1. Introduction

Anaerobic digestion is a strategic technology for energy generation. Lignocellulosic biomass is of great interest as bioenergy feedstock due to its renewable, abundant, and inexpensive characteristics. The utilization of lignocellulose biomass for bioenergy purposes is a key element in the bioeconomy because it provides energy security and simultaneously promotes climate protection.

Sida hermaphrodita L. Rusby is one of the promising perennial energy crops, which has been sustainably cultivated in European trials with comparable harvested yields to other energy grasses. The studies of methane production from

Sida hermaphrodita biomass were performed only in laboratory-scale digesters, mainly as biomethane potential tests focusing on different biomass pretreatment methods [

1,

2,

3,

4].

The organic loading rate (OLR) is a key digester operating parameter that should be optimized to allow for adequate organic molecules’ passage into the microbial cell. Overloading the digester can result in lowering pH and inhibiting methanogens. The OLR has an essential role in changes in the diversity and abundance of microorganism’s communities, and therefore, can be considered as a functional tool that controls volatile fatty acids (VFAs) accumulation and biogas generation. The VFAs are important mid-products during anaerobic digestion, their concentration and profiling determine the efficiency of methane production. The main VFAs are acetic acid, butyric acid, and propionic acid. They present different effects on microorganisms’ populations; propionate has a higher inhibitory effect than butyrate [

5]. However, their influence on anaerobic digestion should be considered with the other process parameters (i.e., alkalinity).

Currently, several studies have investigated the composition and role of the microbial communities during the anaerobic digestion of lignocellulosic biomass [

6,

7]. First of all, understanding microbial community dynamics is crucial to optimizing anaerobic digestion and maximizing the OLR. Moreover, the studies of microbial populations, which are resistant to stress or are able to emerge after stressful conditions might provide basic information necessary for biotechnological innovations. Additionally, some microorganism groups might be used as indicators to process control, while others might be used for bioaugmentation to rebuild the community and bring optimal process conditions. Bacterial adaptation to changes in the OLR during digestion might improve process stability, either due to changes in community structure or changes in their physiology. The evaluation of microbial community during anaerobic digestion of S

ida hermaphrodita lignocellulosic biomass has never been presented.

The aim of the study was to evaluate the effectiveness of anaerobic digestion by linking the microbial composition and the process parameters under the different OLRs in a long-term semicontinuous digester. VFAs concentration and profiles together with the linked bacterial and methanogenic community structures are discussed in terms of stability and process yield.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Substrate and Inoculum

The substrate used in this study was

Sida hermaphrodita silage. The silage was prepared from perennial plantations harvested in spring in the second half of May. The plant material was ensiled without the addition of chemicals in bales weighing approximately 0.9 Mg fresh weight. The detailed characteristics of this silage are presented in Zieliński et al. [

8]. The silage was mixed with cattle manure and water at a weight ratio of 2:1:1 (

Table 1), resulting in moisture content of the substrate of about 90%. In the substrate, the content of organic matter from silage was 10 times higher than that from cattle manure. The inoculum was anaerobic sludge from an agricultural biogas plant, in which the substrate consists of mostly maize silage and pig manure.

2.2. Anaerobic Digestion Performance

The experiment was conducted on a semi-technical scale. The experiments were performed in a fully mixed reactor with an active volume of 300 L. The reactor has a tubular tank with an internal diameter of 1.2 m and a height of 0.4 m. The reactor was equipped with a low-speed mechanical agitator and systems for discharging/loading, temperature control, and biogas collection. The study was divided into three series, which differed in terms of the OLR of the reactor (

Table 1). In the first series (S1), the experiment lasted 100 days, enabling the hydraulic volume of the reactor to be exchanged two times, which eliminated the influence of the inoculum on the results. The second series (S2) lasted 87 days, during which the hydraulic volume of the reactor was also exchanged two times. The third series (S3) lasted 32 days, during which the hydraulic volume of the reactor was exchanged once; in this series, the reactor became overloaded, resulting in an accumulation of volatile fatty acids (VFAs; see Results for details), which indicated that it was pointless to continue research with this variant. Once a day, the reactor was fed with 6 kg, 9 kg, or 12 kg of the substrate (S1, S2, and S3, respectively), and the same amount of post-

fermentation sludge was simultaneously removed. Anaerobic digestion was performed in mesophilic conditions (38°C ± 2°C). The samples for the determination of process indicators were collected every second day.

Additionally, at the end of each series, to investigate the changes in process indicators, samples were taken from the reactor at intervals of at least two hours during the reactor operation cycle. The samples were analyzed as follows: biogas volume and quality, FOS/TAC ratio, total organic carbon (TOC), total nitrogen (TN), VFAs, total solids (TS), volatile solids (VS), pH.

2.3. Analytical Methods

The total organic carbon (TOC) in the filtrate was measured with (Shimadzu-L Japan analyzer). VFAs in the samples were subjected to qualitative and quantitative assessments using a gas chromatograph GC-FID (Brüker, 450-GC) [

9]. The temporary flow rate and the total production of biogas were measured with an Allborg mass flow analyzer. Before measuring the volume, the biogas was dried by cooling it below the dew point. The quality of biogas produced was measured with a gas chromatograph connected to a thermal conductivity detector (GC-TCD) (Agillent 7890 A). The TS and VS were measured using the gravimetric method. The content of volatile fatty acids (FOS value) and the buffer capacity (TAC value) were measured with a TitraLab AT1000 Series Titrator (Hatch) to calculate the FOS/TAC ratio. The pH was measured with a VWR 1000L pH meter.

