1. Introduction

This article debates the imminent, if not already present, introduction and commoditisation of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in banking. The financial industry is witnessing a profound evolution in the 21st century, thanks in part to rapid advances in technological development. These technologies are offering an unprecedented opportunity to redesign banking operations and customer experiences (Batiz-Lazo et al., 2022), ultimately delivering a new paradigm, shifting from the traditional banking of the Relationship bank of the 13th century’ Banco di San Giorgio, the Industrial bank of the 18th century Barclays Bank in the UK or the Information Technology Bank of America of the 50s (Panzarino & Hatami, 2020; 7 in Papathomas & Konteos, 2023). The pressure to mirror digital giants like Google or Facebook’s interactive, seamless and flawless experience, is on for banking incumbents, who, now, need to renovate their back and front lines (Alnemer, 2022; Boustani, 2022). An opportunity to that end is given by AI-driven capabilities for natural, immediate customer interactions through conversational interfaces and advanced data analytics (Bilal et al., 2024). Financial institutions can exploit AI by introducing it in their everyday interactions with the public in customer support with chatbots, provision of financial advisors, fraud detection and prevention, recommendations of personalized banking products, automated investment management etc (Alnemer, 2022; Boustani, 2022; Fares et al., 2023). Such AI applications are having the potential to redefine customer interaction paradigms, setting new expectations for service delivery and information management (Omarini, 2018).

Yet, as many writers suggested e.g. Arjun R et al., (2021), Boustani N. M (2022), Alnemer, H. A., (2022), Ionașcu A. E. et al., (2023), the full-scale adoption of such advanced technology has not been realized universally, with a substantial number of institutions, mostly in non-digitally mature countries, lagging behind in the implementation. A factor that can influence that pace of digital transformation adoption and create a disparity between existing technological progress and the commercial use, is management hesitation over real attitudes of banking customers and other stakeholders (Liang et al., 2020). Such attitudes and respective behaviours, that, as per Mi Alnaser et al., (2023), can be far from conclusive, constitute the body of our study. Understanding public perception of this transformational element is crucial for the continued development and adoption of these innovations. This study seeks to contribute to the scholar knowledge of this critical area by examining the stakeholders’ perspective on AI in banking, focused on the semi-mature banking industry of Greece (Kitsios et al., 2021).

Greece offers a good playground for such a survey. Digital penetration is rather moderate within the incumbents of the Greek banking system, but the appetite and the potential are evident (Kitsios et al., 2021). The Hellenic Statistical Authority in its 2022 survey for employment skills registers over 40% of employees not having daily interaction with digital means. Yet, trends are fast changing with World Bank’s Digital Adoption Index ranking Greece 115th among 180 nations in 2014 but 129th in 2016. More recent evidence shows the turn of the society with 92% of Greek business executives already using ChatGPT (Kaspersky, 2023). Digital transformation is entering maturity and banks are picking up the pace of change. As per P. Milonas, CEO of NBG, a major Greek systemic bank, already 16% of bank’s products and services are offered via internet and mobile banking, with retail products reaching 80% digital coverage (2023).

Technology progress does not come in a vacuum though and its availability and the presence of technological capacity does not necessarily guarantee acceptance and adaptation by end users (Edo et al., 2023). This study aims to explore the behavioural barriers to the adoption of advanced technologies, such as the implementation of AI, among various and distinct audience groups, bank employees, technology professionals, students, other professions, by leveraging established statistical techniques and theoretical frameworks, providing a robust approach to understanding AI adoption in Greek banking, ultimately addressing gaps in the literature and offering actionable insights for practitioners (Alnemer, 2022; Rahi et al., 2019). The primary research questions the study aims to answer are:

Q1: What factors can affect positively or negatively the adoption of AI related technologies in Greek incumbent banks?

Q2: How strongly are these factors opposing or facilitating the adoption of the aforementioned technologies?

Q3: Are there differences in the acceptance of AI among different stakeholder groups?

2. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK AND HYPOTHESIS

2.1. Theoretical Background

The study explores technology adoption intentions in finance, focusing on digital banking and AI, fields extensively studied by scholars (Dendrinos & Spais, 2023; Fares et al., 2023; Zhou et al., 2010). Foundational frameworks like the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) by Davis (1986) and extensions, such as unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) and UTAUT-2 by Venkatesh et al., (2003, 2012), have been widely applied to understand technology acceptance behaviours. TAM underscores the importance of perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness, constructs that have consistently explained over 40% of the variance in user intentions (Legris et al., 2003). However, in contexts like AI in banking, where the environment is significantly different from conventional technology settings, researchers argue that traditional models may need refinement (Brown et al., 2002; Ahmad et al., 2020). UTAUT-2 incorporates constructs like hedonic motivation, price value, and habit, providing a more comprehensive framework for analysing AI's multilayered influences in banking (Gomber et al., 2017; Venkatesh et al., 2012). These models are particularly relevant in Greece, where digital transformation and AI adoption remain in early stages, as highlighted by Kitsios et al., (2021) and Saprikis et al., (2022).

To analyse the complex interrelationships among individual and institutional factors influencing AI adoption, the study employs Structural Equation Modelling (SEM), a robust methodology suitable for integrating latent and observed variables (Tarka, 2018; Yuan & Bentler, 2006). SEM allows for hypothesis testing in systems with intricate causal relationships and includes components of factor analysis and multiple regression (Blanthorne et al., 2006; Hair et al., 2018). The paper utilizes Partial Least Squares SEM (PLS-SEM), particularly effective in contexts like digital banking, where customer decision-making involves both conscious and subconscious factors (Bhatiasevi, 2016; Sharma et al., 2016). PLS-SEM aligns well with the TAM and UTAUT-2 frameworks, enabling the exploration of constructs such as performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, and facilitating conditions while accommodating emotional and cognitive dimensions.

