Submitted:

13 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Sources and Types of Human Pharmaceutical Active Compounds in the Aquatic Environment

1.2. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Defense at Fish

1.2.1. Impacts of Oxidative Damage

1.2.2. Antioxidant Defenses as Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress

2. Methodology

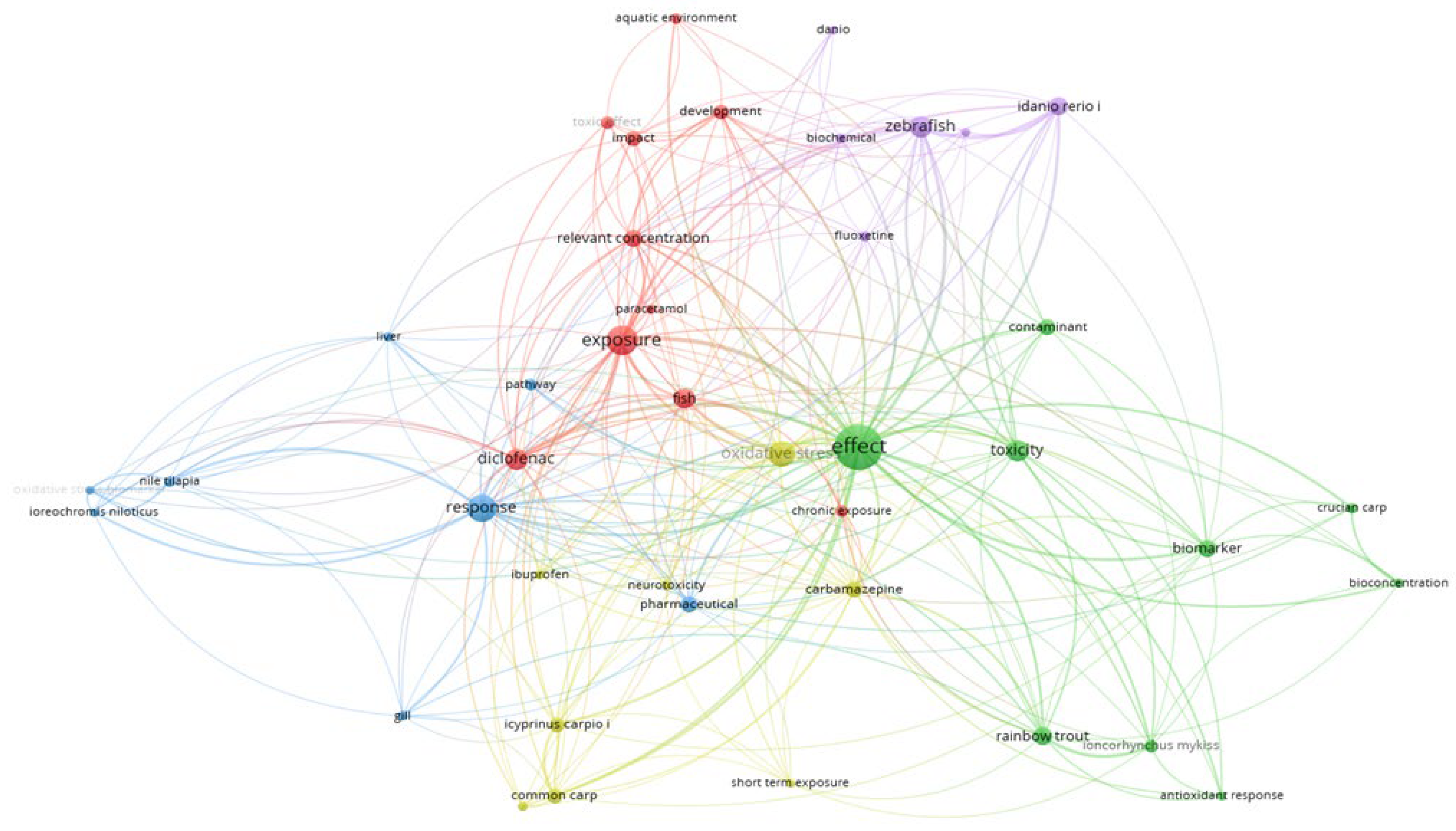

2.1. Data sources and Bibliometric Tools

3. Discussions

3.1. The Influence of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) on Oxidative Stress in Fish

| Category |

Pharm. prod. |

Species | Concentration | Effects on the physiological level | Ref. |

| NSAIDs | DCF |

Danio rerio (embryos and larvae) |

0; 0.5; 5; 50 and 500 μg/L for 96 hours | (+) CAT activity and GPx at 500 μg/L; (-) GSTs in all concentrations. |

[79] |

| Hoplias malabaricus | 0; 0.2; 2.0; 20 μg/kg, after intraperitoneal inoculation with 12 doses | (+) SOD, GPx, LPO, and GSH in the liver; (-) GST; No modifications of CAT activity. |

[81] | ||

| Oreochromis niloticus | 0; 250; 320; 480 μg/L for 28 days | (+) LPO; (+) GRed, GPx and GSH; (-) SOD and CAT. |

[82] | ||

| Rhamdia quelen | 0; 0.2; 2 and 20 μg/L for 21 days | (-) SOD; (+) GSH; (+) GST in all concentrations- in the liver: (-) LPO at 2 and 20 μg/L; (-) CAT at 2 μg/L; No modification of GPx activity. |

[84] | ||

| Rhamdia quelen | 0; 0.2; 2 and 20 μg/L for 96 hours | (+) SOD in the kidney at all concentrations; No alteration of CAT and GPx; (-) LPO; significant decrease of DNA damage in the kidney at 20 μg/L. |

[85] | ||

| IBF | Rhamdia quelen | 0.1, 1, and 10 μg/L for 14 days | (+) GST in all groups; (+) GPx and GSH activity at concentrations of 10 μg/L in the kidney; No modifications of SOD, CAT, and LPO activities. |

[94] | |

| Tinca tinca | 0.02 -60 μg/L for 35 days | (-) GST in 60 μg/L; (-) GST No modification of CAT activity and LPO |

