Submitted:

03 December 2025

Posted:

03 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

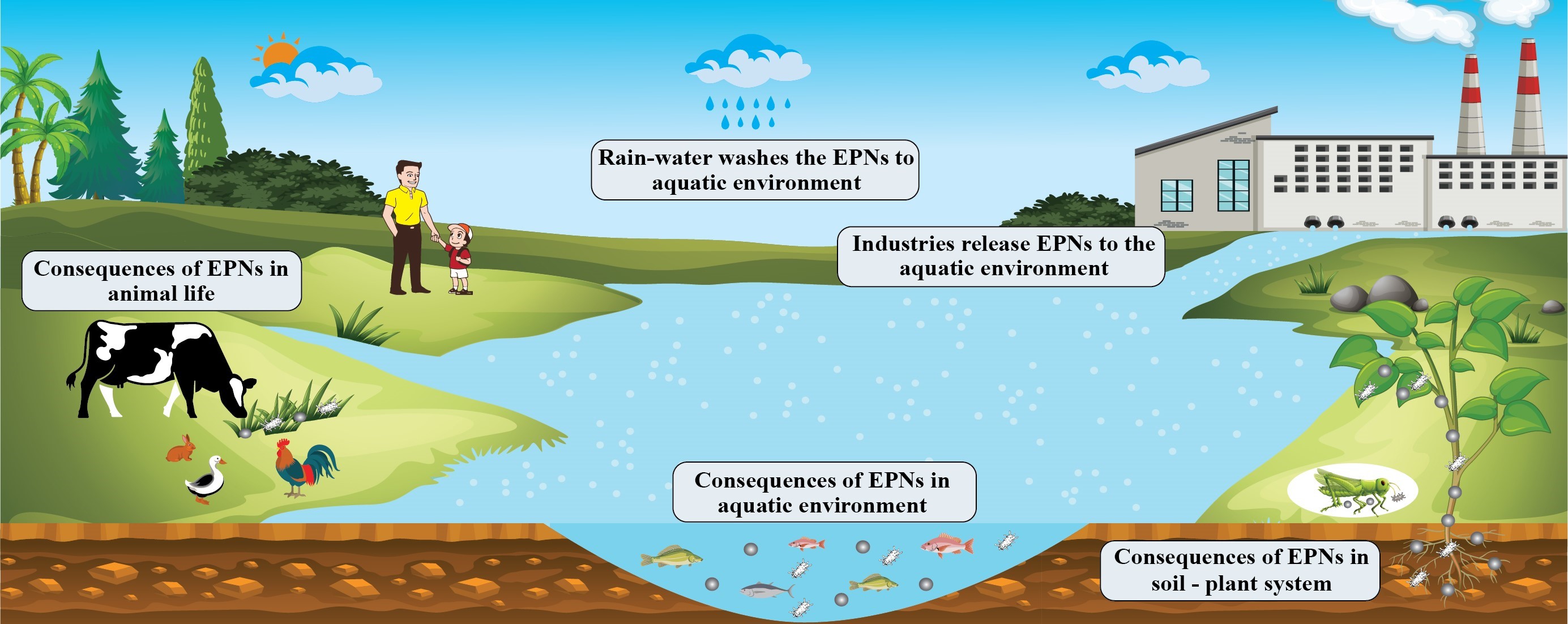

1. Introduction

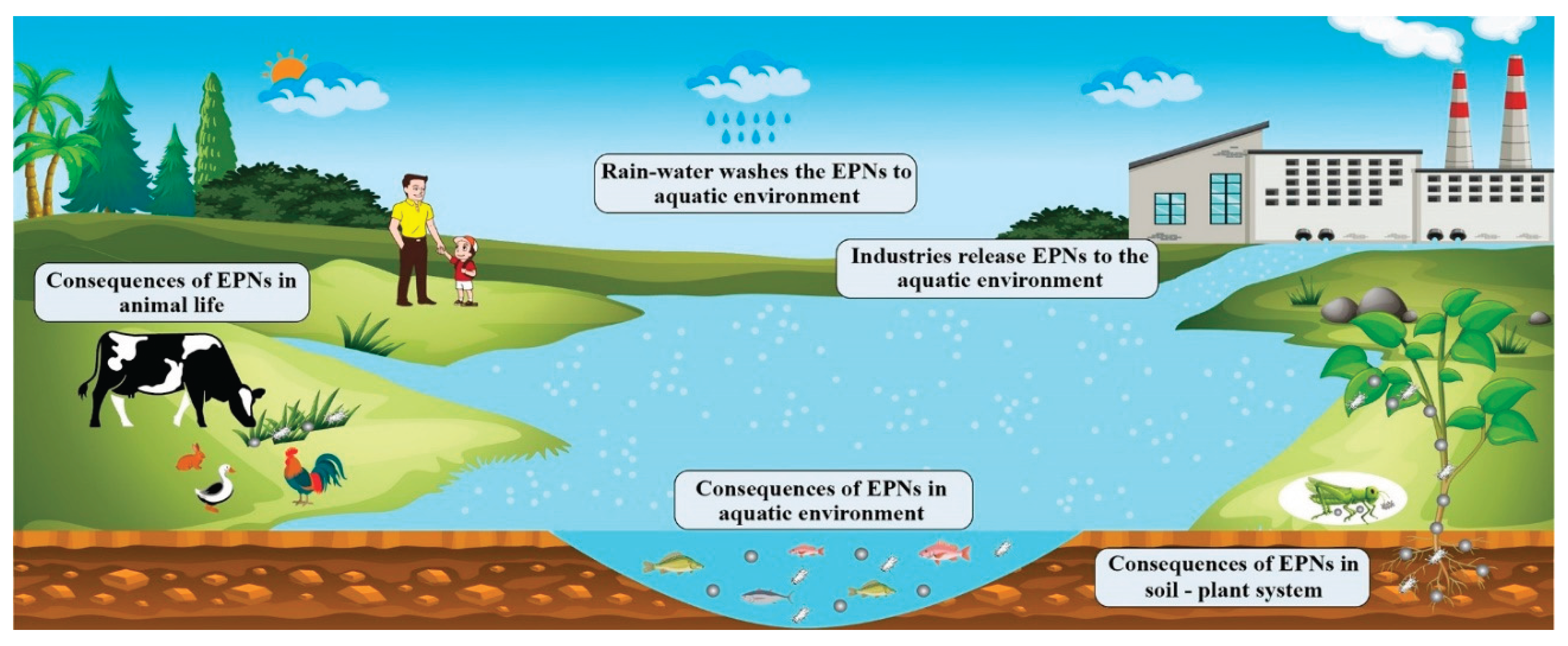

2. ENPs in the Aquatic Environment

2.1. ENP Interactions with Aquatic Organisms

2.2. Behavior and Fate of ENPs in the Aquatic Environment

2.3. Toxicological Effects of ENPs in the Aquatic Environment

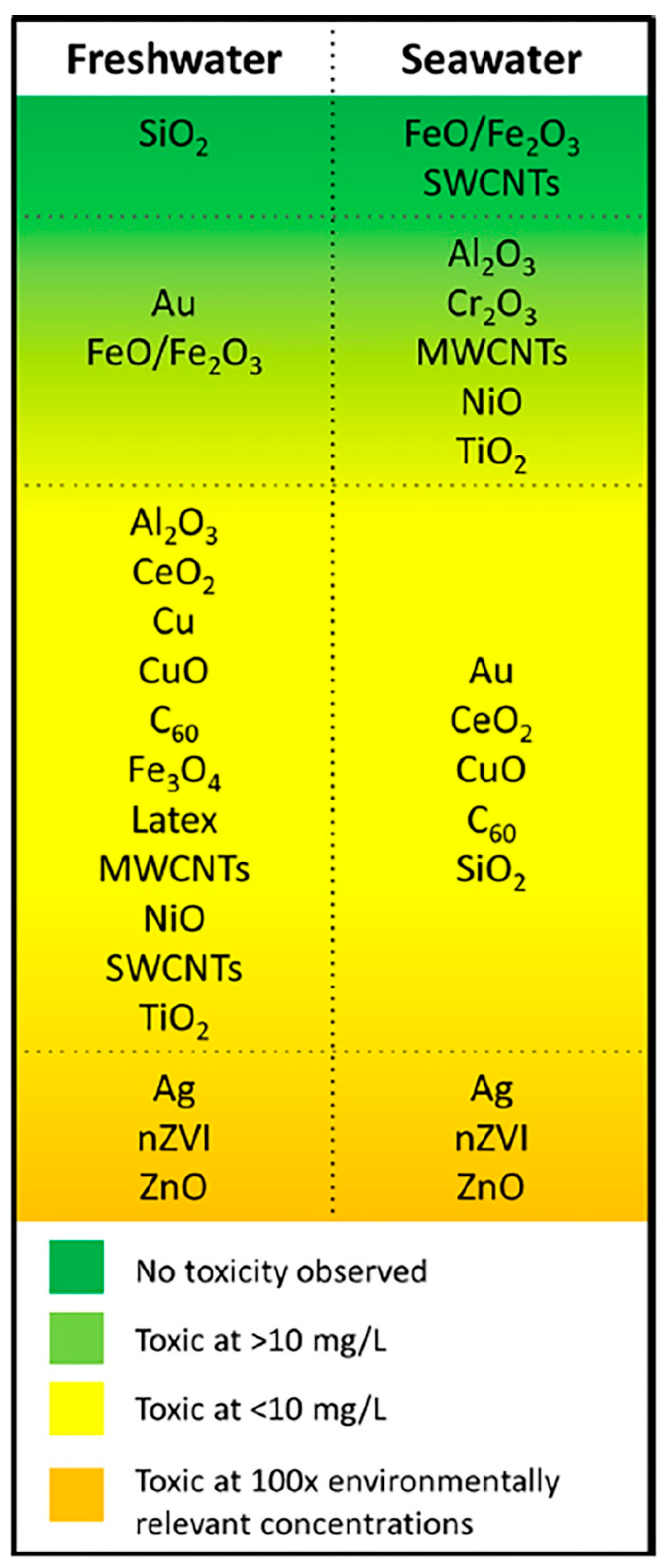

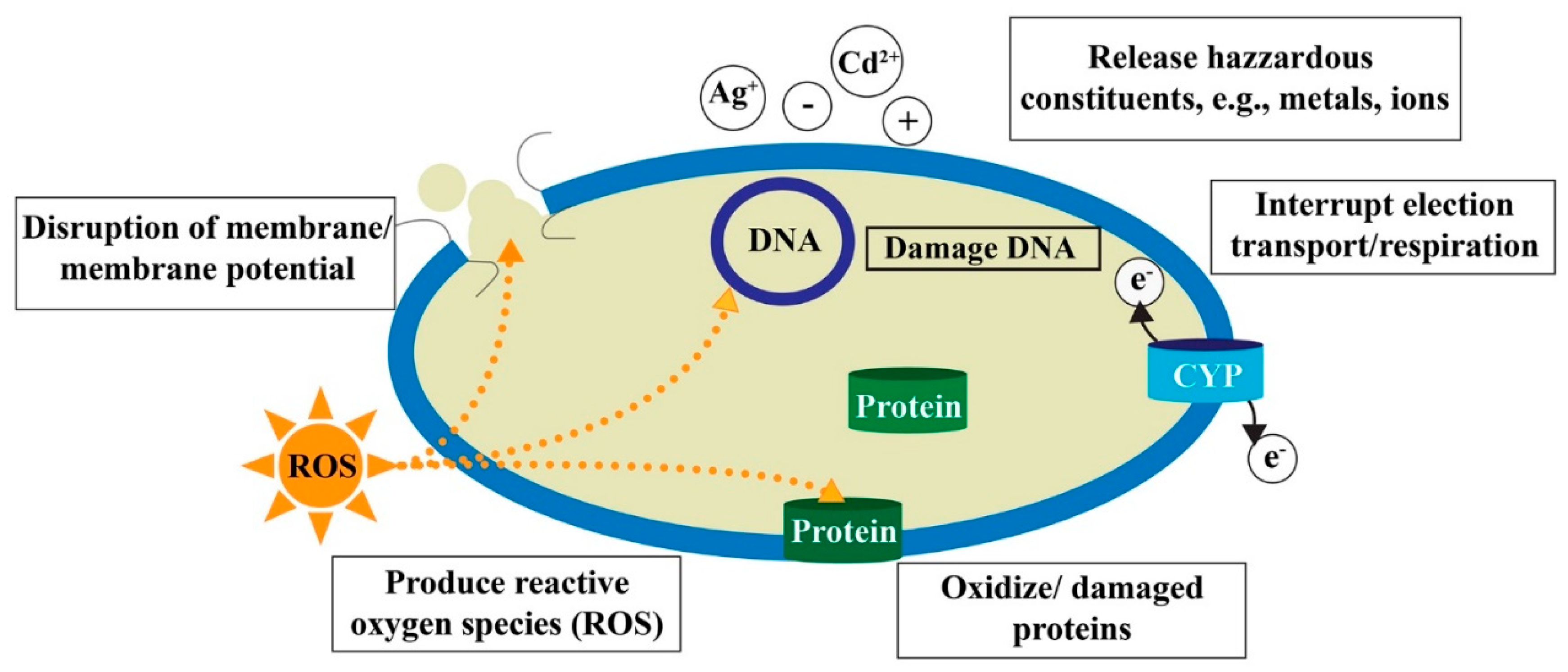

2.3.1. Toxic Effects of ENPs on Microbes and Algae

