Submitted:

10 January 2025

Posted:

13 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Integration of I-XR in Healthcare Education

1.2. Review of I-XR Studies for Training Effectiveness in Healthcare Education

1.3. Summary

1.4. Purpose

2. Methods

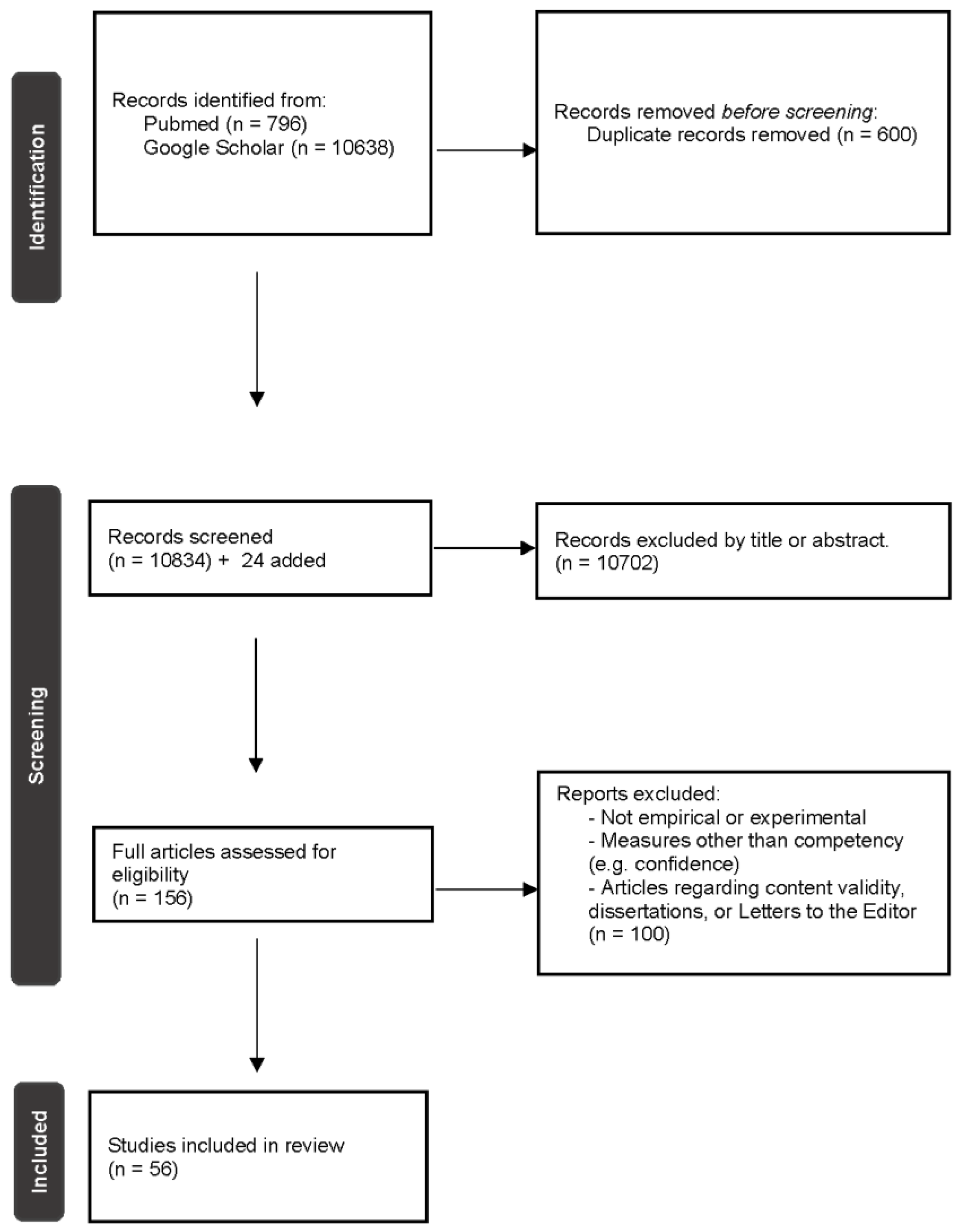

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Data Coding

2.5. Assessing Article Quality and Bias

3. Results

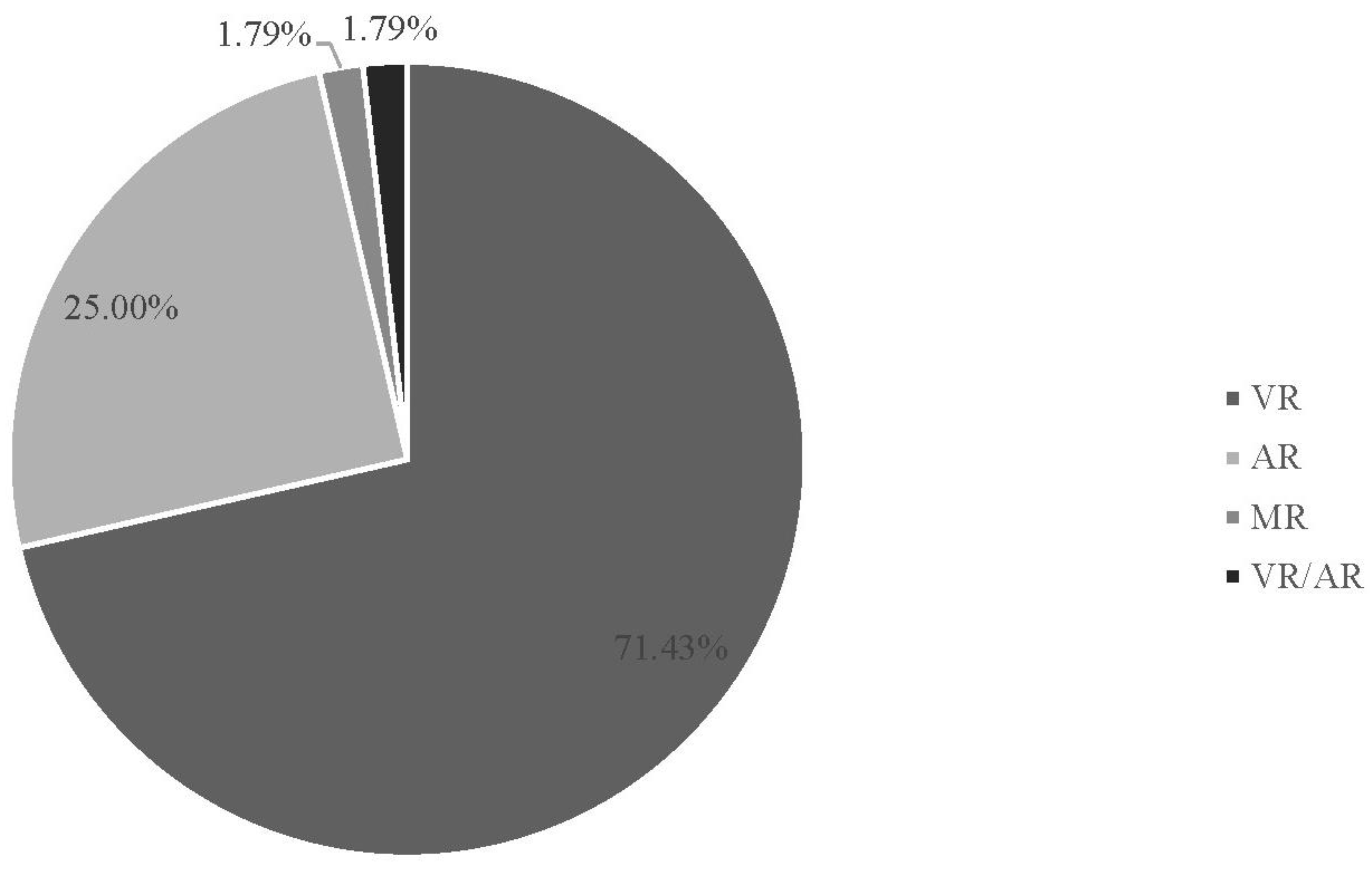

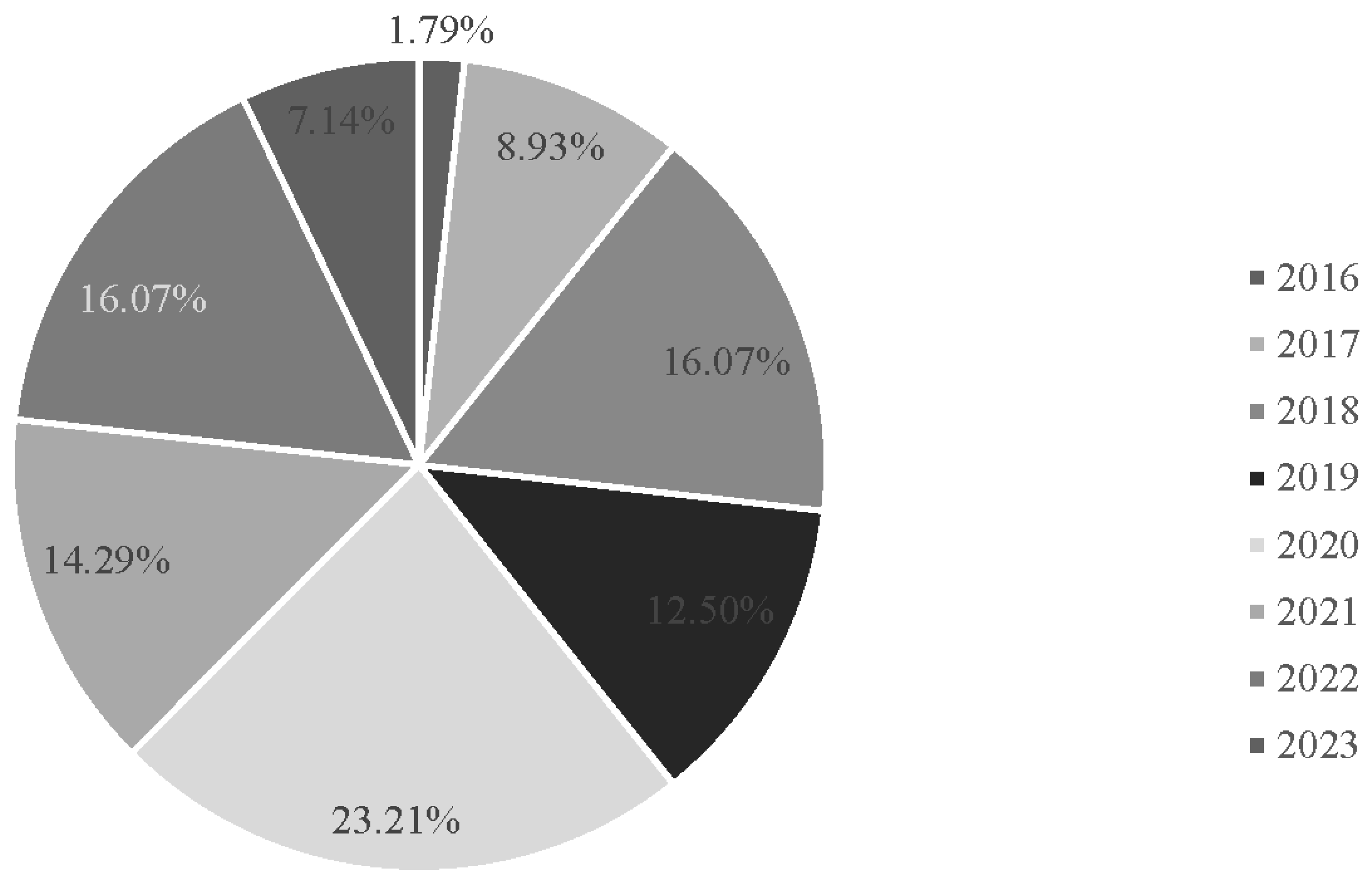

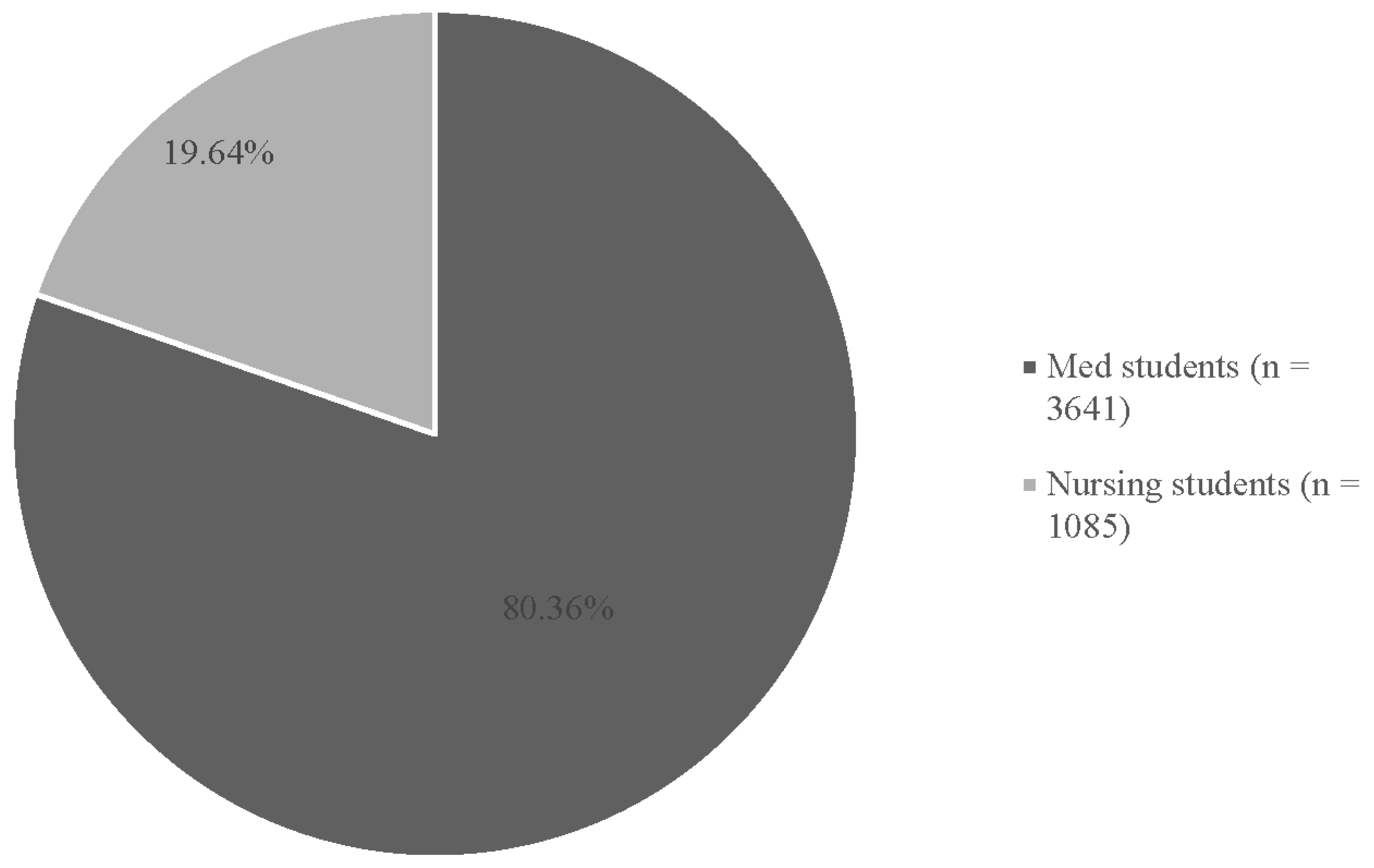

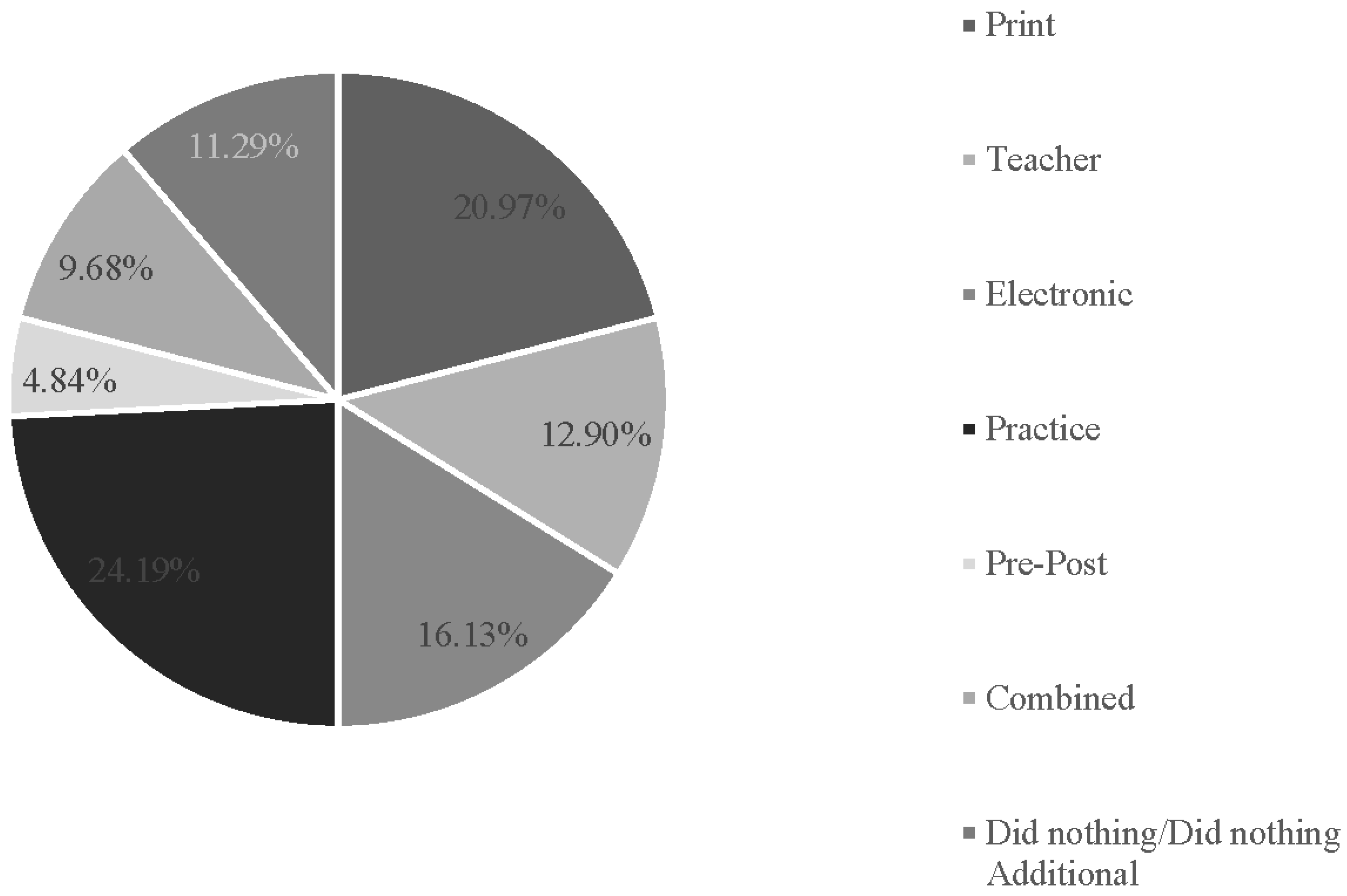

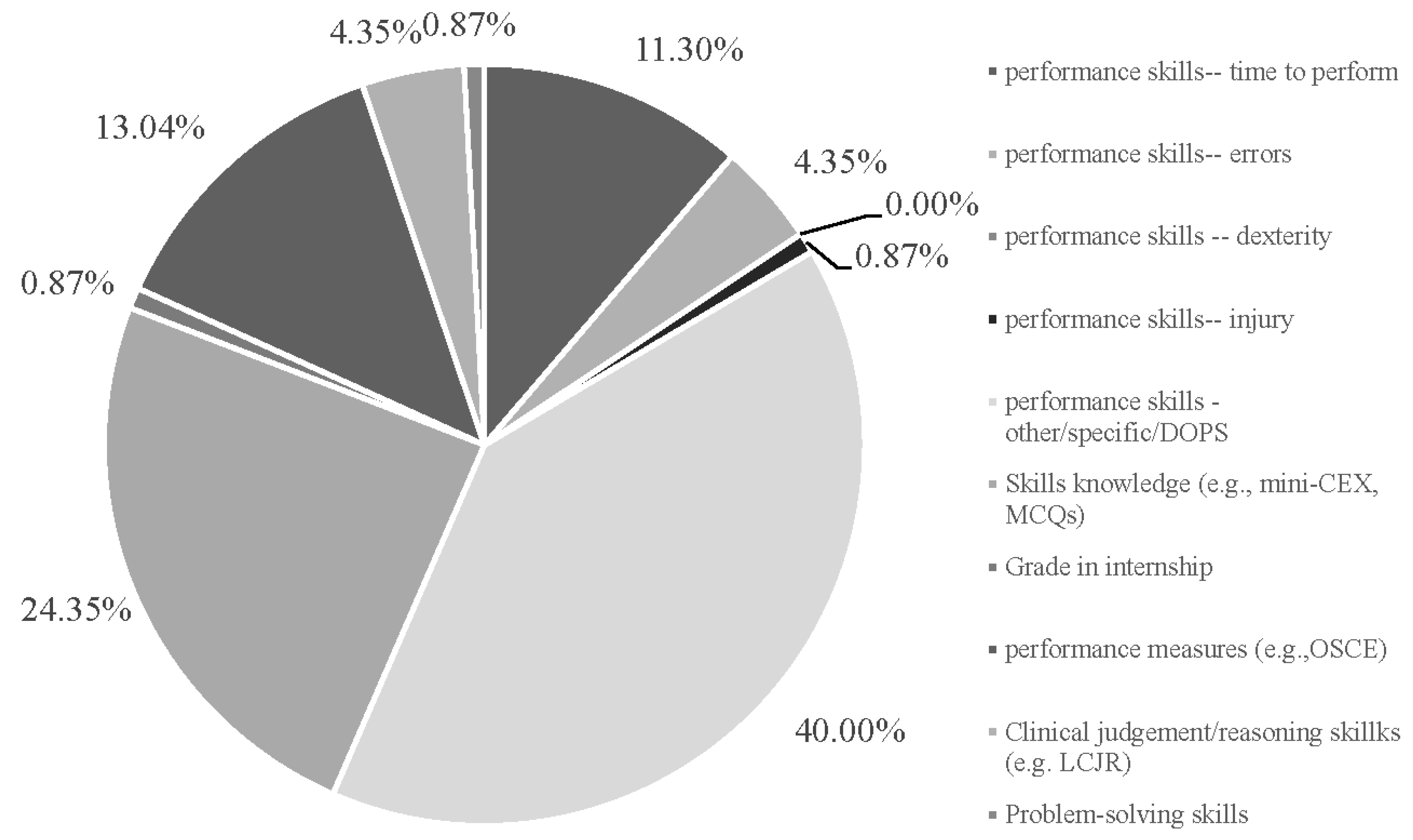

3.1. Descriptive Findings

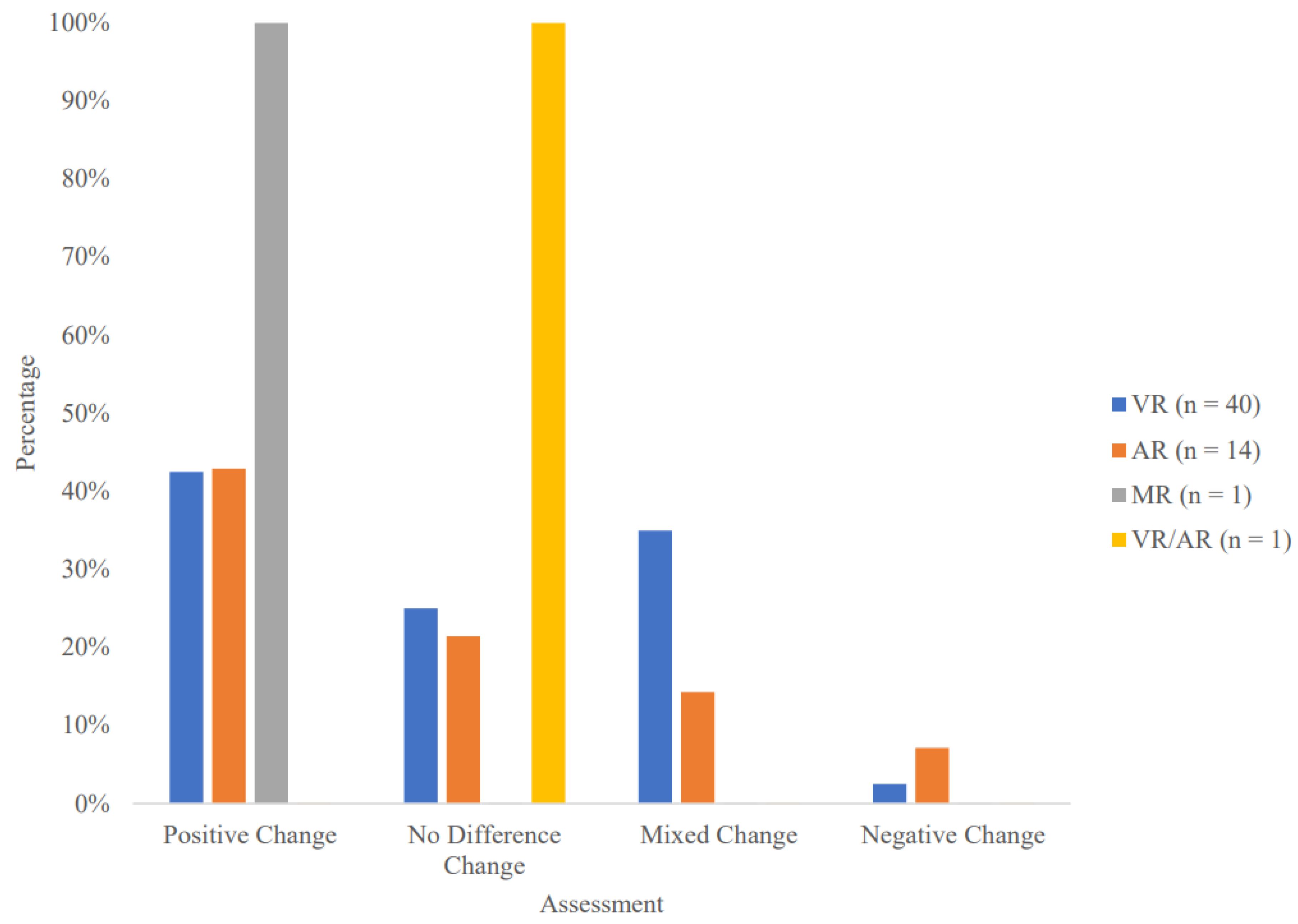

3.2. Overall Study Assessments of I-XR Skill Competency

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbas, J.R.; Chu, M.M.; Jeyarajah, C.; Isba, R.; Payton, A.; McGrath, B.; Tolley, N.; Bruce, I. Virtual reality in simulation-based emergency skills training: A systematic review with a narrative synthesis. Resusc Plus 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aebersold, M.; Dunbar, D.M. Virtual and augmented realities in nursing education: State of the science. Annu Rev Nurs Res. 2020, 39, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajemba, M.N.; Ikwe, C.; Iroanya, J.C. Effectiveness of simulation-based training in medical education: assessing the impact of simulation-based training on clinical skills acquisition and retention: A systematic review. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews 2024, 21, 1833–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayub, S.M. See one, do one, teach one: Balancing patient care and surgical training in an emergency trauma department. J Glob Health 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankar, M.N.; Bankar, N.J.; Singh, B.R.; Bandre, G.R.; Shelke, Y.P.; Bankar, M.; Shelke, Y.P. The role of E-content development in medical teaching: How far have we come? Cureus 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskaran, R.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Ganesananthan, S. Enhancing medical students’ confidence and performance in integrated structured clinical examinations (ISCE) through a novel near-peer, mixed model approach during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Med Educ. 2023, 23, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, L.R.; Hermosura, B.A. (2019). Comprehensive healthcare simulation: obstetrics and gynecology. Springer. (pp. 11–24). ISBN 978-3-319-98994-5.

- Chen, C.Y.; Huang, T.W.; Kuo, K.N.; Tam, K.W. Evidence-based health care: a roadmap for knowledge translation. J Chin Med Assoc. 2017, 80, 747–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.Q.; Leng, Y.F.; Ge, J.F.; Wang, D.W.; Li, C.; Chen, B.; Sun, Z.L. Effectiveness of virtual reality in nursing education: meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2020, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chengoden, R.; Victor, N.; Huynh-The, T.; Yenduri, G.; Jhaveri, R.H.; Alazab, M.; Gadekallu, T.R. Metaverse for healthcare: A survey on potential applications, challenges, and future directions. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 12765–12795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. Available online: http://www.casp-uk.net/. (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- Dicheva, N.K.; Rehman, I.U.; Husamaldin, L.; Aleshaiker, S. (2023). Improving nursing educational practices and professional development through smart education in smart cities: A systematic literature review. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Smart Cities Conference, Bucharest, Romania, 24 September (pp. 1–7).

