1. Introduction

Obesity and type 2 diabetes constitute global epidemics and are crucial underlying factors in a host of chronic diseases that play a causal role in excess morbidity and mortality, particularly in the industrialized world [

1]. For decades, advice intended to combat obesity has revolved around repeated exhortations to “eat less and move more” and yet the incidence of obesity and its associated pathologies continues to spiral upward in an alarming trajectory despite these admonitions [

2,

3]. The unsatisfactory results of this conventional advice aimed at preventing and reversing obesity can be at least partially attributed to its erroneous underlying assumption which holds that dietary energy intake and energy expenditure (EE) are independent variables and thus can be manipulated at will in efforts to alter body composition without regard to complex biochemical regulatory pathways governing energy homeostasis [

4,

5,

6]. This is evidenced by the observation that changes in body weight invariably result in changes in energy expenditure in a process known as adaptive thermogenesis [

7,

8,

9]. While the exact origin of the collective failure of efforts to interrupt current trends toward ever-increasing rates of obesity remains a source of vigorous debate [

10], the necessity of finding new and effective methods to prevent and treat obesity is irrefutable.

Adipose tissue (AT) has long been recognized as a regulator of nutrient status given its capacity to store excess dietary substrate as triacylglycerols (TGs) in the fed state and export fatty acids and glycerol during fasting [

11,

12]. However, the discovery of secretory factors specifically derived from adipocytes in the mid-1990s has led to an appreciation of adipose tissue beyond its function solely as a storage site for excess dietary substrate [

13,

14]. Indeed, the roughly concurrent discoveries of leptin, adiponectin, TNF-α, adipsin, and other adipocyte-derived factors termed “adipokines” has given rise to a surge in interest in adipose tissue as a

bona fide endocrine organ situated at the nexus of energy homeostasis [

15].

The recognition that adipocytes play an indispensable role in metabolic function also provided an impetus for the development of pharmacologic agents targeting adipose tissue specifically in efforts to improve insulin sensitivity and blood glucose control [

16,

17]. The anti-diabetic drugs targeting adipose tissue exert their effects primarily by modulating the activity of the transcription factor PPAR-γ, which is the master transcriptional regulator of adipogenesis [

18]. These PPAR-γ agonists constitute the thiazolidinediones (TZDs), which have potent insulin sensitizing effects but are known to result in weight gain and can also have adverse effects on cardiac function [

19]. Given that cardiovascular disease (CVD) is one of the leading causes of death globally [

20,

21] and that obesity-related metabolic dysfunction is a critically important contributor to CVD [

22], there has never been a more urgent time to increase understanding of the complex relationships between adipose tissue of all types and cardiovascular function [

23].

The discovery that functional brown adipose tissue (BAT) is present in adult humans [

24] led to a groundswell of research interest in this unique tissue. BAT had been long recognized as a physiological defense against cold temperatures in small mammals and human infants given its capacity to generate heat by dissipating the normally tight coupling between substrate oxidation and ATP synthesis [

25]. However, in recent years an appreciation of BAT as a tissue with secretory function has developed in parallel with our current understanding of WAT as an endocrine organ with potent effects on whole body metabolic function [

15,

26,

27]. Notably, several studies have indicated that diminished BAT activity and non-functional BAT are contributors to obesity and cardiometabolic syndrome [

28,

29,

30]. Conversely, expansions in BAT mass and increases in the circulating levels of BAT-derived secreted molecules (batokines) have been demonstrated by a growing literature to beneficially affect key parameters such as glucose homeostasis, insulin sensitivity, and total energy expenditure, all of which confer resistance to the development of obesity-related metabolic dysfunction [

31,

32,

33].

While the discovery of functional BAT in adult humans constituted a major leap forward in our understanding of adipose tissue in general as a nexus of metabolic control in concert with the actions of WAT, the recognition of BAT-derived secreted factors as modulators of cardiovascular function is a relatively newly emerging field [

34,

35,

36,

37]. Recent studies have identified several batokines that modulate the heart in a generally favorable manner; these include FGF21, neuregulin 4 (NRG4), 12,13-diHOME, and microRNAs specifically derived from BAT [

38]. This review will focus specifically on these batokines for which experimental evidence exists demonstrating a heretofore relatively unknown function of BAT as a tissue acting in a cardioprotective manner and will aim to briefly summarize the state of the field in understanding the mechanisms by which BAT-derived humoral factors could act advantageously in combating CVD. The new recognition of BAT as a cardioprotective tissue is certain to stimulate vigorous investigation in the future, with a view towards targeting BAT expansion and enhanced secretory function as a therapeutic strategy in combating cardiometabolic disease.

