Submitted:

13 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

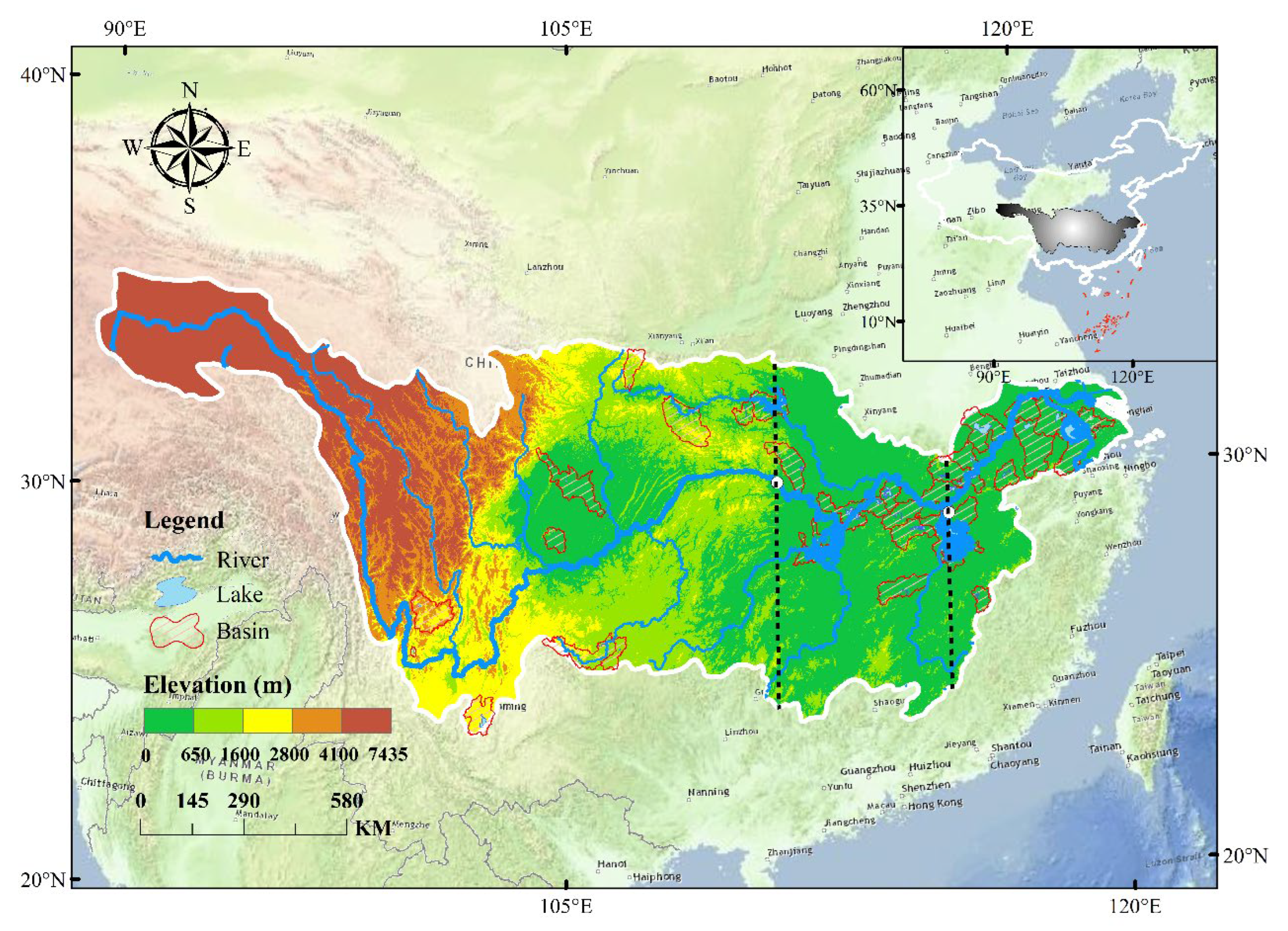

2.1. Study Sites

2.2. Data Collection and Processing

2.3. Model Description

2.3.1. Habitat Quality Index

2.3.2. TLI Index

2.3.3. Method for Quantitatively Assessing Contributions of Driving Factors

2.3.4. Data Analysis and Processing

3. Results

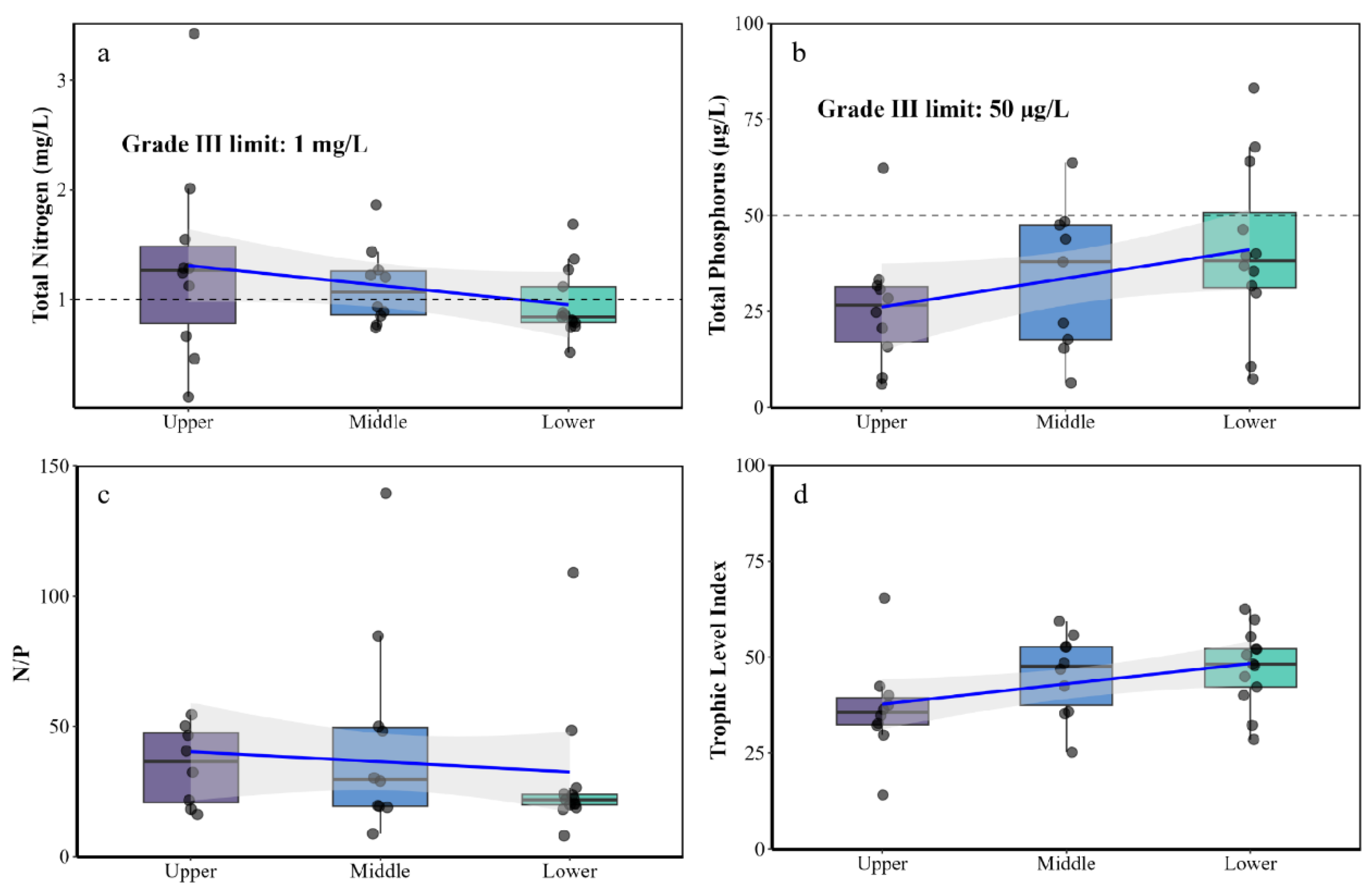

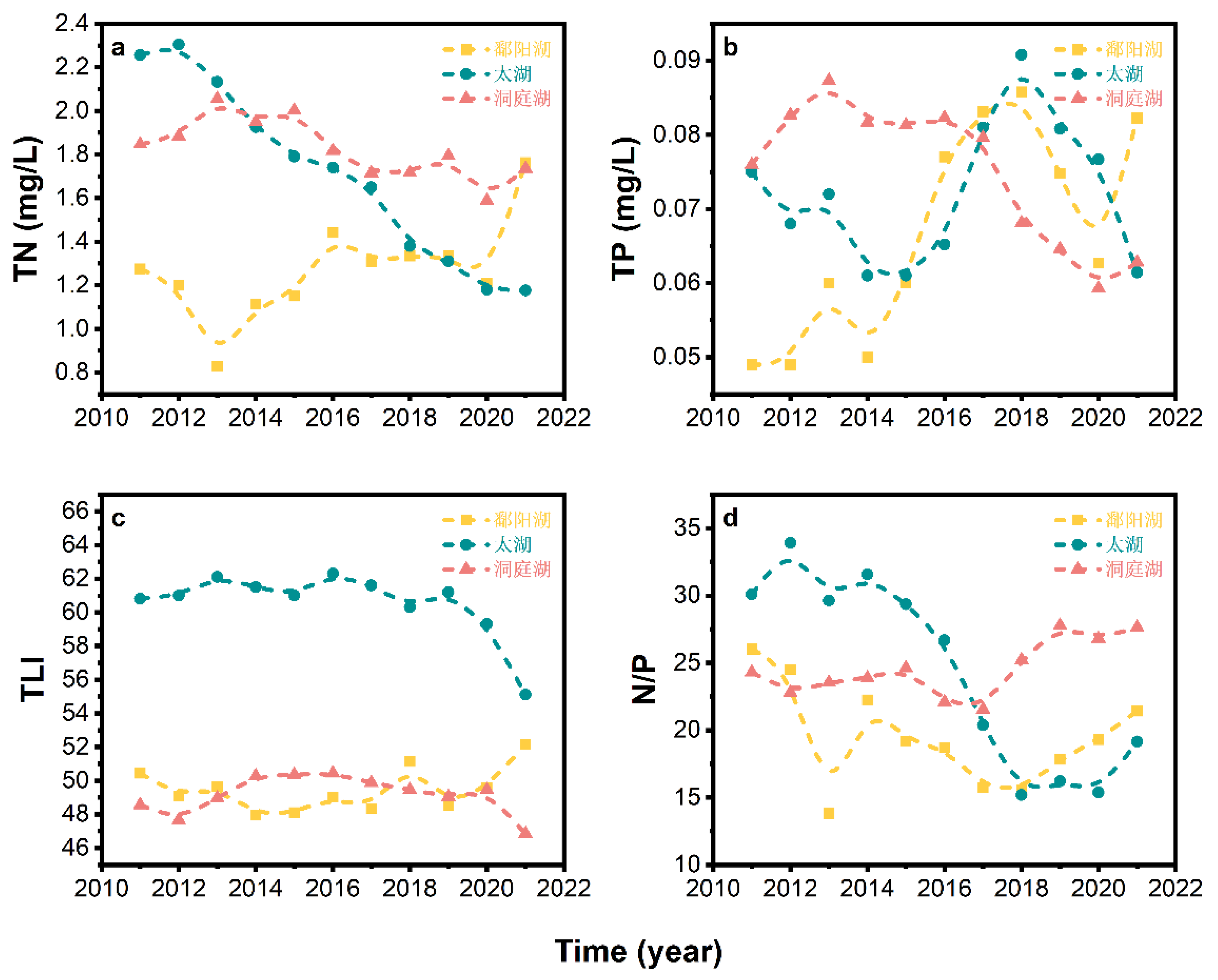

3.1. Spatio-temporal Variations in Nutrient Status of Typical Lakes and Reservoirs

3.1.1. Spatial Analysis of Nutrient Status in Typical Lakes and Reservoirs

3.1.2. Temporal Analysis of Nutrient Status in Representative Lakes and Reservoirs

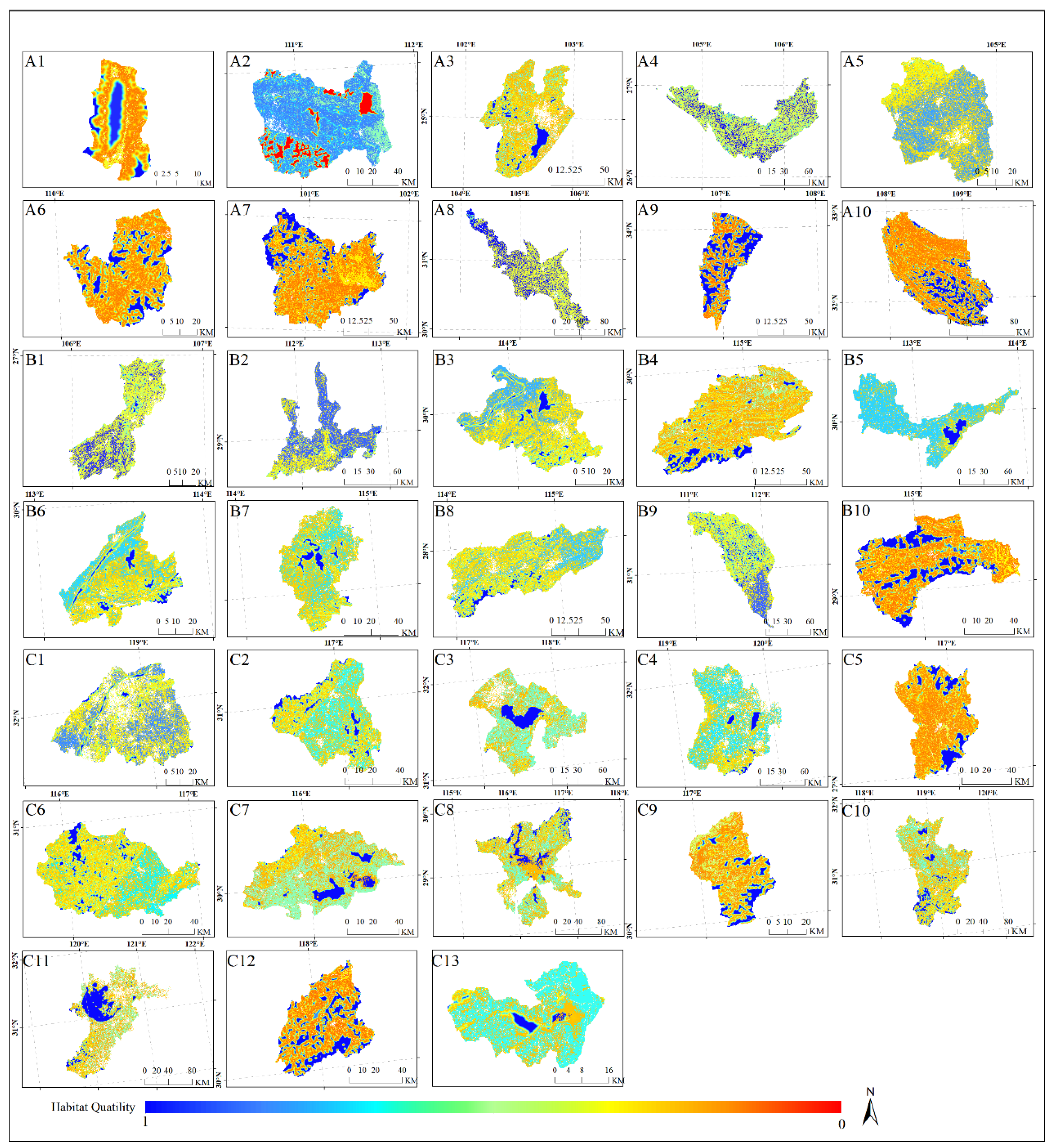

3.2. Analysis of Habitat Condition Disparities among Typical Lakes and Reservoirs

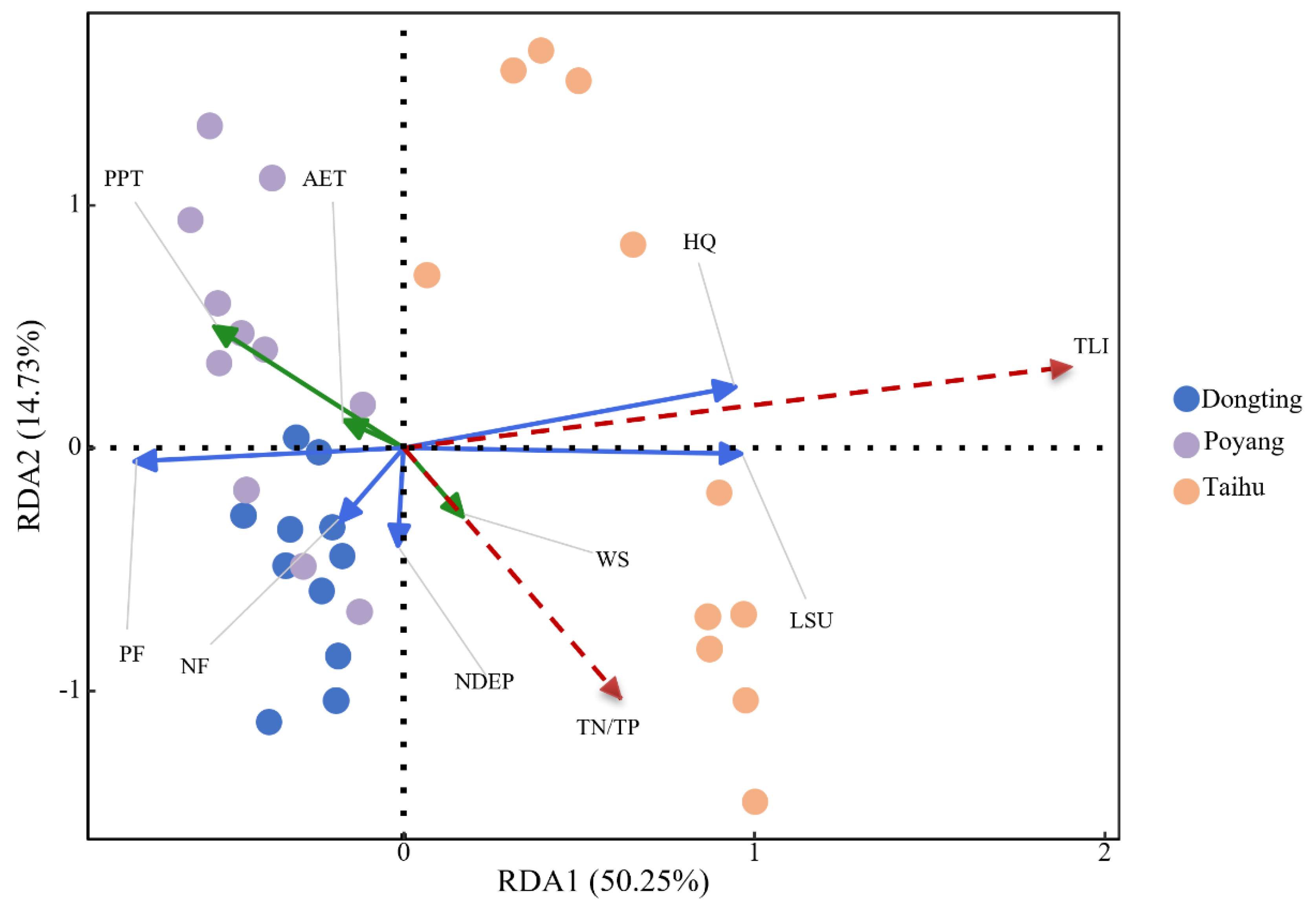

3.3. Quantitative Assessment of Contributions from Natural and Anthropogenic Factors

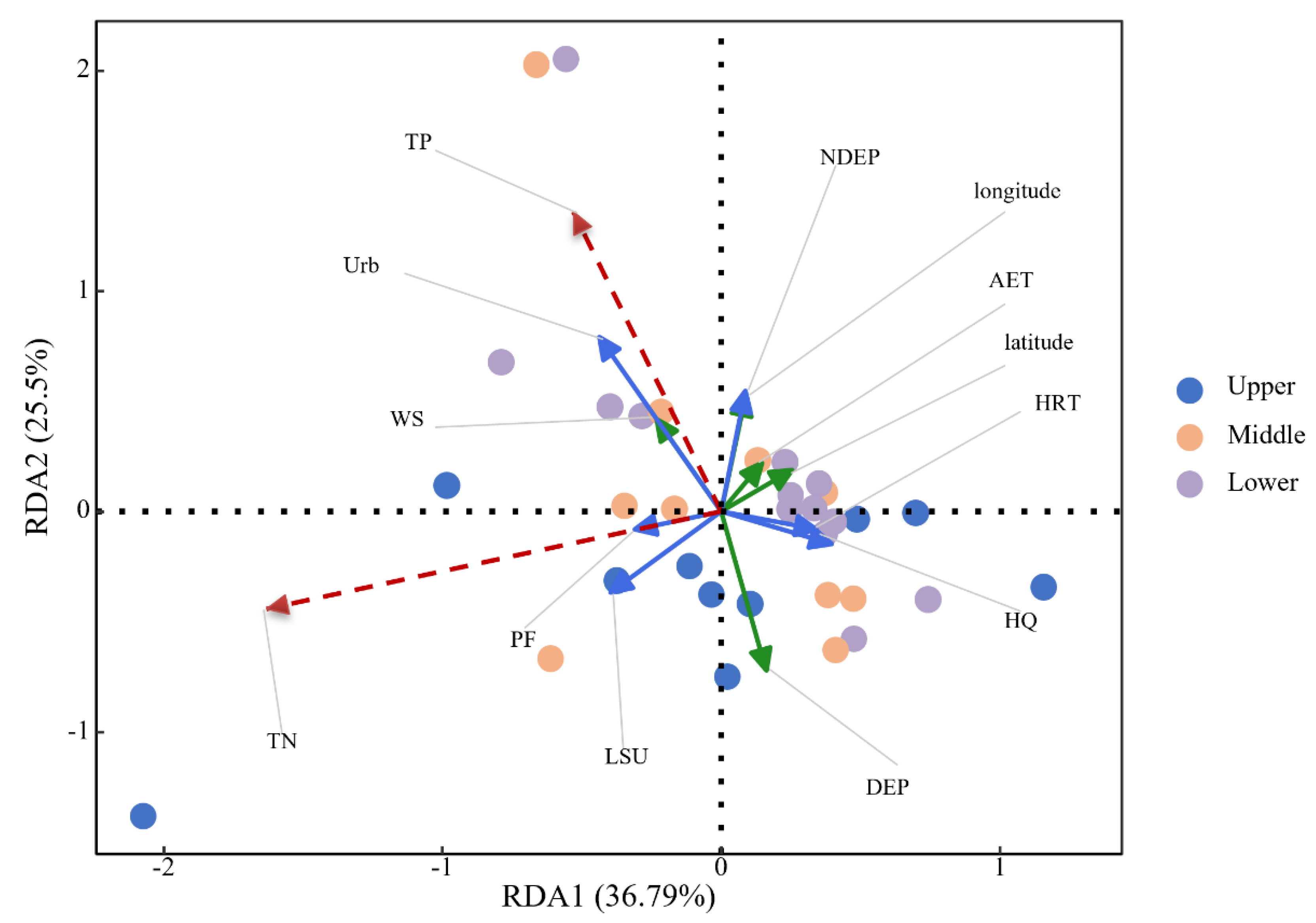

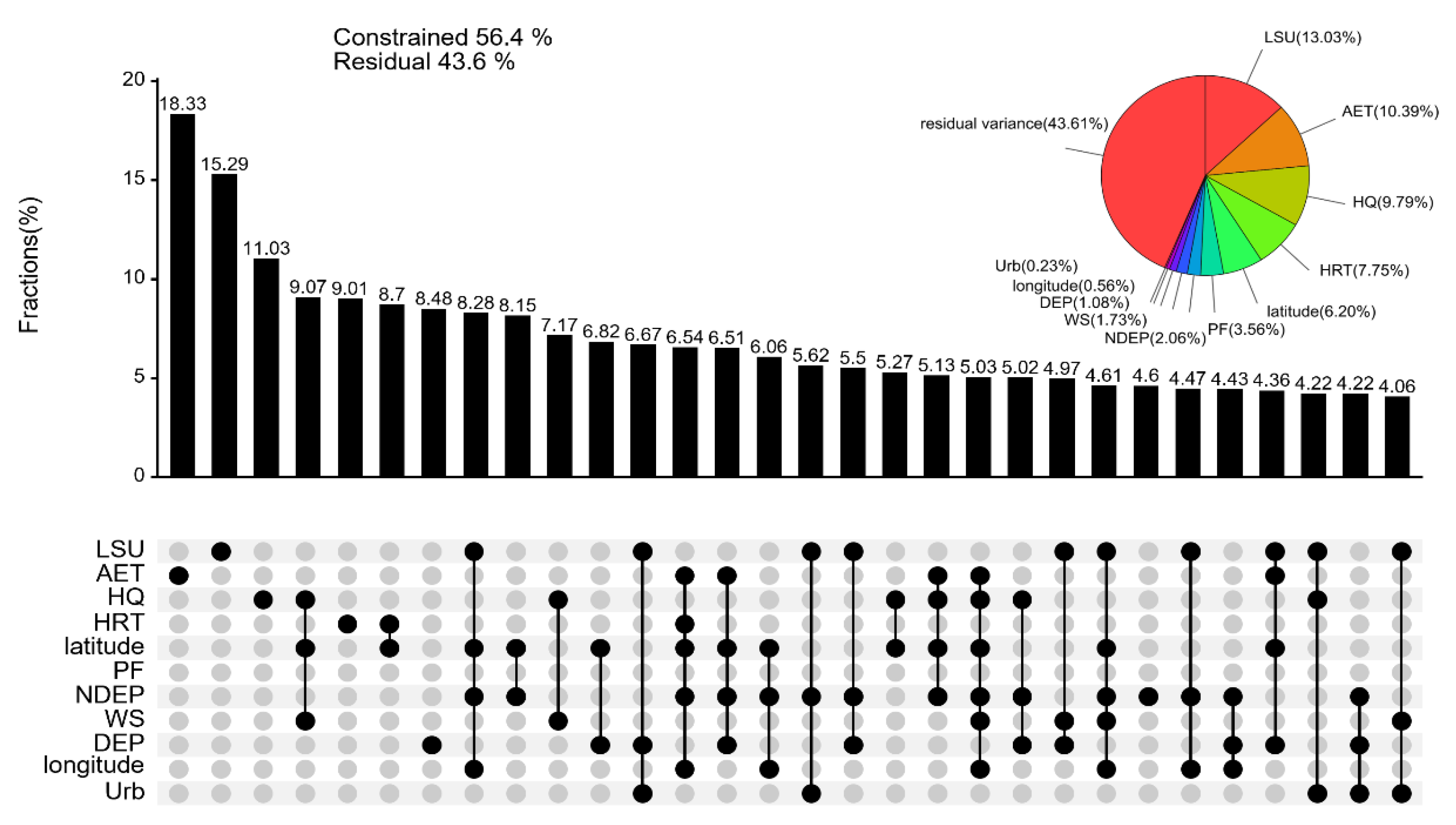

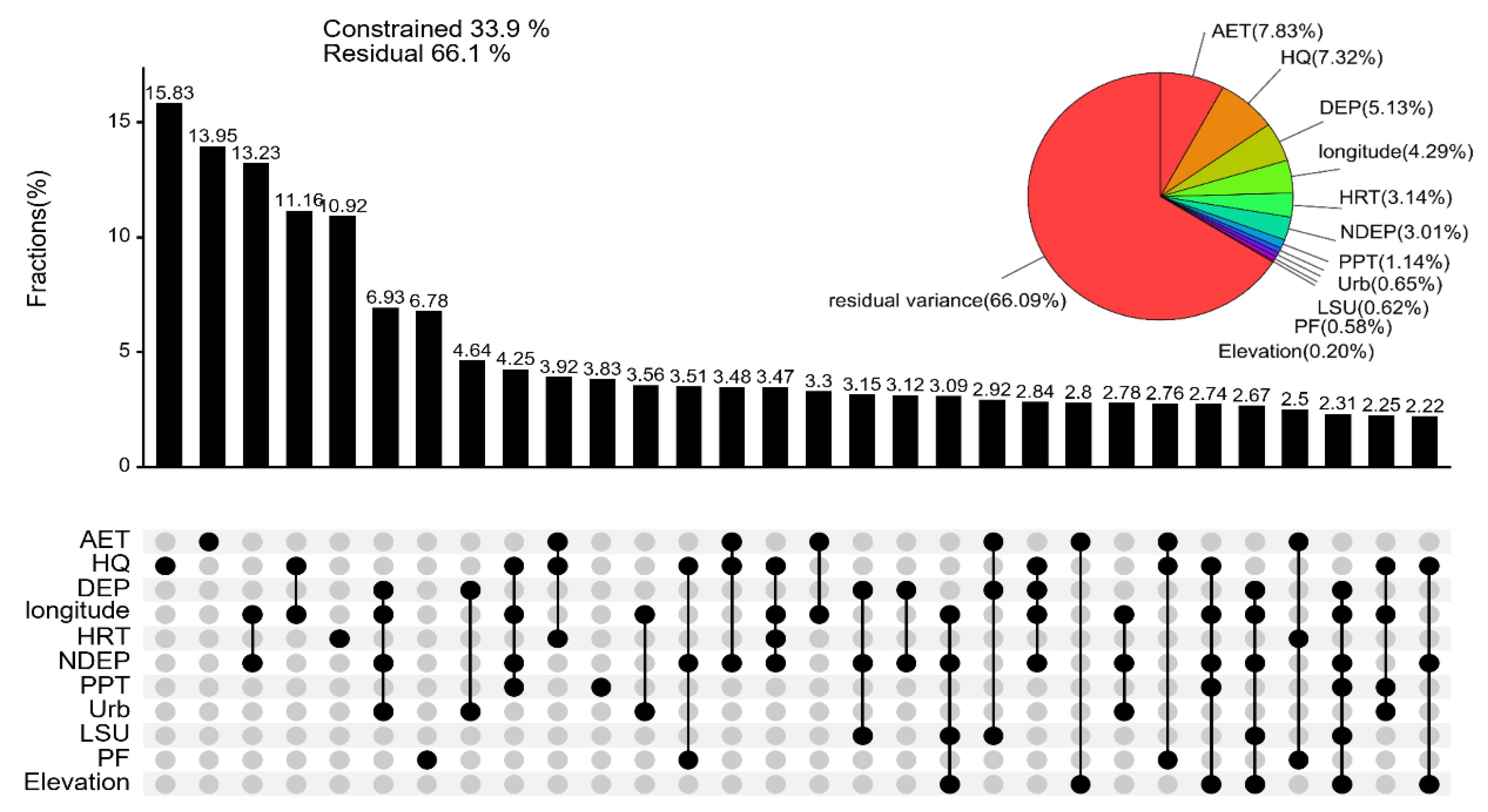

3.3.1. Unveiling the Drivers of Variability in TN and TP Concentrations

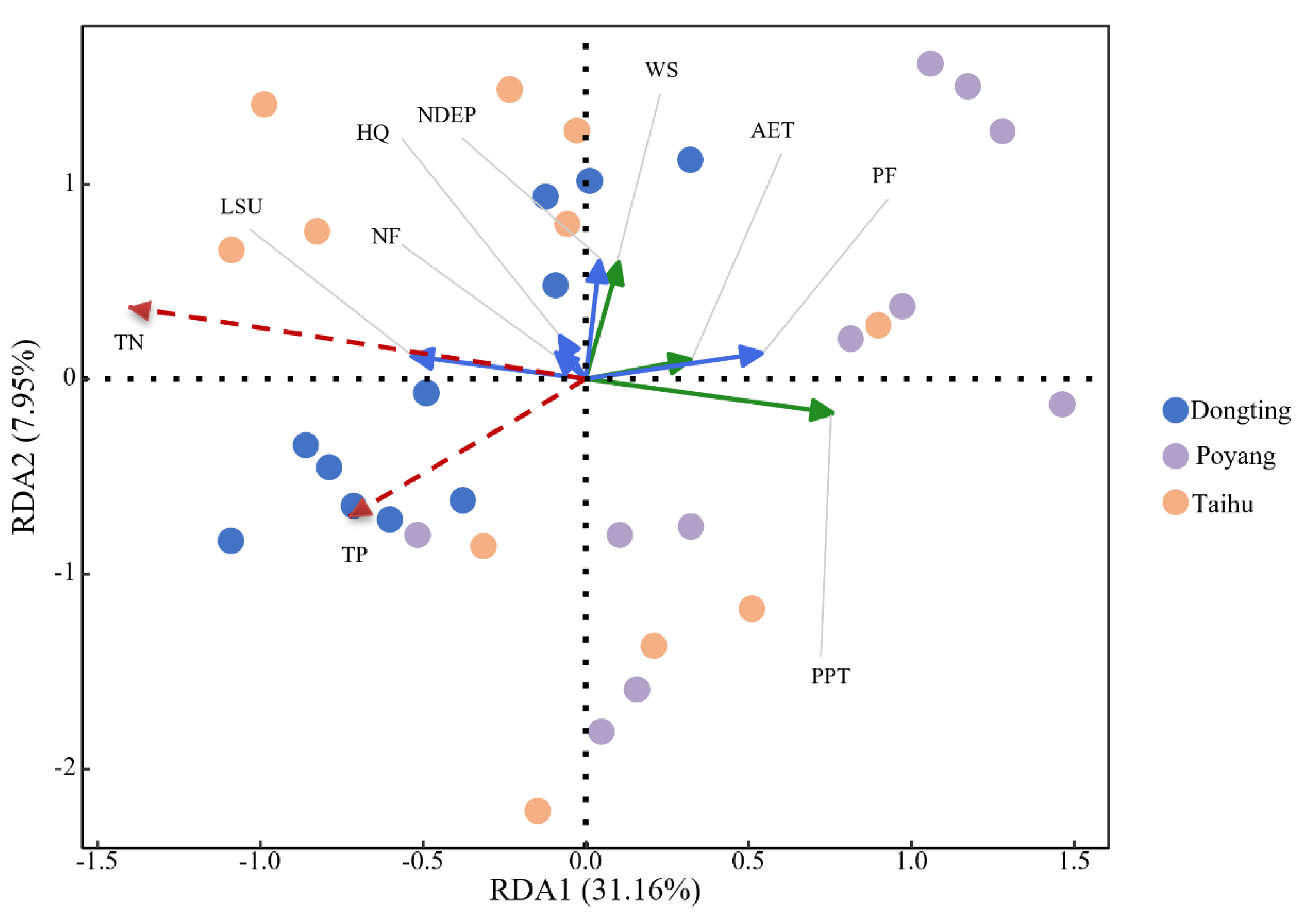