Hypothesis Formulation

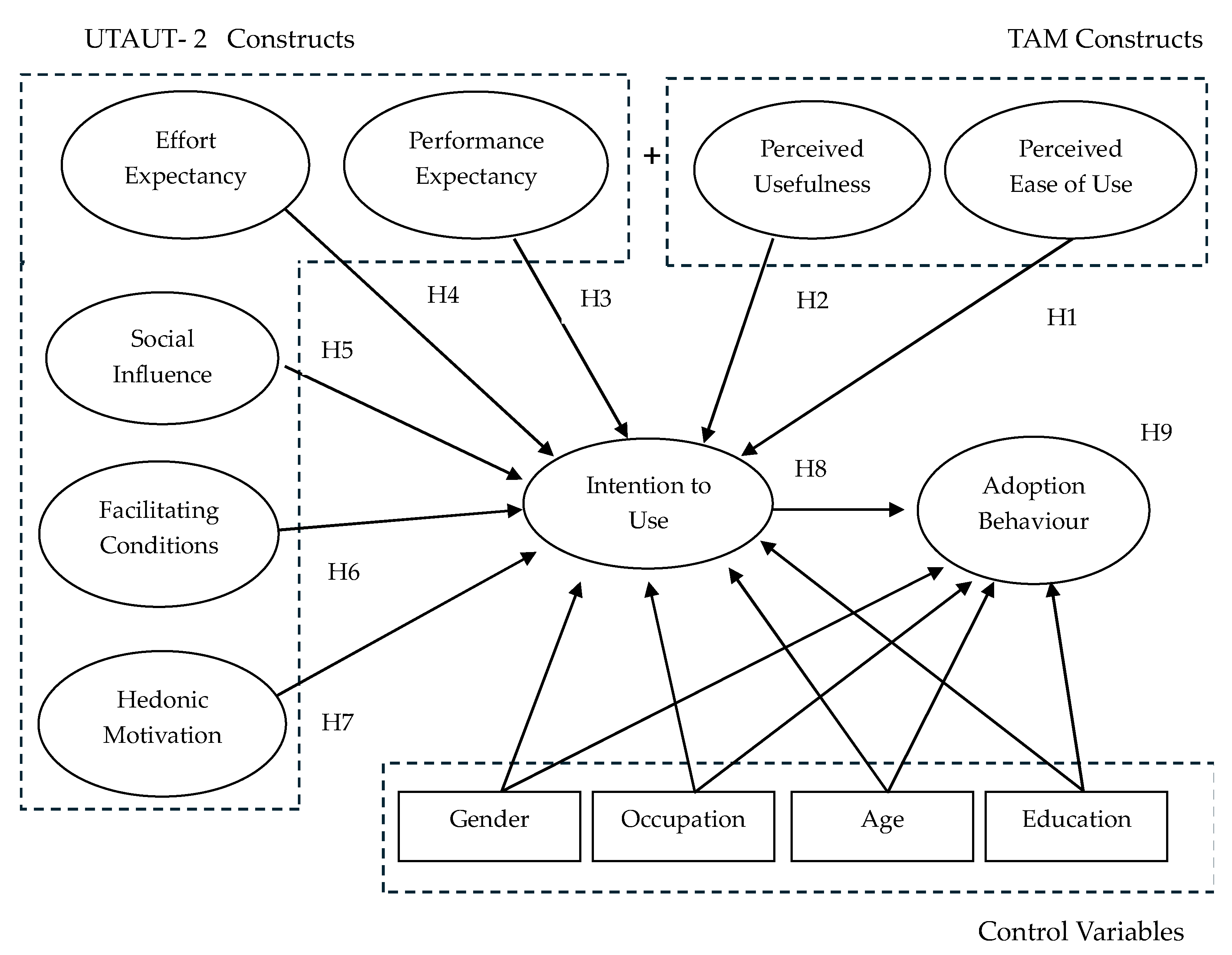

In the research construction, some key factors influencing the adoption of AI in Greece were identified based on the TAM criteria, i.e. Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) and Perceived Usefulness (PU), and Intention to Use (ItU), all analysed by many scholars (F. D. Davis, 1986; Hendrickson et al., 1993; Venkatesh & F. D. Davis, 2000). Other key factors that may be treated as inhibitors were the ones offered within the framework of UTAUT-2. Namely, Performance Expectancy (PE), Effort Expectancy (EE), Social Influence (SI) and Hedonic Motivation (HM) as well as Facilitating Conditions (FC). On the other hand, in the current landscape, where habitual use of AI technologies is still uncommon and where there are no defined fees or commissions associated with their use, the constructs of Price Value (PV) and Habit (H)—last introduced by UTAUT-2—were deemed inapplicable and so excluded from this study, agreeing with previous relevant research (Abed, 2021; Faqih & Jaradat, 2021). Demographic aspects such as gender, age, education level, occupation was employed as control variables in this study as per Faqih (2016) and Shiau et al., (2024).

2.2. Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU)

Interaction ease refers to the degree to which a person believes that using a system will be free of effort (Davis, 1986). Defined as the extent to which individuals perceive a technology or service to be easy to use, it reduces the complexity of the system, making it more likely that adoption decisions will be favourable (Bagozzi et al., 1999). This is a well-established factor, and one of the central ones in the setup of TAM framework. In AI banking, interaction easiness may relate to user interface design, simplifying customer interactions with complex financial services (Shaikh & Karjaluoto, 2015).

