Submitted:

15 January 2025

Posted:

16 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Background and Context

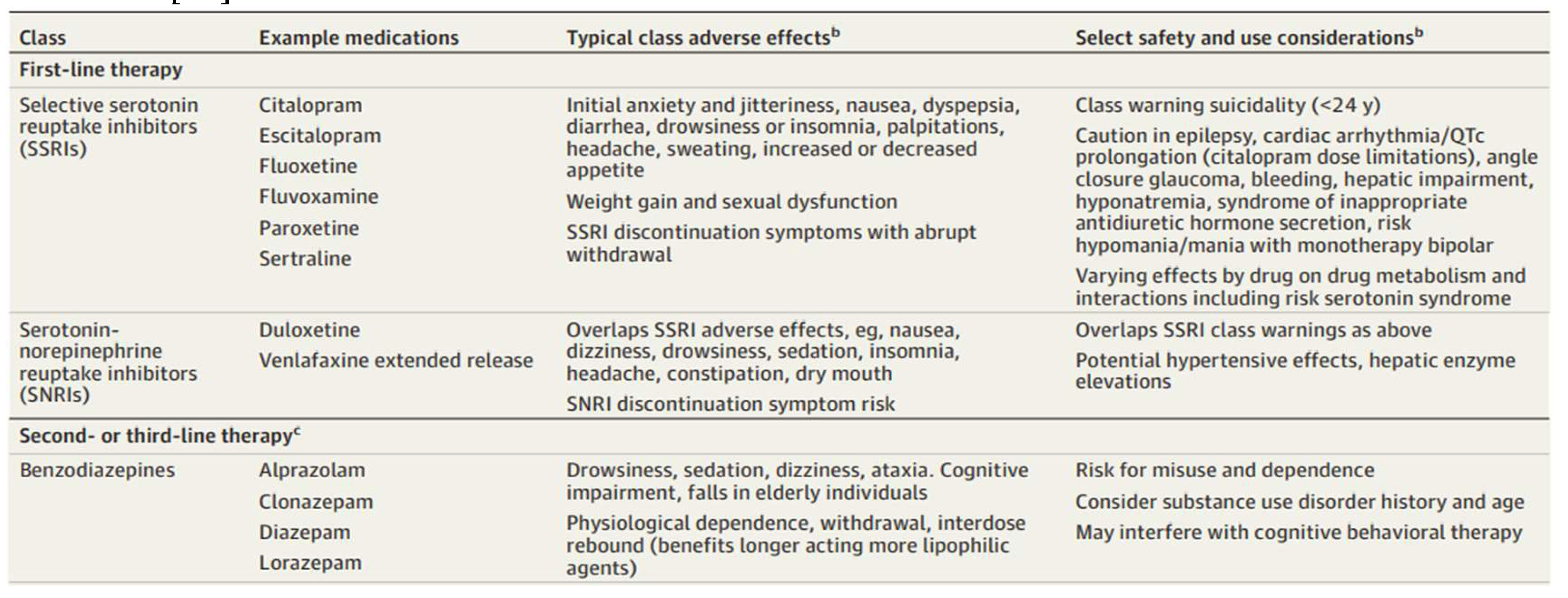

Overview of Pharmacologic Therapy for Anxiety Disorders [1]4

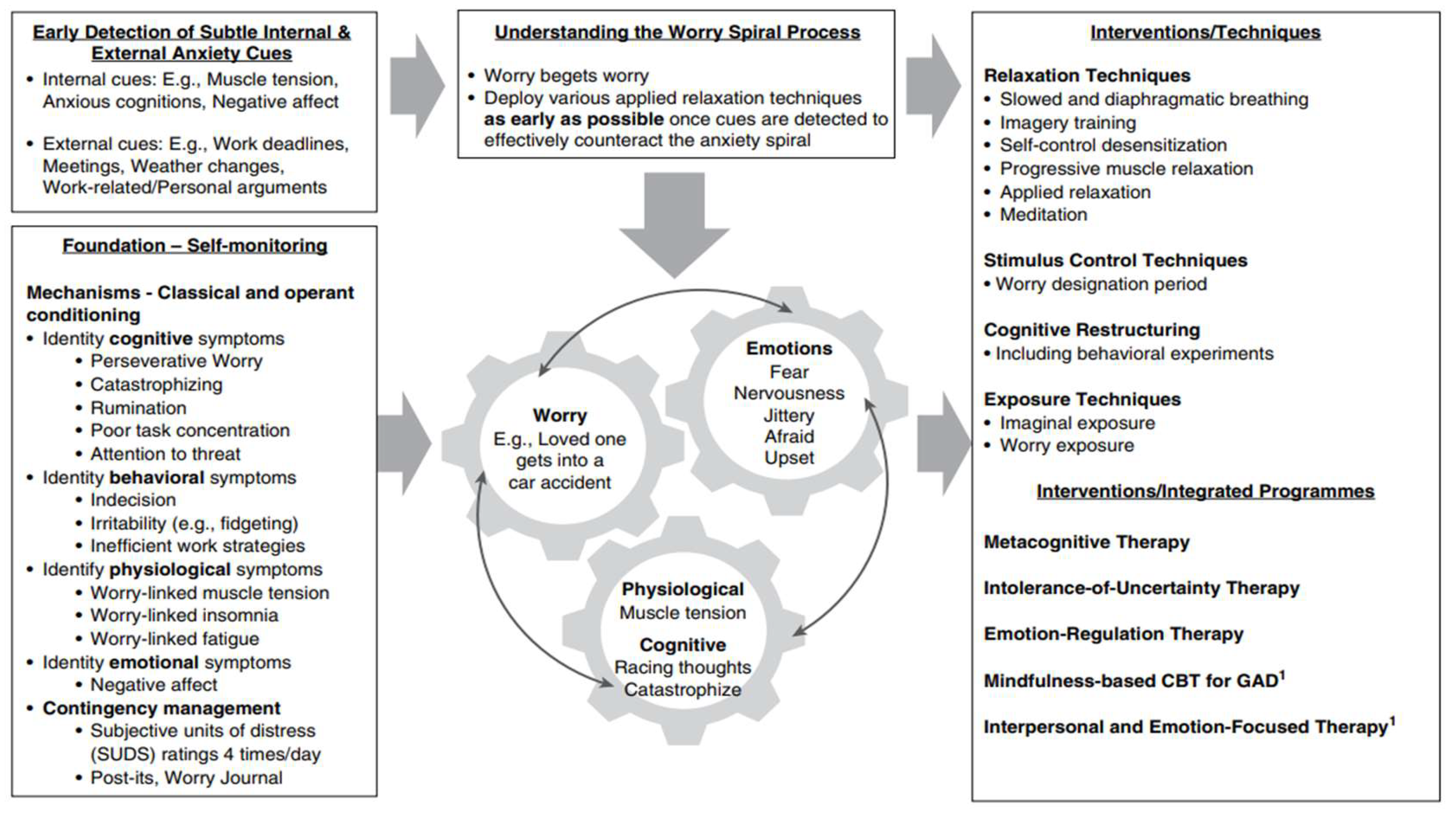

