Introduction

In 1911, E. Rutherford proposed the "planetary model" of atomic structure, which suggested that electrons orbit the nucleus in the same way as planets orbit the sun1. In 1913, Niers Bohr introduced the quantization hypothesis based on Rutherford's "planetary model" and proposed the Bohr model of hydrogen atomic structure2. This model has achieved great success in explaining hydrogen atom spectra, but it is only applicable to hydrogen atoms and hydrogen like atoms, and cannot provide accurate explanations for more complex atomic structures. In 1916, Arnold Sommerfeld introduced the concept of elliptical orbits based on the Bohr model, making electron motion trajectories more realistic3. Sommerfeld's elliptical orbit theory can accurately calculate the energy levels of hydrogen atoms, highly consistent with experimental results, and successfully explain the fine structure in hydrogen atom spectra. Although Sommerfeld's theory presents difficulties in dealing with multi electron atoms, it can still provide predictions that are consistent with experimental results in certain specific situations. This fully demonstrates that Bohr and Sommerfeld's atomic structure models are quite close to physical reality.

However, Bohr and Sommerfeld's theories contain concepts such as quantization assumptions or conditions that cannot be explained by classical physics, resulting in their theories being in a semi classical and semi quantum state, which leads to contradictions and incompleteness in explaining microscopic phenomena. To address this contradiction and incompleteness, one approach is to explain quantized phenomena using the principles of classical physics; another is to abandon the continuity theory of classical physics and establish a purely quantum mechanical theory. Max Planck, the founder of quantum mechanics, dedicated his entire life to explaining quantum phenomena using the continuity theory of classical physics, yet failed to achieve his goal. Instead, modern quantum mechanics, which rejects the continuity and determinism of classical mechanics, was quickly established. Quantum mechanics is considered a tremendous success in explaining atomic structure, as it can accurately predict and explain various experimental phenomena, such as atomic spectra and the fine structure of atomic energy levels. Consequently, Sommerfeld's theory was soon replaced by quantum mechanics and never continued to be refined and developed further.

Although the mathematical framework of quantum mechanics seems to demonstrate extremely high precision and accuracy in predicting and describing phenomena in the microscopic world, we often find ourselves in a dilemma when attempting to explain these complex phenomena using everyday language and common sense of classical physics. The interpretation of quantum mechanics has been a subject of extensive controversy and deep disagreements within the physics community. The popularity of the phrase "Shut up, and calculate!" 4 in the quantum mechanics community fully reflects the profound confusion and difficulties encountered in interpreting quantum mechanics. This may suggest that the quantum mechanics theory centered on the Schrödinger equation is primarily a mathematical model rather than a purely physical one. Recently, our research has revealed that the diffraction-like and interference-like mechanisms of particle flows fundamentally refute the concept of wave-particle duality and De Broglie's hypothesis of matter waves, implying that the physical foundation upon which the Schrödinger equation is built does not hold5. This represents a revolutionary upset to quantum mechanics. Currently, there are numerous theories based on quantum mechanics for atomic and molecular structures, such as Valence Bond (VB) theory6,7, Hybrid Orbital theory8,9, Molecular Orbital (MO) theory10,11, crystal field theory12, and coordination field theory13,14. While these theories appear prosperous on the surface, each has its own defects and shortcomings. Some theories even contradict one another, highlighting the imperfections of the current theoretical system and the lack of a unified theory for atomic and molecular structures. This means that the strategy of abandoning the continuity theory of classical physics to establish a purely quantum mechanics theory has ultimately proven unviable. Perhaps, we should revisit Planck's concept of energy quanta proposed in 1900, using classical physical principles to explain quantum phenomena and explore the correct path forward.

Recently, we have revised Planck's concept of energy quanta and the theory of radiation energy from accelerated motion of electrons15,16. Based on classical physics principles, we have elucidated the physical mechanism of electron transitions and successfully derived and explained Bohr and Sommerfeld's atomic structure models. Our research shows that the motion of electrons outside the atomic nucleus is either a periodic circular (or elliptical) motion around the nucleus (steady state), or an accelerating or decelerating spiral motion (electron transition between steady states), all of which are continuous motions and do not have any discontinuity, discontinuity, jumping or uncertainty. The viewpoint on the intermittency, jumping, and uncertainty of electronic motion stems from the lack of a physical mechanism that can properly explain the phenomena of electronic transitions, orbital energy levels, orbital radii, and angular momentum quantization. We have successfully explained the quantization phenomena of hydrogen atoms and hydrogen-like atoms within the framework of classical physics, marking a fundamental solution to the semi-classical and semi-quantum problems in Bohr and Sommerfeld's theory. The core objective of this article is to construct a unified and comprehensive theory of atomic and molecular structures based entirely on the framework of classical physics.

The concept of dynamic entities and the dynamic entity model of electron orbits

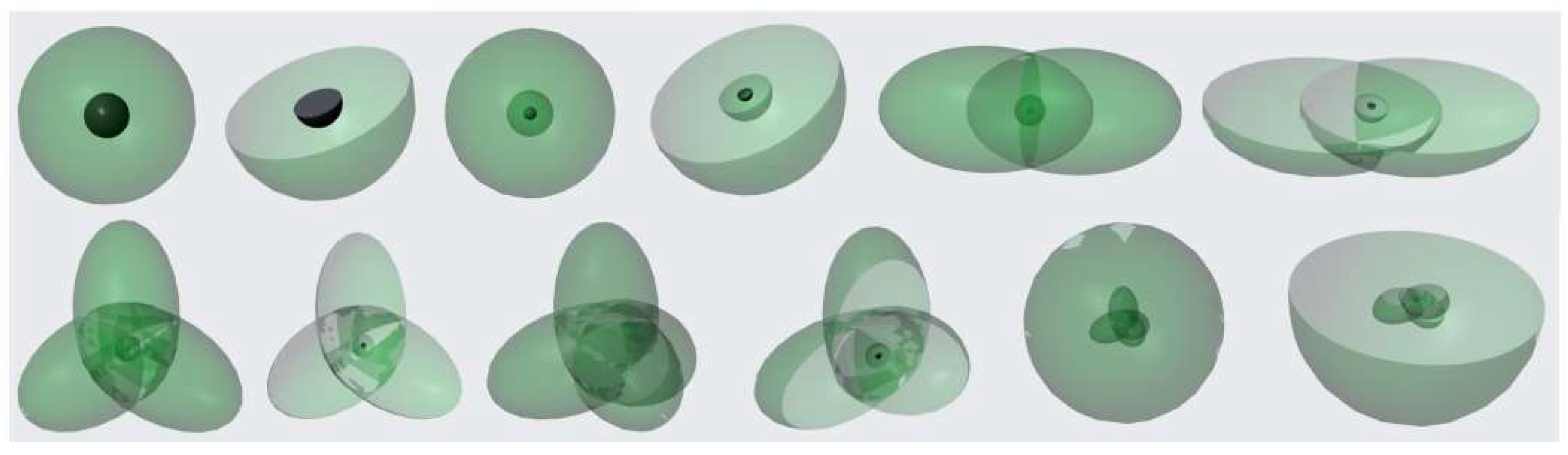

As is well known, material entities often have specific shapes and sizes, occupying a defined space. When an object undergoes high-speed periodic motion, the shape and size of the space enclosed or occupied by its motion trajectory are also determined due to its fixed trajectory. For example, when a fan blade or helicopter propeller rotates at high speed, it appears to form a disk. Generally, when an object undergoes periodic motion, the space enclosed and defined by its motion trajectory is called the "periodic existence space" of the object. The periodic motion of an object includes vibration and rotation. When the periodic motion of an object is a reciprocating vibration, its periodic existence space is a linear structure (cylindrical structure). When the periodic motion of an object is circular or elliptical, its periodic existence space forms a circular ring or elliptical ring. When the circular ring or elliptical ring rotates around the diameter of the circle or the major axis of the ellipse, its periodic existence space becomes a sphere or ellipsoid. Therefore, when an object undergoes rapid periodic motion, its periodic existence space presents a specific shape and size. The dynamic distribution of an object in its periodic spatial existence is a "spatiotemporal whole", which we call a dynamic entity. The periodic existence space of objects can also be referred to as dynamic entity space. Obviously, dynamic entities are a special phenomenon formed by the high-speed periodic motion of objects. It can only be observed within the "time period" of the object's high-speed motion, whereas at a specific "instant" in time, only the moving object itself can be observed. Since the dynamic entity is a time-accumulated phenomenon resulting from the high-speed periodic motion of an object, its physical properties are the overall effects produced by this motion. The faster the periodic motion speed of an object, the shorter the motion period, and the more obvious the overall effect of the dynamic entity.

The circular or elliptical orbital motion of electrons around the nucleus is a typical high-speed periodic motion. The speed of electron movement around the nucleus is extremely fast (approximately v0=2.2×106 m/s for electrons in the ground state of a hydrogen atom), while the radius of the electron orbit is extremely small (r0=0.53×10-10m), and the motion period is extremely short (T0=6.6×10-17s). Therefore, the electron orbit that moves in a circular or elliptical motion around the atomic nucleus can be regarded as a dynamic entity of a circular or elliptical ring. Due to the susceptibility of electrons to electromagnetic fields generated by the motion of other electrons, they will also undergo precession while moving in circular or elliptical orbits around the nucleus. Since the speed of electrons in circular or elliptical motion around the nucleus is much greater than the precession speed, it appears as if the dynamic entity of the electron ring is rotating around its diameter or the dynamic entity of the electron elliptical ring is rotating around its major semi-axis, ultimately forming a spherical or ellipsoidal dynamic entity representing the electron's orbital motion.

Assuming the period of circular or elliptical motion of electrons is T and the precession period is t, the charge passing through per unit time (charge flux) at the vertex of the long semi-axis of a sphere or ellipsoid is e/T, while the charge flux at other locations on the surface of the sphere or ellipsoid is e/(T+t). Obviously, the charge flux per unit area (charge flux density) is highest at the vertex of the sphere or ellipsoid and decreases towards the middle of the sphere or ellipsoid. These characteristics of electronic orbital dynamic entities are of great significance.

Treating electron orbits as dynamic entities of spheres or ellipsoids greatly simplifies research and avoids complex and often unnecessary issues such as delving into the precise spatial position and momentum magnitude of electrons at any given moment. This new research approach allows us to focus more on the overall behavior and dynamic characteristics of electronic orbital dynamic entities, thereby more effectively revealing the essence of electronic motion. The concept of dynamic entities of electron orbits makes our understanding of the motion of electrons outside the atomic nucleus more intuitive and understandable. For example, when electrons absorb light quanta, the radius of their motion around the nucleus gradually increases, which can be understood as the dynamic entity of the electron orbit undergoing "expansion"; When electrons radiate light quanta, the radius of their motion around the nucleus gradually decreases, which can be understood as the dynamic entity of the electron orbit undergoing "contraction". The "expansion" and "contraction" of electronic orbital dynamic entities represent the absorption and radiation of energy, which is very similar to the thermal expansion and contraction phenomena of macroscopic objects.

The concept of dynamic entities is a physical model based on a holistic perspective, which provides us with a new perspective to examine the essence of macroscopic objects. Based on this model, it is easy to find that the periodic movement of high-speed microscopic particles forms dynamic entities, and countless microscopic dynamic entities aggregate to produce macro effects and form macro substances. The concept of dynamic entities builds a bridge connecting the micro and macro worlds, allowing us to gain a deeper understanding of the essence of the material world.

The Basic Physical Image of Atomic Structure

Based on the concept of dynamic entities and our previous research results, the basic physical image of atomic structure has been clearly presented:

Firstly, electrons move rapidly around the atomic nucleus, manifested as the nucleus being enveloped by a dynamic entity of spherical or ellipsoidal electron orbits, with the nucleus located at the center of the sphere or the focal point of the ellipsoid.

Secondly, in a multi electron atomic system, there are multiple electron orbital dynamic entities with the same electron layer outside the atomic nucleus, which inevitably repel each other. According to the principle of minimum energy, in order to minimize the energy of the atomic system, these electron orbital dynamic entities will be evenly and symmetrically distributed in space as much as possible.

