Submitted:

14 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Area of Study and selection of sampling sites

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. Macroinvertebrate Sampling

2.2.2. Assessment of Water Quality with the BMWP-CR Index

2.2.3. Physicochemical Analysis

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Macroinvertebrate Biodiversity

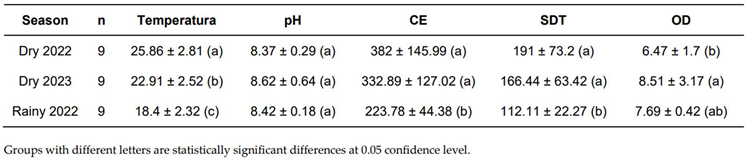

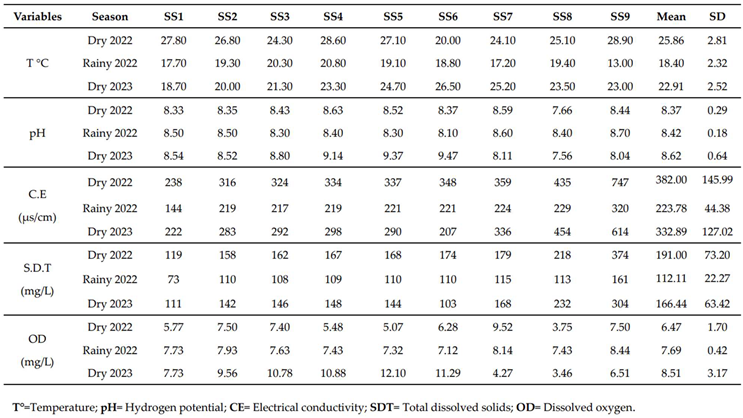

3.2. Physicochemical Analysis

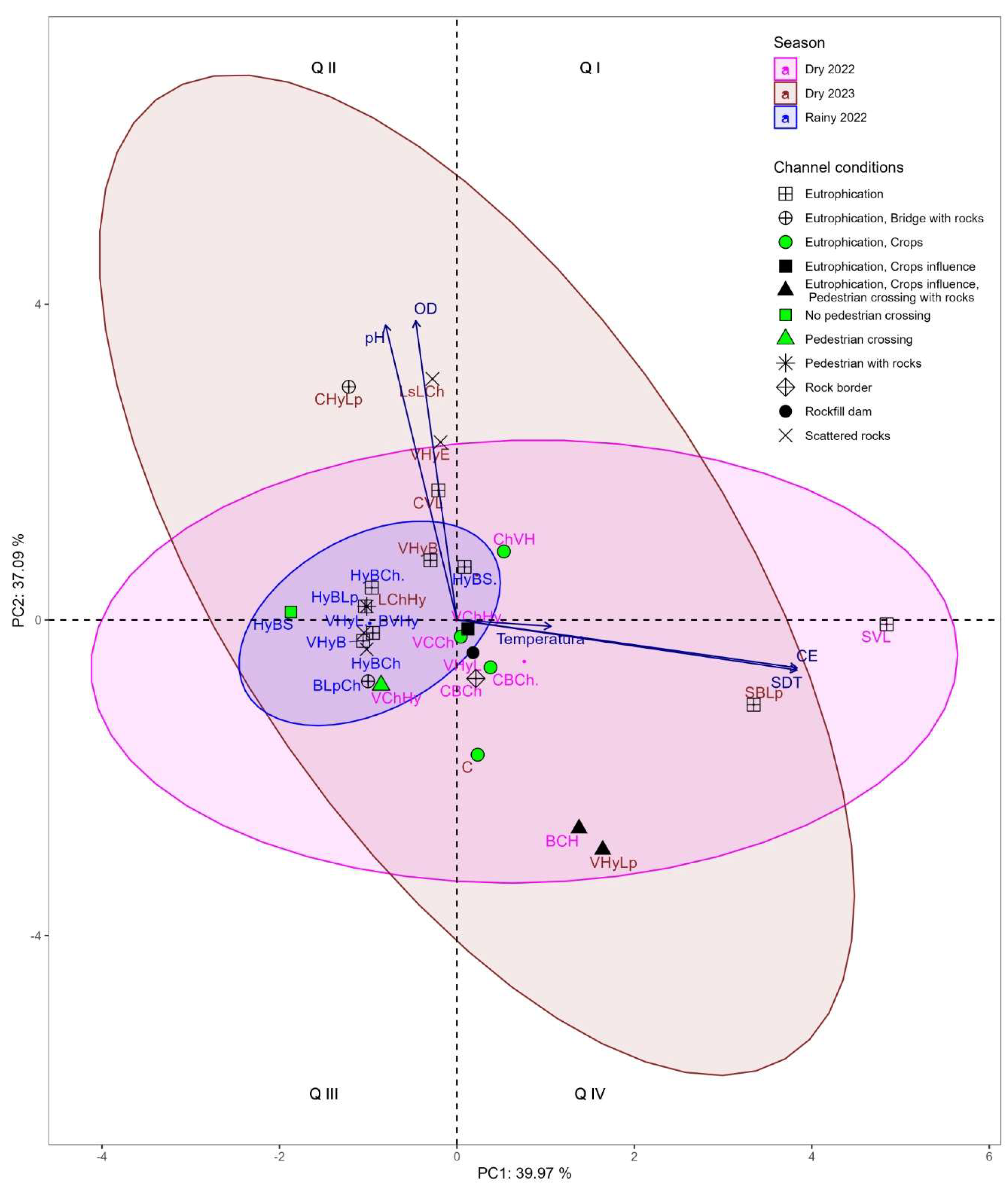

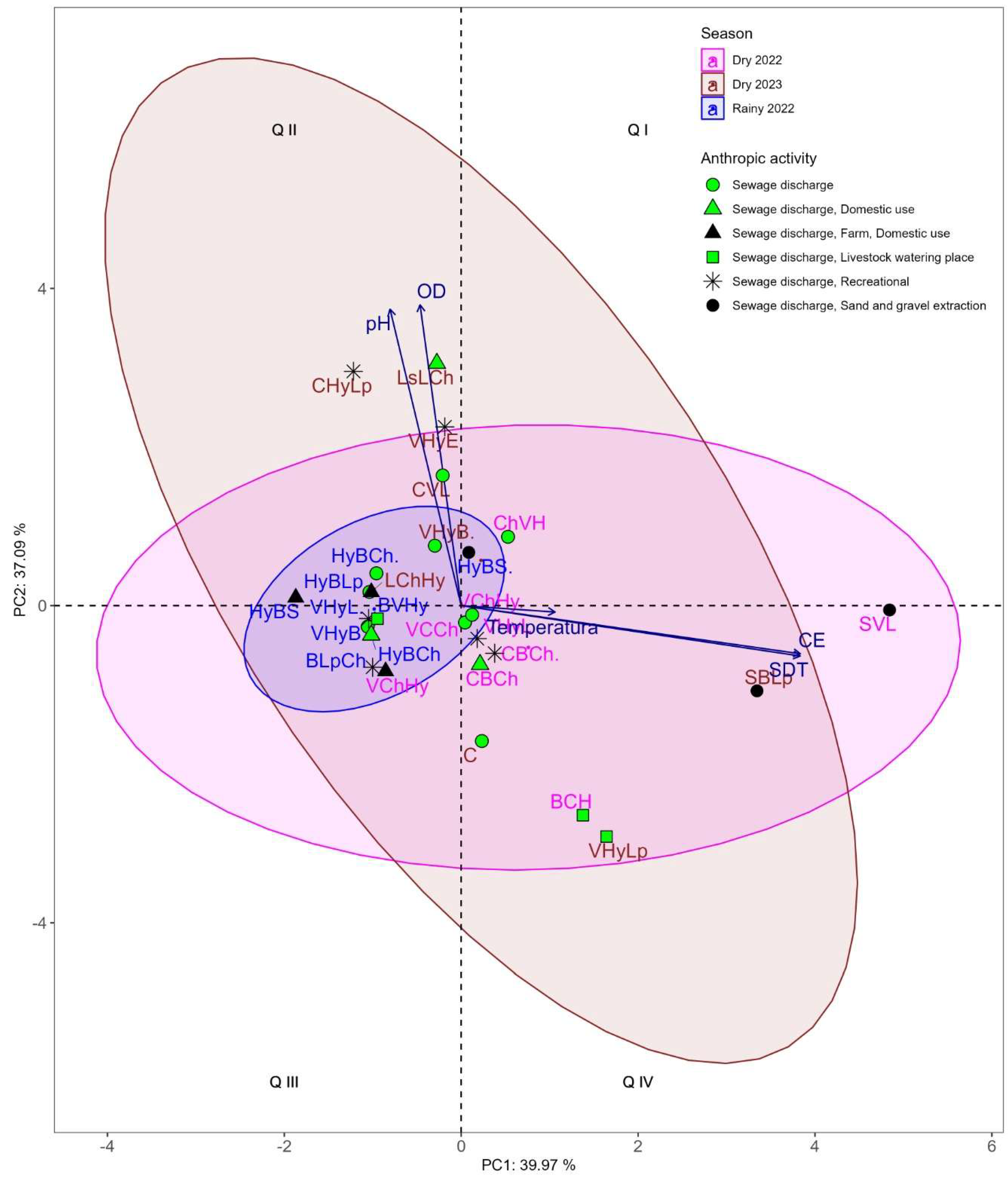

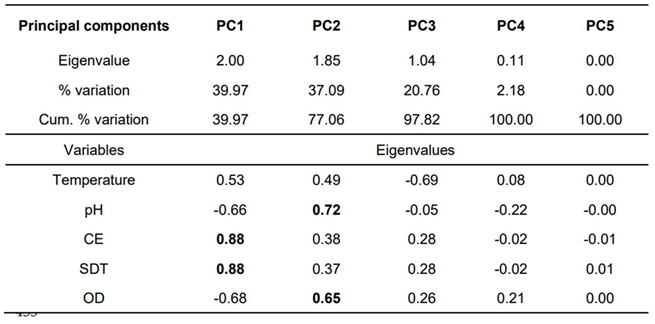

3.2.1. Principal Component Analysis of Physicochemical Variables

4. Discussion

4.1. Anthropic Influence and the Relationship of Macroinvertebrates are Present in the Study Area.

4.2. Physicochemical Parameters

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Garcia, X.; Pargament, D. Rehabilitating rivers and enhancing ecosystem services in a water-scarcity context: the Yarqon River. International Journal of Water Resources