1. Summary

Freshwater ecosystems are among the most threatened systems globally [

1], needing effective management and restoration. Understanding the intricate relationship between landscapes and rivers, as well as the impact of human activities, land use, and land cover on watercourses, is essential [

2]. Thus, riverscape approaches [

3] across large spatial scales can aid in identifying priority areas for conservation and restoration. Strategies towards management and conservation focused on freshwater environments must account for the river network’s structure and characteristics to be successful [

4]. Various key characteristics like directionality, hierarchy, dendriticity, nestedness, and connectedness influence river dynamics, morphology, ecological integrity [

5] and biodiversity [

6].

Composed of a river network and its drainage area, sea outlet basins are the crucial spatial unit for freshwater conservation and management due to their insular nature. Their functioning is naturally independent of neighbouring basins, and thus, essential towards managing and understanding freshwater-related biodiversity patterns and ecosystem processes [

7]. However, understanding spatial patterns at multiple scales and across multiple basins is decisive for monitoring, conservation and restoration implementation plans [

8] and investigating ecological processes [

3]. River networks can be separated into discrete nested sub-networks made from their elementary components, i.e., river segments and their drainage areas [

9]. Thus, it is possible to break sea outlet basins into meaningful smaller spatial units.

Acknowledging and adopting a riverscape approach is decisive for research projects targeting freshwater environments. The MERLIN project (H2020-LC-GD-2020) focuses on freshwater-related ecosystems and one of the main goals is to upscale and mainstream ecosystem restoration at the landscape scale. Specifically, the project aims to “identify landscapes with high potential and priority for transformative restoration, particularly focusing on essential ecosystem services, biodiversity targets, and climate change mitigation and adaptation” (

https://project-merlin.eu/). To achieve this, a European-wide analysis was conducted using multiple information sources such as environmental-related EU Directives (e.g., Habitats Directive, Water Framework Directive), freshwater ecosystem typologies, hydrological alterations (e.g., river barriers), climate projections and ecosystem services. Considering this, defining spatial units within each sea outlet basin was necessary to enable a comprehensive analysis incorporating multiple data inputs toward the project’s objectives. A spatial aggregation that facilitates river network connectivity at large spatial extents while allowing for multi-resolution analyses was also necessary under the Dammed Fish project (Impact of structural and functional river network connectivity losses on fish biodiversity – Optimising management solutions). Dammed Fish aims to evaluate and propose solutions and tools to inform river network connectivity management, improve fish biodiversity and enhance the biotic quality of European rivers. Hence, we created the River Restoration Units (R2U) along with respective characterizing attributes.

R2U were created in each sea outlet basin occurring in past and present European Union Member states. Taking advantage of the nested nature of river networks, the methodological procedure derived homogeneous units concerning drainage and river length while maintaining abidance by the hierarchical, dendritic and directional nature of river networks. As such, R2U facilitate relating freshwater ecosystems with multiple data sources, at distinct resolutions and for large spatial extents. This dataset became the backbone for European-wide analyses targeted by the MERLIN project (H2020-LC-GD-2020), while also used for some analysis in their case studies. Beyond the MERLIN project [

10], this dataset has already been used to discuss the challenges of restoration targeting free-flowing rivers under the Nature Restoration Law [

11]. We believe this database can be useful for other studies focusing on freshwater-related environments, particularly when requiring inner-basin sub-divisions where the maintenance of the network properties of rivers is paramount, e.g. river connectivity assessments, such as the ones carried out by the Dammed Fish project.

