1. Introduction

Ecosystem services (ES) refers to the benefits to human society obtained directly or indirectly from nature [

1]. ES are fundamental to sustaining life and promoting human well-being, providing critical benefits, such as air and water purification, climate regulation, and biodiversity support [

1,

2]. Natural resources can enhance human wellbeing; however, some human activities can also affect the natural environment [

3]. This interaction is particularly pronounced in protected areas such as national parks, which serve as key reservoirs of biodiversity and natural habitats. Palomo et al. [

4] have demonstrated that national parks and their buffer zones offer a diverse array of ecosystem services that benefit the surrounding lands. These areas support an ecological balance and offer recreational, cultural, and spiritual benefits to society.

Japan is renowned for its diverse and picturesque natural landscapes and hosts a network of national parks that are pivotal to its ecological conservation efforts. Japan’s national park system was established in 1931 through the passage of the National Park Law. Japan’s national parks are “regional” (

chiikisei) parks that can be designated by setting areas regardless of land ownership, and within the designated areas, various actions that alter the natural environment are regulated as actions that require permission or notification [

5]. In addition, various facilities have been developed as places to interact with nature. The Ministry of the Environment (MoE) has set up branch offices to handle various management tasks, including issuing permits and licenses. These parks play a dual role in preserving biodiversity and supporting substantial tourism. The ecological value of Japan’s national parks is immense, as they provide critical ecosystem services that contribute to environmental stability and resilience.

Economically, these parks are significant tourism destinations that attract millions of visitors annually and contribute to local and national economies. The Japanese government is working on the “Tourism Vision to Support Japan’s Future,” which aims to increase the number of foreign visitors to Japan to 60 million by 2030. National parks are positioned as one of the pillars of the “Tourism Vision to Support Japan’s Future,” which was compiled by the government in March 2016, and the “Project to Fully Enjoy National Parks” has been promoted (

https://www.env.go.jp/en/nature/enjoy-project/index.html). This project is targeting the branding of Japan’s National Parks as world-class National Parks and initially focused on eight selected national parks (the “Priority Eight Parks”) to implement pioneering and intensive initiatives. Nevertheless, an increase in visitor numbers can exacerbate ecological pressures, leading to issues such as increased waste in the community, habitat destruction, pollution, and a decline in biodiversity, ultimately impacting the provision of ecosystem services [

6,

7].

Quantifying ecosystem service value (ESV) and monitoring its changes are crucial for assessing the effectiveness of conservation efforts (Costanza et al., 1997) One of the efficient methods for this purpose is the benefit transfer method (BTM) is an efficient method for this purpose. The BTM is used to estimate the value of ES in one location or context by applying valuation data from a similar location or study. In a pioneering valuation study, Costanza et al. [

8] combined the unit area values of 17 ecosystem services across 16 ecosystem types with global distribution data to first attempt to estimate the global value of ecosystem services and natural capital. De Groot et al. [

9] updated the 1997 valuation by incorporating data from the Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB) Initiative. Costanza et al. [

10] estimated losses and gains in ecosystem services from 1997 to 2011. Therefore, these studies established favorable conditions for utilizing BTM to assess ESV. Changes in land use and land cover (LULC), driven by various factors, significantly influence ecosystem services [

11]. Based on these foundations, the value coefficients and adjusted coefficients combined with LULC change analysis are widely used in the value transfer method when estimating the ESV [

12,

13,

14,

15].

Remote sensing has been widely used in LULC classification, enabling the analysis of land cover changes over time [

16,

17]. Previous studies have employed remote sensing to map LULC classifications at the national park scale, providing evidence for further analysis of ESV changes in these areas [

18,

19,

20,

21].

