Submitted:

16 January 2025

Posted:

16 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction (A Brief Review)

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

- 4.

- Tumor necrosis factor α1 (TNFα1) [13]

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Sample Collection

2.2. Immunohistochemistry

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

Kaplan-Meier Survival Curves and Comparisons Among Groups (Log Rank Test)

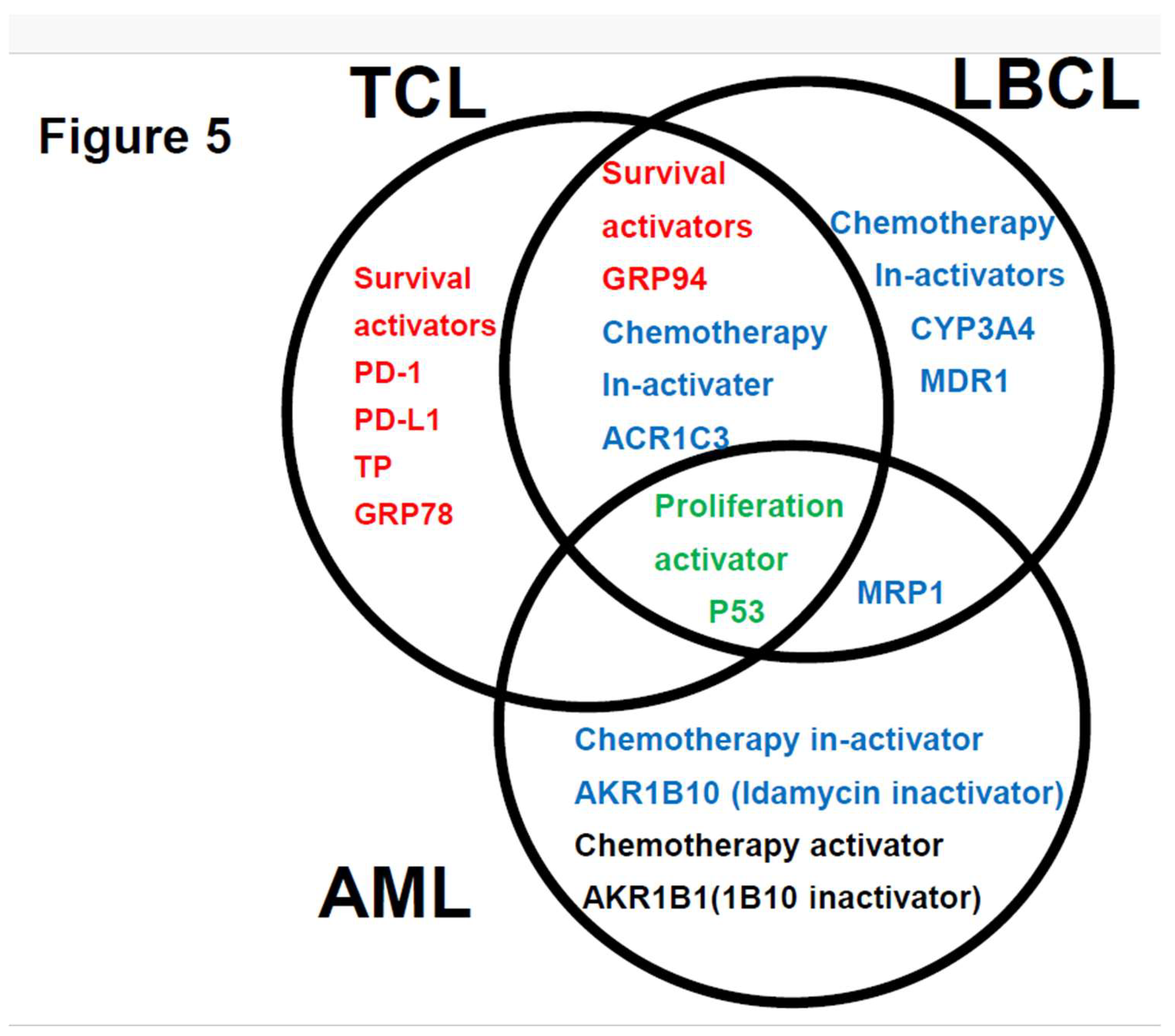

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Ethics approval statement

Acknowledgments

Competing interests

Abbreviations

| AML | Acute myeloid leukemia |

| IHC | Immunohistochemical staining |

| MRP1 | Multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 |

| AKR1B10 | Aldo-keto reductase family 1 member B10 |

| AKR1B1 | Aldo-keto reductase family 1 member B1 |

| AKR1C3 | Aldo-keto reductase family 1 member C3 |

| OS | Overall survival |

| ELN | European Leukemia net |

| LBCL | Large B-cell lymphoma |

| TCL | Aggressive T-cell lymphoma |

| GRP94 | Glucose-regulated protein 94 |

| GRP78 | Glucose-regulated protein 78 |

| B-ALL | B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia |

| TGFβ1 | Transforming growth factor β1 |

| TNFα1 | Tumor necrosis factor α1 |

| TNFR | Tumor necrosis factor receptor |

| PD-1 | Programmed cell death-1 |

| PD-L1 | Programmed cell death–ligand 1 |

| ENT1 | Equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 |

| MDR1 | Multidrug resistance 1 |

| MRP1 | Multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 |

| CYP3A4 | Cytochrome P450 3A4 |

| FLT3 | fms related receptor tyrosine kinase 3 |

| TKI | Tyrosin kinase inhibitor |

| CYP2B6 | Cytochrome P450 2B6 |

| AKR1C3 | Aldo-keto reductase family 1 member C3 |

| AKR1B10 | Aldo-keto reductase family 1 member B10 |

| AKR1B1 | Aldo-keto reductase family 1 member B1 |

| TP | Thymidine phosphorylase |

| GST | Glutathione sulfate transferase |

| APL | Acute promyeloid leukemia |

| CBF | Core binding factor |

| CR | Complete remission |

| PD | Progressive disease |

| M | Months |

| NS | Not significant |

| NR | Not reached |

| MCL1 | Myeloid cell leukemia sequence 1 |

| Y | Years |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| BCL2 | B-cell/CLL lymphoma 2 |

| Del | Deletion |

| MTX | Methotrexate |

| C | Cyclophosphamide |

| OH | Oncovin hydroxyl doxorubicin; |

| HCCFA | 7-hydroxy-2-(4-methoxyphenylimino)-2H-chromene-3-carboxylic acid benzylamide |

| NSAIDs | N-phenyl-anthranilic acid, diclofenac, and glycyrrhetinic acid |

References

- Talha Bin Emran , Asif Shahriar, Ariful Islam, and Mohammad Mahmudul Hassan et al.. Multidrug Resistance in Cancer: Understanding Molecular Mechanisms, Immunoprevention and Therapeutic Approaches. Front Oncol 2022 Jun 23:12:891652.