[93] | ||

| Oncorhynchus mykiss | 2 and 200 μg/kg feed | In gills (-) GPX at all concentrations; In liver (+) LPO and GRed at 200 μg/kg feed; No changes in the activity of antioxidant enzymes in the kidney. |

[91] | ||

| ASA | Labeo rohita | 1, 10, 100 μg/L for 7, 14, 21 and 28 days | (-) SOD, CAT, GPx, GRed, GSH in liver at al conc.; (+) GST and LPO. | [104] | |

| Mugilogobius abei | 0.5, 5, and 50 μg/ L for 24, 72, 168 hours | (+) SOD, CAT, GPx, and GST activity; (-) GSH after 24 and 72 h; (+) GSH 168 hours; (+) MDA; (-) MDA after 168 hours |

[105] | ||

| APAP | Rhamdia quelen | 0, 0.25, 2.5 µg/ L, for 21 days | (+) SOD activity at a concentration of 2.5 µg/L; (-) GST at all concentrations; No modification of GPx, GSH, and LPO |

[109] | |

| Danio rerio embryos | 150, 300, 450, 600, 750, 900, 1050, and 1200 μg/L | (+) MDA and CAT; (+) SOD from conc. of 300 -1200 μg/L | [110] | ||

| Anguilla anguilla | 5, 25, 125, 625, and 3125 μg/L |

In liver: (+) GST at 625 and 3125 mg/L; LPO remained unaltered In gills: (-) GST; (+) LPO |

[111] | ||

| Antibiotics | OTC |

Danio rerio |

0, 0.1, 10, and 10,000 mg/L for 2 months | (-) GST and CAT | [117] |

| SMZ | Oreochromis niloticus | 0, 1, 10 and 100 μg/L SMZ for 7 and 30 days | In liver (+) SOD, CAT, GPx, GSH at 1 and 10 μg/L CAT and GSH, (-) LPO; At 100 μg/L SMZ (-) SOD and GSH; (+) LPO at both 7 and 30 days. |

[119] | |

| CIP | Danio rerio | 0,7 µg/L, 100, 650, 1100 and 3000 µg/L for 28 days |

(+) GST at 0,7 and 100 µg/L; (-) GST at 650, 1100, and 3 000 μg/L; (-) GRed at conc. of 1100 and 3000 µg/L; (-) GPX, at all tested concentrations, except for the 100 µg/L; (-) LPO at 100 μg/L |

[120] | |

| Antiepileptics | CBZ | Cyprinus carpio | 0, 1, 5, 50, or 100 µg/L of CBZ for 28 days | (+) CAT and GRed at 5 and 50 µg/ L) at 100 µg/L (-) GRed.; (-) SOD. | [126] |

| CBZ | Cyprinus carpio | 2000 µg/L exposure from 12-96 hours | (-) LPO in the brain after 24,48, 72 hours; (-) SOD in liver, gills and brain; (-) CAT; (+) GPx in liver, after 48 hours; (-)GPx at 96 hours; (-) GPx in the brain and gills. |

[128] | |

| Antidepressants | FLX | Danio rerio | 5, 16, 40 ng/L for 96 hours | (+) SOD, CAT, GPx in the liver, intestine, brain, and gills. (+) MDA in the brain and tissues after 96 hours at conc. of 5-40 ng/L |

[131] |

| FLX | Danio rerio | 0.0015, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5 and 0.8μM for 80 hours | (+) CAT (0.0015 and 0.5μM) (-) SOD (0.0015 and 0.5μM) |

[138] | |

| Pharm. mixtures | DCF+IBF | Oncorhynchus mykiss | DCF - 2 and 200 μg/kg); IBF- 2 and 200 μg/kg. Combination of DCF and IBF – (2 μg/kg DCF+ 2 μg/kg; 200 μg/kg IBF). |

In gills: (-) GPx activity at IBP 2 and 200 μg kg/kg and the combination of DCF and IBF; In liver: (+) LPO in DCF and IBP, and DCF conc. of 200 μg/kg (+) GR activity at IBF 200 μg/kg; In the posterior kidney: (+) CAT at DCF 200 μg/kg. |

[91] |

| DCF+ APAP | Cyprinus carpio | 50 μg of each/L, 1:1) | (+) SOD in the brain; (-) SOD in liver and gills; (+) CAT in the brain and gills; (+) GPx in brain and liver; (+) LPO in liver and gills. | [146] | |

| CBZ, irbesartan, APAP, NPX, DCF | Oncorhynchus mykiss | concentrations of 1x, 10x, and 100x the median levels found in the Meuse River, Belgium, over 42 days | No change of GST; (-) GSH after 24 hours; (-) GPx and CAT |

[147] |

3.2. The Influence of Antibiotics on Fish Oxidative Stress

3.3. The Influence of Antiepileptics Drugs on Fish Oxidative Stress

3.4. The Influence of Antidepressant Drugs on Fish Oxidative Stress

3.5. The Influence of Pharmaceutical Mixture on Fish Oxidative Stress

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cunningham, V.L.; Constable, D.J.C.; Hannah, R.E. Environmental Risk Assessment of Paroxetine. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 3351–3359. [CrossRef]

- Fent, K.; Weston, A.; Caminada, D. Ecotoxicology of human pharmaceuticals. Aquat. Toxicol. 2006, 76, 122–159. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, P.; Thomas, K. The occurrence of selected pharmaceuticals in wastewater effluent and surface waters of the lower Tyne catchment. Sci. Total. Environ. 2006, 356, 143–153. [CrossRef]

- IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science. https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports-and-publications/reports/the-global-use-of-medicines-2023, accessed at 29 May 2024.

- Daughton, C.G. Pharmaceuticals in the environment: sources and their management. Wilson Wilsons Compr. Anal. Chem., 2007, 50, 1-58.

- Chonova, T.; Keck, F.; Labanowski, J.; Montuelle, B.; Rimet, F.; Bouchez, A. Separate treatment of hospital and urban wastewaters: A real scale comparison of effluents and their effect on microbial communities. Sci. Total. Environ. 2016, 542, 965–975. [CrossRef]

- Wollenberger, L.; Halling-Sørensen, B.; Kusk, K. Acute and chronic toxicity of veterinary antibiotics to Daphnia magna. Chemosphere 2000, 40, 723–730. [CrossRef]

- Brausch, J.M.; Connors, K.A.; Brooks, B.W.; Rand, G.M. Human Pharmaceuticals in the Aquatic Environment: A Review of Recent Toxicological Studies and Considerations for Toxicity Testing. In Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology Volume 218; Whitacre, D.M., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2012; Volume 218, pp. 1–99, ISBN 978-1-4614-3137-4.

