1. Introduction

Reasoning is a trait that distinguishes humans from other living beings, encompassing the ability to think, comprehend, analyze, and make decisions based on information and experience. It is a personal, conscious, and active process that relies on logical mechanisms to interpret data and identify solutions to problems [

1,

2,

3]. Clinical reasoning is a complex cognitive process that is essential for evaluating and managing individuals’ health. In the emergency department context, this skill is crucial for nursing professionals to make accurate and informed clinical decisions. Such reasoning is indispensable to ensuring the quality of care provided. Clinical reasoning among nurses is particularly important for assessing patients’ clinical conditions, identifying health problems, and making accurate and swift decisions regarding care. Ensuring safety in clinical assessments, health problem identification, and assertive decision-making are fundamental responsibilities for nurses, requiring education and training. Working in emergency services, where patients are often critically ill and conditions can change rapidly, places considerable pressure on these professionals. Nurses must make quick decisions when patients are in critical situations [

4,

5,

6]. This dynamic environment increases the risk of burnout and heightens nurses’ vulnerability in decision-making. Emergency interventions often demand decisions within limited time frames, sometimes without the opportunity for reflection. Moreover, clinical reasoning has increasingly been recognized as a fundamental criterion for being acknowledged as a competent nurse [

7,

8,

9].

Effective reasoning enables the prediction of problems, anticipation of complications, and early action in high-severity situations. The reasoning process includes components such as assessment, diagnosis, decision-making, intervention, and outcome evaluation. In this sense, clinical reasoning is at the heart of nursing competencies, playing a crucial role in accurate diagnoses and decision-making [

1,

6,

8,

10]. To ensure safe and effective care, nurses must analyze a wide range of information and use their experience to address the complex challenges of clinical practice.

This process ensures patient safety and promotes positive health outcomes. Several authors [

1,

8,

11], describe clinical reasoning as the ability to guide actions based on knowledge and experience, realized through problem-solving, decision-making, planning, and justifying interventions. Clinical experience, critical thinking, a broad knowledge base, and the ability to integrate evidence-based practices are among the numerous skills necessary to support decision-making processes [

6,

12]. Furthermore, nurses’ proximity to and relationships with patients enhance their ability to evaluate and tailor their decisions [

10,

13]. In healthcare delivery, it is vital that nurses possess firm clinical decision-making skills and are appropriately valued and recognized for this responsibility. Such professional recognition hinges heavily on nurses’ ability to accurately describe how they solve patients’ problems. Today, nursing work has become more critical than ever in this era of advancing healthcare.

Progress in health and the profession itself has brought nurses new, more complex challenges and responsibilities, legitimizing their recognition within healthcare institutions and societies. There is growing investment in developing clinical reasoning, both as a subject of scientific research for creating explanatory models and as a clinical practice for optimizing patient care. In clinical practice, this has been achieved through training strategies like clinical simulation [

14,

15,

16], which aim to refine this essential competence. From a research perspective, clinical reasoning has been explored using both deductive and inductive approaches, offering a comprehensive understanding of the subject. Patricia Benner, a key figure in this area, developed a line of research theorizing how nurses make decisions and how this decision-making capacity evolves [

7,

8]. She pioneered the concept of “clinical judgment among nurses” in nursing, now recognized as a fundamental competency in clinical practice. Clinical judgment refers to the ability to make deliberate and competent decisions [

8,

17].

However, there remains a need to deepen knowledge about clinical reasoning to improve education, training, and clinical practice. Continued understanding of clinical reasoning is essential to minimize errors and adverse events in healthcare. This is one of the significant challenges related to clinical reasoning processes, particularly among newly graduated nurses [

8,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22].

Studies by Aiken et al. [

23] found that nurses with higher academic qualifications achieve better patient outcomes. A study published in BMC Medical Education defines clinical reasoning in nursing as a cognitive process involving strategies to understand information, identify patient problems, and make decisions for patient care. The study emphasizes that nurses’ clinical reasoning skills are crucial for accurate patient assessments and effective interventions [

24]. Furthermore, a publication in BMC Nursing discusses the development of a clinical reasoning competency scale for nurses, underscoring the importance of clinical reasoning in nursing education. The article notes that a lack of clinical reasoning can lead to incorrect decisions and potential harm to patients, highlighting the need for structured training in this area [

25].

Additionally, the management of health incidents in the public health system of New South Wales [

26] identified three main causes of adverse patient outcomes: diagnostic errors, treatment implementation failures, and inadequate complication management. These findings reinforce the importance of investing in clinical reasoning research, particularly in emergency nursing, where rapid and precise decisions are critical for patient safety. In summary, clinical reasoning is integral to nursing practice, directly influencing patient outcomes and safety. Ongoing education and assessment of clinical reasoning skills are essential to ensure high-quality patient care.

This research aligns with the purpose to analyze the clinical reasoning process of nurses and develop a theory that explains this process in the emergency department. The primary motivation for conducting this study was the lack of a comprehensive theory capturing the clinical reasoning process nurses employ when interacting with patients in emergency settings. Additionally, the research was driven by the need to provide a conceptual understanding of the components underlying this reasoning process.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting

The present study was conducted in a central, multidisciplinary public hospital in the Lisbon area, Portugal, over a period of six months. It took place in an emergency department that provides care to a high number of patients daily. This setting allows nurses to develop assessment and intervention skills in multiple clinical cases involving critically ill individuals, while also enabling the researcher to frequently observe the clinical reasoning process in a dynamic and challenging environment.

2.2. Study Design

This is a qualitative study employed Grounded Theory (GT) procedures for data analysis, enabling a systematic and rigorous approach. The application of the Grounded Theory (GT) method proved to be a unique opportunity to deeply explore the root of the problem, providing a more comprehensive and detailed understanding of the clinical reasoning process of nurses working in emergency services.