2.4. Illumina MiSeq Sequencing

DNA isolation was done using a FastDNA® SPIN Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals). The purity and concentration of the isolated DNA were measured with a NanoDrop One spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). Metagenomic analysis was conducted based on the amplification and next sequencing of V3-V4 region, located in a range of 16S rRNA. Amplification and library preparation were participated by the specific primers (341F and 785 R). PCR reaction was prepared using Q5 Hotstart High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEBNext), under conditions consistent with the manufacturer's recommendations. The sequencing procedure was done with MiSeq Reagent Kit v2. The good quality DNA libraries were sequenced as 2 x250 base pair paired-end reads on the Illumina MiSeq platform. The demultiplex libraries were done directly after the sequencing procedure. During the quality control process, adapters and disturbing sequences were removed using filter and trim function, as a part of the DADA2 library within the R v4.2.0 Bioconductor [

10]. The next filtrating steps assumed calculation of error rate and elimination of chimeric reads using the remove BimeraDenovo R function. The taxonomy assignment was obtained using the DADA2 approach and the Silva 138 database [

11]. All filtrated sequences were tagged by alternative sequence variants (ASV) during the DADA2 pipeline. Clear reads were evaluated by bioinformatic pipeline, to obtain the operational taxonomic unit (OTU) clustering for each sample. The phyloseq [

12] R library was implemented to calculate diversity (Shannon and Simpson methods) and NMDS clustering metrics. The most abundant taxa (OTU classification) were visualized for phylum, family, and genus level using phyloseq and ggplot2 [

13] R libraries.

3. Results

3.1. Long-Term Anaerobic Digestion

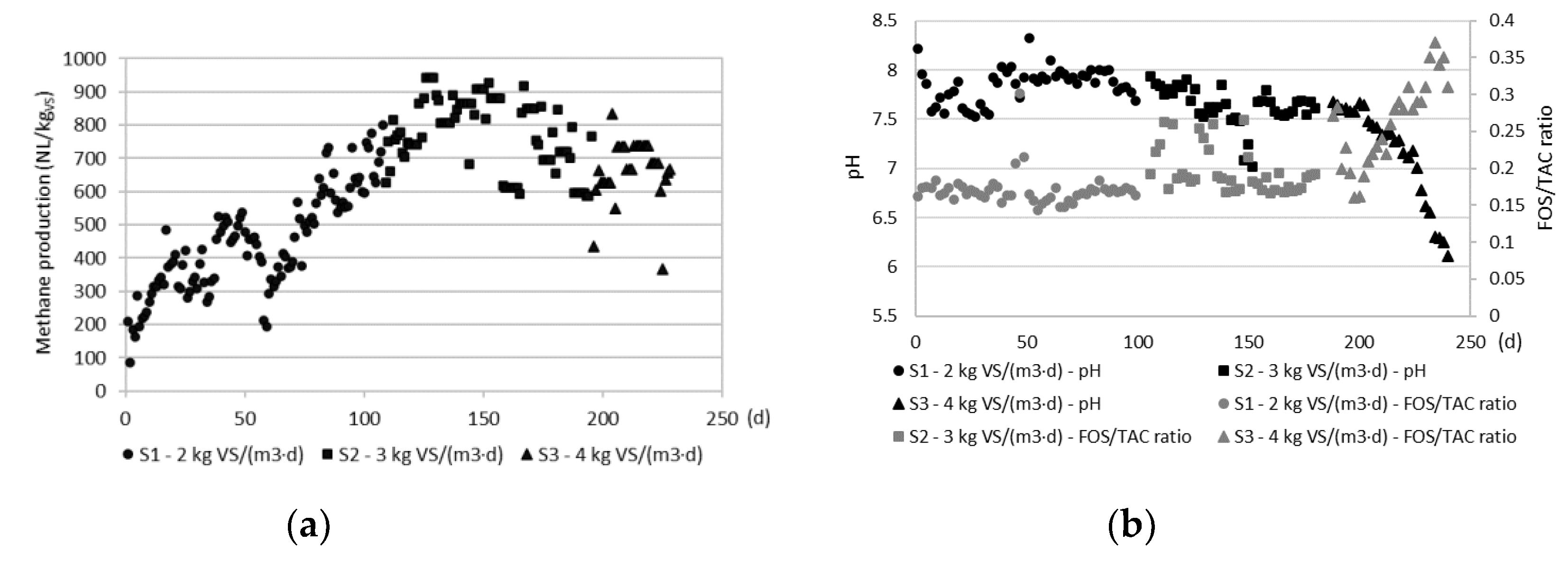

The OLR determined anaerobic digestion performance. In the S1, the average methane production was 446.3±153.7 NL/kgVS (

Figure 1A). During the S1, the methane production increased from 200 NL/kgVS to 750 NL/kgVS. In the S2, the average methane production was higher than in S1 and reached 773.4±107.8 NL/kgVS (

Figure 1A) The methane production increased until day 45 of S2 (150 day of the entire experiment), at which it reached 926.9 NL/kgVS. Next, until the end of the S2, the biogas production steadily decreased to 765.8 NL/kgVS. In the S3, average methane production was 666.7±91.2 NL/kgVS. The lowest value noted in this series was 365.9 NL/kgVS. The observations noted in the present study are similar to the literature. The methane production is influenced by the OLR; increasing the OLR finally leads to decreasing the methane yield. Similar values of the OLR to the present study were applied during co-digestion of alfalfa with manure [

14] and co-digestion of manure with grass [

15]. The authors observed inhibition of methane production at the OLR of 3 g VS/(L·d). The methane production during co-digestion of manure and grass decreased by 7% when the OLR was increased from 2 to 3 g VS/(L·d), and by 16-24% when the OLR was further increased to 4 g VS/(L·d).

The pH and FOS/TAC ratio were stable during the S1 and S2 and were on average 7.85±0.18 and 0.171±0.02 and 7.63±0.2 and 0.197±0.03, respectively (

Figure 1B). In the S3, these process parameters indicated inhibition of methane production. The pH decreased steadily from 7.68 to 6.11, the FOS/TAC ratio increased steadily from 0.272 to 0.35. Methanogens prefer growth at the pH of 6.5-7.2. Krishna and Kalamdhad (2014) reported that the highest methanogenic activity was noted at the pH of 7 [

16]. In the present study, the biomass was acidified by organic acids which resulted from accumulated VS in the digester. The substrate was characterized by 83.7±4.3% of organic matter in the TS. In the S1, the digestate was characterized by on average 65.8±3.9% of organic matter in the TS, which increased steadily during S1 from about 62% to 70%. In the S2, the digestate was characterized by 73.1±2.2% of organic matter in the TS, and it was higher than in the S1. In the S3, the content of organic matter in the TS further increased and reached 77.4±1.0%.This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3.2. Anaerobic Digestion During the Operation Cycle