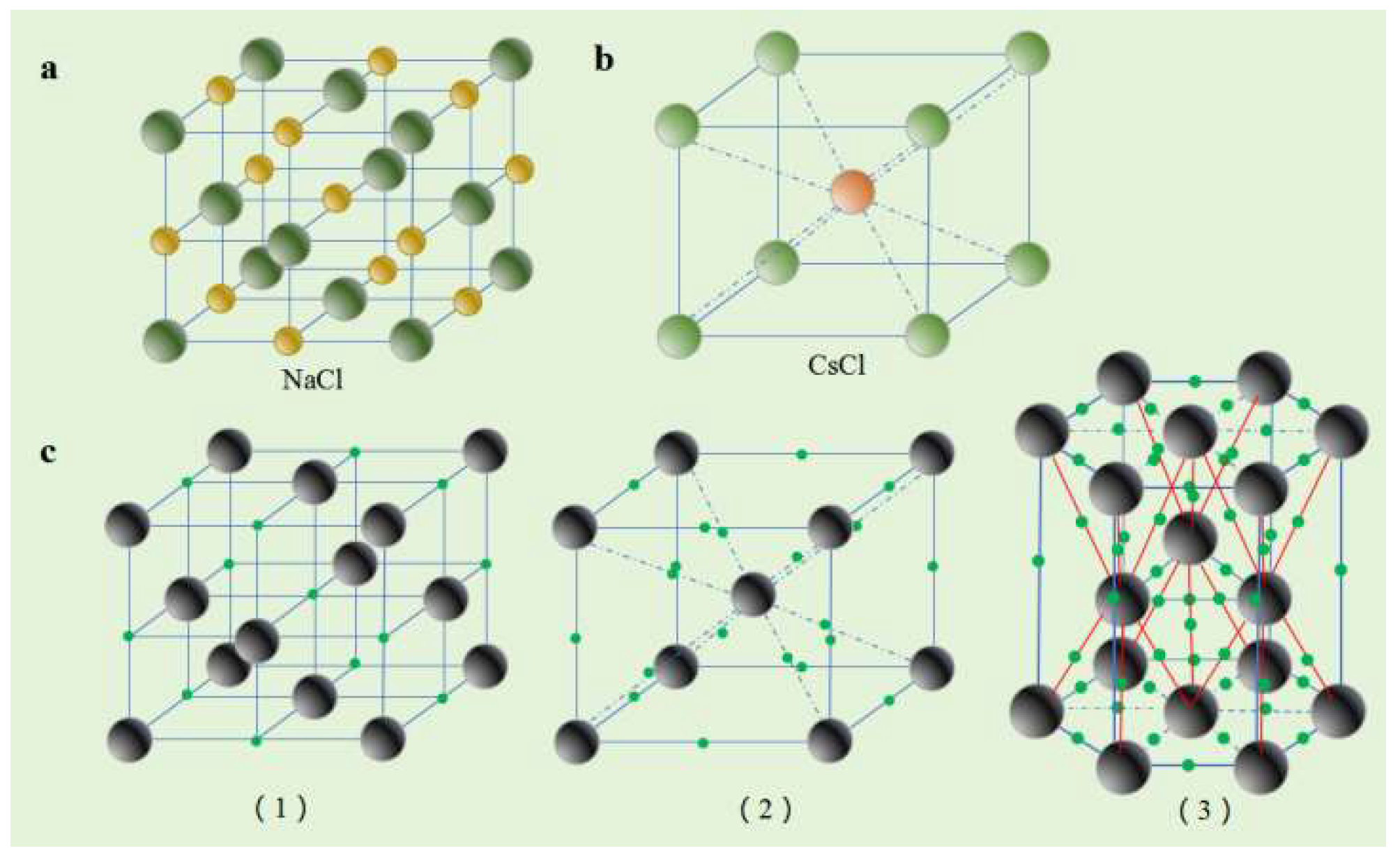

Thirdly, in a multi electron atomic system, the dynamic entity of electron orbits is a layered structure resembling a Russian nesting doll (

Figure 1).

Fourthly, the orbital radius of the first electron layer of element

Z is

r1, and the orbital radius of the nth electron layer is

n2r1. The electron orbital energy level of the first electron layer is

E1, and the electron orbital energy level of the

nth electron layer is

E1/n2.

Dynamic entity images and cross-sectional views of atoms such as H, He, Li, Be, B, C, N, O, F, Ne, Na and Mg.

According to the principle of minimum energy and the distribution law of electron energy levels outside the atomic nucleus, the electron orbital energy level En in the nth electron layer cannot be lower than the electron orbital energy level E1 in the first electron layer (i.e. EnE1). Since the energy levels of electron orbits in the same electron layer are the same, the nth electron layer can accommodate a maximum of n2 electron orbits (n2En=E1) (since the energy levels of electron orbits are negative, if the number of orbits is greater than n2, the energy level of the electron layer must be lower than E1).

Electron Spin and Pairing

In the initial state, free electrons without force do not rotate or spin. When an electron moves around the nucleus, it rotates once as it moves around the nucleus, so the angular velocity of the electron's rotation is equal to the angular velocity of the electron's movement around the nucleus. This is the source of electron spin. The notion that electron spin is not rotation but an intrinsic property of electrons is clearly incorrect. Our latest research suggests that the correct concept of orbital magnetic moment should be the rotating electric quantity evr, the so-called Land factor (correction factor) g, and the spin quantum number 1/2, which are erroneous conclusions based on the current erroneous concept of magnetic moment17.

If an electron can serve as a stationary reference frame, then the interaction between electrons is called charge interaction (electrostatic force, Coulomb force). That is to say, Coulomb force only applies to a relatively stationary reference frame. If both electrons have spin motion, one of the spin electrons cannot be used as a stationary reference frame, so the interaction between the two spin electrons is not electrostatic force, but rather magnetic force generated by electron spin.

Electrons in high-speed spin motion are like small spinning tops. Due to the spin magnetic field generated by the electron's spin motion, the "small top" is actually a "small magnetic needle". When two spin electrons approach each other, they act like two small magnetic needles that automatically flip their magnetic poles and adjust to opposite spin directions, generating magnetic attraction. Two electrons with opposite spin directions rotate around each other under the influence of magnetic attraction, forming an electron pair. This is the physical mechanism of electron spin pairing.

The faster the electron spin speed, the stronger the magnetic field generated, and the farther away from the spin electrons, the lower the magnetic field strength. According to our Existence Field Theory

17, electron spin motion generates a "spin quantity"

, which in turn generates a "spin quantity field". The strength of the spin quantity field is

Among them,

Q is the fundamental physical quantity (charge

e or mass

m),

is the electron spin angular velocity,

r is the radius of the sphere around the electron center, and

k is the spin field constant. The interaction force between two spin quantities is

The spin of charge generates charge spin quantity

, and the spin of mass generates mass spin quantity

. Due to the fact that the interaction between charges is much greater than that between masses, we only consider the charge spin field (spin magnetic field) and its interaction. The strength of the electron spin magnetic field is:

Among them,

ke is the spin magnetic field constant. The magnitude of the spin magnetic field interaction force (spin magnetic force) between two spin electrons is

When two electrons with opposite spins rotate around each other in a uniform circular motion under the action of spin magnetic force, the centripetal force is equal to the spin magnetic force

F, and the circular motion radius is

r/2, then:

The total energy of a single spin electron is:

Assuming two spin electrons are in a uniform circular motion around each other in the ground state orbit, with an energy of

E'0, an orbital radius of

r'0/2, and a nuclear frequency of

f'0. After absorbing energy Δ

E within Δ

t time, electrons continuously increase their orbital radius and decrease their velocity. When the energy reaches its maximum value

E'n=0, its velocity is zero and its operating frequency

f'n=0. That is to say, when the electron reaches its maximum orbital, it is released from the spin magnetic force and the electron pair will separate. According to our previous research

15,16, we can conclude that:

When

=1s,

=

h, then

We can imagine that spin electrons absorb light quanta within Δ

t time and then transition to higher energy levels

or from higher energy levels to lower energy levels

, releasing light quanta within Δ

t time:

According to the electronic transition power

, let

=1s,

=

h, we can obtain:

Among them,

is the Rydberg constant. Let

be the Rydberg constant of the electron spin pairing system. Then

Due to the atomic spectral structure conforming to the Rydberg formula, it can be obtained from equation (16)

By substituting into equation (8), we can obtain

From equation (9), we can get

The angular momentum of spin electrons rotating around each other can be obtained by substituting the ground state orbital velocity

v'0 and orbital radius

r'0/2:

According to equation (17), the same goes for:

It can be seen that two electrons with opposite spins rotate around each other under the action of spin magnetic force, just like the motion of electrons around the nucleus. Their energy levels, orbital radii, angular momentum, etc. are quantized, and the absorbed and radiated light quantum frequencies constitute the fine structure of atomic spectra. Based on the experimental data of the fine structure of atomic spectra, the corrected Rydberg constant R' can be calculated to determine the charge spin field constant .

Due to the decrease in potential energy caused by spin magnetism between spin electrons, according to the principle of minimum energy, electrons outside the atomic nucleus will undergo spin pairing as much as possible to reduce the potential energy of the atomic system. Based on this, it can also be inferred that, except for the outermost electron layer, the inner electron orbits must be paired double electron orbits, and the number of inner electrons must be even. In addition, based on the ground state orbital energy E'0 of spin electrons rotating around each other, the electron pairing energy can be determined to be 2E'0.

Space Configuration of Electron Orbits

Due to the mutual cancellation of magnetic moments between two electrons with opposite spin directions, the spin paired double electron orbits mainly exhibit charge characteristics. Therefore, there is only electrostatic repulsion between the third electron and the double electron orbits, and no spin magnetic force. It can be seen that there is electrostatic repulsion between double electron orbits or between double electron orbits and single electron orbits. Under the action of electrostatic repulsion, the electronic orbits will reach a balance of interaction forces, and their spatial distribution will eventually be in a uniform and symmetrical equilibrium state. This uniform symmetrical distribution state minimizes the energy of the entire atomic system.

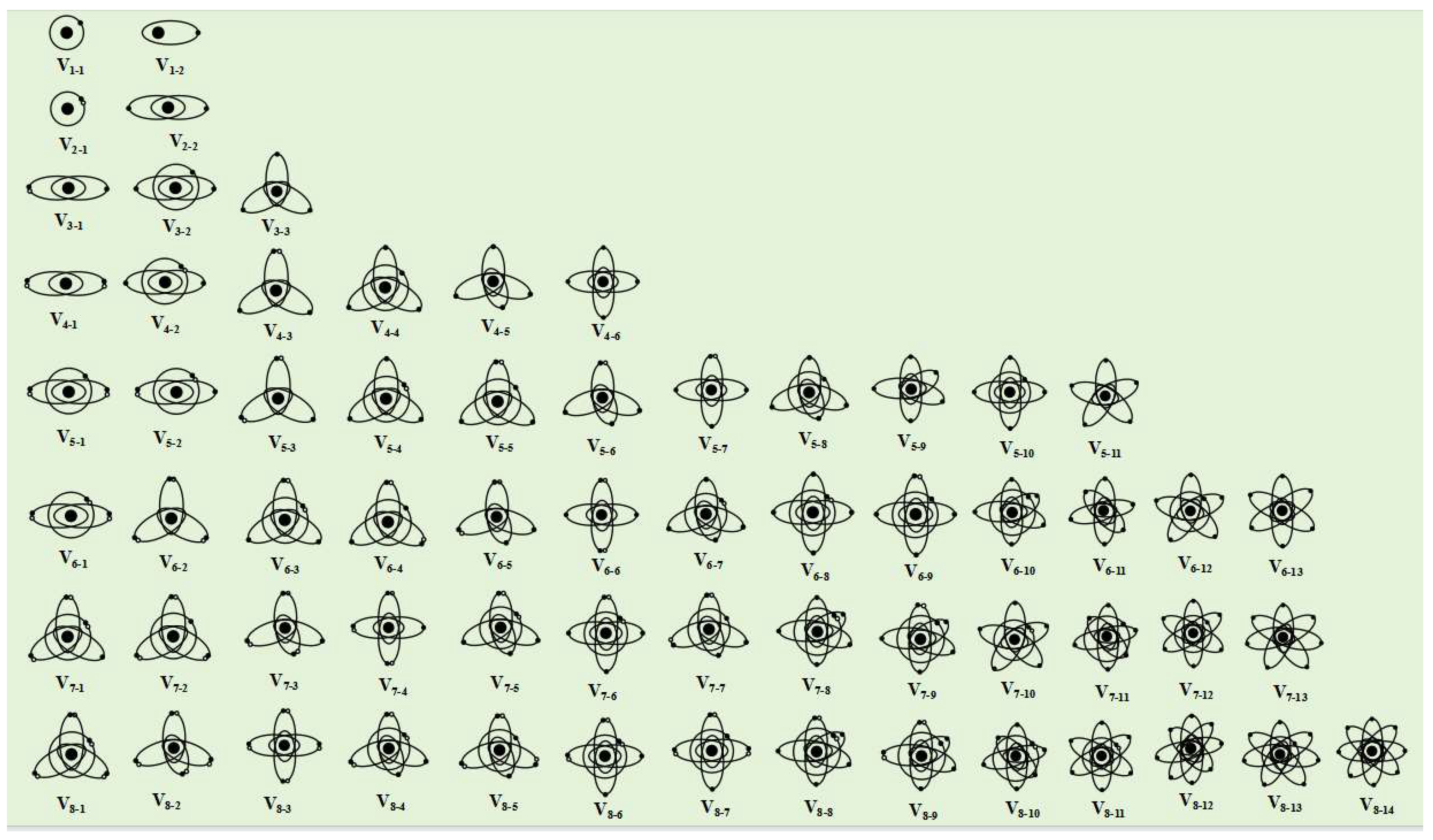

The electronic orbital space configuration (abbreviated as "electronic configuration") is represented by Vn-m, where n is the number of electrons and m is the electronic configuration number. The larger the number of electrons n and the electronic configuration number m, the higher the potential energy of the electronic configuration.