- Dodson, T.M.; Reed, J.M.; Cleveland, K. Exploring undergraduate nursing students’ ineffective communication behaviors in simulation: A thematic analysis. Teach Learn Nurse 2023, 18, 480–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokides, E.; Atsikpasi, P.; Arvaniti, P.A. Lessons learned from a project examining the learning outcomes and experiences in 360o videos. Journal of Educational Studies and Multidisciplinary Approaches 2021, 1, 50–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q. N.; Gonzalez-Reyes, A.; Pluye, P. Improving the usefulness of a tool for appraising the quality of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 2018, 24, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horowitz, M.L.; Stone, D.S.; Sibrian, J.; DuPee, C.; Dang, C. An innovative approach for graduate nursing student achievement of leadership, quality, and safety competencies. J Prof Nurs. 2022, 43, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huai, P.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Liu, N.; Yang, H. The effectiveness of virtual reality technology in student nurse education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurse Educ Today 2024, 138, 106189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultquist, B.L., & Bradshaw, M.J. (Eds.). Innovative teaching strategies in nursing and related health professions, 7th ed; Jones & Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 978-1284107074.

- Issa, T.; Isaias, P.T.; Kommers, P. Guest editors’ introduction- Special issue on digital society and e-technologies. Pacific Asia Journal of the Association for Information Systems 2013, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issenberg, B.S; Mcgaghie, W.C.; Petrusa, E.R.; Lee, Gordon D. ; Scalese, R.J. Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: A BEME systematic review. Med Teach. 2005, 27, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jallad, S.T.; Işık, B. The effectiveness of virtual reality simulation as a learning strategy in the acquisition of medical skills in nursing education: a systematic review. Ir J Med Sci. 2022, 191, 1407–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaros, S.; Dallaghan, G.B. Medical education research study quality instrument: an objective instrument susceptible to subjectivity. Med Educ Online 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J. , & Fryer, L.K. The effect of virtual reality learning on students' motivation: A scoping review. J Comput Assist Learn. 2024, 40, 360–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual: 2014 Edition. Available online: http://www.joannabriggs.org/sumari.html (accessed on day month year).

- Kaufman, D.M.; Mann, K.V. (2010). Teaching and learning in medical education: how theory can inform practice. In Understanding Medical Education: Evidence, Theory, and Practice. Swanwick, T. (Eds.). Wiley Online Library: New York, USA. (pp. 16–36). ISBN: 978-1-405-19680-2. [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Plahouras, J.; Johnston, B.C.; Scaffidi, M.A.; Grover, S.C.; Walsh, C.M. Virtual reality simulation training for health professions trainees in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivuti-Bitok, L.W.; Cheptum, J.J.; Mutwiri, M.; Wanja, S.; Ngune, I. Virtual reality