Integration of core principles, mechanisms, and techniques of CBT for GAD [17]

Problem Statement and Rationale

Significance and Purpose

Objectives

Scope and Limitations

Results

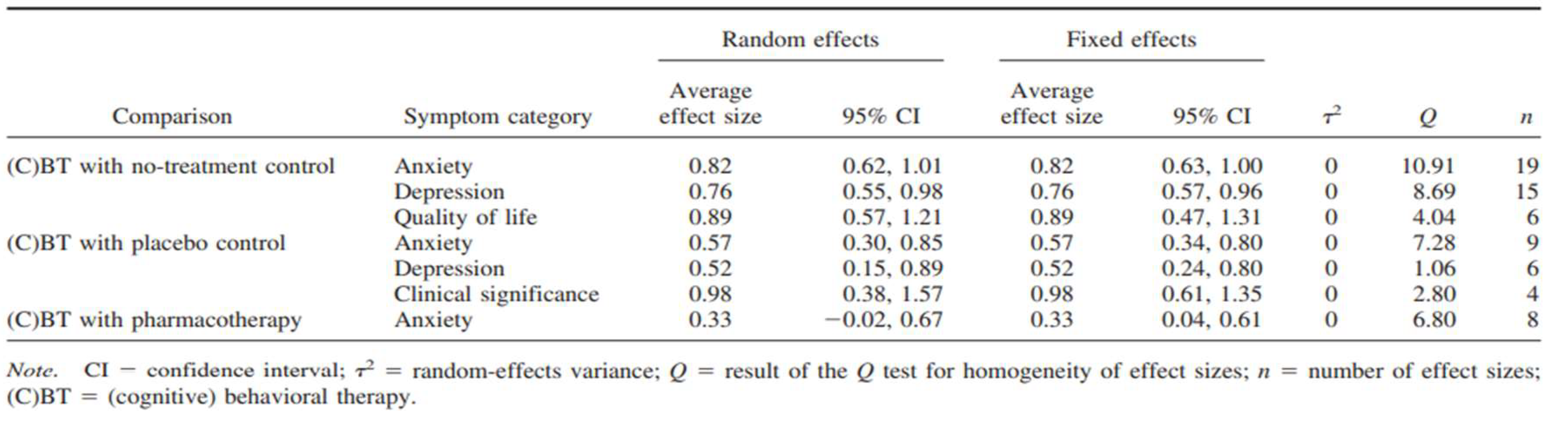

Average Effect Sizes for Posttest of the Symptom Categories Comparing Therapy Approaches [16]

