Introduction

According to the European Landscape Convention adopted by Poland in 2006 (Journal of Laws 2006 No. 14, item 98), the main purpose of which is to promote landscape activities, its protection, management and planning, and to organize European cooperation in this field. Article 6 of the Convention indicates special measures to protect European landscapes. Among these are listed raising awareness among the public, private organizations and public bodies of the value of landscapes and their role. It follows that the protection of landscapes can be realized, among other things, through the display and dissemination of the beauty, meanings, and impressions of landscape perception that define the values of native landscapes that we experience in our daily lives. One of the media creating such a message is art. However, questions arise as to whether artists deal with landscape in contemporary visual art works? If so, what dimensions of landscape and values are captured in their works?

These questions became the impetus for the May 2019 exhibition" Landscape of Life, Life of Landscape'", which gathered and presented the works of many artists, representatives of various fields, conveying their way of perceiving the value of the landscape along with the processes taking place in it.

Landscape vs. Image

Eugene Shumakovich's considerations undertaken in his works related to the phenomenology trend, specifically his perception of value (Shumakovich 2008) and landscape (Shumakovich 2016), inspired and solidified the choice of the exhibition's content. The term landscape, as the author points out, builds associations with the word image. A painting, graphic, scenic, moving, cinematic image in particular is considered in aesthetic terms. A painting has the artistic values of a work of art (value, harmony, proportion, etc.) and aesthetic value, giving the experience of the experience of perceiving this work - an object to be viewed savored, not used for the realization of other goods. The term value, quoted by the author after the Oxford dictionary, means that we recognize a feature or value of things when they acquire some meaning for us. The author also points out that value or valuing becomes important in decision-making processes (e.g., at the level of architecture, landscape, urban planning) affecting our environment. However, it should be remembered that at subsequent stages of functioning we also have the opposite process and it is the environment that shapes us/author.

An important role was played by the place where the works and artistic activities were exhibited, which was the park and garden establishment and the Wedel - Tuczynski castle in Tuczno, Walecki county, West Pomeranian voivodeship, located in the eastern part of the Walecki Lake District (

Figure 1). The castle is located on Castle Lake and the Runica River flows through the 19th-century landscape-style park. The character of the interiors of the medieval castle, the spirit of history, the picturesque location created opportunities, background and appropriate atmosphere, becoming the perfect setting for the exhibition, enhancing the power of artistic experiences and sensations.

Purpose

The purpose of this work is to analyze the works presented at the exhibition , "Landscape of Life, Life of Landscape" in terms of the transmitted values of the landscape, including spatial values, which showed the role and impact of artistic achievements on the viewer.

The essence was the artist as one who records landscape values, educating protects the landscape, and his work is a record of information and emotion related to its reception. The mission of the artist is to motivate reflection on the surrounding world and responsibility for the work presented, which becomes important, especially in the era of the encroachment of life into the virtual world. This phenomenon can undoubtedly result in a threat to the landscape and the destruction of its values.

Materials and Methods

The group of participants in the exhibition represented a variety of backgrounds. Both artists professionally engaged in visual arts, architects, for whom landscape painting is a complement to the design profession, and students of natural sciences and art colleges were invited to participate. Artists were asked to interpret the slogan Landscape of Life, Life of Landscape, leaving freedom in the choice of technique and language of expression.

Thirty-six artists participated in the exhibition (Appendix 1), nearly 80 works of painting, drawing, sculpture, photography, video, spatial and multimedia installations were presented.

The works delivered to the exhibition were subjected to formal and semantic layer analysis.

In the formal analysis, the physical form of the work was taken into account, in the case of painting works, the technique and materials were described, and in the case of a spatial installation, the materials from which they were made. The semantic analysis was supported by George Lakoff's concept of cognitive linguistics. It assumes that meaning is a representation, a picture of the world in the mind of the speaker (Kozłowska 2022). The concept of meaning derives from mental processes concerning the perception of the world.

The analysis ended with an attempt to define what landscape values were indicated and represented in the works. In the landscape interpretations of the works, reference was made to the values of the landscape, indicated by J. T. Królikowski, who deals with the study of the phenomenon of place (Królikowski 2006, 2010), also referring to the scientific theories of authors dealing with the topic of landscape and its perception (Yi Fu T. 1987). Pointing out the material and supramaterial values, we supported ourselves with methods, underlying which are physical features of the landscape, but also phenomenological methods, especially important in the interpretation and perception of our environment.

Recognition of Spatial Values of the Landscape

Perception, sensitivity, attention, knowledge, experience and imagination are elements that make up the complexity of the process of considering spatial values, as noted by Królikowski (2010). According to the author, the space we surround and perceive can be described by categories of physical, psychological and cultural features. These categories are accompanied by three types of space: physical, perceptual and cultural space. The determining factor in its perception and transformation is undoubtedly the values they present.

The subject of spatial values is very complex, among other things, due to their interpenetration, no less an attempt was made to systematize them, using the guidelines proposed by the author:

historic values, protected by laws, inherent in the substance of the object

Sacred values, the presence of which organizes and separates space, introduces hierarchy and testifies to a certain order. symbolic values, marking spaces rich and saturated with signs and images with an excess of meanings, proving the identity of the landscape

cognitive values, containing codes understandable to the recipient

Psychological values, testifying to the bond with the place, familiarity, identification and the desire to return, connecting with basic values like the meaning of life

Social and individual values, indicative of the use of space, but also of human relations

The historical values of the landscape as a backdrop to its history, the value of the past, but also the potential of today

Aesthetic values, individualized, dependent on perception skills, awareness, knowledge and experience

Artistic values, given by the creator and his style,

Landscape values, which are a repertoire of surrounding forms recorded at different times and in different states

Local, national, universal values, demonstrated by means of lifestyle and way of life, aspirations, spatial and cultural policies, manifested in forms that have a variety of reach

utility values, adaptation to the physical and mental needs of users, associated with harmony, order and comfort of staying in a given space,

Energy values, corresponding to civilization, city energy and related social Energy. It should be remembered that the synthesis of the above-mentioned spatial values is the concept of genius loci - the spirit of a place, which proves its authenticity, identity and uniqueness of the place.

