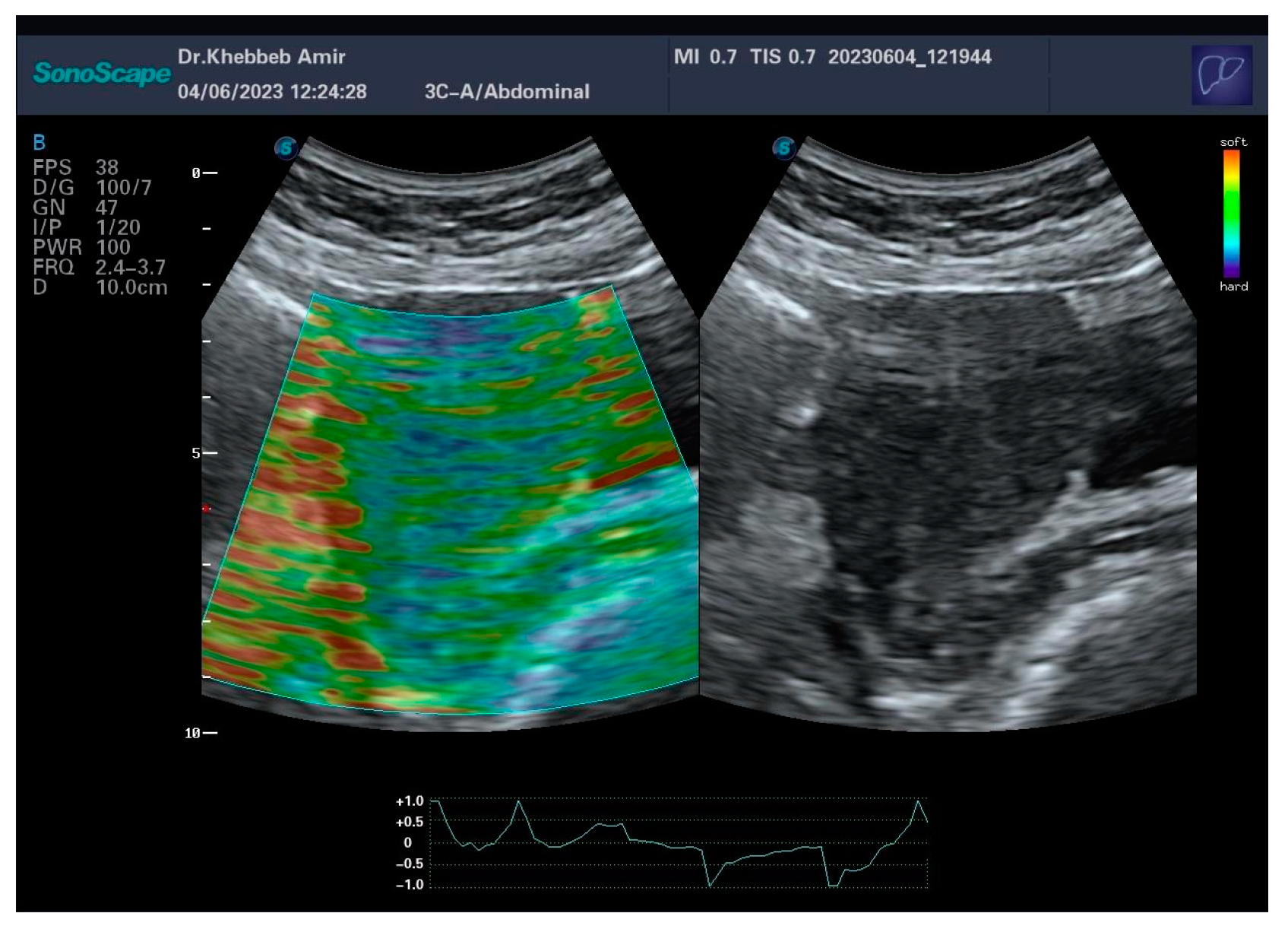

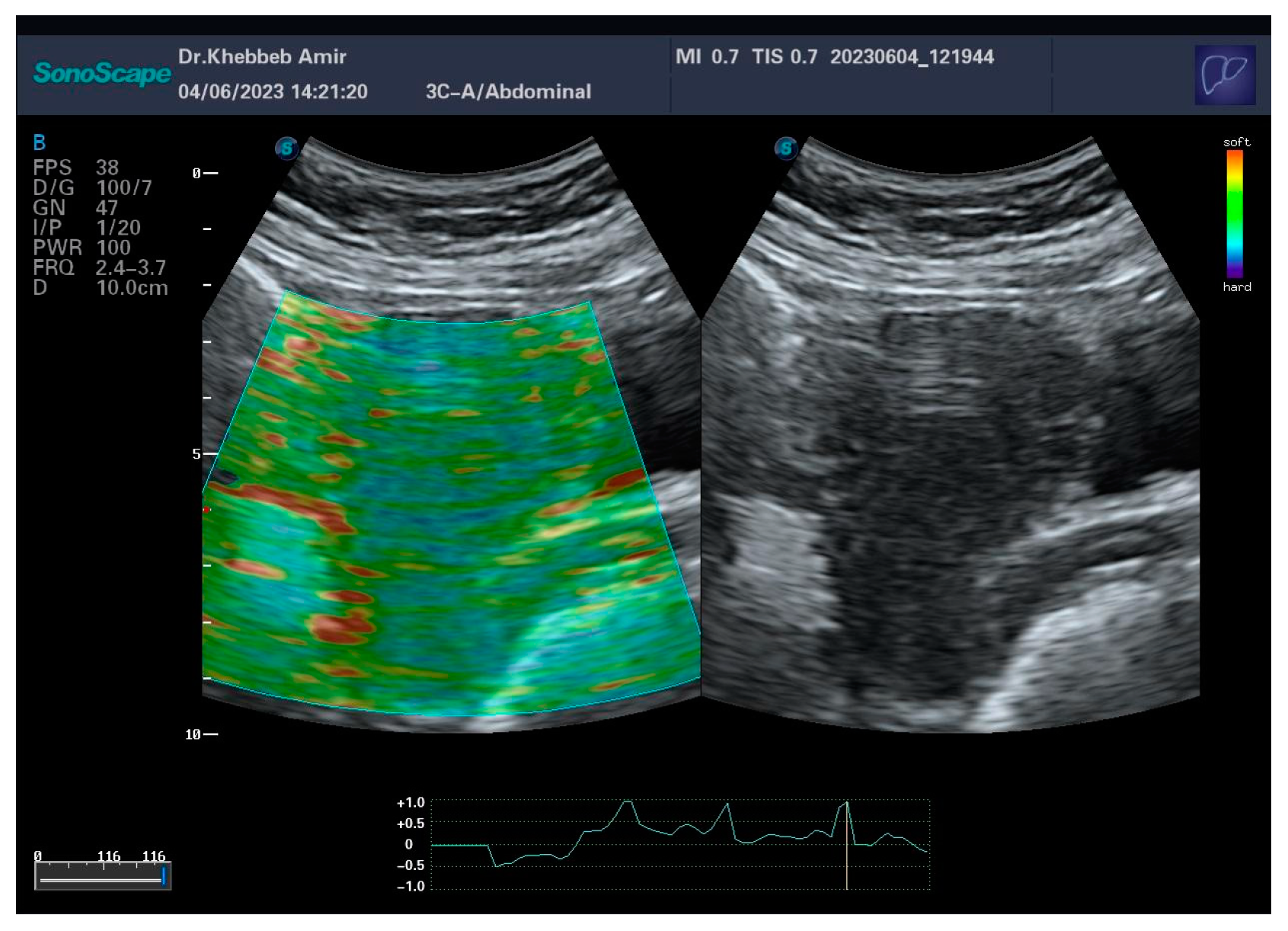

The pain relief, increased blood and mucus flow, and shortened menstruation observed in Group 01 can be explained by the fact that HH caused a global uterine relaxation. The myometrial softening at the cervical stage shall not only dilate the cervical os, but also restore the blood flow for the mucus secretory epithelium.

These two events combined shall facilitate the elimination of the menstrual content without the need of uterine contractions, responsible for dysmenorrhea.

The reduction of the vaginal infectious symptoms in the group 02 may be connected to the same effect: the facilitation of the menstrual content elimination will remove a crucial culture medium for various kinds of pathogens.

As for the patient of group 03, we can explain the responsiveness to the treatment by the fact that the myorelaxation by HH removed a significant downstream obstacle for the ovary, which is the retracted myometrium. The restored blood flow will bring the necessary material for a convenient follicular growth.

