Submitted:

14 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

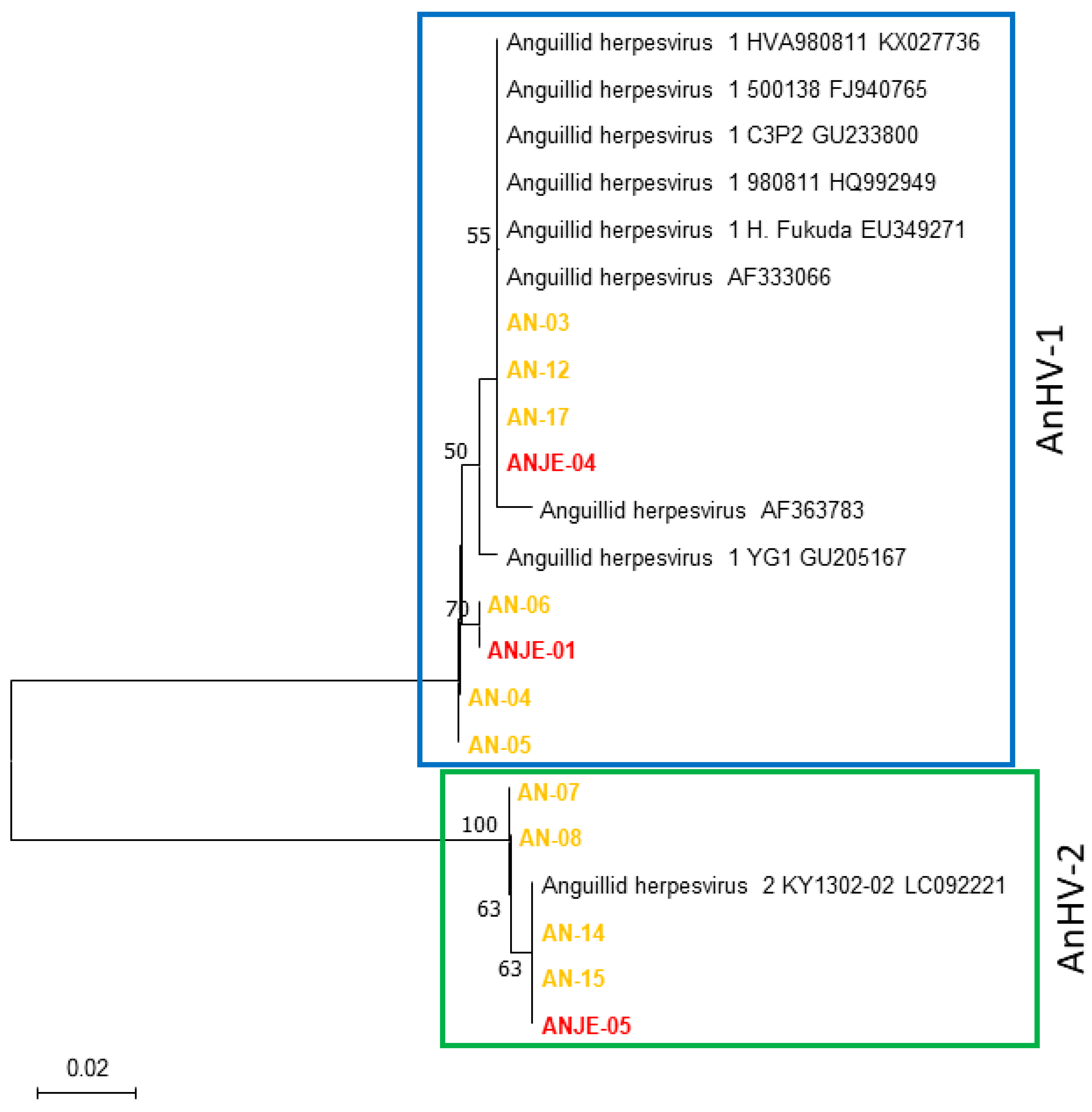

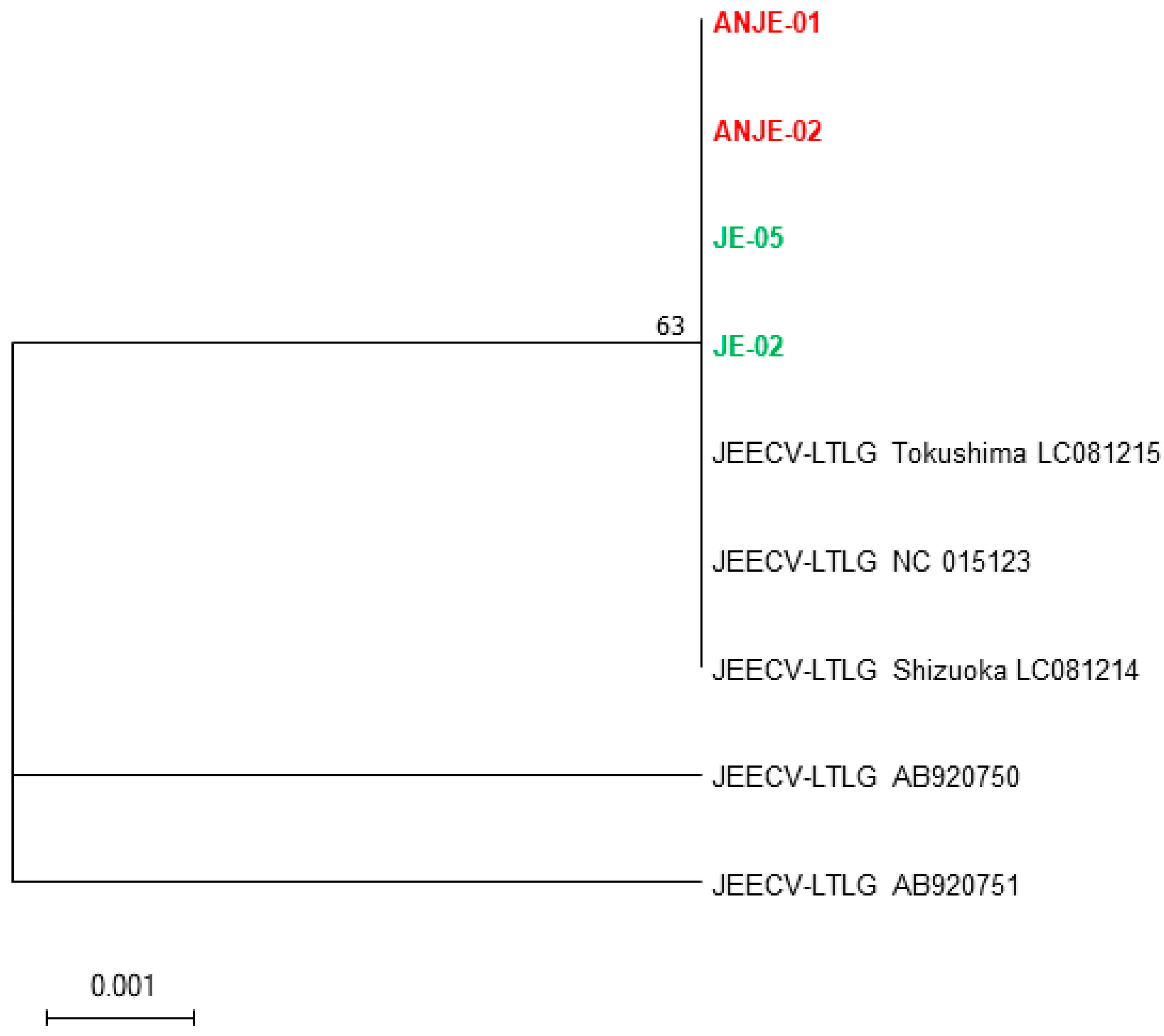

2.1. Phylogenetic Relationships of Target Genes

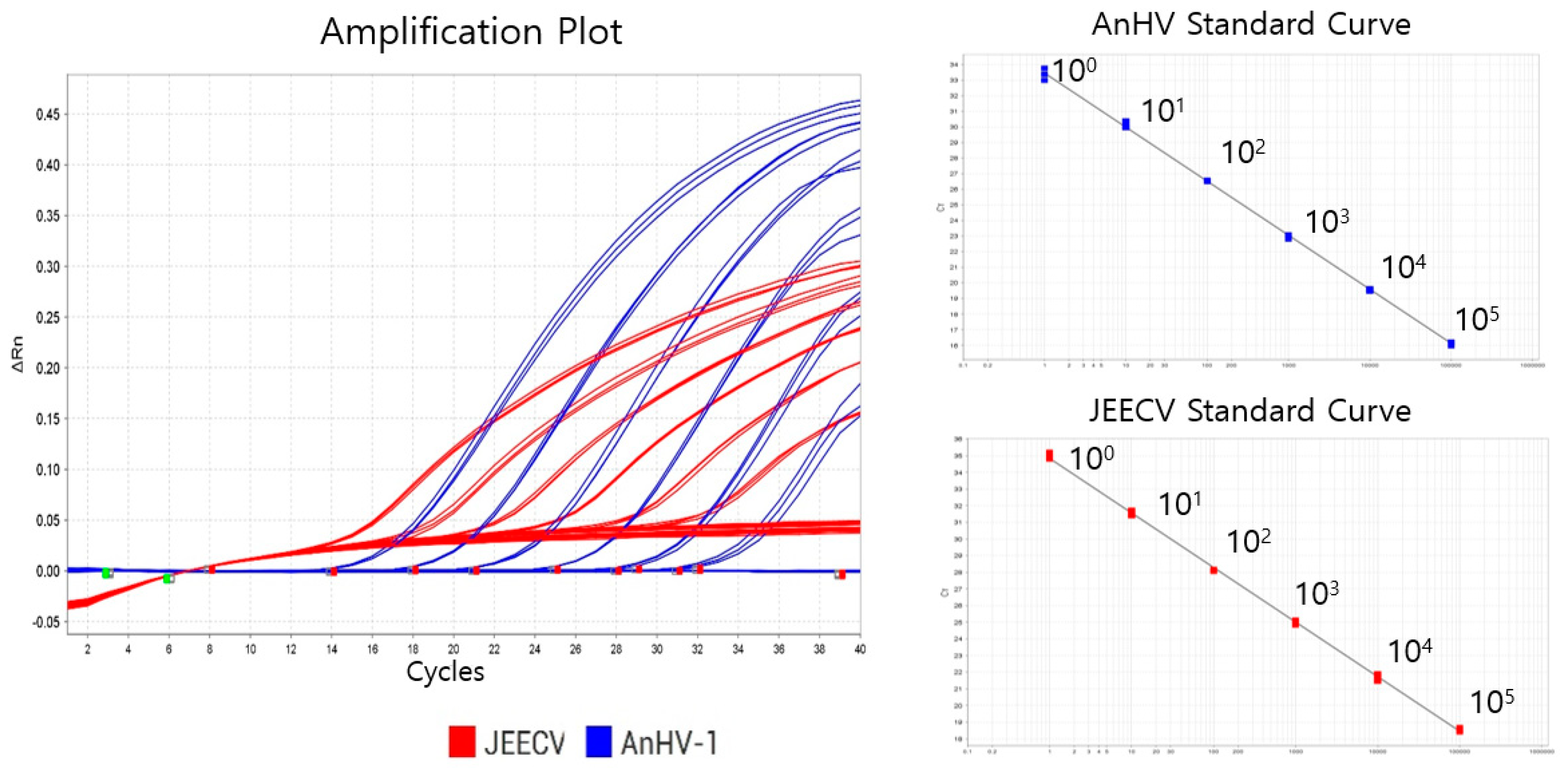

2.2. Optimization of Duplex qPCR

2.3. Standard Curve

2.4. Sensitivity of the qPCR Marker

