1. Introduction

Worldwide, the major cause of peripartum and maternal mortality is post-partum hemorrhage (PPH) [

1]. The highest burden of this is among women in low-income countries [

2]. PPH is the cause of mortality in >50% of the 140,000 maternal mortality cases every year, and most of these occur within a day of delivery i.e., due to primary PPH [

3,

4]. There is a PPH-related mortality every 4 min. Despite the prevalence, there is limited knowledge about the risk factors and extent of PPH. PPH can be caused by inadequate blood coagulation system, injury in the genital tract, retained tissues inside the uterus, and majorly due to uterine atony [

5]. Uterine atony is defined as the failure of myometrial cells in the corpus uteri to contract after delivery, which is normally induced by the release of endogenous oxytocin, making it the principal cause of PPH and among the top 5 causes of maternal mortality [

6,

7]. Some of the common risk factors identified include intra-uterine fetal death, cesarean births, induction of labor, not using prophylaxis for PPH (such as uterotonics), genital tract injuries, preterm births, advanced maternal age, grand multiparity, being primigravida, fetal macrosomia, multiple pregnancies and a history of PPH [

8,

9,

10].

The traditional definition of PPH is the loss of blood after vaginal delivery which exceeds 500ml or 1,000ml in cesarean sections [

11]. In most of the studies [

8,

9,

10], the estimation of blood loss is the main indicator of PPH, however, they used the method of visually evaluating blood loss which has a huge margin of human error and inaccuracy [

12]. According to a systematic review [

13], this visual evaluation of PPH has its pros such as the absence of cost, real-time results, and feasibility. However, it has its cons as well, major among them is its inaccuracy when severe PPH or higher loss of blood takes place. This is a critical matter as it is under detection and can lead to severe clinical reparations. According to Borovac-Pinheiro et al. [

14] the definition of PPH needs revisions as it is inadequate for a condition that is the cause of death in more than 85,000 women per year.

PPH can be prevented given proper preventative measures have been taken by identifying risk factors in the early stage of pregnancy [

10]. Knowledge regarding these risk factors will also help identify needed public health interventions [

6]. Therefore, this study aims to find the correlation between risk factors of PPH and the incidence of PPH in vaginal deliveries. The significance of this study is that it will promote preventive measures undertaken by healthcare providers in the antenatal and intrapartum periods so that early prophylaxis can be started. This in turn will prevent maternal morbidity and mortality.

2. Materials and Methods

The present study is an observational cohort study. The study was conducted in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Jagannath Hospital, Bhubaneswar, between March 2020 and October 2021. The sample size was calculated to be 239 in the study. After providing information and obtaining informed consent, 239 women with normal vaginal delivery were included in the study. The study used various exclusion criteria to remove potential bias due to any underlying disease. The exclusion criteria are given as;

Obstetrics (Gestational age < 32 wk, Prolonged labor, Preeclampsia, Eclampsia, Vaginal instrumental deliveries)

Non-obstetrics (H/o Asthma, H/o Epilepsy, H/o Heart disease, H/o Kidney disease, H/o Jaundice, Coagulation disorder)

All women received active management of the third stage of labor (AMTSL) where they were given either 0.2mg intravenous Ergometrine or 600 μg of Misoprostol as a prophylaxis to prevent PPH immediately after the birth of the baby. Women with any contraindication to these drugs were also excluded. Furthermore, the side effects of these drugs were also noted. Following this, controlled cord traction (CCT) was performed after the signs of placental separation were observed, and the uterine fundus was massaged.

The blood loss was estimated by using the gravimetric method wherein all blood-soaked drapes were collected in a plastic tray during labor. After the bleeding stopped, the tray and its contents were weighed using an analytical balance. For this experiment, the mean weight of 1 ml of blood was considered 1.06 grams.

Detailed past medical history of these patients was obtained to identify the occurrence of past PPH in previous pregnancies, systematic diseases like heart disease, hypertension, bronchial asthma, and other risk factors. The amount of blood loss, length of the third stage of labor, laboratory parameters such as Hb%, packed cell volume (PCV), etc., and general clinical conditions were obtained in the participants. The incidence of PPH was also noted and recorded in the prepared performa. The amount of blood loss was estimated from readings in the blood collection drape, clinically, and also by comparing values of hemoglobin (Hb%) and hematocrit (PCV) from the second post-delivery day blood sample with values in late pregnancy or at admission. Additionally, a record of the vitals such as blood pressure, temperature, and pulse were obtained just before the birth of the baby, every 15 mins (till 1 hour), at 30 mins (till 2 hours), and then after 4, 8, 12, 16 and 24 hours.

