1. Introduction

The prevention of secondary caries around bonded restorations triggered by bacterial growth and infiltration into the bonding interface is currently a problematic challenge, and many investigations have focused on it. A method is urgently required to preserve the bonding quality and performance over time [

1,

2,

3]. Therefore, developing antibacterial, biocompatible, and strong dental adhesives with mechanical and physical properties that match the rate of bacterial growth inhibition is a valuable pursuit.

Ionic liquids are organic salts formed by aliphatic chains connected to a high molecular weight cation associated with a low molecular weight anion [

13,

14]. Organic molecules, such as pyridine and imidazole, are commonly used to synthesize pyridinium and imidazolium-based ionic liquids, respectively [

15,

16]. Among these, imidazole is well known for its biocompatibility and antifungal effect. Ionic liquids can present a broad-spectrum antimicrobial property, affecting gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, mycobacteria, and fungi [

17]. In the pharmaceutical industry, these salts are associated with polymers for drug delivery systems to participate in antibacterial polymer coating synthesis and other processes [

18].

In dentistry, imidazolium ionic liquids have already been used to coat titanium implants, testing their adherence to the implant and their antimicrobial and anti-corrosion properties [

19]. In another study, an imidazolium ionic liquid was used with silver nanoparticles to disinfect root canals against Enterococcus faecalis. This material demonstrated greater fibroblast viability than 2.5% sodium hypochlorite and 0.2% chlorhexidine solutions [

20].

More recently, the ionic liquid 1-n-butyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate (BMI.BF4) was used to functionalize titanium dioxide quantum dots embedded in an experimental adhesive resin. Its incorporation associated with titanium dioxide quantum dots resulted in immediate and long-term antibacterial activity without showing cytotoxic effects on pulp cells [

21]. Another ionic liquid, 1-n-butyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (BMI.NTf

2), shows the same cation but an anion (bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide, NTf

2) with higher hydrophobicity compared to the previously used tetrafluoroborate (BF

4), which could bring advantages to dental polymeric materials.

This increased hydrophobicity enhances the durability of dental polymers by reducing their susceptibility to water absorption. Materials that absorb less water are less likely to undergo hydrolytic degradation, which can weaken their structural integrity and shorten their useful life. Consequently, BMI.NTf2 can help extend the longevity of dental restorations. Additionally, the reduced water uptake facilitated by NTf2 helps maintain the mechanical stability of dental polymers. Water absorption can cause swelling, adversely affecting the mechanical properties of these materials. By minimizing this absorption, BMI.NTf2 ensures that the polymers retain their strength and functional integrity within the moist environment of the oral cavity.

Furthermore, the hydrophobic nature of NTf2 minimizes the adhesion of bacteria and the absorption of staining agents, common issues in dental applications. This property not only helps maintain the aesthetic appearance of dental restorations but also promotes better oral hygiene by reducing the potential for bacterial growth on the surface of the materials.

The chemical stability and non-reactivity of NTf2 also make BMI.NTf2 is highly compatible with various existing dental materials, such as composites and adhesives. This compatibility allows for the flawless integration of this ionic liquid into current dental formulations without necessitating significant adjustments in production processes.

To initiate studies with BMI.NTf

2, this ionic liquid, was tested in an experimental resin, demonstrating an antimicrobial effect against Streptococcus mutans and no cytotoxicity against human cells keratinocytes when tested up to 5 wt.% [

22]. In the present study, BMI.NTf

2 was incorporated into an experimental adhesive resin and tested at 1, 2.5, and 5 wt.%. This study aimed to analyze the physical and chemical properties of the adhesives with BMI.NTf2. In this study, we designed BMI.NTf

2 containing adhesives with different concentrations (control = no addition of BMI.NTf

2, 1%, 2.5%, 5%), and we investigated the concentration-dependent changes in their physico-chemical and mechanical properties in vitro.

2. Materials and Methods

This is an in vitro and controlled study. The analyzed factor was the different concentrations (control group = no addition of BMI.NTf2, 1 wt.%, 2 wt.%, or 5 wt.%) of ionic liquid added to the adhesive.