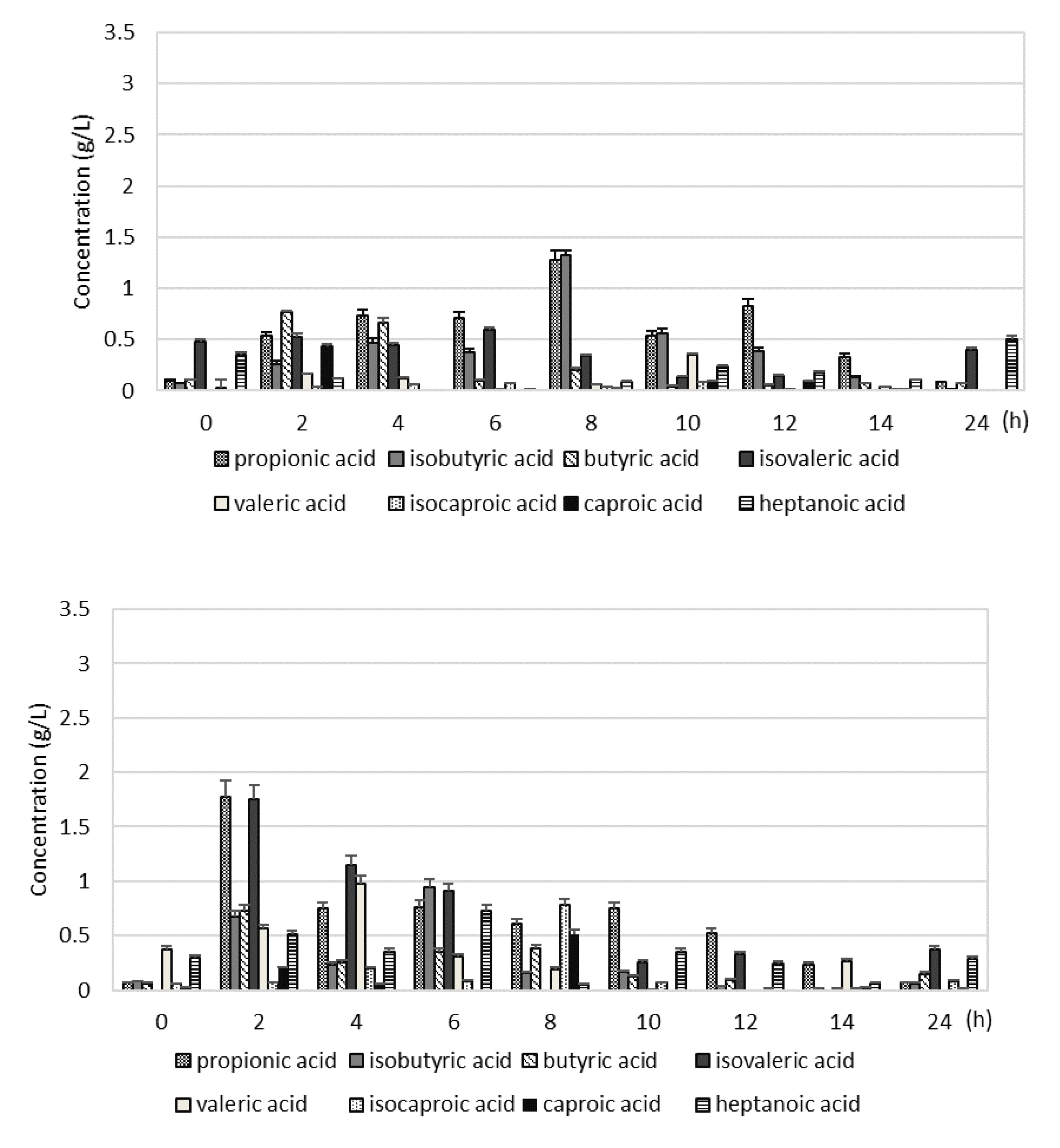

In the S1, the VFAs concentration during the 24 hours of digester operation at the beginning was 3.09±0.5 mM, after 8 hours of digester operation it reached a maximum (8.35±0.4 mM), and later decreased to 1.75±0.3 mM. The highest content among VFAs had acetic acid, which concentration at the beginning was 0.68±0.4 g/L, after 8 hours of digester operation it reached 2.62 ±0.3 g/L and at the end decreased to 0.46±0.1 g/L (

Figure S1). The concentration of propionic acid and isobutyric acid was also highest after 8 hours of digester operation (about 1.3 g/L) (

Figure 3A). The concentration of butyric acid was the highest after 2 and 4 hours of digester operation, and it reached 0.77±0.01 g/L and 0.66±0.05 g/L, respectively.

In the S2, the VFAs concentration at the beginning of digester operation was 1.97±0.8 mM, after 2 hours of digester operation it reached a maximum (21.25±2.4 mM), and then decreased to 1.79±0.5 mM. The highest concentration of VFAs was noted faster than in S1 and it was almost 3 times higher. After 2 hours of digester operation, the highest content among VFAs had acetic acid (8.63±0.6 g/L), propionic acid (1.78±0.14 g/L), and isovaleric acid (1.76±0.12 g/L) (Figures S1 and 2B).

