Submitted:

13 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

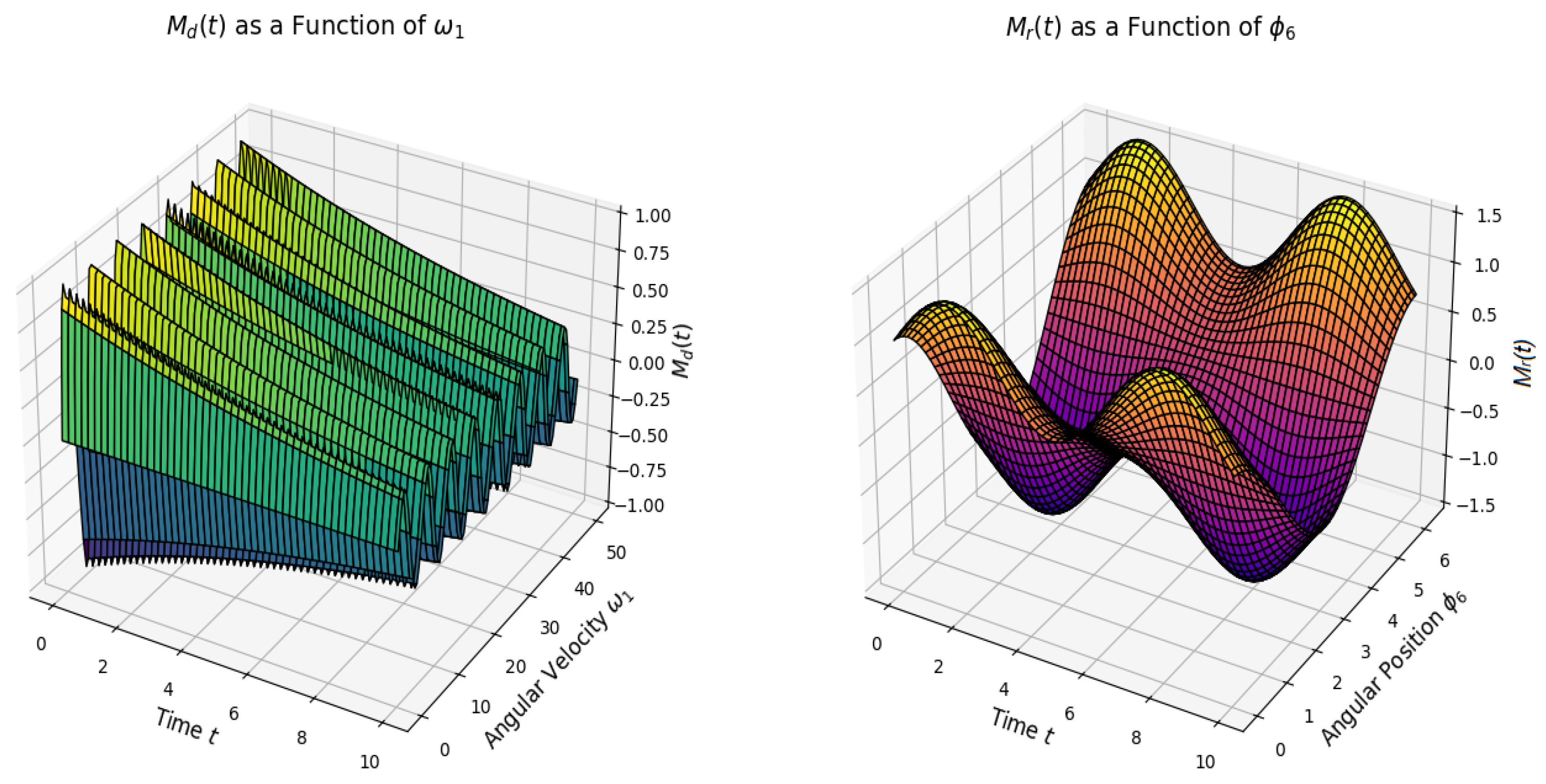

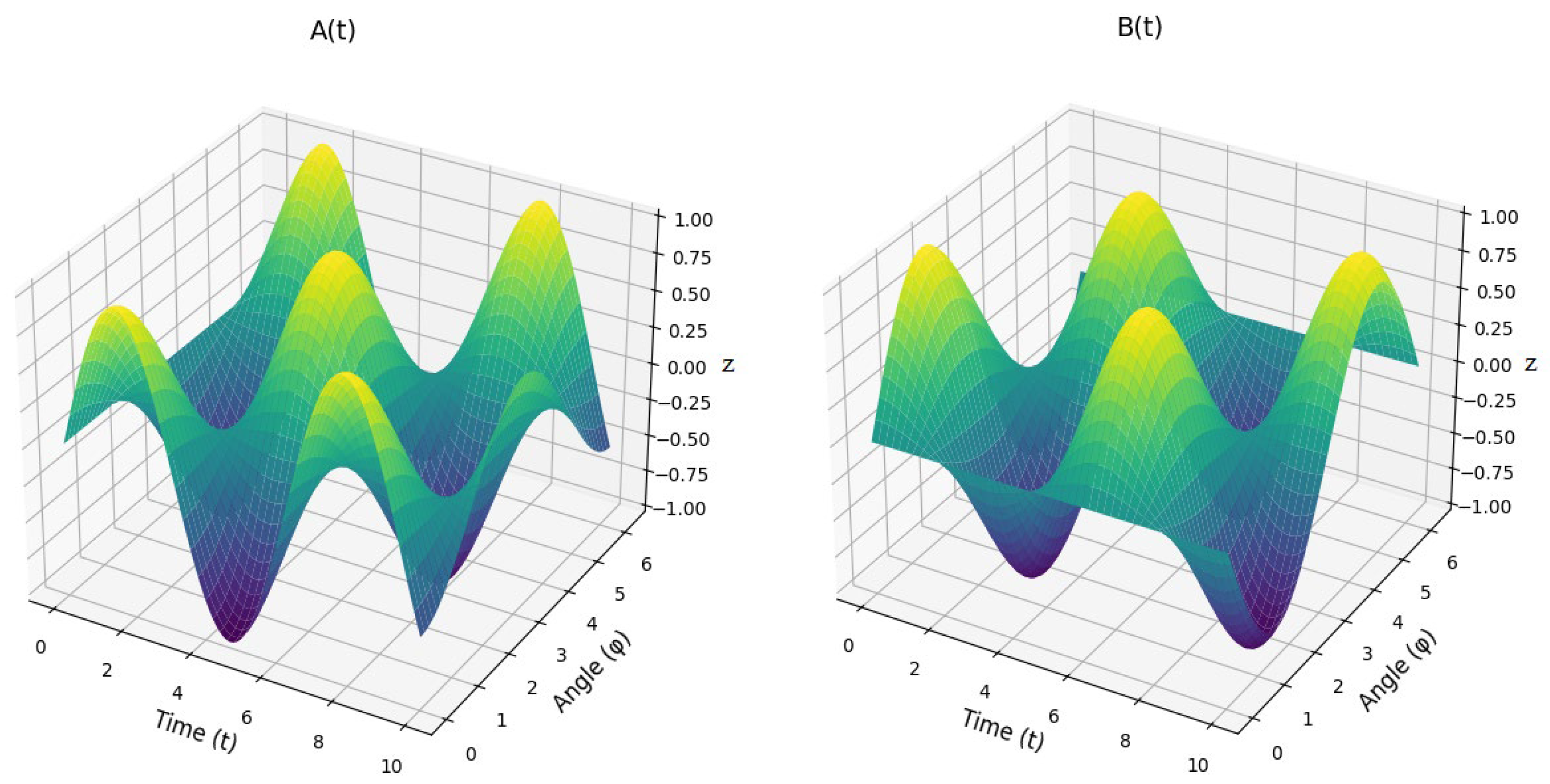

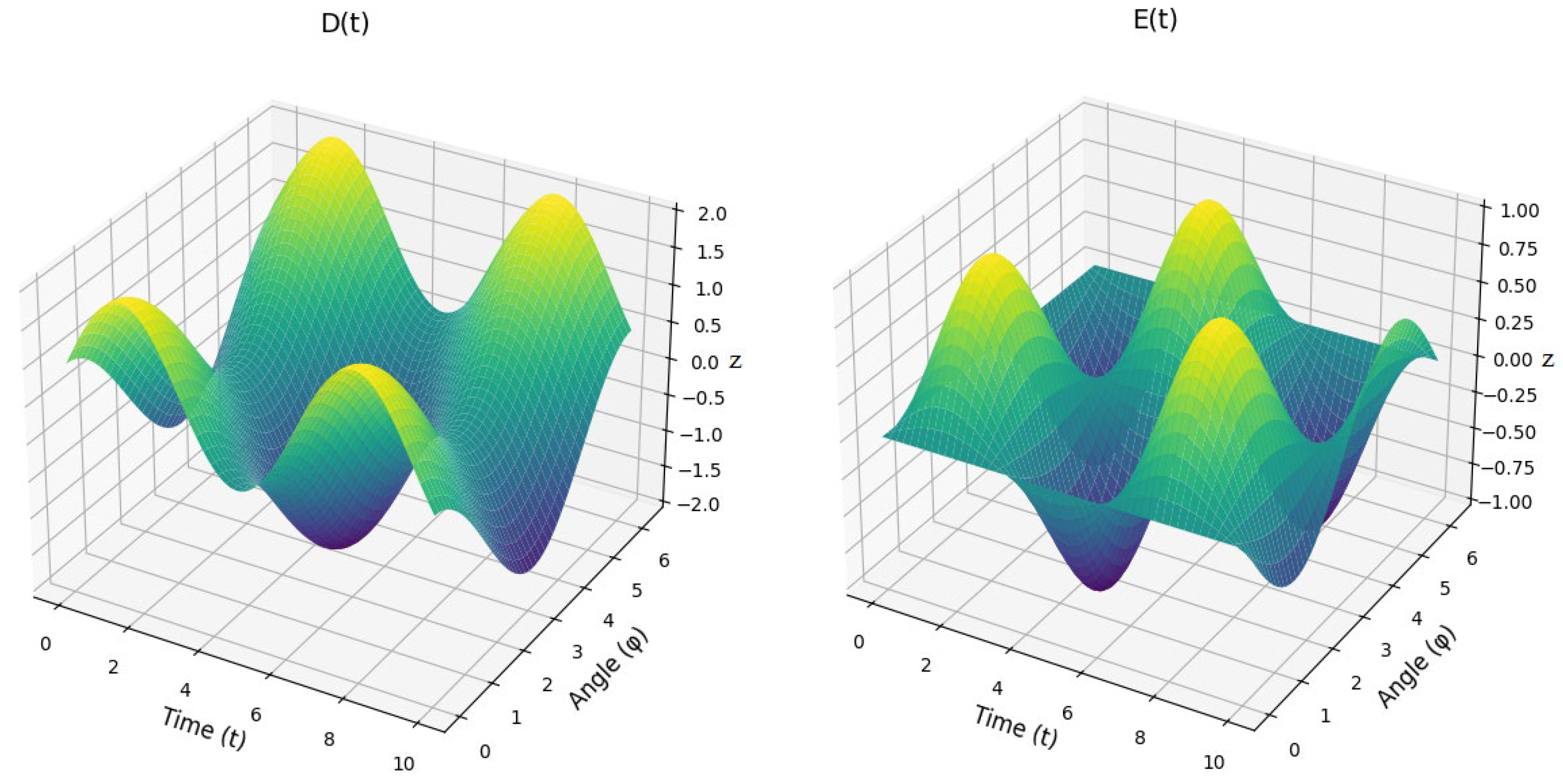

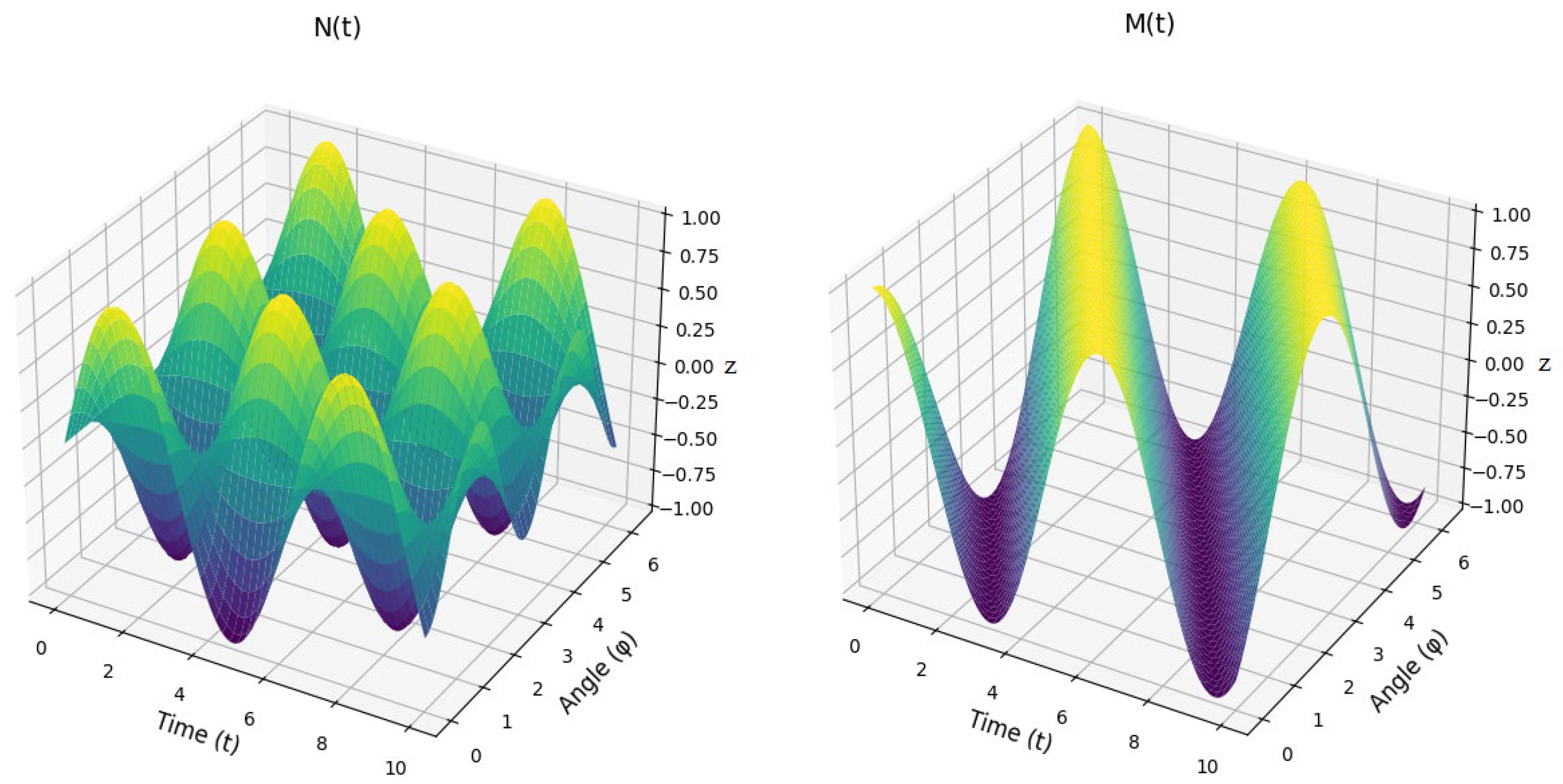

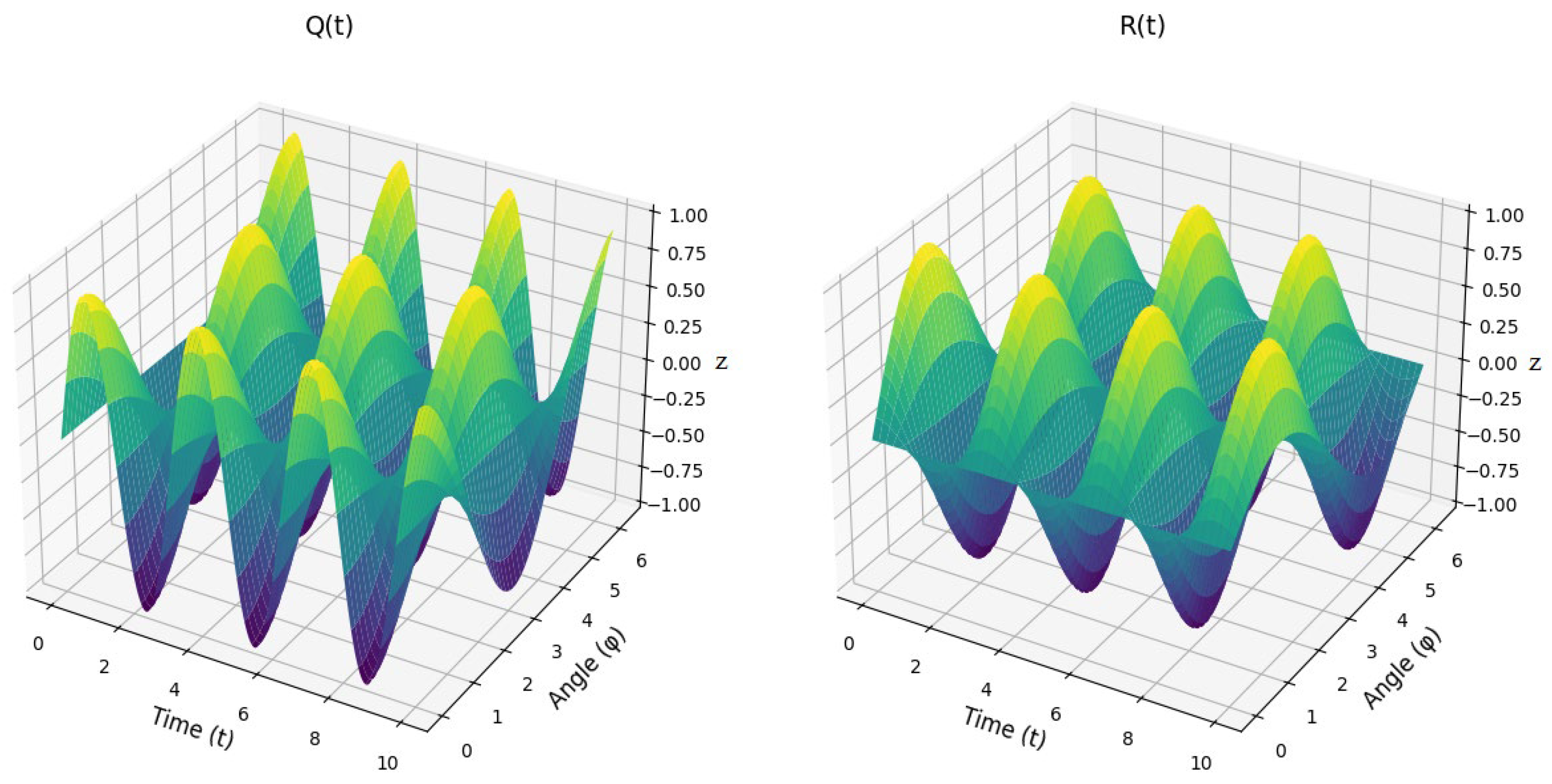

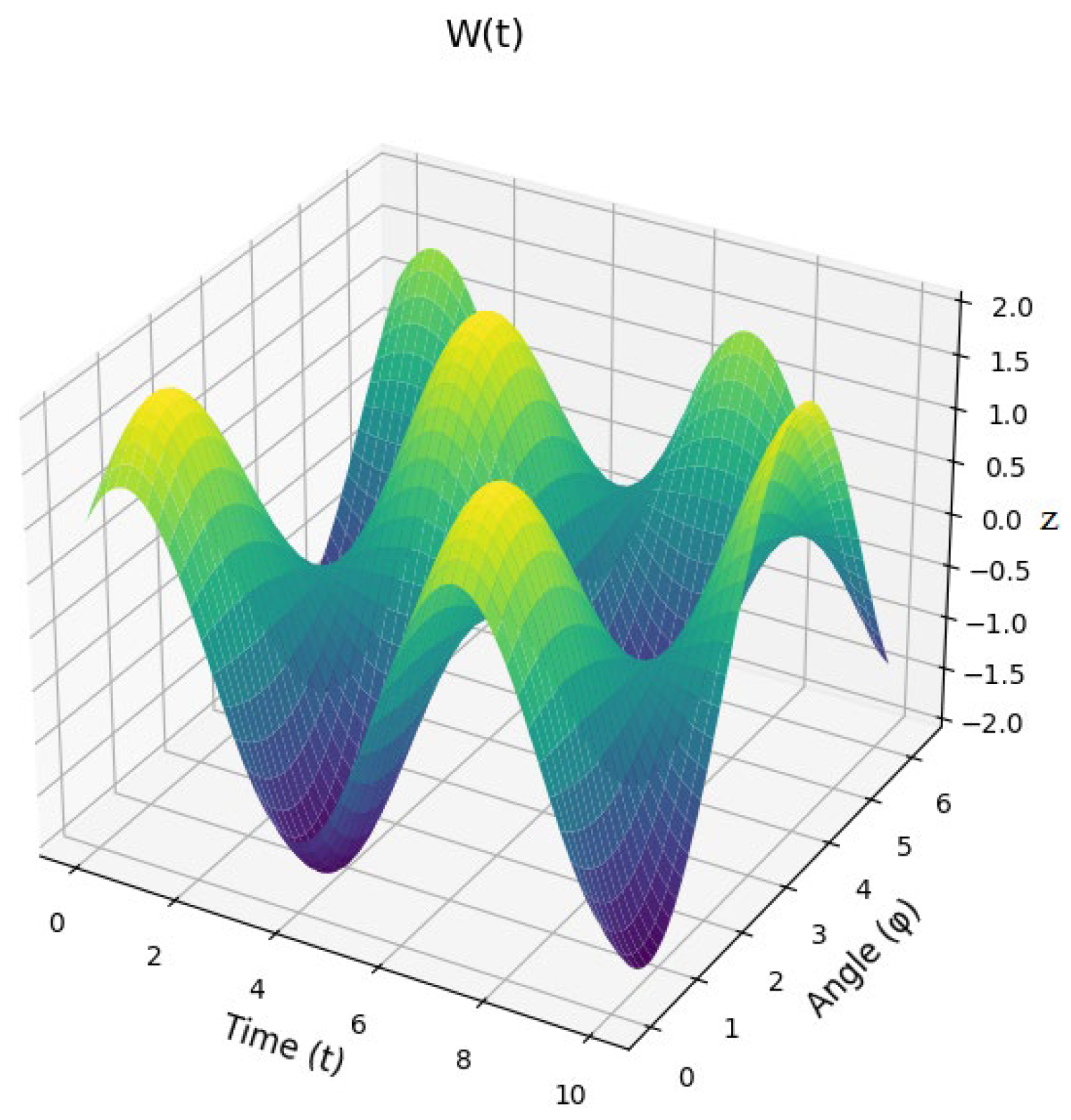

This paper presents a dynamic model for the oscillating conveyor mechanism, governed by a differential equation that describes the system’s motion under the influence of both driving and resisting torques. The resistive torque Mr is modeled as a linear function of angular displacement φ6, while the driving torque Md incorporates a damping term proportional to the angular velocity ω1 . The system’s inertial properties are captured through time-dependent terms such as as A(t), B(t), D(t), E(t), F(t), H(t), N(t), M(t), Q(t), R(t), and W(t), which account for the interaction between the mechanical components, including the angular positions and velocities of the system’s joints. A numerical solution is obtained using an approximate calculation method, specifically an explicit finite difference approach, with initial conditions set to ω0 = 0 and φ0 = 0. This method allows for the computation of angular velocities and displacements over discrete time intervals, providing insight into the system’s dynamic behavior. The results demonstrate the importance of damping and nonlinear dynamics in regulating oscillations, offering a framework for understanding the stability and response of oscillating conveyor mechanisms. The model’s sensitivity to initial conditions and the role of numerical stability are discussed, with suggestions for future work to improve accuracy and applicability in real-world systems.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Geometric and Trigonometric Constraints

- -

- Semi-major axis (horizontal extent);

- -

- Semi-minor axis b (vertical extent);

- -

- Offset determined by and , which place the ellipse at a specific location in the coordinate system.

