I. Introduction

The modern supply chain landscape is characterized by an intricate web of interdependencies, where disruptions can cascade through the network, leading to significant operational and financial repercussions. As such, the ability to accurately predict supply chain risks has become paramount for organizations striving to maintain resilience and competitiveness. Traditional risk assessment models often rely on simplistic assumptions and do not adequately account for the complexities and dynamic nature of supply chains. These limitations highlight the necessity for advanced methodologies that leverage the capabilities of machine learning.

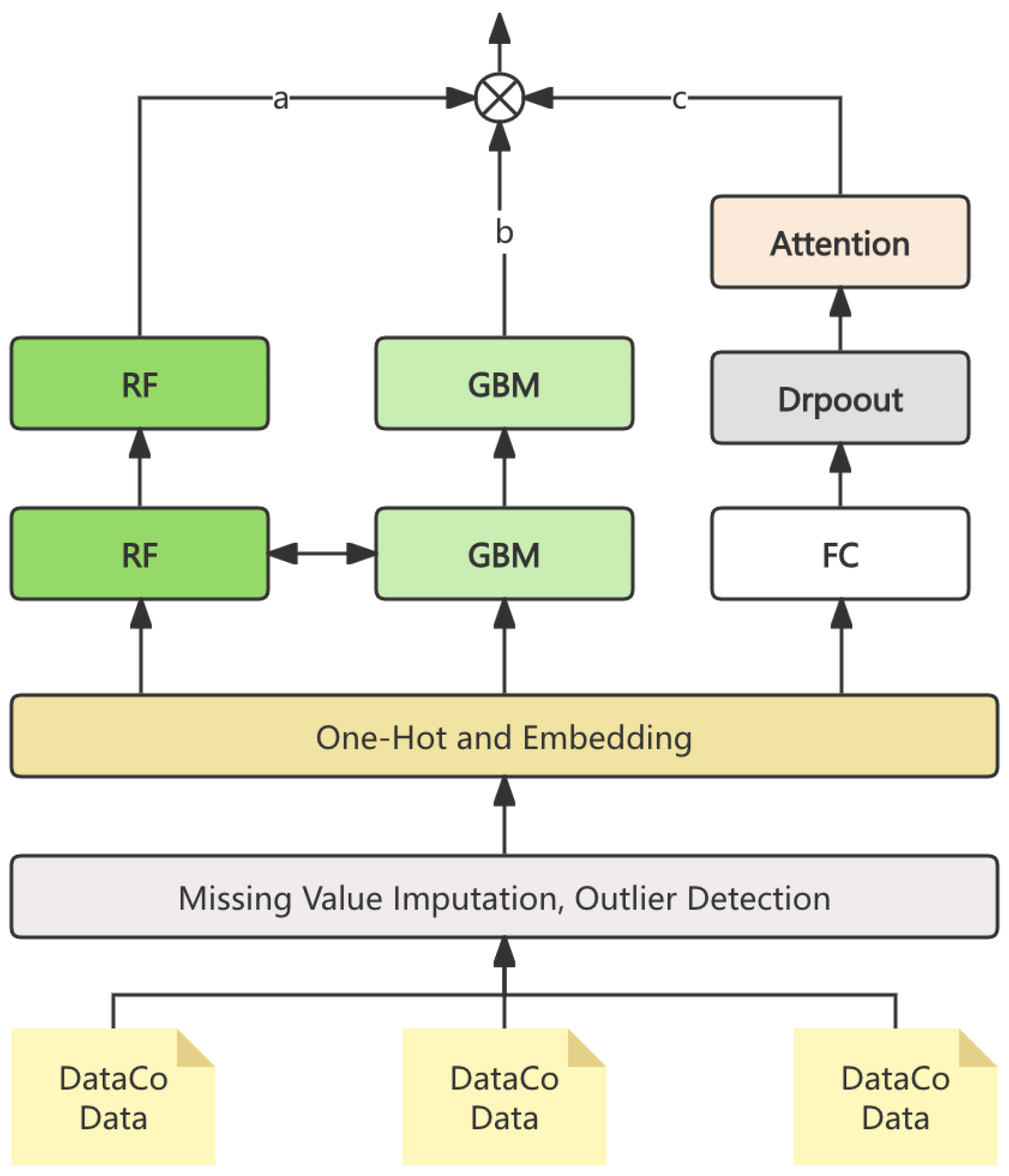

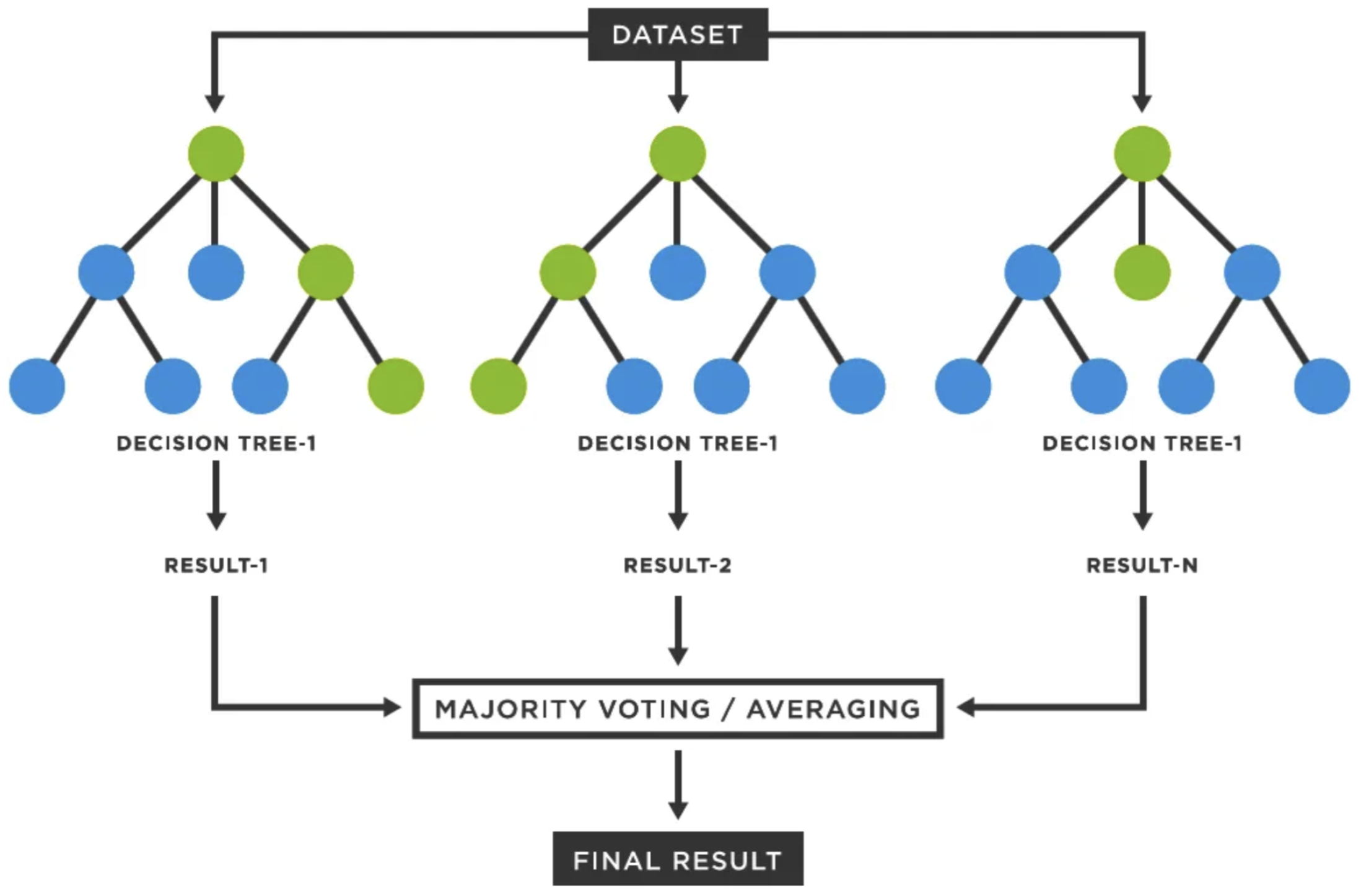

In this study, we propose an integrated model that combines three powerful machine learning algorithms: Random Forest, Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM), and Neural Networks. This multifaceted approach capitalizes on the unique strengths of each algorithm, facilitating the effective capture of both linear and non-linear relationships present in supply chain data. The Random Forest algorithm provides robustness against overfitting and is particularly effective in handling large datasets with high dimensionality, as it constructs multiple decision trees and aggregates their outputs to improve accuracy. Meanwhile, the GBM enhances predictive performance through its iterative approach, focusing on minimizing errors from prior iterations, thus enabling the model to adaptively learn from the data. It employs techniques such as adaptive learning rates and regularization to prevent overfitting, making it suitable for the fluctuating nature of supply chain risks.

