1. Introduction

Aptamers are single-stranded nucleic acids, either ribonucleic acid (RNA) or deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), capable of interacting with various target molecules with high affinity in the pico- to nanomolar range. These molecules offer several advantages, including thermal stability, low toxicity and immunogenicity, straightforward synthesis, and ease of chemical modification [

1,

2]. Additionally, their flexible three-dimensional (3D) structure allows aptamers to fit into the binding pockets of target molecules through hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions. However, unmodified aptamers are hydrophilic and susceptible to nuclease degradation, which can compromise their structure, activity, and shelf life [

3]. To address this, modifications to the oligonucleotide ends, sugar rings, or phosphodiester bonds have been shown to enhance aptamer stability against nucleases [

4].

Conjugating aptamers with antibodies or proteins has been reported to improve binding affinity from nanomolar to picomolar ranges compared to using either aptamers or antibodies alone [

5]. This conjugation technique is widely utilized in biotechnology for applications such as monitoring nanostructures or protein complexes, in vivo visualization, and bioimaging within living cells [

6]. The method used to produce antibody-aptamer conjugates depends on the study's objectives. Site-specific conjugation is used when the aptamer binds to two different epitopes of the target protein. Conversely, random site conjugation is appropriate when the antibody is not directly involved in protein binding and relies on the amine group of amino residues for the conjugation reaction [

7]. In the present study, enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) was employed as a model to conjugate with an ICAM-1-specific aptamer. eGFP is widely used for studying protein localization and function in living cells and animals [

8].

Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1 (ICAM-1) is implicated in the adhesion of infected erythrocytes (IEs) and has been linked to severe malaria. Postmortem examinations of individuals who died from acute malaria in Vietnam confirmed ICAM-1's role in microvascular adhesion [

9]. Immunocytochemical studies further revealed increased ICAM-1 expression in the microvasculature during fatal malaria. Previous research has explored the potential of antibodies as therapeutic agents to block IEs binding to ICAM-1, showing that treatment significantly reduced rolling and sequestration of IEs in the central nervous system using animal models, LPS-primed brain sections, and ICAM-1-transfected cells [

10]. Another study demonstrated that anti-ICAM-1 monoclonal antibodies reduced Plasmodium falciparum binding in in vitro assays with laboratory and patient isolates [

11]. However, antibodies face limitations for therapeutic use and in vivo bioimaging due to high immunogenicity, elevated production costs, variable batch production, suboptimal pharmacokinetics (e.g., cell penetration), and other challenges [

12,

13].

In this study, the random site conjugation method was applied to demonstrate the proof-of-concept for a small protein-DNA aptamer conjugate. This approach enhanced the binding of an isolated ICAM-1-specific aptamer to recombinant human ICAM-1 protein. The isolated aptamer shows potential for further conjugation with other molecules or drugs, paving the way for its application in malaria therapy.

2. Results

2.1. Selection of DNA Aptamers Against Human ICAM-1

The DNA aptamer specific to human ICAM-1 was isolated using protein A-coupled magnetic beads. These beads were utilized to immobilize human IgG1-tagged recombinant human ICAM-1, enabling efficient separation of bound aptamers from unbound ones. A high concentration of the DNA aptamer library (500 pmol) was employed during the first SELEX round to maximize the number of aptamer candidates binding to the target protein. In subsequent rounds, the amount of rhICAM-1-coupled magnetic beads, incubation time, and washing steps were progressively reduced to increase the stringency of aptamer selection (

Table 1). To minimize background amplification, a negative SELEX step was introduced before each cycle. This step used magnetic beads alone to eliminate aptamers binding to the beads or bovine serum albumin (BSA), which could otherwise be amplified as background noise and prolong the selection process. PCR amplification was carefully optimized during each SELEX cycle to prevent the loss of low-abundance DNA candidates after the washing steps. The number of PCR cycles (example as

Supplementary Information 1) was adjusted to avoid over-amplification, which could distort the library composition. In higher SELEX rounds, an increased number of PCR cycles was necessary due to the reduced volume of the selection matrix and a corresponding decrease in aptamer recovery. These additional cycles ensured sufficient PCR product visibility on an agarose gel. To generate single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) for subsequent SELEX cycles, lambda exonuclease digestion was combined with asymmetric PCR (

Supplementary Information 2). The reverse primer was modified with a phosphate group at the 5' end, allowing lambda exonuclease to selectively degrade the phosphorylated strand in the 5' to 3' direction, leaving the non-phosphorylated strand intact.

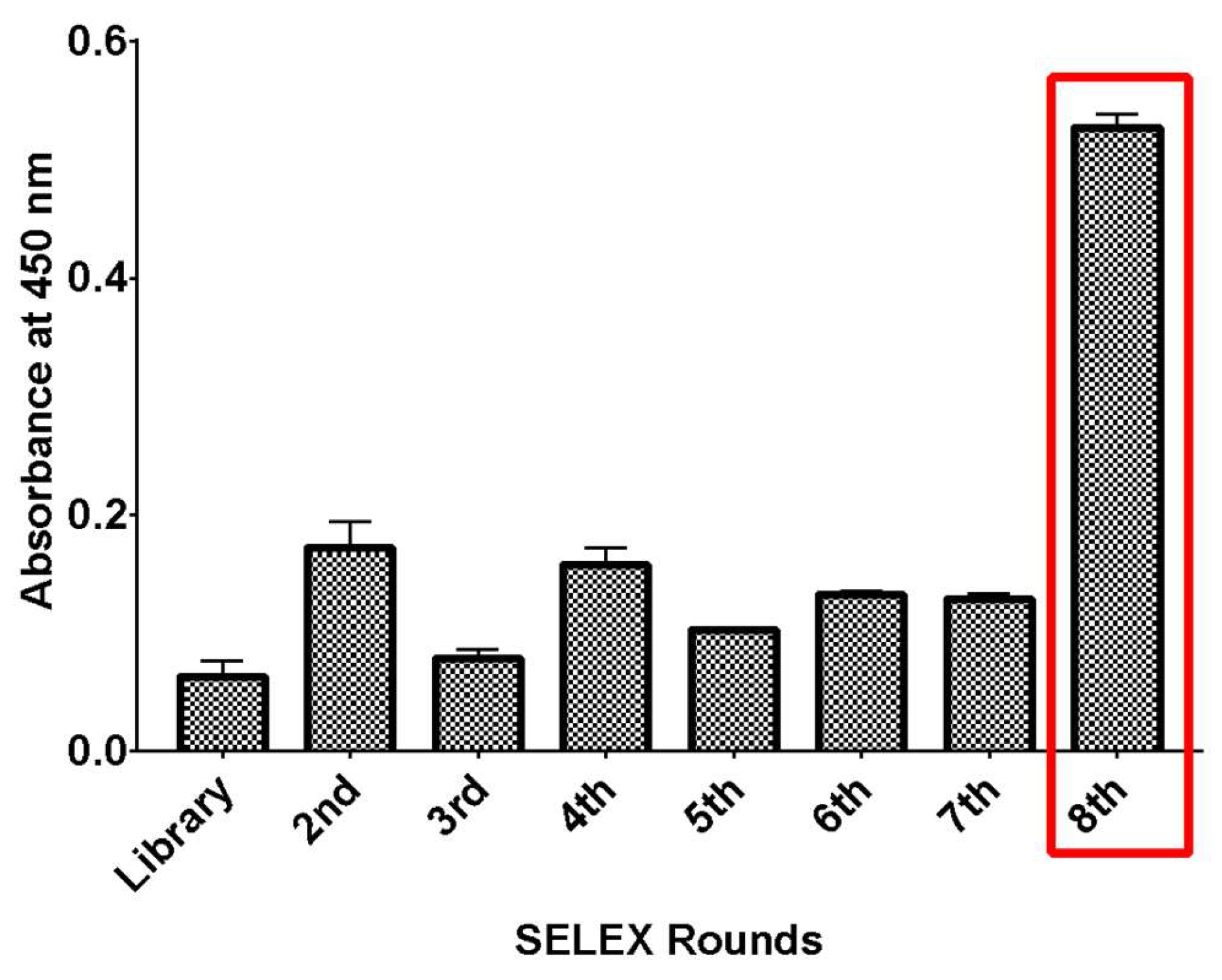

2.2. SELEX Enrichment Analysis

A magnetic bead-based binding assay was utilized to monitor the enrichment of specific single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) that binds to rhICAM-1 during the selection process. The eluted ssDNA from each SELEX round was reamplified using a forward primer modified with a 5'-end biotin tag. For post-SELEX analysis, a fixed amount of ssDNA and selection matrix was used, and the bound ssDNA was detected using HRP-conjugated streptavidin. Aptamer enrichment reached its peak after the eighth selection round, as compared to the initial aptamer library (

Figure 1). Consequently, the products from the final selection round were cloned and sequenced for subsequent sequence analysis.