2.3.2. Toxic Effects of ENPs on Aquatic Vertebrates

2.3.3. Toxic Effects of ENPs on Aquatic Invertebrates

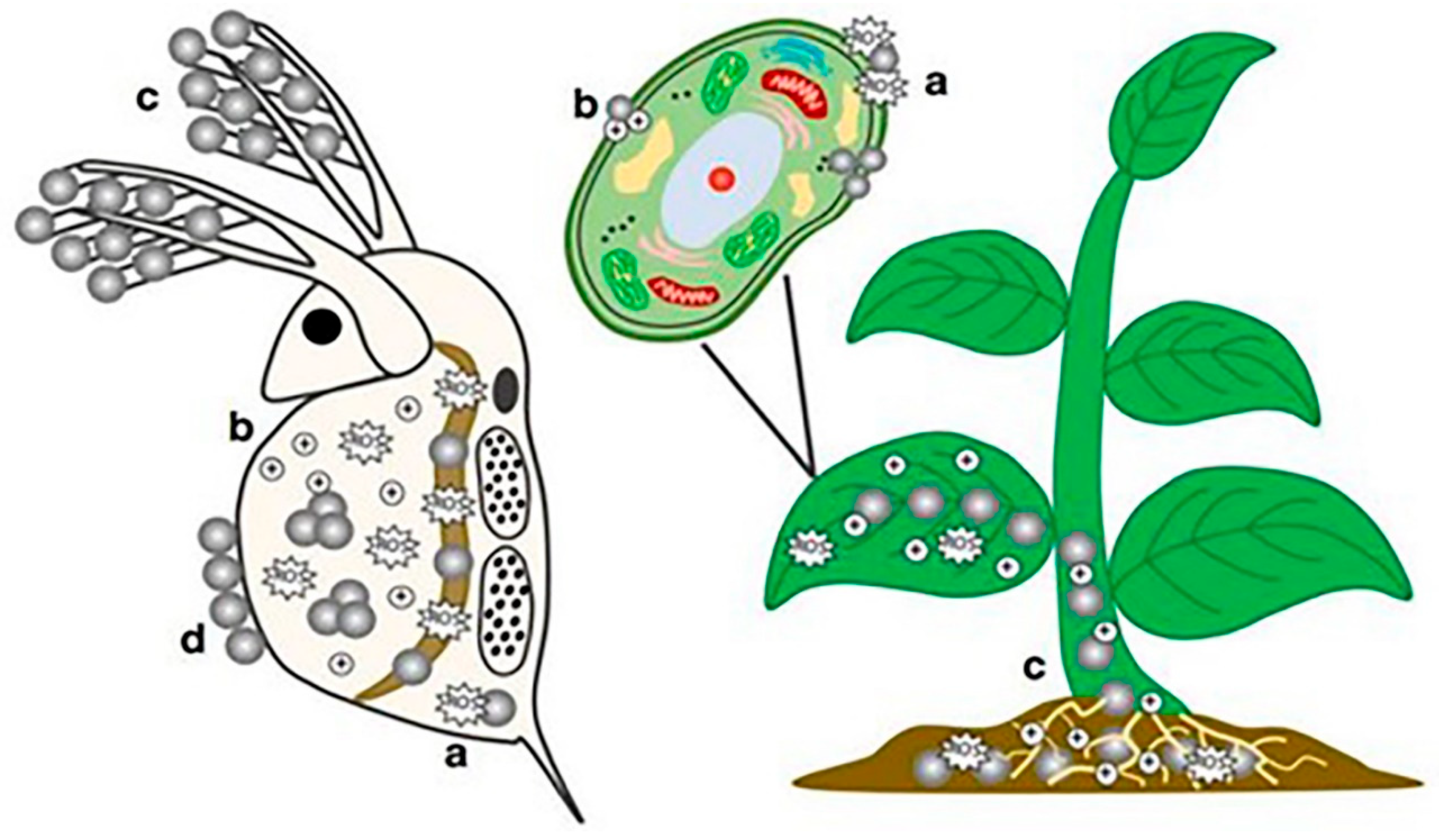

3. ENPs in the Soil-Plant System

3.1. Interactions of ENPs with Soil-Plant Systems

3.2. Toxicological Effects of ENPs in Soil-Plant

3.3. Toxic Effects of ENPs on Plant Growth

3.4. Linkages of ENP Transformation with Bioavailability and Toxicity

3.5. Risk Assessment Models for ENPs

3.6. Implications for Stakeholder Engagement in the Regulatory Policy of ENPs

4. Outlook to Address the Impacts of ENPs

4.1. Reuse and Recycle

4.2. Development of Disposal Management Strategies

4.3. Need for Standardization: Comparing Exposure Protocols

4.4. Implementation of Regulatory Policy

4.5. Challenges In Situ Characterization and Data Reliability

4.6. Understanding Toxicity and Transmission by Further Research

4.7. Risk Assessment for ENP Life Cycle

4.8. Risk Assessment for ENP Life Cycle

4.8.1. Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA) of Applications vs. Risks

