1. Introduction

1.1. Overview of Paper

The first part of this paper is principally a review of Artificial Intelligence (AI), from its origins to its status today, and its current and likely mid-term usage in aviation settings. The second part tracks the evolutionary trajectory of Human Factors as it developed to focus both on cognition and automation in aviation, aiming to form a safe and effective human-automation partnership in workplaces such as cockpits and air traffic control centres and towers. The third part of this paper derives a detailed set of Human Factors Requirements for future AI-based systems in which there will be a working partnership – task and goal-sharing – between humans and AI. The fourth part illustrates the application of the requirements set to an aviation research use case. The fifth and final section concludes on the utility of the approach and the most urgent Human Factors research needed to prepare for more advanced AI systems yet to come.

1.2. AI – The New Normal or Déjà Vu?

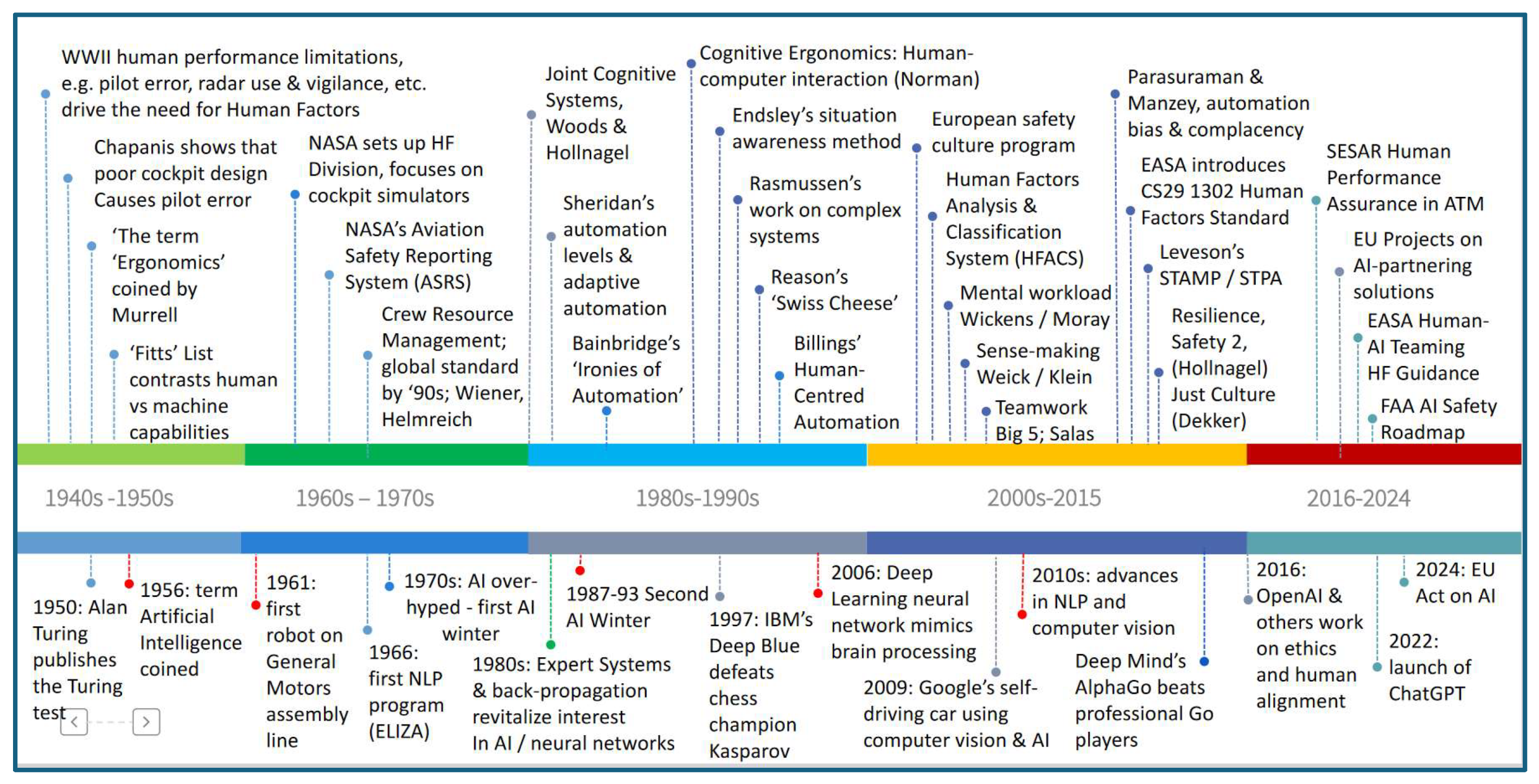

Artificial Intelligence (AI) may feel new to many, but it has a relatively long history as illustrated in

Figure 1, dating back to the 1950s [

1,

2] and arguably even back to the 19

th Century via Charles Babbage’s counting machines [

3]. AI initially had the goal of replicating certain human cognitive abilities, albeit with more reliability. Hence the fundamental notion of computation, of ‘crunching the numbers’, which humans could do given enough time, but rarely error-free. As computing power grew, it soon surpassed what humans could do even given infinite time, and with the advent of deep learning [

4], it could sometimes derive novel solutions to problems that we would never have thought of. Thus, the goal of AI shifted from replicating human cognitive capabilities to surpassing them.

The AI timeline in

Figure 1 shows that many inventions or initiatives believed generally to be relatively recent, have in fact been around for a long time, including robots, natural language processing, neural networks, computer vision and even self-driving cars. However, many of these were prototypes, and did not go ‘mainstream’ until recently (robot assembly for car manufacture being a notable exception) [

5].

As

Figure 1 also shows, AI has already experienced two ‘AI winters’, where its promise vastly exceeded its delivery, leading to an investment and technological cliff edge, so that AI largely disappeared for a while from the public eye [

6,

7]. But as computing power increased by orders of magnitude, and as Machine Learning approaches began to show their worth and earn their keep, AI once again caught the public’s attention, as well as attracting both brilliant minds and eye-watering levels of investment. The public release of ChatGPT [

8] and other Generative AI (hereafter called GenAI) systems in 2022 transformed AI from being a technophile, jargon-imbued subject to being a workplace and even household commodity. Even if most people have little idea of how AI works, they know that it can do things for them, whether helping their research, finishing or finessing a report, or providing a diagnosis of their health symptoms. Though many have experienced first-hand the errors and biases of GenAI systems, they accept the trade-off between its accessibility and instant power to answer questions and requests, against the occasional inaccuracies or plausible fabrications called hallucinations [

9].

Will this current AI phase result in yet another AI winter, or will the increasingly ubiquitous usage of AI become the new normal? There are already signs that GenAI is reaching its limits and not going as far as had been hoped, resulting in a minor decline in the massive investment seen in the past couple of years, But for many applications it is likely to be ‘good enough’, and recent research suggests that Large Language Models (LLMs) are performing better in certain areas, e.g. ChatGPT 4.0 vs ChatGPT 3.5 in the medical domain [

10]. Doubtlessly, new checks and balances need to be put in place to counter the inevitable quality gaps in its output, including knowing how to ask questions to get robust answers [

11], and how to integrate AI more effectively into 'messy' organisational settings such as hospitals [

12], but its immediacy as a generalised resource will be too appealing for many to give up. Although the long term societal and cultural ramifications of this shift to an AI-assisted society are yet to emerge, AI is therefore likely here to stay.

1.3. The Current AI Landscape

A definition of Artificial Intelligence pertinent to this paper is as follows [

13]:

“…the broad suite of technologies that can match or surpass human capabilities, particularly those involving cognition.”

Most AI systems today represent what is known as Narrow AI [

14], namely AI-based systems and services focused on a specific domain such as aviation, typically using Machine Learning (ML). In ‘normal’ programming, e.g. for automation, a machine is programmed exactly what to do and, given stable inputs, that is exactly what it will do. The code may be complex, but is completely explainable, at least to a software analyst or data scientist.

Machine Learning is different, because it learns autonomously, e.g. via statistics and mathematical programming [

4] to analyse data sets often called ‘training data’, where the data have been ‘labelled’ by humans (‘supervised learning’). Some ML approaches do not require labelled data (unsupervised learning), and these may be even more opaque to human scrutiny. In essence, the ML system learns through experience with ‘training data’ (and/or human supervision) and gradually becomes better at whatever task it has been set to do. The ‘code’, or the way the ML works, is still explainable, but probably only to a data scientist. ML is used to extract knowledge or insights from very large amounts of data, often to then be used for operational purposes or for forecasting events e.g. aircraft diversion requirements around thunderstorms [

15].

Deep Learning [

4] goes a step further, because the AI finds its own statistical or algorithmic ‘reasoning’ to develop a solution, based on a lot more data, and data that are unlabelled. Deep Learning therefore does not require human supervised learning. The more levels there are in Deep Learning, or hidden layers’ in neural networks, the more unfathomable such systems become.

Machine Learning can develop models and predictions that perhaps, given enough time, humans could do. Deep Learning is different and can come up with solutions humans likely would never think of. That said, Deep Learning typically uses artificial neural networks, themselves inspired by the way human brains work. Deep Learning is used for some of the more complex human cognitive processes we take for granted, such as natural language processing [

16] and image recognition [

17], and also for tackling complex problems such as finding cures for intractable diseases [

18] (see [

19] for a general summary of contemporary AI application areas).

Machine learning and Deep Learning are both seen as

‘Narrow AI’ [

14], as their focus is narrowly defined in a domain or sub-domain. As such, Narrow AI supports humans in their analysis, decision-making and other tasks. In cases where tasks are well-specified and predictable, it can execute its functions without human intervention, and with minimal supervision.

The hallmark of Generative AI (GenAI) tools, such as ChatGPT, Google Gemini and DALL-E, are that they can create new content that is often indistinguishable from human-generated content. They utilise deep learning neural networks trained on vast datasets, and natural language processing to render interaction with human users smoother. Large Language Models (LLMs) like ChatGPT can respond instantly to any query. Whether the response is a valid or correct one is another matter.

The point about ML, Deep Learning and GenAI is that these systems are still ‘crunching the numbers’, and in the case of LLMs they are predicting the next word in a sequence. Nowhere is there understanding, or a mind, or thought. They may be very useful, but they are all essentially ‘idiot savants’ [

14]. The problem is that particularly with advanced LLMs, it can feel to the user as if they are interacting with a person. This can matter in a safety critical environment and is returned to later in this paper.

Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) does not yet exist but is predicted to emerge in the coming decades, e.g. by 2041 [

20]. It would effectively comprise a mind capable of independent reasoning and could therefore in theory attain sentience. AGI would be able to set its own goals, and its intelligence could grow very rapidly to eclipse that of human beings [

21]. Whilst the step from GenAI to AGI may seem small, given the way LLMs such as ChatGPT respond instantly and can summarise vast swathes of knowledge, in practice the step is huge. AGI would likely require a different computing architecture, and it is not known how to inculcate a sense of self (putting aside for the moment the question of why we would want to do that), which may be a prerequisite for AGI, since reflexive thought is a hallmark of intelligence. For the rest of this paper, therefore, AGI is ignored, as it may never be realised.

