Submitted:

10 January 2025

Posted:

13 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

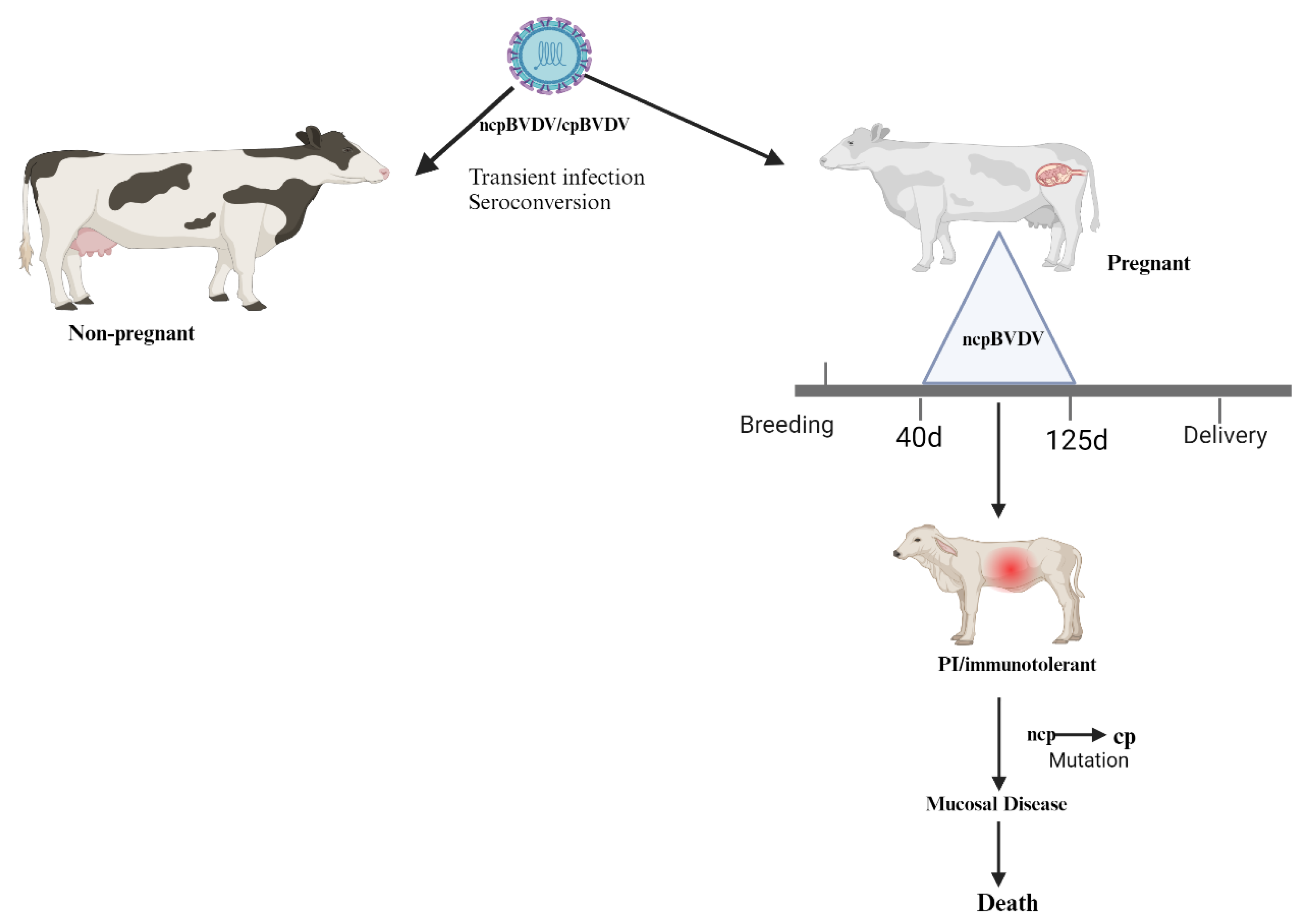

2. Pathogenesis

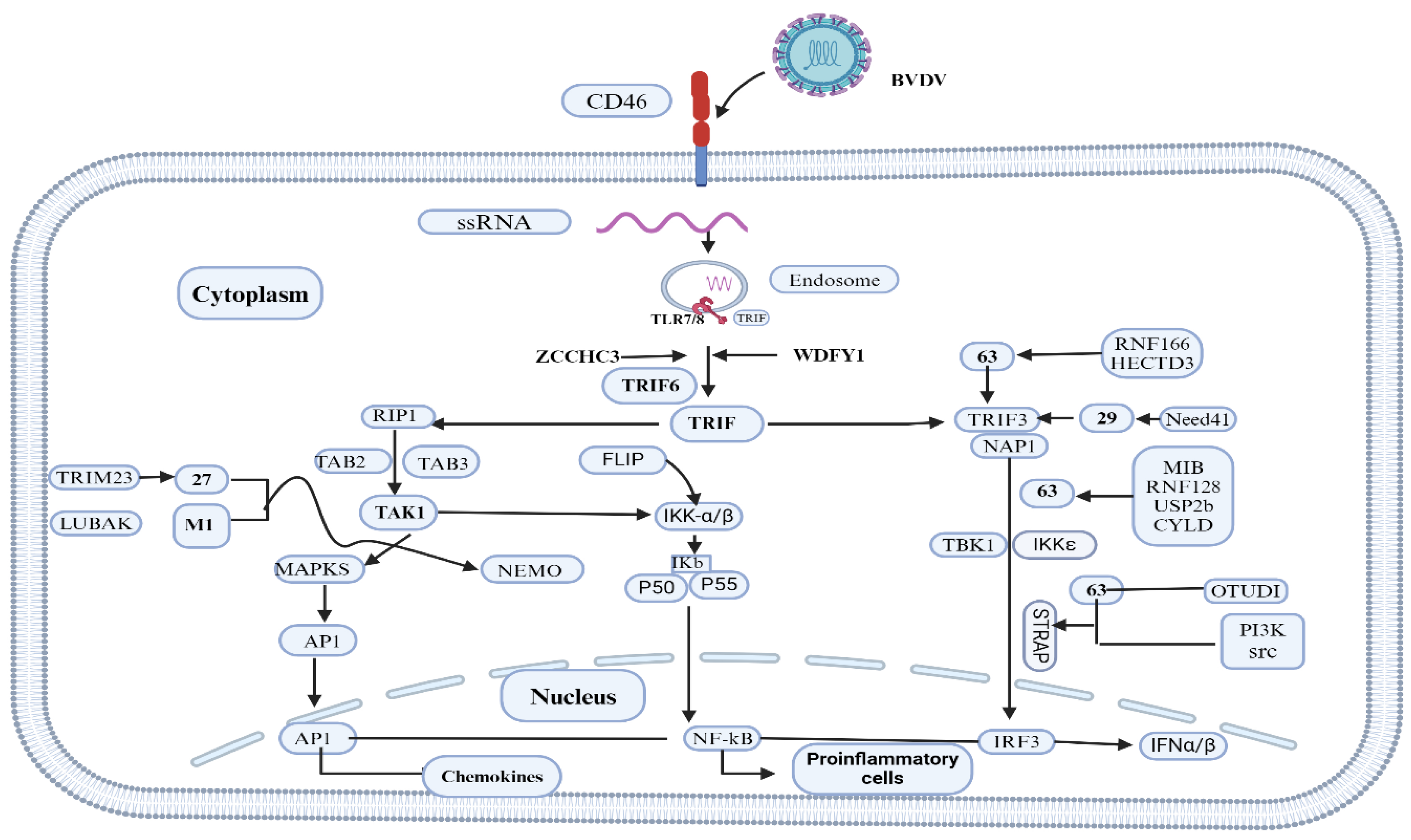

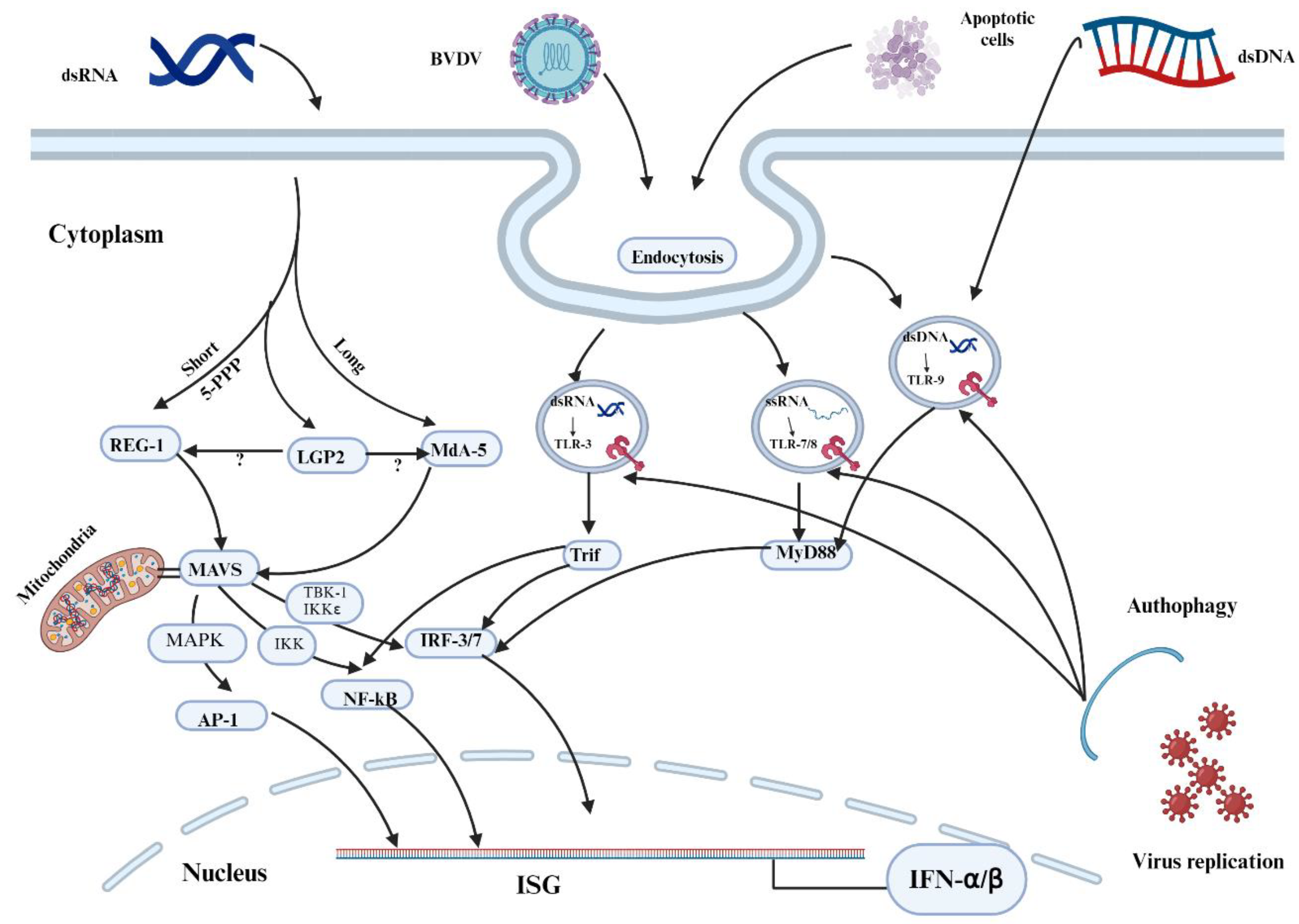

3. BVDV and the Innate Immune System

3.1. Interferon α/β

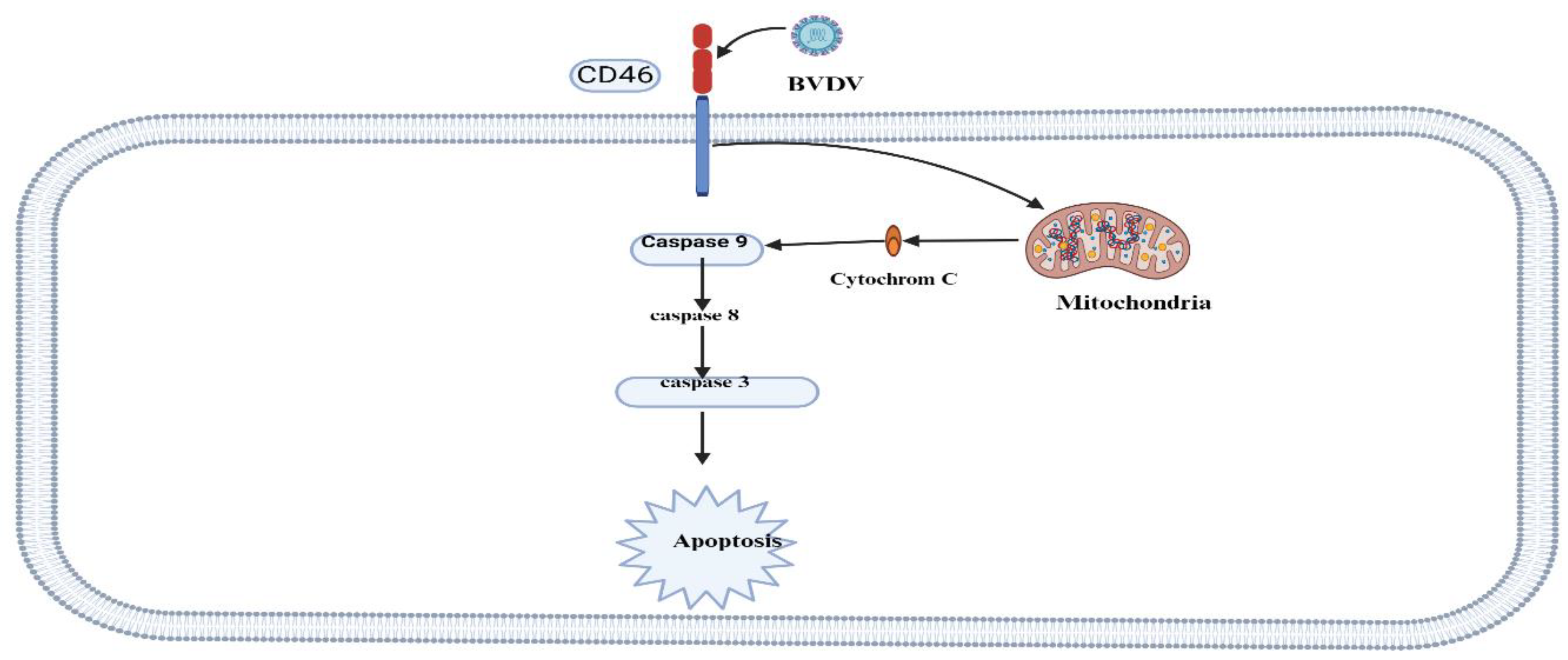

3.2. BVDV Triggers Apoptosis