4.8.2. Regulatory and Compliance Costs

4.8.3. Cleanup and Environmental Remediation Costs

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Al2O3 | Aluminum oxide |

| AgNPs | Silver nanoparticles |

| CuO | Copper oxide |

| CuNPs | Copper nanoparticles |

| QDs | Quantum dots |

| ENP | Engineered nanoparticle |

| FA | Fulvic acid |

| HA | Humic acid |

| NPs | Nanoparticles |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| THF | Tetrahydrofuran |

| TiO2 | Titanium oxide |

| ZnO | Zinc oxide |

References

- Suazo-Hernández, J.; Arancibia-Miranda, N.; Mlih, R.; Cáceres-Jensen, L.; et al. Impact on some soil physical and chemical properties caused by metal and metallic oxide engineered nanoparticles: A review. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, C.; Zhang, W.; Gao, H.; Li, Y.; et al. Behavior and potential impacts of metal-based engineered nanoparticles in aquatic environments. Nanomaterials 2017, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, I.; Saeed, K.; Khan, I. Nanoparticles: Properties, applications and toxicities. Arabian J. of Chem. 2019, 12, 908–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwakarma, V.; Ogunkunle, C.O.; Rufai, A.B.; Okunlola, G.O.; et al. Nanoengineered particles for sustainable crop production: potentials and challenges. 3 Biotech 2023, 13, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perea Velez, Y.S.; Carrillo-González, R.; Gonzalez-Chavez, M.D.C.A. Interaction of metal nanoparticles–plants–microorganisms in agriculture and soil remediation. J. of Nanopar. Res. 2021, 23, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, Q.; Yousaf, B.; Ullah, H.; Ali, M.U.; Ok, Y.S.; Rinklebe, J. Environmental transformation and nano-toxicity of engineered nano-particles (ENPs) in aquatic and terrestrial organisms. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 3389, 2523–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, W.S.; Asmatulu, E.; Asmatulu, R. Nanotechnology emerging trends, markets and concerns. In Nanotechnology Safety, 2nd Ed.; Elsevier, 2025, 1-21.

- Pastrana-Pastrana, Á.J.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R.; Solanilla-Duque, J.F.; Flores-Gallegos, A.C. Plant proteins, insects, edible mushrooms and algae: more sustainable alternatives to conventional animal protein. J. of Future Foods 2025, 5, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomte, S.S.; Jadhav, P.V.; Prasath, V.R.N.J.; Agnihotri, T.G.; Jain, A. From lab to ecosystem: Understanding the ecological footprints of engineered nanoparticles. J. Environ Sci. Health Part C 2023, 42, 33–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagariya, M.; Ghosh, A.; Pratihar, S. Life Cycle Risk Assessment and Fate of the Nanomaterials: An environmental safety perspective. In Occurrence, Distribution and Toxic Effects of Emerging Contaminants, Shanker, U.; Rani, M. (eds), CRC Press, 2024, 201-226.

- Gajewicz, A.; Rasulev, B.; Dinadayalane, T.C.; Urbaszek, P.; et al. Advancing risk assessment of engineered nanomaterials: application of computational approaches. Advanced Drug Delivery Rev. 2012, 64, 1663–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayaram, S.; Razafindralambo, H.; Sun, YZ.; Vasantharaj, S.; et al. Applications of green synthesized metal nanoparticles — a review. Biol. Trace. Elem. Res. 2024, 202, 360–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Yang, J.; Kwon, S.G.; Hyeon, T. Nonclassical nucleation and growth of inorganic nanomaterials. Nat. Rev. Materials 2016, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gottschalk, F.; Lassen, C.; Kjoelholt, J.; Christensen, F.; Nowack, B. Modeling flows and concentrations of nine engineered nanomaterials in the Danish environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2015, 12, 5581–5602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uddin, M.N.; Desai, F.; Asmatulu, E. Engineered nanomaterials in the environment: bioaccumulation, biomagnification, and biotransformation. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 18, 1073–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amenta, V.; Aschberger, K.; Arena, M.; Bouwmeester, H.; et al. Regulatory aspects of nanotechnology in the agri/feed/food sector in EU and non-EU countries. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2015, 73, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, Q.; Liu, G.; Yousaf, B.; Ali, M.U.; Ullah, H.; Ahmed, R. Effects of biochar on uptake, acquisition and translocation of silver nanoparticles in rice (Oryza sativa L.) in relation to growth, photosynthetic traits and nutrients displacement. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 250, 728–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Kumar, D.; Aziz, A.; AbdelRahman, M.A.E.; et al. Nanoecology: Exploring engineered nanoparticles’ impact on soil ecosystem health and biodiversity. Egyptian J. of Soil Sci. 2024, 64, 1637–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolan, S.; Sharma, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Zhou, J.; et al. The distribution, fate, and environmental impacts of food additive nanomaterials in soil and aquatic ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 916, 170013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwirn, K.; Voelker, D.; Galert, W.; Quik, J.; Tietjen, L. Environmental risk assessment of nanomaterials in the light of new obligations under the REACH regulation: which challenges remain and how to approach them? Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2020, 16, 706–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cota-Ruiz, K.; Valdes, C.; Flores, K.; Yuqing, Y.; et al. Physiological and molecular responses of plants exposed to engineered nanomaterials. In Plant Exposure to Engineered Nanoparticles, Academic Press, 2022, 171-194.

- Dwivedi, A.D.; Dubey, S.P.; Sillanpää, M.; Kwon, Y.N.; Lee, C.; Varma, R.S. Fate of engineered nanoparticles: Implications in the environment. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015, 287, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council, Report of the Committee on Proposal Evaluation for Allocation of Supercomputing Time for the Study of Molecular Dynamics: Third Round, The National Academies Press, Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- Akter, M.; Sikder, M.T.; Rahman, M.M.; Ullah, A.; et al. A systematic review on silver nanoparticles-induced cytotoxicity: Physicochemical properties and perspectives. J. Adv. Res. 2018, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xiao, B.; Fang, T. Chemical transformation of silver nanoparticles in aquatic environments: Mechanism, morphology, and toxicity. Chemosphere 2018, 191, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joonas, E.; Aruoja, V.; Olli, K.; Kahru, A. Environmental safety data on CuO and TiO2 nanoparticles for multiple algal species in natural water: Filling the data gaps for risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 647, 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lead, J.R.; Batley, G.E.; Alvarez, P.J.J.; Croteau, M.N.; Handy, R.D.; McLaughlin, M.J.; Judy, J.D.; Schirmer, K. Nanomaterials in the environment: Behavior, fate, bioavailability, and effects – An updated review. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2018, 37, 2029–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slaveykova, V.I.; Li, M.; Worms, I.A.; Liu, W. When environmental chemistry meets ecotoxicology: Bioavailability of inorganic nanoparticles to phytoplankton. Chimia 2020, 74, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garner, K.L.; Keller, A.A. Emerging patterns for engineered nanomaterials in the environment: a review of fate and toxicity studies. J. of Nanopart. Res. 2014, 16, 2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Liang, S.; et al. Detection, distribution and environmental risk of metal-based nanoparticles in a coastal bay. Water Res. 2023, 242, 120242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, A.A.; Lazareva, A. ; Predicted releases of engineered nanomaterials: from global to regional to local. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2013, 1, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuverza-Mena, N.; Martínez-Fernandez, D.; Du, W.; Hernandez-Viezcas, J.A.; et al. Exposure of engineered nanomaterials to plants: Insights into the physiological and biochemical responses: A review. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 110, 236–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, G.V.; Gregory, K.B.; Apte, S.C.; Lead, J.R. Transformations of nanomaterials in the environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 6893–6899. [Google Scholar]