The Transitional Values of the Presented Works

A total of 79 works were analyzed, of which three cases were treated as cycles and are counted as single works, and two cases of works with multiple elements, but intended by the author as a whole, which are also counted as single works of art.

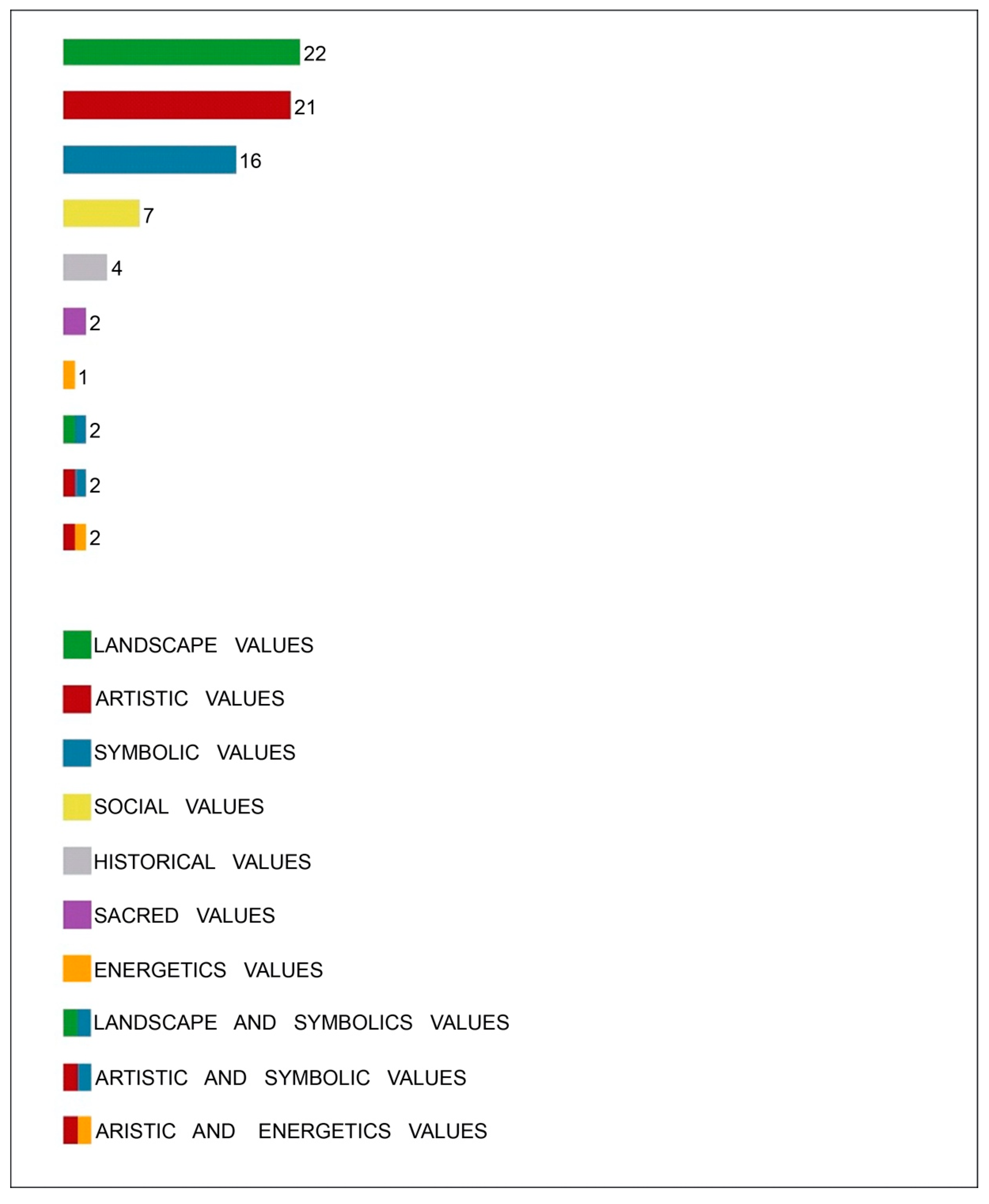

The analysis shows that among the collected works, the largest number represented landscape values, almost the same result came from works representing artistic values, while the least examples were represented by works that were assigned sacred and energetic values (

Figure 2.).

The following section presents selected works that were assigned to certain spatial values.

Artistic Values and Aesthetic Values

By virtue of the special nature of the materials possessed, it seems obvious to bring to the fore aesthetic and artistic values, which in principle can hardly be denied to a plastic work. Focusing on the form and the problem of the visuality of the work naturally corresponds to these values. It should be borne in mind that, for these reasons, an attempt to read certain paintings completely in terms of iconography may seem elusive, since these are works that present abstraction or are on the borderline of abstraction. Is it possible to relate this type of activity to the landscape, which is nevertheless a concrete reality? It seems that the most appropriate here would be the association with the character of cosmic genius loci (e.g., desert) (Królikowski 2010). Analyzing some of the proposals presented at the exhibition, we easily encounter those that formally correspond to this broad issue.