What could exist in a relatively short timeframe are ‘

Intelligent Assistants’ (IAs) or ‘Digital Colleagues’, as envisaged by the concept of Human-AI Teaming, also called Human Autonomy Teaming, both using the same acronym HAT see [

22,

23,

24]. The essential nature of HAT, which differentiates it from automation, is the idea of an IA having a degree of autonomy/agency such that it can have intent, form goals and decisions, and execute such decisions, in collaboration with a human agent. Such IAs therefore could, in the coming decade, collaborate with and converse with pilots and air traffic controllers in operational settings. These IAs are still Narrow AI (ML, including Deep Learning) with or without Natural Language Processing capability. They would not be GenAI, at least not now in the current legal framework in Europe given the EU Act on AI [

25] and would certainly not constitute AGI. Early examples of HAT prototypes include cockpit support for startle response [

26], determining safe alternate airports due to severe weather degradation [

22]; delivering air traffic control sector workload prognoses [

23]; cockpit management of unstable approaches [

27,

28]; single pilot operations [

29]; and ATC support for landing/arrival sequencing [

30]. For a general overview of review of recent research in AI assisting air traffic operations see [

31].

1.4. AI Levels of Autonomy – The European Regulatory Perspective

Given that Intelligent Assistants (IAs) are intended to interact and collaborate with humans in aviation contexts, there is clearly an increase in their autonomy compared to automation simply presenting information and warnings. This shift in degree of autonomy affects the relationship between the human and the AI-based automation in two ways. First, the information or advice, or even executive action, can be based on calculations that are opaque to the end users (e.g. pilots), because the level of complexity and transparency of how AIs derive their answers mean that no amount of theoretical training for pilots will enable them to follow the AI’s ‘reasoning’, unless an additional layer of such ‘explainability’ is afforded to the pilot by the AI-based automation. The pilot must therefore come to trust the IA, or its advice will be rejected. Second, the role of the pilot is affected, because currently the pilot is always in command and ready (i.e. trained) to take over in case the automation (e.g. automatic landing) fails. The fundamental notion of collaboration suggests an inter-dependence, that such control becomes to a greater or lesser degree shared between human and AI.

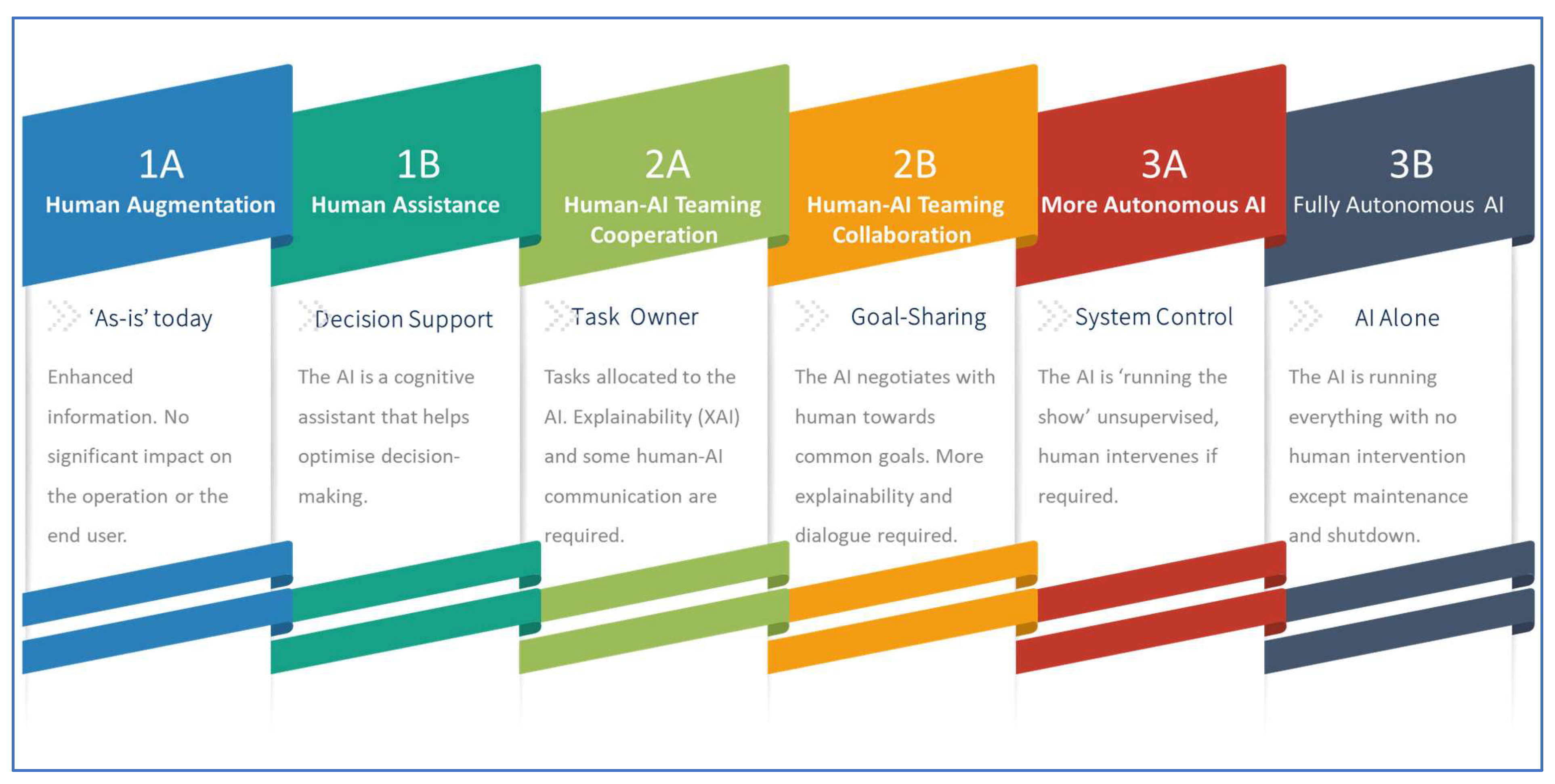

It is therefore useful to map the degree of AI autonomy, and autonomy sharing between human and AI. Increasing levels of autonomy can be represented on a scale, and the most influential scale in aviation currently is that provided by the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). Recent guidance on Human-AI Teaming (HAT) from the EASA [

32] envisages six categories of future Human-AI partnerships, illustrated in

Figure 2:

1A – Machine learning support (already existing today)

1B – cognitive assistant (equivalent to advanced automation support)

2A – cooperative agent, able to complete tasks as demanded by the operator

2B – collaborative agent – an autonomous agent that works with human colleagues, but which can take initiative and execute tasks, as well as being capable of negotiating with its human counterparts

3A – AI executive agent – the AI is basically running the show, but there is human oversight, and the human can intervene (sometimes called management by exception)

3B – the AI is running everything, and the human cannot intervene.

It has been argued that AI innovation, for all its benefits, is essentially ‘just more automation’ supporting the human operator [

33]. The critical threshold in AI autonomy where this may no longer hold appears to be between category 2A and 2B [

34,

35], since this is different from what we have today in civil aviation cockpits. The distinction between 2A and 2B is clarified by EASA as follows, including what each one is and is not [

35]:

There are currently no [AI-based] civil aviation systems that autonomously share tasks with humans, and can negotiate, make trade-offs, change priorities and initiate and execute tasks under their own initiative. Even for ‘lesser’ autonomy levels such as 1B to 2A, and also for 3A, there is the opacity issue, wherein the AI’s are akin to ‘black boxes’, and as such may surprise, confound or confuse the end users, because most end users will not be able to follow the computations underpinning AI advice. This leads to the raison d’etre of this paper, namely that AI and IAs represent something novel, and as such, conventional automation interface design and Human Factors approaches may not be sufficient to assure the safe use and acceptability of such systems. At the very least, issues such as roles and responsibilities, trust in automation and situation awareness will have additional significant nuances that may require augmentation of existing approaches. Furthermore, new issues such as operational explainability of AI systems may require completely new approaches or design requirements.

In order to determine what is needed from Human Factors, it is useful to briefly review Human Factors as a whole, over its seventy years history, to see how it has developed into its current capability set, in order to better understand what needs to be added to accommodate new AI-based systems and, in particular, Intelligent Assistants.

2. The Human Factors Landscape

In order to consider what is required from Human Factors for future AI-based systems, it is useful to briefly chart the evolution of Human Factors in aviation, including Human Factors approaches to increasing automation in the cockpit and elsewhere. This helps show where we are now, and where we may have to go. It is also helpful as some of the stages Human Factors has passed through over the past seventy years may be worth revisiting and updating to account for AI interactions.

2.1. The Origins of Human Factors

WWII was arguably the forge from which human performance partnering with technology first came to the fore. It was noted that many aircraft losses were due to ‘pilot error’, and that the new role of radar operators was susceptible to vigilance failures due to low signal-to-noise ratios. It is important to appreciate that prior to Human Factors, it was generally believed that mistakes and errors could be avoided by training, professionalism, motivation and strength of character. Yet even when these were in abundance, WWII showed resoundingly that ‘good men’ can make simple mistakes when interacting with technology, that cost them and others their lives. There was a pressing need for a way to avoid high attrition rates due to ‘human error’. Drills and drums on the battlefield, when rifles and bayonets were the main weapon, were no longer sufficient when warfare involved complex machinery in the form of aircraft fighters and bombers, warships, submarines, and radar control stations.

During the war Alphonse Chapanis, a lieutenant in the army, showed that much of pilot error related to cockpit design (e.g. locating the landing gear control next to the bomb release control, resulting in a number of tragic mishaps on landing). His work showed how better design could reduce pilot error [

36,

37,

38]. Similarly, studies of radar operators revealed that despite the best motivation, signals would be missed if that radar operators worked beyond certain periods. The lessons learned from human performance under sometimes extreme stress were brought together under a new domain known as Ergonomics in the UK [

36], and Human Factors or Human Factors Engineering in the US [

38], denoting the study of humans at work. The term Ergonomics is derived from the Greek word for work,

ergon. Ergonomics / Human Factors primarily constitutes a fusion of three disciplines: psychology, physiology and engineering.

2.2. Key Waypoints in Human Factors

Human Factors and Ergonomics have always focused largely on human work and the workplace. As highlighted in

Figure 1, Human Factors started out with a focus on physical ergonomics and on the layout of cockpit instruments and controls, for example. By the 1980s and 1990s the focus had shifted to cognitive ergonomics, in parallel with the fact that many work situations involved computing and automation. As work complexity grew, constructs such as situation awareness and mental workload came to the fore, and as automation became the norm, there was a corresponding need to consider complacency and bias, as well as a move from a focus on human error to system resilience. Arguably these developments over time have prepared Human Factors for the next major step change in the guise of the rise of AI.

This section therefore details key milestones and themes in Human Factors over the past seven decades that have helped application domains such as aviation achieve and sustain very high levels of safety. These are the principal focal areas and capabilities of Human Factors that need to be preserved, revisited (or even resurrected), or updated in the context of AI, and will form the basis of a comprehensive Human Factors Requirements set for AI-based systems. Each milestone is outlined below, with one or more key references, along with the implications for Human Factors assurance of future Human-AI Teaming systems in aviation.

