1. Introduction

Aging is often accompanied by a decline in cognitive function, which entails significant redox imbalance towards increase oxidation in brain cells [

1]. The ryanodine receptor (RyR) calcium channels partake in hippocampal functions, including synaptic plasticity, considered the cellular basis of learning and memory, and in learning and spatial memory processes [

2]. The redox state of cysteine residues modulates RyR channel activation, enabling these channels to act as cellular redox sensors [3-6]. In particular, RyR channel redox state determines the three types of response (low, moderate, or high) to activation by cytoplasmic free calcium concentration ([Ca

2+]) of single RyR channels from rat brain cortex endoplasmic reticulum (ER) [7-10]. Thus, addition of sulfhydryl (SH) modifying agents added while recording channel activity causes a single low activity channel to adopt sequentially and stepwise, first the moderate and then the high activity response [

8]. Furthermore, S-nitrosylation and/or S-glutathionylation of SH residues of skeletal or cardiac RyR channels enhance Ca

2+-induced Ca

2+ release (CICR) kinetics induced by micromolar [Ca

2+] [11-14]. Furthermore, Ca

2+ release mediated by hippocampal type-2 RyR (RyR2) channels is required for spatial learning and memory tasks [

15].

Our working hypothesis is that age-induced redox imbalance toward increased oxidation increases the activation by [Ca2+] of RyR channels; the resulting abnormal increase in cytoplasmic [Ca2+] would lead to defective performance in a spatial memory task. To test this hypothesis, we studied the performance in the Oasis maze of young (3-month-old) and aged (22-month-old) male rats, and some of them fed with the antioxidant agent N-acetylcysteine (NAC), and subsequently determined in vitro the responses to cytoplasmic [Ca2+] of single RyR channels from the ER isolated from their respective hippocampal tissues.

2. Results

2.1. Effects of Age on the Ca2+-Induced Responses of RyR Channels from Rat Brain Cortex

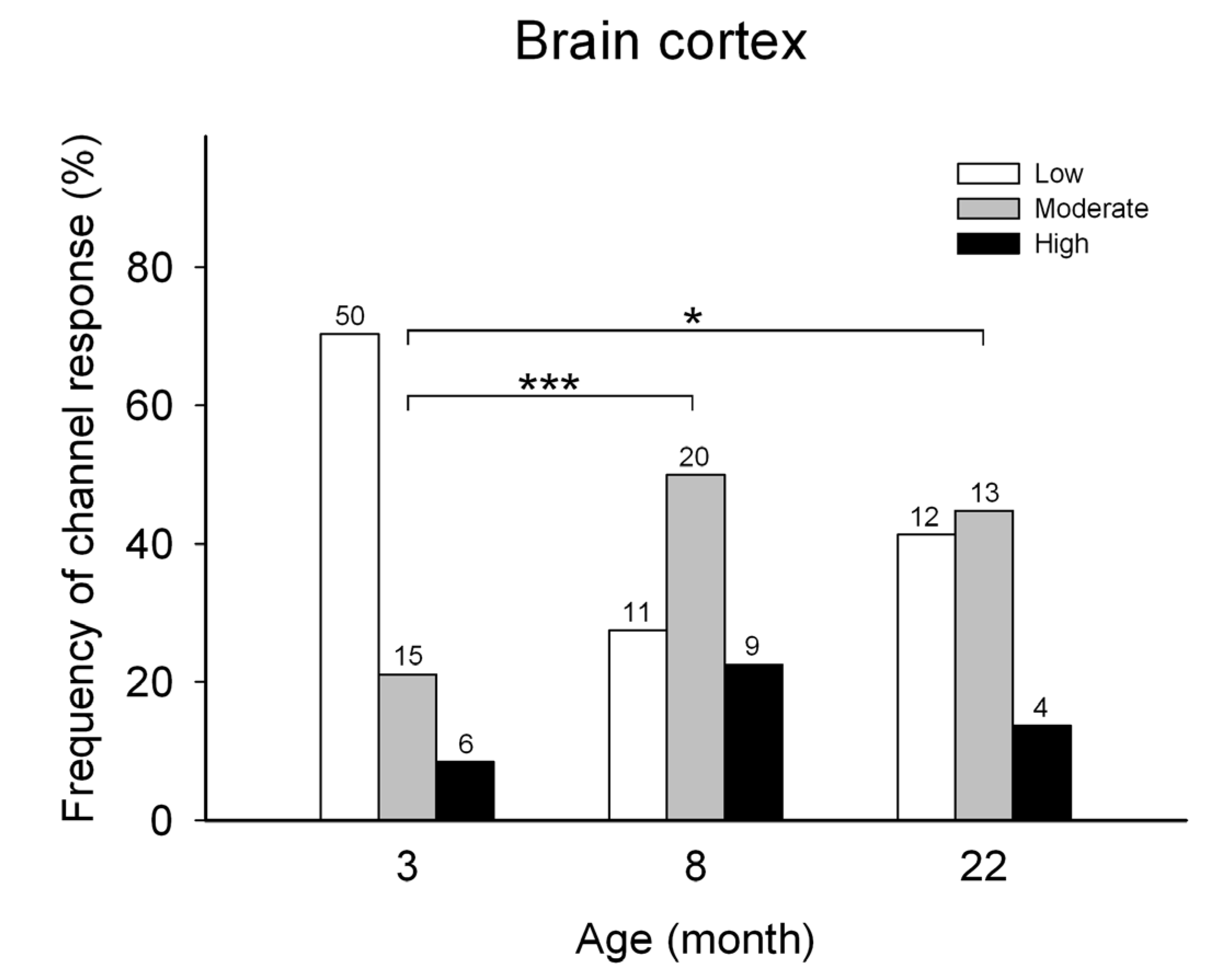

The effects of age on the frequency of obtaining the three different responses to cytoplasmic [Ca

2+] of single RyR channels was first tested in channels isolated from rat brain cortex of male rats with different ages (

Figure 1). The RyR channels obtained from rat brain at all three ages studied displayed only three different response patterns, and were readily classified into low, moderate, or high activity channels. The RyR channels from the brain cortex of 3-month-old rats, showed most frequently the low activity response (70.4%), followed by moderate (21.1%) and high (8.5%) activity responses. In contrast, single RyR channels from 22-month-old rats, displayed with similar frequency the moderate (44.8%) and the low (41.8%) activity responses, followed by the high activity response (13.8%), respectively (see

Figure 1).

