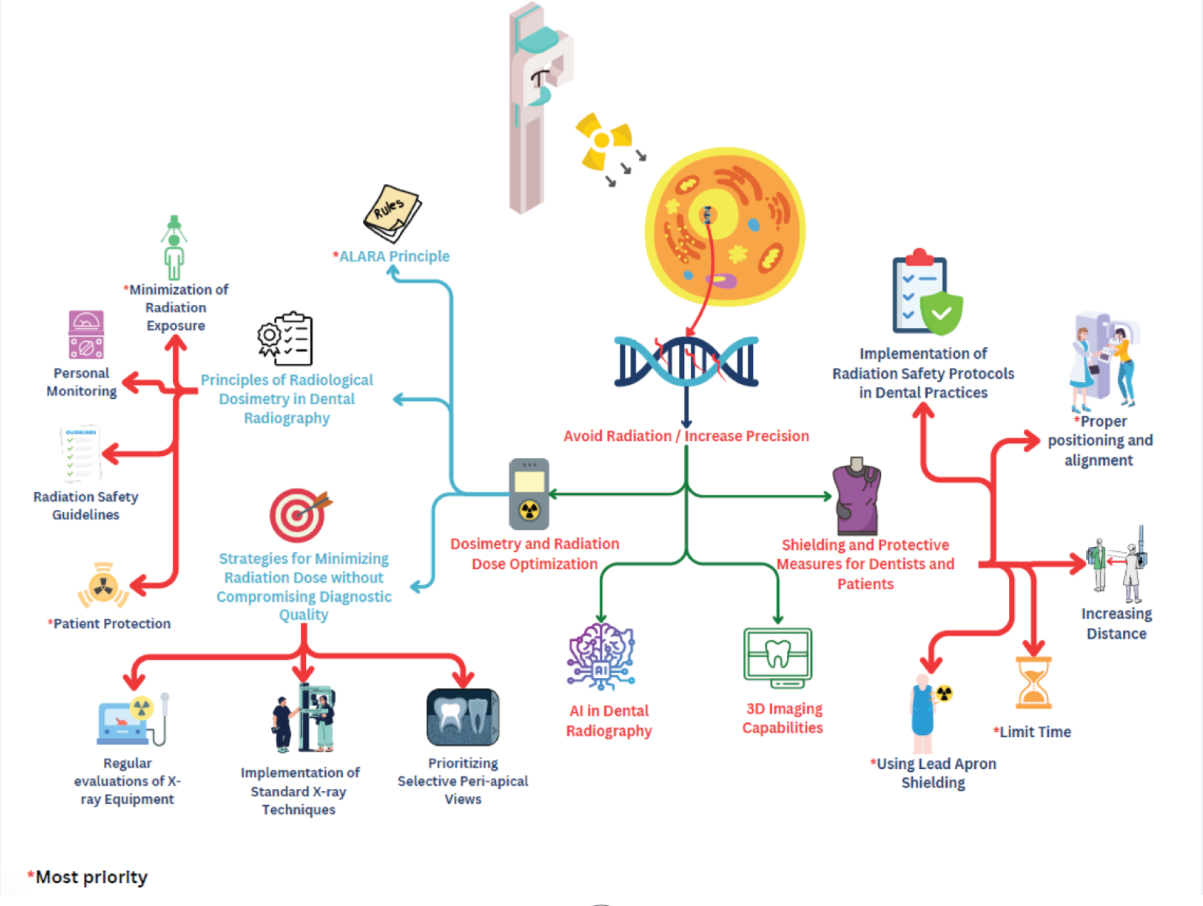

Graphical Abstract

Clinical Relevance

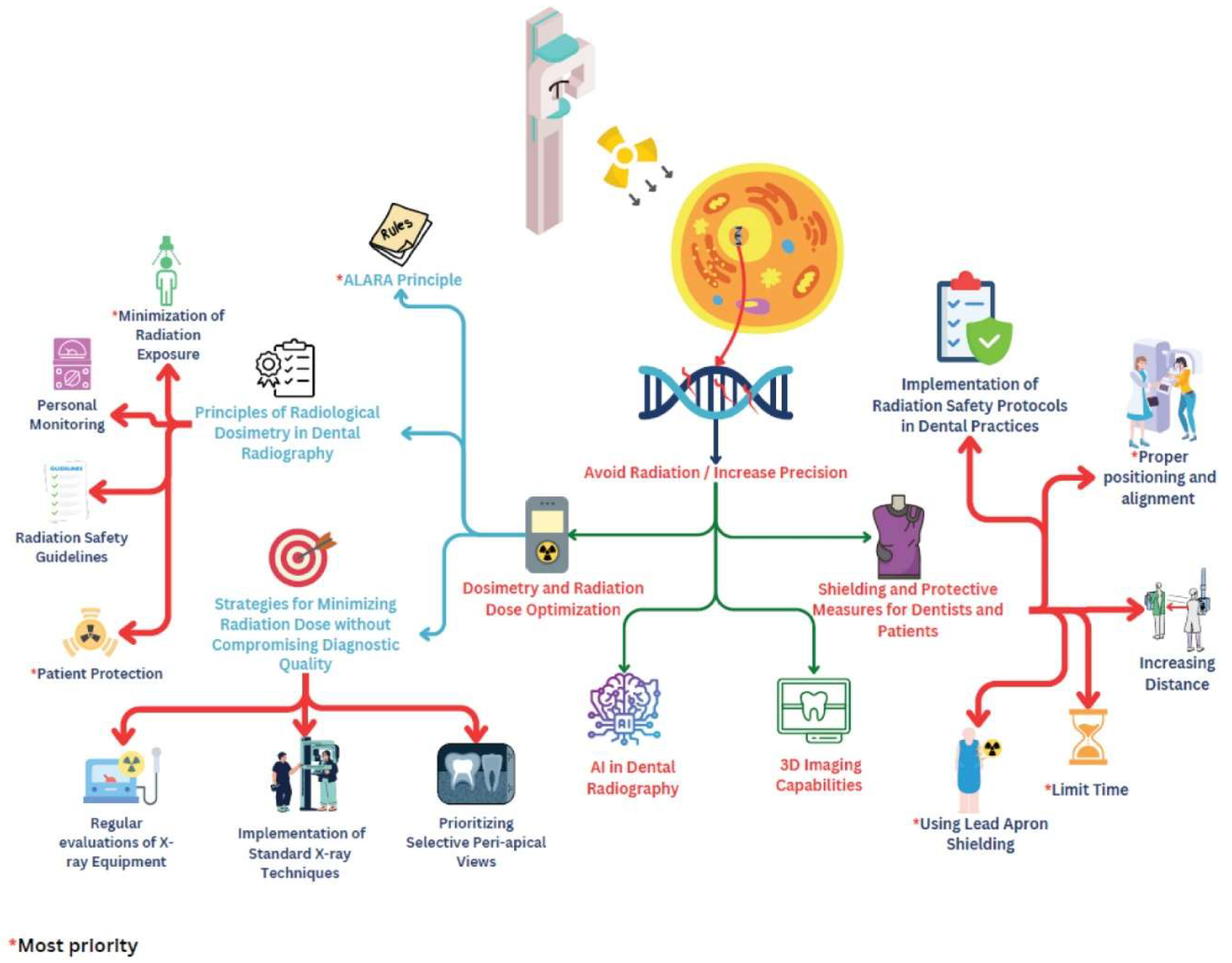

Emerging technologies in dental X-ray imaging, including the utilization of AI and portable X-ray units, have transformed diagnostic approaches, significantly enhancing safety and efficiency. Establishing a direct link between these technological advancements and their application in clinical settings, offering dentists practical solutions for improving patient care. By adopting these innovations, clinicians can better manage radiation exposure and diagnostic accuracy, ultimately leading to earlier and more precise interventions for dental pathologies.

