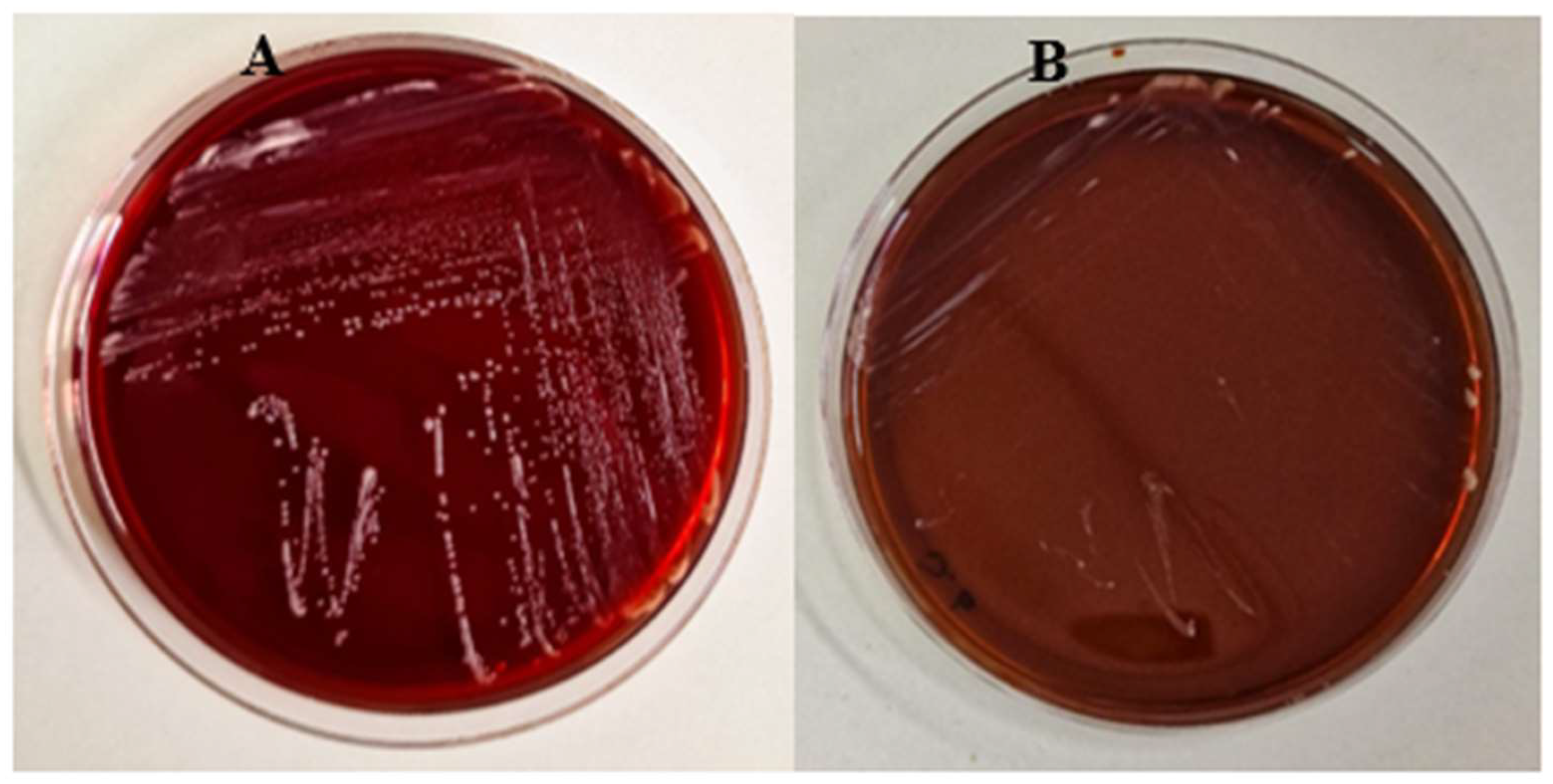

2.4.1. Haemolytic activity

2.4.2. Antibiotic and antifungal resistance

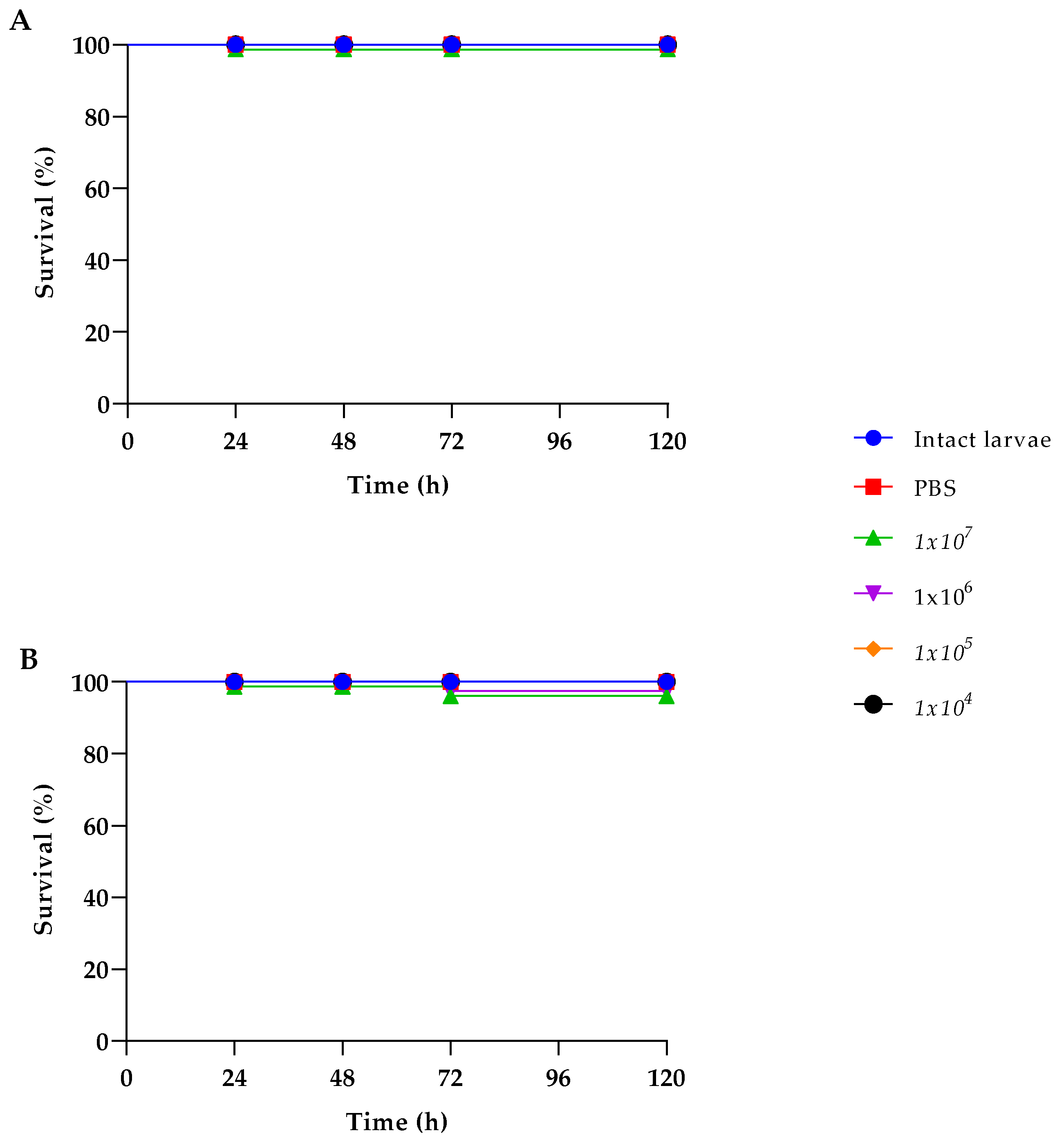

2.4.3. Galleria mellonella survival assay

