Submitted:

13 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

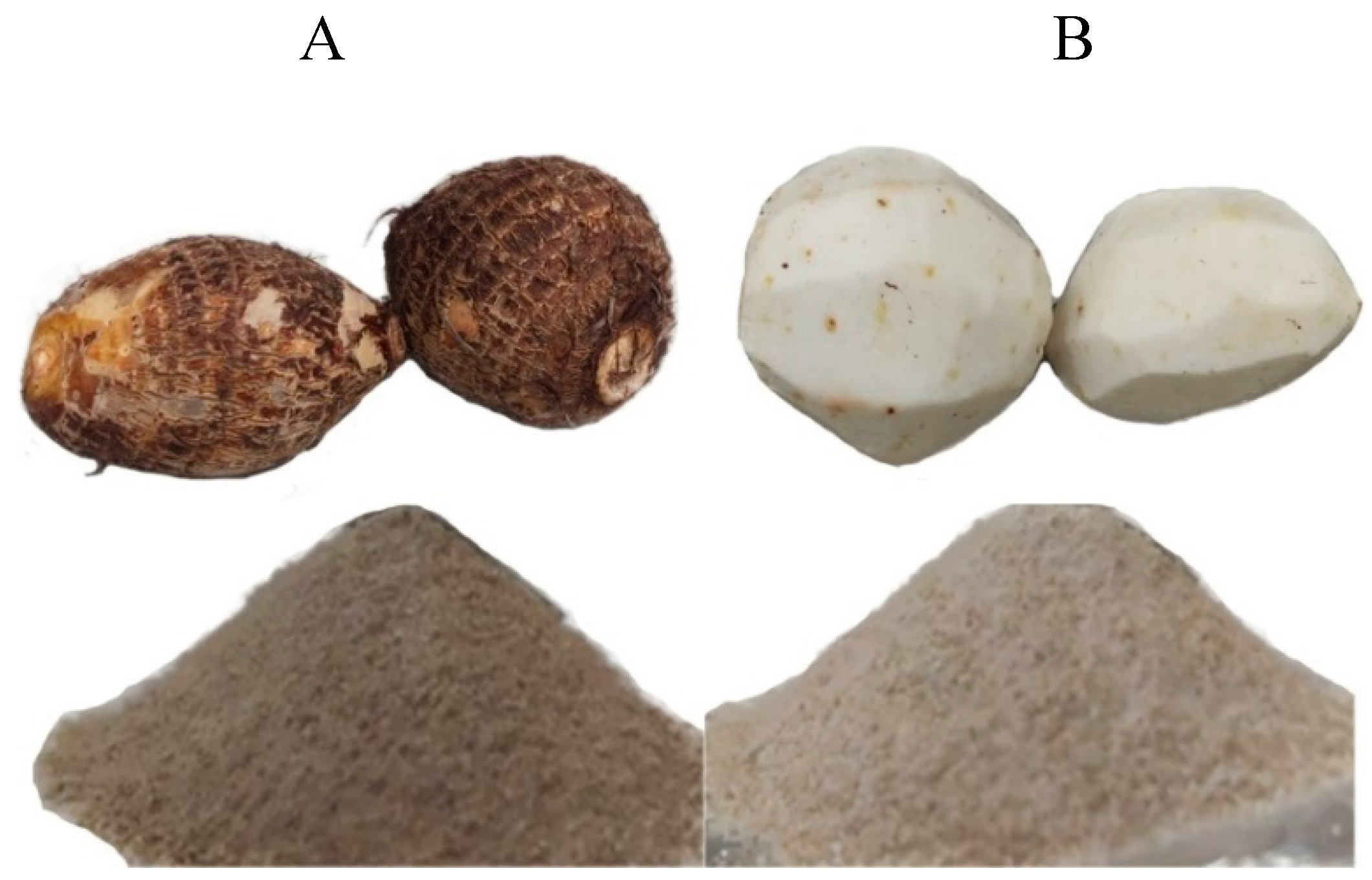

2.1. Raw Material and Fabrication of Flour

2.2. Physicochemical Characterisation of C. esculenta Flour

2.2.1. Starch Content Determination in C. esculenta Flour

2.2.2. Determination of Total Reducing Sugars

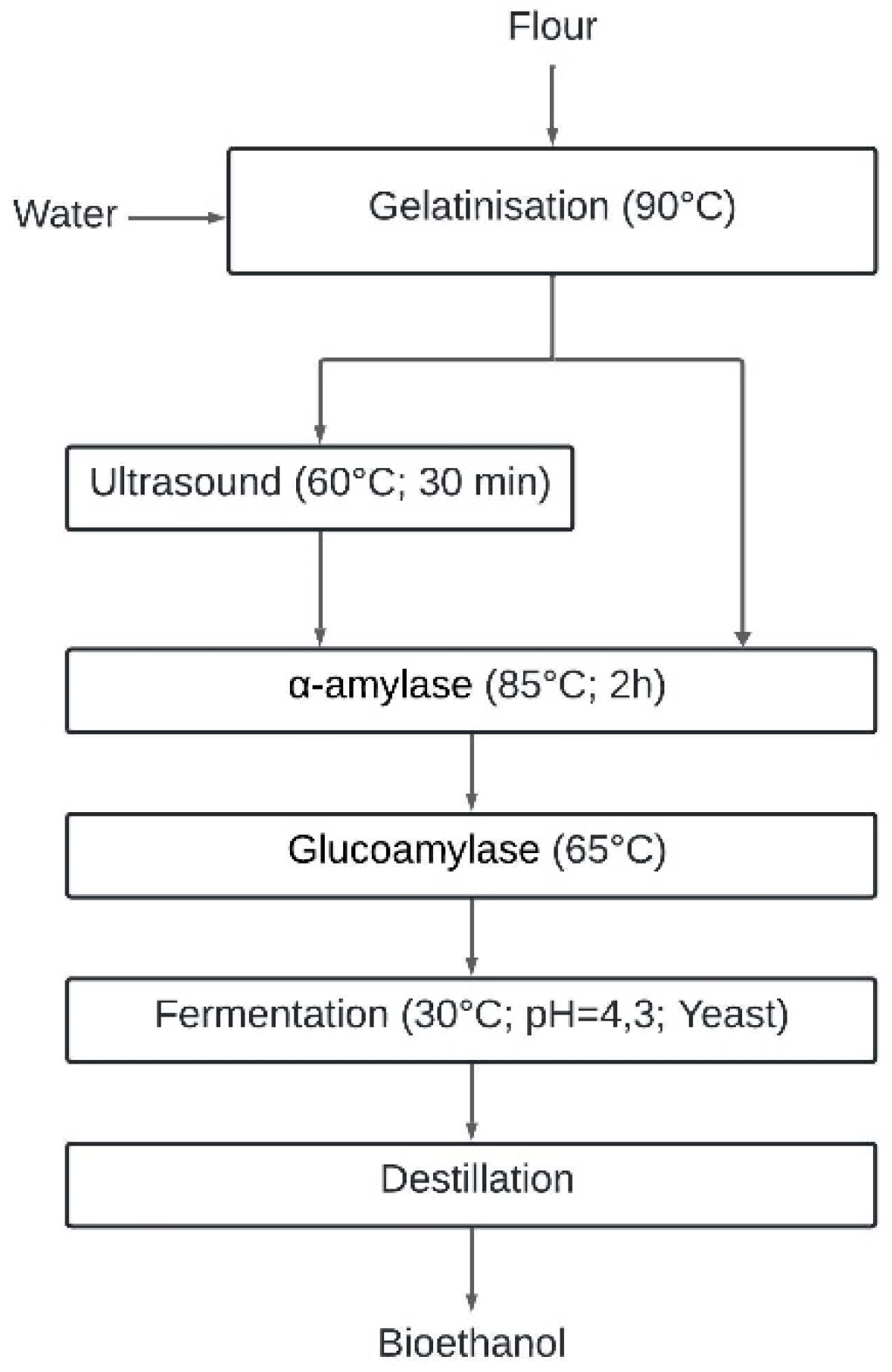

2.3. Enzymatic Hydrolysis

2.3.1. Gelatinisation

2.3.2. Enzymatic Hydrolysis

2.4. Fermentation Stage

2.5. Distillation Stage

3. Results

3.1. Chemical Characterisation of C. esculenta Flour

3.2. Evaluation of Reducing Sugars During Enzymatic Hydrolysis of C. esculenta Flour

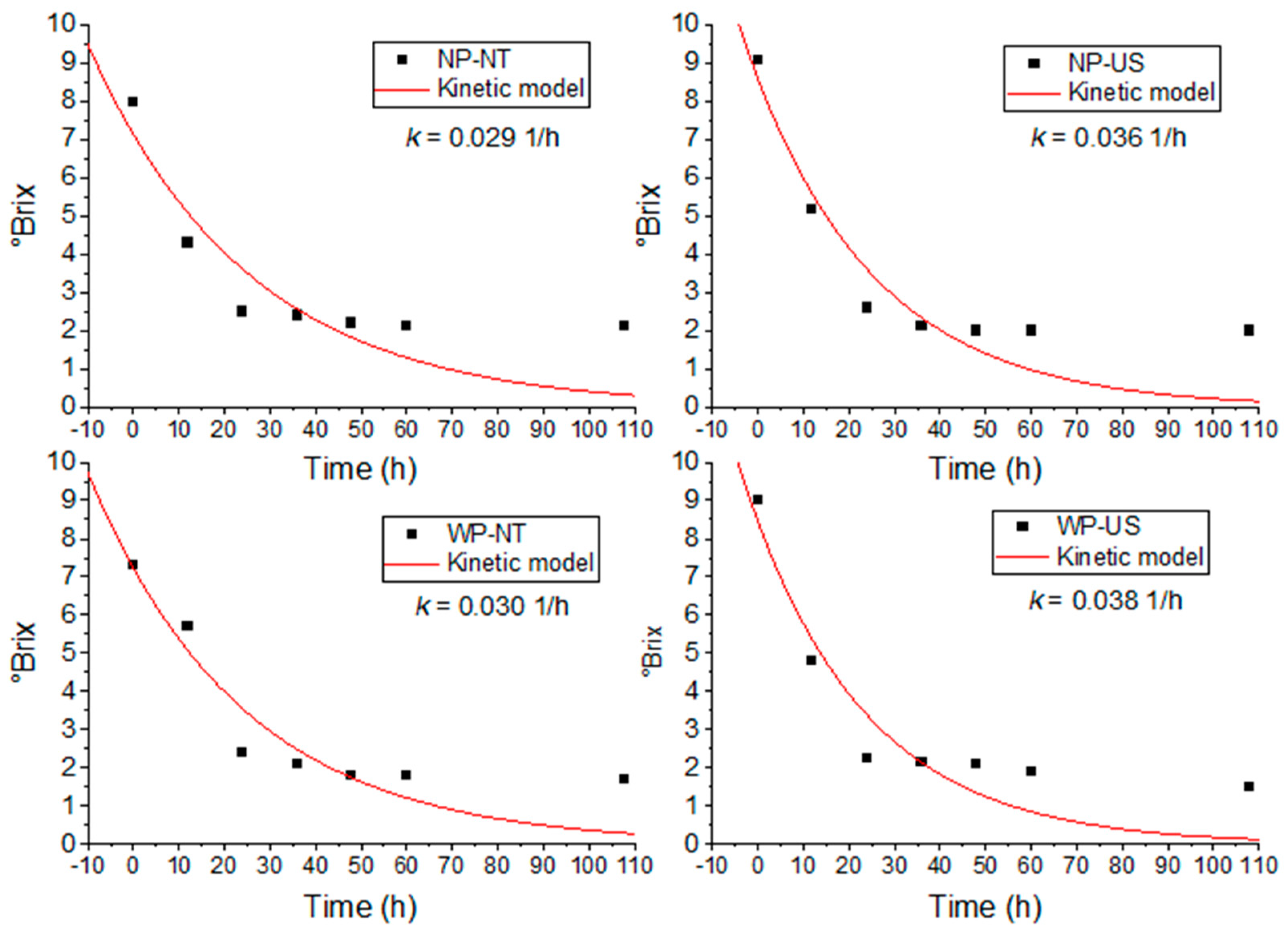

3.3. Fermentation Progress of Hydrolysed C. esculenta Flour

3.4. Ethanol Yield

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Suhara, A.; Karyadi; Herawan, S.G.; Tirta, A.; Idris, M.; Roslan, M.F.; Putra, N.R.; Hananto, A.L.; Veza, I. Biodiesel Sustainability: Review of Progress and Challenges of Biodiesel as Sustainable