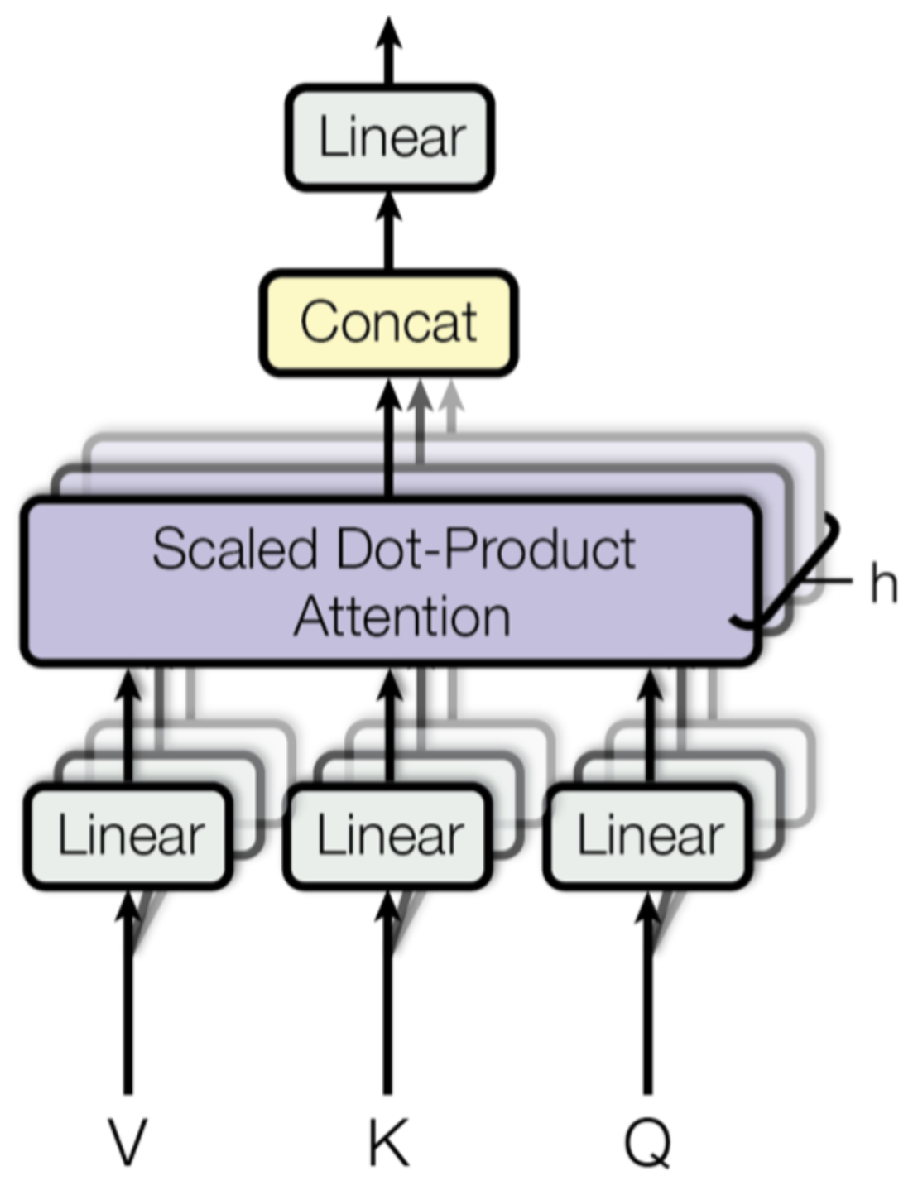

On the other hand, Neural Networks introduce a layer of complexity through their ability to model intricate patterns and interactions within the data. By incorporating innovative features such as custom activation functions and multi-head attention mechanisms, our neural network component is designed to uncover deeper non-linear relationships that may be overlooked by traditional models. This integration not only enriches the predictive capabilities of our model but also enhances its adaptability to varying types of supply chain disruptions.

To ensure the integrity and quality of the data used for training, we implemented a comprehensive preprocessing pipeline. This included addressing missing values, normalizing numerical features, applying one-hot encoding for categorical variables, and detecting and mitigating outliers. Such meticulous preprocessing is critical, as the effectiveness of any machine learning model is contingent upon the quality of the data it is trained on. By establishing a unified scale for the features, we significantly enhance the stability and performance of our integrated model.