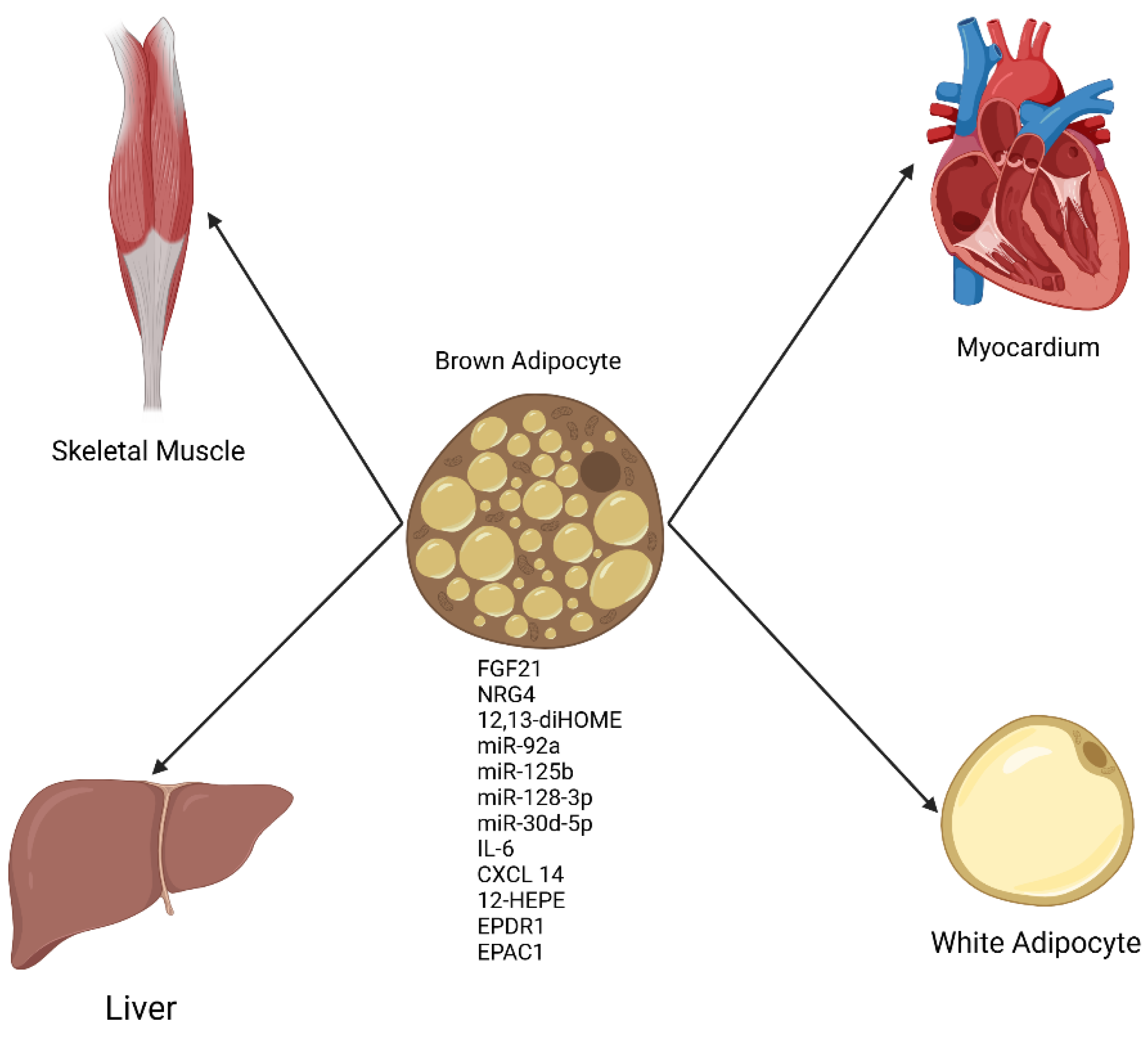

Figure 1.

General schematic of factors secreted from BAT (Batokines) with effects on multiple organs. Batokines appear to be uniformly beneficial in organ systems studied thus far [

38]. Created in BioRender.

Figure 1.

General schematic of factors secreted from BAT (Batokines) with effects on multiple organs. Batokines appear to be uniformly beneficial in organ systems studied thus far [

38]. Created in BioRender.

2. Batokines Affecting Cardiac Function

2.1. FGF21

Fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) is expressed primarily in the liver, although recent evidence inidicates that this peptide is also produced by cardiomyocytes and BAT [

39,

40,

41]. FGF21 has received intense attention in the scientific literature in the context of metabolic syndrome due to the generally beneficial effects observed on systemic parameters such as glucose homeostasis, insulin sensitivity, and systemic inflammation [

42]. Moreover, FGF21 is involved in the adaptive responses to prolonged fasting and ketogenic diets, which include enhanced insulin sensitivity and cognitive effects [

43,

44,

45]. FGF21 is therefore viewed as a key integrator of a diverse range of physiological responses to states of energy restriction, many of which underlie desirable alterations in metabolism that confer resistance to clinical manifestations of the metabolic syndrome.

While the centrality of FGF21 as a factor underlying physiological adaptations to challenges in whole-body energy status has been widely recognized, appreciation of the role of FGF21 as an important mediator of many of the beneficial effects of increased activity of BAT thermogenesis has only recently emerged. This is particularly relevant in terms of cardiac function since the discovery that the heart both produces FGF21 in cardiomyocytes and is in turn stimulated by FGF21 derived from distant tissues; therefore FGF21 exerts endocrine, paracrine, and intracrine effects on the cardiovascular system in a complex system of inter-organ crosstalk [

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51]. As early as 2013, transgenic mice studies demonstrated that FGF21 KO mice suffered maladaptive cardiac hypertrophy and dilatation in response to isoproterenol challenge and that the maladaptive responses were reversed by treatment with exogenous FGF21 [

51]. More recent studies indicate that BAT is a source of FGF21 [

40] and that FGF21 derived specifically from BAT exerts a protective effect on the heart by acting as a preventative against deleterious cardiac remodeling in response to hypertension in mice [

41]. Experiments from this study revealed a crucial role for FGF21 from interscapular BAT in attenuating hypertensive cardiac remodeling which was intertwined with BAT adenosine A

2A receptor signaling, which was obligatory in mediating FGF21 protection against pathological hypertensive cardiac remodeling. Moreover, this study showed that the beneficial cardiac effects of BAT-derived FGF21 were dependent on AMPK/PGC1α pathway activation which was necessary for induction of FGF21 secretion from iBAT. The conclusions of this study were consolidated by the finding that administration of recombinant FGF21 in iBAT depleted mice improved cardiac remodeling and that intact BAT-specific A

2A receptor signaling was required to diminish cardiac damage in hypertensive mice [

41]. Importantly, BAT-derived FGF21 has also recently been demonstrated as a cardioprotective factor in C57BL/6J mice subjected to myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury (I/R), which is a major causative factor in myocardial damage resulting from infarction [

52]. Data from a study by Ding et. al. provided evidence from in vitro experiments that the protective effect of BAT-derived FGF21 in the context of dexmedetomidine administration was modulated by the Keap/Nrf2 pathway, whereby FGF21 stimulation of Nrf2 signalling attenuated the oxidative stress and inflammation typically observed in myocardial I/R injury [

53].

| Year |

First

Author

|

Citation |

FGF21 Effects on Cardiac Function (Systemic or Direct) |

Model |

| 2010 |

Hondares |

39 |

↑Hepatic FGF21 expression, ↑thermogenic activation of neonatal brown fat |

Neonatal mice |

| 2011 |

Hondares |

40 |

↑ FGF21 expression and release in BAT, ↑ systemic protective effects |

Mice |

| 2018 |

Ruan |

41 |

↑BAT-derived FGF21 protects against maladaptive cardiac remodeling in hypertension |