2.3. Rigor and Reflexivity

A reflective journal was maintained throughout the study, where personal assumptions and insights were recorded and consistently compared with the emerging subcategories. Actions and experiences were analysed from multiple perspectives, adopting a critical stance toward the researchers’ own actions and beliefs. To ensure a reflexive approach, efforts were made to set aside preconceived notions and reflect on the interpretation of interview data before and after each session. This process allowed for a comparison between the researchers’ interpretations and those of the participants, fostering a search for alternative interpretations. These steps were always conducted with the research question and study objectives in mind, ensuring alignment and rigor in the analysis process.

2.4. Theoretical Framework

The application of the Grounded Theory (GT) method provided a unique opportunity to explore the root of the problem and gain a deeper understanding of the clinical reasoning process of nurses working in emergency departments. Grounded Theory adopts the perspective of symbolic interactionism, which views individuals as participants in a continuous problem-solving process where meanings are derived and transformed through interactions. Symbolic interactionism emphasizes the importance of interpersonal relationships within the social context and highlights the conditions that influence these interactions. A distinctive feature of Grounded Theory is its dual capacity to provide meaning, understanding, and description of the phenomenon under study while also facilitating theory generation [

27]. This approach offers researchers traceable evidence to support their generalizations. According to Charmaz [

27], Grounded Theory is particularly advantageous because it systematically focuses on analyzing processes through a conceptual lens, interpreting empirical observations to construct a theory. To answer the research question:

“How does the clinical reasoning process of nurses working in the emergency department develop?”, we adopted a set of methodological decisions that allowed us to achieve a detailed understanding of the Nurses’ Clinical Reasoning Process in emergency settings. The study was conducted using a qualitative, inductive approach based on GT as proposed by Charmaz [

27]. The application of the GT method enabled us to investigate the roots of the phenomenon and gain an in-depth understanding of the process’s nurses use to recognize the severity of clinical situations in the emergency department. GT has a unique characteristic that distinguishes it from other qualitative research methods: it not only provides meaning, understanding, and description of the phenomenon but also enables theory generation [

27,

28]. Charmaz [

27] argues that GT stands out for its methodical focus on process analysis through a conceptual approach, which interprets empirical observations to construct a theory. As an inductive process, Grounded Theory allows for the creation of theory from a specific starting point, revealing processes that are not immediately observable. The research was conducted within the context where the phenomenon occurs, allowing explanations of facts and phenomena to emerge through observation and interaction. We chose Charmaz [

27], Grounded Theory approach for several fundamental reasons: I) The simultaneous collection and analysis of data; II) The analytical construction of codes and categories from data rather than preconceived hypotheses; III) The use of the constant comparative method at all stages of analysis; IV) The development of theory at each stage of data collection and analysis; V) The importance of memo-writing to refine categories, specify their properties, and clarify relationships among them, VI) Theoretical sampling, aimed at building theory rather than representativeness. The phases of this process are cyclical, requiring interconnected steps. It is essential to note that theoretical saturation arises from multiple stages, where various cycles occur in a spiral, becoming increasingly complex as the theory develops. The use of multiple data sources (interviews, participant observation, and field notes) allowed for data triangulation, which was critical in identifying gaps, discrepancies in the data, or contradictions that reflect unique ways of thinking and acting. This methodological structure proved most appropriate for studying nurses’ clinical reasoning in their natural context, enabling the construction of concepts, categories, and subcategories.

2.5. Participants

The selection of participants followed these criteria: they must be expert nurses in the emergency department, considering reference authors in this field [

17,

29]; have at least 5 years of professional experience in the service; work across all sectors of the department; and be available (volunteers) and motivated to participate in the study. A total of 20 nurses participated in study, all voluntarily and with informed consent, being fully briefed on the study’s details. For data collection, in-depth interviews [

30,

31], participant observation (Streubert & Carpenter, 2011), and field notes [

32] were conducted with the 20 nurses working in an emergency department. The researcher collected data over a period of 6 months. The chosen emergency department was a central, multipurpose, public hospital that serves many people daily.

2.6. Sampling

Theoretical sampling was identified after the eighth interview. However, data collection continued to further develop the emerging theory, with 12 additional interviews conducted to validate the subcategories that had emerged from earlier interviews, even though these subsequent interviews did not yield new results. Despite confirming theoretical sampling after the eighth interview, continuous efforts were made to elaborate and refine the emerging codes and concepts. Completing the theoretical sampling process was crucial for refining concepts, generating subcategories, and developing properties and relationships for these subcategories. In-depth interviews served as the primary source of data. These interviews lasted between 30 and 60 minutes.

2.7. Data Collection Techniques

- ▪

In-Depth Interviews

The in-depth interview method [

31,

33] was chosen for this study to explore participants’ behaviors, beliefs, experiences, interactions, and ideas in their daily practice. This approach captured the phenomenon through the language and perspectives of those who experienced it firsthand. All interviews were conducted in a carefully selected location—a quiet, isolated room free from interruptions. This ensured a safe, calm, and comfortable environment for participants. In addition to interviews, participant observation and field notes were employed to enrich and cross-validate the collected data, allowing for triangulation and optimizing the in-depth interview process. The interviews followed a specific framework, where participants were prompted to:

“Recall a clinical case you recently experienced and describe the events in detail.”

They were also asked questions such as:

- What did you think?

- How did you think?

- What decisions did you make, and how?

- What was the most challenging aspect?

The interviews underwent continuous analysis through a back-and-forth process until theoretical saturation was achieved. This dynamic approach provided a deeper understanding of the data and ensured that all relevant aspects were incorporated into the theory construction.

- ▪

Participant Observation

Participant observation [

32] had two main focuses:

- I)

General observation of clinical reasoning among nurses: This involved observing multiple nurses simultaneously in a specific sector of the emergency department. Interactions between nurses and patients were recorded, focusing on clinical reasoning processes. The researcher accompanied different nurses during their shifts, taking notes on these interventions.

- II)

Individualized observation of a single participant: At specific moments and in defined contexts, the researcher observed one nurse interacting with a patient during care delivery. The goal was to document the nurse’s actions and the reasoning behind decisions, such as the questions asked, the use of technology for assessments, and consultation of medical records or patient charts.