Development 2015, 31, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincón-Bello, M.T.; Soler-Romero, F.Y.; Calderón-Rivera, D.S.; Sierra-Parada, R.J.; Jaramillo-Londoño, A.M. Macroinvertebrados acuáticos como bioindicadores de calidad de agua en el río Chicú, Cundinamarca, Colombia. Hidrobiológica 2021, 31, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco-González, C.E.; Ocasio-Torres, M.E. Aquatic Macroinvertebrates as Bioindicators of Water Quality: A Study of an Ecosystem Regulation Service in a Tropical River. Ecologies 2023, 4, 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odum, E.P. Ecología; Nueva Editorial Interamericana. México, D.F.: 1972.

- Gudiño-Sosa, L.F.; Moncayo-Estrada, R.; Velázquez-Machuca, M.A.; Cruz-Cárdenas, G.; Ávila-Meléndez, L.A.; Pimentel-Equihua, J.L. Biotic Integrity, Water Quality, and Landscape Characteristics of a Subtropical River. Water 2023, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudiño-Sosa, L.F.; Escalera-Gallardo, C.; Cruz-Cárdenas, G.; Moncayo-Estrada, R.; Silvia-García, J.T.; Flores-Magallón, R.; Damián-Arroyo, M.; Chávez-Tinoco, M.A. Evaluación de la calidad del agua en un río subtropical y tributarios utilizando índices fisicoquímicos y macroinvertebrados acuáticos. Hidrobiológica 2022, 32, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Picos, R.A.; Kohlmann, B.; Sedeño-Díaz, J.E.; López-López, E. Assessing ecological impairments in Neotropical rivers of Mexico: calibration and validation of the Biomonitoring Working Party Index. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2017, 14, 1835–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Informe Mundial de las Naciones Unidas sobre el Desarrollo de los Recursos Hídricos 2023. Alianzas y cooperación por el agua. Datos, cifras y ejemplos de acción. Available online: https://www.pseau.org/outils/ouvrages/un_water_unesco_informe_mundial_de_las_naciones_unidas_sobre_el_desarrollo_de_los_recursos_hidricos_2023_alianzas_y_cooperacion_por_el_agua_datos_cifras_y_ejemplos_de_accion_2023.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2024).

