Submitted:

14 January 2025

Posted:

15 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Generation of Oxidative Stress and Status of Antioxidant Systems in I/R Hearts

3. Mechanisms of I/R-Injury Induced Subcellular Defects and Cardiac Dysfunction

4. Pharmacotherapy and Cardioprotection of I/R-Induced Injury

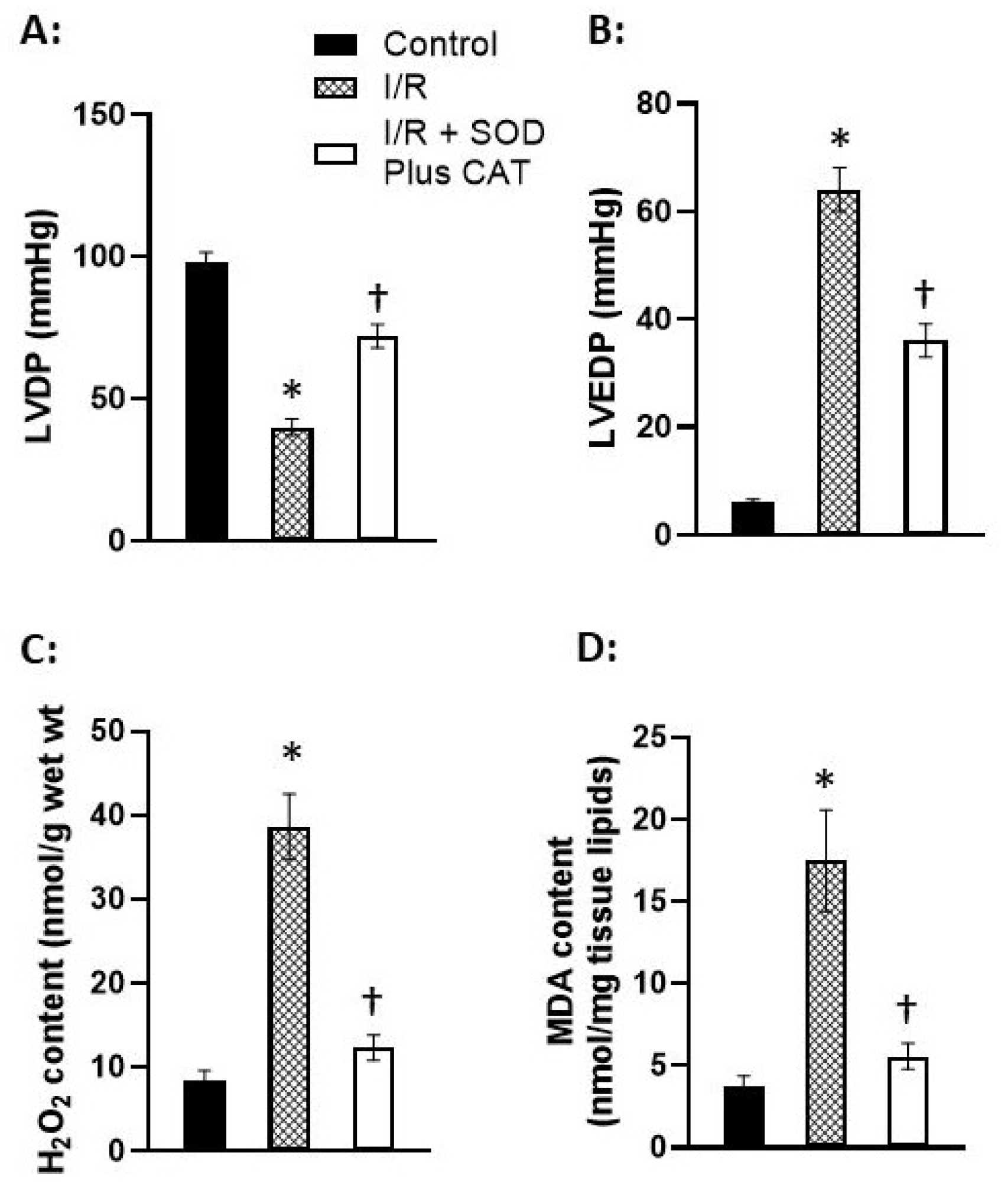

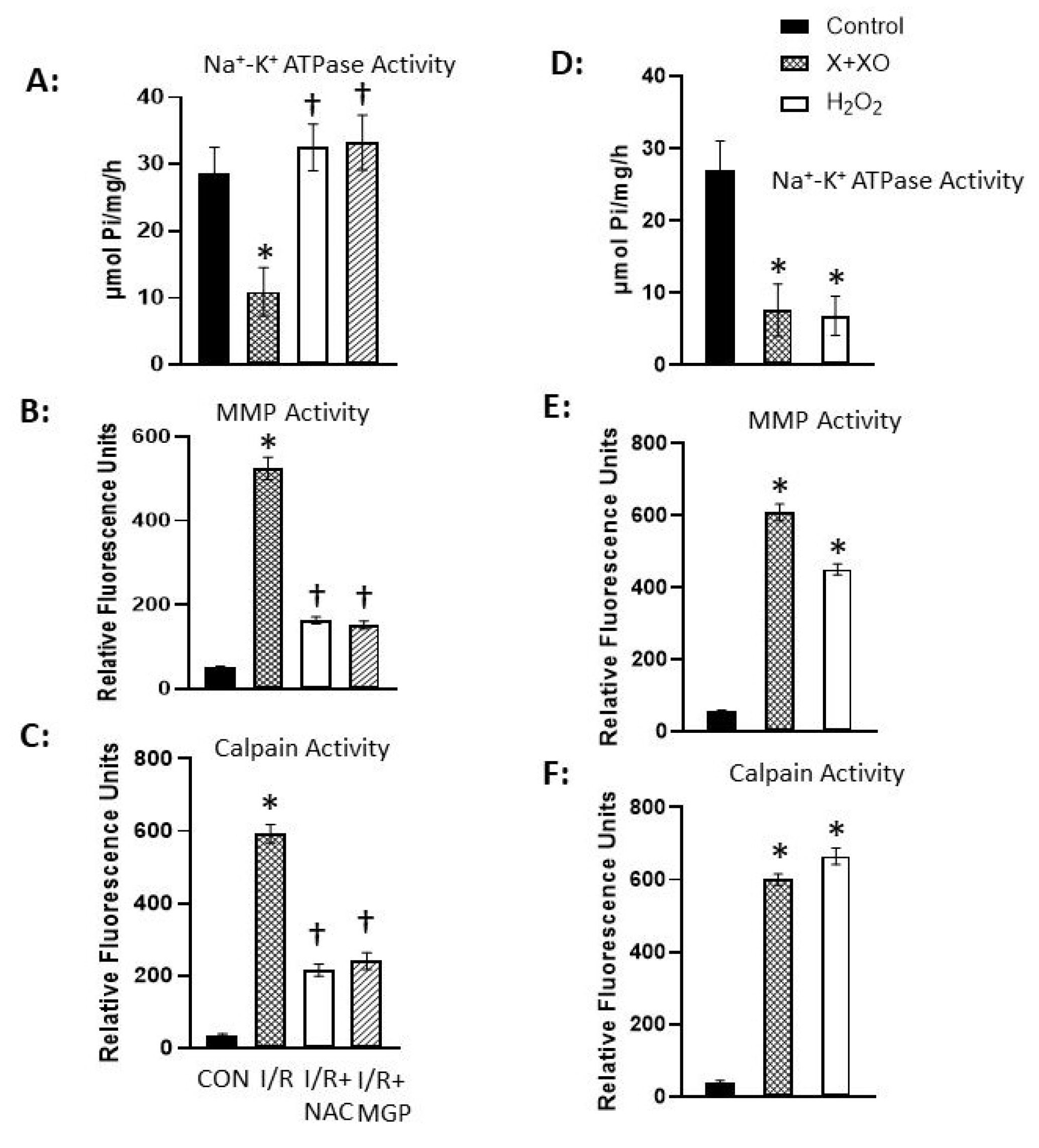

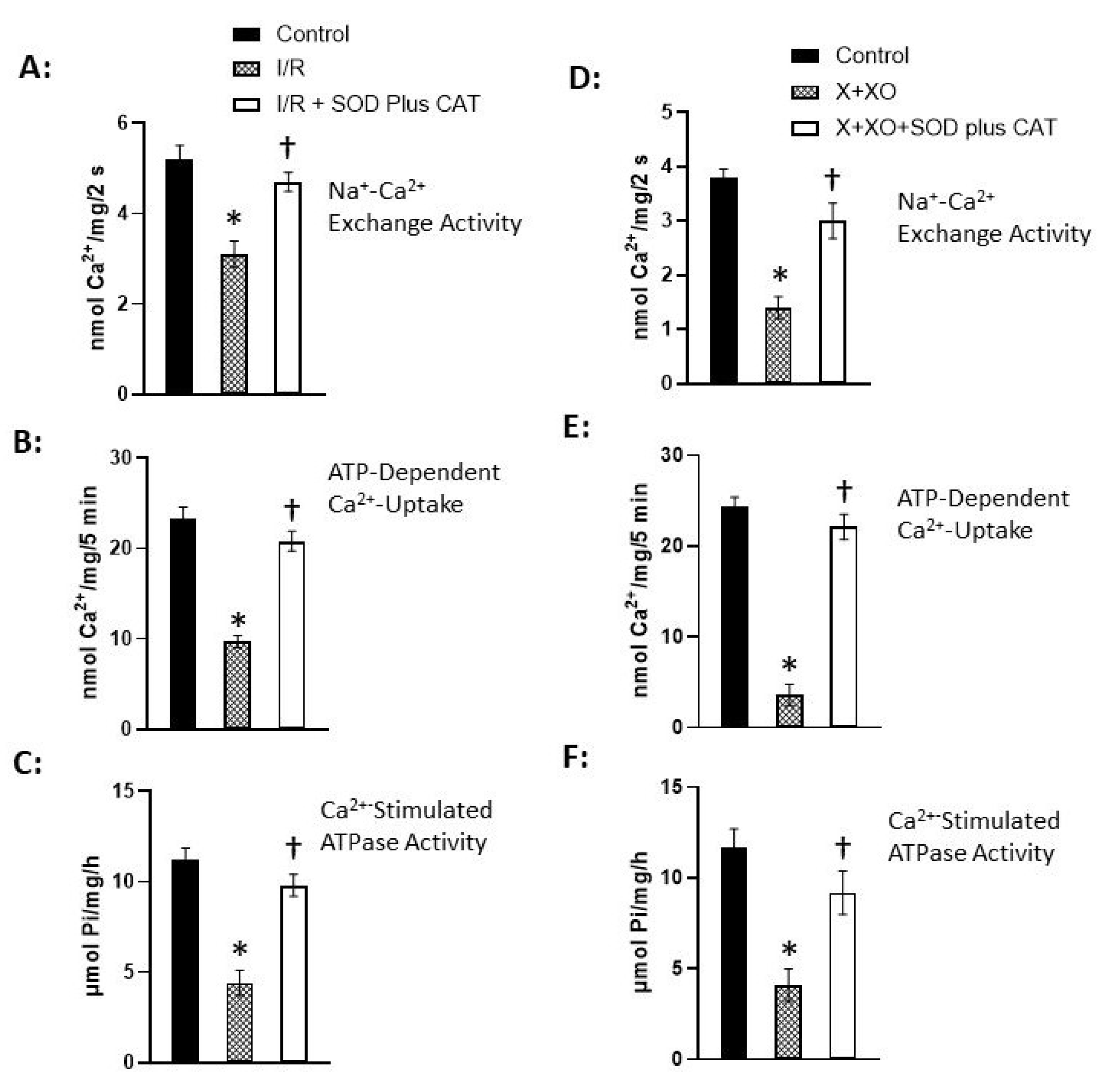

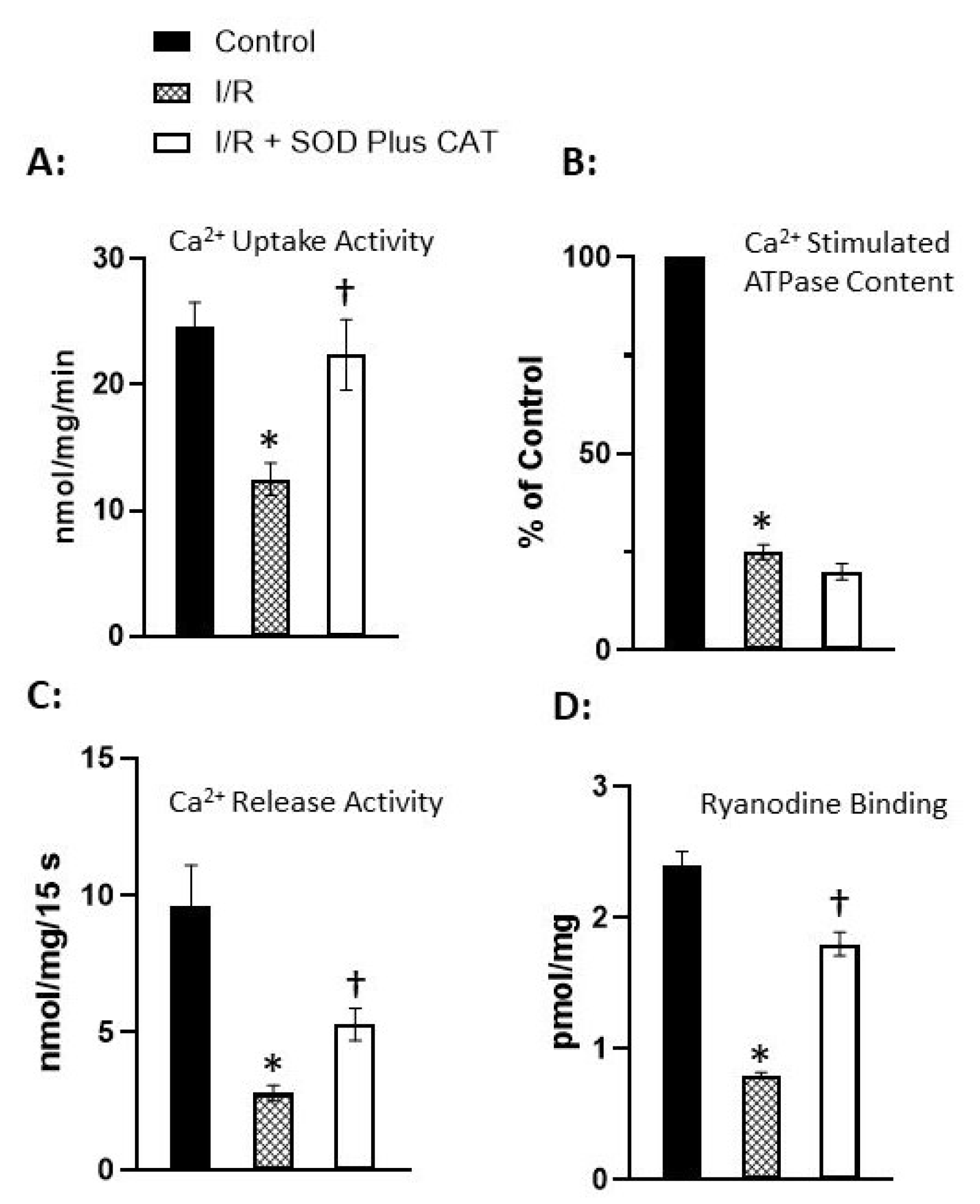

5. Evidence for the Involvement of Oxidative Stress in I/R-Induced Cardiac Dysfunction

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sharma, G.P.; Varley, K.G.; Kim, S.W.; Barwinsky, J.; Cohen, M.; Dhalla, N.S. Alterations in energy metabolism and ultrastructure upon reperfusion of the ischemic myocardium after coronary occlusion. Am J Cardiol 1975, 36, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayler, W.G.; Panagiotopoulos, S.; Elz, J.S.; Daly, M.J. Calcium-mediated damage during post-ischemic reperfusion. J Mol Cell Cardiol 1988, 20 (Suppl. 2), 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, J.G.; Smith, T.W.; Marsh, J.D. Mechanisms of reoxygenation-induced calcium overload in cultured chick embryo heart cells. Am J Physiol 1988, 254, H1133–H1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, R.B.; Reimer, K.A. The cell biology of acute myocardial ischemia. Annu Rev Med 1991, 42, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolli, R.; Marban, E. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of myocardial stunning. Physiol Rev 1999, 79, 609–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, M.H.; Meuter, K.; Schafer, C. Cellular mechanisms of ischemia-reperfusion injury. Ann Thorac Surg 2003, 75, S644–S648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, J.W.; Gilbert, T.B.; Poston, R.S.; Silldorff, E.P. Myocardial reperfusion injury: Etiology, mechanisms, and therapies. J Extra Corpor Technol 2004, 36, 391–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhalla, N.S.; Elmoselhi, A.B.; Hata, T.; Makino, N. Status of myocardial antioxidants in ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res 2000, 47, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuzil, J.; Rayner, B.S.; Lowe, H.C.; Witting, P.K. Oxidative stress in myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury: A renewed focus on a long-standing area of heart research. Redox Rep 2005, 10, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milei, J.; Grana, D.R.; Forcada, P.; Ambrosio, G. Mitochondrial oxidative and structural damage in ischemia-reperfusion in human myocardium. Current knowledge and future directions. Front Biosci 2007, 12, 1124–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhalla, N.S.; Saini, H.K.; Tappia, P.S.; Sethi, R.; Mengi, S.A.; Gupta, S.K. Potential role and mechanisms of subcellular remodeling in cardiac dysfunction due to ischemic heart disease. J Cardiovasc Med 2007, 8, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigo, R.; Libuy, M.; Feliu, F.; Hasson, D. Oxidative stress-related biomarkers in essential hypertension and ischemia-reperfusion myocardial damage. Dis Markers 2013, 35, 773–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, M.; Riezzo, I.; Pascale, N.; Pomara, C.; Turillazzi, E. Ischemia/reperfusion injury following acute myocardial infarction: A critical issue for clinicians and forensic pathologists. Mediators Inflamm 2017, 2017, 7018393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Chuang, C.C.; Zuo, L. Molecular characterization of reactive oxygen species in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Biomed Res Int 2015, 2015, 864946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurian, G.A.; Rajagopal, R.; Vedantham, S.; Rajesh, M. The role of oxidative stress in myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury and remodeling: Revisited. Oxidative Med Cell Longev 2016, 2016, 165450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morciano, G.; Pinton, P. Modulation of mitochondrial permeability transition pores in reperfusion injury: Mechanisms and therapeutic approaches. Eur J Clin Invest 2025, 55, e14331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, H.; Zhou, G.; Zhang, D.; Yang, Q.; Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Sun, J. Role of M6a Methylation in Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury and Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Cardiovasc Toxicol 2024, 24, 918–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, R.; Liu, H.; Li, X.; Lei, W.; Chen, J.; Jin, Z.; Tang, J.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wu, X. Glycogen synthase kinase-3β: A multifaceted player in ischemia-reperfusion injury and its therapeutic prospects. J Cell Physiol 2024, 239, e31335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balderas, E.; Lee, S.H.J.; Rai, N.K.; Mollinedo, D.M.; Duron, H.E.; Chaudhuri, D. Mitochondrial calcium regulation of cardiac metabolism in health and disease. Physiology 2024, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, E.; Aoki, T.; Endo, Y.; Kazmi, J.; Hagiwara, J.; Kuschner, C.E.; Yin, T.; Kim, J.; Becker, L.B.; Hayashida, K. Organ-specific mitochondrial alterations following ischemia-reperfusion injury in post-cardiac arrest syndrome: A comprehensive review. Life 2024, 14, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Xing, Z.; Xue, T.; Zhao, J.; Li, G.; Xu, L.; Sun, Q. Insulin-like growth factor-1 in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury: A review. Medicine 2024, 103, e37279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, R.; Yan, Y.; He, B.; Miao, C.; Fang, Y.; Wan, H.; Zhou, G. Exosomes-mediated signaling pathway: A new direction for treatment of organ ischemia-reperfusion injury. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, W.; Wen, Y.; Yang, S.; Duan, Y.; Liu, Z. Research progress and perspectives of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor in myocardial and cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury: A review. Medicine 2023, 102, e35490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omorou, M.; Huang, Y.; Gao, M.; Mu, C.; Xu, W.; Han, Y.; Xu, H. The forkhead box O3 (FOXO3): a key player in the regulation of ischemia and reperfusion injury. Cell Mol Life Sci 2023, 80, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeone, A.; Grano, M.; Brunetti, G. Tumor necrosis factor family members and myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury: State of the art and therapeutic implications. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 4606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popov, S.V.; Mukhomedzyanov, A.V.; Voronkov, N.S.; Derkachev, I.A.; Boshchenko, A.A.; Fu, F.; Sufianova, G.Z.; Khlestkina, M.S.; Maslov, L.N. Regulation of autophagy of the heart in ischemia and reperfusion. Apoptosis 2023, 28, 55–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahdiani, S.; Omidkhoda, N.; Rezaee, R.; Heidari, S.; Karimi, G. Induction of JAK2/STAT3 pathway contributes to protective effects of different therapeutics against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion. Biomed Pharmacother 2022, 155, 113751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.; Wu, J.; Yang, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, D.; Ma, J. Mitochondrial quality control in cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury: new insights into mechanisms and implications. Cell Biol Toxicol 2023, 39, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Liu, X.; Zhou, J.; Li, T. Mitochondrial DNA is a vital driving force in ischemia-reperfusion injury in cardiovascular diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2022, 2022, 6235747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Liu, D.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, D.; Rong, J.; Zhang, L.; Xia, Z. Myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury: Mechanisms of injury and implications for management. Exp Ther Med 2022, 23, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslov, L.N.; Popov, S.V.; Mukhomedzyanov, A.V.; Naryzhnaya, N.V.; Voronkov, N.S.; Ryabov, V.V.; Boshchenko, A.A.; Khaliulin, I.; Prasad, N.R.; Fu, F.; Pei, J.M.; Logvinov, S.V.; Oeltgen, P.R. Reperfusion cardiac injury: Receptors and the signaling mechanisms. Curr Cardiol Rev 2022, 18, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, Y.; Yu, M.L.; Lu, S.F. Purinergic signaling in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Purinergic Signal 2023, 19, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casin, K.M.; Calvert, J.W. Dynamic regulation of cysteine oxidation and phosphorylation in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cells 2021, 10, 2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Shi, D.; Guo, M. The roles of PKC-δ and PKC-ε in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Pharmacol Res 2021, 170, 105716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Chen, P.; Zhong, J.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; Chen, C. HIF-1α in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Mol Med Rep 2021, 23, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, S.; Kang, P.M. A systematic review on advances in management of oxidative stress-associated cardiovascular diseases. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Yu, H.; Zhang, S.; Huang, S.; Wei, Z.; Ren, K.; Jin, Y. Unraveling the complex interplay between Mitochondria-Associated Membranes (MAMs) and cardiovascular inflammation: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Int Immunopharmacol 2024, 141, 112930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Gong, N. Endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling modulates ischemia/reperfusion injury in the aged heart by regulating mitochondrial maintenance. Mol Med 2024, 30, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Dhalla, N.S. The role of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Y.; Zeng, J.; Jin, Q.; Chu, M.; Ji, K.; Wang, Z.; Li, L. Endoplasmic reticulum stress serves an important role in cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury. Exp Ther Med 2020, 20, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.K.; Bhullar, S.K.; Elimban, V.; Dhalla, N.S. Oxidative stress as a mechanism for functional alterations in cadiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhalla, N.S.; Elimban, V.; Shah, A.K.; Nusier, M. Mechanisms of cardiac dysfunction in heart failure due to myocardial infarction. J Integr Cardiol 2019, 2, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhalla, N.S.; Temsah, R.M.; Netticadan, T. Role of oxidative stress in cardiovascular diseases. J Hypertens 2000, 18, 655–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhalla, N.S.; Elimban, V.; Bartekova, M.; Adameova, A. Involvement of oxidative stress in the development of subcellular defects and heart disease. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, H.K.; Xu, Y.J.; Zhang, M.; Liu, P.P.; Kirshenbaum, L.A.; Dhalla, N.S. Role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and other cytokines in ischemia-reperfusion-induced injury in the heart. Exp Clin Cardiol 2005, 10, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ambrosio, G.; Zweier, J.L.; Flaherty, J.T. The relationship between oxygen radical generation and impairment of myocardial energy metabolism following post-ischemic reperfusion. J Mol Cell Cardiol 1991, 23, 1359–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinning, C.; Westermann, D.; Clemmensen, P. Oxidative stress in ischemia and reperfusion: Current concepts, novel ideas and future perspectives. Biomark Med 2017, 11, 11031–11040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartekova, M.; Barancik, M.; Ferenczyova, K.; Dhalla, N.S. Beneficial effects of N-acetylcysteine and N–N-mercaptopropionylglycine on Ischemia reperfusion injury in the heart. Curr Med Chem 2018, 25, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, R.; Ceconi, C.; Curello, S.; Guarnieri, C.; Caldarera, C.M.; Albertini, A.; Visioli, O. Oxygen-mediated myocardial damage during ischemia and reperfusion: Role of the cellular defenses against oxygen toxicity. J Mol Cell Cardiol 1985, 17, 937–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arduini, A.; Mezzetti, A.; Porreca, E.; Lapenna, D.; DeJulia, J.; Marzio, L.; Polidoro, G.; Cuccurullo, F. Effect of ischemia and reperfusion on antioxidant enzymes and mitochondrial inner membrane proteins in perfused rat heart. Biochim Biophys Acta 1988, 970, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhalla, N.S.; Shah, A.K.; Adameova, A.; Bartekova, M. Role of oxidative stress in cardiac dysfunction and subcellular defects due to ischemia-reperfusion injury. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- San-Martín-Martínez, D.; Serrano-Lemus, D.; Cornejo, V.; Gajardo, A.I.J.; Rodrigo, R. Pharmacological basis for abrogating myocardial reperfusion injury through a multi-target combined antioxidant therapy. Clin Pharmacokinet 2022, 61, 1203–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsushima, S.; Sadoshima, J. Yin and Yang of NADPH oxidases in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.L.; Zhang, L.; Jin, Z.; Kasumov, T.; Chen, Y.R. Mitochondrial redox regulation and myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2022, 322, C12–C23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Liu, Y.; Liang, Y.; Naruse, K.; Takahashi, K. Systematic understanding of pathophysiological mechanisms of oxidative stress-related conditions-diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases, and ischemia-reperfusion injury. Front Cardiovasc Med 2021, 8, 649785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Wang, Z.; Carmone, C.; Keijer, J.; Zhang, D. Role of oxidative DNA damage and repair in atrial fibrillation and ischemic heart disease. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 3838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dambrova, M.; Zuurbier, C.J.; Borutaite, V.; Liepinsh, E.; Makrecka-Kuka, M. Energy substrate metabolism and mitochondrial oxidative stress in cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury. Free Radic Biol Med 2021, 165, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, P.; Qu, C.; Rao, Z.; Wu, D.; Zhao, J. Bidirectional regulation mechanism of TRPM2 channel: role in oxidative stress, inflammation and ischemia-reperfusion injury. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1391355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, W.L.; Cai, M.R.; Zhang, M.Q.; Cui, S.; Zhang, T.R.; Cheng, W.H.; Wu, Y.H.; Ou, W.J.; Jia, Z.H.; Zhang, S.F. Chinese herbal medicine alleviates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by regulating endoplasmic reticulum stress. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2021, 2021, 4963346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiklund, L.; Sharma, A.; Patnaik, R.; Muresanu, D.F.; Sahib, S.; Tian, Z.R.; Castellani, R.J.; Nozari, A.; Lafuente, J.V.; Sharma, H.S. Upregulation of hemeoxygenase enzymes HO-1 and HO-2 following ischemia-reperfusion injury in connection with experimental cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation: Neuroprotective effects of methylene blue. Prog Brain Res 2021, 265, 317–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.; Maceyka, M.; Chen, Q. Targeting ER stress and calpain activation to reverse age-dependent mitochondrial damage in the heart. Mech Ageing Dev 2020, 192, 111380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubois-Deruy, E.; Peugnet, V.; Turkieh, A.; Pinet, F. Oxidative stress in cardiovascular diseases. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Cheng, C.K.; Zhang, C.L.; Huang, Y. Interplay between oxidative stress, cyclooxygenases, and prostanoids in cardiovascular diseases. Antioxid Redox Signal 2021, 34, 784–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugger, H.; Pfeil, K. Mitochondrial ROS in myocardial ischemia reperfusion and remodeling. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2020, 1866, 165768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Toan, S. Pathological roles of mitochondrial oxidative stress and mitochondrial dynamics in cardiac microvascular ischemia/reperfusion injury. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Murugesan, P.; Huang, K.; Cai, H. NADPH oxidases and oxidase crosstalk in cardiovascular diseases: novel therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Cardiol 2020, 17, 170–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fibbi, B.; Marroncini, G.; Naldi, L.; Peri, A. The Yin and Yang effect of the apelinergic system in oxidative stress. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 4745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, M.; Chen, J.; Li, X.; Zhuang, J. Intersection of the ubiquitin-proteasome system with oxidative stress in cardiovascular disease. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 12197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szyller, J.; Jagielski, D.; Bil-Lula, I. Antioxidants in arrhythmia treatment-still a controversy? A review of selected clinical and laboratory research. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adameova, A.; Shah, A.K.; Dhalla, N.S. Role of oxidative stress in the genesis of ventricular arrhythmias. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 4200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, X.; Chen, P.; Miao, L.; Yuan, X.; Yu, C.; Di, G. Ferroptosis in organ ischemia-reperfusion injuries: recent advancements and strategies. Mol Cell Biochem 2025, 480, 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Chen, X.; Li, X.; Wang, K. Molecular therapy of cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury based on mitochondria and ferroptosis. J Mol Med 2023, 101, 1059–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fratta Pasini, A.M.; Stranieri, C.; Busti, F.; Di Leo, E.G.; Girelli, D.; Cominacini, L. New insights into the role of ferroptosis in cardiovascular diseases. Cells 2023, 12, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Yan, Y.; Niu, F.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Su, G.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Qian, L.; Liu, P.; Xiong, Y. Ferroptosis: a cell death connecting oxidative stress, inflammation and cardiovascular diseases. Cell Death Discov 2021, 7, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lillo-Moya, J.; Rojas-Solé, C.; Muñoz-Salamanca, D.; Panieri, E.; Saso, L.; Rodrigo, R. Targeting ferroptosis against ischemia/reperfusion cardiac injury. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, K.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, K.; Deng, N.; Tian, Z.; Wu, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhang, F.; Jiang, Z. The role of ROS-induced pyroptosis in CVD. Front Cardiovasc Med 2023, 10, 1116509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, D.; Yu, P.; Zhang, J.; Yu, S. Research progress on the role of pyroptosis in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cells 2022, 11, 3271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adameova, A.; Horvath, C.; Abdul-Ghani, S.; Varga, Z.V.; Suleiman, M.S.; Dhalla, N.S. Interplay of oxidative stress and necrosis-like cell death in cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury: A focus on necroptosis. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinato, M.; Andersson, L.; Miljanovic, A.; Laudette, M.; Kunduzova, O.; Borén, J.; Levin, M.C. Role of perilipins in oxidative stress-implications for cardiovascular disease. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rongjin, H.; Feng, C.; Jun, K.; Shirong, L. Oxidative stress-induced protein of SESTRIN2 in cardioprotection effect. Dis Markers 2022, 2022, 7439878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, H.; Liu, Y.; Men, H.; Zheng, Y. Protective mechanism of humanin against oxidative stress in aging-related cardiovascular diseases. Front Endocrinol 2021, 12, 683151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, M.; Liang, Y.; Wang, C.; Naruse, K.; Takahashi, K. Treatment of oxidative stress with exosomes in myocardial ischemia. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Kang, P.M. Oxidative stress and antioxidant treatments in cardiovascular diseases. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Lai, L.; Xie, M.; Qiu, H. Insights of heat shock protein 22 in the cardiac protection against ischemic oxidative stress. Redox Biol 2020, 34, 101555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kura, B.; Szeiffova Bacova, B.; Kalocayova, B.; Sykora, M.; Slezak, J. Oxidative stress-responsive microRNAs in heart injury. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haramaki, N.; Stewart, D.B.; Aggarwal, S.; Ikeda, H.; Reznick, A.Z.; Packer, L. Networking antioxidants in the isolated rat heart are selectively depleted by ischemia-reperfusion. Free Radic Biol Med 1998, 25, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhalla, N.S.; Golfman, L.; Takeda, S.; Takeda, N.; Nagano, M. Evidence for the role of oxidative stress in acute ischemic heart disease: A brief review. Can J Cardiol 1999, 15, 587–593. [Google Scholar]