Background

Dental radiography techniques and technologies constitute a rapidly evolving field that plays a pivotal role in modern dentistry, influencing diagnostic precision and patient care. Exploring the intricate realm of advancements in dental X-ray, the analysis encompasses historical developments, recent technological breakthroughs, and the crucial domain of radiation risks and safety measures. The evolution of dental radiography techniques unfolds as a narrative marked by historical milestones, from the nascent stages of root canal studies to the transition from film-based to digital radiography. The emergence of innovative technologies such as cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) serves as a testament to the dynamic trajectory of this field.

Recent technological advancements in dental X-ray equipment have taken center stage, emphasizing the advantages of digital sensors and image processing. The integration of 3D imaging capabilities further enhances diagnostic accuracy, highlighting the transformative potential of advanced X-ray systems [

1,

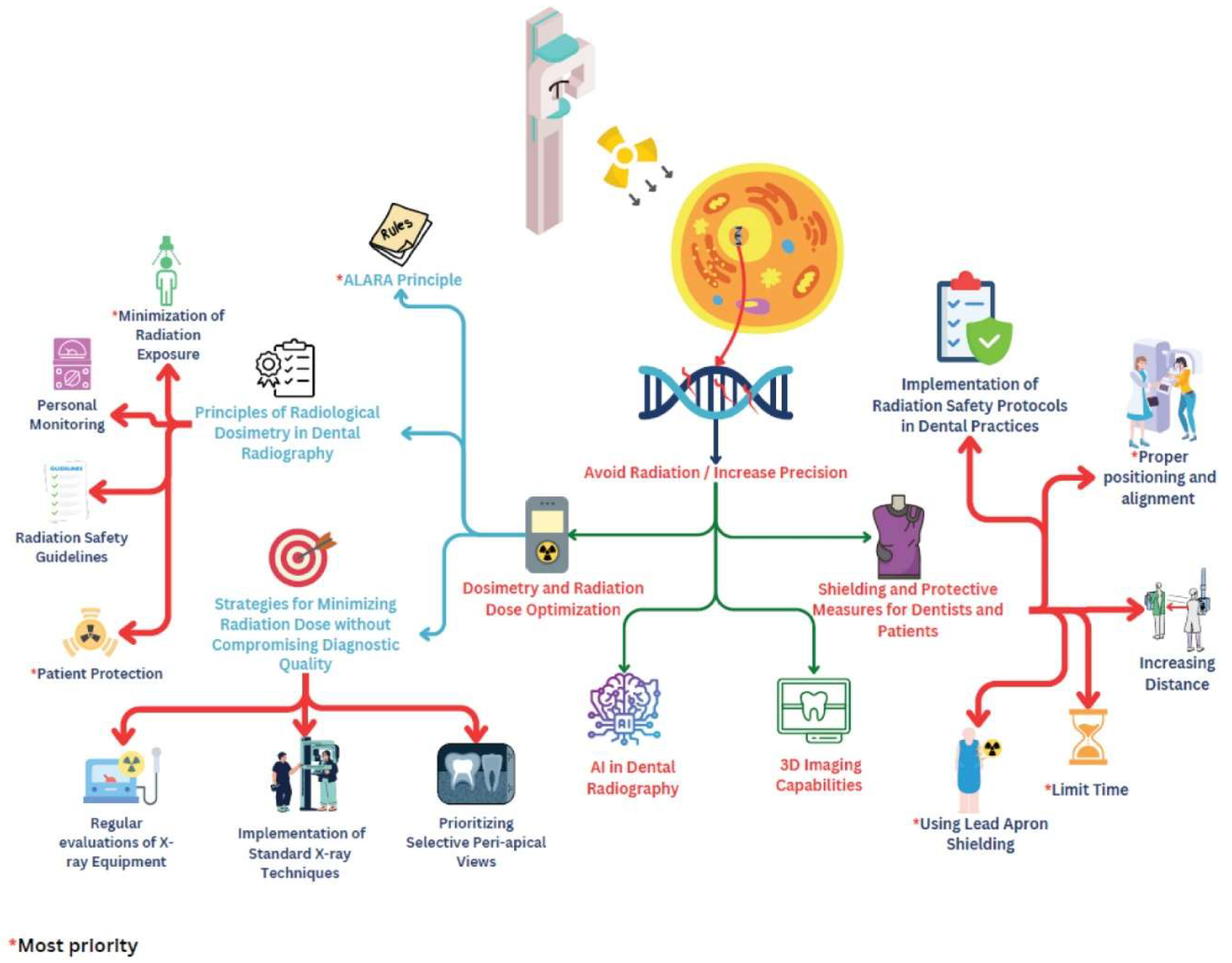

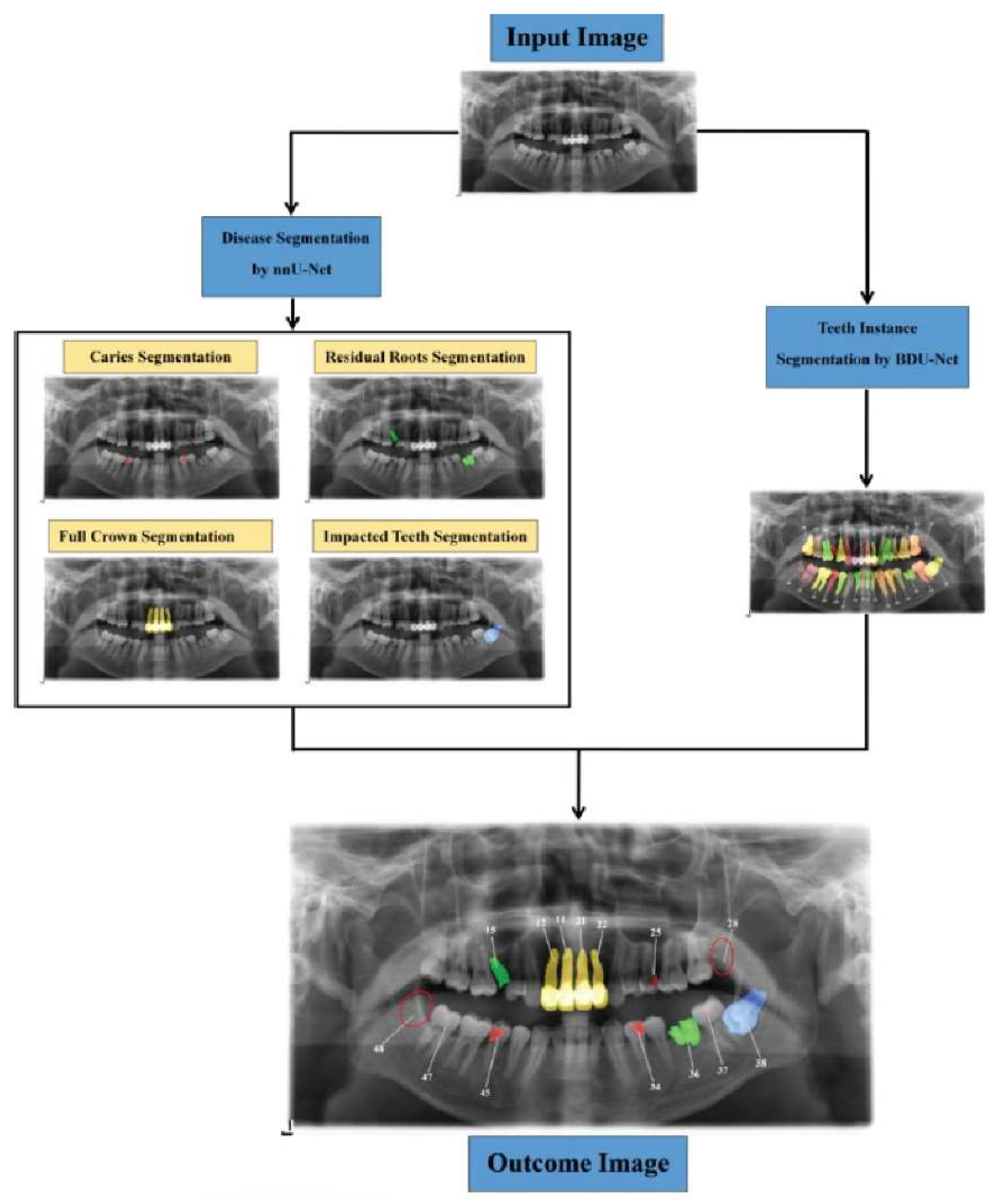

2]. In the transformative landscape of dental imaging, the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) stands out as a pivotal advancement. AI algorithms autonomously detect abnormalities, enhancing diagnostic accuracy and streamlining workflows. This revolution has facilitated early detection and preventative care. Portable X-ray units expand access, particularly in in-home care and geriatric dentistry. Future advancements include refined dose reduction, advanced AI algorithms, and seamless integration with telehealth. These innovations redefine standards, emphasizing clarity, minimized radiation exposure, and operational efficiency, positioning AI as a cornerstone in the evolution of dental X-ray practices [

3].

