Submitted:

13 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Screening and Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Assessment (Risk of Bias)

2.5. Data Synthesis

2.6. Analysis of Subgroups or Subsets

2.7. Changes on the Protocol

3. Results

3.1. Search Results and Characteristics of Included Studies

3.2. Study Design

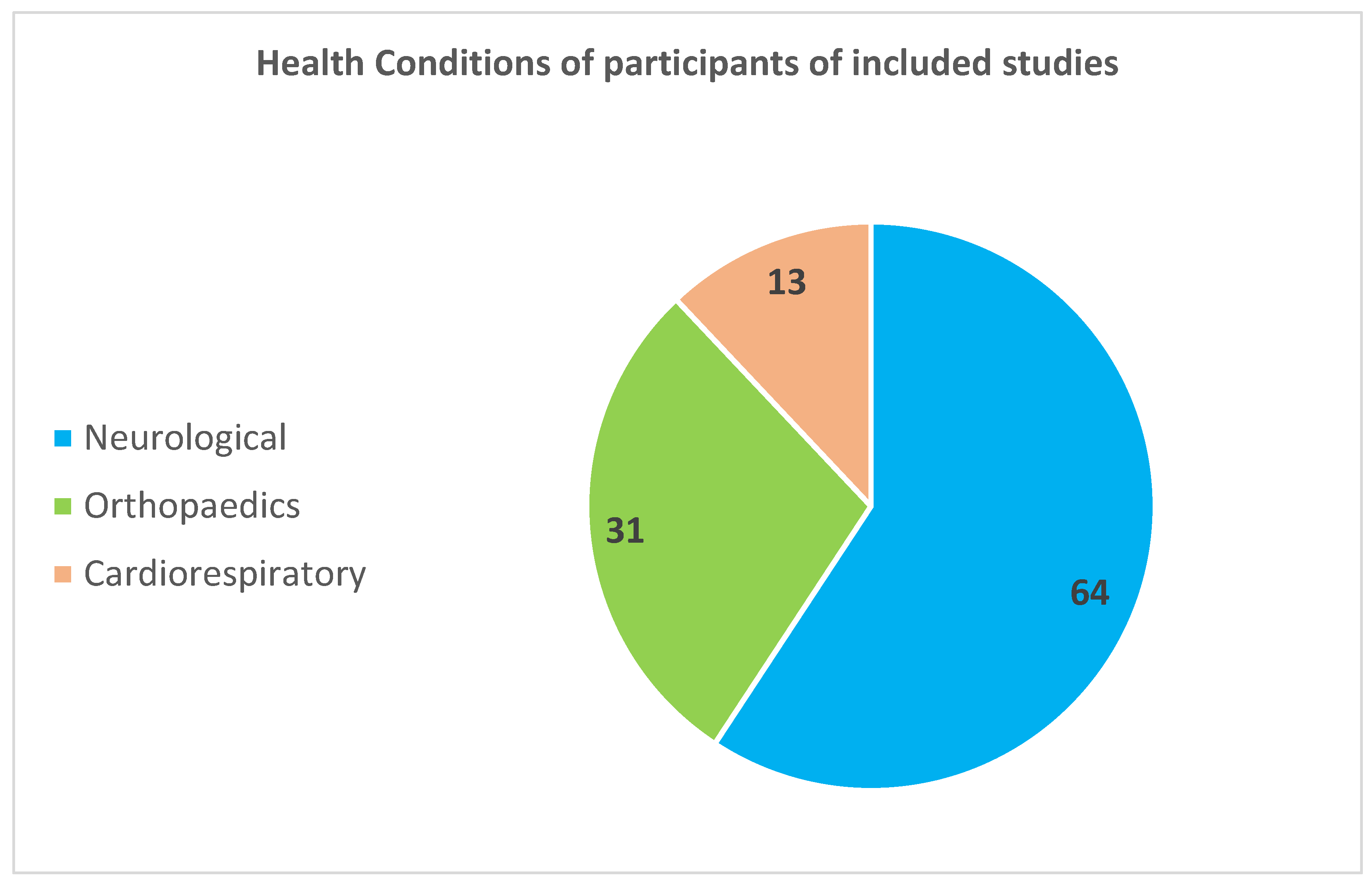

3.3. Participants’ Conditions

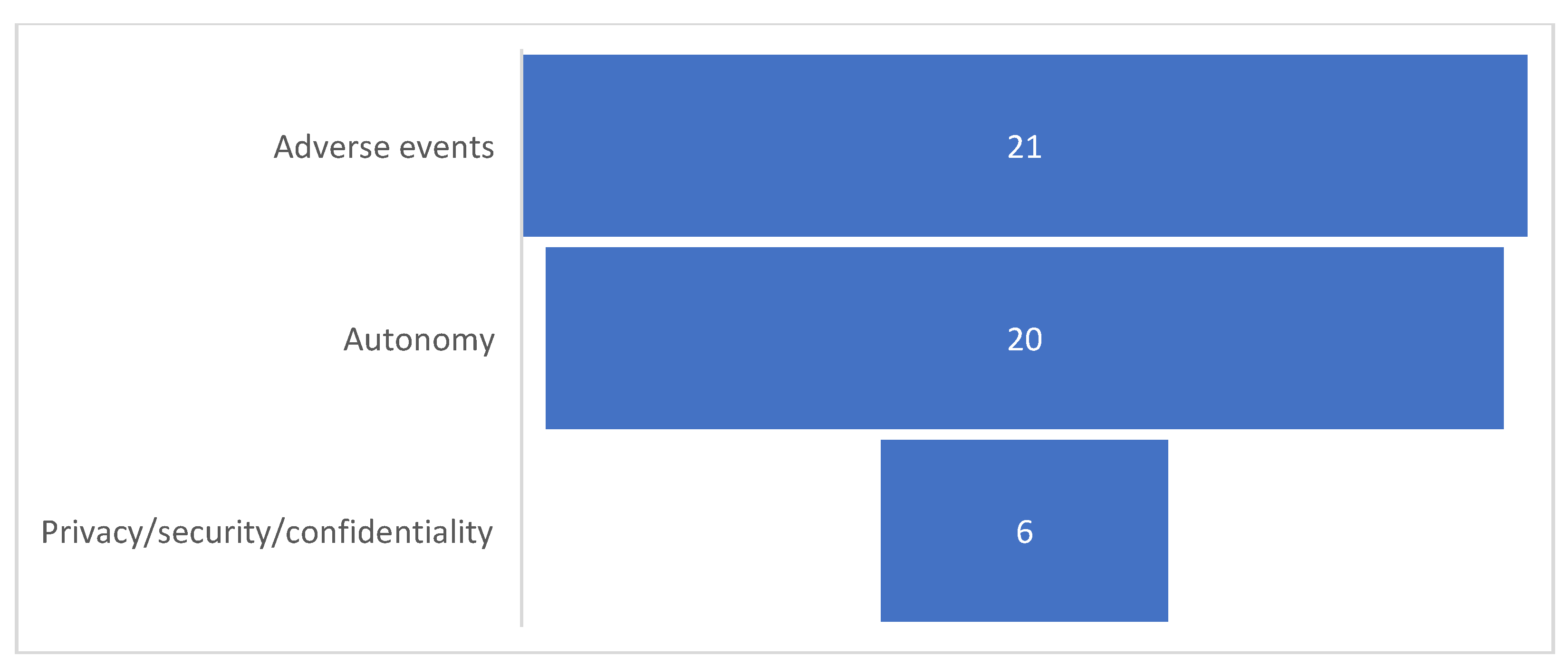

3.4. Ethics Considerations

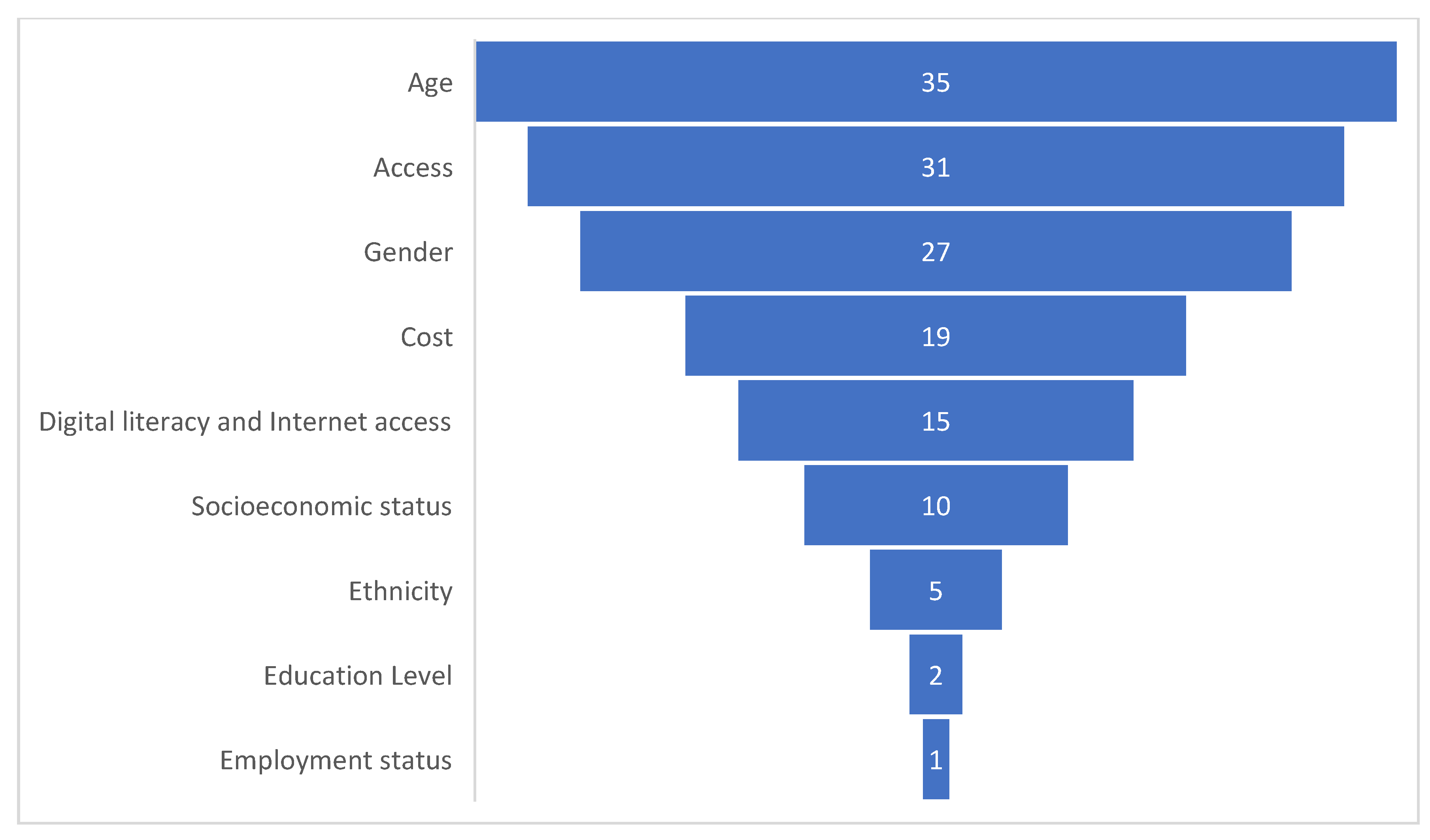

3.5. Equity Considerations

3.6. Quality Assessment (Risk of Bias)

4. Discussion

4.1. Ethics Aspects

4.2. Equity Aspects

4.3. Limitation

5. Conclusions

References

- Xu, J.; Willging, A.; Bramstedt, K.A. A scoping review of the ethical issues within telemedicine: Lessons from COVID-19 pandemic. J. Health Soc. Sci. 2021, 6, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kazuko Shem, I.I.; Alexander, M. Chapter 2. Getting Started: Mechanisms of Telerehabilitation. In Telerehabilitation; Alexander, M., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2022; pp. 