The statistical analysis of the study included a chi-square test for finding an association between the risk factors and the occurrence of PPH in women with vaginal delivery. Also, the frequency and descriptive statistics of all the observed variables were estimated. The statistical software used was Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 27 and the significant value was taken at <0.05. Linear regression was run to study the relationship between the incidence of PPH and its risk factors.

3. Results

There were a total of 239 patients recruited out of which, only 2 (<1%) were above 40 years, 6 (2.5%) were below 20 years and the majority 87(36.4%) were between 25-29 years. Based on gravidity status, the majority of them 93(38.9%) were primigravida, followed by 48(20.1%) second gravida, and the least 3(1.3%) were in seventh and 3(1.3%) were in eighth gravida and above. Based on parity, majority 113(47.3%) had zero parity, whereas, the least 2(<1%) had parity more than 5. These findings can be seen in

Table 1. It also demonstrates the risk factors for PPH found in the patients across all age groups. Among the risk factors, the most common was anemia 32 (13.4%). Other common factors were grand multiparity 9 (3.8%) and hypotension 8 (3.4%).

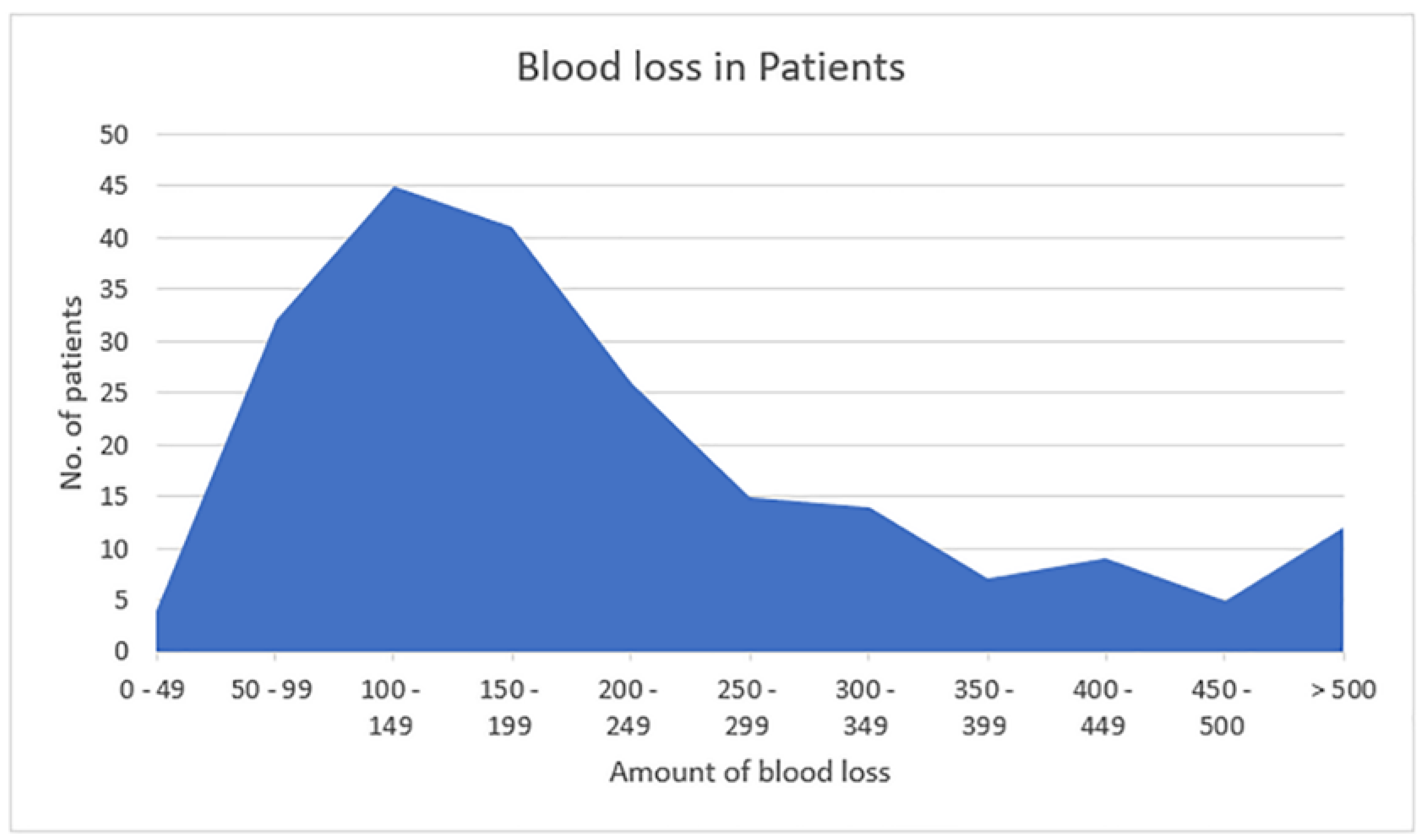

The amount of blood loss was also calculated among the patients (

Figure 1). Here, the majority of the patients 45 (18.9%) had blood loss between 100 to 150 ml, whereas, the least number of patients [4 (1.7%)] had blood loss between 0 to 49 ml. However, 11 (4.6%) patients had blood loss of more than 500 ml i.e., postpartum hemorrhage.