A comprehensive comparative analysis of radiation exposure levels elucidates dosimetric differences between traditional and modern X-ray techniques, with a focus on optimizing radiation doses for various dental procedures. The ensuing exploration into radiation risks and safety measures elucidates the intricate interplay of ionizing radiation with biological tissues, emphasizing principles of dosimetry and strategies for minimizing radiation dose application [

4].

In addition to advancements in dental radiography, the profound biological ramifications of ionizing radiation have come to the forefront. Compared with high-energy elements, this radiation influences cells and DNA, highlighting the importance of biological dosimetry. Ethical practices prioritize minimizing exposure while optimizing diagnostics [

5]. The pervasive ALARA principle extends its influence across various applications, ensuring safety in dental procedures. Integral shielding measures, including the use of lead aprons, stand as crucial elements in upholding stringent standards within the domain of dental radiography [

6,

7].

The research review then sheds light on the occupational risks faced by dentists, delving into chronic radiation exposure and its potential health implications. Risk mitigation strategies, encompassing training on radiation safety practices and the adoption of ergonomic techniques, are crucial elements in ensuring the well-being of dental professionals. Emerging trends in dentist radiation protection, including technological advances in shielding gear and the integration of automation for reduced exposure, culminate in a discussion of novel materials contributing to radiation attenuation in dentistry. In essence, this research review embarks on a comprehensive journey through the intricate landscape of dental radiography, weaving together historical developments, recent technological insights, and emerging trends that collectively redefine the terrain of modern dentistry and diagnostic imaging [

8].

Dental X-ray Techniques and Technologies

Evolution of Dental Radiography Techniques

The evolution of dental radiography, tracing back to the late 19th century, signifies a crucial leap forward in safety, precision, and effectiveness. Beginning in 1896 with dental images on glass plates or roll film, it sparked a transformative era. Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen's accidental discovery of X-rays in November 1895, notably capturing his wife's hand (

Figure 1), laid the foundation for medical applications. Dr. Otto Walkhoff's groundbreaking dental roentgenogram from January 1896, taken within his own mouth over a 25-minute exposure time, marked a pivotal moment in dental imaging. Subsequent technological advancements have reshaped this field, making dental X-rays more patient friendly, faster, and adaptable across diverse dental disciplines. This historical journey showcases an extraordinary evolution culminating in contemporary innovations that significantly enhance dental radiography in modern practice [

8,

9,

10].

Figure 1.

Frau Roentgen hand with a ring [

10].

Figure 1.

Frau Roentgen hand with a ring [

10].

The integration of X-ray technology into dentistry marked a pivotal milestone in the field's development. This integration was made possible through the groundbreaking work of individuals such as H.R. Raper, the first author of a dental textbook, and F. Gordon Fitzgerald, a pioneer in modern dental radiography. Their refinements in techniques set the stage for subsequent advancements.

From the 1920s to the 1950s, significant progress was achieved in revolutionizing oral X-ray equipment, photographic methods, and procedural approaches. Innovators and dental practitioners play crucial roles in overcoming initial challenges such as extended exposure times and patient discomfort. Their dedication led to quicker processes, improved safety protocols, and cost reductions, heralding the shift from cumbersome photographic film to the immediacy of digital radiography.

Advancements in dentomaxillofacial radiology over the last fifty years have predominantly centered around the evolution of equipment and methodologies, shaped by the innovations brought forth by industry experts. Since the late 1960s, the introduction of the International Association of Dento-Maxillo-Facial Radiology marked the beginning of a transformative era that redefined radiographic practices. Subsequent decades have witnessed the gradual acceptance of technologies that have revolutionized not just the functionality but the safety of radiographic practices in the dental field [

11].

Recent Technological Advancements in Dental X-Ray Equipment

In recent years, the domain of dental X-ray equipment has undergone a profound evolution, marked by a concerted drive toward increasing imaging precision, mitigating patient radiation exposure, and optimizing operational workflows. These transformative advancements are reshaping the landscape of oral healthcare, promising substantially improved outcomes for patients.

The pivotal shift from traditional film-based X-rays to digital X-ray sensors is a hallmark of this progression. These state-of-the-art sensors capture electronic X-ray images, circumventing the need for chemical processing while drastically reducing patient radiation exposure. Their advent has ushered in a new era characterized by expeditious image acquisition, unparalleled image quality allowing for intricate anatomical scrutiny, and immediate display on computer screens, thereby enabling swift diagnosis and treatment planning. Additionally, the inherent flexibility of digital images facilitates seamless storage and electronic dissemination, bolstering workflow efficiency and collaboration among dental professionals.

A cornerstone of this technological renaissance is the emergence of cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT). This sophisticated 3D imaging modality delivers comprehensive cross-sectional views of the dental anatomy, offering unparalleled diagnostic accuracy. CBCT excels in revealing previously concealed anomalies, such as fractures, tumors, and impacted teeth, increasing the precision of treatment planning and often obscuring the necessity for supplementary imaging procedures [

1,

12].

Artificial intelligence (AI) integration represents another watershed moment in dental X-ray analysis. AI algorithms adeptly analyze X-ray images and automatically detect and highlight minute abnormalities such as caries, periodontal diseases, and bone loss. This revolutionary integration augments diagnostic accuracy, streamlines workflow by automating labor-intensive tasks, and crucially facilitates the early detection of dental issues, enabling timely interventions and preventative care [

13].

Furthermore, the advent of portable and compact X-ray units has broadened the horizons of dental imaging, particularly in home care and geriatric dentistry. These portable units, characterized by their light weight and transportability, facilitate bedside or remote X-rays, increase accessibility to imaging services, alleviate patient anxiety, and ensure swift and accurate diagnoses (

Figure 2) [

14].

The future trajectory of dental X-ray equipment is poised for even greater innovation. Anticipated advancements encompass refined dose reduction technologies to minimize patient radiation exposure further, the development of advanced AI algorithms for nuanced and precise analysis, and seamless integration with telehealth platforms, enabling remote consultations and diagnostics [

3]. These collective advancements underscore a transformative paradigm shift in oral healthcare, emphasizing unparalleled imaging clarity, minimized radiation exposure, and enhanced operational efficiency, all converging to redefine standards of patient care and outcomes in dentistry (

Figure 3).

Comparative Analysis of Radiation Exposure Levels

Dental X-rays are indispensable tools in dental care, providing essential information for diagnosis and treatment planning. They fall into two primary categories: 2D, encompassing intraoral and panoramic X-rays, and 3D, such as cone beam computed tomography (CBCT), each offering distinct imaging perspectives. Understanding their diverse radiation exposure levels is critical for their responsible and informed utilization [

15].