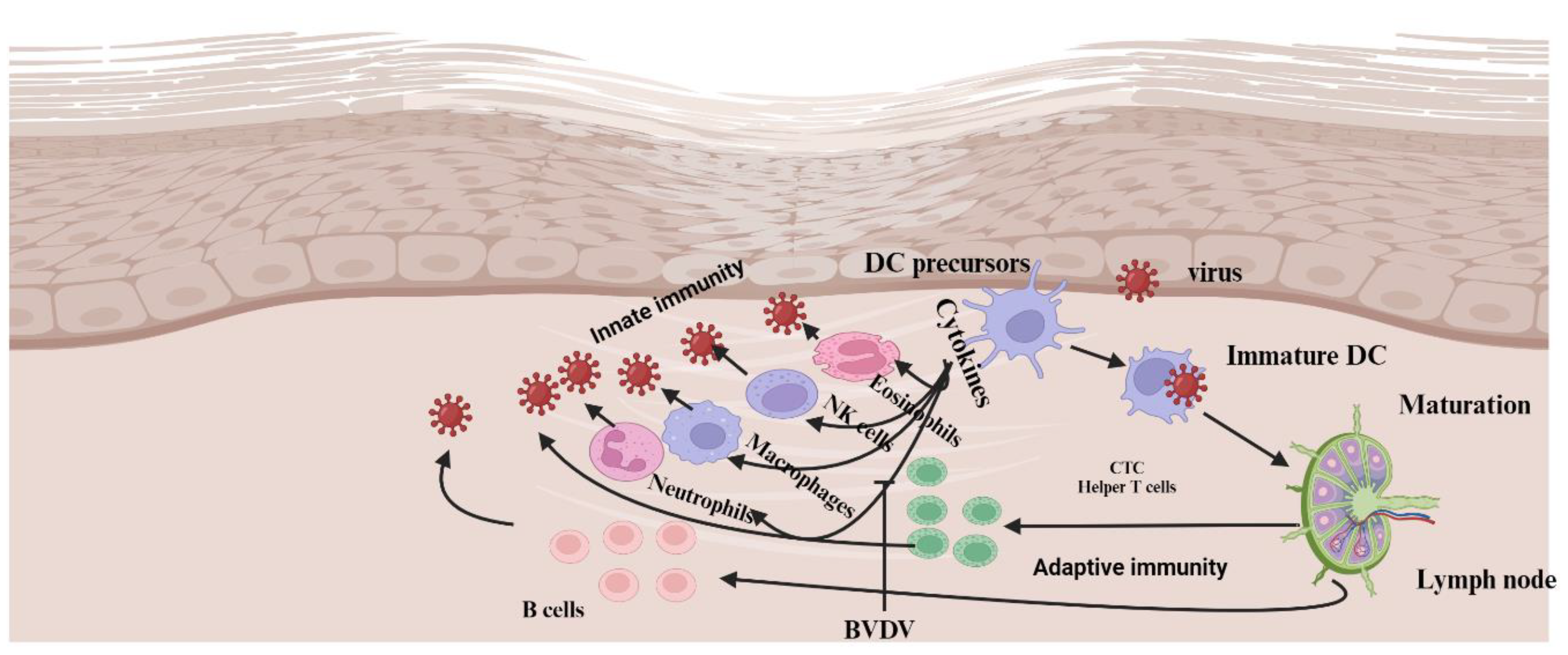

3.3. BVDV and Innate Immune Cells

3.3.1. Neutrophils

3.3.2. Macrophages

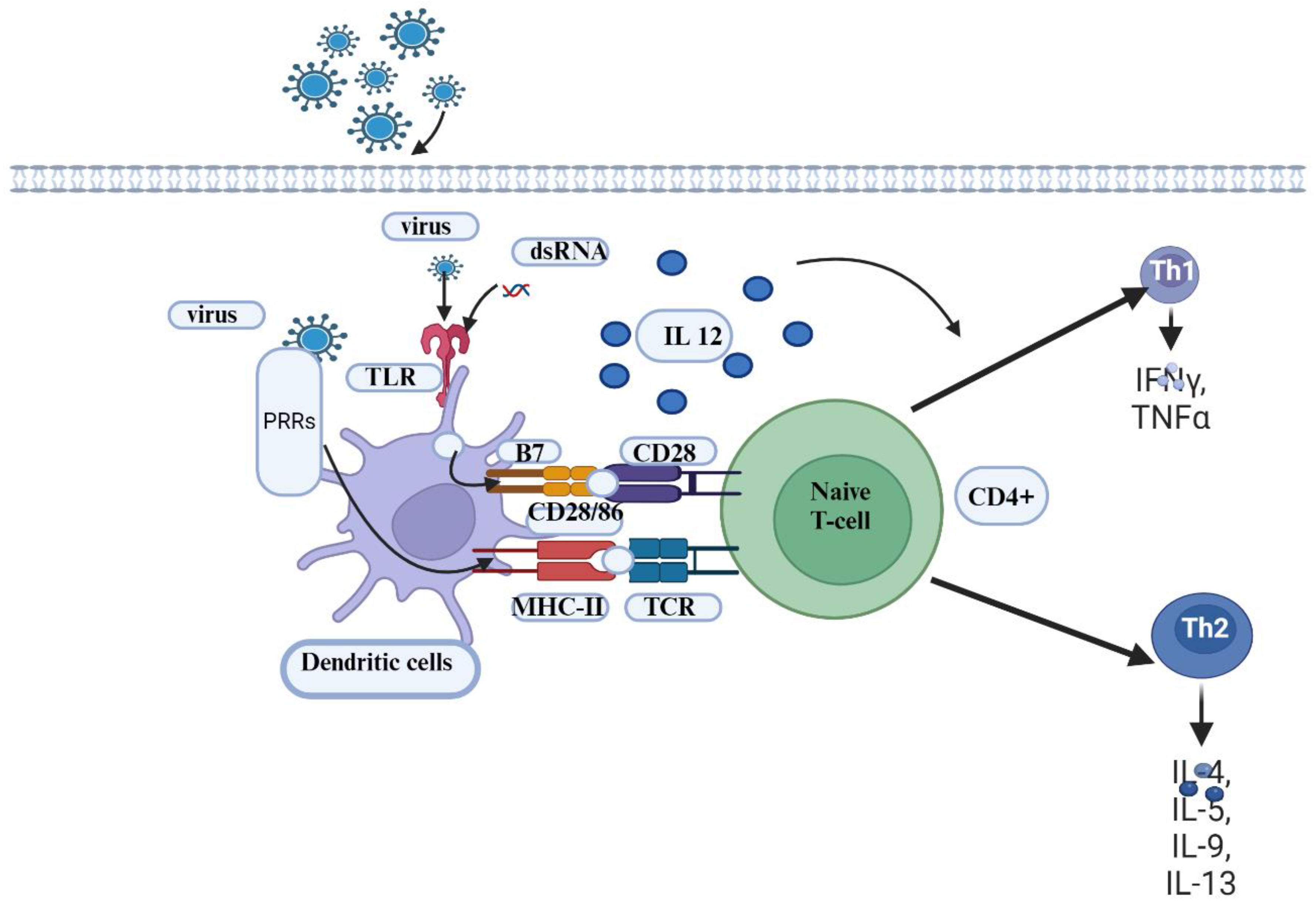

3.3.3. Antigen-Presenting (APC)

3.4. Adaptive Immune System

3.5. The Role of Maternal Antibody(MatAb) in Protecting Calves Against BVDV

3.6. BVDV Vaccines and Application

3.6.1. Conventional Vaccines

3.6.2. Next Generation Vaccines

4. Conclusions

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fulton RW, Briggs RE, Ridpath JF, Saliki JT, Confer AW, Payton ME, et al. Transmission of Bovine viral diarrhea virus 1b to susceptible and vaccinated calves by exposure to persistently infected calves. Can J Vet Res. 2005, 69, 161–9.