- Hideaki Nitta , Haruko Takizawa, Toru Mitsumori , Hiroko Iizuka-Honma, Miki Ando and Masaaki Noguchi et al. Possible New Histological Prognostic Index for Large B-Cell Lymphoma. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6324. [CrossRef]

- Hideaki Nitta , Haruko Takizawa , Toru Mitsumori, Miki Ando , and Masaaki Noguchi et al. A New Histology-Based Prognostic Index for Aggressive T-Cell lymphoma: Preliminary Results of the "TCL Urayasu Classification" J Clin Med . 2024 Jun 30;13(13):3870. [CrossRef]

- Klaus H Metzeler, Tobias Herold, Jan Braess, and Karsten Spiekermann et al.. Spectrum and prognostic relevance of driver gene mutations in acute myeloid leukemia Blood . 2016 Aug 4;128(5):686-98. Epub 2016 Jun 10. [CrossRef]

- Sebastian E. Koschade, Brandts, and Olivier Ballo et al. Relapse surveillance of acute myeloid leukemia patients in first remission after consolidation chemotherapy: diagnostic value of regular bone marrow aspirations. Annals of Hematology 2022, 101:1703–1710.

- Xiaofeng Duan, Stephen Iwanowycz, Soo Ngoi, Megan Hill 2 Qiang Zhao and Bei Liu et al. Molecular Chaperone GRP94/GP96in Cancers: Oncogenesis and Therapeutic Target. . Front Oncol. 2021. PMID: 33898309 Free PMC article. Review.

- Lee AS. Glucose-regulated proteins in cancer: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014 Apr;14(4):263-76. [CrossRef]

- Amos Olalekan Akinyemi , Xiaoqi Liu , and Zhiguo Li et al. Unveiling the dark side of glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78) in cancers and other human pathology: a systematic review. Mol Med . 2023 Aug 21;29(1):112. [CrossRef]

- Tania Angeles-Floriano, Guadalupe Rivera-Torruco, Alhelí Bremer, Lourdes Alvarez-Arellano and Ricardo Valle-Rios et al. Cell surface expression of GRP78 and CXCR4 is associated with childhood high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia at diagnostics. Scientific Reports 2022 12:2322 | . [CrossRef]

- Nikhil Hebbar , Rebecca Epperly,Stephen Gottschalk, and M Paulina Velasquez et al.. CAR T cells redirected to cell surface GRP78 display robust anti-acute myeloid leukemia activity and do not target hematopoietic progenitor cells Nat Commun 2022 Jan 31;13(1):587. [CrossRef]

- Sulsal Haque and John C Morris. Transforming growth factor-β: A therapeutic target for cancer. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017 Aug 3;13(8):1741-1750. [CrossRef]

- Matthew A. Timmins and Ingo Ringshausen. Transforming Growth Factor-Beta Orchestrates Tumour and Bystander Cells in B-Cell Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Cancers 2022, 14, 1772. [CrossRef]