Intraoral X-rays, tailored for detailed views of individual teeth, subject patients to a relatively low dose of 1.3 μSv, whereas panoramic X-rays, which capture a wider jaw perspective, increase the exposure to 17.9 μSv. The more intricate nature of CBCT, which delivers comprehensive three-dimensional images, significantly increases exposure to 121.1 μSv because of its detailed output and broader coverage [

16].

Several factors influence radiation exposure during dental X-ray examinations. Modern equipment, especially digital sensors, emits lower radiation doses than older film-based systems do. Precise X-ray techniques, including proper positioning and collimation, contribute to minimizing unnecessary exposure. Additionally, the frequency of X-rays and patient age are crucial determinants; children, who are experiencing rapid growth and development, are more susceptible to radiation effects [

17].

The International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) guidelines emphasize judicious X-ray usage. These recommendations stress minimizing doses, precisely targeting X-rays to the specific area of interest, and limiting exposures to essential diagnostic needs. Special attention is given to pregnant women, where considerations of risks and benefits are paramount, necessitating informed decision-making regarding X-ray usage during pregnancy [

18].

The careful balance between diagnostic effectiveness and radiation safety is central to dental practice. Adhering to these stringent guidelines ensures that the benefits of X-rays prevail, facilitating optimal oral healthcare while responsibly managing potential risks associated with radiation exposure.

Radiation Risks and Safety Measures

Ionizing Radiation and Biological Effects

1. Understanding the Interaction of Radiation with Biological Tissues

The biological effects of electromagnetic radiation (EMR) are influenced by its physical properties, particularly its ionizing potential. Ionizing radiation (IR) includes high-energy photons, alpha particles, protons, and neutrons. At elevated doses, it can be deadly to living organisms. Excessive exposure to ionizing radiation (IR) can lead to acute radiation syndrome, which may cause organ failure or death. Initial symptoms often include a decrease in lymphocytes, reduced cellular immunity, anemia, temporary infertility, radiation-induced skin damage, hair loss, clouding of the lens, and severe inflammation of the intestines. Long-term effects might involve the onset of cancers such as leukemia. On the other hand, nonionizing radiation (NIR), which has lower energy levels, does not induce lethal ionization in atoms or molecules. [

19,

20].

Ionizing radiation can transfer energy upon interacting with matter. It can be classified into two types: direct ionization and indirect ionization. Directly ionizing radiation releases energy through Coulomb interactions with the orbital electrons of a material. Conversely, indirect ionizing radiation involves a two-step process. Initially, primary radiation interacts with the absorbing medium, leading to the release of charged particles. These charged particles subsequently deposit energy by interacting with the material's orbital electrons through Coulomb forces. [

4,

21,

22].

Biological dosimetry is essential for radiation protection and medical treatment of individuals exposed to radiation. It involves assessing the degree of cellular damage caused by radiation, often by counting dicentric chromosomes (DCs), centric rings, or micronuclei. The prevalence of these chromosomal abnormalities is well recognized as a biological marker of radiation dose. Precisely measuring the absorbed radiation dose is vital for forecasting the immediate, intermediate, and long-term health impacts on those exposed to radiation. Estimation of the dose via biomarkers of chromosome damage is essential because it accounts for the interindividual variability in radiation susceptibility, complementing direct physical measurements of the dose [

4,

22].