- UNESCO. Informe Mundial de las Naciones Unidas sobre el Desarrollo de los Recursos Hídricos 2023. Alianzas y cooperación por el agua. Available online: https://aneas.com.mx/wp-content/pdf/documentos-internacionales/05-un-wwdr-2023-spanish_web-version.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2024).

- CDP. Treading water. Corporate Responses to Rising Water Challenges. Available online: https://cdn.cdp.net/cdp-production/cms/reports/documents/000/004/232/original/CDP_Global_Water_Report_2018.pdf?1554392583 (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Flörke, M.; Schneider, C.; McDonald, R.I. Water competition between cities and agriculture driven by climate change and urban growth. Nature Sustainability 2018, 1, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Austria, P.F. Los retos de la seguridad hídrica. Tecnología y Ciencias del Agua 2013, 4, 165–180. [Google Scholar]

- CESOP. En contexto: Los ríos revueltos, radiografía de la contaminación. Available online: http://www5.diputados.gob.mx/index.php/camara/Centros-de-Estudio/CESOP/Novedades/En-contexto.-Los-rios-revueltos-radiografia-de-la-contaminacion (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- CONAPO. Informe anual sobre la situación de pobreza y rezago social 2023. Guerrero. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/793094/12020-Copanatoyac23.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Rodríguez, A.L.; López, R.; Bautista, S. Culturas adaptativas en la cuenca del río Tlapaneco, Guerrero, México. Tlamati 2015, 6, 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo-Villanueva, J.L.; Galindo-de-Jesús, G.; Bustamante-González, Á.; Cervantes-Vargas, J. Valoración económica del agua del río Tlapaneco en la "Montaña de Guerrero", México. Tropical and subtropical agroecosystems 2013, 16, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEGI. Compendio de información geográfica municipal 2010. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/app/mexicocifras/datos_geograficos/12/12020.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2024).

- CONAGUA. Normales Climatológicas por Estado. Base de datos climatológica nacional. Available online: https://smn.conagua.gob.mx/tools/RESOURCES/Normales_Climatologicas/Mensuales/gro/mes12178.txt (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Mafla, M. Guía para Evaluaciones Ecológicas Rápidas con Indicadores Biológicos en Ríos de Tamaño Mediano Talamanca-Costa Rica. Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza, CATIE, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Merritt, R.W.; Cummins, K.W.; Berg, M.B. An introduction to the aquatic insects of North America. Kendall/Hunt, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez Fonseca, P.E.; Alonso-Rodríguez, A.M. Guía fotográfica de familias de macroinvertebrados acuáticos de Puerto Rico. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/295854904_Guia_fotografica_de_familias_de_macroinvertebrados_acuaticos_de_Puerto_Rico (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- Bartlett, M.S. Properties of Sufficiency and Statistical Tests. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences 1937, 160, 268–282. [Google Scholar]