and serious gaming in re-engineering clinical teaching: a review of literature of the experiences and perspectives of clinical trainers. Afr J Health Nurs Midwifery 2022, 6, 53–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolcun, K.; Zellefrow, C.; Karl, J.; Ulloa, J.; Zehala, A.; Zeno, R.; Tornwall, J. Identifying best practices for virtual nursing clinical education: A scoping review. J Prof Nurs. 2023, 48, 128–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovoor, J.G.; Gupta, A.K.; Gladman, M.A. Validity and effectiveness of augmented reality in surgical education: a systematic review. Surgery 2021, 170, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Cook, B.; Manning, W.; Alegria, M. Measuring disparities across the distribution of mental health care expenditures. The Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics 2013, 16, 3–PMC3662479. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, F.; Bowman, D.A. (2021). Evaluating the potential of glanceable AR interfaces for authentic everyday uses. 2021 IEEE Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces. (pp. 768–777). [CrossRef]

- Macrine, S.L.; Fugate, J.M.B. (Eds.) (2022). Movement Matters: How Embodied Cognition Informs Teaching and Learning. MIT Press. [CrossRef]

- Mann, K.V. Theoretical perspectives in medical education: past experience and future possibilities. Medical Education 2011, 45, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, J.L.; Tekman, J.M.; Dev, P.; Danforth, D.R.; Mohan, D.; Kman, N.; Crichlow, A.; Bond, W.F. Using virtual reality simulation environments to assess competence for emergency medicine learners. Acad Emerg Med. 2018, 25, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottle, J. Virtual reality and the transformation of medical education. Future Healthc J. 2019, 6, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrich, R.J. See one, do one, teach one: An old adage with a new twist. Plastic Reconstructive Surgery 2006, 118, 257–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.; Khan, Z. Healthcare Simulation: An effective way of learning in health care. Pak J Med Sci. 2023, 39, 1185–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezgin, M.G.; Bektas, H. Effectiveness of interprofessional simulation-based education programs to improve teamwork and communication for students in the healthcare profession: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nurse Educ Today 2023, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.K.; Taunk, N.K.; Maxwell, R.; Wang, X.; Hubley, E.; Anamalayil, S.; Trotter, J.W.; Li, T. Comparison of virtual reality platforms to enhance medical education for procedures. Front Virtual Real. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Zeng, Y. Simulation-based training versus non-simulation-based training in anesthesiology: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, K.S.; Cheng, D.L.; Mi, E.; Greenberg, P.B. Augmented reality in medical education: A systematic review. Can Med Educ J. 2020, 11, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonteri, T.; Holopainen, J.; Lumivalo, J.; Tuunanen, T.; Parvinen, P.; Laukkanen, T. (2023). Immersive virtual reality in experiential learning: A value co-creation and co-destruction approach. In Proceedings of the 56th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Hawaii, USA, January 2023, pp. 1313–1322. https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/cb46cecd-c8e2-4f8e-9c37-c44af3ae0d32/content.