- Saini, H.K.; Machackova, J.; Dhalla, N.S. Role of reactive oxygen species in ischemic preconditioning of subcellular organelles in the heart. Antioxid Redox Signal 2004, 6, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhullar, S.K.; Shah, A.K.; Dhalla, N.S. Role of angiotensin II in the development of subcellular remodeling in heart failure. Explor Med 2021, 2, 352–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tappia, P.S.; Shah, A.K.; Ramjiawan, B.; Dhalla, N.S. Modification of ischemia/reperfusion-induced alterations in subcellular organelles by ischemic preconditioning. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 3425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhosale, G.; Sharpe, J.A.; Sundier, S.; Duchen, M. Calcium signaling as mediator of cell energy demand and a trigger to cell death. Ann NY Acad Sci 2015, 1350, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badalzadeh, R.; Mokhtari, B.; Yavari, R. Contribution of apoptosis in myocardial reperfusion injury and loss of cardioprotection in diabetes mellitus. J Physiol Sci 2015, 65, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, R.; Guardigli, G.; Mele, D.; Percoco, G.F.; Ceconi, C.; Curello, S. Oxidative stress during myocardial ischemia and heart failure. Curr Pharm Des 2004, 10, 1699–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neri, M.; Fineschi, V.; Di Paolo, M.; Pomara, C.; Riezzo, I.; Turillazzi, E.; Cerretani, D. Cardiac oxidative stress and inflammation cytokines response after myocardial infarction. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 2015, 13, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, H.; Hu, Y.; Guo, D.; Fang, X.; Chen, Y. Interplay of TNF-α, soluble TNF receptors and oxidative stress in coronary chronic total occlusion of the oldest patients with coronary heart disease. Cytokine 2020, 125, 154836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Qu, Y.; Chen, H.; Qian, J. Insight into long noncoding RNA-miRNA-mRNA axes in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury: The implications for mechanism and therapy. Epigenomics 2019, 11, 1733–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Sun, W.; Guo, Z.; Liu, B.; Yu, H.; Zhang, J. Long noncoding RNAs in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion inury. Oxidative Med Cell Longev 2021, 2021, 8889123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, Z.; Fan, Z.; Yang, Y.; Lu, C. Involvement of non-coding RNAs in the pathogenesis of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Int J Mol Med 2021, 47, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.F.; Yoshioka, J. The emerging role of thioredoxin-interacting protein in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther 2017, 22, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; He, M.; Ni, L.; He, K.; Su, K.; Deng, Y.; Li, Y.; Xia, H. The role of arachidonic acid metabolism in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cell Biochem Biophys 2020, 78, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartekova, M.; Adameova, A.; Gorbe, A.; Ferenczyova, K.; Pechanova, O.; Lazou, A.; Dhalla, N.S.; Ferdinandy, P.; Giricz, Z. Natural and synthetic antioxidants targeting cardiac oxidative stress and redox signaling in cardiometabolic diseases. Free Radic Biol Med 2021, 169, 446–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois-Deruy, E.; Peugnet, V.; Turkieh, A.; Pinet, F. Oxidative stress in cardiovascular diseases. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleikers, P.W.M.; Wingler, K.; Hermans, J.J.R.; Diebold, I.; Altenhofer, S.; Radermacher, K.A.; Janssen, B.; Gorlach, A.; Schmidt, H.H.H.W. NADPH oxidases as a source of oxidative stress and molecular target in ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Mol Med 2012, 90, 1391–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Smith, M.J. Metal profiling in coronary ischemia-reperfusion injury: Implications for KEAP1/NRF2 regulated redox signaling. Free Radic Biol Med 2024, 210, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Huang, C.; Liu, H.; Zhang, M.; Liu, L.; Zhai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, J.; Yang, J. The mechanism of the NFAT transcription factor family involved in oxidative stress response. J Cardiol 2024, 83, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Pan, W.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, M.; Yin, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Han, L.; Bai, J.; Jiang, T.; Li, H. Comprehensive overview of Nrf2-related epigenetic regulations involved in ischemia-reperfusion injury. Theranostics 2022, 12, 6626–6645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadrkhanloo, M.; Entezari, M.; Orouei, S.; Zabolian, A.; Mirzaie, A.; Maghsoudloo, A.; Raesi, R.; Asadi, N.; Hashemi, M.; Zarrabi, A.; Khan, H.; Mirzaei, S.; Samarghandian, S. Targeting Nrf2 in ischemia-reperfusion alleviation: From signaling networks to therapeutic targeting. Life Sci 2022, 300, 120561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mata, A.; Cadenas, S. The antioxidant transcription factor Nrf2 in cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 11939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarmohammadi, F.; Hayes, A.W.; Karimi, G. The cardioprotective effects of hydrogen sulfide by targeting endoplasmic reticulum stress and the Nrf2 signaling pathway: A review. Biofactors 2021, 47, 701–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucar, B.I.; Ucar, G.; Saha, S.; Buttari, B.; Profumo, E.; Saso, L. Pharmacological protection against ischemia-reperfusion injury by regulating the Nrf2-Keap1-ARE signaling pathway. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavakoli, R.; Tabeshpour, J.; Asili, J.; Shakeri, A.; Sahebkar, A. Cardioprotective effects of natural products via the Nrf2 signaling pathway. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 2021, 19, 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, Y.; Lei, H.; Cai, Y.; Shen, J.; Zhu, P.; He, Q.; Zhao, M. The Nrf-2/HO-1 signaling axis: A ray of hope in cardiovascular diseases. Cardiol Res Pract 2020, 2020, 5695723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakavand, H.; Aghakouchakzadeh, M.; Coons, J.C.; Talasaz, A.H. Pharmacologic prevention of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2021, 77, 430–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osorio-Llanes, E.; Villamizar-Villamizar, W.; Ospino Guerra, M.C.; Díaz-Ariza, L.A.; Castiblanco-Arroyave, S.C.; Medrano, L.; Mengual, D.; Belón, R.; Castellar-López, J.; Sepúlveda, Y.; Vásquez-Trincado, C.; Chang, A.Y.; Bolívar, S.; Mendoza-Torres, E. Effects of metformin on ischemia/reperfusion injury: New evidence and mechanisms. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, T.; Zhang, D. Research progress on the effects of novel hypoglycemic drugs in diabetes combined with myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Ageing Res Rev 2023, 86, 101884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragasevic, N.; Jakovljevic, V.; Zivkovic, V.; Draginic, N.; Andjic, M.; Bolevich, S.; Jovic, S. The role of aldosterone inhibitors in cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 2021, 99, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, X.; Zhu, C.; Wang, W.; Li, M.; Ma, C.; Gao, B. SIRT1 is a regulator of autophagy: Implications for the progression and treatment of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion. Pharmacol Res 2024, 199, 106957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Zhu, X.; Xing, C.; Chen, Y.; Bian, H.; Yin, H.; Gu, X.; Su, L. Stimulator of interferon genes (STING): Key therapeutic targets in ischemia/reperfusion injury. Biomed Pharmacother 2023, 167, 115458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, R.; Wu, W.; Sun, Z.; Li, Z. AMP-activated protein kinase: An attractive therapeutic target for ischemia-reperfusion injury. Eur J Pharmacol 2020, 888, 173484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Huang, H.; Roy, S.; Song, Z.; Guo, B. Recent advances in nanomedicines for imaging and therapy of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Control Release 2023, 353, 563–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, I.; Barale, C.; Melchionda, E.; Penna, C.; Pagliaro, P. Platelets and cardioprotection: The role of nitric oxide and carbon oxide. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 6107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryter, S.W. Therapeutic potential of heme oxygenase-1 and carbon monoxide in acute organ injury, Critical illness, and inflammatory disorders. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Li, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, S.; Ren, Y. Construction of preclinical evidence for propofol in the treatment of reperfusion injury after acute myocardial infarction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed Pharmacother 2024, 174, 116629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, H.; Zhang, Q.; Chang, S.; Zhao, X.; Wang, M.; Li, W. Adiponectin protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis of preclinical animal studies. Lipids Health Dis 2024, 23, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.Y.; Liu, Z.; Lu, J.H.; Yang, S.Y.; Hu, X.Y.; Liang, G.Y. The function of circular RNAs in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury: Underlying mechanisms and therapeutic advancement. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2024. [On line ahed of print]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, T.; Ning, B.; Wu, Y.; Chen, X.; Qi, H.; Wang, H.; Zhao, M. MicroRNA-specific therapeutic targets and biomarkers of apoptosis following myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Mol Cell Biochem 2024, 479, 2499–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.; Cai, R.P.; Su, Y.M.; Wu, Q.; Su, Q. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomal noncoding RNAs as alternative treatments for myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury: Current status and future perspectives. J Cardiovasc Transl Res 2023, 16, 1085–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Zhou, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; An, N.; Yang, F.; Zhang, G.; Yuan, C.; Chen, H.; Wu, H.; Xing, Y. Protective effects of natural products against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion: Mitochondria-targeted therapeutics. Biomed Pharmacother 2022, 149, 112893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Yu, L.T.; Cheng, B.R.; Xu, J.L.; Cai, Y.; Jin, J.L.; Feng, R.L.; Xie, L.; Qu, X.Y.; Li, D.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Cui, X.Y.; Lu, J.J.; Zhou, K.; Lin, Q.; Wan, J. Promising therapeutic candidate for myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury: What are the possible mechanisms and roles of phytochemicals? Front Cardiovasc Med 2022, 8, 792592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauerhofer, C.; Grumet, L.; Schemmer, P.; Leber, B.; Stiegler, P. Combating ischemia-reperfusion injury with micronutrients and natural compounds during solid organ transplantation: Data of clinical trials and lessons of preclinical findings. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 10675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshitomi, T.; Nagasaki, Y. Self-assembling antioxidants for ischemia-reperfusion injuries. Antioxid Redox Signal 2022, 36, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ertugrul, I.A.; van Suylen, V.; Damman, K.; de Koning, M.L.Y.; van Goor, H.; Erasmus, M.E. Donor heart preservation with hydrogen sulfide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 5737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, N.; Zhang, G.; Li, Y.; Yuan, C.; Yang, F.; Zhang, L.; Gao, Y.; Xing, Y. Promising antioxidative effect of berberine in cardiovascular diseases. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 865353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baliou, S.; Adamaki, M.; Ioannou, P.; Pappa, A.; Panayiotidis, M.I.; Spandidos, D.A.; Christodoulou, I.; Kyriakopoulos, A.M.; Zoumpourlis, V. Protective role of taurine against oxidative stress. Mol Med Rep 2021, 24, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prem, P.N.; Sivakumar, B.; Boovarahan, S.R.; Kurian, G.A. Recent advances in potential of Fisetin in the management of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury-A systematic review. Phytomedicine 2022, 101, 154123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferenczyova, K.; Kalocayova, B.; Bartekova, M. Potential implications of quercetin and its derivatives in cardioprotection. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Wang, X. Protective effects of polydatin on multiple organ ischemia-reperfusion injury. Bioorg Chem 2020, 94, 103485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H.; Xu, Y.; Liehn, E.A.; Rusu, M. Vitamin C as scavenger of reactive oxygen species during healing after myocardial infarction. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, A.K.; Dhalla, N.S. Effectiveness of some vitamins in the prevention of cardiovascular disease: A narrative review. Front Physiol 2021, 12, 729255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kura, B.; Slezak, J. The protective role of molecular hydrogen in ischemia/reperfusion injury. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 7884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saengsin, K.; Sittiwangkul, R.; Chattipakorn, S.C.; Chattipakorn, N. Hydrogen therapy as a potential therapeutic intervention in heart disease: from the past evidence to future application. Cell Mol Life Sci 2023, 80, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, L.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, F. Protective mechanism and clinical application of hydrogen in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Pak J Biol Sci 2020, 23, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Wu, S.; Mao, C.; Qu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Xie, Y.; Jiang, D.; Song, Y. Therapeutic potential of hydrogen sulfide in ischemia and reperfusion injury. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheitasi, I.; Akbari, G.; Savari, F. Physiological and cellular mechanisms of ischemic preconditioning microRNAs-mediated in underlying of ischemia/reperfusion injury in different organs. Mol Cell Biochem 2024. [Online ahead of print]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.B.; Hryshko, L.; Freed, D.; Dhalla, N.S. Activation of proteolytic enzymes and depression of the sarcolemma Na+-K+-ATPase in ischemia-reperfused heart may be mediated through oxidative stress. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 2012, 90, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