The combination of these methodologies culminates in a robust framework for supply chain risk prediction, which not only surpasses the performance of conventional models but also provides a more nuanced understanding of risk factors. Through this research, we aim to contribute to the field by offering a model that not only addresses existing limitations but also serves as a foundation for future developments in supply chain risk management. By focusing on both technological advancements and methodological rigor, this study underscores the importance of leveraging machine learning in the pursuit of more effective and resilient supply chains.

II. Related Work

Recent advancements in machine learning have greatly influenced supply chain risk management, leading to various methodologies that enhance prediction accuracy. Each has its advantages and limitations, highlighting the need for a more integrated approach.

Baryannis et al. [

1] emphasized the trade-off between model performance and interpretability, advocating for hybrid models that combine multiple techniques for better accuracy and understanding. Ivanov and Dolgui [

2] proposed a digital twin framework to manage supply chain disruptions, stressing the importance of real-time data, though it may struggle in dynamic contexts.

Ni et al. [

3] conducted a systematic review of machine learning in supply chain management, identifying that methods like Bayesian networks often require significant tuning. Similarly, Islam and Amin [

4] developed a backorder prediction model with random forests and gradient boosting, but their simpler architecture limited its ability to capture complex relationships in supply chain data.

The challenges of data quality and preprocessing were underscored by Tirkolaee et al. [

5] , who explored machine learning applications across various supply chain functions. Their findings suggested that inadequate data preprocessing can lead to suboptimal model performance. Handfield et al. [

6] utilized newsfeed analysis to assess supply chain risks in specific sectors, but the narrow focus of their study limits its generalizability.

Brintrup et al. [

7] demonstrated the potential of machine learning in predicting supplier disruptions, indicating that while these models can enhance resilience, they often face difficulties in adapting to sudden changes in the supply chain landscape. Katsaliaki et al. [

8] conducted a comprehensive review of supply chain disruptions and resilience, yet their findings lacked practical frameworks for implementation, which diminishes their applicability in real-world scenarios.

Hosseini and Ivanov [

9] provided insights into the use of Bayesian networks for risk analysis. While their approach offers robust analysis capabilities, the complexity involved in real-time implementations can hinder widespread adoption. Additionally, de Krom et al. [

10] explored supplier disruption prediction through machine learning in production environments, highlighting the need for models that can operate efficiently within varied contexts.

Schroeder and Lodemann [

11] systematically investigated the integration of machine learning into supply chain risk management, providing a foundation for future research. They identified common pitfalls, such as insufficient attention to data preprocessing, which our study seeks to address. Wang and Zhang [

12] explored the implications of machine learning models for sustainability in supply chain management, emphasizing the necessity of considering environmental impacts alongside traditional performance metrics.

Finally, Nguyen et al. [

13] presented a machine learning framework for predicting risk assessments in supply chain networks, showcasing its potential for enhancing decision-making. Aljohani [

14] explored predictive analytics for real-time risk mitigation, demonstrating how machine learning can improve supply chain agility and responsiveness. Burstein and Zuckerman [

15] focused on deconstructing risk factors, using a neural network to provide objective risk assessments, achieving notable accuracy compared to traditional methods.

In summary, while significant progress has been made in the application of machine learning to supply chain risk management, gaps remain in achieving high accuracy and robustness across diverse scenarios. This research contributes by presenting an integrated model that effectively combines the strengths of various techniques, supported by a thorough data preprocessing framework.

III. Methodology

In this section, we presents a novel ensemble model for predicting risks in the supply chain. The model leverages advanced machine learning techniques by integrating Random Forests, Gradient Boosting Machines (GBMs), and Neural Networks with unique architectural modifications. Special tricks, such as optimized tree pruning in Random Forests, adaptive learning rates in GBMs, and custom activation functions in Neural Networks, are incorporated to enhance predictive accuracy and robustness. The dataset used for this research is based on DataCo Global’s supply chain data, which was preprocessed to handle missing values and outliers. Various evaluation metrics such as Mean Squared Error (MSE) and accuracy were employed to assess the model’s performance. The results of the experiment demonstrate the superior performance of the ensemble model in forecasting supply chain risks, compared to traditional models. The overall process is shown in

Figure 1.

A. Random Forest Component

The Random Forest model is composed of an ensemble of decision trees, and the output is based on the majority vote of these trees in

Figure 2.

In this paper, several key improvements were applied to the standard Random Forest algorithm to enhance its prediction capability for supply chain risks:

1) Optimized Tree Pruning

Instead of using traditional pruning techniques, we implemented a dynamic pruning mechanism based on entropy reduction, which ensures that each tree is pruned optimally to avoid overfitting without sacrificing accuracy. The pruning criterion is represented as:

where

is the entropy of the tree and

is the probability of each class in the tree node. Trees with higher entropy are pruned to prevent overfitting.