2.5. Anticandidal activity of the K. marxianus isolate

2.5.1. Co-aggregation of K. marxianus with C. albicans

2.5.2. Exclusion test

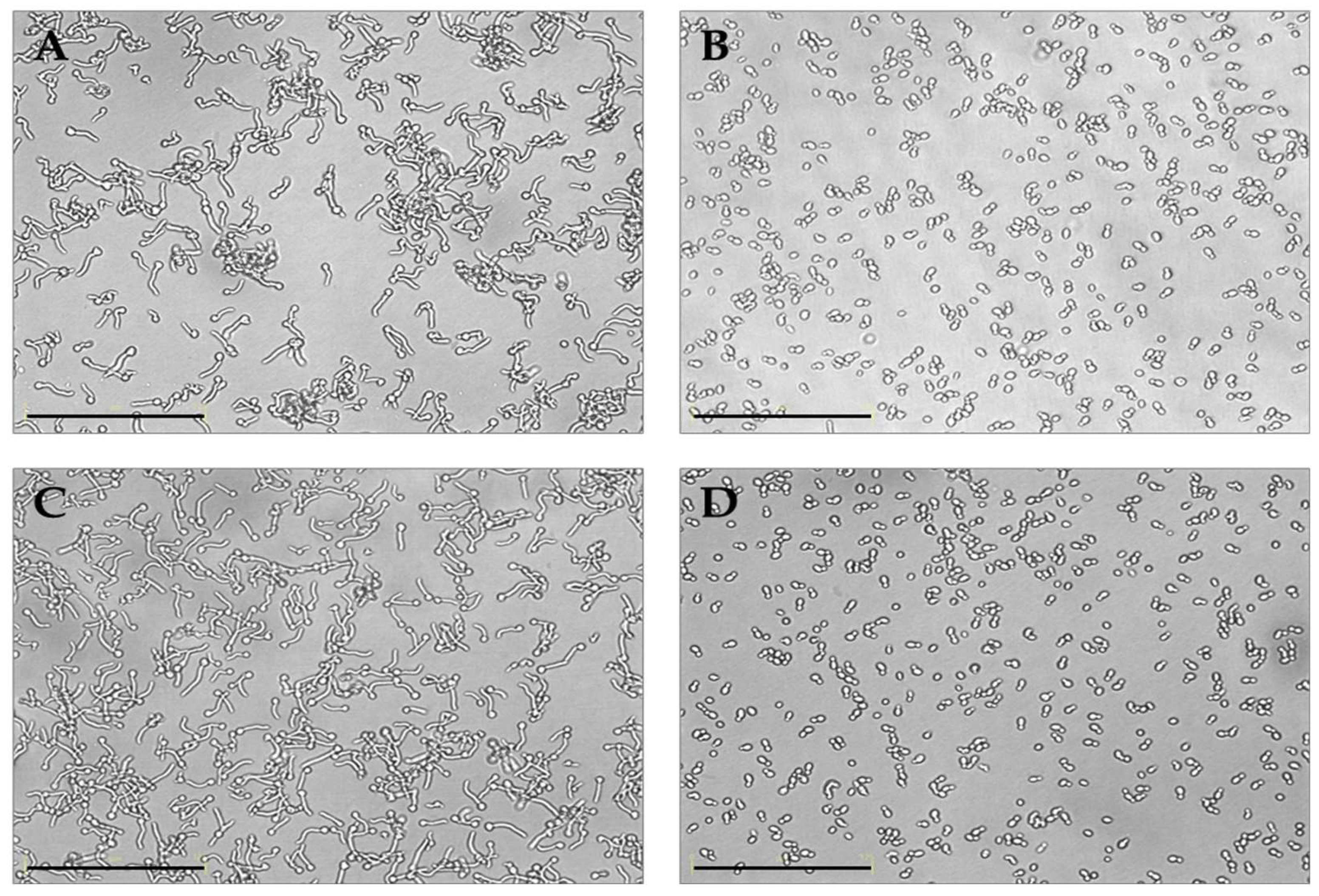