Key characteristics of new technology, such as the possibility of errors created unintentionally by the user, resources availability and instructions that help the user fulfil a task, time dedication, physical and mental effort required are key aspects in the perceived ease of use. Several scholars, in previously related studies have considered and evaluated positively the correlations, emphasising the importance of PEOU in evaluating user behaviour in digital and technological advancements, confirming the validity and reliability of these constructs in predicting user intention (Dhingra & Mudgal, 2019; Hendrickson et al., 1993; Workman, 2007). Consistent with the foundational works on technology acceptance models, ease of use is a fundamental determinant of behavioural intention (Venkatesh et al., 2012). Therefore:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Perceived Ease of Use influences Intention to Use in AI banking services

2.3. Perceived Usefulness (PU)

F.D. Davis (1986) in his doctoral seminal paper defined perceived usefulness as "the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system would enhance their performance”. Perceived usefulness has, along with ease of use, being in the centre of the TAM Model deployment measuring, in essence, the degree to which an individual considers that the technology in question will contribute positively to his or her job or everyday tasks performance (Dhingra & Mudgal, 2019; Hendrickson et al., 1993; Riffai et al., 2012). Dhingra and Mudgal, in their work (2019), notice that individuals are more likely to adopt technologies they perceive as easy to use and applicable across various tasks that improve their performance, increase business profits, and promote long-term sustainability. Therefore, researchers assume that the use of technology is influenced by both PEOU and PU. AI adoption studies have reported PU as a significant factor in determining the adoption of new technology. Such were the findings of Rahman et al., (2023) on their study of Adoption of AI in banking services. Their results showed that attitude towards AI significantly mediates the relationship between perceived usefulness and intention to adopt AI in banking services. In similar exercises, Saprikis et al., (2022), Oliveira et al., (2016) and Aggarwal and Rahul (2017) have connected similar technological advancements such as online banking and mobile banking adoption behaviour with perceived benefits of usage for the consumer.

In the context of digital banking and AI technologies, PU refers to the extent to which consumers believe that an artificial intelligence solution enhances the value of their banking experience or results to a problem being solved (Bilal et al., 2024; Fares et al., 2023) or leads to better financial management (Shankar & Datta, 2018). This study will follow previous scholars’ work and proceed with the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 (H2): The perceived usefulness influences Intention to Use in AI banking services

2.4. Performance Expectancy (PE)

Performance Expectancy (PE) is a term introduced by the UTAUT model and remains also in the advanced version. PE for banking technology is the belief that using a system will improve task performance (Venkatesh et al., 2012) and will help the user to attain gains in performing banking tasks (Martins et al., 2014). It includes performance improvements, efficiency gains, and overall effectiveness (Dwivedi et al., 2019). Actually, PE encompasses a broader range of performance-related expectations compared to PU, including expected performance improvements, efficiency gains, and overall effectiveness as opposed to PU, which is more narrowly focused on the perceived direct benefits of technology use (Dwivedi et al., 2019; Jaya Lakshmi et al., 2023). Studies like those of Martins et al., (2014), Rahi et al., (2019), emphasize that PE is a key determinant in the adoption of internet banking. Riffai et al., (2012), Rahi et al., (2019), Oliveira et al., (2016), Khalil et al., (2010), Martins et al., (2014) have confirmed that performance expectancy is the most influential factor in the adoption of internet banking. In the context of AI in banking, PE encompasses the perceived capacity of AI to improve decision-making and customer service (Bilal et al., 2024; Shen et al., 2019). PE is a well-researched and validated construct and is specifically designed to integrate elements from various existing models and its suitable for looking at a broader set of expectations regarding performance improvement due to technology use.

These findings resonate with the UTAUT-2 framework, which suggests that performance expectancy, alongside effort expectancy and social influence, can strongly correlate user engagement with technology (Venkatesh et al., 2012). Based on those inputs and on the results of previous related references, we will propose as hypothesis

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Expectation of the performance of AI in banking services influences Intention to Use in said technologies

2.5. Effort Expectancy (EE)

Effort Expectancy refers to the degree of ease associated with using a particular system or technology (Venkatesh et al., 2003). Measuring the perceived technological efficiency and effectiveness has been the interest of many, if not all, technology adoption studies from the early ones, such as Hendrickson et al., (1993), Workman (2007) to Liang et al., (2020), Edo et al., (2023), Kitsios et al., (2021), to name a few. In the context of AI adoption in banking, Effort Expectancy captures users’ perceptions of how simple and intuitive it is to interact with AI-driven platforms, such as virtual assistants or automated loan application systems (Oliveira et al., 2016). A user-friendly interface and seamless experience are critical factors for ensuring positive attitudes toward AI tools (Dwivedi et al., 2019). Previous studies, such as those by Venkatesh and Davis (2000), have established Effort Expectancy as a direct antecedent of behavioural intention to adopt new technologies. For AI systems in banking, minimizing perceived complexity can enhance acceptance, especially among less tech-savvy customers (Shankar & Datta, 2018). It is envisaged that, given that AI is a novice technology for the Greek public, there will be expectations about the input required vs the output that will be provided to the end users. Certain stakeholders may expect that a lot of effort will have to be placed in interacting with AI while others may consider it an easy task. This study, via SEM analysis, will explore the relationship between Effort Expectancy and technology adoption. Based on the above, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Effort Expectancy influences Intention to Use in AI banking services.

2.6. Social Influence (SI)

The term "Social Influence" describes the deliberate and inadvertent attempts made by others to modify a person's feelings, ideas, or actions (Riva et al., 2022). Individuals tend to follow the norm or subdue to peer pressure, especially when faced with an acknowledged level of expertise, respect or social recognition. Individuals frequently want to be a part of informed groups, and this affiliation drive can influence their views and actions (Chaouali et al., 2016; Edo et al., 2023). According to Rajak and Shaw (2021), decisions and preferences can be significantly influenced by peer evaluations and the opinions of well-respected individuals, especially when those opinions coincide with perceived usefulness and simplicity of use.

