1. Introduction

In clinical trials before Phase III, efficacy is generally evaluated using the objective response rate (ORR) [

1], based on the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST)

2 in almost all solid tumor fields except brain tumors. This method was reported to be used in over 90% of Phase II trials to evaluate efficacy [

3], serving as a surrogate marker [

4]. However, due to the unique characteristics of brain tumors, such as glioblastoma, challenges remain regarding the appropriateness of RECIST for evaluating the surrogate response rate of brain tumors [

3,

5]. Therefore, various efficacy endpoint settings are employed in Phase I and II trials for brain tumors [

3,

5,

6]. Currently, no comprehensive reports exist to guide this issue. We focused on the status of efficacy evaluation methods that differ from those used for other solid tumors, owing to the unique characteristics of brain tumors. Glioblastoma has one of the poorest prognoses for brain tumors [

7,

8,

9]. Therefore, the development of both treatment methods and appropriate evaluation strategies has been necessary. We focused on glioblastoma and previously studied phase II clinical trials conducted between fiscal year (FY) 2017 and 2019, publishing our initial findings in 2021 [

3]. However, clinical trial methodologies have likely evolved in recent years. Therefore, we studied phase II clinical trials initiated over three years from FY2020 to FY2022, analyzing changes and past influences on efficacy endpoints settings.

