1. Introduction

Genetic hearing loss is a common congenital disease with a prevalence of 1/1000 in humans [

1,

2]. Approximately 70-80% of genetic hearing loss is non-syndromic and shows autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, X-linked, or mitochondrial inheritance [

1,

2]. The genetic variants of more than 80 genes are known to be associated with non-syndromic hearing loss. The most frequently mutated genes include:

GJB2, SLC26A4, MYO15A, OTOF, TMC1, CDH23 and

GJB6. With respect to autosomal dominant non-syndromic hearing loss (ADNSHL), hearing loss may occur at an advanced age and present in variable ways and severity. Its genetic background is very heterogenic with 44 disease-causing genes found to be associated with its development thus far (

http://hereditaryhearingloss.org/) [

3,

4]. Despite the high number of previously identified genes, a large portion of ADNSHL has not been genetically defined, which is a significant issue for this disease [

4].

Among these 44 genes, there is the recently reported disease-causing gene, transformation/transcription domain associated protein

(TRRAP) [

5]. The encoded TRRAP protein is an evolutionary conserved member of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase-related kinases (PIKK) family [

6,

7]. TRRAP is a component of many histone acetyltransferase (HAT) complexes, plays a role in transcription and DNA repair by recruiting HAT complexes to chromatin [

8,

9]. TRRAP also has a significant role in hearing development. In trrap knockdown and knockout zebrafish reduced lateral line neuromasts, decreased number of hair cells per neuromast and abnormal stereocilia on the hair cells were observed compared with WT zebrafish [

5].

In humans, two rare diseases with autosomal dominant inheritance have been associated with

TRRAP: the ADNSHL (OMIM 618778) and the developmental delay with or without dysmorphic facies and autism (OMIM 618454). With respect to ADNSHL, only four disease-causing

TRRAP variants – three missense (NM_001244580.2, p.Arg171Cys, p.Asp394Asn, and p.Glu2750Asp) and one frameshift (p.Pro509fs) – have been linked with the disease [

5]. Nearly all previously reported variants affect the same functional domain of the TRRAP protein, including the p.Arg171Cys, p.Asp394Asn and p.Pro509fs variants, which all affect the Tra1 HEAT repeat central region domain (position from 18 to 531 amino acids), whereas the p.Glu2750Asp variant does not affect any known functional domains of the protein [

5].

Here, we report on a Hungarian ADNSHL family, in which the affected individuals show hearing loss with very similar unique clinical characteristics. Whole exome sequencing (WES) was performed and the shared genetic variants of the affected individuals were assessed to establish the genetic background of their hearing loss.

