Submitted:

14 January 2025

Posted:

16 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

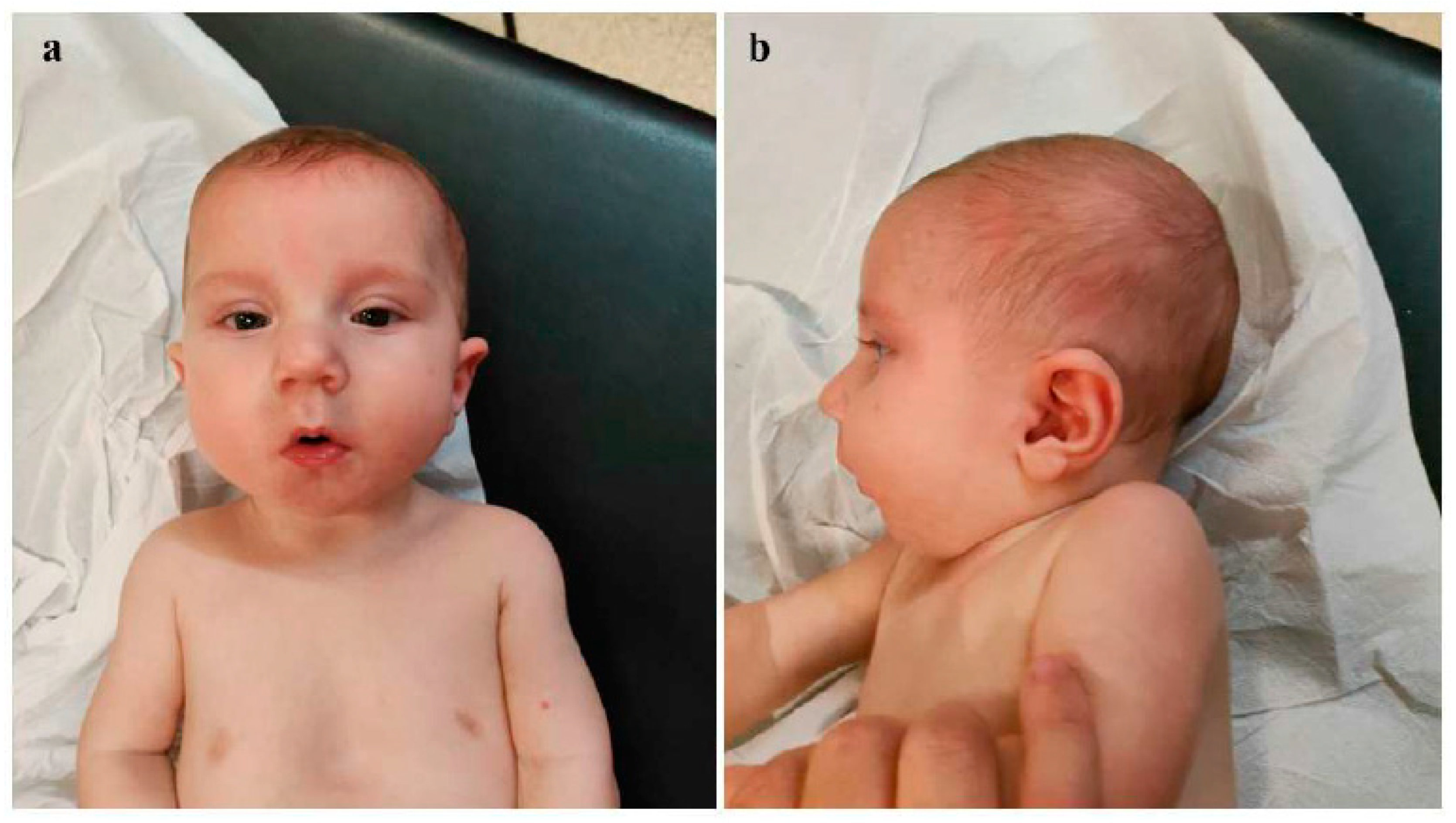

Background: Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) represents one of the most critical neonatal emergencies, whose timely recognition and appropriate management are essential to ensure patient survival. Genetic investigations play a crucial role for accurate diagnostic assessment, especially in those cases associated with other congenital defects and/or dysmorphic features. Interstitial deletions of chromosome 1q are rare, with about 30 cases reported in the literature. The phenotypical features of the affected subjects described so far include microcephaly, pre- and postnatal growth retardation, psychomotor delay, ear anomalies, brachydactyly, in addition to small hands and feet and rarely congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH). Here, we report on a neonate with CDH, dysmorphic features, and multiple midline anomalies, in whom array-comparative genomic hybridization (a-CGH) analysis allowed the identification of an interstitial deletion of the long arm of chromosome 1. Case presentation: The proband is a male infant, born late preterm at 36+1 weeks, with prenatal diagnosis of congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) for which parents refused further genetic investigations. At birth physical examination revealed dysmorphic features and multiple midline anomalies, including cleft palate, pectus excavatum, and ostium primum type atrial septal defect, in addition to hypotonia. Cranial ultrasound showed poor gyral development. a-CGH identified a deletion of approximately 12 Mb on the long arm of chromosome 1, within the region 1q31.1-q32.1, thereafter documented as de novo. On the fourth day of life, he underwent surgical correction of CDH. At about one month of age, the infant was discharged and enrolled in a multidisciplinary follow-up, during which an impaired growth has been evidenced. During the last neuropsychiatric evaluation at the age of 8 months, the child showed mild hypotonia and immature manual exploration. Head control was present but inconsistent. Trunk control was not yet developed, and lower limb positioning exhibited flexion, external rotation and varus attitude of feet. He does not show any further clinical anomalies, and laboratory tests as well as US multiorgan and neurosensorial evaluations do not put in evidence other abnormalities to date. The surgical correction of cleft palate is currently planned to be performed at one year of age. Conclusions: The few cases of chromosome 1q deletions reported to date, along with the clinical and genetic profile of the present neonate, point out that 1q deletions should be considered within the context of "interstitial 1q deletion syndrome". Comparing our case with those described in previous studies, the involved genomic regions and the phenotypic traits are partially overlapping, although the clinical picture of the present patient is among the few ones including congenital diaphragmatic hernia within the phenotypical spectrum. A more extensive comparative analysis of a larger number of patients with similar genetic profiles may allow for a more precise clinical and genomic characterization of this rare syndrome, and for genotype-phenotype correlations.