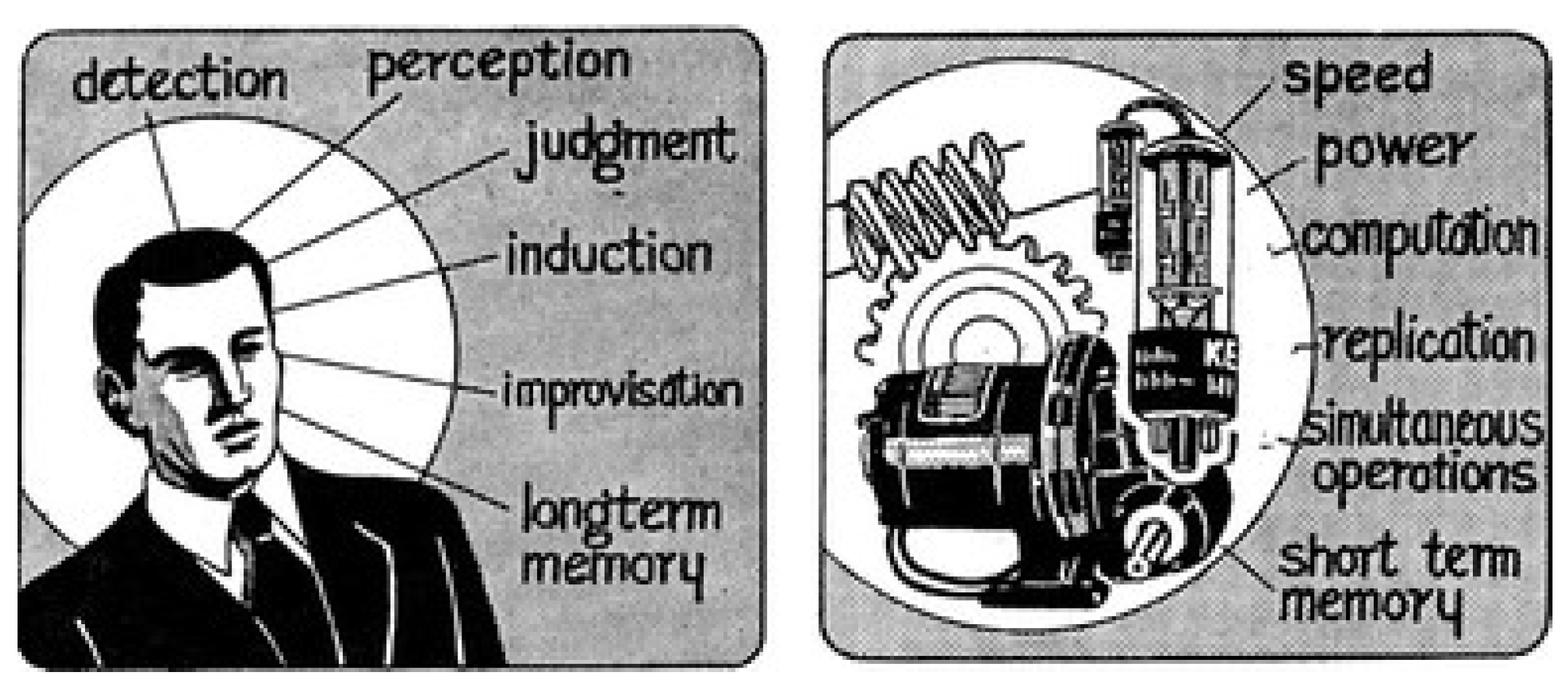

2.2.1. Fitts’ List

One of the first landmark achievements was the development of a contrasting list of what machines are good at, versus what humans are good at. This was developed by Paul Fitts and is perennially known as Fitts’ List [

39,

40] (see

Figure 3). Notably at the time, most of the cognitive ‘heavy lifting’, including pattern recognition and interpretation of ‘noisy’ data was left to the human. A more recent analysis [

41] showed that the distinction between man and machine’s relative capabilities has shifted or at least blurred. Given the current and intended prowess of AI-based systems, it would be useful to update this list given the advent of AI, and clarify where humans are still preferred, where AI should ‘go it alone’, and where AI-augmented human performance is the optimal solution.

2.2.2. Aviation Safety Reporting System

Human Factors was given a boost when NASA created a Human Factors group to contribute to the Apollo missions. At around that time the Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS) was set up by the FAA and NASA (

https://asrs.arc.nasa.gov/). ASRS collected data on safety-related events (e.g. mistakes made by pilots), guaranteeing pilots immunity (with a few exceptions) from prosecution if they reported. ASRS was possibly a stroke of genius, as it provided a constant wellspring of viable information about what was not working in the cockpit or on the ground. ASRS created a continuous feedback loop that has run in parallel with the inexorable increase of the role of technology in the cockpit.

If (when) AI begins to be used operationally in the cockpit or ATC Ops Room or Control Tower, the immunity issue (strongly related to Just Culture – see later) may need to be revisited, as AI-based systems may automatically report anomalies or deviations from the norm. This notion is already embedded in incoming law in Europe, via the EU Act on AI, for safety-critical settings. ASRS and equivalent systems (e.g. ECCAIRS in Europe [

https://aviationreporting.eu/en]) would also likely need additional categories to capture AI-related characteristics of events, and errors that arise from Human-AI Teaming operations (see HFACS, later).

2.2.3. Crew Resource Management

Crew Resource Management [

42] (originally called Cockpit Resource Management), was to become one of the major contributions of Human Factors to aviation safety. CRM gave flight crews the means to become more resilient against human errors and teamwork problems, and complemented ongoing work to make the cockpit design itself less error prone. The need for CRM grew from the world’s worst civil aviation air disaster at Tenerife airport in 1977 but was also linked to United Airlines Flight 173 air crash in 1978 [

43]. Both accidents highlighted team and communication errors, and the need for specific training on leadership, decision-making and communication on the flight deck, and with air traffic control (which in Europe later developed its own version of CRM called Team Resource Management or TRM [

44]). CRM focuses on proper use of the available human resources in operational teams and has spread to other domains such as maritime via Bridge Resources Management (BRM) or Maritime Resources management (MRM) [

45]. CRM remains strong today, and is currently in its 6

th generation, and continues to be a mainstay in aviation Human Factors and aviation safety.

The resilience of flight crews and air traffic controllers in the face of abnormal, challenging, time-critical situations is essential to safety in today’s complex, high-tempo operations. If AI-based systems begin to play a role in either cockpit or ATC workplaces, or significantly support flight crew/ATCOs, potential impacts on CRM/TRM need to be understood and safeguards put in place. This will be particularly the case with Intelligent Assistants at EASA category 2A or 2B, where flight crew and the IA are sharing tasks and even negotiating over how best to achieve goals.

2.2.4. Human-Centred Design & Human Computer Interaction

The 1980s heralded some of the key paradigms of Human Factors, and is generally considered to be the epoch wherein Human Factors and Ergonomics became more ‘cognitive’ in their approach. Norman’s landmark work on design [

46] reflected the ubiquitous rise of computer usage in aviation and other industrial domains, and ushered in a lasting focus on human-computer interaction (HCI) and the benefits of human-centred design (HCD) [

47]. It also contributed to the development of the broader and still flourishing field of Usability [

48].

Human-AI interaction, whether via keyboard, speech or other media, will be critical for the safe and effective introduction of AI-based systems into operational aviation contexts. A superordinate Human-Centred Design approach to the development and validation of Human-AI Teaming solutions would facilitate the principles of both human agency and human oversight [

49]. Many HCI and Usability requirements will probably still apply to AI-based interfaces and interaction, with the proviso that new requirements may well be needed for a human-AI speech interface via natural language processing (NLP) as well as operational explainability (OpXAI) to help the user understand the AI’s decision-making processes [

50]. Explainability is likely to be a major new area for Human Factors research.

2.2.5. Joint Cognitive Systems

Joint Cognitive Systems (JCS) [

51] and Cognitive Systems Engineering (CSE) [

52] introduced the concept of a cognitive system as an adaptive system that functions using knowledge about itself and the environment in the planning and modification of actions. CSE sought to side-step the man-vs machine paradigm and consider the cognitive output of both working together. With its focus on the joint cognitive picture emerging from the agents in the system (man/machine), it paved the way for Situation Awareness (see later). Its focus on examining work

in situ, rather than in the lab, and its focus on more naturalistic examination of decision-making scenarios (aka naturalistic decision-making [

53]), also paved the way for Safety II and Resilience movements in Human Factors. JCS was perhaps ahead of its time, but surely has renewed relevance with the advent of AI-based systems and the concept of shared (i.e. between human and AI) situation awareness. Given that JCS / CSE are about coordination, unsurprisingly they also drew together a range of different disciplines, forming a hybrid community comprising Computing/Data Science, Systems Engineering and Systems Thinking, Human Factors, Neuro-Science and Social Sciences (including Psychology). Such a hybrid community approach would probably benefit Human-AI Teaming design and development.

2.2.5. Ironies of Automation

At around the same time, Bainbridge [

54] published her seminal ‘Ironies of Automation’ article, which highlighted some of the key dilemmas of human-automation pairing that still exist today and are relevant to human-AI pairing. As an example, as automation increases, human work can require exhausting monitoring tasks, so that rather than needing less training, operators need to be trained more to be ready for the rare but crucial interventions. In particular, Bainbridge and her colleagues stated the case that automation is often given precedence, while humans are left to do the things that automation can’t do, including stepping in when the automation can no longer deal with the current conditions, or simply fails. The importance of the

Ironies is that they act as checks and balances for system designers, with warnings about certain design philosophies and pathways that tend not to work, leading instead to endemic system performance problems and drawbacks.

This approach warrants updating in the context of AI. Endsley [

55] has already begun the process, but it needs updating in the context of LLMs as well as ML systems, and in particular for Human-AI Teaming scenarios.

2.2.6. Levels of Automation & Adaptive Automation

Sheridan was one of the key proponents of ‘levels of automation’, which can be seen as an alternative or complement to Fitts’ List. His ten levels of automation [

56,

57] run from fully manual to fully automated:

The computer offers no assistance, human must take all decisions and actions

The computer offers a complete set of decision/action alternatives, or

Narrows the selection down to a few, or

Suggests one alternative, and

Executes that suggestion if the human approves, or

Allows the human a restricted veto time before automatic execution

Executes automatically, then necessarily informs the human, and

Informs the human only if asked, or

Informs the human only if it, the computer, decides to

The computer decides everything, acts autonomously, ignores the human

Sheridan’s work also contributed to the notion of adaptive automation [

58], wherein, for example, the automation could step in when (or ideally, before) the human became overloaded in a work situation. However, there is always the danger that as automation fails, the flight crew once again encounter the primary irony of automation and are left to fend for themselves when they most need support. Adaptive automation/autonomy usefully parsed human-machine interactions into four categories: 1) information acquisition; 2) information analysis; 3) decision and action selection; and 4) action implementation. It proposed that levels of autonomy (from high to low) could exist in each of these categories. This thinking has influenced EASA’s six categories, and is inherently useful, for example, in suggesting that machines/automation/AI can advise pilots, but the pilot takes the final action, or makes the final decision (thus maintaining a critical degree of ‘agency’).