2. Results

2.1. Audiological Investigations

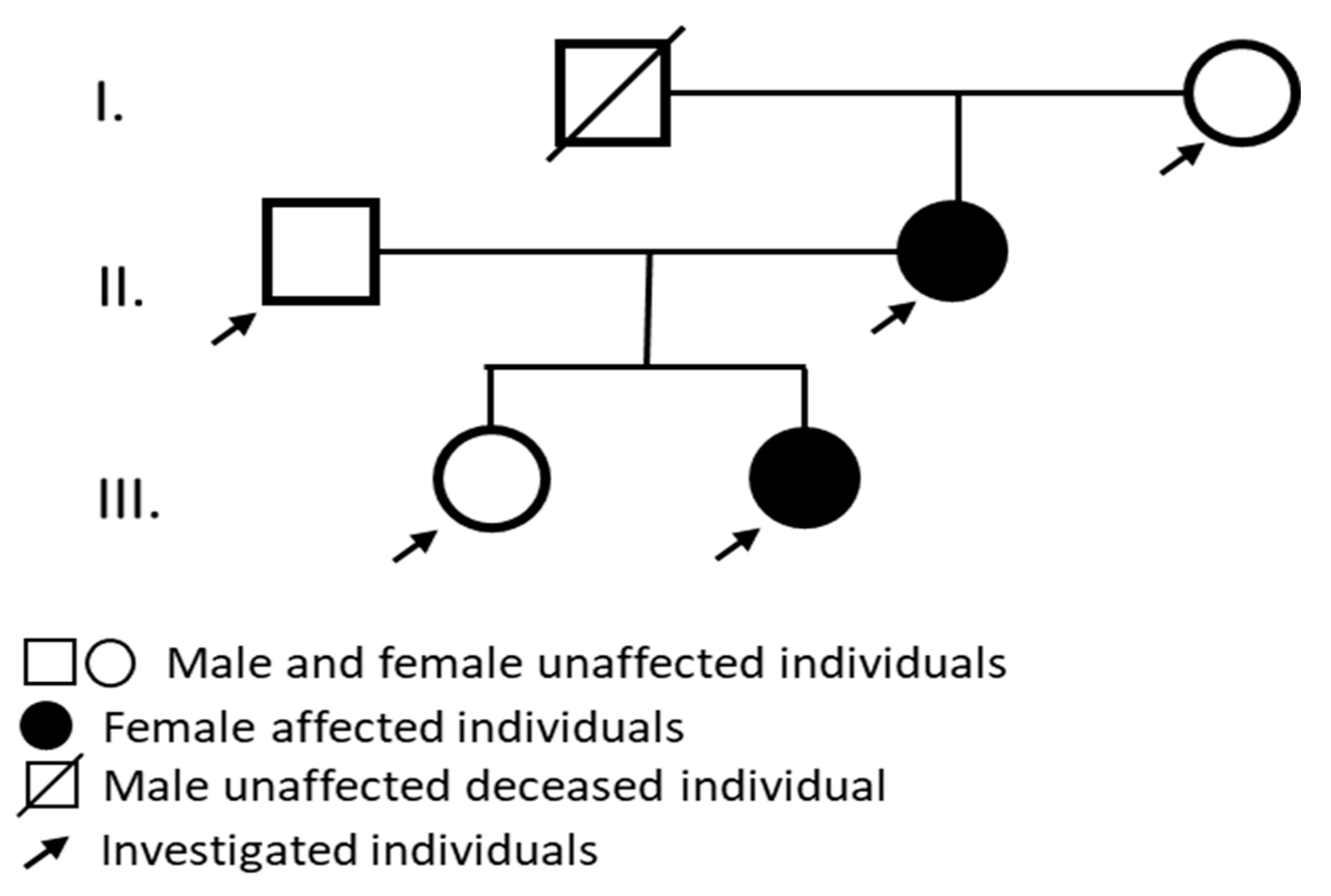

Audiological tests were performed and the affected individuals showed sensorineural hearing loss with similar clinical features (

Figure 1).