It was UTAUT model that recognised the importance of SI inclusion as a key construct for the study of user acceptance (Al-Mamary et al., 2016). Ever since, SI has been extensively studied in the context of various technologies, where the perceptions and attitudes of peers and influential groups have been shown to play a pivotal role in shaping individuals' technology adoption behaviours (Alkawsi et al., 2021; Venkatesh & Davis, 2000). And, as expected, studies have demonstrated that in environments where new technology is introduced, the influence of peers and important social contacts significantly affects individuals' behavioural intentions to use the technology, exerting social pressure on individual to adopt new technology (Taylor & Todd, 1995; Zhou (2013). In the specific context of AI, this study aims at evaluating social influence by examining users’ beliefs about the significance of AI, as informed by the opinions of their influential social contacts. Prior research has consistently indicated a positive relationship between social influence and the acceptance of new technologies.

Building on these insights, the current study proposes a hypothesis that seeks to empirically investigate the extent to which social influence, as a construct within technology adoption models, specifically affects the willingness of users to integrate AI into their banking interaction routines. This leads to:

Hypothesis 5 (H5): Social Influence influences Intention to Use in AI banking services.

2.7. Facilitating Conditions (FC)

Facilitating factors are "objective factors that make an act easy to do, including the availability of resources and support" (Venkatesh et al., 2003). Facilitating conditions have been shown to directly influence technology use, especially in complex interactions by influencing users' intentions and usage behaviours directly (T. Zhou et al., 2010). The construct has been acknowledged as part of the UTAUT2 model framework and has been pivotal in it. Facilitating factors in AI banking could include the availability of user support, the reliability of AI systems, and the infrastructure supporting digital banking platforms, which are crucial for technology adoption (Shin, 2009). Thus, the hypothesis is

Hypothesis 6 (H6): Facilitating factors such as skills and system access influence Intention to Use in AI banking services.

2.8. Hedonic Motivation (HM)

Pleasure is an emotional state reflecting positive affect or the enjoyment derived from a particular situation (Russell, 1980). Earlier studies have often regarded hedonic motivation (also referred to as perceived enjoyment, perceived fun, or perceived playfulness) as an independent predictor ((F. D. Davis et al.,, 1992; Pikkarainen et al.,, 2004). As defined by Venkatesh et al., (2012), p. 161, hedonic motivation is “the fun or pleasure derived from using a technology”, without any specific extra benefit. It has been shown to significantly predict user intention (S. A. Brown & Venkatesh, 2005). While some studies suggest that incorporating fun attributes could reduce service effectiveness (Nikghadam Hojjati & Reza Rabi, 2013), others emphasize its positive influence on adoption (Salimon et al., 2017; Suryanarayana et al., 2024). The anticipatory emotions regarding AI interactions are believed to enhance user pleasure (Bagozzi et al., 1999).

More detailed studies have shown that HM, which refers to the pleasure or enjoyment from using technology, is a significant predictor of intention to use (Brown & Venkatesh, 2005). As such, the second, advanced model of UTAUT included this particular factor in its framework (Venkatesh et al.,, 2012). Salimon et al., (2017), mention that scholars may have overlooked its potential mediating role in the adoption of digital technologies in banking and acknowledge that the importance of hedonism has been particularly recognized in addressing the frustration that often accompanies online activities. Chemingui and Ben Lallouna (2013), and Pikkarainen et al., (2004), express similar views. Digital technologies such as e- banking platforms and, potentially, artificial intelligence applications, provide the scope for fun by incorporating music, animations and gamification that can create an interactive and emotionally challenging environment for the user (Ndubisi & Sinti, 2006). Several studies on online banking have confirmed the positive relationship between HM, otherwise known as perceived enjoyment or fun and adoption of online banking (Chiu et al., 2014; Salimon et al., 2017). In AI banking, emotional expectations might encompass the anticipated feelings of satisfaction or frustration that users expect from interacting with AI banking services (Ismatullaev & Kim, 2024; Laros & Steenkamp, 2005). However, other studies suggest that incorporating fun attributes may not always be beneficial and could potentially confuse users, reducing the effectiveness of such services (Nikghadam Hojjati & Reza Rabi, 2013; Ndubisi & Sinti, 2006). Given therefore the high interest of the subject and a certain ambiguity as to whether hedonic motivation influences AI adaptation technology in the Greek banking, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 7 (H7): Pleasure derived from using AI-enabled banking services influences Intention to Use in said services.

2.9. Intention to Use (ItU)

Studies have shown that intention is the main factor in committing any behaviour (Uzir et al., 2023). Behavioural intention is "an indication of an individual's readiness to perform a given behaviour, and it is considered to be an immediate antecedent of behaviour" (Ajzen, 1991). Behavioural intention of Use in AI banking reflects the likelihood that customers will use AI services, influenced by factors such as perceived usefulness, ease of use, and trust (Venkatesh & Davis, 2000). Intention to use a technology is intricately linked to the perceived value, which in turn is closely related to trust (Chiu et al., 2014) and actually mediates the relationship between trust and actual usage (Ahmad et al., 2020). On the other hand, the refusal to use may be associated with factors such as cognitive overload, information overload, or, as Alshurafat et al., (2023) places it, technostress, which can negatively impact an individual's willingness to accept a new technology. According to TAM structure, ItU is a factor that is based on the antecedents of perceived ease of use and usefulness, with the two representing two sets of anchoring and adjustment factors mediating ItU (Aggarwal & Rahul, 2017; Ahmad et al., 2020). As per UTAUT structure, performance expectancy, effort expectancy and social influence are key determinants set to influence behavioural intention to use a technology. User distrust in AI systems may follow different routes, based on several human factors (e.g. education, experience, perception) and properties of the AI system (e.g. transparency, complexity, controllability) as Asan et al., (2020), note. ItU acts as a mediating variable, linking the perceptions and experiences of users with their eventual decisions to adopt new technologies (Nordhoff et al., 2020; Uzir et al., 2023). Prior studies indicate that ItU's role as a mediator is essential for understanding how various psychological constructs collectively drive AI adoption (Chiu et al., 2014; Ahmad et al., 2020).