2. Data Description

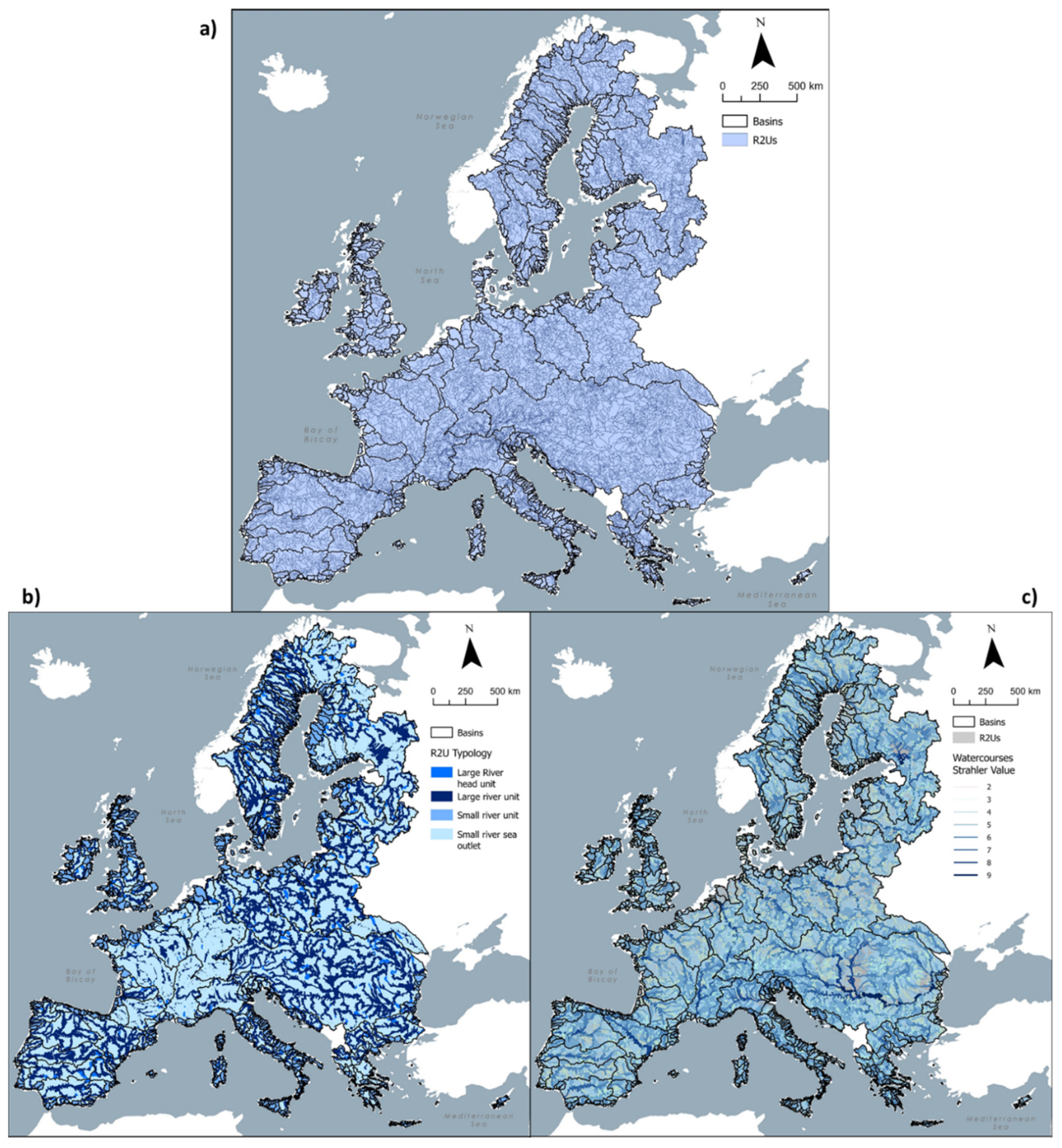

The dataset encompasses all river basins containing at least a river segment of Strahler stream order 3 within the Member States of the European Union (EU MS) and the former Member State United Kingdom (

Figure 1). The spatial layers of the Catchment Characterisation and Modelling – River and Catchment Database v2.1 (CCM2) [

12] served as input data for the European river networks.

The dataset was streamlined into a PostgreSQL database to facilitate usage and dissemination. The database entity-relation diagram (

Figure 2) portrays 3 tables related to spatial layers: 1) Basins_EU, 2) R2U_ID_drainage_areas, 3) R2U_Watercourses. The first layer was taken from the CCM2 database and represents the polygons of the sea outlet basins in the study area. The second and third layers represent, respectively, the polygons and lines of the drainage areas and watercourses for each R2U created. The database includes four other exclusively tabular elements: one table containing the attributes of the R2U and three other supporting tables that codify attributes created to achieve data normalization.