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seron, P.; Oliveros, M.J.; Gutierrez-Arias, R.; Fuentes-Aspe, R.; Torres-Castro, R.C.; Merino-Osorio, C.; Nahuelhual, P.; Inostroza, J.; Jalil, Y.; Solano, R.; et al. Effectiveness of Telerehabilitation in Physical Therapy: A Rapid Overview. Phys Ther 2021, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federico, S.; Cacciante, L.; De Icco, R.; Gatti, R.; Jonsdottir, J.; Pagliari, C.; Franceschini, M.; Goffredo, M.; Cioeta, M.; Calabrò, R.S.; et al. Telerehabilitation for Stroke: A Personalized Multi-Domain Approach in a Pilot Study. J Pers Med 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroni, M.P.; Jacob, M.F.A.; Rios, W.R.; Fandim, J.V.; Fernandes, L.G.; Chaves, P.I.; Fioratti, I.; Saragiotto, B.T. The state of the art in telerehabilitation for musculoskeletal conditions. Arch Physiother 2023, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kairy, D.; Lehoux, P.; Vincent, C.; Visintin, M. A systematic review of clinical outcomes, clinical process, healthcare utilization and costs associated with telerehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil 2009, 31, 427–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nittari, G.; Khuman, R.; Baldoni, S.; Pallotta, G.; Battineni, G.; Sirignano, A.; Amenta, F.; Ricci, G. Telemedicine Practice: Review of the Current Ethical and Legal Challenges. Telemed J E Health 2020, 26, 1427–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, E.; Meade, M.A. Disparities in access to health care among adults with physical disabilities: Analysis of a representative national sample for a ten-year period. Disabil Health J 2015, 8, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, V.J.; Stevens, A.; Nussbaumer-Streit, B.; Kamel, C.; Garritty, C. Paper 2: Performing rapid reviews. [CrossRef]

- Garritty, C.; Gartlehner, G.; Nussbaumer-Streit, B.; King, V.J.; Hamel, C.; Kamel, C.; Affengruber, L.; Stevens, A. Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group offers evidence-informed guidance to conduct rapid reviews. J Clin Epidemiol 2021, 130, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veras, M.; Sigouin, J.; Auger, C.; Auger, L.-P.; Ahmed, S.; Boychuck, Z.; Cavallo, S.; Lévesque, M.; Lovo, S.; Miller, W.C.; et al. A rapid review protocol of physiotherapy and occupational therapy telerehabilitation to inform ethical and equity concerns. DIGITAL HEALTH 2024, 10, 20552076241260367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matchar, D.B. Chapter 1: Introduction to the Methods Guide for Medical Test Reviews. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2012, 27, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covidence systematic reviews software. Veritas Health Innovations: Melbourne, Australia. Available at: www.covidence.org.

