Submitted:

22 April 2025

Posted:

22 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

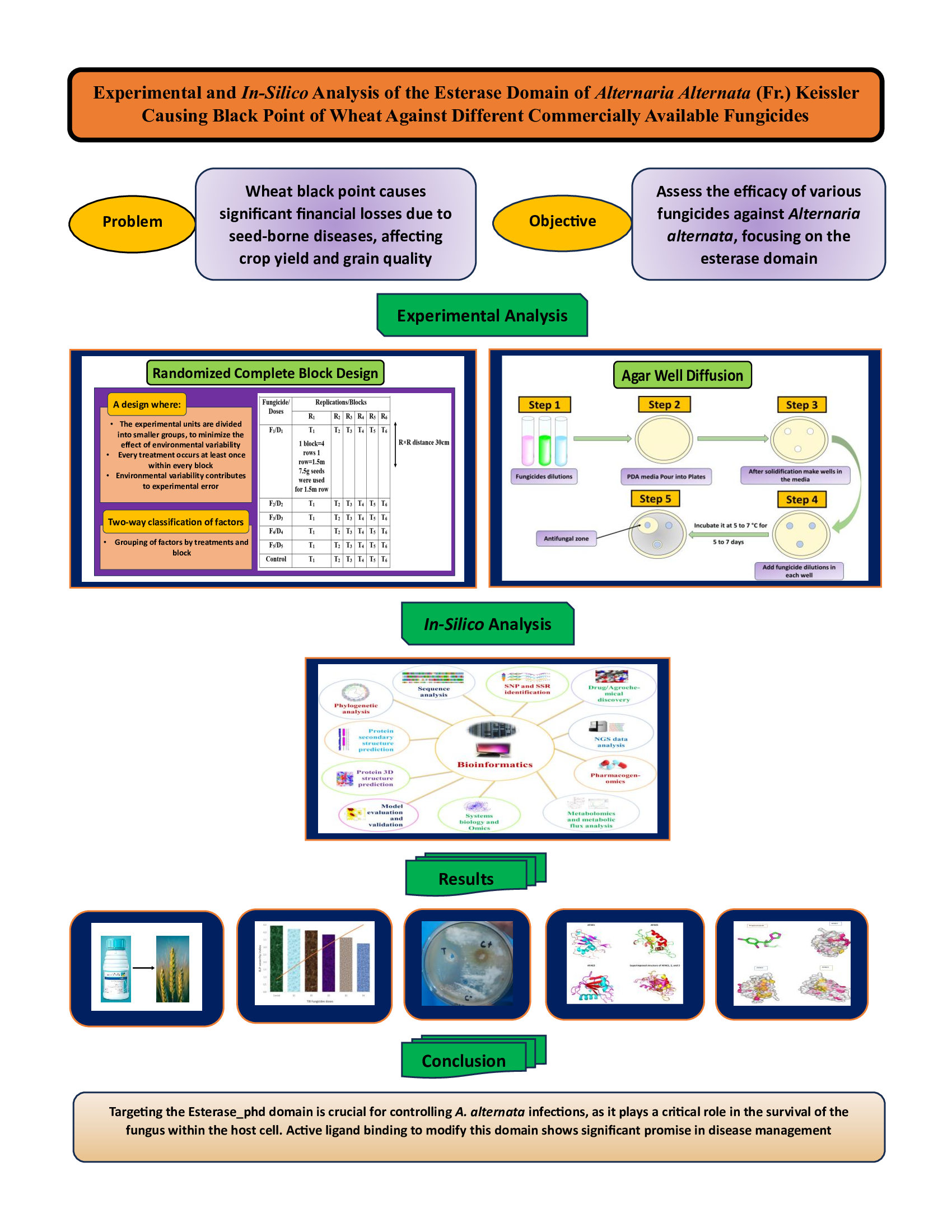

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

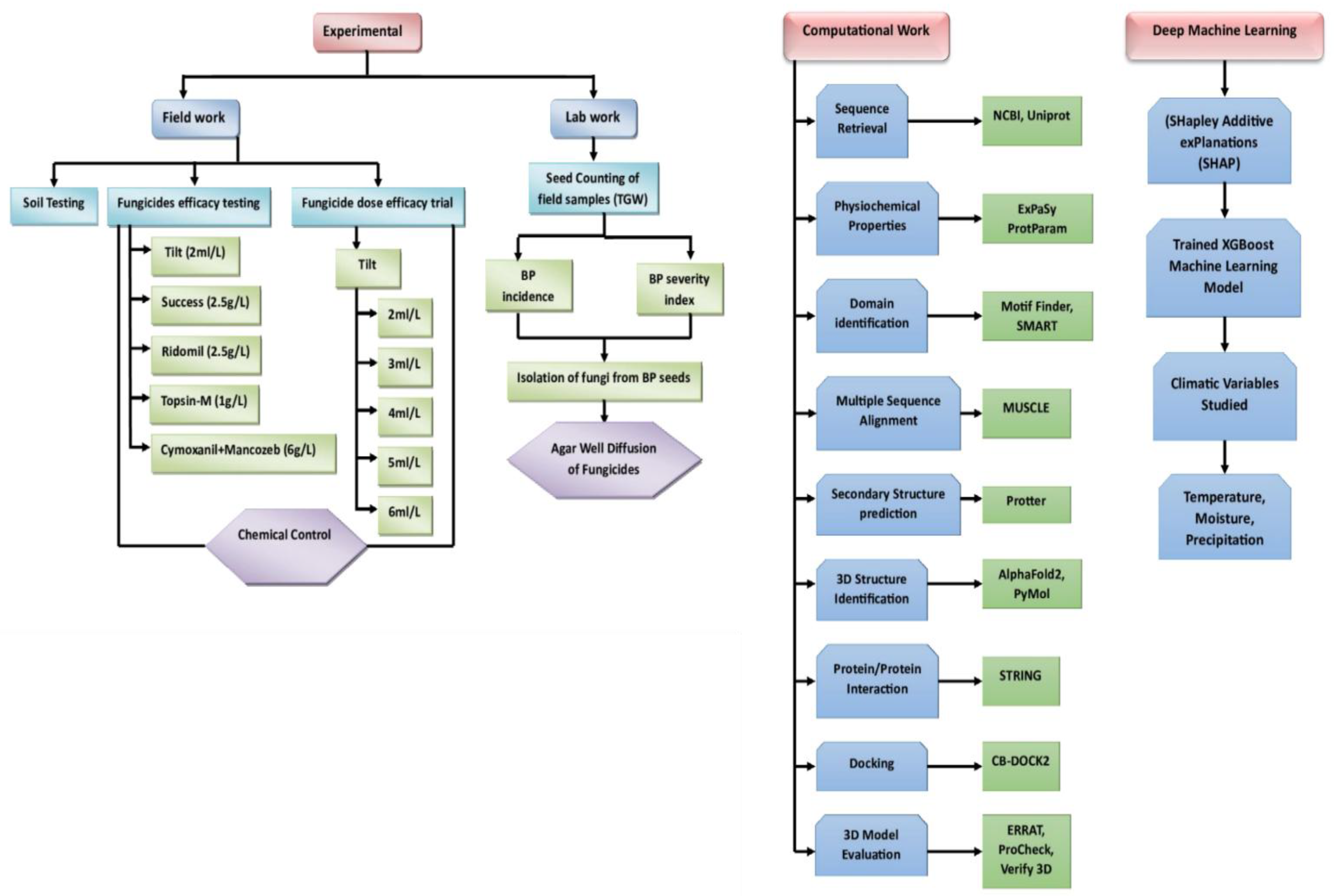

Material and Methods

Study Design

Ethical Approval

Field Work

Laboratory Work

In-Silico Analysis

Molecular Docking

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Machine Learning and Explainable AI Analysis of Climatic Impacts on Fungicide Efficacy