2.5. Spike Tests on Culture Water

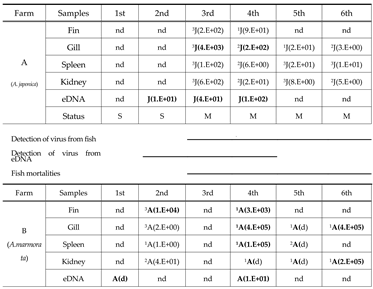

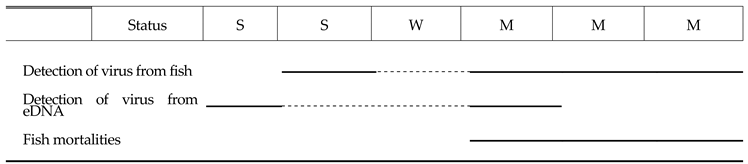

2.6. Validation of the QPCR Diagnostic Method for Monitoring Viral Outbreaks in Eel Farms

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Fish Sampling

4.2. Sequencing of Target Genes

4.3. Design and Verification of QPCR Markers

4.4. Optimization of QPCR Conditions

4.5. Standard Curves

4.6. Sensitivity Tests

4.7. Spike Tests Using Culture Water

4.8. Validation of the QPCR Diagnostic Method for Monitoring Viral Outbreaks in Eel Farms

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| eDNA | Environmental DNA |