- Koubová, A.; Van Nguyen, T.; Grabicová, K.; Burkina, V.; Aydin, F.G.; Grabic, R.; Nováková, P.; Švecová, H.; Lepič, P.; Fedorova, G.; et al. Metabolome adaptation and oxidative stress response of common carp (Cyprinus carpio) to altered water pollution levels. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 303, 119117. [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.H.M.L.M.; Araújo, A.N.; Fachini, A.; Pena, A.; Delerue-Matos, C.; Montenegro, M.C.B.S.M. Ecotoxicological aspects related to the presence of pharmaceuticals in the aquatic environment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 175, 45–95. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.; Senac, T. Human pharmaceutical products in the environment–the “problem” in perspective. Chemosphere, 2014, 115, 95-99.

- Burkina, V.; Zlabek, V.; Zamaratskaia, G. Effects of pharmaceuticals present in aquatic environment on Phase I metabolism in fish. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2015, 40, 430–444. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.; Joshi, M.; Bhatnagar, A.; Chaurasia, A.K.; Nigam, S. Pharmaceutical residues: One of the significant problems in achieving ‘clean water for all’ and its solution. Environ. Res. 2022, 215, 114219. [CrossRef]

- García-Morales, R.; García-García, A.; Orona-Navar, C.; Osma, J.F.; Nigam, K.; Ornelas-Soto, N. Biotransformation of emerging pollutants in groundwater by laccase from P. sanguineus CS43 immobilized onto titania nanoparticles. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 710–717. [CrossRef]

- Kondor, A.C.; Molnár, É.; Vancsik, A.; Filep, T.; Szeberényi, J.; Szabó, L.; Maász, G.; Pirger, Z.; Weiperth, A.; Ferincz, Á.; et al. Occurrence and health risk assessment of pharmaceutically active compounds in riverbank filtrated drinking water. J. Water Process. Eng. 2021, 41. [CrossRef]

- Forsberg, M. Occurrence of organic micropollutants and hormones in Swedish surface water. Uppsala University, Disciplinary Domain of Science and Technology, Earth Sciences, Department of Earth Sciences, 2022, 47p.

- Grabicova, K.; Grabic, R.; Fedorova, G.; Fick, J.; Cerveny, D.; Kolarova, J.; Turek, J.; Zlabek, V.; Randak, T. Bioaccumulation of psychoactive pharmaceuticals in fish in an effluent dominated stream. Water Res. 2017, 124, 654–662. [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, J.; Winter, M.J.; Tyler, C.R. Pharmaceuticals in the aquatic environment: A critical review of the evidence for health effects in fish. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2010, 40, 287–304. [CrossRef]

- Nakano, T.; Hayashi, S.; Nagamine, N. Effect of excessive doses of oxytetracycline on stress-related biomarker expression in coho salmon. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 25, 7121–7128. [CrossRef]

- Directive 2013/39/eu https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/RO/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32013L0039&from=IT [Last accessed on 1 June 2024].

- Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2018/840 of 5 June 2018 establishing a watch list of substances for Union-wide monitoring in the field of water policy pursuant to Directive 2008/105/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council and repealing Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2015/495 (notified under document C(2018) 3362). Available from: https://eurlex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32018D0840. [Last accessed on 1 June 2024].

- European Commission, 2020. EUR-Lex – Regulation (EU) 2020/741 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 May 2020 on minimum requirements for water reuse. Off. J. Eur. Union L177, 32–54. [Last accessed on 1 June 2024].

- Eu, 2022 https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32022D1307, [Last accessed on 1 June 2024].

- Kümmerer, K. Antibiotics in the aquatic environment–a review–part I. Chemosphere, 2009, 75(4), 417-434.

- Mukhtar, A.; Manzoor, M.; Gul, I.; Zafar, R.; Jamil, H.I.; Niazi, A.K.; Ali, M.A.; Park, T.J.; Arshad, M. Phytotoxicity of different antibiotics to rice and stress alleviation upon application of organic amendments. Chemosphere 2020, 258, 127353. [CrossRef]

- Sosa-Hernández, J.E.; Rodas-Zuluaga, L.I.; López-Pacheco, I.Y.; Melchor-Martínez, E.M.; Aghalari, Z.; Limón, D.S.; Hafiz M.N.; Parra-Saldívar, R. Sources of antibiotics pollutants in the aquatic environment under SARS-CoV-2 pandemic situation. Case stud. Chem. Environ. Eng., 2021, 4, 100127.

- Chițescu, C.L.; Kaklamanos, G.; Nicolau, A.I.; Stolker, A.A.M.L. High sensitive multi-residue analysis of pharmaceuticals and antifungals in surface water using U-HPLC-Q-Exactive Orbitrap HRMS. Application to the Danube River basin on the Romanian territory. Sci. Total Environ., 2015, 532, 501-511.

- Das, S.A.; Karmakar, S.; Chhaba, B.; Rout, S.K. Ibuprofen: its toxic effect on aquatic organisms. J. Exp. Zoology India, 2019, 22(2), 1125-1131.

- Patel, M.; Kumar, R.; Kishor, K.; Mlsna, T.; Pittman Jr., C.U.; Mohan, D. Pharmaceuticals of emerging concern in aquatic systems: chemistry, occurrence, effects, and removal methods. Chem. Rev., 2019, 119(6), 3510-3673.

- Placova, K.; Halfar, J.; Brozova, K.; Heviankova, S. Issues of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs in Aquatic Environments: A Review Study. The 4th International Conference on Advances in Environmental Engineering. p. 13.

- Schultz, M.M.; Furlong, E.T. Trace Analysis of Antidepressant Pharmaceuticals and Their Select Degradates in Aquatic Matrixes by LC/ESI/MS/MS. Anal. Chem. 2008, 80, 1756–1762. [CrossRef]

- Correia, D.; Domingues, I.; Faria, M.; Oliveira, M. Effects of fluoxetine on fish: What do we know and where should we focus our efforts in the future Sci. Total Environ, 2023, 857, 159486.