- H T Idriss, and J H Naismith TNF alpha and the TNF receptor superfamily: structure-function relationship(s) Microsc Res Tech 2000 Aug 1;50(3):184-95. [CrossRef]

- H Takizawa, M Fujishiro, S Tomita, T Mitsumori, H Nitta, H Iizuka-Honma, M Ando, and M Noguchi. et al. Role of TGF-beta1 and TNF-alpha1 produced by neoplastic cells in the pathogenesis of fibrosis in patients with hematologic neoplasms. J Clin Exp Hematop . 2023 Jun 28;63(2):83-89. [CrossRef]

- Prada JP, Wangorsch G, Lang, Dandekar T, and Wajant H.et al. A systems-biology model of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) interactions with TNF receptor 1 and 2. Bioinformatics. 2021 May 5;37(5):669-676. PMID: 32991680. [CrossRef]

- F Vinante, A Rigo, and M Chilosi, G Pizzolo et al. Serum levels of p55 and p75 soluble TNF receptors in adult acute leukaemia at diagnosis: correlation with clinical and biological features and outcome. Br J Haematol 1998 Sep;102(4):1025-34. [CrossRef]

- Adam Cisterne, Rana Baraz, Kenneth F Bradstock, and Linda J Bendall et al. . Silencer of death domains controls cell death through tumour necrosis factor-receptor 1 and caspase-10 in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. PLoS One 2014 Jul 25;9(7):e103383. [CrossRef]

- Huizhen Cao, Tianyu Wu, Yunxiao Sun, and Youjie Li et al.. Progress of research on PD-1/PD-L1 in leukemia Front Immunol 2023 Sep 26:14:1265299. [CrossRef]

- Ayfer Geduk, Elif B Atesoglu, and Sibel Balcı.. Programmed Cell Death Ligand 1 Expression Level and Prognostic Significance in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2022 Jul;38(3):464-472. Epub 2021 Jul 27. [CrossRef]

- Julie B Mortensen, Ida Monrad, Peter Kamper, and Francesco d'Amore et al. Soluble programmed cell death protein 1 (sPD-1) and the soluble programmed cell death ligands 1 and 2 (sPD-L1 and sPD-L2) in lymphoid malignancies Eur J Haematol . 2021 Jul;107(1):81-91. Epub 2021 Apr 12. [CrossRef]

- Myrna Candelaria, Carmen Corrales-Alfaro, Silvia Vidal-Millán, Luis A Herrera et al. Expression Levels of Human Equilibrative Nucleoside Transporter 1 and Deoxycytidine Kinase Enzyme as Prognostic Factors in Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia Treated with Cytarabine Chemotherapy . 2016;61(6):313-8. [CrossRef]

- Lenilton Silva da Silveira Júnior, Victor de Lima Soares, Valeria Soraya de Farias Sales, and André Ducati Luchessi et al. P-glycoprotein and multidrug resistance-associated protein-1 expression in acute myeloid leukemia: Biological and prognosis implications Int J Lab Hematol . 2020 Oct;42(5):594-603. [CrossRef]

- Desiree Kunadt, Christian Dransfeld, Markus Schaich, and Friedrich Stölzel et al . Multidrug-related protein 1 (MRP1) polymorphisms rs129081, rs212090, and rs212091 predict survival in normal karyotype acute myeloid leukemia Ann Hematol . 2020 Sep;99(9):2173-2180. Epub 2020 Jul 3. [CrossRef]

- Sabrina Copsel, Ariana Bruzzone ,Carina Shayo , and Carlos Davio et al. Multidrug resistance protein 4/ ATP binding cassette transporter 4: a new potential therapeutic target for acute myeloid leukemia Oncotarget. 2014 Oct 15;5(19):9308-21. [CrossRef]

- Yu-Ting Chang, Daniela Hernandez, Mark J Levis, and Richard J Jones et al. Role of CYP3A4 in bone marrow microenvironment-mediated protection of FLT3/ITD AML from tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Blood Adv. 2019 Mar 26;3(6):908-916. [CrossRef]

- Xuan Xiong, Dongke Yu, Hongtao Xiao, and Rongsheng Tong et al. Association between CYP2B6 c.516G >T variant and acute leukaemia. A protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (2021) 100:32.