Mice with induced hypertension |

| 2016 |

Fisher |

42 |

↑ Glucose homeostasis ↑ insulin sensitivity, ↓ Systemic inflammation |

General Physiological studies |

| 2013 |

Bookout |

43 |

↑ Adaptive responses to fasting, ↑ Insulin sensitivity, ↑ Cognitive effects |

General studies on fasting and metabolism |

| 2014 |

Laeger |

44 |

↑ FGF21 signaling during protein restriction, ↑ endocrine adaptation to dietary changes |

Mice and rats on low-protein diets |

| 2024 |

Khan |

45 |

↑ FGF21-driven metabolic adaptations, ↑ behavioral motivation changes in response to diets |

Mice; Studies on brain reward signaling and dietary preferences |

| 2013 |

Planavilla |

51 |

↓ Maladaptive cardiac hypertrophy and dilatation in FGF21 KO mice, reversal with exogenous FGF21 |

FGF21 KO Mice subjected to isoproterenol-induced cardiac stress |

2.2. NRG4

Neuregulin 4 (NRG4), a lesser-known but emerging batokine secreted by brown adipose tissue (BAT), has received significant attention for its key role in cardioprotection through its multifaceted involvement in energy metabolism and homeostasis [

54]. Initially detected in the pancreas [

55], NRG4 belongs to the epidermal growth factor family and preferentially binds to the receptor tyrosine kinase ErbB4, predominantly expressed in adipose tissue [

56]. Recent studies point to NRG4’s potential cardioprotective properties, indicating its crucial role in mitigating the adverse impacts of obesity, insulin resistance, and metabolic dysfunction on heart health [

57]. Insulin resistance, defined by disrupted insulin-mediated glucose metabolism, is recognized as an early indicator of cardiovascular disease [

58]. Strong evidence supports the role of BAT in alleviating insulin resistance [

59], with NRG4 playing a pivotal role in enhancing glucose metabolism and reducing inflammation in metabolic tissues [

54]. Hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp studies have demonstrated that NRG4 increases glucose metabolism in peripheral tissues, significantly improving systemic insulin sensitivity [

60]. Furthermore, NRG4 reduces chronic inflammation in white adipose tissue by decreasing macrophage accumulation in high-fat diet-induced obese mice, further supporting its role in improving metabolic health [

61].

Obesity significantly contributes to cardiovascular disease risk by dysregulating lipid metabolism, leading to the ectopic accumulation of lipids in various tissues and promoting cardiovascular complications [

62,

63]. Cai et al. demonstrate that mRNA expression of NRG4 is reduced in adipose tissue in human models of obesity [

64], while Chen et al. observe similar findings in mouse models [

60]. Activating NRG4 in adipocytes has been shown to enhance adipose tissue angiogenesis, suggesting a pro-angiogenic role for NRG4 [

65]. Furthermore, overexpressing NRG4 through hydrodynamic gene delivery significantly reduces diet-induced obesity in mice [

61], demonstrating NRG4’s therapeutic potential and contribution to cardiovascular disease reduction.

NRG4’s role in metabolic regulation forms the foundation of its external cardioprotective effects; however, it also exerts a direct, internal cardioprotective influence. In vivo and in vitro studies have revealed its ability to restore cardiac function and attenuate pathological remodeling [

66]. Specifically, in an isoproterenol-induced cardiac remodeling model, Nrg4 treatment was shown to significantly restore cardiac function, mitigate pathological hypertrophy, and suppress myocardial fibrosis [

66]. These therapeutic effects were mechanistically linked to its modulation of inflammatory responses and apoptosis via activation of the AMPK/NF-κB signaling pathway [

66]. The AMPK/NF-κB pathway primarily suppresses inflammation and apoptosis, thereby preventing tissue damage and reducing pathological remodeling of cardiac tissue [

66]. Complementary to this, the AMPK/Nrf2 pathway plays a pivotal role in regulating oxidative stress and ferroptosis by enhancing antioxidant defenses [

67]. In a diabetic myocardial injury model, NRG4 alleviated high-glucose-induced ferroptosis in cardiomyocytes by activating the AMPK/Nrf2 signaling pathway [

67]. Notably, inhibition of this pathway diminished NRG4’s beneficial effects, emphasizing the importance of AMPK signaling in cardiovascular protection. Both AMPK-mediated pathways have been linked to the amelioration of cardiovascular disease.

At the vascular level, NRG4 has been shown to prevent endothelial dysfunction and vascular inflammation [

68]. In a mouse model, BAT-specific Nrg4 deficiency exacerbated atherosclerosis, whereas restoring Nrg4 levels reversed these effects, demonstrating its crucial role in maintaining vascular health [

68]. Beyond experimental models, clinical studies have identified profound serum NRG4 levels as a promising biomarker for cardiovascular protection [

69]. Lower serum NRG4 has been associated with early detection of vascular abnormalities, such as increased carotid intima-media thickness and atherosclerotic plaque, particularly in individuals at high risk of subclinical cardiovascular disease [

69,

70]. Reduced NRG4 levels have also been observed in patients with coronary artery disease [

71]. In line with these findings, a recent Mendelian randomization study found that elevated serum NRG4 plays a protective role in atherosclerosis, mediating lowered LDL-C levels linked to a reduced risk of peripheral atherosclerosis [

72]. By enhancing insulin sensitivity, regulating lipid metabolism, and protecting against cardiac remodeling, NRG4 represents a promising therapeutic target in addressing heart disease, particularly in populations affected by obesity and type 2 diabetes [

57,

73]. While NRG4 has demonstrated cardioprotective effects, its exact role in the cardiovascular system is not yet fully understood, and further investigation is needed to uncover its complete potential.

| Year |

First

Author

|

Citation |

NRG4 Cardioprotective Outcomes (Systemic or Direct) |

Model |

| 2017 |

Chen |

[52] |

↑Energy expenditure, ↑Whole-body glucose metabolism, ↑β-oxidation, ↑Glycolysis, ↓Hepatic steatosis, ↓Inflammation (eWAT), |

Nrg4 transgenic obese mice |

| 2016 |

Ma |

[53] |

↓ Diet-induced weight gain, ↓ Inflammation, ↓ Macrophage infiltration, ↑BAT thermogenesis, ↑ Insulin sensitivity, ↓Hepatic steatosis, ↓Nrg4 mRNA (AT, pre-delivery) |