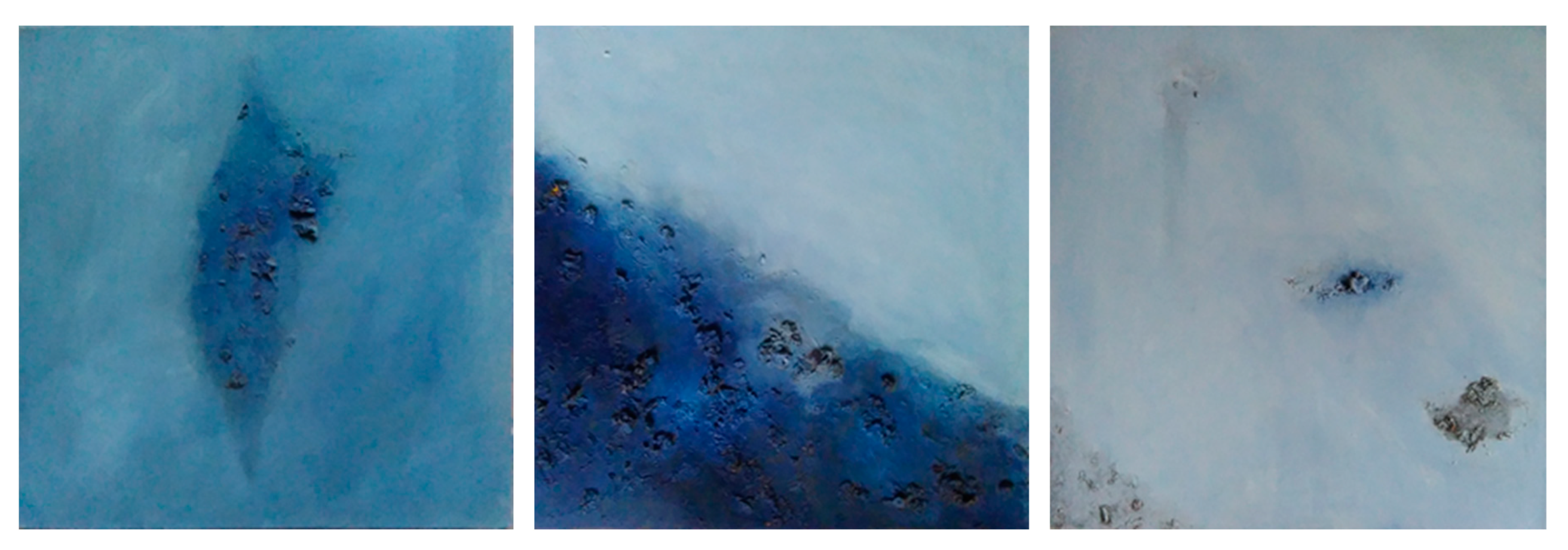

The cosmic nature undoubtedly evokes associations with a deserted landscape, just as we see in Marta Tarnawska's paintings that are painters' attempts to capture the immeasurable vastness of space. This impression is heightened by the bird's eye view shot, suggesting distant views of islands and coasts (

Figure 3.).

Another suggestion is Aleksandra Rykała's paintings, which refer to specific places (from the Island of Whligt series) or are a painterly interpretation of space (Boundless, Boundless). This attitude is best expressed in the words of the author herself: , "Each painting is a pause - my story about the personal feeling of space and touching the place, about the relationship between man and space [...]. A story elusive and enigmatic, saturated with light and fading into shadow" (

Figure 4.).

The emphasis on form with the simultaneous elusiveness of the registered landscape is also encountered in the paintings of Tomasz Nowak, in which the reinterpreted landscape, as the subject of the paintings, becomes, as it were, a pretext for painterly and compositional solutions. (

Figure 5.).

A similar approach, inspired by the landscape, which results in the expressiveness of the work, can be found in Marcin Sutryk (

Figure 6.)

The above examples show the approach closest to pure painting. The problem and at the same time the means of expression here include color, expression, gesture - thus aesthetic and artistic values, while the inspiration remains the landscape. It is interesting that the natural creative concentration on painterly values correlates here with an abstract view of space or its far-reaching interpretation. The feeling of emptiness caused by the absence of human presence is another feature that binds the above paintings together.

Similar formal solutions, focused on a painterly, abstract gesture, but inspired by music - and above all by the links between music and landscape (Chopin's works), will be encountered in a series of paintings by Jacek Damięcki, who, in contrast to the previous examples (oil painting), realizes his works in water-based technique on paper (

Figure 7.). This is a series of seven works.

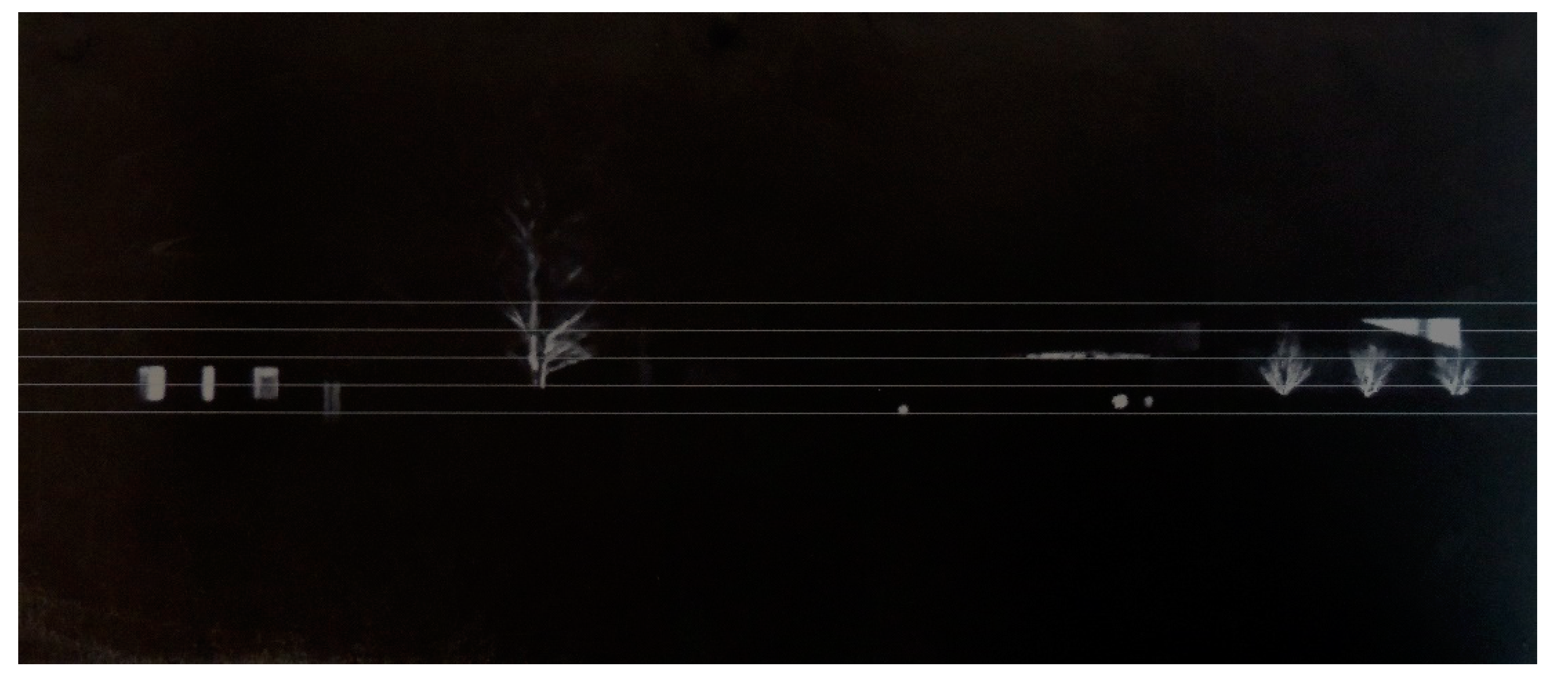

Musical - and therefore artistic and aesthetic - inspirations also appear in Izabela Dymitryszyn's work, where a stave, which organizes the space of the painting, is incorporated into the landscape, which is made unreal by the night shot (

