Submitted:

10 January 2025

Posted:

10 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Setting and Population

2.2. Sample Size, Study Sampling and Data Collection

2.3. Laboratory Procedures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Population Characteristics in the Household Surveys

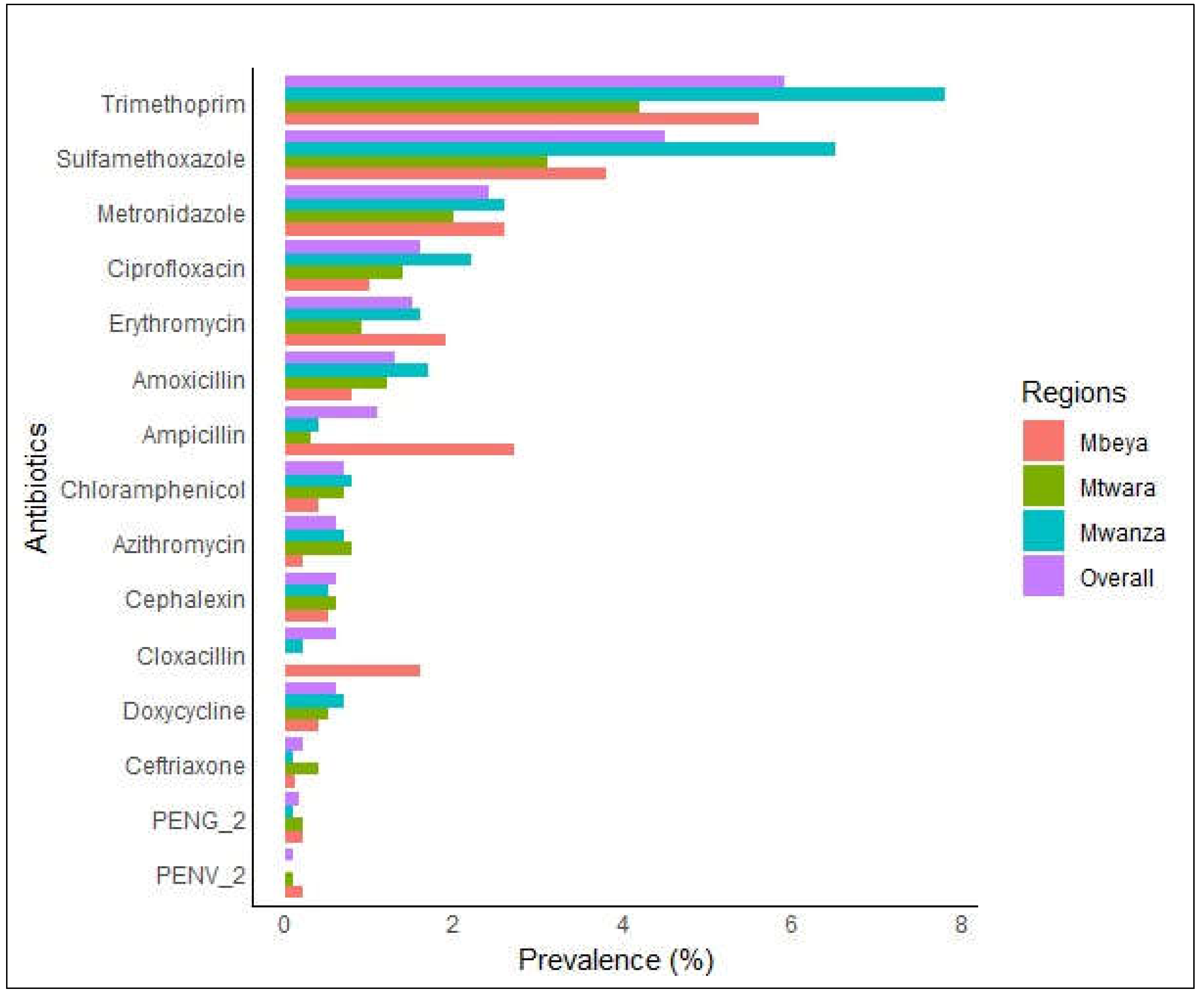

3.2. Prevalence of Antibiotics in the Blood of the Surveyed Population

3.3. Factors Associated with the Presence of Antibiotics

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

References

- Abou Heidar, N. F., Degheili, J. A., Yacoubian, A. A. & Khauli, R. B. Management of urinary tract infection in women: A practical approach for everyday practice. Urology annals, 2019, 11, 339.