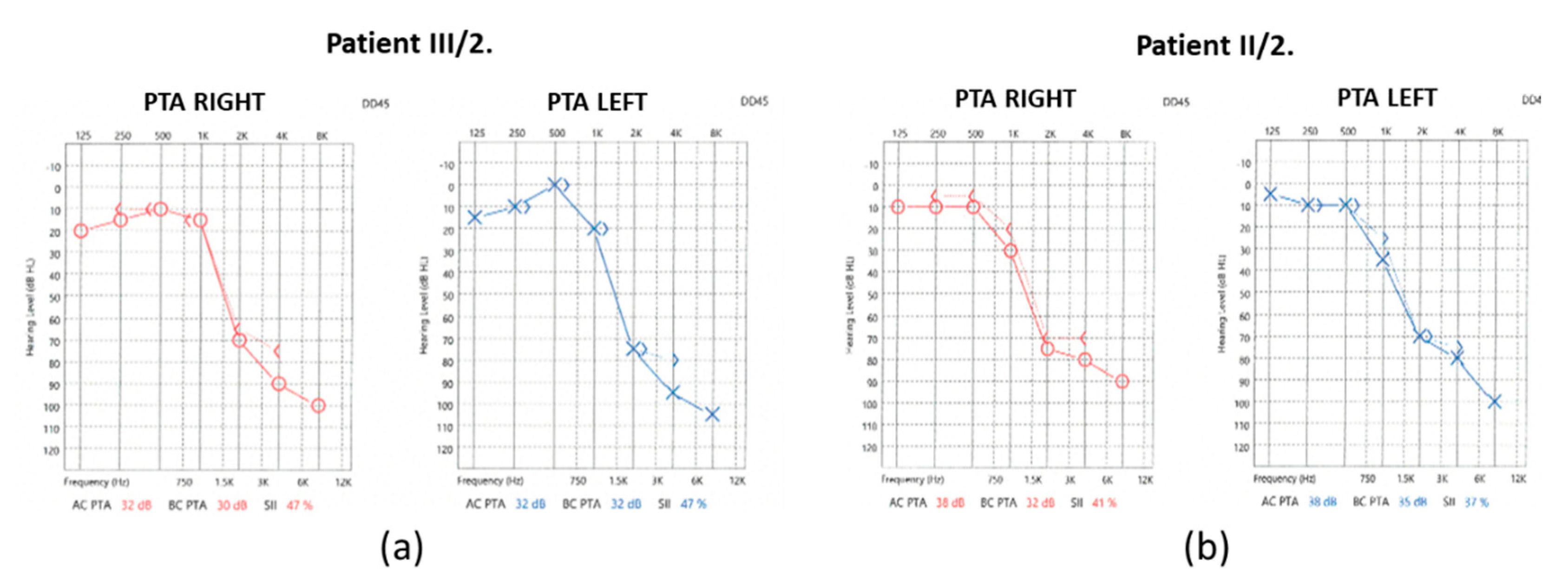

In the case of the mother (II/2), the pure-tone audiometry (PTA) results showed significantly impaired high-tone perception in the 2-8 kHz range, whereas the low-tone (0.125-0.5 kHz) range perception was spared (

Figure 2).

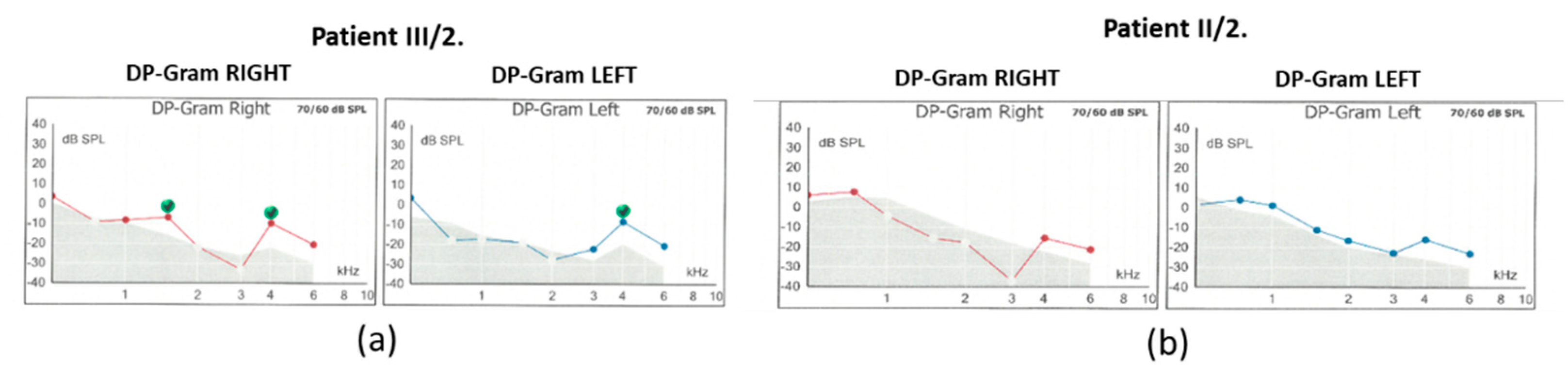

Hearing threshold at 1kHz was mildly impaired. Tympanometry revealed normal middle ear ventilation with -3 daPa and 38 daPa pressures (“A” type tympanogram). The acoustic reflex threshold (ART) was absent at 500 and 1000 Hz up to 100dB stimulus intensity. Regarding the distortion-product otoacoustic emission (DPOAE), at 70/60 dB SPL stimulus intensity, the DP-grams showed absent otoacoustic emissions in both ears (

Figure 3).