2.3. Sequence and Structure Analysis of Aptamer

The sequencing analysis of 25 aptamer candidates was clustered into 23 groups based on their sequence similarity (

Table 2, Supplementary Information 3 - 4). The aptamer clusters were also confirmed using the Neighbor-Joining (NJ) tree. Then, the sequences were grouped into three categories, ‘T-rich’, ‘T/G-rich’, and ‘G-rich’ families. The G-quadruplex analysis found seven aptamer candidates that form quadruplex with a varying scoring range from 21 – 61. The sequence with greater guanine tetrads tends to form a more stable quadruplex structure [

14].

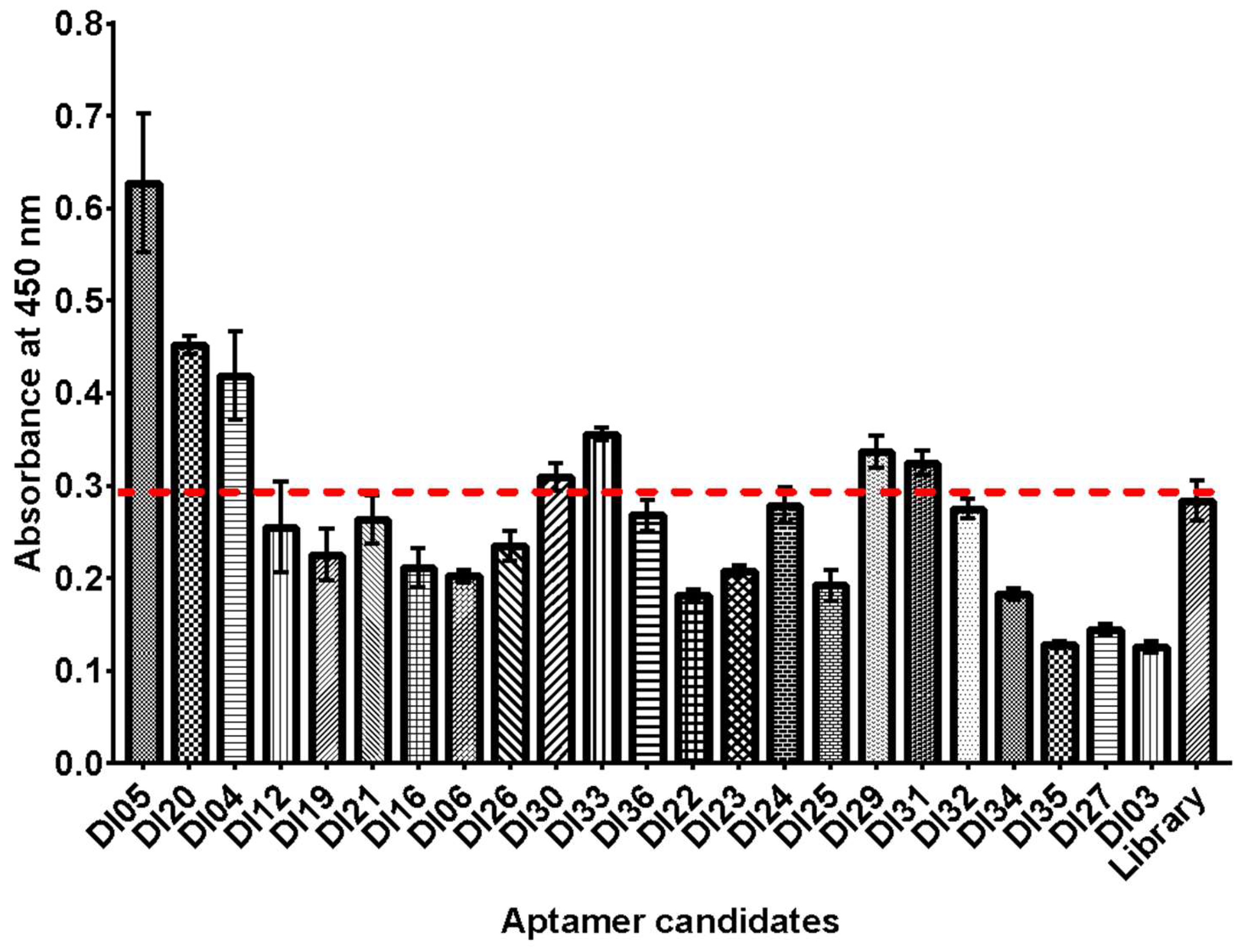

2.4. Binding Analysis of Isolated Aptamer

An ELASA-based binding assay was conducted to evaluate the binding ability of the isolated DNA aptamers to rhICAM-1 protein. The aptamers were labeled using a biotinylated primer for capture or detection. Biotinylated DNA aptamers were immobilized onto microtiter plates pre-coated with avidin. This study identified seven aptamer candidates with significant binding to rhICAM-1 compared to the starting DNA library (

Figure 2). The cut-off absorbance was determined based on the DNA library's value. The high absorbance observed for the DNA library likely resulted from nonspecific binding to rhICAM-1 and anti-human IgG [

15]. Among the candidates, the aptamer DI05, which contains a G/C-rich sequence, demonstrated the highest binding affinity. This was followed by the T-rich family (DI20 and DI33) and the G-rich family (DI31). The balanced composition of T, G, and C bases in the DI05 sequence was previously predicted to enhance its tertiary conformation, contributing to its superior binding ability [

16].