Figure 8.). This action simultaneously places this work in symbolic values - the next specification, which we include below.

Symbolic Values

In the visual arts, it is impossible to assign a single meaning to symbolism. Depending on the currents, on the one hand it expresses the metaphysical content of the surrounding world, on the other hand it focuses on the inner experiences of man (Gradowska 1984). In the context of the exhibition's theme, it seems that this notion is best reflected in the thought of Henri Frederic Amiel: "All landscape is a state of the soul" (Bentkowska 1985), no less symbolic representations also include the human figure or its suggestion in the work, and such works are also included in the exhibition.

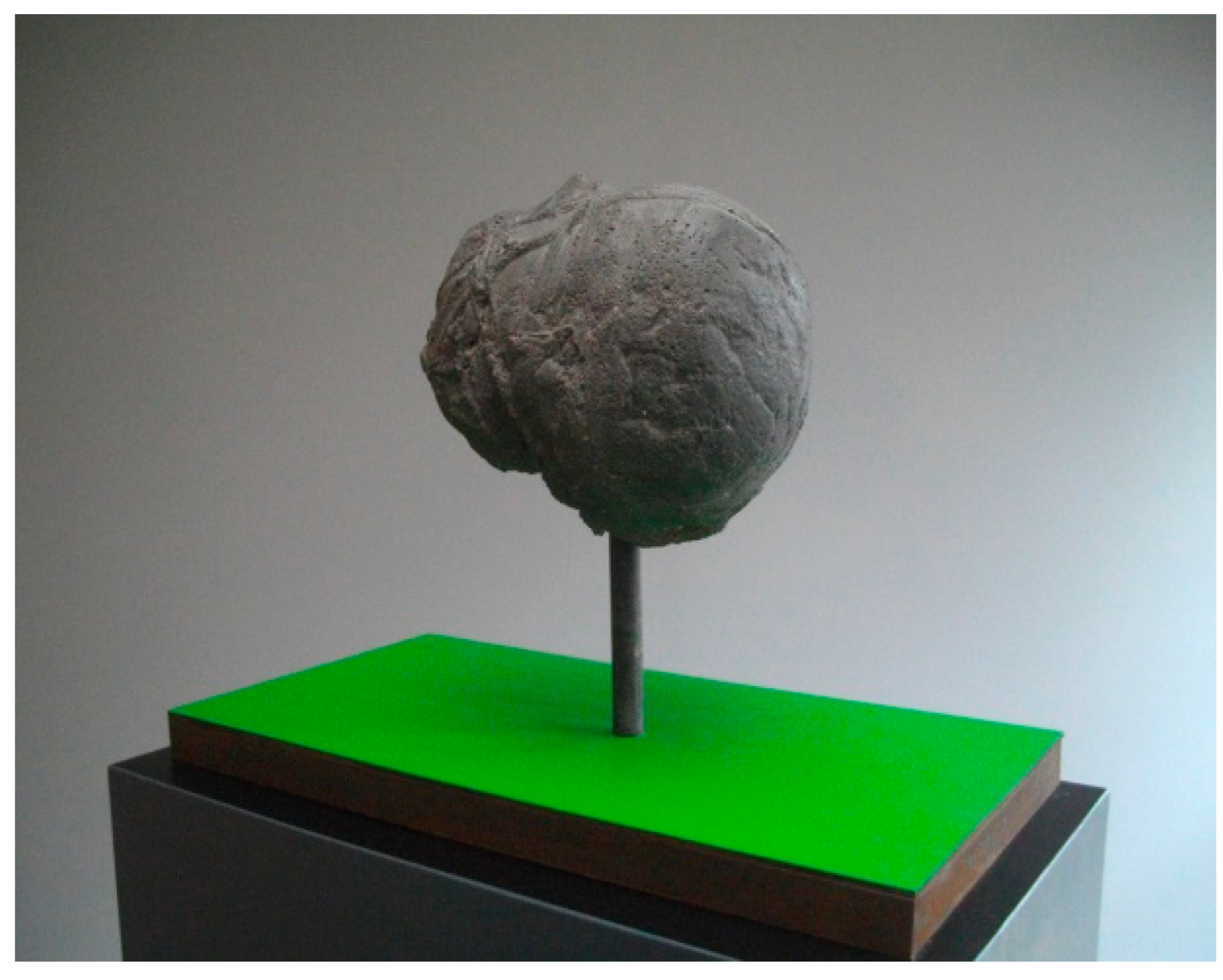

Symbolic values are presented by the sculpture by Michal Banaszek (

Figure 9.). The horizontally oriented, expressively modeled head evokes associations with exhumation, while the green-colored base indicates the material presence of the landscape. It is a symbolic representation of the inextricable link between human destiny and the earth, the end of every human's journey.

In the case of Janusz Ducki's triptych (

Figure 10.), the viewer's imagination is undoubtedly stimulated by the titles of the works. The formal convention of these works brings them closer to the paintings detailed in aesthetic and artistic values. Expression, gesture and color - we encounter these qualities here as well, but the symbolic meaning of the titles indicates a search for the universal meaning of a space composed of fundamental matter and elements.

The author's paintings were complemented by a spatial installation realized in the courtyard of the Castle (

Figure 11.). The action focuses on showing the contrast between nature, represented here by raw, massive trunks, and the ephemeral artistic intervention in the form of an attempt to merge them with colorful threads. The use of natural raw material also brings Duckie's work closer to landscape values.