Some studies have demonstrated how tourism can alter LULC and affect landscape and ecosystem functions. Research has indicated that the rise in tourism in Nepal’s national parks may be linked to observed LULC changes such as the expansion of built-up areas and a decline in forest cover [

22]. A study conducted in Bali found that tourism growth drove changes in LULC, and an increase in visitors encouraged the construction of tourism-related buildings. [

23]. Vijay et al. [

24] found that areas with rapid tourism growth also experienced a rapid expansion of built-up land, confirming the impact of tourism pressure on LULC. Despite advancements in assessing ESV dynamics based on LULC changes, a gap still exists in integrating the tourism context with ESV change analysis, particularly from a policy-driven perspective. As the “Project to Fully Enjoy National Parks” has been implemented in selected national parks in Japan, these policy-driven tourism initiatives may have influenced land use and, in turn, affected ecosystem services. However, current research frequently neglects the intersection of policy-driven tourism initiatives and environmental conservation strategies for ecosystem services. Addressing this gap is vital to develop comprehensive strategies that balance ecological preservation with socioeconomic development in Japan’s national parks and similar environments.

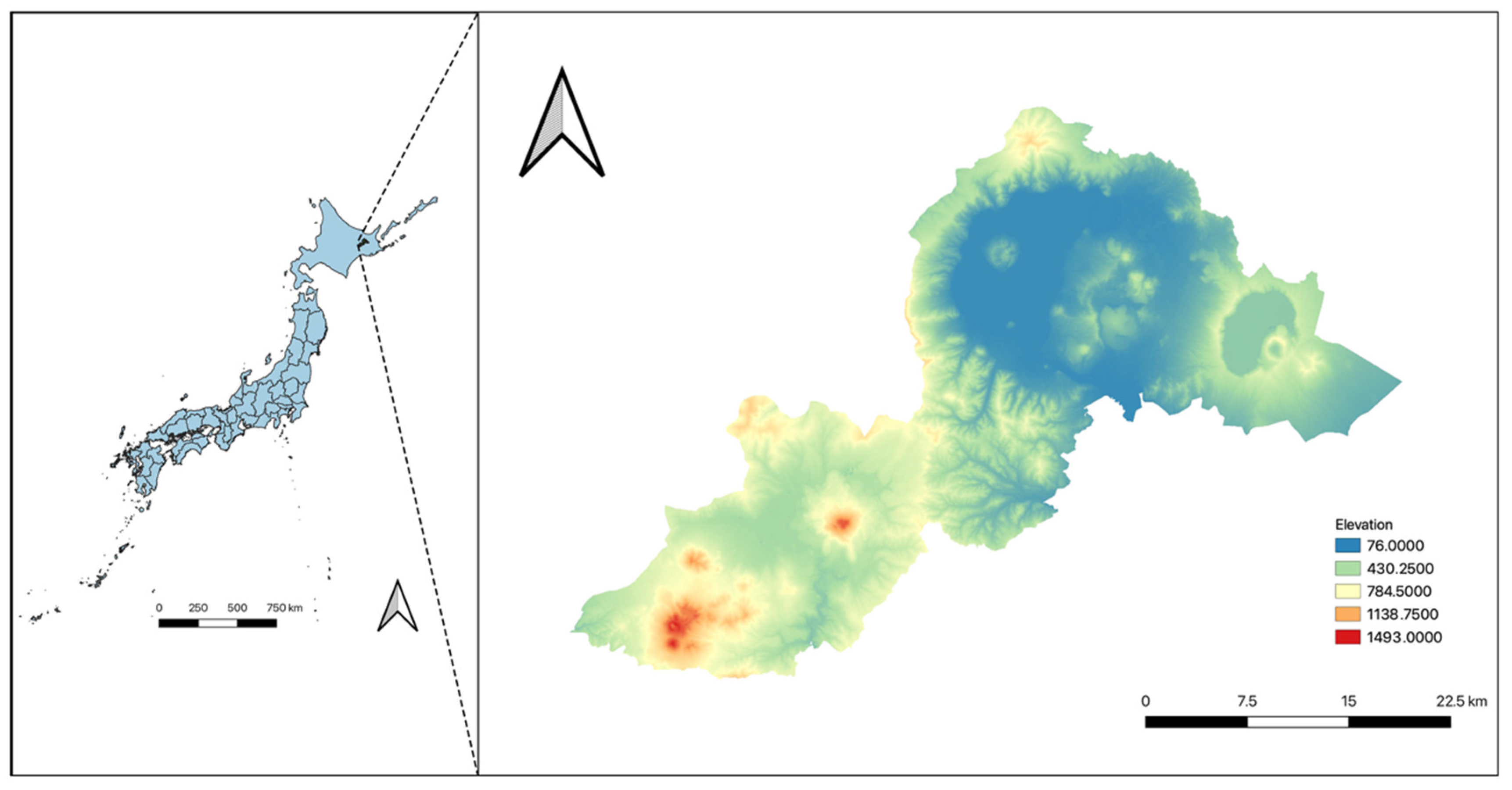

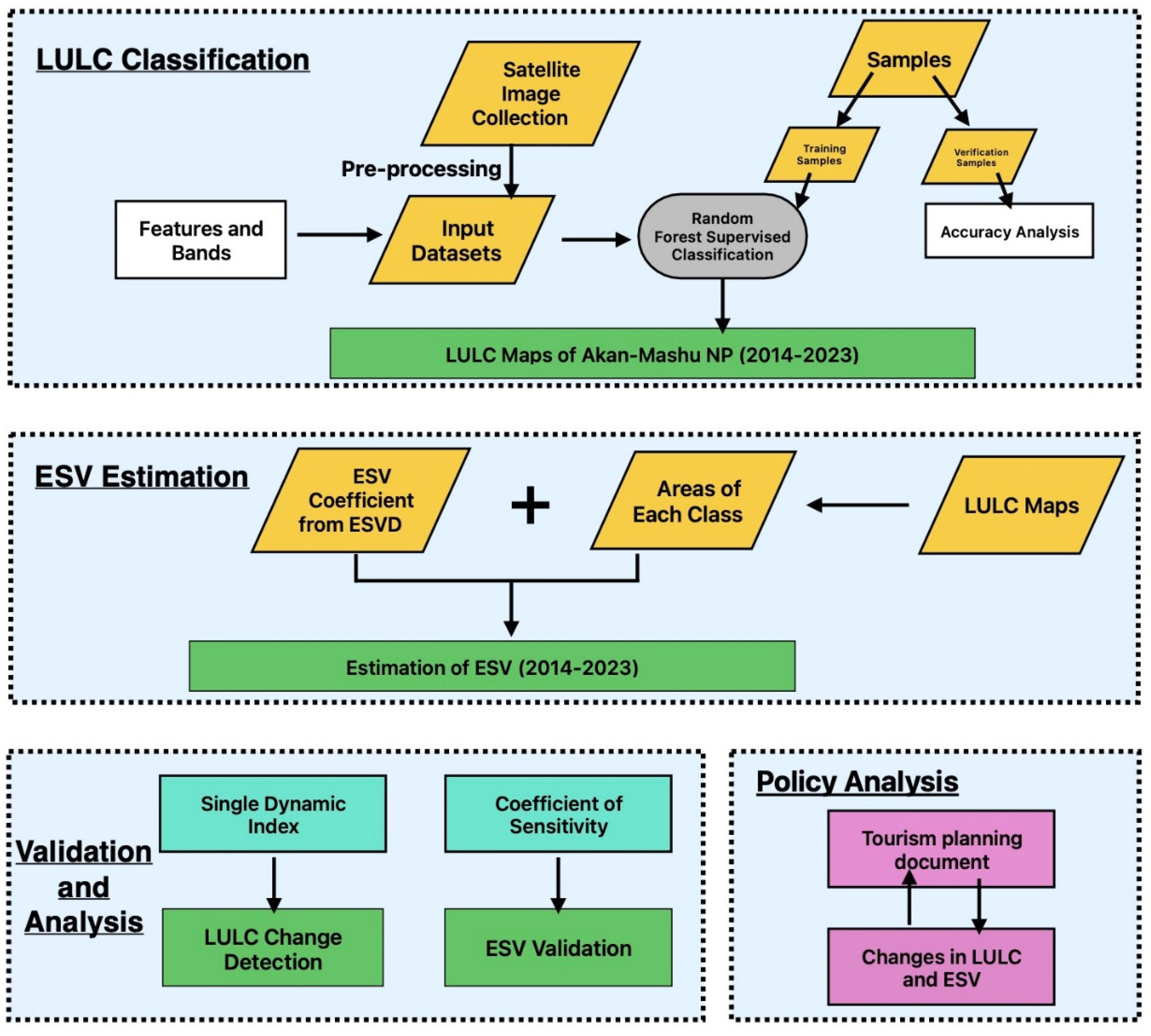

This interdisciplinary study aims to bridge these gaps by examining the interplay between tourism development, LULC changes, and ecosystem service values, providing a nuanced understanding of the socio-ecological dynamics within Japan’s national parks. Specifically, the research objectives of this study are: first, to map the LULC of Akan-Mashu National Park (one of the “Priority Eight Parks”) from 2014 to 2023 through remote sensing technology; second, to calculate the ESV for each year from 2014 to 2023 using the value transfer method; third, to explore the changes in LULC and ESV of national parks from the perspective of promoting tourism development in combination with the qualitative analysis of tourism planning policy documents; fourth, to propose future national park management recommendations based on the research results. As a baseline study, our research aims to verify the effectiveness of the policy and provide a scientific basis for the long-term monitoring and policy optimization of protected areas such as national parks.