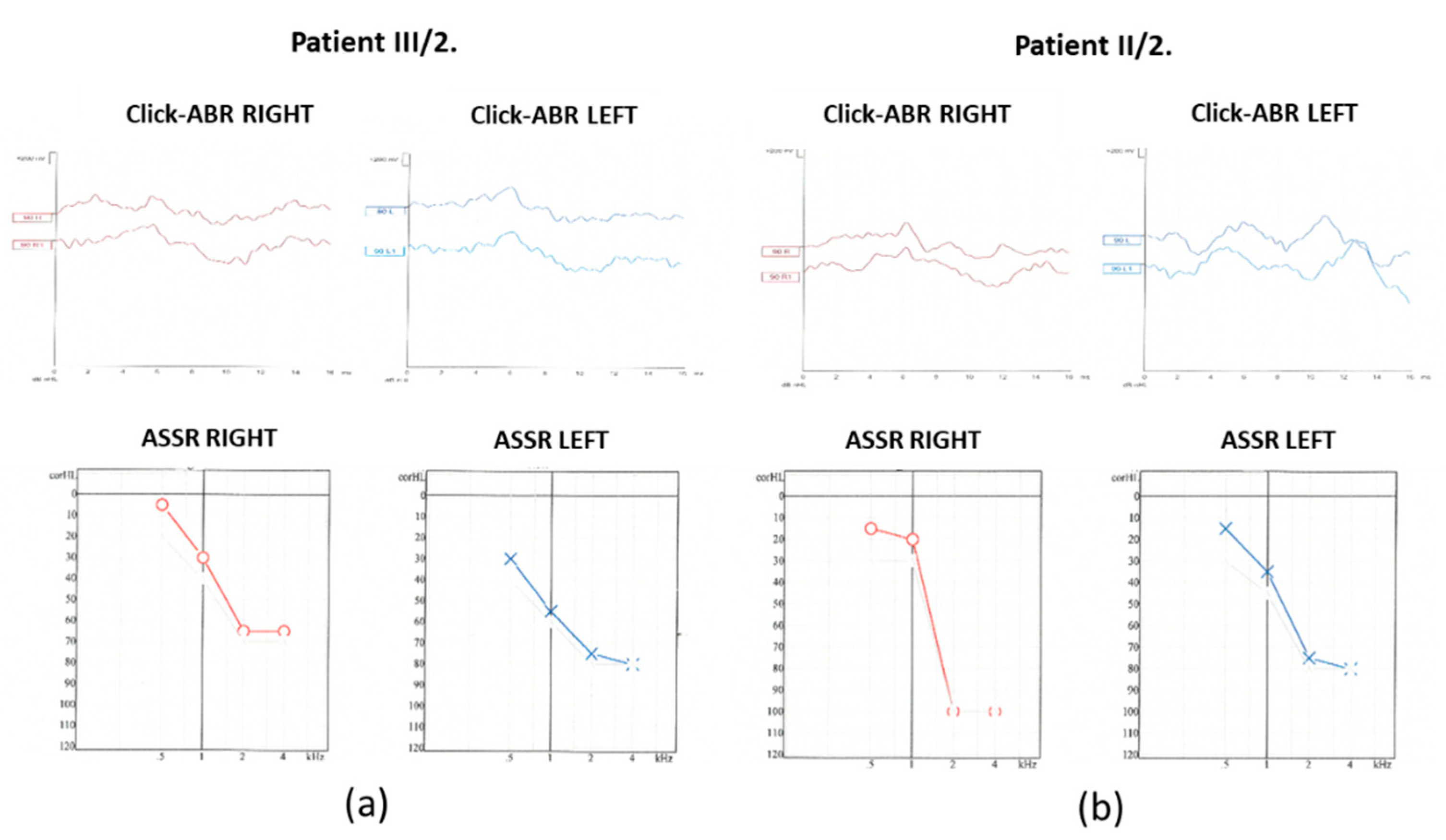

click evoked-auditory brain stem response audiometry (click-ABR) and auditory steady-state response audiometry (ASSR) measurements were performed (

Figure 4).