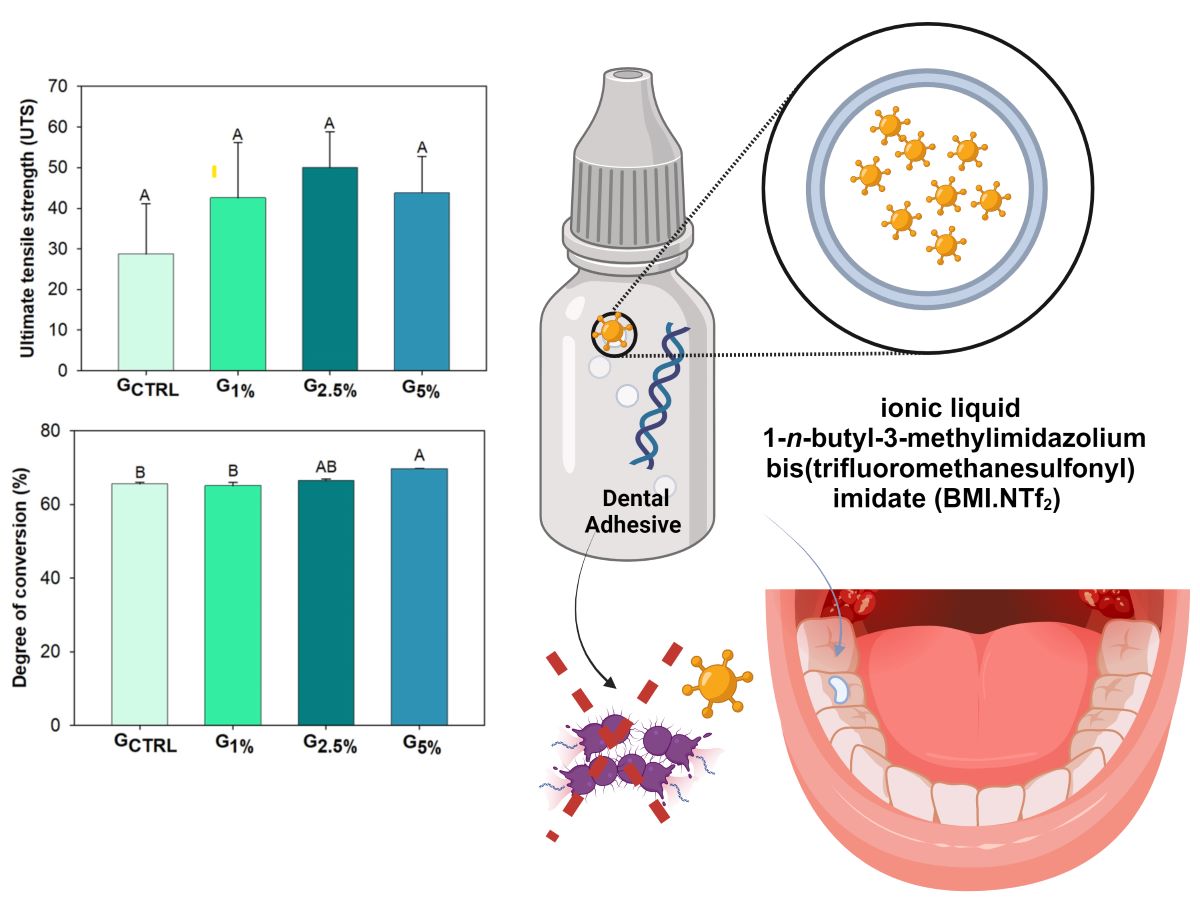

2.1. Formulation of Adhesive Resins

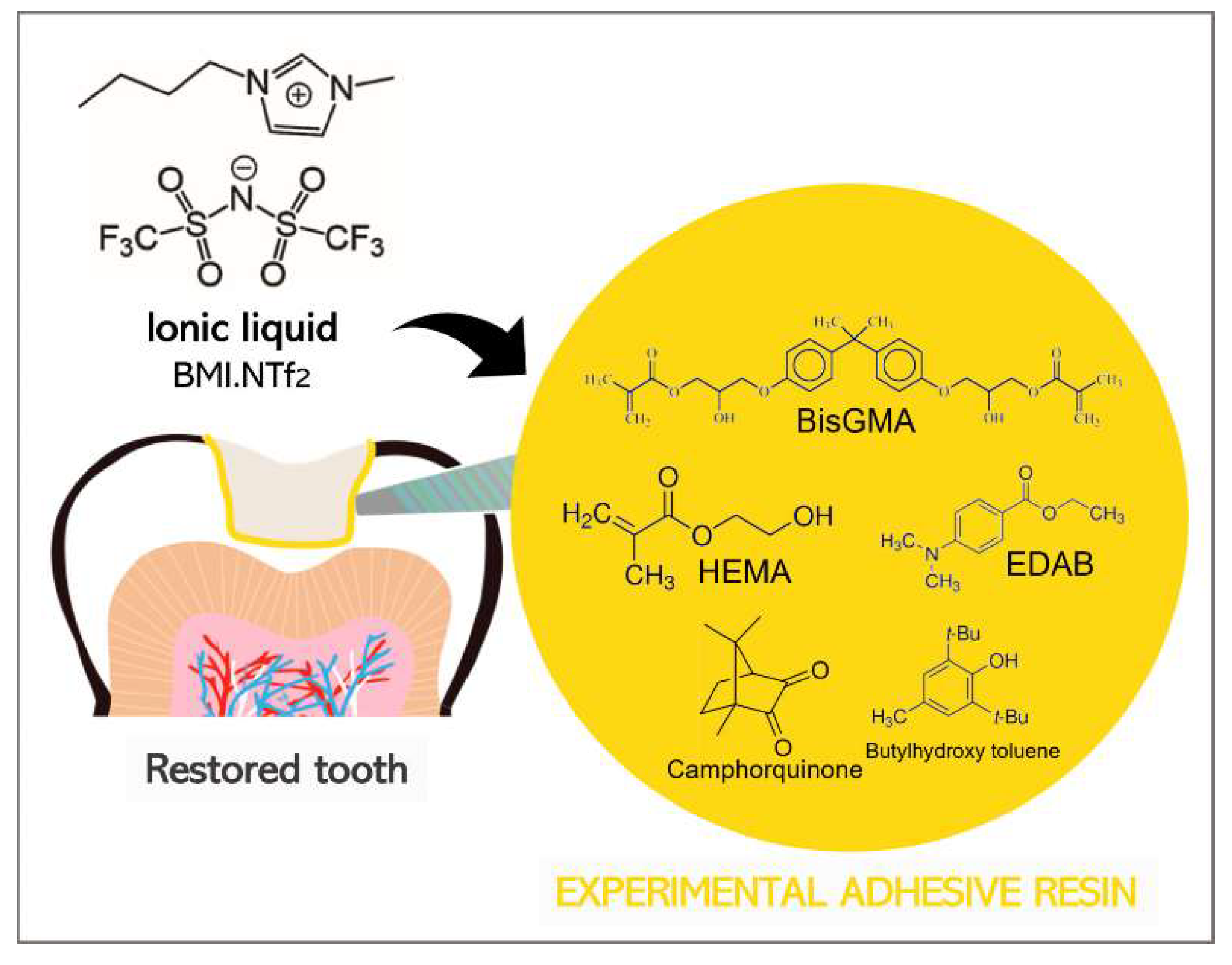

The adhesive resins were formulated by blending 66.66 wt.% bisphenol A glycerolate dimethacrylate (BisGMA) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) and 33.33 wt.% 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA). Camphorquinone (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) and ethyl 4-dimethylamino benzoate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) were added as a photoinitiator system in 1 mol %. Butylhydroxy toluene (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) was added as a polymerization inhibitor at 0.01 wt.%. The ionic liquid 1-

n-butyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (BMI.NTf

2) was formulated according to a previous study [

22] and incorporated at 1 (G

1%), 2.5 (G

2.5%), and 5 (G

5%) wt.% in the adhesive resin. A control group (G

CTRL) was formulated without BMI.NTf

2. An illustration of the ionic liquid BMI.NTf

2 incorporated into the adhesive is shown schematically in

Figure 1. All specimens were light-cured using a light-emitting diode (LED, Radii Cal, SDI, Bayswater, Victoria, Australia) at 1200 mW/cm

2 and kept in distilled water for 24 h at 37 °C before testing, except for specimens of polymerization kinetics and degree of conversion (DC), which were prepared during the tests.

2.2. Polymerization Kinetics and Degree of Conversion (DC)

The polymerization kinetics and degree of conversion (DC) were evaluated by Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (Bruker Optics, Ettinger, Germany) with a spectrometer equipped with an attenuated total reflectance (ATR) device consisting of a horizontal diamond crystal. Three samples per group (