Table 1 describes all attributes included in the elements of the database, including the units when adequate, enabling a correct interpretation and articulation of the dataset.

The dataset includes 11 557 R2U (

Figure 3a), 7.7% Large River Units (LRU) (889) and 92.3% Small River Units (SRU) (10 668), an SRU per LRU ratio of 12.0. Of the SRU category, 15.7% are sea outlet SRU (1 674) and 4.9% are large river head unit SRU (524). On average R2U have between 65 to 66 segments, 153.0 km of river length and 432.7 km2 of drainage area.

Figure 3b portrays the different typologies of R2U, including the SRU sub-groups, in the study area. LRU emphasize the main stem watercourses of each river basin.

Figure 3c depicts the watercourses associated per R2U per maximum Strahler stream order, exposing an attribute from the database that can illustrate the hierarchy of each basin.

3. Methods

3.1. Methodological Procedure

To create the R2U dataset, we aggregated the segments and respective direct drainage areas provided in the CCM2 database [

12], as these are the fundamental building blocks of river networks [

9]. CCM2 is a homogeneous and integrated hierarchical representation of rivers and their drainage catchments across Europe that includes layers of sea outlet basins (drainage area of a river network flowing into the sea), river segments (river stretches between confluences), and corresponding drainage catchments (area draining directly to a river segment) [

14]. A new function, named “River Restoration Units”, was implemented in the River Network software (RivTool) [

15] to enable the computation of R2U tabular data, subsequently spatially implemented using ArcGIS® tools. This aggregation complies with the nested nature of rivers systematized by ’Hack’s Stream order’ [

16] and uses thresholds based on the Strahler stream order (Strahler, 1957), upstream drainage area (UDA), and upstream river length (URL) defined as follows:

Strahler value = 3 – this establishes a level of network complexity. Strahler values express branching, hierarchy, and morphology [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21] and values around 3 have been identified as thresholds of difference in terms of freshwater species richness and diversity;

UDA = 1 000 km2 – defined conservatively to maintain area-wise homogeneous units. This is relevant due to the species-area relationship [

22] and its explanatory power for biodiversity at large scales [

23,

24]. Also, the Water Framework Directive defines large rivers as those with UDAs above 10 000 km2 [

25] and, riverscape units with areas between 1 000 km2 and 10 000 km2 have been linked to regional biodiversity [

26];

URL = 1 000 km – defined to maintain lengthwise homogeneous units and to control exceptions where river length is not correlated with the drainage area. A watercourse with a length above 1 000 km has been termed a large river [

27] or even a very long river in connectivity impairment studies [

28].