- Khodakaram-Tafti, A.; Farjanikish, G.H. Persistent bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) infection in cattle herds. Iran J Vet Res. 2017, 18, 154–63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Deregt, D.; Loewen, K.G. Bovine viral diarrhea virus: biotypes and disease. Can Vet J. 1995, 36, 371–8. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, K.V. The many faces of bovine viral diarrhea virus. Vet Clin North Am - Food Anim Pract. 2004, 20, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith DB, Meyers G, Bukh J, Gould EA, Monath T, Muerhoff AS, et al. Proposed revision to the taxonomy of the genus Pestivirus, family Flaviviridae. J Gen Virol. 2017, 98, 2106–12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeşilbağ, K.; Alpay, G.; Becher, P. Variability and global distribution of subgenotypes of bovine viral diarrhea virus. Viruses. 2017;9.

- Liu, L.; Xia, H.; Wahlberg, N.; Belák, S.; Baule, C. Phylogeny, classification and evolutionary insights into pestiviruses. Virology. 2009, 385, 351–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammari, M.; McCarthy, F.M.; Nanduri, B.; Pinchuk, L.M. Analysis of Bovine Viral Diarrhea Viruses-infected monocytes: identification of cytopathic and non-cytopathic biotype differences. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilleman, M.R. Strategies and mechanisms for host and pathogen survival in acute and persistent viral infections. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101 SUPPL. 2:14560–6.

- Peterhans E, Jungi TW, Schweizer M. BVDV and innate immunity. Biologicals. 2003, 31, 107–12.

- Koyama, S.; Ishii, K.J.; Coban, C.; Akira, S. Innate immune response to viral infection. Cytokine. 2008, 43, 336–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouyssi-Kobar M, De Asis-Cruz J, Murnick J, Chang T, Limperopoulos C. 乳鼠心肌提取 HHS Public Access. J Pediatr. 2019, 227, 13–2.

- Alcami, A.; Koszinowski, U.H. Viral mechanisms of immune evasion. Trends Microbiol. 2000, 8, 410–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopp, P.; Hooper, L.B.; Clarke, M.C.; Howard, C.J.; Brownlie, J. Detection of bovine viral diarrhoea virus p80 protein in subpopulations of bovine leukocytes. J Gen Virol. 1994, 75, 1189–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chase, C.C.L.; Elmowalid, G.; Yousif, A.A.A. The immune response to bovine viral diarrhea virus: A constantly changing picture. Vet Clin North Am - Food Anim Pract. 2004, 20, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givens, M.D.; Marley, M.S. Immunology of chronic BVDV infections. Biologicals. 2013, 41, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.C. The clinical manifestations of bovine viral diarrhea infection. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 1995, 11, 425–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moennig V, Eicken K, Flebbe U, Frey HR, Grummer B, Haas L, et al. Implementation of two-step vaccination in the control of bovine viral diarrhoea (BVD). Prev Vet Med. 2005, 72, 109–14.

- Rodning SP, Marley MSD, Zhang Y, Eason AB, Nunley CL, Walz PH, et al. Comparison of three commercial vaccines for preventing persistent infection with bovine viral diarrhea virus. Theriogenology. 2010, 73, 1154–63.

- Falkenberg, S.M.; Dassanayake, R.P.; Terhaar, B.; Ridpath, J.F.; Neill, J.D.; Roth, J.A. Evaluation of Antigenic Comparisons Among BVDV Isolates as it Relates to Humoral and Cell Mediated Responses. Front Vet Sci. 2021;8 June:1–13.

- Sangewar N, Hassan W, Lokhandwala S, Bray J, Reith R, Markland M, et al. Mosaic Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus Antigens Elicit Cross-Protective Immunity in Calves. Front Immunol. 2020;11 November:1–15.

- Lokhandwala S, Fang X, Waghela SD, Bray J, Njongmeta LM, Herring A, et al. Priming cross-protective bovine viral diarrhea virus-specific immunity using live-vectored mosaic antigens. PLoS One. 2017, 12, 1–23.

- Brackenbury, L.S.; Carr, B.V.; Charleston, B. Aspects of the innate and adaptive immune responses to acute infections with BVDV. Vet Microbiol. 2003, 96, 337–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnova NP, Webb BT, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H, Van Campen H, Antoniazzi AQ, Morarie SE, et al. Development of fetal and placental innate immune responses during establishment of persistent infection with bovine viral diarrhea virus. Virus Res. 2012, 167, 329–36.

- Brock, K.V. The persistence of bovine viral diarrhea virus. Biologicals. 2003, 31, 133–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-Zanzi, C.A.; Hietala, S.K.; Thurmond, M.C.; Johnson, W.O. Quantification, risk factors, and health impact of natural congenital infection with bovine viral diarrhea virus in dairy calves. Am J Vet Res. 2003, 64, 358–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katze, M.G.; He, Y.; Gale, M. Viruses and interferon: A fight for supremacy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002, 2, 675–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bencze, D.; Fekete, T.; Pázmándi, K. Type i interferon production of plasmacytoid dendritic cells under control. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweizer M, Mätzener P, Pfaffen G, Stalder H, Peterhans E. “Self” and “Nonself” Manipulation of Interferon Defense during Persistent Infection: Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus Resists Alpha/Beta Interferon without Blocking Antiviral Activity against Unrelated Viruses Replicating in Its Host Cells. J Virol. 2006, 80, 6926–35.

- Bonjardim, C.A. Interferons (IFNs) are key cytokines in both innate and adaptive antiviral immune responses - And viruses counteract IFN action. Microbes Infect. 2005, 7, 569–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Sastre, A. Mechanisms of inhibition of the host interferon α/β-mediated antiviral responses by viruses. Microbes Infect. 2002, 4, 647–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil LHVG, Ansari IH, Vassilev V, Liang D, Lai VCH, Zhong W, et al. The Amino-Terminal Domain of Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus N pro Protein Is Necessary for Alpha/Beta Interferon Antagonism. J Virol. 2006, 80, 900–11.

- Chang, Y.E.; Laimins, L.A. Microarray Analysis Identifies Interferon-Inducible Genes and Stat-1 as Major Transcriptional Targets of Human Papillomavirus Type 31. J Virol. 2000, 74, 4174–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chase, C.C.L.; Thakur, N.; Darweesh, M.F.; Morarie-Kane, S.E.; Rajput, M.K. Immune response to bovine viral diarrhea virus - Looking at newly defined targets. Anim Heal Res Rev. 2015, 16, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweizer, M.; Peterhans, E. Pestiviruses. Annu Rev Anim Biosci. 2014, 2, 141–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chase, C.C.L. The impact of BVDV infection on adaptive immunity. Biologicals. 2013, 41, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniel Givens M, Marley MSD, Jones CA, Ensley DT, Galik PK, Zhang Y, et al. Protective effects against abortion and fetal infection following exposure to bovine viral diarrhea virus and bovine herpesvirus 1 during pregnancy in beef heifers that received two doses of a multivalent modified-live virus vaccine prior to breeding. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2012, 241, 484–95.

- Funami, K.; Matsumoto, M.; Oshiumi, H.; Akazawa, T.; Yamamoto, A.; Seya, T. The cytoplasmic “linker region” in Toll-like receptor 3 controls receptor localization and signaling. Int Immunol. 2004, 16, 1143–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funami, K.; Sasai, M.; Ohba, Y.; Oshiumi, H.; Seya, T.; Matsumoto, M. Spatiotemporal Mobilization of Toll/IL-1 Receptor Domain-Containing Adaptor Molecule-1 in Response to dsRNA. J Immunol. 2007, 179, 6867–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen 2021. Chen, 2021.pdf. 2021, 22, 609–32.

- Chen Z, Rijnbrand R, Jangra RK, Devaraj SG, Qu L, Ma Y, et al. Ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of interferon regulatory factor-3 induced by Npro from a cytopathic bovine viral diarrhea virus. Virology. 2007, 366, 277–92.

- Hong, T.; Yang, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhu, G.; Zhu, C. Pestiviruses infection: Interferon-virus mutual regulation. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023;13 March:1–13.