These dual approaches enabled effective comparison between data from in-depth interviews and observations. Observations were recorded in descriptive notes, including details such as date, context, individuals involved, interventions, and timing.

- ▪

Field Notes and Memos

Field notes [

32] captured behaviours and emotions during specific interactions and were recorded similarly to observation notes. Memos [

27] were also essential for adding nuanced details, helping to cross-validate interview and observation data. These memos documented specific behaviours and emotions during interactions between participants and patients.

In this way, participant observation, field notes, and memos were instrumental in triangulating data, enhancing the insights gained from in-depth interviews.

2.8. Data analysis

The analysis began with line-by-line coding, where each line of data was labeled. This method served as a heuristic tool, helping the researchers critically examine the data while maintaining active engagement in the conceptualization process. The transcription analysis focused on participants’ ability to develop logical arguments, ensuring that no relevant details were overlooked. Additionally, attention was given to identifying inconsistencies and ambiguities in participants’ thought processes to detect reasoning problems and biases (cognitive errors).

Steps in the analysis:

Identifying Indicators and Grouping into Concepts, indicators were sought in the data and coded, forming clusters around recurring patterns. These were refined into concepts and later into subcategories. Each subcategory was consistently cross-checked with the original data to ensure a solid connection to participants’ experiences.

Iterative Coding and Question Development, the team continued line-by-line coding until identifying codes that warranted deeper exploration. These codes informed questions that guided further data construction and analysis.

Collaborative Analysis, researchers debated the coding and analysis to enhance the richness and comprehensiveness of the findings. Emerging concepts and subcategories shaped additional data collection and theoretical sampling.

Conceptualization and Saturation, data were analyzed early and refined throughout subsequent stages, leading to concepts and subcategories. Properties were identified in the data until the concepts were verified and saturated. Subcategories grouped indicators under a central idea, representing the underlying pattern until no new properties emerged, achieving theoretical saturation.

Defining and Verifying Relationships, as data emerged, relationships between subcategories were defined, verified, and explained, along with variations within and between them. This process elevated the data to a conceptual level.

Role of Memos, memo writing played a critical role, aiding in conceptualizing data and developing properties for each category. These properties provided operational definitions, ensuring that the data were conceptually dense and capable of explaining the identified patterns. Once no new properties emerged, saturation was reached, resulting in a comprehensive and detailed explanation of the identified patterns.

2.9. Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was granted for this study by the University Ethics Committee and the Hospital Ethics Committee (CH/CE/10-02-2018). All participants, who were clear about the role and background of the interviewer, provided written informed consent before the interviews were undertaken and were told that they could withdraw from the study at any time. All data were stored electronically on a password protected computer. Primary ethical concerns focused on securing informed participant consent and maintaining the confidentiality of both participants and their institutions. Participants could opt to receive the results.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

Initially, the demographic and clinical characteristics of the 20 study participants are presented, including age, gender, professional experience, and experience in the emergency service (

Table 1).

The data analysis revealed the central emerging category: Clinical Reasoning. This term was frequently mentioned by participants during the initial interviews, making it a central concept that guided the subsequent analysis. From this central concept, two subcategories emerged: Diagnostic Assessment and Nursing Therapeutic Intervention.

3.2. Clinical Reasoning as a Central Concept

Clinical Reasoning is understood as a cognitive process that begins from the nurse’s initial contact with the patient. This process involves collecting, analyzing, and processing information, which includes decision-making and culminates in action—specifically, nursing intervention. The effectiveness of these interventions depends directly on the nurse’s ability to: Gather relevant data, distinguish critical information from non-essential details and make appropriate decisions. These ideas of Clinical Reasoning, Diagnostic Assessment, and Therapeutic Intervention also align with findings in studies by Tanner [

12], Lopes [

34], Sapeta [

35] conducted in other nursing care contexts.

3.2.1. Nurses’ Clinical Reasoning Process

Subcategory: 1st Diagnostic Assessment, this represents the first stage of the clinical reasoning process and has two core conceptual properties: Life Risk (Level I): Prioritizing interventions for patients with life-threatening conditions and Expressed Problems (Level II): Addressing the patient’s explicitly identified issues. The Diagnostic Assessment involves systematically, dynamically, and continuously evaluating the clinical severity of a patient. This process is based on: alert symptoms, help needs and patient-reported experiences. Key elements of the Diagnostic Assessment process: the nurse uses multiple tools and strategies to collect data, identify priorities, and define appropriate nursing interventions; the evaluation evolves over time, increasing in complexity and alignment with the patient’s specific clinical situation and constant monitoring is vital to detect any changes in the patient’s condition and refine assessments accordingly. The nurses address critical questions to guide the assessment: “Is the patient breathing?”, “Does the patient have a pulse?”, “Can the patient speak?”, “What are the signs and symptoms?”, “Are there pre-existing problems?”, “Are there visible or hidden injuries?”, “What are the disabilities or limitations?”, “What are the patient’s concerns or emotional needs?”, “What is the family’s role and level of support?”, “What resources are available?”. The answers to these questions, derived from observation, interviews, and systematic patient evaluation, contribute to defining the nursing diagnosis in the emergency department.

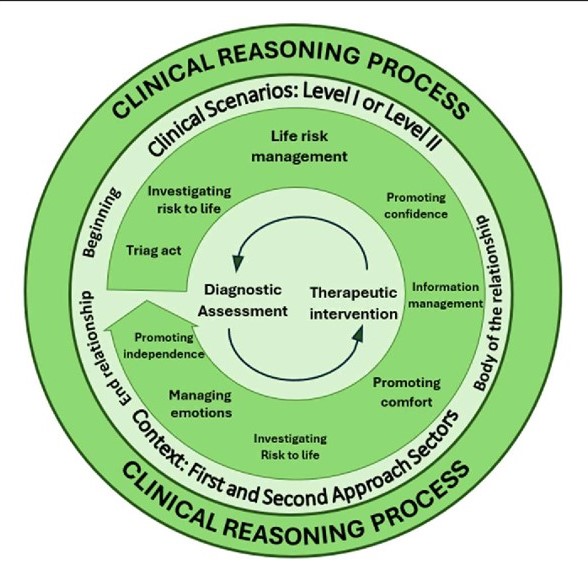

Another emerging aspect was the specificity of the

Diagnostic Assessment depending on the emergency sector in which the nurse operates. Nurses identified two types of sectors: First-approach sectors, these include triage and emergency rooms. In these sectors, the nurse’s objective is to perform a quick assessment to understand the patient’s clinical situation and identify the severity level and second-Approach Sectors, these involve observation areas and outpatient desks. Here, the focus shifts to more in-depth evaluations aimed at refining the Diagnostic Assessment. These sectors differ in terms of nursing goals and priorities. In first-approach areas, the priority is speed and initial classification, while in second-approach areas, the nurse performs a more detailed and ongoing analysis to adapt interventions effectively. The