2.2. Differential Equations of Motion of the Joints of an Oscillating Conveyor Mechanism

2.3. Solving the Differential Equation of an Oscillating Conveyor Mechanism Using the Approximate Calculation Method

3. Methodology

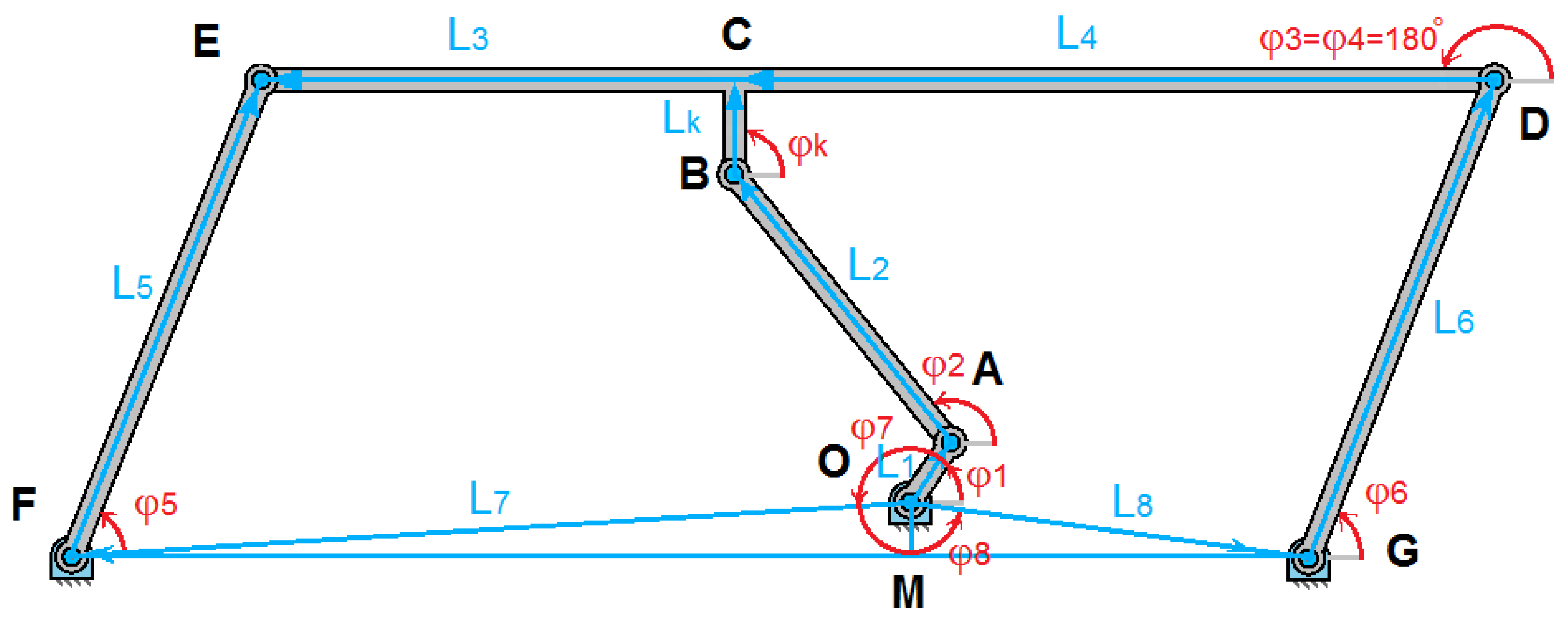

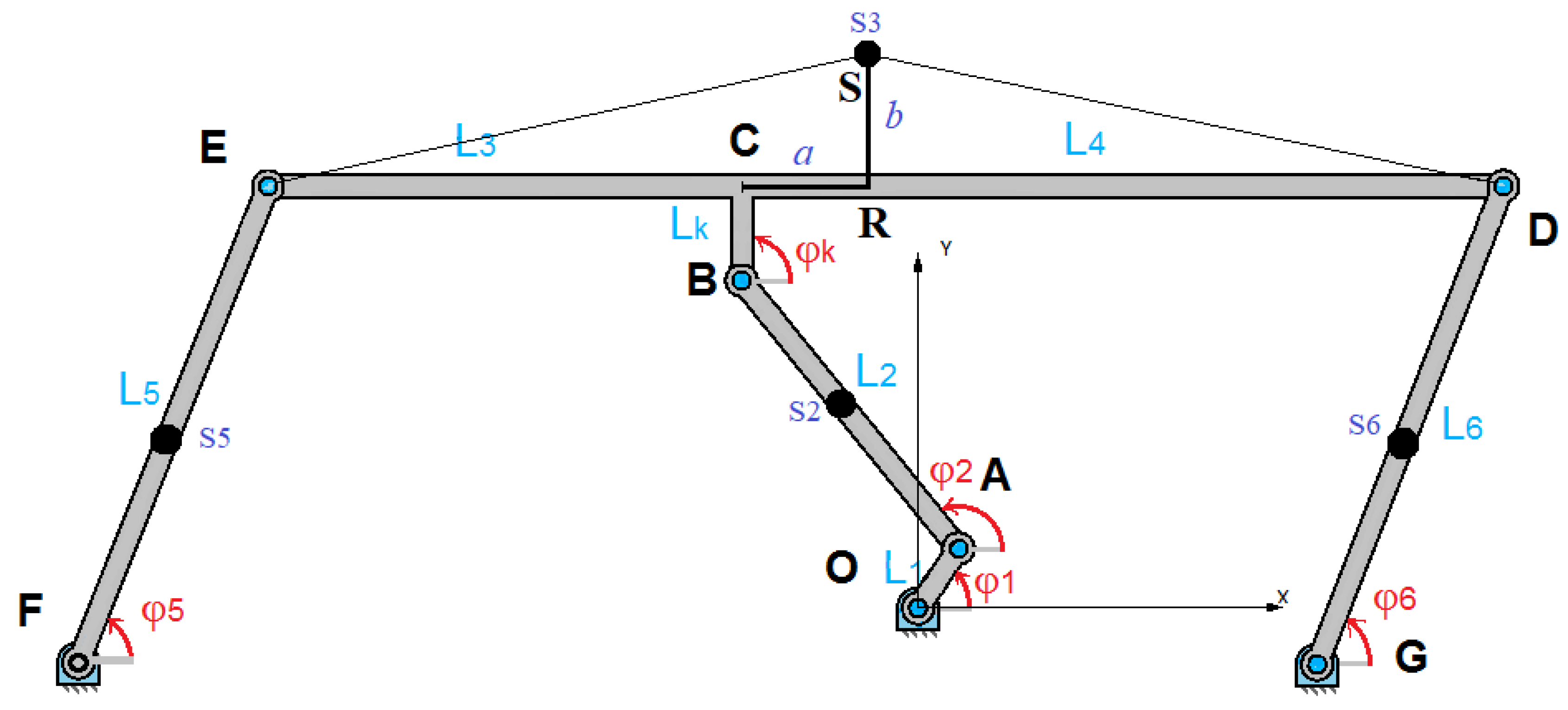

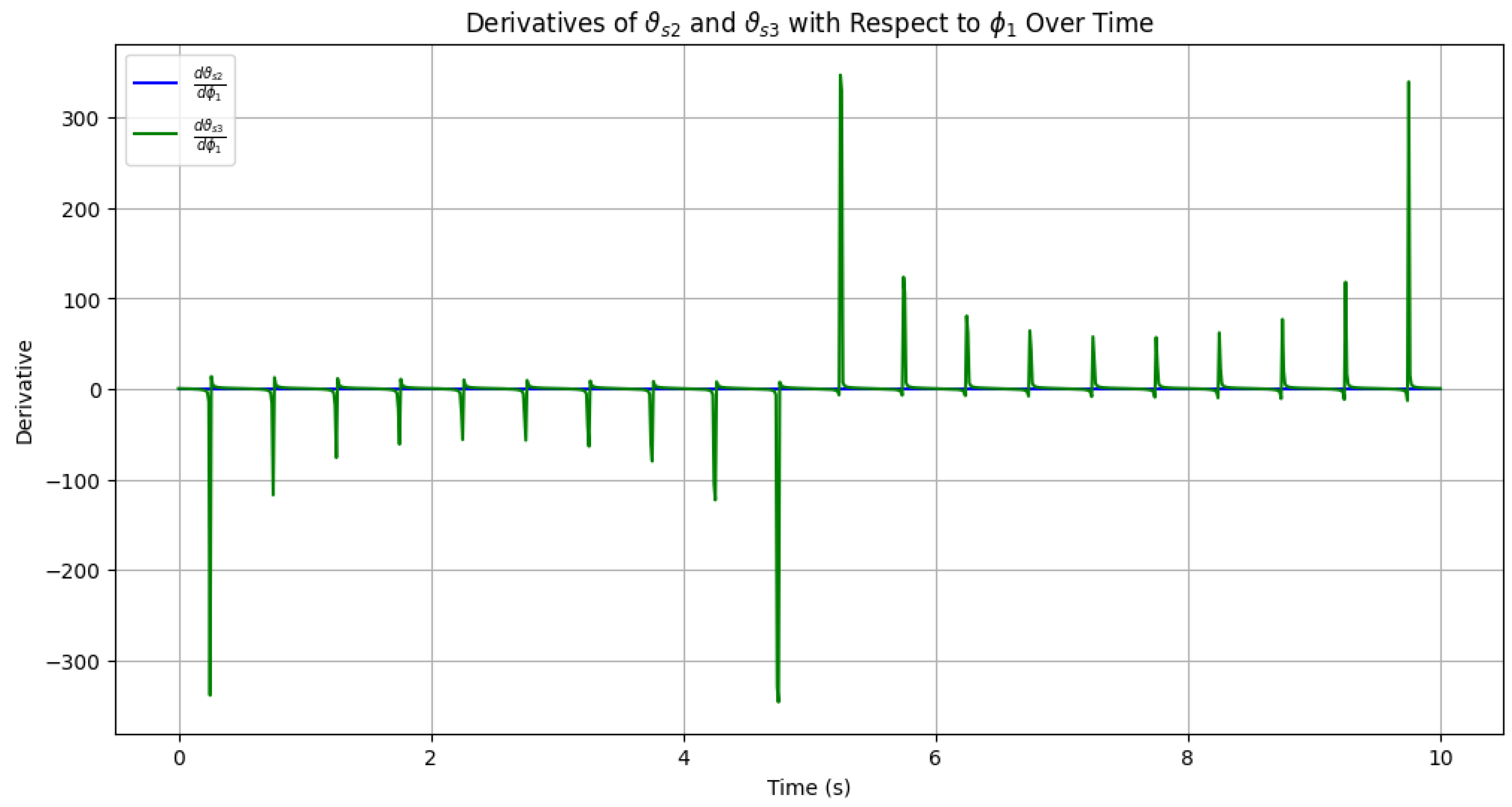

- Kinematic analysis. The kinematic analysis focused on describing the motion of the system’s components without considering the forces or torques causing the motion: a) System modeling - the conveyor mechanism was modeled as a system of interconnected rigid links with specified lengths (, ,…) and joints. Angular displacements () were used to describe the positions of the links relative to reference points. b) Geometric and trigonometric relationships - constraints between the links were expressed as equations involving sines and cosines of the angular variables. Relationships such as were used to ensure consistency in the system’s geometry. c) Velocities and accelerations - the angular velocities and angular accelerations were derived using time differentiation of the position equations. The motion constraints were used to compute velocities and accelerations for all components. d) Visualization - 3D plots of angular displacement, velocity, and acceleration were generated to illustrate the motion behavior over time.