Keywords:

Background

Case Presentation

Discussion

Conclusions

References

- Chatterjee, D.; Ing, R.J.; Gien, J. Update on Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia. Anesth Analg. 2020, 131, 808–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehollin-Ray, A.R. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Pediatr Radiol. 2020, 50, 1855–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, G.; Antona, V.; Schierz, M.; Vecchio, D.; Piro, E.; Corsello, G. Esophageal atresia and Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome in one of the naturally conceived discordant newborn twins: first report. Clin Case Rep. 2018, 6, 399–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedrick, H.L.; Adzick, N.S. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) in the neonate: Clinical features and diagnosis. In: UpToDate, Post TW (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA.

- Scott, D.A.; Gofin, Y.; Berry, A.M.; Adams, A.D. Underlying genetic etiologies of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Prenat Diagn. 2022, 42, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccione, M.; Serra, G.; Sanfilippo, C.; Andreucci, E.; Sani, I.; Corsello, G. A new mutation in EDA gene in X-linked hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia associated with keratoconus. Minerva Pediatr. 2012, 64, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Serra, G.; Corsello, G.; Antona, V.; D'Alessandro, M.M.; Cassata, N.; Cimador, M.; Giuffrè, M.; Schierz, I.A.M.; Piro, E. Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease: case report of a newborn with rare PKHD1 mutation, rapid renal enlargement and early fatal outcome. Ital J Pediatr. 2020, 46, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valutazione Antropometrica neonatale. Riferimento carte INeS. http://www.inescharts.com.

- Goede, J.; Hack, W.W.; Sijstermans, K.; van der Voort-Doedens, L.M.; Van der Ploeg, T.; Meij-de Vries, A.; Delemarre-van de Waal, H.A. Normative values for testicular volume measured by ultrasonography in a normal population from infancy to adolescence. Horm Res Paediatr. 2011, 76, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, S.L.; Edgar, J.C.; Ford, E.G.; Adgent, M.A.; Schall, J.I.; Kelly, A.; Umbach, D.M.; Rogan, W.J.; Stallings, V.A.; Darge, K. Size of testes, ovaries, uterus and breast buds by ultrasound in healthy full-term neonates ages 0-3 days. Pediatr Radiol. 2016, 46, 1837–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, Grody WW, Hegde M, Lyon E, Spector E, Voelkerding K, Rehm HL; ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015, 17, 405–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Child growth standards. 2021. https://www.who.int/tools/child-growth-standards/standards.