Figure 1 illustrates the Diagnostic Assessment Process in the emergency department, highlighting the components involved and the distinctions between these two types of sectors. This differentiation reflects the dynamic and tailored approach nurses adopt depending on the urgency and context of care delivery.

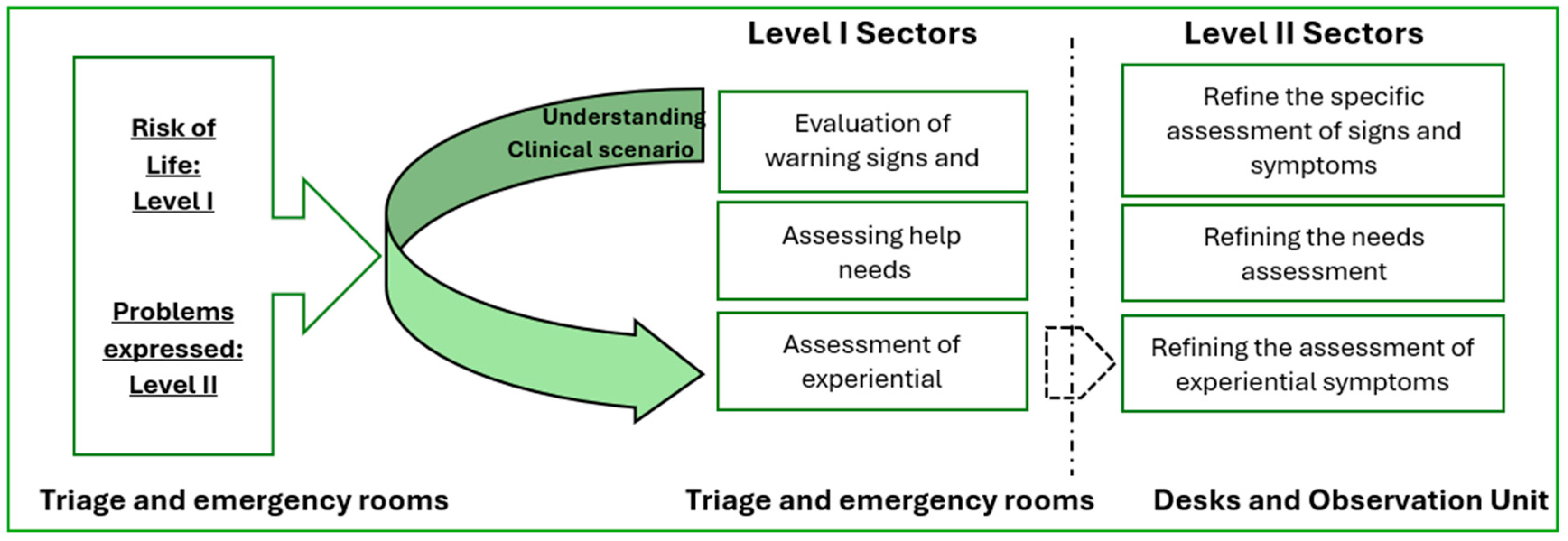

Subcategory: 2nd Clinical Reasoning is the Nursing Therapeutic Intervention. Like the Diagnostic Assessment, it is based on two conceptual properties: Life Risk (Level I) and Expressed Problems of the Person (Level II). The nurses’ accounts during the interviews highlight the importance of discerning whether the patient is at risk of life or not, as this determines the priority of intervention to manage situations where the patient’s life is indeed at risk. The Nursing Therapeutic Intervention is structured around several key aspects:

Management of Life Risk: Nurses closely monitor respiratory, cardiac, and neurological functions, establishing priorities based on the level of risk. Continuous assessment allows for immediate intervention when the patient’s life is in danger.

Time Management: Nurses must predict and anticipate problems, adjusting the timing to meet the patient’s needs. This skill is crucial for the effectiveness of the intervention.

Information Management: Informing the patient and family about the care provided, procedures, and addressing questions is a fundamental part of the intervention. Transparent communication helps engage the patient and family in the care process.

Promotion of Comfort and Trust: Creating an environment that promotes comfort and trust is essential in emergency care nursing. This includes symptom management, ensuring privacy, and the presence of family. Nurses also provide comfort in other ways, such as blankets, adjusting lighting, and controlling noise. Additionally, fostering trust is vital by showing a genuine interest in the patient and their family.

Management of Emotions: Understanding the emotions expressed by the patient is crucial, especially in health crises. Nurses help patients rationalize their emotions, thereby reducing suffering and enabling them to adapt to the new reality.

Promotion of Autonomy: This concept centers on the patient’s autonomy in the clinical decision-making process, directly related to their health literacy and their ability to recognize the limits of their own decisions. Nurses focus on promoting autonomy in the emergency service, aiming to equip patients to actively participate in the health-illness process by providing tools and information necessary for making informed decisions about their health. By integrating health literacy with the patient’s decision-making ability, nurses aim to maximize their independence, both within the emergency service and for discharge or potential hospitalization, ensuring the patient is as prepared as possible to manage their health autonomously.