2.5.3. Germ tube test in the presence of K. marxianus

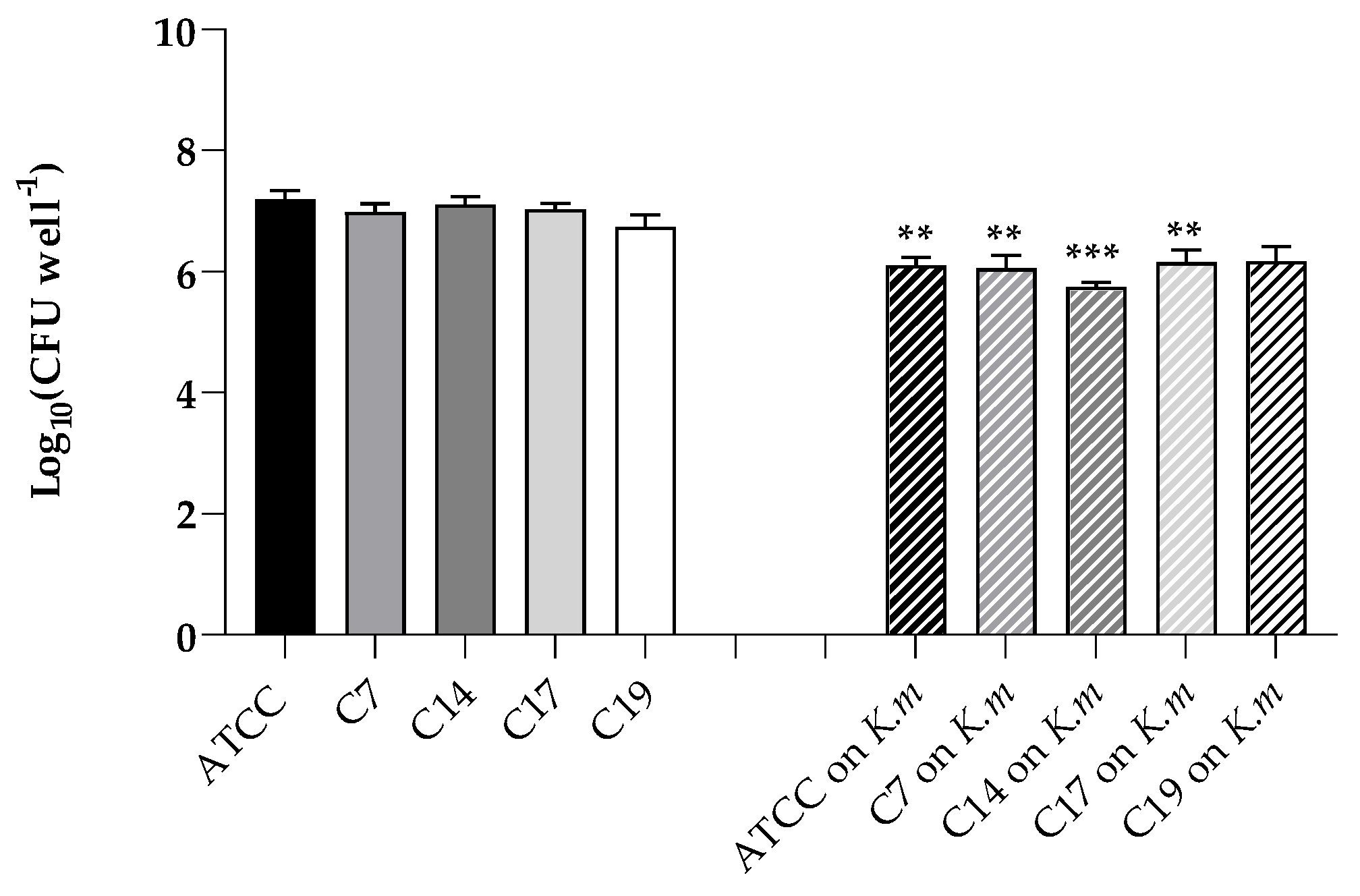

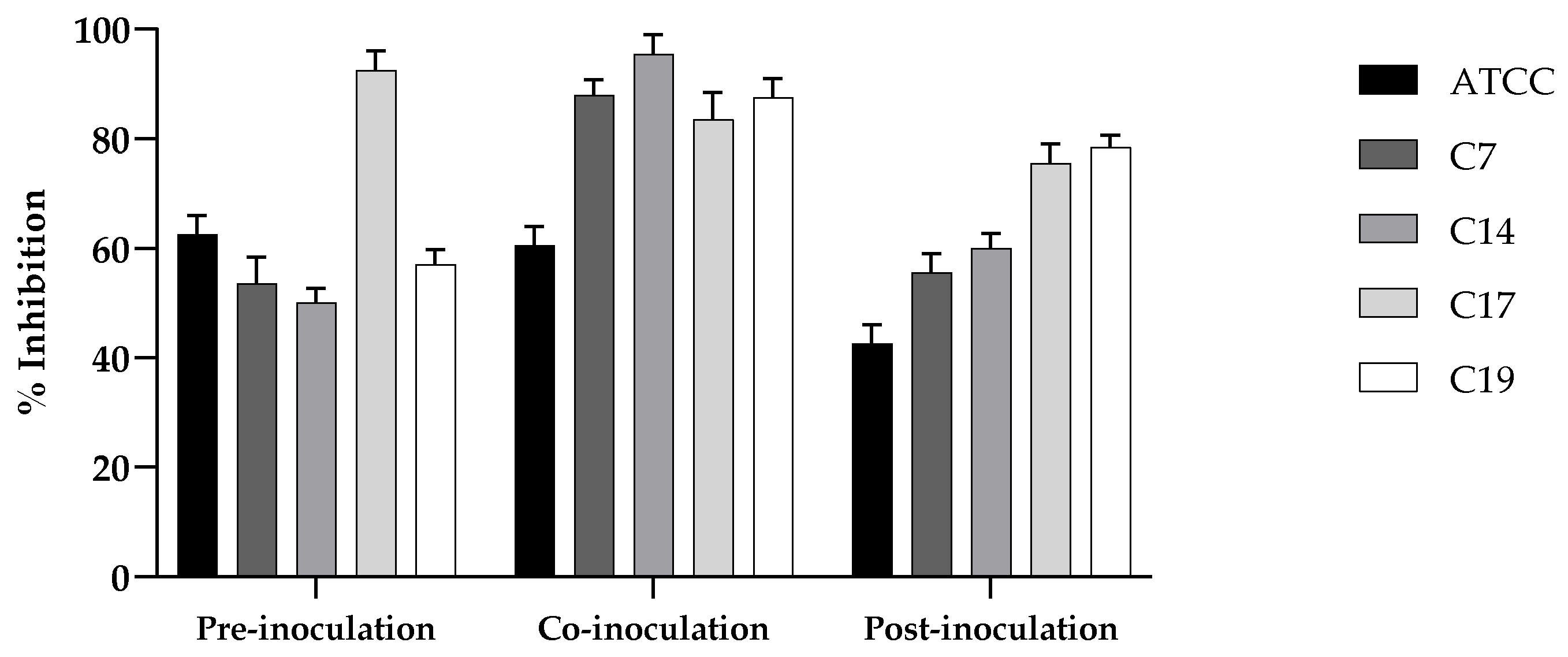