Laplace Law

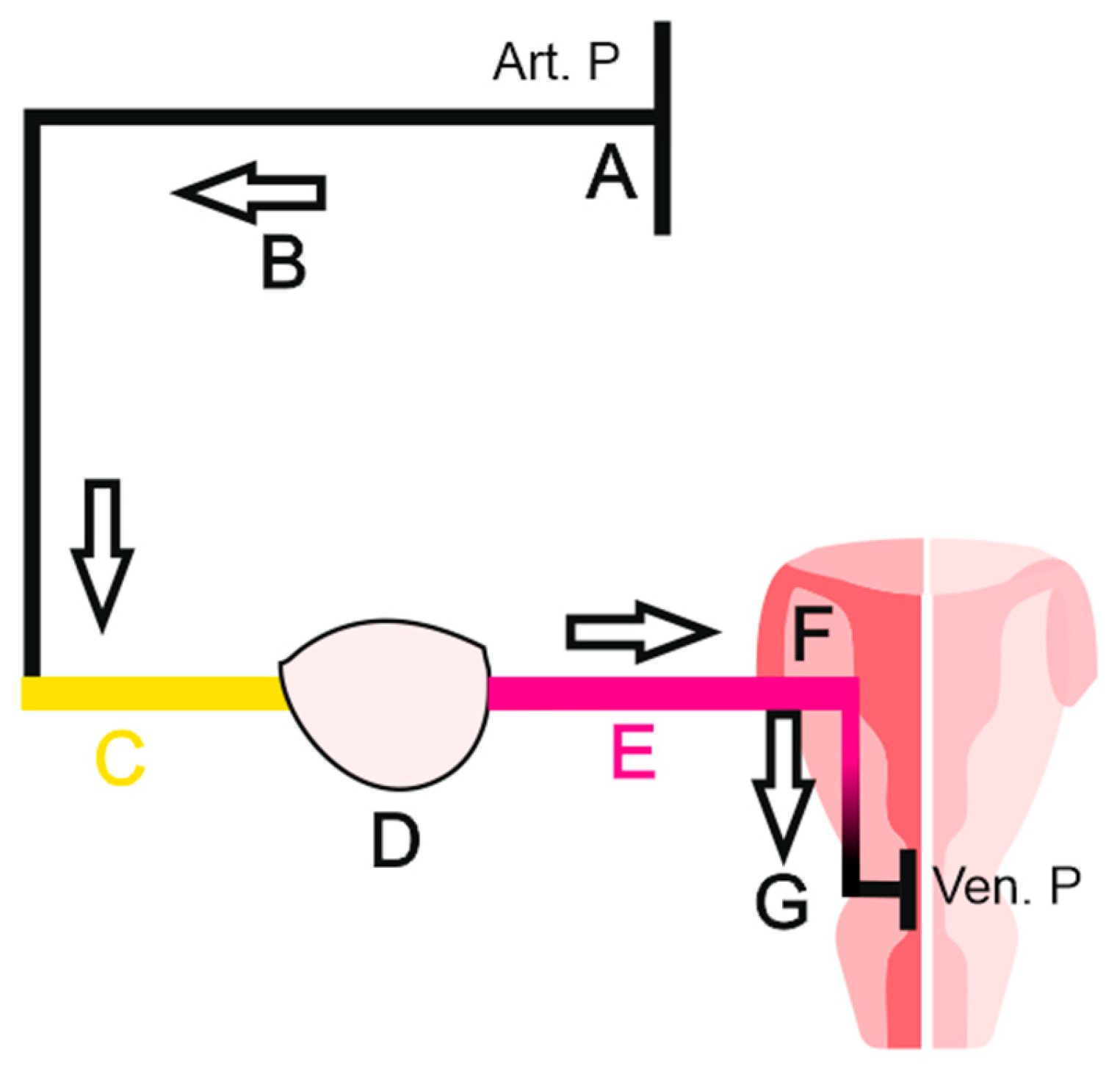

Laplace law is a fundamental principle that explains how fluid moves inside confined environments. It is widely applied in pulmonary physiology, and can by itself explain ventilation mechanics.

Indeed, any fluid tends to move from the higher to the lower pressure area, in a goal to achieve the equilibrium of the entropy described earlier.

To better understand this, we shall see how it works in pulmonary physiology.

During inspiration, the diaphragm muscle shall expand the thoracic cage. This will lower the pressure inside the body, making the external air “leak” into the body.

However, once inside, air circulation shall face a major problem, that may in some cases, lead to death.

Indeed, taking in consideration that internal alveolar pressure is inversely related to its radius and the fact that all alveoli are in direct communication together, this will make small and weak alveoli to literally spill their modest air countenance in the larger ones, causing them to collapse and drastically reducing gas exchange surface[

7].

To prevent this, physiology has equipped small alveoli with a special component that can maintain them open: the surfactant.

If this “unfair” law can be problematic in pulmonary physiology, it can be very useful in gynecology. Since there is no direct communication between follicles, no one shall collapse.

However the blood flow generated earlier by myometrial relaxation favors larger follicles, bypassing small follicles due to their higher internal pressure.

Surface tension is the force that rises at the top of a surface (interface) when two different phases of the matter encounter.

The different three phases we are facing in gynecology are the gas phase (peritoneal pressure), the liquid phase (follicular fluid) and the solid phase (the ovarian medulla). There is a positive correlation between surface tension and pressure gradient. Pressure gradient across a sphere is maximal when the state of the phase is different: a gas/liquid confrontation will generate more pressure gradient (tension) than a liquid/liquid encounter.