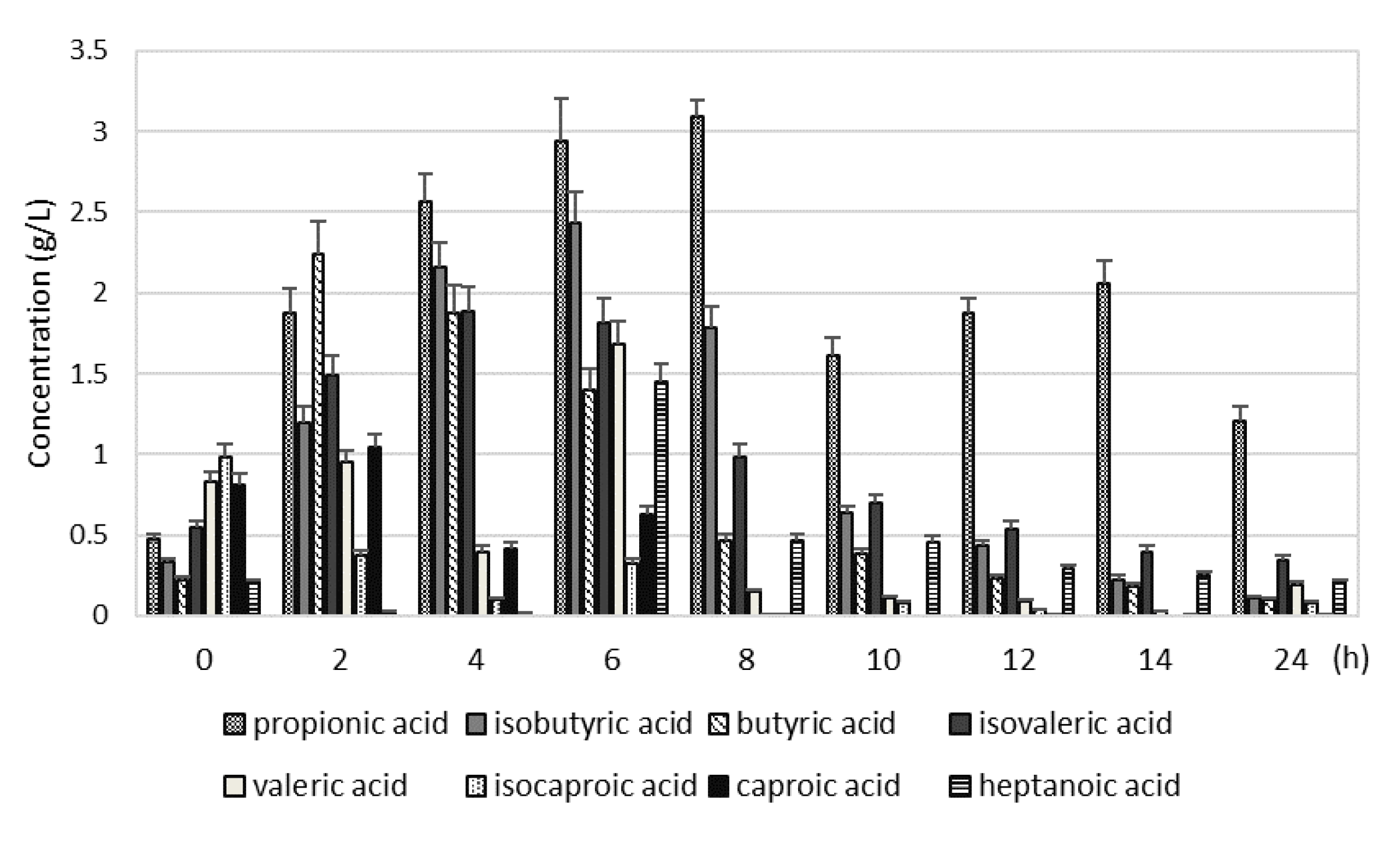

In the S3, the VFAs concentration at the beginning of digester operation was 9.11±1.9 mM, after 6 hours of digester operation it reached a maximum (34.97±3.8 mM). Among the VFAs the highest content had acetic acid (12.78±0.96 g/L), propionic acid (2.94±0.26 g/L), isobutyric acid (2.43±0.19 g/L), butyric acid (1.40±0.13 g/L) and isovaleric acid (1.82±0.15 g/L). At the end of the digester cycle, the highest concentration had acetic acid (4.95±0.5 g/L) and propionic acid (1.21±0.08 g/L). Ren et al. observed that the substrate conversion velocity of bacteria in the digester is as follows: acetic acid, then ethanol, butyric acid, and propionic acid [

17]. Therefore, propionic acid is accumulated easily and inhibits the production of methane. Wang et al. observed that inhibition of the growth and activity of methanogens was noted when the concentration of propionic acid was more than 900 mg/L [

18]. Marchaim and Krause pointed also on the propionic acid to acetic acid ratio, which indicates an impending failure when it is greater than 1:1.4 [

19]. In the present study, the measurements of the concentration of VFAs explain the observations of methane production. The accumulation of acetic acid and propionic acid in the S3 decreased the pH and increased the FOS/TAC ratio. The methane production has not been yet markedly inhibited (it was 14% lowered than in the S2), however, the experiment was stopped, because the above-mentioned process indicators changed, pointing process failure (the continuation would probably further inhibit methane production). Stable anaerobic digestion might be ensured by controlling the production of VFAs [

16,

20]. The concentration of VFAs higher than 2 g/L decreases microbial activity and the concentration of VFAs higher than 4 g/L inhibits fermentation. The VFAs can diffuse through hydrophilic layers of the bacterial cell wall, and then dissociate into anions, which cannot diffuse out of the cell. The accumulated anions cause an intracellular pH drop [

21].

In the S1, the TOC concentration increased from 3000 mg/L to 4500 mg/L in the first 2 hours of digester operation during S1 (

Figure S2A). Then, it decreased to about 3000 mg/L after 3 hours of digester operation and remained at this level until the end of the digester operation. The TN concentration slightly decreased from 3211±198 mg/L to 2966±121 mg/L during the 24 hours of the digester operation (

Figure S2B). The FOS/TAC ratio increased after 2 hours of digester operation from 0.182±0.01 to 0.244±0.02, then it decreased and reached 0.190±0.01 at the end of digester operation (

Figure S2C).

In the S2, the TOC concentration increased from 4403 mg/L to 6377 mg/L after 4 hours of digester operation during S2 (

Figure S2A). The TN concentration increased from 3132±198 mg/L to 4964±121 mg/L after 4 hours of digester operation, after the next 2 hours, it sharply decreased to 3437 mg/L, then it slowly decreased to 2670 mg/L (

Figure S2B). The FOS/TAC ratio increased after 2 hours of digester operation from 0.171±0.01 to 0.28±0.01, then it decreased and reached 0.200±0.01 at the end of digester operation (

Figure S2C).

In the S3, the TOC concentration increased from 5688 mg/L to 7331mg/L after 4 hours of digester operation (

Figure S2A). The TN concentration increased from 3600 to 5215 mg/L after 4 hours of digester operation (

Figure 2B). The FOS/TAC ratio increased after 4 hours of digester operation from 0.26±0.02 to 0.36±0.01 (

Figure S2C). The increase of the OLR resulted in increased TOC concentration in the digester, even at the beginning of the cycle. The substrate in the present study was lignocellulose biomass, and the increase of the TOC concentration after several hours after feeding was a result of biomass hydrolysis.