Dataset Collection and Overview

Preprocessing

Data Analysis

ResultsField Results

Laboratory Results

In-Silico Analysis Results

Sequence Retrieval

Analysis of Physiochemical Properties

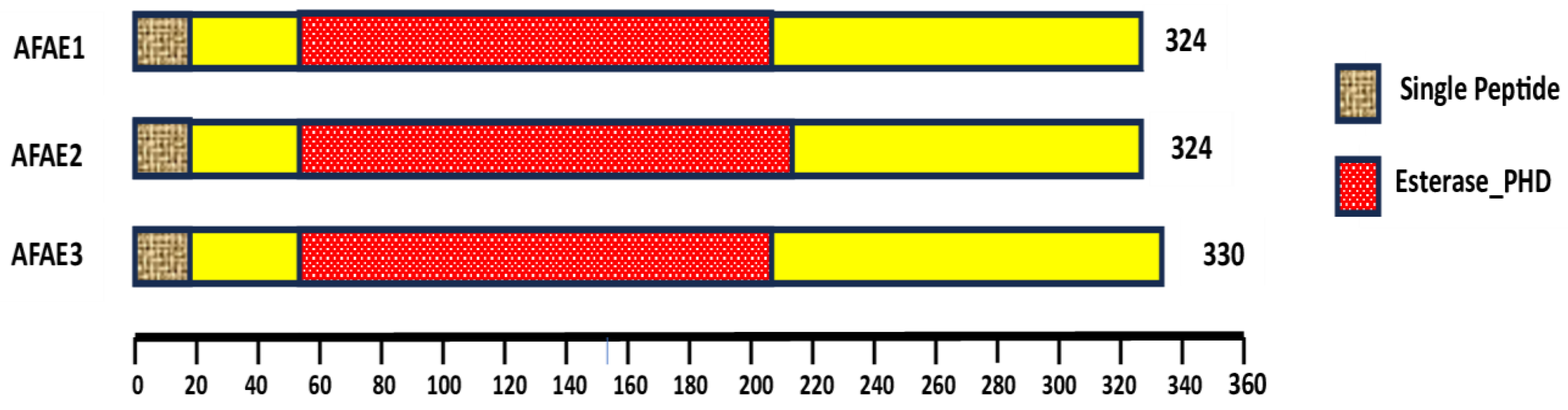

Protein Domain Analysis

Protein Sequence Alignment

Secondary Structure Prediction

Visualization of Alphafold3 predicted Structures

Verify 3D, Errat and ProCheck

Ramachandran Plot

Protein to Protein Interactions

Ligand Binding

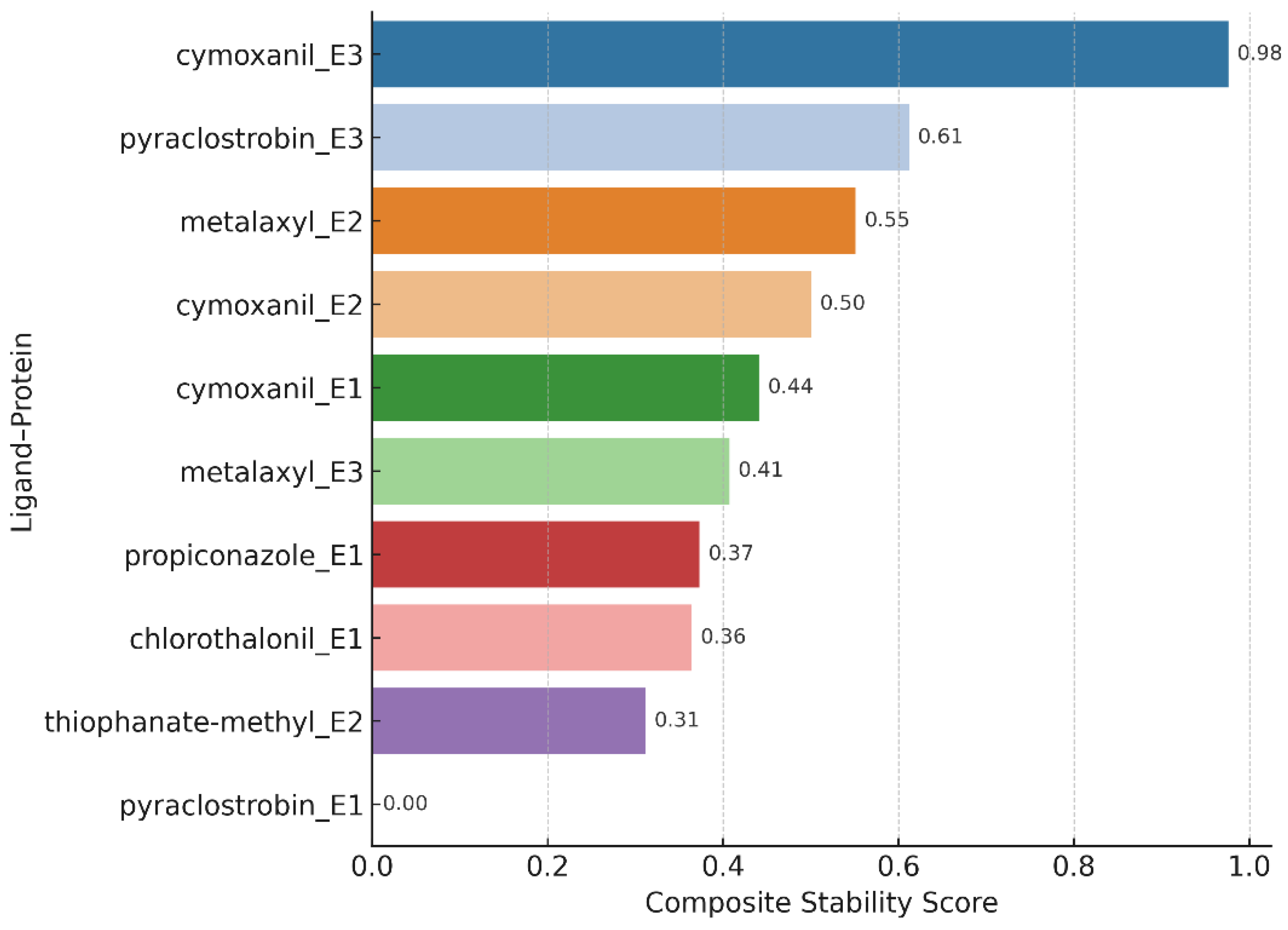

Docking and MD Simulations

Molecular Docking Identifies Metalaxyl and Pyraclostrobin as Top Candidates

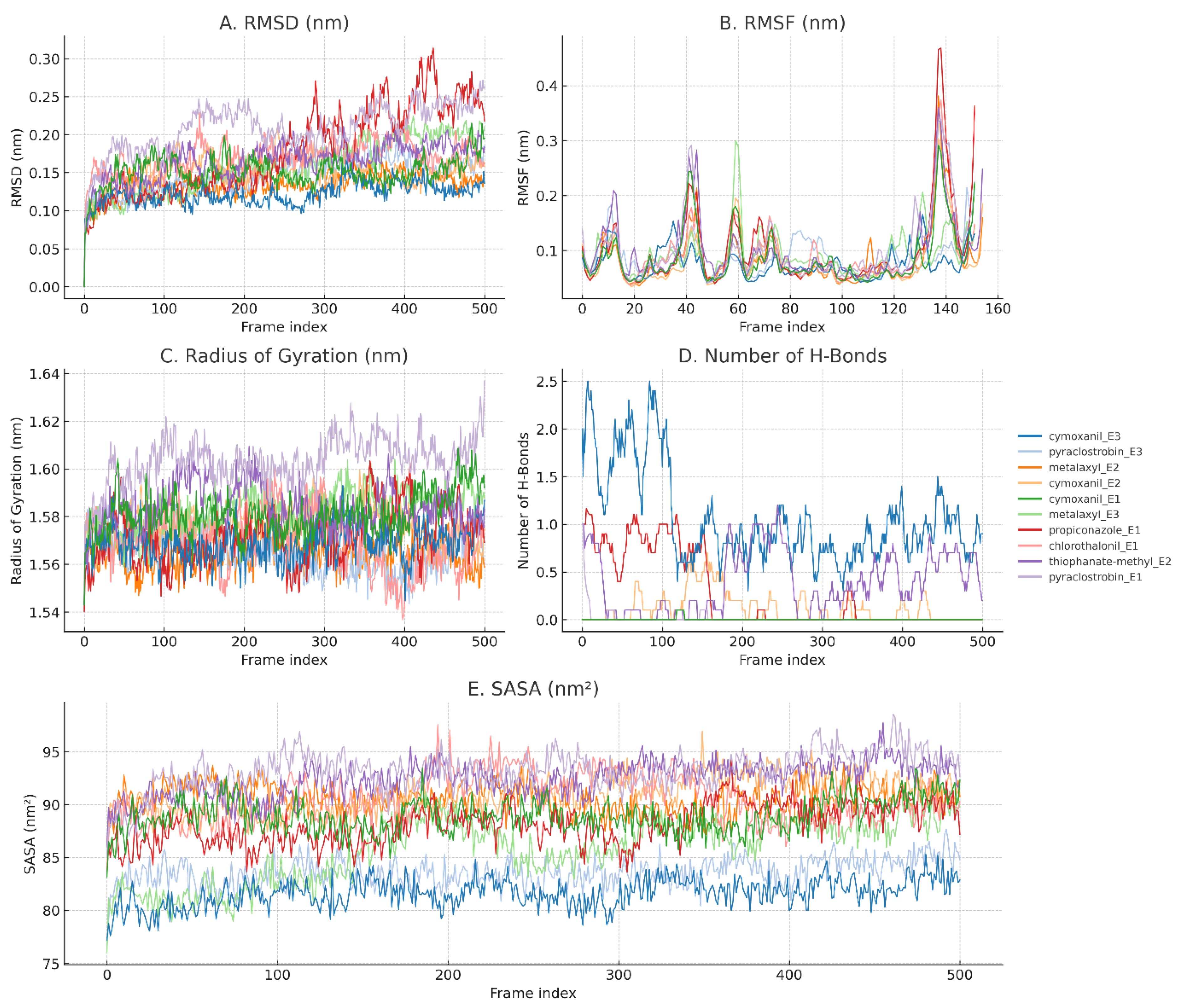

Molecular Dynamics Confirms Binding Stability for Metalaxyl and Cymoxanil Complexes

RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation)

Radius of Gyration (Rg)

RMSF (Root Mean Square Fluctuation)

