Submitted:

13 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The gut microbiota interacts with the brain via the intestines and is related to diseases such as depression. Metagenome analysis, which measures bacterial genes, is commonly used in the analysis of bacterial flora. However, only a small portion of bacterial genes have known functions, and most have unknown functions, so the information is insufficient with existing analysis methods. Therefore, we developed an analysis method that combines “16S rRNA amplicon analysis data” and “prediction information obtained by database search” to enable the analysis of genes with unknown functions. Using this method, we were able to add information to the gene of bacteria with unknown functions and show part of the mechanism by which intestinal bacteria affect mouse diseases. We applied this method to the intestinal flora of mice that show hyperalgesia due to ultrasound irradiation. M. scheadleri was found to be increased in the ultrasound-irradiation group (USV). Adapting the analysis method to the M. scheadleri genome, we were able to predict the function of proteins specifically produced by M. scheadleri. The specifically produced protein may have the function of Peptidase M23 in addition to the function related to the membrane obtained by the usual search.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

2.1.1. Animals

2.1.2. Recordings of Cries

2.1.3. Von Frey Test

2.1.4. 16S rRNA Amplicon Analysis

2.2. New Application Methods to Identify the Specific Genes from Amplicon Data

2.2.1. Getting Data from NCBI RefSeq and Creating a Database

2.2.2. Classification of Bacterial-Specific Amino Acid Sequences Using BLASTP Search

2.2.3. Functional Prediction by Sequence Analysis Using PSI-BLAST and InterPro Search

2.2.4. Functional Prediction of Protein-Protein Interactions Using Clusters Based on Gene Neighborhood

2.2.5. Gene Ontology Enrichment Analysis by DAVID

3. Result

3.2. Analysis of Bacterial Genome Data Result

3.2.1. Classification of Bacterial-Specific Amino Acid Sequences Using BLASTP Search

3.2.2. Functional Prediction by Sequence Analysis Using PSI-BLAST and InterPro Search

3.2.3. Functional Prediction of Protein-Protein Interactions Using Clusters Based on Gene Neighborhood

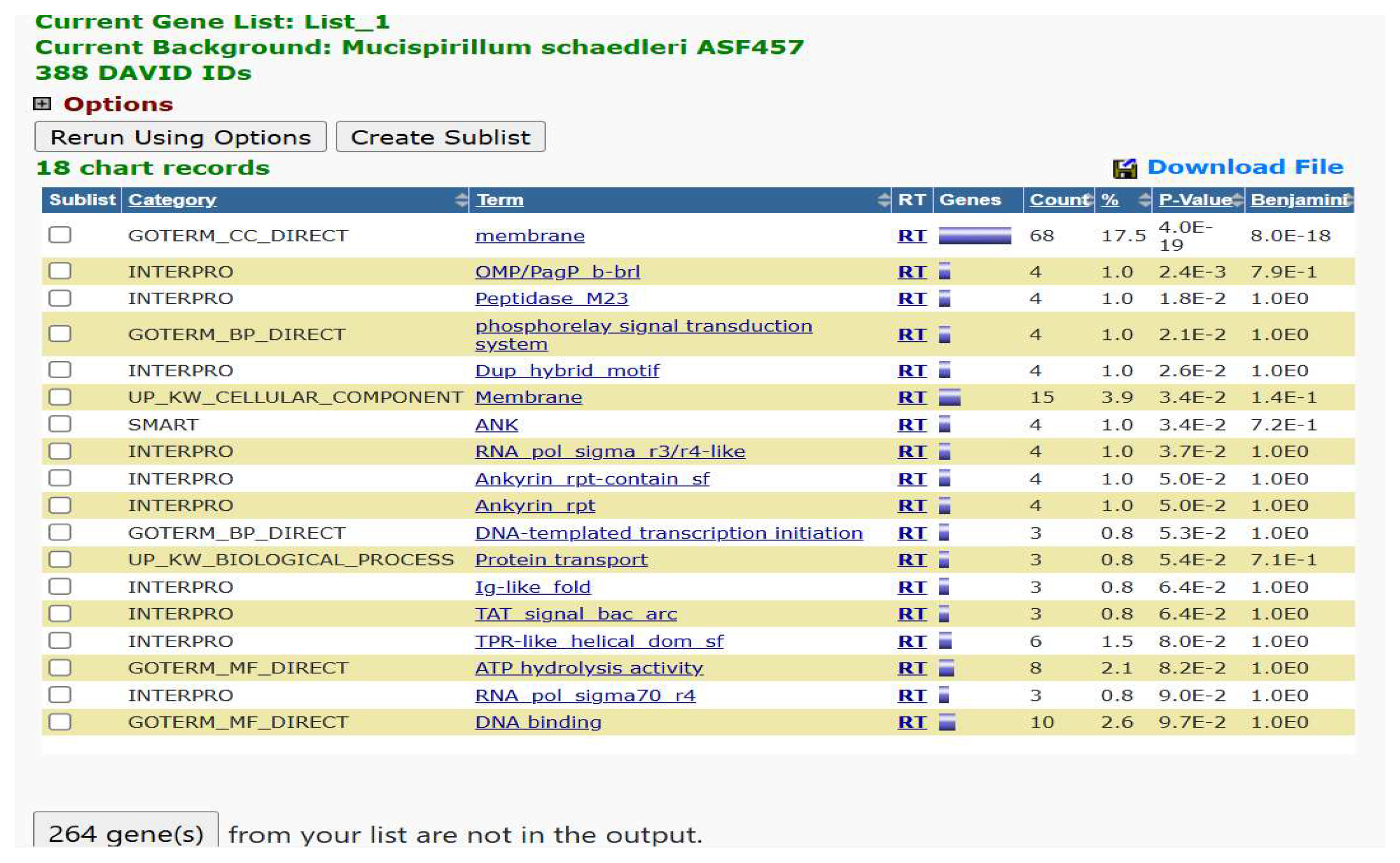

3.2.4. Gene Ontology Enrichment Analysis by DAVID