Adaptive automation has never quite realised the success it had hoped for, but with AI it is clearly a prospective area where adaptive automation could work and bring benefits. Both ‘halves’ of adaptive AI would be needed. The first is the detection of a situation where the demands on the human are excessive, whether due to external demands such as air traffic intensity, or internal factors such as fatigue or startle response. The second is the ability to take over certain tasks in a way that would be acceptable to, and managed/supervised by, the humans in charge. The earlier-mentioned case study on startle response [

26] is effectively AI-supported adaptive automation, detecting startle and then directing the pilot’s attention to key display components to stabilise the aircraft.

Adaptive automation suggests the need for a number of requirements, including how to protect the role and expertise of the human, how to switch from human to AI and back again as required. Adaptive automation also raises ethical issues in terms of data protection, e.g. if AI components such as neural networks use real-time human performance data (EEG, heart rate, galvanic skin response, etc.) as inputs to determine when to take over. Pilots may have concerns over the measurement and recording of such data, as it could reflect on their medical fitness for duty, a pilot licensing requirement.

2.2.7. Situation Awareness, Mental Workload & Sense-Making

Prior to Situation Awareness as a Human Factors construct, there were (and still remain) related concepts such as vigilance and attention [

59], born from the early study of WWII radar display operators (and later, air traffic controllers) and the ability to detect signals such as incoming missiles or aircraft, given that the signal-to-noise ratio was low, and given both time-on-task and fatigue. Whereas attention and vigilance can be considered to be states related to alertness or arousal, situation awareness tends to be more contextualised, e.g., awareness of elements in the environment, such as aircraft in a sector of airspace.

Situation Awareness (SA) therefore focused less on the state of cognitive arousal, and more on the detail of what the human was aware of and what it meant for the current and future operation. Indeed, the principal SA method, the Situation Awareness Global Assessment Technique (SAGAT, [

60]) focused on three time-frames: past, current and future (the latter also known as prospective memory). As complexity rose in human-plus-automation environments such as cockpits and air traffic control centres, the question became how well the human understood what was going on, what was going to happen in the near future, and how to act. The next question became how much the pilot or air traffic controller could assimilate from their controls and displays, in both short timeframes and longer durations. This led to the study of mental workload (MWL), considering the task demands vs. human capabilities and capacities, including problems of overload and underload [

59,

61].

SA and Mental Workload signalled a deepening of the focus on cognitive activities, relating them in a measurable fashion to the actual cognitive work and operational context, delivering viable metrics that could be measured in simulations. Both SA and MWL have become mainstays in the design, validation and operation of human-operated aviation systems. They are useful constructs because they help designers determine what the flight crew need to know (and see/hear), and when, and in what sequence and priority order, and when users may be overloaded. However, the perception of what is happening (and going to happen) to an object may be insufficient when the AI is processing its inputs; the human may need to understand what is behind the AI output.

More recently, this delving into mental processes has focused on

sense-making, which is the way people make sense out of their experience in the world [

62]. Sense-making deals with the human need to comprehend, often via the exploration of information. In relation to AI, sense-making helps to test the plausibility of an AI’s explanations as well as anomalous outputs or event characteristics. Sense-making is a useful construct particularly in conditions where uncertainty is high and not all signals may be present, or else some signals may be erroneous. Unfortunately, for such situations, as can happen in flight upsets, there is no straightforward associated metric to determine how easily flight crew will be able to make sense of a particular scenario. Instead, realistic simulations are carried out with pilots undergoing non-nominal events, and SA measurements and post-simulation debriefs, as well as safety and aircraft performance measures, are the best way to determine the safety of the cockpit design or air traffic control system.

There is a very real danger that AI systems, which tend to be ‘black boxes’, can undermine the human crew’s situation awareness, both in terms of what is going on, and of what the AI is doing or attempting to do. A critical question therefore becomes how to develop an interface and interaction means so that the AI and the human can remain ‘on the same page’. This is not a trivial matter.

Additionally, there will need to be operational explainability (OpXAI), so that the human crews can determine (i.e. make sense of) why a course of action has been recommended (or taken) by the AI. Such explainability needs to be in an operational context in language that crews can follow (as opposed to data analytic explainability, which refers more to how to trace an AI’s outputs to its internal architecture, data sources and algorithmic processes).

Workload will become more nuanced with human-AI teaming partnerships, as there may be more periods of underload followed by intense workload periods, especially if the AI is suddenly unable to function.

Realistic and real-time simulations with human crews as occur now, both for flight crew and air traffic controllers, should continue. These will become human-plus-AI simulations. The human crews need to see how AI works in realistic contexts, so they can gain trust in it. They also need to see it when it fails or becomes unavailable, so that they can recover from such scenarios. Low SA, plus a sudden spike in mental workload due to loss of the AI support, and an inability of the AI to explain its recommendations, could well be a recipe for disaster.

2.2.8. Rasmussen & Reason – Complex Systems, Swiss Cheese, and Accident Aetiology

Rasmussen’s work on complex systems and safety, underpinned by his Skill, Rule and Knowledge-Based Behaviour hierarchy [

63], had a big impact in the 80’s and 90’s in many high-risk industry domains. It may be worth revisiting this model as there are undoubtedly skill-sets that may be lost (this already happens with automation), and rules (e.g. Standard Operating Procedures [SOPs] in cockpits) may become more fluid as AI-based support systems find ever-new ways of optimising operations in real-time. Perhaps most interesting will be the area of knowledge-based behaviour (KBB), namely having to consider what is going on in a situation based on a fundamental understanding of how the system works and responds to external and internal perturbations. KBB incorporates not only factual knowledge (also called declarative knowledge) but experience amassed over years of operating a system (e.g. an aircraft) in a wide range of conditions.

KBB can be supported by ecological interface design [

64], resulting in high level displays to monitor critical functions or safety parameters, as were developed in the nuclear power domain to avoid misdiagnoses of nuclear emergencies. Since AI operational explainability can probably never be completely trustworthy, an interface that affords the pilot or other aviation worker an effective system safety overview, unfiltered by AI, would seem a sensible precaution. Moreover, since diagnosis of an aircraft emergency may become a shared human-AI process, the question is one of how to ensure that no human ‘tunnel vision’ or misdiagnosis by an AI leads to catastrophe. A deeper question becomes how to visualise AI performance so that it is evident to the human when the AI is outside its own knowledge base or has limited certainty about its prognosis.

Reason’s so-called Swiss Cheese model of accident aetiology (see

Figure 4) [

65], although dated, is still in regular use today. It proposes that accidents occur via vulnerabilities in a succession of barriers (e.g. organisation, preconditions, [un]safe acts and defences). The vulnerabilities are like the holes in Swiss cheese, and the larger or more proliferated they are, the easier it is for them to ‘line up’ and for an accident to occur. What is interesting is that AI could in theory affect all these layers, either increasing or decreasing the size and quantity of the holes. It could also reduce the independence between each barrier, so that in reality a system has fewer barriers before an accident occurs.

It would be useful to consider how AI could affect the Swiss Cheese layers differentially, e.g. use of LLMs at the organisational and preconditions layers, and AI-based tools at the unsafe acts and defences layers. Such a layered model also leads to the question of how different AIs will interface with each other. We already talk of Human-AI Teaming, but there will also be Human-AI-AI-Human and Human-AI-Human-AI variants before long, potentially allowing for problems to propagate unchecked across traditional ‘defence-in-depth’ boundaries.

2.2.9. Human Centred Automation

In the 1990s, after a series of ‘automation-assisted aviation accidents’ following the introduction of glass cockpits, Billings [

66] developed the concept of Human Centred Automation. This tradition has generally persisted in aviation ever since. The nine core principles of HCA are as follows:

The human must be in command

To command effectively, the human must be involved

To be involved, the human must be informed

The human must be able to monitor the automated system

Automated systems must be predictable

Automated systems must be able to monitor the human

Each element of the system must have knowledge of the others’ intent

Functions should be automated only if there is good reason to do so

Automation should be designed to be simple to train, learn, and operate

These are the ‘headline’ principles, but there are many others in this watershed research carried out by Billings and others, e.g. ‘automation should not be allowed to fail silently.’ Such principles (i.e. all of them, not only the top 9) should be revisited for AI, as already several of them are in danger of not being upheld, e.g.: some AI-based systems may not be predictable; reciprocal knowledge of the others’ intent may prove difficult to achieve in practice; there is a tendence to ‘try AI’ everywhere rather than to ask where it is needed and viable; and it may not prove so easy to train / learn / operate AI-based systems. There is urgent research to be done here.

2.2.10. HFACS (& NASA-HFACS and SHIELD)

The Human Factors Analysis and Classification System (HFACS) approach [

67] was developed for the US Navy, and has proven popular, often leading to ‘variants’ in other domains including space (NASA-HFACS [

68]) and maritime (the SHIELD taxonomy, [

69]. HFACS and equivalent taxonomies of human error and its causes / contributory factors have been in use for decades to determine how and why an error occurred, and how to prevent its recurrence. HFACS-like systems do not address only the surface factors (what happened), but deeper causes, including Human Factors elements, supervisory practices, and organisational and cultural factors. In this respect HFACS embodies a Swiss Cheese approach.

As AI-based systems are introduced to support flight crews and air traffic controllers in their daily operations, taxonomies such as HFACS will likely need updating, adding new terms linked to human-AI interactions. Although some blanket terms already exist, such as complacency and over-trust with respect to automation, these are probably not nuanced enough to capture the full extent of the transactional relationships that will exist between human crews and AI support systems, especially as those systems become more advanced and even executive (i.e. not requiring human oversight).

Additionally, as the AI is seen more as an ‘agent’, consideration must be given to the ways in which it, too, can fail. Already, as noted above, some general failure modes have been considered, such as data biasing, hallucinations, edge and corner cases, etc., but there are likely many more, some of which may be subtle and hard or even impossible to detect. The scenario in which ‘data forensics’ is required to understand why an AI suggested something that contributed to an accident, is probably not too far in the future.

2.2.11. Safety Culture

Safety culture, namely the priority given to safety by the organisation, from the CEO down to the front-line and support workers, originated in the nuclear power industry following the Chernobyl disaster [

70]. It has been applied to aviation most notably since the Uberlingen midair collision in 2002 and mentioned frequently in other aviation accidents. Today, most European air traffic management organisations have undergone safety culture surveys [

71]. Commercial aviation (air traffic control and commercial flight crews) is generally seen as having positive safety culture.

As noted in a companion paper to this one [

71], the introduction of AI into operational aviation systems could aid or degrade safety culture in aviation. In particular, the concern is that human personnel may delegate some of their safety responsibility to the AI, especially if the AI is taking more of an executive role. There is therefore a critical need for a new safety culture approach to monitor what is happening to safety culture as AI is introduced into the cockpit and ATC Ops room or Tower.

2.2.12. Teamwork and the Big Five

According to the ‘Big Five’ theory of Teamwork [

72], the core components of teamwork include team leadership, mutual performance monitoring, back-up behaviour, adaptability, and team orientation, which collectively lead to team effectiveness. These components are predicated on shared mental models, mutual trust and closed-loop communication. What is clear from Salas et al’s original thorough study of teamwork effectiveness is that it doesn’t happen naturally and is something that needs to be continually maintained.