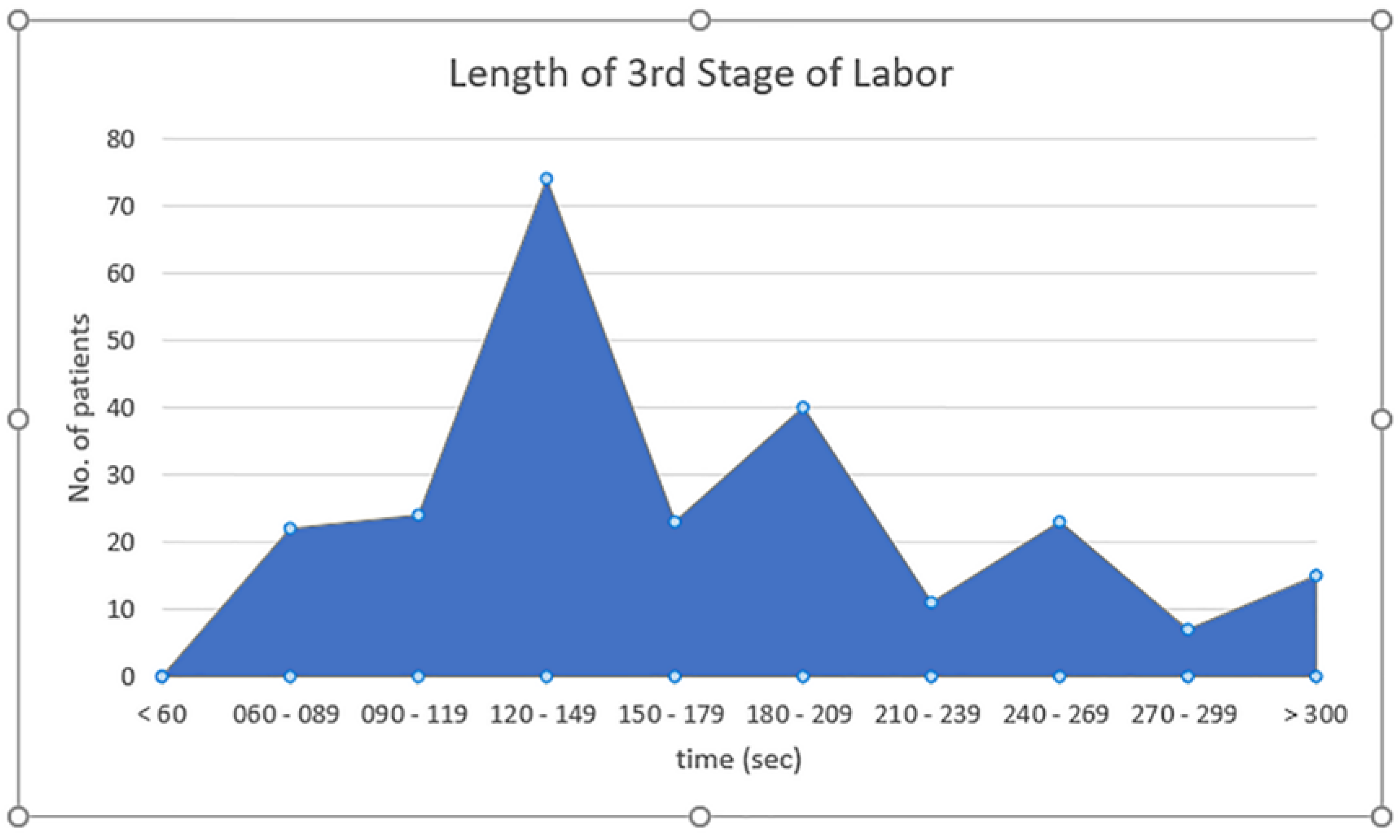

Figure 2 demonstrates the length of 3rd stage of labor. The majority of the patients 74 (31%) had 120 to 149 seconds length of the third stage of labor, while none had less than 60 secs. The majority of the patients (67.3%) had 3rd stage of labor period between 90 to 209 secs.

Change in Hemoglobin (HB) was majorly seen to be 0-0.5 gm% in 161 (67.4%). Whereas, 15 (6.2%) patients had more than 1 to more than 5 gm% change. Change in Packed cell Volume (PCV) was highest seen in 177 (74%) patients that had 1-2% change. More than 5% change was seen in 10 (4.2%) patients (

Table 2).

Table 3 reports the frequency and percentage of risk factors and occurrence of PPH. Patients with the risk of grand multiparity had an incidence of PPH in 33.33% of cases. Whereas, those who had a previous history of PPH also had an incidence in 33.33% of cases. The highest incidence was seen in patients with a risk factor of low-lying placenta, where, 2 patients had this risk factor among which 1 (50%) had an incidence of PPH. A total of 11 patients had PPH, and almost half of them 5 (45.5%) had no risk factor.

The occurrence of PPH when compared between groups of women with and without risk factors, was statistically significant (p=0.012) (

Table 4).

The linear regression analysis reveals that the risk factors have a statistically significant, moderate positive effect on the incidence of PPH, with a correlation coefficient (R) of 0.512 (

Table 5). This suggests that as the risk factors increase, there is a moderate increase in the incidence of PPH. The model’s explanatory power, indicated by the R Square value of 0.262, shows that approximately 26.2% of the variance in PPH incidence can be accounted for by the included risk factors.