- Box, G.E.P.; Cox, D.R. An Analysis of Transformations. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Metholodogical) 1964, 26, 211–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conover, W.J. Practical Nonparametric Statistics. John Wiley y Sons, Inc., 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.A.; Wichern, D.W. Applied Multivariate Statistical Analysis. Pearson Education, Inc., 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mavrou, I. Análisis factorial exploratorio: Cuestiones conceptuales y metodológicas. Nebrija de Lingüística Aplicada a la Enseñanza de las Lenguas 2015, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante-González, A.; Galindo-De Jesús, G.; Jaramillo-Villanueva, J.L.; Vargas-López, S. Percepción de la contaminación del río Tlapaneco por la población ribereña. Agricultura, Sociedad y Desarrollo 2016, 13, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Tierras, T.; Suárez-Cedillo, S.; Morales-León, V.; Vargas-Tierras, Y.; Tinoco-Jaramillo, L.; Viera-Arroyo, W.; Vásquez-Castillo, W. Ecological River Water Quality Based on Macroinvertebrates Present in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oscoz, J.; Galicia, D.; Miranda, R. Identification Guide of Freshwater Macroinvertebrates of Spain. Springer, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, L.; Ríos, P.; Espinosa, M.; Cedeño, P.; Jiménez, G. Caracterización de la calidad de agua mediante macroinvertebrados bentónicos en el río Puyo, en la Amazonía Ecuatoriana. Hidrobiológica 2016, 26, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, Y.; Grover, A.; Sinha, R. Differential distribution of macroinvertebrate associated with water quality. World Water Policy 2023, 9, 84–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, S.; Forio, M.A.E.; Lock, K.; Vandenbroucke, M.; Oña, T.; Gualoto, M.; Goethals, P.L.M.; Van der heyden, C. Variations in Benthic Macroinvertebrate Communities and Biological Quality in the Aguarico and Coca River Basins in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Water 2021, 13, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enger, E.; Smith, B.F. Ciencia Ambiental. Un estudio de interrelaciones. The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Echeverría-Sáenz, S.; Ugalde-Salazar, R.; Guevara-Mora, M.; Quesada-Alvarado, F.; Ruepert, C. Ecological Integrity Impairment and Habitat Fragmentation for Neotropical Macroinvertebrate Communities in an Agricultural Stream. Toxics 2022, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrera, M.; Capparelli, M.V.; Nacato-Ch, C.; Moulatlet, G.M.; Lopez-Heras, I.; Diaz, M.; Alvear-S, D.; Rico, A. Effects of intensive agriculture and urbanization on water quality and pesticide risks in freshwater ecosystems of the Ecuadorian Amazon. Chemosphere 2023, 337, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrera-Garcia, S.; Goethals, P.L.M.; Lock, K.; Domínguez-Granda, L.; Villacís, M.; Galárraga-Sánchez, R.; Van der Heyden, C.; Forio, M.A.E. Taxonomic and Feeding Trait-Based Analysis of Macroinvertebrates in the Antisana River Basin (Ecuadorian Andean Region). Biology 2023, 12, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coayla-Peñaloza, P.; Cheneaux-Díaz, A.A.; Moreno-Salazar, C.V.; Cruz-Remache, C.E.; Colque-Rondón, E.W.; Damborenea, C. Benthic macroinvertebrate communities and water quality assessment in high Andean wetlands Callali-Oscollo, Arequipa-Cusco, Peru. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 2023, 94, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesada-Alvarado, F.; Umaña, G.; Springer, M.; Picado, J. Variación estacional y características fisicoquímicas e hidrológicas que influyen en los macroinvertebrados acuáticos, en un río tropical. Biología Tropical 2020, 68, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flowers, R.W.; De la Rosa, C. Capítulo 4. Ephemeroptera. Revista de Biología Tropical 2010, 58, 63–93. [Google Scholar]

- Damanik-Ambarita, M.N.; Lock, K.; Boets, P.; Everaert, G.; Nguyen, T.H.T.; Forio, M.A.E.; Musonge, P.L.S.; Suhareva, N.; Bennetsen, E.; Landuyt, D. , et al. Ecological water quality analysis of the Guayas river basin (Ecuador) based on macroinvertebrates indices. Limnologica 2016, 57, 27–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafuente, W.; Carpio, A.J.; Alcácer, C.; Moreno, J.L. Spatio-temporal variability of physicochemical conditions in the headwaters of neotropical streams. Journal of South American Earth Sciences 2023, 126, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihelcic, J.R.; Zimmerman, J.B. Ingeniería ambiental: fundamentos, sustentabilidad, diseño. Editorial Alfaomega, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Molinero, J.; Barrado, M.; Guijarro, M.; Ortiz, M.; Carnicer, O.; Zuazagoitia, D. The Teaone River: a snapshot of a tropical river from the coastal region of Ecuador. Limnetica 2019, 38, 587–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, J.; Roldán, G.; Arango, A.; Álvarez, L.F. Evaluación de la calidad del agua de las microcuencas La Laucha, La Lejía y La Rastrojera utilizando los macroinvertebrados como bioindicadores, Municipio de Durania, Departamento Norte de Santander, Colombia. Revista de la Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales 2008, 32, 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contieri, B.B.; Rosa, J.; Scoarize, M.M.R.; Urbano, V.A.; Benedito, E. Anthropogenic land uses lead to changes in limnological variables in Neotropical streams. Environ Monit Assess 2024, 196, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sampling sites | Permanent anthropic activity | The Dry season 2022 |

The Rainy season 2022 | The Dry season 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS1 |