- Milani, D.; Bedeschi, M.F.; Iascone, M.; Chiarelli, G.; Cerutti, M.; Menni, F. De novo deletion of 1q31.1-q32.1 in a patient with developmental delay and behavioral disorders. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2012, 136, 167–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyder, Z.; Fairclough, A.; Douzgou, S. Chromosome 1q31.2q32.1 deletion in an adult male with intellectual disability, dysmorphic features and obesity. Clin Dysmorphol. 2019, 28, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, J.; Zombor, M.; Máté, A.; Sztriha, L.; Waters, J.J. De Novo Interstitial Microdeletion at 1q32.1 in a 10-Year-Old Boy with Developmental Delay and Dysmorphism. Case Rep Genet. 2016, 2016, 2501741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serra, G.; Antona, V.; Giuffrè, M.; Piro, E.; Salerno, S.; Schierz, I.A.M.; Corsello, G. Interstitial deletions of chromosome 1p: novel 1p31.3p22.2 microdeletion in a newborn with craniosynostosis, coloboma and cleft palate, and review of the genomic and phenotypic profiles. Ital J Pediatr. 2022, 48, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccione M, Serra G, Consiglio V, Di Fiore A, Cavani S, Grasso M, Malacarne M, Pierluigi M, Viaggi C, Corsello G. 14q13.1-21.1 deletion encompassing the HPE8 locus in an adolescent with intellectual disability and bilateral microphthalmia, but without holoprosencephaly. Am J Med Genet A. 2012, 58, 1427–33. [Google Scholar]