4. Discussion

4.1. Changes of LULC

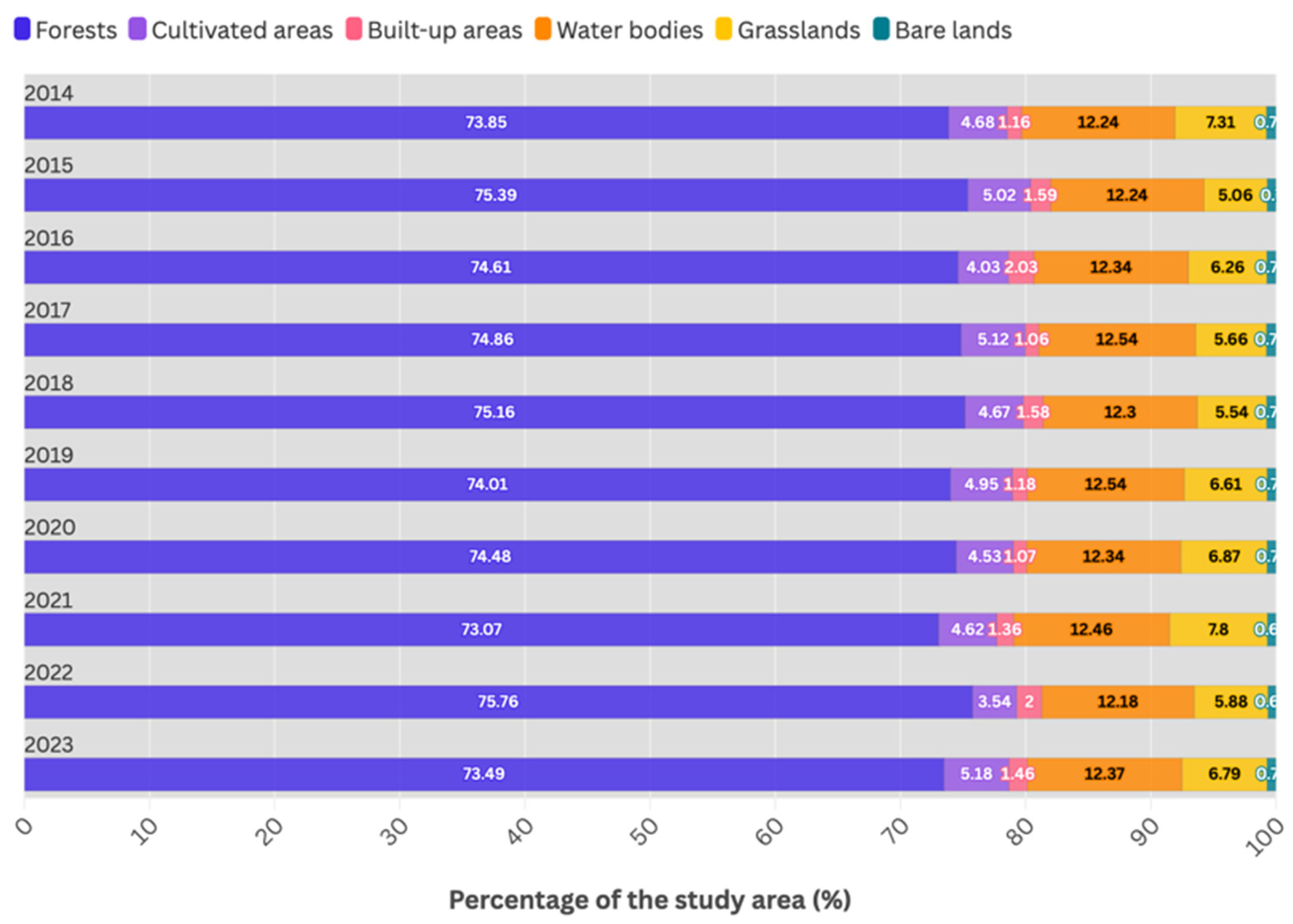

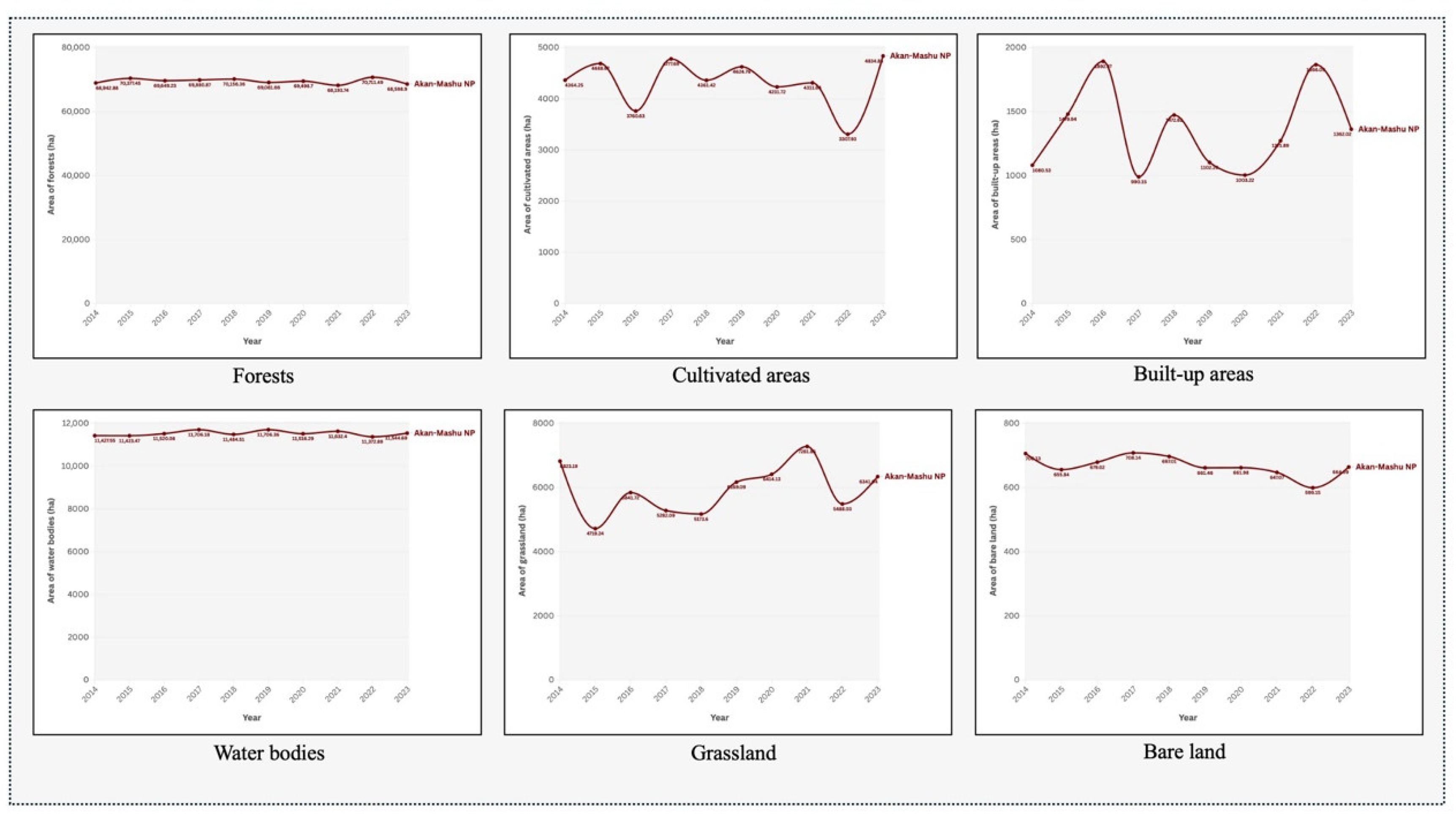

The LULC results of this study revealed that the land use type in the Akan-Mashu NP was dominated by forests, followed by water bodies and grasslands. Human activities engaged in land use types: Cultivated and built-up areas cover only a small portion of the study area. This result is consistent with the features of the NP, which has a magnificent landscape that weaves volcanoes, forests, and lakes together. Although the single dynamic index of forests decreased from 2014 to 2023, the absolute change was 0.06%, indicating almost no significant changes. Similar to forests, changes in water bodies, grasslands, and bare land were slow. The single dynamic indices of built-up areas (2.89%) and cultivated areas (1.20%) were relatively higher than those of the other land-use types. As of 2020, the management department has implemented numerous measures to attract tourists, as summarized in

Section 3.3. Among these measures, projects increase the construction area by opening and building new walking trails, viewing platforms, and parking lots. Previous studies have indicated a marked increase in abandoned farmland in Japan due to the substantial decline and aging of its rural population [