Accordingly, we chose the ages of 3 and 22 months in the training experiments in the Oasis maze and for single hippocampal RyR channel analysis.

2.2. Effects of Age on the Responses to [Ca2+] of single Hippocampal RyR Channels

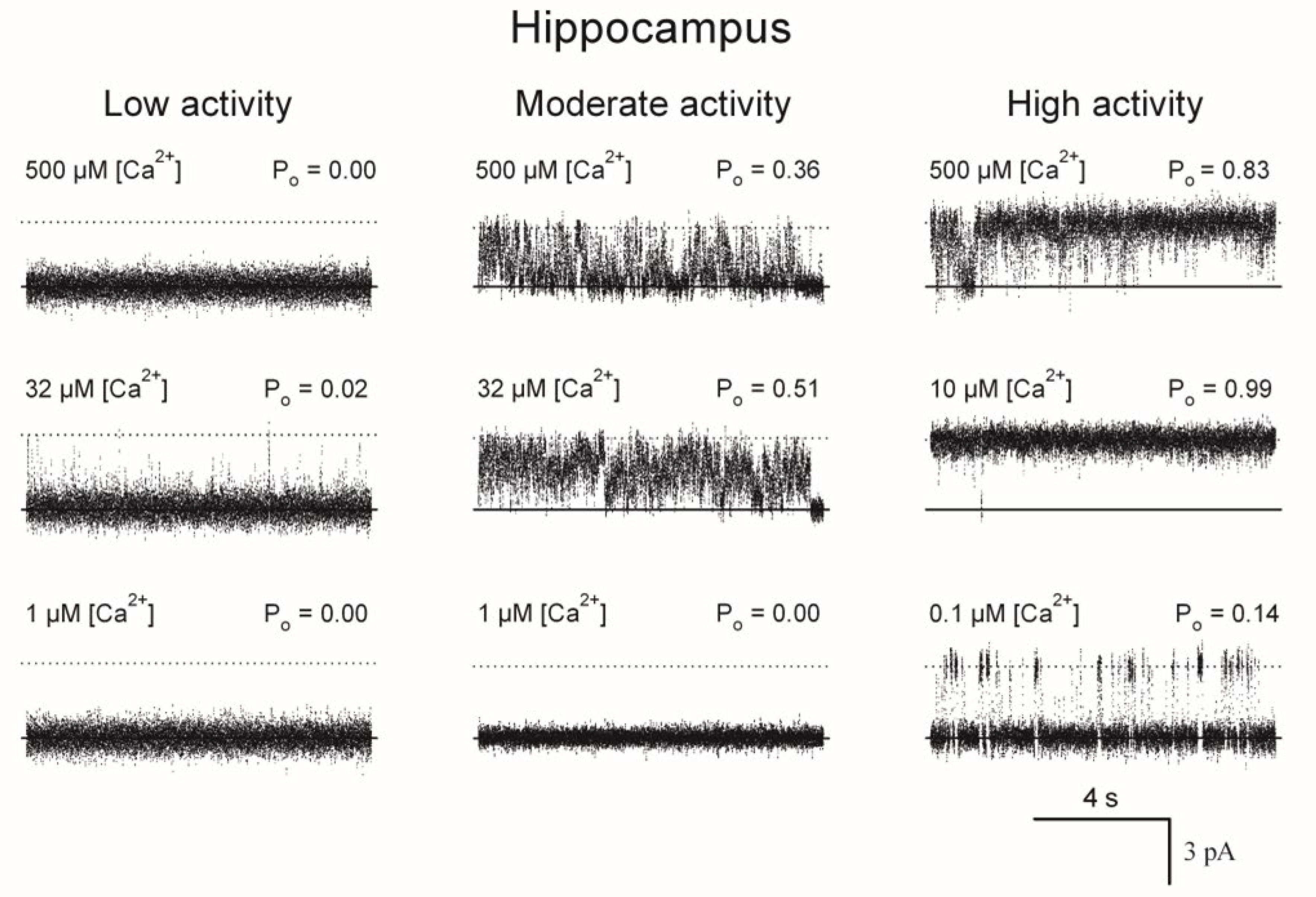

Representative current recordings taken from individual experiments showing the three different responses to [Ca