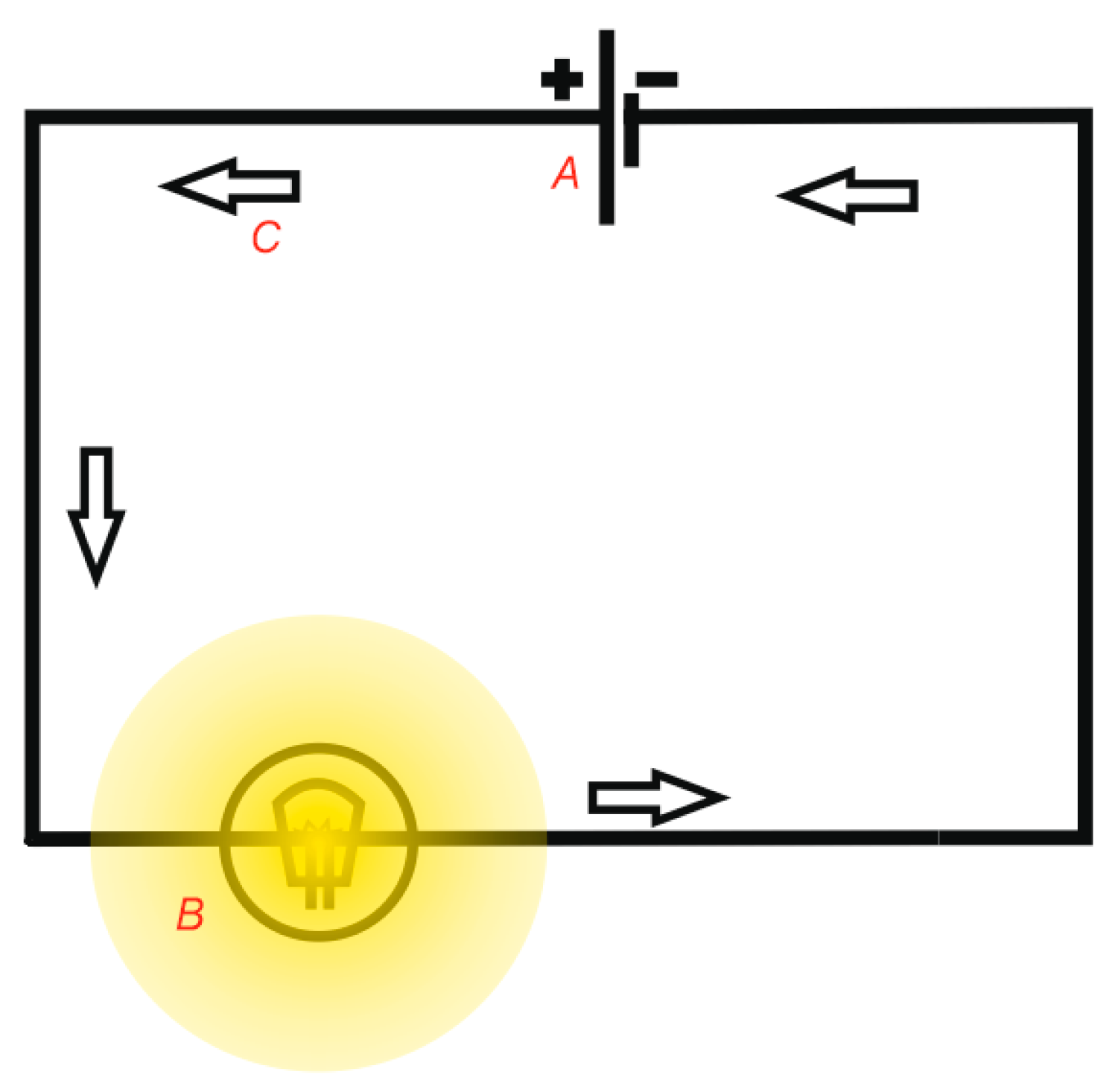

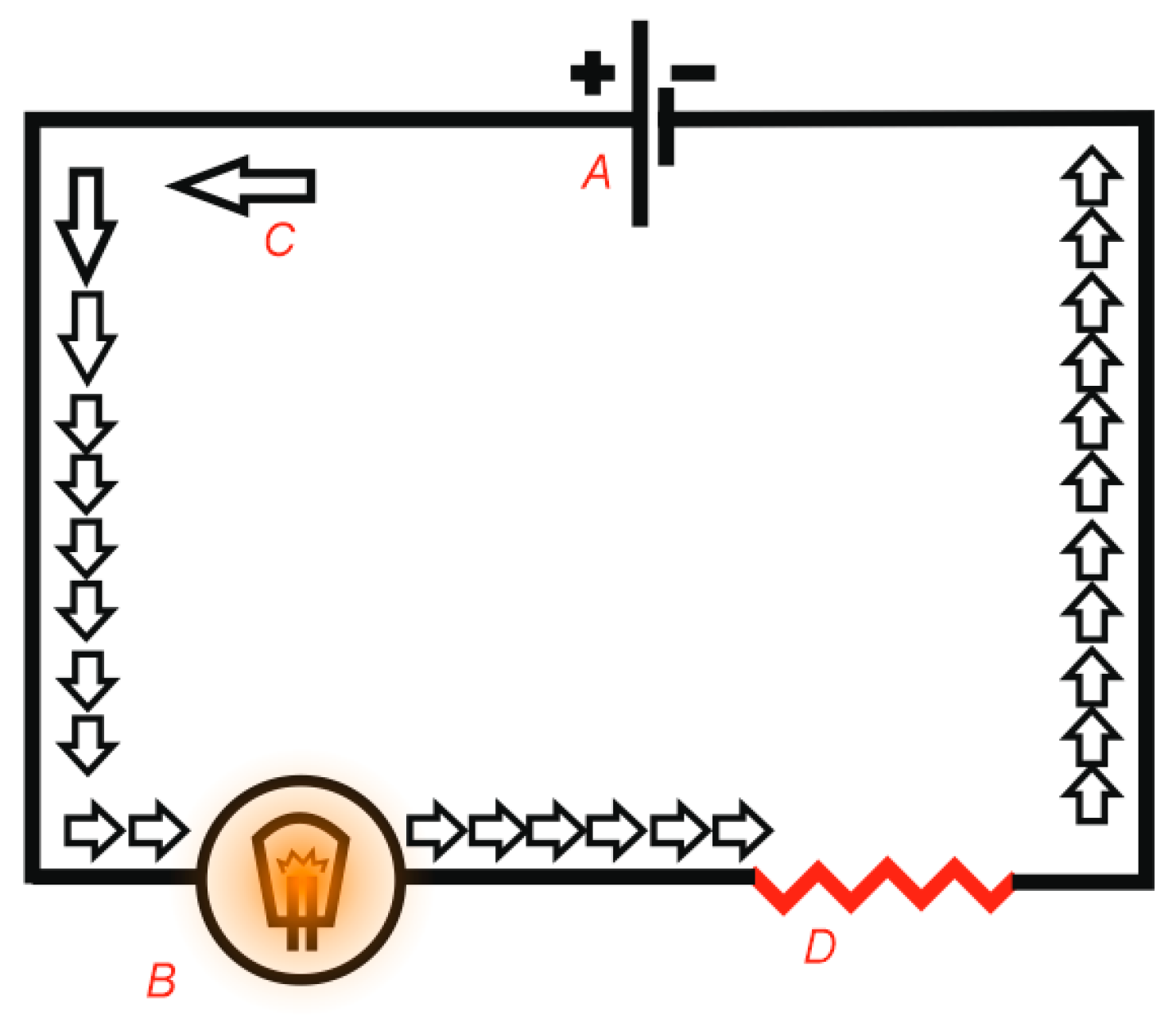

Pascal Law

According to Pascal law, the force applied to an incompressible liquid will be transmitted instantly and evenly to all the walls of a confined space, as the following:

When we combine both of Pascal and Laplace laws, wall thickness, surface tension, we can understand that a small follicle tends to generate a higher internal pressure, similarly to a small alveoli[

8], making it unwelcoming for the blood stream supposed to make it grow, the latter will then favor larger follicles with lesser internal pressure.

When the blood flow enters the follicle in the form of plasma (follicular fluid), the rise of follicular pressure will be counterbalanced by an elevation of follicular radius seeking the equilibrium state (entropy). However, the follicular wall thickness is a limited physical property: the radius growth is in fact a stretching made at the cost of the wall being thinner. Furthermore, The incompressibility of the fluid will this time act on the wall making it thinner too. When the elasticity of the thin wall cannot handle the radius growth anymore for sake of the equilibrium described earlier, the follicular shell (albuginea) will break leading to ovulation.

In summary, when the blood flow is moderate, follicular growth, dominance and ovulation are three phenomena that may be controlled by the laws of Laplace and Pascal.