Biofuel. Clean Technologies 2024, 6, 886–906. [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.I.; Qasim, U.; Jamil, F.; Al-Muhtaseb, A.a.H.; Jrai, A.A.; Al-Riyami, M.; Al-Maawali, S.; Al-Haj, L.; Al-Hinai, A.; Al-Abri, M.; et al. Bioethanol and biodiesel: Bibliometric mapping, policies and future needs. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 152, 111677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, A.; Tawde, S.; Vishwas, D.; Vyas, S. A Systematic Review On Production Of Bio-Ethanol From Waste Fruits And Peels. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2024, 2, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Kumar, S. A comprehensive review of bioethanol production from diverse feedstocks: Current advancements and economic perspectives. Energy 2024, 296, 131130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabed, H.; Sahu, J.N.; Suely, A.; Boyce, A.N.; Faruq, G. Bioethanol production from renewable sources: Current perspectives and technological progress. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017, 71, 475–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parakh, P.D.; Nanda, S.; Kozinski, J.A. Eco-friendly Transformation of Waste Biomass to Biofuels. Current Biochemical Engineering 2020, 6, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abo, B.O.; Gao, M.; Wang, Y.; Wu, C.; Ma, H.; Wang, Q. Lignocellulosic biomass for bioethanol: an overview on pretreatment, hydrolysis and fermentation processes. Reviews on Environmental Health 2019, 34, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmatz, A.A.; Tyhoda, L.; Brienzo, M. Sugarcane biomass conversion influenced by lignin. Biofuels, Bioproducts and Biorefining 2020, 14, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshout, P.M.F.; van Zelm, R.; van der Velde, M.; Steinmann, Z.; Huijbregts, M.A.J. Global relative species loss due to first-generation biofuel production for the transport sector. GCB Bioenergy 2019, 11, 763–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodionova, M.V.; Poudyal, R.S.; Tiwari, I.; Voloshin, R.A.; Zharmukhamedov, S.K.; Nam, H.G.; Zayadan, B.K.; Bruce, B.D.; Hou, H.J.M.; Allakhverdiev, S.I. Biofuel production: Challenges and opportunities. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 8450–8461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulu, E.D.; Duraisamy, R.; Kebede, B.H.; Tura, A.M. Anchote (Coccinia abyssinica) starch extraction, characterization and bioethanol generation from its pulp/waste. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosalina; Maimulyanti, A.; Permana, A.H.; Sukiman, M.; Rochaeny, H.; Nurdiani. Bioethanol production using taro roots waste (Colocasia esculenta) from Bogor Indonesia and analysis of chemical compounds. Rasayan Journal of Chemistry 2022, 15. [CrossRef]

- Cataño, J.C.; Mera, I. Glucose production from cassava starch (Manihot esculenta) [Obtención de glucosa a partir de almidón de yuca Manihot sculenta]. Biotecnología en el Sector Agropecuario y Agroindustrial: BSAA 2005, 3, 54–63. [Google Scholar]