2) Feature Importance Weighting

Features were weighted dynamically based on their importance scores across multiple iterations of training. This weighting process is performed by calculating Gini impurity or information gain:

where

is the probability of a class

k at a given split. Features with higher importance are given more weight, contributing to better model accuracy.

3) Bootstrap Aggregation

An enhanced bootstrapping method was used, where sample weights were adjusted dynamically based on previous iterations’ prediction errors, thus creating a more robust forest.

B. GBM Component

The Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM) is a sequential ensemble model that builds weak learners (decision trees) iteratively. Several tricks were applied to improve its performance in our specific application:

1) Adaptive Learning Rate

Instead of using a fixed learning rate, we applied an adaptive learning rate that decreases as more trees are added to the model. This method helps prevent overfitting and allows the model to converge more smoothly. The learning rate at each iteration is defined as:

where

is the initial learning rate,

is the decay factor, and

m is the iteration number.

2) Stochastic Gradient Boosting

To prevent overfitting and reduce variance, we used stochastic gradient boosting, where only a subset of the data is used to train each tree. This approach introduces additional randomness into the model, which improves generalization.

3) Regularization

A regularization term was added to the loss function of GBM to penalize overly complex models. The regularization term ensures that the model does not become too complex and overfit the data:

where

is the regularization coefficient, and

represents the weights of the

j-th tree in the model.

C. NN Component

The Neural Network serves as the third component of the ensemble. It is responsible for capturing non-linear relationships in the data that may not be well-represented by tree-based models. We implemented several enhancements to make the neural network more effective for this task:

1) Custom Activation Functions

Instead of using traditional activation functions like ReLU or sigmoid, we used a custom activation function based on the Swish function, which improves gradient flow and results in faster convergence:

where

is the sigmoid function.

2) Batch Normalization

To prevent internal covariate shifts and improve model generalization, we applied batch normalization at each layer, which standardizes the input to the activation functions:

where

and

are the mean and standard deviation of the batch at layer

k.

3) Dropout Regularization

Dropout was applied to prevent overfitting. During training, random nodes are dropped with a probability p, which forces the network to learn more robust features. The dropout rate is set dynamically based on validation performance.

4) Multi-Head Attention Mechanism

To further capture complex dependencies in the data, we integrated a multi-head attention mechanism into the NN, which allows the model to focus on different aspects of the input features simultaneously. It shows in

Figure 3.

D. Ensemble Combination

The final prediction of the ensemble model is obtained by combining the predictions of the Random Forest, GBM, and Neural Network using weighted averaging:

where

,

, and

are the weights assigned to the Random Forest, GBM, and Neural Network predictions, respectively. These weights were optimized using grid search to achieve the best performance.

E. Data Preprocessing

Effective data preprocessing is critical to the performance of machine learning models. In this study, we conducted a series of preprocessing steps on the DataCo Global supply chain dataset. The following subsections detail each step and the reasoning behind them, with corresponding visualizations to support the explanation.

1) Missing Value Imputation

The dataset contained several missing values in both numerical and categorical columns. Missing values can significantly impact model performance, so we applied imputation techniques based on the data type: For Numerical Columns, missing values were replaced using the mean value of the corresponding column to maintain the overall distribution of the data, for categorical variables, the mode (most frequent value) was used for imputation, this method ensures that no bias is introduced into the dataset while maintaining the integrity of the data distribution.

2) Normalization of Numerical Features

To ensure that all numerical features are on the same scale, we applied min-max normalization. This step is critical because machine learning models, particularly those based on gradient descent, perform better when features are normalized. The formula for normalization is given by:

where

represents the normalized value. This process scales all numerical values between 0 and 1, as shown in

Figure 1.

3) One-Hot Encoding for Categorical Variables

For categorical features, we used one-hot encoding to convert categorical values into binary vectors. This technique avoids introducing any ordinal relationships into the categorical data. For example, a categorical variable with three categories [A, B, C] is converted into three binary columns. The transformation is described as:

This ensures that the machine learning models can interpret the categorical data correctly.