2+] of single RyR channels from rat hippocampus are illustrated in

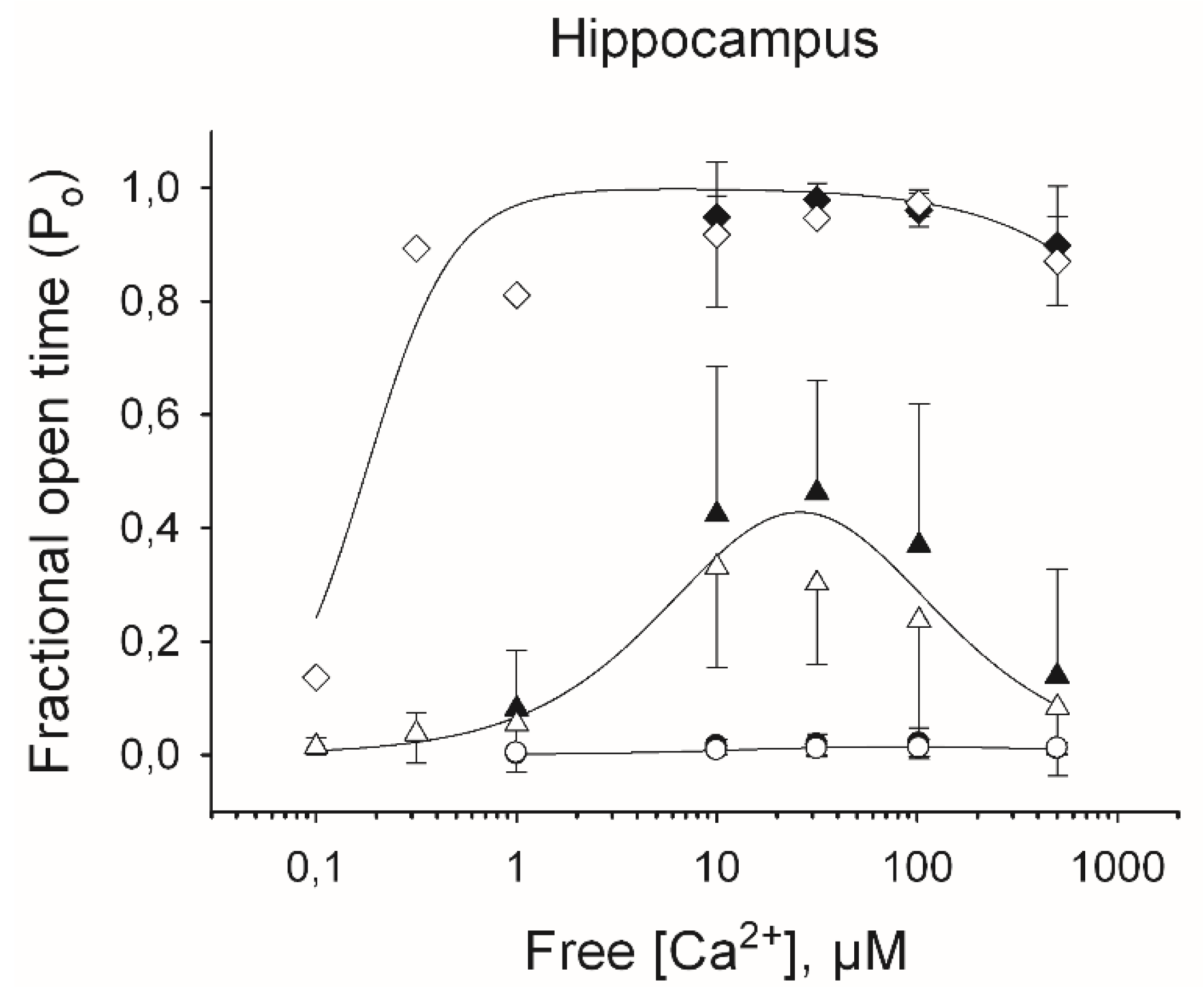

Figure 2, whereas the Ca

2+-dependence of the fractional open time (P

o) values are depicted in

Figure 3. As illustrated in

Figure 3, the three responses to [Ca

2+] displayed by hippocampal RyR channels from both young and aged rats were analogous. The curve-fitting of the data obtained with single RyR channels with the same Ca

2+ response from either aged or young rats yielded similar parameter values. Hence, the continuous lines in

Figure 3 were obtained using all data displayed by RyR channels from both young and aged rats.

Of note, the apparent affinities for activation and inhibition by Ca

2+ were different for each channel response (

Table 1). Low activity channels displayed significantly higher K

a values than moderate activity channels, and moderate activity channels exhibited higher K

a values than high activity channels. Conversely, the K

i values for low activity channels were lower than those exhibited by moderate activity channels, whereas moderate activity channels displayed lower K

i values than high activity channels (

Table 1,

Figure 3).