Landscape Values

Landscape Values can essentially be applied to almost all the works collected in the exhibition. This seems a logical and at the same time natural response to its theme. We included in Landscape Values works that are characterized by the legibility of the surrounding space, relating directly to natural phenomena or depicting transformations that occur in the surrounding space.

A reference to landscape values is the realization of the team of Katarzyna Łowicka, Magdalena Kazulo (

Figure 12.). This is due to the nature of the work implemented directly in the park-like surroundings of the Tuczno Castle. In the installation Transformations, the artists intervene in the space, which also has symbolic references, while in the videos they focus on subtle changes in the environment. This perspective of vision is also reflected in the description of the work of the two authors: "During the realization of the art installation and the video recording, we were guided by the idea of drawing attention to the landscape, its existence and our presence in it, the beauty of each of its fragments, the beauty that we do not notice, because we are too absorbed in the pursuit of everyday busyness. For us, the landscape is a beauty that gives us tranquility and solace."

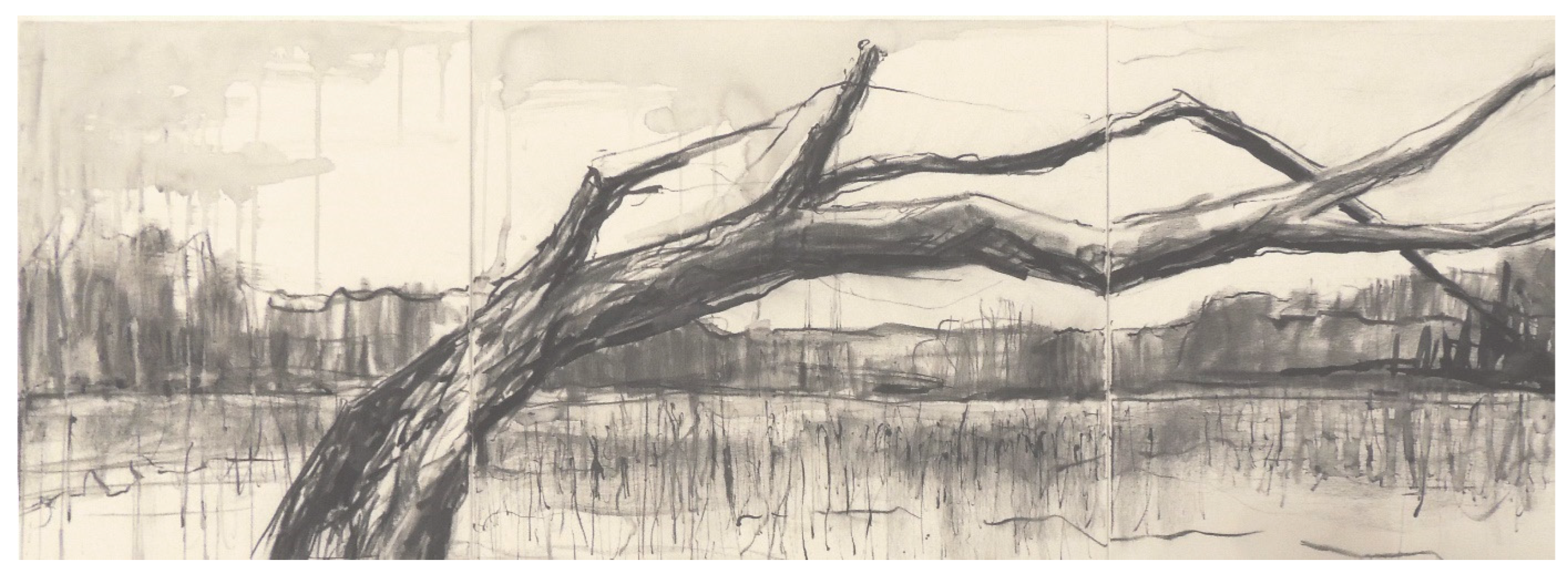

Another example is the work of Ewa Rykała (

Figure 13.), whose character can be placed between landscape representation and the search for means of individual expression. The clear, foregrounded depiction of a tree here corresponds with the spontaneously treated, conventional space.

A more conventional reference to landscape values are the pastels of Janusz Gajowiecki (

Figure 14.), who represented local artists. The motifs of his works indicate the different scale of the landscape; the artist focuses on relatively small spaces, and also studies small, ephemeral fragments of the landscape, such as flowers.