2. Materials and Methods

Clarivate’s Cortellis

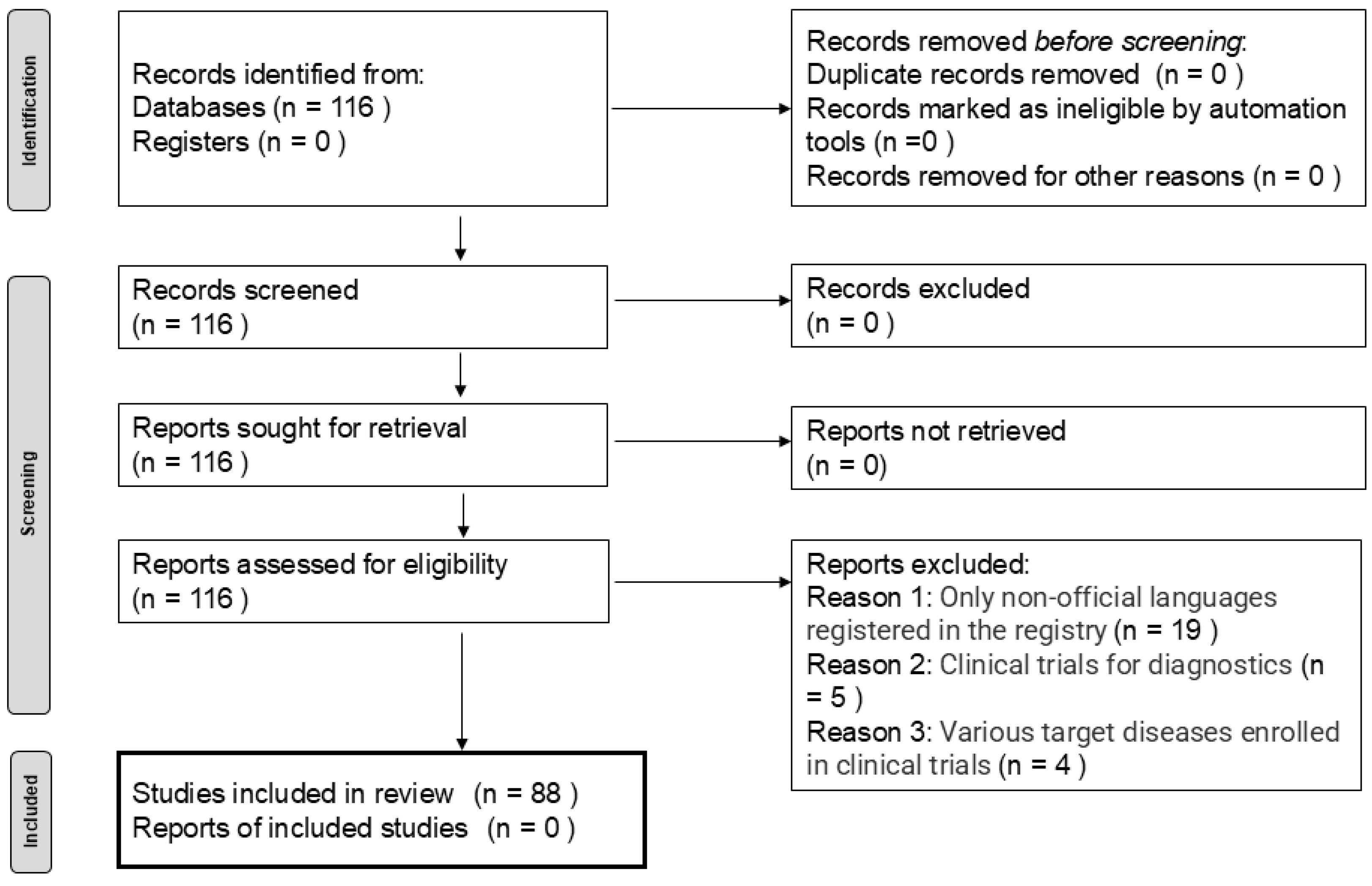

TM Clinical Trial Intelligence was used to survey recent trends in efficacy evaluations in Phase II clinical trials for glioblastoma. Regarding the inclusion or exclusion criteria, a database search using the terms “glioblastoma,” “interventional study,” and “Phase II trials” for the period of April 1, 2020, to March 31, 2023, was performed. This search identified 116 Phase II trials involving glioblastomas. According to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses 2020 statement [

10], we planned to identify and screen trials by excluding certain studies based on specific criteria. Subsequently, the characteristics of the included trials—such as the target patient segment, types of treatment, region, organization, and other relevant factors—were summarized. Trial design characteristics were also evaluated.

The primary purpose of this study was to analyze the recent trends in efficacy endpoints and factors affecting Phase II clinical trials for glioblastoma. Therefore, we first analyzed the primary endpoints (PEs) and secondary endpoints (SEs) in the included clinical trials. Second, we analyzed the clinical trial design for efficacy evaluation, considering not only PEs but also overall efficacy, including both primary and SEs. Third, the trial designs for efficacy endpoints were analyzed and compared with our previous dataset between FY 2017

–2020 [

3].

For baseline variables, summary statistics were calculated using frequencies and proportions for categorical data and medians, means, and standard deviations for continuous variables. All analyses were conducted using JMP version 10.0.0 (SAS). The Wilcoxon test was used to analyze continuous variables, and Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze categorical data. A p-value <0.050 was considered significant for all statistical tests.

3. Results

Among the 116 trials identified, 28 were excluded: 19 due to the enrollment registry language was not English, five were diagnostic trials, and four were excluded because they did not evaluate anti-tumor efficacy (

Figure 1). The background information of the remaining 88 trials is summarized in

Table 1. The target patient segment of the 88 trials consisted of half newly diagnosed patients and half recurrent patients. The largest proportion of these trials tested pharmaceutical products, followed by combination therapies, bioproducts, medical devices, radiotherapy, supplements, and treatment procedures. Most of the studies were conducted in the United States, followed by China. Most studies were conducted in academic settings, followed by collaboration between academia and companies, companies alone, collaborations between academia and the government, and the government alone. The characteristics of the trial design are presented in

Table 2. The median number of trial arms was one, with a maximum of four. The majority of trials had a single study site, with a maximum of 545 sites. The median trial duration was 38 months, ranging from 8 to 118 months. The median enrollment of subjects in each trial was 39 patients, ranging from one to 640 patients.