Hydrodynamic gene delivery of Nrg4 in obese mice |

| 2016 |

Cai |

[56] |

↓ Serum Nrg4, ↑MetS, ↑Blood glucose and BP |

Human (obese) |

| 2018 |

Nugroho |

[57] |

↑ Adipose tissue angiogenesis, ↑ WAT vasculature, ↑ Systemic metabolic health, ↓ Adipose hypoxia, ↓ Inflammation, ↑ Glucose homeostasis |

Nrg4 transgenic obese mice |

| 2024 |

Wei |

[58] |

↑ Cardiac function, ↓ Cardiac hypertrophy, ↓ Fibrosis, ↓ Cell apoptosis, ↓ Inflammatory factors, ↑ Cardioprotection via AMPK/NF-κB pathway |

ISO-induced myocardial injury in mice |

| 2024 |

Wang |

[59] |

↓ Myocardial injury, ↓Oxidative stress, ↓ Ferroptosis, ↑ AMPK/Nrf2 signaling, ↑ Cardiac function, ↓ Cardiac fibrosis, ↑ Mitochondrial integrity |

Nrg4-Treated T1D Mice |

| 2022 |

Shi |

[60] |

↓ Atherosclerosis, ↓ Vascular inflammation, ↓ Endothelial dysfunction, ↓ Leukocyte homing, ↓ Apoptosis, ↓ Inflammation |

Humans and Mice |

| 2016 |

Jiang |

[62] |

↓ Serum Nrg4 levels associated with ↑ CIMT and carotid plaque, ↑Nrg4 levels associated with ↓ BMI, ↓ Systolic BP, ↓ Total cholesterol |

Human (Obese with CIMT and carotid plaque) |

| 2023 |

Taheri |

[63] |

↓Nrg4 levels in CAD, ↑BMI, ↑Waist circumference ↑Fasting blood glucose, ↑Triglyceride-glucose index |

Human (CAD) |

| 2014 |

Zheng |

[64] |

↓Athereosclerosis, ↓LDL-C levels ↓Peripheral atherosclerosis |

Human |

2.3. 12,13-diHOME

In 2008, Cao and colleagues identified a novel lipid hormone connecting adipose tissue to organism-wide metabolism; these investigators termed this newly discovered hormone “lipokine” [

74]. Recent experiments have provided evidence that a novel lipokine secreted from BAT, 12,13-diHOME (12, 13-dihydroxy 9Z-octadecenoic acid), exerts beneficial cardiac effects [

75,

76]. Interestingly, 12,13-diHOME is increased independently of ambient temperature by a single bout of exercise in humans and mice, with evidence demonstrating that the tissue source of 12, 13-diHOME is BAT, as shown by surgical ablation of interscapular BAT negating the exercise-induced increase in 12,13-diHOME [

77]. These experiments revealed the mechanistic insight that 12,13-diHOME increases skeletal muscle fatty acid uptake and oxidation via induction of genes involved in fatty acid transport and mitochondrial activity and biogenesis. Other experiments demonstrate that 12,13-diHOME treatment increases mobilization of fatty acid transporters CD36 and FATP1 to the membrane in mature brown adipocytes, thereby increasing uptake of fatty acids and setting the stage for increased fat oxidation [

75].Given that exercise is an indispensable cardioprotective modality, the close linkage between exercise and lipokine secretion from BAT indicates that 12,13-diHOME can be thought of as an “exerkine,” a term referring to humoral factors induced by exercise that confer pleiotropic metabolic benefits [

78,

79,

80].

From the perspective of specific cardioprotection, 12, 13-diHOME has been shown in mice to favorably modulate cardiac function directly via increasing mitochondrial respiration, induction of nitric oxide synthase 1 (NOS1), and increasing cardiomyocyte contractility by NOS1-dependent activation of the ryanodine receptor [

76]. These findings were consistent with previous data demonstrating that NOS1 modulation of cardiac contractile function is mediated by calcium cycling via interation with the ryanodine receptor [

81,

82]. Moreover, this study provided evidence that 12,13-diHOME is positively correlated with ejection fraction in human patients with heart disease [

76]. While previous studies have indicated that 12,13-diHOME could be deleterious to cardiac health, the applicability of these results are vitiated by methodological issues, including the use of ex vivo models and high concentrations of 12,13-diHOME that are toxic to cardiomyocytes [

76,

83,

84,

85]. A retrospective study undertaken by Cao and colleagues on T2DM patients with and without acute myocardial infarction (AMI) employed untargeted metabolomics and subsequent validation with ELISA to demonstrate that 12,13-diHOME was elevated in T2DM patients with AMI compared to those who did not suffer AMI [

86]. However, this study is retrospective and correlational therefore it is difficult to impute a causal role for 12,13-diHOME in AMI from these data alone [

86].

Further evidence of beneficial effects of 12,13-diHOME on cardiovascular function was shown in experiments demonstrating a linkage between insulin signaling and differentiation of perivascular progenitor cells (PPCs) into BAT, with conseqential increases in BAT mass and 12,13-diHOME secretion which in turn reduced inflammation and atherosclerosis in mice [

87]. These experiments indicated that inhibition of eNOS by L-NAME resulted in a failure of PPCs to differentiate into beige/brown adipocytes and abrogation of weight loss and beneficial effects on bioenergetics which were reversed by infusion of 12,13-diHOME, which improved endothelial function and decreased atherosclerosis [

87]. These recent results in preclinical studies are encouraging; however, future research in humans with and without diagnosed CVD are needed to more throughly understand the effects of 12,13-diHOME on cardiovascular function.

| Year |

First

Author

|

Citation |

12,13-diHOME Cardioprotective Outcomes (Systemic or Direct) |

Model |

| 2017 |

Lynes |

75 |

↑BAT activity, ↑Fat oxidation, ↑Cold tolerance ↓Serum triglycerides, ↑fatty acid uptake, ↑lipid metabolism |

Human and Mouse |

| 2021 |

Pinckard |

76 |

↑Mitochondrial respiration, ↓Cardiac remodeling, ↑NOS1 activity, ↑Cardiomyocyte contractility, ↑Systolic function, ↑Diastolic function, ↓12,13-diHOME in heart disease, ↑Glucose tolerance, ↑Fatty acid uptake, ↑Ejection fraction |

Human and Mouse |

| 2018 |

Stanford |

77 |

↑Baseline 12,13-diHOME in active individuals, ↑Circulating 12,13-diHOME post-exercise, ↑Fatty acid uptake, ↓RER, ↑Mitochondrial respiration, ↑Fatty acid oxidation |