Sewage discharge, Farm, Domestic use, Leaving the urban Patlicha area, Crops area | Pedestrian crossing | No pedestrian crossing | Pedestrian with rocks |

| SS2 | Sewage discharge, Crops area | Eutrophication, Partial crops in the riverbed | Eutrophication | Eutrophication |

| SS3 | Sewage discharge, Crops area | Eutrophication, Crops influence | Eutrophication | Eutrophication |

| SS4 | Sewage discharge, Recreational, Entrance to the Copanatoyac urban area, Crops area | Rockfill dam | Scattered rocks | Scattered rocks |

| SS5 | Sewage discharge, Domestic use, Center of the Copanatoyac urban area, Crops area | Rock border | Scattered rocks, anthropogenic silting | Scattered rocks, concrete remains |

| SS6 | Sewage discharge, Recreational, Leaving the urban Copanatoyac area, Crops area | Eutrophication Riparian zone cultivation | Eutrophication, Bridge with rocks and concrete remains | Eutrophication, Bridge with rocks and concrete remains |

| SS7 | Sewage discharge, Crops area | Eutrophication, Partial crops in the riverbed | Eutrophication | Eutrophication, Total cultivation in the riverbed |

| SS8 | Sewage discharge, Livestock watering place, Crops area | Eutrophication, Crops influence, Pedestrian crossing with rocks | Eutrophication | Eutrophication, Crops influence, Pedestrian crossing with rocks |

| SS9 | Sewage discharge, Sand and gravel extraction, Crops area | Eutrophication | Eutrophication | Eutrophication |

| Sampling sites | The dry season 2022 | The rainy season 2022 | The dry season 2023 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Families | Abundance | Families | Abundance | Families | Abundance | |

| SS1 | Veliidae | 61 | Hydropsychidae | 78 | Leptohyphidae | 78 |

| Chironomidae | 50 | Baetidae | 55 | Chironomidae | 64 | |

| Hidropsychidae | 35 | Simuliidae | 8 | Hidropsychidae | 6 | |

| SS2 | Veliidae | 439 | Hydropsychidae | 81 | Veliidae | 335 |

| Corixidae | 31 | Baetidae | 21 | Hydropsychidae | 46 | |

| Chironomidae | 23 | Leptophlebiidae | 7 | Baetidae | 31 | |

| SS3 | Veliidae | 89 | Veliidae | 181 | Corixidae | 62 |

| Chironomidae, | 50 | Hydropsychidae | 56 | Veliidae | 42 | |

| Hydropsychidae | 32 | Baetidae | 14 | Leptohyphidae | 18 | |

| SS4 | Veliidae | 383 | Veliidae | 231 | Veliidae | 147 |

| Hydropsychidae | 56 | Hydropsychidae | 105 | Hydropsychidae | 50 | |

| Leptohyphidae | 8 | Leptohyphidae | 21 | Ephemerellidae | 37 | |

| SS5 | Corixidae | 69 | Hydropsychidae | 42 | Lestidae | 26 |

| Baetidae | 60 | Baetidae | 39 | Leptohyphidae | 21 | |

| Chironomidae | 43 | Chironomidae | 11 | Chironomidae | 14 | |

| SS6 | Corixidae | 69 | Baetidae | 51 | Corixidae | 45 |

| Baetidae | 30 | Leptophlebiidae | 8 | Hydropsychidae | 43 | |

| Chironomidae | 11 | Chironomidae | 7 | Leptophlebiidae | 29 | |

| SS7 | Chironomidae | 63 | Hydropsychidae | 170 | Corixidae | 125 |

| Veliidae | 28 | Baetidae | 44 | |||

| Hydrophilidae | 6 | Chironomidae | 13 | |||

| SS8 | Baetidae, | 18 | Baetidae | 81 | Veliidae | 138 |

| Corixidae | 10 | Veliidae | 56 | Hydropsychidae | 22 | |

| Hydrophilidae | 6 | Hydropsychidae | 37 | Leptophlebiidae | 17 | |

| SS9 | Simuliidae | 136 | Hydropsychidae | 100 | Simuliidae | 225 |

| Veliidae | 70 | Baetidae | 77 | Baetidae | 70 | |

| Leptohyphidae | 31 | Simuliidae | 9 | Leptophlebiidae | 19 | |

| Fuente | Df | Sum Sq | Mean Sq | F value | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Season | 2 | 425.852 | 212.926 | 1.192 | 0.326 |

| Zone | 2 | 11.630 | 5.815 | 0.033 | 0.968 |

| Season: Zone | 4 | 240.815 | 60.204 | 0.337 | 0.849 |

| Residuals | 18 | 3,215.333 | 178.630 |

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).