1) 1 electronic

If there is only one electron in the outermost electron layer, it is obvious that there is only one electron orbital. The electronic orbit will adopt a uniformly symmetrical spherical or ellipsoidal orbital configuration. The electronic orbital configuration with only one electron on the electronic layer is represented by V1, the spherical orbital configuration is represented by V1-1, and the ellipsoidal orbital configuration is represented by V1-2.

2) 2 electronics

If there are two electrons in the outermost electron layer, it is easy to form electron spin pairing in the spin magnetic field, thereby reducing the orbital potential energy. Therefore, when the atom is in the ground state, the electron orbit is one spherical orbit or one ellipsoidal orbit, and the electron configurations are represented by V2-1 and V2-2, respectively. When an atom is in an excited state, electrons transition to higher energy levels, and the spin magnetic force is less than the electrostatic repulsion. Two spin paired electrons will separate, forming two linearly symmetrical ellipsoidal electronic configurations, represented by V2-3.

3) 3 electronics

Due to the lowest energy of the system when atoms are in the ground state, electrons in the electron orbits are spin paired as much as possible, and the spatial distribution of electron orbits is as uniform and symmetrical as possible. Therefore, three electrons in the outermost electron layer will form one spin paired ellipsoidal double electron orbit and one ellipsoidal single electron orbit, which will adopt a linear symmetric distribution configuration (V3-1). If the atom is in an excited state, two spin paired electrons will separate, and three electrons will form three single electron orbits, which can form one spherical orbital and two linearly symmetric ellipsoidal orbits (V3-2), or three coplanar ellipsoidal orbits with equal angles (120 degrees) between each pair of orbits in a uniform symmetric configuration (V3-3).

4) 4 electrons

When an atom is in the ground state, the outermost four electrons can form two ellipsoidal spin paired electron orbits, adopting a linear symmetric distribution configuration (V4-1). When the atom is in an excited state, the electronic configuration of the outermost electron layer varies depending on the energy of the excited state. When the energy of the excited state can only separate one electron pair, a spherical double electron orbital and two linearly symmetric ellipsoidal single electron orbital configurations (V4-2) will be formed. When the energy of the excited state is more than enough to separate one electron pair but not enough to separate two electron pairs, three ellipsoidal electron orbits with uniform symmetry (V4-3) will be formed (the angle between the electron orbits is equal to 120 degrees), including one double electron orbital and two single electron orbits. However, due to the higher charge of the double electron orbital compared to the single electron orbital, it will exert a squeezing effect on the two single electron orbits, reducing their angle (less than 120 degrees). When the energy of the excited state is sufficient to separate two electron pairs, four single electron orbits will be formed. According to the magnitude of the excitation energy, four single electron orbits will form one spherical orbital and three ellipsoidal orbital configurations (V4-4) that are coplanar and have an orbital angle of 120 degrees, or four tetrahedral structures with equal orbital angles (109.47 degrees) (V4-5), or two linearly symmetric ellipsoidal orbital configurations that are perpendicular to each other (V4-6).

Figure 2 shows the electronic configuration of the outer nuclear electron layer with 1-8 electrons.

The electronic orbital spatial configuration is a reflection of the energy state of an atomic system. When an atom is in the ground state, the energy of the atomic system is at its lowest, electrons in the electron layer are spin paired as much as possible, the number of electron orbits in the valence layer is minimized, and the electron configuration is distributed as evenly and symmetrically as possible. When an atom is in an excited state, the energy of electrons outside the nucleus increases, causing the spin paired double electron orbits to split into two single electron orbits and increasing the number of valence electron orbits. As the number of electron orbits increases, the repulsive potential energy increases, and the spatial configuration of electron orbits changes from a low-energy configuration to a high-energy configuration. The changes in electron spin pairing energy levels and the transitions between different electron configurations are manifested in spectroscopy as fine and ultrafine structures of spectral lines.

Calculation of Atomic System Energy, Ionization Energy, and Electron Affinity Energy

From equation (2) and

En=

E1/n2, we can obtain the orbital energy levels of each electron layer of any atom. However, for multi electron atomic systems, the complex interactions between electrons make the calculation of the orbital energy levels of each electron layer more complicated. People usually use Slater's formula to calculate the energy of the electron layer

9:

Among them, Z * is the effective nuclear charge number, σ is the shielding coefficient, and eV.

The so-called shielding effect refers to the shielding effect of inner layer electrons on outer layer electrons, for example, when the inner layer electrons are close to the atomic nucleus, they will cancel out the positive charge of the atomic nucleus. However, Slater's "shielding coefficient" σ not only includes the shielding effect of inner layer electrons, but also the interaction between electrons in the same electron layer. Obviously, this coefficient does not fully conform to the concept of shielding effect. In order to fully comply with the concept of shielding effect, we stipulate that the shielding coefficient σ only corresponds to the shielding effect of inner layer electrons on outer layer electrons, and no longer includes the interaction between electrons in the same electron layer. The interaction between electrons in the same electronic layer includes two aspects: one is the mutual repulsion between electron orbits, and the other is the mutual attraction between electrons with opposite spin directions. These interactions collectively shape the spatial configuration of electron orbits. Therefore, the electronic orbital energy level of the electronic layer should be composed of two parts, one is the electronic orbital energy level affected by the shielding effect, and the other is the electronic orbital spatial configuration potential formed by the interaction of electrons in the same electronic layer. The electronic orbital spatial configuration potential includes two parts: the electron orbital repulsion energy and the electron pairing energy.

Assuming that atom A of element

Z has

n electron layers, the

nth electron layer has

m electrons, and the electron pairing number is

(

m/2). The orbital energy level of the

nth electron layer of the ground state A atom is given by equation (22), the electronic spatial configuration potential energy of the

nth electron layer is

, the electron orbital repulsion energy is

, and the electron pairing energy is

. The total energy of the nth electron layer of atom A is:

The total energy of atomic system A is

The average energy of each electron in the outermost electron layer (nth electron layer) is

. Therefore, the first ionization energy of atom A is

When losing

k (

) electrons to form an

A+k ion, the average energy of each electron in the outermost electron layer is

The

kth ionization energy is

The

m-th ionization energy is

The electron shielding coefficient

σ within the nth electron layer is calculated using equation (29):

The energy of the first electron layer of atom A with atomic number

Z greater than 2 is

Due to the completely uniform and symmetrical spatial configuration of a single spherical electron orbit, the electron orbit repulsion energy

. The average energy of each electron is

. According to the experimental data of ionization energy

I(Z-1), the electron pairing energy of the first electron layer can be obtained as follows:

When an atom has only one electron left, the shielding coefficient , so the Z-th ionization energy is .

As long as we obtain experimental data on the ionization energy of atoms, we can analyze the shielding coefficient of electrons in the outer and inner layers of the atomic nucleus, the potential energy of electron configurations in each layer, including the electron orbital repulsion energy and electron pairing energy, and obtain a clear understanding of the atomic structure. On the contrary, if theoretical parameters such as the shielding coefficient of electrons in the outer and inner layers of the atomic nucleus, the potential energy of electron configuration in the electron layer, etc. can be mastered, the ionization energy of atoms can also be predicted.

Based on the energy state of the atomic system, we can also calculate the electron affinity of elements. Assuming that atom A obtains an electron and becomes an A

-1 ion, the energy of the nth electron layer is

Then, the first electron affinity is

Atomic Spectrum

When the excited state of an atom only causes a change in the electronic configuration of the atomic valence layer:

The outermost electron number of atom A is

m, the valence layer electron configuration is V

m-i, and the ground state electron configuration is V

m-i. When the atom absorbs energy and enters the excited state, its valence layer electron configuration changes from V

m-i to V

m-j. The energy level transitions from

EVm-i (A) to

EVm-j (A). The energy level difference is

The corresponding spectral frequency is

When the excitation of an atom causes a change in the radius and energy level (principal quantum number) of the electron orbit:

The total energy of the

nth electron layer of atom A is

The valence layer electronic configuration energy of the nth electron layer is

, and the ground state valence layer electronic configuration energy is

The energy level of the valence layer electron configuration that transitions to the (

n+1) th electron layer is

, and the corresponding energy level change is

The corresponding spectral frequency is

Electron Arrangement Outside the Atomic Nucleus: Examples and Analysis

Based on the principle of minimum energy and the distribution law of electron energy levels outside the atomic nucleus, it is concluded that each electron shell can accommodate up to n² electron orbits, where n represents the shell number. Furthermore, according to the physical mechanism of electron spin pairing, each electron shell can hold a maximum of 2n² electrons. The electron arrangement of atoms generally follows the principle of minimum energy, starting from the electron shell closest to the atomic nucleus and gradually progressing to higher energy levels. However, the specific number of electrons arranged in each electron shell does not directly correspond to the maximum electron capacity of each shell. As indicated by Equation (22), the energy gap between the first and second electron shells is relatively large, and as the shell number increases, the energy gap between adjacent electron shells diminishes. Therefore, when considering whether electrons should be arranged in the outermost or second outermost shell in higher electron shells, it is necessary to consider the energy of the entire atomic system. The most likely electron configuration is the one that minimizes the total energy of the atomic system.

For example, consider the element K with an atomic number of 19. The first electron layer can accommodate 2 electrons, the second electron layer can accommodate 8 electrons, and theoretically, the third electron layer can accommodate up to 18 electrons. Therefore, it seems that the third electron layer of K element can accommodate 9 electrons. But in reality, only 8 electrons are arranged in the third electron layer, and one electron is arranged in the fourth electron layer. This is because if there are 9 electrons arranged in the third layer, the potential energy of the electronic orbital spatial configuration () will be greater than the total potential energy of the electronic orbital spatial configuration of 8 electrons arranged in the third layer and 1 electron arranged in the fourth layer (). In fact, the arrangement of 8 electrons in the third electron layer is the electron arrangement of the rare gas Ar. The atomic structure with the same arrangement of inner layer electrons as rare gas elements is called atomic core, and its valence electron orbital spatial configuration V8-1 has a perfectly uniform symmetrical structure and is very stable.

The electronic arrangement of transition elements, especially Group VIII elements, Group 1B elements, as well as lanthanide and actinide elements, is often highly controversial. The inner electron layers of these elements are not filled according to the maximum number of electrons that can be accommodated. As the atomic number increases, whether electrons are arranged in the unfilled inner electron layer or the outer electron layer needs to be determined based on the principle of the lowest energy in the atomic system. The increase in the number of inner electrons will increase the number of electron orbits, thereby enhancing the spatial configuration potential energy of electron orbits. Meanwhile, considering that electron spin pairing can reduce the potential energy of the system, the inner electron layer will be a spin paired double electron orbit. Therefore, as the atomic number increases, electrons will alternate between the inner electron layer or the outermost electron layer to keep the energy of the atomic system at its lowest state, until the inner electron layer forms an inert gas element atomic core structure and reaches a stable state. The electron arrangement of Group 1B elements is quite unique. Although the number of electrons outside the nucleus is sufficient to fill the 18 electrons in the second outer layer, this arrangement has a large potential energy for the electron orbital space configuration, and there is only one unpaired electron remaining in the outermost layer, which has a high energy and is therefore unstable. This type of electron arrangement with a non atomic core structure in the outer layer is unstable. Therefore, the 1B group elements continue the electron filling mode of the VIII group elements, forming a more stable atomic system with a secondary outer layer of 7 electron orbits (14 electrons) and an outermost layer of 5 electrons.

Based on the theory of electronic orbital spatial configuration, we have rearranged the extranuclear electron arrangement of all elements in the periodic table (

Table 1), correcting the electron arrangement errors in the existing atomic orbital theory based on quantum mechanics. In the current electronic arrangement, some atoms exhibit an odd number of electrons in their inner shells, such as elements 39, 57, 58, 59, 65, 67, 69, 73, 75, and 77-89, 91-93, 95-97, 99, 101, and 103-112. Such arrangements contradict the principle of minimum energy because electron spin pairing reduces the potential energy of the atomic system, implying that the number of electrons in the inner shells must be even. Only after the inner shell electrons are spin-paired can unpaired electrons occupy the outermost shell.