2.5.4. Adhesion of C- albicans to A-431 cells in the presence of K. marxianus

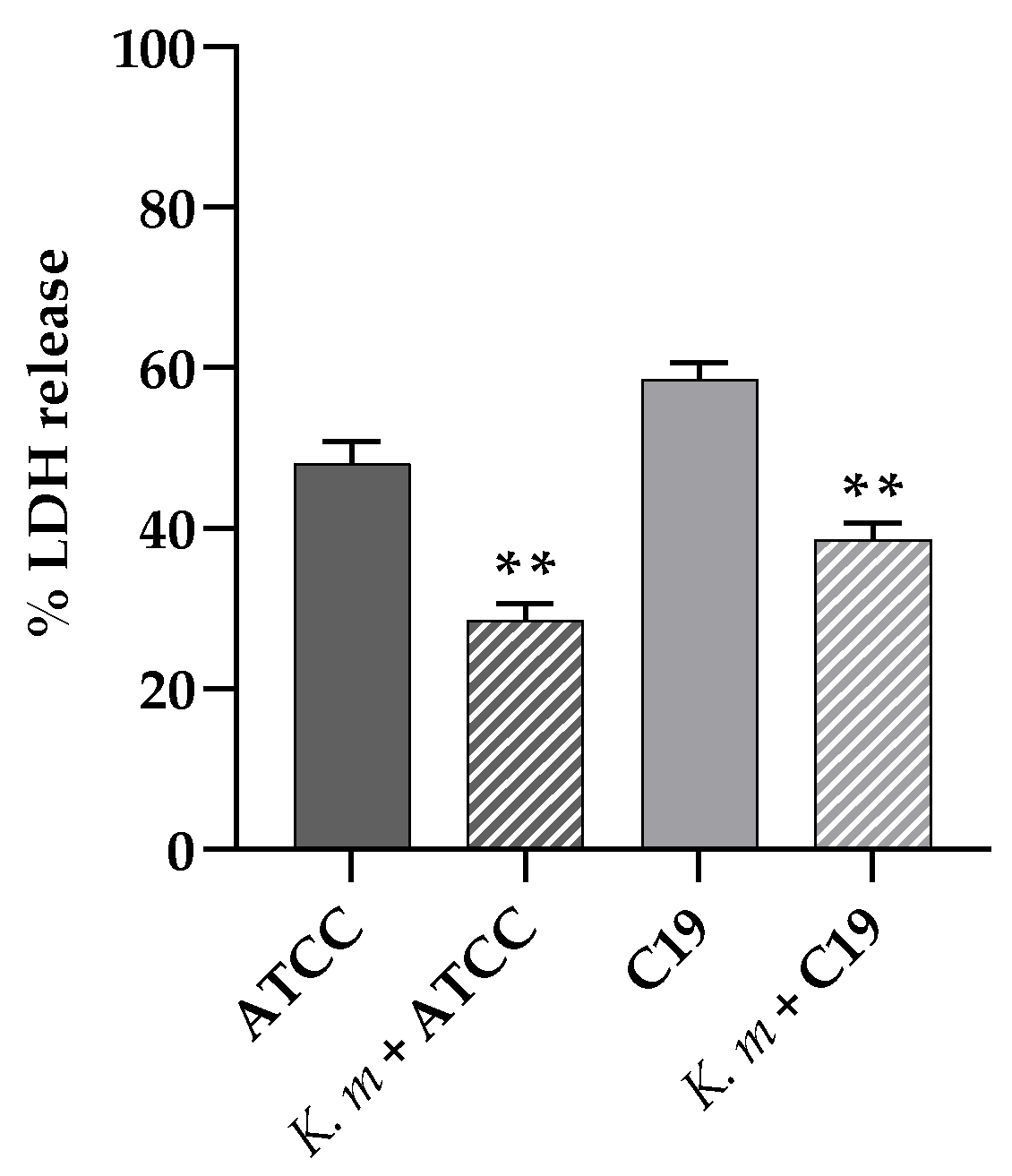

2.5.5. Cell damage: LDH determination

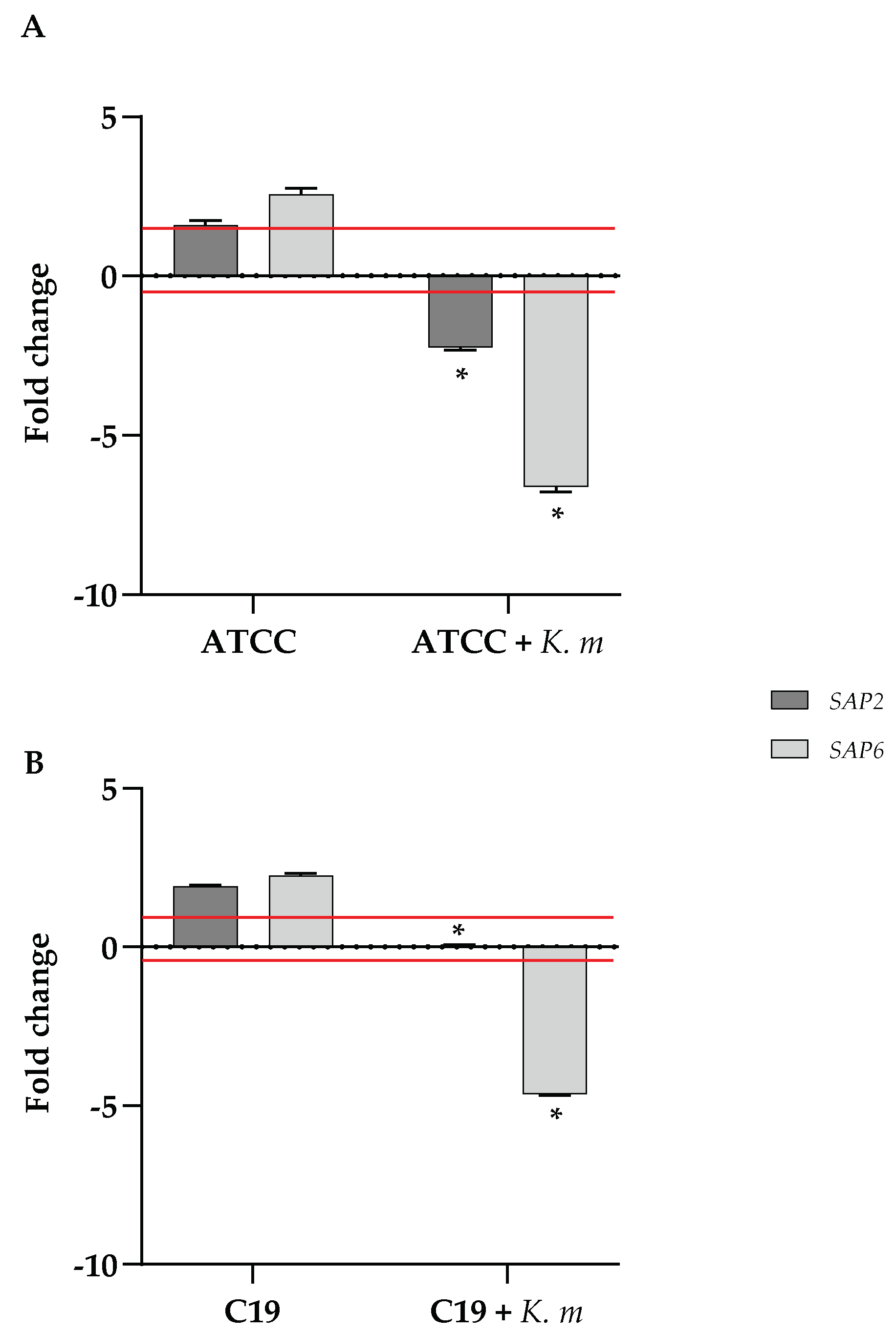

2.5.6. Quantitative analysis of SAP2 and SAP6 gene expression

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Isolation and molecular characterization of K. marxianus isolate