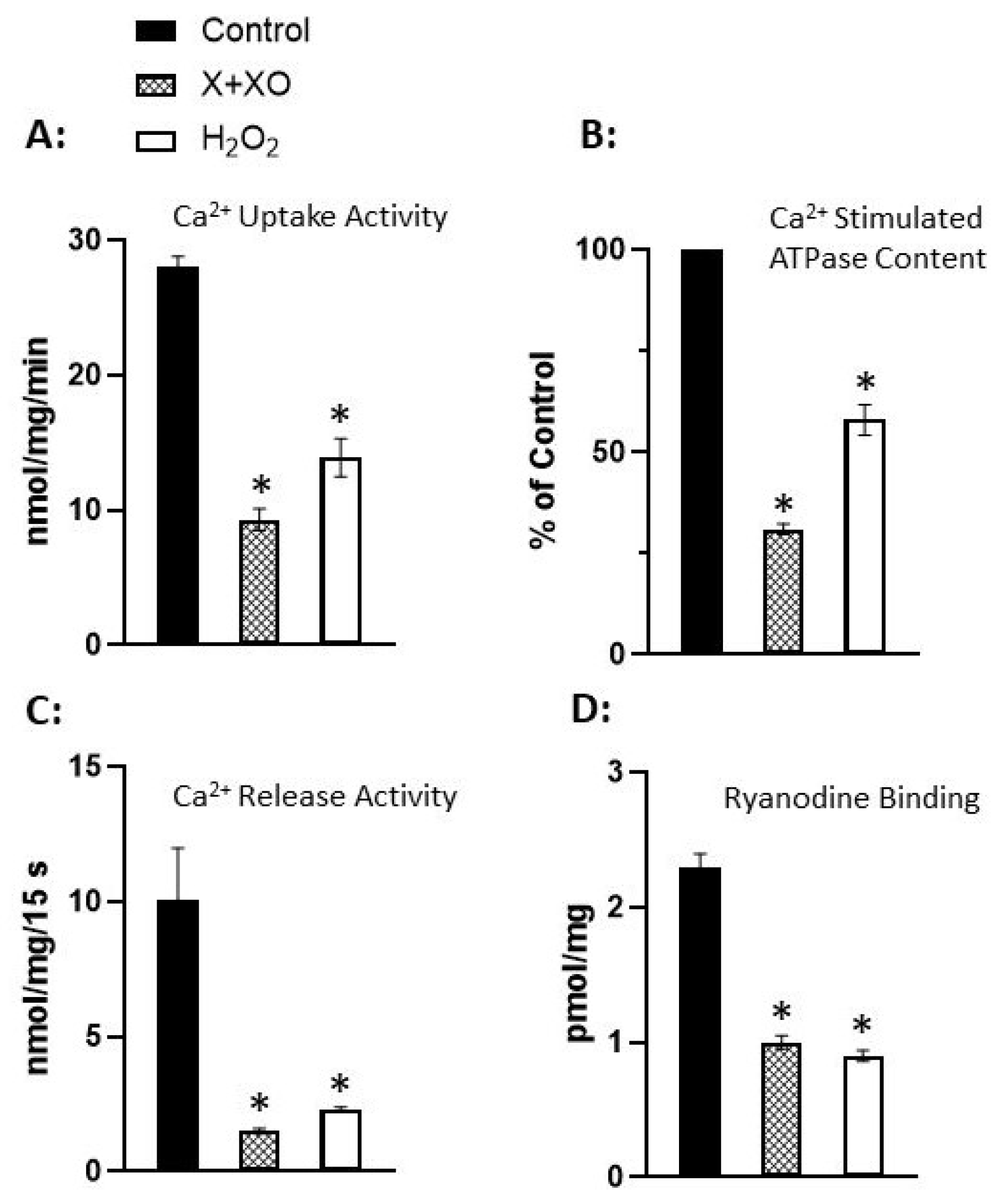

- Dixon, I.M.C.; Kaneko, M.; Hata, T.; Panagia, V.; Dhalla, N.S. Alterations in cardiac membrane Ca2+ transport during oxidative stress. Mol Cell Biochem 1990, 99, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsubara, T.; Dhalla, N.S. Effect of oxygen free radicals on cardiac contractile activity and sarcolemmal Na+-Ca2+ exchange. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther 1996, 1, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsubara, T.; Dhalla, N.S. Relationship between mechanical dysfunction and depression of sarcolemmal Ca2+-pump activity in hearts perfused with oxygen free radicals. Mol Cell Biochem 1996, 160/161, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temsah, R.M.; Netticadan, T.; Chapman, D.; Takeda, S.; Mochizuki, S.; Dhalla, N.S. Alterations in sarcoplasmic reticulum function and gene expression in ischemic-reperfused rat heart. Am J Physiol 1999, 277, H584–H594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