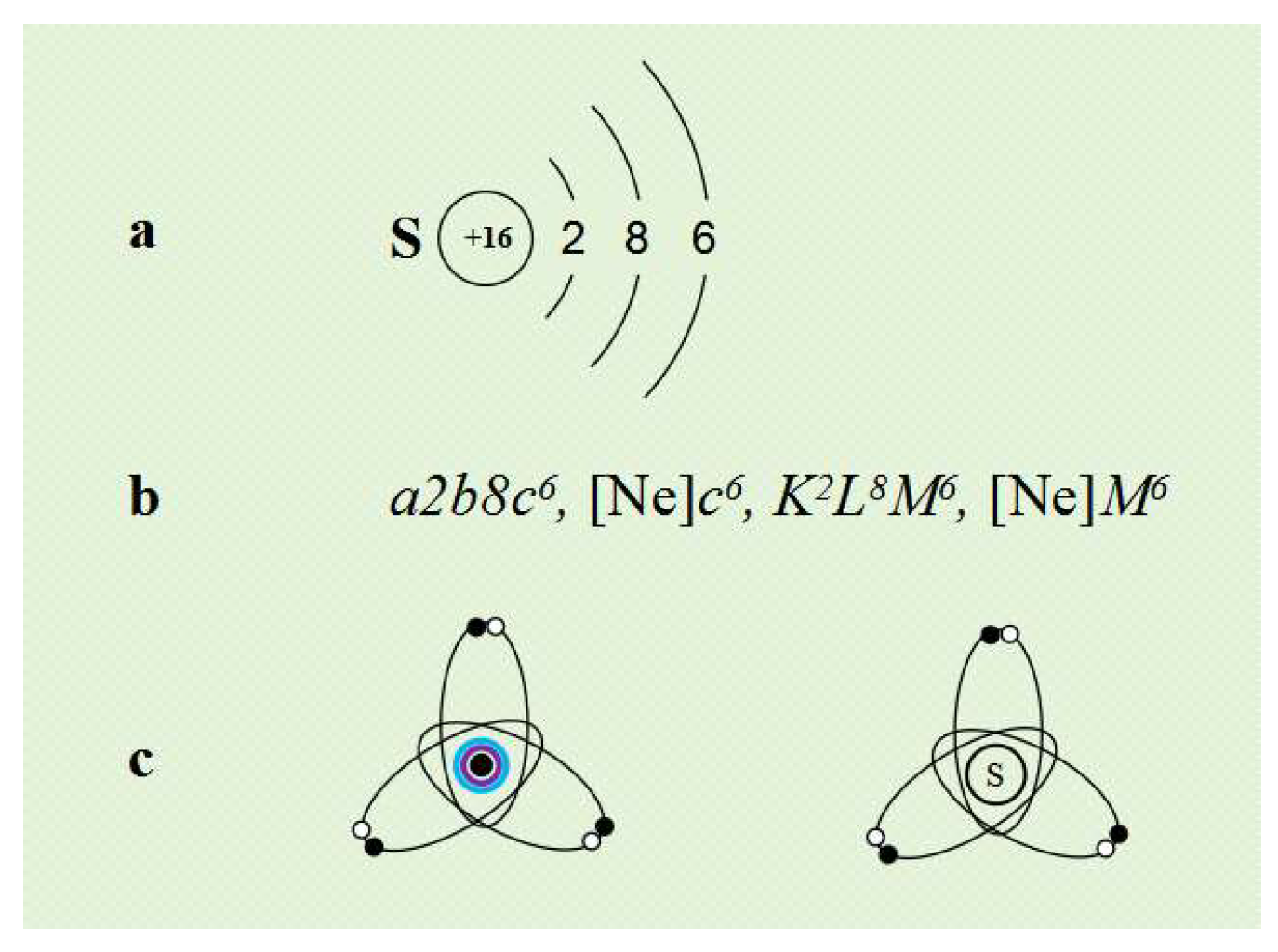

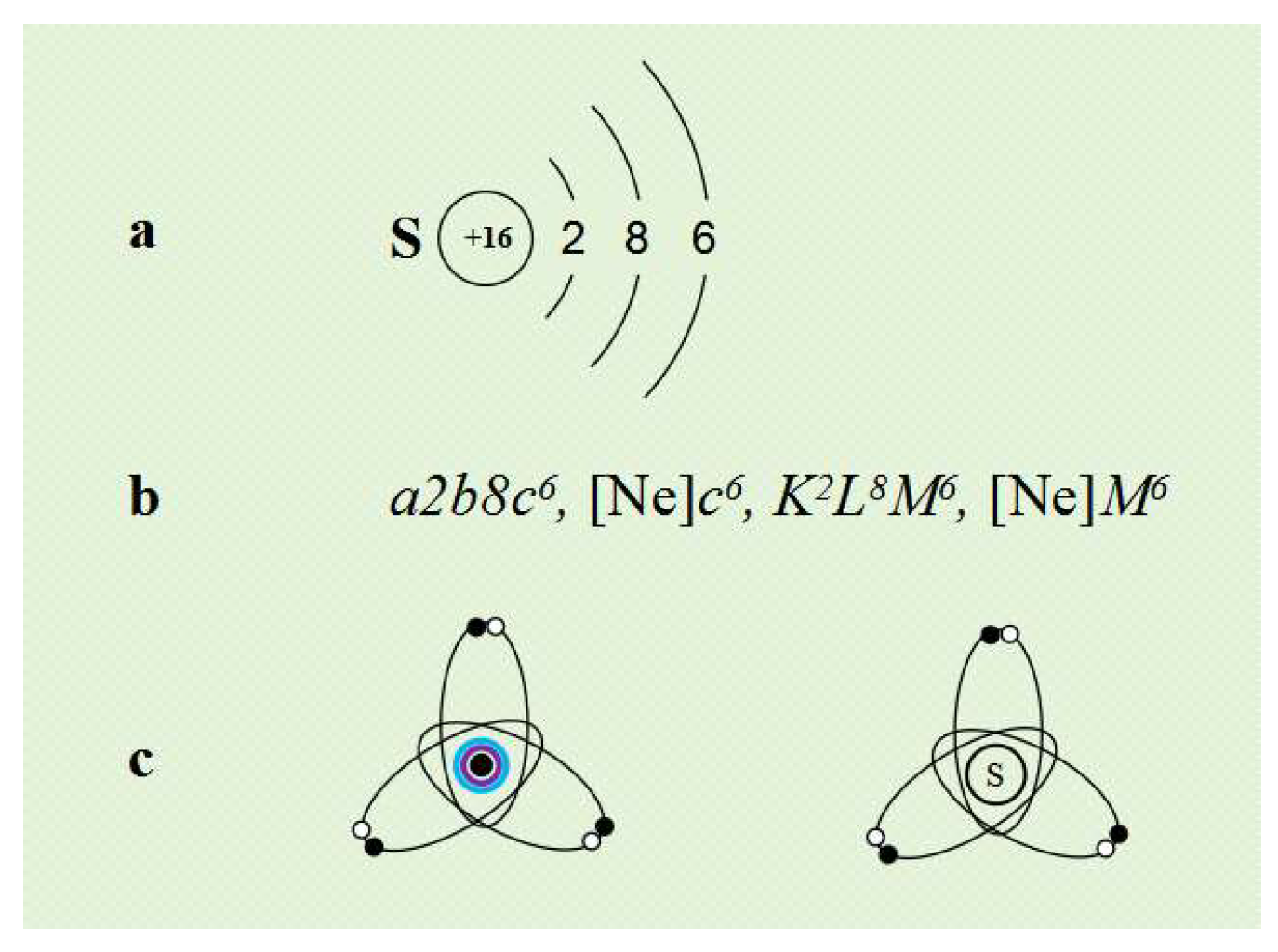

To represent the electron arrangement outside the atomic nucleus, we can use the method shown in

Figure 3 as needed.

Figure 3a,b can be used to represent the number of electrons in each electron layer outside the atomic nucleus, while

Figure 3c can be used to represent the spatial structure of the valence layer electron orbits of the atom.

The Formation and Essence of Chemical Bonds

Molecules are structural forms formed by the combination of atoms. According to the principle of minimum energy, atoms can combine with each other to form stable molecules, and the energy (

EM) of the molecular system must be less than the sum of the energies

EA (i) of each atomic system before the formation of the molecule:

If the energy of a molecule composed of atoms combined with each other is less than the total energy of the ground states of each atom, it must be due to gravitational interactions between the atoms, thereby reducing the potential energy of the system. Obviously, the gravitational interaction between atoms must be electromagnetic interaction, either electrostatic attraction or magnetic attraction.

Generally, the outermost electrons of metal elements have higher energy levels. When the atomic system is in a higher energy state, these electrons are prone to becoming free electrons, leaving the metal atoms as positively charged cations. If a large number of identical excited-state metal atoms gather together, during the de-excitation process, the metal cations and free electrons will bind together through electrostatic attraction, forming metal elemental molecules. If there are different metal atoms in the atomic system, a metal alloy is formed. The electrostatic attraction between metal cations and free electrons is called a metal bond.

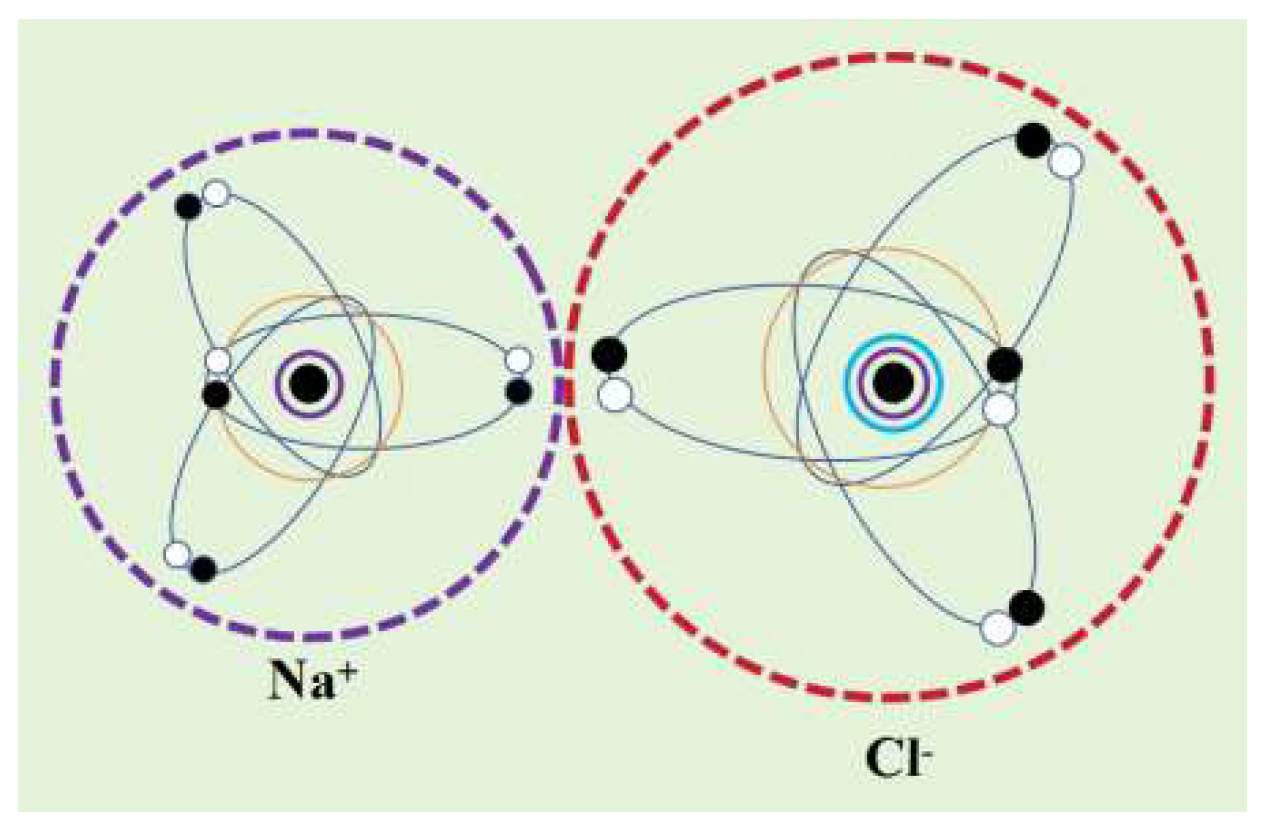

Usually, the outermost electron energy of non-metallic elements is low. When there is a single electron orbital in their ground state valence layer electron configuration, obtaining one electron can spin pair into a double electron orbital, thereby reducing the potential energy of the atomic system and forming a more stable anion. For instance, halogen elements like the chlorine atom (Cl) have 7 electrons in their outermost electron shell, with a valence electron configuration of V