Human and Mouse |

| 2007 |

Gonzales |

81 |

NOS1 deficiency → ↓RyR2 S-nitrosylation, ↑SR Ca²⁺ leak, ↓SR Ca²⁺ content, ↑ventricular arrhythmias, ↑sudden cardiac death |

Mouse |

| 2022 |

Park |

87 |

↑BAT mass, ↑12,13-diHOME secretion, ↓Inflammation, ↓Atherosclerosis, ↑Endothelial function, ↑Insulin signaling, ↑ Thermogenesis |

Mouse |

2.4. BAT-Derived miRNA Affects Cardiac Function

Small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) are secreted from various tissues upon exposure to physiological and pathological stimuli, whereupon they enter the circulatory system and constitute an important biological mechanism by which diverse organ systems communicate with one another [

88,

89]. Also known as exosomes, sEVs have become acknowledged as playing a major role in regulating inter-organ crosstalk in an expanding literature in which experimental evidence in numerous paradigms indicate that sEVs are obligatory in mediating the beneficial effects of interventions such as exercise [

88,

89,

90,

91,

92]. As our understanding of the pleiotropic benefits of BAT activation expands, it is notable that sEVs are emerging as key mechanistic players mediating the beneficial effects of BAT. This section of the review will summarize the latest findings providing evidence for a specific role of BAT-derived sEVs in cardioprotection, which is a relatively new field of exploration that offers great potential in unraveling the mechanisms by which BAT can communicate not only with the heart but with other distant organs as well.

A seminal set of experiments performed by Zhao and colleagues revealed that a subset of sEVs from BAT exerted potent direct cardioprotective effects of exercise in a model of myocardial infarction/reperfusion (MI/R) injury in mice [

91]. Specifically, the findings of these experiments demonstrated that a particular set of miRNAs contained in the sEVs from BAT (miR-125b-5p, miR128-3p, and miR30d-5p) favorably modulated the heart’s response to MI/R injury via suppression of the proapoptotic MAPK pathway [

91], thereby promoting cardiomyocyte survival. Mechanistic insights from this study from in vivo proof of concept experiments and detailed investigation from in vitro studies interrogated the mechanisms by which the miRNA cargo of the BAT conferred exercise -induced cardioprotection. The data from these experiments revealed that the main biological mechanism by which sEVs from BAT advantageously modulated cardiac response to MI/R injury were by inhibition of several genes in the proapoptotic MAPK and caspase pathways, including Map3k5, Map2k7, and Map2k4. The conclusions of the study were consolidated by data indicating that direct delivery of BAT sEVs into hearts or cardiomyocytes inhibited MAPK pathway activation and that this protective effect was abolished by BAT miRNA inhibitors [

91]. Collectively, the results of these in vitro and in vivo experiments revealed a novel pathway by which the cardiovascular benefits of aerobic exercise are mediated by activation of the BAT secretome, specifically miRNAs encapsulated by sEVs.

The effect of miRNAs on heart function remains complex and is an emerging field of study. A particular miRNA, miR-92a, has been investigated and reveals a complicated relationship with BAT and cardiac function which has yet to be fully unraveled. The circulating levels of miR-92a are negatively correlated with BAT activity in humans; however, currently it is not possible to definitively conclude whether or not miR-92a is an independent causal factor in cardiac pathology [

93,

94,

95,

96]. Chen and colleagues, for example, demonstrated that miR-92a abundance in exosomes was markedly decreased in both humans and mice in conditions with high BAT abundance or activity, such as in mice subjected to cold exposure or cAMP treatment, both of which are known to activate BAT [

96]. Plasma miR-92a levels were also shown to be elevated in patients with diabetes with comcomitant increased expression of the inflammatory factors NF-κB, MCP-1, ICAM-1, and endothelin-1 [

97]. Another study indicated that in a porcine experimental model inhibition of miR-92a resulted in protection against MI/R injury, with improved ejection fraction, left ventricular end-diastolic pressure, and reduced infarct zone size [

94].

While the previously cited studies implicate miR-92a in myocardial damage, drawing definitive conclusions is complicated by a recent study showing that overexpression of miR-92a-5p attenuated myocardial damage in rats with induced diabetic cardiomyopathy [

93]. In these rats, the principal mechanism which conferred cardioprotection was reduction in oxidative stress injury, with reduced apoptosis levels, increased glutathione, reduced malondialdehyde accumulation, and inhibition of MKNK2 expression which in turn reduced activation of p38MAPK signaling [

93]. Taken together, the divergent results of these studies might indicate that a physiological secretion of miR-92a from activated BAT could be cardioprotective, while in a different context this miRNA could be damaging to the heart. Any conclusions currently remain speculative until more detailed mechanistic experiments can be performed that can clarify the biological conditions under which miR-92a acts beneficially versus adversely.

| Year |

First

Author

|

Citation |

MiRNA Cardioprotective Outcomes |

Model |

| 2022 |

Yu |

93 |

↑MiR-92a results: ↑Glutathione level, ↓myocardial oxidative stress, ↓ROS, ↓malondialdehyde, ↓apoptosis, ↓MAPK signaling |

Rats |

| 2022 |

Zhao |

91 |

↑MiR-125a-5p, miR-128-3p, miR-30d-5p results: ↑Protection against MI/R injury, ↓signaling of TRAF3, TRAF6, TNFRSF1B, BAK1, ↓activation of caspases, MAPK pathway, ↓apoptosis |