3.3. Microbial Community

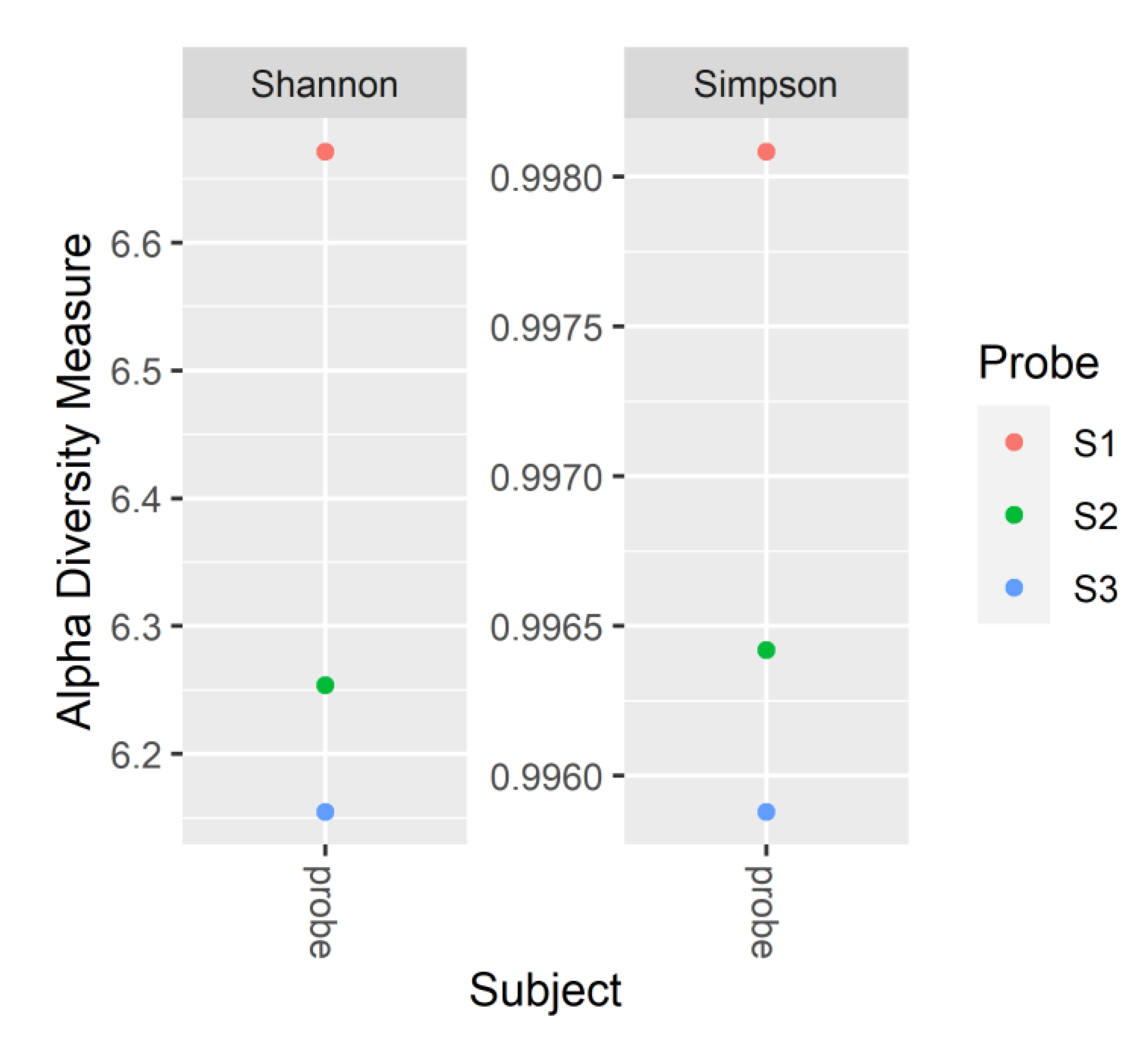

Microbial community evenness and richness are reflected by the Simpson and Shannon indices, respectively (

Figure 3). The highest indices were observed in the S1, indicating that the microbial community in the digester with the lowest OLR had the highest species diversity. However, increasing the OLR lead to a lowering of the diversity and domination of some specific species in the S3.

Figure 3.

The Shannon and Simpson indices in the samples collected at the end of the S1, S2 and S3

Figure 3.

The Shannon and Simpson indices in the samples collected at the end of the S1, S2 and S3