- Sohlot, M.; Khurana, S.M.P.; Das, S.; Debnath, N. Fate of engineered nanomaterials in soil and aquatic systems. In Green Nanobiotechnology, Thakur, A.; Thakur, P.; Suhag, D.; Khurana, S.M.P. (eds), CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL 33431, USA, 2025, 265-290.

- Mittal, D.; Kaur, G.; Singh, P.; Yadav, K.; Ali, S.A. Nanoparticle-based sustainable agriculture and food science: Recent advances and future outlook. Frontiers in Nanotechnol. 2020, 2, 579954. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Ao, C.; Wu, M.; Zhang, P.; Pan, B.; Xing, B. Geochemical behavior of nanoparticles as affected by biotic and abiotic processes. Soil & Environ. Health 2025, 3, 100145. [Google Scholar]

- Suji, S.; Harikrishnan, M.; Vickram, A.; et al. Ecotoxicological evaluation of nanosized particles with emerging contaminants and their impact assessment in the aquatic environment: A review. J. Nanopart. Res. 2025, 27, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hund-Rinke, K.; Simon, M. Ecotoxic effect of photocatalytic active nanoparticles (TiO2) on algae and daphnids. Env. Sci. Poll. Res. Int. 2006, 13, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, M.N. Do nanoparticles present ecotoxicological risks for the health of the aquatic environment? Environ. Int. 2006, 32, 967–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kicheeva, A.G.; Sushko, E.S.; Bondarenko, L.S.; Kydralieva, K.A.; et al. Functionalized magnetite nanoparticles: characterization, bioeffects, and role of reactive oxygen species in unicellular and enzymatic systems. Int. J. of Molecular Sci. 2023, 24, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delay, M.; Frimmel, F.H. Nanoparticles in aquatic systems. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2012, 402, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowack, B.; Ranville, J.F.; Diamond, S.; Gallego-Urrea, J.A.; et al. Potential scenarios for nanomaterials release and subsequent alteration in the environment. Environ. Toxicol Chem. 2012, 31, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thwala, M.; Klaine, S.J.; Musee, N. Interactions of metal-based engineered nanoparticles with aquatic higher plants: A review of the state of current knowledge. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2016, 35, 1677–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stebounova, L.V.; Guio, E.; Grassian, V.H. Silver nanoparticles in simulated biological media: a study of aggregation, sedimentation, and dissolution. J. Nanopart Res. 2011, 13, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatehah, M.O.; Aziz, H.A.; Stoll, S. Nanoparticle properties, behaviour, fate in aquatic systems and characterization methods. J. Coll. Sci. Biotechnol. 2014, 3, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, S.; Mudumkotuwa, I.A.; Rupasinghe, T.; Grassian, V.H. Aggregation and dissolution of 4nm ZnO nanoparticles in aqueous environments: influence of pH, ionic strength, size, and adsorption of humic acid. Langmuir 2011, 27, 6059–6068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isibor, P.O.; Kayode-Edwards, I.I.; Oyewole, O.A.; Olusanya, C.S.; et al. Aquatic ecotoxicity of nanoparticles. In Environmental nanotoxicology: Combatting the minute contaminants. Springer Nature, 2024, Cham, pp. 135–159.

