Submitted:

13 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Study Design

Study Instruments

Data Analysis

Results

Discussion

Conclusion

References

- Ramos AR. Sleep Deprivation, Sleep Disorders, and Chronic Disease. Prev Chronic Dis 2023, 20, 230197. [CrossRef]

- Watson NF, Badr MS, Belenky G, et al. Recommended Amount of Sleep for a Healthy Adult: A Joint Consensus Statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society. Sleep 2015, 38, 843–844.

- LocalCircles. 61% Indians are getting less than 6 hours of uninterrupted sleep. LocalCircles. Available online: https://www.localcircles.com/a//press/page/world-sleep-day-survey (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Gupta R, Grover S, Basu A, et al. Changes in sleep pattern and sleep quality during COVID-19 lockdown. Indian J Psychiatry 2020, 62, 370. [CrossRef]

- Dunn C, Goodman O, Szklo-Coxe M. Sleep duration, sleep quality, excessive daytime sleepiness, and chronotype in university students in India: A systematic review. J Health Soc Sci 2022, 7, 36–52. [Google Scholar]

- Ramrakhiyani VC, Deshmukh SV. Study of the incidence and impact of chronic sleep deprivation in Indian population with special emphasis on neuropsychology testing. Sleep Med 2019, 14, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang MX, Wu AMS. Effects of smartphone addiction on sleep quality among Chinese university students: The mediating role of self-regulation and bedtime procrastination. Addict Behav 2020, 111, 106552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra S, Kar SK, Shankar A. Internet addiction and health profile among medical, dental and nursing graduates of India. Minerva Psychiatry; 64. Epub ahead of print August 2023. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee S, Kar SK. Smartphone Addiction and Quality of Sleep among Indian Medical Students. Psychiatry 2021, 84, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque S, Singh S, Narayan J, et al. Effect of smartphone use on sleep and mental health status of Indian medical students: a cross-sectional study. Int J Res Med Sci 2024, 12, 3737–3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal V, Khulbe Y, Singh A, et al. The digital health dilemma: Exploring cyberchondria, well-being, and smartphone addiction in medical and non-medical undergraduates. Indian J Psychiatry 2024, 66, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadzikowska-Wrzosek, R. Insufficient Sleep among Adolescents: The Role of Bedtime Procrastination, Chronotype and Autonomous vs. Controlled Motivational Regulations. Curr Psychol 2020, 39, 1031–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroese FM, Evers C, Adriaanse MA, et al. Bedtime procrastination: A self-regulation perspective on sleep insufficiency in the general population. J Health Psychol 2016, 21, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell RL, Bridges AJ. Bedtime procrastination mediates the relation between anxiety and sleep problems. J Clin Psychol 2023, 79, 803–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo J, Meng D, Ma X, et al. The impact of bedtime procrastination on depression symptoms in Chinese medical students. Sleep Breath 2020, 24, 1247–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou X, Hu J. Depression and bedtime procrastination: Chain mediation of brooding and perceived stress. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma X, Meng D, Zhu L, et al. Bedtime procrastination predicts the prevalence and severity of poor sleep quality of Chinese undergraduate students. J Am Coll Health J ACH 2022, 70, 1104–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill VM, Rebar AL, Ferguson SA, et al. Go to bed! A systematic review and meta-analysis of bedtime procrastination correlates and sleep outcomes. Sleep Med Rev 2022, 66, 101697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla A, Andrade C. Prevalence of Bedtime Procrastination in University Students and Reexamination of the Bedtime Procrastination Scale. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2023, 25, 22m03334. [Google Scholar]