This study examines how AI adoption behaviour is influenced by the relationship between ItU and the other hypotheses, acting as a mediator that channels the impact of psychological and situational factors into adoption decisions.

Hypothesis 8 (H8): Customers' intentions to use AI in banking is influenced by all other hypotheses

2.10. AI Adoption Behaviour (AB)

ItU acts as a mediating variable, linking the perceptions and experiences of users with their eventual decisions to adopt new technologies i.e. Adoption Behaviour (AB), (Nordhoff et al., 2020; Uzir et al., 2023). In AI banking, ItU connects constructs such as perceived quality, trust, and performance with AI AB (Choung et al., 2022). Prior studies indicate that ItU's role as a mediator is essential for understanding how various psychological constructs collectively drive AI adoption behaviour (Chiu et al., 2014; Ahmad et al., 2020). This study examines also how the relationship between ItU and other constructs influences AI adoption: AI adoption behaviour is influenced by the relationship between ItU and the other hypotheses, acting as a mediator that channels the impact of psychological and situational factors into adoption decisions.

Hypothesis 9 (H9): Adoption of AI by all stakeholders is related to all other hypotheses

2.11. Control Variables (CVs)

As per Carlson and Wu (2012), in a research design, a variable can fulfil three functions, the two most prevalent of which are that of an independent variable (IV) and a dependent variable (DV). It is assumed that the factors represented by the IVs "depend on" or impact the values of DVs. (Carlson & Wu, 2012). Control Variables represent the third function. They are commonly used to capture factors that are broadly defined as extraneous to the desired effect—sometimes referred to as “nuisance” variance (Carlson & Wu, 2012). In organizational literature, there is a general consensus that CV estimates should be interpreted with caution because it can be challenging to provide meaningful significance to the marginal effects of biassed control variables (Hünermund & Louw, 2023; Shiau et al., 2024) For our paper, we have chosen occupation, education, age, and gender as CVs. We anticipated that these CVs may moderate the relationships suggested in the hypotheses between Independent and Dependent Variables, affecting the extent to which AI in banking is adopted and perceived.

All research hypotheses of the proposed conceptual framework are summarised on

Table 1.

4. RESULTS

The results section gives an overview of the outcomes from using the SEM framework to test the proposed relationships between variables. This section covers the creation and testing of the measurement part of the model, followed by an evaluation of the structural model.

4.1. Data Analysis

As discussed, SEM was chosen as the optimum research analysis tool that is suitable for evaluating latent constructs i.e. variables that cannot be directly observed (Blanthorne et al., 2006). Models like TAM and UATAU-2 were developed to assess the determinants of intention, in other words, the independent variables (IV) but also the dependent variables (DV). Information about latent constructs is obtained indirectly by observing several indicators or variables affected by the latent construct. To place it differently, many constructs have direct effects on intention but affect behaviour/use only indirectly, through intention, (Blanthorne et al., 2006). Underlying attitude is believed to affect responses to certain questions regarding attitude rather than the responses shaping attitudes. Both of these suggest a mediating relationship between predictors and an outcome, and, SEM, a variance-based analysis is a potentially appropriate method of analysis for that (Azman Ong et al., 2023). PLS-SEM, that has been identified as the best method for measuring simultaneously external and internal(structural) models successively (Edo et al., 2023). PLS-ESM is also considered to be effective for smaller sample sizes of questionnaires and more complicated (Alkawsi et al., 2021; Edo et al., 2023).

4.2. Measurement model evaluation

The Measurement Model is a fundamental aspect of SEM that evaluates the relationship between latent variables and their observable indicators, ensuring the constructs’ reliability and validity before structural model analysis. In this study, the evaluation followed the rigorous standards outlined by Hair et al., (2021) and Henseler et al., (2009), which emphasize the importance of minimizing measurement errors to enhance the robustness of conclusions.

Prior to that though, a goodness-of-fit exercise was executed (

Table 4). Model goodness-of-fit (GoF) is a critical component in evaluating the validity of SEM, ensuring that the hypothesized model aligns with observed data It provides a global assessment that complements construct-specific metrics like reliability and validity (Hair

et al., 2021). Commonly used indices include absolute fit metrics (e.g., Chi-square statistic, RMSEA, SRMR), incremental fit indices (e.g., CFI, TLI, NFI), and parsimonious fit measures (e.g., χ²/df), each with recommended thresholds for interpretation (Yuan & Bentler, 2006). In this study, the χ²/df ratios of 1.461 (measurement model) and 1.408 (structural model), along with RMSEA values below 0.05 and high CFI/TLI values (above 0.90), indicate excellent fit and align with prior studies (Hair

et al., 2021; Martins

et al., 2014). These indices confirm that the constructs and relationships are well-represented, supporting the study’s theoretical framework based on TAM and UTAUT (Davis, 1986; Venkatesh

et al., 2003). The strong GoF metrics validate the hypothesized relationships and reinforce the robustness of findings related to AI adoption in banking, providing a reliable basis for actionable insights.

Following that, the study proceeded with measurement model evaluation (

Table 5). Key metrics included factor Loadings, Composite Reliability (CR), and Average Variance Extracted (AVE).