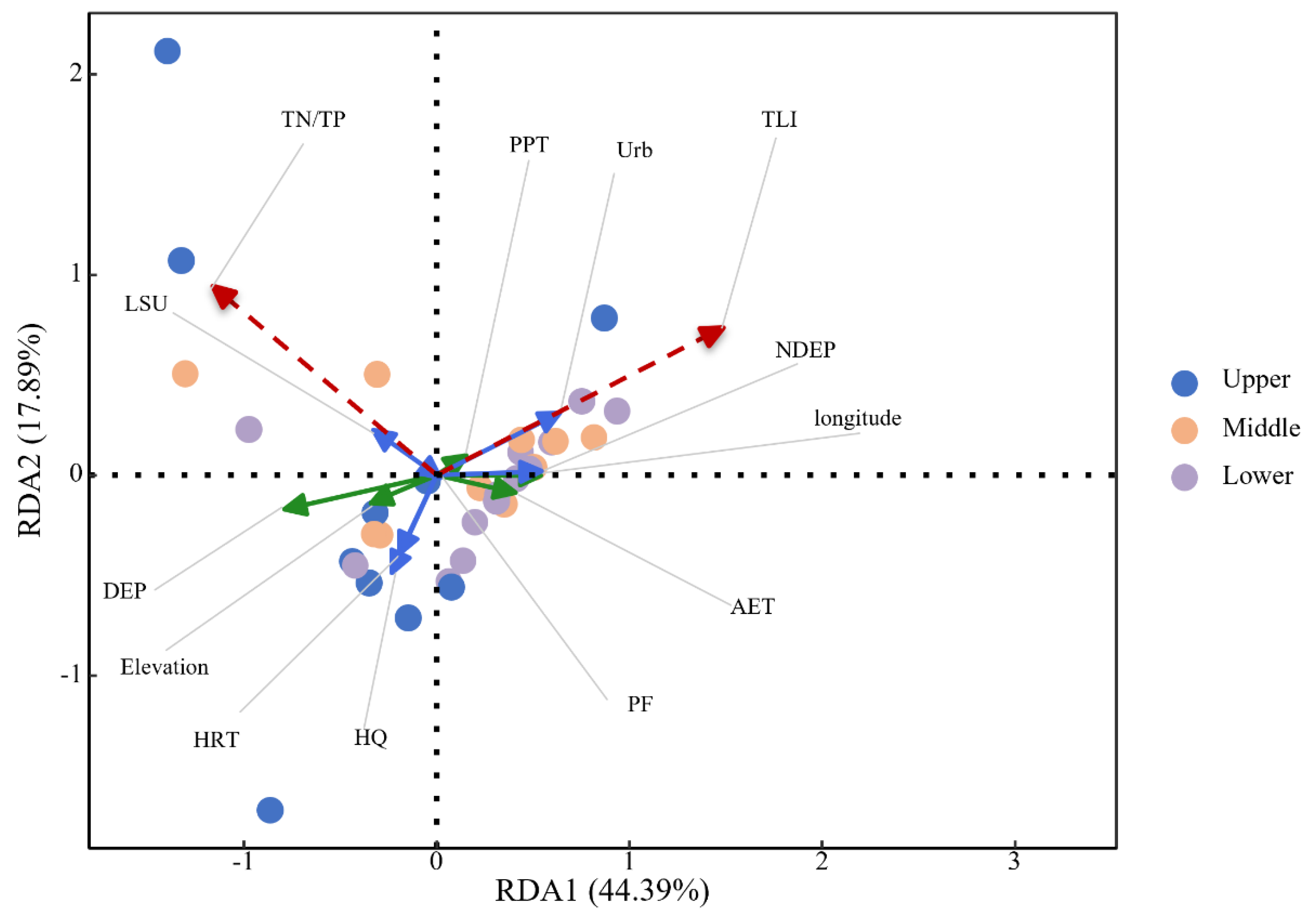

3.3.2. Unveiling the Driving Forces of Variability in TN/TP and TLI

3.5. Strategic Directions for Nitrogen and Phosphorus Control in Key Lakes and Reservoirs in the Yangtze River Basin

4. Conclusions

References

- Cui, M.; Guo, Q.; Wei, R.; Chen, T. Temporal-Spatial Dynamics of Anthropogenic Nitrogen Inputs and Hotspots in a Large River Basin. Chemosphere 2021, 269, 129411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Eglinton, T.I.; Zhang, J.; Montlucon, D.B. Spatiotemporal Variation of the Quality, Origin, and Age of Particulate Organic Matter Transported by the Yangtze River (Changjiang). JGR Biogeosciences 2018, 123, 2908–2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People's Republic of China. National Suface Surface Water Quality Report,. https://www.mee.gov.cn/hjzl/shj/dbsszyb/.

- Tao, S.; Fang, J.; Ma, S.; Cai, Q.; Xiong, X.; Tian, D.; Zhao, X.; Fang, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, J.; et al. Changes in China’s Lakes: Climate and Human Impacts. National Science Review 2020, 7, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, S.M.; Oliver, S.K.; Lapierre, J.; Stanley, E.H.; Jones, J.R.; Wagner, T.; Soranno, P.A. Lake