- Ahmed, S. K., Hussein, S., Qurbani, K., Ibrahim, R. H., Fareeq, A., Mahmood, K. A. & Mohamed, M. G. Antimicrobial resistance: Impacts, challenges, and future prospects. Journal of Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health, 2024, 2, 100081.

- Ampadu, H. H. , Asante, K. P., Bosomprah, S., Akakpo, S., Hugo, P., Gardarsdottir, H., Leufkens, H. G. M., Kajungu, D. & Dodoo, A. N. O. Prescribing patterns and compliance with World Health Organization recommendations for the management of severe malaria: a modified cohort event monitoring study in public health facilities in Ghana and Uganda. Malaria Journal, 2019, 18, 36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Browne, A. J., Chipeta, M. G., Haines-Woodhouse, G., Kumaran, E. P. A., Hamadani, B. H. K., Zaraa, S., Henry, N. J., Deshpande, A., Reiner, R. C., JR., Day, N. P. J., et al. Global antibiotic consumption and usage in humans, 2000–18: a spatial modelling study. The Lancet Planetary Health 2021, 5, e893–e904.

- D'acremont, V., Kahama-Maro, J., Swai, N., Mtasiwa, D., Genton, B. & Lengeler, C. Reduction of anti-malarial consumption after rapid diagnostic tests implementation in Dar es Salaam: a before-after and cluster randomized controlled study. Malar J, 2011, 10, 107.

- D'acremont, V., Kahama-Maro, J., Swai, N., Mtasiwa, D., Genton, B. & Lengeler, C. Reduction of anti-malarial consumption after rapid diagnostic tests implementation in Dar es Salaam: a before-after and cluster randomized controlled study. Malaria Journal, 2011, 10, 1-16.

- Gallay, J., Mosha, D., Lutahakana, E., Mazuguni, F., Zuakulu, M., Decosterd, L. A., GENTON, B. & Pothin, E. Appropriateness of malaria diagnosis and treatment for fever episodes according to patient history and anti-malarial blood measurement: a cross-sectional survey from Tanzania. Malaria journal, 2018, 17, 1-13.

- Gallay, J., Pothin, E., Mosha, D., Lutahakana, E., Mazuguni, F., Zuakulu, M., Decosterd, L. A. & Genton, B. Predictors of residual antimalarial drugs in the blood in community surveys in Tanzania. PloS one, 2018, 13, e0202745.

- Gallay, J., Prod’hom, S., Mercier, T., Bardinet, C., Spaggiari, D., Pothin, E., Buclin, T., Genton, B. & Decosterd, L. A. LC–MS/MS method for the simultaneous analysis of seven antimalarials and two active metabolites in dried blood spots for applications in field trials: Analytical and clinical validation. Journal of pharmaceutical and biomedical analysis, 2018, 154, 263-277.

- Goodman, C. , Tougher, S., Shang, T. J. & Visser, T. Improving malaria case management with artemisinin-based combination therapies and malaria rapid diagnostic tests in private medicine retail outlets in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Plos one, 2024, 19, e0286718. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guo, H., Hildon, Z. J.-L., Lye, D. C. B., Straughan, P. T. & Chow, A. 2022. The Associations between Poor Antibiotic and Antimicrobial Resistance Knowledge and Inappropriate Antibiotic Use in the General Population Are Modified by Age. Antibiotics, 11, 47.

- Hopkins, H. , Bruxvoort, K. J., Cairns, M. E., Chandler, C. I., Leurent, B., Ansah, E. K., Baiden, F., Baltzell, K. A., Björkman, A. & Burchett, H. E. 2017. Impact of introduction of rapid diagnostic tests for malaria on antibiotic prescribing: analysis of observational and randomised studies in public and private healthcare settings. bmj,.

- Iskandar, K. , Molinier, L., Hallit, S., Sartelli, M., Hardcastle, T. C., Haque, M., Lugova, H., Dhingra, S., Sharma, P. & Islam, S. 2021. Surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in low-and middle-income countries: a scattered picture. Antimicrobial Resistance & Infection Control,.

- Kanan, M. , Ramadan, M., Haif, H., Abdullah, B., Mubarak, J., Ahmad, W., Mari, S., Hassan, S., Eid, R. & Hasan, M. Empowering Low-and Middle-Income Countries to Combat AMR by Minimal Use of Antibiotics: A Way Forward. Antibiotics,.

- Lotto, T. , Renggli, S., Kaale, E., Masanja, H., Ternon, B., Décosterd, L. A., D'acremont, V., Genton, B. & Kulinkina, A. V. 2024. Prevalence and predictors of residual antibiotics in children’s blood in community settings in Tanzania. Clinical Microbiology and Infection.