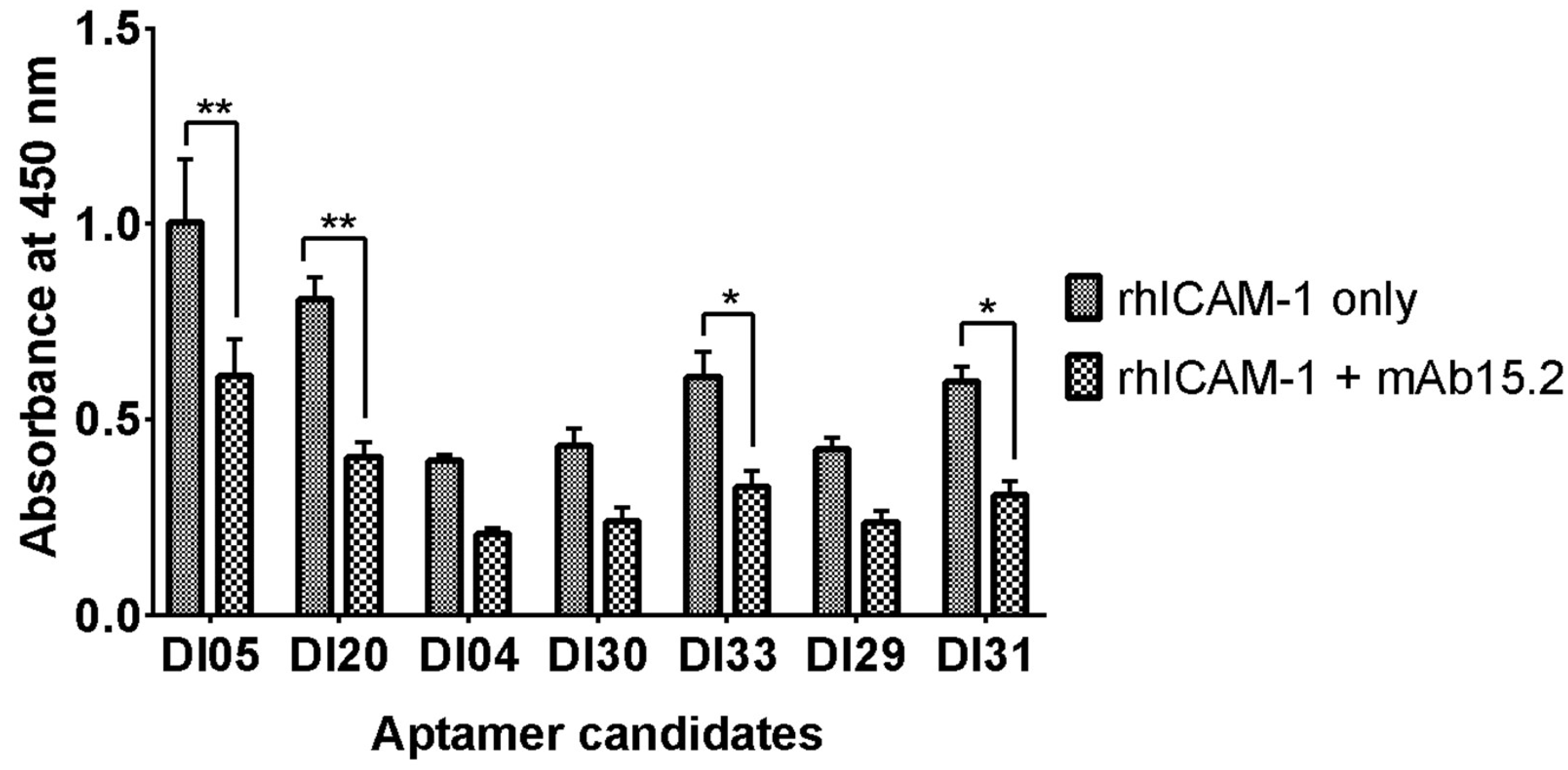

2.5. Binding Orientation of Aptamer to rhICAM-1.

In this assay, a mixture of rhICAM-1 and mAb 15.2 (2 µg/mL) was prepared and introduced to compete with 100 nM of immobilized DNA aptamers. The candidates DI05, DI20, DI31, and DI33 exhibited a significant reduction in absorbance in the presence of mAb 15.2 (

Figure 3). This reduction in absorbance indicates decreased rhICAM-1 binding to immobilized aptamers, likely due to competitive binding between the antibody and aptamer to the same or closely related epitopes on rhICAM-1.

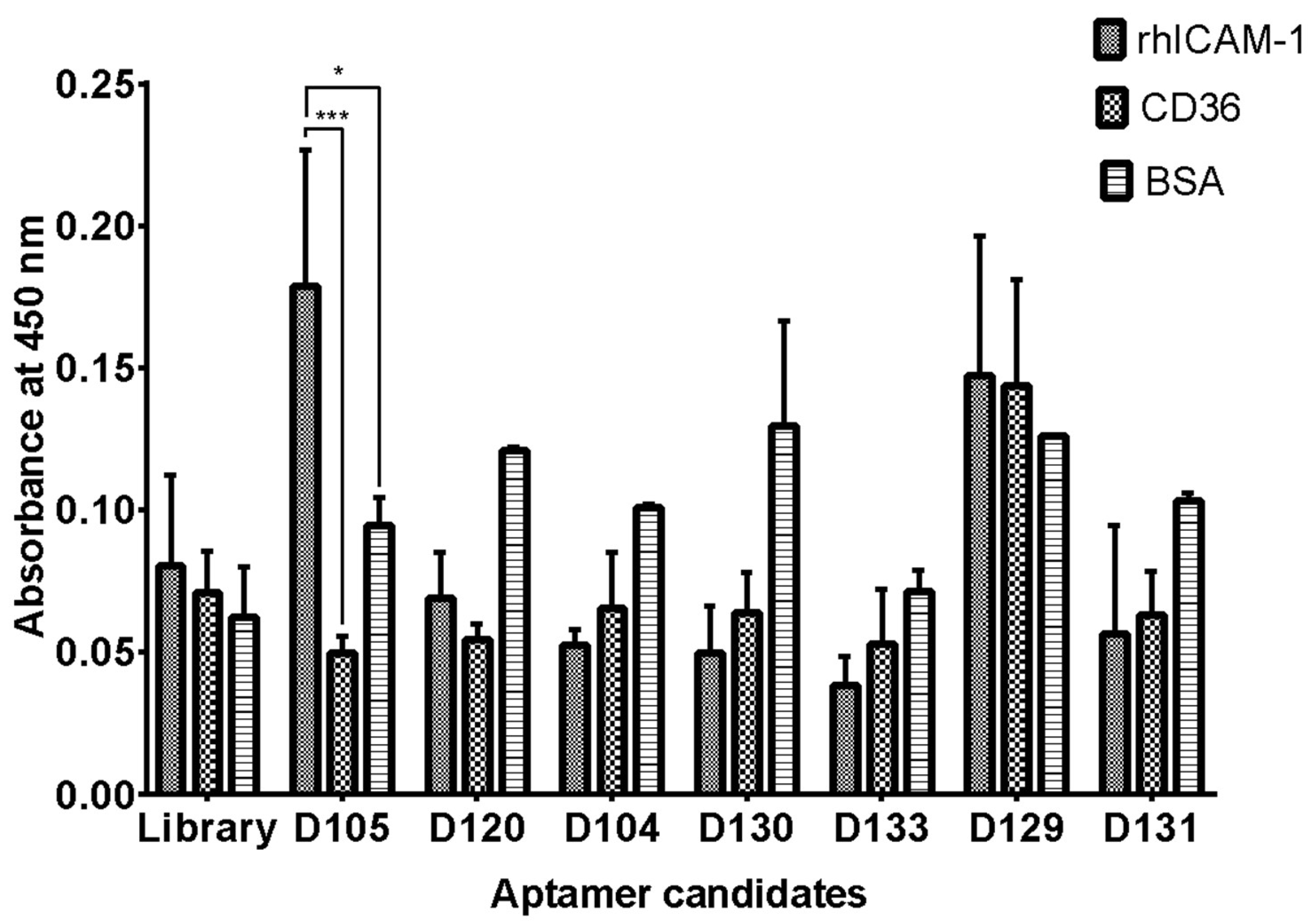

2.6. Specificity of Isolated DNA Aptamer

This study utilized ELASA to rapidly evaluate the relative binding specificity of several isolated DNA aptamers to rhICAM-1, bovine serum albumin (BSA), and recombinant human CD36 (rhCD36). In the assay, proteins were immobilized onto a microplate and incubated with selected aptamers. Results revealed that the DI05 aptamer exhibited low cross-reactivity with both BSA and rhCD36 protein, demonstrating its specificity for rhICAM-1 (

Figure 4).