- Hilton L, Moganeradj K, Zhang G, Chen Y-H, Randall RE, McCauley JW, et al. The NPro Product of Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus Inhibits DNA Binding by Interferon Regulatory Factor 3 and Targets It for Proteasomal Degradation. J Virol. 2006, 80, 11723–32.

- Li Z, Zhang Y, Zhao B, Xue Q, Wang C, Wan S, et al. Non-cytopathic bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) inhibits innate immune responses via induction of mitophagy. Vet Res. 2024, 55, 27.

- Peterhans E, Schweizer M. BVDV: A pestivirus inducing tolerance of the innate immune response. Biologicals. 2013, 41, 39–51.

- Ruggli, N.; Bird, B.H.; Liu, L.; Bauhofer, O.; Tratschin, J.D.; Hofmann, M.A. Npro of classical swine fever virus is an antagonist of double-stranded RNA-mediated apoptosis and IFN-α/β induction. Virology. 2005, 340, 265–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnova NP, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H, Van Campen H, Austin KJ, Han H, Montgomery DL, et al. Acute non-cytopathic bovine viral diarrhea virus infection induces pronounced type I interferon response in pregnant cows and fetuses. Virus Res. 2008, 132, 49–58.

- Schweizer, M.; Peterhans, E. Noncytopathic Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus Inhibits Double-Stranded RNA-Induced Apoptosis and Interferon Synthesis. J Virol. 2001, 75, 4692–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, F.; Long, Q.; Wei, M. Immune evasion strategies of bovine viral diarrhea virus. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023;13 October:1–8.

- Alexenko, A.P.; Ealy, A.D.; Roberts, R.M. The cross-species antiviral activities of different IFN-τ- subtypes on bovine, murine, and human cells: Contradictory evidence for therapeutic potential. J Interf Cytokine Res. 1999, 19, 1335–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grummer, B.; Bendfeldt, S.; Wagner, B.; Greiser-Wilke, I. Induction of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway in cells infected with cytopathic bovine virus diarrhoea virus. Virus Res. 2002, 90, 143–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilbe, M.; Girao, V.; Bachofen, C.; Schweizer, M.; Zlinszky, K.; Ehrensperger, F. Apoptosis in Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus (BVDV)-Induced Mucosal Disease Lesions: A Histological, Immunohistological, and Virological Investigation. Vet Pathol. 2013, 50, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verburg, S.G.; Lelievre, R.M.; Westerveld, M.J.; Inkol, J.M.; Sun, Y.L.; Workenhe, S.T. Viral-mediated activation and inhibition of programmed cell death. 2022.

- Darweesh MF, Rajput MKS, Braun LJ, Rohila JS, Chase CCL. BVDV Npro protein mediates the BVDV induced immunosuppression through interaction with cellular S100A9 protein. Microb Pathog. 2018;121 April:341–9.

- Flint, M.S.; Miller, D.B.; Tinkle, S.S. Restraint-induced modulation of allergic and irritant contact dermatitis in male and female B6. 129 Mice. Brain Behav Immun. 2000, 14, 256–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, S.D.; DeLeo, F.R. Role of neutrophils in innate immunity: A systems biology-level approach. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2009, 1, 309–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantovani, A.; Cassatella, M.A.; Costantini, C.; Jaillon, S. Neutrophils in the activation and regulation of innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011, 11, 519–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, G.B.; Albright, B.N.; Caswell, J.L. Effect of interleukin-8 and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor on priming and activation of bovine neutrophils. Infect Immun. 2003, 71, 1643–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, M.J.; Lin, K.S.; King, M.R. Fluid shear stress increases neutrophil activation via platelet-activating factor. Biophys J. 2014, 106, 2243–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens MGH, Van Poucke M, Peelman LJ, Rainard P, De Spiegeleer B, Rogiers C, et al. Anaphylatoxin C5a-induced toll-like receptor 4 signaling in bovine neutrophils. J Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 152–64.

- Brown, G.B.; Bolin, S.R.; Frank, D.E.; Roth, J.A. Defective function of leukocytes from cattle persistently infected with bovine viral diarrhea virus, and the influence or recombinant cytokines. Am J Vet Res. 1991, 52, 381–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur N, Evans H, Abdelsalam K, Farr A, Rajput MKS, Young AJ, et al. Bovine viral diarrhea virus compromises Neutrophil’s functions in strain dependent manner. Microb Pathog. 2020;149 May:104515.

- Abdelsalam, K.; Kaushik, R.S.; Chase, C. The Involvement of Neutrophil in the Immune Dysfunction Associated with BVDV Infection. Pathogens. 2023;12.

- Yoshitake, H.; Takeda, Y.; Nitto, T.; Sendo, F. Cross-linking of GPI-80, a possible regulatory molecule of cell adhesion, induces up-regulation of CD11b/CD18 expression on neutrophil surfaces and shedding of L-selectin. J Leukoc Biol. 2002, 71, 205–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, J.A.; Kaeberle, M.L. Suppression of neutrophil and lymphocyte function induced by a vaccinal strain of bovine viral diarrhea virus with and without the administration of ACTH. Am J Vet Res. 1983, 44, 2366–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The E, Viral B, Virus D, Apoptosis L, Abdelsalam K, Rajput M, et al. viruses Strains and the Corresponding Infected-Macrophages ’. 2020.

- Charleston B, Brackenbury LS, Carr B V. , Fray MD, Hope JC, Howard CJ, et al. Alpha/Beta and Gamma Interferons Are Induced by Infection with Noncytopathic Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus In Vivo. J Virol. 2002, 76, 923–7.

- Charleston, B.; Fray, M.D.; Baigent, S.; Carr, B.V.; Morrison, W.I. Establishment of persistent infection with non-cytopathic bovine viral diarrhoea virus in cattle is associated with a failure to induce type I interferon. J Gen Virol. 2001, 82, 1893–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barone, L.J.; Cardoso, N.P.; Mansilla, F.C.; Castillo, M.; Capozzo, A.V. Enhanced infectivity of bovine viral diarrhoea virus (BVDV) in arginase-producing bovine monocyte-derived macrophages. Virulence. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Medzhitov, R. Approaching the Asymptote: 20 Years Later. Immunity. 2009, 30, 766–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaut, R.G.; Ridpath, J.F.; Sacco, R.E. Bovine viral diarrhea virus type 2 impairs macrophage responsiveness to toll-like receptor ligation with the exception of toll-like receptor 7. PLoS One. 2016, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonkers NL, Rodriguez B, Milkovich KA, Asaad R, Lederman MM, Heeger PS, et al. TLR Ligand-Dependent Activation of Naive CD4 T Cells by Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells Is Impaired in Hepatitis C Virus Infection. J Immunol. 2007, 178, 4436–44.

- Biasin M, Piacentini L, Lo Caputo S, Naddeo V, Pierotti P, Borelli M, et al. TLR Activation Pathways in HIV-1–Exposed Seronegative Individuals. J Immunol. 2010, 184, 2710–7.

- Wortham BW, Eppert BL, Motz GT, Flury JL, Orozco-Levi M, Hoebe K, et al. NKG2D Mediates NK Cell Hyperresponsiveness and Influenza-Induced Pathologies in a Mouse Model of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. J Immunol. 2012, 188, 4468–75.

