Submitted:

10 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mukherjee, S.; Das, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Ghosh, P.S.; Bhattacharya, S. Arterial Blood Gas as a Prognostic Indicator in Patients with Sepsis. Indian J. Med Microbiol. 2020, 38, 457–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Backer, D.; Vincent, J.-L. Understanding Hyperlactatemia in Human Sepsis: Are We Making Progress? Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 200, 1070–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Fan, M.; Wang, X.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y.; Gill, P.S.; Ha, T.; Liu, L.; Hall, J.V.; Williams, D.L.; et al. Lactate induces vascular permeability via disruption of VE-cadherin in endothelial cells during sepsis. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabm8965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gattinoni, L.; Camporota, L.; Meessen, J.; Romitti, F.; Pasticci, I.; Duscio, E.; Vassalli, F.; Forni, L.G.; Payen, D.; Cressoni, M.; et al. Understanding Lactatemia in Human Sepsis. Potential Impact for Early Management. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 200, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantos, J.; Huespe, I.A.; Sinner, J.F.; Prado, E.M.; Roman, E.S.; Rolón, N.C.; Musso, C.G. Alactic base excess is an independent predictor of death in sepsis: A propensity score analysis. J. Crit. Care 2023, 74, 154248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smuszkiewicz, P.; Jawień, N.; Szrama, J.; Lubarska, M.; Kusza, K.; Guzik, P. Admission Lactate Concentration, Base Excess, and Alactic Base Excess Predict the 28-Day Inward Mortality in Shock Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, M.; Deutschman, C.S.; Seymour, C.W.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Annane, D.; Bauer, M.; Bellomo, R.; Bernard, G.R.; Chiche, J.-D.; Coopersmith, C.M.; et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016, 315, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, T.C.; Van Bommel, J.; Schoonderbeek, F.J.; Visser, S.J.S.; Van Der Klooster, J.M.; Lima, A.P.; Willemsen, S.P.; Bakker, J. Early Lactate-Guided Therapy in Intensive Care Unit Patients: A multicenter, open-label, randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2010, 182, 752–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, N.I.; Howell, M.D.; Talmor, D.; Nathanson, L.A.; Lisbon, A.; Wolfe, R.E.; Weiss, J.W. Serum Lactate as a Predictor of Mortality in Emergency Department Patients with Infection. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2005, 45, 524–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikkelsen, M.E.; Miltiades, A.N.; Gaieski, D.F.; Goyal, M.; Fuchs, B.D.; Shah, C.V.; Bellamy, S.L.; Christie, J.D. Serum lactate is associated with mortality in severe sepsis independent of organ failure and shock*. Crit. Care Med. 2009, 37, 1670–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.-L.; e Silva, A.Q.; Couto, L.; Taccone, F.S. The value of blood lactate kinetics in critically ill patients: a systematic review. Crit. Care 2016, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Xu, X. Lactate Clearance Is a Useful Biomarker for the Prediction of All-Cause Mortality in Critically Ill Patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis* Crit. Care Med. 2014, 42, 2118–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, S.A.; Lange, T.; Saugel, B.; Petzoldt, M.; Fuhrmann, V.; Metschke, M.; Kluge, S. Severe hyperlactatemia, lactate clearance and mortality in unselected critically ill patients. Intensiv. Care Med. 2015, 42, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gladden, L.B. Lactate metabolism: a new paradigm for the third millennium. J. Physiol. 2004, 558, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellum, J.A. Determinants of blood pH in health and disease. Crit. Care 2000, 4, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noritomi, D.T.; Soriano, F.G.; Kellum, J.A.; Cappi, S.B.; Biselli, P.J.C.; Libório, A.B.; Park, M. Metabolic acidosis in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock: A longitudinal quantitative study. Crit. Care Med. 2009, 37, 2733–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.-L.; Moreno, R. Clinical review: Scoring systems in the critically ill. Crit. Care 2010, 14, 207–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, L.W.; Mackenhauer, J.; Roberts, J.C.; Berg, K.M.; Cocchi, M.N.; Donnino, M.W. Etiology and Therapeutic Approach to Elevated Lactate Levels. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2013, 88, 1127–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jaghbeer, M.; Kellum, J.A. Acid–base disturbances in intensive care patients: etiology, pathophysiology and treatment. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2014, 30, 1104–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seifter, J.L.; Chang, H.-Y. Disorders of Acid-Base Balance: New Perspectives. Kidney Dis. 2016, 2, 170–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubin, A.; Menises, M.M.; Masevicius, F.D.; Moseinco, M.C.; Kutscherauer, D.O.; Ventrice, E.; Laffaire, E.; Estenssoro, E. Comparison of three different methods of evaluation of metabolic acid-base disorders*. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 35, 1264–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusack, R.; Rhodes, A.; Lochhead, P.; Jordan, B.; Perry, S.; Ball, J.; Grounds, R.; Bennett, E. The strong ion gap does not have prognostic value in critically ill patients in a mixed medical/surgical adult ICU. Intensiv. Care Med. 2002, 28, 864–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Maciel, A.T.; Noritomi, D.T.; de Azevedo, L.C.P.; Taniguchi, L.U.; Neto, L.M.d.C. Effect of Paco2 variation on standard base excess value in critically ill patients. J. Crit. Care 2009, 24, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, M.; Taniguchi, L.; Noritomi, D.; Libório, A.; Maciel, A.; Cruz-Neto, L. Clinical utility of standard base excess in the diagnosis and interpretation of metabolic acidosis in critically ill patients. Braz. J. Med Biol. Res. 2008, 41, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diao, M.-Y.; Wang, T.; Cui, Y.-L.; Lin, Z.-F. [Prognostic value of arterial lactate content combined with base excess in patients with sepsis: a retrospective study]. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue 2013, 25, 211–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables a |