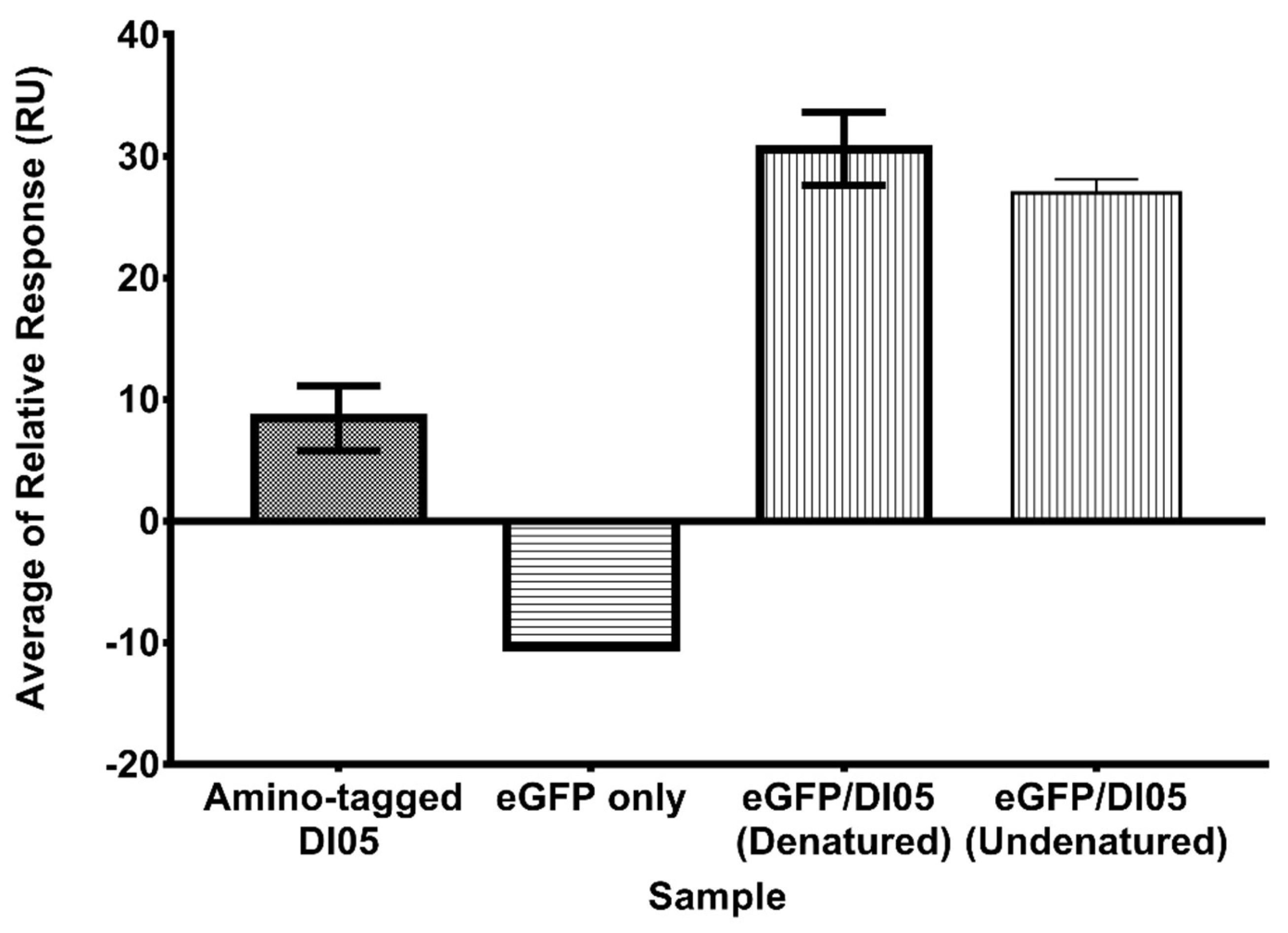

2.7. The eGFP-Conjugated Aptamer Increased the Binding Affinity

This study demonstrated the conjugation of an isolated aptamer to an eGFP protein, which does not interact with rhICAM-1. In this study, the DI05 aptamer was tagged with an amino group, which was later activated during the conjugation reaction. The purified DI05-eGFP conjugate was confirmed through agarose gel electrophoresis and SDS-PAGE, with an estimated molecular weight of 37 kDa (

Supplementary Information 5-6). SPR analysis revealed that eGFP-conjugated DI05 exhibited stronger binding to rhICAM-1 compared to unconjugated DI05 (

Figure 5). Notably, the signal for the denatured conjugated aptamer was higher than that of the undenatured sample. The reduced signal from the undenatured sample may result from misfolding of the aptamer structure, which could hinder its binding to the target protein. This suggests that denaturation prior to binding ensures the aptamer adopts a uniform 3D structure necessary for optimal binding. Additionally, the increased molecular weight of the conjugated aptamer may enhance the sensitivity of SPR analysis, reflected in the higher relative response for aptamer binding.

Furthermore, this binding analysis confirmed that covalent attachment of the aptamer to eGFP did not affect the aptamer's binding function to rhICAM-1. Steady-state analysis showed that the binding affinity of eGFP-conjugated DI05 (108 ± 22.69 nM) was significantly higher than that of unconjugated DI05 (252 ± 46.26 nM) (

Table 3).