All constructs exceeded the recommended thresholds, with factor loadings above 0.60 (Gefen et al., 2003; Hair et al., 2018), CR values above 0.70 (Hair et al., 2021; Henseler et al., 2015), and AVE values over 0.50, demonstrating strong internal consistency and convergent validity.CR provides a nuanced assessment of internal consistency, surpassing Cronbach’s Alpha by accounting for varying factor loadings among indicators (Hair et al., 2021). All constructs in this study exceeded the CR threshold of 0.70, with Facilitating Conditions (CR = 0.925) and Adoption Behaviour (CR = 0.942) exhibiting exceptional reliability, aligning with studies by Venkatesh et al., (2012) and Sarstedt et al., (2021). AVE, measuring convergent validity, confirmed that most constructs adequately explained the variance in their indicators, surpassing the 0.50 threshold (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Adoption Behaviour achieved the highest AVE (0.845), indicating strong explanatory power, supported by high factor loadings such as AB2 (loading = 0.941). Facilitating Conditions also demonstrated robust validity (AVE = 0.756, FC4 loading = 0.895), emphasizing resource availability as a key adoption driver (Shin, 2009; Venkatesh et al., 2003). Constructs like Hedonic Motivation (CR = 0.773, AVE = 0.631) showed moderate performance, consistent with findings by Salimon et al., (2017) on the subjective nature of enjoyment constructs. All constructs achieved satisfactory CA values, with Facilitating Conditions reaching the highest value of 0.926, reflecting exceptional internal consistency (Henseler et al., 2015). Finally, Skewness and kurtosis assessments confirmed acceptable data distribution, with values falling between -1 and +1, who are generally considered acceptable for normality in SEM (Hair et al., 2021). Most indicators in this study fell within this range, with minor deviations that are typical in survey data, especially for Likert scales (Kline, 2018). Overall, the evaluation aligns with best practices in SEM (Hair et al., 2021; Henseler et al., 2015), offering a reliable foundation for analysing AI adoption behaviour in banking and underscoring the importance of refining constructs like Hedonic Motivation for greater consistency.

The Fornell-Larcker criterion confirmed the discriminant validity of all constructs in this study (

Table 6), reinforcing the reliability of the measurement model evaluation (Henseler

et al., 2015). The square root of the AVE for each construct exceeded its correlations with other constructs, demonstrating sufficient distinctiveness. Overall, the discriminant validity analysis confirmed the robustness and empirical distinctiveness of the constructs, minimizing multicollinearity and enhancing the accuracy of the structural model. These results validate the measurement model’s reliability and provide a solid foundation for understanding the factors influencing AI adoption in banking, aligning also with best practices in SEM (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Hair

et al., 2021).

In detail, FC exemplify this differentiation of constructs well, with a diagonal value of 0.869 significantly surpassing its highest correlation with EE at 0.400. This aligns with prior findings by Shin (2009) and Venkatesh et al., (2003), which emphasize the critical role of resource availability and system reliability in technology adoption. AB, with the highest diagonal value (0.919) and low correlations with constructs like ItU (0.143), underscores its empirical robustness and theoretical clarity as an outcome variable, consistent with studies like Martins et al., (2014). Similarly, PU demonstrates strong validity, with its diagonal value (0.879) exceeding correlations with PE (0.644), preserving their theoretical distinctions (Davis, 1986; Venkatesh et al., 2012). HM, while meeting the criterion, shows moderate correlations with PE (0.666) and EE (0.616), suggesting minor conceptual overlap typical of subjective constructs (Brown & Venkatesh, 2005).

4.3. Structural model evaluation and hypothesis testing

Structural model evaluation is a critical phase in SEM, focusing on the relationships among constructs and assessing the model's explanatory and predictive capabilities. Unlike the measurement model, which ensures the reliability and validity of individual constructs, the structural model examines how these constructs interact to test theoretical hypotheses. Our study confirmed several significant relationships between constructs, consistent with established technology adoption models like UTAUT2 (

Table 7). PE and EE exhibited the strongest path coefficients to ItU, underscoring their pivotal roles in shaping behavioural intentions. All other Constructs also confirmed their significance, with the notable exception of SI, who proved to be non-significant. Likewise, occupation and, to a lesser extent, education, were also deemed significant variables. These findings align with the UTAUT model (Venkatesh

et al., 2003) and echo Martins

et al., (2014), emphasizing that both the utility (PE) and usability (EE) of AI systems are crucial for adoption.