At 90 dB nHL stimulus intensity from the right ear, the Vth wave was indefinably present. In contrast, from the left ear, the Vth wave was absent. The objective hearing thresholds measured at frequencies of 0.5, 1, 2 and 4kHz were consistent with the PTA subjective results (right ear: 15, 20, 100 and 100 dB corHL; left ear: 15, 35, 75 and 80 dB corHL).

For the daughter (III/2), the PTA results showed a significantly impaired high-tone perception in the 2-8 kHz range (

Figure 2), whereas the low-tone (0.125-1 kHz) range perception was normal. Tympanometry proved normal middle ear ventilation with 0 daPa and 0 daPa pressure (“A” type tympanogram). The ART was 500 and 2000 Hz, while absent at 4 kHz. At 70/60 dB SPL stimulus intensity the DP-grams showed nearly absent otoacoustic emissions in both ears (

Figure 3). At 90 dB nHL stimulus intensity only the Vth waves were defined and reproducible on both sides. The objective hearing thresholds, measured at frequencies of 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz were consistent with the PTA subjective results (right ear: 5, 30, 65 and 65 dB corHL; left ear: 30, 55, 75 and 80 dB corHL) (

Figure 4). MRI did not reveal any abnormalities in the inner ears of the affected mother and daughter (

Figure 5).

The audiograms for both individuals’ showed significantly impaired high-tone perception, whereas the low-tone perception was spared with a “ski-slope-type curve”. Based on the medical history of the subjects, their hearing loss may have developed at the same time. As the hearing threshold of the II/2. mother deteriorated only slightly over time, this slow progression may continue for decades. This is important for long-term hearing rehabilitation, as conventional hearing assistive solutions appear to provide stable and good rehabilitative effects over the long-term. Based on the available data, an indication for cochlear implantation was not supported.

2.2. Genetic Investigations

Genetic examination of the affected family was initiated. WES identified a novel (c.5360A>G, p.Lys1787Arg) rare germline heterozygous missense variant in the 38th exon of the

TRRAP gene NM_001244580.2 (

Figure 6) located at 7q22.1.

This variant was present in the two affected patients (II/2. mother and III/2. daughter) and not found in any unaffected family members (I/2. grandmother, II/1. father and III/1. daughter). Regarding the variant frequency data in different populations this variant shows extremely low frequency in gnomAD population databases (PM2). The pathogenicity of this variant is further supported by its complete cosegregation with the phenotype (PP1). Based on the ACMG variant classification guideline this variant is classified as a leaning pathogenic VUS.

In silico functional predictions using SHIFT, Mutation Taster and CADD suggested that the newly identified missense variant may has a putative disease-causing role in the development of the observed hearing loss, while Polyphen2, EVE and AlphaMissense suggest a benign effect (

Figure 8).

Regarding the encoded TRRAP protein (UniProt Q9Y4A5), the detected missense variant affects the Tra1 HEAT repeat ring region (located from amino acid 541 to amino acid 2011) (

Figure 8) (Protein Data Bank,

https://www.rcsb.org/3d-sequence/7KTR?asymId=A). section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3. Discussion

Using WES, we identified a novel heterozygous missense variant (p.Lys1787Arg) of the TRRAP gene that shows complete cosegregation with the ADNSHL phenotype in a Hungarian family. Interestingly,

TRRAP has been recently linked to this phenotype (2019), and so far, only four variants of the gene have been associated with this condition [

5].

The identified novel variant (p.Lys1787Arg) affects the Tra1 HEAT repeat ring region domain of the TRRAP protein, which consists of alpha solenoid repeats that form a ring region [

10]. Tra1 domains are important for the recruitment and activation of SAGA and NuA4 complexes [

11,

12]. Previously it was suggested that the identified genetic variants affect this function of the protein [

5]. We assume that similarly to this, the novel variant may also affect this function. Further studies are needed to examine this putative mechanism and other unidentified mechanism(s), which may also explain how the ADNSHL-causing variants of the

TRRAP gene contribute to disease development.