n = 3) were dispensed onto the ATR using an auxiliary polyvinylsiloxane matrix with a 4 mm diameter and 1 mm thickness to standardize the samples’ thickness. The LED unit tip was standardized and positioned as close as possible to the top of each sample. The absorbance spectra were obtained during 40 seconds of adhesive photoactivation. Data were evaluated using the Opus 6.5 software (Bruker Optics), in the range of 4000-800 cm

-1 with 2 scans per second, at a speed of 160 kHz and resolution of 4 cm

-1. The DC was calculated based on the height of the following absorption peaks: 1640 cm

-1 (aliphatic C=C bond) and 1610 cm

-1 (aromatic C=C bond), which was used as an internal standard (Equation 1). The DC result was expressed as percentages. The DC calculated the polymerization rate (Rp) as a function of the light-activation time [

23].

Equation 1:

2.3. Softening in Solvent

Five samples from each group (

n = 5) were prepared with 5 mm diameter and 1 mm thickness after light-curing for 20 s on each side. After the polymerization, the samples were stored in distilled water for 24 h at 37 °C. Then, the samples were bonded with double-face tape on a glass table and soaked in self-cure acrylic resin. Each acrylic resin set contained five samples per group, which were polished using sandpapers (600, 1200, 2000-grit) and distilled water followed by felt disks with 0.5 μm alumina suspension (Fortel, São Paulo, SP, Brazil). After 24 h, the samples were subjected to a microhardness test in which five indentations (10 g for 5 s) were performed per sample at 40x magnification (HMV 2, Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan) to obtain the initial Knoop hardness number (KHN1). The samples were immersed in a solvent solution (70% ethanol and 30% water) for two hours, washed with distilled water, and tested again to obtain the final Knoop hardness number (KHN2). The Knoop hardness values were recorded as the five indentations per sample average. Softening in solvent (ΔKHN) was calculated by the percentage difference between KHN1 and KHN2 for each group [

26].