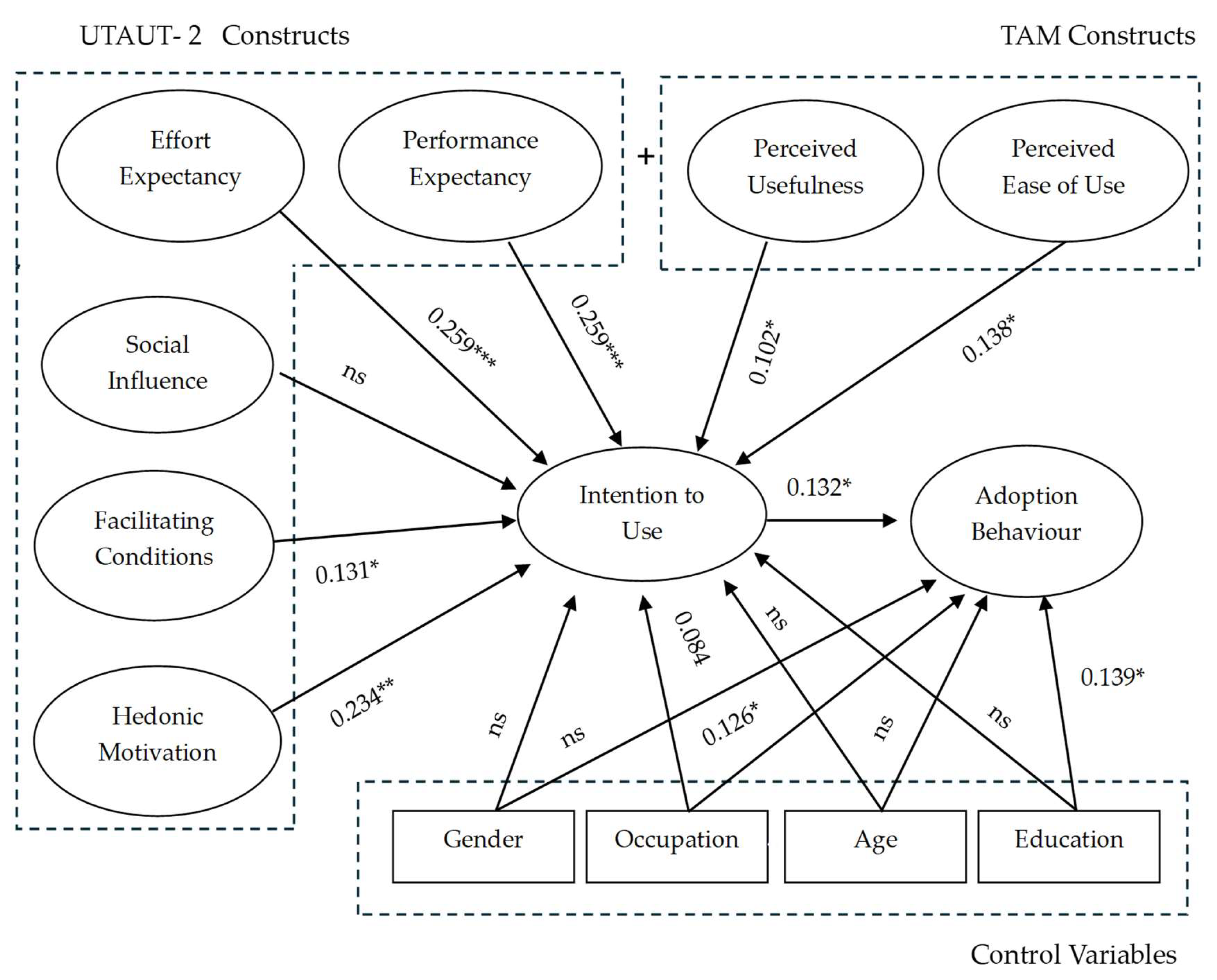

In particular, it was observed that H1, PEOU positively influences ItU (β path coefficient =0.138, p<0.05), aligning with research by Dwivedi et al., (2019) and Rahman et al., (2023), emphasizing simplicity in AI systems as a key factor in adoption, reinforcing also Davis’s (1986) TAM findings, where system simplicity and intuitive design support adoption, though more as a complementary driver. H2: Similarly, PU also impacts ItU (β=0.102, p<0.05), supporting studies by Kapoor et al., (2021) and Venkatesh et al., (2012), highlighting the perceived benefits of AI on job performance, improving convenience and decision-making. However, its moderate effect relative to PE and EE suggests that usefulness may gain greater influence post-adoption, as observed in Oliveira et al., (2016). H3: PE has the strongest influence on ItU (β=0.259, p<0.001), underscoring the importance of productivity improvements, as noted by Shiau et al., (2024). Likewise, H4: EE significantly predicts ItU (β=0.259, p<0.001), suggesting that ease of learning AI systems encourages adoption, resonating with findings by Hoque and Sorwar (2017). In contrast, H5: SI was not a significant predictor, indicating that Greek stakeholders rely more on personal assessments rather than peer influence, diverging from studies like Zhou (2013). H6: FC positively affect ItU (β=0.131, p<0.05), consistent with Venkatesh et al., (2016), highlighting the role of infrastructure and support systems in adoption. This supports the critical importance of infrastructure, support mechanisms, and system reliability in ensuring successful adoption. These findings align with Venkatesh et al., (2003) and Rahman et al., (2023), emphasizing the role of resources, knowledge, and support in bridging intention and actual usage. H7: HM also significantly influences ItU (β=0.234, p<0.01), aligning with K. Gupta and Arora (2020), indicating that enjoyment can drive adoption, especially among younger users, underscoring the role of enjoyment and satisfaction in adoption behaviour. These results also align with Brown and Venkatesh (2005), highlighting the growing importance of hedonic factors, particularly in enhancing user engagement and satisfaction. Lastly, H8: ItU significantly predicts AB (β=0.132, p<0.05), reaffirming the UTAUT2 premise that intention precedes actual adoption behaviour (Venkatesh et al., 2016). The model confirms ItU as a critical mediator, significantly predicting Adoption Behaviour (path coefficient = 0.132, p < 0.05). This centrality reflects its role in translating user perceptions into actionable outcomes, consistent with Chiu et al., (2014).

The control variables offer nuanced insights (Shiau et al., 2024). Occupation (OCC) significantly influences both Intention to Use (path coefficient = 0.084, p < 0.05) and Adoption Behaviour (path coefficient = 0.126, p < 0.05), indicating the role of professional context in shaping perceptions and adoption (Batiz-Lazo et al., 2022). Education (EDU) also significantly impacts Adoption Behaviour (path coefficient = 0.139, p < 0.05), with higher educational attainment linked to greater adoption. These findings align with Carlson and Wu (2012), reinforcing the importance of education in technology adoption. Conversely, demographic variables like Gender (GEN) and Age (AGE) show no significant effects, suggesting relatively uniform perceptions across these groups contrary e.g. to Faqih (2016) who found some relevance on Gender.