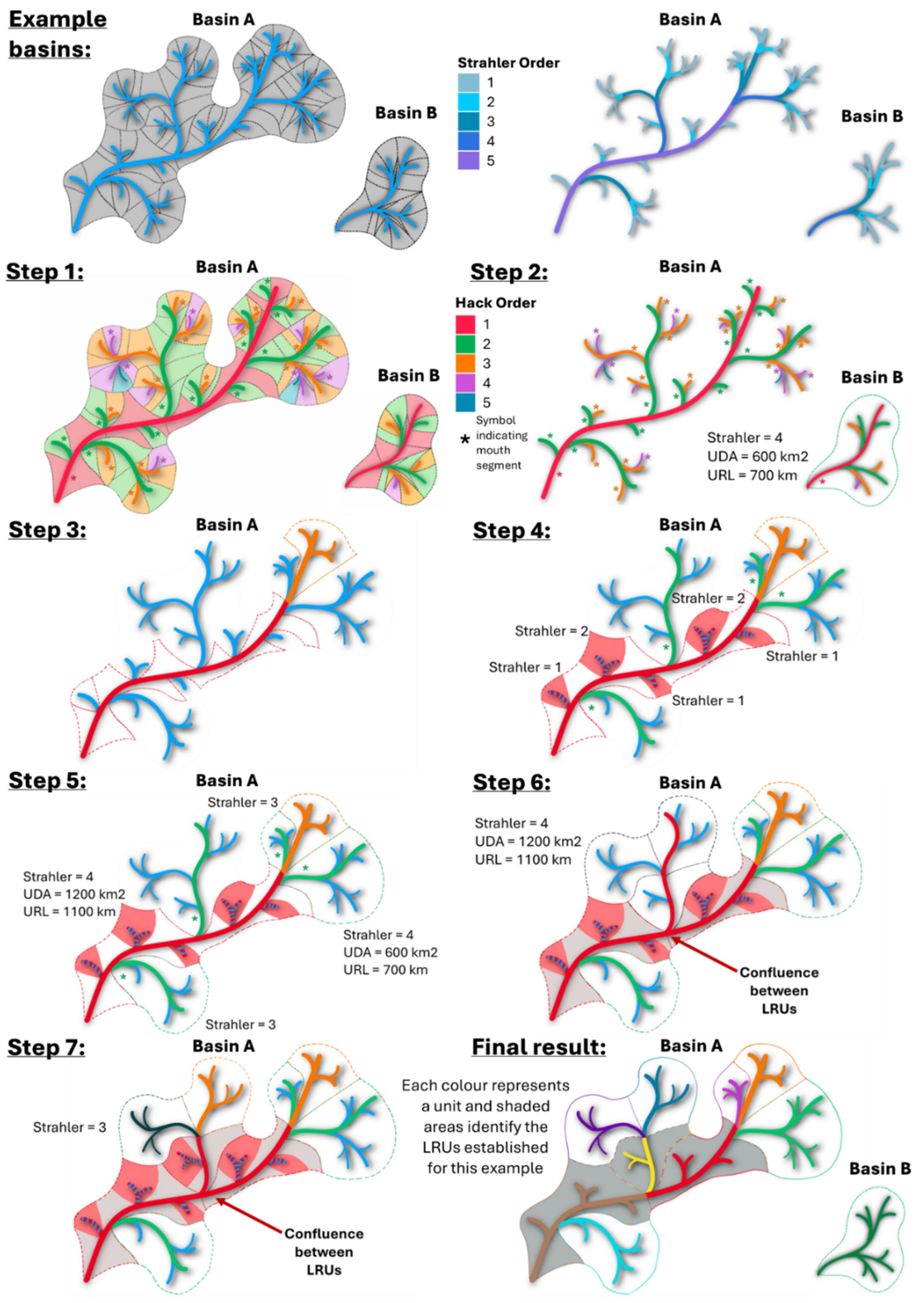

The procedure to establish the R2U is fully described in the following procedure steps and depicted in

Figure 4.

Identify the source segment of the main stem watercourse of the basin and afterwards all the Hack pathways and respective mouth segments for the sea outlet basin. Exclude basin with overall maximum Strahler values below 3 (

Figure 4 – Step 1).

For the mouth segments of Hack n (where n is a discrete number starting at 1 and incremental for every procedure iteration) not abiding by all thresholds, their full upstream drainage area (UDA) and upstream river length (URL) are considered part of one single SRU. If this is the first iteration, where Hack = 1, then all segments in the basin are now identified with one SRU, an R2U comprising the entire basin, and the entire procedure ends (Basin B in

Figure 4 – Step 2). If this step does not apply head to step 3 (

Figure 4 – Step 2).

For those abiding by the thresholds, an LRU will be established from the mouth segment until the most upstream Hack n segment where Strahler order is 4 inclusively (Basin A in

Figure 4 – Step 3). Upstream of this segment, the segments of hack n and respective UDA and URL will become part of an SRU (orange segments in Step 3).

Identify the Hack n + 1 mouth segments having a Strahler order lower than 3. These, along with respective UDA and URL will be included in the large river unit established for the previous hack n segments (red segments and respective UDAs in

Figure 4 – Step 4).

Identify the Hack n + 1 mouth segments having Strahler order ≥ 3 but not abiding by the other thresholds. Each one with its respective upstream segments, UDA and URL will constitute an individual SRU (green segments in

Figure 4 – Step 5).

Identify the Hack n + 1 mouth segments abiding by all the thresholds established for LRU, these will be part of a new large river unit to be established in the river basin. Establishing a new LRU starting in a Hack n + 1 mouth segment leads to a confluence between LRU. To maintain the dendritic, and hierarchical nature of the network the previously established LRU in the Hack n segments will be split at this confluence (red segments in

Figure 4 – Step 6).