7-1. There are 4 electron orbits in its ground state, among which 3 are paired electron orbits and 1 is a single electron orbital. If the chlorine atom gains 1 electron, its valence electron configuration will change to V

8-1, resulting in 4 paired electron orbits and a further reduction in potential energy. This transforms it into a stable [Ar] atomic core structure, forming a negatively charged chloride ion (Cl

-). The outermost electrons of metal atoms has higher electron energy, especially for alkali metal atoms such as sodium (Na), which has only one electron in its outermost shell, with the inner electron configuration forming a stable [Ne] atomic core structure. Consequently, the outermost electron is highly susceptible to becoming a free electron, forming a positively charged sodium ion (Na

+). When metal cations (Na

+) and non-metal anions (Cl

-) are mixed together, they attract each other through electrostatic forces, further lowering their potential energy and thereby forming a stable ionic compound molecule (NaCl) (

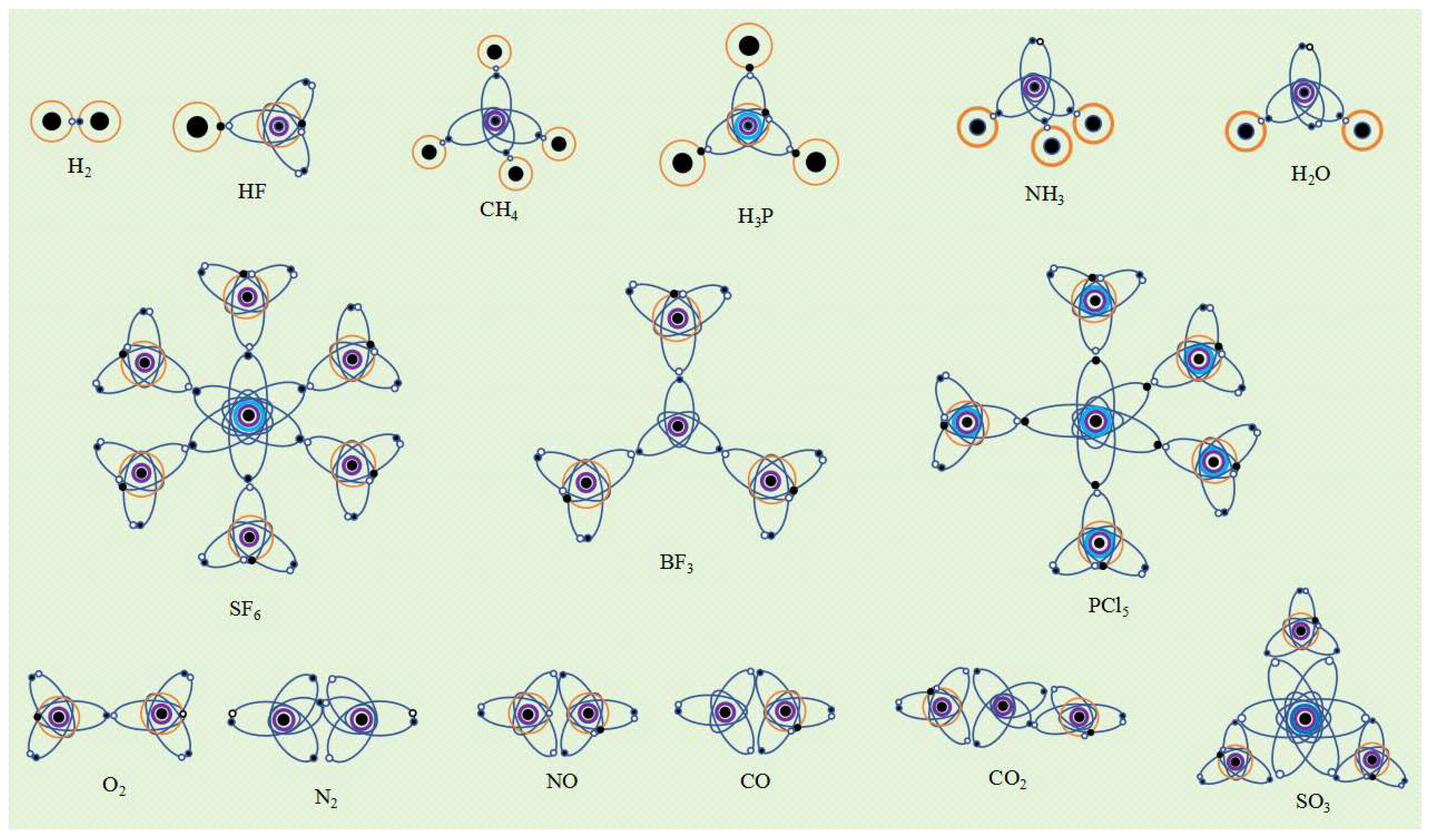

Figure 4). Positive and negative ions are attracted to each other by electrostatic forces. When the positive and negative ions approach each other, electrostatic repulsion is generated due to the negative charge of the electron orbital dynamic entity. When the electrostatic attraction between positive and negative ions is balanced with the electrostatic repulsion between the electron orbital dynamic entity, a stable ionic bond is formed.

If the outer electrons of an atom do not become free electrons to form cations, nor gain electrons to become anions, the atom remains electrically neutral, and thus atoms cannot attract each other through electrostatic forces. Obviously, the binding force between electrically neutral atoms can only be magnetic attraction. Since the magnetic moment of an atom primarily arises from the electron spin in the single-electron orbits of the outermost electron shell, when atoms with single electron orbits in the valence electron configuration approach each other, the dynamic entities of single electron orbits between atoms will be attracted to each other by spin magnetic force. When the spin magnetic force and electrostatic repulsion between single electron orbital dynamic entities reach equilibrium, stable covalent bonds are formed.

The rotational motion of atoms or ions causes their dynamic entities to take on a spherical shape. Sodium ions (Na+) carry a positive charge as a whole, represented by a purple dashed circle; The chloride ion (Cl-) carries a negative charge as a whole, represented by a red dashed circle. Sodium ions and chloride ions approach each other through electrostatic attraction, but they cannot approach infinitely because the two electron orbits between sodium ions and chloride ions are dynamic entities with negative charges, and there is electrostatic repulsion between them. When the electrostatic attraction and electrostatic repulsion between sodium ions and chloride ions reach an equilibrium state, stable ionic bonds are formed.

The Molecular Structure of Covalent Compounds

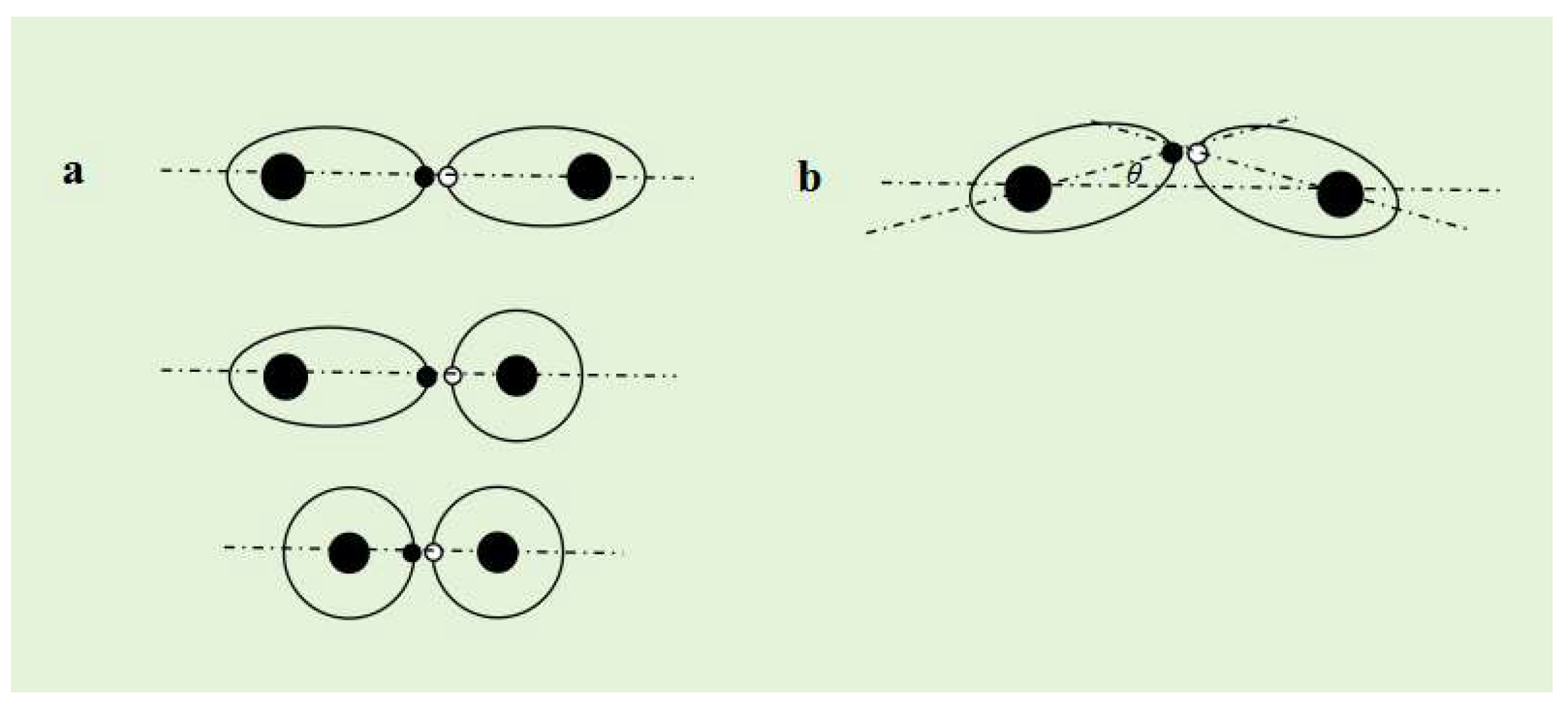

Due to the highest charge flux at the vertex of the ellipsoid of a single electron orbital dynamic entity, the electron spin field density per unit time is highest at that location. If the ellipsoidal single electron orbital dynamic entity of another atom approaches, then the two ellipsoidal single electron orbital dynamic entities must have the maximum

spin magnetic force at the vertex in a "head to head" manner, which determines the directionality of the covalent bond. When single electron orbits are attracted to each other by spin magnetic force, if the symmetry axes of the two single electron orbits are connected to the atomic nucleus on the same straight line, the covalent bond formed in this way is called an

α bond (

Figure 6a). If the symmetry axes of the two single electron orbits are not connected to the atomic nucleus on the same straight line, the covalent bond formed in this way is called a

β bond (

Figure 6b).

Assuming that A atom forms an

α bond with B atom, and the "charge spin quantity" of A atom's single electron orbit is

, and the "charge spin quantity" of B atom's single electron orbit is

, then the spin magnetic force of their spin pairing is:

Due to the coincidence of the electron orbital symmetry axis of the α bond with the line connecting the two atomic nuclei of AB, the spin magnetic force of spin pairing is the binding force between AB atoms.

Assuming that A atom and B atom form a β bond, and the angle between the symmetry axis of the single electron orbit and the line connecting the atomic nucleus is θ, the binding force between AB atoms is . Therefore, the beta bond is slightly weaker than the α bond.

Based on the sum of the energies of each atomic system and the difference in energy between the molecular system, we can determine the bond energy of covalent bonds

If an atom has only one single electron orbital in its valence electron configuration, then the covalent bond it forms with other atom that has only one single electron orbital must be an α bond. For example, a hydrogen atom has only one single electron orbital, and any covalent bond formed between it and any atom is an α bond. In molecules such as SF6, BF3, and PCl3, the valence layer electron configuration of F and Cl atoms is V7-1, with only one single electron orbital. Therefore, the S-F, B-F, and P-Cl covalent bonds are all α bonds.

If an atom has multiple single electron orbits in its valence layer, then the covalent bond it forms with other atoms that only have one single electron orbital must also be an α bond. For example, the valence layer electron configuration of carbon atoms in methane molecules (CH4) is V4-5, with four ellipsoidal single electron orbits that spin pair with the single electron orbits of four hydrogen atoms to form four covalent bonds, all of which are α bonds.