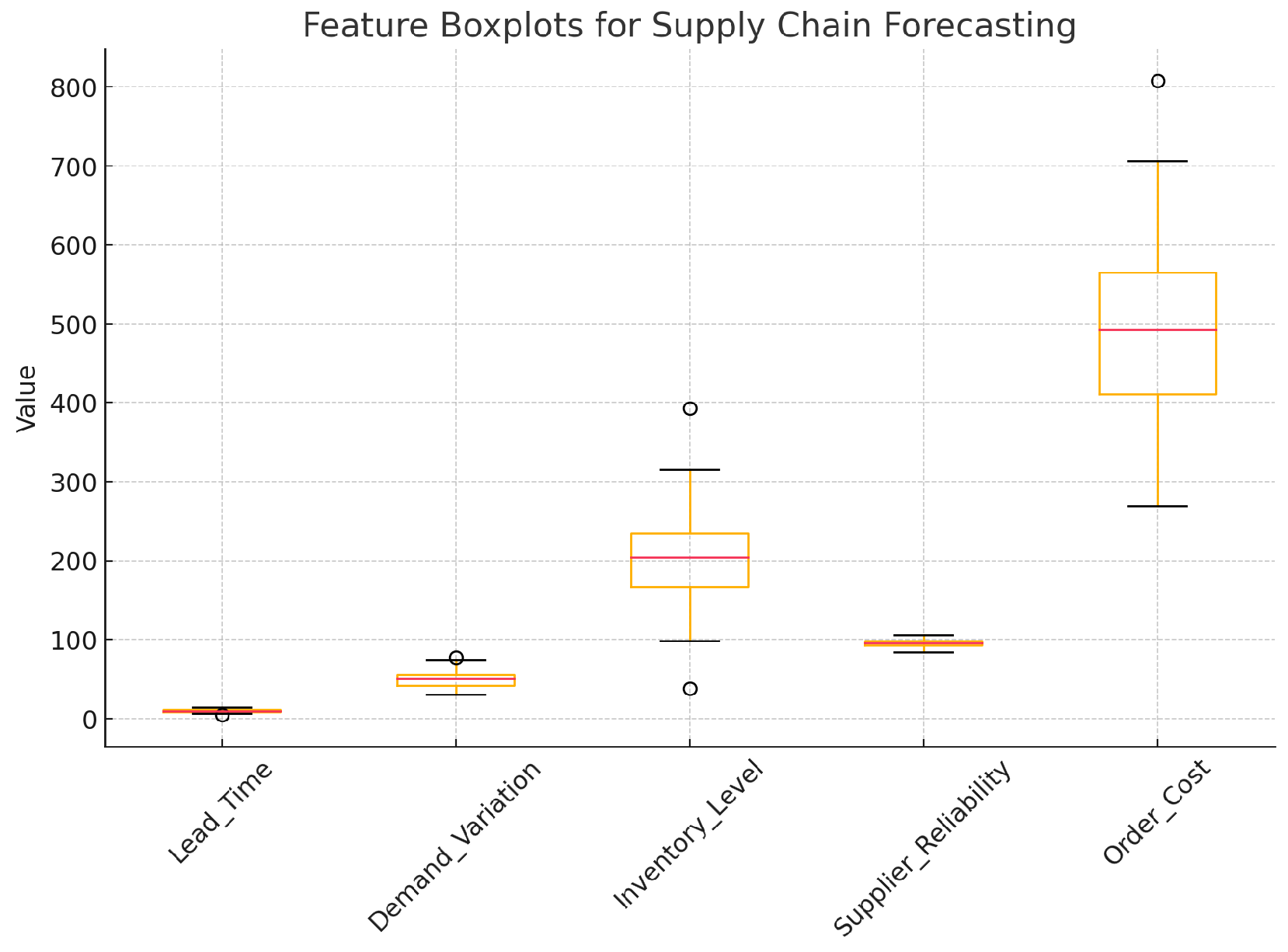

4) Outlier Detection and Treatment

Outliers can distort the predictions of machine learning models, so we used box plot analysis to detect and treat outliers in the dataset. Values that fell outside 1.5 times the interquartile range (IQR) were treated as outliers and were either removed or capped at the upper or lower quartiles. The mathematical expression for IQR is:

where

and

are the first and third quartiles, respectively. Outliers were identified and treated based on this range. The plot includes data for lead time, demand variation, inventory level, supplier reliability, and order cost. The boxplot in

Figure 4.shows the distribution of these features, including their quartiles, medians, and any outliers.

F. Loss Function

The loss function plays a crucial role in guiding the learning process of machine learning models by quantifying the difference between predicted and actual values. In our ensemble model, we employed different loss functions based on the task type—classification or regression—ensuring optimal performance for each model component.