In all 88 trials, a total of 101 primary efficacy endpoints were identified. The median number of efficacy PEs was one (range: 0–7): 12 trials had no efficacy PE, 60 trials had one efficacy PE, 12 trials had two, two trials had three, one trial had four, and one trial had seven efficacy PEs. The items for all efficacy PEs are summarized in

Table 3-a. Progression-free survival (PFS), Overall Survival (OS), and PFS rates were approximately 20%, hematological marker/tumor cell 13 %, OS rate 11 %, and ORR 7%. The estimation methods for ORR included the Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology (RANO) [

11] 6 and the Immunotherapy Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology (iRANO) [

12]. Conversely, a total of 209 SEs were found to have efficacy. The median number of efficacy SEs was three (range: 1–12): two trials had 12 SEs, one trial had 11, one trial had eight, eight trials had seven, six trials had six, six trials had five, 14 trials had four, 15 trials had three, 13 trials had two, and 12 trials had one. The items for all efficacy SEs are summarized in

Table 3-b. OS was the most common outcome (approximately 15%), followed by PFS, quality of Life, and ORR. The estimated ORR was 15 for RANO, eight for iRANO, two for RECIST, one for other methods, and six were not available. Regarding the clinical trial design for efficacy endpoints (

Table 4-a), multiple efficacy endpoints were included in 32% of trials; however, ORR was set as an efficacy endpoint in only 8% of the trials. Conversely, the time-to-event (TTE) outcomes were included in three-quarters of the trials, with the control arm present in 18% of trials. Regarding efficacy assessment, including both efficacy PEs and SEs (