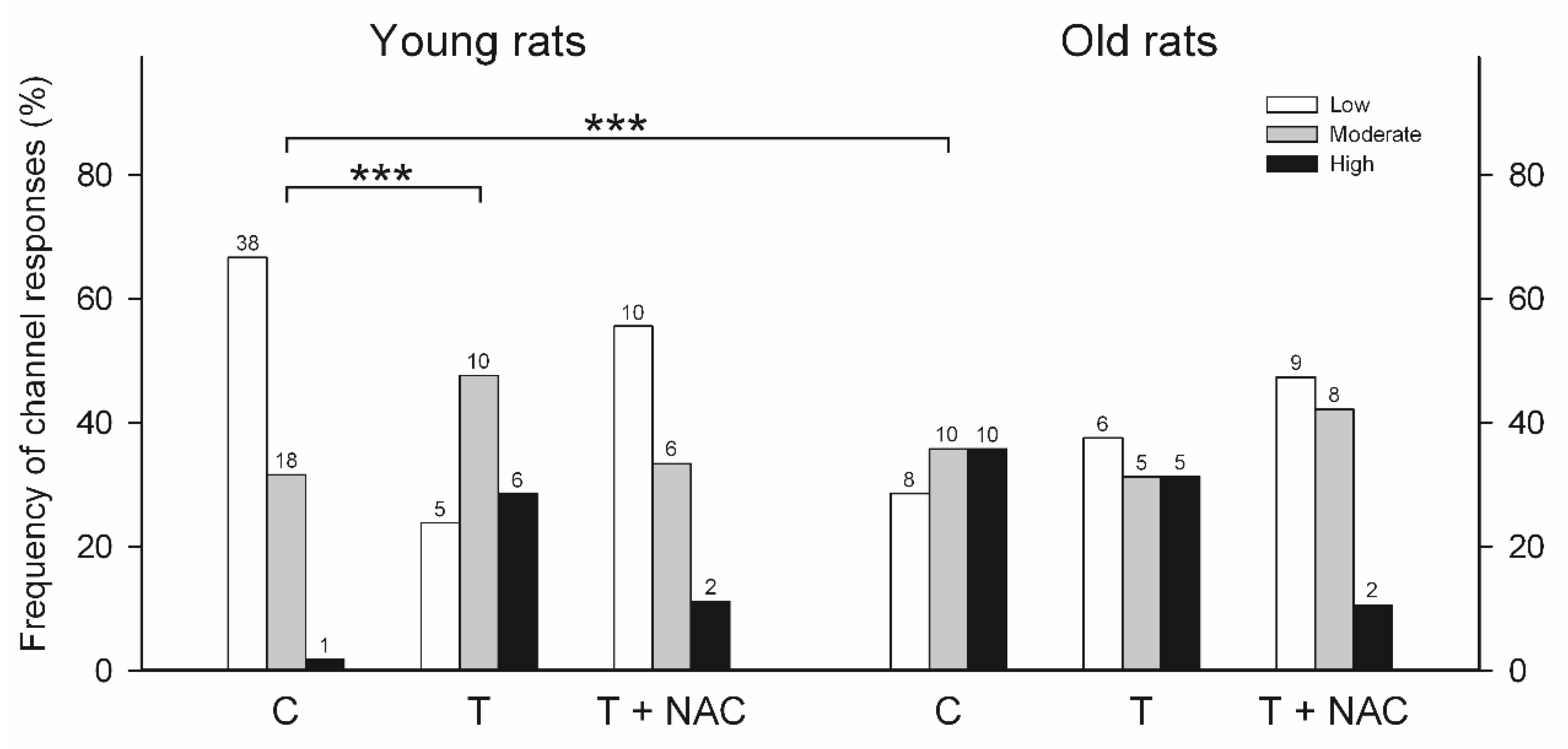

Although the three types of responses to cytoplasmic [Ca

2+] were undistinguishable for single RyR channels obtained from either young or aged rats, their frequencies of emergence were quite different (

Figure 4, control histograms). In young rats, hippocampal RyR channels displayed most frequently the low activity response (66.7%), followed by the moderate (31.6%) and the high (1.7%) activity responses, whereas channels from aged rats displayed with similar frequency the moderate (35.7%) and the high (35.7%) activity responses, followed by the low (28.6%) activity response. Therefore, as shown by RyR channels form rat brain cortex, aging induced a marked change in the emergence of the different channel responses: it reduced the fraction of low activity channels from 66.7 to 28.6% and increased the fraction of high activity channels from 1.7 to 35.7%.

Although the three types of response to cytoplasmic [Ca

2+] were undistinguishable for single RyR channels obtained from either young or old rats, their frequencies of emergence were quite different (

Figure 4, control histograms). In young rats, RyR channels displayed most frequently the low activity response (66.7%), followed by moderate (31.6%) and high (1.7%) activity responses, whereas channels from old rats displayed with similar frequency the moderate (35.7%), the high (35.7%) activity responses, followed by the low (28.6%) activity response. Therefore, aging induced a marked change in the emergence of the different channel responses: it reduced the fraction of low activity channels from 66.7 to 28.6% and increased the fraction of high activity channels from 1.7 to 35.7%.

Parameter values ± SE were obtained by fitting all individual data obtained with single channels from the hippocampus of young and old rats that displayed low, moderate, or high activity to the equation 1 (see Materials and Methods).

a Significant differences (p < 0.001) between corresponding parameter values were found. Parameter values of moderate activity channels were compared with the respective values of low activity channels. Values of high activity channels from were compared with the respective values of moderate activity channels.

bParameter was fixed to the indicated value for data fitting [

10].

2.3. Effects of Age on Spatial Learning and Memory, and Protective Effects of NAC Feeding

To test the effects of aging on spatial learning and memory, young and aged rats were trained and tested in the Oasis maze (see Material and Methods). First, the behavior of young and aged rats on a learning task was explored. To this aim, the position of the reward well (water) was changed in each session. As illustrated in