- Oriekhova, O.; Stoll, S. Effects of pH and fulvic acids concentration on the stability of fulvic acids–cerium (IV) oxide nanoparticle complexes. Chemosphere 2016, 144, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topuz, E.; Sigg, L.; Talinli, I. A systematic evaluation of agglomeration of Ag and TiO2 nanoparticles under freshwater relevant conditions. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 193, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Tang, N.; Guo, J.; Lu, L.; Li, N.; Hu, T.; Liang, J. The aggregation of natural inorganic colloids in aqueous environment: A review. Chemosphere 2022, 136805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.; Williams, P.L.; Diamond, S.A. Ecotoxicity of manufactured ZnO nanoparticles: A review. Environ. Poll. 2013, 172, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogra, R.; Roverso, M.; Di Bernardo, G.; Zanut, A.; et al. Metallic functionalization of magnetic nanoparticles enhances the selective removal of glyphosate, AMPA, and glufosinate from surface water. Environ. Sci. Nano 2023, 10, 2399–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeez, F.; Al-Hetlani, E.; Arafa, M.; Abdelmonem, Y.; et al. The effect of surface charge on photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue dye using chargeable titania nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Yu, W.; Yang, S.; Wan, Q. Understanding the relationship between pore size, surface charge density, and Cu2+ adsorption in mesoporous silica. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peijnenburg, W.J.G.M.; Baalousha, M.; Chen, J.; Chaudry, Q.; Kammer, F.; Kuhlbusch, T.A.J.; et al. A review of the properties and processes determining the fate of engineered nanomaterials in the aquatic environment. Critical Rev. Environ. Sci. and Technol. 2015, 45, 2084–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahaye, N.; Thwala, M.; Cowan, D.; Musee, N. Genotoxicity of metal based engineered nanoparticles in aquatic organisms: A review. Mutation Res. Rev Mutation Res. 2017, 773, 134–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, N.B.; Erkan, H.S.; Engin, G.O.; Bilgili, M.S. Nanoparticles in the aquatic environment: usage, properties, transformation and toxicity-A review. Process Safety Environ. Protection 2019, 130, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuvaneshwari, M.; Bairoliya, S.; Parashar, A.; Chandrasekaran, N.; Mukherjee, A. Differential toxicity of Al2O3 particles on Gram-positive and Gram-negative sediment bacterial isolates from freshwater. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 12095–12106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, C.; Tang, Y.; Yang, F.G.; Li, X.L.; Xu, S.; Fan, X.Y.; Huang, Y.Y.; Yang, Y.J. Cellular toxicity of TiO2 nanoparticles in anatase and rutile crystal phase. Biol. Trace. Elem. Res. 2011, 141, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, S.; Lin, S.; Ji, Z.; Thomas, C.R.; Li, L.; Mecklenburg, M.; Meng, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Xia, T. Surface defects on plate-shaped silver nanoparticles contribute to its hazard potential in a fish gill cell line and zebrafish embryos. ACS nano 2012, 6, 3745–3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalman, J.; Paul, K.B.; Khan, F.R.; Stone, V.; Fernandes, T.F. Characterisation of bioaccumulation dynamics of three differently coated silver nanoparticles and aqueous silver in a simple freshwater food chain. Environ. Chem. 2015, 12, 662–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkas, J.; Bergum, S.; Nilsen, E.W.; Olsen, A.J.; et al. The impact of TiO2 nanoparticles on uptake and toxicity of benzo (a) pyrene in the blue mussel (Mytilus edulis). Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 511, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, D.; Alarifi, S.; Kumar, S.; Ahamed, M.; Siddiqui, M.A. Oxidative stress and genotoxic effect of zinc oxide nanoparticles in freshwater snail Lymnaea luteola L. Aquat. Toxicol. 2012, 124, 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Liu, W.; Slaveykova, V.I. Effects of mixtures of engineered nanoparticles and metallic pollutants on aquatic organisms. Environ. 2020, 7, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, E.; Piccapietra, F.; Wagner, B.; Marconi, F.; et al. Toxicity of silver nanoparticles to Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 8959–8964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, S.; Liu, Z.; Hu, Y.; Peng, R.; et al. Location-dependent occurrence and distribution of metal-based nanoparticles in bay environments. J. of Hazardous Materials 2024, 476, 134972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, T.; Li, P.; Wang, H.; Li, T.; Jiang, G. Identification and prioritization of environmental organic pollutants: From an analytical and toxicological perspective. Chemical Reviews 2023, 123, 10584–10640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felix, L.C.; Ede, J.D.; Snell, D.A.; Oliveira, T.M.; et al. Physicochemical properties of functionalized carbon-based nanomaterials and their toxicity to fishes. Carbon 2016, 104, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, J.P.; Baretta, J.F.; Santos, F.; Paino, I.M.M.; Zucolotto, V. Toxicological effects of graphene oxide on adult zebrafish (Danio rerio). Aquatic Toxicol. 2017, 186, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabo-Attwood, T.; Unrine, J.M.; Stone, J.W.; Murphy, C.J.; et al. Uptake, distribution and toxicity of gold nanoparticles in tobacco (Nicotiana xanthi) seedlings. Nanotoxicology 2012, 6, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, C.M.; Peralta-Videa, J.R.; Gardea-Torresdey, J.L. Chemistry, biochemistry of nanoparticles, and their role in antioxidant defense system in plants. In Nanotechnology and Plant Sciences, Siddiqui, M.H., Al-Whaibi, M., Mohammad, F. (eds). Springer, Cham., 2015, pp. 1–17.

- Gardea-Torresdey, J.L.; Rico, C.M.; White, J.C. Trophic transfer, transformation, and impact of engineered nanomaterials in terrestrial environments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 2526–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodhi, G.K.; Wijesekara, T.; Kumawat, K.C.; Adhikari, P.; et al. Nanomaterials–plants–microbes interaction: plant growth promotion and stress mitigation. Frontiers in Microbiology 2025, 15, 1516794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabet, S.G.; Ahmad, M.A. Unraveling the role of nanoparticles in improving plant resilience under environmental stress condition. Plant and Soil 2024, 503, 313–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, M.; Srivastav, A.; Gandhi, S.; Rao, S.; et al. Monitoring of engineered nanoparticles in soil-plant system: A review. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2019, 11, 100218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, M.; Gowtham, H.G.; Singh, S.B.; Shilpa, N.; et al. Fate, bioaccumulation and toxicity of engineered nanomaterials in plants: Current challenges and future prospects. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 811, 152249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priester, J.H.; Ge, Y.; Mielke, R.E.; Horst, A.M.; et al. Soybean susceptibility to manufactured nanomaterials with evidence for food quality and soil fertility interruption. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012, 109, E2451–E2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Sun, Y.; Ji, R.; Zhu, J.; et al. TiO2 and ZnO nanoparticles negatively affect wheat growth and soil enzyme activities in agricultural soil. J. Environ. Monit. 2011, 13, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phogat, N.; Khan, S.A.; Shankar, S.; Ansary, A.A.; Uddin, I. Fate of inorganic nanoparticles in agriculture. Adv. Mat. Lett. 2016, 7, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H. Metal based nanoparticles in agricultural system: behavior, transport, and interaction with plants. Chem. Speciat. Bioavailab. 2018, 30, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, V.; Minkina, T.; Sushkova, S.; Behal, A.; et al. ZnO and CuO nanoparticles: a threat to soil organisms, plants, and human health. Environ. Geochem. Health. 2020, 42, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, A.A.; Adeleye, A.S.; Conway, J.R.; Garner, K.L.; et al. Comparative environmental fate and toxicity of copper nanomaterials. NanoImpact 2017, 7, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, R.; Wilkinson, K.J.; Sauvé, S. Partitioning of silver and chemical speciation of free Ag in soils amended with nanoparticles. Chem. Cent. J. 2013, 7, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Tong, H.; Shen, C.; Sun, L.; et al. Bioavailability and translocation of metal oxide nanoparticles in the soil-rice plant system. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 713, 136662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, B.; Rizvi, A.; Ali, K.; Lee, J.; et al. Nanoparticles in the soil–plant system: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 1545–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, P.K.; Kumar, V.; Lee, S.; Raza, N.; et al. Nanoparticle-plant interaction: implications in energy, environment, and agriculture. Environ. Int. 2018, 119, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauter, M.S.; Zucker, I.; Perreault, F.; Werber, J.R.; Kim, J.; Elimelech, M. The role of nanotechnology in tackling global water challenges. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkina, T.; Rajput, V.; Fedorenko, G.; Fedorenko, A.; et al. Anatomical and ultrastructural responses of Hordeum sativum to the soil spiked by copper. Environ. Geochem. Health. 2020, 42, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajput, V.; Minkina, T.; Fedorenko, A.; Sushkova, S.; et al. Toxicity of copper oxide nanoparticles on spring barley (Hordeum sativum distichum). Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 645, 1103–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, P.R.; Shaikh, S.S.; Sayyed, R.Z. Modified chrome azurol S method for detection and estimation of siderophores having affinity for metal ions other than iron. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 1, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Keller, A.A. Interactions, transformations, and bioavailability of nano-copper exposed to root exudates. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 9774–9783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Dong, S.; Sun, Y.; Gao, B.; et al. Graphene oxide-facilitated transport of levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin in saturated and unsaturated porous media. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 348, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, Q.; Yousaf, B.; Ali, M.U.; Munir, M.A.M.; et al. Transformation pathways and fate of engineered nanoparticles (ENPs) in distinct interactive environmental compartments: A review. Environ. Int. 2020, 138, 105646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Avellan, A.; Laughton, S.; Vaidya, R.; et al. CuO nanoparticle dissolution and toxicity to wheat (Triticum aestivum) in rhizosphere soil. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 2888–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strekalovskaya, E.I.; Perfileva, A.I.; Krutovsky, K.V. Zinc Oxide nanoparticles in the “Soil–Bacterial community–Plant” system: Impact on the stability of soil ecosystems. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qarachal, J.F.; Yagoubi, A.; Moosawi-Jorf, S.A. Engineered nanoparticles in soil ecosystems: Impacts on micro and macro-organisms, benefits, and risks. J. of Engg. in Industrial Res. 2025, 6, 261–274. [Google Scholar]