Mice |

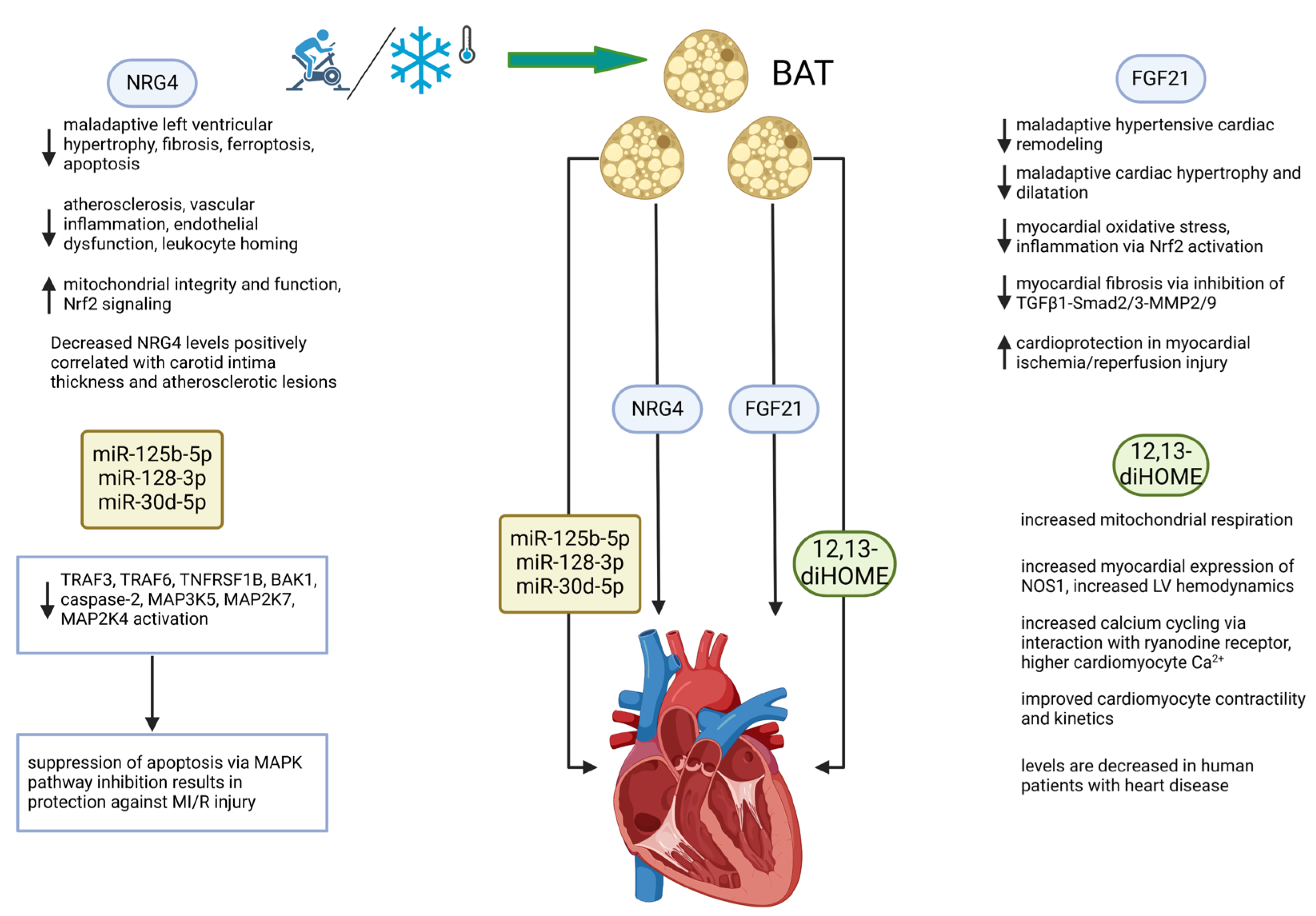

Figure 2.

BAT directly and favorably modifies cardiac function through the secretion of batokines. The BAT secretome operates through at least four types of secreted molecules. These include the proteins FGF21 and NRG4, the lipokine 12,13-diHOME, and a set of miRNAs. Mechanisms of action include those that are indicated under the 4 factors diagrammed. Stimuli that activate BAT include exercise and cold exposure, both of which operate systemically and by direct targeting of multiple organ systems. See list of abbreviations for definitions of abbreviations used in the diagram. Created in BioRender.

Figure 2.

BAT directly and favorably modifies cardiac function through the secretion of batokines. The BAT secretome operates through at least four types of secreted molecules. These include the proteins FGF21 and NRG4, the lipokine 12,13-diHOME, and a set of miRNAs. Mechanisms of action include those that are indicated under the 4 factors diagrammed. Stimuli that activate BAT include exercise and cold exposure, both of which operate systemically and by direct targeting of multiple organ systems. See list of abbreviations for definitions of abbreviations used in the diagram. Created in BioRender.

3. Conclusions and Future Directions

The discovery of functional BAT in humans entailed a profound shift in our understanding of adipose tissue in general as a multifunctional tissue serving not only to store energy substrate but as a thermogenic organ with endocrine, paracrine, and autocrine effects that play key roles mediating interorgan metabolic communication [

15,

98,

99,

100,

101,

102,

103,

104]. BAT has been shown over the last decade to act not solely as a thermogenic organ but as an endocrine organ with pleiotropic effects in distant tissues that appear to be almost uniformly beneficial in all model systems studied thus far [

38]. The mechanisms by which BAT communicates with distant tissues include proteins, lipokines, and exosomes carrying a cargo of miRNAs that alter the metabolic functions of various organs, which, notably, includes the heart [

104].

This review has focused on elements of the BAT secretome which have been shown to affect the heart, specifically FGF21, neuregulin-4, 12,13-diHOME, and exosomes encapsulating miRNAs that exert cardiac effects. Given that CVD continues to be the primary cause of death globally, the urgency of discovering new preventative and therapeutic modalities for CVD is readily apparent [

105]. BAT has received relatively little attention compared to other tissues with endocrine function in terms of its relevance as a cardioprotective organ and it is notable that BAT is activated by exercise, an intervention with irrefutable beneficial effects on the cardiovascular system [

102,

103,

104]. The recognition of BAT as an endocrine organ has stimulated recent investigation into its potential in promoting heart health and the mechanisms by which BAT modulates cardiovascular function are only beginning to be elucidated. The data summarized in this review offer new mechanistic insights into how BAT affects the heart.