- Bahlmann, A.; Weller, M.G.; Panne, U.; Schneider, R.J. Monitoring carbamazepine in surface and wastewaters by an immunoassay based on a monoclonal antibody. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2009, 395, 1809–1820. [CrossRef]

- Baali, H.; Cosio, C; Effects of carbamazepine in aquatic biota. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts, 2022, 24(2), 209-220.

- Cleuvers, M. Initial risk assessment for three β-blockers found in the aquatic environment. Chemosphere 2005, 59, 199–205. [CrossRef]

- Sumpter, J.P.; Runnalls, T.J.; Donnachie, R.L.; Owen, S.F. A comprehensive aquatic risk assessment of the beta-blocker propranolol, based on the results of over 600 research papers. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 793, 148617. [CrossRef]

- Young, R.B.; Borch, T. Sources, Presence, Analysis, and Fate of Steroid Sex Hormones in Freshwater Ecosystems–A review. Reprod., 2009, 1(3).

- Laurenson, J.P.; Bloom, R.A.; Page, S.; Sadrieh, N. Ethinyl Estradiol and Other Human Pharmaceutical Estrogens in the Aquatic Environment: A Review of Recent Risk Assessment Data. AAPS J. 2014, 16, 299–310. [CrossRef]

- Berninger, J.P.; Du, B.; Connors, K.A.; Eytcheson, S.A.; Kolkmeier, M.A.; Prosser, K.N.; Theodore W.’ Valenti Jr. C.; Chambliss C.K.; Brooks B.W. Effects of the antihistamine diphenhydramine on selected aquatic organisms. Environ. Toxicol. Chem., 2011, 30(9), 2065-2072.

- A Arnot, J.; Gobas, F.A. A review of bioconcentration factor (BCF) and bioaccumulation factor (BAF) assessments for organic chemicals in aquatic organisms. Environ. Rev. 2006, 14, 257–297. [CrossRef]

- Eapen, J.V.; Thomas, S.; Antony, S.; George, P.; Antony, J. A review of the effects of pharmaceutical pollutants on humans and aquatic ecosystem. 2024, 2, 484–507. [CrossRef]

- Pizzino, G.; Irrera, N.; Cucinotta, M.; Pallio, G.; Mannino, F.; Arcoraci, V.; Squadrito, F.; Altavilla, D.; Bitto, A. Oxidative Stress: Harms and Benefits for Human Health. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 8416763. [CrossRef]

- Sies, H. Oxidative stress: damage to intact cells and organs. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. B, Biological Sciences, 1985, 311(1152), 617-631.

- Rock C.L; Jacob R.A; Bowen P.E; Update on biological characteristics of the antioxidant micronutrients - Vitamin C, Vitamin E and the carotenoids. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1996, 96, 693– 702.

- Jones, D.P. Redefining Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2006, 8, 1865–1879. [CrossRef]

- Bolaric, S; Vokurka, A; Batelja Lodeta, K; Bencic, Ð. Genotyping of Croatian Olive Germplasm with Consensus SSR Markers. Horticulturae. 2024, 10, 417. [CrossRef]

- Hoseinifar, S.H.; Yousefi, S.; Van Doan, H.; Ashouri, G.; Gioacchini, G.; Maradonna, F.; Carnevali, O. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Defense in Fish: The Implications of Probiotic, Prebiotic, and Synbiotics. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2020, 29, 198–217. [CrossRef]

- Fridovich, I. Mitochondria: are they the seat of senescence?. Aging Cell 2003, 3, 13–16. [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Boiti, A.; Vallone, D.; Foulkes, N.S. Reactive Oxygen Species Signaling and Oxidative Stress: Transcriptional Regulation and Evolution. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 312. [CrossRef]

- Paiva, C.N.; Bozza, M.T. Are reactive oxygen species always detrimental to pathogens? Antioxidants & redox signaling, 2014, 20(6), 1000-1037.

- Ghosh, N.; Das, A.; Chaffee, S.; Roy, S.; Sen, C. K. Reactive oxygen species, oxidative damage and cell death. In Immunity and inflammation in health and disease, 2018, (pp. 45-55). Academic Press.

- Ji, L.L.; Yeo, D. Oxidative stress: an evolving definition. Fac. Rev. 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Juan, C.A.; de la Lastra, J.M.P.; Plou, F.J.; Pérez-Lebeña, E. The Chemistry of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Revisited: Outlining Their Role in Biological Macromolecules (DNA, Lipids and Proteins) and Induced Pathologies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4642. [CrossRef]

- Bresciani, G.; da Cruz, I.B.M.; González-Gallego, J. Manganese superoxide dismutase and oxidative stress modulation. Adv. Clin. Chem, 2015, 68, 87-130.

- Ayala, A.; Muñoz, M.F.; Argüelles, S. Lipid peroxidation: production, metabolism, and signaling mechanisms of malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2014, 2014, 360438. [CrossRef]

- Kong, Q.; Lin, C.-L.G. Oxidative damage to RNA: mechanisms, consequences, and diseases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2010, 67, 1817–1829. [CrossRef]

- Martins, S.G.; Zilhão, R.; Thorsteinsdóttir, S.; Carlos, A.R. Linking Oxidative Stress and DNA Damage to Changes in the Expression of Extracellular Matrix Components. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 673002. [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Garg, V.K.; Singh, A.K.; Tinku, T. Role of free radicals and certain antioxidants in the management of huntington’s disease: a review. J. Anal. Pharm. Res. 2018, 7, 1. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, B.; Reddy, P. B. Impacts of human pharmaceuticals on fish health. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res, 2021, 12(5185), 5185-94.