- Veras, M.; Labbé, D.R.; Furlano, J.; Zakus, D.; Rutherford, D.; Pendergast, B.; Kairy, D. A framework for equitable virtual rehabilitation in the metaverse era: Challenges and opportunities. Front Rehabil Sci 2023, 4, 1241020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Neill, J.; Tabish, H.; Welch, V.; Petticrew, M.; Pottie, K.; Clarke, M.; Evans, T.; Pardo Pardo, J.; Waters, E.; White, H.; et al. Applying an equity lens to interventions: Using PROGRESS ensures consideration of socially stratifying factors to illuminate inequities in health. J Clin Epidemiol 2014, 67, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mays, N.; Pope, C.; Popay, J. Systematically reviewing qualitative and quantitative evidence to inform management and policy-making in the health field. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005, 10 (Suppl. S1), 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, C.; Yamabayashi, C.; Syed, N.; Kirkham, A.; Camp, P.G. Exercise Telemonitoring and Telerehabilitation Compared with Traditional Cardiac and Pulmonary Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Physiother Can 2016, 68, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirra, M.; Marsili, L.; Wattley, L.; Sokol, L.L.; Keeling, E.; Maule, S.; Sobrero, G.; Artusi, C.A.; Romagnolo, A.; Zibetti, M.; et al. Telemedicine in Neurological Disorders: Opportunities and Challenges. Telemed J E Health 2019, 25, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninnis, K.; Van Den Berg, M.; Lannin, N.A.; George, S.; Laver, K. Information and communication technology use within occupational therapy home assessments: A scoping review. British Journal of Occupational Therapy 2018, 82, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, M.; Moja, L.; Banzi, R.; Pistotti, V.; Tonin, P.; Venneri, A.; Turolla, A. Telerehabilitation and recovery of motor function: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 2015, 21, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amatya, B.; Galea, M.P.; Kesselring, J.; Khan, F. Effectiveness of telerehabilitation interventions in persons with multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2015, 4, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amatya, B.; Khan, F.; Galea, M. Rehabilitation for people with multiple sclerosis: An overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019, 1, Cd012732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Jin, W.; Zhang, X.-X.; Xu, W.; Liu, X.-N.; Ren, C.-C. Telerehabilitation Approaches for Stroke Patients: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases 2015, 24, 2660–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Abel, K.T.; Janecek, J.T.; Zheng, K.; Cramer, S.C. Home-based technologies for stroke rehabilitation: A systematic review. Int J Med Inform 2019, 123, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dávila Castrodad, I.M.; Recai, T.M.; Abraham, M.M.; Etcheson, J.I.; Mohamed, N.S.; Edalatpour, A.; Delanois, R.E. Rehabilitation protocols following total knee arthroplasty: A review of study designs and outcome measures. Annals of translational medicine 2019, 7 (Suppl. S7), S255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Amatya, B.; Kesselring, J.; Galea, M. Telerehabilitation for persons with multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015, 2015, CD010508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laver, K.E.; Adey-Wakeling, Z.; Crotty, M.; Lannin, N.A.; George, S.; Sherrington, C. Telerehabilitation services for stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020, 1, Cd010255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almojaibel, A.A. Delivering Pulmonary Rehabilitation for Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease at Home Using Telehealth: A Review of the Literature. Saudi J Med Med Sci 2016, 4, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appleby, E.; Gill, S.T.; Hayes, L.K.; Walker, T.L.; Walsh, M.; Kumar, S. Effectiveness of telerehabilitation in the management of adults with