Similar to Crew Resource Management, Teamwork is something that could be significantly disrupted by the imposition of AI ‘agents’. However, AI could also act as a diverse and potentially more comprehensive ‘mental model’ backup system for the pilots, one that is instantly available and adaptable when a sudden unexpected situation occurs. This contrasts with today, where it can take humans a short time to re-adapt, time that can be crucial in an emergency scenario in-flight (one of the principal reasons there are always two pilots in the cockpits of commercial airliners). Probably key for Human-AI Teamwork will be trust and closed-loop communication. The latter will likely entail short, succinct and contextual explainability provided by the AI, whether in procedural or natural language, and/or visually via displays. Team orientation will be an issue for AI-based systems that aim to carry out and execute certain tasks. The very existence of such agents suggests the need for specialised training for leadership of a human-AI team.

2.2.13. Bias and Complacency

Parasuraman [

73] considered the potential end states of automation as implemented in aviation systems. He defined four (non-exclusive) categories: use, misuse (over-reliance), disuse (disengagement) and abuse (poor allocation decisions between human and machine). He found the primary factors influencing these end states to be trust, mental workload, risk, automation reliability and consistency, and knowing the state of the automation. Further work in this area focused on complacency with automation. One of the more worrying biases was the withdrawal of attention from cross-checking the automation and considering contradictory evidence, summarised as ‘looking but not seeing’. More worrying still is that effects such as complacency (not checking) and automation bias (over-trust) are not easy to fix, e.g. via training, and are apparently prevalent in both experienced or naïve (i.e. new) users [

74].

As with several other major study areas of Human Factors, the area of automation bias (especially complacency) needs to be revisited, for several reasons. The first is that cross-checking AI is likely to be more complex, as the way the AI works will itself be more complex and sometimes not open to scrutiny (either non-explainable or unfathomable for humans). Added to this is the fact that GenAI tends to be ‘seductive’ in that the way things are worded sounds plausible and is couched in natural language. The availability and salience of contradictory evidence is highly pertinent to the human capacity of acting as a back-up to the AI, given the well-known biases of humans, including representativeness, availability, anchoring and confirmation biases [

75,

76] (AIs, especially LLMs, are also not immune to biases). The human may want to know why a particular course of action was suggested and others were ignored. Ways to show such ‘alternates’ therefore need to be considered, possibly including the trade-offs the AI has made, or data it has ignored as outliers or not relevant. Similarly, knowing the state of the AI will also be important; not simply whether it is ‘on’ or ‘off’, but its confidence level given the situation at hand compared to the data it was trained on, for example. There is also the question of prior experience: existing pilots can compare their experience to what the AI is suggesting, whereas new pilots (in the future) who have never known a system without AI support, may never have such ‘unfiltered’ experience.

2.2.14. SHELL, STAMP/STPA, HAZOP and FRAM

There are a number of means of analysing the risks associated with human-machine systems. A general thematic framework systems approach model is provided by SHELL [

77], which considers the software (procedures and rules), hardware, environment, and ‘liveware’ (humans and teams), and how they can interact to either yield safe or unsafe outcomes. Approaches such as the Systems Theoretic Accident Model and Processes (STAMP) framework and its derivative Systems Theoretic Process Analysis (STPA), both developed by Leveson [

78], deliver a powerful and formalised analytic approach for identifying human-related hazards and potential mitigations. The Hazard and Operability Study (HAZOP) approach developed in the chemical industry in the 70s by Kletz [

79], though arguably less structured, is still a powerful and agile approach to identifying human-related hazards in complex systems, including those with AI [

80]. The Functional Resonance Analysis Method [

81] has as core premises that most of the time, most things go right, and that there is often a large gap between ‘work as imagined/designed’ and ‘work as done’ in the real operational system (this perspective on risk known colloquially as Safety II [

82]). As people are continually making adjustments in the work situation (because most work systems are not static, they evolve), things can go wrong due to the aggregation of small variances in everyday performance, which can aggregate and propagate in an unexpected manner. FRAM can identify how such variability can effectively ‘resonate’ to yield unsafe outcomes.

No matter how good the design of an AI-based system, neither humans nor AI nor their combination can think of everything; there are likely to be potential hazards that can lead to accidents. As a safety-critical industry, aviation must carry out hazard assessment to identify such potential hazards and develop appropriate mitigations. At the moment, all of the methods above (and others) can be used to identify hazards that can occur in human-AI systems. The problem is that we are missing two inputs. The first is a model of how the AI can fail, or exhibit aberrant behaviour, or suggest inaccurate/biased resolutions or advice. We already know some of the answers, in terms of hallucinations, edge cases, corner cases, biased data usage, etc. e.g. see [

83]. But these are generic. What we need is a way to determine when these and other AI ‘failure modes’ are likely, given the type of ML / LLM being used, its data, and the operational context it is being applied to. It is likely that a taxonomy of AI failure mechanisms will develop as more experience is gained with AI-based systems, but it would be preferable not to have to learn the hard way.

The second unknown, or ‘barely known’, relates to ‘human+AI’ failure modes, i.e. the likely failure types when people are using and interacting with various types of AI tools. We already have ‘complacency’, but again, this is a catch-all term, and knowing when it is likely or not, as a function of the human-AI system design, is unpredictable. This is problematic: how can a safety critical system be certified if complacency is a likely user characteristic and the AI can fail? There is a need for greater understanding of the evolution of human-AI inter-relationships. This may entail longer-term study of human-AI working partnerships, perhaps in extended simulations (lasting months rather than days or weeks), effectively constituting a safe ‘sandbox’ in which to see emergent behaviour of both human and AI.

2.2.15. Just Culture and AI

Since the implementation of ASRS, aviation had generally been seen as having an effective reporting culture, enabling it to be an informed culture, learning from events to continually improve. The reporting culture is predicated on a Just Culture [

84], in which the aviation system prefers to learn from mistakes than blame people for them, as long as there is no reckless behaviour or intention to cause damage or harm. In European aviation, this principle is enshrined in law

2. But there is a potential double-bind in the future for human agents in aviation [

85]. If they are advised by an AI to do something and it results in an accident, they may be asked to justify why they did not recognise the advice was faulty. Similarly, if they choose not to follow AI advice and there is an accident, they will be asked why they did not follow the AI’s advice. Responsibility and justice are human constructs, and an AI, even if its future role is that of an executive agent in an operational aviation system, cannot be prosecuted in a court of law, and prosecuting its developers will likely be fraught with legal complexities. For example, what judge or jury will have sufficient AI literacy to understand what really happened in such an accident, and how will they overcome hindsight and other biases (e.g. ‘the pilot should have known better’) in forming their deliberations?

Just Culture could be a major deal-breaker for unions and professional associations who feel their members (pilots, controllers, others) are at risk of being prosecuted in an area with little legal precedent, and given juridical framework variations according to country, and potentially serious criminal charges. Hypothetical test cases should be carried out in legal sandboxes to anticipate legal argumentation and potential outcomes in this area, and more generally to expand the Just Culture ‘playbook’ [

86]

As an aside, perhaps one useful outcome of the release of ChatGPT and other LLMs into the public domain is that many people see for themselves not only the benefits of these tools, but also how they can mislead or outright ‘lie’ to human end-users. In societal terms, which are important when it comes to justice, some of the initial ‘shine’ of AI has worn a little thin in the public eye.

2.2.16. HF Requirements Systems – CS25/1302, SESAR HP, SAFEMODE, EASA & FAA

Over the decades there have been various Human Factors requirements and assurance approaches. Of particular note in Europe is EASA Certification Standard (CS) 25.1302

3, which is concerned with controls and displays in cockpits, and contains detailed guidance on all aspects of information usage including display design, situation awareness, workload, alarms, etc. Essentially, all controls and displays need to be fit for human purpose whether in normal, degraded mode or emergency situations. Whilst there is no European-wide regulatory equivalent for Air Traffic Management (ATM) systems in Europe, there is comparable guidance available via the SESAR (Single European Sky ATM Research) programme and its Human Performance Assessment Process (HPAP)

4. This comprehensive approach breaks down four high level areas – roles and responsibilities, the human-machine interface, teams and communications, and transition to operations – into detailed and measurable requirements in an argument-based structure. The SESAR HPAP allows a Human Factors ‘case’ to be built for a new system design or change, showing where the design complies with Human Factors principles, and where it does not (or does not need to). More recently, an EU research project called SAFEMODE

5 has developed a Human Factors assurance platform called HF Compass, which refers to the HPAP but also highlights more than twenty tools and techniques that can be used to provide evidence that Human Factors has been assured for a new system. Very recently, EASA

6 has provided preliminary guidance on the Human Factors assurances required for AI-based systems in aviation, in the form of regulatory requirements. The Federal Aviation Agency (FAA) has also just released its own Roadmap

7 for safety assurance of AI-based systems in aviation, though it is currently focused more on safety than Human Factors.

The existing guidance from CS25 1302, the SESAR HPAP, and the EASA guidance on Human Factors aspects of human-AI Teaming systems, all offer excellent foundations for an approach focused on Human-AI systems.

Section 3 accordingly presents a Human Factors Assurance system for Human-AI Teaming systems.

2.3. Contemporary Human Factors & AI Perspectives

Having reviewed the historical landmarks in Human Factors and their implications for Human-AI systems, this sub-section briefly reviews some of the more recent emerging Human Factors literature on Human-AI Teaming, focusing on a model of HAT, the somewhat tricky issues of personification (anthropomorphism) of AI, and emotion-mimicking AI.