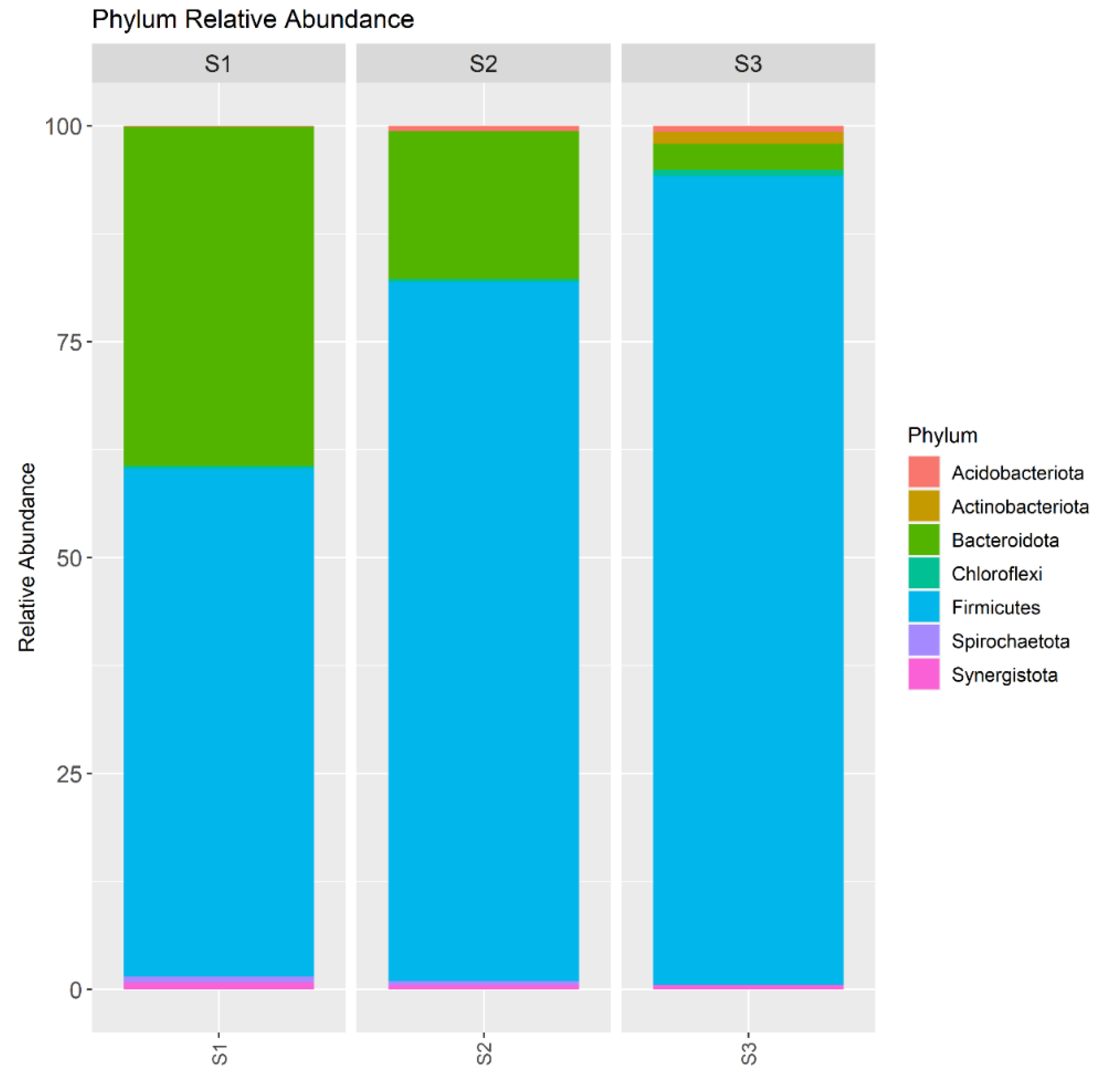

The microbial community was dominated by Firmicutes and Bacteroidota (

Figure 4). The abundance of Firmicutes increased with increasing the OLR in the digester, from 58.8% in the S1, 80.9% in the S2 to 93.6% in the S3. The number of bacteria in the phylum Acidobacteriota, Actinobacteriota, and Chloroflexi also increased with increasing the OLR in the digester. Opposite, Bacteroidota abundance decreased with increasing the OLR in the digester (39.3% in the S1, 17.1% in the S2, 3.0% in the S3). Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes are very often indicated as the most abundant phyla in mesophilic anaerobic digesters. Chen et al. pointed out the importance of interactions between Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes phyla in the stability of anaerobic digestion [

22]. The Authors suggested that the ratio between the abundance of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes could be a potential indicator for process performance. Firmicutes dominated the bacterial community during stable process performance while Bacteroidetes outcompeted Firmicutes in high OLR. These observations are different than in the present study. However, Atasoy et al. noted that phylum Firmicutes was associated with high VFAs production, which is consistent with the present study [

23]. In the S3, digester with the highest OLR, the methane production was inhibited and the VFAs were accumulated, Firmicutes abundance was 93.6%.