SASA (Solvent Accessible Surface Area)

Hydrogen Bonding

| Ligand_Protein | Docking_Affinity (kcal/mol) | RMSD_Mean (nm) | Rg_Mean (nm) | Hbond_Avg | SASA_Avg (nm²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pyraclostrobin_e3 | -6.6 | 0.147 | 1.566 | 0 | 83.58 |

| pyraclostrobin_e1 | -6.4 | 0.209 | 1.603 | 0.01 | 93.23 |

| thiophanate-methyl_e2 | -5.7 | 0.165 | 1.584 | 0.39 | 92.4 |

| propiconazole_e1 | -5.6 | 0.178 | 1.572 | 0.26 | 88.16 |

| metalaxyl_e2 | -5.4 | 0.135 | 1.564 | 0 | 90.54 |

| cymoxanil_e2 | -5.1 | 0.148 | 1.576 | 0.12 | 90.9 |

| metalaxyl_e3 | -5 | 0.157 | 1.583 | 0 | 85.78 |

| cymoxanil_e1 | -4.6 | 0.151 | 1.581 | 0 | 88.95 |

| cymoxanil_e3 | -4.5 | 0.122 | 1.569 | 1.05 | 81.62 |

| chlorothalonil_e1 | -4.4 | 0.17 | 1.569 | 0 | 90.54 |

Machine Learning & xAI: Performance of Pesticides Under Various Climate Conditions