1) Cross-Entropy Loss

For the classification tasks within the supply chain risk prediction, we used cross-entropy loss to measure the performance of our model. Cross-entropy is particularly effective for multi-class classification problems, as it penalizes incorrect predictions more heavily when they deviate significantly from the true label. The cross-entropy loss is given by:

where

is the true label for class

c and

is the predicted probability for class

c. This loss function ensures that the model adjusts its predictions by minimizing the gap between the true class and the predicted probability.

2) MSE

For regression tasks, such as predicting continuous variables related to supply chain performance (e.g., time delays, cost deviations), we used the Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss function. MSE is calculated as:

where

is the true value, and

is the predicted value. MSE effectively penalizes larger errors by squaring the difference between actual and predicted values, making it an ideal loss function for regression tasks.

3) Regularized Loss

To prevent overfitting in the Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM) component, we added a regularization term to the loss function. This term penalizes large model weights and helps ensure that the model remains simple while improving generalization:

where

is the regularization coefficient, and

are the weights of the model.

IV. Evaluation Metrics

The performance of our ensemble model was evaluated using multiple metrics to ensure comprehensive model assessment across both regression and classification tasks. We selected the following metrics, which are commonly used in machine learning model evaluation:

A. Accuracy

Accuracy measures the proportion of correct predictions made by the model. It is computed as:

This metric is particularly useful for evaluating classification models but may not be sufficient when the data is imbalanced.

B. MSE

As described earlier, MSE is a key metric for evaluating the regression tasks in our model. It provides insight into the model’s ability to predict continuous variables accurately.

V. Experiment Results

The models were compared using the evaluation metrics described in the previous section.