- Kshitij Verma, Tianzhu Zang, Trevor M. Penning, and Paul C. Trippier, Potent and Highly Selective Aldo-Keto Reductase 1C3 (AKR1C3) Inhibitors Act as Chemotherapeutic Potentiators in Acute Myeloid Leukemia and T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. J Med Chem. 2019 April 11; 62(7): 3590–3616. [CrossRef]

- Brian Laffin and J. Mark Petrash. Expression of the aldo-ketoreductases AKR1B1 and AKR1B10inhumancancers. Front Pharmacol. 2012; 3: 104. [CrossRef]

- Penning TM, Jonnalagadda S, Trippier PC, and Rižner TL et al. Aldo-Keto Reductases and Cancer Drug Resistance. Pharmacol Rev. 2021 Jul;73(3):1150-1171. [CrossRef]

- Neslihan Büküm, Eva Novotná, Petr Solich, and Vladimír Wsól et all. Inhibition of AKR1B10-mediated metabolism of daunorubicin as a novel off-target effect for the Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitor dasatinib. Biochem Pharmacol 2021 Oct:192:114710. [CrossRef]

- Xingcao, Peter M Clifford, Rekha Bhat, Mini Abraham, and J Steve Hou et al. Thymidine phosphorylase expression in B-cell lymphomas and its significance: a new prognostic marker? Anal Quant Cytopathol Histpathol 2013 Dec;35(6):301-5.

- Nina Anensen, AnneMargrete Oyan, Oystein Bruserud and BjornTore Gjertsen et al. A distinct p53 protein isoform signature reflects the onset of induction chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia Clin Cancer Res . 2006 Jul 1;12(13):3985-92. [CrossRef]

- Ruby Tang , Amy Cheng , Fabian Guirales , and Wilson Yeh, c-MYC Amplification in AML. J Assoc Genet Technol . 2021;47(4):202-212.

- S M Davies, L L Robison, J A Ross, and J P Perentesis et al. Glutathione S-transferase polymorphisms and outcome of chemotherapy in childhood acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2001 Mar 1;19(5):1279-87. [CrossRef]

- Hartmut D€ohner,Andrew H. Wei, Agnieszka Wierzbowska and Bob L€oweb et al.. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2022 recommendations from an international expert panel on behalf of the ELN. Blood. 2022 Sep 22;140(12):1345-1377. [CrossRef]

- Ayaka Otsuki , Masaki Kumondai , Masamitsu Maekawa,and Nariyasu Mano et al. Plasma Venetoclax Concentrations in Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia Treated with CYP3A4 Inhibitors Yakugaku Zasshi . 2024;144(7):775-779. [CrossRef]

- Andrew H Wei , Andrew W Roberts, Phuong Khanh Morrow, and Anthony Stein. Targeting MCL-1 in hematologic malignancies: Rationale and progress Blood Rev . 2020 Nov:44:100672. Epub 2020 Feb 21. [CrossRef]

- Courtney D DiNardo, Brian A Jonas, Jalaja Potluri, and Keith W Pratz Azacitidine and Venetoclax in Previously Untreated Acute Myeloid Leukemia. N Engl J Med . 2020 Aug 13;383(7):617-629. [CrossRef]

- Satoshi Endo, Shuang Xia , Toshiyuki Matsunaga, and Akira Ikari. Synthesis of Potent and Selective Inhibitors of Aldo-Keto Reductase 1B10 and Their Efficacy against Proliferation, Metastasis, and Cisplatin Resistance of Lung Cancer Cells. J Med Chem . 2017 Oct 26;60(20):8441-8455. Epub 2017 Oct 13. [CrossRef]

- Megumi Kikuya, Kenta Furuichi , Kousei Ito, and Shigeki Aoki et al. Aldo-keto reductase inhibitors increase the anticancer effects of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in chronic myelogenous leukemia. J Pharmacol Sci . 2021 Sep;147(1):1-8. Epub 2021 May 23. [CrossRef]

- Satoshi Endo, Toshiyuki Matsunaga, Ossama El-Kabbani, and Akira Hara Selective inhibition of the tumor marker AKR1B10 by antiinflammatory N-phenylanthranilic acids and glycyrrhetic acid. Biol Pharm Bull . 2010;33(5):886-90. [CrossRef]

- Saba Kamil, Shaheen Kouser, Nehad Khan, and Ramsha Khan . Unveiling the Significance of MRP 1 in Achieving Complete Remission Following Induction Therapy in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Curr Mol Med . 2024 Jul 9. [CrossRef]

- B J Kuss, R G Deeley, and D F Callen. The biological significance of the multidrug resistance gene MRP in inversion 16 leukemias. Leuk Lymphoma. 1996 Feb;20(5-6):357-64. [CrossRef]

- Cen Zhang, Juan Liu, Tianliang Zhang, Wenwei Hu,and Zhaohui Feng. Gain-of-function mutant p53 in cancer progression and therapy J Mol Cell Biol 2020 Sep 1;12(9):674-687. [CrossRef]

- Kimberley M Hanssen , Michelle Haber, and Jamie I Fletcher Targeting multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 (MRP1)-expressing cancers: Beyond pharmacological inhibition Drug Resist Updat. 2021 Dec:59:100795. Epub 2021 Dec 10. [CrossRef]