- Piro E, Serra G, Giuffrè M, Schierz IAM, Corsello G. 2q13 microdeletion syndrome: Report on a newborn with additional features expanding the phenotype. Clin Case Rep. 2021, 9, e04289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, G.; Giambrone, C.; Antona, V.; Cardella, F.; Carta, M.; Cimador, M.; Corsello, G.; Giuffrè, M.; Insinga, V.; Maggio, M.C.; Pensabene, M.; Schierz, I.A.M.; Piro, E. Congenital hypopituitarism and multiple midline defects in a newborn with non-familial Cat Eye syndrome. Ital J Pediatr. 2022, 48, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schierz, I.A.M.; Giuffrè, M.; Cimador, M.; D’Alessandro, M.M.; Serra, G.; Favata, F.; Antona, V.; Piro, E.; Corsello, G. Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis masked by kidney failure in a male infant with a contiguous gene deletion syndrome at Xp22.31 involving the steroid sulfatase gene: case report. Ital J Pediatr 2022, 48, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamano, S.; Fukushima, Y.; Yamada, T.; Shimizu, H.; Okuyama, M.; Ito, F.; Maekawa, K. A case of interstitial 1q deletion [46,XY,del(q25q32.1)]. Ann Genet. 1987, 30, 105–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hill, A.D.; Chang, B.S.; Hill, R.S.; Garraway, L.A.; Bodell, A.; Sellers, W.R.; Walsh, C.A. A 2-Mb critical region implicated in the microcephaly associated with terminal 1q deletion syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2007, 143A, 1692–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemming, I.A.; Forrest, A.R.; Shipman, P.; Woodward, K.J.; Walsh, P.; Ravine, D.G.; Heng, J.I. Reinforcing the association between distal 1q CNVs and structural brain disorder: A case of a complex 1q43-q44 CNV and a review of the literature. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2016, 171B, 458–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagamani, S.C.; Erez, A.; Bay, C.; Pettigrew, A.; Lalani, S.R.; Herman, K.; Graham, B.H.; Nowaczyk, M.J.; Proud, M.; Craigen, W.J.; Hopkins, B.; Kozel, B.; Plunkett, K.; Hixson, P.; Stankiewicz, P.; Patel, A.; Cheung, S.W. Delineation of a deletion region critical for corpus callosal abnormalities in chromosome 1q43-q44. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012, 20, 176–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, L.G.; Theisen, A.; Bejjani, B.A.; Ballif, B.C.; Aylsworth, A.S.; Lim, C.; McDonald, M.; Ellison, J.W.; Kostiner, D.; Saitta, S.; Shaikh, T. The discovery of microdeletion syndromes in the post-genomic era: review of the methodology and characterization of a new 1q41q42 microdeletion syndrome. Genet Med. 2007, 9, 607–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della Monica, M.; Lonardo, F.; Faravelli, F.; Pierluigi, M.; Luquetti, D.V.; De Gregori, M.; Zuffardi, O.; Scarano, G. A case of autism with an interstitial 1q deletion (1q23.3-24.2) and a de novo translocation of chromosomes 1q and 5q. Am J Med Genet A. 2007, 143A, 2733–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, L.J.; Noordhoff, M.S.; Huang, C.S.; Chen, K.T.; Chen, Y.R. Proximal deletion of the long arm of chromosome 1: [del(1)(q23-q25)]. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1993, 30, 586–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libotte, F.; Bizzoco, D.; Gabrielli, I.; Tamburrino, C.; Ernandez, C.; Carpineto, L.; D'Aleo, M.P.; Cima, A.; Mesoraca, A.; Cignini, P.; Aloisi, A.; Angioli, R.; Vitale, S.G.; Giorlandino, C. A new case of interstitial 1q 25.3-32.1 deletion: cytogenetic analysis molecular characterization and ultrasound findings. J Prenat Med. 2015, 9, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlSaad, R.; ElMansoury, J.; AlHazzaa, S.A.F.; Dirar, Q.S. Chromosome 1q Terminal Deletion and Congenital Glaucoma: A Case Report. Am J Case Rep. 2020, 21, e918128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cioclu MC, Mosca I, Ambrosino P, Puzo D, Bayat A, Wortmann SB, Koch J, Strehlow V, Shirai K, Matsumoto N, Sanders SJ, Michaud V, Legendre M, Riva A, Striano P, Muhle H, Pendziwiat M, Lesca G, Mangano GD, Nardello R; KCNT2-study group; Lemke JR, Møller RS, Soldovieri MV, Rubboli G, Taglialatela M. KCNT2-Related Disorders: Phenotypes, Functional, and Pharmacological Properties. Ann Neurol. 2023, 94, 332–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson A, Banka S, Stewart H; Genomics England Research Consortium; Robinson H, Lovell S, Clayton-Smith J. Recurrent KCNT2 missense variants affecting p.Arg190 result in a recognizable phenotype. Am J Med Genet A. 2021, 185, 3083–3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, N.; Murakami, H.; Saito, T.; Masuno, M.; Kurosawa, K. Tumor predisposition in an individual with chromosomal rearrangements of 1q31.2-q41 encompassing cell division cycle protein 73. Congenit Anom (Kyoto). 2020, 60, 128–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugawara Y, Kato H, Nagasaki M, Yoshida Y, Fujisawa M, Minegishi N, Yamamoto M, Nangaku M. CFH-CFHR1 hybrid genes in two cases of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. J Hum Genet. 2023, 68, 427–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fei, Z.G.; Zhen, K.; Zhang, F.J.; Liu, P.Y.; Xu, H.Y.; Chen, H.H. Clinical research advances of CFHR5 nephropathy: a recent review. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2023, 27, 9987–10000. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Biswas, A.; Ivaskevicius, V.; Thomas, A.; Oldenburg, J. Coagulation factor XIII deficiency. Diagnosis, prevalence and management of inherited and acquired forms. Hamostaseologie. 2014, 34, 160–6. [Google Scholar]

- Verloes A, Drunat S, Passemard S.. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Gripp KW, Amemiya A, ASPM Primary Microcephaly. 2020 Apr 2. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993–2024.

- Daher, A.; Banjak, M.; Noureldine, J.; Nehme, J.; El Shamieh, S. Genotype-phenotype associations in CRB1 bi-allelic patients: a novel mutation, a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Ophthalmol. 2024, 24, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bergen NJ, Bell KM, Carey K, Gear R, Massey S, Murrell EK, Gallacher L, Pope K, Lockhart PJ, Kornberg A, Pais L, Walkiewicz M, Simons C; MCRI Rare Diseases Flagship; Wickramasinghe VO, White SM, Christodoulou J. Pathogenic variants in nucleoporin TPR (translocated promoter region, nuclear basket protein) cause severe intellectual disability in humans. Hum Mol Genet. 2022, 31, 362–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowcz, S.R.; Featherby, T.J.; Whisstock, J.C.; Bird, P.I. Mice Lacking Brinp2 or Brinp3, or both, exhibit behaviors consistent with neurodevelopmental disorders. Front.Behav. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 196. [Google Scholar]