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dethlefsen, L.; McFall-Ngai, M.; Relman, D. An ecological and evolutionary perspective on human–microbe mutualism and disease. Nature 2007, 449, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neish, A.S. Microbes in gastrointestinal health and disease. Gastroenterology 2009, 136(1), 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaser, M.J.; Musser, J.M. Bacterial polymorphisms and disease in humans. J. Clin. Invest. 2001, 107(4), 391–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New, F.N.; Brito, I.L. What Is Metagenomics Teaching Us, and What Is Missed? Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 74, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mande, S.S.; Mohammed, M.H.; Ghosh, T.S. Classification of metagenomic sequences: methods and challenges. Brief Bioinform. 2012, 13(6), 669–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, G.M.; Maffei, V.J.; Zaneveld, J.R.; Yurgel, S.N.; Brown, J.R.; Taylor, C.M.; Huttenhower, C.; Langille, M.G.I. PICRUSt2 for prediction of metagenome functions. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38(6), 685–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wemheuer, F.; Taylor, J.A.; Daniel, R. Tax4Fun2: prediction of habitat-specific functional profiles and functional redundancy based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. Environ. Microbiome 2020, 15, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, V.; Lock, A.; Harris, M.A.; Rutherford, K.; Bähler, J.; Oliver, S.G. Hidden in plain sight: what remains to be discovered in the eukaryotic proteome? Open Biol. 2019, 9(2), 180241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, A.A.K.; Shanmughavel, P. Computational Annotation for Hypothetical Proteins of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. J. Comput. Sci. Syst. Biol. 2008, 1, 50–62. [Google Scholar]

- Sanmukh, S.G.; Paunikar, W.N.; Meshram, D.B.; Ghosh, T.K. In silico Function Prediction for Hypothetical Proteins in Vibrio Parahaemolyticus Chromosome II. Data Min. Knowl. Eng. 2011, 3, 404–432. [Google Scholar]

- Rajadurai, C.P.; Subazini, T.K.; Kumar, G. An Integrated Re-Annotation Approach for Functional Predictions of Hypothetical Proteins in Microbial Genomes. Curr. Bioinform. 2011, 6, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazandu, G.K.; Mulder, N.J. Function Prediction and Analysis of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Hypothetical Proteins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 7283–7302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, W.G.; Ross, S.A. Ultrasound Increases the Rate of Bacterial Cell Growth. Biotechnol. Prog. 2003, 19, n.p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Premoli, M.; Memo, M.; Bonini, S.A. Ultrasonic vocalizations in mice: relevance for ethologic and neurodevelopmental disorders studies. Neural Regen. Res. 2021, 16(6), 1158–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amplicon, P.C.R.; P.C.R. Clean-Up; P.C.R. Index. 16s Metagenomic Sequencing Library Preparation. Illumina: San Diego, CA, USA, 2013; p. 21.