- Amanda Tivnan, Zaitun Zakaria, Jann N Sarkaria , and Jochen H M et al. Prehn. Inhibition of multidrug resistance protein 1 (MRP1) improves chemotherapy drug response in primary and recurrent glioblastoma multiforme Front Neurosci . 2015 Jun 16:9:218. eCollection 2015. [CrossRef]

| Age > 60 years (%) | 13(37%) |

| Male (%) | 20(57%) |

| Chromosome | |

| CBF t(8;21) (q22;q22) n=7, inv(16) (p12q22) n=1 | 8 (23%) |

| Normal | 10 (29%) |

| Complex chromosome | 8 (23%) |

| Chromosome 7 deletion | 9(26%) |

| European Leukemia Net | |

| Favorable | 12 (34%) |

| Intermediate | 13(37%) |

| Adverse | 10(29%) |

| Induction chemotherapy | |

| Idarubicin + cytarabine | 35(100%) |

| Outcome | |

| CR | 27(77%) |

| Non-relapse | 18(51%) |

| Relapse | 9(26%) |

| PD | 8(23%) |

| Allogeneic transplantation | 10(29%) |

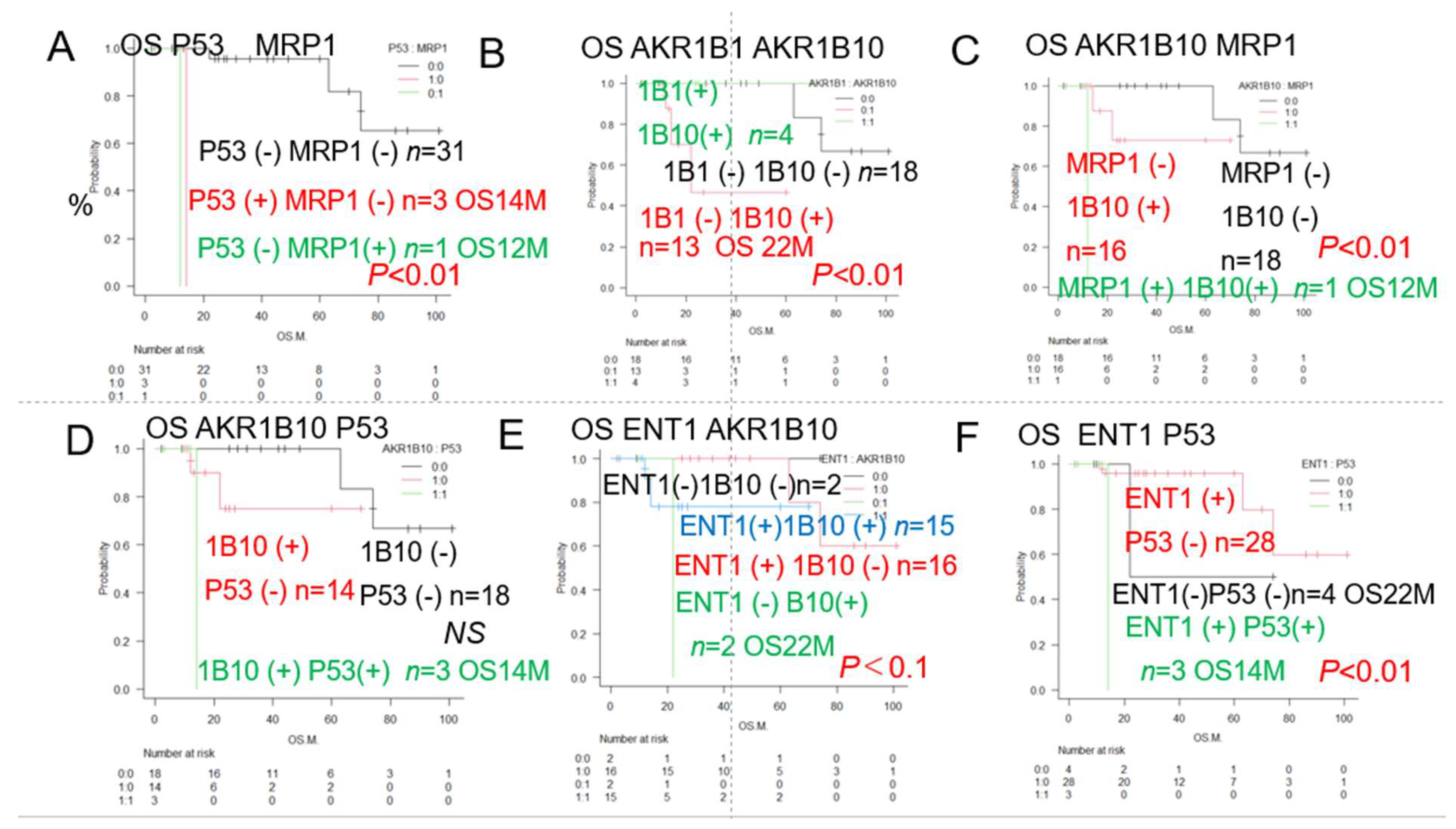

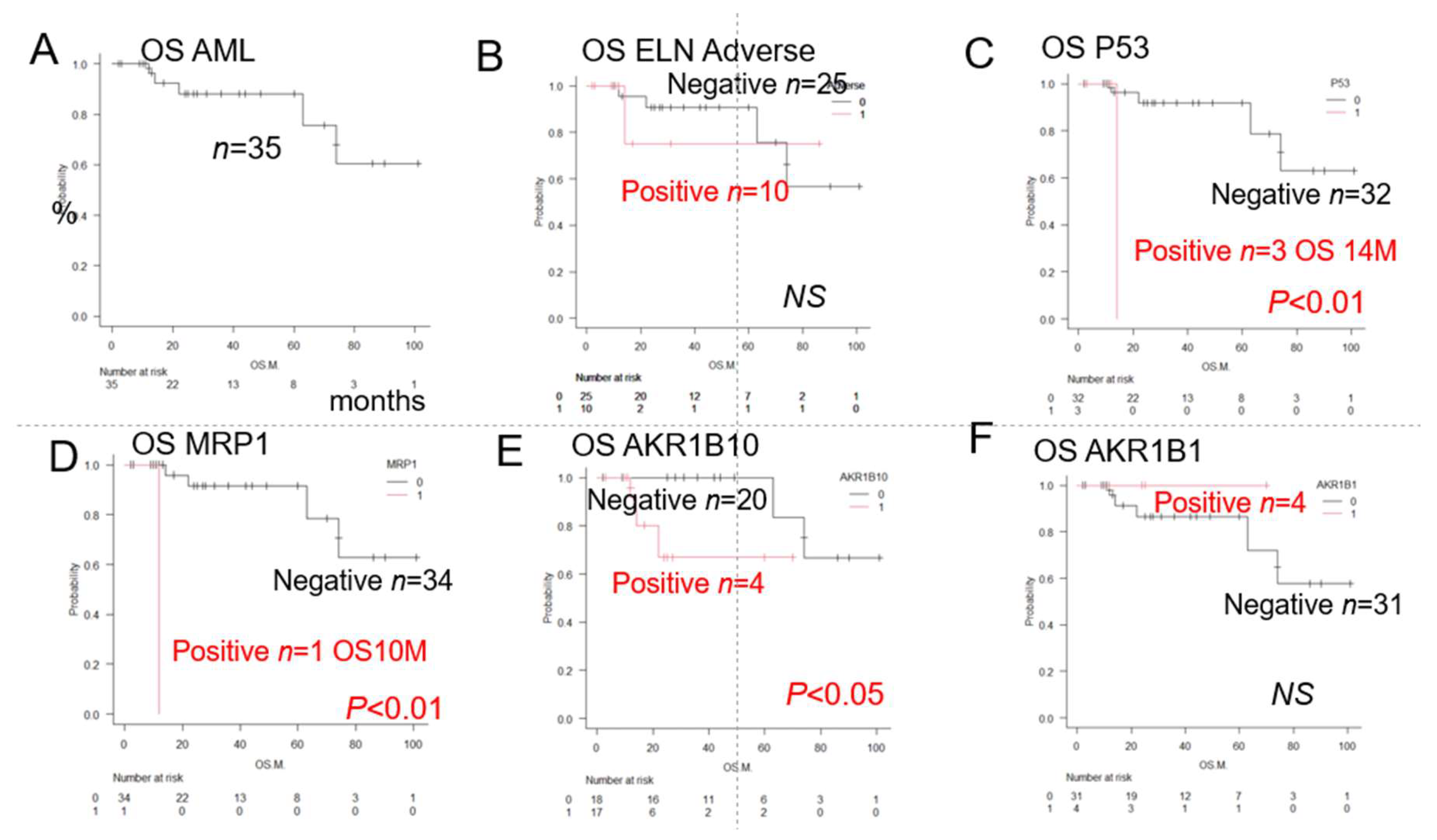

| Category | Factors (♯Significant difference:) | n | Median OS(months) | Years (Y) survival rate | p value | Figure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | AML | 35 | NR | 5Y 73% | 1A | |