Table 6 provides the ANOVA results, demonstrating the overall fit of the linear regression model. The F-statistic of 7.298, accompanied by a significance level (p-value) of 0.000, indicates that the regression model is statistically significant. This means that the risk factors together have a significant impact on the incidence of PPH.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to find a correlation between risk factors and incidence of PPH in normal vaginal deliveries. The majority of the participants were in the 25-29 years age group and were primigravida. The majority of PPH cases had no risk factors, whereas those with risk factors, twin pregnancy, low-lying placenta, grand multipara, and previous history of PPH were notable, despite the use of uterotonics such as Ergometrine and Misoprostol.

The results of this study are similar to one conducted in Uganda between 2013 to 2014 where PPH was seen with multiple pregnancies which had an adjusted OR of 7.66, macrosomia had an adjusted OR of 2.14 and HIV had an adjusted OR of 2.26 all at 95% CI.6 However, as in this study, none of the participants were diagnosed with HIV-positive serostatus, and no correlation between HIV and PPH could be assessed. Twin pregnancy is more associated with peripartum factors leading to PPH compared to singleton pregnancies [

15]. During twin pregnancy, the uterus is overdistended which leads to impairment in postpartum myometrial contractility and can enhance uterine atony. Additionally, uterine blood flow and maternal blood volume also increase in multiple gestation for the provision of additional fetal, uterine, and placental tissues [

16,

17]. However, despite these factors, clinically significant PPH occurs in only among few cases with multiple or twin pregnancies, making it unclear to determine how to correctly identify high-risk patients with certainty in this population. According to Blitz et al. [

18] decreasing the cesarean delivery, optimizing PPH parameters and comorbid conditions in mothers can decrease the risk of PPH.