| qPCR | Quantitative PCR |

| JEECV | Japanese eel endothelial cell-infecting virus |

| AnHV | Anguilla herpesvirus |

| VECNE | Eel viral endothelial cell necrosis |

| RAS | Recirculating aquaculture systems |

| Pol | DNA polymerase catalytic subunit |

| Ltlg | Polyomavirus large T-antigen-like protein of JEECV |

References

- Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries Statistics System; https://www.mof.go.kr/statPortal/search/searchList.do, accessed May 2, 2023.

- Jang, M.H.; Lee, N.; Cho, M.; Song, J. Status and characteristics of JEECV (Japanese eel endothelial cell-infecting virus) and AnHV (anguillid herpesvirus 1) infections in domestic farmed eels Anguilla japonica, Anguilla bicolor and Anguilla marmorata. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci.; Kor 2021, 54, 668–675.

- Kim, H. J.; Yu, J. H.; Kim, D. W.; Kwon, S. R.; Park, S. W. Molecular evidence of anguillid herpesvirus-1 (AngHV-1) in the farmed japanese eel, Anguilla japonica Temminck & schlegel, in korea. J. Fish Dis., Kor 2012, 35(4).

- Kim, S.M.; Ko, S.M.; Jin, J.H.; Seo, J.S.; Lee, N.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Gu, J.H.; Bae, Y.R. Characteristics of viral endothelial cell necrosis of eel (VECNE) from culturing eel (Anguilla japonica, Anguilla bicolor) in Korea. J. Ichthyol.; Kor 2018, 30, 185–193.

- Park, S.; Jung, E.; Kim, D. Outbreak of anguillid herpesvirus-1 (AngHV-1) infection in cultured shortfin eel (Anguilla bicolor) in Korea. J. Fish Pathol. 2012, 25, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egusa, S.; Tanaka, M.; Ogami, H.; Oka, H. Histopathological observations on an intense congestion of the gills in cultured Japanese eel Anguilla japonica. Fish Pathol.; Kor 1989, 24, 51-56.

- Mizutani, T.; Sayama, Y.; Nakanishi, A.; Ochiai, H.; Sakai, K.; Wakabayashi, K.; Tanaka, N.; Miura, E.; Oba, M.; Kurane, I.; et al. Novel DNA virus isolated from samples showing endothelial cell necrosis in the Japanese eel, Anguilla japonica. Virology 2011, 412, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sano, M.; Fukuda, H.; Sano, T. Isolation and characterization of a new herpesvirus from eel. Pathol. Mar. Sci. 1990, 15, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, P.H.; Pan, Y.H.; Wu, C.M.; Kuo, S.T.; Chung, H.Y. Isolation and molecular characterization of herpesvirus from cultured European eels Anguilla anguilla in Taiwan. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 2002, 50, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, T.; Miyazaki, T. Characterization and pathogenicity of a herpesvirus isolated from cutaneous lesion in Japanese eel, Anguilla japonica. Fish Pathol. 1997, 32, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , 1999 Lee N.S.; Kobayashi J.; Miyazaki T. Gill filament necrosis in farmed Japanese eels, Anguilla japonica (Temminck & Schlegel), infected with herpesvirus anguillae. J. Fish Dis. 1999, 22, 457–463. [Google Scholar]