- Uslu-Sahan, F.; Bilgin, A.; Ozdemir, L. Effectiveness of virtual reality simulation among BSN students: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Comput Inform Nurs. 2023, 41, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Merriënboer, J.J. , & Sweller, J. Cognitive load theory in health professional education: design principles and strategies. Med Educ. 2010, 44, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velev, D.; Zlateva, P. Virtual reality challenges in education and training. Int J Learn Teach. 2017, 3, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. (2014). Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale cohort studies. University of Ottawa. https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

- Whiting, P.F.; Rutjes, A.W.; Westwood, M.E.; Mallett, S.; Deeks, J.J.; Reitsma, J.B.; Leeflang, M.M.; Sterne, J.A.; Bossuyt, P.M. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011, 155, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlgenannt, I.; Simmon, A.; Stieglitz, S. Virtual reality. Bus Inf Syst Eng. 2020, 62, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.W.; Norvell, M. To improve patient safety, lean in. J Patient Saf Risk Manag. 2022, 27, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lu, V.; Khanduja, V. The impact of extended reality on surgery: a scoping review. Int Orthop. 2023, 47, 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziv, A.; Wolpe, P.R.; Small, S.D.; Glick, S. Simulation-based medical education: An ethical imperative. Acad Med. 2003, 78, 783–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zweifach, S.M.; Triola, M.M. Extended reality in medical education: driving adoption through provider-centered design. Digital Biomark. 2019, 3, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Authors | Date | Type of I- XR | Population studied/ Setting | Number of participants | Control Group | Basic Experimental design/ Description | Results | DVs | Outcome Evidence for I-XR | Study Evidence for I-XR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aebersold et al | 2018 | AR | nursing - tube placement | 69 nursing students | 1 (Combined) | Nursing students were tested on their ability to place a nasogastric tube. They were randomly assigned to either usual training (which included both video and didactic content) or an iPad anatomy-augmented virtual simulation training module. | The AR group was able to more accurately and successfully place the NGT, p = 0.011. CONTROL: n = 34, M = 15.39 (SD = 1.01). EXPERIMENAL: n = 35) , M = 15.96 (SD = 0.75). |

1 (performance skills - specific) | + Performance skills | Positive |

| Andersen et al. | 2021 | VR + Electronic* | Medical - catheter placement | 19 medical students | 1 (Did nothing additional) | Students were split into two different training groups: immersive virtual reality versus the control group. Both groups viewed videos showing ultrasound-guided peripheral venous cannulation placement. The control group was given no further training. | The immersive VR group was significantly more successful at peripheral venous cannulation placement in comparison to the control group, p ≤ 0.001. CONTROL: n = 9, M = 22.2% placement [0.11, 0.41]. EXPERIMENTAL: n = 10, M = 73.3% placement [0.56, 0.86] . |

1 (performance skills - specific) | + Performance skills | Positive |

| Andersen et al. | 2022 | VR | medical - Ultrasound skills | 104 medical students | 1 (Teacher) | Medical students were divided into two groups to learn Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) skills: a self-directed immersive virtual reality (IVR) group versus an instructor-led learning group. US skills were then assessed according to an OSAUS test. | There were no significant differences between the self-directed IVR and instructor-led groups in terms of OSAUS scoring or any other subgroup objectives. Overall effect, p = 0.36. EXPERIMENTAL: n = 51, M = 10.3 [9.0, 11.5]. CONTROL: n = 53, M = 11.0 [9.8, 12.2]. |

1 (performance measures - OSCE) | X No difference performance measures | No Difference |

| Arents et al | 2021 | VR | medical - Obstetrics training | 89 medical students | 1 (Print) | Two weeks prior to medical students' OB/Gyn internship, students underwent teaching on gentle Caesarean Sections (gash) and general obstetric knowledge. Students were divided into either a control group that underwent conventional study, or an experimental group who watched 360-degree videos using VR. After the internship, the authors analyzed the grade received for the internship, as well as administered both open-ended and multiple-choice question tests. | No significant difference in internship grade between groups, p = .66 (adjusted 0.68). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 53, M = 7.75 CONTROL: n = 48, M = 7.83 Mean difference CI [-0.33, 0.16]. No significant difference on multiple-choice testing (skills knowledge) between the groups, p = 0.91 (adjusted 0.68). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 53, M = 6.63. CONTROL: n = 48, M = 6.67 Mean difference CI [-0.61, 0.55]. |

2 (Grade internship) (Skills knowledge based on MCQs) | X No difference Grade internship X No difference Skills knowledge |

No Difference |

| Azimi et al. | 2018 | AR | nursing - IV placement & Chest compression | 20 nursing students | 1 (Practice) | Students underwent either standard training or training with AR via a head-mounted display for learning needle chest decompression and IV-line placement skills. The students’ skills were measured with a post-assessment both immediately after training and 3 weeks later. | Results are assessed with respect to control immediately after. The AR head-mounted group displayed better needle chest decompression skills. No p value or M, SD reported. No significant difference in IV placement performance was found between groups. No p value or M or SD reported. EXPERIMENTAL: n = 10 CONTROL: n = 10 |

2 (performance skills - specific chest) (performance skills- other IV) | + Performance skills X No difference performance skills |

Mixed Positive |

| Banaszek et al. | 2017 | VR | Medical - surgery | 40 medical students | 2 (Practice) (Did nothing) | Medical students underwent five weeks of independent training sessions in one of three groups: a high-fidelity virtual reality arthroscopic simulator, a bench-top arthroscopic simulator, or an untrained group (control). To measure post-test skill acquisition, students performed a diagnostic arthroscopy on both simulators and were tested in a simulated intraoperative environment using a cadaveric knee. A more difficult surprise skills transfer test was also administered. Students were evaluated using the Global Rating Scale (GRS) and a timer to determine efficiency. | Results are not reported for cross-over group post training. Both the high-fidelity VR simulator and bench-top arthroscopic simulator groups showed significant improvement in arthroscopic skills compared to the control, p < 0.05 for both. The VR simulation group showed the greatest improvement in performance in the diagnostic arthroscopy crossover tests using the GRS), p < 0.001. CONTROL: n = not reported, MD = 0.75 (SD only reflected in error bars). EXPERIMENTAL VR: n = not reported, MD = 12.6 (SD only reflected in error bars). VR group showed the fastest improvement simulated cadaveric setup with timer, p < .001. CONTROL: n = not reported, MD = 9.1 (SD only reflected in error bars). EXPERIMENTAL VR: n = not reported, MD = 17.3 (SD only reflected in error bars). |

2 (performance measures GRS) (performance skills -time) | + Performance measures + Performance skills |

Positive |

| Bayram & Caliskan | 2019 | VR | nursing -tracheostomy care | 172 nursing students | 1 (Combined) | Nursing students were divided into control and VR groups for tracheostomy care and skill knowledge. Both groups completed a theoretical class, labs, and small group study. The experimental group was provided a game-based virtual reality phone application. Skills knowledge was assessed using the FEMA IS-346 exam, and performance skills were assessed using the Decontamination Checklist for performance. | Results for the less immersive VR are not reported. Only the immersive experimental group is compared to the control group. Both groups increased their skills performance after training, but did not differ from one another, p = 0.443. CONTROL: n = 58, M = 13.48 (SD = 0.30). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 59, M = 14.24 (SD = 0.29). Both groups increased their skills knowledge after training, but did not differ from one another, p = 1.00. CONTROL: n = 58, M = 16.07 (SD = 0.30). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 59, M = 16.25 (SD = 0.29). |

2 (performance skills - specific suctioning) (skills knowledge) | X No difference performance skills X No difference skills knowledge |

No Difference |

| Blumstein et al | 2020 | VR | medical - surgery | 20 medical students | 1 (Print) | Medical students were randomized into either standard guide (SG) or virtual reality (VR) learning groups to learn intramedullary nailing (IMN) of the tibia. Students then performed a simulated tibia IMN procedure immediately following their training and were evaluated by an attending surgeon using a procedure-specific checklist and 5-point global assessment scale. Students returned 2 weeks later for repeat training and testing. | The VR groups showed significantly higher global assessment scores, p < 0.001. CONTROL: n = 10, M = 7.5, SD = not reported. EXPERIMENTAL: n = 10, M = 17.5, SD = not reported. The VR also completed a higher percentage of steps correctly according to the procedure-specific checklist, p < 0.002. CONTROL: n = 10, M =25 , SD = not reported. EXPERIMENTAL: n = 10, M = 63, SD = not reported. |

2 (performance skills - specific) (performance measures) | + Performance skills + Performance measures |

Positive |

| Bogomolova et al | 2020 | AR | BIO medical students -anatomy | 58 (bio)medical students | 2 (Print) (Practice) | Students were divided into three groups: (1) stereoscopic 3D Augmented-Reality (AR) group, (2) monoscopic 3D desktop model group, or (3) 2D anatomical atlas group. Students were told what the learning goals consisted of and were given instructions for the session. Visual-spatial abilities were measured before the learning session began. Post-session learning was measured using a 30-question knowledge test that tested factual, functional, and spatial organization of anatomical structures. | All groups performed equally well on the knowledge test, p = 1.00. Results are between the AR and atlas control. CONTROL: n = 18, M = 50.9 (SD = 13.8). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 20, M = 47.8 (SD = 9.8). |

1 (skills knowledge) | X No difference skills knowledge | No Difference |

| Bork et al. | 2019 | AR | medical - anatomy | 749 medical students | 2 (Print) (Practice) | Medical students were divided into one of three groups: (1) the control group using radiology atlases, (2) a virtual dissection table, or (3) AR Magic Mirror. A pre and post-test was taken about anatomy questions. | Pre-post not evaluated for final assessment. Both the AR Magic Mirror group and the Theory (control) group showed significantly increased post-test scores but did not differ from one another. No p value for comparison between change in improvement given. Results are from the post scores between the AR and the theory from print control group. CONTROL: n = 24, M = 50.60, (SD = 12.53). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 24, M = 48.00 (SD = 13.07). |

1 (skills knowledge) | X No difference skills knowledge | No Difference |

| Brinkmann et al. | 2017 | VR | med medical - surgery | 36 medical students | 1 (Practice) | Medical students underwent a 5-day laparoscopic basic skills training course using either a box-trainer or virtual reality (VR) training curriculum. Skills were measured by students' performance of an ex-situ laparoscopic cholecystectomy on a pig liver using RT and errors. The performance was evaluated by the Global Operative Assessment of Laparoscopic Skills (GOALS) score. | Both groups showed significant improvement in their acquisition of laparoscopic basic skills, and the two groups did not differ in improvement on the peg transfer, p = 0.311. CONTROL: n = 18, M = 53 (SD = 21.3). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 18 , M = 44.4 (SD = 14.9). The two groups also did not differ on their pattern cutting, p = 0.088. CONTROL: n = 18, M = 31.6 (SD = 17.3). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 18 , M = 42.6 (SD = 16.9). The two groups did not differ on loop placement, p = 0.174. CONTROL: n = 18, M = 46.3 (SD = 54). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 18 , M = 53.1 (SD = 32.5). The two groups did not differ on their knot tying, p = 0.174. CONTROL: n = 18, M = 37.2 (SD = 11.9). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 18, M = 42.6 (SD = 16.4). The GOALS scores on four of the five items were significantly higher in the box-trained group compared to the VR-trained group (individual comparisons in Table 5 of original publication). |