Since an atom with multiple single electron orbits can form covalent bonds with multiple atoms, such an atom is the central atom of covalent molecule. The spatial configuration of the valence electron orbits of the central atom usually determines the spatial structure of the molecule. For example, the electronic orbital spatial configuration of the carbon atom valence layer in methane molecules is V

4-4, which is a tetrahedral spatial structure composed of four ellipsoidal single electron orbital dynamic entities. Therefore, the spatial configuration of methane molecules is tetrahedral. Similarly, the valence layer electronic configuration V

5-4 of phosphorus atoms in phosphine molecules (PH

3) is a planar triangular spatial structure composed of three ellipsoidal single electron orbital dynamic entities, hence its spatial structure is a planar triangle. The electronic configuration of the valence layer of sulfur atoms in SF

6 molecules is V

6-11, which is a regular octahedral structure composed of six single electron orbits. Therefore, the spatial structure of SF

6 molecules is a regular octahedron. The valence layer electronic configuration of boron atoms in BF

3 molecule is V

3-3, which is a equilateral triangle structure composed of three ellipsoidal single electron orbital dynamic entities. Therefore, the spatial structure of BF

3 molecule is a planar equilateral triangle. The valence layer electron configuration of phosphorus atom in PCl

5 molecule is V

5-9, which is a triangular bipyramid structure composed of five single electron orbits. Therefore, the spatial structure of PCl

5 molecule is a triangular bipyramid (

Figure 7).

The valence layer electron configuration of nitrogen atoms in ammonia molecules (NH

3) is V

5-4, which is a tetrahedral structure composed of three single electron orbits and one double electron orbital. Since the double electron orbits do not participate in the formation of covalent bonds, the spatial structure of ammonia molecules is not a regular tetrahedron but a triangular pyramid. Due to the higher charge of the double electron orbital dynamic entity compared to the single electron orbital, it forms a stronger squeezing effect on the other three single electron orbits, resulting in a smaller H-N-H bond angle of 107° instead of 109.47°. Similarly, the valence layer electron configuration of oxygen atoms in water molecules (H

2O) is V

6-4, which is a tetrahedral structure composed of two single electron orbits and two double electron orbits. Since two double electron orbits do not participate in the formation of covalent bonds, only two single electron orbits form covalent bonds, the spatial structure of water molecules is a triangular structure. Due to the higher charge of the double electron orbital dynamic entity compared to the single electron orbital, a squeezing effect is formed on the other two single electron orbits, resulting in a smaller H-O-H bond angle of 104.5°for water molecules instead of 109.47°(

Figure 7).

If an atom has multiple single electron orbits in its valence electron configuration, it may form 2 or 3 covalent bonds when it approaches another atom that also has multiple single electron orbits. For example, the electronic configuration of the valence layer of an excited oxygen atom is V

6-3, with 2 double electron orbits and 2 single electron orbits. Two oxygen atoms form two

α bonds by spin pairing with an ellipsoidal single electron orbit and a spherical single electron orbit, respectively, and combine to form an oxygen molecule (O

2) (

Figure 7). Due to the exposure of spherical single electron orbits in the outer layer of the molecule, oxygen molecules are susceptible to the influence of external magnetic fields, thus exhibiting paramagnetism. In addition, due to the large distance between the spherical single electron orbits of two oxygen atoms, the formed

α bond is weak and easy to break, thus oxygen molecules have strong chemical activity. When two

α bonds are formed between atoms due to the simultaneous existence of ellipsoidal and spherical single electron orbits, we call the

α bond formed between ellipsoidal single electron orbits "type I

α bond" and the

α bond formed between spherical single electron orbits "type II

α bond".

If there are multiple ellipsoidal single electron orbits in the valence layer electronic configuration of an atom, due to the presence of certain angles in their spatial distribution, the 2 or 3 covalent bonds formed between such atoms must be

β bonds. For example, the valence layer electron configuration of an excited nitrogen N atom is V

5-6, with one ellipsoidal double electron orbits and three ellipsoidal single electron orbits. Two nitrogen atoms spin pair with three ellipsoidal single electron orbits to form three

β bonds, forming a nitrogen molecule (N

2). Nitric oxide molecule (NO) forms two

β bonds between the two ellipsoidal single electron orbits of N atom and the two ellipsoidal single electron orbits of O atom. Due to the presence of an unpaired single electron orbital in the N atom, NO molecules exhibit paramagnetism. The valence layer electronic configuration of carbon atoms in carbon monoxide (CO) molecules is V

4-3, and the valence layer electronic configuration of oxygen atoms is V

6-3. The two ellipsoidal single electron orbits of C atoms and the two ellipsoidal single electron orbits of O atoms form two

β bonds. There are no unpaired single electron orbits in CO molecules, therefore it has diamagnetism. In carbon dioxide molecules (CO

2), the valence layer electron configuration of carbon atoms is V

4-5, with 4 single electron orbits. One carbon atom can form 4

β bonds with 2 oxygen atoms, and the O-C-O bond angle is 180°. The spatial structure is linear. The valence layer electronic configuration of sulfur atoms in sulfur trioxide molecules (SO

3) is V

6-13, with six single electron orbits uniformly distributed in the same plane at an angle of 60°. Therefore, one sulfur atom can form six

β bonds with three oxygen atoms, with an O-S-O bond angle of 120°. The spatial structure of SO

3 molecules is a planar triangle (

Figure 7).

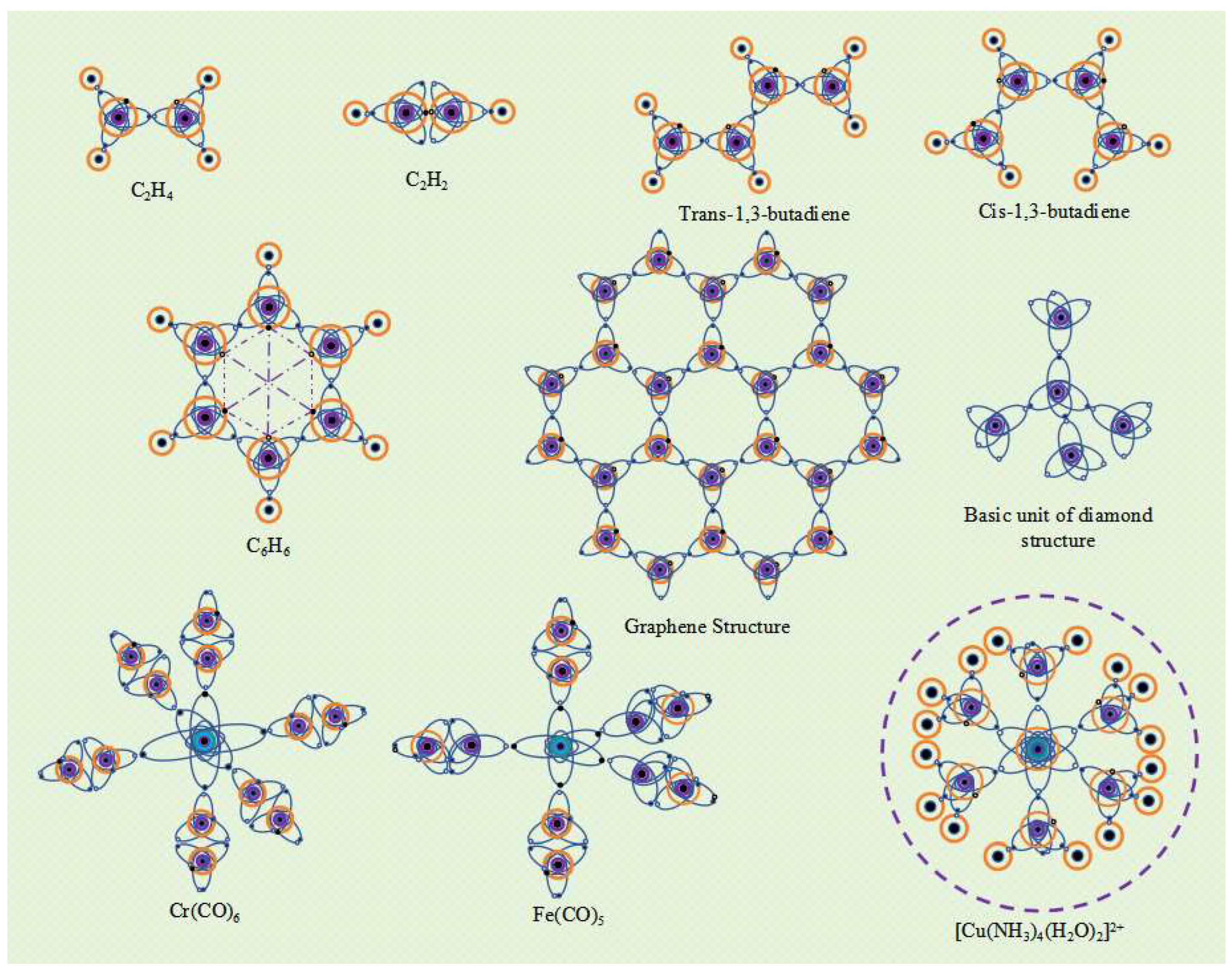

The two carbon atoms of ethylene molecule (C

2H

4) have a V

4-4 valence layer electronic configuration. The two ellipsoidal single electron orbits in the valence layer of each carbon atom spin pair with the single electron orbits of hydrogen atoms to form two "C-H" type I

α bonds. Two carbon atoms form a "C-C" type I

α bond with ellipsoidal single electron orbit spin pairing, and a "C-C" type II

α bond with spherical single electron orbit spin pairing. Type II

α bonds are weaker than type I

α bonds and are more prone to breakage, making ethylene molecules more reactive. The two carbon atoms of acetylene molecule are also in the V

4-4 valence layer electronic configuration, forming two "C-C"

β bonds and one "C-C" α bond between the two carbon atoms. Due to the presence of more

β bonds in the covalent bonds of acetylene molecules, they are more reactive than ethylene molecules. The carbon atoms in butadiene (including trans and cis 1,3-butadiene) are also in the V

4-4 valence layer electronic configuration. In addition to forming an I type

α bond, adjacent carbon atoms also form a "C-C" II type

α bond. The four carbon atoms in the butadiene molecule are tightly bound together by three type I

α bonds and three type II

α bonds, further reducing the energy of the molecular system. Therefore, the butadiene molecule has high stability. The valence layer electronic configuration of the six carbon atoms in benzene molecule (C

6H

6) is V

4-4, with each carbon atom having a "C-C" type I

α bond and a "C-C" type II

α bond with adjacent carbon atoms. In addition, the spherical single electron orbits between carbon atoms in opposite positions on the benzene ring have opposite electron spin directions, resulting in spin magnetism and the formation of "C-C" type II

α bonds. In this way, a strong bond is formed between the six carbon atoms of the benzene ring molecule, and the potential energy of the molecular system is greatly reduced, making the benzene ring molecule very stable (

Figure 8).

The electronic configuration of the valence layer of an atom reflects its energy state. Different energy states determine the different valence electron configurations of atoms, and when covalent compound molecules are formed, they form different spatial structures. Therefore, the spatial structure of a molecule is essentially determined by the energy state of the atoms at the time of its formation. For example, in excited states with lower energy levels, the valence electron configuration of carbon atoms is V

4-4, and adjacent carbon atoms can form type I

α bonds and type II

α bonds. Six carbon atoms can form a stable hexagonal structure like a benzene ring. By using this as a unit, a planar network structure composed of regular hexagonal structures can be formed, which is the basic structure of graphene molecules. Graphene with a planar network structure is stacked layer by layer, and the spherical single electron orbits of carbon atoms between layers exhibit spin magnetic interactions, forming sheet-like graphite. If the edges of such a planar network structure are raised and connected end-to-end, fullerene molecular structures can be formed, which can be spherical, ellipsoidal, cylindrical, or tubular in shape. At higher energy levels of excitation, the valence electron configuration of carbon atoms changes to V

4-5, with each carbon atom serving as the central atom and forming four Type I

α bonds with four carbon atoms. The four carbon atoms form a three-dimensional network structure at the vertices of a regular tetrahedron, which is known as the diamond molecular structure (

Figure 8). Due to the strong covalent bonds formed between each carbon atom and four carbon atoms, releasing a large amount of energy, the spatial potential energy of the entire molecular system is extremely low, making diamond molecules very stable. Elemental allotropes like graphene and diamond are giant covalent molecules with different structures formed under excited states of different energy states.