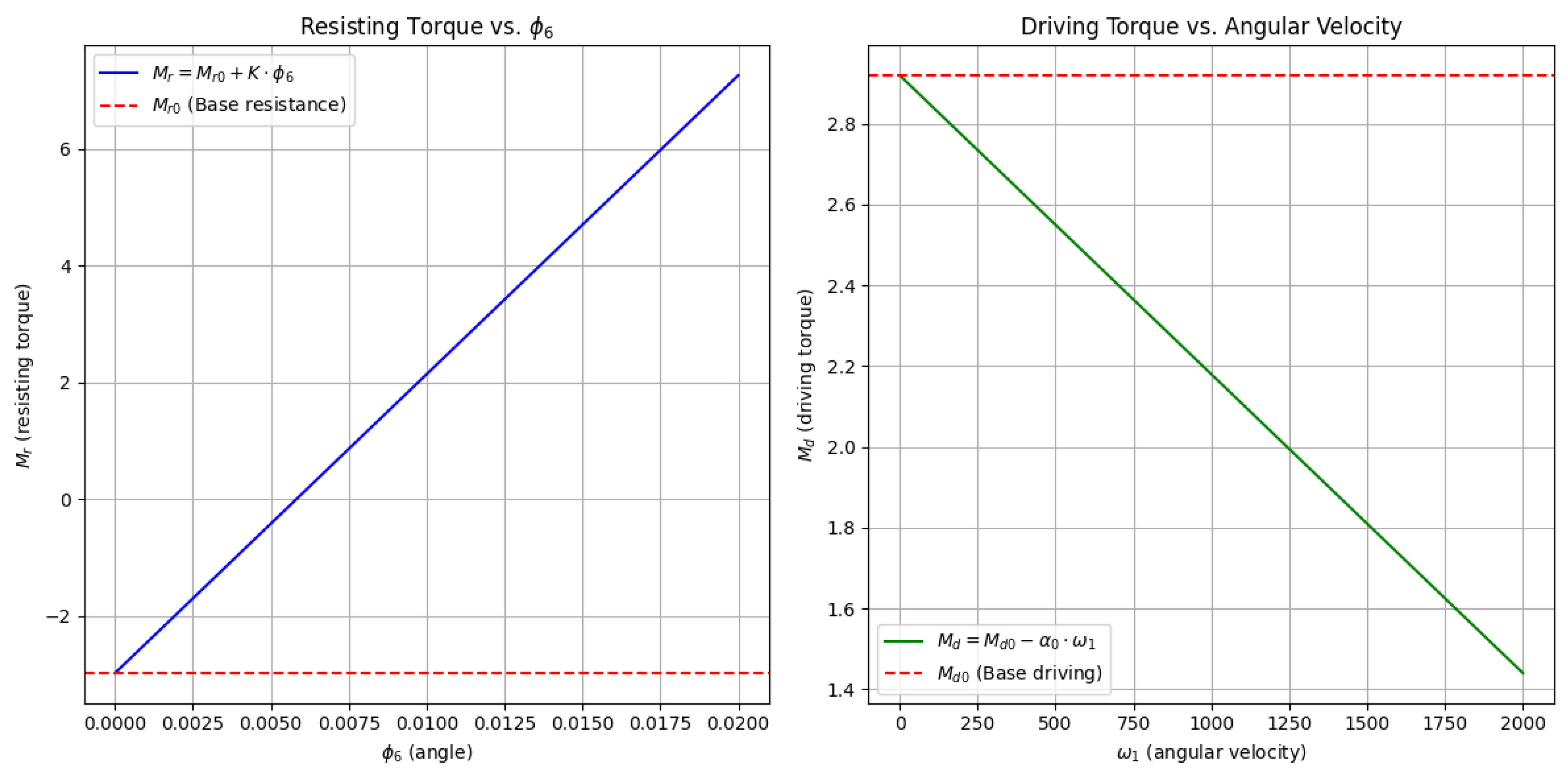

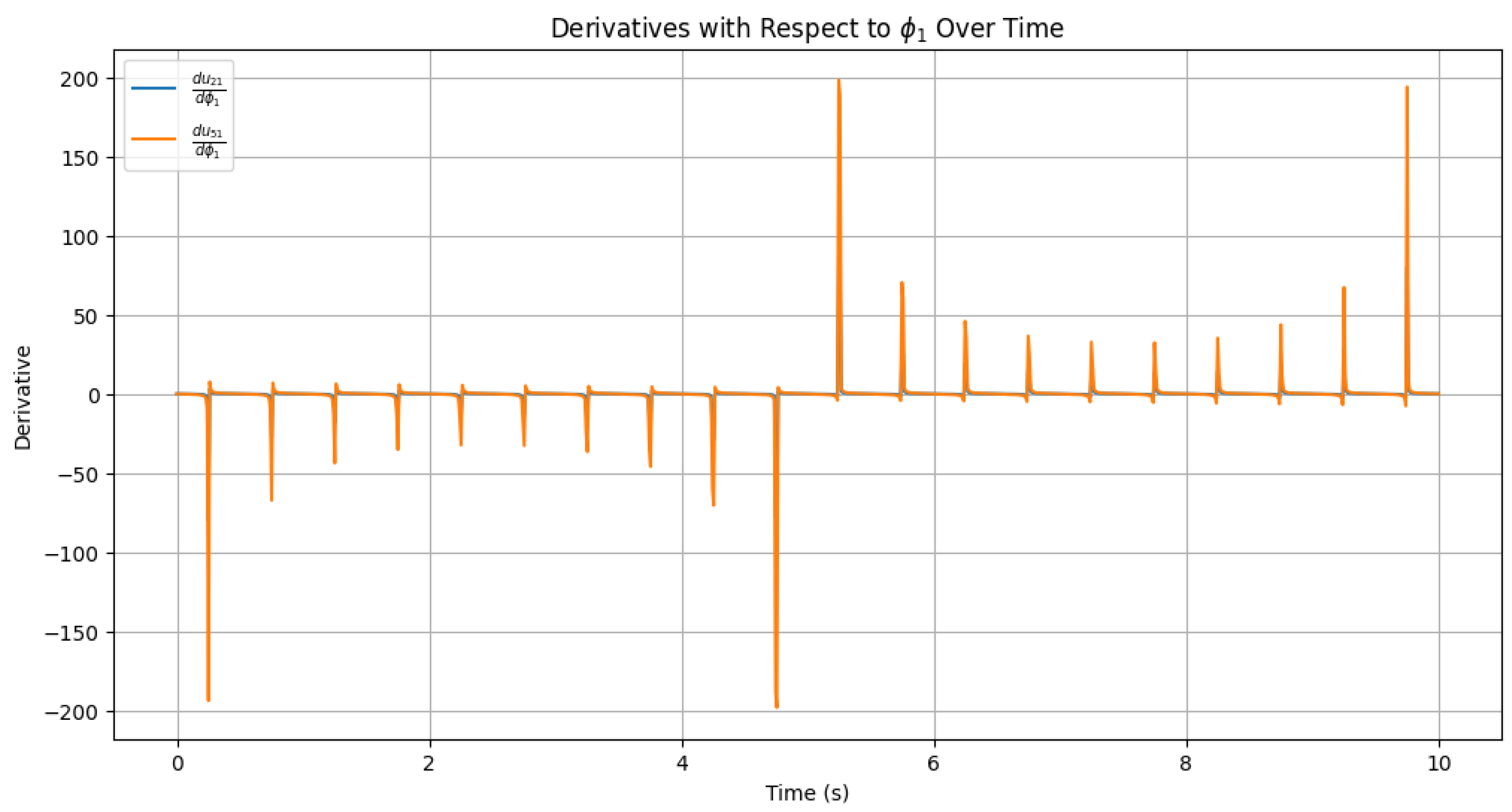

- Dynamic analysis. The dynamic analysis incorporated the forces and torques acting on the system to evaluate its response under load. a) Derivation of equations of motion - Newton’s Second Law and the principle of virtual work were applied to derive equations governing the system’s dynamics. Inertia terms were computed using the mass distribution and geometry of the system. b) Force and torque calculations - driving torques and resisting torques were modeled as functions of angular velocity and angular displacement . External factors, such as damping and load resistance, were incorporated into the dynamic equations. c) Nonlinear effects - nonlinear terms, such as those involving products of angular velocities and displacements, were explicitly included to account for real-world interactions. d) System stability - stability conditions were analyzed by evaluating the balance of forces and torques during operation. Parameters like stiffness K and base moments were studied to ensure system stability.