| ELN | ELN Favourable group | 12 | NR | 5Y 93% | NS | |

| ELN Intermediate group | 13 | NR | 5Y76% | NS | ||

| ELN Adverse group | 10 | NR | 5Y72% | NS | 1B | |

| Chromosome abnormality | Deletion chromosome 7 | 9 | NR | 5Y78% | NS | |

| Complex chromosome | 8 | NR | 5Y73% | NS | ||

| 12 | 74 | 5Y62% | NS | |||

| ER stress proteins | GRP94 | 33 | NR | 5Y73% | NS | |

| TGFβ1 | 27 | 63 | 5Y90% | NS | ||

| GRP78 | 30 | NR | 5Y90% | NS | ||

| TNFα1 | 20 | NR | 5Y82% | NS | ||

| OH metabolic enzyme | AKR1C3 | 16 | NR | 5Y68% | NS | |

| AKR1B1 | 4 | NR | 5Y72% | NS | 1F | |

| AKR1B10 (♯) | 17 | NR | 5Y63% | *P<0.05 | 1E | |

| C metabolic enzyme | CYP2B6 | 0 | ||||

| CHOP metabolic enzyme | CYP3A4 | 5 | NR | 3Y73% | ||

| OH efflux pump | MDR1 | 5 | NR | 3Y72% | ||

| MRP1 (♯) | 1 | 12 | 1Y0% | *p<0.01 | 1D | |

| MTX efflux pump | MRP4 | 0 | NS | |||

| Immune checkpoint | PD-1 | 0 | NS | |||

| PD-L1 | 1 | NR | 5Y100% | NS | ||

| PD-L2 | 20 | 74 | 5Y74% | NS | ||

| Others | TP | 4 | 74 | 5Y100% | NS | |

| p53 (♯) | 3 | 14 | 2Y0% | *p<0.01 | 1C | |

| GST | 28 | NR | 5Y88% | NS | ||

| MYC | 28 | 74 | 5Y82% | NS | ||

| ENT-1 | 31 | NR | 5Y88% | NS | ||

| Fibrosis (Silver stain positive) | 11 | NR | 5Y74% | p>0.05 | ||

| BCL2 | 28 | 74 | 5Y84% | p>0.05 | ||

| MCL1 | 16 | NR | 5Y88% | p>0.05 | ||

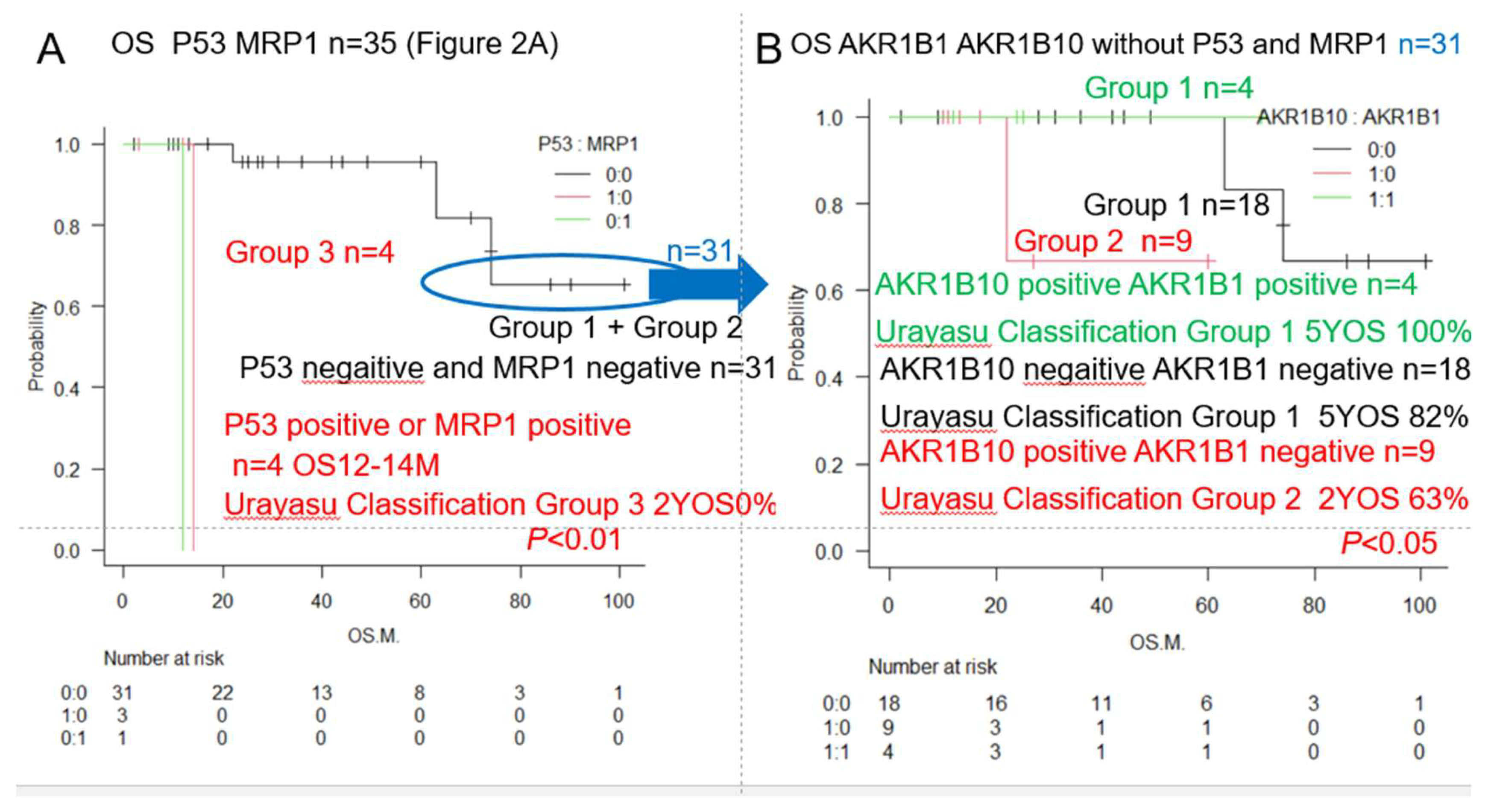

| Significant combination | ||||||

| Urayasu classification G3 | P53(+) or MRP1(+) (♯) | 4 | 13 | 2Y0% | **p<0.01 | 2A, 3,5 |

| Urayasu classification G2 | P53(-) MRP1(-) AKR1B10(+) 1B1(-) (♯) | 9 | NR | 2Y63% | *p<0.05 | 3,5 |

| Urayasu classification G1 | P53(-) MRP1(-) AKR1B10(-) 1B1(-) (♯) | 22 | NR | 5Y82% | *p<0.05 | 3,5 |

| Urayasu classification G1 | P53(-) MRP1(-) AKR1B10(+) 1B1(+) (♯) | 3 | NR | 5Y100% | *p<0.05 | 3,5 |

| P53 ENT1 (♯) P53(+) ENT1(+) | 3 | 14 | 2Y 0% | **p<0.01 | 2F | |

| MRP1 ENT1 (♯) MRP1(+) ENT1(+) | 1 | 12 | 2Y 0% | **p<0.01 | ||