Transition metal elements are less active than alkali and alkaline-earth metal elements, and electrons outside the atomic nucleus are less likely to become free electrons. Therefore, if a transition metal element has single electron orbits in its valence electron configuration, these single electron orbits can form covalent bonds with the single electron orbits of other atoms. For example, the outermost layer of Cr atom has 6 electrons, and the excited valence layer electron configuration is V

6-11, which is a regular octahedral structure. When the CO molecule is in an excited state, the valence layer electronic configuration of carbon atoms changes to V

4-4, and one single electron orbital of the Cr atom forms a covalent bond with one single electron orbital of the carbon atom. Each of the six single electron orbits of the Cr atom can bond with a CO molecule, forming the Cr(CO)

6 molecule (

Figure 8).

The metal element Fe has 8 electrons in its outermost shell. In an excited state, 3 electrons become free and the resulting ion is called Fe

3+, leaving 5 electrons in the outermost shell, which can form a V

5-9 electron configuration. When Fe atoms are mixed with CO molecules, 3 CO molecules receive 3 electrons from the Fe atom to become 3 CO

- ions. These CO

- ions then combine with Fe

3+ ions under electrostatic attraction, releasing energy that further excites the O and C atoms within the CO

- ions, changing their valence electron configurations to V

7-5 and V

4-5, respectively, and forming three

β-bonds between the O and C atoms. Each C atom also has an elliptical single-electron orbital that forms 3 α-bonds with the three coplanar elliptical single-electron orbits in the V

5-8 electron configuration of the Fe atom. For CO molecules that have not acquired electrons, the bonding between the C and O atoms remains unchanged, but in the excited state, the valence electron configuration of the C atom changes to V

4-4, gaining an additional elliptical single-electron orbital. Two such excited CO molecules form two α-bonds with the two single-electron orbits in the V

5-8 electron configuration of the Fe atom that are perpendicular to the planar triangle. In this way, five CO molecules combine with one Fe atom to form a Fe(CO)

5 molecule (

Figure 8). The Fe(CO)

5 molecule contains both ionic bonds between the Fe

3+ ion and the three CO

- ions, and five covalent bonds between the Fe atom and C atom, making it a special compound that possesses both ionic and covalent bonds.

The electron arrangements of Group VIII elements, Group IB elements, lanthanide and actinide elements have special characteristics, and the arrangement of their inner and outermost electrons usually needs to be adjusted according to the energy state of the atomic system. When the number of outermost electrons changes, such as losing n electrons, the configuration of the valence layer electrons needs to be adjusted compared to the atoms with the previous n atomic numbers. For example, when the Cu atom of element 29 loses two electrons to become Cu

2+, its number of electrons outside the nucleus is the same as that of element 27 Co, and the valence layer electrons are both 7. In the excited state, Cu

2+ can form the V

7-11 electronic configuration, while the N atom in NH

3 and the O atom in H

2O form the V

5-5 and V

6-7 electronic configurations, respectively. Four excited NH

3 molecules (with N atom having an ellipsoidal single electron orbital) and two excited water molecules (with O atom having an ellipsoidal single electron orbital) form six covalent bonds with excited Cu

2+ (with six ellipsoidal single electron orbits), forming stable [Cu (NH3) 4 (H2O) 2]

2+ complex ions (

Figure 8).

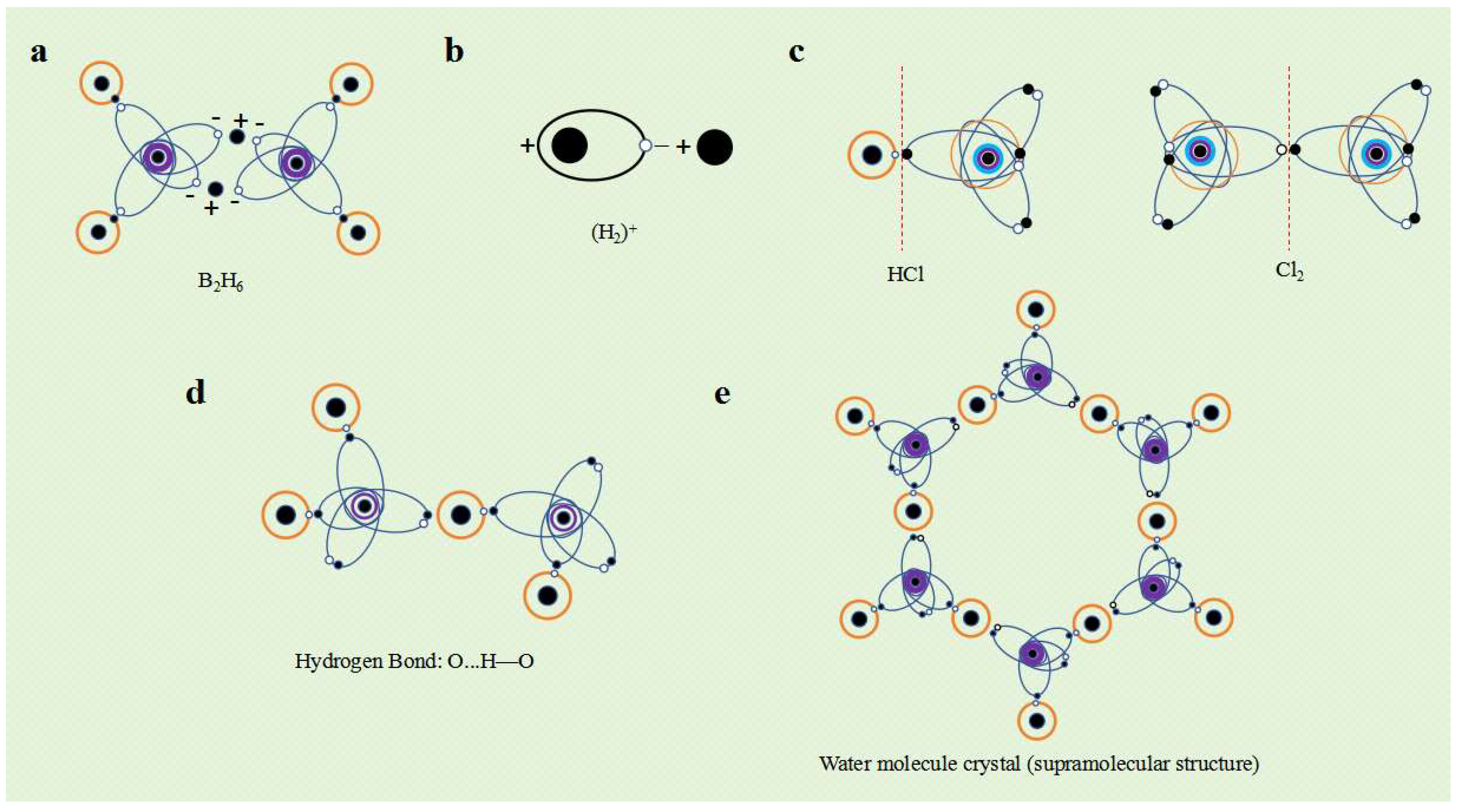

Some non-metallic elements also undergo changes in their valence layer electronic configuration after obtaining electrons. For example, when excited, the B atom forms a V3-3 electronic configuration and can form a BH3 covalent molecule with three hydrogen atoms. But under certain conditions, after B atom captures an electron from one of the hydrogen atoms, its valence layer electron configuration changes to V4-4, forming two ellipsoidal single electron orbits. BH3 becomes (BH2)- ion, and one hydrogen atom becomes a hydrogen ion (H+). The (BH2)- ion as a whole is negatively charged, and its ellipsoidal single electron orbit exhibits a negative charge property. Therefore, two (BH2)- ions can tightly bind with the electrostatic attraction between two hydrogen ions H+ to form diborane molecules (B2H6) (Figure 9a). This type of compound is called a hydrogen bridge compound, which combines two negative ions with single electron orbits through electrostatic attraction using hydrogen ions (protons).

Polarity of Molecules and Intermolecular Forces

The atoms that make up a molecule form different spatial structures due to their different valence electron configurations. If the electronic configuration space structure of the entire molecule is uniformly symmetrical, then the charge distribution of the entire molecular system is uniform, and the molecule exhibits non-polar characteristics, which we call non-polar molecules. If the electronic configuration space structure of a molecule is asymmetric, non-uniform, or symmetric but non-uniform, then the charge distribution of the entire molecular system is non-uniform, and the molecule exhibits polar characteristics, which we call polar molecules. In polar molecules, they exhibit negative charge properties in directions with more charge distribution and positive charge properties in directions with less charge distribution.

Taking hydrogen chloride (HCl) molecules as an example, chlorine atoms have 7 valence electrons, while hydrogen atoms only have 1 valence electron. The distribution of "electron orbital dynamic entities" in the molecular system is significantly uneven, and the charge distribution is significantly more in the direction of chlorine atoms than in the direction of hydrogen atoms. Therefore, HCl molecules are polar molecules. The chlorine molecule (Cl

2) has two identical chlorine atoms, and due to the completely uniform and symmetrical spatial distribution of the valence layer "electron orbital dynamic entity" of the two chlorine atoms, the charge distribution is uniform and exhibits non polarity (

Figure 9c).

The simplest atom is a hydrogen atom, where an electron orbits a proton in a circular or elliptical motion. Observing over a period of time, a hydrogen atom is a dynamic entity with a spherical or ellipsoidal electron orbit surrounding a proton. However, in the case of instantaneous observation, hydrogen atoms can be regarded as an electric dipole composed of protons and electrons at any moment. In the direction close to the electron, hydrogen atoms have a negative charge property, while in the direction close to the proton, hydrogen atoms have a positive charge property. Therefore, hydrogen atoms exhibit polarity under instantaneous observation. The hydrogen molecular ion (H

2)

+ is actually the product of the instantaneous electrostatic attraction between hydrogen atoms and hydrogen ions (H

+) in a polar state (

Figure 9b).

Polarized molecules (HX) containing hydrogen atoms are usually positively charged in the direction of the hydrogen atom, and correspondingly negatively charged in the direction of other atoms. The electrostatic attraction between polar molecules (HX ··· HX) occurs between the hydrogen atom and other atoms, which is called hydrogen bonding. Since hydrogen atoms have only one electron outside the nucleus, the molecular charge distribution formed by their combination with other atoms is the most uneven, resulting in a higher polarity. Hydrogen bonds have stronger electrostatic attraction than other polar molecules.

Figure 9d illustrates the hydrogen bonds between water molecules.

Since the overall effect of dynamic entities is not only related to the periodic motion speed but also to the observation distance, the overall effect of electronic orbital dynamic entities becomes more pronounced when the distance between molecules is far, and less pronounced when the distance between molecules is close. When the distance between molecules is very close, the instantaneous relationship between electrons and atomic nuclei exhibits an electric dipole mode, and the instantaneous interaction between molecules is manifested as the interaction between dipole moments. Due to the inherent polarity of polar molecules, the dynamic electronic orbits of non-polar molecules are attracted to the positive charge side of polar molecules and tilt, resulting in induced dipole moments. The so-called dispersion force, induction force, and orientation force are all short-range forces, manifested as attractive forces between molecules at close distances, with a range of only a few picometers. These intermolecular forces are collectively referred to as van der Waals forces, which are essentially electrostatic forces generated by molecular or atomic polarity.

Just like metal elements and ionic compounds can form crystal structures, there is electrostatic attraction between molecules, which can also form molecular crystal structures. Due to the spatial structure of molecules and the specific valence electron configurations of the atoms that make up the molecules, the electrostatic attraction between molecules exhibits significant directionality and saturation. The polarity or instantaneous polarity between molecules generates electrostatic attraction, causing molecules to condense and form different molecular crystals or supramolecular structures. For example, water molecules interact with each other through hydrogen bonds to form water molecule crystals (

Figure 9e).

When the energy state of the molecular system is low, the volume of the "dynamic entity of electron orbits" outside the ground state atomic nucleus is small, manifested as the small volume of atoms and molecules, which can tightly bind and condense into a solid "molecular cluster". When the energy state is high, the volume of atoms and molecules is relatively large, and the binding between atoms and molecules is not very tight, resulting in a condensed "molecular cluster" that appears as liquid. When the energy state is higher, the volume of atoms and molecules becomes larger, the bonding between atoms and molecules becomes less tight, the cohesion between molecules becomes weak, and the molecular aggregates appear in a gaseous state. The change of a substance composed of molecules from solid to liquid and gas is a manifestation of the energy state change of the molecular system, which is usually referred to as physical change. The change in state of matter usually refers to the change in the composition of substances composed of the same molecular aggregates. If molecules of different substances are mixed together, chemical changes may occur simultaneously with the change in the state of matter.

The Physical Mechanism of Chemical Reactions

The essence of a chemical reaction is the formation of new ionic or covalent bonds between different atoms that make up a substance molecule, the formation of new substance molecules from different atoms, or the formation of different molecular structures from molecules composed of the same atoms. At normal temperature and pressure, the chemical reaction in which different types of substance molecules mix to form new substance molecules is called spontaneous chemical reaction. A chemical reaction that cannot occur spontaneously at room temperature and pressure and requires conditions such as heating, pressure, or light exposure is called a non spontaneous chemical reaction.