- Numerical approximation. The numerical approximation was used to solve the nonlinear differential equations derived in the dynamic analysis. a) Differential equation formulation - the equations were expressed in the standard form:where , and are time-dependent coefficients. b) Discretization - Euler’s method was employed to approximate the derivatives using finite time steps h:angular displacement was updated iteratively:

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gurskyi, V.; Korendiy, V.; Krot, P.; Dyshev, O. Determination of kinematic and dynamic characteristics of a reversible vibratory conveyor with an electromagnetic drive. Vibroengineering Procedia 2024, 55, 138-144. [CrossRef]

- Korendiy, V.; Kachur, O.; Dmyterko, P. Kinematic analysis of an oscillatory system of a shaking conveyor-separator. Advanced Manufacturing Processes III 2022, 592-601. [CrossRef]

- Gurskyi, V.; Korendiy, V.; Krot, P.; Zimroz, R.; Kachur, O.; Maherus, N. On the dynamics of an enhanced coaxial inertial exciter for vibratory machines. Machines 2023, 11, 97. [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.P. Construction, working and maintenance of electric vibrators and vibrating screens. Available online: https://practicalmaintenance.net/wp-content/uploads/Construction-Working-and-Maintenance-of-Vibrators-and-Vibrating-Screens.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- Cieplok, G.; Wójcik, K. Conditions for self-synchronization of inertial vibrators of vibratory conveyors in general motion. J. Theor. Appl. Mech. 2020, 58, 513–524. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.X.; Nguyen, K.L.; Dinh, G.N. Study of the dynamics and analysis of the effect of the position of the vibration motor to the oscillation of vibrating screen. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1384, 012035. [CrossRef]

- Nazarenko, I.; Gaidaichuk, V.; Dedov, O.; Diachenko, O. Investigation of vibration machine movement with a multimode oscillation spectrum. East.-Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 2017, 6, 28–36. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Tong, X.; Li, Z. Numerical investigation on the sieving performance of elliptical vibrating screen. Processes 2020, 8, 1151. [CrossRef]

- Gursky, V.; Krot, P.; Korendiy, V.; Zimroz, R. Dynamic analysis of an enhanced multi-frequency inertial exciter for industrial vibrating machines. Machines 2022, 10, 130. [CrossRef]

- Gursky, V.; Kuzio, I.; Krot, P.; Zimroz, R. Energy-saving inertial drive for dual-frequency excitation of vibrating machines. Energies 2021, 14, 71. [CrossRef]

- Yaroshevich, N.; Puts, V.; Yaroshevich, Т.; Herasymchuk, O. Slow oscillations in systems with inertial vibration exciters. Vibroengineering Procedia 2020, 32, 20–25. [CrossRef]

- Yaroshevich, N.; Yaroshevych, O.; Lyshuk, V. Drive dynamics of vibratory machines with inertia excitation. In Vibration Engineering and Technology of Machinery; Balthazar, J.M., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 37–47.

- Chen, B.; Yan, J.; Yin, Z.; Tamma, K. A new study on dynamic adjustment of vibration direction angle for dual-motor-driven vibrating screen. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E J. Process Mech. Eng. 2021, 235, 186–196. [CrossRef]

- Cieplok, G. Verification of the nomogram for amplitude determination of resonance vibrations in the run-down phase of a vibratory machine. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Mechanics 2009, 47, 2, 295-306.

- Michalczyk, J.; Cieplok, G. Disturbances in self-synchronisation of vibrators in vibratory machines. Archives of Mining Sciences 2014, 59, 1, 225-237. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Zhao, Q.; Gong, Z.; Wen, B. Synchronization of two self-synchronous vibrating machines on an isolation frame. Shock and Vibration 2011, 55, 1-2, 73-90.

- Zhauyt, A. The substantiating of the dynamic parameters of the shaking conveyor mechanism. Vibroengineering Procedia 2015, 5, 15-20.

- Wyk, J., Snyman, A., Heyns, S. Optimization of a vibratory conveyor for reduced support reaction force. N&O Journal 1994, 1(10), 12-17.

- Andrea, V.; Nicolae, U.; Loana, M. Contribution to the optimization of relative motion on a vibrating conveyor. ACTA Technica Napocensis 2012, 2(55), 519-522.

- Chu, Yiqing; Li, Cuiying. Helical vibratory conveyors for bulk materials. Bulk Solid Handling 1987, 1(7), 103-112.

- Sloot, E.M.; N.P. Kruyt, N.P. Theoretical and experimental study of the conveyance of granular materials by inclined vibratory conveyors. Powder Technology 1996, 87(3), 203-210.

- Despotovic, Z.; Stojiljkovic, Z. A realization AC/DC transistor power converter for driving electromagnetic vibratory conveyors. Proc. of the V Symp. of Indu. Elec. INDEL, Banja Luka, 11-13.IX.2004, T2A, 34-40.

- Despotovic, Z.; Stojiljkovic, Z. Power converter control circuits for two-mass vibratory conveying system with electromagnetic drive: simulations and experimental results. IEEE Transation on Industrial Electronics 2007, 54(I), 453-466. [CrossRef]

- Winkler, G. Analysing the vibrating conveyor. International Journal of Mechanics 1978, 20, 561-570.

| Step | Description |

| Inputs | Inputs: , , N, h |

| Increment n | Set n: = n+1 |

| Compute A(tn) | Compute A(tn) |

| Compute B(tn) | Compute B(tn) |

| Compute D(tn) | Compute D(tn) |

| Compute E(tn) | Compute E(tn) |

| Compute F(tn) | Compute F(tn) |

| Compute H(tn) | Compute H(tn) |

| Compute N(tn) | Compute N(tn) |

| Compute M(tn) | Compute M(tn) |

| Compute Q(tn) | Compute Q(tn) |

| Compute R(tn) | Compute R(tn) |

| Compute W(tn) | Compute W(tn) |

| Update | =(Wn/Rn-Qn/Rn) |

| Update | =+ h |

| Check if n < N | Check if n < N |

| Yes: Update and Repeat | If ‘Yes’, Update , and Repeat |

| No: Output , | If ‘No’, Output final , |

| End | End of process |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).