Submitted:

16 January 2025

Posted:

16 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

- What is the evidence of the reported effects on cardiovascular health outcomes associated with traditional dance and games in diverse LMICs?

- b. What are quantitative and qualitative facets of these traditional dance and games across different demographic groups, settings and any specific population groups that show greater benefits from one of the interventions over the other and what are recommendations for future studies?

| Abbreviation | Description | Question components |

| P | Population | Children, Adolescents, Youth, Adults, Older adults |

| I | Concept | Association between traditional dance improve cardiovascular health |

| C | Context | Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) |

| O | Outcomes | Cardiorespiratory fitness, body composition, blood biomarkers, physical function |

| S | Study designs | RCT or Non-RCT (i.e., Cross-sectional/Observational) |

3. Results

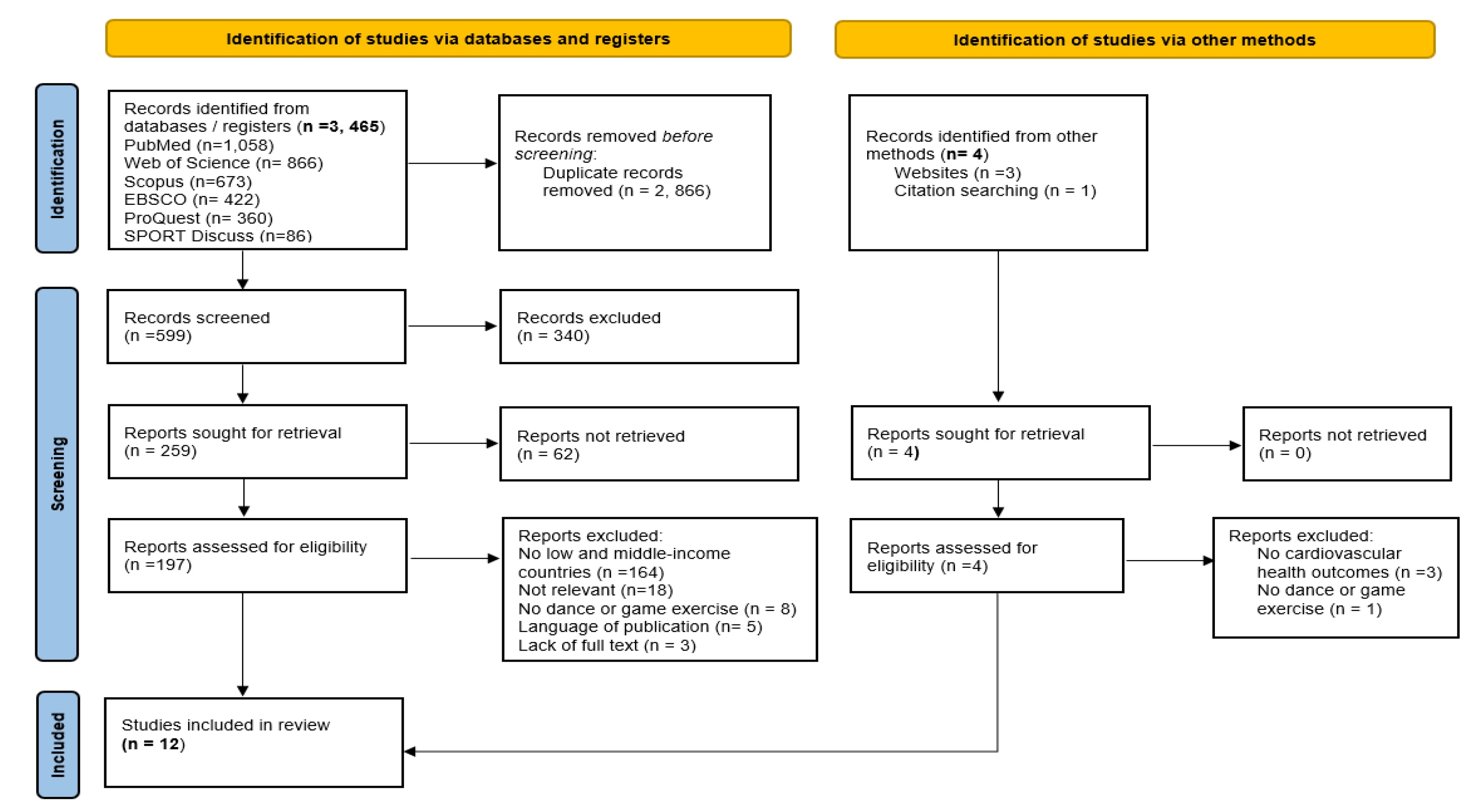

3.1. Literature Search and Included Studies

3.2. Characteristics of Search and Included Studies

3.3. Characteristics of participants

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Practice

4.2. Implications for Policy

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

- Future Research

Author Contributions

References

- WHO website World Health Organization. Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013–2020 Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. https://www.who.int/nmh/events/ncd_action_plan/en (assessed 10 September 2024).