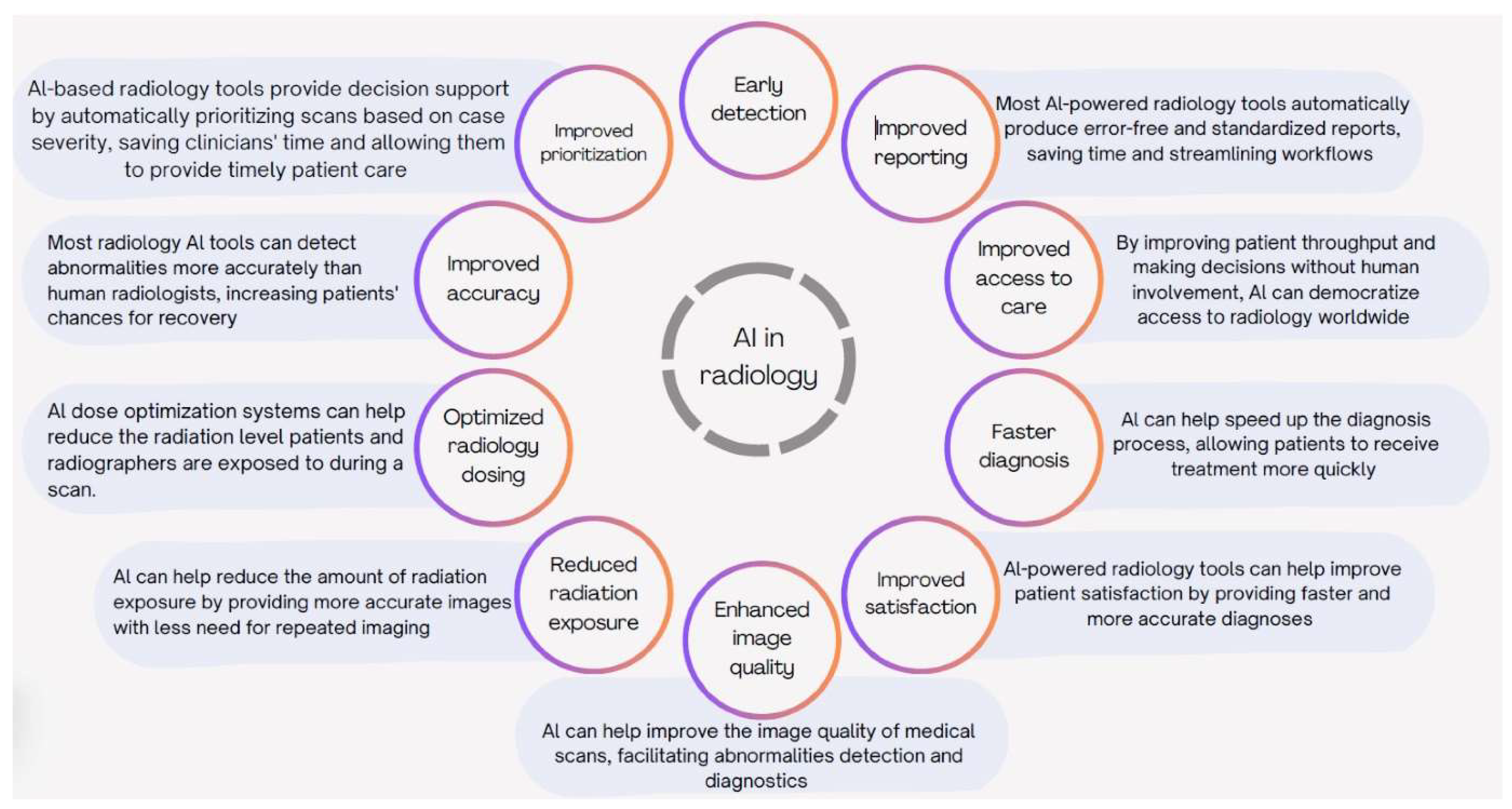

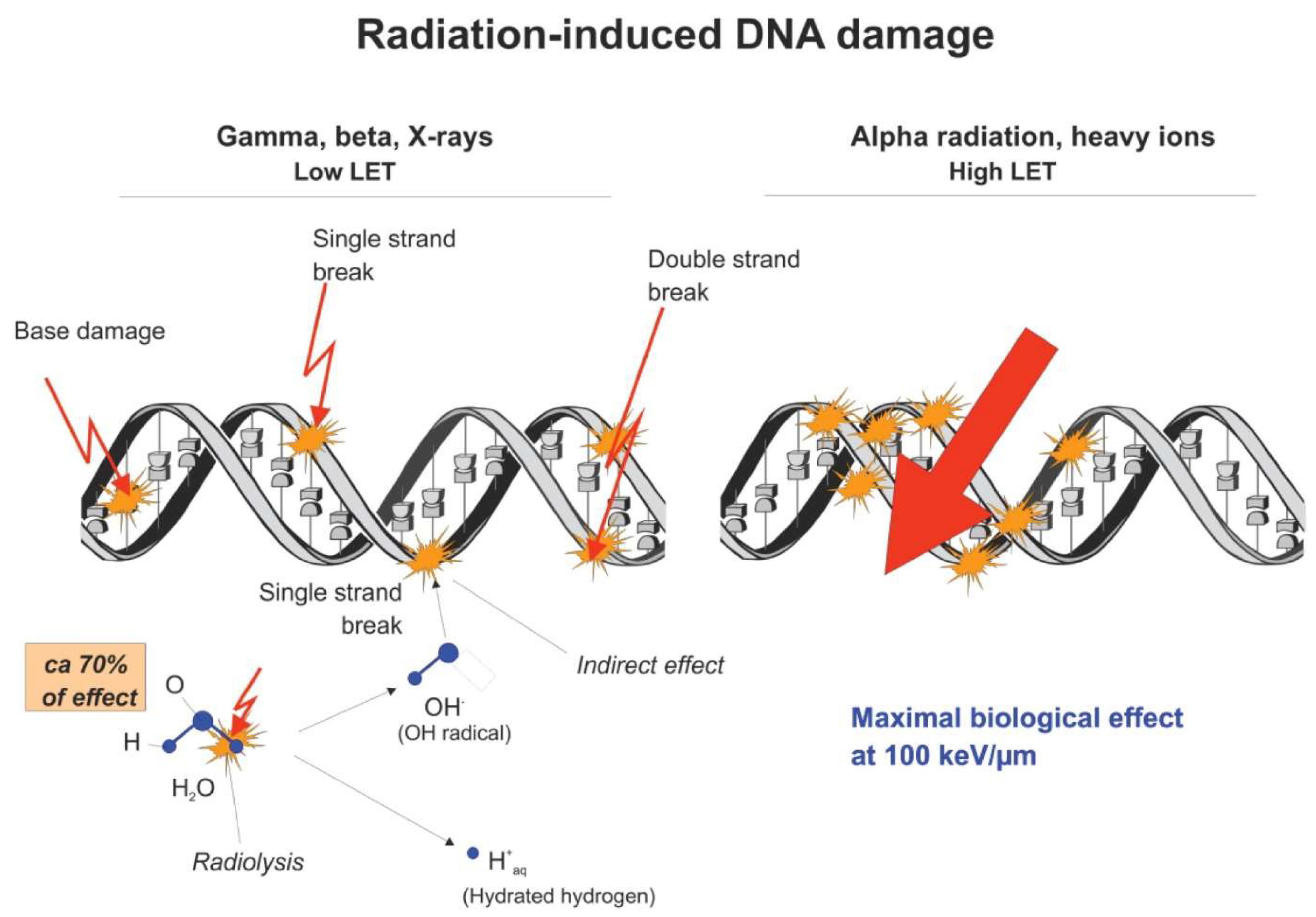

2. Effects of Radiation Exposure on Cells, DNA, and Genetic Materials

When ionizing radiation interacts with a cell, distinct outcomes can be observed. First, radiation may pass through the cell without causing significant damage to the DNA. Alternatively, radiation can lead to DNA damage, in which the cell's repair mechanisms are capable of mending. In another condition, radiation may interfere with the accurate replication of DNA, resulting in errors within the DNA sequence. Finally, radiation can inflict severe DNA damage that surpasses the cell's repair capacity, promoting the activation of apoptosis, a programmed cell death mechanism.

Ionizing radiation directly interacts with DNA atoms, disrupting cellular reproduction and critical systems. This interaction can lead to cancer development. Alpha particles, beta particles, and X-rays can affect DNA by changing the base chemical structure, breaking the sugar‒phosphate backbone, or disrupting hydrogen bonds between base pairs. Ionizing radiation also impacts molecules beyond DNA, breaking water molecule bonds and generating reactive free radicals such as H+ and OH- ions. These free radicals readily combine with other ions in cells, leading to DNA damage, aging, and diseases such as cancer, Alzheimer's disease, and Parkinson's disease. This highlights the intricate molecular effects of ionizing radiation on cellular components [

5,

23]. Ionizing radiation (IR) can cause damage to DNA through two distinct mechanisms known as direct effects and indirect effects (

Figure 4). The direct effect involves radiation particles interacting directly with DNA molecules, leading to disruptions in their molecular structure. This effect is more prominent with high linear energy transfer (LET) radiation and at higher radiation doses. Conversely, in the indirect effect, radiation initially induces radiolysis by interacting with water molecules, which are abundant in cells. The resulting radiolysis products, such as free radicals and hydrogen peroxide, can then react with neighboring molecules within a proximity of less than 4 nanometers. The indirect effect is considered the primary pathway for DNA damage caused by low LET radiation [

24].

3. Factors influencing the severity of biological effects

Several factors affect the biological consequences of ionizing radiation exposure. These include the radiation quality, dose rate, temperature, and exposure to mixed radiation beams. Radiation quality pertains to the specific type of ionizing radiation, which significantly influences its biological efficacy. The dose rate denotes the velocity at which radiation is delivered and plays a role in determining the biological response. Temperature conditions during radiation exposure have been investigated to evaluate their potential radioprotective properties. Furthermore, the effects of combined exposure to diverse forms of ionizing radiation in mixed beam scenarios on the cellular response are examined. Acknowledging these factors is of utmost importance in the realms of radiation protection and risk prediction [

24].

Dosimetry and Radiation Dose Optimization

1. Principles of Radiological Dosimetry in Dental Radiography

The principles of radiological dosimetry in dental radiography underscore the importance of minimizing radiation exposure while acquiring diagnostically valuable images. The following are noteworthy findings:

(1)Minimization of Radiation Exposure: There is an ethical responsibility for dental professionals to minimize radiation exposure while maximizing diagnostic benefits for patients. The ALARA (as low as reasonably achievable) principle is used to restrict patient exposure. This is accomplished through the utilization of the swiftest image receptor, reduction of the X-ray beam size, and implementation of protective measures such as leaded aprons and thyroid collars [

6,

7,

25].

(2)Personnel monitoring: Routine personnel monitoring is generally considered desirable, albeit not indispensable, for dental staff members, as they typically receive low radiation doses. Compliance with diverse national regulations is imperative, and monitoring may not be obligatory unless the risk assessment reveals that individual doses are likely to exceed 1 mSv per year [

26,

27].

(3)Radiation Safety Guidelines: Rigorous adherence to radiation safety guidelines is imperative for ensuring the well-being of dental patients. This encompasses limiting the number of radiographs taken, avoiding unnecessary and repetitive examinations, and implementing quality assurance programs to guarantee the appropriate utilization of radiographic equipment and techniques [

28,

29].

Patient protection: Protective measures for patients include the use of lead aprons and thyroid collars, the use of modern X-ray equipment, and restrictions on the number of images taken within a year. The radiation dosage utilized for obtaining dental radiographs is exceedingly minute, and the ALARA principle strives to minimize exposure while preserving diagnostic quality [

6,

7,

30].

2. Strategies for Minimizing Radiation Dose without Compromising Diagnostic Quality

The following measures can be adopted in line with the ALARA principle to effectively minimize radiation exposure for both dental patients and operators.

(1)Implementation of standard X-ray techniques:

Dental professionals should employ accurate standard X-ray techniques to ensure the production of high-quality radiographs. This, in turn, minimizes the need for repeated exposure of the patient.

(2)Prioritizing Selective Peri-apical Views:

During the initial visits of patients, dental professionals should prioritize the use of selective peri-apical views.