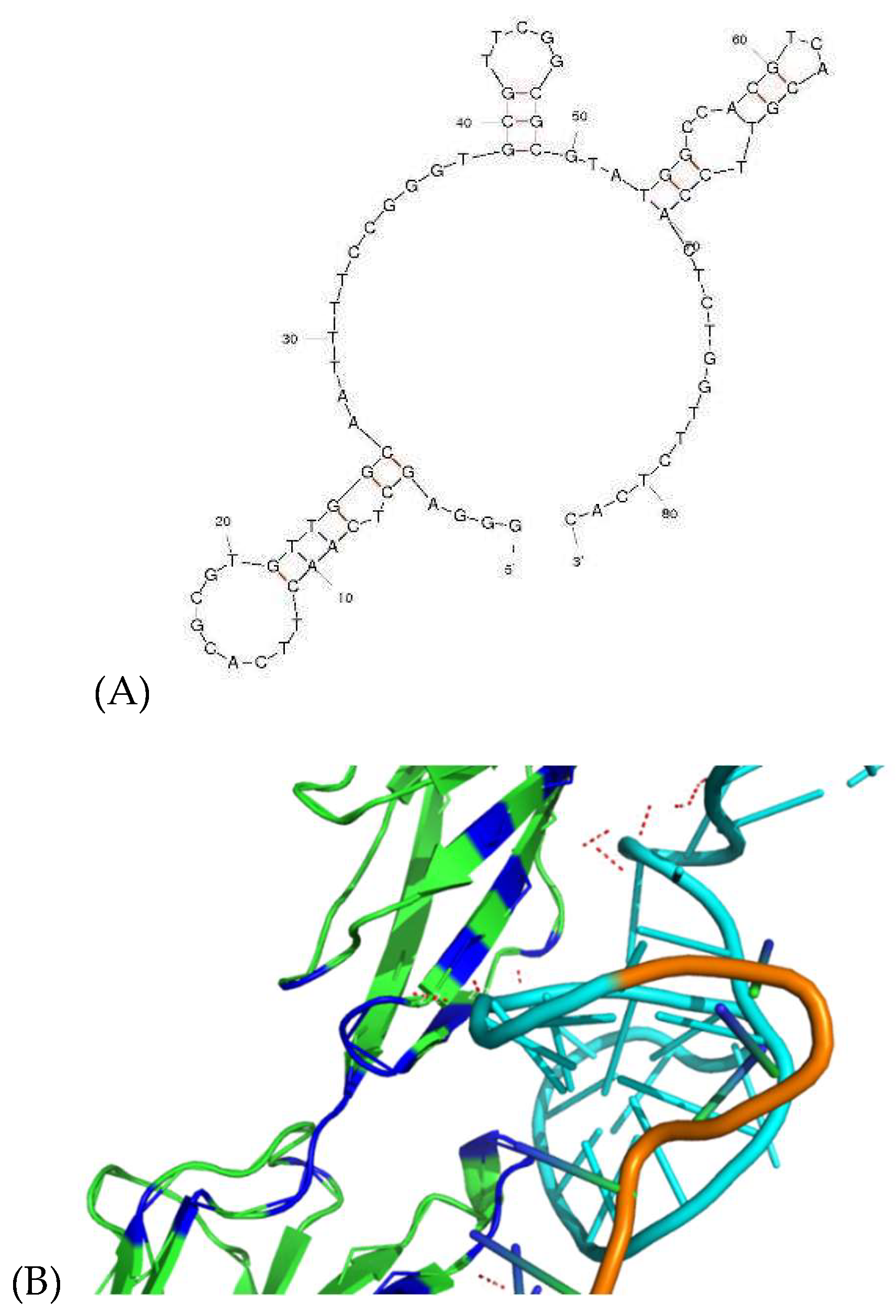

2.8. Molecular Docking of DI05 to ICAM-1 Protein Using HADDOCK

Molecular docking of the aptamer binding to a protein target was performed using HADDOCK software, which facilitates the mapping of potential contact points between the aptamer and protein. Prior to the simulation, the secondary structure of DI05 was predicted, as shown in

Figure 6A. Three hairpin structures were identified, spanning G5-C26, G39-C49, and T52-A69. Typically, the aptamer's contact points are located within the single-stranded regions of the hairpin loop structure, rather than the double-stranded nucleotides. The predicted secondary structure was then used to generate the tertiary structure, followed by molecular docking, as shown in

Figure 6B. The analysis of these binding sites revealed close contact between binding atoms at ≤ 2.8 Å. The details of these close-contact atoms and their corresponding bonding types are summarized in

Table 3.

Table 3.

The binding epitope residue between ICAM-1 protein and DI05 aptamer and their type of interaction. .

Table 3.

The binding epitope residue between ICAM-1 protein and DI05 aptamer and their type of interaction. .

| ICAM-1 residue |

DI05 residue |

Type of interaction |

| Arg49 |

Gua48 (2.0, 2.3, 2.5) Ade52 (2.3) |

Hydrogen |

| Gua50, Cyt49 |

Hydrophobic |

| Thr20 |

Tyh51 (2.7)Ade52 (2.6) |

Hydrogen & Hydrophobic |

| Cyt59 |

Hydrophobic |

| Ser16, Gly14 |

Tyh67 (2.7, 2.2) |

Hydrogen |

| Ser7 |

Thy61 = 1.8 |

| Arg166 |

Thy80 = 2.4 |

Hydrogen & Hydrophobic |

| Pro45 |

Gua41, Gua48 |

Hydrophobic |

| Leu43 |

Cyt47 |

| Leu44 |

Gua48 |

| Arg49 |

Gua49, Gua50 |

| Ser5, Pro6 |

Thy51 |

| Val51 |

Ade52 |

| Leu18 |

Gua52, Ade52 |

| Pro167 |

Cyt59 |

| Gly169 |

Ade58, Cyt59 |

| Glu171 |

Cyt57, Cyt79, Tyh78 |

| Leu11, Val17 |

Thy67 |

| Gly15 |

| Cyt68 |

| Leu170, Ile10 |

Thy66 |

| Leu172 |

Thy78 |

| Cyt79 = 2.8 |

Hydrogen (PyMOL) & Hydrophobic |

3. Discussion

This study demonstrates the successful isolation of a DNA aptamer (DI05) that specifically binds to human ICAM-1, a protein of significant interest in the context of malaria and other diseases involving cell adhesion and immune responses. The use of aptamers as highly specific ligands for target molecules has gained attention due to their ability to bind with high affinity and selectivity, akin to antibodies but with distinct advantages such as lower toxicity, easier synthesis, and greater stability. The G-quadruplex analysis of 25 isolated aptamer found seven aptamer candidates that form quadruplex. The sequence with greater guanine tetrads tends to form a more stable quadruplex structure [

14].

An antibody displacement assay, using the commercial monoclonal antibody 15.2 (mAb 15.2), was performed to evaluate the impact of aptamer binding to rhICAM-1 in the presence of an epitope-specific antibody [

17,

18]. This competitive binding method has been used to confirm epitope-specific aptamers targeting whole-cell surfaces [20,21]. CD36, a multiligand scavenger receptor involved in IEs cytoadherence, contributes to microcirculatory impairment and dysfunction of vital organs like the kidney, lung, and liver in severe malaria patients [

19]. This protein was used in the aptamer binding specificity.

Most studies have employed eGFP-ICAM-1 fusion proteins to study ICAM-1 expression and its interactions with other molecules within cells [

20,

21]. In the present study, eGFP was employed as a model to conjugate with an ICAM-1-specific aptamer. The key finding in this study is that the binding affinity of the DI05 aptamer was significantly enhanced when conjugated to the eGFP. The eGFP-conjugated DI05 aptamer showed increased binding to rhICAM-1 compared to the unconjugated DI05, highlighting the potential of small protein conjugation as a strategy to improve aptamer binding efficiency. Recent research has also investigated DNA aptamers targeting ICAM-1 for cancer treatment and early detection of atherosclerosis [

22,

23]. Our dissociation constant of unconjugated DI05 is consistent with previous studies, which reported values ranging from 151.6 ± 33.9 nM to 214.5 ± 74.2 nM using SPR [

23]. Notably, a study by Kang and Hah (2014) demonstrated that an anti-thrombin aptamer conjugated to a higher-affinity protein (Kd = 567 pM) showed better binding compared to antibody (Kd = 50 nM) or aptamer alone (Kd = 3.5 nM) [

5]. Similarly, combining aptamers with antibodies has shown improved therapeutic efficacy. For example, the combination of anti-VEGF antibody (ranibizumab) and anti-PDGF aptamer (E10010) demonstrated greater therapeutic potency than antibody therapy alone [

24]. As previously reported, the docking simulation focused on selecting active residues on ICAM-1 that are involved in binding with the PfEMP-1 protein [

25]. The results suggest that the conjugation of aptamers with small proteins, such as eGFP, could be a promising method for improving the binding affinity and stability of aptamers. This approach could have broader applications in detection, diagnostics, and therapeutic contexts, where high specificity and affinity are crucial. Furthermore, the study indicates that the DI05-eGFP conjugate does not interfere with the aptamer's binding ability to rhICAM-1, as confirmed by SPR analysis, thus supporting the hypothesis that conjugation with small proteins can enhance, rather than hinder, aptamer function.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Preparation of Selection Matrix

Dynabeads Protein A was coupled with recombinant protein for a positive selection matrix. Briefly, 2.5 mg of Protein A Dynabeads (Invitrogen) were washed three times with 250 µL selection buffer (SB) containing 1X PBS (pH 7.4), 1.5 mM of MgCl2, and 1% BSA. A magnetic bar was used to retain the beads for each washing time, and the pellet was then resuspended in 250 µL of SB. Recombinant human ICAM-1 protein (25 µg/mL) (R&D system, United Kingdom) was added to the bead suspension to be chemically linked to Protein A and formed a positive selection matrix. The mixture was mixed using the MACSmix tube rotator (Miltenyi Biotec, Germany) at 15 rpm at room temperature for one hour. ICAM-1-coupled Dynabeads were purified on the magnet, washed three times with SB, and resuspended in 500 µL of SB. The ICAM-1-coupled Dynabeads were stored at four °C until used. Meanwhile, for the pre-selection matrix, 2.5 mg of Protein A Dynabeads were washed three times with 250 µl of SB using a magnetic bar to retain the beads for each washing time and then resuspended in 500 µL of SB for storage.