2.4. Ultimate Tensile Strength

An hourglass-shaped metal mold (8.0 mm long x 2.0 mm wide x 1.0 mm thick and 1 mm

2 in constriction area) was used to prepare five samples per group (

n = 5). The samples were light-cured for 20 s on each side. After 24 h, the samples were kept in distilled water at 37 °C, and the samples were measured in the constriction area using a digital caliper. Then, the samples were fixed with cyanoacrylate resin into jigs. The samples were submitted to tensile strength in a universal testing machine (Series EZ-SX, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) at 1 mm/min until the fracture of the samples. The force values (N) were divided by the constriction area of each sample and reported as MPa [

24,

25].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The physical and chemical properties of the adhesives were statistically analyzed using SigmaPlot software (version 12.0, Systat Software, San Jose, CA, USA). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to analyze the data distribution. DC, UTS, KHN1, and ΔKHN were analyzed via one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc test. Differences between KHN1 and KHN2 within each group were assessed using paired t tests. All tests were analyzed with a significance level of 0.05.

3. Results

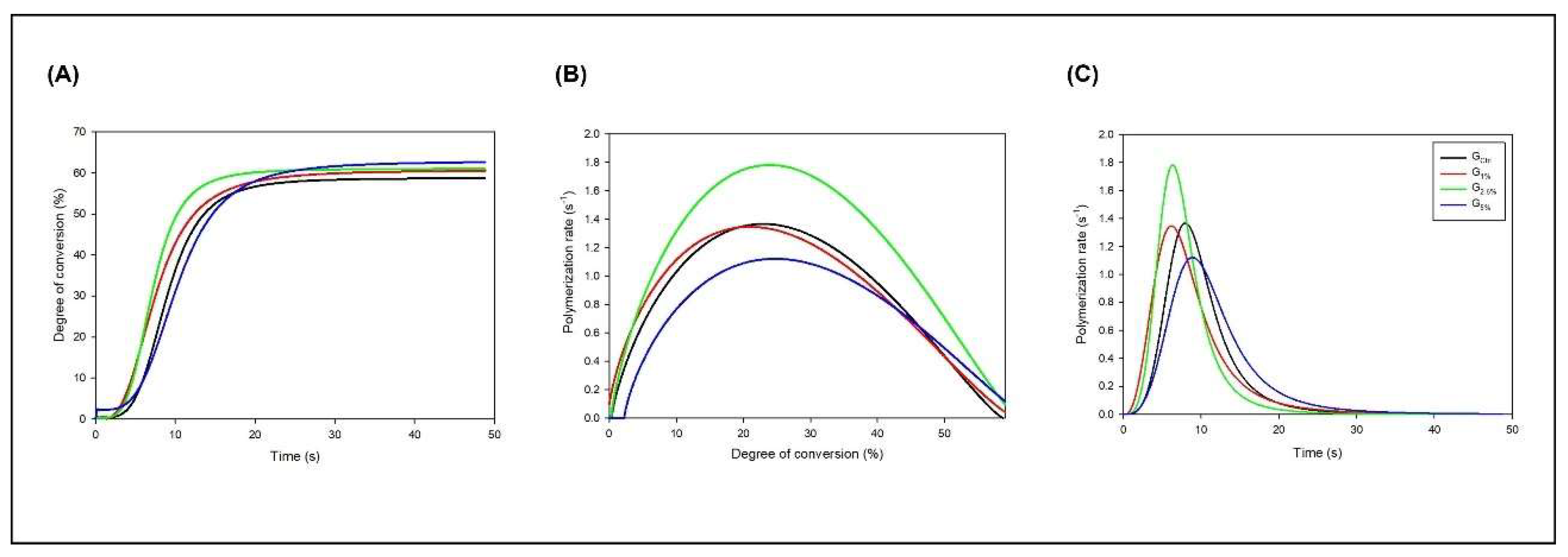

The results from the polymerization kinetics analysis are indicated in

Figure 1. Image A shows the results of DC

versus time, evidencing the differences in the conversion process among the experimental adhesives. The groups with the ionic liquid started converting carbon-carbon double bonds (C=C) into single carbon-carbon single bonds (C-C) before the G