| AKR1B10, AKR1B1 (♯) 1B10(+) 1B1(-) | 13 | 22 | 5Y 44% | **p<0.01 | 2B | |

| MRP1, AKR1B10 (♯) MRP1(+) 1B10(+) | 1 | 12 | 2Y 0% | **p<0.01 | 2C | |

| P53, BCL2 (♯) P53(+) BCL2(+) | 3 | 14 | 2Y 0% | *p<0.05 | ||

| P53, MCL1 (♯) P53(+) MCL1(+) | 3 | 14 | 2Y0% | **p<0.01 | ||

| P53, PD-L1 (♯) P53(+) PD-L1(-) | 2 | 14 | 2Y0% | **p<0.01 | ||

| P53, PD-L2 (♯) P53(+) PD-L2 (+) | 3 | 14 | 2Y0% | *p<0.05 | ||

| P53, CYP3A4 (♯) P53(+) CYP3A4(+) | 1 | NR | NR | **p<0.01 | ||

| P53, GRP78 (♯) P53(+) GRP78(+) | 3 | 14 | 2Y0% | **p<0.01 | ||

| P53, GRP94 (♯) P53,(+) GRP94(+) | 3 | 14 | 2Y0% | **p<0.01 | ||

| P53, AKR1C3 (♯) P53(+) AKR1C3(+) | 2 | 14 | 2Y0% | **p<0.01 | ||

| P53, TGF beta1 (♯) P53(+) TGF beta1(+) | 3 | 14 | 2Y0% | *p<0.05 | ||

| P53, MYC (♯) P53(+) MYC(+) | 3 | 14 | 2Y0% | *p<0.05 | ||

| P53, GST (♯) P53(+) GST(+) | 1 | NR | NR | *p<0.05 | ||

| Combinations with a tendancy towards association with the OS | ||||||

| Del 7, AKRB10(♯) Del 7(+) 1B10(+) | 6 | 14 | 2Y 0% | NS | ||

| BCL2, MCL1 | 23 | NS | ||||

| AKR1B10, P53 | 35 | NS | ||||

| ENT1, AKR1B10 | NS | 2E | ||||

| P53, AKR1B10 P53(+) AKR1B10(+) | 3 | 14 | 2Y 0% | NS | 2D |

| Classification | Group 1 (Favorable) | Group 2 (Intermediate) | Group 3 (Adverse) | Figure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AML Urayasu | P53(-)MRP(-)AKR1B10(+) | P53(-)MRP(-)AKR1B10(+) | P53(+) or MRP1(+) | 1CDEF |

| Classification | AKR1B1(+) or | AKR1B1(-) | 2AB3AB | |

| P53(-)MRP(-)AKR1B10(-) | ||||

| AKR1B1(-) | ||||

| Cases n=22 (63%) | Cases n=9 (26%) | Cases n=4 (11%) | ||

| OS 5Y 82%-100% | OS 2Y 63% | OS 2Y 0% | ||

| Median OS NR | Median OS NR | Median OS 12-14M | ||

| ELN AML risk | Cases n=562 (37%) | Cases n=355 (23%) | Cases n=616 (40%) | 1B |

| Classification | OS 5Y 50% | OS 5Y 20% | OS 5Y 8% | |

| Median OS 4Y | Median OS 15M | Median OS 10M |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).