(3)Regular evaluation of X-ray equipment:

Regular assessment of X-ray equipment is imperative to ensure proper radiation exposure levels and to detect any potential radiation leakage. According to Praveen BN, a well-calibrated dental X-ray machine should have an output of 0.7 to 1 R/sec. Additionally, calibration should be evaluated every three years to maintain precision [

6].

3. Application of the ALARA (as low as reasonably achievable) principle

The ALARA (as low as reasonably achievable) principle is a core concept in radiation protection and is aimed at minimizing radiation exposure to both employees and the general public. This principle has been applied in various fields, including medical imaging, nuclear power plants, industrial radiography, radiation therapy, and environmental remediation. In medical imaging, ALARA is employed to minimize radiation exposure during procedures such as X-rays, CT scans, and nuclear medicine. Similarly, in nuclear power plants, ALARA is utilized to mitigate radiation exposure to workers and the public during plant operation and maintenance. Industrial radiography procedures, which involve the use of radioactive sources for material and structure inspection, also adhere to the ALARA principle to minimize radiation exposure. In radiation therapy for cancer treatment, ALARA is applied to minimize radiation exposure to healthy tissues. Finally, during environmental remediation activities aimed at cleaning contaminated sites, ALARA is implemented to minimize radiation exposure to workers and the general public [

31,

32].

Shielding and Protective Measures for Dentists and Patients

1. Use of lead principles, thyroid collars, and protective barriers

In interventional pain management, the utilization of lead aprons, thyroid collars, and protective barriers is crucial for minimizing radiation exposure to both patients and healthcare providers. Lead aprons combined with thyroid shields are particularly effective in reducing radiation exposure during these procedures. Employing lead aprons, thyroid collars, and floor-to-table lead shielding significantly reduces scatter radiation exposure. Regular inspection of radiation protective garments ensures their integrity and effectiveness. Thyroid shields are crucial for protecting vulnerable thyroid glands from radiation exposure. To ensure effective radiation attenuation, lead aprons, thyroid collars, and lead shielding should provide a minimum lead equivalence of 0.5 mm. Educating healthcare providers on radiation safety and the proper use of protective devices is important for minimizing radiation exposure [

33,

34].

2. Proper Positioning and Alignment for Effective Shielding

In dental procedures involving radiation, ensuring appropriate positioning and alignment of thyroid collars and protective barriers is essential for effective shielding. The thyroid gland is particularly susceptible to scatter radiation, necessitating the use of thyroid shields to safeguard this critical organ from radiation exposure. To ensure effective radiation attenuation, lead aprons, thyroid collars, and lead shielding should possess a minimum lead equivalence of 0.5 mm.

Proper positioning and alignment of thyroid collars and protective barriers play pivotal roles in achieving effective shielding. The thyroid collar should be positioned near the thyroid gland, while the protective barrier should be appropriately placed to shield the targeted area while minimizing radiation exposure to other body regions. It is imperative to ensure that the protective devices are correctly aligned and securely fastened during the procedure to prevent displacement, as this can compromise their ability to reduce radiation exposure [

35,

36].

3. Implementation of Radiation Safety Protocols in Dental Practices

Radiation safety protocols in dental practices encompass various essential elements, such as patient positioning, dental personnel protection, equipment and shielding considerations, radiation safety training, and adherence to regulatory compliance. Optimal patient positioning is vital for minimizing radiation exposure. Dental personnel should maintain a safe distance of at least six feet from the patient or position themselves behind a protective shield, ensuring that they are not in the path of the useful beam. The positioning angle should range between 90° and 135° relative to the direction of the primary beam during exposure [

37].

Dental offices should be designed and constructed according to the minimal shielding requirements established by the National Council on Radiation Protection (NCRP). Protective equipment and shielding devices must be correctly utilized to reduce radiation exposure as effectively as possible. Dental professionals must undergo radiation safety training that encompasses ALARA principles, radiographic procedures, safe operation of different types of dental X-ray units, proper technique selection on the basis of a technique chart, patient radiation protection, and accurate processing of image receptors [

38,

39].

Dentist Occupation Risk

Chronic Radiation Exposure and Health Implications

The radiation dose is a critical measure of the energy absorbed by an object or individual when exposed to X-rays, which can potentially cause harm. Various quantities are used to express this dose, but the effective dose, which reflects the overall biological impact of radiation on the human body, cannot be measured directly. Instead, other measurable dose quantities are employed for optimization, dose monitoring, and quality assurance, and these quantities are specific to different imaging techniques.

In dental radiology, the commonly measured quantity is the entrance surface air kerma or dose. This is expressed in gray (Gy), although in dental contexts, it is typically reported in milligrams (mGy) or micrograys (µGy) owing to the smaller dose levels.

For cephalometric, panoramic radiography, and cone beam computed tomography (CBCT), the kerma-area product, which represents the product of kerma (dose) and the X-ray field, is commonly measured. This value is expressed in mGy.cm² [

40].

The typical effective doses for various dental imaging procedures are as follows:

Intraoral dental X-ray imaging procedure: 1–8 microsievers (μSv)

Panoramic examinations: 4–30 μSv

Cephalometric examinations: 2–3 μSv

CBCT procedures (median values from the literature): 50 μSv or less for small- or medium-sized scanning volumes and 100 μSv for large volumes.

Consequently, the doses from intraoral and cephalometric dental radiological procedures are typically quite low, often less than a single day's natural background radiation. Panoramic procedures involve a broader range of doses, but even at their highest doses, they are comparable to a few days of natural background radiation or similar to those of a chest X-ray. The doses from cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) can vary widely, potentially being tens or even hundreds of microsieverts higher than those from conventional radiographic methods, depending on the specific technique used [

16]. Extended exposure to radiation in dentistry can negatively affect dentists, especially in sensitive areas such as the eyes and skin. The eyes may be prone to conditions such as cataracts due to radiation exposure, whereas the skin might experience problems such as erythema and changes in pigmentation. It is vital for dentists to employ protective measures, including the use of lead aprons and collimators, to reduce radiation exposure and address potential health risks. Consistent monitoring and strict adherence to safety protocols are essential to safeguard the health of dental professionals [

41].

Risk Mitigation Strategies for Dental Professionals

Ensuring radiation safety and adhering to protection guidelines are critical in dentistry. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) oversees permitted radiation exposure for adults handling radioactive materials, with occupational limits set at 5,000 mrem annually. Dental practitioners, including hygienists, oral surgeons, and orthodontists, must meet these exposure thresholds. Despite generally facing lower ionizing radiation than other healthcare roles do, it is essential to follow basic protective measures to minimize occupational radiation exposure and uphold ALARA standards. When X-ray equipment is used, dental professionals should use personal dosimeters such as cost-effective Instadose+ devices for accurate, wireless exposure monitoring. This device effortlessly captures, transmits, measures, and analyzes radiation dose exposure via Bluetooth and SmartMonitoring technology, providing convenient real-time access to exposure history. Unlike conventional film badges, the Instadose+ dosimeter eliminates the need for offsite collection and processing.

To minimize exposure, dental professionals should follow standard guidelines regarding time, distance, and shielding. This involves reducing the time spent near a radiation source, maintaining a safe distance, and using protective barriers during procedures. Healthcare practitioners should follow state regulations on ionizing radiation use, especially concerning operator positioning during X-ray procedures. Adhering to the position-and-distance rule is crucial, requiring the operator to be positioned at least 6 feet away from the patient at an angle ranging from 90° to 135° to the central ray of the X-ray beam. This rule not only uses the inverse square law to reduce X-ray exposure but also takes advantage of the patient's head absorbing the majority of the scatter radiation at this specific position. Notably, many dental clinics may lack sufficient space to maintain a 6-foot distance, and in such cases, effective barriers are recommended. Additionally, reducing the radiation dose can be achieved by using faster films to decrease the exposure time, employing electronically controlled timers for optimal dosing, and integrating computers and digital imaging technology [

41,

42,

43].