Mixing different types of liquid molecules, or mixing between liquids and solids, or between liquids and gases, is prone to spontaneous chemical reactions. Usually, acid-base reactions, ion exchange reactions, and so-called coordination reactions are spontaneous chemical reactions. In acid-base reactions, such as mixing hydrochloric acid and sodium hydroxide solutions, hydrogen ions (H+) , chloride ions, sodium ions, and hydroxide ions (OH-) mix together, and positive and negative ions recombine under the interaction of electrostatic attraction. H+and OH- attract each other under electrostatic attraction. The excess electron outside the oxygen nucleus in the OH- is captured by H+, and the valence layer electron of the oxygen atom is lost, forming an elliptical shape and becoming a single electron orbit. The H+ obtains an electron and becomes a hydrogen atom with a single electron orbit. The single electron orbits outside the hydrogen nucleus can form covalent bonds with the single electron orbits of oxygen atoms in OH- , generating H2O molecules.

Sodium chloride solution is a homogeneous mixture of sodium ions and chloride ions (Cl-), while silver nitrate solution is a homogeneous mixture of nitrate ions and silver ions (Ag+). When sodium chloride solution and silver nitrate solution are mixed, these four ions will also be evenly distributed, which means that recombination will occur between these ions. Cl- combines with Ag+ under electrostatic attraction to form AgCl, which precipitates due to its insolubility in water.

Sodium carbonate dissolves in water and dissociates into carbonate ions (CO32-) and sodium ions. If hydrochloric acid is added to a sodium carbonate solution, a large amount of hydrogen ions (H+) are dissociated from hydrochloric acid in water. H+ combines with CO32- under electrostatic attraction, and H+ obtains an electron from CO32- to form a hydrogen atom. Two hydrogen atom single electron orbits form two covalent bonds with two ellipsoidal single electron orbits of oxygen atoms, generating H2CO3. At room temperature and pressure, the H2CO3 structure is unstable and spontaneously forms CO2 and H2O.

Copper sulfate solution contains Cu2+ and SO42-. When excessive ammonia water is added, due to the strong polarity of NH3 molecules, H2O molecules can dissociate into H+ and OH- in aqueous solution. Cu2+and OH- combine through electrostatic attraction to form Cu (OH)2 precipitate. The released energy will excite some atoms, transforming double electron orbits into single electron orbits and changing the valence layer electron configuration. For example, the valence layer electron configuration of Cu2+ is excited to V7-11 electron configuration, the valence layer electron configuration of N atoms in NH3 is excited to V5-5, and the valence layer electron configuration of O atoms in water molecules is excited to V6-7. Therefore, Cu2+ can form 6 covalent bonds with 4 NH3 and 2 H2O, generating stable [Cu (NH3)4(H2O)2]2+ ions that combine with SO42- to form [Cu(NH3)4(H2O)2]SO4.

These spontaneous chemical reactions have one thing in common, which is that after the reactants are mixed, there is electrostatic interaction between ions, and different ions recombine to form a new molecular system. The potential energy decreases, releasing energy and forming more stable ionic compounds, or exciting the valence layer electronic configuration change of atoms in ions or polar molecules (from double electron orbits to single electron orbits), and then forming stable covalent compounds.

If different substance molecules cannot be combined by electrostatic attraction after mixing, and the atoms that make up the molecules cannot form new bonds by spin magnetic force, then spontaneous chemical reactions will not occur. Usually, additional energy needs to be provided, such as heating, pressure, or light, in order for chemical reactions to occur. These additional energies increase the potential energy of molecules and atomic systems, breaking existing chemical bonds or transforming double electron orbits into single electron orbits, changing the electronic configuration of the atomic valence layer, thus allowing new bonds to form between atoms and form new compounds.

For example, in the valence layer electronic configuration of a nitrogen atom in nitrogen gas, three single electron orbits form three covalent bonds with three single electron orbits of another nitrogen atom. The two hydrogen atoms in a hydrogen molecule also form covalent bonds with two single electron orbits (

Figure 7). Due to the lack of ionic interactions and single electron orbits between covalent molecules nitrogen and hydrogen, spontaneous chemical reactions do not occur at room temperature and pressure. Under high temperature and pressure, nitrogen and hydrogen molecules enter a high-energy state where the covalent bonds within the molecules are broken. Subsequently, the single-electron orbits of nitrogen atoms can form covalent bonds with the single-electron orbits of hydrogen atoms, leading to the production of ammonia.

Disscussion

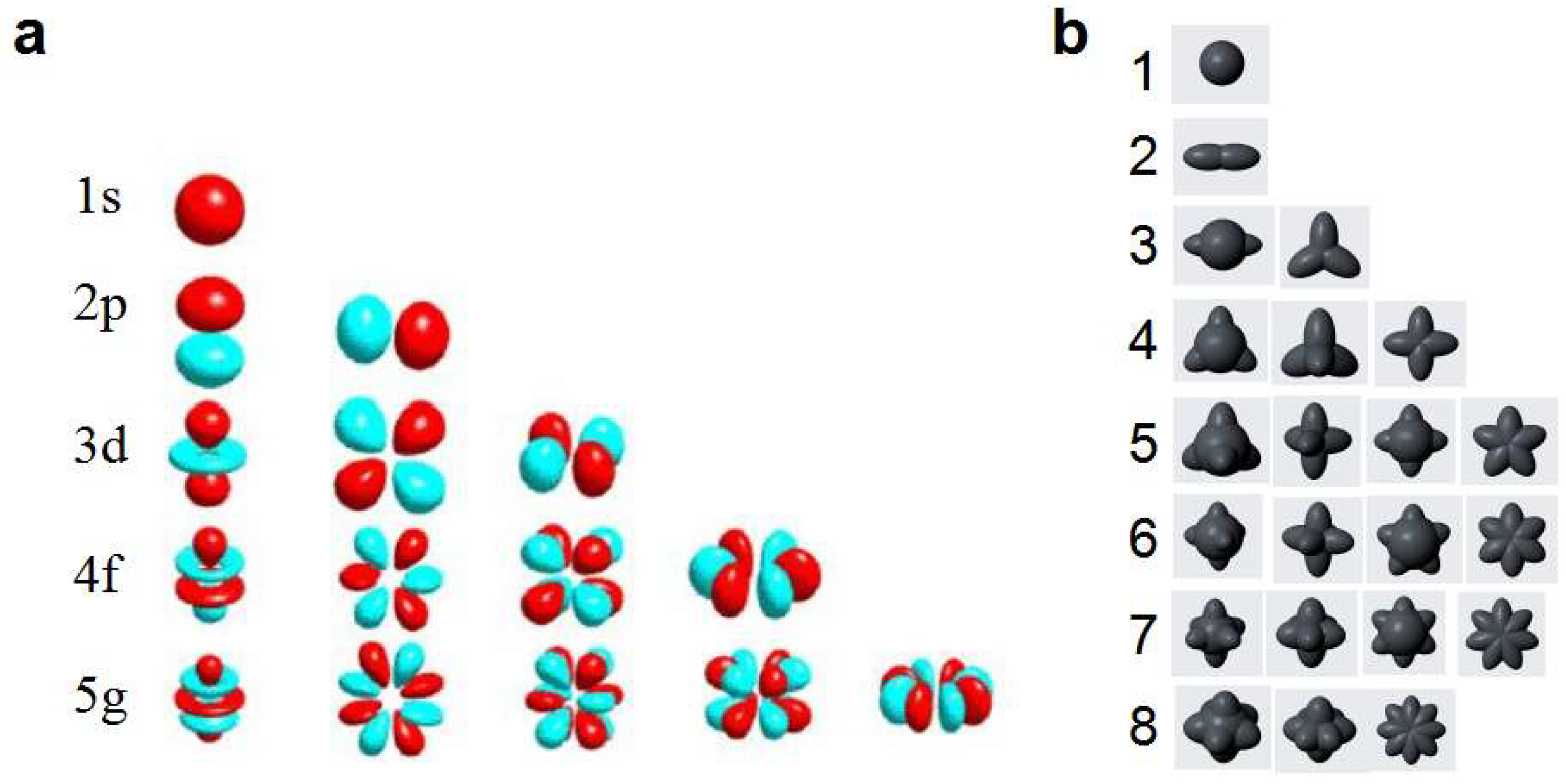

Based on the basic physical fact that electrons move in a circular or elliptical motion around the nucleus, this paper proposes a dynamic entity model of electron orbit. In this model, the shape of the electron orbit is the dynamic entity formed by the trajectory of electron movement, and the orbits of the same electronic layer are degenerate orbits with the same orbital radius and energy level. The spatial distribution of these degenerate orbits constitutes a uniformly symmetric spatial configuration of electron orbits. Therefore, in the electronic orbital space configuration, there is no concept of electron subshells as found in quantum mechanics, nor is there the issue of energy level crossing. Comparing the shapes of electron subshells in quantum mechanics with our spatial configuration of electron orbits (

Figure 10), it can be seen that the shapes of electron subshells are bizarre and completely inconsistent with the circular or elliptical motion laws of electrons under the electrostatic attraction of the nucleus, failing to explain the actual trajectories of electrons. In contrast, our spatial configuration of electron orbits fully aligns with the continuity and certainty of electron motion orbit concepts in classical physics, conforming to empirical common sense and intuition. By treating electron orbits as dynamic entities, we avoid the complex and unnecessary task of studying the precise spatial position and momentum of electrons at any moment, greatly simplifying various calculations and allowing us to focus on the dynamic characteristics and overall effects embodied by the high-speed periodic motion of electrons around the nucleus. Therefore, our model of the dynamic entity for electron orbits and the theory of the spatial configuration of electron orbits are not only more aligned with the objective reality of physics compared to the electron cloud model and electron subshell theory, but also possess significant advantages of simplicity and intuitiveness.

Based on the fundamental fact that there is electrostatic attraction between electrons and atomic nuclei, we propose the viewpoint that electron spin originates from the motion of electrons around the nucleus: the motion of electrons around the nucleus is similar to the motion of the moon around the earth, and the rotation period of electrons is the same as that of electrons around the nucleus. On this basis, the concept of electron spin quantity and the theory of electron spin quantity field were further proposed, revealing the physical mechanism of electron spin pairing and the quantization law of the mutual rotation motion of spin paired electrons. Quantum mechanics believes that the spin of electrons is an intrinsic property of electrons, avoiding the source of electron spin and the physical mechanism of electron spin pairing, making electron spin the most mysterious so-called pure quantum phenomenon. Our research has completely uncovered the mystery of electron spin, proving that electron spin is not inexplicable and mysterious, but can be deeply understood and interpreted through the principles of classical physics. This disruptive theoretical breakthrough undoubtedly brings new thinking and research directions to the physics community, marking a big step forward in our understanding of the microscopic world.

Based on the dynamic entity model of electronic orbits and the theory of electron spin, we propose the theory of electronic orbital spatial configuration, which solves the problem of multi electron atomic systems and obtains an accurate expression for the energy of the electron layer. For multi electron atomic systems, people usually use Slater's formula to calculate the energy of the electron layer, which introduces the concept of "shielding coefficient". The so-called shielding effect refers to the shielding effect of inner layer electrons on outer layer electrons, for example, when the inner layer electrons are close to the atomic nucleus, they will cancel out the positive charge of the atomic nucleus. However, Slater's "shielding coefficient" not only includes the shielding effect of inner layer electrons, but also the interaction between electrons in the same electron layer. Obviously, this coefficient does not fully conform to the concept of shielding effect. We have revised Slater's concept of "shielding coefficient", which only includes the shielding effect of inner electrons on outer electrons, and no longer includes the interaction between electrons in the same electron layer. We divide the interaction between electrons in the same electron layer into two parts: one is the mutual repulsion between dynamic entities in the electron orbit, and the other is the mutual attraction between spin paired electrons. The interaction between these two parts of electrons in the same electronic layer precisely forms a specific electronic orbital spatial configuration. Therefore, the energy of the electron layer can be expressed as the sum of three parts: "electron orbital energy level", "electron orbital spatial configuration potential energy", and "electron spin pairing energy". Based on the experimental data of atomic ionization energy, the "shielding coefficient" of different electron layers, the potential energy of electron orbital spatial configuration, and the electron pairing energy can be estimated. Our theory is very intuitive for handling multi electron atomic systems, with extremely simple methods and minimal computational complexity. This indicates that we have thoroughly solved the long-standing problem of multi electron atomic systems in the field of quantum chemistry.