- Rodriguez, Y.E.; Laitano, M.V.; Pereira, N.A.; López-Zavala, A.A.; Haran, N.S.; Fernández-Gimenez, A.V. Exogenous enzymes in aquaculture: Alginate and alginate-bentonite microcapsules for the intestinal delivery of shrimp proteases to Nile tilapia. Aquaculture 2018, 490, 35–43. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, V.; Shah, C.; Mokashe, N.; Chavan, R.; Yadav, H.; Prajapati, J. Probiotics as Potential Antioxidants: A Systematic Review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 3615–3626. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Álvarez, R.M.; Morales, A.E.; Sanz, A. Antioxidant Defenses in Fish: Biotic and Abiotic Factors. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2005, 15, 75–88. [CrossRef]

- Olufunmilayo, E.O.; Gerke-Duncan, M.B.; Holsinger, R.M.D. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidants in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 517. [CrossRef]

- SanJuan-Reyes, N.; Gómez-Oliván, L.M.; Galar-Martínez, M.; Vieyra-Reyes, P.; García-Medina, S.; Islas-Flores, H.; Neri-Cruz, N. Effluent from an NSAID-Manufacturing Plant in Mexico Induces Oxidative Stress on Cyprinus carpio. Water, Air, Soil Pollut. 2013, 224, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.; Correia, A.; Antunes, S.; Gonçalves, F.; Nunes, B. Effect of acetaminophen exposure in Oncorhynchus mykiss gills and liver: Detoxification mechanisms, oxidative defence system and peroxidative damage. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2014, 37, 1221–1228. [CrossRef]

- Devi, G.; Harikrishnan, R.; Paray, B.A.; Al-Sadoon, M.K.; Hoseinifar, S.H.; Balasundaram, C. Effect of symbiotic supplemented diet on innate-adaptive immune response, cytokine gene regulation and antioxidant property in Labeo rohita against Aeromonas hydrophila. Fish Shellfish. Immunol. 2019, 89, 687–700. [CrossRef]

- Sherratt, P.J.; Hayes, J.D. Glutathione S-transferases. Enzyme systems that metabolize drugs and other xenobiotics, 2019, 319-352.

- Waggiallah, H.; Alzohairy, M. The effect of oxidative stress on human red cells glutathione peroxidase, glutathione reductase level, and prevalence of anemia among diabetics. North Am. J. Med Sci. 2011, 3, 344–347. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, K.; Khare, A.; Dange, S. The Applicability of Oxidative Stress Biomarkers in Assessing Chromium Induced Toxicity in the FishLabeo rohita. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- wiacka, K.; Maculewicz, J.; Kowalska, D.; Caban, M.; Smolarz, K.; Świeżak, J. Presence of pharmaceuticals and their metabolites in wild-living aquatic organisms–current state of knowledge J. Hazard. Mater., 2022, 424, 127350.

- Blasco, J.; Trombini, C. Ibuprofen and diclofenac in the marine environment - a critical review of their occurrence and potential risk for invertebrate species. Water Emerg. Contam. Nanoplastics 2023, 2, 14. [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, Y.; Heckmann, L.-H.; Callaghan, A.; Sibly, R.M. Reproduction recovery of the crustacean Daphnia magna after chronic exposure to ibuprofen. Ecotoxicology 2008, 17, 246–251. [CrossRef]

- Świacka, K.; Michnowska, A.; Maculewicz, J.; Caban, M.; Smolarz, K. Toxic effects of NSAIDs in non-target species: A review from the perspective of the aquatic environment. 2020, 273, 115891. [CrossRef]

- Acuña, V.; Ginebreda, A.; Mor, J.; Petrovic, M.; Sabater, S.; Sumpter, J.; Barceló, D. Balancing the health benefits and environmental risks of pharmaceuticals: Diclofenac as an example. Environ. Int. 2015, 85, 327–333. [CrossRef]

- Chitescu, C.L.; Kaklamanos, G.; Nicolau, A.I.; Stolker, A.A. High sensitive multiresidue analysis of pharmaceuticals and antifungals in surface water using U-HPLC-Q-Exactive Orbitrap HRMS. Application to the Danube river basin on the Romanian territory. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 532, 501–511. [CrossRef]

- Hallare, A.V.; Köhler, H.-R.; Triebskorn, R. Developmental toxicity and stress protein responses in zebrafish embryos after exposure to diclofenac and its solvent, DMSO. Chemosphere 2004, 56, 659–666. [CrossRef]

- Oviedo-Gómez, D.G.C.; Galar-Martínez, M.; García-Medina, S.; Razo-Estrada, C.; Gómez-Oliván, L.M. Diclofenac-enriched artificial sediment induces oxidative stress in Hyalella azteca. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2010, 29, 39–43. [CrossRef]

- Grillo, M.P.; Hua, F.; Knutson, G.C.; Ware, A.J.; Li, C.Mechanistic studies on the bioactivation of diclofenac: Identification of diclofenac-S-acyl-glutathione in vitro in incubations with rat and human hepatocytes. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2003, 16, 1410–1417.

- Bio, S.; Nunes, B. Acute effects of diclofenac on zebrafish: Indications of oxidative effects and damages at environmentally realistic levels of exposure. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2020, 78, 103394. [CrossRef]

- Diniz, M.S.; de Matos, A.P.A.; Lourenço, J.; Castro, L.; Peres, I.; Mendonça, E.; Picado, A. Liver Alterations in Two Freshwater Fish Species (Carassius auratusandDanio rerio) Following Exposure to Different TiO2Nanoparticle Concentrations. Microsc. Microanal. 2013, 19, 1131–1140. [CrossRef]

- Guiloski I.C.; Ribas J.L.C.; da Pereira L.S.; Neves A.P.P.; Silva de Assis H.C. Effects of Trophic Exposure to Dexamethasone and Diclofenac in Freshwater Fish. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2015, 114, 204–211.