Due to the severe grade high frequency sensorineural hearing impairment in the 2-4 kHz range, a differential diagnosis between the cochlear vs. retrocochlear origin requires more complex diagnostic procedures, such as MRI. Although the MRI examination did not reveal any abnormalities of the inner ear and audiological findings partially support (on the contrary do not exclude) the cochlear origin of hearing loss, the cochlea may be the site of the lesion. This correlates well with the results on trrap knockdown and knockout zebrafish study: the observed reduced lateral line neuromasts, the decreased number of hair cells per neuromast and the abnormal stereocilia on the hair cells of the animals suggest relevant functional losses that resemble the diseased phenotype [

5].

Our study further demonstrates that the genetic background of ADNSHL is highly complex, widens the spectrum of the known disease-associated variants in this condition, and confirms that

TRRAP is truly a candidate gene in ADNSHL. Our results further expand our knowledge and broadens the genetic landscape of ADNSHL in the Hungarian population [

13]. From the perspective of the clinical geneticist, we conclude that WES is an effective approach for establishing the genetic background of ADNSHL. Our study also highlights that the identification of the precise genetic background is of clinical significance, because it estimates the risk to the individual their family members to ADNSHL. On the long run these type of studies may contribute to the development of preventive screening and probably in the future effective therapies for patients and hearing loss-prone families. Nonetheless, the underlying mechanism through which this newly detected variant contributes to the development of this unique phenotype requires further study.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patients and Samples

A Hungarian pedigree with ADNSHL was enrolled (

Figure 1a pedigree). A genetic analysis was performed on two affected family members (II/2. mother and III/2. daughter) and three clinically unaffected family members (I/2. grandmother, II/1. father and III/1. daughter). A detailed clinical workup was performed. To test the auditory system PTA, impedance audiometry (tympanometry and ART), DPOAE, click-ABR and ASSR measurements were performed. The affected individuals showed sensorineural hearing loss with similar clinical features. High frequencies were first impared followed by speech and lower frequencies. From the audiological and otoneurological examination, the audiogram (

Figure 1b) showed sensorineural hearing loss that primarily affected high frequencies. All enrolled subjects had normal ear anatomy and none had any prior ear surgery. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination was also performed (

Figure 1c).

After genetic counseling and obtaining written informed consent, peripheral blood samples were collected and genomic DNA was isolated using QIAGEN kits. Genetic testing for ADNSHL was done according to recommendations published online (

http://hereditaryhearingloss.org/). This study was approved by the Hungarian National Public Health Centre and was conducted according to the Helsinki guidelines.

4.2. Whole Exome Sequencing

Patients’ genotypes were determined using targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS). Libraries were prepared using the SureSelectQXT Reagent Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Pooled libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq 550 NGS platform using a 300-cycle Mid Output Kit v2.5 (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Adapter-trimmed and Q30-filtered paired-end reads were aligned to the hg19 human reference genome using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA). Duplicates were marked using the Picard software package. The Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) was used for variant calling (BaseSpace BWA Enrichment Workflow v2.1.1. with BWA 0.7.7-isis-1.0.0, Picard: 1.79 and GATK v1.6-23-gf0210b3).

Sequencing revealed that the mean on-target coverage was 71× per base with an average percentage of targets covered that were greater or equal to 30×, respectively. Variants passed through the GATK filter were used for downstream analysis and annotated with the ANNOVAR software tool (version 2017 July 17). Single-nucleotide polymorphism testing was performed as follows: high-quality sequences were aligned with the human reference genome (GRCh37/hg19) to detect sequence variants, which were analyzed and annotated. The variants were filtered according to read depth, allele frequency, and prevalence reported in genomic variant databases, such as ExAc (v.0.3) and Kaviar. Variant prioritization tools (PolyPhen-2, SIFT, LRT, Mutation Assessor) were used to predict the functional impact of the mutation. We interpreted the sequencing results using the Franklin Genoox website. VarSome and Franklin bioinformatic platforms (

https://franklin.genoox.com) were used based on the guidelines of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. The candidate variants were confirmed by bidirectional capillary Sanger sequencing.