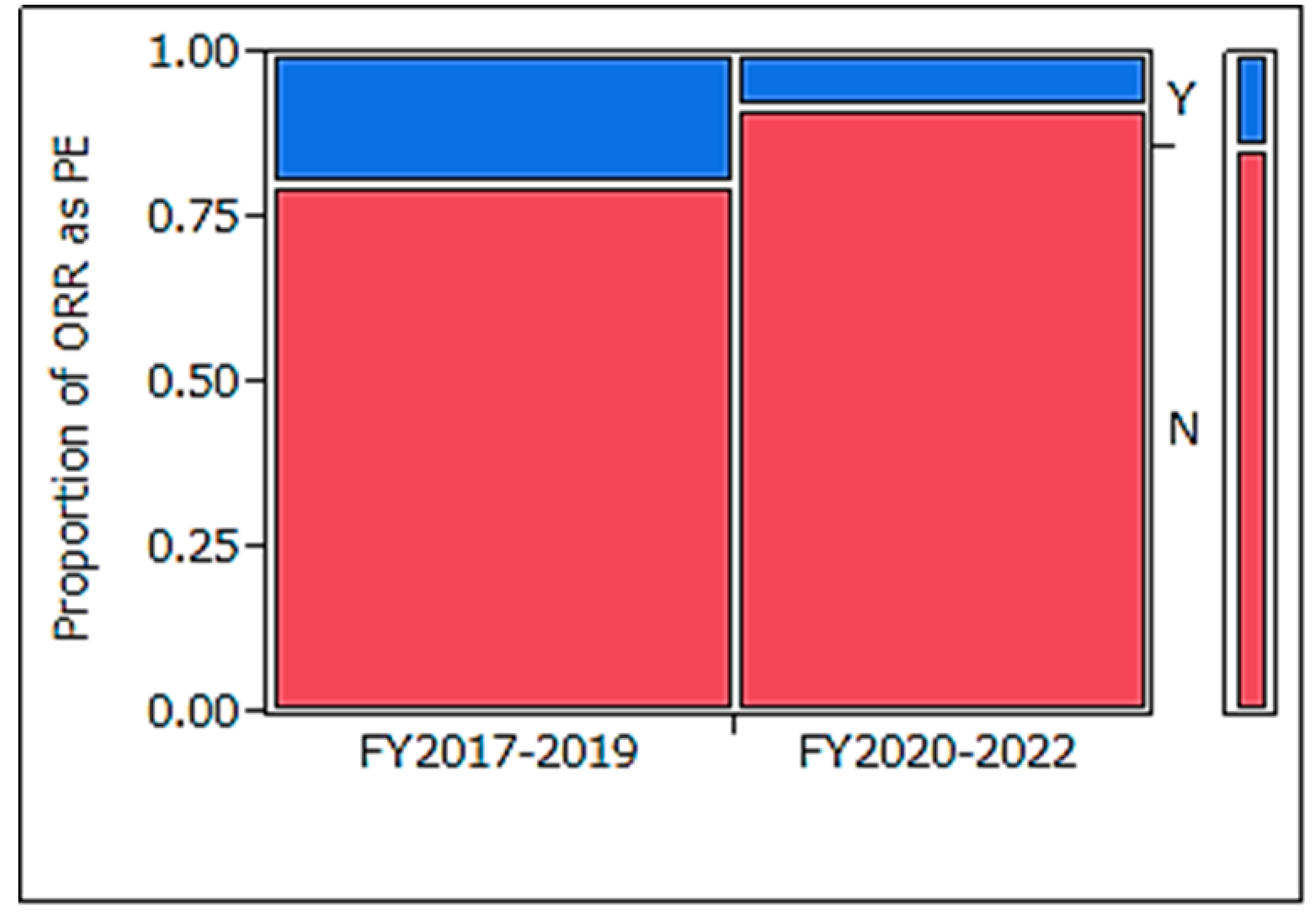

Table 4-b), multiple endpoints were included in 99% of trials, ORR was set in approximately half of the trials, TTE outcomes were set in 92% of trials, and control arms were present in only 22% of trials. Compared to clinical trials initiated in FY2017–2019 (

Table 5), those conducted in FY2020–2022 demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in ORR usage for PE (

Figure 2: p = 0.022).

4. Discussion

In the analysis of trials in FY2020–2022, the PE setting was highly variable; PFS, OS, and PFS rates were approximately 20%; hematological marker/tumor cells, 13%; OS rate, 11%; and ORR, 7%. Furthermore, a greater variety of efficacy endpoints were observed in SEs. Clinical trial designs for the efficacy of Pes and PEs + SEs included multiple efficacy endpoints in 32% and 99% of trials, respectively, with ORR being set as an efficacy endpoint in only 8% and 45% of trials, respectively. When examining the overall efficacy endpoints of PE and SEs, many trials had multiple efficacy endpoints. TTE outcomes were included in 72% and 92% of clinical trials, while control arms were present in only 18% and 22% of trials, respectively. PE types have become increasingly diverse in recent years, with a significant decrease in the proportion of ORRs defined as PEs. In comparison with clinical trials conducted between FY2017–2019 and FY2020–2022, those in FY2020–2022 were significantly less likely to set ORR as a PE (p = 0.022).

4.1. Were endpoint Settings Affected by the Study Design of the Trial?

Previously, the uniqueness of brain tumor clinical trials was highlighted: target lesions after standard surgical resection are generally irregular due to anatomic limitations [

3], image modifiers such as pseudoprogression [

5], or radiation necrosis [

13], following standard multidisciplinary treatment. Additional hurdles include diverse tumor classifications

14 and small sample sizes due to the rarity of these conditions [

15,

16]. Our research into clinical trials conducted in FY2020–2022 revealed the use of unique efficacy evaluation methods significantly different from those in other solid tumor fields. Therefore, we tried to identify potential factors relevant to the setting of efficacy endpoints in clinical trials (

Table 6).

4.1.1. Type of Clinical Trial Item

The settings of Phase II clinical trials of products previously approved for glioblastoma included a high number of pharmaceutical drugs, numerous studies targeting recurrent glioblastoma, predominantly open-label and uncontrolled studies, with PFS or OS rates frequently used as endpoints [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Regarding the type of clinical trial item, we examined whether the trial item in our study was pharmaceutical only, which led to observable differences (

Table 6-a). The number of primary efficacy endpoints was slightly higher in drug trials (p = 0.053); however, the number of SEs did not differ significantly between the two groups (p = 0.13). The rates of ORR set as the PE were low, at 8% for both groups (p = 1.00), and remained under 50% when including SEs (p = 1.00). The establishment of efficacy endpoints for TTE showed high rates for both PEs at 70% (p = 0.48) and for SEs at > 90% (p = 0.48). In general, a few differences were observed in efficacy evaluation settings depending on the investigational product.