3.3. Nature of Nursing Therapeutic Intervention

The concept of Nursing Therapeutic Intervention was identified as a practice organized around the management of life risk, information, time, emotions, and the promotion of comfort, as well as the autonomy of the patient and their family. This intervention is complex, as it involves various variables, including multiple actors, different sectors of the service, and an expanded physical structure. Interactions between these actors often occur simultaneously, requiring coordination between technical-instrumental and relational elements, usually within a short time frame. This complexity makes the intervention a process that develops over time in a dynamic and systematic manner. It is context-dependent and shaped by its specific characteristics. Essentially, the intervention carried out by nurses is therapeutic, as it brings tangible benefits to the health and well-being of patients and their families.

Figure 2 illustrates the Nursing Therapeutic Intervention in the Emergency Service, highlighting the types of interventions and the actors involved.

3.4. Clinical Reasoning Process of Nurses

Thus, the Clinical Reasoning Process of Nurses in the emergency department is a multidimensional process that combines assessment and intervention, considering both the immediate clinical status of the person and their abilities and personal strategies for coping with the health situation. This maximizes the chances of an appropriate and efficient therapeutic response from the nurses working there. This process is a cognitive and decision-making mechanism that nurses use to assess, interpret, and make quick and precise decisions in caring for patients in critical situations. This process is essential for identifying the severity of patients’ conditions and deciding which interventions should be implemented effectively, in a timely and useful manner.

4. Discussion

We believe this is the first study to thoroughly detail how nurses develop their clinical reasoning process to care for critically ill patients in a central emergency department. This environment is characterized by intense demands and the necessity for rapid responses, imposing extremely tight time constraints on interventions. Consequently, nurses are required to possess not only a high level of expertise but also an extensive and in-depth knowledge base in technical and scientific domains [

4,

25].

Effective management of clinical cases emerges as a fundamental pillar in this context, enabling the reduction of life-threatening risks and the prevention of complications. Moreover, proper management of information and time is essential to ensure that clinical reasoning is both efficient and tailored to the specific needs of each situation. Our findings emphasize that key elements such as data collection, careful observation of the patient, and the establishment of a high-quality therapeutic relationship are crucial components in shaping clinical reasoning and directly contribute to making rapid, safe, and evidence-based decisions.

In the context of emergency care, the Clinical Reasoning Process of Nurses consists of two main components:

Diagnostic Assessment Process: This enables the nurse to perform a quick initial analysis to determine whether there is a life-threatening risk or not. This initial assessment is crucial as it defines the priority and urgency of the intervention. To carry out this assessment, the nurse collects data, evaluating signs and symptoms, the patient’s general health status, history, and other relevant information [

6,

12]. The nurse systematically carries out continuous re-evaluation to monitor the evolution of the patient’s condition, adjusting their assessment and intervention accordingly. This is a dynamic feature of clinical reasoning, requiring flexibility and adaptation to rapid changes in the clinical condition, as the emergency department deals with patients facing highly complex and unpredictable clinical situations.

Nursing Therapeutic Intervention Process: This corresponds to the nurse’s actions based on their assessment and re-evaluation. In the emergency department, the nurse provides an active and immediate response based on the prior diagnostic assessment. This process is focused on managing the immediate life risk and ensuring adequate and humane care for the patient. After identifying problems such as respiratory, cardiac, or neurological complications, the therapeutic intervention focuses on quick and precise actions to stabilize the patient. In the emergency department, where every second counts, nurses constantly face high-pressure situations, requiring excellent time management to prioritize critical interventions to save lives. However, Nursing Therapeutic Intervention Process is not only about treating acute clinical conditions [

34,

35]. Communication and information are also essential parts of the process [

36]. Nurses need to provide information to the patient and their family about ongoing procedures, the patient’s status, and the next steps to be taken. This not only facilitates the patient’s autonomy in care but also promotes trust and safety in an environment often marked by fear and uncertainty. In this sense, nurses play an important role in managing the patient’s and family’s emotions, helping them cope with the emotional impact of a health emergency. Thus, Nursing Therapeutic Intervention Process goes beyond the application of techniques and procedures; it is a complex and comprehensive process that involves technical management, time, communication, comfort, and emotions, ensuring the patient receives the best possible care, both physically and emotionally, in an emergency context.

In the emergency department, where every second counts, the Clinical Reasoning Process of Nurses enables nurses to make quick, informed, and secure decisions, combining clinical knowledge, experience, and real-time observations [

4]. The approach is systematic but flexible enough to adjust to the constant changes in the patient’s condition.