- Kroese FM, De Ridder DTD, Evers C, et al. Bedtime procrastination: introducing a new area of procrastination. Front Psychol; 5. Epub ahead of print June 19, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Topp CW, Østergaard SD, Søndergaard S, et al. The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Psychother Psychosom 2015, 84, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care 2003, 41, 1284–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer F, Manea L, Trepel D, et al. Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: a systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2016, 39, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankowski, KS. Composite Scale of Morningness: psychometric properties, validity with Munich ChronoType Questionnaire and age/sex differences in Poland. Eur Psychiatry 2015, 30, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snyder E, Cai B, DeMuro C, et al. A New Single-Item Sleep Quality Scale: Results of Psychometric Evaluation in Patients With Chronic Primary Insomnia and Depression. J Clin Sleep Med JCSM Off Publ Am Acad Sleep Med 2018, 14, 1849–1857. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur G, Singh A. Excessive daytime sleepiness and its pattern among Indian college students. Sleep Med 2017, 29, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shad R, Thawani R, Goel A. Burnout and Sleep Quality: A Cross-Sectional Questionnaire-Based Study of Medical and Non-Medical Students in India. Cureus 2015, 7, e361. [Google Scholar]

- Giri P, Baviskar M, Phalke D. Study of sleep habits and sleep problems among medical students of pravara institute of medical sciences loni, Western maharashtra, India. Ann Med Health Sci Res 2013, 3, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzar MD, Zannat W, Kaur M, et al. Sleep in university students across years of university education and gender influences. Int J Adolesc Med Health 2015, 27, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G. A study on the sleep quality of Indian college students. JSM Brain Sci 2018, 3, 1018. [Google Scholar]

- Ball TM, Gunaydin LA. Measuring maladaptive avoidance: from animal models to clinical anxiety. Neuropsychopharmacol Off Publ Am Coll Neuropsychopharmacol 2022, 47, 978–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li X, Buxton OM, Kim Y, et al. Do procrastinators get worse sleep? Cross-sectional study of US adolescents and young adults. SSM - Popul Health 2020, 10, 100518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nauts S, Kamphorst BA, Stut W, et al. The Explanations People Give for Going to Bed Late: A Qualitative Study of the Varieties of Bedtime Procrastination. Behav Sleep Med 2019, 17, 753–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães P, Cruz V, Teixeira S, et al. An Exploratory Study on Sleep Procrastination: Bedtime vs. While-in-Bed Procrastination. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 5892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massar SAA, Ong JL, Lau T, et al. Working-from-home persistently influences sleep and physical activity 2 years after the Covid-19 pandemic onset: a longitudinal sleep tracker and electronic diary-based study. Front Psychol 2023, 14, 1145893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Domain | n (%) |