- Shyu, Y.T.; Tsai, C.C. Conversion of wax apple and taro stalk wastes to ethanol by genetically engineered escherichia coli strains. Food Biotechnology 1997, 11, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praputri, E.; Sundari, E. Production of Bioethanol from Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott (Talas Liar) by Hydrolysis Process. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2019, 543, 012056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaitanoo, N.; Junphong, A.; Chaiya, A.; Chaiwong, K.; Vuthijumnonk, J.T. Potential of Dioscorea spp. for Bioethanol Production Using Separate Hydrolysis and Fermentation Method. Philippine Journal of Science 2024, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda Mejía, J.J.; Lucio Fernández, R.E.; Caicedo Flores, J.J. Colocasia esculenta: possibilities for marketing and personal economic development [Colocasia esculenta: posibilidades de comercialización y desarrollo económico personal]. Opuntia brava 2019, 11, 354–362. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, J.; Chen, D.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, X.; Xu, L.; Guan, G.; Wang, F. Ultrasound-Assisted Enzymatic Protein Hydrolysis in Food Processing: Mechanism and Parameters. Foods 2023, 12, 4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, E.M.C.; Moreira, S.A.; Castro, L.M.G.; Pintado, M.; Saraiva, J.A. Emerging technologies to extract high added value compounds from fruit residues: Sub/supercritical, ultrasound-, and enzyme-assisted extractions. Food Reviews International 2018, 34, 581–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, B.; Tiwari, B.K.; Hossain, M.B.; Brunton, N.P.; Rai, D.K. Recent Advances on Application of Ultrasound and Pulsed Electric Field Technologies in the Extraction of Bioactives from Agro-Industrial By-products. Food and Bioprocess Technology 2018, 11, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, N.; Saha, B.C.; Hector, R.E.; Dien, B.; Hughes, S.; Liu, S.; Iten, L.; Bowman, M.J.; Sarath, G.; Cotta, M.A. Production of butanol (a biofuel) from agricultural residues: Part II – Use of corn stover and switchgrass hydrolysates. Biomass and Bioenergy 2010, 34, 566–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM-E1757-19; Annual Book of ASTM Standards. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis of Association of Official Analytical Chemists International, 22nd ed.; George W. Latimer, J., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz Sánchez, I.A.; Álvarez Reyna, V.d.P.; González Cervantes, G.; Valenzuela Núñez, L.M.; Potisek Talavera, M.d.C.; Chávez Simental, J.A. Starch and soluble protein concentration in tubers of Caladium bicolor at different phenological stages [Concentración de almidón y proteínas solubles en tubérculos de Caladium bicolor en diferentes etapas fenológicas]. Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas 2015, 6, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Q. Improving measurement of reducing sugar content in carbonated beverages using fehling’s reagent. Journal of Emerging Investigators 2020, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, F.-K.; Liu, H.; Liu, G. Physicochemical properties of starch extracted from Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott (Bun-long taro) grown in Hunan, China. Starch - Stärke 2014, 66, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, C.; Sakakibara, K.; Tanaka, S.; Kong, H. Factors affecting ethanol fermentation using Saccharomyces cerevisiae BY4742. Biomass and Bioenergy 2012, 47, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, R.C.; De Farias Silva, C.E.; da Silva, L.O.M.; Almeida, R.M.R.G.; de Oliveira Carvalho, F.; dos Santos Silva, M.C. Kinetic modelling of ethanolic fermented tomato must (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill) in batch system: influence of sugar content in the chaptalization step and inoculum concentration. Reaction Kinetics, Mechanisms and Catalysis 2020, 130, 837–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, K.; Kang, B.-U.; Park, J.-I. Improvement of Accuracy and Precision during Simple Distillation of Ethanol-Water Mixtures. World Journal of Chemical Education 2022, 10, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loi, N.V.; Binh, P.T.; Sam, V.K. Changes in physicomechanical, nutritional, and sensory indicators of taro tubers at different harvest times. Food Science and Technology 2023, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-shibly, N.M.; Roushdy, M.M. Application of Submerged Fermentation for Production of Biobutanol from Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott (Talas Liar) Peels. Egyptian Journal of Chemistry 2022, 65, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcantara, R.M.; Hurtada, W.A.; Dizon, E.I. The nutritional value and phytochemical components of taro [Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott] powder and its selected processed foods. Journal of Nutrition and Food Sciences 2013, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendek Ertop, M.; Atasoy, R.; Akın, Ş.S. Evaluation of taro [Colocasia Esculenta (L.) Schott] flour as a hydrocolloid on the physicochemical, rheological, and sensorial properties of milk pudding. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation 2019, 43, e14103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boahemaa, L.V.; Dzandu, B.; Amissah, J.G.N.; Akonor, P.T.; Saalia, F.K. Physico-chemical and functional characterization of flour and starch of taro (Colocasia esculenta) for food applications. Food and Humanity 2024, 2, 100245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acán Acán, Á.E. Effect of Temperature and pH on the Industrial Process for Bioethanol Production via Enzymatic Hydrolysis from Colocasia esculenta (Taro) [Efecto de la temperatura y pH sobre el proceso industrial para la obtención de bioetanol por hidrólisis enzimática a partir de Colocasia esculenta (Papa China)]. 2020.