The procedure to define the extent of the hack n + 1 LRU and to continue the process can be now taken back from step 2 onwards (since a new iteration will start, n will also increase accordingly) (dark blue and orange segments in

Figure 4 – Step 7).

The application of the R2U methodological procedure creates two types of R2U, small river units (SRU) and large river units (LRU), for each sea outlet river basin. LRU are units associated with the main stem pathways of river basins that serve as connectors between SRU, which are on average units of smaller size and complexity. The procedure to establish an LRU is preceded by adhering to all the thresholds: Strahler values above 3, UDA above 1 000 km2, and URL above 1 000 km. Considering these thresholds, some SRU may fall within two categories: 1) small river sea outlet (SRSO), an SRU that matches the full sea outlet basin; and 2) large river head unit (LRHU), an SRU that contains the source segment of a contiguous LRU.

Figure 4.

Application of the methodological procedure to establish the river restoration units (R2U). On top, example basins are depicted using segments and their direct drainage areas (right) and Strahler classification of the network segments (left). Step 1: Identify the source segment of the main stem watercourse of the basin and afterwards all the Hack pathways and respective mouth segments for the sea outlet basin. Exclude basin with overall maximum Strahler values below 3. Step 2: For the mouth segments of Hack n (where n is a discrete number starting at 1 and incremental for every procedure iteration) not abiding by all thresholds, their full upstream drainage area (UDA) and upstream river length (URL) are considered part of one single Small River Unit (SRU). If this is the first iteration, where Hack = 1, then all segments in the basin are now identified with one SRU, an R2U comprising the entire basin, and the entire procedure ends (Basin B). If this step does not apply (Basin A) head to step 3. Step 3: For those abiding by the thresholds, a Large River Unit (LRU) will be established from the mouth segment until the most upstream Hack n segment where the Strahler value is 4 inclusively. Upstream of this segment, the segments of hack n and respective UDA and URL will become part of an SRU (orange segments). Step 4: Identify the Hack n + 1 mouth segments having a Strahler value lower than 3. These, along with respective UDA and URL will be included in the LRU established for the previous hack n segments (red segments and respective UDA). Step 5: Identify the Hack n + 1 mouth segments having Strahler value ≥ 3 but not abiding by the other thresholds. Each one with its respective upstream segments, UDA and URL will constitute an individual SRU (green segments). Step 6: Identify the Hack n + 1 mouth segments abiding by all the thresholds established for LRU, these will be part of a new LRU to be established in the river basin. Establishing a new LRU starting in a Hack n + 1 mouth segment leads to a confluence between LRU. To maintain the dendritic and hierarchical nature of the network the previously established LRU in the Hack n segments will be split at this confluence (red segments). Step 7: The procedure to define the extent of the hack n + 1 LRU and to continue the process can now be taken back from step 2 onwards (since a new iteration will start, n will also increase accordingly). The procedure ends when all river segments of a given basin are included in one R2U (dark blue and orange segments).

Figure 4.

Application of the methodological procedure to establish the river restoration units (R2U). On top, example basins are depicted using segments and their direct drainage areas (right) and Strahler classification of the network segments (left). Step 1: Identify the source segment of the main stem watercourse of the basin and afterwards all the Hack pathways and respective mouth segments for the sea outlet basin. Exclude basin with overall maximum Strahler values below 3. Step 2: For the mouth segments of Hack n (where n is a discrete number starting at 1 and incremental for every procedure iteration) not abiding by all thresholds, their full upstream drainage area (UDA) and upstream river length (URL) are considered part of one single Small River Unit (SRU). If this is the first iteration, where Hack = 1, then all segments in the basin are now identified with one SRU, an R2U comprising the entire basin, and the entire procedure ends (Basin B). If this step does not apply (Basin A) head to step 3. Step 3: For those abiding by the thresholds, a Large River Unit (LRU) will be established from the mouth segment until the most upstream Hack n segment where the Strahler value is 4 inclusively. Upstream of this segment, the segments of hack n and respective UDA and URL will become part of an SRU (orange segments). Step 4: Identify the Hack n + 1 mouth segments having a Strahler value lower than 3. These, along with respective UDA and URL will be included in the LRU established for the previous hack n segments (red segments and respective UDA). Step 5: Identify the Hack n + 1 mouth segments having Strahler value ≥ 3 but not abiding by the other thresholds. Each one with its respective upstream segments, UDA and URL will constitute an individual SRU (green segments). Step 6: Identify the Hack n + 1 mouth segments abiding by all the thresholds established for LRU, these will be part of a new LRU to be established in the river basin. Establishing a new LRU starting in a Hack n + 1 mouth segment leads to a confluence between LRU. To maintain the dendritic and hierarchical nature of the network the previously established LRU in the Hack n segments will be split at this confluence (red segments). Step 7: The procedure to define the extent of the hack n + 1 LRU and to continue the process can now be taken back from step 2 onwards (since a new iteration will start, n will also increase accordingly). The procedure ends when all river segments of a given basin are included in one R2U (dark blue and orange segments).