Survivors N=90 |

Nonsurvivors N=128 |

P value univariate |

| Age |

71 (60-80) | 71 (59-79) | 0.990 |

| Male |

41 (46) | 74 (58) | 0.074 |

| APACHE II |

23 (18-27) | 28 (23-33) | <0.001 |

| SOFA |

9 (7-12) | 12 (9-14) | <0.001 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 3 (2-5) |

3 (2-5) | 0.978 |

| Creatinin |

2.33 (0.96-3.79) | 1.9 (1.3-2.9) | 0.401 |

| Serum sodium |

134 (138-144) | 139 (134-1449 | 0.704 |

| Serum chloride |

101 (96-107) | 101 (94-106) | 0.472 |

| PH |

7.38 (7.30-7.46) | 7.38 (7.27-7.46) | 0.717 |

| Standart HCO3 |

22 (18-25) | 20 (16-24) | 0.030 |

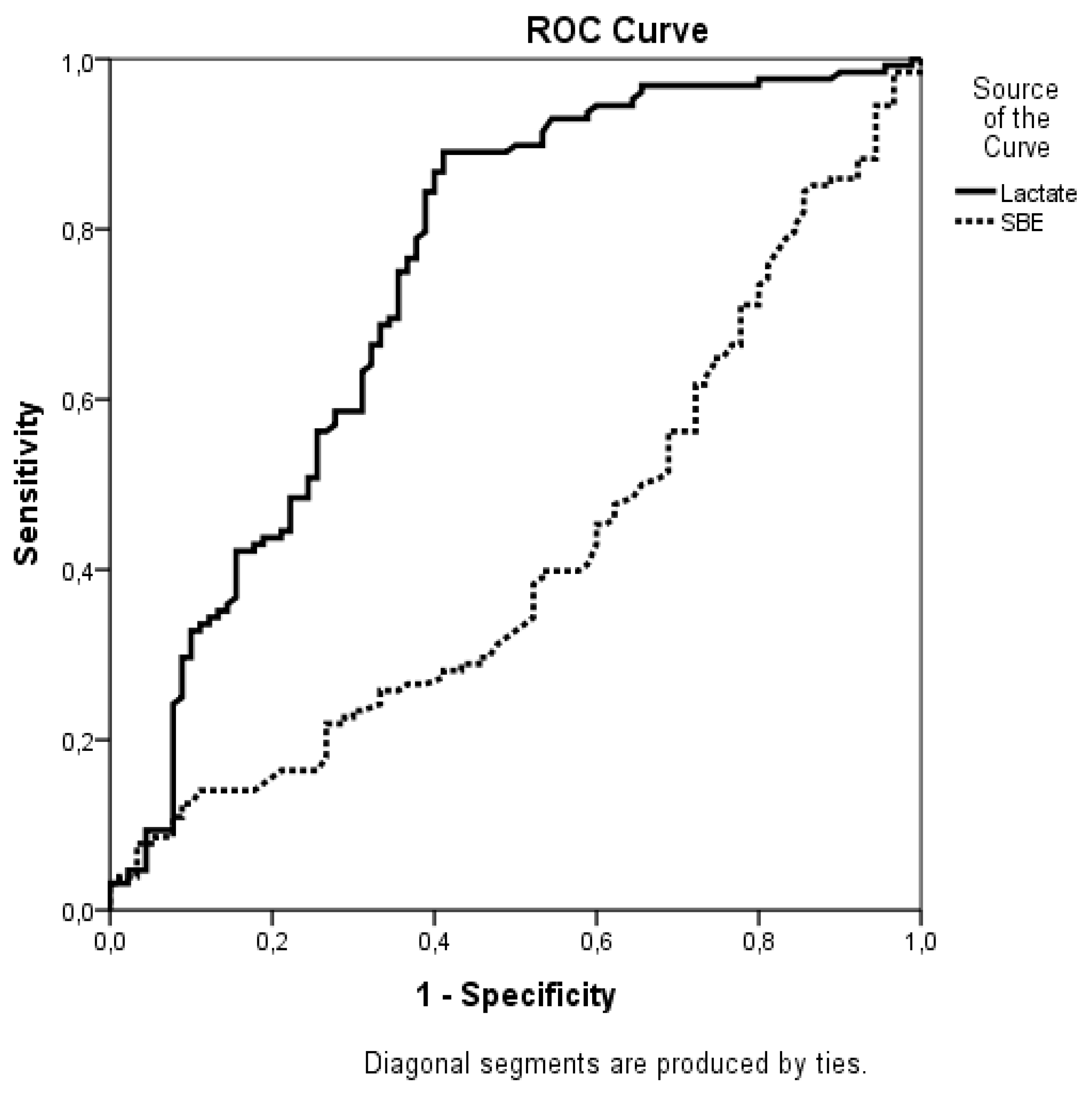

| SBE |

-2.8 ( -7.6 - +0.9) | -5.1 (-9.8 - -1) | 0.046 |

| Lactate |

1.2 (1.8-2.9) | 2.9 ( 2.3 - 4.1) | <0.001 |

| ABE |

-0.5 (-4.8- +2.2) | -1.6 (-5.6 - +2.2) | 0.551 |

| Vasopressor use |

64 (71.1) | 124 (97) | <0.001 |

| IMV |

34 (38) | 110 (86) | <0.001 |

| Hemodialysis |

32 (36) | 73 (57) | 0.002 |

| Length of ICU days |

7 (4-13) | 8 (4-16) | 0.166 |

| Variables | OR | %95 CI | P value |

| APACHE II score | 1.08 | 1.02-1.15 | 0.013 |

| Lactate level | 1.40 | 1.11-1.77 | 0.005 |

| Vasopressore use | 1.32 | 1.05-1.68 | 0.028 |

| IMV | 1.45 | 1.10-1.92 | 0.012 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).