BAT modulates cardiovascular function systemically by increasing EE and thereby acting in opposition to the development of obesity and clearing lipids from the circulation, which are two mechanisms by which ectopic lipid accumulation can be abrogated or at least minimized. However, the data from studies summarized in this review provides evidence of a direct line of communication between BAT and the heart, with various beneficial direct effects on the heart specifically and the cardiovascular system more generally. FGF21 specifically of BAT origin protects the heart from maladaptive remodeling in hypertension, myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury and acute myocardial infarction [

41,

51,

52,

53]. NRG4 has been shown to decrease cardiac fibrosis, apoptosis, ferroptosis, oxidative stress, and atherosclerosis, while also inducing protective adaptations including increased mitochondrial function and enhancement of anti-inflammatory activity via Nrf2 signaling [

66,

70,

72,

106,

107]. 12,13-diHOME, a novel lipokine of the oxylipin class, exerts beneficial cardiovascular effects via enhanced calcium cycling with consequent improvements in systolic and diastolic function, with concomitant augmentation of cardiomyocyte shortening and kinetics [

76,

87]. MiRNA contained in small extracellular vesicles also has been shown to favorably modulate cardiac function. Specifically, miR-125b, miR-128-3p, and miR-30d-5p exhibited cardioprotective effects by inhibition of apoptosis in MI/R injury via suppression of the pro-apoptotic MAPK pathway [

91]. While findings are divergent in terms of the effects of miR-92a on the cardiovascular system [

93,

94,

95,

97], one study found that in rats subjected to MI/R injury, overexpression of miR-92a resulted in improved systolic function and reduction of infarct size [

93].

Future research should include both females and males in rodent studies to clarify whether there are sex-specific differences in circulating batokines and responsiveness to batokines in a diverse range of tissues, including the heart [

104]. It is reasonable to hypothesize that sexually dimorphic patterns of batokine activity might exist in humans, considering the evidence that young lean women have a higher percentage of BAT than age-matched young, lean men [

108]. It is an exciting time to study BAT and its effects on cardiometabolic health; many questions remain surrounding the exact interventions utilizing expansion of BAT mass and batokine levels/activity and the techniques available to disentangle the complex interactions between BAT and other organ systems are robustly suited to the task. Exercise and intermittent cold exposure are physiological means by which BAT mass can be expanded and it is reasonable to infer that expansion of BAT would lead to consequent increases in batokines. Modalities such as pharmacological adrenergic stimulation and direct exogenous delivery of BAT derived secretory factors merit further exploration, although the risk of side effects and dosing issues must be carefully considered.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.F.; writing, K.M., S.F., and V.D..; figure preparation, S.F. All authors have read and agreed to the draft of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgements

This work honors the memory of dear friend Mark A. Leonard. (S.F.)