Conclusions

Discussion

Restatement of Key Findings

Implications and Significance/ Connection to Objectives

Further Research

Limitations

Closing Statement

Methods

Search Strategy and Inclusion Criteria

Data extraction

Synthesis Method

Acknowledgements

References

- Goodwin, R.D.; Weinberger, A.H.; Kim, J.H.; Wu, M.; Galea, S. Trends in anxiety among adults in the United States, 2008–2018: Rapid increases among young adults. Journal of Psychiatric Research 2020, 130, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pashazadeh Kan, F.; Raoofi, S.; Rafiei, S.; Khani, S.; Hosseinifard, H.; Tajik, F.; Raoofi, N.; Ahmadi, S.; Aghalou, S.; Torabi, F.; Dehnad, A.; Rezaei, S.; Hosseinipalangi, Z.; Ghashghaee, A. A systematic review of the prevalence of anxiety among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Affective Disorders 2021, 293, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruscio, A.M.; Hallion, L.S.; Lim CC, W.; Jeon, Y.J.; Wang, L.; Tonillo, D. Cross-sectional comparison of the epidemiology of DSM-5 generalized anxiety disorder across the globe. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, S.; Stead, T.S.; Mangal, R.; Ganti, L. General anxiety disorder in youth: A national survey. Health Psychology Research 2022, 10, 39578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Means-Christensen, A.J.; Roy-Byrne, P.P.; Sherbourne, C.D.; Craske, M.G.; Stein, M.B. Relationships among pain, anxiety, and depression in primary care. Depression and Anxiety 2008, 25, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, M.; Newman, M.G. Generalized anxiety disorder. In M. Hersen, J. C. Thomas, & D. L. Segal (Eds.), Comprehensive Handbook of Personality and Psychopathology (pp. 101–122). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. 2006.

- Weisberg, R.B. Overview of generalized anxiety disorder: Epidemiology, presentation, and course. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 2006, 70 (Suppl 2), 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brawman-Mintzer, O.; Lydiard, R.B. Biological basis of generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 1997, 58, 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Adwas, A.A.; Jbireal, J.M.; Azab, A.E. Anxiety: Insights into signs, symptoms, etiology, pathophysiology, and treatment. East African Scholars Journal of Medical Sciences 2019, 2, 80–91. [Google Scholar]

- Nemeroff, C.B. The role of GABA in the pathophysiology and treatment of anxiety disorders. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 2003, 37, 133–146. [Google Scholar]

- Nutt, D.J. Overview of diagnosis and drug treatments of anxiety disorders. CNS Spectrums 2005, 10, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandelow, B.; Michaelis, S.; Wedekind, D. Treatment of anxiety disorders. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 2017, 19, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinclair, L.; Nutt, D. Anxiolytics. Psychiatry 2007, 6, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szuhany, K.L.; Simon, N.M. Anxiety disorders: A review. JAMA 2022, 328, 2431–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, S. Purpose and method of Vipassana meditation. The Humanistic Psychologist 1994, 22, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitte, K. Meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral treatments for generalized anxiety disorder: A comparison with pharmacotherapy. Psychological Bulletin 2005, 131, 785–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoyer, J.; Newman, M.G. (2020). Generalized anxiety disorder and worrying: A comprehensive handbook for clinicians and researchers. New York, NY: Springer.

- Carl, E.; Witcraft, S.M.; Kauffman, B.Y.; Gillespie, E.M.; Becker, E.S.; Cuijpers, P.; Powers, M.B. Psychological and pharmacological treatments for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD): A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy 2020, 49, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, A.F.; Barthel, A.L.; Hofmann, S.G. Comparing the efficacy of benzodiazepines and serotonergic anti-depressants for adults with generalized anxiety disorder: A meta-analytic review. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy 2018, 19, 883–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koszycki, D.; Benger, M.; Shlik, J.; Bradwejn, J. Randomized trial of a meditation-based stress reduction program and cognitive behavior therapy in generalized social anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy 2007, 45, 2518–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoge, E.A.; Bui, E.; Marques, L.; Metcalf, C.A.; Morris, L.K.; Robinaugh, D.J.; Simon, N.M.; Palitz, S. A. Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation for generalized anxiety disorder: Effects on anxiety and stress reactivity. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 2013, 74, 16662–16668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoge, E.A.; Bui, E.; Palitz, S.A.; Schwarz, N.R.; Owens, M.E.; Johnston, J.M.; Simon, N.M. The effect of mindfulness meditation training on biological acute stress responses in generalized anxiety disorder. Psychiatry Research 2018, 262, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidan, F.; Johnson, S.K.; Gordon, N.S.; Goolkasian, P. Effects of brief and sham mindfulness meditation on mood and cardiovascular variables. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 2010, 16, 867–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeidan, F.; Martucci, K.T.; Kraft, R.A.; McHaffie, J.G.; Coghill, R.C. Neural correlates of mindfulness meditation-related anxiety relief. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 2014, 9, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).