CTRL. In

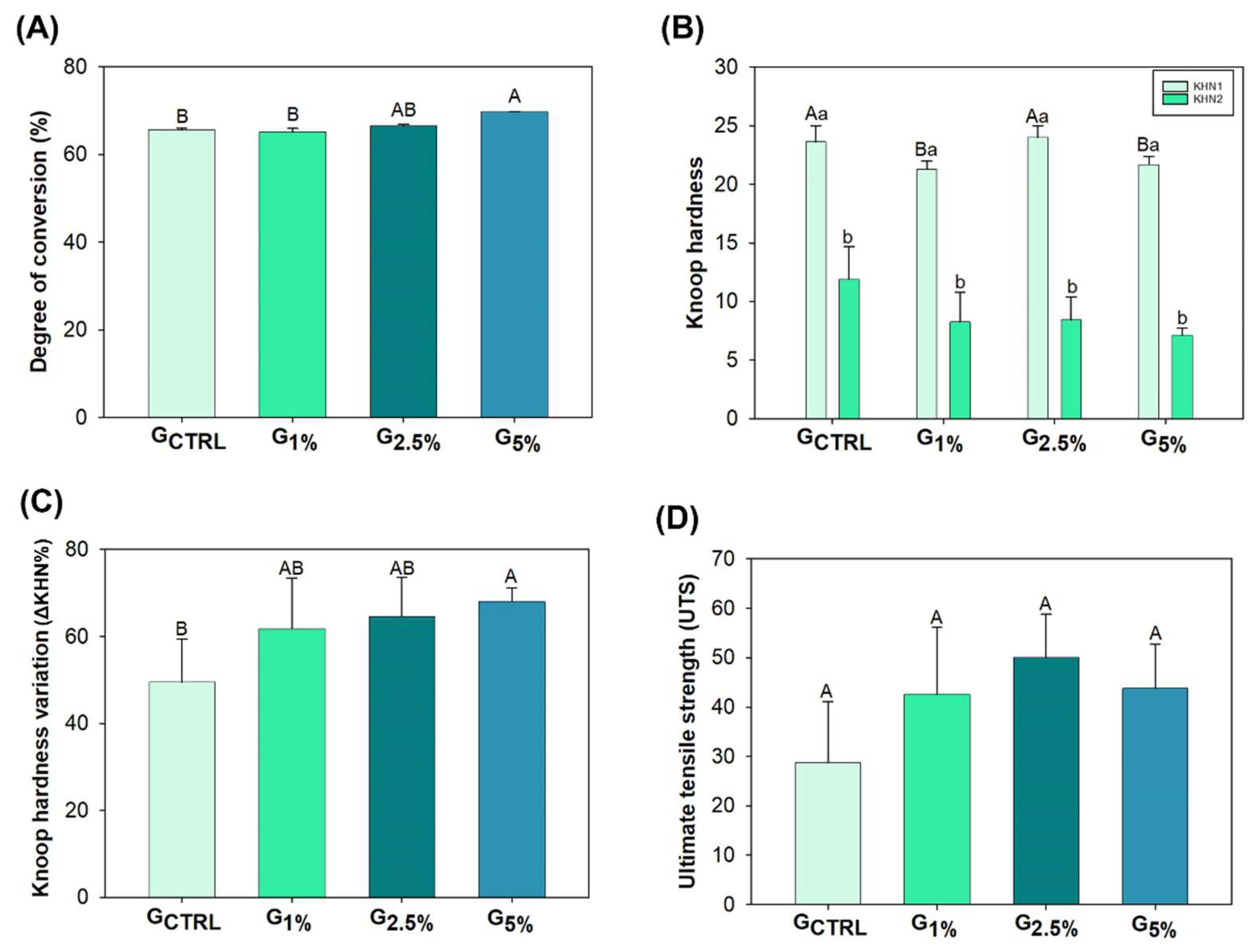

Figure 3, image A, it is possible to observe the mean and standard deviation values of DC for each group. The values ranged from 65.16 (± 0.83) % for G

1% to 69.75 (± 0.09) % for G

5% (

p < 0.05). There was no statistical difference from the G

CTRL to G

2.5% (

p > 0.05). However, the addition of 5 wt.% of ionic liquid increased the DC compared to G

CTRL and G

1% (

p < 0.05), without statistical difference for G

2.5% (

p > 0.05).

Still, in

Figure 2, image B, we observed that the ionic liquid groups reached higher maximum polymerization rates than G

CTRL. In addition, images B and C evidence that groups with the ionic liquid started the self-acceleration process before G

CTRL.

Figure 3 also shows the experimental adhesive resin’s initial and final Knoop hardness (image B) and Knoop hardness variation (ΔKHN%, image C). The groups showed different initial Knoop hardness (p < 0.05), but all of them decreased the hardness after immersion in the alcoholic solution (p < 0.05). The ΔKHN% ranged from 49.47 (± 9.94) % for GCTRL to 68.04 (± 3.08) % for G5% (p < 0.05). From GCTRL to G2.5%, there were no differences in the softening in solvent (p > 0.05), with higher softening in solvent values for G5% (p < 0.05). However, there were no statistical differences among the ionic liquid groups (p > 0.05).

Figure 3, image D, shows the mean and standard deviation values of ultimate tensile strength (UTS). The values ranged from 28.71 (± 12.37) MPa for G

CTRL to 49.99 (± 8.88) MPa for G

2.5%. There was no statistically significant difference among groups for this mechanical test (

p > 0.05).