Nutrient Stoichiometry Is Less Predictable than Nutrient Concentrations at Regional and Sub-continental Scales. Ecological Applications 2017, 27, 1529–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zheng, Z.; Liu, G.; Chen, N.; Lei, S.; Du, C.; Xu, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, R.; Huang, C. Estimating Effects of Natural and Anthropogenic Activities on Trophic Level of Inland Water: Analysis of Poyang Lake Basin, China, with Landsat-8 Observations. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; McCarthy, M.J.; Paerl, H.W.; Brookes, J.D.; Zhu, G.; Hall, N.S.; Qin, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, M.; Hampel, J.J.; et al. Contributions of External Nutrient Loading and Internal Cycling to Cyanobacterial Bloom Dynamics in Lake Taihu, China: Implications for Nutrient Management. Limnology & Oceanography 2021, 66, 1492–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, N.; Zou, R.; Jiang, Q.; Liang, Z.; Hu, M.; Liu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H. Internal Positive Feedback Promotes Water Quality Improvement for a Recovering Hyper-Eutrophic Lake: A Three-Dimensional Nutrient Flux Tracking Model. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 772, 145505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCrackin, M.L.; Jones, H.P.; Jones, P.C.; Moreno-Mateos, D. Recovery of Lakes and Coastal Marine Ecosystems from Eutrophication: A Global Meta-analysis. Limnology & Oceanography 2017, 62, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, B.; Zhou, J.; Elser, J.J.; Gardner, W.S.; Deng, J.; Brookes, J.D. Water Depth Underpins the Relative Roles and Fates of Nitrogen and Phosphorus in Lakes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 3191–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ai, X.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ou, X.; Xia, C.; Liu, L. Climate and Land Use Changes Impact the Trajectories of Ecosystem Service Bundles in an Urban Agglomeration: Intricate Interaction Trends and Driver Identification under SSP-RCP Scenarios. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 944, 173828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guildford, S.J.; Hecky, R.E. Total Nitrogen, Total Phosphorus, and Nutrient Limitation in Lakes and Oceans: Is There a Common