3.2. Probiotic properties of the K. marxianus isolate

3.3. Safety assessment

3.4. Anticandidal activity of K. marxianus

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hatoum, R.; Labrie, S.; Fliss, I. Antimicrobial and probiotic properties of yeasts: from fundamental to novel applications. Front Microbiol 2012, 3, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.-F.; Hsia, K.-C.; Kuo, Y.-W.; Chen, S.-H.; Huang, Y.-Y.; Li, C.-M.; Hsu, Y.-C.; Tsai, S.-Y.; Ho, H.-H. Safety Assessment and Probiotic Potential Comparison of Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis BLI-02, Lactobacillus plantarum LPL28, Lactobacillus acidophilus TYCA06, and Lactobacillus paracasei ET-66. Nutrients 2024, 16, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryabtseva, S.A.; Khramtsov, A.G.; Sazanova, S.N.; Budkevich, R.O.; Fedortsov, N.M.; Veziryan, A.A. The Probiotic Properties of Saccharomycetes (Review). Applied Biochemistry and Microbiology 2023, 59, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pais, P.; Almeida, V.; Yılmaz, M.; Teixeira, M.C. Saccharomyces boulardii: What Makes It Tick as Successful Probiotic? Journal of Fungi 2020, 6, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghi, A.; Ebrahimi, M.; Shahryari, S.; Kharazmi, M.S.; Jafari, S.M. Food applications of probiotic yeasts; focusing on their techno-functional, postbiotic and protective capabilities. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2022, 128, 278–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shruthi, B.; Deepa, N.; Somashekaraiah, R.; Adithi, G.; Divyashree, S.; Sreenivasa, M.Y. Exploring biotechnological and functional characteristics of probiotic yeasts: A review. Biotechnology Reports 2022, 34, e00716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denning, D.W.; Kneale, M.; Sobel, J.D.; Rautemaa-Richardson, R. Global burden of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis 2018, 18, e339–e347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinosoglou, K.; Schinas, G.; Polyzou, E.; Tsiakalos, A.; Donders, G.G.G. Probiotics in the Management of Vulvovaginal Candidosis. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2024, 13, 5163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pericolini, E.; Gabrielli, E.; Ballet, N.; Sabbatini, S.; Roselletti, E.; Cayzeele Decherf, A.; Pélerin, F.; Luciano, E.; Perito, S.; Jüsten, P.; et al. Therapeutic activity of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae-based probiotic and inactivated whole yeast on vaginal candidiasis. Virulence 2017, 8, 74–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabrielli, E.; Pericolini, E.; Ballet, N.; Roselletti, E.; Sabbatini, S.; Mosci, P.; Decherf, A.C.; Pélerin, F.; Perito, S.; Jüsten, P.; et al. Saccharomyces cerevisiae-based probiotic as novel anti-fungal and anti-inflammatory agent for therapy of vaginal candidiasis. Beneficial Microbes 2018, 9, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunyeit, L.; Kurrey, N.K.; Anu-Appaiah, K.A.; Rao, R.P. Probiotic Yeasts Inhibit Virulence of Non<i>-albicans Candida</i> Species. mBio 2019, 10, 10.1128–mbio.02307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomičić, R.; Tomičić, Z.; Raspor, P. Influence of culture conditions on co-aggregation of probiotic yeast Saccharomyces boulardii with Candida spp. and their auto-aggregation. Folia Microbiologica 2022, 67, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Y.-J.; Kim, D.-H.; Jeong, D.; Seo, K.-H.; Jeong, H.S.; Lee, H.G.; Kim, H. Characterization of yeasts isolated from kefir as a probiotic and its synergic interaction with the wine byproduct grape seed flour/extract. LWT 2018, 90, 535–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, H.; Xiong, L.; Gao, X.; Jia, H.; Lian, Z.; Tong, N.; Han, T. Hypocholesterolemic effects of Kluyveromyces marxianus M3 isolated from Tibetan mushrooms on diet-induced hypercholesterolemia in rat. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology 2015, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saber, A.; Alipour, B.; Faghfoori, Z.; Yari Khosroushahi, A. Secretion metabolites of dairy Kluyveromyces marxianus AS41 isolated as probiotic, induces apoptosis in different human cancer cell lines and exhibit anti-pathogenic effects. Journal of Functional Foods 2017, 34, 408–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadda, M.E.; Mossa, V.; Deplano, M.; Pisano, M.B.; Cosentino, S. In vitro screening of Kluyveromyces strains isolated from Fiore Sardo cheese for potential use as probiotics. LWT 2017, 75, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccaferri, S.; Klinder, A.; Brigidi, P.; Cavina, P.; Costabile, A. Potential probiotic Kluyveromyces marxianus B0399 modulates the immune response in Caco-2 cells and peripheral blood mononuclear cells and impacts the human gut microbiota in an in vitro colonic model system. Appl Environ Microbiol 2012, 78, 956–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceugniez, A.; Drider, D.; Jacques, P.; Coucheney, F. Yeast diversity in a traditional French cheese “Tomme d'orchies” reveals infrequent and frequent species with associated benefits. Food Microbiology 2015, 52, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceugniez, A.; Coucheney, F.; Jacques, P.; Daube, G.; Delcenserie, V.; Drider, D. Anti-Salmonella activity and probiotic trends of Kluyveromyces marxianus S-2-05 and Kluyveromyces lactis S-3-05 isolated from a French cheese, Tomme d'Orchies. Research in Microbiology 2017, 168, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- l-Qaysi SAS, A.N. , Jaffer MR, Abbas ZA. Biological Control of Phytopathogenic Fungi by Kluyveromyces marxianus and Torulaspora delbrueckii Isolated from Iraqi Date Vinegar. Journal of Pure and Applied Microbiology 2021, 15(1), 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, A.M.; Albuini, F.M.; Barros, G.C.; Pereira, O.L.; da Silveira, W.B.; Fietto, L.G. Identification of the main proteins secreted by Kluyveromyces marxianus and their possible roles in antagonistic activity against fungi. FEMS Yeast Res 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goktas, H.; Dikmen, H.; Demirbas, F.; Sagdic, O.; Dertli, E. Characterisation of probiotic properties of yeast strains isolated from kefir samples. International Journal of Dairy Technology 2021, 74, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maione, A.; Imparato, M.; Buonanno, A.; Carraturo, F.; Schettino, A.; Schettino, M.T.; Galdiero, M.; de Alteriis, E.; Guida, M.; Galdiero, E. Anti-Biofilm Activity of Phenyllactic Acid against Clinical Isolates of Fluconazole-Resistant Candida albicans. Journal of Fungi 2023, 9, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salbitani, G.; Chianese, M.R.; Bossa, R.; Bencivenga, T.; Carraturo, F.; Nappo, A.; Guida, M.; Loreto, F.; Carfagna, S. Cultivation of barley seedlings in a coffee silverskin-enriched soil: effects in plants and in soil. Plant and Soil 2024, 498, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korabečná, M.; Liška, V.; Fajfrlík, K. PrimersITS1, ITS2 andITS4 detect the intraspecies variability in the internal transcribed spacers and 5.8S rRNA gene region in clinical isolates of fungi. Folia Microbiologica 2003, 48, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maione, A.; Imparato, M.; Buonanno, A.; Salvatore, M.M.; Carraturo, F.; de Alteriis, E.; Guida, M.; Galdiero, E. Evaluation of Potential Probiotic Properties and In Vivo Safety of Lactic Acid Bacteria and Yeast Strains Isolated from Traditional Home-Made Kefir. Foods 2024, 13, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SYAL P., V. A. PROBIOTIC POTENTIAL OF YEASTS ISOLATED FROM TRADITIONAL INDIAN FERMENTED FOODS. International Journal of Microbiology Research 2013, 5, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchán, A.V.; Benito, M.J.; Galván, A.I.; Ruiz-Moyano Seco de Herrera, S. Identification and selection of yeast with functional properties for future application in soft paste cheese. LWT 2020, 124, 109173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maione, A.; Galdiero, E.; Cirillo, L.; Gambino, E.; Gallo, M.A.; Sasso, F.P.; Petrillo, A.; Guida, M.; Galdiero, M. Prevalence, Resistance Patterns and Biofilm Production Ability of Bacterial Uropathogens from Cases of Community-Acquired Urinary Tract Infections in South Italy. Pathogens 2023, 12, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- STEPANOVIĆ, S.; VUKOVIĆ, D.; HOLA, V.; BONAVENTURA, G.D.; DJUKIĆ, S.; ĆIRKOVIĆ, I.; RUZICKA, F. Quantification of biofilm in microtiter plates: overview of testing conditions and practical recommendations for assessment of biofilm production by staphylococci. APMIS 2007, 115, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Bai, X.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Q.; Bu, X.; Xu, Y.; Guo, N. Evaluation of the Potential Probiotic Yeast Characteristics with Anti-MRSA Abilities. Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins 2022, 14, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turchi, B.; Mancini, S.; Fratini, F.; Pedonese, F.; Nuvoloni, R.; Bertelloni, F.; Ebani, V.V.; Cerri, D. Preliminary evaluation of probiotic potential of Lactobacillus plantarum strains isolated from Italian food products. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2013, 29, 1913–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cisneros, L.; Cattelan, N.; Villalba, M.I.; Rodriguez, C.; Serra, D.O.; Yantorno, O.; Fadda, S. Lactic acid bacteria biofilms and their ability to mitigate Escherichia coli O157:H7 surface colonization. Lett Appl Microbiol 2021, 73, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wächtler, B.; Wilson, D.; Hube, B. Candida albicans Adhesion to and Invasion and Damage of Vaginal Epithelial Cells: Stage-Specific Inhibition by Clotrimazole and Bifonazole. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2011, 55, 4436–4439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naglik, J.R.; Moyes, D.; Makwana, J.; Kanzaria, P.; Tsichlaki, E.; Weindl, G.; Tappuni, A.R.; Rodgers, C.A.; Woodman, A.J.; Challacombe, S.J.; et al. Quantitative expression of the Candida albicans secreted aspartyl proteinase gene family in human oral and vaginal candidiasis. Microbiology 2008, 154, 3266–3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaffl, M.W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT–PCR. Nucleic Acids Research 2001, 29, e45–e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfaffl, M.W.; Horgan, G.W.; Dempfle, L. Relative expression software tool (REST©) for group-wise comparison and statistical analysis of relative expression results in real-time PCR. Nucleic Acids Research 2002, 30, e36–e36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giammarino, A.; Bellucci, N.; Angiolella, L. Galleria mellonella as a Model for the Study of Fungal Pathogens: Advantages and Disadvantages. Pathogens 2024, 13, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergara, S.C.; Leiva, M.J.; Mestre, M.V.; Vazquez, F.; Nally, M.C.; Maturano, Y.P. Non-saccharomyces yeast probiotics: revealing relevance and potential. FEMS Yeast Res 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karim, A.; Gerliani, N.; Aïder, M. Kluyveromyces marxianus: An emerging yeast cell factory for applications in food and biotechnology. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2020, 333, 108818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilal, M.; Ji, L.; Xu, Y.; Xu, S.; Lin, Y.; Iqbal, H.M.N.; Cheng, H. Bioprospecting Kluyveromyces marxianus as a Robust Host for Industrial Biotechnology. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2022, 10, 851768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziz Homayouni-Rad, A.A. , Parvin Oroojzadeh and Hadi Pourjafar. Kluyveromyces marxianus as a Probiotic Yeast: A Mini-review. Current Nutriotion & Food Science 2020, 16, 1163–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, D.; Goel, A.; Padwad, Y.; Singh, D. In Vitro Characterisation Revealed Himalayan Dairy Kluyveromyces marxianus PCH397 as Potential Probiotic with Therapeutic Properties. Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins 2023, 15, 761–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.; Reid, G. Distant Site Effects of Ingested Prebiotics. Nutrients 2016, 8, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perpetuini, G.; Tittarelli, F.; Suzzi, G.; Tofalo, R. Cell Wall Surface Properties of Kluyveromyces marxianus Strains From Dairy-Products. Front Microbiol 2019, 10, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motey, G.A.; Johansen, P.G.; Owusu-Kwarteng, J.; Ofori, L.A.; Obiri-Danso, K.; Siegumfeldt, H.; Larsen, N.; Jespersen, L. Probiotic potential of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Kluyveromyces marxianus isolated from West African spontaneously fermented cereal and milk products. Yeast 2020, 37, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Torrado, R.; Llopis, S.; Jespersen, L.; Fernández-Espinar, T.; Querol, A. Clinical Saccharomyces cerevisiae isolates cannot cross the epithelial barrier in vitro. Int J Food Microbiol 2012, 157, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moure, M.C.; Pérez Torrado, R.; Garmendia, G.; Vero, S.; Querol, A.; Alconada, T.; León Peláez, Á. Characterization of kefir yeasts with antifungal capacity against Aspergillus species. International Microbiology 2023, 26, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavanagh, K.; Fallon, J.P. Galleria mellonella larvae as models for studying fungal virulence. Fungal Biology Reviews 2010, 24, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, K.-D.; Le-Thi, L.; Vo, H.-H.; Dinh-Thi, T.-V.; Nguyen-Thi, T.; Phan, N.-H.; Nguyen, K.-U. Probiotic Properties and Safety Evaluation in the Invertebrate Model Host Galleria mellonella of the Pichia kudriavzevii YGM091 Strain Isolated from Fermented Goat Milk. Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins 2024, 16, 1288–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, J.V. Candida albicans Hyphae: From Growth Initiation to Invasion. Journal of Fungi 2018, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naglik, J.; Albrecht, A.; Bader, O.; Hube, B. Candida albicans proteinases and host/pathogen interactions. Cell Microbiol 2004, 6, 915–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Identified microrganism | Max score | Total score | Query Cover | e-value | % Identity | Accession N. |