| Authors | Deletion (breakpoints, GRCh37) | Dysmorphic features | Involved genes | Genetic test | Cardio-vascular system | Respiratory system | Neuropsychomotor profile | Hands and/or feet anomalies | Outcome |

| Milani et al. (2012) [13] | Del 1q 31.1-q32.1 ( 187,437,627-203,015,924) | broad forehead, laterally sparse eyebrows, slightly downward-slanted palpebral fissures, broad and high nasal bridge, hypoplastic nostrils, long philtrum, thin upper lip and slightly protruding lower lip, retroverted ears |

F13B, ASPM, CRB1, PTPRC, PKP1, CDC73, CACNA 1S, TNNT2 |

Array-CGH | n.r. | n.r. | Motor, social and cognitive developmental delay | At age 6 years, normal physical growth parameters; mild motor and cognitive developmental delay, hyperactivity and behavioral disorders. | |

| Hyder et al (2019) [14] |

del 1q 31.2-q32.1(191,590,110-201,139,395) | frontal upsweep, hypertelorism, epicanthic folds, broad nasal bridge, prominent nose, low columella, thin upper lip and everted lower lip, prominent ears, short chin. |

DDX59, ASPM, CRB1, F13B, CDC73, CFHR5, CACNA1S, UCHL5, TROVE2, B3GALT, ZBTB41, CAMSA2, KIF21B, TMEM9 |

Array- CGH | n.r. | n.r. | At birth, hypotonia and feeding difficulties. Subsequently, developmental delay, hyperactivity, aggression, disinhibition, and sleep disturbances. |

Clinodactyly, single palmar crease on left hand, tapering fingers, deep-set small nails. | At 31 years, head circumference 57.4cm (50th–75th centile), height 174.8cm (25th–50th centile) and weight 140.6kg (>99th centile). Downslanting palpebral fissures, broad nasal bridge, low-hanging columella, thin upper lip, thick lower lip, deep-set small nails and tapering fingers. He currently lives independently in a flat with supported living. His main difficulties are with arithmetic and finances, but his memory is good and he is able to read and write independently |

| Carter et al. (2016) [15] |

Del. 1q32.1 (199,985,888 – 203,690,832) |

Long face, narrow jaw, down-slanted palpebral fissures, highly arched eyebrows, low-set ears, thick lower lip. | KDM5B, NAV1, KIF21B, GPR37L, SYT2 | Array-CGH | n.r. | n.r. | Global developmental delay, social skills and language difficulties, reduced IQ. Generalized hypotonia and decreased deep tendon reflexes |

Bilateral clinodactyly of the fifth finger and proximal positioning of the thumb | Neuropsychological evaluation at 7 years of age: full scale IQ of about 50 (Woodcock-Johnson Tests of Cognitive Abilities), difficulties in visual-motor coordination. Significant difficulties with receptive and expressive language; slow improvement in language acquisition. At 10 years, he requires special education and support in everyday life |

| Our patient | Del.1q31.1-q32.1 (187,95,640 – 199,996,777) | Broad and sloping forehead, hypertelorism, wide nasal bridge, bulbous nasal tip, anteverted nares, long and thick philtrum, thin lips, dysplastic auricles with thickened helices, low-set and posteriorly rotated ears, complete cleft palate, microretrognathia. |

CDC73, KCNT2, CFH, CFHR1, CFHR5, F13B, ASPM, CRB1, PTPRC | Array-CGH |

ostium primum-type atrial septal defect |

diaphragmatic hernia | Generalized hypotonia, diminished deep tendon reflexes, reduced primitive reflexes and reactivity, poor cortical gyration, and millimeter-sized cystic lesions in the periventricular white matter |

clinodactyly of the fifth finger | At age 8 months, generalized mild hypotonia. Nearly completely acquired head control, not that of the trunk. In the supine position, tendency towards flexion and external rotation of the lower limbs. Normal muscular trophism, feet in varus attitude. Good manual grip and lively free motor skills. Normally elicitable osteo-tendineous reflexes and Landau reaction, not the Babinski sign. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).