4.2. SELEX Experiment

SELEX was carried out by heating 500 pmol of DNA library (5’-GGGAGCTCAACTTCACGCGTG(N40)CACGTTCCACTCTGGTTCTCAC-3’; 4 nmol; HPLC purified) (Integrated DNA Technologies, USA) at 95 °C for 2 minutes and further cool down at room temperature for 10 minutes. Pre-selection matrix (80 µL) (magnetic beads without rhICAM-1) was added, and the volume was brought to 100 µL with the SB. The mixture was then incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes on a tube rotator. The suspension was separated using a magnet, and an unbound aptamer was collected and transferred into 80 µL of positive selection matrix (magnetic beads coupled with rhICAM-1). The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes on a tube rotator. The suspension was separated using a magnet, and the supernatant of the unbound aptamer was discarded. The beads were washed three times with 500 µL of SB. The bound aptamer was eluted using 100 µL of nuclease-free water and heated at 95 °C for 5 minutes. The eluted aptamers were pooled and amplified for the next round of SELEX.

4.3. Amplification of Bound Aptamer

Eluted aptamers were amplified using two steps of PCR (consisting of normal and asymmetric PCR) followed by lambda exonuclease digestion. For normal PCR, 50 µL of the PCR mixture was prepared by mixing 5 µL template (eluted aptamer), 1X Green GoTaq Flexi Buffer, 1.50 mM MgCl2, 0.20 mM dNTPs, 0.25 µM of unmodified forward primer (5’-GGGAGCTCAACTTCACGCGTG-3’), 0.25 µM of phosphorylated reverse primer (5’-/Phos/GTGAGAACCAGAGTGGAACGTG-3’) and 2.5 Units of Taq polymerase. Then, the reaction mixture was amplified using the following condition: pre-denaturation at 94 °C for 5 minutes, five cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 seconds, annealing at 61 °C for 30 seconds, elongation at 72 °C for 30 seconds, and post-elongation at 72 °C for 7 minutes using Veriti® Therma Cycler (Thermo Fisher Scientific, US). The number of PCR cycles for every SELEX cycle was optimized until the correct size band appeared before a large scale of normal PCR was conducted.

The ssDNA production was produced by amplifying the normal PCR product using an unmodified forward primer (5’-GGGAGCTCAACTTCACGCGTG-3’). The 100 µL PCR reaction was prepared to contain 20 µL of the first PCR product (normal PCR), 1X Green GoTaq Flexi Buffer, 1.50 mM of MgCl2, 0.20 mM dNTPs, 0.6 µM of the unmodified forward primer, and 2.5 Units of Taq Polymerase. The reaction was run using an optimized PCR program (94 °C for 5 minutes, ten cycles of 94 °C for 30 seconds, 61 °C for 30 seconds, 72 °C for 1 minute, and a final extension at 72 °C for 7 minutes). The PCR product was digested with lambda exonuclease enzyme by adding 1X reaction buffer and 10 Unit exonuclease (Thermo Scientific). The reaction was incubated at 37 °C for 30 minutes, followed by enzyme inactivation at 85 °C for 10 minutes and ethanol precipitation for highly purified ssDNA.

4.4. Cloning and Sequencing

After eight SELEX rounds, the amplified product was cloned using the TOPO TA Cloning Kit (Invitrogen, USA). Twenty-five (25) colonies were randomly selected from those positive individuals using blue and white screening before extracting the plasmids by DNA-spin Plasmid DNA Extraction Kit (iNtRON Biotechnology, Korea). The plasmid was then sent for sequencing using M13 forward primer (5'-GTAAAACGACGGCCAGT-3’) and M13 reverse primer (5'-CAGGAAACAGCTATGAC-3’) (First BASE Laboratories Sdn Bhd, Malaysia).

4.5. Predicting Secondary Structure

The sequencing results were analyzed and aligned using the ClustaW Multiple Alignment provided by MEGA 6 software (Version 6.06). The DNAs were clustered based on sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis (Neighbour-Joining Tree) provided by MEGA 6 software [

26]. The secondary structure model of the sequences obtained was deduced using mfold software at 25 °C in 0.137 M [Na

+] and 1.5 mM [Mg

2+] folding algorithm. The online QGRS Mapper (

http://bioinformatics.ramapo.edu/QGRS/analyze.php) was used to determine the G-quadruplex sequence of isolated DNA aptamer [

14].

4.6. Enzyme-Linked Apta-Sorbent Assay (ELASA)

The ELASA method was adapted from Mukherjee et al. [

27]. The biotinylated aptamer was produced using PCR by replacing the unmodified primer with a biotin-modified forward primer (5’-/Biosg/GGGAGCTCAACTTCACGCGTG-3’). Briefly, ten µg/mL of avidin was coated on Grenier microtiter plates using 100 mM of Bicarbonate/carbonate coating buffer (pH 9.6) for one hour at 37 °C, followed by a one-hour blocking with 2% (w/v) non-fat milk in PBST (1X PBS, pH 7.4; 0.02% (v/v) Tween-20). The plate was washed three times with PBST using a plate washer. Then, the same concentration of biotinylated ssDNA (100 nM, previously heated at 95 °C for two minutes and cooled down at room temperature for ten minutes) from each of the SELEX cycles in the SB was added into each well of the microtiter plate and incubated for one hour at 37 °C. Subsequently, two µg/mL of rhICAM-1 (diluted in SB) was added to each well and was incubated for one hour at 37 °C. The mixture of two µg/mL of rhICAM-1 protein and two µg/mL of monoclonal antibody 15.2 was added to the plate for the antibody replacement assay. The bound rhICAM-1 was detected using HRP-conjugated anti-human IgG (diluted at 1:20,000 in SB). After washing, the color was developed by adding TMB substrate, and the reaction was stopped after 20 minutes by 2 N HCl. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a Spectramax M5e.

4.7. Specificity of Isolated DNA Aptamers

rhICAM-1, rhCD36, and BSA proteins (two µg/mL) were coated on Grenier microtiter plates using 100 mM of Bicarbonate/carbonate coating buffer, pH 9.6 for one hour at 37 °C, followed by a one-hour blocking with 2% (w/v) non-fat milk in PBST (1X PBS, pH 7.4; 0.02% (v/v) Tween-20). The plate was washed three times with PBST using an ELISA plate washer. Biotinylated ssDNA (500 nM previously heated at 95 °C for two minutes and cooled down at room temperature for ten minutes) was added to each well of the microtiter plate and incubated for one hour at 37 °C. After washing with PBST, the bound aptamer was detected using HRP-conjugated streptavidin (diluted at 1:10,000 in SB). After washing, the color was developed by adding TMB substrate, and the reaction was stopped after 20 min with 2 N HCl. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a Spectramax M5e.

4.8. Generation of Protein-Aptamer Conjugate

Briefly, the selected DI05 DNA aptamer was amplified using two steps of PCR (consisting of normal and asymmetric PCR) followed by lambda exonuclease digestion. For normal PCR, 50 µL of the PCR mixture was prepared to contain 2.50 µL template (unmodified DI05), 1X Green GoTaq Flexi Buffer, 1.50 mM MgCl2, 0.20 mM dNTPs, 0.25 µM of 5’amino-modified forward primer (5’-/AmMC6/GGCGAATTCTGGGGCGATATATCC-3’), 0.25 µM of phosphorylated reverse primer (5’-/Phos/GTGAGAACCAGAGTGGAACGTG-3’) and 2.5 Units of Taq polymerase. Then, the reaction mixture was amplified using the following condition; pre-denaturation at 94 °C for five minutes, 20 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 seconds, annealing at 61 °C for 30 seconds, elongation at 72 °C for 30 seconds, and post-elongation at 72 °C for seven minutes using Veriti® Therma Cycler (Thermo Fisher Scientific, US).