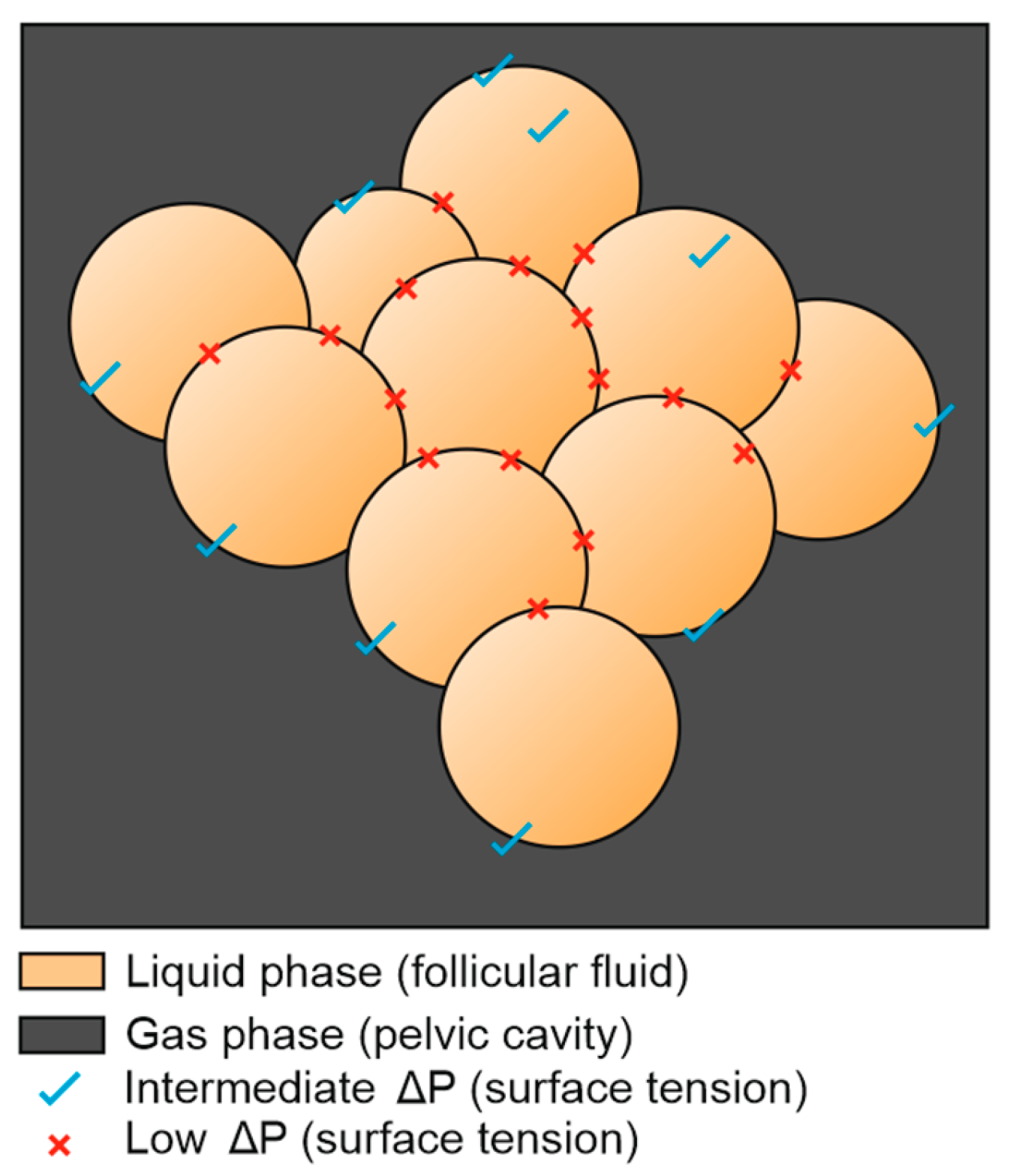

However, when the blood flow gets stronger, such as in the case of hyperstimulation, something else happens. The predominant follicle will grow, but its rapid saturation will make other follicles grow too (

Figure 7).

If a “challenging” follicle reaches the predominant one, this can be very counterproductive for ovulation. Indeed, we have seen that the surface tension rise is crucial for ovulation, and it is closely correlated to the nature of the surrounding phase. When a challenging follicle touches the predominant one, it will swap its surrounding solid medulla by a similar follicular fluid. The contact of two same phases (liquid/liquid in this case) will drop the surface tension of the dominant follicle which will seriously compromise its ovulation potential.

In this case, the predominant follicle, which was promised a bright destiny, finds itself brought to the “past” once touched by the growth of other challenging follicles. From these findings, we can presume that a lonely, offcentered follicle with a diameter of 15mm, facing several phases of the matter, especially the gas phase, has a better chance to ovulate than a 21mm follicle surrounded by lesser peers (

Figure 7).

This leads us to the conclusion that the current follicular monitoring technique may be incomplete, since it takes in account the diameter only, excluding the other key parameter represented by the pressure gradient generated by the follicular environment.