- World Heart Report 2023: Confronting the World’s Number One Killer. Geneva, Switzerland. World Heart Federation. 2023. Available online: https://world-heart-federation.org/news/deaths-from-cardiovascular-disease-surged-60-globally-over-the-last-30-years-report/ (accessed 10 September 2024).

- Fong Yan A, Cobley S, Chan C, Pappas E, Nicholson LL, Ward RE, Murdoch RE, Gu Y, Trevor BL, Vassallo AJ, Wewege MA, Hiller CE. The Effectiveness of Dance Interventions on Physical Health Outcomes Compared to Other Forms of Physical Activity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2018,48(4):933-951. [CrossRef]

- World Health Statistics 2024: Monitoring Health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals Available online 2024. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/376869/9789240094703-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed 10 September 2024).

- Tan MP. Healthcare for older people in lower- and middle-income countries. Age and Ageing. 2022, 51(4), afac016. [CrossRef]

- Shaw, B.S., Sandercock, GRH, Van Biljon, A. & Shaw, I. (2022). Moving beyond Cardio: The Value of Resistance Exercise Training for Cardiovascular Disease 2022. In: Gaze, D.C. (Ed.). Cardiovascular Disease. Intech Open Publishers; London, United Kingdom.

- Tulu, S.N.; Al Salmi, N.; Jones, J. Understanding cardiovascular disease in day-to-day living for African people: A qualitative meta-synthesis. BMC Public Health. 2021, 21, 745.

- Mutowo, M.P., Owen, A.J., Billah, B. et al. Burden attributable to Cardiometabolic Diseases in Zimbabwe: a retrospective cross-sectional study of national mortality data. BMC Public Health. 2015,15, 1213. [CrossRef]

- Yuyun, M. F., Sliwa, K., Kengne, A. P., Mocumbi, A. O., & Bukhman, G. Cardiovascular Diseases in Sub-Saharan Africa Compared to High-Income Countries: An Epidemiological Perspective. Global heart. 2020,15(1), 15. [CrossRef]

- Kämpfen, F., Wijemunige, N. & Evangelista, B. Aging, non-communicable diseases, and old-age disability in low- and middle-income countries: a challenge for global health. Int J Public Health. 2018, 63, 1011–1012. [CrossRef]

- Shandu, M.M, Mathunjwa, M.L.; Shaw, B.S.; Shaw, I. The Need for Indigenous Games to Combat Noncommunicable Diseases in South Africa: A Narrative Review. J Phys Med Rehabil Disabil. 2024,10: 089.

- Lim, S. E. R., Cox, N. J., Tan, Q. Y., Ibrahim, K., & Roberts, H. C. Volunteer-led physical activity interventions to improve health outcomes for community-dwelling older people: a systematic review. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research. 2021, 33(4), 843–853. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues-Krause, J., Farinha, J. B., Ramis, T. R., Macedo, R. C. O., Boeno, F. P., Dos Santos, G. C., Vargas, J., Jr, Lopez, P., Grazioli, R., Costa, R. R., Pinto, R. S., Krause, M., & Reischak-Oliveira, A. Effects of dancing compared to walking on cardiovascular risk and functional capacity of older women: A randomized controlled trial. Experimental Gerontology, 2018,114, 67–77. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global status report on physical activity 2022: country profiles https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240064119 (assessed on 27 October 2024.

- Godward S. Adult Public Health and Non-Communicable Diseases. In: Watson K, Yates J, Gillam S, eds. Essential Public Health: Theory and Practice. Cambridge University Press. 2023, 231-248.

- Bogopa, D, L. The importance of indigenous games: The selected cases of indigenous games in South Africa. Indilinga: African Journal of Indigenous Knowledge Systems. 2012, 11(2), 245-256. [CrossRef]

- Burnett C. Indigenous games of South African children: A rationale for categorization and taxonomy. South African Journal for Research in Sport, Physical Education and Recreation. 2006, 28(2): 1 -13.ISSN: 0379-9069.