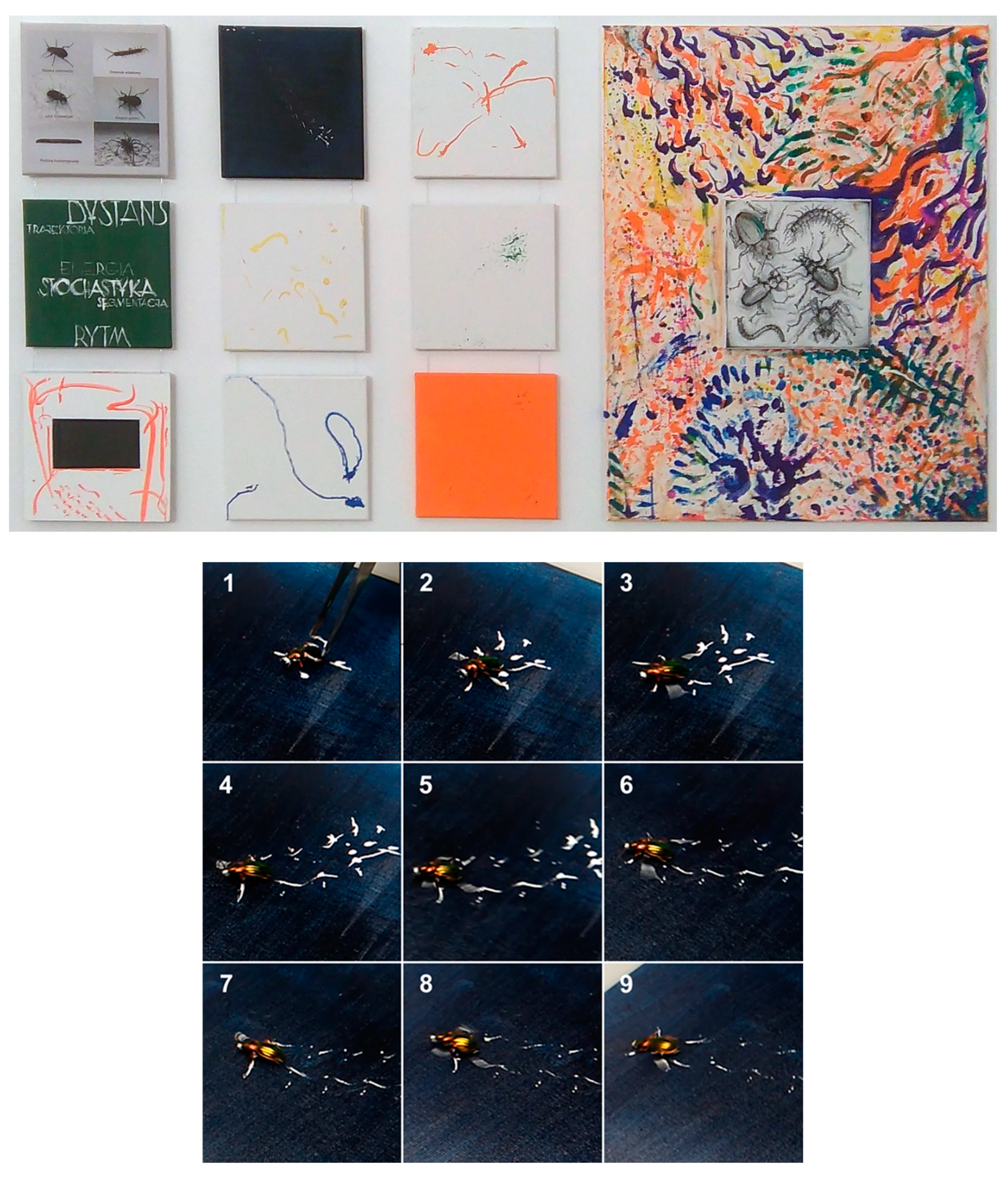

A completely different proposition is the work of the Department of Landscape Art's team, which focuses beyond the landscape theme on pushing the boundaries of the creation of an artwork (

Figure 15.). In this interdisciplinary (video recording and paintings) work, traces left by walking insects were recorded. This original point of view prompts the reflection that the landscape and its overall perception are also composed of its smallest fragments, and points to their unpredictable nature.

Social and Individual Values

Social values are obviously linked to human relations. The basic distinction of space here will be public, private and intimate space. Images assigned to this category are distinguished by the placement of staffage, so to speak, peeping at the various activities performed by anonymous characters.

A reporter's take, suburban and rural staffage showing the condition of a certain social group characterizes the images proposed by Agnieszka Czernik (

Figure 16.). Here we are dealing with a private and even in some respects intimate space with local color.

Sacred Values, Historic Values

Temples naturally fit into sacred values, but this is a much broader concept. This value will include not only buildings, but also sacred places found in the landscape and cemeteries. Sacred values, close to historic ones, are also closely related to historical values.