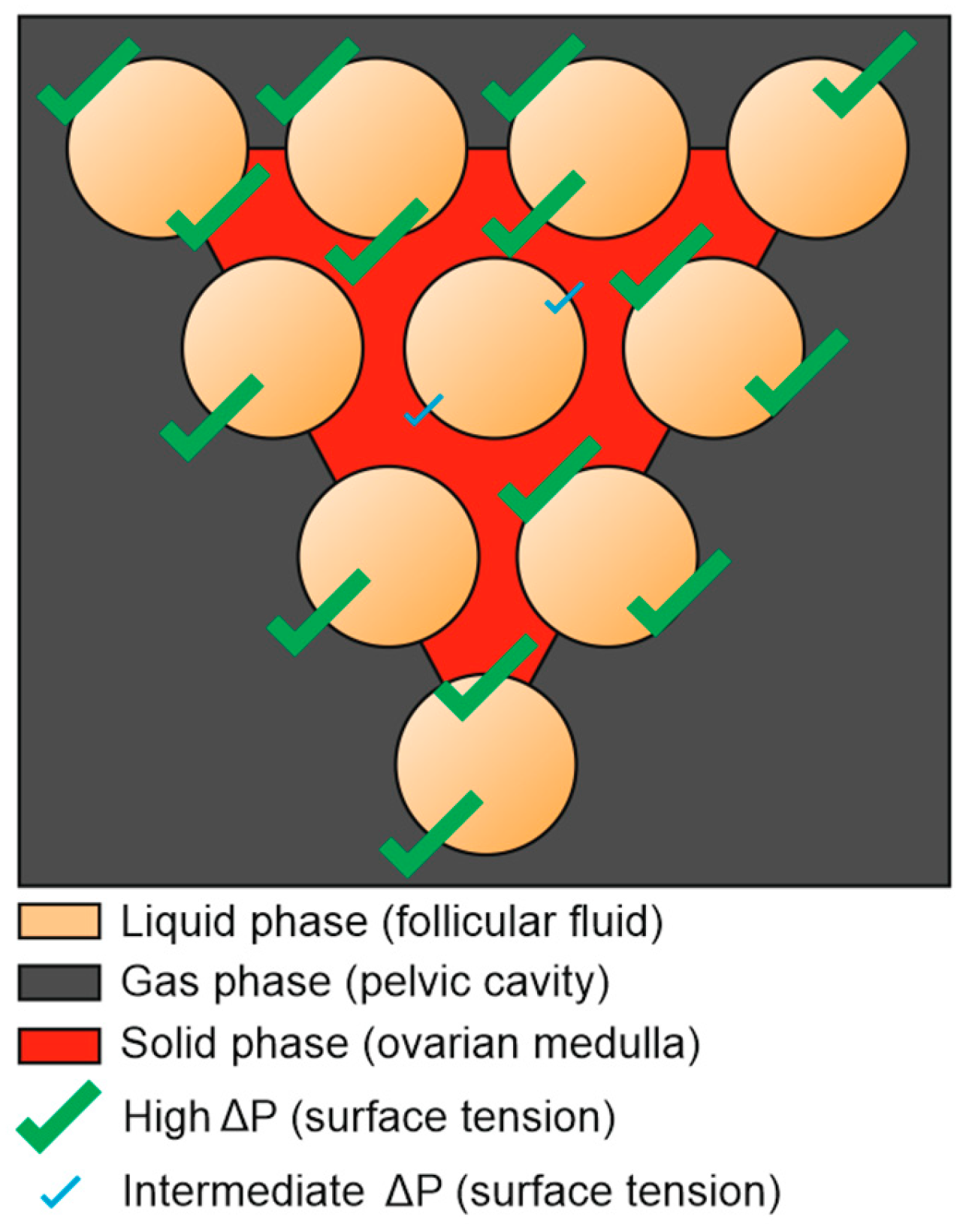

The current monitoring technique which takes in account follicular diameter only, could have been sufficient in the case the follicles were totally independent from each other (

Figure 6), in a manner of a grapefruit: each unit of the fruit would be completely surrounded by different states of the matter, which will grant a sufficient pressure gradient. in this case, the pressure would be constant and the surface tension would be factorial to diameter only.

Figure 6.

The confrontation of the 3 different states of the matter by its own (fluid-gas-solid) tends to generate a higher surface tension, whatever the follicular diameter.

Figure 6.

The confrontation of the 3 different states of the matter by its own (fluid-gas-solid) tends to generate a higher surface tension, whatever the follicular diameter.

Figure 7.

The growth of multiple follicles (hyperstimulation) at the expense of the ovarian medulla replaces a solid phase by a liquid one, causing a general drop of surface tension.

Figure 7.

The growth of multiple follicles (hyperstimulation) at the expense of the ovarian medulla replaces a solid phase by a liquid one, causing a general drop of surface tension.