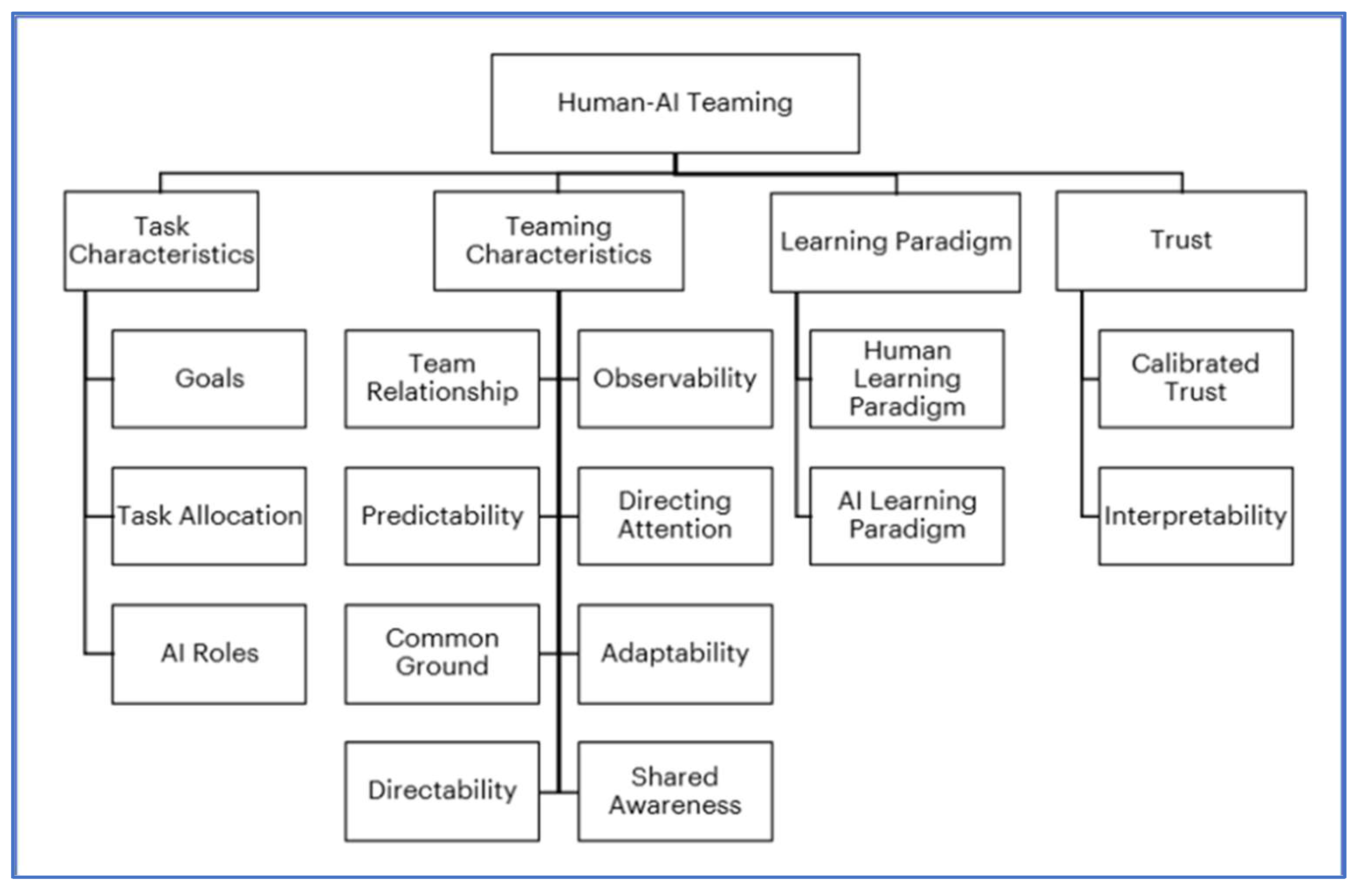

2.3.1. HACO – a Human-AI Teaming Taxonomy

In a recent paper on Human AI Collaboration (HACO), a Human-AI Teaming (HAT) taxonomy has been usefully mapped out [

87] and is shown in

Figure 5 below:

The HACO concept has six core tenets: context awareness, goal awareness, effective communication, pro-activeness, predictability and observability. Taken as a whole, one way to summarise these tenets is that they all ensure that the team members, including the AI, are on the same page with what is happening and what to do about it. In practice this should mean that the workflow remains smooth, without surprises, significant breaks or disruptions, or conflicts. As with human teams, it does not require perfect understanding of one another, but an appreciation of individual behavioural norms (including style of interaction), pace of work, skill sets and capabilities, and limitations.

Context awareness is possibly a more useful (and less anthropomorphic) label than situation awareness. It seeks to establish what the AI was responding to within its inputs and datasets. However, this is not always simply the superficial data in the environment (e.g. weather patterns that might affect flight route), but the way the AI will use statistical and other algorithms to interpret such data according to the task and goals at hand. The design challenge is to maintain the usability adage of ‘what you see is what you get’, whether this is achieved via natural language dialogue or (more likely) visual media that can decrypt the AI’s computational processes in meaningful and quickly ‘graspable’ ways for the end user.

Goal awareness (a precursor to goal alignment) is a higher-level attribute, related to context awareness, and ensures that human and AI are on the same page at all times. This becomes important in work arrangement scenarios where the AI is able to modify the goal hierarchy, and where goals may dynamically shift during a scenario (e.g. for an emergency, as it worsens or becomes more stable). It can also be important where there are a mixture of safety and other goals, some of which may conflict with safety. As for contextual awareness, a design challenge is how to ensure the human is aware of the goals the Ai is working towards as they change and evolve.

Effective Communication can occur via various modalities, from natural language and even gestures, to digital displays and procedural textual responses to human prompts. The keyword here is “effective.’’ Communication for AI tools or systems below EASA’s category 2B may not need to be that advanced, though for 1B and 2A there may need to be an element of explainability if the AI’s task or output is sufficiently complex. For human AI collaboration at the 2B level, there will likely not only need to be communication, but a degree of rapport, so that the AI is communicating in terms and contexts familiar to the human. This implies a shared understanding of the local operational environment conditions and practices. For example, this can refer not only to a specific aircraft type such as an A320 or B737, but how those aircraft types are fine-tuned by the airlines using them, along with their Standard Operating Procedures and day-to-day practices.

Proactiveness links again to EASA’s 2B and above categorisations, whereby the AI can initiate its own tasks and even shift or re-prioritise goals, giving the AI a degree of autonomy and even agency (since it can act under its own initiative). However, in contrast to the distinctive categorisations of EASA these authors [

87] suggest the concept of

‘sliding autonomy’, wherein the human (or the system) determines the level of autonomy. This is of interest in aviation in cases where flight crew or air traffic controllers, for example, may be overwhelmed by a temporary surge in tasks or traffic respectively, and may wish to ‘hand-off’ certain tasks (especially low-level ones) to an AI. This is effectively an update of the Adaptive Automation concept.

Predictability can refer both to the degree to which the pace of work of an AI is understood, trackable and manageable, to the degree to which an AI might ‘surprise’ the humans in the team via its outputs. The former probably requires some kind of overview display to know what the AI is doing and the progress on its tasks or goals. The latter will depend on the amount of human-AI training afforded prior to teamworking in real operational settings.

Observability refers to the transparency of the progress of the AI agent when resolving a problem, and can be linked to explainability, though in practice the AI’s workings might be routinely monitored via some kind of dashboard or other visualisation rather than a stream of textual explanations, albeit with the user able to pose questions as needed.

Three additional HAT attributes are mentioned in [

87] and are worth reiterating here:

Directing attention to critical features, suggestions and warnings during an emergency or complex work situation. This could be of particular benefit in flight upset conditions in aircraft suffering major disturbances.

Calibrated Trust wherein the humans learn when to trust and when to ignore the suggestions or override the decisions of the AI.

Adaptability to the tempo and state of the team functioning.

With respect to Adaptability, one of the hallmarks of an effective team, it may be useful to resurrect High Reliability Organisation (HRO) theory [

88]. All five of the pillars of HROs –

preoccupation with failure,

commitment to resilience,

reluctance to simplify explanations,

deference to expertise and

sensitivity to operations – could well apply to Human-AI Teams. HRO theory as a whole leans towards collective mindfulness of the team, and here is where it is necessary to consider how humans think ‘in the moment’ compared to how an AI might build up its own situation representation or context assessment.

2.3.2. AI Anthropomorphism and Emotional AI

Human-AI Teaming can be considered to be an anthropomorphic term [

33], suggesting that the AI is a team player, denoting human qualities to a machine. With GenAI systems the ‘illusion of persona’ can be stronger, since one has the impression of conversing with a person rather than a program, to the extent that we often add polite ‘niceties’ such as please and thank you in interactions with ChatGPT and equivalent LLMs, forgetting that they are simply very powerful algorithms calculating the next most likely word in a sequence.

Anthropomorphism relates to the identity we assign an AI system, and hence the degree of agency we accord it. The more we ‘personify’ AIs, the more the danger of delegating responsibility to it, or of surrendering authority to its logic and databases, or of basically second-guessing ourselves rather than the AI. In this vein it is worth recalling that AI systems are created by people (data scientists), and there are many human choices that go into development of AI systems, e.g. choice of training, validation and test datasets, choice of hyperparameters, selection of most appropriate algorithm, etc. [

4].

The recent FAA Roadmap on AI is explicitly against the personification of AI, and given that AI has no sentience and will likely not do so for some time, it is right to do so, especially in safety critical operations. A key practical consideration, however, is whether treating future AI systems as a team member could enhance overall team performance. This is as yet unknown, but it leads to a second question of whether we can tell the difference between a human and an AI. In a recent study of ‘emotional attachment’ to AI as team members [

89], most participants could tell the difference between an AI and a human based on their interactions with both. Another study [

90] examined human trust in AIs as a function of the perception of the AI’s identity. The study found that AI ‘teammate’

performance matters, whereas AI

identity does not. The study authors cautioned against using deceit to pretend an AI is a human. Deception about AI teammate’s identity (pretending it is a human) did not improve overall performance, and led to less acceptance of AI solutions. Knowing it is an AI improved overall performance.

In a non-safety-critical domain study [

91], two key acceptance parameters for emotional AI were found to be the potential to erode existing social cohesion in the team, and authority (impacts on the status quo). As with other studies in this area, the authors found people judged machines by

outcomes. A further study [

92] found that monitoring people’s behavior and emotional activity (speech, gestures, facial expressions, and physiological reactions), even if supposedly for health and wellbeing, can be seen as intrusive. Such monitoring activities can be for stress, fatigue and boredom monitoring, and error avoidance, and of course productivity. People may be uncomfortable with this level of personal intrusion of their behavior, bodies and personal data.

Overall, therefore, preliminary indications are that aviation needs neither anthropomorphic (personified) nor emotional AI. What matters is the effectiveness of the AI in the execution of its tasks.

3. Human Factors Requirements for Human-AI Systems

Having reviewed AI and Human Factors relevant to AI-based systems in aviation, this section outlines the development of a new and comprehensive set of Human Factors requirements for future HAT systems. First, any Human Factors Requirements System for Human-AI systems must satisfy several requirements of its own:

It must capture the key Human Factors areas of concern with Human-AI systems.

It must specify these requirements in ways that are answerable and justifiable via evidence.

It must accommodate the various forms of AI that humans may need to interact with in safety critical systems (note – this currently excludes LLMs) both now and in the medium future, including ML and more advanced Intelligent Assistants (EASA’s Categories 1A through to 3A).

It must be capable of working at different stages of design maturity of the Human-AI system, from early concept through to deployment into operations.