Relationship? Limnology & Oceanography 2000, 45, 1213–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolman, A.M.; Mischke, U.; Wiedner, C. Lake-type-specific Seasonal Patterns of Nutrient Limitation in German Lakes, with Target Nitrogen and Phosphorus Concentrations for Good Ecological Status. Freshwater Biology 2016, 61, 444–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widespread Global Increase in Intense Lake Phytoplankton Blooms since the 1980s | Nature. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-019-1648-7 (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Cheng, G.W.; Chen, Y.; Gao, W. Source apportionment of nitrogen and phosphorus in the lakes and reservoirs of Yangtze River Watershed from 2016 to 2019. Acta Scientiae Circumstantiae 2022, 42, 207–217. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, H.-a.; Wu, J.-l. Characteristics and mechanismes of water environmental changes in the lakes along the middle and lower reaches of Yangtze River. Advances in Water Science 2007, 18, 834–841. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Wu, X.; Finlayson, B.L.; Webber, M.; Wei, T.; Li, M.; Chen, Z. Variability and Trend in the Hydrology of the Yangtze River, China: Annual Precipitation and Runoff. Journal of Hydrology 2014, 513, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Quan, J.; Yin, J.; Liu, X.; Yuan, Z.; Ma, L. High-Resolution Maps of Intensive and Extensive Livestock Production in China. Resources, Environment and Sustainability 2023, 12, 100104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, J.; Li, M. Analysis on spatial and temporal changes of regional habitat quality based on the spatial pattern reconstruction of land use. Acta Geographica Sinica 2020, 75, 160–178. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.C.; Gong, J.; Zhang, S.X.; Ma, X.; Hu, B. Spatiotemporal Change of Landscape Biodiversity Based on InVEST Model and Remote Sensing Technology in the Bailong River Watershed. SCIENTIA GEOGRAPHICA SINICA 2018, 38, 979–986. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, R.; Chaplin-Kramer, R.; Wood, S.; Guerry, A.; Tallis, H.; Ricketts, T.; Nelson, E.; Ennaanay, D.; Wolny, S.; Olwero, N.; et al. InVEST User’s Guide; The Natural Capital Project, Stanford University, University of Minnesota, The Nature Conservancy, and World Wildlife Fund., 2018.