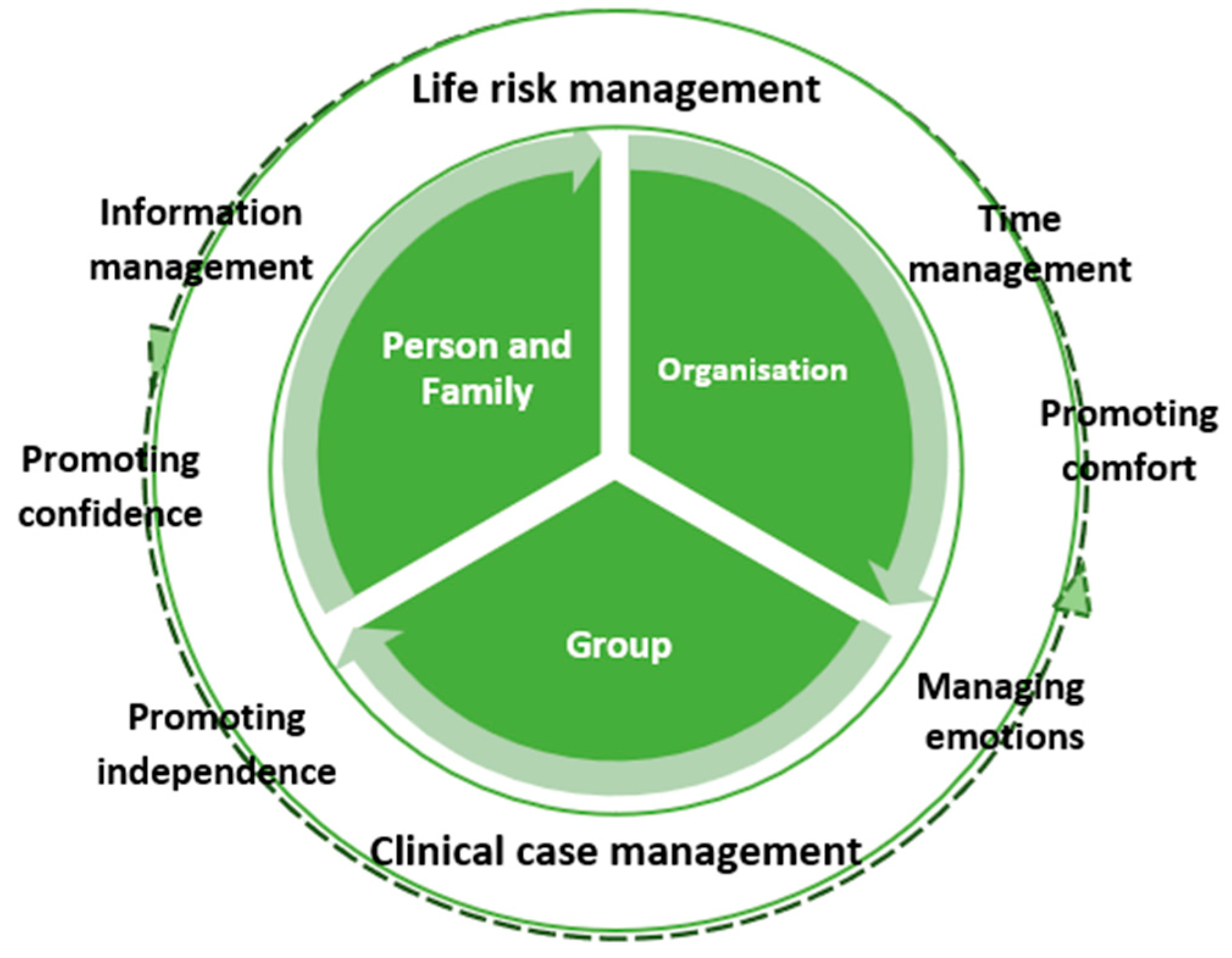

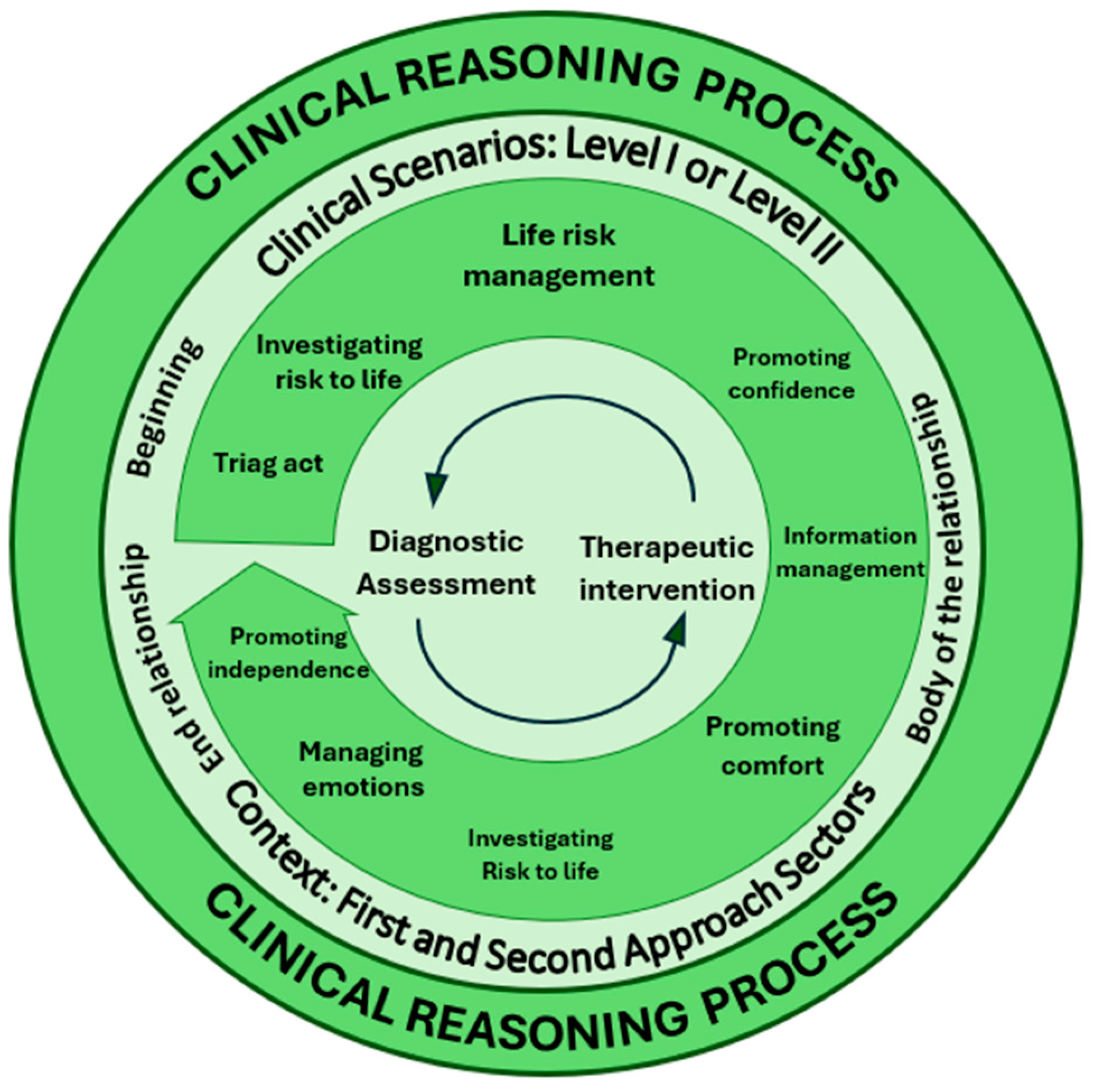

Figure 3 illustrates the Nurses’ Clinical Reasoning Process in the Emergency Department, highlighting the Diagnostic Assessment Process and the Nursing Therapeutic Intervention Process.