4.1.2. Target Patient Segment

Previous regulatory science studies have shown that in Phase II clinical trials targeting glioblastoma, ORR was the PE, with rates of 4% for newly diagnosed glioblastoma and 39% for recurrent glioblastoma, indicating a tendency for ORR to be more prevalent in clinical trials targeting recurrent glioblastoma [

3]. In this study, regarding the factor of target patient segment (newly diagnosed vs. recurrent;

Table 6-b), the number of primary efficacy endpoints was significantly higher in recurrent glioblastoma (p = 0.046). ORR rates were higher for recurrent glioblastoma (0% vs. 17%; p = 0.050), with a significantly higher overall efficacy assessment, including PE and SE (27% vs. 64%; p = 0.0014). Regarding the establishment of efficacy endpoints for TTE, the rates were not statistically different between the PE group (p = 0.33) and the SE group (p = 0.21). There was a statistically significant difference in the number of PEs for recurrent glioblastoma, with ORR more frequently used as an efficacy evaluation compared to newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Various factors may explain why ORR is set as both a primary endpoint and an SE in recurrent cases compared to newly diagnosed cases. The following hypotheses were considered: pseudoprogression [

5] and radiation necrosis [

13], which can occur after initial standard treatment, may be difficult to define recurrence using imaging evaluation based on inclusion criteria. Since the initial standard treatment involves surgical removal, imaging evaluation may be difficult. However, as surgery is often not performed after recurrence, imaging evaluation may be easier in recurrent cases than in newly diagnosed cases. Further investigations are required to clarify these findings.

4.1.3. Trial Design: Randomized-Double Blinded Clinical Trial or Not

In past Phase II trials of approved drugs, open-label single-arm trials were commonly used [

18,

19,

20,

21]. No regulatory science studies have examined differences in endpoint settings due to differences in clinical trial designs. Regarding trial design (randomized double-blind clinical trial;

Table 6-c), the number of primary efficacy endpoints was slightly higher in randomized double-blind trials (p = 0.10), but the number of SEs was significantly lower (p = 0.016). Regarding ORR, there was no difference in its frequency as PE (p = 1.00); however, the overall evaluation, including SEs, tended to be higher in non-double-blind studies (p = 0.070). There was no difference in TTE endpoints, either for PE (p = 1.00) or the overall evaluation, including SEs (p = 0.49). The number of SEs was significantly lower in randomized double-blind clinical trials (p = 0.016). The frequency of ORR was higher in non-double-blind studies across all efficacy evaluations, including SEs (p = 0.070).

4.2. Why is ORR Being Used as a PE Less Frequently Than in the Past?

In our study, the frequency of using ORR as a PE significantly reduced compared to the previous study, while hematological and tumor indices were relatively high (13%), and the PFS and PFS rates increased. Anticancer drug development has changed dramatically in recent years, largely due to the success of molecularly targeted drugs, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors and therapies targeting important driver mutations. Anticancer guidelines state that although RECIST-based response assessment criteria remain the standard for solid tumors, appropriate criteria should be used for each investigational drug following scientific advances [

1]. It is possible that the changes in the developmental environment described earlier have contributed to this shift.

What are the future trends in evaluation methods? One possible trend is the adoption of the new RANO criteria, published as a revised version called RANO 2.0 [

22], for the clinical evaluation of gliomas. However, challenges have emerged in interpreting the differences between the old and new versions of the RANO evaluation methods. Changes in the clinical evaluation of brain tumors are expected to continue, and further research will be conducted to address these developments.

4.3. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

This study uniquely analyzed recent trends in efficacy endpoint and factors affecting phase II clinical trials of glioblastoma. However, this study had some limitations. First, it relied on a single database, as trials in languages other than English were excluded. Second, we could not compare our results with those of other studies because there was little supporting literature available. Therefore, internal evidence is being continuously accumulated. We also plan to follow up on the trials included in this study to track the percentage of treatments (drugs) that progressed from phase II to III and the efficacy endpoints used in those clinical trials. Additionally, new World Health Organization brain tumor guidelines14 have been issued; therefore, evidence based on this classification should be accumulated for future analyses. Glioblastomas are unique in many ways; biological factors, such as the blood-brain barrier and the unique tumor and immune microenvironment, represent significant challenges in the development of novel therapies. Innovative clinical trial designs incorporating biomarker-enrichment strategies are needed to improve the outcomes of patients with glioblastoma.9 Future studies may need to explore methods for individualized efficacy evaluation based on new classifications, such as gene mutations.