stroke: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berton, A.; Longo, U.G.; Candela, V.; Fioravanti, S.; Giannone, L.; Arcangeli, V.; Alciati, V.; Berton, C.; Facchinetti, G.; Marchetti, A.; et al. Virtual Reality, Augmented Reality, Gamification, and Telerehabilitation: Psychological Impact on Orthopedic Patients' Rehabilitation. J Clin Med 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blood, k. The use of Telehealth by Physical Therapis: A review of literature. Gerinotes: Academy of Geriatrics Physical Therapy 2019, 26, 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Flodgren, G.; Rachas, A.; Farmer, A.J.; Inzitari, M.; Shepperd, S. Interactive telemedicine: Effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015, 2015, CD002098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, K.; Khonsari, S.; Gallagher, R.; Gallagher, P.; Clark, A.M.; Freedman, B.; Briffa, T.; Bauman, A.; Redfern, J.; Neubeck, L. Telehealth interventions for the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing 2019, 18, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slattery, B.W.; Haugh, S.; O'Connor, L.; Francis, K.; Dwyer, C.P.; O'Higgins, S.; Egan, J.; McGuire, B.E. An Evaluation of the Effectiveness of the Modalities Used to Deliver Electronic Health Interventions for Chronic Pain: Systematic Review With Network Meta-Analysis. J Med Internet Res 2019, 21, e11086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Meij, E.; Anema, J.R.; Otten, R.H.; Huirne, J.A.; Schaafsma, F.G. The Effect of Perioperative E-Health Interventions on the Postoperative Course: A Systematic Review of Randomised and Non-Randomised Controlled Trials. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0158612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Egmond, M.A.; van der Schaaf, M.; Vredeveld, T.; Vollenbroek-Hutten, M.M.R.; van Berge Henegouwen, M.I.; Klinkenbijl, J.H.G.; Engelbert, R.H.H. Effectiveness of physiotherapy with telerehabilitation in surgical patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiotherapy 2018, 104, 277–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veras, M.; Kairy, D.; Rogante, M.; Giacomozzi, C.; Saraiva, S. Scoping review of outcome measures used in telerehabilitation and virtual reality for post-stroke rehabilitation. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 2016, 23, 567–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Parmanto, B. Reaching People With Disabilities in Underserved Areas Through Digital Interventions: Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res 2019, 21, e12981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batsis, J.A.; DiMilia, P.R.; Seo, L.M.; Fortuna, K.L.; Kennedy, M.A.; Blunt, H.B.; Bagley, P.J.; Brooks, J.; Brooks, E.; Kim, S.Y.; et al. Effectiveness of Ambulatory Telemedicine Care in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019, 67, 1737–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrell, M.A.; Galea, O.A.; O'Leary, S.P.; Hill, A.J.; Russell, T.G. Real-time telerehabilitation for the treatment of musculoskeletal conditions is effective and comparable to standard practice: A systematic review and meta-analysis. In Clin Rehabil, England, 2017; Vol. 31, pp. 625–638. [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Liu, W.; Cai, S.; Hu, Y.; Dong, J. The efficacy of e-health in the self-management of chronic low back pain: A meta analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies 2020, 106, 103507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, S.; Sharma, S.; Omar, B.; Paungmali, A.; Joseph, L. Validity and reliability of Internet-based physiotherapy assessment for musculoskeletal disorders: A systematic review. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 2016, 23, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, A.W.; Jaggi, A.; May, C.R. What is the patient acceptability of real time 1:1 videoconferencing in an orthopaedics setting? A systematic review. In Physiotherapy, © 2017 Chartered Society of Physiotherapy: England, 2018; Vol. 104, pp. 178–186. [CrossRef]