36,

37]. Our research showed that cultivated land within national parks has developed steadily over the past decade, with a steady increase from 2014 to 2023. This result may be because our study period was in the last decade and the coverage area was not large enough, which does not reflect the more significant phenomenon of farmland abandonment.

As summarized in

Table 1, most of the zoning in this area is classified as special zoning, which has several restrictions and regulations. Our findings regarding changes in LULC indicate that land use has not shifted significantly over the past decade, demonstrating the success of protection and management strategies.

4.2. Changes of ESV

Our results show that different land-use types contribute to different ESV. Although water bodies account for only approximately 12% of the total area of the national park, they provide more than 70% of the ESV, which shows the importance of this land use type in the overall ecosystem service. In particular, the three major lakes, Lake Akan, Lake Mashu, and Lake Kussharo, not only have supporting services, regulating services, and provide habitat functions for plants and animals but are also important scenic spots. According to the policy documents of the management department, there are artificial facilities, such as observation platforms and campsites, around the lakes. Therefore, we believe that the areas around the three major lakes need to focus on monitoring ecological changes and tourism pressure. Another interesting point is that although the proportions of grassland and cultivated areas in the total area are almost the same, cultivated areas can provide more ESV. The main reason for this was that the coefficient value represented by cultivated areas was larger than that of grassland. The coefficient table (

Table 4) shows that cultivated areas can provide objective regulation and cultural service values. However, because of the serious phenomenon of farmland abandonment in Japan, especially in remote areas such as Hokkaido and Kyushu [

36,

37], the area of cultivated land will gradually decrease in the future. This requires management departments and local town governments to make efforts to balance local agricultural development with the national park management.