5. Conclusions

Recently, the PE settings have been highly variable; furthermore, SEs exhibited a greater variety of efficacy endpoints, with multiple efficacy endpoints and ORR setting as efficacy endpoints in only 8% and 45% of cases, respectively. PE types have become increasingly diverse in recent years. In comparison with clinical trials between FY2017–2019, those in FY2020–2022 were revealed to have a statistically lower frequency of ORR being set as a PE. ORR rates tended to be high in recurrent glioblastomas. The results of this study may influence more appropriate efficacy evaluation in future phase II clinical trials targeting glioblastoma. In addition, the new WHO classification was revised and the new RANO classification had been recently proposed, so we believe that data on ORR should at least be included as a SE, but continued discussion is essential.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.W. and M.M.; methodology, S.W.; software, S.W.; validation, N.S., M.Y. and K.H.; formal analysis, S.W.; investigation, S.W.; resources, S.W.; data curation, M.M. and K.N.; writing—original draft preparation, S.W.; writing—review and editing, All authors.; visualization, S.W.; supervision, Y.A. and E.I.; project administration, M.M.; funding acquisition, S.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (grant number JP24mk0101235).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

FY - Fiscal Year

PFS - Progression-Free Survival

OS - Overall Survival

PE - Primary Endpoint

SE - Secondary Endpoint

ORR - Objective Response Rate

RECIST - Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors

RANO - Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology

iRANO - Immunotherapy Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology

TTE - Time-to-Event

JMP - (Software used for statistical analysis, developed by SAS Institute)

SAS - Statistical Analysis System

References

- Minami, H.; Kiyota, N.; Kimbara, S.; Ando, Y.; Shimokata, T.; Ohtsu, A.; Fuse, N.; Kuboki, Y.; Shimizu, T.; Yamamoto, N.; et al. Guidelines for clinical evaluation of anti-cancer drugs. Cancer Sci. 2021, 112, 2563–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Therasse, P.; Eisenhauer, E.A.; Verweij, J. RECIST revisited: a review of validation studies on tumour assessment. Eur J Cancer. 2006, 42, 1031–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, S.; Nonaka, T.; Maeda, M. Fact-finding research on efficacy endpoints in recent Phase II clinical trials targeting glioblastoma. Pharm Dev Regul Sci. (Japanese article with English abstract). 2021, 52, 358–367. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, R.F.; John, H.P. Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints in clinical trials. Stat Med. 2012, 31, 2973–84. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, S.; Nonaka, T.; Maeda, M.; Sugii, N.; Hashimoto, K.; Takano, S.; Koyanagi, T.; Yamada, M.; Arakawa, Y.; Ishikawa, E. Efficacy endpoints in phase II clinical trials for meningioma: an analysis of recent clinical trials. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2023, 57, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinya, W.; Takahiro, N.; Makoto, M.; Masanobu, Y.; Narushi, S.; Koichi, H.; Shingo, T.; Tomoyoshi, K.; Yoshihiro, A.; Eiichi, I. Recent Status of Phase I Clinical Trials for Brain Tumors: A Regulatory Science Study of Exploratory Efficacy Endpoints. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2024, 58, 655–662. [Google Scholar]

- Shergalis, A.; Bankhead, A.; Luesakul, U.; Muangsin, N.; Neamati, N. Current Challenges and Opportunities in Treating Glioblastoma. Pharmacol Rev. 2018, 70, 412–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoru, O.; Erwin, G.V. Overcoming therapeutic resistance in glioblastoma: the way forward. J Clin Invest. 2017, 127, 415–426. [Google Scholar]