4. Discussion

Incorporating antimicrobial agents into resins aims to reduce biofilm at the tooth-restorative material interface [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. BMI.NTf

2 was previously incorporated into an orthodontic resin and demonstrated an antibacterial effect against biofilms of

S. mutans and planktonic

S. mutans [

22]. However, the physicochemical properties were impaired by 10 wt.% of BMI.NTf

2 [

22]. This ionic liquid was added to an experimental adhesive resin in the present study, and its physicochemical properties were analyzed. There was no statistical difference in the DC among G

TRL, G

1%, and G

2.5%. The incorporation of 5 wt.% of BMI.NTf

2 increased the DC compared to G

CTRL and G

1% (p < 0.05), while the softening in solvent was higher with 5 wt.% addition.

Ionic liquids are exploited as solvents [

23], and their properties are responsible for increasing the stability of the drug formulation and strengthening the association between drugs and surfactants or polymers. Furthermore, they facilitate drug transport to the target site of action and increase the solubility of moderately water-soluble drugs [

18]. The chemical structure of BMI.NTf

2 gives it antimicrobial activity: the cationic structure is attracted by the negative charge at the bacterial wall and membrane compounds by electrostatic forces [

27]. Moreover, its alkyl chain and anion, NTf

2, present hydrophobicity, assisting in disorganizing the bacterial wall and membranes.

The increase in the concentration of BMI.NTf

2 demonstrated a higher DC. Ionic liquids are characterized by molecular properties such as charge distribution, dipole moment, polarizability, hydrogen acceptance/donation, and electron pair acceptance/donation. The carbon double bonds present in the monomers can interact with the presence of ionic liquids through hydrogen bonds or interaction of the electron pair of the double bond with the electronic cloud of ionic liquid [

13]. This interaction can increase the conversion of carbon double bonds for groups with a higher concentration of BMI.NTf

2. In addition to the DC being altered, the polymerization kinetics can change depending on the compound added by modifying the mobility of the polymer chains [

28].

The polymerization kinetics of the dental adhesive resins incorporating the ionic liquid BMI.NTf2 provided insightful data that helped elucidate the underlying mechanisms of the observed results. Notably, the polymerization reaction in the samples containing BMI.NTf2 demonstrated a marked acceleration when compared to the control group (GCTRL). This acceleration is a critical factor in enhancing the overall performance of the dental resin.

The increased polymerization rate for the BMI.NTf2 groups may be attributed to a reduction in the viscosity of the adhesive resin. As the concentration of BMI.NTf2 in the resin formulation increases, it appears to interact with the resin matrix to lower its viscosity. Lower viscosity in polymerizable dental resins is advantageous because it allows for greater mobility of the polymer chains during the curing process. This increased mobility facilitates more efficient cross-linking among the polymer chains, thereby enhancing the resin’s degree of conversion (DC).

A higher degree of conversion is directly associated with improved mechanical properties and durability of the resin. It ensures that more monomers are converted into polymer, thus creating a denser, more cross-linked network. This denser network is crucial for the resin’s structural integrity and resistance to wear and degradation in the challenging oral environment.

Furthermore, the reduction in viscosity and the resultant improved polymerization kinetics could also impact the handling properties of the adhesive, making it easier to apply and manipulate during dental procedures. This ease of application can lead to more precise and reliable placement of restorations, contributing to better clinical outcomes.The addition of BMI.NTf

2 possibly interfered with the mobility of the chains and the density of crosslinks, leading to plasticizing effects [

29,

30]. Polymers with lower crosslink density are prone to soften more when in contact with alcoholic solutions [

31]. Similar results were observed in a previous study with orthodontic adhesive resins with the addition of BMI.NTf

2 [

22]. This effect was also investigated by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), and the higher the ionic liquid concentration, the higher the formation of novel derivative (DTG) of the TGA curve. This result was attributed to forming regions with different crosslink densities, with areas more linear than others, when the ionic liquid was incorporated in greater quantities [

22].

The immersion of dental adhesive resins in solvent is a critical test to assess their durability and resistance to the oral environment, particularly to the effects of moisture. In the study under consideration, all experimental groups exhibited a reduction in hardness upon solvent immersion. Notably, the group with 5% BMI.NTf2 (G5%) demonstrated a more significant decrease in hardness compared to the control group (GCTRL). This finding contrasts with previous research conducted on an orthodontic resin formulation, which showed different behavior under similar conditions.

The divergent results between the two studies can largely be attributed to the differences in the base resin compositions used in each. The orthodontic resin did not contain hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA), a commonly used monomer in dental adhesives that is known for its hydrophilic properties. Instead, the orthodontic resin included triethylene glycol dimethacrylate (TEGDMA), which is less hydrophilic than HEMA. This reduced hydrophilicity likely contributed to the orthodontic resin’s enhanced resistance to softening when exposed to solvents.

Additionally, the orthodontic resin incorporated silanized colloidal silica, a filler known to improve the physicochemical properties of polymers [

22]. The presence of this filler helps to increase the mechanical strength and stability of the resin, making it less susceptible to softening and degradation upon solvent immersion. This enhancement is particularly important in orthodontic applications where the material must withstand prolonged exposure to a moist and mechanically challenging environment.