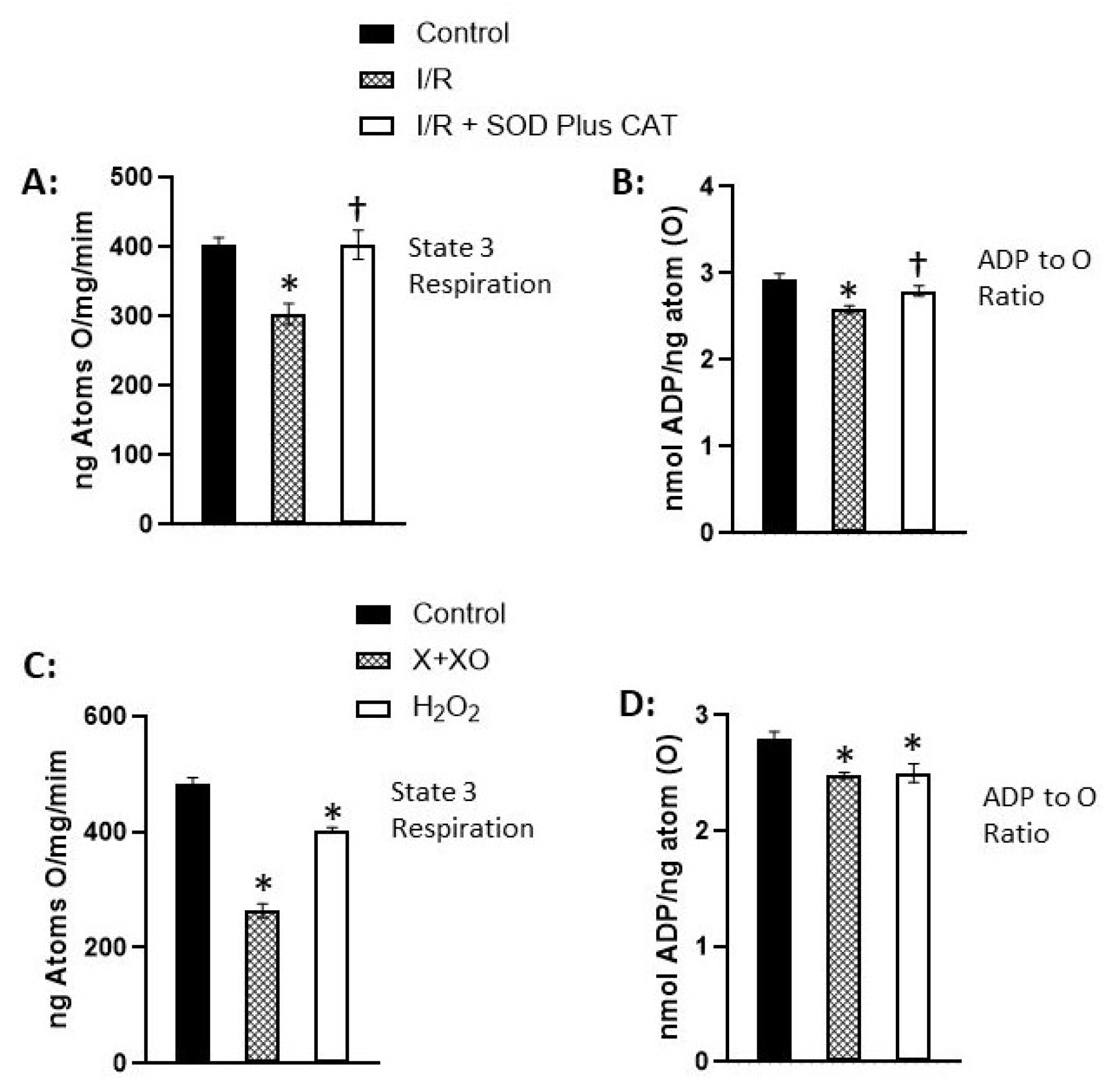

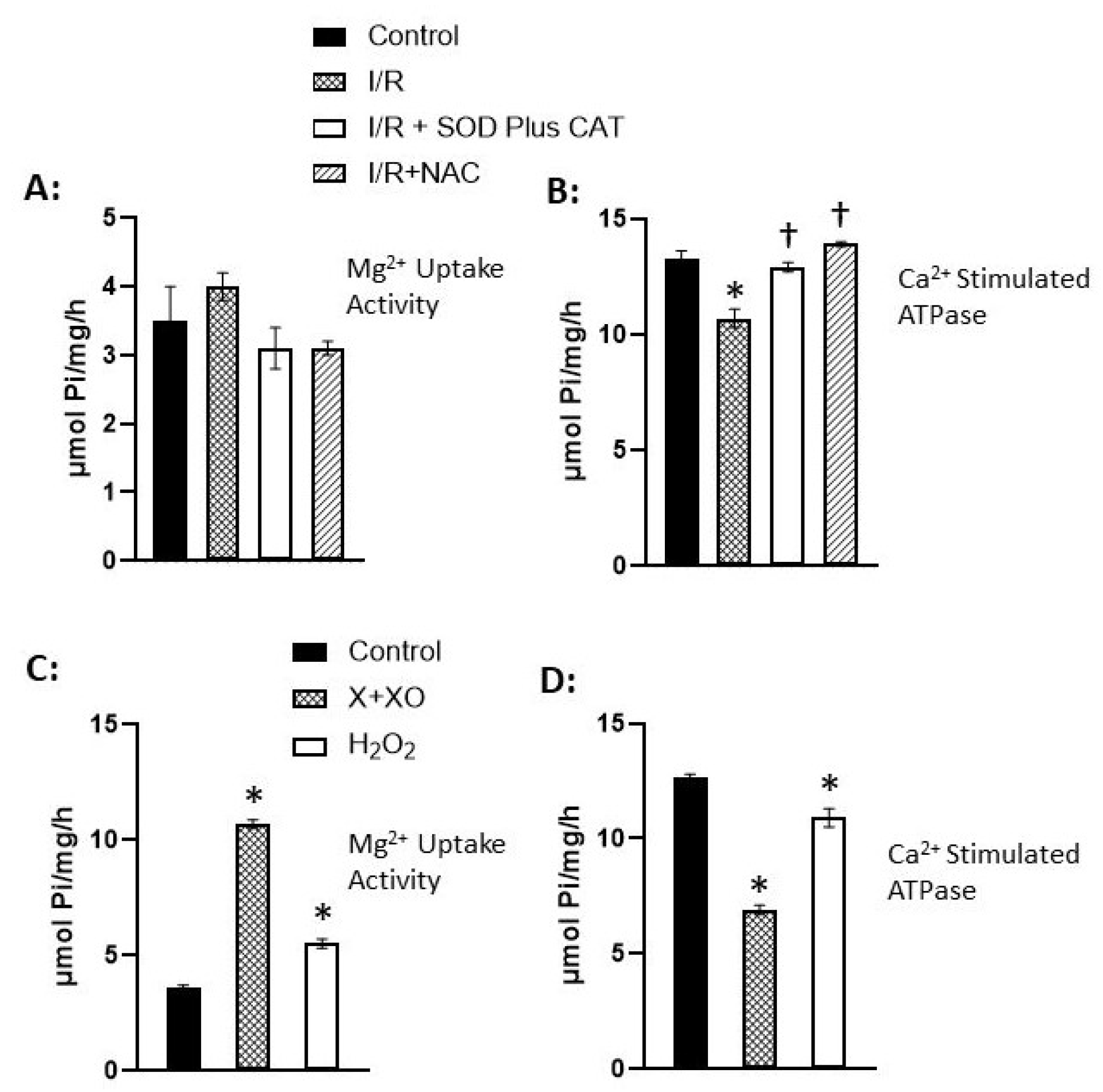

- Makazan, Z.; Saini, H.K.; Dhalla, N.S. Role of oxidative stress in alterations of mitochondrial function in ischemic-reperfused hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2007, 292, H1986–H1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddika, S.; Elimban, V.; Chapman, D.; Dhalla, N.S. Role of oxidative stress in ischemia-reperfusion-induced alterations in myofibrillar ATPase activities and gene expression in the heart. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 2009, 87, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, S.; Kaneko, M.; Chapman, D.C.; Dhalla, N.S. Alterations in cardiac contractile proteins due to oxygen free radicals. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1991, 1074, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).