In this Clinical Reasoning Process, the following essential aspects can be highlighted:

Duality of the Clinical Reasoning Process, the process consists of two main components: Diagnostic Evaluation and Therapeutic Intervention. These are operationalized through various elements in clinical practice: in evaluation, the nurse focuses on identifying whether there is a life risk or detecting problems expressed by the patient; in intervention, the nurse’s actions are centered on managing life risk, providing information to the patient and family, promoting comfort, and managing emotions. These elements ensure person-centred care tailored to the patient’s clinical condition. The circular arrows at the center of the diagram symbolize the continuous, dynamic interplay between the two processes. This connection resembles the functioning of the human brain, where the: left hemisphere, often linked to logic and analysis, corresponds to data collection and interpretation during diagnostic evaluation and right hemisphere, associated with creativity and intuition, is responsible for organizing actions and fostering active reflection during therapeutic interventions.

Therapeutic Relationship as the Context of Clinical Reasoning, the Clinical reasoning does not occur in isolation but within the therapeutic relationship between nurse, patient, and family. This relationship unfolds in three phases: 1.

Beginning of the relationship, where the nurse collects initial data upon first contact; 2.

Body of the relationship, during which the nurse deepens the assessment and actively intervenes; 3.

End of the relationship, marking the conclusion of direct intervention, often involving information delivery or patient referral. This ongoing interaction ensures the process is not only technical but also relational, addressing the emotional and psychological needs of both patient and family [

34,

35,

36].

Scenarios for the Clinical Reasoning, this process occurs for two key scenarios: Level I – Life Risk, where the primary focus is on evaluating and intervening in critical life-threatening situations; Level II – Patient-Expressed Problems, where the intervention focuses on symptoms or issues raised by the patient, which, while not immediately life-threatening, require attention to prevent complications. These scenarios guide nurses in prioritizing and directing their actions in emergency environments.

Emergency Department Sectors, the Clinical reasoning is influenced by the physical and functional context in which it unfolds. Emergency department sectors can be divided into: First-Approach Sectors, such as triage and emergency rooms, where nurses perform rapid, initial evaluations to determine the severity of the situation; and Second-Approach Sectors, such as observation rooms and desks, where nurses deepen diagnostic evaluations and adjust interventions more precisely as additional patient data becomes available.

In summary, the Nurses’ Clinical Reasoning Process in the Emergency Department is a dynamic, structured, and continuous process that integrates diagnostic analysis, therapeutic intervention, therapeutic relationships, and clinical context. This ensures effective, person-centered care with quick and precise actions in high-pressure environments. Nurses consistently engage in reflection-in-action and reflection-for-action [

6,

37], which are central to clinical reasoning. These reflections occur both during the execution of interventions and while planning subsequent steps. This continuous reflection enhances the precision of interventions and the ability to adapt to changes in the patient’s clinical condition, optimizing decision-making processes. The clinical reasoning process demands structured thinking, where nurses consistently gather, analyze, and act based on data. At the same time, it requires fluid, adaptive thinking that evolves continuously. There is an uninterrupted flow between diagnostic evaluation and practical intervention, as depicted in

Figure 3, which highlights a holistic, patient-centered approach. An equilibrium exists between analysis and action, as well as between logical thinking and intuition. This dynamic cycle guides nurses to deliver effective and humanized care, balancing technical precision with empathy and responsiveness to the patient’s needs.

Limitations of This Study

The study might have limitations related to the size or diversity of its sample population, particularly if it focuses on a specific emergency department or healthcare setting. This could reduce the generalizability of findings to other contexts, specialized units, or healthcare systems with different organizational structures. The study’s focus on a specific environment, such as an emergency department, means its conclusions might not directly apply to other areas of nursing practice, such as community health or long-term care, where clinical reasoning processes might differ.

While the study emphasizes diagnostic evaluation and therapeutic intervention, other influencing factors, such as team dynamics, interprofessional collaboration, or organizational constraints, may not have been explored in depth, leaving a gap in understanding the broader context.

In the future, addressing these limitations could be the robustness and applicability of findings, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of clinical reasoning in nursing practice.

Implications for the Profession and Patients

This study presents a conceptual framework offers valuable contributions to:

Continuous Training Programs: Develop programs that enhance nurses’ clinical reasoning skills and competencies, especially in complex settings.

Nursing Education Curricula: Enrich nursing curricula with strategies and methodologies that strenGrounded Theoryhen clinical reasoning from the early stages of education.

Clinical Practices Improvement: Equip nursing professionals to respond more effectively to critical patient needs, ensuring timely interventions and reducing health complications.

This research underscores the significance of investing in nurse capacity-building to improve care quality, directly benefiting the safety and well-being of patients in high-demand clinical settings.

5. Conclusions

The study underlines the foundational importance of Clinical Reasoning, Therapeutic Intervention, and Therapeutic Relationships in nursing, particularly in urgent care environments. It highlights: Diagnostic Evaluation: A systematic and continuous approach is critical, enabling nurses to assess clinical changes, anticipate risks, and base interventions on updated and relevant data; Therapeutic Intervention: A holistic, patient-centered method addressing life risk management, comfort, emotional support, and communication ensures effective and humanized care; Dynamic Nature: Both components require theoretical knowledge applied practically and adaptively to meet patient and emergency department needs. The reflection and Continuous Learning, is essential for continuous learning and professional development, promoting evidence-based nursing. Investing in training and research enhances nurses’ competencies, improving care quality and patients’ well-being. These findings emphasize the importance of a structured yet adaptive approach in clinical reasoning, balancing analytical thinking and intuitive action for effective, compassionate, and holistic care.

Author Contributions

SM was solely responsible for the conceptualization, design, data collection, analysis, interpretation of the findings, and writing of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Lisbon Central Hospital Center (CH/CE/10-02-2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The complete dataset of the study is available upon request to the author of the research.

Public Involvement Statement

No public involvement in any aspect of this research.