- Pittol, M.; Tomacheski, D.; Simões, D.N.; Ribeiro, V.F.; Santana, R.M.C. Macroscopic effects of silver nanoparticles and titanium dioxide on edible plant growth. Environ. Nanotechnol Monitor. Manag. 2017, 8, 127–133. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, A.A.; Huang, Y.; Nelson, J. Detection of nanoparticles in edible plant tissues exposed to nano-copper using single-particle ICP-MS. J. Nanopart. Res. 2018, 20, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gómez, C.; Obrador, A.; González, D.; Babín, M.; Fernández, M.D. Comparative study of the phytotoxicity of ZnO nanoparticles and Zn accumulation in nine crops grown in a calcareous soil and an acidic soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 644, 770–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, C.P.; King, G.; Plocher, M.M.; Storm, L.R.; et al. Germination and early plant development of ten plant species exposed to titanium dioxide and cerium oxide nanoparticles. Environ. Toxicol Chem. 2016, 35, 2223–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanık, F.; Vardar, F. Oxidative stress response to aluminum oxide (Al2O3) nanoparticles in Triticum aestivum. Biology 2018, 73, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassaan, M.A.; Elkatory, M.R.; El-Nemr, M.A.; et al. Optimization strategy of Co3O4 nanoparticles in biomethane production from seaweeds and its potential role in direct electron transfer and reactive oxygen species formation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.N.; Arifa, K.; Asmatulu, E. Methodologies of e-waste recycling and its major impacts on human health and the environment. Int. J. Environ. Waste Manag. 2021, 27, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaminathan, P.D.; Uddin, M.N.; Wooley, P.; Asmatulu, R. Fabrication and biological analysis of highly porous PEEK bionanocomposites incorporated with carbon and hydroxyapatite nanoparticles for biological applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.N.; Desai, F.; Asmatulu, E. Review of bioaccumulation, biomagnification, and biotransformation of engineered nanomaterials, In Nanotoxicology and Nanoecotoxicology Vol 2. Environmental Chemistry for a Sustainable World 67, Kumar, V.; Guleria, P.; Ranjan, S.; Dasgupta, N.; Lichtfouse, E. (eds), Springer, Cham, 2021, 133–164.

- Bhuyan, M.S.A.; Uddin, M.N.; Islam, M.M.; Bipasha, F.A.; Hossain, S.S. Synthesis of graphene. Int. Nano Letters, 2016, 6, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A.; Kumar, A. Ecotoxicity analysis and risk assessment of nanomaterials for the environmental remediation. Macromolecular Symposia 2023, 410, 2100438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, K.; Bleeker, E.A.J.; Baker, J.; Bouillard, J.; et al. A roadmap to strengthen standardisation efforts in risk governance of nanotechnology. NanoImpact 2023, 32, 100483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wu, C.; Wang, Q. Toxicity of engineered nanoparticles in food: sources, mechanisms, contributing factors, and assessment techniques. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 13142–13158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, M.; Kumar, R. Regulatory issues in nanotechnology. In Nanotechnology theranostics in livestock diseases and management, Singapore, Springer Nature, Singapore, 2024, pp. 765–788.

- Isibor, P.O. Regulations and policy considerations for nanoparticle safety. In Environmental nanotoxicology: combatting the minute contaminants, Cham, 2024, Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Amutha, C.; Gopan, A.; Pushbalatatha, I.; Ragavi, M.; Reneese, J.A. Nanotechnology and governance: regulatory framework for responsible innovation. In Nanotechnology in Societal Development, Singapore, Springer Nature, Singapore, 2024, pp. 481–503.

- Pandey, J.K.; Bobde, P.; Patel, R.K.; Manna, S. Disposal and Recycling Strategies for Nano-engineered Materials, 1st ed.; Elsevier, Cambridge, MA 02139, United States, 2024, pp. 1–170.