3.1. Dataset Validation

The construction of this database departed from the CCM2 database [

12] which contains multiple layers and attributes to depict European rivers’ spatial and structural characteristics [

14]. By using CCM2 as source data, we took advantage of the set of validations and the spatial correctness it contains, thus avoiding for example topological errors. Also, by adopting the sea outlet basins identifiers from CCM2 it ensures interoperability between databases.

After the implementation and execution of the methodological procedure, the tabular output was verified and linked to spatial data using ArcGIS Pro ® (version 3.2.2). These outputs were then streamlined into a PostgreSQL relational database, a process which entailed data normalization into a relational model and a validation process. The set of rules and constraints implemented for validation enforces data integrity, accuracy and reliability while streamlining usage efficiency and effectiveness. The R2U dataset attributes were created to enable the possibility of being used for network analysis using for example ArcGIS Pro ® or RivTool [

15]. This possibility was validated using RivTool by creating a fully functional network file (made available via Open Science Framework:

https://osf.io/gp7xr/) that allows further river network calculations such for example connectivity indexes.

4. User Notes (Optional)

The River Restoration Units (R2U) are the result of a novel method for grouping river segments and their corresponding drainage areas across European river networks, aligning with river network functioning. Beyond the MERLIN and Dammed Fish projects [

10], this dataset has already been used to discuss the challenges of restoration targeting free-flowing rivers under the Nature Restoration Law [

11]. Furthermore, at the sea outlet basin level, the definition of small river units connected by large river units enables a simplification of the river network useful for river connectivity research and management at two different scales: (1) at the local scale, where we can calculate connectivity within R2U and test local connectivity restoration scenarios; and (2) at the basin-scale, where the inner connectivity of the mall river units and large river units (here acting as within-basin connectors) can be used to assess the overall basin connectivity and test for basin-wide connectivity restoration scenarios. The option, offered by river restoration units, to work at these two nested scales provides great computational benefits as this is a way of simplifying the problem without compromising accuracy. River biodiversity and processes are spatially influenced by the surrounding land patches and conditions [

29]. Therefore, R2U may expedite the integration of data covering multiple aspects such as land use, land cover, soil and geological properties, human social aspects and heritage, climate change and governance, enabling more holistic approaches. Another example of reusing this dataset would be to rely on the river restoration units as an intermediate scale between river segments and river basins in plans to upscale interventions in river networks (e.g., conservation actions), taking advantage of the nested nature of river networks. By allowing data integration into river management units with similar complexity and size that maintain the basic features of river network functioning, the sub-units created here provide a useful platform for data management at large spatial extents. Moreover, since the aggregation of river building blocks and consequent creation of river restoration units is made per river basin, the dataset preserves the insular nature of river basins which is crucial for management and conservation purposes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, GD, SB, TF and PB; methodology, GD, PS and PB; software, GD and AP; validation, GD, AP, PS, TL and FB; formal analysis, GD and AP; investigation, GD, PS and PB; resources, TF and PB; data curation, GD and AP; writing—original draft preparation, GD and PB; writing—review and editing, GD, AP, PS, TL, FB, AF, SB, TF and PB; visualization, GD, AP and TL; supervision, PS, SB, TF and PB; project administration, SB, TF and PB; funding acquisition, SB, TF and PB. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The development of this database was funded by MERLIN, a project funded under the European Commission’s Horizon 2020 programme under grant agreement No 101036337, and by Dammed Fish (PTDC/CTA-AMB/4086/2021 – DOI: 10.54499/PTDC/CTA-AMB/4086/2021), a project funded by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia I.P. (FCT). Forest Research Centre (CEF) is a research unit funded by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia I.P. (FCT), Portugal (UIDB/00239/2020; DOI: 10.54499/UIDB/00239/2020). The Associate Laboratory Laboratory for Sustainable Land Use and Ecosystem Services – TERRA is funded by the FCT (LA/P/0092/2020). GD has been financed by FCT within the project project Dammed Fish (PTDC/CTA-AMB/4086/2021 – DOI: 10.54499/PTDC/CTA-AMB/4086/2021). AP is currently supported by a contract under the project MERLIN (101036337—MERLIN—H2020-LC-GD-2020). TL was supported by a PhD grant from the FLUVIO–River Restoration and Management program funded by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia I. P. (FCT), Portugal (UI/BD/15052/2021). PB is financed by national funds via FCT (LA/P/0092/2020). AF was funded by the Christian Doppler Research Association (CD Laboratory MERI) as well as FB who was also supported by the AQUAINFRA project (grant agreement No 101094434).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The database and metadata are accessible via Zenodo (