The ssDNA production was produced by reamplifying the normal PCR product using a 5’ end amino-modified forward primer (5’-/AmMC6/GGCGAATTCTGGGGCGATATATCC-3’). The 100 µL PCR reaction was prepared by mixing 20 µL of the first PCR product (normal PCR), 1X Green GoTaq Flexi Buffer, 1.50 mM of MgCl2, 0.20 mM dNTPs, 0.6 µM of the unmodified forward primer, and 2.5 Units of Taq Polymerase. The reaction was run using an optimized PCR program (94 °C for five minutes, ten cycles of 94 °C for 30 seconds, 61 °C for 30 seconds, 72 °C for one minute, and a final extension at 72 °C for seven minutes). The PCR product was digested with lambda exonuclease at 37 °C for 30 minutes, followed by enzyme inactivation at 85 °C for ten minutes. The ethanol-precipitated product was resuspended in 100 µL of nuclease-free water. The amino-tagged aptamer and eGFP protein were activated using Thunder-Link® PLUS Oligo Activation Reagent and Thunder-Link® PLUS Antibody Activation Reagent (Innova Biosciences, United Kingdom), respectively. The reaction was incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes. The excess activation reagent was removed using a separating column previously equilibrated four times with three mL of 1 x Thunder-Link® PLUS Wash Buffer. The activated amino-tagged aptamer and eGFP were eluted with 300 µL of 1 x Thunder-Link® PLUS Wash Buffer. The conjugate reaction was prepared by mixing 300 µL of activated amino-tagged aptamer and 300 µL of activated eGFP, followed by incubation at room temperature on the tube rotator for two hours. The conjugated product was precipitated by adding 600 µL of Thunder-Link® PLUS Conjugate Clean Up Reagent and incubated on ice for 30 minutes. After centrifuging at 15,000 x g for ten minutes, the supernatant was discarded. The pellet was resuspended with 50 µL of Thunder-Link® PLUS Antibody Suspension Buffer. The concentration of conjugated products was measured using NanoDrop1000 at wavelengths 260 nm (nucleic acid module) and 280 nm (protein A280 module). The conjugated product was confirmed using 2% (w/v) agarose gel in 1X TAE buffer, stained with Diamond™ Nucleic Acid Dye (Promega, USA), and then visualized using a UV transilluminator. Meanwhile, the conjugated products run on 12% (v/v) SDS-PAGE under reduced (heat) and non-reduced (without heat). Then, the gel was stained with Coomassie Blue Stain and visualized with white light.

4.9. Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)

The aptamer binding analysis and dissociation constant (Kd) were evaluated using Biacore X100 (GE Healthcare). The CM5 chip was used to immobilize recombinant human ICAM-1 (rhICAM-1) using an amine coupling kit on flow-cell 2, while flow-cell one was left blank (reference cell). All the experiments were conducted at 25 °C. Before coupling, the dextran surface of the CM5 chip was activated using NHS/EDC mixture. After that, 25 µg/mL of rhICAM-1 diluted in sodium acetate (pH 5.0) was injected at a flow rate of 10 µL/min until it reached an immobilization level of 2000 RU, and the remaining active esters were deactivated using ethanolamine. Before experimenting, the flow cell of the Biacore system containing the maintenance chip was desorbed using BIAdesorb solution 1 (0.5% (w/v) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)) and BIAdesorb solution 2 (50 mM glycine-NaOH pH 9.5). The system was then primed with deionized water once. The ICAM-1-immobilized CM5 chip was docked and primed with a running buffer (1X PBS, pH 7.4; 1.5 mM MgCl2; 0.005% (v/v) Tween20; 0.1% BSA (v/v)) for three times. Before eGFP-conjugated aptamer injection, the sample was pre-denatured at 95°C and cooled down at RT for ten minutes. The aptamer was injected at 30 µL/min for 180 seconds and dissociated for 600 seconds, followed by a regeneration step using ten mM glycine-HCl (pH 2.5) for 30 seconds. An undenatured sample was injected directly into the immobilized chip as a control. For Kd value determination, the aptamer was diluted two-fold range from 31.25, 62.5, 125, 250, and 500 nM in SB. Data were processed using the BIAevaluation software (GE Healthcare Europe GmbH, Germany) to plot the steady-state binding from the end of the association phase against analyte concentration.

4.10. Molecular Docking

The 3D structure of ICAM-1 (PDB code: 5MZA, resolution 2.78 Å) was taken from Protein Data Bank. The docking was performed using the online server HADDOCK 2.2 on an easy interface [

28]. To ensure the highest number of correct decoys was generated, the HADDOCK server used ambiguous interaction restraints to run the docking process repetitively. Further, any decoys driven by wrong restraints were discriminated against based on their lower scores than the correct decoys. Output decoys are provided as a water-refined structure sorted by its HADDOCK score. Before the docking was conducted, the previously predicted secondary structure of DNA (DI05) was manually converted to RNA by substituting T with U nucleotide on the Vienna file format. The tertiary structure of DI05 was predicted using online RNAComposer version 1.0 (

http://rnacomposer.cs.put.poznan.pl/). The tertiary structure of RNA was converted back to DNA using PyMOL software version 2.3.0 by substituting the hydroxyl group (OH) to the hydrogen (H) group at carbon two atoms of the sugar group [

29,

30]. Both protein and nucleic acid files were saved as a PDB file and uploaded to the HADDOCK server. The docking of DI05 was conducted based on the identified contact point of two domains structure of ICAM-1 and PfEMP1 protein (Glu111, Leu42, Glu87, Glu53, Gly14, Gln58, Thr85, Trp84, Leu44, Arg13, Gly15, Val51, Pro6, Leu18, Pro12, Arg49, Ser16, Ile10, Tyr83, Phe173, Leu170, Pro45, Leu43, Gly169, Glu171, Val117). The obtained structure was analyzed using PyMOL, and the contact point of aptamer and protein interaction was identified using LigPlus+ software version 2.1.

4.11. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was done using Two-way ANOVA and unpaired t-test using GraphPad Prism (Version 7.0). The error bar indicates the standard error means (±SEM) of the triplicate experiments, and P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

5. Conclusions

This study successfully isolated a DNA aptamer (DI05) that specifically binds to rhICAM-1, and demonstrated that conjugation to eGFP enhanced binding affinity. This suggests that aptamer-protein conjugates could improve aptamer-target interactions, with potential applications in diagnostics and therapeutics. However, the study has some limitations. It focused on a single conjugate (eGFP) without comparing different conjugation strategies, and lacked in vivo validation. There was also no exploration of aptamer truncation or structural analysis, and functional outcomes of the enhanced binding were not tested. Additionally, the study did not compare eGFP conjugation to other aptamer-protein or antibody conjugates. Future research should broaden the scope of conjugation partners, include in vivo validation, and explore functional outcomes. Structural optimization and comparisons to other conjugates will be crucial to enhance aptamer design for practical applications in disease treatment and detection. In conclusion, while this study provides a proof-of-concept, further exploration is needed to optimize and apply protein-conjugated aptamers in real-world biological systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Nik Abdul Aziz Nik Kamarudin, Nurfadhlina Musa and Khairul Mohd Fadzli Mustaffa; Formal analysis, Nik Abdul Aziz Nik Kamarudin; Funding acquisition, Khairul Mohd Fadzli Mustaffa; Investigation, Nik Abdul Aziz Nik Kamarudin, Nurfadhlina Musa, Nur Fatihah Mohd Zaidi and Basyirah Ghazali; Methodology, Nik Abdul Aziz Nik Kamarudin, Nurfadhlina Musa, Nur Fatihah Mohd Zaidi and Basyirah Ghazali; Project administration, Khairul Mohd Fadzli Mustaffa; Supervision, Khairul Mohd Fadzli Mustaffa; Visualization, Nik Abdul Aziz Nik Kamarudin; Writing – original draft, Nik Abdul Aziz Nik Kamarudin; Writing – review & editing, Nik Abdul Aziz Nik Kamarudin, Nurfadhlina Musa, Mariana Ahamad, Satvinder S Dhaliwal and Khairul Mohd Fadzli Mustaffa.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Education Malaysia (Kementerian Pendidikan Malaysia) under the HICoE Grant (311/CIPPM/4401005).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Director General of Health Malaysia for his permission to publish this article. This research was funded by the Ministry of Education Malaysia (Kementerian Pendidikan Malaysia) under the HICoE Grant (311/CIPPM/4401005).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhou J, Rossi J: Aptamers as targeted therapeutics: current potential and challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2017, 16, 181–202. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu Z, Xiang J: Aptamers, the Nucleic Acid Antibodies, in Cancer Therapy. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21.