- Mabilika, R. J. , Shirima, G. & Mpolya, E. 2022. Prevalence and Predictors of Antibiotic Prescriptions at Primary Healthcare Facilities in the Dodoma Region, Central Tanzania: A Retrospective, Cross-Sectional Study. Antibiotics,.

- Makanjuola, R. O. & Taylor-Robinson, A. W. 2020. Improving accuracy of malaria diagnosis in underserved rural and remote endemic areas of sub-Saharan Africa: a call to develop multiplexing rapid diagnostic tests. Scientifica,.

- Makenga, G. , Baraka, V., Francis, F., Nakato, S., Gesase, S., Mtove, G., Madebe, R., Kyaruzi, E., Minja, D. T. & Lusingu, J. P. 2023. Effectiveness and safety of intermittent preventive treatment with dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine or artesunate–amodiaquine for reducing malaria and related morbidities in schoolchildren in Tanzania: a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Global Health, 2023, 11, e1277–e1289. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Masquelier, B., Hug, L., Sharrow, D., You, D., Hogan, D., Hill, K., Liu, J., Pedersen, J. & Alkema, L. Global, regional, and national mortality trends in older children and young adolescents (5-14 years) from 1990 to 2016: an analysis of empirical data. Lancet Glob Health, 2018, 6, e1087-e1099.

- Matindo, A. Y. , Kalolo, A., Kengia, J. T., Kapologwe, N. A. & MUNISI, D. Z. 2022. The role of community participation in planning and executing malaria interventions: experience from implementation of biolarviciding for malaria vector control in Southern Tanzania. BioMed Research International, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mbwasi, R. , Mapunjo, S., Wittenauer, R., Valimba, R., Msovela, K., Werth, B. J., Khea, A. M., Nkiligi, E. A., Lusaya, E. & Stergachis, A. 2020. National consumption of antimicrobials in Tanzania: 2017–2019. Frontiers in Pharmacology,.

- Ministry of health (moh) [tanzania mainland], m. O. H. M. Z. , national bureau of statistics (nbs), office of the chief government statistician (ocgs), and icf. 2023. Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey and Malaria Indicator Survey 2022 Key Indicators Report. Dodoma, Tanzania, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: MoH, NBS, OCGS, and ICF.

- Ministry of health, c. D. , gender, elderly and children (mohcdgec) [tanzania mainland], ministry of health (moh) [zanzibar], national bureau of statistics (nbs), office of the chief government statistician (ocgs), and icf. 2016. Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey and Malaria Indicator Survey (TDHS-MIS) 2015-16. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: MoHCDGEC, MoH, NBS, OCGS, and ICF.

- Murray, C. J. , Ikuta, K. S., Sharara, F., Swetschinski, L., Aguilar, G. R., Gray, A., Han, C., Bisignano, C., Rao, P. & Wool, E. 2022. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. The Lancet, 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar]

- Ndaki, P. M. , Mushi, M. F., Mwanga, J. R., Konje, E. T., Mugassa, S., Manyiri, M. W., Mwita, S. M., Ntinginya, N. E., Mmbaga, B. T., Keenan, K., et al. 2022. Non-prescribed antibiotic dispensing practices for symptoms of urinary tract infection in community pharmacies and accredited drug dispensing outlets in Tanzania: a simulated clients approach. BMC Primary Care, 2022, 23, 287. [Google Scholar]

- Ndaki, P. M. , Mushi, M. F., Mwanga, J. R., Konje, E. T., Ntinginya, N. E., Mmbaga, B. T., Keenan, K., Sabiiti, W., Kesby, M., Benitez-Paez, F., et al. 2021. Dispensing Antibiotics without Prescription at Community Pharmacies and Accredited Drug Dispensing Outlets in Tanzania: A Cross-Sectional Study. Antibiotics (Basel),.

- Ndaki, P. M. , Mwanga, J. R., Mushi, M. F., Konje, E. T., Fredricks, K. J., Kesby, M., Sandeman, A., Mugassa, S., Manyiri, M. W., Loza, O., et al. Practices and motives behind antibiotics provision in drug outlets in Tanzania: A qualitative study. PLoS One, 2023, 18, e0290638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organization, W. H. 2014. Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance, World Health Organization.

- Patton, G. C. , Sawyer, S. M., Santelli, J. S., Ross, D. A., Afifi, R., Allen, N. B., Arora, M., Azzopardi, P., Baldwin, W., Bonell, C., et al. Our future: a Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet, 2016, 387, 2423–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rautman, L. H., Eibach, D., Boateng, F. O., Akenten, C. W., Hanson, H., Maiga-Ascofaré, O., May, J. & Krumkamp, R. Modeling pediatric antibiotic use in an area of declining malaria prevalence. Scientific Reports, 2024, 14, 16431.