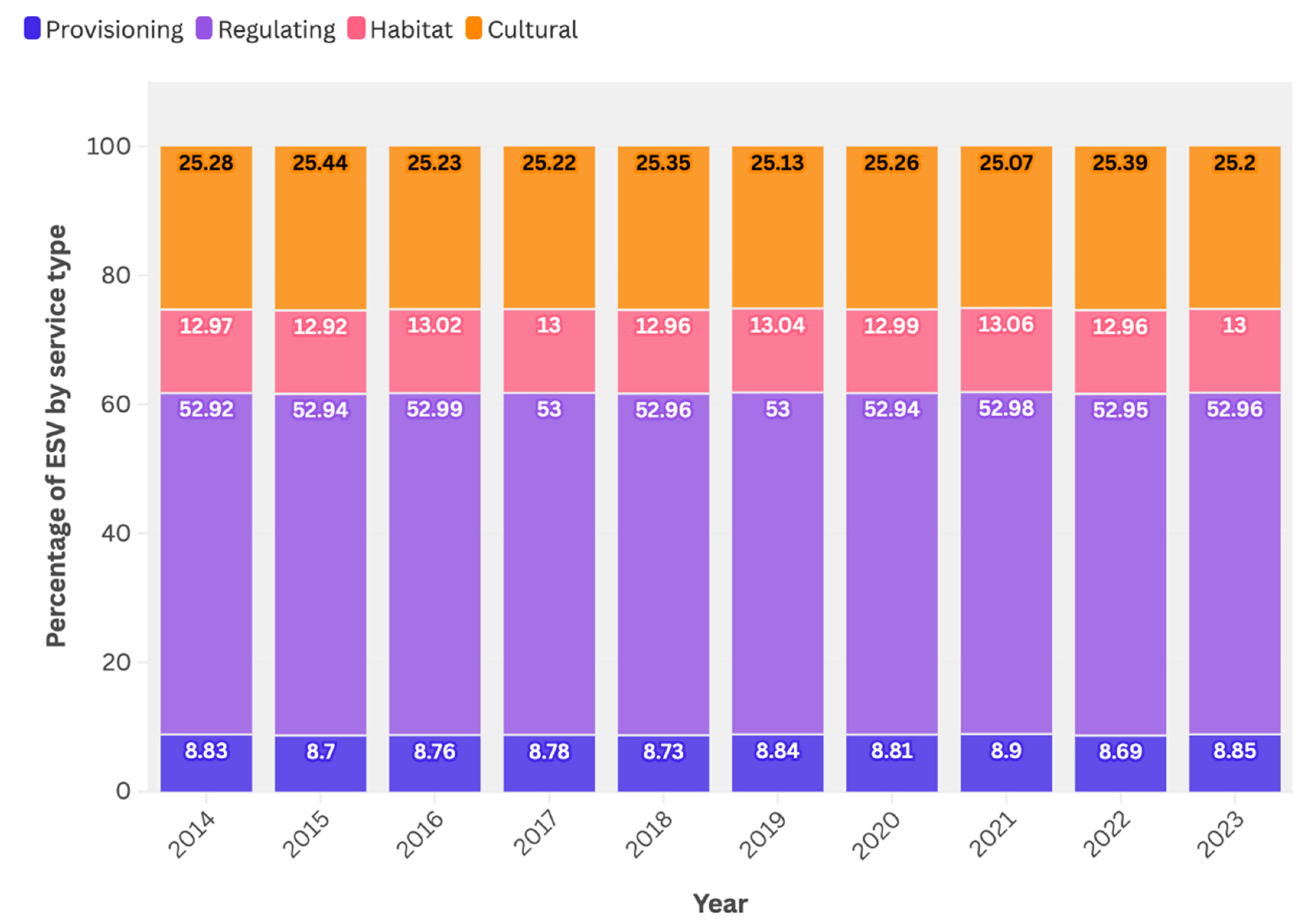

Among the four types of ecosystem services, the value provided by regulating services was the largest, which was consistent with the characteristics of the national park itself. It is a national park dominated by natural landscapes. Secondly, cultural services account for a considerable proportion of the population. Based on these results, we believe that national parks are ideal places for the development of AT and ecotourism.

From the time-series results of the ESV, the changes in the past decade have been very slow, and the overall ESV has increased by 13.85 million USD. Our research results reflect that management planning is very effective, and the plan to promote the development of tourism has not brought too much pressure and impact on the local land use type and ecological environment. Although our results showed minor changes in LULC and ESV, they do not imply that conservation efforts should be overlooked. Instead, a stable ecological state should promote the ongoing implementation of effective policies to sustain existing ecological service values.