Effect of Individual Weather Parameters on Pesticide Performance

Temperature and Fungicides Combined Efficacy

Humidity and Fungicides Combined Efficacy

Precipitation and Fungicide Efficacy

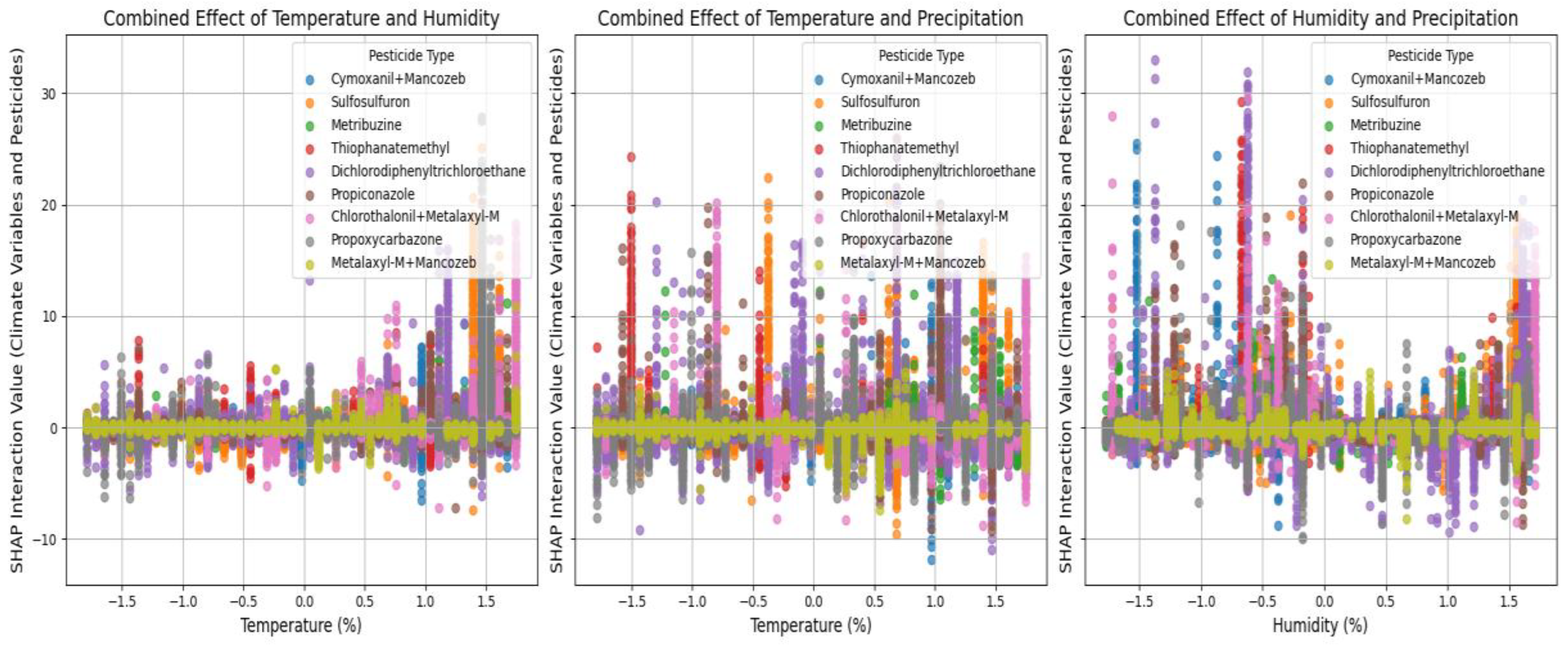

Pairwise Interactions Between Climate Variables and Pesticides

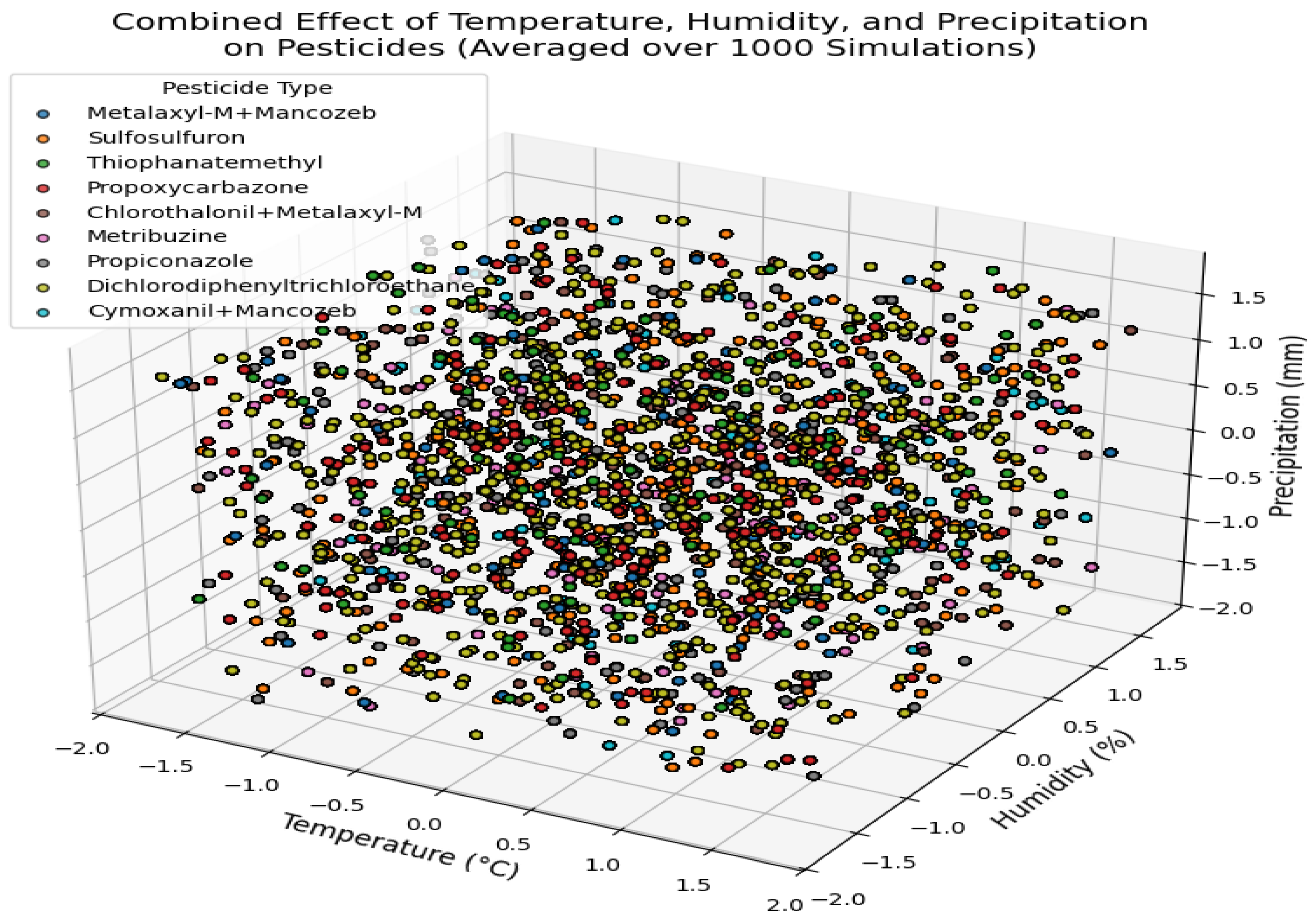

Triple Interaction Analysis of Climate Variables on Pesticides Efficacy

Discussion

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Declaration of Interest Statement

Disclosure Statement

References

- Abade, A., Ferreira, P. A., & de Barros Vidal, F. (2021). Plant diseases recognition on images using convolutional neural networks: A systematic review. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 185, 106125.

- Achilonu, C. C., Gryzenhout, M., Ghosh, S., & Marais, G. J. (2023). In Vitro Evaluation of Azoxystrobin, Boscalid, Fentin-Hydroxide, Propiconazole, Pyraclostrobin Fungicides against Alternaria alternata Pathogen Isolated from Carya illinoinensis in South Africa. Microorganisms, 11(7).