Emerging Trends in Dentist Radiation Protection

The strategic incorporation of automation and robotics in dental practices aims to minimize direct radiation exposure for dentists during procedures. Purposefully engineered robotic systems empower dentists to remotely control equipment and distance themselves from radiation sources. Researchers are actively exploring the synergy of artificial intelligence and robotics in dentistry, enabling precise and automated dental procedures such as tooth preparation, dental implant placement, and repetitive tasks with high precision. This progressive approach prioritizes the safety of dental professionals while embracing the benefits of technological innovation. In one study, a 6-DoF robotic arm was proposed for executing the positioning of the film/sensor and the X-ray source, demonstrating superior accuracy and repeatability compared with those of mechanical alignment approaches. Additionally, a robotic system equipped with a skull was presented in the literature to investigate the impact of head movement on the accuracy of 3D imaging [

44,

45].

Different materials are used as radiation shielding barriers in radiation facilities to ensure a safe environment for routine operations. Selecting appropriate shielding materials involves evaluating their properties, such as a high atomic number (high-Z) for gamma radiation, with barium (Ba), lead (Pb), and bismuth (Bi) being commonly preferred. On the other hand, materials with low atomic numbers are better suited for neutron attenuation. However, traditional shielding materials such as barium, lead, and bismuth have limitations, including issues related to cost, weight, and toxicity.

To overcome these challenges, there has been a growing emphasis on developing alternative materials, leading to the synthesis and use of polymeric and plastic materials, which have become crucial in the materials science industry. Polymers, consisting of bonded molecules, are considered advantageous in radiation shielding because of their elasticity, compatibility, affordability, and light weight, making them effective for radiation attenuation. Additionally, polymers, which contain low-atomic-number elements such as carbon (C), hydrogen (H), oxygen (O), and nitrogen (N), are widely used in medical fields as tissue-equivalent and phantom materials that mimic the human body. These materials are also common in various everyday applications, including industry, research, tissue engineering, electronics, and drug delivery. The interaction of polymer materials with radiation plays a significant role in their effectiveness across these scientific and practical applications. Materials with dense structures generally offer enhanced radiation resistance because of their high symmetry. Organic materials that interact with radiation undergo processes such as oxidation, gas generation, and depolymerization. In polymers, radiation resistance relies on factors such as the oxygen rate and volume present in the material. Organic polymer materials are known for their light weight, resistance to corrosion, low dielectric constant, and suitability for a range of applications that involve radiation hazards. [

8,

46].

Conclusion

The landscape of dental radiography has undergone a remarkable transformation, evolving from primitive imaging techniques with high radiation exposure to advanced digital modalities that prioritize both diagnostic precision and patient safety. This evolution reflects a dynamic interplay between technological innovation and a steadfast commitment to minimizing risks associated with radiation exposure.

The integration of digital imaging technologies, such as digital sensors and CBCT, has revolutionized diagnostic capabilities in dentistry. These advancements have not only enhanced image quality and reduced the need for chemical processing but have also significantly lowered radiation doses to patients. The advent of AI further amplifies these benefits by enabling autonomous detection of dental anomalies, streamlining diagnostic workflows, and facilitating early interventions.

Understanding the biological effects of ionizing radiation on tissues, cells, and DNA underscores the necessity for rigorous safety measures. Adherence to the ALARA principle and implementation of radiation safety protocols are essential strategies in protecting both patients and dental professionals. Protective measures, including the use of lead aprons, thyroid collars, and proper shielding techniques, play a critical role in minimizing exposure and mitigating occupational risks.

Emerging trends such as portable X-ray units have expanded access to diagnostic imaging, particularly benefiting geriatric and homebound patients. The integration of automation and robotics, along with the development of novel materials for radiation attenuation, points toward a future of safer, more efficient dental radiography. These innovations not only enhance operational efficiency but also contribute to reducing direct radiation exposure for dental professionals.

The advancements highlighted in this review are of profound importance to the field of dentistry. They signify a commitment to embracing cutting-edge technologies that enhance diagnostic accuracy while upholding the highest standards of patient and practitioner safety. By continuously integrating these innovations, dental professionals can improve patient outcomes, streamline clinical workflows, and set new benchmarks for safety and efficacy in dental imaging.

In essence, the journey of dental radiography reflects a dedication to excellence in patient care and a proactive approach to mitigating risks. The ongoing evolution in this field promises to further revolutionize dental practice, ensuring that the smiles of tomorrow are not only brighter but also safeguarded by the pinnacle of technological advancement and safety protocols.

Statements and Declrations

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

No source of funding

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

We declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Patient Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Permission to Reproduce Material from Other Sources

Not applicable.

Clinical Trial Registration

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

All the authors conceived and designed the review paper, contributed significantly to the drafting and refinement of the manuscript, and provided substantial intellectual input throughout the analysis and critical review process. Additionally, all the authors actively participated in the acquisition of relevant literature and materials, ensuring the accuracy and completeness of the content. Furthermore, all the authors were involved in the critical review and revision of the manuscript, providing valuable insights and feedback. Finally, all the authors have given their final approval of the version to be published and take full responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the work.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere appreciation to our supervisor, Ali Alsuraifi, for his invaluable contributions to this research review paper. His significant input in refining the content and providing final approval of the manuscript played a crucial role in its completion. We would also like to extend our heartfelt appreciation to Abdullah Ayad for his outstanding contributions to this research review paper. His leadership in guiding the entire review process and exceptional contributions were instrumental in shaping the quality and completeness of this work. Special thanks are due to Umalbaneen I. Al-Essa and Ibrahim Alshakhs for their meticulous efforts on the figures and the graphical abstract, which greatly enhanced the visual appeal and clarity of our findings. Their creative and technical expertise played a vital role in illustrating the complex concepts discussed in this paper.

Declaration Regarding the Use of AI-Assisted Readability Enhancement

I hereby affirm that the utilization of AI-assisted tools in the refinement of the manuscript was strictly limited to enhancing its readability. At no point were AI technologies employed to supplant essential authorial responsibilities, including the generation of scientific, pedagogic, or medical insights; the formulation of scientific conclusions; or the issuance of clinical recommendations. The implementation of AI for readability enhancement was rigorously supervised under the discerning eye of human oversight and control.

References

- Pauwels, R. History of dental radiography: Evolution of 2D and 3D imaging modalities. Med Phys Int, 2020, 8, 235–77. [Google Scholar]

- Sunilkumar, A.P.; Parida, B.K.; You, W. Recent Advances in Dental Panoramic X-ray Synthesis and its Clinical Applications. IEEE Access 2024, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anil, S.; Porwal, P.; Porwal, A. Transforming Dental Caries Diagnosis Through Artificial Intelligence-Based Techniques. Cureus 2023, 15, e41694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludovici, G.M.; Cascone, M.G.; Huber, T.; et al. Cytogenetic biodosimetry techniques in the detection of dicentric chromosomes induced by ionizing radiation: A review. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2021, 136, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radiation effects on cells & DNA | Let’s talk science (2020). Available at: https://letstalkscience.ca/educational-resources/backgrounders/radiation-effects-on-cells-dna.

- Dental radiographs. (2011). The Journal of the American Dental Association, 142, 1101. [CrossRef]

- Visbal, J.H.W.; Pedraza, M.C.C.; Khoury, H.J. Protección Radiológica en Radiología Dental. CES Odontología 2021, 34, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- More, C.V.; Alsayed, Z.; Badawi, M.S.; Thabet, A.A.; Pawar, P.P. Polymeric composite materials for radiation shielding: a review. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2021, 19, 2057–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagi, F.S. The History of Dental Radiology: A Review. History 2023, 141. [Google Scholar]

- Gunderman, R. (2016). On the 120th anniversary of the X-ray, a look at how it changed our view of the world. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/on-the-120th-anniversary-of-the-x-ray-a-look-at-how-it-changed-our-view-of-the-world-50154.