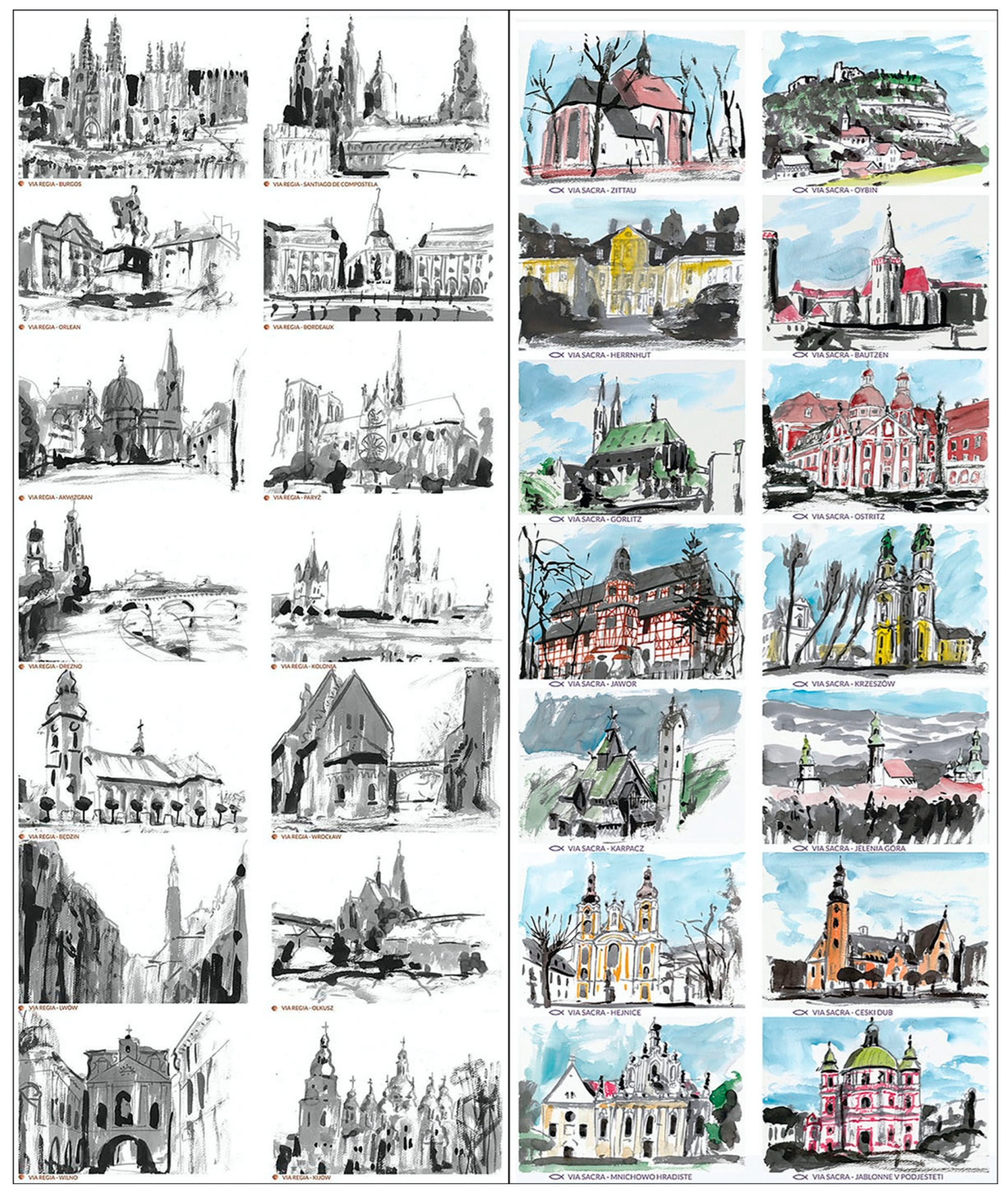

Jan Rylke's Via sacra (

Figure 17.) is associated with the visual documentation of a pilgrimage, the author's recording of the sacred buildings he encounters. This is essentially the only example in the exhibition of such a direct reference to sacred values.

Historical Values

Among the many values encountered in the landscape are historical values. When creating a work of art, an artist can also create such a value. Królikowski (2010) writes "The historical gaze should cover the entire space up to and including the present day, as well as the future, since history continues."

Katarzyna Krzykawska touches on historical and national themes in her work (

Figure 18.), placing agricultural tools in the landscape, bringing to mind a deserted battlefield. Here the artist addresses difficult and topical social and class relations: "In the series of works "Polish Melancholies" (2015-17), which I present at the exhibition in Tuczno, I polemicize with the 'polishness' of the native landscape and the ideological, historical and emotional charge enchanted in it." In her statement, the author also refers to the words of Gadamer (1993):,,[...] we cannot look at nature other than through the eyes of people experienced and raised in a certain culture [...]. What we have seen and what we have been taught through art shapes the perception and interpretation of the landscape."

Energy Values

The energy values of the landscape are inextricably linked to human civilization activities, of which the city is an emanation, among other things. They are also characterized by variability and permeation of forms (Królikowski 2010).

The association with energy values brings us to an installation consisting of a dozen openwork pyramids. Their universal form belongs to the roots of civilization. This work was a collaborative realization, made by the participants of the exhibition, so it allowed a certain amount of freedom in its arrangement. The title of the work "Aleatoric Structure of Space" prompts us to attribute musical themes to it as well, since the category of chance has made a particularly strong career in this field (Kmiecik 2012). Also in contemporary architecture, one can find some analogies with musical composition and structuralism (Rumież 2011).

Conclusions

An analysis of the artworks provided for the exhibition shows that landscape is a frequently taken theme and inspiration for contemporary creative activities in the field of visual arts. Landscape is captured in the works of contemporary artists in multiple ways. In the analyzed works of painting, sculpture, photography, film and spatial installations, a wide range of interpretations of the subject was noted, from the abstract approach aiming to articulate artistic, aesthetic and symbolic values to the realistic approach, highlighting sacred, historical, cognitive, social, individual, local, national, universal and, finally, landscape and natural values.

Thus, art can become an additional tool for disseminating knowledge about landscape values, and its display a means of educating and sensitizing the viewer to the issue of recognizing valuable landscapes and their protection.

On the basis of the isolation of individual values in a particular artwork, that is, captured and registered by the artist, so to speak, "worthy" of the subject of the artwork, we can assign a given value to a particular, real landscape with even greater accuracy. From our point of view, this feature may constitute an important surplus of a plastic work - important for its research potential.

The review of artistic expressions presented within the framework of the described exhibition, with the idea of cyclic continuation of this event, becomes at the same time a tool to track the current attitude of artists in the field of visual arts to the problem of landscape, its relationship with man and the condition of the surrounding space.

References

- Bentkowska A. (1985), Symbolika Drzewa. Dylematy związane z emblematyczna metodą interpretacji malarstwa. Rocznik Historii Sztuki, Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, Wrocław, Tom XV, ss. 305-315.

- Gadamer H. G.(1993), Aktualność piękna, cWydawnictwo Oficyna Naukowa, Warszawa.

- Gradowska A. (1984) Sztuka Młodej Polski, Wydawnictwa Artystyczne i Filmowe, Warszawa.

- Kmiecik M. (2012), Surrealizm a aleatoryzm. Przypadek Trois poèmes d’Henri Michaux Witolda Lutosławskiego, Teksty Drugie, Instytut Badań Literackich, Państwowa Akademia Nauk, Warszawa, 1-2, ss. 164-175.

- Kozłowska, A. Co to jest znaczenie? Współczesne koncepcje znaczenia i najważniejsze teorie semantyczne. Wykład UKSW. http://www.kozlowska.uksw.edu.pl/img/metodologia13.pdf (dostęp 28.01.2022).

- Królikowski, J.T. (2006), Interpretacje krajobrazów, Wydawnictwo SGGW, Warszawa.

- Królikowski J.T. (2010), Rozpoznanie i ocena wartości krajobrazu kulturowego, (w:) Ocena i wycena zasobów przyrodniczych (red.) Szyszko J., Rylke J., Jeżewski P., Dymitryszyn I., Wydawnictwo SGGW, Warszawa.

- Rumież A. (2011), Odwieczne melodie w architekturze : w poszukiwaniu nieprzemijalnych motywów. Czasopismo Techniczne. Architektura. Wydawnictwo Politechniki Krakowskiej, Kraków. R. 108, z. 4-A/2, ss. 361-366.

- Szumakowicz E. (2008) Uwagi o wartościach. Czasopismo techniczne 1-A (2008) Wydawnictwo Politechnika Krakowska. Kraków https://repozytorium.biblos.pk.edu.pl/redo/resources/33387/file/suwFiles/Szumakowicz.E - dostęp 27.12.2021).

- Szumakowicz E. (2016) Fenomenologia krajobrazu. Kwartalnik Filozoficzny Tom XLIV/2016/z.2. Wydawnictwo Politechnika Krakowska Kraków.

- Yi Fu T. (1987), Przestrzeń i miejsce, PIW, Warszawa.

Figure 1.