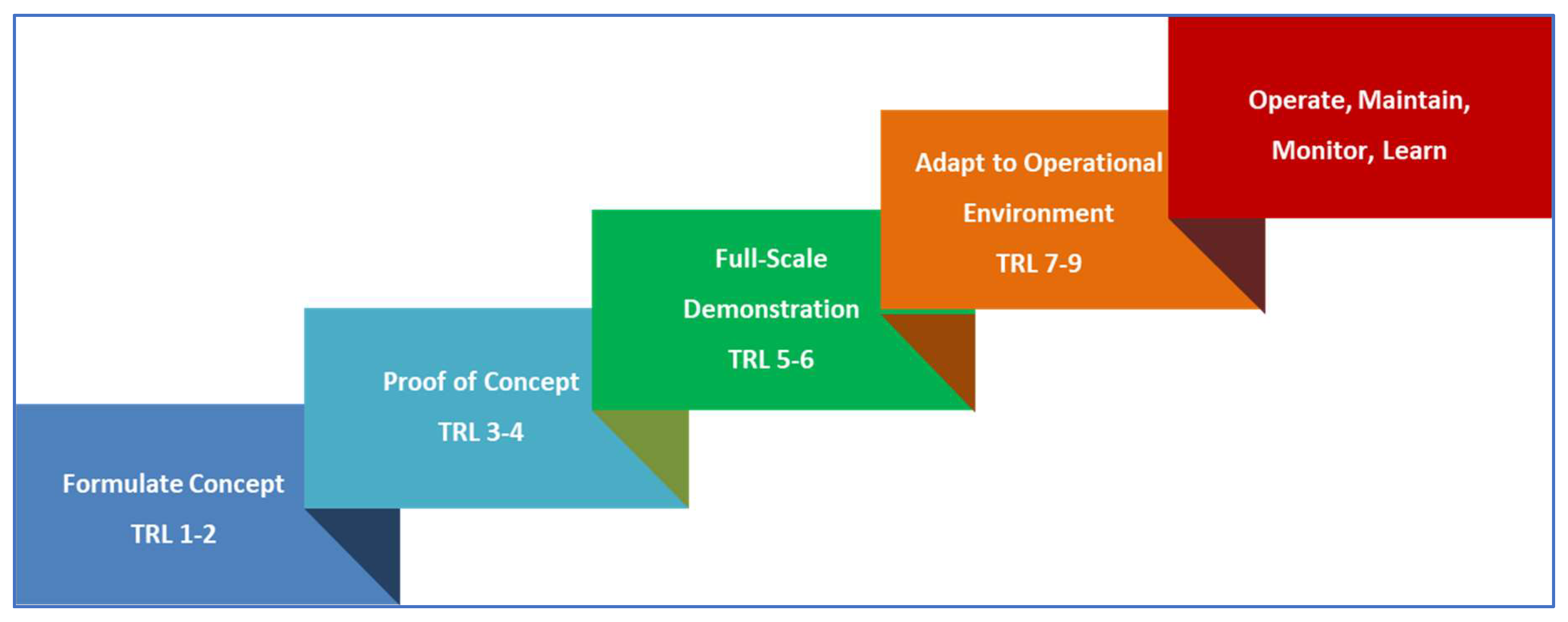

With respect to this last requirement, the NASA system of Technology Readiness Levels

8 (TRLs) is a useful maturity model for aviation system design maturity, as illustrated in

Figure 6

In the early stages of a project, a number of the requirements questions will have to be returned to at a later stage in the development life cycle. But it is better to highlight them early rather than wait until the design is too advanced to be changed. Once the system is near deployment, all questions can usually be answered, and the organisation will have a robust basis upon which to deploy and operate the Human-AI system.

Following on from the principles of Human Centred Design, Human Factors needs to be integrated from the early design stages. Otherwise, the design of the AI will be a poor ‘fit’ to the human end user, and the only significant degree of freedom left to optimise HAT performance will be training. Training end users to operate a poorly designed system is a bad design strategy. Therefore, Human Factors requirements should ideally be applied from the early concept stages onwards, until the system is operational. The critical design stages however, in terms of integration of Human Factors to deliver optimal system performance, are TRLs 3-6, as these stages determine how the human-machine (AI) interactions will take place.

Typically, TRLs 1-2 are concerned with early concept exploration. For Human-AI System design, at this TRL usually the most important considerations focus on Roles and Responsibilities, namely who (or what) will be in charge when the AI is operating. Decisions about sense-making such as how shared situation awareness will be established, and primary human-AI interaction modes, e.g. ‘conventional’ (keyboard, mouse, touchscreen, etc.) or more advanced (speech, gesture recognition) can be made, as well as whether the AI will be used by a single person or a team. It is at this stage that key design choices are made concerning the adoption of a Human Centred Design approach, including the use of end users in informing the early ‘foundational’ concept.

TRLs 3-4 add a lot more detail, fleshing out the concept’s architecture, and gaining a picture of what the AI might look and feel like to interact with, via early prototypes and walk-throughs of human-AI interaction scenarios. The area of sense-making is crucial here, and communication and teamworking aspects will become clearer.

At TRLs 5-6 models and prototypes will be developed iteratively until a full-scope demonstration is completed and tested in a realistic simulation with operational end users. This period of design and development will see many issues ‘nailed down’ and solidified into the design and operational concept (CONOPS), having been validated via robust testing with human end users. Risk studies will focus on errors and failures seen, as well as those that could conceivably occur once the system is in operation.

TRLs 7-9 prepare the concept for deployment in real world settings. This is the time to consider in earnest the ramifications of entering a human-AI system into an operational organisation, with requirements for competencies and training of end users, as well as the often ‘thornier’ socio-technical systems issues such as staffing, user acceptance, ethics and wellbeing. These latter issues often determine whether the system will be accepted and used to its full extent.

After TRL 9 the system is in operational use. However, since most AI systems are learning systems, monitoring – particularly in the first six to twelve months – will be a critical determinant of sustainable system performance.

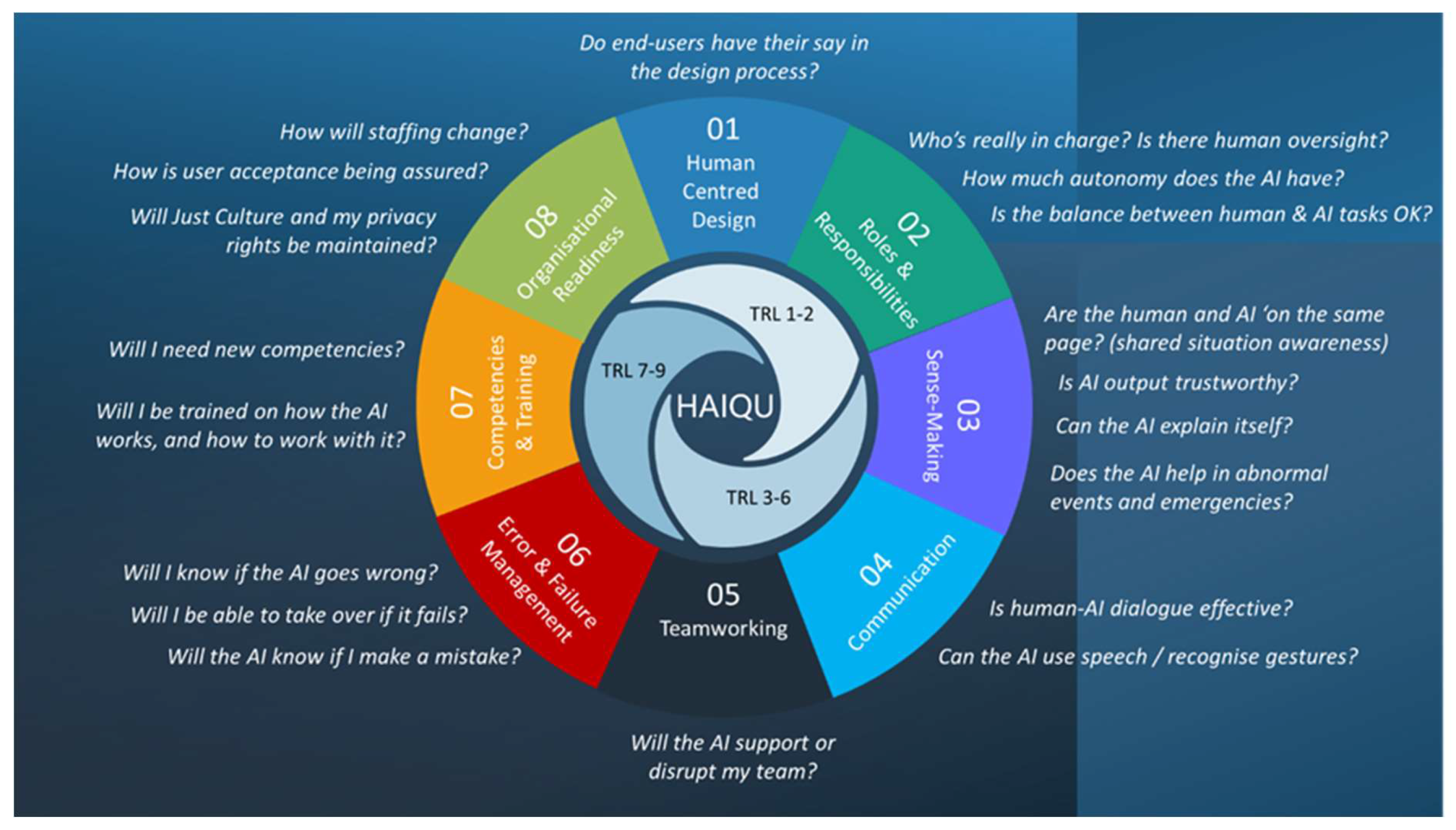

The relevance of the Human Factors areas to the different TRL are highlighted in

Figure 7, to help the user adapt their evaluation approach. As illustrated in the figure, the application of Human Factors areas to TRLs are not always clear cut, so some degree of judgement must be used. For many projects, in early TRLs entire areas can be deemed ‘TBD’ (to be decided later) or even N/A (not applicable – for now) and returned to in later design stages. For example, many research projects will not consider Human Factors areas 7 & 8, although it is worth considering impacts on

staffing early, since this can be a ‘deal-breaker’ for any project.

3.1. The Human Factors Requirements Set Architecture

Based on the literature review, including the SESAR HPAP and the recent EASA Guidance on Human Factors for AI-based systems [

32], as well as the EU Act on AI, eight overall areas were identified, as shown in

Figure 7 and outlined below.

Human Centred Design – this is an over-arching Human Factors area, aimed at ensuring the HAT is developed with the human end-user in mind, seeking their involvement in every design stage.

Roles and responsibilities – this area is crucial if the intent is to have a powerful and productive human-AI partnership, and helps ensure the human retains both agency and ‘final authority’ of the HAT system’s output. It is also a reminder that only humans can have responsibility – an AI, no matter how sophisticated, is computer code. It also aims to ensure the end user still has a viable and rewarding role.

Sense-Making – this is where shared situation awareness, operational explainability, and human-AI interaction sit, and as such has the largest number of requirements. Arguably this area could be entitled (shared) situation awareness, but sense-making includes not only what is happening and going to happen, but why it is happening, and why the AI makes certain assessments and predictions.

Communication – this area will no doubt evolve as HATs incorporate natural language processing (NLP), whether using pilot/ATCO ‘procedural’ phraseology or true natural language.

Teamworking – this is possibly the area in most urgent need of research for HAT, in terms of how such teamworking should function in the future. For now, the requirements are largely based on existing knowledge and practices.

Errors and Failure Management – the requirements here focus on identification of AI ‘aberrant behaviour’ and the subsequent ability to detect, correct, or ‘step in’ to recover the system safely.

Competencies and Training – these requirements are typically applied once the design is fully formalised, tested and stable (TRL 7 onwards). The requirements for preparing end users to work with and mange AI-based systems will not be ‘business as usual, and new training approaches and practices will almost certainly be required.

Organisational Readiness – the final phase of integration into an operational system is critical if the system is to be accepted and used by its intended user population. In design integration, t is easy to fall at this last fence. Impacts on staffing levels (including levels of pay), concerns of staff and unions, as well as ethical and wellbeing issues are key considerations at this stage to ensure a smooth HAT-system integration.