According to a systematic review conducted by Dehzi et al. [

19] 5146 pregnancies were identified with placenta previa of which 22.3% had PPH (95% CI 15.8–28.7%). Comparatively, in this study the incidence was higher, however, as there were very few cases with placenta previa, this could have led to an increased incidence rate. The overlying of the placenta at the endocervical is characterized as placenta previa, which in obstetrics is considered the most feared fetal-neonatal and maternal complication [

20]. The placenta previa may be caused by uterine scarring due to endometrial damage, which can become complicated by incursion of villi outside the decidua basalis and lead to placenta increta or accrete [

21]. Placenta increta often leads to unexpected complications, increased blood loss, or maternal mortality [

22]. Therefore, there is an increased chance of PPH in expecting mothers with placenta previa. However, in this study, there were no placenta accrete, or increta.

In a study by Akhtar et al. [

23], PPH was found in 5.44% of women with grand multipara, where the leading cause found was atonic uterus. Comparatively, only 3.7% of women in this study were grand multipara and 33.33% among them had PPH. Women who have delivered 5 or more term babies (after 28 weeks) with a weight of more than 500gm are characterized as grand multipara or even ‘dangerous multipara’, as it has been linked with multiple complications in pregnancy and delivery [

24]. Previous studies indicate that its incidence is very high in developing countries (18.5%) compared to developed countries (2-4%) [

25].

However, PPH was also found in patients with low-risk factors. This indicates that PPH can occur in the absence of high-risk factors. To combat that, the attending staff should be vigilant and equipped to handle the cases of unexpected PPH incidents. This safety precaution can decrease the maternal mortality rate.

The study was a multicenter study that was conducted over a long period which increases its generalizability factor. However, the sample size was small which gave even fewer patients with risk factors which might have slightly increased the percentages of incidence (e.g., low-lying placenta). Future studies on a large sample size should be conducted over a targeted population of women with risk factors to further understand its mechanism and true incidence rate in the targeted population. Additionally, the skill level of the healthcare providers should also be assessed so that variability as a result of this confounder can be controlled.

In this study, PPH was found in patients with risk factors of twin pregnancy, placenta previa, grand multipara, and previous history of PPH despite giving prophylaxis and uterotonics. This warrants the need for a thorough investigation of risk factors to provide adequate management and monitoring to prevent PPH and maternal mortality. However, almost half the cases occurred in women without any risk factors. The occurrence of PPH when compared between groups of women with risk factors and groups without risk factors, was not statistically significant. Therefore, there is a need for the identification of all possible risk factors as well as better predictive models for the occurrence of PPH. Maternity units should be vigilant for the occurrence of PPH and prepared for appropriate timely management, irrespective of the presence or absence of known risk factors and the type of prophylaxis used.

5. Conclusions

Postpartum hemorrhage is the leading cause of maternal and peripartum deaths worldwide. The highest burden of this is among women in low-income countries. This study highlights that while certain risk factors such as twin pregnancy, low-lying placenta, grand multiparity, and previous history of PPH are significantly associated with the occurrence of PPH, a substantial proportion of cases occur in the absence of identifiable risk factors. This underscores the importance of universal vigilance and preparedness in managing normal vaginal deliveries to mitigate the risk of PPH, regardless of the presence of known risk factors.

Supplementary Materials

None.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, R.D., S.S.K and S.S ; methodology, S.S.K.,R.D, S.S., S.N.B, H.A.U and KFA; software, R.D. and S.S.K. ; validation, S.S.K.,R.D, S.S., S.N.B, H.A.U and KFA; formal analysis, S.S.K.,R.D.; investigation, R.D. S.S.K.,S.S. and S.N.B; resources, S.S.K.,R.D and S.S.; data curation, S.S.K.,R.D., ., S.N.B and H.A.U ; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.K. ,R.D. and S.S.; writing—review and editing, , S.S.K.,R.D., S.S., S.N.B, H.A.U and KFA ; visualization, S.S.K. and R.D ; supervision, S.S.K.,R.D., S.S., S.N.B, H.A.U and KFA ; project administration, R.D and S.S.K; Funding acquisition-None. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Jagannath Hospital, Odisha, India – No- 1024/2020-1/4/20).”.