- Ismoyo, I, Nasrulloh, A.., Ardiyanto Hermawan, H.., & Ihsan, F. Health benefits of traditional games - a systematic review. Retos. 2024, 59, 843–856.

- Malik, A.A; Jawis, M. N.; Hashim, H. A. Exercise intensity and enjoyment response of selected traditional games in children. Malaysian Journal of Movement, Health & Exercise. 2021;10(2), 93-98. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues-Krause, J., Krause, M., & Reischak-Oliveira, A. Dancing for Healthy Aging: Functional and Metabolic Perspectives. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine, 2019,25(1), 44–63.

- Zhang Y, Guo Z, Liu Y, Zhou Y, Jing L Is dancing an effective intervention for fat loss? A systematic review and meta-analysis of dance interventions on body composition. PLoS ONE. 2024, 19(1), e0296089.

- Rodrigues-Krause, J., Farinha, J. B., Krause, M., & Reischak-Oliveira, Á. Effects of dance interventions on cardiovascular risk with ageing: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2016,29, 16–28. [CrossRef]

- Tao, D., Gao, Y., Cole, A., Baker, J. S., Gu, Y., Supriya, R., Tong, T. K., Hu, Q., & Awan-Scully, R. The Physiological and Psychological Benefits of Dance and its Effects on Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in Physiology, 2022, 13, 925958. [CrossRef]

- Daca T, Prista A, Farinatti P, Maia Pacheco M, Drews R, Manyanga T, Damasceno A, Tani G. Biopsychosocial Effects of a Conventional Exercise Program and Culturally Relevant Activities in Older Women from Mozambique. J Phys Act Health. 2023, 21(1),51-58. [CrossRef]

- Townsend, N., Wilson, L., Bhatnagar, P., Wickramasinghe, K., Rayner, M., & Nichols, M. Cardiovascular disease in Europe: epidemiological update 2016. European Heart Journal. 2016, 37(42), 3232–3245. [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., Lewin, S., … Straus, S. E. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2018, 169(7), 467–473. [CrossRef]

- Reviewers-Manual_Methodology-for-JBI-Scoping-Reviews_2015_v2.pdf n.d.

- Fantom, Neil James and Serajuddin, Umar, The World Bank's Classification of Countries by Income. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 7528, 2016.Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2741183 (assessed 10 September 2024.

- Duarte, C.C., Santos-Silva, P.R., Paludo, A.C., Grecco, M.V., & Greve, J. M. D. Effect of 12-week rehearsal on cardiorespiratory fitness and body composition in Brazilian samba dancers. einstein (Sao Paulo). 2023, 21,eAO0321. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Liu, L., Chen, Q., Chen, Y., & Lam, W. K. Pilot testing of a simplified dance intervention for cardiorespiratory fitness and blood lipids in obese older women. Geriatric Nursing (New York, N.Y.). 2023,51, 40–48. [CrossRef]

- Ajala, R. B., Adedokun, K. I., Adedeji, O. C. and Ojo, O. R. Aerobic Dance Exercise and its Effect on Cardiorespiratory Variables and Body Composition of Obese Youth and Adolescents in College of Education Ila- Orangun, Nigeria. The International Journal of Humanities & Social Studies. 2020, 8(8)22-28. ISSN 2321 – 9203.

- Gebretensay, M.; Mondal, S.; Mathivanan, D.; Abdulkader, M.; Gebru, G. Effect of traditional dances on physiological variables among high school students in Ethiopia. 2018, 3(2), 1119-1123. ISSN:2456-0057.

- Nxumalo, S.A., Semple, S.J. & Longhurst, G.K. Effects of Zulu stick fighting on health-related physical fitness of prepubescent Zulu males. African Journal for Physical, Health Education, Recreation and Dance. 2015, 21(1:1), 32-45.

- Kin Isler, A., Koşar, S. N., & Korkusuz, F. Effects of step aerobics and aerobic dancing on serum lipids and lipoproteins. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness. 2001, 41(3), 380–385.

- Manihuruk, F., Nasrulloh, A., Nugroho, S., Sumaryanto, Guntur, Prasetyo, Y., Sulistiyono, Sumaryanti, & Galeko, J.P.The effect of traditional games of North Sumatra on increasing agility, balance, and endurance of badminton athletes. Fizjoterapia Polska. 2024, 24(3), 222-231.