This eight-area architecture goes beyond the SESAR HPAP four area structure (Roles & Responsibilities, Interface Design, Teamworking and Transition) and has added new sub-areas including trustworthiness, AI autonomy, operational explainability, speech recognition and human-AI dialogue, Just Culture, etc. Many of the requirements from both EASA’s CS 25 1302 are evident at the specific requirements level, but have been re-oriented or augmented to focus on AI and HAT. The original requirements set was written before the most recent EASA HAT guidance release, and since that time alignment efforts have been made. The resultant HF Requirements set is significantly larger than the EASA one, as it deals with a number of areas and sub-areas outside EASA’s current focus (e.g., related to roles and responsibilities organisational readiness, competencies, human agency, etc.).

The detailed structure is as follows, showing all sub-categories and the number of requirements in each of the total of seventeen categories and sub-categories (165 requirements in total, of which 51 are common requirements with EASA’s):

Extracts from the requirements question set are shown in

Table 1. Those in red are common with EASA requirements (though they may have been reworded), and those in red towards the end (Organisational Readiness) are also embodied in the EU Act on AI. Whereas design requirements are typically stated as imperative statements (e.g. ‘the colour coding should…’), the Human Factors requirements in

Table 1 are phrased as questions. This is for three reasons. First, this requirements set’s primary aim is to support designers and product teams, rather than serving as a regulatory certification tool. Second, since HAT design is a new and rapidly evolving area, there are still uncertainties about how exactly to best do something. It therefore seems more appropriate to raise the issue with the design or product development team as a question, letting them decide how best to satisfy it. Third, questions are more engaging than flat statements and may engender more ‘purposeful creativity’, which is welcome in a pioneering field of design application such as Human-AI Teaming.

4. Application of Human Factors Requirements to a HAT Prototype

The aim of the questionnaire is to help developers realise and deliver a highly usable and safe Human-AI system, one that end users can use effectively and will want to use (avoiding misuse, disuse and abuse as mentioned earlier). The approach has been tested on several Human-AI Teaming use cases from the HAIKU research project (

https://haikuproject.eu), outlined in

Figure 8. Three of these are at TRL levels 3-6, and one (Urban Air Mobility) is at TRL 1-2.

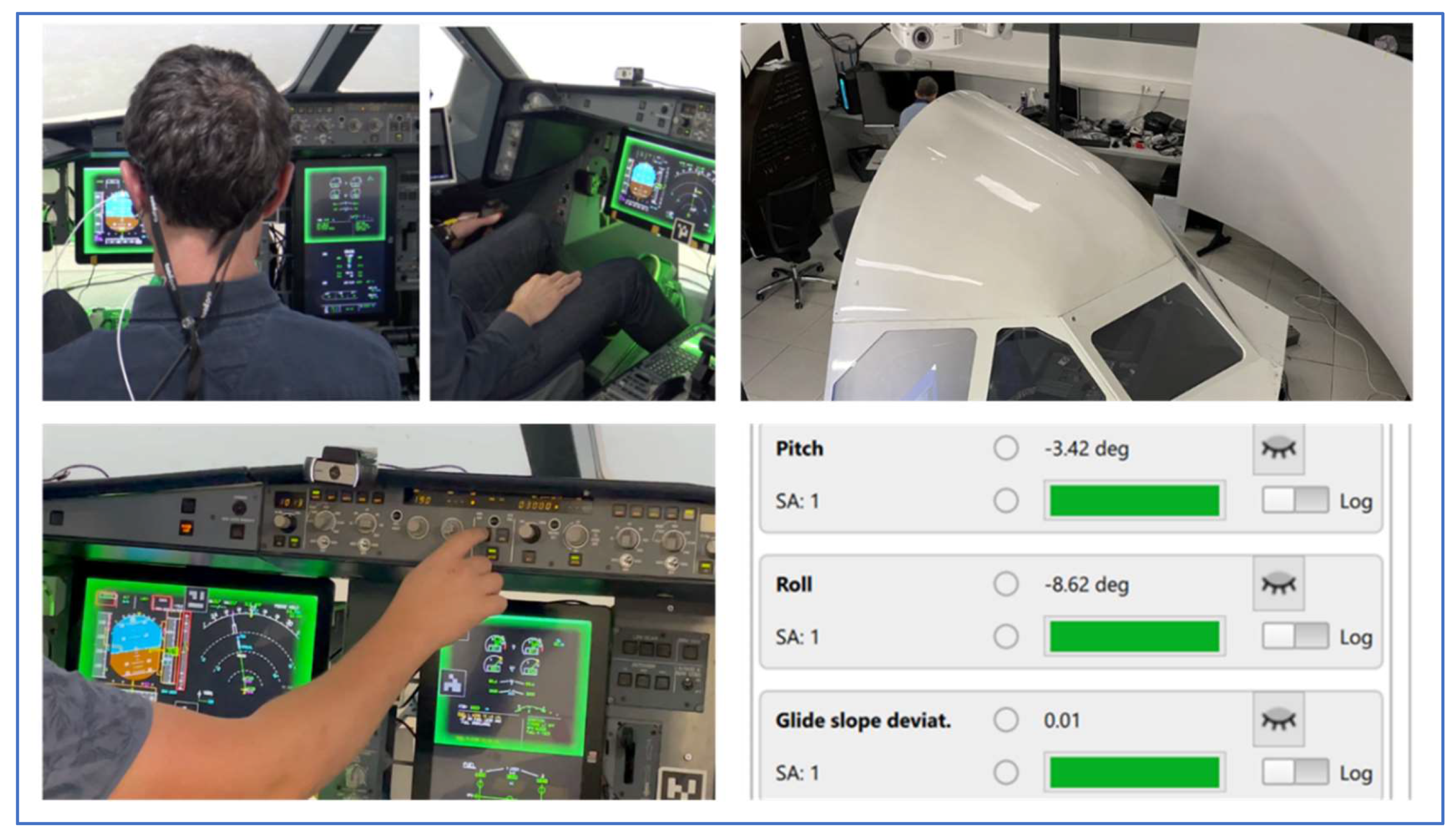

The first use case, UC1, addresses support to a single pilot in the event of startle response, wherein a sudden unexpected serious event (e.g. a lightning strike) can cause ‘startle’, leading to diminished cognitive performance for a short period of time (e.g. 20 seconds) [

93,

94,

95]. The FOCUS (Flight Operational Companion for Unexpected Situations) AI supports the pilot first by detecting startle via various physiological sensors analysed by a trained AI, using an AI technique known as Extreme Gradient Boosting. Second, it analyses where the pilot is looking compared to where the pilot should be looking given the situation, and if different, the AI highlights the relevant parameter on the cockpit displays (see

Figure 9). This is effectively directed (or supported) situation awareness.

This use case is currently TRL5, and experiments have been run in the simulator with commercial pilots. The HF requirements set was applied to the use case in December 2023, via a one-day session with the design and Human Factors team at ENAC (École Nationale Aviation Civile, Toulouse:

https://www.enac.fr/), shortly after a series of experimental trials with pilots. An extract from the evaluation is shown in

Table 2 for a sample of the questions from the first four Human Factors Areas.

At several points during the HF Requirements review with the design team, potential improvements were derived for the AI system, in terms of how it is visualised and used by the pilot. In total, 27 issues were raised for further consideration by the design team, in terms of potential changes to the design or further tests to be carried out in the second set of simulations (Val2). A number of requirements were deemed ‘not applicable’ to the concept being evaluated, and many of the requirements from the last two areas (Competencies & Training; Organisational Readiness) were not answerable at this design stage.

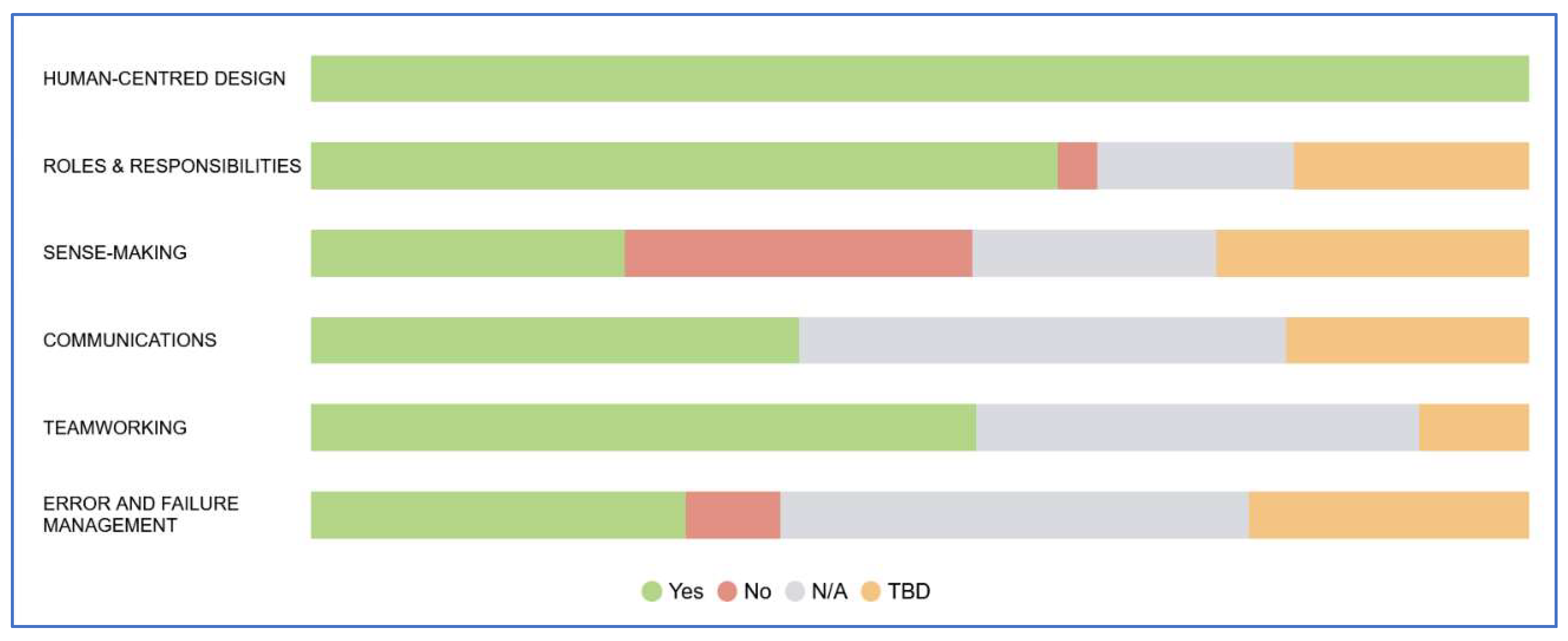

Figure 10 gives an overview of the results at the end of Val1 (first set of simulation runs with pilots) in terms of HF compliance (‘Yes’ responses in green, red = not compliant, grey = N/A and orange = TBD).

The Human Factors requirements evaluation process for UC1 has resulted in a number of refinements to the HAT design, including: AI display aspects related to the ‘on/off’ status of the AI support; use of aural SA directional guidance; application of workload measures; consideration of how to better maintain a strategic overview during the emergency; consideration of value of prioritisation by AI during the emergency; pilot trust issues with the AI; consideration of the utility of personalisation of the AI to individual pilots; consideration of potential interference of the AI support with other alerts during an emergency; and use of HAZOP for identification of potential failure modes and recovery/mitigation measures. More generally it raised a number of issues that could be tested in Val2.