- Tchero, H.; Tabue Teguo, M.; Lannuzel, A.; Rusch, E. Telerehabilitation for Stroke Survivors: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Med Internet Res 2018, 20, e10867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomè, A.; Sasso D'Elia, T.; Franchini, G.; Santilli, V.; Paolucci, T. Occupational Therapy in Fatigue Management in Multiple Sclerosis: An Umbrella Review. Mult Scler Int 2019, 2019, 2027947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacono, T.; Stagg, K.; Pearce, N.; Hulme Chambers, A. A scoping review of Australian allied health research in ehealth. BMC Health Serv Res 2016, 16, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrzak, E.; Cotea, C.; Pullman, S.; Nasveld, P. Self-management and rehabilitation in osteoarthritis: Is there a place for internet-based interventions? Telemed J E Health 2013, 19, 800–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rintala, A.; Hakala, S.; Paltamaa, J.; Heinonen, A.; Karvanen, J.; Sjögren, T. Effectiveness of technology-based distance physical rehabilitation interventions on physical activity and walking in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Disabil Rehabil 2018, 40, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, L.; Haldar, A.; Jasper, U.; Taylor, A.; Visvanathan, R.; Chehade, M.; Gill, T. Utilising Digital Health Technology to Support Patient-Healthcare Provider Communication in Fragility Fracture Recovery: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-Y.; Guan, B.-S.; Li, Z.-K.; Yang, Q.-H.; Xu, T.-J.; Li, H.-B.; Wu, Q.-Y. Application of telehealth intervention in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 2018, 26, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gövercin, M.; Missala, I.M.; Marschollek, M.; Steinhagen-Thiessen, E. Virtual rehabilitation and telerehabilitation for the upper limb: A geriatric review. GeroPsych: The Journal of Gerontopsychology and Geriatric Psychiatry 2010, 23, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grona, S.L.; Bath, B.; Busch, A.; Rotter, T.; Trask, C.; Harrison, E. Use of videoconferencing for physical therapy in people with musculoskeletal conditions: A systematic review. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 2017, 24, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, S.; Sephton, R.; Yeowell, G. The Effectiveness of Digital Health Interventions in the Management of Musculoskeletal Conditions: Systematic Literature Review. J Med Internet Res 2020, 22, e15617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastora-Bernal, J.M.; Martín-Valero, R.; Barón-López, F.J.; Estebanez-Pérez, M.J. Evidence of Benefit of Telerehabitation After Orthopedic Surgery: A Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res 2017, 19, e142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, J.; van Criekinge, T.; Embrechts, E.; Celis, X.; Van Schuppen, J.; Truijen, S.; Saeys, W. Combining the benefits of tele-rehabilitation and virtual reality-based balance training: A systematic review on feasibility and effectiveness. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol 2019, 14, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, H.; Nair, S.R.; Thakker, D. Role of telerehabilitation in patients following total knee arthroplasty: Evidence from a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 2016, 23, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simek, E.M.; McPhate, L.; Haines, T.P. Adherence to and efficacy of home exercise programs to prevent falls: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of exercise program characteristics. Prev Med 2012, 55, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speyer, R.; Denman, D.; Wilkes-Gillan, S.; Chen, Y.W.; Bogaardt, H.; Kim, J.H.; Heckathorn, D.E.; Cordier, R. Effects of telehealth by allied health professionals and nurses in rural and remote areas: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Rehabil Med 2018, 50, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srikesavan, C.; Bryer, C.; Ali, U.; Williamson, E. Web-based rehabilitation interventions for people with rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 2018, 25, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velayati, F.; Ayatollahi, H.; Hemmat, M. A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Telerehabilitation Interventions for Therapeutic Purposes in the Elderly. Methods Inf Med 2020, 59, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wake, E.; Atkins, H.; Willock, A.; Hawkes, A.; Dawber, J.; Weir, K.A. Telehealth in trauma: A scoping review. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 2020, 28, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Hunter, D.J.; Vesentini, G.; Pozzobon, D.; Ferreira, M.L. Technology-assisted rehabilitation following total knee or hip replacement for people with osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 2019, 20, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung Kn, G.; Fong, K.N. Effects of telerehabilitation in occupational therapy practice: A systematic review. Hong Kong J Occup Ther 2019, 32, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeroushalmi, S.; Maloni, H.; Costello, K.; Wallin, M.T. Telemedicine and multiple sclerosis: A comprehensive literature review. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 2019, 26, 400–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.M. Osteoarthritis year 2011 in review: Rehabilitation and outcomes. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2012, 20, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Johansson and C. Wild, "Telerehabilitation in stroke care--a systematic review," (in eng), no. 1758-1109 (Electronic). [CrossRef]