- Madrigal-Ambriz, L.V.; Hernández-Madrigal, J.V.; Carranco-Jáuregui, M.E.; de la Concepción Calvo-Carrillo, M.; de Guadalupe Casas-Rosado, R. Physical and Nutritional Characterisation of Flour from the Tuber “Malanga” (Colocasia esculenta L. Schott) from Actopan, Veracruz, Mexico [Caracterización física y nutricional de harina del tubérculo de “Malanga” Colocasia esculenta L. Schott) de Actopan, Veracruz, México]. Archivos Latinoamericanos de Nutrición (ALAN) 2018, 68, 175–183. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.; Fang, Z.; Smith, R.L. Ultrasound-enhanced conversion of biomass to biofuels. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science 2014, 41, 56–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.; Jenkins, B.; Stroeve, P. Ultrasound irradiation in the production of ethanol from biomass. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2014, 40, 400–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, N.; Atif, M. Polysaccharides based biopolymers for biomedical applications: A review. Polymers for Advanced Technologies 2024, 35, e6203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subhedar, P.B.; Gogate, P.R. Intensification of Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Lignocellulose Using Ultrasound for Efficient Bioethanol Production: A Review. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 2013, 52, 11816–11828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Ma, X.; Yan, L.; Chantapakul, T.; Wang, W.; Ding, T.; Ye, X.; Liu, D. Ultrasound assisted enzymatic hydrolysis of starch catalyzed by glucoamylase: Investigation on starch properties and degradation kinetics. Carbohydrate Polymers 2017, 175, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barati, Z.; Latif, S.; Müller, J. Enzymatic hydrolysis of cassava peels as potential pre-treatment for peeling of cassava tubers. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 2019, 20, 101247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuwamanya, E.; Chiwona-Karltun, L.; Kawuki, R.S.; Baguma, Y. Bio-Ethanol Production from Non-Food Parts of Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz). AMBIO 2012, 41, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleazu, C.; Eleazu, K.; Awa, E.; Chukwuma, S. Comparative study of the phytochemical composition of the leaves of five Nigerian medicinal plants. Journal of Biotechnology and Pharmaceutical Research 2012, 3, 42–46. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolić, S.; Mojović, L.; Rakin, M.; Pejin, D.; Pejin, J. Ultrasound-assisted production of bioethanol by simultaneous saccharification and fermentation of corn meal. Food Chemistry 2010, 122, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Standard |

|---|---|

| Moisture | AOAC 934.01 |

| Ash | AOAC 942.05 |

| Crude fat | AOAC 920.39 |

| Crude fibre | AOAC 962.02 |

| Total amino acids | AOAC 994.12 |

| Total carbohydrates | AOAC 979.12 |

| Crude protein | AOAC 984.13 |

| Parameter (%) | NP | WP |

|---|---|---|

| Moisture | 6.31±0.13 1 | 6.61±0.13 |

| Ash | 5.56±0.10 | 6.33±0.14 |

| Crude fat | 5.83±0.23 | 5.91±0.06 |

| Crude fibre | 2.65±0.61 | 4.21±0.44 |

| Total amino acids | 1.60±0.00 | 1.39±0.00 |

| Total carbohydrates | 0.05±0.00 | 0.06±0.00 |

| Crude protein | 7.93±0.8 | 8.71±0.21 |

| Starch | 21.7±1.55 | 14.8±0.53 |

| Process | NP | WP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gelatinisation | 502.8b* | 503.4b | 553.2a | 552.6a |

| NT | US | NT | US | |

| α-amylase | 633.8c | 698.7b | 632.9c | 738.0a |

| Glucoamylase | 824.4c | 1016.2a | 957.4b | 1017.8a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).