- Molteni, R. The way we were (and how we got here): fifty years of technology changes in dental and maxillofacial radiology. Dentomaxillofacial Radiology 2020, 20200133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molteni, R. The way we were (and how we got here): fifty years of technology changes in dental and maxillofacial radiology. Dentomaxillofacial Radiology 2020, 20200133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.V.; Baptista, L.; Luís, H.; Assunção, V.; Araújo, M.; Realinho, V. Machine Learning in X-ray diagnosis for Oral Health: A Review of Recent progress. Computation 2023, 11, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, J.; Yu, Y.; Li, X.; Shi, K.; Zhang, F.; Yu, F.; Shi, K.; Sun, Z.; Lin, N.; Zheng, Y. Artificial intelligence in the diagnosis of dental diseases on panoramic radiographs: a preliminary study. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdelyi, R.; Duma, V.; Sinescu, C.; Dobre, G.M.; Bradu, A.; Podoleanu, A. Dental diagnosis and treatment assessments: between X-rays radiography and optical coherence tomography. Materials 2020, 13, 4825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, R.; Bornstein, M.M.; Yeung, W.K.A.; Montalvao, C.; Colsoul, N.; Parker, Q.A. (2019). Facts and fallacies of radiation risk in dental radiology.

- Hennig, C.; Schüler, I.M.; Scherbaum, R.; Buschek, R.; Scheithauer, M.; Jacobs, C.; Mentzel, H. Frequency of dental X-ray diagnostics in children and adolescents: What is the radiation exposure? Diagnostics 2023, 13, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clement, C.H.; Ruehm, W.; Harrison, J.; Applegate, K.E.; Cool, D.; Larsson, C.; Cousins, C.; Lochard, J.; Bouffler, S.; Cho, K.; Kai, M.; Laurier, D.; Liu, S.; Рoманoв, C.A. Keeping the ICRP recommendations fit for purpose. Journal of Radiological Protection 2021, 41, 1390–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuieng, R.J.; Cartmell, S.H.; Kirwan, C.C.; Sherratt, M.J. The effects of ionising and Non-Ionising electromagnetic radiation on extracellular matrix proteins. Cells 2021, 10, 3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Huang, B.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Tang, X.; Shi, Y. Interactions between electromagnetic radiation and biological systems. iScience 2024, 109201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahani, R.; Dixit, A. A comprehensive review on zinc oxide bulk and nanostructured materials for ionizing radiation detection and measurement applications. Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing 2022, 151, 107040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Salihi, A.; Al-Saedi, A.; Abdullah, K.; Safaa, M.; Sikhi, B.; Alaa, T. Review: Dosimetry in Dental Radiology. Kirkuk University Journal-Scientific Studies 2021, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storozynsky, Q.; Hitt, M.M. The impact of Radiation-Induced DNA damage on CGAS-STING-Mediated immune responses to cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 8877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L. (2019). Factors modifying cellular response to ionizing radiation (Doctoral dissertation, Department of Molecular Bioscience, The Winner-Gren Institute, Stockholm University).

- Simmarasan, M.; Mohan, K.R.; Vakayil, A. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of radiation protection safety measures among dental students in a dental college. Journal of Dental Research and Reviews 2023, 10, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdufi, I.; Cfarku, F.; Shyti, M. Occupational radiation exposure for dental radiation workers and diagnostic radiology workers in Albania. International Conference on Pioneer and Innovative Studies 2023, 1, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavides, E.; Krecioch, J.R.; Connolly, R.T.; Allareddy, T.; Buchanan, A.; Spelic, D.; O’Brien, K.K.; Keels, M.A.; Mascarenhas, A.K.; Duong, M.; Aerne-Bowe, M.J.; Ziegler, K.M.; Lipman, R.D. Optimizing radiation safety in dentistry. The Journal of the American Dental Association 2024, 155, 280–293e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingler, S.; Biel, P.; Tschanz, M.; Schulze, R. CBCTs in a Swiss university dental clinic: a retrospective evaluation over 5 years with emphasis on radiation protection criteria. Clinical Oral Investigations 2023, 27, 5627–5636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoul Tohidnia, M.; Rasool, A.; Fatemeh, A.; Rahimi, S.A.; Neda, A.; Hosna, S. EVALUATION OF RADIATION PROTECTION PRINCIPLES OBSERVANCE IN DENTAL RADIOGRAPHY CENTERS (WEST OF IRAN): CROSS-SECTIONAL STUDY. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 2020, 190, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rijken, J.; Jeffries, C.; Baldock, C. Radiation protection in radiotherapy is too conservative. Physical and Engineering Sciences in Medicine 2021, 44, 607–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, S.I.; Kamboj, S. Applying ALARA Principles in the Design of New Radiological Facilities. Health Physics 2022, 122, 452–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frane, N.; Bitterman, A. Radiation Safety and Protection. [Updated 2023 May 22]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557499/.

- Alvandi, M.; Javid, R.N.; Shaghaghi, Z.; Farzipour, S.; Nosrati, S. An in-depth analysis of the adverse effects of ionizing radiation exposure on cardiac catheterization staffs. Current Radiopharmaceuticals 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engström, A.; Isaksson, M.; Larsson, P.; Lundh, C.; Båth, M. Lead aprons and thyroid collars: to be, or not to be? Journal of Radiological Protection 2023, 43, 031516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Federal Guidance Report No. 14: Radiation Protection Guidance for Diagnostic and Interventional X-ray Procedures | US EPA. (2024, January 11). US EPA. https://www.epa.gov/radiation/federal-guidance-report-no-14-radiation-protection-guidance-diagnostic-and-interventional.

- Lakhwani, O.; Dalal, V.; Jindal, M.; Nagala, A. Radiation protection and standardization. Journal of Clinical Orthopedics and Trauma 2019, 10, 738–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, S.M.; Abdelsalam, N.; Hashem, N.; Ibrahim, B.A. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Radiation Safety among Dentists in Ismailia City, Egypt. Journal of High Institute of Public Health 2024, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- California Dental Association. (2023, September 28). Radiation safety in dental practice: a study guide. CDA. https://www.cda.org/Home/Resource-Library/Resources/radiation-safety-in-dental-practice-a-study-guide.

- University of Washington School of Dentistry. (2023, August 11). Radiation Safety Policy - UW School of Dentistry. UW School of Dentistry. https://dental.washington.edu/policies/clinic-policy-manual/radiation-safety/.

- Mah, E.; Ritenour, E.R.; Yao, H. A review of dental cone-beam CT dose conversion coefficients. Dentomaxillofacial Radiology 2021, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Physics, V. (2022, May 20). X-rays and radiation safety principles in dentistry. Versant Medical Physics and Radiation Safety. https://www.versantphysics.com/2022/05/20/dental-xrays/.

- Panwar, A.; Gupta, S.; Kamarthi, N.; Malik, S.; Goel, S.; Sharma, A. Awareness of radiation protection among dental practitioners in UP and NCR region, India: A questionnaire-based study. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology 2022, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, G.C.; Rocha, T.G.; De Lima Azeredo, T.; De Castro Domingos, A.; Visconti, M.A.; Villoria, E.M. Hand-held dental X-ray device: Attention to correct use. Imaging Science in Dentistry 2023, 53, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grischke, J.; Johannsmeier, L.; Eich, L.; Griga, L.; Haddadin, S. Dentronics: Toward robotics and artificial intelligence in dentistry. Dental Materials 2020, 36, 765–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Watanabe, M.; Ichikawa, T. Robotics in Dentistry: A Narrative review. Dentistry Journal 2023, 11, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Q.; Guo, S.; Zhang, X. Radiation shielding polymer composites: Ray-interaction mechanism, structural design, manufacture and biomedical applications. Materials & Design 2023, 233, 112253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).