5 (performance skills – other peg) (performance skills – other cutting) (performance skills - other loop) (performance skills – other knot) (performance measures- GOALS) |

X No difference performance skills X No difference performance skills X No difference performance skills X No difference performance skills - Performance measures |

Mixed Negative |

| Bube et al. | 2020 | VR | medical- cystoscopy | 32 medical students | 1 (Teacher) | Two groups of medical students completed endoscopic procedure training. The control group underwent traditional lecture-based training whereas the experimental group used VR and other self-directed simulation training methods. Three weeks after the training, participants performed cystoscopies on two patients, and performance was measured using a global rating scale (GRS). | No significant difference in performance between the two groups was found after training, p = 0.63. CONTROL: n = 12, M = 14.3. EXPERIMENTAL: n = 13, M = 13.6. CI of the difference only reported: [-2.4, 3.9]. |

1 (performance measures - GRS) | X No difference performance measures | No Difference |

| Butt et al. | 2018 | VR | nursing - catheter | 20 nursing students | 1 (Combined) | Nursing students were assigned to either a control group (traditional learning with a task trainer) or an experimental group (VR software/game) to learn catheter insertion skills. Skills were assessed approximately two weeks after completion of the training session. | VR group completed more procedures than traditional group, p < 0.001. CONTROL: n = 10, M = 1.8 (SD = 0.42). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 10, M = 3.0 (SD = 1.3). Pass rates at two weeks were identical, no p value given. |

2 (performance skills – other number of procedures completed) (performance skills – other specific pass rates) | + Performance skills X No difference performance skills |

Mixed Positive |

| Cevallos et al. | 2022 | VR | medical - surgery | 20 medical students and orthopedic residents | 1 (Combined) | Medical students and orthopedic residents were randomized into either standard guide (SG) or virtual reality (VR) learning groups to learn pinning of a slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE), a pediatric orthopedic surgery procedure. All participants watched a technique video, and the VR group completed additional training on the Osso VR surgical trainer. Participants then were asked to achieve "ideal placement," and performed a SCFE guidewire placement on Sawbones model 1161. Evaluation was based on time, number of pins "in-and-outs", articular surface penetration, angle between the pin and physis, distance from pin tip to subchondral bone, and distance from center-center point of the epiphysis. | The VR group showed superiority across multiple domains but where not statistically different from the control in the following: time to final pine placement, p = 0.26. CONTROL: n = 10, M = 706 (SD shown in figure). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 10, M = 573 (SD shown in figure). VR performed better compared to control for pin in and out p = 0.28. CONTROL: n = 10, M = 1.7 (SD shown in figure). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 10, M = 0.5 (SD shown in figure). VR group performed fewer surface penetrations, p = 0.36. CONTROL: n = 10, M = 0.4 (SD shown in figure). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 10, M = 0.2 (SD shown in figure). VR group had smaller distance pin to tip to subchondral bone, p = 0.42. CONTROL: n = 10, M = 5.8 (SD = 3.36). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 10, M = 7.2 (SD = 6.5). VR group had lower angle deviation between the pin and physis, p < 0.05. CONTROL: n = 10, M = 4.9 (SD = 3.0). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 10, M = 2.5 (SD = 1.42). |

5 (performance skills - time) (performance skills – other specific pin in and outs) (performance skills - errors) (performance skills – other specific pin tip to bone) (performance skills – other specific angle) |

X No difference performance skills X No differenceperformance skills X No difference performance skills X No difference performance skills + Performance skills |

Mixed Positive |

| Chao et al | 2021 | VR | nursing - tube placement | 45 nursing students | 1 (Electronic) | Nursing students were randomly assigned into two groups to learn nasogastric (NG) tube feeding: (1) immersive 3D interactive video program group or (2) regular demonstration video. Students completed a pre- and post-intervention questionnaire, which included a nasogastric tube feeding quiz (NGFQ) to study NG tube feeding knowledge. Students were assessed after intervention and 1 mo. Later. | Knowledge scores on NG tube feeding improved significantly in both groups; however, there was no significant difference in the knowledge scores after treatment, p = 0.77 CONTROL: n = 23, M = 11.7 (SD =1.86). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 22, M = 11.9 (SD = 2.04). |

1 (skills knowledge) | X No difference skill knowledge | No Difference |

| Chao et al | 2022 | VR | Medical - intake skills | 64 medical students | 1 (Electronic) | Students were randomized into two groups and received either a 10-minute immersive 360-degree virtual reality or a 2D virtual reality instructional video on history taking and physical examination skills. Within 60 minutes of watching the video, students performed a focused history and physical on a patient. The Direct Observation of Procedural Skills (DOPS) was used to measure physical exam skills, and the Mini-CEX was used to measure general history and physical exam skills. | The average DOPS-total score was significantly higher in the VR video group compared to the 2D video group, p = .01. CONTROL: n = 32, M = 85.8 (SD = 3.2). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 32, M = 88.4 (SD = 4.0). No significant differences in the average Mini-CEX scores were found between the groups, p = 0.75. CONTROL: n = 32, M = 39.8 (SD = 5.2). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 32, M = 40.1 (SD = 4.1). |

2 (performance skills - other/DOPS) (skills knowledge - mini-CEX) | + Performance skills X No difference skills knowledge |

Mixed Positive |

| Chen & Liou | 2023 | AR | Nursing students – first aid | 95 nursing students | 1) Practice | Nursing students were divided into two groups for pediatric first-aid training. The control group performed simulation using a traditional Resusci Annie whereas the experimental group used an interactive Resusci Anne that was overlaid AR. Pre and post tests were given to evaluate participant knowledge and skills. Knowledge was assessed using a 20-question test. Skill level was assessed using a graded evaluation checklist. |

The AR intervention group showed significantly higher post-test knowledge, p < 0.001. CONTROL: n = 49, M = 18.08, (SD =1.6). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 46, M = 18.78, (SD = 1.1). The AR group also showed improved skill in first aid level scoring compared to the control group post-test, p < 0.001. CONTROL: n = 49, M = 29.71, (SD = 1.5). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 46, M = 32.52, (SD = 1.3) . |

2 (skills knowledge) (performance measures – other specific first aid) |

+ Skills knowledge + Performance measures |

Positive |

| Ekstrand et al | 2018 | VR + Print* | medical - neuroanatomy | 64 medical students | 1 (did nothing additional) | Medical students were assigned into either a control group who underwent paper-based neuroanatomy learning, or an experimental group who underwent neuroanatomy learning with VR. Pre and post-intervention tests were given, including a post-test immediately after the study completion and one 5-9 days later. | Both groups showed significant improvement between pre- and post-test scores, but no significant differences on the neuroanatomy test between the groups on either of the post-test results, p = 0.5. Means and SDs are not reported: T-statistic reported for control (n = 33) vs. VR (n = 31) post-training, t(62)= -0.38. | 1 (skills knowledge) | X No difference skills knowledge | No Difference |

| Fu et al | 2020 | VR | medical - suturing | 14 medical students | 1 (Practice) | Students were assigned to one of two training groups: (1) the VBLaST-SS (virtual simulator) training group or (2) the FLS training group. Students then watched a video that taught the intracorporal suturing task they were going to be practicing. Students then performed the task on both systems to measure baseline performance. Students then practiced once a day, five days a week, for three weeks. Performance scoring was based on the original FLS scoring system. | Both training modalities showed significant performance improvement, but there were no significant differences in the group x time interaction, p = 0.20. Learning curves for both learning modalities were also similar. Means and SD only shown in figure. | 1 (performance skills – specific FLS) | X No difference performance skills | No Difference |

| Haerling et al. | 2018 | VR | Nursing - case evaluation for COPD | 81 nursing students | 1 (Practice) | This study placed students in two groups, those using mannequin-based simulations and those using VR simulations. Participants completed a standardized patient encounter of a complex case involving a patient with COPD. Pre and post-intervention knowledge assessments were also performed using the LCJR and the C-SEI. | Students in both groups showed significant improvement in post-test knowledge assessment. Scores between the groups were not significantly different in the post-test knowledge assessment, p = 0.48. CONTROL: n = 14, M= 79.82 (SD = 17.63). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 14, M = 82.16 (SD = 11.76). There was no statistical difference post-intervention for either group for the LCJR, p = 0.374. CONTROL: n = 14, M = 82.69 (SD = 13.65). EXPERIMENTAL: n= 14, M = 78.18 (SD = 12.71). There was also no statistical difference post-intervention on the C-SEI between groups. CONTROL: n = 14, M = 84.62 (SD = 14.91). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 14, M = 81.93 (SD = 16.41). |

3 (skills knowledge) (clinical reasoning – LCJR) (clinical reasoning – C-SEI) |

X No difference skills knowledge X No difference clinical reasoning X No difference clinical reasoning |

No Difference |

| Han et al. | 2021 | VR + SP | medical - neurological | 95 medical students | 1 (did nothing additional) | Medical students were divided into two groups: a standardized patient (SP) group that was provided neurological findings using conventional methods (verbal description, pictures, videos) versus a SP with Virtual Reality-based Neurological Examination Teaching Tool (VRNET) group. A researcher measured student performance using the Neurologic Physical Exam (NPE) score. | The SP + VR group had significantly higher NPE scores compared to the SP group, p = 0.043. CONTROL: n = 39, M = 3.40 (SD = 1.01). EXPERIMENTAL n = 59, M = 3.81 (SD = 0.92). |

1 (skills knowledge - NPE score) | + Skills knowledge | Positive |

| Henssen et al. | 2019 | AR | medical & Biomedical- neuroanatomy | 31 medical and biomedical students | 1 (Print) | Students were assigned to one of two groups for learning neuroanatomy. The control group underwent learning with cross-sections of the brain whereas the experimental group underwent AR learning. | Results are assessed with respect to control. The control group showed improved post-test scoring compared to the AR, p = 0.035. Results for adapted test scores after training are reported next. CONTROL: n = 16, M =60.6 (SD = 12.4). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 15, M = 50.0 (SD = 10.2). |

1 (skills knowledge) | - Skills knowledge | Negative |

| Hu et al. | 2020 | VR + workshop in ultrasound* | medical - Ultrasound skills | 101 medical students | 1 (Print) | Medical students took place in an ultrasonography (US) training program. They were divided into either the virtual reality (VR) intervention group, or the control group. Both groups participated in an ultrasound workshop; however, the intervention group used a self-directed VR-enhanced anatomy review and used VR to complete additional review sessions during the US hands-on practice. After the US workshop was completed, participant competency was measured using a standardized practical US test, which focused on the identification of various anatomical structures, and a 10-Q MCQ on anatomy. | Participants in the intervention group showed significantly higher scores on US task performance overall, p < 0.01. Results below are for mean rank. No variability given. CONTROL: n = 54, MR = 38.52. EXPERIMENTAL: n = 47, MR = 65.34. The VR group also showed significantly better scores on the knowledge test, p < .05. CONTROL: n = 54, median = 2 (IQR = 3). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 47, Median = 3 (IQR = 3). |

2 (skills knowledge) (performance skills - other practical US) |

+ Skills knowledge + Performance skills |

Positive |

| Issleib et al. | 2021 | VR | medical - CPR | 160 medical students | 1 (Practice) | Medical students were randomized into an intervention or control group. The intervention group completed a the BLS course in virtual reality, whereas the control group underwent standard BLS training. At the end of training, all students performed a 3-minute practical test using the Leardal Mannequin to record no flow time on the task. | The control group had significantly shorter no flow time compared to the VR, p < 0.0001. CONTROL: n = 104, M = 82.03 (SD = not reported). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 56, M = 92.96 (SD = not reported). |