Poster of the exhibition held in the Tuczno Castle. J. Ducki, I. Dymitryszyn,students of the Faculty of Landscape Architecture at SGGW.

Figure 1.

Poster of the exhibition held in the Tuczno Castle. J. Ducki, I. Dymitryszyn,students of the Faculty of Landscape Architecture at SGGW.

Figure 2.

Summary of the works collected at the exhibition in terms of their assignment to particular spatial values (own elaboration).

Figure 2.

Summary of the works collected at the exhibition in terms of their assignment to particular spatial values (own elaboration).

Figure 3.

Marta Tarnawska, Untitled, series of three paintings, oil, canvas, dimensions of each: 60 cm x 60 cm, 2019.

Figure 3.

Marta Tarnawska, Untitled, series of three paintings, oil, canvas, dimensions of each: 60 cm x 60 cm, 2019.

Figure 4.

Aleksandra Rykała, Boundless, Boundless, Island of Whight, series of three paintings, oil on canvas and acrylic on canvas, dimensions of each: 120 cm x 160 cm, 2016.

Figure 4.

Aleksandra Rykała, Boundless, Boundless, Island of Whight, series of three paintings, oil on canvas and acrylic on canvas, dimensions of each: 120 cm x 160 cm, 2016.

Figure 5.

Tomasz Nowak, View, oil on canvas 81 cm x 130 cm, 2006. (Photo by the author).

Figure 5.

Tomasz Nowak, View, oil on canvas 81 cm x 130 cm, 2006. (Photo by the author).

Figure 6.

Marcin Sutryk, Untitled, oil on canvas 150 cm x100 cm, 2018. (Photo by the author).

Figure 6.

Marcin Sutryk, Untitled, oil on canvas 150 cm x100 cm, 2018. (Photo by the author).

Figure 7.

Jacek Damięcki, II Etape Etude no 76 China, from a series of paintings inspired by the music of F. Chopin, watercolor, 4 works 100 cm x 70 cm, 3 works 50 x 70 cm, 2015.

Figure 7.

Jacek Damięcki, II Etape Etude no 76 China, from a series of paintings inspired by the music of F. Chopin, watercolor, 4 works 100 cm x 70 cm, 3 works 50 x 70 cm, 2015.

Figure 8.

Izabela Dymitryszyn, Music of Architecture 1, digital photography, offset print on paper, 40 cm x 90 cm, 2019.

Figure 8.

Izabela Dymitryszyn, Music of Architecture 1, digital photography, offset print on paper, 40 cm x 90 cm, 2019.

Figure 9.

Michal Banaszek, Head, concrete, steel, height 39 cm, 2017.

Figure 9.

Michal Banaszek, Head, concrete, steel, height 39 cm, 2017.

Figure 10.

Janusz Ducki, Triptych: Air, 96 cm x 117 cm, oil on panel, Water, 96 cm x 117 cm, oil on panel. Earth, 96 x 117 cm, oil on panel.

Figure 10.

Janusz Ducki, Triptych: Air, 96 cm x 117 cm, oil on panel, Water, 96 cm x 117 cm, oil on panel. Earth, 96 x 117 cm, oil on panel.

Figure 11.

Janusz Ducki, Power in softness, wood, combed wool. 2019.

Figure 11.

Janusz Ducki, Power in softness, wood, combed wool. 2019.

Figure 12.

Group in Squad: Katarzyna Lowicka, Magdalena Kazulo, Transformations, spatial installation, PV film, wood, 2019.

Figure 12.

Group in Squad: Katarzyna Lowicka, Magdalena Kazulo, Transformations, spatial installation, PV film, wood, 2019.

Figure 13.

Ewa A. Rykała, Untitled, acrylic and charcoal on canvas, 150 cm x 50 cm, 2019.

Figure 13.

Ewa A. Rykała, Untitled, acrylic and charcoal on canvas, 150 cm x 50 cm, 2019.

Figure 14.

Janusz Gajowiecki, Bridge over Castle Lake. Tuczno, Castle Lake. Tuczno, Blue iris, dry pastel, works format: 68 cm x 91 cm.

Figure 14.

Janusz Gajowiecki, Bridge over Castle Lake. Tuczno, Castle Lake. Tuczno, Blue iris, dry pastel, works format: 68 cm x 91 cm.

Figure 15.

Ewa Kosiacka - Beck, Agata Jojczyk, Axel Schwerk, series Traces, canvas (8 works), acrylic, ink, video recording, 2019.

Figure 15.

Ewa Kosiacka - Beck, Agata Jojczyk, Axel Schwerk, series Traces, canvas (8 works), acrylic, ink, video recording, 2019.

Figure 16.

Agnieszka Czernik, Franciszka Kleeberga in Siedlce google street view, acrylic on canvas, Dąbrowica Duża 53 from a balcony, acrylic on canvas. Dimensions of both works 50 cm x 70 cm, 2019.

Figure 16.

Agnieszka Czernik, Franciszka Kleeberga in Siedlce google street view, acrylic on canvas, Dąbrowica Duża 53 from a balcony, acrylic on canvas. Dimensions of both works 50 cm x 70 cm, 2019.

Figure 17.

Jan Rylke, Via Regia, Via Sacra, watercolor, ink (cycle prints, two boards), dimensions of each board 200 cm x 85 cm, 2004.

Figure 17.

Jan Rylke, Via Regia, Via Sacra, watercolor, ink (cycle prints, two boards), dimensions of each board 200 cm x 85 cm, 2004.

Figure 18.

Katarzyna Krzykawska, Borderline Landscape, video, duration: 5:02 min, 2016. (Photo by the author).

Figure 18.

Katarzyna Krzykawska, Borderline Landscape, video, duration: 5:02 min, 2016. (Photo by the author).

Figure 19.

Jeremi T Królikowski (originator) with his team, Aleatoric Space Structure Installation. Wooden slats 1 cm x 1 cm x 100 cm, 2019. (photo: Slawomir T. Trzepacz).

Figure 19.

Jeremi T Królikowski (originator) with his team, Aleatoric Space Structure Installation. Wooden slats 1 cm x 1 cm x 100 cm, 2019. (photo: Slawomir T. Trzepacz).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).