- Ueno, Y.; Shi, J.W.; Yoshida, T.; Kitao, T.; Sakai, M.; Chen, S.N.; Kou, G.H. Biological and serological comparisons of eel herpesvirus in Formosa (EHVF) and herpesvirus anguillae (HVA). J. Appl. Ichthyol. 1996, 12, 49–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijsewijk, F.; Pritz-Verschuren, S.; Kerkhoff, S.; Botter, A.; Willemsen, M.; van Nieuwstadt, T.; Haenen, O. Development of a polymerase chain reaction for the detection of anguillid herpesvirus DNA in eels based on the herpesvirus DNA polymerase gene. J. Virol. Method. 2005, 124, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidse, A.; Haenen, O.L.M.; Dijkstra, S.G.; van Nieuwstadt, A. P.; van der Vorst, T. J. K.; Wagenaar, F.; Wellenberg, G. J. First isolation of herpesvirus of eel (Herpesvirus anguillae) in diseased European eel (Anguilla anguilla L.) in Europe. In: Bulletin of the European Association of Fish Pathologists. 1999, 19(4), 137-141.

- Guo, R.; Zhang, Z.; He, T.; Li, M.; Zhuo, Y.; Yang, X.; Fan, H.; Chen, X. Isolation and identification of a new isolate of anguillid herpesvirus 1 from farmed American eels (Anguilla rostrata) in China. Viruses 2022, 14, 2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panicz, R.; Eljasik, P.; Nguyen, T.T.; Vo Thi, K.T.; Hoang, D.V. First detection of herpesvirus anguillae (AngHV-1) associated with mortalities in farmed giant mottled eel (Anguilla marmorata) in Vietnam. J. Fish Dis. 2021, 44, 847–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Beurden, S.J.; Engelsma, M.Y.; Roozenburg, I.; Voorbergen-Laarman, M.A.; van Tulden, P.W.; Kerkhoff, S.; van Nieuwstadt, A.P.; Davidse, A.; Haenen, O.L.M. Viral diseases of wild and farmed European eel Anguilla anguilla with particular reference to the Netherlands. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 2012, 101, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, C.M.; Liu, P.C.; Nan, F.H. Complete Genome Sequence of Herpesvirus anguillae Strain HVA980811 Isolated in Chiayi, Taiwan. Genome Announc. 2017, 5, 01677–01616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kole, S.; Kim, H.J.; Jung, S.J. Complete genome sequence of anguillid herpesvirus 1 isolated from imported Anguilla rostrata (American eel) from Canada. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2022, 11, e0082922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Beurden, S.J.; Bossers, A.; Voorbergen-Laarman, M.H.A.; Haenen, O.L.M.; Peters, S.; Abma-Henkens, M.H.C.; Peeters, B.P.H.; Rottier, P.J.M.; Engelsma, M.Y. Complete genome sequence and taxonomic position of anguillid herpesvirus 1. J. Gen. Virol. 2010, 91, 880–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.J.; Bathige, S.D.N.K.; Jeon, H.B.; Kim, S.H.; Yu, C.; Kang, W.; Noh, K.; Lee, E.; Lim, B.S.; Shin, D.H. Development of a duplex qPCR assay for the detection of coinfection in eels by Japanese eel endothelial cell-infecting virus and anguillid herpesvirus-1. Aquaculture 2024, 578, 740091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haramoto, E.; Katayama, H.; Oguma, K.; Ohgaki, S. Recovery of naked viral genomes in water by virus concentration methods. J. Virol. Method. 2007, 142, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haramoto, E.; Kitajima, M.; Katayama, H.; Ohgaki, S. Detection of koi herpesvirus DNA in river water in Japan. J. Fish Dis. 2007, 30, 59–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taengphu, S.; Kayansamruaj, P.; Kawato, Y.; Delamare-Deboutteville, J.; Mohan, C.V.; Dong, H.T.; Senapin, S. Concentration and quantification of tilapia tilapinevirus from water using a simple iron flocculation coupled with probe-based RT-qPCR. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weli, S.C.; Bernhardt, L.V.; Qviller, L.; Myrmel, M.; Lillehaug, A. Development and evaluation of a method for concentration and detection of salmonid alphavirus from seawater. J. Virol. Method. 2021, 287, 113990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohara, K.; Yadav, A.K.; Joshi, P. Detection of fish pathogens in freshwater aquaculture using eDNA methods. Diversity 2022, 14, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Virus | Target gene | PCR | Primer name | Sequence (5'→3') | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AnHV | Pol gene | 1st | 2061f | CAAGCTGAAGGAGAACAGAT | This study |