- Rousham, E. K., Nahar, P., Uddin, M. R., Islam, M. A., Nizame, F. A., Khisa, N., Akter, S. S., Munim, M. S., Rahman, M. & Unicomb, L. Gender and urban-rural influences on antibiotic purchasing and prescription use in retail drug shops: a one health study. BMC Public Health, 2023, 23, 229.

- Schröder, W., Sommer, H., Gladstone, B. P., Foschi, F., Hellman, J., Evengard, B. & Tacconelli, E. 2016. Gender differences in antibiotic prescribing in the community: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother, 71, 1800-6.

- Sun, R., Yao, T., Zhou, X., Harbarth, S. & Lin, L. Non-biomedical factors affecting antibiotic use in the community: a mixed-methods systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2022, 28, 345-354.

- Van de Maat, J., de Santis, O., Luwanda, L., Tan, R. & Keitel, K. Primary Care Case Management of Febrile Children: Insights From the ePOCT Routine Care Cohort in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Frontiers in pediatrics, 2021, 9, 626386.

| Variable | Type | Definition |

| Outcome | ||

| Antibiotics in blood | Binary | Presence of any antibiotic(s) in the blood equal or above the limits of quantification |

| Participant information | ||

| Age (years) | Ordinal | Participant’s age, categorized as 0-4, 5-14, 15 – 24 and 25+ |

| Sex | Categorical | Categorized as male or female |

| Time to nearest government health care facilities | Ordinal | Time required to reach nearby government health facility, categorized as < 15 min, 15 min < 1hour, >=1, unknown |

| Time to nearest nongovernment hospital | Categorical | Time required to reach nearby nongovernment health facility, categorized as < 15 min, 15 min < 1hour, >=1, unknown |

| Time to nearest medical shop | Categorical | Time required to reach nearby medical shop, categorized as < 15 min, 15 min < 1hour, >=1, unknown |

| mRDT results on site | Categorical | Rapid malaria diagnostic test taken during the survey categorized as Positive, negative, not valid, missing |

| History of fever in the past 14 days | Categorical | Self-reported fever in past 14 days prior to the survey, categorized as yes, no, doesn’t know |

| Sought care for this fever | Categorical | Whether care was sought in case of fever, categorized as yes, no, doesn’t know |

| Time taken to travel to the provider | Categorical | Time required to reach health care provider, categorized as < 15 min, 15 min < 1hour, >=1, unknown |

| Malaria blood test performed | Categorical | Malaria diagnostic test performed when seeking care, categorized as? |

| Malaria test results | Categorical | Reported result of the malaria diagnostic test performed when seeking care, categorized as positive, negative & not valid |

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage |

| Total Participants | 3036 | 100 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1359 | 44.80 |

| Female | 1674 | 55.10 |

| Missing | 3 | 0.10 |

| Age (Years) | ||

| 0-4 | 531 | 17.50 |

| 5 – 14 | 839 | 27.60 |

| 15-24 | 428 | 14.10 |

| 25+ | 1185 | 39.00 |

| Time to Government Health Facility | ||

| < 15 minutes | 811 | 26.70 |

| 15 minutes to < 1 hour | 1748 | 57.60 |

| 1 hour or more | 386 | 12.70 |

| Missing | 3 | 0.10 |

| Time to Non-Government Health Facility | ||

| < 15 minutes | 474 | 15.60 |

| 15 minutes to < 1 hour | 1041 | 34.30 |

| 1 hour or more | 431 | 14.20 |

| Missing | 3 | 0.10 |

| Time to Medicine Shops | ||

| < 15 minutes | 1353 | 44.60 |

| < 1 hour | 1262 | 41.60 |

| ≥ 1 hour | 418 | 8.50 |

| Missing | 3 | 0.10 |

| mRDT Result | ||

| Positive | 512 | 16.90 |

| Negative | 2500 | 82.20 |

| Missing | 24 | 2 |

| Had Fever in the Previous 2 Weeks | ||

| Yes | 494 | 16.30 |

| No | 2539 | 83.50 |

| Missing | 3 | 0.10 |

| Had Antimalarial in Blood | ||

| Yes | 599 | 19.7 |

| No | 2435 | 80.2 |

| Missing | 3 | 0.1 |

| Regions | ||

| Mbeya | 933 | 30.80 |

| Mtwara | 1000 | 32.90 |

| Mwanza | 1100 | 36.20 |

| Missing | 3 | 0.10 |

| Variables |

Total participants N (%) |

Participants with antibiotic in the blood | ||||

| N (%) | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||||

| ORs | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |||

| Total | 3036 | 438 (14.4) | ||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1359 (44.8) | 168 (12.4) | Ref | 1 | ||