5. Conclusions

A novel pathogenic germline heterozygous missense variant (c.5360A>G, p.Lys1787Arg) was identified in the TRRAP gene (NM_001244580.2) of a Hungarian family that presented with ADNSHL. This gene has been recently linked to ADNSHL and its disease-causing variants (n=4) have only been found in Chinese patients. This is the second study, confirming an association between TRRAP and ADNSHL. Our study also highlights the importance of establishing the genetic background of ADNSHL and demonstrates that considering its complexity, WES is a straightforward and effective approach for genetic disease screening. Our study provides further insight into ADNSHL, and improves the estimation of the risk to individuals and their family members.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.R. and M.S.; methodology, M.P.; validation, B.A.B., Á.S.T.. and N.N.; formal analysis, J.A.J.; investigation, R.N.; resources, R.L.; data curation, M.P.; writing—original draft preparation, N.N.; writing—review and editing, M.S.; supervision, M.S.; project administration, M.P.; funding acquisition, L.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the EFOP-3.6.1-16-2016-00008 grant and by the GINOP-2.3.2-15-2016-00039 grants of the HUNGARIAN GOVERNMENT. The APC was funded by the open access grant of the UNIVERSITY OF SZEGED (grant number 7277).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the UNIVERSITY OF SZEGED (58523-4/2017/EKU).”

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper and pre- and post-test genetic counselling have been carried out.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because they are genetic data.

Acknowledgments

We thank for Dalma Füstös for her technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Funamura, J.L. Evaluation and management of nonsyndromic congenital hearing loss. Curr Opin Otolaryngol 2017, 25, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.S.; Emmett, S.D.; Robler, S.K.; Tucci, D.L. Global hearing loss prevention. Otolaryngol Clin N Am 2018, 51, 575–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, L.L.; Tucci, D.L. Hearing loss in adults. N Engl J Med 2017, 377, 2465–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, M.M.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, Y.; Li, J.; Zheng, Q.; Bai, X.; Wang, H. A novel nonsense mutation of POU4F3 gene causes autosomal dominant hearing loss. Neural Plast 2016, 2016, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xia, W.; Hu, J.; Ma, J.; Huang, J.; Wang, X.; Jiang, N.; Zhang, J.; Ma, Z.; Ma, D. Novel TRRAP mutation causes autosomal dominant non-syndromic hearing loss. Clin Genet 2019, 96, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Templeton, G.W.; Moorhead, G.B.G. The phosphoinositide-3-OH-kinaserelated kinases of Arabidopsis thaliana. EMBO Rep 2005, 6, 723–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Murr, R.; Vaissiere, T.; Sawan, C.; et al. Orchestration of chromatin-based processes: mind the TRRAP. Oncogene 2007, 26, 5358–5372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loizou, J.I.; Murr, R.; Finkbeiner, M.G.; Sawan, C.; Wang, Z.Q.; Herceg, Z. Epigenetic information in chromatin: the code of entry for DNA repair. Cell Cycle 2006, 5, 696–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrozza, M.J.; Utley, R.T.; Workman, J.L.; Côté, J. The diverse functions of histone acetyltransferase complexes. Trends Genet 2003, 19, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharov, G.; Voltz, K.; Durand, A.; Kolesnikova, O.; Papai, G.; Myasnikov, A.G.; Dejaegere, A.; Ben, Shem, A. ; Schultz, P. Structure of the transcription activator target Tra1 within the chromatin modifying complex SAGA. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Knutson, B.A.; Hahn, S. Domains of Tra1 important for activator recruitment and transcription coactivator functions of SAGA and NuA4 complexes. Mol Cell Biol 2011, 31, 818–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, X.; Ahmad, S.; Zhang, Z.; Côté, J.; Cai, G. Architecture of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae NuA4/TIP60 complex. Nat Commun. 2018, 9, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pál, M.; Nagy, D.; Neller, A.; Farkas, K.; Leprán-Török, D.; Nagy, N.; Füstös, D.; Nagy, R.; Németh, A.; Szilvássy, J.; Rovó, L.; Kiss, J.G.; Széll, M. Genetic Etiology of Nonsyndromic Hearing Loss in Hungarian Patients. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 7401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).