1 (performance skills - specific no flow time) | - Performance skills |

Negative |

| Jaskiewicz et al. | 2020 | VR + Practice* | medical - CPR | 91 medical students | 1 (Teacher) | Both the control and experimental groups completed a 3-hour BLS course including background training and practice on a CPR mannequin. Students then participated in either a tadeonal teaching or VR scenario where hands-only CPR was completed. The quality of the chest compressions (rate and depth) was then tested and analyzed. | There were no significant differences in chest rate compression performance between the control and virtual reality groups, p = 0.48. CONTROL: n = 45, Median = 114 (IQR 108-122). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 45, Median = 115 (IQR 108-122). There was also no significant difference on chest rate depth between groups, p > 0.05. CONTROL: n = 45, Median = 48 (IQR = 44-55). EXPERIMENAL: n = 45, Median = 49 (IQR = 43-53). Finally, there was a significant increase in the percentage of chest compression relaxation for the control group compared to the VR group, p < 0.01. CONTROL: n = 45, Median = 97 (IQR = 85-100). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 45, Median = 69 (IQR = 26-98). |

3 (performance skills - specific rate) (performance skills - specific depth) (performance skills – specific relaxation) |

X No difference performance skills X No difference performance skills -Performance skills |

Mixed Negative |

| Jung & Park | 2022 | VR | Nursing students – chemport insertion surgery | 60 nursing students | 1 (Print) | Nursing students were divided into two groups to learn chemoport insertion surgery. The control group's learning consisted of instruction by an operating nursing instructor, learning via a handout, and time for self-study. The experimental group used VR. Pre and post-test knowledge was assessed using a 10-point questionnaire about key knowledge of insertion. |

The VR group showed significantly higher post-test knowledge scores compared to the control group after training, p = 0.001. CONTROL: n = 30, M = 4.80 (SD = 1.65). EXPERIMETNAL: n = 30, M = 6.97 (SD = 1.35). |

1 (skills knowledge) | + Skills knowledge | Positive |

| Kane et al. | 2022 | VR | med students- obstetrics | 69 medical students | 1 (Electronic) | Medical students were placed into one of two groups to help them learn and conceptualize fetal lie and presentation. The interventional group was immersed in a virtual reality learning environment (VRLE) to explore fetal lie, and the control group used traditional 2D images. After their sessions, clinical exam skills were tested using an obstetric abdominal model. Knowledge was assessed by students' ability to determine fetal lie and presentation on this model. Time taken to complete the test was also measured. | No significant differences were found between the two groups in terms of knowledge assessment, although the authors note that there was a noticeable trend of higher success rates in the intervention group in the VR group compared to the control group) for combined lie and presentation scores, p = not reported. CONTROL: n =34, M = 70.0 (SD = not reported). EXPERIMENTAL : n = 33), M = 56% (SD = not reported). However, time to complete the task was significantly less in the intervention group compared to the control group, p = 0.012. CONTROL: n = 34, M = 38 (SD = 10.83). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 33, M = 45 (SD = 12.95). |

2 (performance skills - time) (performance skills -specific success) | X No Difference performance skills + Positive performance skills |

Mixed Positive |

| Kowalewski et al | 2019 | VR | medical - surgery | 100 medical students | 1 (Did nothing) | Medical students were divided into three groups to complete laparoscopic training: (1) the control group, which received no training, (2) the "alone" group, and (3) the dyad group. Intervention groups completed box and VR training, after which performance was measured with a cadaveric porcine laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC), and the objective structured assessment of technical skills (OSATS) was used. Global operative assessment of laparoscopic skills (GOALS), time to completed LC, and VR performances were also measured. | Results are reported for improvement between the VR and control group only. The VR group and the control group did not differ on the OSATS, p = 0.548. CONTROL: n = 20, M = 37.1 (SD = 7.4). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 40, M = 40.2 (SD = 9.8). The two groups did not differ on the GOALS either, p = 0.998. CONTROL: n = 20, M = 10.1 (SD = 3.0). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 40, M = 10.6 (SD = 3.0). The VR groups were faster than the control group in completion time, p < 0.001. CONTROL: n = 20, M = 13.5 [11.8, 17.5]. EXPERIMENTAL: n = 40, M = 10.2 [7.9, 11.3]. The VR group also had fewer movements, p = 0.002. CONTROL: n = 20, M = 871 [637, 1105]. EXPERIMENTAL: n = 40, M = 683 [468, 898]. The VR group also had a shorter path length, p = 0.004. CONTROL: n = 20, M = 1640 [1174, 2106]. EXPERIMENTAL: n = 40, M = 1316 [948, 1684]. |

5 (performance measures -OSATS) (performance measures - GOALS) (performance skills - time) (performance skills- other specific path) (performance skills- other specific length) | X No difference performance measures X No difference performance measures + Performance skills + Performance skills + Performance skills |

Mixed Positive |

| Küçük et al | 2016 | AR | medical -anatomy | 70 medical students | 1 (Print) | Medical students were placed into a control group, which used traditional teaching methods (textbook) or an experimental group, which used mobile augmented reality (mAR) technology (MagicBook) to learn neuroanatomy. Post-intervention knowledge was measured using an Academic Achievement Test (AAT), a 30-question multiple-choice test. | The experimental mAR group showed significantly superior performance on the AAT test, p < 0.05. CONTROL: n = 34, M = 68.34 (SD = 12.83). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 36, M = 78.14 (SD = 16.19). |

1 (performance measures - AAT) | + Performance measures | Positive |

| Lau et al | 2023 | VR | Nursing students | 34 nursingstudents | 1) Nothing (pre-post) | Nursing students participated in pre-test and post-test knowledge questionnaires regarding both subcutaneous insulin injection and intravenous therapy. After completing the pre-test, participants underwent learning using immersive VR before completing the post-test questionnaire. | There was a significant improvement in knowledge test scores (IV and subcutaneous injection) after training, p = 0.075. Only z-scores were reported with ranks. No M or SDs are reported pre vs. post. |

1 (skills knowledge) | + Skills knowledge | Positive |

| Lemke et al | 2020 | AR | medical - suturing | 44 medical students | 2 (Teacher) (Combined) | Students were randomized into one of three intervention groups to learn suturing skills: (1) faculty-led, (2) peer tutor-led, or (3) holography-augmented intervention arms (Suture Tutor). Outcomes measured include: the number of simple interrupted sutures that were placed to achieve proficiency, the total number of full-length sutures used, and time to achieve proficiency. | Results are reported among three groups. No significant differences among the intervention groups in the number of full-length sutures used, p = .376. Means and SD are reported for Teacher control vs. AR CONTROL: N = 16, M = 80.0 (SD = 47.2). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 14, M = 107.4 (SD = 61.3). No significant differences among the intervention groups in the number of simple interrupted sutures placed, p = 0.735. CONTROL: n = 16, M = 9.3 (SD = 5.3). EXPERIMETNAL: n = 14, M = 11.0 (SD = 6.0). No significant differences among the intervention groups in the time to achieve proficiency, p = 0.390. CONTROL: n = 16, M = 158.1 (SD = 89.2). EXPERIMETNAL: n = 14, M = 205.0 (SD = 113.2). |

3 (performance skills – other specific # placed) (performance skills – other specific interruptions) (performance skills – other specific # used) |

X No difference performance skills X No difference performance skills X No difference performance skills |

No Difference |

| Logishetty et al. | 2019 | AR | Medical - surgery | 24 medical students | 1 (Practice) | This study simulated total hip arthroplasty (THA) and placed students in one of two groups to determine what training is more effective at improving the accuracy of acetabular component positioning: (1) augmented reality (AR) training (with live holographic orientation feedback) or (2) hands-on training with a hip arthroplasty surgeon. Students participated in one baseline assessment, training session, and reassessment a week for four weeks and were recorded on the target angle (inclination – anteversion). | AR intervention group showed smaller average errors than the control practice with surgeon group after training, p < 0.0001. CONTROL: n = 12, M = 6 (SD = 4). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 12, M = 1 (SD = 1). In the final session, both groups showed improvement on the target angle, but there was no significant difference in performance between groups, p = 0.281. Means and SD are reported as differences from pre. CONTROL: n = 12 , MD = -8.4 [-7.0, -9.8]. EXPERIMENTAL: n = 12, MD = -7.8 [-5.5, -10.2]. |

2 (performance skills - errors) (performance skills – other specific target angle) | + Performance skills X No difference Performance skills |

Mixed Positive |

| Maresky et al. | 2018 | VR immersive + VR simulation* | medical - anatomy | 42 medical students | 1 (Print) | Before learning cardiac anatomy, medical students underwent a VR simulation of the subject. Students then were separated into either a control group that continued independent anatomy study, or an experimental group that underwent an immersive VR experience. Pre and post-test scores were obtained, which measured both conventional and visual-spatial (VS) cardiac anatomy questions. | Students in the immersive VR intervention group scored significantly higher overall after the intervention, p < 0.001. Mean differences between control (n = 14) and experimental group (n = 28) are only reported: MD = 24.8 (SD = 3.89). This included both subsections of VS and conventional content. |

1 (skills knowledge) | + Skills knowledge | Positive |

| Moll- Khosrawi et al. | 2022 | VR | medical - BLS | 88 medical students | 1 (Electronic) | Medical students were placed into one of two groups to compare a control group that received web-based basic life support (BLS) training to an intervention group that underwent additional individual virtual reality (VR) training. The quality of BLS skills was assessed after training with a no-flow-time indicator. Overall BLS performance was also assessed using an adapted observational checklist, graded by experts. | The VR intervention group showed significantly lower no-flow-time compared to the control, p = 0.009. CONTROL: n = 42, M = 11.05 (SD = 10.765). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 46, M = 6.46 (SD = 3.49). The VR group also showed significantly superior overall (lower penalty point) for their BLS performance in comparison to the control group, p < 0.001. CONTROL: n = 42, M = 29.19 (SD = 16.31). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 46, M = 13.75 (SD = 9.66). |

2 (performance skills – other specific flow time) (performance measures - checklist) | + Performance skills + Performance measures |

Positive |

| Moro et al | 2017 | AR /VR | medical- anatomy | 59 medical and health science students | 1 (Electronic) | Medical students completed a lesson on skull anatomy using one of three learning modalities: (1) virtual reality (VR), (2) augmented reality (AR), or (3) tablet-based (TB). After their 10-minute anatomy lesson using their respective learning modality, students completed a 20-question multiple-choice anatomy test to measure their knowledge. | No significant differences in the anatomy test scores were found between the three groups; AR and VR intervention did not show superior knowledge acquisition in comparison to table-based skull anatomy learning after intervention, p = 0.874. Means are for VR group and control group only. Standard deviations are depicted only in figure. CONTROL: n = 22, M = 61. EXPERIMETNAL: n = 20 , M = 59. |

1 (skills knowledge) | X No difference skills knowledge | No Difference |

| Nagayo et al | 2022 | AR | medical - surgery | 38 medical students | 1 (Electronic) | Medical students were randomized into one of two groups for self-training suturing learning: (1) the augmented reality (AR) training group or (2) the instructional video group. Both groups watched an instructional video on subcuticular interrupted suturing and took a pretest. They then practiced the suture 10 times using their assigned learning modality, before completing a post-test. Pre- and post-tests were performed on a skin pad and were graded using global rating and task-specific subscales. | Both groups showed significant improvement between pretest and posttest scores in both global rating and task-specific subscales on suturing performance; however, no significant difference in performance was found between the AR and instruction video training groups using the global rating, p = 0.38. CONTROL: n =19 , M = 15.11 (SD = 2.84). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 19, M 15.03 (SD = 1.94). |