- Alastruey-Izquierdo, A., Melhem, M. S., Bonfietti, L. X., & Rodriguez-Tudela, J. L. (2015). Susceptibility test for fungi: clinical and laboratorial correlations in medical mycology. Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de São Paulo, 57, 57-64.

- Ali, Y., Abbas, T., Aatif, H. M., Ahmad, S., Khan, A. A., & Hanif, C. M. S. (2022). Impact of Foliar Applications of Different Fungicides on Wheat Stripe Rust Epidemics and Grain Yield. Pakistan Journal of Phytopathology, 34(1), 135–141.

- Arnal Barbedo, J. G. (2013). Digital image processing techniques for detecting, quantifying and classifying plant diseases. SpringerPlus, 2(1), 660.

- Asif, M., Strydhorst, S., Strelkov, S. E., Terry, A., Harding, M. W., Feng, J., & Yang, R. C. (2021). Evaluation of disease, yield and economics associated with fungicide timing in Canadian Western Red Spring wheat. Canadian Journal of Plant Science, 101(5), 680–697.

- Balouiri, M., Sadiki, M., & Ibnsouda, S. K. (2016). Methods for in vitro evaluating antimicrobial activity: A review. Journal of Pharmaceutical Analysis, 6(2), 71–79.

- Binkowski, T. A. (2003). CASTp: Computed Atlas of Surface Topography of proteins. Nucleic Acids Research, 31(13), 3352–3355.

- Barlow, K. M., Christy, B. P., O’Leary, G. J., Riffkin, P. A., & Nuttall, J. G. (2015). Simulating the impact of extreme heat and frost events on wheat crop production: A review. Field crops research, 171, 109-119.

- Box, P. O. (2015). States Environmental Protection Agency. Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) National Analysis, 703.

- Brown, P., Baxter, L., Hickman, R., Beynon, J., Moore, J. D., & Ott, S. (2013). MEME-LaB: motif analysis in clusters. Bioinformatics, 29(13), 1696–1697.

- Chi, D. H., Giap, V. D., Anh, L. P. H., & Nghi, D. H. (2017). Feruloyl esterase from Alternaria tenuissima that hydrolyses lignocellulosic material to release hydroxycinnamic acids. Applied Biochemistry and Microbiology, 53(6), 654–660.

- COTUNA, O., PARASCHIVU, M., SĂRĂȚEANU, V., DURĂU, C., & RECHIȚEAN, I. (2020). Research Regarding the Identification of the Fungus“Black Point” in Several Wheat Varieties Cultivated in Western Romania (Case Study). Life Science and Sustainable Development, 1(2), 25–31.

- Crepin, V. F., Faulds, C. B., & Connerton, I. F. (2004). Functional classification of the microbial feruloyl esterases. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 63(6), 647–652.

- Cromey, M. G., & Mulholland, R. I. (1988). Blackpoint of wheat: Fungal associations, cultivar susceptibility, and effects on grain weight and germination. New Zealand Journal of Agricultural Research, 31(1), 51–56.

- Dasharathbhai Ajayabhai, C., Kedar Nath, Bekriwala, T., & Mabhu Bala. (2018). Management of Alternaria leaf blight of groundnut caused by Alternaria alternata. Indian Phytopathology, 71(4), 543–548.

- Degewione, A., & Alamerew, S. (2013). Genetic Diversity in Bread Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Genotypes. Pakistan Journal of Biological Sciences, 16(21), 1330–1335.

- DeLano, W., & Bromberg, S. (2004). PyMOL User’s Guide (Original). DeLano Scientific LLC, 1–66.

- Draz, I. S., El-Gremi, S. M., & Wassief Abd-Elsamad Youssef. (2016). Pathogens associated with wheat black-point disease and responsibility in pathogenesis. Journal of Environmental and Agricultural Sciences, 8(September 2016), 71–78.

- Draz, I. S., El-Gremi, S. M., & Youssef, W. A. (2016). Response of Egyptian wheat cultivars to kernel black point disease alongside grain yield. Pakistan Journal of Phytopathology, 28(1 PG-15–17), 15–17.

- Edgar, R. C., & Batzoglou, S. (2006). Multiple sequence alignment. Current Opinion in Structural Biology, 16(3), 368–373.

- Eisenberg, D., Lüthy, R., & Bowie, J. U. (1997). [20] VERIFY3D: Assessment of protein models with three-dimensional profiles (pp. 396–404).

- El-Gremi, S. M., Draz, I. S., & Youssef, W. A.-E. (2017). Biological control of pathogens associated with kernel black point disease of wheat. Crop Protection, 91, 13–19.

- Ferentinos, K. P. (2018). Deep learning models for plant disease detection and diagnosis. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 145, 311–318.

- Fernandes, C., Casadevall, A., & Gonçalves, T. (2023). Mechanisms of Alternaria pathogenesis in animals and plants. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 47(6).

- Fernandez, M. R., & Conner, R. L. (2011). Black Point and Smudge in Wheat Kernel Discolouration in Common and Durum Wheat. 4, 158–164.

- Figueroa, M., Hammond-Kosack, K. E., & Solomon, P. S. (2018). A review of wheat diseases-a field perspective. Molecular Plant Pathology, 19(6), 1523–1536.

- Fisher, M. C., Henk, D. A., Briggs, C. J., Brownstein, J. S., Madoff, L. C., McCraw, S. L., & Gurr, S. J. (2012). Emerging fungal threats to animal, plant and ecosystem health. Nature, 484(7393), 186–194. h.