- Knepley, K.D.; Mao, J.Z.; Wieczorek, P.; Okoye, F.O.; Jain, A.P.; Harel, N.Y. Impact of Telerehabilitation for Stroke-Related Deficits. Telemedicine and e-Health 2020, 27, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guay, C.; Auger, C.; Demers, L.; Mortenson, W.B.; Miller, W.C.; Gélinas-Bronsard, D.; Ahmed, S. Components and Outcomes of Internet-Based Interventions for Caregivers of Older Adults: Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res 2017, 19, e313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarfo, F.S.; Ulasavets, U.; Opare-Sem, O.K.; Ovbiagele, B. Tele-Rehabilitation after Stroke: An Updated Systematic Review of the Literature. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2018, 27, 2306–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kebapci, A.; Ozkaynak, M.; Lareau, S.C. Effects of eHealth-Based Interventions on Adherence to Components of Cardiac Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing 2020, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuara, A.; Fabbri-Destro, M.; Scalona, E.; Lenzi, S.E.; Rizzolatti, G.; Avanzini, P. Telerehabilitation in response to constrained physical distance: An opportunity to rethink neurorehabilitative routines. J Neurol 2022, 269, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaney, A.M.; Flaherty, S. Self-care as care left undone? The ethics of the self-care agenda in contemporary healthcare policy. Nursing Philosophy 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, D.; Sun, A.; Wang, F.; Lu, J.; Guo, Y.; Ding, W. The efficacy and safety of telerehabilitation for patients following total knee arthroplasty: A overviews of systematic reviews. Biomed Eng Online 2023, 22, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, M.; Blary, A.; Ladner, J.; Gilliaux, M. Ethical Issues Linked to the Development of Telerehabilitation: A Qualitative Study. Int J Telerehabil 2021, 13, e6367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ÖZden, F.; Lembarkİ, Y. The Ethical Necessities and Principles in Telerehabilitation. Sağlık Hizmetleri ve Eğitimi Dergisi 2020, 3, 35–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.C.; Deutsch, J.E.; Holdsworth, L.; Kaplan, S.L.; Kosakowski, H.; Latz, R.; McNeary, L.L.; O'Neil, J.; Ronzio, O.; Sanders, K.; et al. Telerehabilitation in Physical Therapist Practice: A Clinical Practice Guideline from the American Physical Therapy Association. Phys Ther 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochette, A.; Korner-Bitensky, N.; Bishop, D.; Teasell, R.; White, C.L.; Bravo, G.; Côté, R.; Green, T.; Lebrun, L.H.; Lanthier, S.; et al. The YOU CALL-WE CALL randomized clinical trial: Impact of a multimodal support intervention after a mild stroke. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2013, 6, 674–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouédraogo, F.; Auger, L.P.; Moreau, E.; Côté, O.; Guerrera, R.; Rochette, A.; Kairy, D. Acceptability of Telerehabilitation: Experiences and Perceptions by Individuals with Stroke and Caregivers in an Early Supported Discharge Program. Healthcare 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, S.; Amit, S.; Kafy, A.A. Gender disparity in telehealth usage in Bangladesh during COVID-19. SSM Ment Health 2022, 2, 100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ott, J.; Champagne, S.N.; Bachani, A.M.; Morgan, R. Scoping 'sex' and 'gender' in rehabilitation: (mis)representations and effects. Int J Equity Health 2022, 21, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duruflé, A.; Le Meur, C.; Piette, P.; Fraudet, B.; Leblong, E.; Gallien, P. Cost effectiveness of a telerehabilitation intervention vs home based care for adults with severe neurologic disability: A randomized clinical trial. Digit Health 2023, 9, 20552076231191001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veras, M.; Stewart, J.; Deonandan, R.; Tatmatsu-Rocha, J.C.; Higgins, J.; Poissant, L.; Kairy, D. Cost-Analysis of a Home-Based Virtual Reality Rehabilitation to improve Upper Limb Function in Stroke Survivors. Global Journal of Health Sciences. Canadian Cener of Science and Education. 2020, 12, 1–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, C.K.; Scanlon, E. The Digital Divide Is a Human Rights Issue: Advancing Social Inclusion Through Social Work Advocacy. J Hum Rights Soc Work 2021, 6, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, S.A.; Masters, R.M. Disparities in Health Care and the Digital Divide. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2021, 23, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).