| 3086r | GTTCGTGATCAGAGAGTTGT | This study | |||

| Nested | 2108f | CCATGTGCTTGACTGAAAAG | This study | ||

| 3016r | TCCTCAAAGAACCACGCTTT | This study | |||

| JEECV | Ltlg gene | 1st | 0343f | TTTGTGCAGACTGTACTGGT | This study |

| 1455r | TACTCATTCATAGTGGCAATC | modified from Mizutani et al., 2011[7] | |||

| Nested | 0462f | AACAGGCATAGCAGTTGTGC | This study | ||

| 1219r | TCACCGTTCATGTTTAGGAC | modified from Mizutani et al., 2011[7] |

| Target virus | Primers and Probe | Sequence (5'→3') |

|---|---|---|

| AnHV | ANHV-Pol-2173f | AAGGTGTTTCAGCCYACCAT |

| ANHV-Pol-2587r | ATGAAGATCT GCGCCAACTC | |

| ANHV-Pol-2260p | Cy5-AGCAACATGTGCGACGCCAA-BHQ2 | |

| JEECV | JEECV-LTLG-0546f | CAATGTGATGCAGGTAGCAA |

| JEECV-LTLG-0777r | TCTGTTGGTCGCTTCGACAT | |

| JEECV-LTLG-0662p | HEX-TGGGCTTTGACTACACGATGCT-BHQ1 |

| No. | Host | Fish size | AnHV | JEECV | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cPCR | qPCR (copies/ml) | cPCR1 | qPCR (copies/ml) | |||||

| 1 | A. japonica | 50.5 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||

| 2 | A. japonica | 48.2 | ND | ND | ND | 1.1 | ||

| 3 | A. japonica | 42.3 | Positive | 2308.9 | ND | 2.9 | ||

| 4 | A. marmorata | 50.9 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||

| 5 | A. marmorata | 11.6 | Positive | 76209.1 | ND | ND | ||

| 6 | A. bicolor | No data | Positive | 711.7 | ND | 0.1 | ||

| 7 | A. japonica | No data | ND | ND | ND | 2104.5 | ||

| 8 | A. japonica | 56.7 | ND | 11 | ND | 0.8 | ||

| 9 | A. australis | 14.5 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||

| 10 | A. australis | 12.6 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||

| 11 | A. australis | 55.8 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||

| 12 | A. japonica | 53 | Positive | 1668.7 | ND | ND | ||

| 13 | A. japonica | 24.6 | ND | 0.6 | ND | 0.5 | ||

| 14 | A. japonica | 47 | ND | 28 | ND | ND | ||

| 15 | A. japonica | 43.5 | ND | 0.3 | ND | ND | ||

| 16 | A. bicolor | 39.5 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||

| 17 | A. japonica | 46.5 | Positive | 167.6 | ND | ND | ||

| 18 | A. australis | 13.9 | ND | 0.2 | ND | ND | ||

| 19 | A. japonica | 59.5 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||

| 20 | A. marmorata | 52.8 | ND | ND | Positive | ND | ||

| 21 | A. bicolor | 42.2 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||

| 22 | A. australis | 48 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||

| 23 | A. japonica | 53.4 | ND | ND | Positive | 2.5 | ||

| 24 | A. bicolor | No data | Positive | 464.9 | Positive | 0.3 | ||

| 25 | A. japonica | No data | ND | ND | Positive | 1182.9 | ||

| 26 | A. australis | 55.8 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||

| 27 | A. japonica | 53 | Positive | 218.5 | ND | ND | ||

| 28 | A. japonica | 24.6 | ND | 0.2 | ND | 0.3 | ||

| 29 | NTC-1 | ND | ND | ND | ND | |||

| 30 | NTC-2 | ND | ND | ND | ND | |||

| Sample Name | Sample volume (liters) | AnHV | JEECV | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cq value | Copy no. | Cq value | Copy no. | ||

| Ground water | 1 | ND | - | ND | - |

| Ground water | 2 | ND | - | ND | - |

| Ground water | 4 | ND | - | ND | - |

| Ground water | 10 | ND | - | ND | - |

| Spiked ground water | 1 | ND | - | 21.424 | 12,367 |

| Spiked ground water | 2 | ND | - | 19.606 | 44,250 |

| Spiked ground water | 4 | ND | - | 17.662 | 173,072 |

| Spiked ground water | 10 | ND | - | 16.556 | 375,871 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).