- Yulia, C., Khomsan, A., Sukandar, D., & Riyadi, H. Effect of nutrition education and traditional game-based physical activity interventions, on lipid profile improvement in overweight and obese children in West Java Indonesia. Nutrition Research and Practice, 2021,15(4), 479–491. [CrossRef]

- Rauber, S. B., Boullosa, D. A., Carvalho, F. O., de Moraes, J. F., de Sousa, I. R., Simões, H. G., & Campbell, C. S. Traditional games resulted in post-exercise hypotension and a lower cardiovascular response to the cold pressor test in healthy children. Frontiers in Physiology, 2014,5, 235. [CrossRef]

- Anand, S., Bradshaw, C. & Prabhakaran, D. Prevention and management of CVD in LMICs: why do ethnicity, culture, and context matter? BMC Med. 2020,18, 7. [CrossRef]

- Minja, N. W., Nakagaayi, D., Aliku, T., Zhang, W., Ssinabulya, I., Nabaale, J., Amutuhaire, W., de Loizaga, S. R., Ndagire, E., Rwebembera, J., Okello, E., & Kayima, J. Cardiovascular diseases in Africa in the twenty-first century: Gaps and priorities going forward. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine. (2022), 9, 1008335. [CrossRef]

- Shaw, I., Boshoff, V.E., Coetzee S. & Shaw B.S. Shaw, I., Boshoff, V.E., Coetzee S. & Shaw B.S. Efficacy of home-based callisthenic resistance training on cardiovascular disease risk in overweight compared to normal weight preadolescents. Asian Journal of Sports Medicine. 2021,12(1): 1–5, e106591.

- Mayowa Owolabi, Jaime J Miranda, Joseph Yaria, Bruce Ovbiagele - Controlling cardiovascular diseases in low- and middle-income countries by placing proof in pragmatism: BMJ Global Health. 2016;1:e000105. [CrossRef]

- Aminde, L.N., Takah, N.F., Zapata-Diomedi, B. et al. Primary and secondary prevention interventions for cardiovascular disease in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review of economic evaluations. Cost Eff Resour Alloc, 2018, 16, 22. [CrossRef]

| Study | Participant Description | Study Aim | Intervention | Outcome and measures | Key Findings and Conlusions | Limitations |

| Duarte et al., 2023 [29] Non-RCT Brazil |

N=26 Women Age= 20- 40 years old |

To investigate the effect of 12 weeks of rehearsals on cardiorespiratory parameters and body composition in Brazil samba dancers belonging to a first-league samba school | Brazilian samba dance 12 weeks |

Cardiorespiratory parameters Body composition |

Samba dance can increase PA levels and positively affect the dancers’ health parameters. ↑ maximal oxygen uptake ↑ oxygen pulse ↑ lean body mass ↓ body fat % ↓ fat mass |

Only one Samba school with a small sample size was used. Samba schools practice different samba with different intensities, causing varying effects on cardiorespiratory parameters and body composition Evaluation of HR measurements during rehearsals and body composition evaluations were not performed with standard tools. |

| Wang et al., 2023 [30] RCT China |

N=26 Women Age - Not stated |

To examine the effects of simplified dance on body composition, cardiorespiratory fitness, and blood lipids in obese older women. | Simplified dance 12 weeks |

Anthropometric measures Cardiorespiratory fitness Blood lipids |

Simple dance interventions have potential to improve blood composition and aerobic fitness in obese older women. ↑VO₂ max ↑ High-Density lipoprotein (HDL-C) ↓ Total Cholesterol (TC) |

Sample only was for women with obesity and results cannot be generalised for other populations including men. Biomechanical evaluations were not performed in the current study. |

| Daca et al., 2023 [24] RCT Mozambique |

N=57 older women Age: 60 -80 years old |

To compare the effects of Conventional Exercise Program CEP) and Culturally Relevant Activities (CRA) on markers of risk factors cardiovascular diseases, body composition, functional fitness, and self confidence in older women in living in Maputo City, Mozambique. | CEP (CEP (stationary cycling, resistance circuit training) CRA (games and dances) 12 weeks |

Body fat Resting blood pressure Blood Glycemic, Cholesterol, Triglycerides, and High-Density lipoprotein Physical fitness Self-efficacy Self-esteem |

Both has positive effects on biological and psychological health of older women: ↑ cardiorespiratory fitness and ↑ Triglycerides ↑ physical fitness ↑ functional fitness ↑improved quality of life |