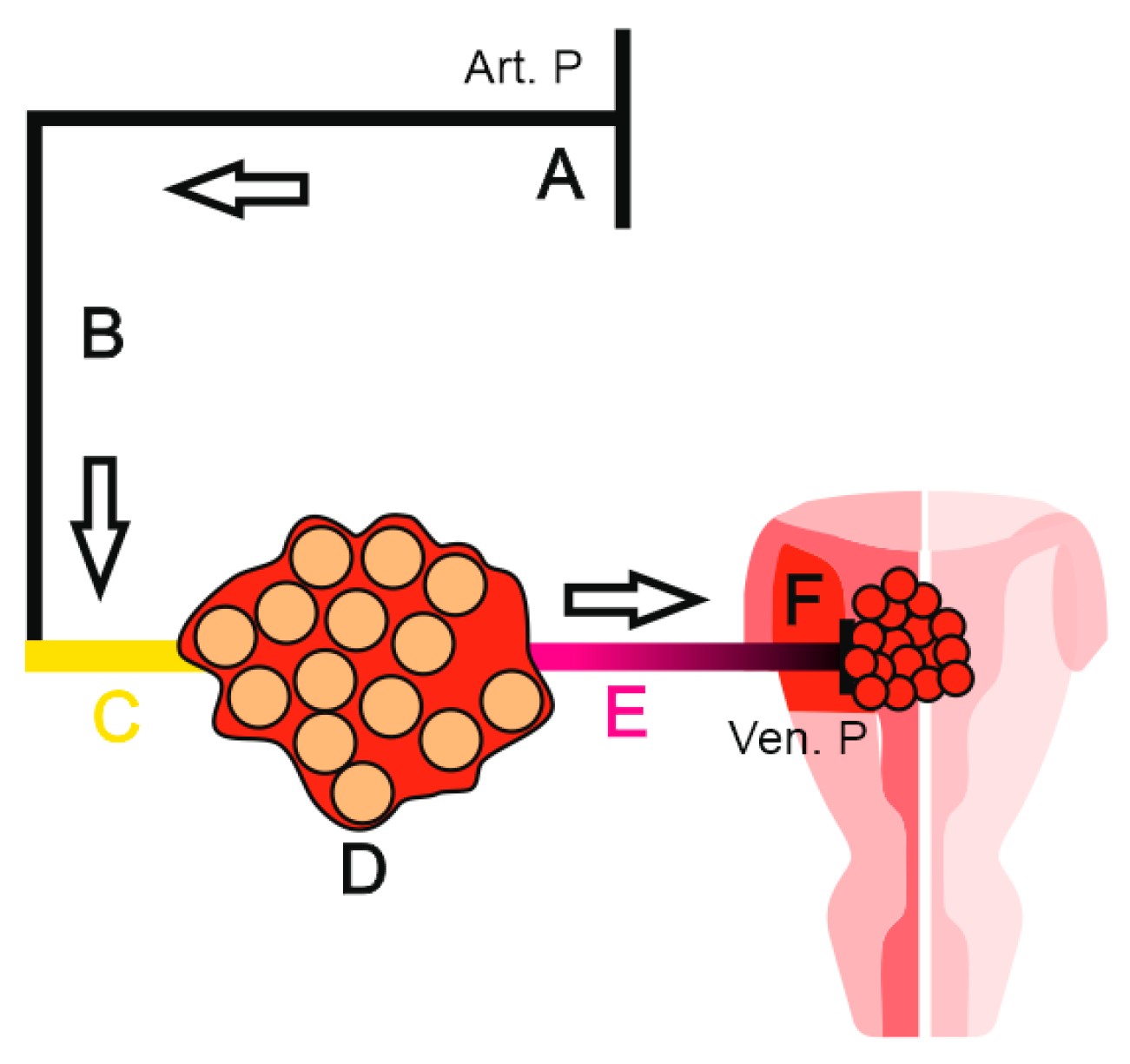

This follicular reckless “race to ovulation” may have very useful roles in physiology: The first one is to prevent multiple pregnancies by favoring only one ovulation. The second one, by the way, is the key evidence of this manuscript: preventing ovarian depletion in the molar pregnancy.

The molar pregnancy is a medical condition where the trophoblast undergoes pathological cystic transformation, leading ultimately to an abortion.

It is well established that in the molar pregnancy, the ovaries are often hyperstimulated, this condition being assigned to BHCG action[

9].

Based on the findings of this work and after reinterpretation of hormonal actions, we are not in agreement with this theory.

Indeed, the problem with the molar pregnancy is not the level of the BHCG itself, but its elevation compared to the term of the pregnancy. For instance, we may very well find a BHCG level of 300.000 IU/ml in an 8 weeks pregnancy and consider it molar, but the problem is that we shall find similar rates in a physiological pregnancy at 26 weeks as well. The question: Why do we never find hyperstimulated ovaries in a physiological pregnancy of 26 weeks? Answer: Because BHCG may be not responsible for hyperstimulation. The actual answer resides in the physical exam which is often neglected: a soft uterus fundus. For some reason, practitioners think they are sensing the vesicles themselves during palpation, this may in fact be a common misconception since regular trophoblast and amniotic fluid of a physiological pregnancy have similar, even softer consistency than the molar vesicles. In fact, they are dealing with a surrendered soft myometrium.

There is no need to practice an elastography here since the elevated fundal height made it clinically obvious. This aligns with our first theory of the relationship between a soft myometrium and ovarian stimulation. In this case, the FSH is not the responsible of the inertia, but the uncontrolled mitosis of the vesicular trophoblast caused myometrial neovascularization that gained backward access to the ovary through the utero ovarian artery. Despite myometrial efforts to retract, the aggressive trophoblastic activity “won” the duel and relaxed the uterine fundus, literally opening the “gates of hell” for the ovary(

Figure 8).

The ovary in this case has little margin of maneuvers and can only activate a final defensive mode: the growth of multiple follicles will cause a general drop of surface tension and prevent follicular depletion (

Figure 7).

This “airbag” (or water bag) mode will be the last resort of the ovary: if the molar pregnancy continues, the flow will remove all the medulla, as there will be no internal surface tension, the ovary will behave as a giant single cyst leading to an ovarian rupture and potentially the death of the patient. If the current technique of follicular monitoring, which relies exclusively on follicular diameter was correct, many hyperstimulation cases would result in an ovarian menopause.

We decided to make further investigations and revisit the iatrogenic ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome of in vitro fertilization (OHSS). When we compare these two hyperstimulations (molar and IVF) we find a key difference in the symptomatology.

Indeed, in the OHSS of the IVF, we encounter an ascites[

10], which sometimes needs to be aspirated and can lead to an elevation of the thromboembolic risk, requiring preventive anticoagulant medication. Question: Why don’t we find ascites in molar pregnancy, despite the similarity of the background ? Answer: It is due to the “negative terminal” of the Ohm’s law described earlier.

In the molar pregnancy, the final generator of the blood flow (negative terminal) that assures the drop of the venous pressure is the pregnancy itself, where there is only a partial sequestration of the blood by the trophoblast. Whereas in the IVF OHSS, the drop of venous pressure is probably caused by the production of the cervical mucus, but rather than a partial blood sequestration, there may be a major leak of proteins for the production of the mucus, which leads to a drop of the oncotic pressure, leading to this ascites.

As a final analogy, we can take an example of water circulation inside a pipe: How do water companies bill water consumption? There are two options: 1- There is a person in each household that collects all the used water in a big container and then takes it to the water company for billing. 2- There is a water meter that measures the consumption (pretty reliable option).

How does the water meter measure the consumption ? Actually, it doest it, not by measuring the final water output, but using the flow of the circulating water. When the tap is open, the water going outside generates a flow in the water meter despite its upstream location. The tap here would be the myometrium, the water meter being the ovary.

FSH would manually open the tap, while molar pregnancy shall force it in a manner of introducing a metallic rod backwards into the nozzle, reaching the mechanism and breaking it. In both cases, a flow will be generated for the water meter (ovary). We can go further in our interpretation and consider that even a small cervical polyp, or a cervical narrowing can be sufficient to stop follicular growth by blocking mucus production, which may be a key condition for maintaining a correct blood flow for the ovary.