In contrast, the current study involving BMI.NTf2 in dental adhesives explored concentrations of 1% and 2.5% (G1% and G2.5%), which did not significantly influence the softening behavior in the solvent. This suggests that the crosslinking density within these groups, including the control (GCTRL), is likely similar. The addition of BMI.NTf2 at these concentrations does not appear to alter the network structure of the resin significantly enough to affect its solvent resistance.

The comparison of these two distinct resin formulations highlights the importance of base resin composition and the selection of appropriate additives and fillers in achieving desired material properties. The difference in behavior underscores the need for tailored resin formulations depending on the specific requirements of the dental application, be it orthodontic or adhesive applications. For future formulations, understanding the interaction between the resin matrix, fillers, and any ionic liquids like BMI.NTf2 will be crucial in developing materials that combine optimal mechanical properties with resistance to environmental challenges.

Furthermore, an assessment of the cohesive strength of the polymers was conducted in addition to the evaluation of softening in solvent. In congruence with a prior study [

22], no significant statistical disparities were observed among the various groups. Despite the adverse impact of incorporating 5 wt.% BMI.NTf2 on the adhesive’s softening behavior, this concentration exhibited no discernible alteration in the adhesive’s ultimate tensile strength (UTS). Nonetheless, given the outcomes of the softening in solvent tests and the understanding of the potential effects of high concentrations of ionic liquids on polymer structure formation, the utilization of 2.5 wt.% BMI.NTf

2 emerged as the most suitable choice for the experimental adhesive resin.

5. Conclusions

A comprehensive study examined the influence of varying percentages of the ionic liquid, BMI.NTf2, in novel dental adhesive formulations, has been investigated. Considering clinically pertinent attributes for dental adhesives, the formulation featuring 2.5 wt.% BMI.NTf2 loading has been identified as the optimal composition. The physical and chemical properties of dental adhesives were analyzed when BMI.NTf2 was added from 1 to 5 wt.%. It was concluded that BMI.NTf2 at 2.5 wt.% increases adhesives’ degree of conversion without changing other properties. Consequently, this approach holds significant promise in developing a strong bonding interface tooth-composite to promote bacterial inhibition and curtailing secondary caries development around bonded restorations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.M.G., J.D.S., F.M.C.; Formal analysis; I.M.G., A.S., V.S.S.; Project administration, J.D.S., F.M.C.; Resources, J.D.S., F.M.C.; Validation, J.D.S., F.M.C.; Visualization, I.M.G., M.A.S.M. Writing - original draft, I.M.G., A.S., V.S.S.; Writing - review & editing, M.A.S.M., J.D.S., F.M.C.

Funding

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES) - Finance Code 001 (scholarship of A.S.) and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico – Brasil (CNPq) – n° 307939/2019-7, 308818/2018-0 and 309111/2021-8.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019). Seattle: Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) 2020. Available from http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool.

- Meerbeek, B.V.; Yoshihara, K.; Yoshihara, Y.; Mine, A; De Munck, J. ; Van Landuyt, K.L. State of the art of self-etch adhesives. Dent Mater 2011, 1, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferracane, J.L. Resin composite-state of the art. Dent Mater 2011, 27, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, I.; Rothmaier, K.; Pitchika, V.; Crispin, A.; Hickel, R.; Garcia-Godoy, F. Risk factors for secondary caries in direct composite restorations in primary teeth. Int J Paediatr Dent 2015, 25, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraschini, V.; Fai, C.K.; Alto, R.M.; dos Santos, GO. Amalgam and resin composite longevity of posterior restorations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent 2015, 43, 1043–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collares, F.M.; Leitune, V.C.B.; Franken, P.; Parollo, C.F.; Ogliari, F.A.; Samuel, S.M.W. Influence of addition of [2-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl]trimethylammonium chloride to an experimental adhesive. Braz Oral Res 2017, 31, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiroky, P.R.; Leitune, V.C.B.; Garcia, I.M.; Ogliari, F.A.; Samuel, S.M.W.; Collares, F.M. Triazine Compound as Copolymerized Antibacterial Agent in Adhesive Resins. Braz Dent J 2017, 28, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, D.A.; Rodrigues, N.S.; Souza, L.C.; Lomonaco, D. Physicochemical and Microbiological Assessment of an Experimental Composite Doped with Triclosan-Loaded Halloysite Nanotubes. Materials 2018, 11, 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, I.M.; Leitune, V.C.B.; Visioli, F.; Samuel, S.M.W.; Collares, FM. Influence of zinc oxide quantum dots in the antibacterial activity and cytotoxicity of an experimental adhesive resin. J Dent 2018, 73, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li Y, Hu X, Ruan J, Arola DD, Ji C, Weir MD, Oates TW, Chang X, Zhang K, Xu HHK. Bonding durability, antibacterial activity and biofilm pH of novel adhesive containing antibacterial monomer and nanoparticles of amorphous calcium phosphate. J Dent 2019, 81, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, I.M.; Rodrigues, S.B.; Leitune, V.C.B.; Collares, F.M. Antibacterial, chemical and physical properties of sealants with polyhexamethylene guanidine hydrochloride. Braz Oral Res 2019, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, A.H.S.; Garcia, I.M.; Motta, A.S.D.; Leitune, V.C.B.; Collares, F.M. Triclosan-loaded chitosan as antibacterial agent for adhesive resin. J Dent 2019, 83, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luczak, J.; Paszkiewicz, M.; Krukowska, A.; Malankowska, A.; Zaleska-Medynska, A. Ionic liquids for nano- and microstructures preparation. Part 1: Properties and multifunctional role. Adv Colloid Interface Sci 2016, 230, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kagimoto, J.; Fukumoto, K.; Ohno, H. Effect of tetrabutylphosphonium cation on the physico-chemical properties of amino-acid ionic liquids. ChemComm 2006, 21, 2254–2256. [Google Scholar]