- Eze, C.C.; Nwamba, H.O.; Omeje, F.U.; Anukwu, J.U.; Okpe, M.N.; Nwani, C.D. Effects of Diclofenac on the Oxidative Stress Parameters of Freshwater Fish Oreochromis niloticus. J. Appl. Life Sci. Int. 2021, 44–51. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, L.K.; Bergey, E.A.; Lyu, J.; Park, J.; Choi, S.; Lee, H.; Depuydt, S.; Oh, Y.-T.; Lee, S.-M.; Han, T. The use of diatoms in ecotoxicology and bioassessment: Insights, advances and challenges. Water Res. 2017, 118, 39–58. [CrossRef]

- Guiloski, I.C.; Piancini, L.D.S.; Dagostim, A.C.; Calado, S.L.d.M.; Fávaro, L.F.; Boschen, S.L.; Cestari, M.M.; da Cunha, C.; de Assis, H.C.S. Effects of environmentally relevant concentrations of the anti-inflammatory drug diclofenac in freshwater fish Rhamdia quelen. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2017, 139, 291–300. [CrossRef]

- Ghelfi, A.; Ribas, J.L.C.; Guiloski, I.C.; Bettim, F.L.; Piancini, L.D.S.; Cestari, M.M.; Pereira, A.J.; Sassaki, G.L.; de Assis, H.C.S. Evaluation of Biochemical, Genetic and Hematological Biomarkers in a Commercial Catfish Rhamdia quelen Exposed to Diclofenac. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2015, 96, 49–54. [CrossRef]

- Petersen, A.; Zetterberg, M.; Sjöstrand, J.; Pålsson, A.; Karlsson, J.-O. Potential Protective Effects of NSAIDs/ASA in Oxidatively Stressed Human Lens Epithelial Cells and Intact Mouse Lenses in Culture. Ophthalmic Res. 2005, 37, 318–327. [CrossRef]

- Feito, R., Valcárcel, Y., & Catalá, M. Biomarker assessment of toxicity with miniaturized bioassays: diclofenac as a case study. Ecotoxicology, 2012, 21, 289-296.

- Praskova, E.; Plhalova, L.; Chromcova, L.; Stepanova, S.; Bedanova, I.; Blahova, J.; Hostovsky, M.; Skoric, M.; Maršálek, P.; Voslarova, E.; et al. Effects of Subchronic Exposure of Diclofenac on Growth, Histopathological Changes, and Oxidative Stress in Zebrafish (Danio rerio). Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Cahill, J.D.; Furlong E.T.; Burkhardt, M.R.; Kolpin, D.; Anderson, L.G.; Determination of pharmaceutical compounds in surface- and ground-water samples by solid-phase extraction and high-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr., 2004, 1041(1-2), 171–180.

- Pereira, C.D.S.; Maranho, L.A.; Cortez, F.S.; Pusceddu, F.H.; Santos, A.R.; Ribeiro, D.A.; Cesar, A.; Guimarães, L.L. Occurrence of pharmaceuticals and cocaine in a Brazilian coastal zone. Sci. Total. Environ. 2016, 548-549, 148–154. [CrossRef]

- Hodkovicova, N.; Hollerova, A.; Blahova, J.; Mikula, P.; Crhanova, M.; Karasova, D.; Franc, S. Pavlokova, Mares, Postulkova, E.; Tichy, F.; Marsalek, P.; Lanikova, J.; Faldyna, M.; Svobodova, Z. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs caused an outbreak of inflammation and oxidative stress with changes in the gut microbiota in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Sci. Total Environ., 2022, 849, 157921.

- Ragugnetti, M.; Adams, M.L.; Guimarães, A.T.B.; Sponchiado, G.; de Vasconcelos, E.C.; de Oliveira, C.M.R. Ibuprofen Genotoxicity in Aquatic Environment: An Experimental Model Using Oreochromis niloticus. Water, Air, Soil Pollut. 2010, 218, 361–364. [CrossRef]

- Stancova, V.; Plhalova, L.; Blahova, J.; Zivna, D.; Bartoskova, M.; Siroka, Z.; Marsalek, P.; Svobodova, Z. cc. Veterinární medicína, 2017, 62(2), 90-97.

- Mathias, F.T.; Fockink, D.H.; Disner, G.R.; Prodocimo, V.; Ribas, J.L.C.; Ramos, L.P.; Cestari, M.M.; de Assis, H.C.S. Effects of low concentrations of ibuprofen on freshwater fish Rhamdia quelen. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2018, 59, 105–113. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Liu, X.; Pan, L.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, L.; Mou, X.; Zhou, H.; Liu, J.; Wang, X. Evaluation of ibuprofen contamination in local urban rivers and its effects on immune parameters of juvenile grass carp. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 47, 1405–1413. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Aceves, L.; Pérez-Alvarez, I.; Gómez-Oliván, L.M.; Islas-Flores, H.; Barceló, D. Long-term exposure to environmentally relevant concentrations of ibuprofen and aluminum alters oxidative stress status on Danio rerio. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C: Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2021, 248, 109071. [CrossRef]

- Wadhah Hassan, A.E. Occurrence of paracetamol in aquatic environments and transformation by microorgan-isms: a review. Chron. Pharm. Sci., 2017, 1, 341-355.

- Satayeva, A.; Kerim, T.; Kamal, A.; Issayev, J.; Inglezakis, V.; Kim, J.; Arkhangelsky, E. Determination of aspirin in municipal wastewaters of Nur-Sultan City, Kazakhstan. IOP Conf. Series: Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1123, 012067. [CrossRef]

- Wille, K.; Noppe, H.; Verheyden, K.; Bussche, J.V.; De Wulf, E.; Van Caeter, P.; Janssen, C.R.; De Brabander, H.F.; Vanhaecke, L. Validation and application of an LC-MS/MS method for the simultaneous quantification of 13 pharmaceuticals in seawater. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010, 397, 1797–1808. [CrossRef]

- Paíga, P.; Santos, L.H.; Ramos, S.; Jorge, S.; Silva, J.G.; Delerue-Matos, C. Presence of pharmaceuticals in the Lis river (Portugal): Sources, fate and seasonal variation. Sci. Total. Environ. 2016, 573, 164–177. [CrossRef]

- Ilie, M.; Deák, G.; Marinescu, F.; Ghita, G.; Tociu, C.; Matei, M.; Covaliu, C.I.; Raischi, M.; Yusof, S.Y. Detection of Emerging Pollutants Oxytetracycline and Paracetamol and the Potential Aquatic Ecological Risk Associated with their Presence in Surface Waters of the Arges-Vedea, Buzau-Ialomita, Dobrogea-Litoral River Basins in Romania. IOP Conf. Series: Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 616, 012016. [CrossRef]

- Koagouw, W.; Arifin, Z.; Olivier, G.W.; Ciocan, C. High concentrations of paracetamol in effluent dominated waters of Jakarta Bay, Indonesia. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 169, 112558. [CrossRef]

- Al-Kaf, G.; Naji, M.K.; Abdullah Q.Y.M.A.; Wadhah Hassan, A.E. Occurrence of paracetamol in aquatic environments and transformation by microorganisms: a review. Chron. Pharm. Sci, 2007, 1, 341-355.