- Heo K, Min S-W, Sung HJ, Kim HG, Kim HJ, Kim YH, Choi BK, Han S, Chung S, Lee ES et al: An aptamer-antibody complex (oligobody) as a novel delivery platform for targeted cancer therapies. Journal of Controlled Release 2016, 229, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Ni S, Zhuo Z, Pan Y, Yu Y, Li F, Liu J, Wang L, Wu X, Li D, Wan Y et al: Recent Progress in Aptamer Discoveries and Modifications for Therapeutic Applications. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2021, 13, 9500–9519.

- Kang S, Hah SS: Improved ligand binding by antibody-aptamer pincers. Bioconjug Chem 2014, 25, 1421–1427. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skovsgaard MB, Mortensen MR, Palmfeldt J, Gothelf KV: Aptamer-Directed Conjugation of DNA to Therapeutic Antibodies. Bioconjug Chem 2019, 30, 2127–2135. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeo JE, Wickramaratne S, Khatwani S, Wang Y-C, Vervacke J, Distefano MD, Tretyakova NY: Synthesis of site-specific DNA-protein conjugates and their effects on DNA replication. ACS Chem Biol 2014, 9, 1860–1868. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giepmans BNG, Adams SR, Ellisman MH, Tsien RY: The Fluorescent Toolbox for Assessing Protein Location and Function. 2006, 312, 217–224. Science, 2006; 312, 217–224.

- Silamut K, Phu NH, Whitty C, Turner GD, Louwrier K, Mai NT, Simpson JA, Hien TT, White NJ: A quantitative analysis of the microvascular sequestration of malaria parasites in the human brain. Am J Pathol 1999, 155, 395–410. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willimann K, Matile H, Weiss NA, Imhof BA: In vivo sequestration of Plasmodium falciparum-infected human erythrocytes: a severe combined immunodeficiency mouse model for cerebral malaria. J Exp Med 1995, 182, 643–653. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustaffa KMF, Storm J, Whittaker M, Szestak T, Craig AG: In vitro inhibition and reversal of Plasmodium falciparum cytoadherence to endothelium by monoclonal antibodies to ICAM-1 and CD36. Malar J 2017, 16, 279. [CrossRef]

- Chames P, Van Regenmortel M, Weiss E, Baty D: Therapeutic antibodies: successes, limitations and hopes for the future. Br J Pharmacol 2009, 157, 220–233. [CrossRef]

- Arruebo M, Valladares M, González-Fernández Á: Antibody-Conjugated Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications. Journal of Nanomaterials 2009, 2009, 439389. [CrossRef]

- Kikin O, D'Antonio L, Bagga PS: QGRS Mapper: a web-based server for predicting G-quadruplexes in nucleotide sequences. Nucleic Acids Research 2006, 34 (Suppl. 2), W676–W682. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu J, You M, Pu Y, Liu H, Ye M, Tan W: Recent developments in protein and cell-targeted aptamer selection and applications. Curr Med Chem 2011, 18, 4117–4125. [CrossRef]

- Conference Proceedings – 4th International Conference on Molecular Diagnostics and Biomarker Discovery: Antibody Technology. BMC Proceedings 2019, 13, 10. [CrossRef]

- Zumrut HE, Ara MN, Maio GE, Van NA, Batool S, Mallikaratchy PR: Ligand-guided selection of aptamers against T-cell Receptor-cluster of differentiation 3 (TCR-CD3) expressed on Jurkat. E6 cells. Anal Biochem 2016, 512, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilner SE, Wengerter B, Maier K, de Lourdes Borba Magalhães M, Del Amo DS, Pai S, Opazo F, Rizzoli SO, Yan A, Levy M: An RNA alternative to human transferrin: a new tool for targeting human cells. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2012, 1, e21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gowda DC, Wu X: Parasite Recognition and Signaling Mechanisms in Innate Immune Responses to Malaria. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 3006. [CrossRef]

- van Buul JD, van Rijssel J, van Alphen FPJ, Hoogenboezem M, Tol S, Hoeben KA, van Marle J, Mul EPJ, Hordijk PL: Inside-out regulation of ICAM-1 dynamics in TNF-alpha-activated endothelium. PLoS One 2010, 5, e11336. [CrossRef]

- Volanti C, Gloire G, Vanderplasschen A, Jacobs N, Habraken Y, Piette J: Downregulation of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression in endothelial cells treated by photodynamic therapy. Oncogene 2004, 23, 8649–8658. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şener BB, Yiğit D, Bayraç AT, Bayraç C: Inhibition of cell migration and invasion by ICAM-1 binding DNA aptamers. Anal Biochem 2021, 628, 114262. [CrossRef]

- Dursun AD, Dogan S, Kavruk M, Busra Tasbasi B, Sudagidan M, Deniz Yilmaz M, Yilmaz B, Ozalp VC, Tuna BG: Surface plasmon resonance aptasensor for soluble ICAM-1 protein in blood samples. Analyst 2022, 147, 1663–1668. [CrossRef]

- Jo N, Mailhos C, Ju M, Cheung E, Bradley J, Nishijima K, Robinson GS, Adamis AP, Shima DT: Inhibition of platelet-derived growth factor B signaling enhances the efficacy of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy in multiple models of ocular neovascularization. Am J Pathol 2006, 168, 2036–2053. [CrossRef]

- Lennartz F, Adams Y, Bengtsson A, Olsen RW, Turner L, Ndam NT, Ecklu-Mensah G, Moussiliou A, Ofori MF, Gamain B et al: Structure-Guided Identification of a Family of Dual Receptor-Binding PfEMP1 that Is Associated with Cerebral Malaria. Cell Host & Microbe 2017, 21, 403–414.

- Nik Abdul Aziz Nik Kamarudin, Judy Nur Aisha Sat, Nur Fatihah Mohd Zaidi, Mustaffa KMF: Evolution of specific RNA aptamers via SELEX targeted recombinant human CD36 protein: A candidate therapeutic target in severe malaria Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine 2019.

- Mukherjee M, Manonmani HK, Bhatt P: Aptamer as capture agent in enzyme-linked apta-sorbent assay (ELASA) for ultrasensitive detection of Aflatoxin B1. Toxicon 2018, 156, 28–33. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Zundert GCP, Rodrigues JPGLM, Trellet M, Schmitz C, Kastritis PL, Karaca E, Melquiond ASJ, van Dijk M, de Vries SJ, Bonvin AMJJ: The HADDOCK2. 2 Web Server: User-Friendly Integrative Modeling of Biomolecular Complexes. Journal of Molecular Biology 2016, 428, 720–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabri MZ, Abdul Hamid AA, Sayed Hitam SM, Abdul Rahim MZ: In Silico Screening of Aptamers Configuration against Hepatitis B Surface Antigen. Adv Bioinformatics 2019, 2019, 6912914. [CrossRef]

- Jeddi I, Saiz L: Three-dimensional modeling of single stranded DNA hairpins for aptamer-based biosensors. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 1178. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).