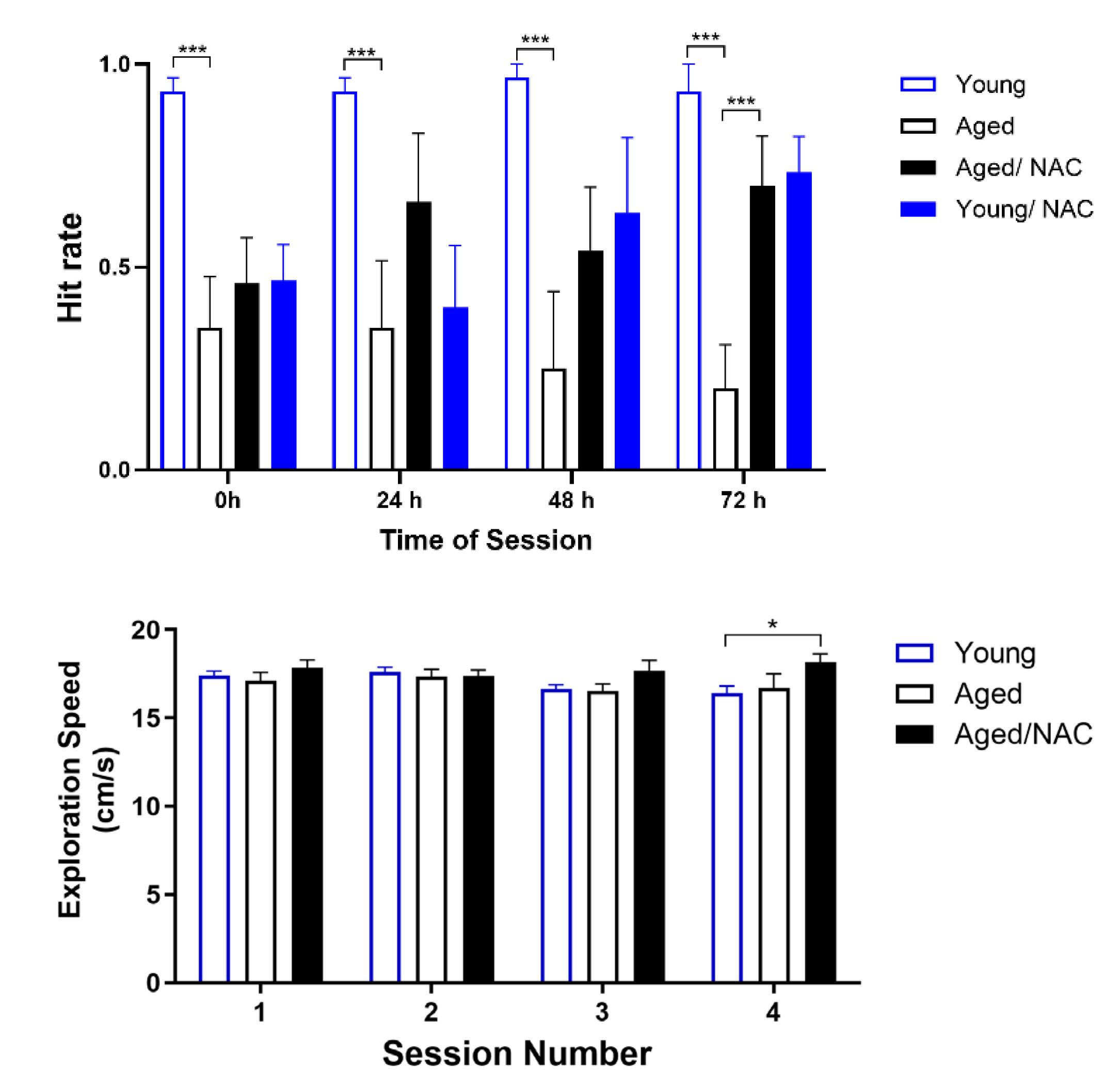

Figure 5A, the hit rate, defined as the number of times the rat found the reward during daily sessions composed of 10 trials, was significantly different between young and aged rats at all times tested, from 24 h to 48 h and 72 h. Thus, young rats always found the reward in each of the three test sessions, with a hit rate value = 1. In contrast, aged rats displayed significant defects in learning the task, reaching hit rate average values < 0.5 in all test sessions.

Of note, NAC-fed rats displayed significant improvements in hit rate values, which at the sessions performed at 72 h were significantly higher than those displayed by aged rats not fed with NAC (

Figure 5A). To rule out mobility defects in aged rats, the speed at which rats searched for the reward was determined as well. As illustrated in

Figure 5B, both young and aged rats, including those fed with NAC, displayed similar speed values when looking for the reward.

Next, we explored the behavior of young and aged rats on a memory task. To achieve this aim, the position of the water-containing reward well was the same in each session. As illustrated in Figure 6A, both young and NAC-fed aged rats displayed significantly higher hit rates values that aged rats in all three test sessions performed at 24 h, with values close to 1 in the third session. In contrast, aged rats displayed hit rate values < 0.5 in all three test sessions. Both young and aged rats, including those fed with NAC, displayed similar speed values when looking for the reward (Figure 6B).

2.4. Effects of Training on RyR Channel Responses to Cytoplasmic [Ca2+].

As a final step, we studied the effects of training on the frequency of appearance of the three different RyR channel responses to cytoplasmic [Ca

2+] in hippocampal channels from young and aged trained rats (

Figure 4, trained histograms). In young rats, training induced a significant change (p < 0.001) in the emergence of RyR channel responses, reducing the low activity response from 66.7% to 23.8% and increasing the high activity response from 1.7 to 28.6%. In contrast, in aged rats training did not modify the frequency of appearance of the responses to [Ca

2+] of RyR channels; in both control and trained rats the frequency of obtaining low, moderate or high activity responses was around one third (

Figure 4).

The administration of NAC to both aged and young rats produced after training a similar frequency of appearance of the three responses to cytoplasmic [Ca

2+] in hippocampal RyR channels (

Figure 4).

3. Discussion

3.1. Summary of Main Findings.

In aged male rats (22-month-old), hippocampal RyR channels showed a twenty-one-fold increase in the frequency of finding RyR channels with high activity response to Ca2+ and a two-fold reduction in the low activity response, when compared with young rats (3-month-old). Aged rats displayed significant defects in learning and memory tests, with hit rate values < 0.5, significantly lower than young rats, reaching hit rates near 1. NAC feeding reversed both age-dependent defects in learning and memory and produced in both aged and young rats a similar frequency pattern of responses to cytoplasmic [Ca2+] in RyR channels after training.