- Gayen, T.; Tripathi, A.; Kumari, U.; Mittal, S.; Mittal, A.K. Ecotoxicological impacts of environmentally relevant concentrations of aspirin in the liver of Labeo rohita: Biochemical and histopathological investigation. Chemosphere 2023, 333, 138921. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Wang, C., Bao, S., & Nie, X. Responses of the Nrf2/Keap1 signaling pathway in Mugilogobius abei (M. abei) exposed to environmentally relevant concentration aspirin. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int, 2020, 27, 15663-15673.

- Erhunmwunse, N.O.; Tongo, I.; Ezemonye, L.I. Acute effects of acetaminophen on the developmental, swimming performance and cardiovascular activities of the African catfish embryos/larvae (Clarias gariepinus). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 208, 111482. [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.; Alsop, D.; Wilson, J.Y. The effects of chronic acetaminophen exposure on the kidney, gill and liver in rainbow trout ( Oncorhynchus mykiss ). Aquat. Toxicol. 2018, 198, 20–29. [CrossRef]

- Yen, F.-L.; Wu, T.-H.; Lin, L.-T.; Lin, C.-C. Hepatoprotective and antioxidant effects of Cuscuta chinensis against acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006, 111, 123–128. [CrossRef]

- Guiloski, I.C.; Ribas, J.L.C.; Piancini, L.D.S.; Dagostim, A.C.; Cirio, S.M.; Fávaro, L.F.; Boschen, S.L.; Cestari, M.M.; da Cunha, C.; de Assis, H.C.S. Paracetamol causes endocrine disruption and hepatotoxicity in male fish Rhamdia quelen after subchronic exposure. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2017, 53, 111–120. [CrossRef]

- Rosas-Ramírez, J.R.; Orozco-Hernández, J.M.; Elizalde-Velázquez, G.A.; Raldúa, D.; Islas-Flores, H.; Gómez-Oliván, L.M. Teratogenic effects induced by paracetamol, ciprofloxacin, and their mixture on Danio rerio embryos: Oxidative stress implications. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 806, 150541. [CrossRef]

- Nunes, B.; Verde, M.F.; Soares, A.M.V.M. Biochemical effects of the pharmaceutical drug paracetamol on Anguilla anguilla. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 11574–11584. [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Guo, P.; Peng, X.; Wen, K. Effect of erythromycin exposure on the growth, antioxidant system and photosynthesis of Microcystis flosaquae. J. Hazard Mater., 2015, 283, 778–786.

- Zhao, X.-L.; Li, P.; Zhang, S.-Q.; He, S.-W.; Xing, S.-Y.; Cao, Z.-H.; Lu, R.; Li, Z.-H. Effects of environmental norfloxacin concentrations on the intestinal health and function of juvenile common carp and potential risk to humans. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 287, 117612. [CrossRef]

- Abu-Zahra, N.I.S.; Atia, A.A.; Elseify, M.M.; Soliman, S. Biological and histological changes and DNA damage in Oreochromis niloticus exposed to oxytetracycline: a potential amelioratory role of ascorbic acid. Aquac. Int. 2023, 32, 1–28. [CrossRef]

- Matthee, C.; Brown, A.R.; Lange, A.; Tyler, C.R. Factors Determining the Susceptibility of Fish to Effects of Human Pharmaceuticals. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 8845–8862. [CrossRef]

- Bojarski, B.; Kot, B.; Witeska, M. Antibacterials in Aquatic Environment and Their Toxicity to Fish. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 189. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.R.; Tacão, M.; Machado, A.L.; Golovko, O.; Zlabek, V.; Domingues, I.; Henriques, I. LongTerm Effects of Oxytetracy1cline Exposure in Zebrafish: A Multi-Level Perspective. Chemosphere, 2019, 222, 333–344.

- Massarsky, A.; Kozal, J.S.; Di Giulio, R.T. Glutathione and zebrafish: Old assays to address a current issue. Chemosphere 2017, 168, 707–715. [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Dong, F.; Yin, L.; Wang, H.; Zheng, M.; Fu, S.; Zhang, W. Effects of sulfamethoxazole on the growth, oxidative stress and inflammatory response in the liver of juvenile Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquaculture 2021, 543, 736935. [CrossRef]

- Plhalova, L.; Zivna, D.; Bartoskova, M.; Blahova, J.; Sevcikova, M.; Skoric, M.; Marsalek, P.; Stancova, V.; Svobodova, Z. The effects of subchronic exposure to ciprofloxacin on zebrafish (Danio rerio). Neuroendocrinol Lett 2014, 64–70.

- Salahinejad, A.; Meuthen, D.; Attaran, A.; Chivers, D.P.; Ferrari, M.C. Effects of common antiepileptic drugs on teleost fishes. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 866, 161324. [CrossRef]

- Tiehm, A.; Schmidt, N.; Stieber, M.; Sacher, F.; Wolf, L.; Hoetzl, H. Biodegradation of Pharmaceutical Compounds and their Occurrence in the Jordan Valley. Water Resour. Manag. 2010, 25, 1195–1203. [CrossRef]

- Chiţescu, C.; Ene, A.; Bahrim, G.E.; Enachi, E. Pharmaceutical residues monitoring in surface water in Romania. Status and concerns. Environ. Toxic. Freshwater Marine Ecosys. Black Sea Basin, 2020, 55-56.