| Female | 1674 (55.1) | 269 (16.1) | 1.33 (1.08 - 1.64) | 0.008 | 1.30 (1.05 –1.61) | 0.017 |

| Missing | 3 (0.1) | 1 (33.3) | ||||

| Age (Years) | ||||||

| 0-4 | 531 (17.5) | 91 (17.1) | Ref | -- | ||

| 5-14 | 839 (27.6) | 100 (11.9) | 0.64 (0.47-0.88) | 0.006 | 0.66 (0.48-0.91) | 0.011 |

| 15 - 24 | 428 (14.1) | 54 (12.6) | 0.65 (0.45-0.94) | 0.022 | 0.67 (0.46-0.98) | 0.039 |

| 25+ | 1185 (39.0) | 190 (16.0) | 0.94 (0.71 -1.25) | 0.682 | 0.93 (0.70-1.23) | 0.598 |

| Time to Government Health Facility | ||||||

| < 15 minutes | 811 (26.7) | 115 (14.2) | Ref | -- | -- | -- |

| 15 minutes to < 1 hour | 1748 (57.6) | 268 (15.3) | 1.13 (0.88 – 1.46) | 0.329 | 1.15 (0.87 – 1.51) | 0.322 |

| 1 hour or more | 386 (12.7) | 54 (11.4) | 0.75 (0.49 – 1.13) | 0.171 | 0.91 (0.59 – 1.39) | 0.659 |

| Missing | 3 (2) | 1 (33.3) | ||||

| Non-Government HF time | ||||||

| < 15 minutes | 474 (15.6) | 92 (19.4) | Ref | -- | -- | -- |

| 15 minutes to <1 hour | 1041 (34.3) | 185 (17.8) | 1.01 (0.74 – 1.37) | 0.967 | 1.03 (0.74-1.44) | 0.869 |

| 1 hour or more | 431 (14.2) | 160 (10.5) | 0.60 (0.40 – 0.92) | 0.018 | 0.61 (0.42-0.88) | 0.024 |

| Missing | 3 (2) | 1 (33.3) | ||||

| Time to medicine shops | ||||||

| < 15 minutes | 1353 (44.6) | 218 (16.1) | Ref | -- | -- | -- |

| <1 hour | 1262 (41.6) | 177 (14.0) | 0.98 (0.77 – 1.25) | 0.891 | 0.95 (0.73 – 1.24) | 0.721 |

| >=1 hour | 418 (8.5) | 42 (10.0) | 0.69 (0.44 – 1.10) | 0.118 | 0.89 (0.59 – 1.36) | 0.600 |

| Missing | 3 (2) | 1 (33.3) | ||||

| mRDT result | ||||||

| Positive | 512 (16.9) | 49 (9.6) | Ref | -- | -- | -- |

| Negative | 2500 (82.2) | 381 (15.2) | 1.57 (1.13 – 2.18) | 0.007 | 1.46 (1.04 – 2.06) | 0.029 |

| Missing | 24 (2) | 8 (33.3) | ||||

| Had fever in the previous 2 weeks | ||||||

| Yes | 494 (16.3) | 86 (17.4) | Ref | -- | -- | -- |

| No | 2539 (83.5) | 351 (13.8) | 0.75 (0.57 – 0.98) | 0.034 | 0.78 (0.59 – 1.03) | 0.083 |

| Missing | 3 (2) | 1 (33.3) | ||||

| Had antimalarial in blood | ||||||

| Yes | 599 (19.7) | 111 (18.5) | 1.48 (1.16-1.89) | 0.002 | 1.37 (1.06 – 1.77) | 0.014 |

| No | 2435 (80.2) | 327 (13.4) | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Missing | 3 (0.1) | 0 | ||||

| Regions | ||||||

| Mbeya | 933 (30.8) | 136 (14.6) | -- | -- | -- | |

| Mtwara | 1000 (32.9) | 112 (11.2) | 0.79 (0.51 – 1.22) | 0.291 | 0.87 (0.58 – 1.28) | 0.476 |

| Mwanza | 1100 (36.2) | 189 (17.2) | 1.30 (0.85 – 1.98) | 0.222 | 1.17 (0.81 – 1.70) | 0.397 |

| Missing | 3 (0.1) | 1 (33.3) | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).