- Lai, J.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Peres-Neto, P.R. Generalizing Hierarchical and Variation Partitioning in Multiple Regression and Canonical Analyses Using the Rdacca.Hp R Package. Methods Ecol Evol 2022, 13, 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intensification of Phosphorus Cycling in China since the 1600s | PNAS. Available online: https://libyw.ucas.ac.cn/https/5Jy11EWbH4LLHFFILXUiUAcBuhdVMmcsDK/doi/abs/10.1073/pnas.1519554113 (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Dai, Z.; Du, J.; Zhang, X.; Su, N.; Li, J. Variation of Riverine Material Loads and Environmental Consequences on the Changjiang (Yangtze) Estuary in Recent Decades (1955−2008). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- JI Peng-fei, XU Hai, ZHAN Xu, ZHU Guang-wei, ZOU Wei, ZHU Meng-yuan, KANG Li-juan. Spatial-temporal Variations and Driving of Nitrogen and Phosphorus Ratios in Lakes in the Middle and Lower Reaches of Yangtze River. Environmental Science 2020, 41, 4030–4041. [Google Scholar]

- Rong, W.; Ke, Z.; Jianbao, L.; Xuhui, D.; Xiangdong, Y. Nanjing Institute of Geography and Limnology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing 210008, P.R. China; University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 101408, P.R. China The Importance of Lake Ecosystem Evolution for Anthropocene Research. Journal of Lake Sciences 2024, 36, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, C.; Zha, Y.; Li, Y.; Sun, D.; Lu, H.; Yin, B. Eutrophication of Lake Waters in China: Cost, Causes, and Control. Environmental Management 2010, 45, 662–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, D.-d.; Zhang, H.; Ren, X.-n.; Tian, X.-g.; Guo, M.-k.; Zhang, W.-p.; Yang, C.-j. Evaluation of Eutrophication and Analysis of Pollution Factors in Eutrophication and Pollution Factors in Typical Seasonal Rivers of Upper Yangtze River. Resources And Environment In The Yangtze Basin 2024, 33, 584–595. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, B.; Gao, G.; Zhu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Song, Y.; Tang, X.; Xu, H.; Deng, J. Lake Eutrophication and Its Ecosystem Response. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2013, 58, 961–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Doncaster, C.P.; Zheng, W.; Xu, M.; Yang, H.; Li, Y.; Cai, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, E.; Yang, X.; et al. High Phytoplankton Diversity in Eutrophic States Impedes Lake Recovery. Journal of Biogeography 2023, 50, 1914–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.W.; Xu, H.; Zhu, M.Y.; Zou, W.; Guo, C.; Ji, P.; Da, W.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, B. Changing characteristics and driving factors of trophic state of lakes in the middle and lower reaches of Yangtze River in the past 30 years. J. Lake Sci. 2019, 31, 1510–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Qin, B.; Gao, G. Effect of nutrient on periphytic aglae and phytoplankton. J. Lake Sci. 2007, 19, 125–130. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Qin, B.; Gao, G. Effect of nutrient on periphytic aglae and phytoplankton. J. Lake Sci. 2007, 19, 125–130. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, L.; Sun, G. Impacts of urbanization on watershed ecohydrological processes: progresses and perspectives. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2021, 41, 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Li, G. The effects of different components of the forest ecosystem on water quality in the Huoditang forest region, Qinling Mountain Range. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2007, 1838–1844. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, B.; Fu, L.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, S.; Chen, X.; Li, F.; Deng, Z.; Xie, Y. Spatiotemporal Change Detection of Ecological Quality and the Associated Affecting Factors in Dongting Lake Basin, Based on RSEI. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 302, 126995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, J.; Shen, A.; Liu, C.; Wen, B. Impacts of Ecological Land Fragmentation on Habitat Quality in the Taihu Lake Basin in Jiangsu Province, China. Ecological Indicators 2024, 158, 111611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Huang, X.; Chen, H.; Godfray, H.C.J.; Wright, J.S.; Hall, J.W.; Gong, P.; Ni, S.; Qiao, S.; Huang, G.; et al. Managing Nitrogen to Restore Water Quality in China. Nature 2019, 567, 516–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, H.; Yao, M.; Dahlgren, R.A.; Chen, D. Long-Term (1980–2015) Changes in Net Anthropogenic Phosphorus Inputs and Riverine Phosphorus Export in the Yangtze River Basin. Water Research 2020, 177, 115779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashemi, F.; Olesen, J.E.; Dalgaard, T.; Børgesen, C.D. Review of Scenario Analyses to Reduce Agricultural Nitrogen and Phosphorus Loading to the Aquatic Environment. Science of The Total Environment 2016, 573, 608–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, E.; Michalak, A.M. Precipitation Dominates Interannual Variability of Riverine Nitrogen Loading across the Continental United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 12874–12884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DU Jing, QIAN Yu-ting, XU Yueding, ZHANG Jian-ying, CHANG Zhi-zhou. RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN WATER QUALITY OF SURFACE WATER AND BIOCHEMICAL CHARACTERS OF CYANOBACTERIAL BIOMASS IN THE TAIHU LAKE AND THE DIANCHI LAKE. RESOURCES AND ENVIRONMENT IN THE YANGTZE BASIN 2013, 22, 212–218. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; et al. Estimation of permissible pollution bearing capacity and aquaculture pollution load of Changhu Lake. Water Resources Protection 2015, 31, 78–83. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.H.; Peng, Z.H.; Jiao, H.Z.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y.G. External pollution source load and contribution of urban eutrophic lakes—Taking Lake Houguanhu of Wuhan as an example. J. Lake Sci. 2020, 32, 941–951. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, C.; Liu, L.; Li, H.; Peng, D.; Wu, Y.; Xia, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, Q. A Data-Driven Framework for Spatiotemporal Characteristics, Complexity Dynamics, and Environmental Risk Evaluation of River Water Quality. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 785, 147134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin yuanyuan; Peng shuangyun; Lin zhiqiang; LI dingpu; LI ting; ZHU yilin; HUANG bangmei. Spatiotemporal Changes and Multi-scale Driving Mechanism Analysis of Nitrogen and Phosphorus Export in Yunnan Province from 2000 to 2020. Environmental Science 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.P.; Wang, P.; Xu, Q.Y.; Shu, W.; Ding, M.J.; Zhang, H.; Zeng, T. Influence of Land Use on Carbon, Nitrogen and Phosphorus in Water of Yuan River Basin. Research of Environmental Sciences 2021, 34, 2132–2142. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Peng, L.; Wu, F. The Impacts of Impervious Surface on Water Quality in the Urban Agglomerations of Middle and Lower Reaches of the Yangtze River Economic Belt From Remotely Sensed Data. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2021, 14, 8398–8406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ma, J.; Guo, J.; Paerl, H.W.; Brookes, J.D.; Xiao, Y.; Fang, F.; Ouyang, W.; Lunhui, L. Water Quality Trends in the Three Gorges Reservoir Region before and after Impoundment (1992–2016). Ecohydrology & Hydrobiology 2019, 19, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GAO yongxia; ZHU guangwei; HE ranarn; WANG fang.Variation of Water Quality and Trophic State of Lake Tianma,Chian. Environmental Science 2009, 30, 673–679. https://doi.org/10.13227/j.hjkx.2009.03.049. GAO yongxia; ZHU guangwei; HE ranarn; WANG fang.Variation of Water Quality and Trophic State of Lake Tianma,Chian. Environmental Science, 2009, 30, 673–679.