A visual representation of the Structural Model is depicted below,

Figure 2

5. DISCUSSION AND LIMITATIONS

Although AI adoption in banking has become a strategic priority, it remains far from having widespread implementation (Kaushik & Sharma, 2023). Successful adoption depends on users' willingness to embrace the technology, as highlighted in the foundational work of Davis (1986) and further expanded by Davis and Venkatesh (1996). This study investigates behavioural impediments to AI adoption among stakeholders of Greek incumbent banks, including bank employees, the general public, and digital professionals. It addresses three key research questions: Which factors influence AI adoption positively or negatively? How strong are these influences, and are there moderating variables? Are there differences in AI acceptance among stakeholder groups? Drawing from TAM and UTAUT-2 models, the study tested nine hypotheses. Eight were confirmed as significant predictors of adoption intentions. PE, EE and HM emerged as strong predictors of adoption intention, while PEOU, PU and FC significantly influenced ItU, which itself predicted AI AB. SI, however, was non-significant, indicating that AI adoption decisions are increasingly seen as personal rather than socially influenced, aligning with findings by Morosan and DeFranco (2016).

The findings revealed that while facilitating conditions, such as access to hardware, were sufficient, gaps in knowledge and skills underscored the importance of usability and intuitive design for fostering adoption (Fares et al., 2023; Gefen et al., 2003). Adoption intentions were consistently high across societal and occupational groups, reflecting a shared anticipation of AI integration. However, some differences emerged among occupational and educational groups, with fintech professionals and postgraduate respondents showing higher likelihoods of adoption, consistent with Hair et al., (2021) and Dwivedi et al., (2019). Demographic variables such as gender and age were not significant moderators, challenging prior research by Faqih (2016) that suggested gender-related differences. Interestingly, no substantial generational divides were observed, as younger respondents and those over 45 demonstrated similar acceptance levels. This supports Shiau et al., (2024), who found that familiarity and professional exposure to AI, rather than age, drive adoption behaviours. These findings emphasize the importance of professional roles and education while challenging traditional assumptions about the demographic influences on technology adoption.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

The study's theoretical contribution is multifaceted. It provides new insights into AI adoption within Greece, a context that remains under-researched, while confirming key interactions between variables. The contribution of the exercise lies on the fact that it explores an area of great interest but even more so, having used control variables on population samples that match key stakeholders of the new technology to be introduced. The framework is adaptable for future research across sectors such as retail or public Institutions and enables the exploration of additional factors influencing behavioural intention.

The findings underscore a positive perception of AI in banking, with participants associating it with convenience, speed, and efficiency, echoing previous research on AI's transformative impact (Chauhan et al., 2022; Janssen et al., 2020). Drawing on TAM and UTAUT-2 frameworks, the study validates constructs such as PE (Dwivedi et al., 2019; Martins et al., 2014), EE (Oliveira et al., 2016; Shankar & Datta, 2018), and HM (Brown & Venkatesh, 2005) as significant for Intention to Use AI. FC, as per previous findings, (Alnemer, 2022; Shin, 2009; Venkatesh et al., 2016) were also found pivotal in shaping stakeholders' ItU and AB, while SI showed no effect, challenging findings of scholars like Zhou (2011). The study further identifies OCC and EDU as significant variables for ItU and AB. The findings may signify conservative attitudes among bank employees, reflecting anxiety about job security and a preference for human interaction, contrasting with the enthusiasm of fintech professionals (Bessen, 2019), thereby offering nuanced insights into stakeholder differences.

5.2. Managerial and Practical Implications

The practical objective is to guide Greek systemic banking institutions in integrating AI into their operations and to support technology designers in enhancing the adoption rates among consumers by providing some useful insides some positive implications and some clear caveats. As Edo et al., (2023), note in their similar study on healthcare, Technology does not exist in isolation, and its mere availability does not guarantee adoption. Instead, it relies on the acceptance and collaboration of key users or process owners, such as clients, employees, and professionals, to realize its full potential

The study provides a positive outlook on AI adoption in everyday banking across demographics, highlighting practical benefits such as improved performance and reduced effort, while setting aside older perceptions shaped by social stereotypes. Greek bank users generally view AI favourably, recognizing its benefits and usefulness. However, the introduction of AI may face scepticism from both staff and the general public, emphasizing the need for effective change management and transparent communication to address concerns and ensure a smooth transition to these innovative technologies. These findings underscore the importance of tailored strategies to address the diverse needs and perceptions of various demographic and professional groups. By focusing on usability, transparency, and emotional engagement, Greek banks can establish a strong foundation for AI integration, aligning with global digital transformation trends (Ismatullaev & Kim, 2024; Turilli & Floridi, 2009). Addressing these specific needs will encourage broader and more sustainable adoption of AI technologies, fostering a successful transition to advanced banking solutions.

5.3. Research limitations and Scope for Future research

The work done here has the limitations of contemporary frameworks. The findings of the paper are only applicable within the current time context. As AI technology matures further, along with each market that it introduced to, both as a public sphere item and in its practical implementation in banking, perceptions and attitudes will be altering. Further work should be done to confirm or challenge research outcomes. There is a number of questions that were provoked by the exercise, and we believe that extension of research to these areas, would help advance the relevant knowledge field:

Is the survey design adequate or fit for the purpose? Would a different methodology and approach (e.g., focus groups or interviews) reveal a different outcome?

Would different control variables such as e.g., income, geographical location, bank branch frequency of visits, banking work transaction type, mix of human and AI, result to a different outcome?

Are the findings applicable to different audiences? What is the perception and viewpoint of other key stakeholders such as regulators, shareholders and bank executives in moving up the pace of transition from current state to fuller adaption? Is there an impediment, are there conflicting interests perceived?

Furthermore, it should be mentioned that the questionnaire exercise itself had limitations and eventually included only the respondents who were willing to respond fully to the questionnaire.