3.2. Effects of Age on the Responses to [Ca2+] of single RyR Channels.

Aging did not modify the channel responses to cytoplasmic [Ca2+], which remained as three different responses, but markedly increased the probability of appearance of RyR channels with the high activity response and reduced the probability of appearance of channels with low activation. This change in channel response may be the result of RyR redox modifications, which are known to modify RyR activity [3-6,12-17]. Oxidation or alkylation of critical SH residues with dithiodipyridine or thimerosal, respectively, causes single RyR channel from rat brain cortex to display higher degrees of activation in response to Ca2+ (8,9-11).

The results presented here indicate that hippocampal RyR channels from aged rats are more oxidized, agree with previous findings showing higher oxidation levels of the RyR2 channel protein isolated from the hippocampus of aged rats compared to young rats [

18]. In addition, the present results indicate that NAC feeding largely reversed RyR channel oxidation state, as evidenced by the decreased frequency of finding channels with the high activity response to Ca

2+ displayed by aged rats. Based on these findings, it is proposed that NAC feeding may be a useful strategy to counteract the increased RyR channel oxidation, which when reaching high levels presumably impacts negatively on hippocampal learning and memory processes.

As reported previously, ischemia increases the production of ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) [19-22]. Both ROS and RNS participate in normal and pathologic redox signaling and may modify RyR, among other protein targets with cysteine residues highly reactive at physiological pH [

23]. S-glutathionylation and/or S-nitrosylation have been reported in skeletal RyR1 and cardiac RyR2 [12-14]. Previously, we reported that the RyR2 and RyR3 isoforms present in rat brain cortex exhibit endogenous levels of S-glutathionylation and S-nitrosylation, yet only RyR2 increased its S-glutathionylation and S-nitrosylation levels after ischemia. In contrast, incubation of control ER vesicles with NADPH enhanced S-glutathionylation of both isoforms [

10]. These results suggest the existence of intracellular compartmentalization of ROS/NO production in brain tissue, which may selectively modify RyR2 and RyR3 isoforms, because they are differentially distributed in rodent brain cortex [

24] and hippocampus [

25]. Accordingly, we propose that the RyR2 isoform may be more readily accessible to the cellular sources of ROS that are activated by ischemia and aging. Hydrogen peroxide, synthesized from superoxide anion during ER incubation with NADPH, could lead to S-glutathionylation of RyR isoforms in the presence of glutathione via a sulfenic acid residue intermediate [

26]. In fact, hydrogen peroxide produces S-glutathionylation of RyR in hippocampal neurons in culture and in skeletal SR vesicles incubated in the presence of glutathione [27-29].

3.3. Effects of Age on Spatial Learning and Memory, and Protective Effects of NAC Feeding.

Previous studies reported RyR2/RyR3 up-regulation and increased RyR2 oxidation levels in aged rat hippocampus [

18], which are likely to generate anomalous Ca

2+ signals that may contribute to the well-known impairments in hippocampal LTP and spatial memory that take place during aging. Here we confirm that aged rats displayed significant defects in the performance of learning and memory tasks in the Oasis maze. Moreover, direct injections into the hippocampus of amyloid beta peptide oligomers (AβOs), which are causative agents of Alzheimer disease, by engaging oxidation-mediated reversible pathways increase single RyR2 channel activation by Ca

2+ and cause considerable spatial memory deficits; previous NAC feeding prevents these noxious effects of AβOs [

30]. In agreement, we report here that previous NAC feeding significantly reversed the defective cognitive responses displayed by aged rats. These results indicate that feeding an antioxidant agent such as NAC, a glutathione precursor, may be an eventual protective strategy to counteract the learning and memory defects displayed by aged humans.

3.4. Effects of Age on the Responses to [Ca2+] of Single RyR Channels from Young and aged Rats Trained in a Memory Task; Effects of NAC Feeding.

As reported here, hippocampal RyR channels from young rats trained in a memory task displayed a modest but significant increase in the moderate and the high activity responses to cytoplasmic [Ca

2+]. In contrast, trained aged rats did not display significant changes in the distribution of the three RyR channel responses to Ca

2+ when compared to untrained aged rats, an indication that training did not increase further RyR channel oxidation state in aged rats. Of note, trained rats previously fed with NAC displayed a reduction in the frequency of appearance of the high activity response, accompanied by an increase in frequencies of emergence of the low and the moderate activity responses This frequency distribution is similar to that displayed by NAC-treated and trained young rats. These novel results suggest that memory training results in increased hippocampal ROS levels, which moderately increase RyR channel oxidation state, a response that would favor RyR-mediated CICR, which is required for hippocampal synaptic plasticity, learning and memory processes [

2].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

Sprague-Dawley juvenile (7 weeks) and aged (21 months) male rats were procured from the Animal Care Facility of the Faculty of Medicine, Universidad de Chile. Rats were individually housed in a controlled environment with a 12 h light-dark cycle at 21-23°C, with food and water ad libitum, except when indicated otherwise. All animals were handled daily for 1 week before the beginning of the training sessions. The experimental protocols used in this work complied with the “Guidelines for the Care and Use of Mammals in Neuroscience and Behavioral Research,” The National Academies Press, Washington, DC, and were approved by the Bioethics Committee on Animal Research, Faculty of Medicine, Universidad de Chile (protocol #CBA 0618 MED-UCH).

4.2. NAC Feeding Protocol.

Juvenile and aged rats were fed daily for 21 consecutive days with commercial jelly (1 ml) containing either the antioxidant NAC (200 mg/kg) or vehicle. This oral NAC feeding protocol was maintained during all subsequent procedures, including pre-training and testing in the Oasis maze task.