- Alizadeh, M.; Qarachal, J.F.; Sheidaee, E. Understanding the ecological impacts of nanoparticles: risks, monitoring, and mitigation strategies. Nanotechnol Environ Eng 2025, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Yadav, K. Exploring the effect of engineered nanomaterials on soil microbial diversity and functions: A review. J. Environ. Nanotechnol 2024, 13, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon-based ENPs | Carbon-based NPs are a class of engineered nanoparticles derived from carbon atoms, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), graphene, carbon quantum dots, and fullerenes. | CNTs, fullerenes, graphene, and nanodiamonds. |

| Metal/metal oxide-based ENPs | Metal-based ENPs are synthetic nanomaterial composed of pure metals or their compounds (e.g., metal oxides) with at least one dimension between 1 and 100 nanometers. | Gold NPs (AuNPs), Silver NPs (AgNPs), and Iron Oxide NPs. |

| Ceramic-based ENPs | Ceramic-based ENPs are synthetic inorganic materials, typically composed of ceramic compounds like metal oxides, carbides, and nitrides. These NPs made from silicon, titanium, or aluminum, are intentionally manufactured to possess distinct physical and chemical characteristics that are not found in larger ceramic structures. | Silicon Dioxide (SiO2) NPs, Alumina (Al2O3) NPs, and Titanium Dioxide (TiO2) NPs. |

| Semiconductor ENPs | Semiconductor ENPs are synthetically created nanomaterials (1–100 nm) designed to possess novel optical and electronic properties. These characteristics, which are absent in the parent bulk material, are a direct consequence of the quantum confinement effect—a phenomenon that allows for the precise control of a nanoparticle’s light-emitting and electronic features simply by manipulating its size. | Cadmium-based Quantum Dots (CdSe,CdS,CdTe), Indium Phosphide (InP) Quantum Dots, and Silicon (Si) Quantum Dots. |

| Polymeric-based ENPs | Polymers are used as building blocks to create a type of synthetic nanoparticle called a polymeric-based ENPs. These NPs are between 1-1000 nm in size and manufactured for a particular function, such as acting as a delivery vehicle for drugs, genes, or other therapeutic molecules. Their main goal is to shield the encapsulated substance and transport it to a precise location within the body for the treatments. | Poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) NPs, Poly (ethylene glycol) (PEG) NPs, and Chitosan NPs. |

| Lipid-based ENPs | Lipid-based ENPs are a class of fabricated nanostructures (10–1,000 nm) that are purposefully built from lipid components. These spherical vesicles are manufactured to fulfill specific roles, often in drug delivery. | Liposomes, Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine (Comirnaty®), and Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine (Spikevax®). |

| Composite ENPs | Composite ENPs are made of two or more distinct nanoscale components to create a single structure with special physical and chemical properties. Different components of these NPs interact at nanoscale, resulting in superior properties compared to the individual components alone. | Gold-Silica NPs (Au@SiO2), Iron Oxide NPs with polymer coating (Fe3O4@Polymer). |

| Parameters | Impacts of toxicity | Summary of the study | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size of ENPs | The strength of toxicity is inversely related to the ENPs’ size. | Al2O3 NP was found to show low toxicity to bacteria in contrast with the same Al2O3 NPs of a size of less than 50 nm. | [58] |

| Crystal structure | Cytotoxicity and genotoxicity are associated with the ENPs’ crystal structure. | The toxicity of Anatase nTiO2 due to oxidative stress was found to be greater than that of rutile nTiO2. | [59] |

| Surface charge | Surface charge controls the toxicity of NPs by affecting the agglomeration rate. | The silver NPs’ toxicity was discovered to be dependent on surface charge. | [57] |

| Morphology | Surface charge controls the toxicity of NPs by affecting the agglomeration rate. | Plate-shaped silver NPs have higher toxicity effects on fish gills and zebrafish embryos in contrast with spheres or wire-shaped NPs. | [60] |

| Surface coating | The ENP’s toxicity effects increase or decrease according to the chemistry of their coatings of ENPs. | PVP or citrate-coated silver NPs were more toxic than PEG-coated silver NPs. | [61] |

| Co-pollutant | Inadequate information is found regarding the interaction of nanoparticles with other pollutants in the aquatic media. | Exposure of the blue mussel to both TiO2 and benzo (a) pyrene resulted in greater chromosomal damage while inducing lower results in individual exposure. | [62] |

| Exposure duration and concentration | Both the exposure duration and concentration influence the toxicity of ENPs in the aquatic system. | It is found that the toxicity effects on Lymnaea luteola, an aquatic snail, of exposure to nZnO have a dependency on the exposure duration and concentration. | [63] |

| ENPs | Size and Dose Rate | Test Crop(s) | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag | 10 nm and 0.001-10000 mg L-1 |

Raphanus sativus, Allium cepa | The growth of plant roots was inhibited. | [97] |

| CuO | 20-100 nm and 34.4 g m2 |

Brassica oleracea var. viridis, Brassica oleracea var. sabella & Lactuca sativa | Substantial amounts of CuO accumulated on the surface of lettuce leaves and subsequently on kale and collard greens. | [98] |

| ZnO | <100 nm and 20-900 mg kg-1 soil |

Triticum aestivum, Pisum sativum, Zea mays, Lactuca sativa, Raphanus sativus, Beta vulgaris, Solanum lycopersicum, and Crocus sativus | Toxic effects of ZnO NPs depend on plant species; ZnO NPs reduced the availability of Zine while interacting with calcareous soil and as a result toxicity to accumulate biomass by wheat, beet, and cucumber, whereas maize, pea, and wheat showed resistance in acidic type soil. | [99] |

| TiO2 | 25 nm and 250–1000 mg L-1 |

Crocus sativus, Brassica oleracea var. capitata, Avena sativa | Growth of roots of edible crops such as corn, oats, cabbage, lettuce, etc. were inhibited and germination of cucumber and soybean was reduced. | [100] |

| Al2O3 | 13 nm and 50 mg L-1 |

Triticum aestivum | H2O2 content, lipid peroxidation, and superoxide dismutase activities were increased; the production of anthocyanin and photosynthetic pigment was reduced. | [101] |

| Feature | REACH (EU) | EPA/TSCA (U.S.) | OECD (Global) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary role | Direct regulation/ market access |

Direct regulation/risk management | Test Method/policy harmonization |

| Core principle | Precautionary principle | Risk-based assessment | Mutual acceptance of data (MAD) |

| ENP requirements | Explicitly addressed with nano-specific amendments (mandatory data) | Case-by-case review, limited specific reporting rules (risk-triggered data) | Develops ENP-adapted test guidelines and guidance documents |

| Strength | Comprehensive data generation, mandatory nano-specific information | Flexible, fast control of new chemicals (consent orders) | Standardized methods, reduced animal testing, global consistency |

| Limitation | Resource-intensive, slow to adapt, potential for underestimation of complex hazards | Requires demonstration of “unreasonable risk” before full data is mandated, relies on regulatory discretion | No direct regulatory power, lag between guideline creation and national adoption |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).