| Kluyveromyces marxianus strain JYC2557 | 1223 | 1223 | 99% | 0.0 | 99.55% | MK044038.1 |

|

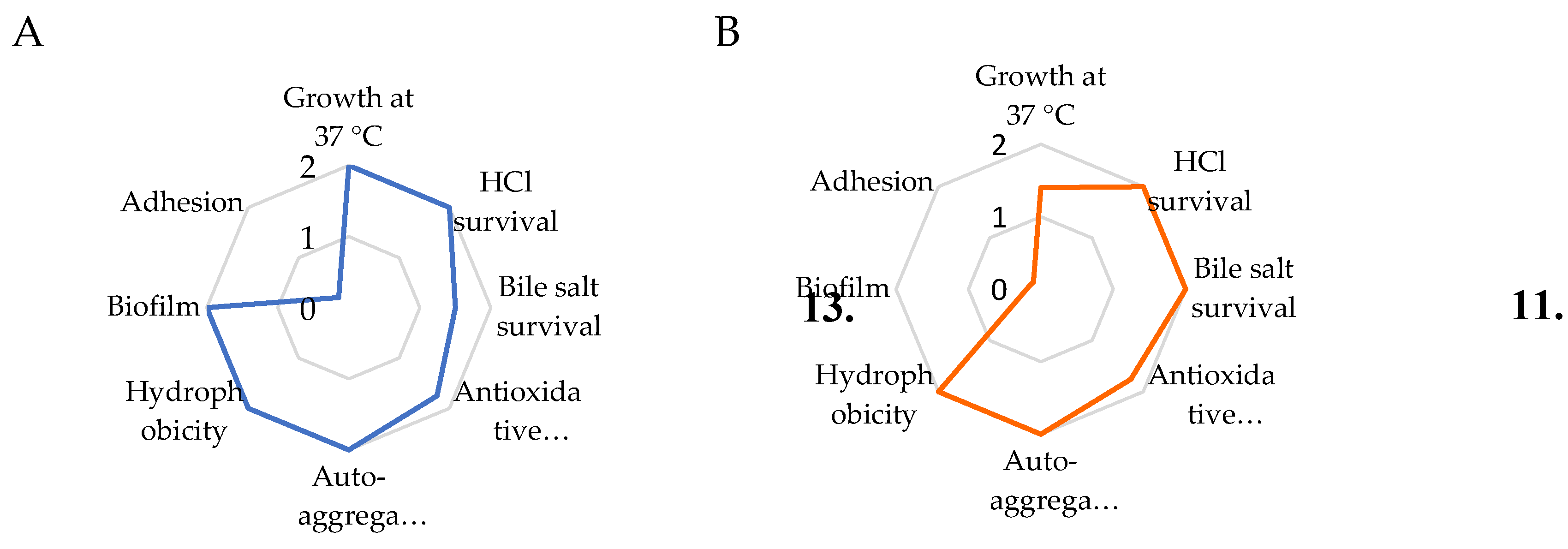

Growth at 37 °C |

HCl survival |

Bile salt survival | Antioxidative power |

Auto- aggregation |

Hydrophobicity | Biofilm | Adhesion | Total score | |

| (OD590) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (OD570) | (%) | ||

| Km | 6.86 | 100 | 73 | 78.5 | 100 | 90 | 4.5 | 10 | |

| 2 | 2 | 1.5 | 1.75 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.2 | 13.5 | |

| Sb | 4.93 | 100 | 98 | 77 | 100 | 81 | 0.3 | 2.35 | |

| 1.4 | 2 | 2 | 1.75 | 2 | 2 | 0.2 | 0.05 | 11.4 |

| GM | AMP | PB | AMC | NOR | STR | CTX | CIP | AZ | CRO | VAN | RIF | FLC | CSF | KET | ITR | AmphB | |

| Km | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | S | S | S | R | S |

| Sb | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | S | S | S | R | S |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).