- Weingartner, H. Understanding Ionic Liquids at the Molecular Level: Facts, Problems, and Controversies. Angew Chemie Int Ed 2008, 47, 654–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pendleton JN, Gilmore BF. The antimicrobial potential of ionic liquids: A source of chemical diversity for infection and biofilm control. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2015;46:131-139.

- Ferraz, R.; Branco, L.C.; Prudencio, C.; Noronha, J.P.; Petrovski, Z. Ionic liquids as active pharmaceutical ingredients. ChemMedChem. 2011, 6, 975–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gindri, I.M.; Siddiqui, D.A.; Frizzo, C.P.; Martins, M.A.; Rodrigues, D.C. Ionic Liquid Coatings for Titanium Surfaces: Effect of IL Structure on Coating Profile. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2015, 7, 27421–27431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, H.; Izutani, N. , Kitagawa, R.; Maezono, H.; Yamaguchi, M.; Imazato, S. Evolution of resistance to cationic biocides in Streptococcus mutans and Enterococcus faecalis. J Dent 2016, 47, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, I.M.; Souza, V.S.; Hellriegel, C.; Scholten, J.D.; Collares, F.M. Ionic liquid-stabilized titania quantum dots applied in adhesive resin. J Dent Res 2019, 98, 682–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, I.M.; Ferreira, C.J.; Souza, V.S.; Leitune, V.C.B.; Samuel, S.M.W.; Balbinot, G.S.; Motta, A.S.; Visioli, F.; Scholten, J.D.; Collares, F.M. Ionic liquid as antibacterial agent for an experimental orthodontic adhesive. Dent Mater 2019, 35, 1155–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degrazia, F.W.; Leitune, V.C.; Takimi, A.S.; Collares, F.M.; Sauro, S. Physicochemical and bioactive properties of innovative resin-based materials containing functional halloysite-nanotubes fillers. Dent Mater 2016;32:133-1143.

- Collares, F.M.; Portella, F.F.; Leitune, V.C.; Samuel, S.M.W. Discrepancies in degree of conversion measurements by FTIR. Braz Oral Res 2014;28:1-7.

- Collares, F.M.; Ogliari, F.A.; Zanchi, C.H.; Petzhold, C.L.; Piva, E.; Samuel, S.M.W. Influence of 2-Hydroxyethyl Methacrylate Concentration on Polymer Network of Adhesive Resin. J Adhes Dent 2011;13:125-129.

- Garcia, I.M.; Rodrigues, S.B.; de Souza Balbinot, G.; Visioli, F.; Leitune, V.C.B.; Collares, F.M. Quaternary ammonium compound as antimicrobial agent in resin-based sealants. Clin Oral Investig.

- Garcia, I.M. , Souza, V.S., Scholten, J.D., Collares, F.M. Quantum Dots of Tantalum Oxide with an Imidazolium Ionic Liquid as Antibacterial Agent for Adhesive Resin. J Adhes Dent.

- Yeaman, M.R.; Yount, N.Y. Mechanisms of antimicrobial peptide action and resistance. Pharmacol Rev 2003, 55, 27–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barszczewska-Rybarek, I.M. Characterization of urethane-dimethacrylate derivatives as alternative monomers for the restorative composite matrix. Dent Mater 2014, 30, 1336–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, L.F.; Moraes, R.R.; Cavalcante, L.M.; Sinhoreti, M.A.C.; Correr-Sobrinho, L.; Consani, S. Cross-link density evaluation through softening tests: Effect of ethanol concentration. Dent Mater 2008, 24, 99–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferracane, J.L. Hygroscopic and hydrolytic effects in dental polymer networks. Dent Mater 2006, 22, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filho, J.D.; Poskus, L.T.; Guimaraes, J.G.; Barcellos, A.A.; Silva, E.M. Degree of conversion and plasticization of dimethacrylate-based polymeric matrices: influence of light-curing mode. J Oral Sci 2008, 50, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).