- Kim, Y.; Choi, K.; Jung, J.; Park, S.; Kim, P.-G.; Park, J. Aquatic toxicity of acetaminophen, carbamazepine, cimetidine, diltiazem and six major sulfonamides, and their potential ecological risks in Korea. Environ. Int. 2007, 33, 370–375. [CrossRef]

- Da Silva Santos, N.; Oliveira, R.; Lisboa, C.A.; Mona e Pinto, J.; Sousa-Moura, D.; Camargo, N.S.; Perillo, V.; Oliveira, M.; Grisolia, C.K.; Domingues, I. Chronic effects of carbamazepine on zebrafish: Behavioral, reproductive and biochemical endpoints. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 164, 297–304. [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Csenki, Z.; Ivánovics, B.; Bock, I.; Csorbai, B.; Molnár, J.; Vásárhelyi, E.; Griffitts, J.; Ferincz, Á.; Urbányi, B.; et al. Biochemical Marker Assessment of Chronic Carbamazepine Exposure at Environmentally Relevant Concentrations in Juvenile Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio). Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1136. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; H.; Li, P.; Rodina, M.; Randak, T. Effect of human pharmaceutical Carbamazepine on the quality parameters and oxidative stress in common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.) spermatozoa. Chemosphere, 2010, 80(5), 530-534.

- Gasca-Pérez, E.; Galar-Martínez, M.; García-Medina, S.; Pérez-Coyotl, I.A.; Ruiz-Lara, K.; Cano-Viveros, S.; Borja, R.P.-P.; Gómez-Oliván, L.M. Short-term exposure to carbamazepine causes oxidative stress on common carp (Cyprinus carpio). Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2018, 66, 96–103. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, D. G.; Aires, A.; de Lourdes Pereira, M.; Oliveira, M. Levels and effects of antidepressant drugs to aquatic organisms. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology, 2022, 256, 109322.

- Singh, A.; Saidulu, D.; Gupta, A.K.; Kubsad, V. Occurrence and fate of antidepressants in the aquatic environment: Insights into toxicological effects on the aquatic life, analytical methods, and removal techniques. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Orozco-Hernández, J.M.; Elizalde-Velázquez, G.A.; Gómez-Oliván, L.M.; Santamaría-González, G.O.; Rosales-Pérez, K.E.; García-Medina, S.; Galar-Martínez, M.; Juan-Reyes, N.S. Acute exposure to fluoxetine leads to oxidative stress and hematological disorder in Danio rerio adults. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 905, 167391. [CrossRef]

- Kosma, C.I.; Nannou, C.I.; Boti, V.I.; Albanis, T.A. Psychiatrists and selected metabolites in hospital and urban wastewaters: occurrence, removal, mass loading, seasonal influence and risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 659, 1473–1483.

- Christensen, A.M.; Markussen, B.; Baun, A.; Halling-Sørensen, B. Probabilistic environmental risk characterization of pharmaceuticals in sewage treatment plant discharges. Chemosphere 2009, 77, 351–358. [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, J.; Klaper, R. Environmental concentrations of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine impact specific behaviors involved in reproduction, feeding and predator avoidance in the fish Pimephales promelas (fathead minnow). Aquat. Toxicol. 2014, 151, 77–83. [CrossRef]

- Duarte, I.A.; Reis-Santos, P.; Novais, S.C.; Rato, L.D.; Lemos, M.F.; Freitas, A.; Pouca, A.S.V.; Barbosa, J.; Cabral, H.N.; Fonseca, V.F. Depressed, hypertense and sore: Long-term effects of fluoxetine, propranolol and diclofenac exposure in a top predator fish. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 712, 136564. [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Yang, M.; Xu, H.; Xu, B.; Jiang, L.; Wu, M. Tissue bioconcentration and effects of fluoxetine in zebrafish (Danio rerio) and red crucian cap (Carassius auratus) after short-term and long-term exposure. Chemosphere 2018, 205, 8–14. [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Lu, G.; Li, Y. Interactive effects of selected pharmaceutical mixtures on bioaccumulation and biochemical status in crucian carp (Carassius auratus). Chemosphere 2016, 148, 21–31. [CrossRef]

- Cunha, V.; Rodrigues, P.; Santos, M.; Moradas-Ferreira, P.; Ferreira, M. Danio rerio embryos on Prozac ⿿ Effects on the detoxification mechanism and embryo development. Aquat. Toxicol. 2016, 178, 182–189. [CrossRef]

- Duarte, I.A.; Reis-Santos, P.; Novais, S.C.; Rato, L.D.; Lemos, M.F.; Freitas, A.; Pouca, A.S.V.; Barbosa, J.; Cabral, H.N.; Fonseca, V.F. Depressed, hypertense and sore: Long-term effects of fluoxetine, propranolol and diclofenac exposure in a top predator fish. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 712, 136564. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, M.R. Fluoxetine and the mitochondria: a review of the toxicological aspects. Toxicol. Lett., 2016, 258, 185–191.

- Sathishkumar, P.; Meena, R.A.A.; Palanisami, T.; Ashokkumar, V.; Palvannan, T.; Gu, F.L. Occurrence, interactive effects and ecological risk of diclofenac in environmental compartments and biota - a review. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 698, 134057. [CrossRef]

- Jurado, A.; Labad, F.; Scheiber, L.; Criollo, R.; Nikolenko, O.; Pérez, S.; Ginebreda, A. Occurrence of pharmaceuticals and risk assessment in urban groundwater. Adv. Geosci. 2022, 59, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.; Joshi, M.; Bhatnagar, A.; Chaurasia, A.K.; Nigam, S. Pharmaceutical residues: One of the significant problems in achieving ‘clean water for all’and its solution, Environ. Res., 2022, 215, 114219.

- Lushchak, V.I. Contaminant-induced oxidative stress in fish: a mechanistic approach. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 42, 711–747. [CrossRef]

- Stoliar, O.B.; Lushchak, V.I. Environmental pollution and oxidative stress in fish. Oxidative stress-environmental induction and dietary antioxidants, Environmental Induction and Dietary Antioxidants, 2012, 131-166.

- Nava-Álvarez, R.; Razo-Estrada, A.C.; García-Medina, S.; Gómez-Olivan, L.M.; Galar-Martínez, M. Oxidative Stress Induced by Mixture of Diclofenac and Acetaminophen on Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio). Water, Air, Soil Pollut. 2014, 225, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Beghin, M.; Schmitz, M.; Betoulle, S.; Palluel, O.; Baekelandt, S.; Mandiki, S.N.; Gillet, E.; Nott, K.; Porcher, J.-M.; Robert, C.; et al. Integrated multi-biomarker responses of juvenile rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) to an environmentally relevant pharmaceutical mixture. 2021, 221, 112454. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).