Informed Consent Statement

“Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.”.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Say, L.; Chou, D.; Gemmill, A.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Moller, A.B.; Daniels, J.; et al. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2014, 2, e323–e333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, N. Postpartum Hemorrhage: Causes and Outcome. J Neonatal Surg 2019, 24, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, K.S.; Wojdyla, D.; Say, L.; Gülmezoglu, A.M.; Van Look, P.F. WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: a systematic review. Lancet 2006, 367, 1066–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khorrami, N.; Stone, J.; Small, M.J.; Stringer, E.M.; Ahmadzia, H.K. An overview of advances in global maternal health: From broad to specific improvements. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2019, 146, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutomski, J.E.; Byrne, B.M.; Devane, D.; Greene, R.A. Increasing trends in atonic postpartum hemorrhage in Ireland: an 11-year population-based cohort study. BJOG: An Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2011, 119, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ononge, S.; Mirembe, F.; Wandabwa, J.; Campbell, O.M. Incidence and risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage in Uganda. Reprod Health 2016, 13, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberg, A.S.; Hernandez-Diaz, S.; Palmsten, K.; Almqvist, C.; Bateman, B.T. Patterns of recurrence of postpartum hemorrhage in a large population-based cohort. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014, 210, 229–e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin: clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists number 76, October 2006, postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol 2006, 108, 1039–1047. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, P.; Patel, A.; Van Hook, J.W. Uterine Atony. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sosa, C.G.; Althabe, F.; Belizán, J.M.; Buekens, P. Risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage in vaginal deliveries in a Latin-American population. Obstet Gynaecol 2009, 113, 1313–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newsome, J.; Martin, J.G.; Bercu, Z.; Shah, J.; Shekhani, H.; Peters, G. Postpartum hemorrhage. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol 2017, 20, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lertbunnaphong, T.; Lapthanapat, N.; Leetheeragul, J.; Hakularb, P.; Ownon, A. Postpartum blood loss: visual estimation versus objective quantification with a novel birthing drape. Singapore Med J 2016, 57, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natrella M, Di Naro E, Loverro M, Benshalom-Tirosh N, Trojano G, Tirosh D, et al. The more you lose the more you miss: accuracy of postpartum blood loss visual estimation. A systematic review of the literature. Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2018, 31, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borovac-Pinheiro A, Pacagnella RC, Cecatti JG, Miller S, El Ayadi AM, Souza JP, et al. Postpartum hemorrhage: new insights for definition and diagnosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018, 219, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer MS, Berg C, Abenhaim H, Dahhou M, Rouleau J, Mehrabadi A, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and temporal trends in severe postpartum hemorrhage. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013, 209, 449–e1. [Google Scholar]

- Hytten, F. Blood volume changes in normal pregnancy. Clin Haematol 1985, 14, 601–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christenson, R.K.; Prior, R.L. Uterine blood flow and nutrient uptake during late gestation in ewes with different numbers of fetuses. J Anim Sci 1978, 46, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blitz MJ, Yukhayev A, Pachtman SL, Reisner J, Moses D, Sison CP, et al. Twin pregnancy and risk of postpartum hemorrhage. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2020, 33, 3740–3745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan D, Xia Q, Liu L, Wu S, Tian G, Wang W, et al. The incidence of postpartum hemorrhage in pregnant women with placenta previa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one 2017, 12, e0170194. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, D.; Wu, S.; Wang, W.; Xin, L.; Tian, G.; Liu, L.; Feng, J.; Guo, X.; Liu, Z. Prevalence of placenta previa among deliveries in Mainland China: A PRISMA-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2016, 95, e5107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adere, A.; Mulu, A.; Temesgen, F. Neonatal and maternal complications of placenta praevia and its risk factors in Tikur Anbessa specialized and Gandhi memorial hospitals: Unmatched case-control study. J. Pregnancy 2020, 2020, 5630296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Liao, H.; Duan, L.; Wei, Q.; Zeng, W. Uterine packing during cesarean section in the management of intractable hemorrhage in central placenta previa. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2012, 285, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, R.; Sanodia Afridi, R.K.; Malik, N.N. Frequency of maternal and fetal outcome in grand multipara women. KJMS 2018, 11, 376–379. [Google Scholar]

- Mgaya, A.H.; Massawe, S.N.; Kidanto, H.L.; Mgaya, H.N. Grand multiparity: is it still a risk in pregnancy? . BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Performance, monitoring & accountability 2020 (PMA) ETHIOPIA: Addis Ababa University’s School of Public Health at the College of Health Sciences (AAU/SPH/CHS) 2014.Available at: https://www.pmadata.org/sites/default/files/data_product_results/PMA2020-Ethiopia-R6-FP-Brief.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).