- Aaron, C.T.; David, M.A.; Giselle, Y.L.; Malinzak, M.; Friedman, H.S.; Khasraw, M. Management of glioblastoma: State of the art and future directions. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020, 70, 299–312. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, P.Y.; Macdonald, D.R.; Reardon, D.A.; Cloughesy, T.F.; Sorensen, A.G.; Galanis, E.; Degroot, J.; Wick, W.; Gilbert, M.R.; Lassman, A.B.; et al. Updated response assessment criteria for high-grade gliomas: response assessment in neuro-oncology working group. J Clin Oncol. 2010, 28, 1963–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada, H.; Weller, M.; Huang, R.; Finocchiaro, G.; Gilbert, M.R.; Wick, W.; Ellingson, B.M.; Hashimoto, N.; Pollack, I.F.; Brandes, A.A.; et al. Immunotherapy response assessment in neuro-oncology: a report of the RANO working group. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, e534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyatake, S.; Nonoguchi, N.; Furuse, M.; Yoritsune, E.; Miyata, T.; Kawabata, S.; Kuroiwa, T. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of radiation necrosis in the brain. Neurol Med Chir. 2015, 55, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Wesseling, P.; Brat, D.J.; Cree, I.A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Hawkins, C.; Ng, H.K.; Pfister, S.M.; Reifenberger, G.; et al. The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Neuro Oncol. 2021, 23, 1231–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brain Tumor Registry of Japan (2005-2008). Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2017, 57, 9–102. [CrossRef]

- Bondy, M.L.; Scheurer, M.E.; Malmer, B.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S.; Davis, F.G.; Il'yasova, D.; Kruchko, C.; McCarthy, B.J.; Rajaraman, P.; Schwartzbaum, J.A.; et al. Brain tumor epidemiology: consensus from the Brain Tumor Epidemiology Consortium. Cancer. 2008, 113, 1953–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, W.K.; Albright, R.E.; Olson, J.; Fredericks, R.; Fink, K.; Prados, M.D.; Brada, M.; Spence, A.; Hohl, R.J.; Shapiro, W.; et al. A phase II study of temozolomide vs. procarbazine in patients with glioblastoma multiforme at first relapse. Br J Cancer. 2000, 83, 588–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, W.K.; Prados, M.D.; Yaya-Tur, R.; Rosenfeld, S.S.; Brada, M.; Friedman, H.S.; Albright, R.; Olson, J.; Chang, S.M.; O’Neill, A.M.; et al. Multicenter phase II trial of temozolomide in patients with anaplastic astrocytoma or anaplastic oligoastrocytoma at first relapse. Temodal Brain Tumor Group. J Clin Oncol. 1999, 17, 2762–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brada, M.; Hoang-Xuan, K.; Rampling, R.; Dietrich, P.Y.; Dirix, L.Y. Macdonald. D.; Heimans, J.J.; Zonnenberg, B.A.; Bravo-Marques, J.M.; Henriksson. R.; et al. Multicenter phase II trial of temozolomide in patients with glioblastoma multiforme at first relapse. Ann Oncol. 2001, 12, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todo, T.; Ito, H.; Ino, Y.; Ohtsu, H.; Ota, Y.; Shibahara, J.; Tanaka, M. IntratumoraloncolyticherpesvirusG47 for residual or recurrentglioblastoma: a phase2trial. Nat Med. 2022, 28, 1630–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, T.; Nishikawa, R.; Sugiyama, K.; Nonoguchi, N.; Kawabata, N.; Mishima, K.; Adachi, J.I.; Kurisu, K.; Yamasaki, F.; Tominaga, T.; et al. A multicenter phase I/II study of the BCNU implant (Gliadel(®) Wafer) for Japanese patients with malignant gliomas. Neurol. Med.Chir. 2014, 54, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, P.Y.; van den Bent, M.; Youssef, G.; Cloughesy, T.F.; Ellingson, B.M.; Weller, M.; Galanis, E.; Barboriak, D.P.; de Groot, J.; Gilbert, M.R.; et al. RANO 2.0: Update to the Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology Criteria for High- and Low-Grade Gliomas in Adults. J Clin Oncol. 2023, 41, 5187–5199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).