Guidelines and Standards Statement

This manuscript was drafted against the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) [

38].

Use of Artificial Intelligence

AI or AI-assisted tools were not used in drafting any aspect of this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The author extends heartfelt gratitude to the supervisors, the University of Lisbon, Lisbon Central Hospital Center, its nursing staff, and participants for their unwavering support and availability throughout the research process, which was instrumental in making this work possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest, and certify that the submission is original work and is no under review is any other publication.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CE |

Ethics Committee |

| GT |

Grounded Theory |

References

- El Hussein MT, Olfert M, Hakkola J. Clinical judgment conceptualization scoping review protocol. Teaching and Learning in Nursing. 2022;17(1):84-101. [CrossRef]

- Koufidis C, Manninen K, Nieminen J, Wohlin M, Silén C. Grounding judgement in context: A conceptual learning model of clinical reasoning. Medical Education. 2020;54(11):1019-1028. [CrossRef]

- McHugh C, Way J. What is Reasoning? Mind. 2018;127(505):167-196. [CrossRef]

- Abu Arra AY, Ayed A, Toqan D, et al. The factors influencing nurses’ clinical decision-making in emergency department. INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing. 2023;60. [CrossRef]

- Bijani M, Abedi S, Karimi S, et al. Major challenges and barriers in clinical decision-making as perceived by emergency medical services personnel: A qualitative content analysis. BMC Emerg Med. 2021;21:11. [CrossRef]

- Alfaro-LeFevre R. Applying nursing process: A tool for critical thinking. 9ª ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2019.

- Benner P. From novice to expert: Excellence and power in clinical nursing practice. Addison-Wesley; 1984.

- Benner P, Tanner C, Chesla C. Expertise in nursing practice: Caring, clinical judgment, and ethics. Journal of Nursing Education. 2009;45(6):204-211.

- Mendonça S, Lima Basto M, Ramos A. Estratégias de raciocínio clínico dos enfermeiros que cuidam de clientes em situação clínica: revisão sistemática da literatura. RIASE. 2016;2(3):753-773. [CrossRef]

- Simmons B. Clinical reasoning: concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(5):1151-1158. [CrossRef]

- Thompson C, Aitken L, Doran D, Dowding D. An agenda for clinical decision making and judgement in nursing research and education. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2013;50(12):1720-1726. [CrossRef]

- Tanner CA. Thinking like a nurse: A research-based model of clinical judgment in nursing. Journal of Nursing Education. 2006;45(6):204-211. [CrossRef]

- Hall LM, Prescott PA. The nurse-patient relationship: A review of the literature and implications for clinical decision-making. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18(13):1803-1812. [CrossRef]

- Luo QQ, Petrini MA. A review of clinical reasoning in nursing education: based on high-fidelity teaching method. Front Nurs. 2018;3:175-183. [CrossRef]

- Levett-Jones T. Clinical Reasoning: Learning to Think like a Nurse. Frenchs Forest: Pearson; 2013.

- Teixeira CRS, Pereira MCA, Kusumota L, et al. Evaluation of nursing students about learning with clinical simulation. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem. 2015;68(2):284-291, 311-319. [CrossRef]

- Tanner CA. Clinical judgment and evidence-based practice: Toward pedagogies of integration. Journal of Nursing Education. 2008;47(8):335-336. [CrossRef]

- Del Bueno D. A crisis in critical thinking. Nursing Education Perspectives. 2005;26(5):278-282.

- Eisenhauer LA, Hurley AC, Dolan N. Nurses’ reported thinking during medication administration. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2007;39(1):82-87. [CrossRef]

- Fero LJ, Witsberger CM, Wesmiller SW, Zullo TG, Hoffman LA. Critical thinking ability of new graduate and experienced nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2009;65(1):139-148. [CrossRef]

- Koharchik L, Caputi L, Robb M, Culleiton AL. Fostering clinical reasoning in nursing students. American Journal of Nursing. 2015;115(1):58-61. [CrossRef]

- Woods A, Doan-Johnson S. Executive summary: Toward a taxonomy of nursing practice errors. Nursing Management. 2002;33(10):45-48. [CrossRef]

- Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Sochalski J, Silber JH. Implications of nurse staffing and patient outcomes: Review and research. Nursing Research. 2016;65(5):123-134.

- Borzo SR, Cheraghi F, Khatibian M, et al. Clinical reasoning skill of nurses working in teaching medical centers in dealing with practical scenarios of King’s model concepts. BMC Med Educ. 2024;24:280. [CrossRef]

- Bae J, Lee J, Choi M, et al. Development of the clinical reasoning competency scale for nurses. BMC Nurs. 2023;22:138. [CrossRef]

- New South Wales (NSW). Health Incident Management Guidelines. NSW Ministry of Health; 2008.

- Charmaz K, Thornberg R. The pursuit of quality in grounded theory. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2021;18(3):305-327. [CrossRef]

- Glaser BG. Theoretical sensitivity. Sociology Press; 1978.

- Queirós J. The knowledge of expert nurses and the practical-reflective rationality. Investigación y Educación en Enfermería. 2015;33(1):83-91. [CrossRef]

- Rubin HJ, Rubin IS. Qualitative interviewing: The art of hearing data. 3rd ed. Sage Publications; 2011.

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 4th ed. Sage Publications; 2015.

- Streubert HJ, Carpenter DR. Qualitative Research in Nursing: Advancing the Humanistic Imperative. 5th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

- Dilley P. Interviews and the philosophy of qualitative research. The Journal of Higher Education. 2004;75(1):127-132. [CrossRef]

- Lopes M. A Relação Enfermeiro-Doente como intervenção terapêutica. Formasau formação e Saúde, lda; 2006.

- Sapeta P. Cuidar em Fim de Vida. O Processo de Interacção Enfermeiro-Doente. Edição Lusociência; 2011.

- Phaneuf M. Comunicação, entrevista, relação de ajuda e validação. Loures: Lusociência; 2005.

- Schön DA. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. New York: Basic Books; 1983.

- O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245-1251. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).