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10753900) and the Open Science Platform (

https://osf.io/mk6ed/), downloadable without any registration requirements under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. The database is available in .sql but also in tabular format (.csv files), thus it can be opened in both proprietary and non-proprietary applications.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Lidija Globevnik for her contribution to early project discussions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CCM2 |

Catchment Characterisation and Modelling – River and Catchment Database v2.1 |

| RivTool |

River Network Toolkit software |

| R2U |

River Restoration Units |

| DOI |

Linear dichroism |

| EU MS |

Digital Object Identifier |

| LRU |

Member States of the European Union |

| LRU |

Large River Units |

| SRU |

Small River Units |

| UDA |

Upstream Drainage Area |

| URL |

Upstream River Length |

References

- Dudgeon, D. Multiple threats imperil freshwater biodiversity in the Anthropocene. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, R960–R967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsang, Y.-P.; Wieferich, D.; Fung, K.; Infante, D.M.; Cooper, A.R. An approach for aggregating upstream catchment information to support research and management of fluvial systems across large landscapes. SpringerPlus 2014, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fausch, K.D.; Torgersen, C.E.; Baxter, C.V.; Li, H.W. Landscapes to Riverscapes: Bridging the Gap between Research and Conservation of Stream Fishes: A Continuous View of the River is Needed to Understand How Processes Interacting among Scales Set the Context for Stream Fishes and Their Habitat. Bioscience 2002, 52, 483–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgersen, C.E.; Le Pichon, C.; Fullerton, A.H.; Dugdale, S.J.; Duda, J.J.; Giovannini, F.; Tales, É.; Belliard, J.; Branco, P.; Bergeron, N.E.; et al. Riverscape approaches in practice: perspectives and applications. Biol. Rev. 2022, 97, 481–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allan, J.D. Landscapes and Riverscapes: The Influence of Land Use on Stream Ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Ecol., Evol. Syst. 2004, 35, 257–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, E.H.; Lowe, W.H.; Fagan, W.F. Living in the branches: population dynamics and ecological processes in dendritic networks. Ecol. Lett. 2007, 10, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, G.; Segurado, P.; Oliveira, T.; Haidvogl, G.; Pont, D.; Ferreira, M.T.; Branco, P. The River Network Toolkit – RivTool. Ecography 2019, 42, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanford, J.A.; Alexander, L.C.; Whited, D.C. Chapter 1 - Riverscapes. In Methods in Stream Ecology, Volume 1 (Third Edition); Hauer, F.R., Lamberti, G.A., Eds.; Academic Press: Boston, 2017; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Dodds, P.S.; Rothman, D.H. Geometry of river networks. II. Distributions of component size and number. Physical review. E, Statistical, nonlinear, and soft matter physics 2001, 63, 016116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, G.; Peponi, A.; Leite, T.; Faro, A.; Moreno, D.; Anjinho, P.; Segurado, P.; Borgwardt, F.; Baattrup-Pedersen, A.; Herring, D.; et al. MERLIN Deliverable D3.1: Screening maps: Europe-wide maps of the needs and potentials to restore floodplains, rivers, and wetlands with a range of restoration measures; School of Agriculture, University of Lisbon: 31 March 2023 2023; p. 176 pp.