- O’Leary, N.A.; Cox, E.; Holmes, J.B.; Anderson, W.R.; Falk, R.; et al. Exploring and retrieving sequence and metadata for species across the tree of life with NCBI Datasets. Sci. Data 2024, 11(1), 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Leary, N.A.; Wright, M.W.; Brister, J.R.; Ciufo, S.; Haddad, D.; et al. Reference sequence (RefSeq) database at NCBI: current status, taxonomic expansion, and functional annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44(D1), D733–D745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinform. 2009, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Madden, T.L.; Schaffer, A.A.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25, 3389–3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Binns, D.; Chang, H.Y.; Fraser, M.; Li, W.; et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 2014, 30(9), 1236–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paysan-Lafosse, T.; Blum, M.; Chuguransky, S.; Grego, T.; et al. InterPro in 2022. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51(D1), D418–D427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Xiong, W.; Wang, Y.; Guan, J. Protein Function Prediction Based on PPI Networks: Network Reconstruction vs Edge Enrichment. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, n.p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogozin, I.B.; Makarova, K.S.; Murvai, J.; Czabarka, É.; et al. Connected gene neighborhoods in prokaryotic genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30(10), 2212–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Kirsch, R.; Koutrouli, M.; Nastou, K.; et al. The STRING database in 2023: protein–protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51(D1), D638–D646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, B.T.; Panzade, G.; Imamichi, T.; Chang, W. DAVID ortholog: An integrative tool to enhance functional analysis through orthologs. Bioinformatics 2024, btae615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herp, S.; Durai Raj, A.C.; Salvado Silva, M.; Woelfel, S.; Stecher, B. The human symbiont Mucispirillum schaedleri: causality in health and disease. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2021, 210(4), 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, B.R.; O’Rourke, J.L.; Neilan, B.A.; et al. Mucispirillum schaedleri gen. nov., sp. nov., a spiral-shaped bacterium colonizing the mucus layer of the gastrointestinal tract of laboratory rodents. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2005, 55, 1199–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herp, S.; Brugiroux, S.; Garzetti, D.; et al. Mucispirillum schaedleri Antagonizes Salmonella Virulence to Protect Mice against Colitis. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 25, 681–694.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, J.O.; Hellstrom, P.M.; Lundberg, J.M.; Alving, K. Greatly increased luminal nitric oxide in ulcerative colitis. Lancet 1994, 344, 1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, I.I.; et al. Expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase and nitrotyrosine in colonic epithelium in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 1996, 111, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enocksson, A.; Lundberg, J.; Weitzberg, E.; Norrby-Teglund, A.; Svenungsson, B. Rectal nitric oxide gas and stool cytokine levels during the course of infectious gastroenteritis. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2004, 11(2), 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, S.E.; Winter, M.G.; Xavier, M.N.; Thiennimitr, P.; Poon, V.; et al. Host-derived nitrate boosts growth of E. coli in the inflamed gut. Science 2013, 339(6120), 708–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werbner, M.; Barsheshet, Y.; Werbner, N.; Zigdon, M.; et al. Social-Stress-Responsive Microbiota Induces Stimulation of Self-Reactive Effector T Helper Cells. mSystems 2019, 4(4), e00292-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Echeverria-Villalobos, M.; Tortorici, V.; Brito, B.E.; Ryskamp, D.; Uribe, A.; Weaver, T. The role of neuroinflammation in the transition of acute to chronic pain and the opioid-induced hyperalgesia and tolerance. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1297931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Lei, Q.; Zou, X.; Ma, D. The role and mechanisms of gram-negative bacterial outer membrane vesicles in inflammatory diseases. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1157813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanaja, S.K.; Russo, A.J.; Behl, B.; Banerjee, I.; Yankova, M.; et al. Bacterial Outer Membrane Vesicles Mediate Cytosolic Localization of LPS and Caspase-11 Activation. Cell 2016, 165(5), 1106–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Kim, H.; Lee, J.H.; et al. Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4): new insight immune and aging. Immun. Ageing 2023, 20, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razew, A.; Schwarz, J.N.; Mitkowski, P.; Sabala, I.; Kaus-Drobek, M. One fold, many functions—M23 family of peptidoglycan hydrolases. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1036964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovács, K.J.; Papic, J.C.; Larson, A.A. Movement-evoked hyperalgesia induced by lipopolysaccharides is not suppressed by glucocorticoids. Pain 2008, 136(1–2), 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, W.G.; Ross, S.A. Ultrasound increases the rate of bacterial cell growth. Biotechnol. Prog. 2003, 19(3), 1038–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Deng, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Y.; et al. Isolation, identification, and proteomic analysis of outer membrane vesicles of Riemerella anatipestifer SX-1. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103(6), 103639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loy, A.; Pfann, C.; Steinberger, M.; Hanson, B.; Herp, S.; et al. Lifestyle and Horizontal Gene Transfer-Mediated Evolution of Mucispirillum schaedleri, a Core Member of the Murine Gut Microbiota. mSystems 2017, 2(3), e00171-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaly, V.; Anyango, S.; Deshpande, M.; Nair, S.; et al. AlphaFold Protein Structure Database: massively expanding the structural coverage of protein-sequence space with high-accuracy models. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50(D1), D439–D444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions, and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions, or products referred to in the content. |