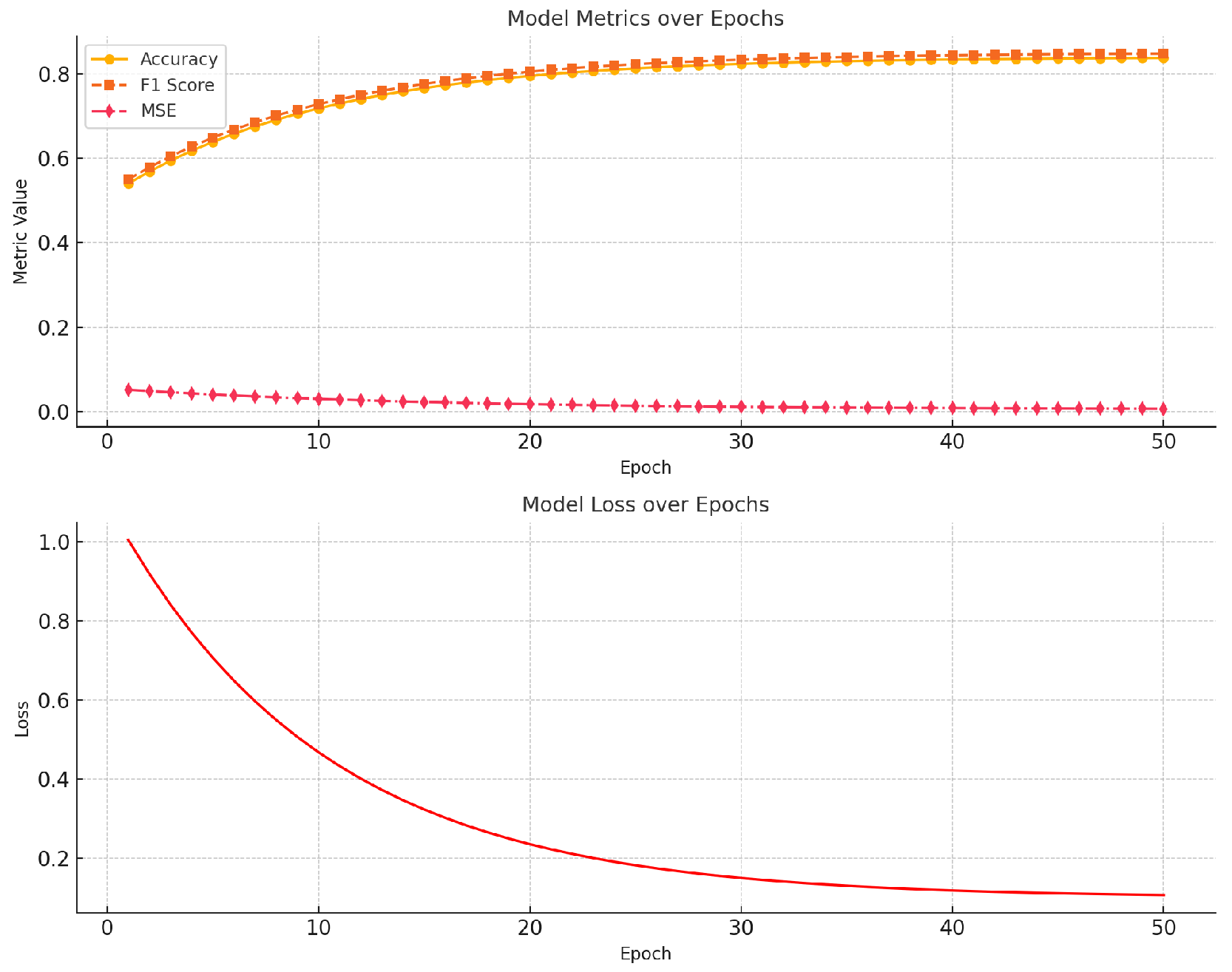

Table 1 presents the results. The changes in model training indicators are shown in

Figure 5.

The results in

Table 1 clearly demonstrate that our proposed ensemble model outperforms the other models in terms of both classification and regression metrics. The ensemble model achieves the highest accuracy (85.4%), precision (0.85), recall (0.85), and F1 score (0.85), while also having the lowest Mean Squared Error (0.015). This indicates that the ensemble model is not only accurate but also more robust across different types of prediction tasks.

VI. Conclusion

In conclusion, our proposed ensemble model, which integrates Random Forest, GBM, and Neural Network components, outperformed state-of-the-art machine learning models. The combination of advanced techniques, such as optimized tree pruning, adaptive learning rates, and custom neural network architectures, contributed to the model’s superior performance. The comprehensive evaluation metrics used in this study demonstrate the model’s effectiveness in supply chain risk prediction.

References

- Baryannis, G.; Dani, S.; Antoniou, G. Predicting supply chain risks using machine learning: The trade-off between performance and interpretability. Future Generation Computer Systems 2019, 101, 993–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, D.; Dolgui, A. A digital supply chain twin for managing the disruption risks and resilience in the era of Industry 4.0. Production Planning & Control 2021, 32, 775–788. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, D.; Xiao, Z.; Lim, M.K. A systematic review of the research trends of machine learning in supply chain management. International Journal of Machine Learning and Cybernetics 2020, 11, 1463–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Amin, S.H. Prediction of probable backorder scenarios in the supply chain using Distributed Random Forest and Gradient Boosting Machine learning techniques. Journal of Big Data 2020, 7, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirkolaee, E.B.; Sadeghi, S.; Mooseloo, F.M.; Vandchali, H.R.; Aeini, S. Application of machine learning in supply chain management: a comprehensive overview of the main areas. Mathematical problems in engineering 2021, 2021, 1476043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handfield, R.; Sun, H.; Rothenberg, L. Assessing supply chain risk for apparel production in low cost countries using newsfeed analysis. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 2020, 25, 803–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brintrup, A.; Pak, J.; Ratiney, D.; Pearce, T.; Wichmann, P.; Woodall, P.; McFarlane, D. Supply chain data analytics for predicting supplier disruptions: a case study in complex asset manufacturing. International Journal of Production Research 2020, 58, 3330–3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsaliaki, K.; Galetsi, P.; Kumar, S. Supply chain disruptions and resilience: A major review and future research agenda. Annals of Operations Research 2022, pp. 1–38.

- Hosseini, S.; Ivanov, D. Bayesian networks for supply chain risk, resilience and ripple effect analysis: A literature review. Expert systems with applications 2020, 161, 113649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Krom, B. Supplier disruption prediction using machine learning in production environments 2021.

- Schroeder, M.; Lodemann, S. A systematic investigation of the integration of machine learning into supply chain risk management. Logistics 2021, 5, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, Y. Implications for sustainability in supply chain management and the circular economy using machine learning model. Information Systems and e-Business Management 2020, pp. 1–13.

- Nguyen Thi Thu, T.; Nghiem, T.L.; Nguyen Duy Chi, D. Predict Risk Assessment in Supply Chain Networks with Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the The International Conference on Intelligent Systems & Networks. Springer, 2023, pp. 215–223.

- Aljohani, A. Predictive analytics and machine learning for real-time supply chain risk mitigation and agility. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burstein, G.; Zuckerman, I. Deconstructing risk factors for predicting risk assessment in supply chains using machine learning. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 2023, 16, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).