4.3. Spatial Memory Training and Evaluation.

The different groups of rats, restricted of water to enhance motivation behavior, were exposed to the spatial memory task in the Oasis maze, a dry-land version of the Morris water maze [

31]. All animals were subjected to water restriction for 23 h before the start of each pre-training or training session; water was provided ad libitum for 1 h after these sessions. All rats were pre-trained for 3 days in the Oasis maze, followed by a training period of 6 days. Water-restricted rats were pre-trained during three consecutive daily sessions to familiarize the animal with the testing environment (circular arena provided with visual cues) and the search for the reward (water) in 21 equidistant distributed wells, all wells contained the reward. The ensuing training tasks entailed searching for the reward in one out of 21 wells during six daily sessions. Each session encompassed 10 trials of 1 min duration each, performed at 20–30 s intertrial intervals. For the learning evaluation the reward was placed in a different well in each session but was kept in the same position during the 10 trials performed in each session. These sessions were conducted at increasing intervals: 24 h between Sessions 1 and 2, 48 h between Sessions 2 and 3, and 72 h between Sessions 3 and 4. During the memory evaluation, the reward was placed in the same well across all sessions and trials. The three sessions were conducted at regular 24 h intervals. Animal behavior was recorded with a video camera in the zenithal position. The position of the animal was monitored continuously during the tests, and the navigation trajectory was reconstructed and analyzed with a customized MATLAB (MathWorks) routine. One hour after the end of the sixth session, animals underwent euthanasia by decapitation, and the hippocampus was collected for determination of RyR single channel activity.

4.3. Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± SE. Statistical analysis between groups was performed with Two-way ANOVA, One-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post hoc test, as indicated in the respective figure legends. Comparison between two groups was performed by two-tailed Student’s t-test. All statistical analyses were performed using Sigma Plot version 12.0.

4.4. Determination of RyR Single Channel Activity

The rats were decapitated with guillotine and their brains quickly removed. Brain cortex and the whole hippocampus were dissected [

2,

7,

10,

15]. Cleaned dissected tissue was homogenized in sucrose buffer with protease inhibitors (0.3 mM sucrose, 20 mM MOPS Tris, pH 7.0, 0.4 mM benzamidine, 10 mg/ml trypsin inhibitor; 10 mg/ml pepstatin) and centrifuged at 5,000 g during 20 min. The supernatants were centrifuged at 100,000 g for 1 h; the resulting pellets were resuspended in sucrose buffer with protease inhibitors and frozen in aliquots at -80 °C.

During channel recording at 22 ± 2 °C, the cis-(cytoplasmic) solution contained 0.5 mM Ca2+-HEPES, and 225 mM HEPES–Tris, pH 7.4, while the trans (intra-reticular) solution contained 40 mM Ca2+-HEPES, 15 mM Tris-HEPES, pH 7.4. The lipid bilayer was held at 0 mV. Current data were filtered at 400 Hz (-3 dB) using an eight-pole low-pass Bessel type filter (902 LPF; Frequency Devices) and digitized at 2 kHz with a 12-bit analog-to-digital converter (LabMaster DMA Interface; Scientific Solutions) using the AxoTape (Molecular Devices) commercial software. Fractional open time (Po) values were computed using the pClamp (Molecular Devices) commercial software. RyR channels were classified as low (Po < 0.1 at all [Ca

2+] tested), moderate (Po > 0.1 in the [Ca

2+] range of 10 - 100 µM, with reduction in Po at 500 µM [Ca

2+]), or high (Po near 1.0 in the range 3- 500 µM [Ca

2+]) activity channels [

7,

9,

11]. Data are expressed as mean ± SE. Comparison between frequency histograms was performed by the Chi-Squared test.

The Ca

2+-dependence of single RyR channel P

o values were fitted with the following general function [

11]:

Po = Po max * [Ca2+]n / ([Ca2+]n + Kan) * Ki / ([Ca2+] + Ki) (1)

Equation 1 gives Po values as a function of cis-[Ca2+]. Po max corresponds to the theoretical Po value of maximal activation by cis-[Ca2+]. Ka and Ki correspond to the Ca2+ concentrations for half-maximal activation and inhibition, respectively, of the channel activity, and n is the Hill coefficient for Ca2+ activation.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the skilled technical assistance provided by Luis Montecinos.).

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”.