4.3. Management Recommendations

Based on the main findings of this study, we propose several management recommendations for balancing ecological conservation and tourism development in national parks. We hope that these recommendations will not only apply to the subjects of this study—Japan’s national parks—but will also provide a reference for managing similar environments worldwide. First, our results validate the effectiveness of Japan’s national park zoning management system over the past decade. Zoning management systems should continue to be strictly followed in the future to ensure the ecological conservation of national parks. This recommendation is applicable globally, especially in developing countries such as China, which has recently begun to establish national parks. Second, we suggest that abandoned vacant lands or buildings in Akan-Mashu National Park be demolished and replaced with new tourism facilities. This approach would not occupy additional construction land and could enhance the area’s appeal and tourism experiences for visitors. Third, as summarized in

Section 3.3, national parks plan to conduct additional trials in the future. Given the region’s ecological fragility and referring to a previous study [

38], we recommend introducing a new “utilization zoning system, “ in addition to the existing zoning management system, to further optimize the coordination between human activities and ecological conservation. For example, for areas around lakes, management can establish various utilization rules depending on the ecological situation; these can be divided into areas for limited use with guides and areas that can accommodate mass tourism. Finally, by identifying the value share of different types of ecosystem services, we can provide a reference for future tourism planning goals of national parks. For instance, our research found differences in the proportion of value across different ecosystem services, with regulatory services having the highest proportion, followed by cultural services. This finding emphasizes the rationale for promoting the AT model in tourism planning policies. Considering that national parks integrate the natural environment with local cultural features, the AT model can better protect the local natural environment while attracting tourists. We believe that this strategy is not only suitable for the study area but can also be applied to other national parks. For instance, when cultural services have the highest proportion, management can use the local culture as the main feature to attract visitors.

4.4. Limitations and Future Research

This study has the following limitations. First, there are constraints related to data sources and accuracy. The temporal and spatial resolutions of remote sensing data may not be sufficient to accurately capture small-scale land-use changes. The ESV coefficients used in this study were based on comprehensive global assessments, which may not fully reflect the ecosystem characteristics of the study area. Secondly, there were limitations to the timescale. Since this study is an interdisciplinary project focusing on changes in LULC and ESV in Japan’s national parks after the implementation of the “To Fully Enjoy National Parks” project, only data from the past ten years were obtained, rather than a longer period. However, LULC and ESV changes may have been influenced by historical land use and management practices over a longer period. Third, this study did not integrate socioeconomic dimensions. This research mainly focuses on the ecological dimensions of LULC and ESV, potentially overlooking the interrelationship between tourism development and socioeconomic factors.

To address these limitations, we plan to improve future research projects as follows. High-resolution remote-sensing data can be used to improve data accuracy. For ESV evaluation, multi-source data can be integrated to reflect local characteristics, such as ecosystem modeling based on local environmental data, visitor surveys, and social media review data. Owing to the limitations of the time scale, future research could extend this period to analyze long-term trends. Additionally, scenario simulations (e.g., InVEST models) can be used to predict the potential impacts of policies on future ESV, compensating for a short time span. To address the third point, future research should expand on these dimensions by incorporating social and economic indicators to establish a more comprehensive analytical framework. For example, the coupled coordination degree model can be used to comprehensively analyze the coordinated development of ecology, socioeconomics, and tourism within national parks.

5. Conclusion

This study analyzed the LULC changes in the Akan-Mashu National Park over the past decade and found that the changes were relatively stable, with the most notable changes observed in built-up areas, with a single dynamic index of 2.89%. Similar to the LULC changes, the ESV in the Akan-Mashu National Park also showed steady growth during this period, with an overall increase of 13.85 million USD. These results reveal that tourism development has not substantially harmed the ESV of Akan-Mashu National Park, highlighting the success of the park’s conservation efforts over the last ten years. Although water bodies account for only approximately 12% of the park’s total area, they contribute more than 70% of the ESV, highlighting the crucial role of water bodies in sustaining the park’s ecosystem services. Our analysis of the contributions of different ecosystem service types revealed that regulating services accounted for the highest proportion at approximately 52%, followed by cultural, habitat, and provisioning services. Additionally, we summarize the tourism development policies implemented in Akan-Mashu National Park up to 2020, and based on the analysis of LULC and ESV, we propose four management recommendations to promote sustainable tourism. These recommendations aim to better balance ecological conservation and tourism development, ensuring the long-term sustainability of Akan-Mashu National Park. The management recommendations we propose are not only targeted at the study area but are also intended to be applicable to other similar national parks or protected areas worldwide, providing a reference for sustainable tourism and land use management on a global scale.