1 (performance skills – other specific suturing performance) | + Performance skills | Positive |

| Neumann et al | 2019 | VR | medical - surgery | 51 medical students | 1 (Electronic) | Medical students were randomized into two groups for cystoscopy (UC) and transurethral bladder tumor resection (TURBT) training. The control group watched video tutorials by an expert. After completion of the training, students performed a VR-UC and VR-TURBT performance task and 12 measures of performance were recorded. | Both groups improved on three variables after training, including significantly lower average procedure length, lower resectoscope movement, and accidental bladder injury, but there was only one significant difference in the improved performances for the VR compared to the control (procedure time, p = 0.04). All Means and SD listed in Table 2. | 12 (performance skills – other specific x 9) (performance skills - injury) (performance skills - time x 2) | X No difference performance skills (for 11 of the 12 variables) + Performance skills |

No Difference |

| Nielsen et al. | 2021 | VR | medical - Ultrasound skills | 20 medical students | 1 (Electronic) | Medical students were randomized into either a virtual reality (VR) or e-learning group for ultrasound education and training. Performance was scored using the OSAUS. | The VR group showed significantly higher scoring on the OSAUS compared to the e-learning group after intervention, p ≤ 0.001. CONTROL: n = 9, M = 125.7 (SD = 16.2). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 11, M = 142.6 (SD = 11.8) . |

1 (performance measures - OSAUS) | + Performance measures | Positive |

| Noll et al | 2017 | AR | medical - dermatology | 44 medical students | 1 (Print) | Medical students were randomized into one of two groups for learning dermatological knowledge. Group A's training involved the use of a mobile Augmented Reality (mAR) application, whereas Group B's training involved textbook-based learning. Baseline and post-test knowledge were assessed using a 10-question single choice (SC) test, which was repeated after 14 days to assess longer-term retention. | The initial SC post-test showed significant knowledge gain in both groups, but the VR group showed a marginally significant memory for correct answers after two weeks, compared to the control group, p = 0.10. CONTROL: n = 22, M = 0.33 (SD = 1.62). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 22, M = 1.14 (SD = 1.30). |

1 (skills knowledge) | + (marginal) Skills knowledge | Positive |

| Orland et al. | 2020 | VR+ | Medical - surgery | 25 medical students | 1 (Print) | Medical students were randomized into one of three groups for learning intramedullary tibial nail insertion: (1) the technique guide only control group, (2) the virtual reality (VR) only group, or (3) the VR plus technique guide group. The experimental groups participated in three separate VR simulations, 3-4 days apart. After 10-14 days of preparation, students performed an intramedullary tibial nail insertion simulation into a bone-model tibia. Completion and accuracy were assessed. | Overall assessments are made with comparisons to both VR groups compared to control group. Both experimental groups that involved VR training showed higher completion rates, p = .01 Both groups also had fewer incorrect steps, p = .02, in comparison to the control group. Means and SD below are for VR+ and control group only. ERRORS CONTROL: n = 8, M = 5.7 (SD = 0.2). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 9, M = 3.1 (SD = 0.1). COMPLETION TIME CONTROL: n = 8, M = 24 (SD = 4). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 9, M = 18 (SD = 8). |

2 (performance skills - errors) (performance skills - time) | + Performance skills + Performance skills |

Positive |

| Plotzky et al. | 2023 | VR 'high' | Nursing students- endotracheal suctioning skills | 131 nursing students | 2 (low VR) + Electronic | Nursing students were split into one of three groups for learning of endotracheal suctioning skills. The control group's intervention was a video tutorial. The intervention groups consisted of a VR low group and a VR high group. The VR 'low' group's intervention consisted of basic VR technology, including head tracking and controller-based controls. The VR 'high' group's intervention consisted of more advanced VR technology, including head and hand tracking, allowing users to interact with their actual hands, and as well as supplementing with real-world video clips. Participants were assessed using a knowledge test and a skill demonstration test on a manikin using an objective structured clinical examination (OSCE). The knowledge test was given immediately after intervention and 3 weeks later. |

Each of three groups showed a significant increase in knowledge acquisition, however, there was no significant difference among them for skills knowledge, p = 0.730. Means and SDs are for the VR+ vs. control group after intervention. CONTROL: n = 43, M = 7.16 (SD = 2.29). EXPERIMENTAL: n =47, M= 7.06 (SD = 1.42). There was a significant difference among groups on the OSCE after intervention, p < 0.001. Means and SDs are for the VR+ vs. control group after intervention. CONTROL: n = 43, M = 11.95 (SD = 1.65). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 47, M= 9.41 (SD = 2.70). |

2 (skills knowledge) (performance measures –OSCE) | X No difference skills knowledge - Performance measures |

Mixed Negative |

| Price et al. | 2018 | VR | nursing - triage skills | 67 nursing students | 1 (Practice) | This study compared the use of VR to clinical simulation to determine the efficiency in executing the START (Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment) triage. | There were no significant differences between the VR and clinical simulation group in the percentage of victims that were correctly triaged, p = 0.612 CONTROL: n = 35, M = 88.3 (SD = 9.65). EXPERIMENTAL: n =32, M = 87.2 (SD = 7.2). |

1 (performance skills - specific triage variables) | + Performance skills | Positive |

| Ros et al. | 2020 | VR + Print | medical -surgery | 176 medical students | 1 (Did nothing additional) | All students were given a technical note detailing an external ventricular drainage (neurosurgical) technique. Students were randomized into two groups, one of which received no additional training, and one which used immersive virtual reality (VR) as supplemental teaching. Knowledge was assessed with a multiple-choice test immediately after training and six months after. | VR training showed significantly superior knowledge gain, after both initial assessment and at the six-month mark, p = 0.01. Means and SD are reported after the initial training. CONTROL: n = 88, M = 4.59, (SD = 1.4). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 85, M = 5.17 (SD = 1.29). |

1 (skills knowledge) | + Skills knowledge | Positive |

| Ros et al. | 2021 | VR | Medical- lumbar puncture | 89 medical students | 1 (Teacher) | Medical students were randomized into one of two groups to complete training in how to perform a lumbar puncture. The control group participated in traditional lecture learning whereas Group 2 participated in immersive VR 3D video filmed from first-person point of view (IVRA-FPV). After training, students performed a simulated lumbar puncture on a mannequin to analyze their applied learning skillset. An oral examination was also included as an assessment. | The group that participated in the traditional lecture showed significantly superior scoring n oral examination, p < 0.001. CONTROL: n = 45, M = 4.06, SE = 0.12. EXPERIMENTAL: n = 44, M = 4.97, SE = 0.10. The VR group took more time to perform the simulated lumbar puncture compared to the control, p < 0.01. CONTROL: n = 55, M = 73, SE = not reported. EXPERIMENTAL: n = 36, M = 50, SE = not reported. The VR group also had reduced errors compared to the control, p < 0.01. Means are reported as latency of errors. CONTROL: n = 44, M = 153.26, SE = 11.19. EXPERIMENTAL: n = 43, M = 227.50, SE = 34.34. |

3 (skills knowledge) (performance skills - time) (performance skills - errors) | - Skills knowledge + Performance skills + Performance skills |

Mixed Positive |

| Schoeb et al | 2020 | MR + Practice | medical - catheter placement | 164 medical students | 1 (Did nothing additional) | Medical students were randomized into one of two groups to undergo bladder catheter placement learning. One group underwent learning with an instructor, while the other group received mixed reality (MR) training using a Microsoft HoloLens. Both groups were able to participate in hands-on training before undergoing a standardized objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) for performance assessment. | The MR intervention group showed significantly superior bladder catheter placement simulation in comparison to the control group, p = 0.000. CONTROL: n = 107, M = 19.96, (SD = 2.42). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 57, M = 21.49, (SD = 2.27) |

1 (performance measures - OSCE) | + Performance measures |

Positive |

| Shao et al. | 2020 | VR | Medical - anatomy | 30 medical students | 1 (Combined) | Students were divided into either a traditional teaching group, or a virtual reality (VR) teaching group for teaching skull base tumors and skull anatomy. The traditional teaching group used literature-based learning, problem-based teaching, and case-based teaching, whereas the VR groups used real case images and Hololens (VR) glasses. After completion of their intervention. | VR group had higher total scoring on the basic knowledge assessment compared to the traditional control group, p < 0.001. CONTROL: n =15, M = 63.6 (SD = 3.81). EXPERIMENTAL: n =15, M = 77.07 (SD = 4.00). |

1 (skills knowledge) | + Skills knowledge | Positive |

| Smith et al. | 2018 | VR immersive or VR computer | nursing - decontamination skills | 172 nursing students | 1 (Print) | Nursing students were divided into 3 groups for decontamination skills training. The control group used a traditional written instructions learning method, whereas the experimental groups underwent immersive VR or computer-based VR training. Post-learning competency was measured using a Decontamination checklist in which students performed skills on a mannequin. Cognitive test scores, performance scores, and time to complete skills were measured immediately post-training and 6 months later. | Results are reported for the immediate follow-up post intervention. There were no significant differences among groups for the cognitive scores, p = 0.568. Means and SD are shown both VR groups combined and the traditional control group only. CONTROL: n = 43, M = 19 [8, 23]. EXPERIMENTAL: n = 43, M = 19 [13, 23]. There was no difference among the groups for time to completion on the OSCE, p = 0.723. Means and SD are shown both VR groups combined and the traditional control group only. CONTROL: n = 43, M = 260 [180, 360] EXPERIMENTAL: n = 43, M = 260 [180, 360]. The computer/mouse VR groups showed superior performance measures compared to the control group on the immediate post-test, p = 0.017. Means and SD are shown both VR groups combined and the traditional control group only. CONTROL: n = 43, M = 54 [46, 57]. EXPERIMENTAL: n = 43, M = 55 [46, 57]. |

3 (skills knowledge) (performance skills - time) (performance skills -other specific decontainment mannikin) | X No difference skills knowledge X No difference performance skills - Performance skills |

Mixed Negative |

| Stepan et al. | 2017 | VR | medical - neuroanatomy | 66 medical students | 1 (Electronic) | Medical students were assigned to either a control (online textbook) or an experimental (3D imaging VR interactive model) group for the learning of neuroanatomy. | Students completed preintervention, postintervention, and retention tests for assessment of knowledge. No significant differences in anatomy knowledge assessments were found between the control and VR groups, p = 0.87. CONTROL: n= 33, M = 0.76 (SD = 0.14) EXPERIMENTAL: n = 33, M = 75 (SD = 0.16) |

1 (skills knowledge) | X No difference skills knowledge | No difference |

| Sultan et al. | 2019 | VR | Medical - tube placement | 169 medical students | 1 (Practice) | Medical students were split into two groups to participate in a learning workshop regarding communication and collaboration. The workshop was a half-day, once a week, for 6 months. VR group received VR instruction, whereas the control group received conventional learning (simulated patients, lectures). Post-intervention assessment included an MCQs score and an Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCE) score. | The VR intervention groups showed significantly higher MCQs compared to the control group after training, p < 0.001. CONTROL: n = 112, M = 15.9, (SD = 2.9). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 57, M = 17.4, (SD = 2.1) . The VR group also showed improved OSCE after training compared to the conventional learning group, p < 0.001. CONTROL: n = 112, M = 9.8, (SD = 4.2). EXPERIMENTAL: n =57, M = 12.9, (SD = 4.1). |