- Glew, E.J.; Carr, B.V.; Brackenbury, L.S.; Hope, J.C.; Charleston, B.; Howard, C.J. Differential effects of bovine viral diarrhoea virus on monocytes and dendritic cells. J Gen Virol. 2003, 84, 1771–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler, H.; Jungi, T.W.; Pfister, H.; Strasser, M.; Sileghem, M.; Peterhans, E. Cytokine regulation by virus infection: bovine viral diarrhea virus, a flavivirus, downregulates production of tumor necrosis factor alpha in macrophages in vitro. J Virol. 1996, 70, 2650–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutler, B.; Cerami, A. The biology of cachectin/TNF - A primary mediator of the host response. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989, 7, 625–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philip, R.; Epstein, L.B. Tumour necrosis factor as immunomodulator and mediator of monocyte cytotoxicity induced by itself, γ-interferon and interleukin-1. Nature. 1986, 323, 86–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsh, M.D.; Adair, B.M.; Foster, J.C. Effect of BVD virus infection on alveolar macrophage functions. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1995, 46, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.R.; Nanduri, B.; Pharr, G.T.; Stokes, J.V.; Pinchuk, L.M. Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus infection affects the expression of proteins related to professional antigen presentation in bovine monocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta - Proteins Proteomics. 2009, 1794, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janeway, C.A.; Medzhitov, R. Innate immune recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002, 20, 197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, E.F.; Boyd, B.L.; Pinchuk, L.M. Bovine monocytes induce immunoglobulin production in peripheral blood B lymphocytes. Dev Comp Immunol. 2003, 27, 889–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, B.L.; Lee, T.M.; Kruger, E.F.; Pinchuk, L.M. Cytopathic and non-cytopathic bovine viral diarrhoea virus biotypes affect fluid phase uptake and mannose receptor-mediated endocytosis in bovine monocytes. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2004, 102, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajput, M.K.; Darweesh, M.F.; Park, K.; Braun, L.J.; Mwangi, W.; Young, A.J.; et al. The effect of bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) strains on bovine monocyte-derived dendritic cells (Mo-DC) phenotype capacity to produce, B. V.D.V. Virol J. 2014, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso N, Franco-Mahecha OL, Czepluch W, Quintana ME, Malacari DA, Trotta MV, et al. Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus Infects Monocyte-Derived Bovine Dendritic Cells by an E2-Glycoprotein-Mediated Mechanism and Transiently Impairs Antigen Presentation. Viral Immunol. 2016, 29, 417–29.

- Collen, T.; Carr, V.; Parsons, K.; Charleston, B.; Morrison, W.I. Analysis of the repertoire of cattle CD4+ T cells reactive with bovine viral diarrhoea virus. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2002, 87, 235–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gennip, H.G.P.; Van Rijn, P.A.; Widjojoatmodjo, M.N.; De Smit, A.J.; Moormann, R.J.M. Chimeric classical swine fever viruses containing envelope protein E(RNS) or E2 of bovine viral diarrhoea virus protect pigs against challenge with CSFV and induce a distinguishable antibody response. Vaccine. 2000, 19, 447–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiland, E.; Ahl, R.; Stark, R.; Weiland, F.; Thiel, H.J. A second envelope glycoprotein mediates neutralization of a pestivirus, hog cholera virus. J Virol. 1992, 66, 3677–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collen T, Morrison WI. CD4+ T-cell responses to bovine viral diarrhoea virus in cattle. Virus Res. 2000, 67, 67–80.

- Rajput, M.K.S.; Darweesh, M.F.; Braun, L.J.; Mansour, S.M.G.; Chase, C.C.L. Comparative humoral immune response against cytopathic or non-cytopathic bovine viral diarrhea virus infection. Res Vet Sci. 2020;129 July 2019:109–16.

- Howard, C.J.; Clarke, M.C.; Sopp, P.; Brownlie, J. Immunity to bovine virus diarrhoea virus in calves: the role of different T-cell subpopulations analysed by specific depletion in vivo with monoclonal antibodies. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1992, 32, 303–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donis, R.O. Molecular biology of bovine viral diarrhea virus and its interactions with the host. Elsevier Masson SAS; 1995.

- Deregt, D.; Masri, S.A.; Cho, H.J.; Ohmann, H.B. Monoclonal antibodies to the p80/125 and gp53 proteins of bovine viral diarrhea virus: Their potential use as diagnostic reagents. Can J Vet Res. 1990, 54, 343–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lambot, M.; Douart, A.; Joris, E.; Letesson, J.J.; Pastoret, P.P. Characterization of the immune response of cattle against non-cytopathic and cytopathic biotypes of bovine viral diarrhoea virus. J Gen Virol. 1997, 78, 1041–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endsley, J.J.; Roth, J.A.; Ridpath, J.; Neill, J. Maternal antibody blocks humoral but not T cell responses to BVDV. Biologicals. 2003, 31, 123–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, C.J.; Clarke, M.C.; Brownlie, J. Protection against respiratory infection with bovine virus diarrhoea virus by passively acquired antibody. Vet Microbiol. 1989, 19, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downey ED, Tait RG, Mayes MS, Park CA, Ridpath JF, Garrick DJ, et al. An evaluation of circulating bovine viral diarrhea virus type 2 maternal antibody level and response to vaccination in Angus calves. J Anim Sci. 2013, 91, 4440–50.

- Fulton RW, Briggs RE, Payton ME, Confer AW, Saliki JT, Ridpath JF, et al. Maternally derived humoral immunity to bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) 1a, BVDV1b, BVDV2, bovine herpesvirus-1, parainfluenza-3 virus bovine respiratory syncytial virus, Mannheimia haemolytica and Pasteurella multocida in beef calves, antibody decline. Vaccine. 2004, 22, 643–9.

- Muñoz-zanzi C a, Thurmond MC, Johnson WO, Hietala SK. Predicted ages of dairy calves when colostrum- derived bovine viral diarrhea virus antibodies or interfere with vaccination. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2002, 221, 678–85.

- Reppert EJ, Chamorro MF, Robinson L, Cernicchiaro N, Wick J, Weaber RL, et al. Reppert et al 2019 vaccination of pregnant beef and antibodies in calves. 2019, 4, 313–6.

- Kim UH, Kang SS, Jang SS, Kim SW, Chung KY, Kang DH, et al. Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus Antibody Level Variation in Newborn Calves after Vaccination of Late-Gestational Cows. Vet Sci. 2023;10.

- Menanteau-Horta, A.M.; Ames, T.R.; Johnson, D.W.; Meiske, J.C. Effect of maternal antibody upon vaccination with infectious bovine rhinotracheitis and bovine virus diarrhea vaccines. Can J Comp Med. 1985, 49, 10–4. [Google Scholar]

- Chamorro MF, Walz PH, Passler T, Santen E, Gard J, Rodning SP, et al. Efficacy of multivalent, modified- live virus (MLV) vaccines administered to early weaned beef calves subsequently challenged with virulent Bovine viral diarrhea virus type 2. BMC Vet Res. 2015, 11, 1–9.

- Fulton RW, Ridpath JF, Saliki JT, Briggs RE, Confer AW, Burge LJ, et al. Bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) 1b: Predominant BVDV subtype in calves with respiratory disease. Can J Vet Res. 2002, 66, 181–90.

- Fulton RW, Purdy CW, Confer AW, Saliki JT, Loan RW, Briggs RE, et al. Bovine viral diarrhea viral infections in feeder calves with respiratory disease: Interactions with Pasteurella spp., parainfluenza-3 virus, and bovine respiratory syncytial virus. Can J Vet Res. 2000, 64, 151–9.

- Fray, M.D.; Paton, D.J.; Alenius, S. The effects of bovine viral diarrhoea virus on cattle reproduction in relation to disease control. Anim Reprod Sci. 2000;60–61:615–27.

- Fulton, R.W.; Cook, B.J.; Payton, M.E.; Burge, L.J.; Step, D.L. Immune response to bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) vaccines detecting antibodies to BVDV subtypes 1a, 1b, 2a, and 2c. Vaccine. 2020, 38, 4032–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newcomer, B.W.; Chamorro, M.F.; Walz, P.H. Vaccination of cattle against bovine viral diarrhea virus. Vet Microbiol. 2017;206 December 2016:78–83.