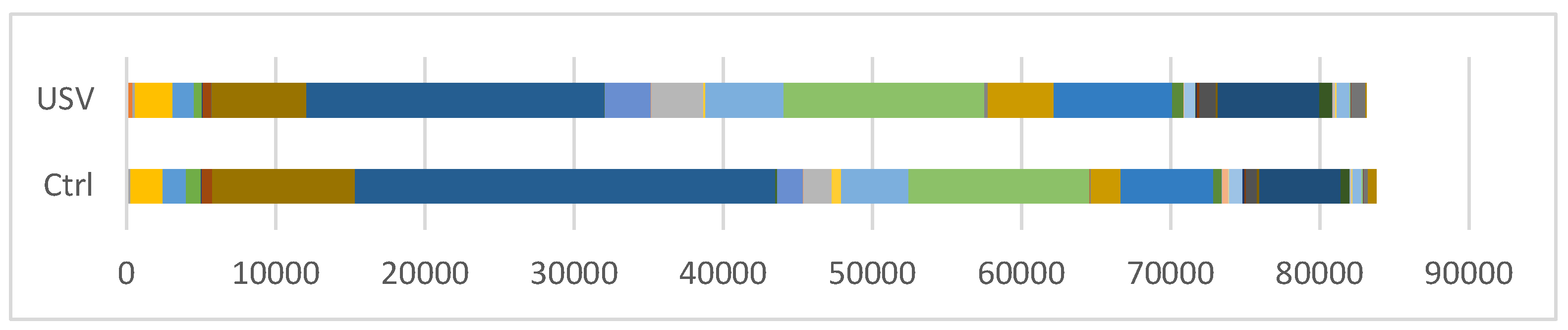

| Organisms | C. colinum | D. C21_c20 | P. distasonis | B. pullicaecorum | R. gnavus | B. acidifaciens | M. schaedleri | total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ctrl read counts | 11 | 37 | 65 | 133 | 912 | 1563 | 1970 | 83774 |

| USV read counts | 0 | 13 | 64 | 106 | 685 | 1448 | 3505 | 83116 |

| Ctrl ratio (%) | 0.013 | 0.042 | 0.078 | 0.159 | 1.089 | 1.866 | 2.232 | |

| USV ratio (%) | 0 | 0.016 | 0.077 | 0.128 | 0.824 | 1.742 | 4.217 | |

| p-value | 9.10.E-04 | 7.43.E-04 | 9.65.E-01 | 9.15.E-02 | 2.81.E-08 | 5.78.E-02 | 0.00.E+00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).