2 (skills knowledge) (performance measures-OSCE) | + Skills knowledge + Performance measures |

Positive |

| Watari et al. | 2020 | VR | medical students - basic clinical knowledge | 210 medical students | 1 Nothing (pre-post) | Medical students participated in a lecture that used Virtual Patient Simulations (VPSs). Pre- and post-test 20 item multiple-choice questionnaires were taken and involved both knowledge and clinical reasoning items. | Students showed a significant increase in post-test scoring on both knowledge, p = 0.003. EXPERIMENTALpre: n = 169, M = 4.78, [4.55, 5.01].EXPERIMENTALpost: n = 169, 5.12, [4.90, 5.43]. Students also had increased clinical reasoning after training, p < 0.001. EXPERIMENTALpre: n = 169 , M = 5.3, [4.98, 5.58]EXPERIMENTALpost: n =169, M = 7.81, [7.57, 8.05]. |

2 (skills knowledge) (clinical reasoning) |

+ Skills knowledge + Clinical reasoning |

Positive |

| Wolf et al | 2021 | AR | Medical - surgery | 21 medical students | 1 (Print) | Medical students were recruited for training in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) cannulation. They were split into two groups: (1) conventional training instructions for the first procedure, and AR instructions for the second; (2) reverse order (AR instructions for the first procedure). Participants performed the two ECMO cannulation procedures on a simulator. Training times and a detailed error protocol were used for assessment. | AR group showed minimally higher training times compared to the control group, no p values given. Means and SD in figures only. AR group had significantly less errors when performing the second (more complex) simulation procedure, no p values given. Means and SD in figures only. |

2 (performance skills - error) (performance skills – time) |

+ Performance skills -Performance skills |

Mixed |

| Yang & Oh | 2022 | VR | nursing - infant respiration | 83 nursing students | 2 (Teacher) (Practice) | Nursing students were separated into three groups to undergo neonatal resuscitation training. These groups included: a virtual reality group, high-fidelity simulation group, and a control (online lectures only) group. Pre and post-test scores were analyzed on neonatal resuscitation knowledge, problem-solving ability, and clinical reasoning ability. | Knowledge scores increased for all groups post-intervention, but the VR and simulation group showed significantly higher knowledge after intervention compared to the control group, p = 0.004. Means and SDs are reported for the VR and control groups only. CONTROL: n = 26, M =11.85, (SD = 5.43). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 29, M = 18.00, (SD = 2.55). The VR group showed significantly improved problem-solving ability scores in comparison to both the simulation and control groups, p = 0.038. CONTROL: n = 26, M = 106.24, (SD = 24.52). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 29, M = 122.72, (SD = 15.68). Clinical reasoning ability showed significant improved performance, but the none of the groups differed statistically, p = 0.123. CONTROL: n = 26, M = 53.69, (SD = 12.02). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 29, M = 59.66, (SD = 9.44). |

3 (skills knowledge – other specific resuscitation) (problem solving) (clinical reasoning) |

+ Skills knowledge + Problem solving X No difference clinical reasoning |

Mixed Positive |

| Yeo et al. | 2018 | AR + Ultrasound | medical- lumbar puncture and facet joint injection | 36 medical students | 1 (Practice) | Medical students were randomized into either a control group (ultrasound use only), or an experimental group that involved training with ultrasound and AR using Perk Tutor software. Training involved learning lumbar puncture and facet joint injection skills on five different tasks for two tasks, a simpler and hard one (ultrasound-guided facet joint injection). | Results are reported for the harder task, only. The AR group had more successful injections p = 0.04. CONTROL: n = 10, M = 37.5, SD = not reported. EXPERIMETNAL: n = 10, M = 62.5, SD = not reported. AR was also better than control post-training for total time, p < 0.001. CONTROL: n = 10, M = 103, (SD = 13). EXPERIMETNAL: n = 10, M = 47, (SD =3). AR was also better than control post-training for time inside the phantom body, p < 0.01. CONTROL: n = 10, M = 31, (SD = 5). EXPERIMETNAL: n = 10, M = 14, (SD = 2). AR was also better than control post-training for path distance inside the phantom body, p < 0.01. CONTROL: n = 10, M = 266, (SD = 76). EXPERIMETNAL: n = 182, M = 47, (SD =36). AR was also better than control post-training for potential tissue damage, p = 0.03. CONTROL: n = 10, M = 3217, (SD = 1173). EXPERIMETNAL: n = 10, M = 2376, (SD = 673). |

5 (performance skills - time) (performance skills – other specific time inside) (performance skills - other specific path) (performance skills – other specific damage) (performance skills - other specific success) | + Performance skills – + Performance skills + Performance skills + Performance skills + Performance skills |

Positive |

| Yu et al | 2022 | VR + Practice (BOX)* | Medical - surgery | 51 medical students | 1 Nothing (pre-post) | Medical students completed four pre and post experiments with a box trainer based laparoscopic surgery simulators (VRLS). Students were assessed by expert surgeons using the Global operative assessment of laparoscopic skills (GOALS) standards on performance and time on two tasks, fundamental task (FT) and the color resection task (CRT) | Post-test assessments showed a significantly faster task completion post training on both tasks, p < 0.01. Means and SDs are shown pre and post for one task (FT). EXPERIMENTALpre: n = 51, M =21.95, SD = not reported. EXPERIMETNALpost: n = 51, M = 14.04, SD = not reported. Post-training also had improved performance on the GOALS (heart rate) for both tasks, p < 0.05. Means and SDs are shown pre and post for one task (FT). EXPERIMENTALpre: n = 51, M = 94.96, (SD = 11.14). EXPERIMENTALpost: n = 51, M = 92.71, (SD = 11.67). |

2 (performance measures -GOALS) (performance skills - time) |

+ Performance skills + Performance measures - |

Positive |

| Zackoff et al. | 2020 | VR + Teacher + Practice | Med students- infant respiratory distress | 168 medical students | 1 (Teacher) | Medical students completed standard respiratory distress training using traditional didactic material, as well as a mannequin simulation. A randomized group of students also completed an additional 30-minute training using immersive virtual reality with various infant simulations (no distress, respiratory distress, and impending respiratory failure). After training, all students completed a free-response test regarding various video questions including mental status, breathing, breadth sounds, and vital signs for three different cases, no distress, respiratory distress, and respiratory failure. In addition, the need for escalation of care was assessed in each case. | Students who underwent additional VR intervention showed significantly superior status interpretation across all assessed dimensions and all cases, p < 0.01. Means and SDs for one case are shown (no distress). CONTROL: n = 90, M = 104 (SD = 61.2). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 78, M = 124 (SD = 80). The additional VR status groups also had a higher recognition for the need for increased care, p = 0.0004. Means and SDs for one case are shown (respiratory failure). CONTROL: n = 90, M = 41, (SD = 45.6). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 78, M = 56, (SD = 72.7). |

2 (skills knowledge- respiratory) (skills knowledge - level of care) | + Skills knowledge + Skills knowledge |

Positive |

| Zhou et al. | 2022 | AR | Nursing - stroke | 36 nursing students | 1 (Practice) | Nursing students were divided into two groups: a mannequin-based simulation only (control) or a mannequin-based simulation with AR. They were assessed for clinical judgment with the LCJR. | The AR group spent less time than the control group in the critical phase of the stroke simulation, p < 0.05. CONTROL: n = 18, M = 99.57, (SD = 79.00). EXPERIMENTAL: n = 18, M = 46.61, (SD = 27.92). AR outperformed the control group on the LCJR for one of three sections (noticing), p < 0.05. Means and SDs are only shown in figure. |

2 (performance skills - time) (clinical reasoning - LCJR) | + Performance skills + Clinical Reasoning |

Positive |

| Author, Date | Learning Theory Mentioned | MERSQI + NOS-E score (max 24) | QUADAS score (max 11) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aebersold et al., 2018 | Situated learning theory | 22 | 10 |

| Andersen et al., 2021 | No | 21.5 | 11 |

| Andersen et al., 2022 | No | 21.5 | 9 |

| Arents et al., 2021 | Cognitive load | 15.5 | 6 |

| Azimi et al., 2018 | No | 12.5 | 4 |

| Banaszek et al., 2017 | No | 21 | 10 |

| Bayram & Caliskan, 2019 | NLN/Jeffries Simulation Theory | 17.5 | 7 |

| Blumstein et al., 2020 | No | 21 | 8 |

| Bogomolova et al., 2020 | Constructive Alignment Theory & Blooms | 21 | 8 |

| Bork et al., 2019 | No | 13.5 | 7 |

| Brinkmann et al., 2017 | No | 17.5 | 8 |

| Bube et al., 2020 | Directed self-regulated learning (DSRL) theory; Simulation-based mastery learning | 19 | 8 |

| Butt et al., 2018 | Deliberate practice theory | 19.5 | 9 |

| Cevallos et al., 2022 | No | 20 | 8 |

| Chao et al., 2021 | No | 17.5 | 8 |

| Chao et al., 2023 | Cognitive load theory | 21.5 | 8 |

| Chen & Liou, 2023 | No | 19 | 7 |

| Ekstrand et al., 2018 | No | 16.5 | 9 |

| Fu et al., 2020 | No | 16.5 | 9 |

| Haerling, 2018 | NLN/Jeffries Simulation Theory | 16.5 | 9 |

| Han et al., 2021 | No | 16 | 7 |

| Henssen et al., 2019 | Cognitive load theory; Blooms | 14.5 | 8 |

| Hu et al., 2020 | No | 19 | 7 |

| Issleib et al., 2021 | No | 20 | 3 |

| Jaskiewicz et al., 2020 | No | 15 | 3 |

| Jung & Park, 2023 | No | 16.5 | 9 |

| Kane et al., 2022 | No | 21 | 5 |

| Kowalewski et al., 2019 | No | 21 | 7 |

| Küçük et al., 2016 | Cognitive load theory | 18.5 | 9 |

| Lau et al., 2023 | No | 14 | 10 |

| Lemke et al., 2020 | No | 18.5 | 10 |

| Logishetty et al., 2018 | No | 20.5 | 9 |

| Maresky et al., 2018 | No | 17 | 3 |

| Moll- Khosrawi et al., 2022 | No | 20 | 8 |

| Moro et al., 2017 | Cognitive load theory | 17.5 | 3 |

| Nagayo et al., 2022 | No | 21 | 6 |

| Neumann et al., 2019 | No | 21 | 4 |

| Nielsen et al., 2021 | No | 19.5 | 8 |

| Noll et al., 2017 | No | 20.5 | 9 |

| Orland et al., 2020 | No | 21 | 4 |

| Plotzky et al., 2023 | No | 21 | 8 |

| Price et al., 2018 | No | 17 | 2 |

| Ros et al., 2020 | No | 17.5 | 3 |

| Ros et al., 2021 | Kolb | 20.5 | 4 |

| Schoeb et al., 2020 | No | 20.5 | 10 |

| Shao et al., 2020 | No | 19.5 | 3 |

| Smith et al., 2018 | No | 19 | 9 |

| Stepan et al., 2017 | No | 20.5 | 7 |

| Sultan et al., 2019 | Experiential learning theory | 19.5 | 8 |

| Watari et al., 2020 | No | 16 | 7 |

| Wolf et al,. 2021 | No | 15.5 | 7 |

| Yang & Oh, 2022 | No | 19 | 7 |

| Yeo et al., 2018 | No | 19 | 6 |

| Yu et al,. 2022 | Cognitive load theory | 18 | 6 |

| Zackoff et al., 2020 | No | 17.5 | 9 |

| Zhou et al., 2022 | No | 19 | 9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).