- Gasteiger, E., Hoogland, C., Gattiker, A., Duvaud, S., Wilkins, M. R., Appel, R. D., & Bairoch, A. (2005). Protein Identification and Analysis Tools on the ExPASy Server. In The Proteomics Protocols Handbook (pp. 571–607). Humana Press.

- Gaulton, A., Bellis, L. J., Bento, A. P., Chambers, J., Davies, M., Hersey, A., Light, Y., McGlinchey, S., Michalovich, D., Al-Lazikani, B., & Overington, J. P. (2012). ChEMBL: a large-scale bioactivity database for drug discovery. Nucleic Acids Research, 40(D1), D1100–D1107.

- Griffin, H. G., & Griffin, A. M. (1995). National centre for biotechnology information (NCBI): Services provided for the molecular biotechnologist. Molecular Biotechnology, 4(2), 206–206.

- Guillermo Fuentes-Dávila, Ivón Alejandra Rosas-Jáuregui, Carlos Antonio Ayón-Ibarra, José Luis Félix-Fuentes, Pedro Félix-Valencia, & María Monserrat Torres-Cruz. (2023). Incidence of black point (Alternaria sp.) in elite advanced bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) lines. GSC Biological and Pharmaceutical Sciences, 25(2), 222–229.

- Haque, M. A., Marwaha, S., Deb, C. K., Nigam, S., Arora, A., Hooda, K. S., ... & Agrawal, R. C. (2022). Deep learning-based approach for identification of diseases of maize crop. Scientific reports, 12(1), 6334.

- Hou, Y.-H., Yang, Z.-H., Wang, J.-Z., & Yang, Q.-Z. (2022). Characterization of a thermostable alkaline feruloyl esterase from Alternaria alternata and its synergism in dissolving pulp production. Biochemical Engineering Journal, 187, 108657.

- Ijaz, M., Afzal, A., Ashraf, M. M., Ali, S. R., & ul Haq, M. I. (2018). Integrated Disease Management of Black point in Wheat in Punjab (Pakistan). Plant Protection, 2(2), 63-68.

- Iqbal, M. F., Hussain, M., Ali, M. A., Nawaz, R., & Iqbal, Z. (2014). Efficacy of fungicides used for controlling black point disease in wheat crop. Int. J. Adv. Res. Bio. Sci, 1(6), 59-64.

- Kassaw, A., Mihretie, A., & Ayalew, A. (2021). Rate and Spraying Frequency Determination of Propiconazole Fungicide for the Management of Garlic Rust at Woreilu District, Northeastern Ethiopia. Advances in Agriculture, 2021, 1–9.

- Kamilaris, A., & Prenafeta-Boldú, F. X. (2018b). Deep learning in agriculture: A survey. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 147, 70–90.

- Kharin, V. V., Zwiers, F. W., Zhang, X., & Wehner, M. (2013). Changes in temperature and precipitation extremes in the CMIP5 ensemble. Climatic change, 119, 345-357.

- Kustrzeba-Wójcicka, I., Siwak, E., Terlecki, G., Wolańczyk-Mędrala, A., & Mędrala, W. (2014). Alternaria alternata and Its Allergens: a Comprehensive Review. Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology, 47(3), 354–365.

- Laskowski, R. A., MacArthur, M. W., Moss, D. S., & Thornton, J. M. (1993). PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. Journal of Applied Crystallography, 26(2), 283–291.

- Lee, G. Y., Alzamil, L., Doskenov, B., & Termehchy, A. (2021). A survey on data cleaning methods for improved machine learning model performance. arXiv preprint arXiv:2109.07127.

- Liu, Y., Yang, X., Gan, J., Chen, S., Xiao, Z.-X., & Cao, Y. (2022). CB-Dock2: improved protein–ligand blind docking by integrating cavity detection, docking and homologous template fitting. Nucleic Acids Research, 50(W1), W159–W164.

- Long, M., Hartley, M., Morris, R. J., & Brown, J. K. M. (2023). Classification of wheat diseases using deep learning networks with field and glasshouse images. Plant Pathology, 72(3), 536–547.

- Lore, J. S., & Thind, T. S. (2012). Performance of different fungicides against multiple diseases of rice. Indian Phytopathology.

- Malaker, P. K., & Mian, I. H. (2009). Effect of seed treatment and foliar spray with fungicides in controlling black point disease of wheat. Bangladesh Journal of Agricultural Research, 34(3), 425-434.

- Manamgoda, D. S., Rossman, A. Y., Castlebury, L. A., Chukeatirote, E., & Hyde, K. D. (2015). A taxonomic and phylogenetic re-appraisal of the genus Curvularia (Pleosporaceae): Human and plant pathogens. Phytotaxa, 212(3), 175–198.

- Masiello, M., Somma, S., Susca, A., Ghionna, V., Logrieco, A. F., Franzoni, M., Ravaglia, S., Meca, G., & Moretti, A. (2020). Molecular identification and mycotoxin production by alternaria species occurring on durum wheat, showing black point symptoms. Toxins, 12(4).

- Merck. (2006). Potato Dextrose Agar. Merck Microbiology Manual, 12, 1–2.

- Mohanty, S. P., Hughes, D. P., & Salathé, M. (2016). Using Deep Learning for Image-Based Plant Disease Detection. Frontiers in Plant Science, 7.

- Moshatati, A., & Gharineh, M. H. (2012). Effect of grain weight on germination and seed vigor of wheat. International Journal of Agriculture and Crop Sciences, 4(8), 458–460.

- Muhsin, M., Nawaz, M., Khan, I., Chattha, M. B., Khan, S., Aslam, M. T., Iqbal, M. M., Amin, M. Z., Ayub, M. A., Anwar, U., Hassan, M. U., & Chattha, M. U. (2021). Efficacy of Seed Size to Improve Field Performance of Wheat under Late Sowing Conditions. Pakistan Journal of Agricultural Research, 34(1).