|---|---|

Age group

|

191 (47.63%) 196 (48.87%) 14 (3.49%) |

Gender

|

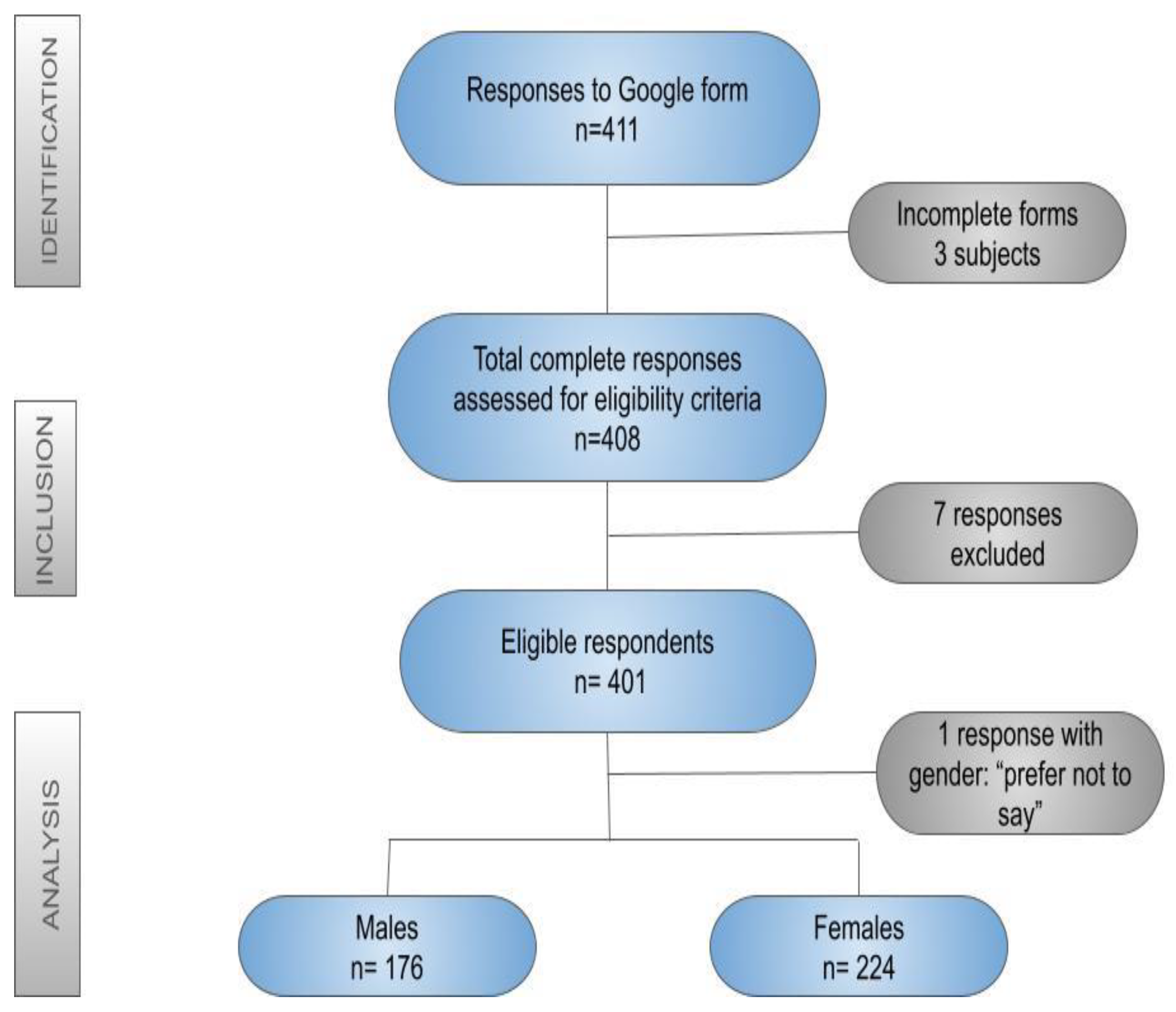

176 (43.89%) 224 (55.86%) 1 (0.25%) |

Occupation

|

150 (37.4%) 143 (35.6%) 40 (9.9%) 30 (7.48%) 15 (3.74%) 8 (1.99%) 15 (3.74%) |

Religion

|

361 (90%) 20 (4.98%) 4 (0.99%) 16 (3.99%) |

Domicile

|

322 (80.29%) 51 (12.71%) 28 (6.98%) |

| Question asked | Total responses | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|

| Do you have a personal electronic gadget? | 401 | 176 | 224 |

How many hours in a day do you spend on electronic gadgets?

|

21 (5.2%) 85 (21.2%) 134 (33.4%) 96 (23.9%) 65 (16.2%) |

9 39 55 46 27 |

12 46 79 50 37 |

Single major reason for using electronic gadget?

|

123 (30.6%) 114 (28.4%) 82 (20.4%) 76 (18.9%) 1 (0.2%) 2 (0.49%) 1 (0.2%) 2 (0.49%) |

71 39 32 32 0 1 0 2 |

52 75 50 44 1 1 1 0 |

| Variables | Females (n=224) Mean ± SD |

Males (n=176) Mean ± SD |

Test of significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAD-2 | 2.191± 1.545 | 1.534 ± 1.389 | t=4.412, df=398, p=0.0001 |

| PHQ-2 | 1.987 ± 1.531 | 1.721 ± 1.384 | t=1.799, df=398, p=0.0728 |

| WHO-5 | 52.035 ± 20.003 | 54.704 ± 20.022 | t= 1.983, df=398, p=0.048 |

GAD-2

|

74 (33.03%) 150 (66.97%) |

34 (19.32%) 142 (80.68%) |

Chi-square= 9.409 p=0.002 |

PHQ-2

|

68 (30.36%) 156 (69.64%) |

46 (26.14%) 130 (73.86%) |

Chi-square=0.862 p=0.353 |

| Variables | Age of the participants | Sleep latency in minutes | Hours of sleep | Procrastination time(minutes) | BtP Score | PHQ-2 Score | GAD-2 Score | WHO-5 Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep latency in minutes | R= -0.0056 P=0.937 |

** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| Hours of sleep | R= -0.0941 P=0.215 |

R= -0.044 P= 0.562 |

** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| Procrastination time(minutes) | R= -0.0822 P=0.279 |

R=0.4034 P<0.00001 |

R= -0.276 P=0.0002 |

** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| BtP Score | R= -0.396 P<0.00001 |

R=0.0242 P=0.750 |

R= -0.0614 P=0.421 |

R=0.2003 P=0.0076 |

** | ** | ** | ** |

| PHQ-2 Score | R= -0.192 P= 0.011 |

R=0.1203 P=0.1117 |

R= -0.0586 P=0.444 |

R=0.2708 P=0.0003 |

R=0.1891 P=0.0119 |

** | ** | ** |

| GAD-2 Score | R= -0.1098 P= 0.146 |

R=0.1011 P=0.181 |

R= -0.1297 P= 0.088 |

R= 0.2961 P= 0.00007 |

R=0.3561 P<0.00001 |

R=0.5769 P<0.00001 |

** | ** |

| WHO-5 Score | R=0.1021 P=0.177 |

R= - 0.246 P=0.0009 |

R=0.0469 P=0.536 |

R= -0.1948 P= 0.0095 |

R= -0.1471 P=0.0515 |

R= -0.3933 P <0.00001 |

R= -0.2971 P=0.00006 |

** |

| SISS (Sleep quality) | R=0.0505 P= 0.506 |

R= -0.2487 P=0.0009 |

R=0.1403 P=0.063 |

R= -0.3029 P=0.00004 |

R= -0.2555 P= 0.0006 |

R= -0.2362 P= 0.0016 |

R= -0.2811 P=0.00016 |

R= 0.418 P<0.00001 |

| Variables | Age of the participants | Sleep latency in minutes | Hours of sleep | Procrastination time (minutes) | BtP Score | PHQ-2 Score | GAD-2 Score | WHO-5 Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep latency in minutes | R= -0.0881 P= 0.189 |

** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| Hours of sleep | R= -0.1091 P= 0.104 |

R= -0.1573 P= 0.0187 |

** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| Procrastination time(minutes) | R= 0.0244 P= 0.716 |

R=0.1732 P=0.0094 |

R= -0.1257 P=0.0597 |

** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| BtP Score | R= -0.1518 P= 0.0229 |

R=0.1042 P=0.1199 |

R= -0.1812 P=0.0066 |

R=0.1541 P=0.0210 |

** | ** | ** | ** |

| PHQ-2 Score | R= -0.1671 P=0.0123 |

R= 0.0839 P=0.211 |

R=0.016 P=0.8117 |

R= 0.1128 P=0.0921 |

R=0.1578 P=0.0181 |

** | ** | ** |

| GAD-2 Score | R= -0.1593 P=0.0172 |

R=0.054 P=0.4212 |

R= -0.0522 P=0.4387 |

R=0.1904 P=0.0042 |

R=0.2303 P=0.0005 |

R= 0.6355 P<0.00001 |

** | ** |

| WHO-5 Score | R=0.038 P=0.572 |

R= -0.1486 P=0.0257 |

R=0.0581 P=0.3868 |

R=-0.0769 P=0.2511 |

R= - 0.2326 P=0.0004 |

R= -0.6183 P<0.00001 |

R= -0.4855 P <0.00001 |

** |

| SISS | R= -0.1335 P= 0.045 |

R= -0.1347 P=0.0435 |

R=0.3271 P<0.00001 |

R= -0.1253 P=0.0618 |

R= -0.2419 P=0.0003 |

R= -0.2163 P=0.0011 |

R= -0.3065 P<0.00001 |

R=0.3785 P<0.00001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).