References

- Zavadskiy, S.; Sologova, S.; Moldogazieva, N. Biochimie . Oxidative distress in aging and age-related diseases: Spatiotemporal dysregulation of protein oxidation and degradation. 2022, 195, 114–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, C. , Paula-Lima, A. RyR-mediated calcium release in hippocampal health and disease. Trends Mol Med. 2024, 30, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eu, J.P.; Sun, J.; Xu, L.; Stamler, J.S.; Meissner, G. The skeletal muscle calcium release channel: coupled O2 sensor and NO signaling functions. Cell 2000, 102, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, R.; Stangler, T.; Abramson, J.J. Skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor is a redox sensor with a well-defined redox potential, which is sensitive to channel modulators. J Biol Chem. 2000, 275, 36556–36561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessah, I.N.; Kim, K.H.; Feng, W. Redox sensing properties of the ryanodine receptor complex. Front Biosci. 2002, 7, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, C.; Donoso, P.; Carrasco, M.A. The ryanodine receptors Ca2+ release channels: cellular redox sensors? IUBMB Life. 2005, 57, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marengo, J.J.; Bull, R.; Hidalgo, C. Calcium dependence of ryanodine-sensitive calcium channels from brain cortex endoplasmic reticulum. FEBS Lett. 1996, 383, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, J.J.; Hidalgo, C.; Bull, R. Sulfhydryl oxidation modifies the calcium dependence of ryanodine-sensitive calcium channels of excitable cells. Biophys J. 1998, 74, 1263–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bull, R.; Marengo, J.J.; Finkelstein, J.P.; Behrens, M.I.; Alvarez, O. SH oxidation coordinates subunits of rat brain ryanodine receptor channels activated by calcium and ATP. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003, 285, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bull, R.; Finkelstein, J.P.; Humeres, A.; Behrens, M.I.; Hidalgo, C. Effects of ATP, Mg2+, and redox agents on the Ca2+ dependence of RyR channels from rat brain cortex. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007, 293, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bull, R.; Finkelstein, J.P. , Gálvez, J.; Sánchez, G.; Donoso, P.; Behrens, M.I.; Hidalgo, C. Ischemia enhances activation by Ca2+ and redox modification of ryanodine receptor channels from rat brain cortex. J Neurosci. 2008, 28, 9463–9472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, C.; Aracena, P.; Sánchez, G.; Donoso, P. Redox regulation of calcium release in skeletal and cardiac muscle. Biol Res. 2000, 35, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aracena, P.; Sánchez, G.; Donoso, P.; Hamilton, S.L. ; Hidalgo, C: S-glutathionylation decreases Mg2+ inhibition and S-nitrosylation enhances Ca2+ activation of RyR1 channels. J Biol Chem. 2003, 278, 42927–42935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, G.; Pedrozo, Z.; Domenech, R.J.; Hidalgo, C.; Donoso, P. Tachycardia increases NADPH oxidase activity and RyR2 S-glutathionylation in ventricular muscle. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005, 39, 982–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- More, J.Y. , Bruna, B.A., Lobos, P.E., Galaz, J.L., Figueroa, P.L., Namias, S., Sánchez, G.L., Barrientos, G.C., Valdés, J.L., Paula-Lima, A.C., Hidalgo, C., Adasme, T. Calcium Release Mediated by Redox-Sensitive RyR2 Channels Has a Central Role in Hippocampal Structural Plasticity and Spatial Memory. Antioxid Redox Signal, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoso, P.; Finkelstein, J.P.; Montecinos, L.; Said, M.; Sánchez, G.; Vittone, L.; Bull, R. Stimulation of NOX2 in isolated hearts reversibly sensitizes RyR2 channels to activation by cytoplasmic calcium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014, 68, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donoso, P.; Aracena, P.; Hidalgo, C. Sulphydryl oxidation overrides Mg2+-inhibition of calcium-induced calcium release in skeletal muscle triads. Biophys J. 2000, 79, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Cavieres, A.; More, J.; Vicente, J.M.; Adasme, T.; Hidalgo, J.; Valdés, J.L.; Humeres, A.; Valdés-Undurraga, I.; Sánchez, G.; Hidalgo, C.; Barrientos, G. Triclosan Impairs Hippocampal Synaptic Plasticity and Spatial Memory in Male Rats. Front Mol Neurosci. 2018, 26, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, B.; Adachi, N.; Arai, T. The effect of hypothermia on H2O2 production during ischemia and reperfusion: a microdialysis study in the gerbil hippocampus. Neurosci Lett. 1997, 222, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McManus, T.; Sadgrove, M.; Pringle, A.K.; Chad, J.E.; Sundstrom, L.E. Intraischaemic hypothermia reduces free radical production and protects against ischaemic insults in cultured hippocampal slices. J Neurochem. 2004, 91, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, E.H.; Moskowitz, M.A.; Jacobs, T.P. Exciting, radical, suicidal: how brain cells die after stroke. Stroke. 2005, 36, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomgren, K.; Hagberg, H. Free radicals, mitochondria, and hypoxia-ischemia in the developing brain. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006, 40, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pessah, I.N.; Feng, W. Functional role of hyperreactive sulfhydryl moieties within the ryanodine receptor complex. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2000, 2, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, C.; Aracena, P.; Sánchez, G.; Donoso, P. Redox regulation of calcium release in skeletal and cardiac muscle. Biol Res. 2002, 35, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega-Vásquez, I. , Lobos, P., Toledo, J., Adasme, T., Paula-Lima, A., Hidalgo, C. Hippocampal dendritic spines express the RyR3 but not the RyR2 ryanodine receptor isoform. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2022, 633, 633,96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuichi, T.; Furutama, D.; Hakamata, Y. , Nakai, J.; Takeshima, H.; Mikoshiba, K. Multiple types of ryanodine receptor/Ca2+ release channels are differentially expressed in rabbit brain. J Neurosci. 1994, 14, 4794–4805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindoli, A.; Fukuto, J.M.; Forman, H.J. Thiol chemistry in peroxidase catalysis and redox signaling. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008, 10, 1549–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aracena, P.; Sánchez, G.; Donoso, P.; Hamilton, S.L.; Hidalgo, C. S-glutathionylation decreases Mg2+ inhibition and S-nitrosylation enhances Ca2+ activation of RyR1 channels. J Biol Chem. 2003, 278, 42927–42935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemmerling, U.; Muñoz, P.; Müller, M.; Sánchez, G.; Aylwin, M.L.; Klann, E.; Carrasco, M.A.; Hidalgo, C. Calcium release by ryanodine receptors mediates hydrogen peroxide-induced activation of ERK and CREB phosphorylation in N2a cells and hippocampal neurons. Cell Calcium. 2007, 41, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- More, J.; Galusso, N.; Veloso, P.; Montecinos, L.; Finkelstein, J.P.; Sánchez, G.; Bull, R.; Valdés, J.L.; Hidalgo, C.; Paula-Lima, A. N-Acetylcysteine Prevents the Spatial Memory Deficits and the Redox-Dependent RyR2 Decrease Displayed by an Alzheimer's Disease Rat Model. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark. R.E., Broadbent, N.J., and Squire, L.R.. Hippocampus and remote spatial memory in rats. Hippocampus 2005, 15, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).