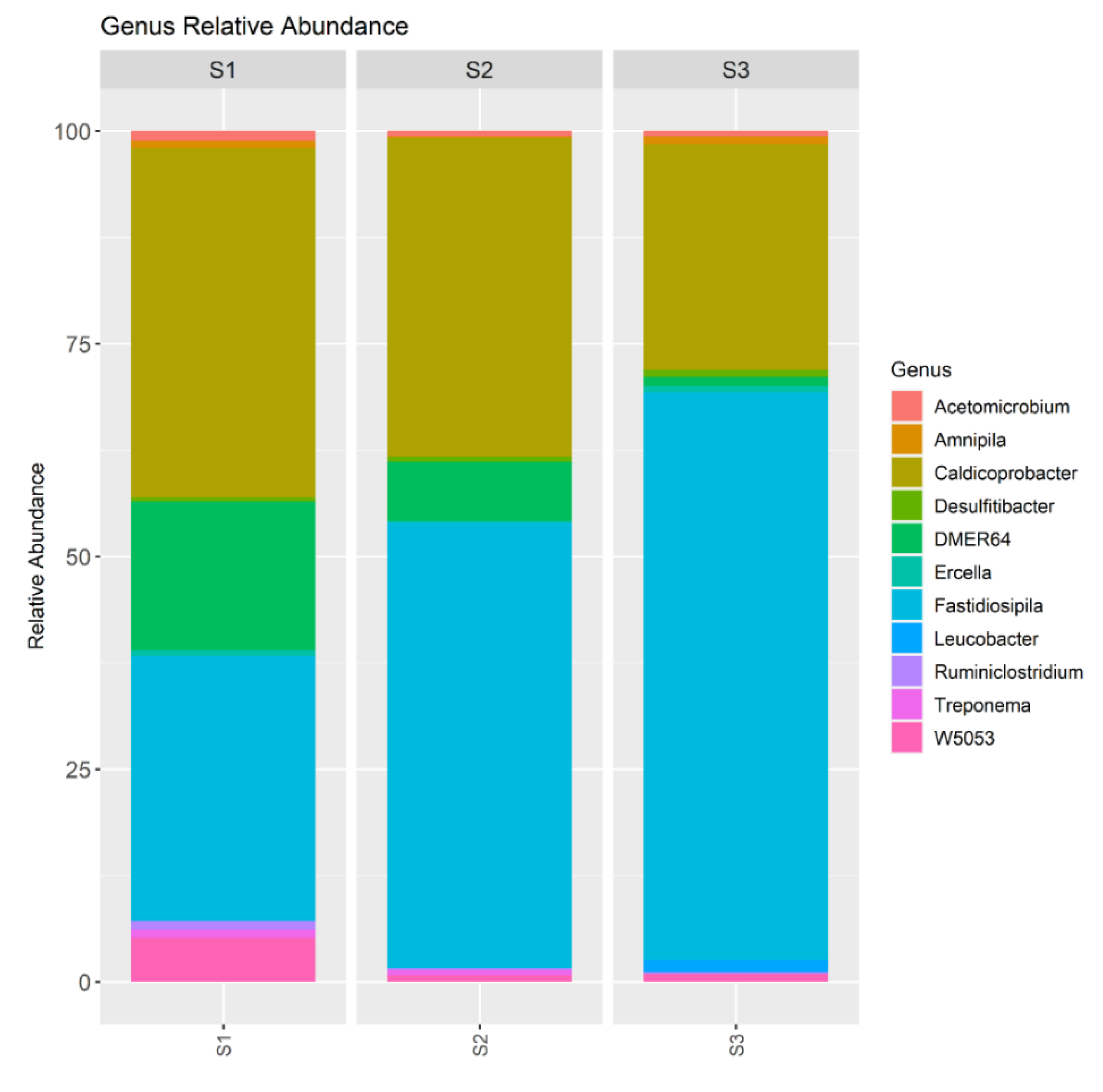

The main genera belonging to Firmicutes identified in the present study were

Caldicoprobacter and

Fastidiosipila (

Figure 5). The abundance of

Caldicoprobacter decreased from 41% in the S1, 37.5% in the S2 to 25.6% in the S3.

Caldicoprobacter is able to degrade hemicelluloses [

24]. Therefore, the high relative abundance of

Caldicoprobacter could promote the degradation of

Sida hermaphrodita, as it was in the case of corn straw noted by Guo et al. [

25]. However, their abundance was reduced by increasing the OLR, which suggested that

Caldicoprobacter is sensitive to lowering of pH and VFAs accumulation. Jiang et al. noted that the negative correlations of

Caldicoprobacter with acetic acid and butyric acid, also observed in the present study, might indicate that some species within this genus may function as syntrophic oxidizers of acetate and butyrate [

26].

The abundance of

Fastidiosipila increased with increasing the OLR from 31.1% in the S1, 52.5% in the S2 to 66.7% in the S3 (

Figure 5). Koo et al. have identified

Fastidiosipila and

Rikenellaceae RC9 as major bacterial genera in anaerobic co-digestion systems and these genera could also produce organic acids from protein and carbohydrate [

27].

Fastidiosipila has been identified as a major bacterial genus in mesophilic anaerobic digesters treating different types of substrates (i.e. waste food, waste landfill leachate and sewage sludge), that can produce organic acids such as butyric and acetic acids [

28]. In the present study, the abundance of

Fastidiosipila was the highest in the digester with acetic acid accumulation.

The phyla Bacteroidota was represented by genus DMER64 (

Figure 5) The abundance of DMER64 decreased (17.4% in the S1, 6.9% in the S2 to 1.0% in the S3) with increasing the OLR. DMER64 was considered as the essential genera for short chain fatty acids synthesis and specialized in producing acetic and propionic acid [

29]. However, Meng et al. indicated that DMER64 function during anaerobic digestion was keeping low hydrogen pressure by enhancing the interspecies H2 transfer, which probably was also its contribution in the present study [

30]. The authors also observed that the abundance of DMER64 strongly enhanced hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis conducted by

Methanosarcina. In the present study, Archaea abundance was reduced by increasing the OLR (3.8% in the S1, 1.0% in the S2, 0.8% in the S3). The main Archaea phylum was Halobacterota represented by

Methanosarcina. Thus, Meng et al. observations about DMER64 function and cooperation with

Methanosarcina in methane production were confirmed in the present study. It also indicates that methane was produced not only by the acetoclastic pathway but also by the hydrogenotrophic pathway. The other genus observed in the present study responsible for the hydrogen production, which abundance was reduced by the OLR (1.1% in the S1, 0.6% in the S2 and in the S3) was

Acetomicrobium belonging to Synergistota (

Figure 5). The cooperation between syntrophic hydrogen producers and methanogens is also extremely important in the anaerobic sludge community. Methanogens consume hydrogen, reduce the partial pressure of this gas, and stimulate the activity of acetogenic bacteria. This cooperation was disrupted by the increasing the OLR, which inhibited methane production.

4. Conclusions

In the optimized OLR, methane was produced during the acetoclastic and hydrogenotrophic pathway. Overloading, firstly influence on the pH and FOS/TAC ratio, inhibition of methane production had not been yet significant. Some Firmicutes genera were more sensitive (e.g., Caldicoprobacter) to overloading than others (e.g., Fastidiosipila).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Z. and P.R.; methodology, M.Z. and P.R.; software, Ł.P.; validation, M.Z. and P.R.; formal analysis, P.R.; investigation, M.Du., M.K. and P.R.; resources, M.Du.; data curation, P.R.; writing—original draft preparation, P.R.; writing—review and editing, M.Z., P.R., M.K., M.Du., M.De.; visualization, Ł.P. and P.R.; supervision, M.Z.; funding acquisition, M.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was carried out in the framework of the project under program BIOSTRATEG funded by the National Centre for Research and Development No. 1/270745/2/NCBR/2015 “Dietary, power, and economic potential of Sida hermaphrodita cultivation on fallow land”