Relatively low sample size and only females. There was no control to training intensity and volume in CRA sessions - no equipment was used on individuals compared to CEP ergometric equipment The self-efficacy tool was not sensitive enough to detect changes. No follow up post intervention period. |

| Ajala et al., 2020 [31] RCT Nigeria |

N=30 Obese men Age=18 - 22 years old |

To find out the effect of aerobic dance training on selected health related fitness variables among obese men | Aerobic dance 8 weeks |

Cardiorespiratory endurance Body composition |

Aerobic dance improved body composition and cardiorespiratory endurance. |

Not stated |

| Gebretensay et al., 2018 [32] RCT Ethiopia |

N=100 Boys and Girls Age = 15 to 17 years old |

To evaluate the effect of Tigray dance on selected physiological variables among high school students. | Traditional dance of Tigray 16 weeks |

Heart rate Systolic Blood Pressure DBP |

Traditional dance treatment groups showed significant improvement physiological variables, resting HR, SBP, DBP |

Not stated |

| Rodrigues-Krause et al., 2018 [13] RCT Brazil |

N=30 Sedentary women Age= 60 -75 years old |

To compare the effects of dancing and walking on cardiovascular disease and functionality of older women. | Dancing – several styles 8 weeks |

Cardiorespiratory fitness Body composition Lipid profile VO₂ peak Balance |

In large clinical relevance. ↑ CRF in walking ↑ lower body muscle power in dancing Increased PA levels were noted. ↑VO₂peak ↓body composition ↑ lipid and inflammatory profile |

Small size sample to detect the differences on a variety of outcomes assessed. No follow up post intervention period. |

| Nxumalo et al., 2015 [33] Non-RCT South Africa |

N=44 Male children Age= 9 -10 years old |

To investigate the potential influence of the traditional Zulu stick fighting game on health-related physical fitness of prepubescent males. | Indigenous game- Zulu stick fighting 10 weeks |

Body composition Cardiovascular fitness Muscle endurance and strength |

Significant differences were noted. ↑ cardiovascular fitness ↓ body composition ↑ flexibility No significant change – muscle strength and endurance. |

Small sample size, limiting effect on statistical power of analysis. |

| Kin et al., 2001 [34] Non-RCT Turkey |

N=45 Female college students Age: SA=21.88±2.16; AD=20.23±0.16; Control =21.88±1.82 years old |

To examine the effects of 8-weeks of step aerobics and aerobic dancing on blood lipids and lipoproteins. | Aerobic Dance 8 weeks |

Cardiovascular risk factors Blood lipids Lipoproteins |

Step aerobics training had more benefits than aerobic dancing in; serum TC, HDL-C levels, and TC: HDL-C ratio. Favourable changes in serum TC levels resulted after aerobic dancing. |

The conclusions of the study must be limited to the studied population. |

| Study | Participants | Aim | Intervention | Outcome | Key Findings | Limitations |

| Manihuruk et al., 2024 [35] Non-RCT Indonesia |

N=30, Children, Age: 9-11 years old |

Measure intensity of Malaysian traditional games | 5 traditional games, 7 weeks | Body measures, HR, METs, Vector magnitude | 3 games met MVPA standards for steps, HR, vector magnitude | Upper body motions not well assessed, findings limited to northern regions |

| Yulia et al., 2021 [36] | Non-RCT, Indonesia, N=72, Students, Age: Not stated | To check nutrition education and Javanese games on lipids in overweight kids | Traditional games, Nutrition education, 3 months | Cholesterol, Triglycerides, Lipid profiles (LDL-C, HDL-C) | Games lowered cholesterol and triglycerides but didn’t improve lipid profiles | Not stated |

| Malik et al., 2021 [19] | Non-RCT, Malaysia, N=600 (300 boys, 300 girls), Age: 10.2±0.8 years old | To measure exercise intensity and enjoyment | 5 games | Body measures, HR, METs, Enjoyment response | Games supported MVPA and boosted enjoyment, aiding health and exercise habits | HR results were post-game only, limited to 5 games |

| Rauber et al., 2014 [37] | Non-RCT, Brazil, N=16 (8 boys, 8 girls), Age: 9-10 years old | To check if BP stress reactions drop after play vs sedentary activity | Traditional games, Video games | Post-exercise BP, SBP, DBP | Games reduced BP stress response after one session | Small sample, gender comparison not possible, short monitoring time, genetics and ethnicity not considered |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).