- Griebel, PJ. BVDV vaccination in North America: Risks versus benefits. Anim Heal Res Rev. 2015, 16, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, W.; Mattick, D.; Smith, L. Protection from persistent infection with a bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) type 1b strain by a modified-live vaccine containing BVDV types 1a and 2, infectious bovine rhinotracheitis virus, parainfluenza 3 virus and bovine respiratory syncytial virus. Vaccine. 2011, 29, 4657–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolin, S.R. Control of bovine viral diarrhea infection by use of vaccination. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 1995, 11, 615–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deregt, D.; Dubovi, E.J.; Jolley, M.E.; Nguyen, P.; Burton, K.M.; Gilbert, S.A. Mapping of two antigenic domains on the NS3 protein of the pestivirus bovine viral diarrhea virus. Vet Microbiol. 2005, 108, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulton RW, Confer AW, Burge LJ, Perino LJ, d’Offay JM, Payton ME, et al. Antibody responses by cattle after vaccination with commercial viral vaccines containing bovine herpesvirus-1, bovine viral diarrhea virus, parainfluenza-3 virus, and bovine respiratory syncytial virus immunogens and subsequent revaccination at day 140. Vaccine. 1995, 13, 725–33.

- Dean, H.J.; Hunsaker, B.D.; Bailey, O.D.; Wasmoen, T. Prevention of persistent infection in calves by vaccination of dams with noncytopathic type-1 modified-live bovine viral diarrhea virus prior to breeding. Am J Vet Res. 2003, 64, 530–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbanks, K.K.; Rinehart, C.L.; Ohnesorge, C.; Loughin, M.M.; Chase, C.C.L. Evaluation of fetal protection against experimental infection with type 1 and type 2 bovine viral diarrhea virus after vaccination of the dam with a bivalent modified-live virus vaccine. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2004, 225, 1898–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficken, M.D.; Ellsworth, M.A.; Tucker, C.M.; Cortese, V.S. Effects of modified-live bovine viral diarrhea virus vaccines containing either type 1 or types 1 and 2 BVDV on heifers and their offspring after challenge with noncytopathic type 2 BVDV during gestation. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2006, 228, 1559–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, H.R.; Eicken, K.; Grummer, B.; Kenklies, S.; Oguzoglu, T.C.; Moennig, V. Foetal protection against bovine virus diarrhoea virus after two-step vaccination. J Vet Med Ser B. 2002, 49, 489–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulton RW, Johnson BJ, Briggs RE, Ridpath JF, Saliki JT, Confer AW, et al. Challege with Bovine viral diarrhea virus by exposure to persistently infected calves: Protection by vaccination and negative results of antigen testing in nonvaccinated acutely infected calves. Can J Vet Res. 2006, 70, 121–7.

- Grooms, D.L.; Bolin, S.R.; Coe, P.H.; Borges, R.J.; Coutu, C.E. To Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus Following To Cattle. 2007, 68, 1417–22.

- Newcomer, B.W.; Walz, P.H.; Givens, M.D.; Wilson, A.E. Efficacy of bovine viral diarrhea virus vaccination to prevent reproductive disease: A meta-analysis. Theriogenology. 2015, 83, 360–365e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newcomer, B.W.; Givens, D. Diagnosis and Control of Viral Diseases of Reproductive Importance: Infectious Bovine Rhinotracheitis and Bovine Viral Diarrhea. Vet Clin North Am - Food Anim Pract. 2016, 32, 425–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beer, M.; Hehnen, H.R.; Wolfmeyer, A.; Poll, G.; Kaaden, O.R.; Wolf, G. A new inactivated BVDV genotype I and II vaccine An immunisation and challenge study with BVDV genotype I. Vet Microbiol. 2000, 77, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, G.A.; Daly, R.F.; Chase, C.C. Influence of Modified Live Vaccines on Reproductive Performance in Beef Cattle. Range Beef Cow Symp. 2017;:75–83.

- Kalaycioglu, A.T. Bovine viral diarrhoea virus (bvdv) diversity and vaccination. a review. Vet Q. 2007, 29, 60–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germain, R.N. The ins and outs of antigen processing. Nature. 1986, 322, 687–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, J.R.; Shilleto, R.W.; Williams, J.; Alexander, D.C.S. Prevention of transplacental infection of bovine foetus by bovine viral diarrhoea virus through vaccination. Arch Virol. 2002, 147, 2453–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platt, R.; Widel, P.W.; Kesl, L.D.; Roth, J.A. Comparison of humoral and cellular immune responses to a pentavalent modified live virus vaccine in three age groups of calves with maternal antibodies, before and after BVDV type 2 challenge. Vaccine. 2009, 27, 4508–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platt, R.; Coutu, C.; Meinert, T.; Roth, J.A. Humoral and T cell-mediated immune responses to bivalent killed bovine viral diarrhea virus vaccine in beef cattle. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2008, 122, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platt, R.; Kesl, L.; Guidarini, C.; Wang, C.; Roth, J.A. Comparison of humoral and T-cell-mediated immune responses to a single dose of Bovela® live double deleted BVDV vaccine or to a field BVDV strain. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2017;187 December 2016:20–7.

- Zimmerman, A.D.; Boots, R.E.; Valli, J.L.; Chase, C.C.L. Evaluation of protection agianst virulent bovine viral diarrhea virus type 2 in calves that had maternal antibodies and were vaccinated with a modified-live vaccine. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2006, 228, 1757–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Romero N, Arias CF, Verdugo-Rodríguez A, López S, Valenzuela-Moreno LF, Cedillo-Peláez C, et al. Immune protection induced by E2 recombinant glycoprotein of bovine viral diarrhea virus in a murine model. Front Vet Sci. 2023;10.

- Wang S, Yang G, Nie J, Yang R, Du M, Su J, et al. Recombinant Erns-E2 protein vaccine formulated with MF59 and CPG-ODN promotes T cell immunity against bovine viral diarrhea virus infection. Vaccine. 2020, 38, 3881–91.

- Chung, Y.C.; Cheng, L.T.; Zhang, J.Y.; Wu, Y.J.; Liu, S.S.; Chu, C.Y. Recombinant E2 protein enhances protective efficacy of inactivated bovine viral diarrhea virus 2 vaccine in a goat model. BMC Vet Res. 2018, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, G.; Marconi, P.; Periolo, O.; La Torre, J.; Alvarez, M.A. Immunocompetent truncated E2 glycoprotein of bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) expressed in Nicotiana tabacum plants: A candidate antigen for new generation of veterinary vaccines. Vaccine. 2012, 30, 4499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecora A, Malacari DA, Perez Aguirreburualde MS, Bellido D, Nuñez MC, Dus Santos MJ, et al. Development of an APC-targeted multivalent E2-based vaccine against Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus types 1 and 2. Vaccine. 2015, 33, 5163–71.

- Carlsson, U.; Alenius, S.; Sundquist, B. Protective effect of an ISCOM bovine virus diarrhoea virus (BVDV) vaccine against an experimental BVDV infection in vaccinated and non-vaccinated pregnant ewes. Vaccine. 1991, 9, 577–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruschke, C.J.M.; Van Oirschot, J.T.; Van Rijn, P.A. An experimental multivalent bovine virus diarrhea virus E2 subunit vaccine and two experimental conventionally inactivated vaccines induce partial fetal protection in sheep. Vaccine. 1999, 17, 1983–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury SI, Pannhorst K, Sangewar N, Pavulraj S, Wen X, Stout RW, et al. Bohv-1-vectored bvdv-2 subunit vaccine induces bvdv cross-reactive cellular immune responses and protects against bvdv-2 challenge. Vaccines. 2021, 9, 1–30.