- Naik, B. N., Malmathanraj, R., & Palanisamy, P. (2022). Detection and classification of chilli leaf disease using a squeeze-and-excitation-based CNN model. Ecological Informatics, 69, 101663.

- Nithya, U., Chelladurai, V., Jayas, D. S., & White, N. D. G. (2011). Safe storage guidelines for durum wheat. Journal of Stored Products Research, 47(4), 328–333.

- Peila, D., Picchio, A., Martinelli, D., & Negro, E. D. (2016). Laboratory tests on soil conditioning of clayey soil. Acta Geotechnica, 11(5), 1061–1074.

- Rani, P., & Singh, A. (2018). Effect of Black Point Infection on Germination of different varieties of Wheat Seed. I.

- Prendin, F., Pavan, J., Cappon, G., Del Favero, S., Sparacino, G., & Facchinetti, A. (2023). The importance of interpreting machine learning models for blood glucose prediction in diabetes: an analysis using SHAP. Scientific reports, 13(1), 16865.

- Savary, S., Willocquet, L., Pethybridge, S. J., Esker, P., McRoberts, N., & Nelson, A. (2019). The global burden of pathogens and pests on major food crops. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 3(3), 430–439.

- Schultz, J., Milpetz, F., Bork, P., & Ponting, C. P. (1998). SMART, a simple modular architecture research tool: Identification of signaling domains. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 95(11), 5857–5864.

- SESİZ, U. (2023). The Screening of Black Point in Commercial Bread Wheat Cultivars Grown in Turkey, and The Effect of Black Point on Thousand Grain Weight. Yüzüncü Yıl Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü Dergisi, 28(1), 230–238.

- Shahwani, A. R., Sana, U. B., Shahbaz, K. B., Baber, M., Waseem, B., Hafeez, N. B., Rameez, A. B., Sial, A. H., Sabiel, S. A. I., Kamran, R., Ayaz, A. S., & Ashraf, M. (2014). INFLUENCE OF SEED SIZE ON GERMINABILITY AND GRAIN YIELD OF WHEAT ( Triticum Aestivum L . ) VARIETIES. Journal of Natural Sciences Research, 4(23), 1–11.

- Shukla, D. N., Shrivastava, J. P., & Yadav, M. K. (2020). Occurrence of Black Point Disease Complex of Wheat in Eastern Uttar Pradesh. Www. Groupexcelindia. Com, November.

- Srivastava, J. P., Kushwaha, G. D., & Shukla, D. N. (2015). Black point disease of wheat and its implications on seed quality. Crop Research, 47(1to3), 21-23.

- Abramson, J., Evans, R., Bryant, P., Ingale, A., Johansson-Åkhe, I., Pan, J. et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 629, 289–298 (2024).

- Strange, R. N., & Scott, P. R. (2005). Plant Disease: A Threat to Global Food Security. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 43(1), 83–116.

- Sutaji, D., & Yıldız, O. (2022). LEMOXINET: Lite ensemble MobileNetV2 and Xception models to predict plant disease. Ecological Informatics, 70, 101698.

- Szklarczyk, D., Franceschini, A., Wyder, S., Forslund, K., Heller, D., Huerta-Cepas, J., Simonovic, M., Roth, A., Santos, A., Tsafou, K. P., Kuhn, M., Bork, P., Jensen, L. J., & von Mering, C. (2015). STRING v10: protein–protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Research, 43(D1), D447–D452.

- Talukder, A. S. M. H. M., McDonald, G. K., & Gill, G. S. (2014). Effect of short-term heat stress prior to flowering and early grain set on the grain yield of wheat. Field Crops Research, 160, 54-63.

- Taylor, N. P., & Cunniffe, N. J. (2023). Coupling machine learning and epidemiological modelling to characterise optimal fungicide doses when fungicide resistance is partial or quantitative. Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 20(201), 20220685.

- UniProt: a hub for protein information. (2015). Nucleic Acids Research, 43(D1), D204–D212.

- Wang, Y., Wu, S., Chen, J., Zhang, C., Xu, Z., Li, G., Cai, L., Shen, W., & Wang, Q. (2018). Single and joint toxicity assessment of four currently used pesticides to zebrafish (Danio rerio) using traditional and molecular endpoints. Chemosphere, 192, 14–23.

- Wiederstein, M., & Sippl, M. J. (2007). ProSA-web: interactive web service for the recognition of errors in three-dimensional structures of proteins. Nucleic Acids Research, 35(Web Server), W407–W410.

- Xu, K. G., Jiang, Y. M., Li, Y. K., Xu, Q. Q., Niu, J. S., Zhu, X. X., & Li, Q. Y. (2018). Identification and Pathogenicity of Fungal Pathogens Causing Black Point in Wheat on the North China Plain. Indian Journal of Microbiology, 58(2), 159–164.

- Yadav, R. K., Ghasolia, R. P., & Yadav, R. K. (2020). Management of Alternaria alternata of Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) through Plant Extract and Fungicides in vitro and Natural Condition. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences, 9(5), 514–523.

- Zubrod, J. P., Bundschuh, M., Arts, G., Brühl, C. A., Imfeld, G., Knäbel, A., Payraudeau, S., Rasmussen, J. J., Rohr, J., Scharmüller, A., Smalling, K., Stehle, S., Schulz, R., & Schäfer, R. B. (2019). Fungicides: An Overlooked Pesticide Class? Environmental Science & Technology, 53(7), 3347.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).