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Borkowska, H.; Molas, R. Two Extremely Different Crops, Salix and Sida, as Sources of Renewable Bioenergy. Biomass Bioenergy 2012, 36, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinski, M.; Rusanowska, P.; Krzywik, A.; Dudek, M.; Nowicka, A.; Ebowski, M.D. Application of Hydrodynamic Cavitation for Improving Methane Fermentation of Sida Hermaphrodita Silage. Energies 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieliński, M.; Kisielewska, M.; Dudek, M.; Rusanowska, P.; Nowicka, A.; Krzemieniewski, M.; Kazimierowicz, J.; Dębowski, M. Comparison of Microwave Thermohydrolysis and Liquid Hot Water Pretreatment of Energy Crop Sida Hermaphrodita for Enhanced Methane Production. Biomass Bioenergy 2019, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisielewska, M.; Rusanowska, P.; Dudek, M.; Nowicka, A.; Krzywik, A.; Dębowski, M.; Kazimierowicz, J.; Zieliński, M. Evaluation of Ultrasound Pretreatment for Enhanced Anaerobic Digestion of Sida Hermaphrodita. , Bioenerg Res 2020, 13, 824–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barredo, M.S.; Evison, L.M. Effect of Propionate Toxicity on Methanogen-Enriched Sludge, Methanobrevibacter Smithii, and Methanospirillum Hungatii at Different PH Values. Appl Environ Microbiol 1991, 57, 1764–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faisal, S.; Thakur, N.; Jalalah, M.; Harraz, F.A.; Al-Assiri, M.S.; Saif, I.; Ali, G.; Zheng, Y.; Salama, E. Facilitated Lignocellulosic Biomass Digestibility in Anaerobic Digestion for Biomethane Production: Microbial Communities’ Structure and Interactions. Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology 2021, 96, 1798–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünyay, H.; Yılmaz, F.; Başar, İ.A.; Altınay Perendeci, N.; Çoban, I.; Şahinkaya, E. Effects of Organic Loading Rate on Methane Production from Switchgrass in Batch and Semi-Continuous Stirred Tank Reactor System. Biomass Bioenergy 2022, 156, 106306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieliński, M.; Rusanowska, P.; Zielińska, M.; Dudek, M.; Nowicka, A.; Purwin, C.; Fijałkowska, M.; Dębowski, M. Influence of Preparation of Sida Hermaphrodita Silages on Its Conversion to Methane. Renew Energy 2021, 163, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisielewska, M.; Dębowski, M; Zielińska, M; Zieliński, Z. Improvement of Biohydrogen Production Using a Reduced Pressure Fermentation. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng 2015, 38, 1925–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-Resolution Sample Inference from Illumina Amplicon Data. Nat Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Rg Peplies, J.; Glö Ckner, F.O. The SILVA Ribosomal RNA Gene Database Project: Improved Data Processing and Web-Based Tools. Nucleic Acids Res 2013, 41, D590–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mcmurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. Phyloseq: An R Package for Reproducible Interactive Analysis and Graphics of Microbiome Census Data. PLoS One 2013, 22, 8–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham H Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. . In; Springer-Verlag: New York, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nordberg, Å.; Jarvis, Å.; Stenberg, B.; Mathisen, B.; Svensson, B.H. Anaerobic Digestion of Alfalfa Silage with Recirculation of Process Liquid. Bioresour Technol 2007, 98, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehtomäki, A.; Huttunen, S.; Rintala, J.A. Laboratory Investigations on Co-Digestion of Energy Crops and Crop Residues with Cow Manure for Methane Production: Effect of Crop to Manure Ratio. Resour Conserv Recycl 2007, 51, 591–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, D.; Kalamdhad, A.S. Pre-Treatment and Anaerobic Digestion of Food Waste for High Rate Methane Production – A Review. J Environ Chem Eng 2014, 2, 1821–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, N.; Liu, M.; Wang, A.; Ding, J.; Li, H. [Organic Acids Conversion in Methanogenic-Phase Reactor of the Two-Phase Anaerobic Process. Huan Jing Ke Xue 2003, 24, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Meng, L. Effects of Volatile Fatty Acid Concentrations on Methane Yield and Methanogenic Bacteria. Biomass Bioenergy 2009, 33, 848–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchaim, U.; Krause, C. Propionic to Acetic Acid Ratios in Overloaded Anaerobic Digestion. Bioresour Technol 1993, 43, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Su, H.; Baeyens, J.; Tan, T. Reviewing the Anaerobic Digestion of Food Waste for Biogas Production. Renew Sust Energ Rev 2014, 38, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wambugu, C.W.; Rene, E.R.; Van de Vossenberg, J.; Dupont, C.; van Hullebusch, E.D. Biochar from Various Lignocellulosic Biomass Wastes as an Additive in Biogas Production from Food Waste. Waste Biorefinery: Integrating Biorefineries for Waste Valorisation 2020, 199–217. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Cheng, H.; Wyckoff, K.N.; He, Q. Linkages of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes Populations to Methanogenic Process Performance. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 2016, 43, 771–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atasoy, M.; Eyice, O.; Schnürer, A.; Cetecioglu, Z. Volatile Fatty Acids Production via Mixed Culture Fermentation: Revealing the Link between PH, Inoculum Type and Bacterial Composition. Bioresour Technol 2019, 292, 121889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widyasti, E.; Shikata, A.; Hashim, R.; Sulaiman, O.; Sudesh, K.; Wahjono, E.; Kosugi, A. Biodegradation of Fibrillated Oil Palm Trunk Fiber by a Novel Thermophilic, Anaerobic, Xylanolytic Bacterium Caldicoprobacter Sp. CL-2 Isolated from Compost. Enzyme Microb Technol 2018, 111, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.G.; Li, Q.; Wang, L.L.; Chen, Q.L.; Hu, H.W.; Cheng, D.J.; He, J.Z. Semi-Solid State Promotes the Methane Production during Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Chicken Manure with Corn Straw Comparison to Wet and High-Solid State. J Environ Manage 2022, 316, 115264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Dennehy, C.; Lawlor, P.G.; Hu, Z.; McCabe, M.; Cormican, P.; Zhan, X.; Gardiner, G.E. Exploring the Roles of and Interactions among Microbes in Dry Co-Digestion of Food Waste and Pig Manure Using High-Throughput 16S RRNA Gene Amplicon Sequencing. Biotechnol Biofuels 2019, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, T.; Yulisa, A.; Hwang, S. Microbial Community Structure in Full Scale Anaerobic Mono-and Co-Digesters Treating Food Waste and Animal Waste. Bioresour Technol 2019, 282, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moestedt, J.; Westerholm, M.; Isaksson, S.; Schnürer, A. Inoculum Source Determines Acetate and Lactate Production during Anaerobic Digestion of Sewage Sludge and Food Waste. Bioengineering 2019, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, P.; Kumar, M.; Kapoor, R.; Kumar, S.S.; Singh, L.; Vijay, V.; Vijay, V.K.; Kumar, V.; Thakur, I.S. Enhanced Biogas Production from Municipal Solid Waste via Co-Digestion with Sewage Sludge and Metabolic Pathway Analysis. Bioresour Technol 2020, 296, 122275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, X.; Cao, Q.; Sun, Y.; Huang, S.; Liu, X.; Li, D. 16S RRNA Genes- and Metagenome-Based Confirmation of Syntrophic Butyrate-Oxidizing Methanogenesis Enriched in High Butyrate Loading. Bioresour Technol 2022, 345, 126483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).