- Luo, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Ankenbauer, R.G.; Nelson, L.D.; Witte, S.B.; Jackson, J.A.; et al. Construction of chimeric bovine viral diarrhea viruses containing glycoprotein E rns of heterologous pestiviruses evaluation of the chimeras as potential marker vaccines against, B. V.D.V. Vaccine. 2012, 30, 3843–8. [Google Scholar]

- El-Attar, L.M.R.; Thomas, C.; Luke, J.; Williams, J.A.; Brownlie, J. Enhanced neutralising antibody response to bovine viral diarrhoea virus (BVDV) induced by DNA vaccination in calves. Vaccine. 2015, 33, 4004–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koethe S, König P, Wernike K, Pfaff F, Schulz J, Reimann I, et al. A synthetic modified live chimeric marker vaccine against bvdv-1 and bvdv-2. Vaccines. 2020, 8, 1–23.

- Takahashi, H.; Takeshita, T.; Berzofsky, J.A. Induction of CDS + cytotoxic T purified HIV -1 envelope. Nature. 1990;344 April:873–5.

- Snider M, Garg R, Brownlie R, van den Hurk J V. , Hurk S van DL van den. The bovine viral diarrhea virus E2 protein formulated with a novel adjuvant induces strong, balanced immune responses and provides protection from viral challenge in cattle. Vaccine. 2014, 32, 6758–64.

- Pecora A, Malacari DA, Pérez Aguirreburualde MS, Bellido D, Escribano JM, Dus Santos MJ, et al. Development of an enhanced bovine viral diarrhea virus subunit vaccine based on E2 glycoprotein fused to a single chain antibody which targets to antigen-presenting cells. Rev Argent Microbiol. 2015, 47, 4–8.

- Bellido D, Baztarrica J, Rocha L, Pecora A, Acosta M, Escribano JM, et al. A novel MHC-II targeted BVDV subunit vaccine induces a neutralizing immunological response in guinea pigs and cattle. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2021, 68, 3474–81.

- Aguirreburualde MSP, Gómez MC, Ostachuk A, Wolman F, Albanesi G, Pecora A, et al. Efficacy of a BVDV subunit vaccine produced in alfalfa transgenic plants. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2013, 151, 315–24.

- Sadat, S.M.A.; Snider, M.; Garg, R.; Brownlie, R.; van Drunen Littel-van den Hurk, S. Local innate responses and protective immunity after intradermal immunization with bovine viral diarrhea virus E2 protein formulated with a combination adjuvant in cattle. Vaccine. 2017, 35, 3466–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, C.; Young, N.J.; Heaney, J.; Collins, M.E.; Brownlie, J. Evaluation of efficacy of mammalian and baculovirus expressed E2 subunit vaccine candidates to bovine viral diarrhoea virus. Vaccine. 2009, 27, 2387–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia S, Huang X, Li H, Zheng D, Wang L, Qiao X, et al. Immunogenicity evaluation of recombinant Lactobacillus casei W56 expressing bovine viral diarrhea virus E2 protein in conjunction with cholera toxin B subunit as an adjuvant. Microb Cell Fact. 2020, 19, 1–20.

- Mody KT, Mahony D, Cavallaro AS, Zhang J, Zhang B, Mahony TJ, et al. Silica vesicle nanovaccine formulations stimulate long-term immune responses to the Bovine Viral Diarrhoea Virus E2 protein. PLoS One. 2015, 10, 1–16.

- Mahony D, Cavallaro AS, Mody KT, Xiong L, Mahony TJ, Qiao SZ, et al. In vivo delivery of bovine viral diahorrea virus, E2 protein using hollow mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Nanoscale. 2014, 6, 6617–26.

- Wang, L.; Sunyer, J.O.; Bello, L.J. Fusion to C3d Enhances the Immunogenicity of the E2 Glycoprotein of Type 2 Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus. J Virol. 2004, 78, 1616–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Vaccines name | Types | Dose(ml) | RA | Booster | Used During pregnancy | Genotypes | Strains | Subtypes | Biotypes | Manufacturers | Website |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bovi-Shield GOLD® IBR-BVD | MLV | 2ml | SC/IM | 1 year | No | BVDV1 & 2 | NADL | 1a | ncp | Zoetis | www.zoetis.com |

| Bovela | MLV | 2ml | IM | 1year | Yes | BVDV1& 2 | KE-9 & NY_93 | 1a/2a | ncp | Boehringer | www.vetmedica.de |

| Bovidec | IV | 4ml | SC | 1year | No | BVDV 1 | KY1203 | NA | ncp | Zoetis | www.zoetis.com |

| Bovilis® BVD | IV | 2ml | IM | 1 year | Yes | BVDV1 | C-86 | 1a | cp | Zoetis | www.zoetis.com |

| ONE SHOT® BVD | IV | 2ml | SC | 1year | No | BVDV1 & 2 | NA | NA | NA | Zoetis | www.zoetis.com |

| PESTIGARD® | IV | 2ml | SC | Yes | BVDV | NA | NA | NA | Zoetis | www.zoetis.com | |

| BOVI-SHIELD GOLD FP 5 | IV | 2ml | IM | 1year | No | BVDV1 &2 | NADAL/53637 | 1a/2a | cp | Zoetis | www.zoetis.com |

| CattleMaster GOLD FP 5 | IV | 2ml | SC | 1year | Yes | BVDV1 & 2 | 5960/53637 | 1a/2a | cp | Zoetis | www.zoetis.com |

| CATTLEMASTER 4 | IV | 2ml | IM | 1year | Yes | BVDV1 | 5960/6309 | 1a/1 | ncp/cp | Zoetis | www.zoetis.com |

| Elit 4 | IM | 5ml | IM | 1year | Yes | BVDV1 | Singer | 1a | cp | Boehringer | www.vetmedica.de |

| Master Guard 10 HB | MLV/IV | 3ml | IM/SC | 1year | Yes | BVD1 & 2 | C24V | 1a | cp | Elanco | elanco@elanco.com |

| Triangel 5 | IV | 2ml | IM/SC | 1 year | Yes | BVDV1& 2 | Singer/5912 | 1a/2a | cp/cp | Boehringer | www.vetmedica.de |

| Vira Shield 6 + VL5 HB | IV | 5ml | SC | 1year | Yes | BVDV1 &2 | K12/GL 760/TN131 | 1a/1a | cp/ncp/cp | Novarties | elanco@elanco.com |

| Express 5 | MLV | 2ml | 1year | Yes | BVDV 1& 2 | Singer | 1a/2c | cp/ncp/cp | Boehringer | www.vetmedica.de | |

| Pyramid 4 | MLV | 2ml | SC/IM | 1year | No | BVDV1 & 2 | Singer | 1a | cp | Boehringer | www.vetmedica.de |

| Titanium 5 | MLV | 2ml | SC | 1year | Yes | BVDV1 &2 | C24V/296 | 1a/2c | cp | Elanco | elanco@elanco.com |

| TRIANGLE® 4+PH-K | IV | 5ml | SC | 1year | Not tested | BVD1 | Singer | 1a | cp | Boehringer | www.vetmedica.de |

| Antigen | Adjuvants | Vaccine Types | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| tE2 | Montanide ISA 70 SEPPIC® and (Al(OH)3Hydrogel®) | Subunit | [134,135] |

| rE2 | ISA 61 VG | Recombinant | [131] |

| E2 | Immunostimulating complexes (ISCOMs) | Recombinant | [136] |

| E2 | cholera toxin B subunit (ctxB) | Recombinant | [132] |

| E2,NS2-3 | MONTANIDETM ISA 201 VG adjuvant | Subunit | [21] |

| E2 | NA | Subunit | [137] |

| E2 and flag-tagged Erns | NA | Subunit | [138] |

| Erns | NA | Marker vaccine | [139] |

| Erns | NA | DNA | [140] |

| Npro_Erns | NA | Chimeric vaccines | [141] |

| Npro,E2 and NS2-3 | BenchMark-Vaxliant | Mosaic vaccines | [22] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).