- Qin, B. Shallow lake limnology and control of eutrophication in Lake Taihu. J. Lake Sci. 2020, 32, 1229–1243. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, Y.; Bu, X.; Chen, J.; Zhou, F.; Chen, L.; Liu, M.; Tan, X.; Yu, T.; Zhang, W.; Mi, Z.; et al. Estimation of Nutrient Discharge from the Yangtze River to the East China Sea and the Identification of Nutrient Sources. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2017, 321, 728–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Wang, M.; Kroeze, C.; Chen, X.; Ma, L.; Chen, X.; Shi, X.; Strokal, M. Nitrogen in the Yangtze River Basin: Pollution Reduction through Coupling Crop and Livestock Production. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 17591–17603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Data Type | Year | Data Format | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basin, lake, actual evapotranspiration, depth, hydraulic retention time, and longitude/latitude data | - | HydroATLAS | HydroSHEDS (https://www.hydrosheds.org/) |

| Temperature | 2021 | Raster | Resolution: 1 km Unit: degrees Celsius (°C) (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/) |

| Precipitation | 2021 | Raster | Resolution: 1 km Unit: m (http://www.nesdc.org.cn/) |

| Habitat Quality | 2021 | Raster | Resolution: 10 m × 10 m Value range: 0 to 1 |

| Wind Speed | 2020 | Raster | Resolution: 1 km Unit: m/s (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/) |

| Livestock | 2017 | Raster | Resolution: 1 km Values represent the stock population for beef cattle, dairy cattle, sheep, and poultry (units: heads) and the slaughter population for pigs (units: number slaughtered). Livestock Units (LSU) are calculated as: 1 LSU = 500 kg dairy cow = 0.5 beef cattle = 0.35 pigs = 0.1 sheep/goats = 0.129 poultry., data processed via MAPS model |

| Aquaculture Production | 2021 | CSV | China Statistical Yearbook (https://www.stats.gov.cn/) |

| Nitrogen Fertilizer | 2021 | CSV | China Statistical Yearbook (https://www.stats.gov.cn/) |

| Land Use Data | 2021 | Raster | Resolution: 10 m × 10 m (https://livingatlas.arcgis.com/) |

| Water Quality and Nutrient Data | 2021 | CSV | China National Environmental Monitoring Centre (https://www.cnemc.cn/) |

| Lake Trophic Level Index | 2021 | Constant | National Surface Water Quality Report (https://www.mee.gov.cn/hjzl/shj/dbsszyb/) |

| Land Use Type | Maximum Influence Distance (km) | Weight | Spatial Decay Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cultivated Land | 1.50 | 0.60 | Linear |

| Forest Land | 1.50 | 0.60 | Linear |

| Grassland | 1.50 | 0.60 | Linear |

| Water Body | 1.50 | 0.60 | Linear |

| Built-Up Area | 6.00 | 1.00 | Exponential |

| Unutilized Land | 2.00 | 0.40 | Linear |

| Land Use Type | Habitat Suitability | Relative Sensitivity to Threat Factors | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultivated Land | Forest Land | Grassland | Water Body | Built-Up Area | Unutilized Land | ||

| Cultivated Land | 0.40 | 0.25 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.65 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| Forest Land | 1.00 | 0.80 | 1 | 0.9 | 0.85 | 0.8 | 1 |

| Grassland | 0.80 | 0.70 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.85 | 0.7 | 0.8 |

| Water Body | 0.70 | 0.65 | 0.85 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.65 | 0.75 |

| Built-Up Area | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Unutilized Land | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| Parameter | Class I | Class II | Class III | Class IV | Class V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Nitrogen (≤) | 0.2 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 2.0 |

| Total Phosphorus (≤) | 0.01 | 0.025 | 0.05 | 0. 1 | 0.2 |

| Region | Parameter | Total Nitrogen (mg/L) | Total Phosphorus (µg/L) | TN/TP | TLI | HQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entire Basin | Range | 0.1–3.4 | 6.1–139.3 | 8.1–216.3 | 14.1–65.4 | 0–0.5 |

| Mean | 1.3 | 40.4 | 45.2 | 43.5 | 0.2 | |

| Standard Deviation | 0.9 | 31.8 | 47.3 | 11.7 | 0.1 | |

| Water Quality Range | Class I–V | Class I–V | ||||

| Upper | Range | 0.1–3.4 | 6.1–62.2 | 16.1–216.3 | 14.1–65.4 | 0.1–0.5 |

| Mean | 1.3 | 26.1 | 66.2 | 43.5 | 0.2 | |

| Standard Deviation | 0.9 | 16.0 | 68.2 | 11.7 | 0.1 | |

| Water Quality Range | Class I–V | Class I–III | ||||

| Middle | Range | 0.7–1.9 | 6.4–139.3 | 8.8–139.6 | 25.2–59.4 | 0.0–0.3 |

| Mean | 1.1 | 44.2 | 44.8 | 36.6 | 0.2 | |

| Standard Deviation | 0.3 | 37.9 | 39.9 | 12.8 | 0.1 | |

| Water Quality Range | Class III–V | Class I–V | ||||

| Lower | Range | 0.5–1.7 | 6.4–139.3 | 8.1–109.0 | 28.6–62.6 | 0.1–0.4 |

| Mean | 1.0 | 48.6 | 29.3 | 47.4 | 0.2 | |

| Standard Deviation | 0.3 | 34.3 | 25.5 | 9.9 | 0.1 | |

| Water Quality Range | Class II–III | Class I–V | ||||

| Range | 0.5–1.7 | 77.5–138.6 | 8.1–29.3 | 28.6–63.6 | 0.1–0.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).