- Stoffers, T.; Altermatt, F.; Baldan, D.; Bilous, O.; Borgwardt, F.; Buijse, A.D.; Bondar-Kunze, E.; Cid, N.; Erős, T.; Ferreira, M.T.; et al. Reviving Europe’s rivers: Seven challenges in the implementation of the Nature Restoration Law to restore free-flowing rivers. WIREs Water 2024, n/a, e1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jager, A.; Vogt, J. Rivers and Catchments of Europe - Catchment Characterisation Model (CCM). 2007.

- Duarte, G.; Peponi, A.; Segurado, P.; Leite, T.; Borgwardt, F.; Funk, A.; Birk, S.; Ferreira, M.T.; Branco, P. River Restoration Units (R2U) Database. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Vogt, J.; Soille, P.; Jager, A.d.; Rimavičiūtė, E.; Mehl, W.; Foisneau, S.; Bódis, K.; Dusart, J.; Paracchini, M.L.; Haastrup, P.; et al. A pan-European River and Catchment Database; European Commission - Joint Research Centre - Institute for Environment and Sustainability: Luxembourg, 2007; p. 120. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, G.; Segurado, P.; Oliveira, T.; Haidvogl, G.; Pont, D.; Ferreira, M.T.; Branco, P. The River Network Toolkit (RivTool), 2019.

- Hack, J.T. Studies of longitudinal stream profiles in Virginia and Maryland; 294B; 1957.

- Strahler, A.N. Quantitative analysis of watershed geomorphology. Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union 1957, 38, 913–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strahler, A.N. Hypsometric (Area-Altitude) Analysis of Erosional Topography. Geological Society of America Bulletin 1952, 63, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paller, M.H. Relationships between Fish Assemblage Structure and Stream Order in South Carolina Coastal Plain Streams. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 1994, 123, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Wu, J.; Chen, J.; Wu, Q.; Lei, G. Freshwater fish biodiversity in the Yangtze River basin of China: patterns, threats and conservation. Biodiversity & Conservation 2003, 12, 1649–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Vorste, R.; McElmurray, P.; Bell, S.; Eliason, K.M.; Brown, B.L. Does Stream Size Really Explain Biodiversity Patterns in Lotic Systems? A Call for Mechanistic Explanations. Diversity 2017, 9, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacArthur, R.H.; Wilson, E.O. The theory of island biogeography; Princeton University Press: Princeton, New Jersey, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Oberdorff, T.; Guégan, J.-F.; Hugueny, B. Global Scale Patterns of Fish Species Richness in Rivers. Ecography 1995, 18, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passy, S.I.; Mruzek, J.L.; Budnick, W.R.; Leboucher, T.; Jamoneau, A.; Chase, J.M.; Soininen, J.; Sokol, E.R.; Tison-Rosebery, J.; Vilmi, A.; et al. On the shape and origins of the freshwater species-area relationship. Ecology 2022, n/a, e3917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000 establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water policy L 327 2000, 2000/60/CE, 93.

- Higgins, J.V.; Bryer, M.T.; Khoury, M.L.; Fitzhugh, T.W. A Freshwater Classification Approach for Biodiversity Conservation Planning. Conserv. Biol. 2005, 19, 432–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seliger, C.; Zeiringer, B. River Connectivity, Habitat Fragmentation and Related Restoration Measures. In Riverine Ecosystem Management: Science for Governing Towards a Sustainable Future; Schmutz, S., Sendzimir, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 171–186. [Google Scholar]

- Grill, G.; Lehner, B.; Thieme, M.; Geenen, B.; Tickner, D.; Antonelli, F.; Babu, S.; Borrelli, P.; Cheng, L.; Crochetiere, H.; et al. Mapping the world’s free-flowing rivers. Nature 2019, 569, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbonneau, P.; Fonstad, M.A.; Marcus, W.A.; Dugdale, S.J. Making riverscapes real. Geomorphology 2012, 137, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).