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

12,13-diHOME 12,13-dihydroxy 9Z-octadecenoic acid

AMI acute myocardial infarction

AMPK adenosine 5’-monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase

A2AR adenosine 2a receptor

BAT brown adipose tissue

Batokines brown adipose tissue adipokine

CAD coronary artery disease

CD36 cluster of differentiation 36

CIMT carotid intima media thickness

CVD cardiovascular disease

EE energy expenditure

eWAT epidydimal white adipose tissue

FATP1 fatty acid transport protein 1

FGF21 fibroblast growth factor 21

iBAT interscapular brown adipose tissue

ICAM-1 intercellular adhesion molecule 1

L-NAME N(ω)-nitr-L-arginine methyl ester

MetS metabolic syndrome

MiR micro-RNA

MI/R myocardial ischemia/reperfusion

MKNK2 MAP kinase-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 2

NF-κB nuclear factor kappa B

NOS nitric oxide synthase

eNOS endothelial nitric oxide synthase

iNOS inducible nitric oxide synthase

MAPK mitogen-activated protein kinase

MCP-1 monocyte chemotactic protein 1

Nrf2 nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor

NRG4 neuregulin 4

PPC perivascular progenitor cell

PPAR-γ peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-gamma

ROS reactive oxygen species

RyR ryanodine receptor

sEV small extracellular vesicle

SR sarcoplasmic reticulum

TG triacylglycerol

TNF-α tumor necrosis factor-alpha

TNFRSF tumor necrosis factor super family

TRAF tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor

WAT white adipose tissue

References

- Sattar, N.; Neeland, I.J.; McGuire, D.K. Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease: A New Dawn. Circulation 2024, 149, 1621–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, K.D.; Guo, J. Obesity Energetics: Body Weight Regulation and the Effects of Diet Composition. Gastroenterology 2017, 152, 1718–1727.e1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubáček, J.A. Eat less and exercise more - is it really enough to knock down the obesity pandemia? Physiol Res 2009, 58 Suppl 1, S1–s6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochner, C.N.; Tsai, A.G.; Kushner, R.F.; Wadden, T.A. Treating obesity seriously: when recommendations for lifestyle change confront biological adaptations. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2015, 3, 232–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, K.D.; Chow, C.C. Why is the 3500 kcal per pound weight loss rule wrong? Int J Obes (Lond) 2013, 37, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, K.D.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Kemnitz, J.W.; Klein, S.; Schoeller, D.A.; Speakman, J.R. Energy balance and its components: implications for body weight regulation. Am J Clin Nutr 2012, 95, 989–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, M.; Leibel, R.L. Models of energy homeostasis in response to maintenance of reduced body weight. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2016, 24, 1620–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.J.; Enderle, J.; Bosy-Westphal, A. Changes in Energy Expenditure with Weight Gain and Weight Loss in Humans. Curr Obes Rep 2016, 5, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, M.; Hirsch, J.; Gallagher, D.A.; Leibel, R.L. Long-term persistence of adaptive thermogenesis in subjects who have maintained a reduced body weight. Am J Clin Nutr 2008, 88, 906–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, D.S.; Apovian, C.M.; Aronne, L.J.; Astrup, A.; Cantley, L.C.; Ebbeling, C.B.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Johnson, J.D.; King, J.C.; Krauss, R.M.; et al. Competing paradigms of obesity pathogenesis: energy balance versus carbohydrate-insulin models. Eur J Clin Nutr 2022, 76, 1209–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristancho, A.G.; Lazar, M.A. Forming functional fat: a growing understanding of adipocyte differentiation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2011, 12, 722–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galic, S.; Oakhill, J.S.; Steinberg, G.R. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2010, 316, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halaas, J.L.; Gajiwala, K.S.; Maffei, M.; Cohen, S.L.; Chait, B.T.; Rabinowitz, D.; Lallone, R.L.; Burley, S.K.; Friedman, J.M. Weight-Reducing Effects of the Plasma Protein Encoded by the <i>obese</i> Gene. Science 1995, 269, 543–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherer, P.E.; Williams, S.; Fogliano, M.; Baldini, G.; Lodish, H.F. A novel serum protein similar to C1q, produced exclusively in adipocytes. J Biol Chem 1995, 270, 26746–26749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, E.D.; Spiegelman, B.M. What we talk about when we talk about fat. Cell 2014, 156, 20–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, A.H. Redefining the role of thiazolidinediones in the management of type 2 diabetes. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2009, 5, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, I.; Boudreau, A.; Stephens, J.M. Adipose tissue in health and disease. Open Biol 2020, 10, 200291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tontonoz, P.; Spiegelman, B.M. Fat and beyond: the diverse biology of PPARgamma. Annu Rev Biochem 2008, 77, 289–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrototaro, L.; Roden, M. Insulin resistance and insulin sensitizing agents. Metabolism 2021, 125, 154892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, G.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Johnson, C.O.; Addolorato, G.; Ammirati, E.; Baddour, L.M.; Barengo, N.C.; Beaton, A.Z.; Benjamin, E.J.; Benziger, C.P.; et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990-2019: Update From the GBD 2019 Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020, 76, 2982–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, C.W.; Aday, A.W.; Almarzooq, Z.I.; Anderson, C.A.M.; Arora, P.; Avery, C.L.; Baker-Smith, C.M.; Beaton, A.Z.; Boehme, A.K.; Buxton, A.E.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2023 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023, 147, e93–e621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbone, S.; Canada, J.M.; Billingsley, H.E.; Siddiqui, M.S.; Elagizi, A.; Lavie, C.J. Obesity paradox in cardiovascular disease: where do we stand? Vasc Health Risk Manag 2019, 15, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, X.; Huo, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Bishai, D.M.; Grépin, K.A.; Clarke, P.M.; Chen, C.; Luo, L.; Quan, J. Economic costs attributable to modifiable risk factors: an analysis of 24 million urban residents in China. BMC Med 2024, 22, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virtanen, K.A.; Lidell, M.E.; Orava, J.; Heglind, M.; Westergren, R.; Niemi, T.; Taittonen, M.; Laine, J.; Savisto, N.J.; Enerback, S.; et al. Functional brown adipose tissue in healthy adults. N Engl J Med 2009, 360, 1518–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Bostrom, P.; Sparks, L.M.; Ye, L.; Choi, J.H.; Giang, A.H.; Khandekar, M.; Virtanen, K.A.; Nuutila, P.; Schaart, G.; et al. Beige adipocytes are a distinct type of thermogenic fat cell in mouse and human. Cell 2012, 150, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Garcia-Barrio, M.T.; Chen, Y.E. Brown Adipose Tissue, Not Just a Heater. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2017, 37, 389–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheele, C.; Wolfrum, C. Brown Adipose Crosstalk in Tissue Plasticity and Human Metabolism. Endocr Rev 2020, 41, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cypess, A.M.; Lehman, S.; Williams, G.; Tal, I.; Rodman, D.; Goldfine, A.B.; Kuo, F.C.; Palmer, E.L.; Tseng, Y.H.; Doria, A.; et al. Identification and importance of brown adipose tissue in adult humans. N Engl J Med 2009, 360, 1509–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, R.T.; Shetty, P.S.; James, W.P.; Barrand, M.A.; Callingham, B.A. Reduced thermogenesis in obesity. Nature 1979, 279, 322–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitner, B.P.; Huang, S.; Brychta, R.J.; Duckworth, C.J.; Baskin, A.S.; McGehee, S.; Tal, I.; Dieckmann, W.; Gupta, G.; Kolodny, G.M.; et al. Mapping of human brown adipose tissue in lean and obese young men. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114, 8649–8654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becher, T.; Palanisamy, S.; Kramer, D.J.; Eljalby, M.; Marx, S.J.; Wibmer, A.G.; Butler, S.D.; Jiang, C.S.; Vaughan, R.; Schoder, H.; et al. Brown adipose tissue is associated with cardiometabolic health. Nat Med 2021, 27, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korobkina, E.D.; Calejman, C.M.; Haley, J.A.; Kelly, M.E.; Li, H.; Gaughan, M.; Chen, Q.; Pepper, H.L.; Ahmad, H.; Boucher, A.; et al. Brown fat ATP-citrate lyase links carbohydrate availability to thermogenesis and guards against metabolic stress. Nat Metab 2024, 6, 2187–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedergaard, J.; von Essen, G.; Cannon, B. Brown adipose tissue: can it keep us slim? A discussion of the evidence for and against the existence of diet-induced thermogenesis in mice and men. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2023, 378, 20220220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.T.; Stanford, K.I. Batokines: Mediators of Inter-Tissue Communication (a Mini-Review). Curr Obes Rep 2022, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoonen, R.; Ernande, L.; Cheng, J.; Nagasaka, Y.; Yao, V.; Miranda-Bezerra, A.; Chen, C.; Chao, W.; Panagia, M.; Sosnovik, D.E.; et al. Functional brown adipose tissue limits cardiomyocyte injury and adverse remodeling in catecholamine-induced cardiomyopathy. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2015, 84, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takx, R.A.; Ishai, A.; Truong, Q.A.; MacNabb, M.H.; Scherrer-Crosbie, M.; Tawakol, A. Supraclavicular Brown Adipose Tissue 18F-FDG Uptake and Cardiovascular Disease. J Nucl Med 2016, 57, 1221–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarroya, J.; Cereijo, R.; Gavaldà-Navarro, A.; Peyrou, M.; Giralt, M.; Villarroya, F. New insights into the secretory functions of brown adipose tissue. J Endocrinol 2019, 243, R19–r27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Becera, R.; Santamans, A.M.; Arcones, A.C.; Sabio, G. From Beats to Metabolism: the Heart at the Core of Interorgan Metabolic Cross Talk. Physiology (Bethesda) 2024, 39, 98–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hondares, E.; Rosell, M.; Gonzalez, F.J.; Giralt, M.; Iglesias, R.; Villarroya, F. Hepatic FGF21 expression is induced at birth via PPARalpha in response to milk intake and contributes to thermogenic activation of neonatal brown fat. Cell Metab 2010, 11, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hondares, E.; Iglesias, R.; Giralt, A.; Gonzalez, F.J.; Giralt, M.; Mampel, T.; Villarroya, F. Thermogenic activation induces FGF21 expression and release in brown adipose tissue. J Biol Chem 2011, 286, 12983–12990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, C.C.; Kong, L.R.; Chen, X.H.; Ma, Y.; Pan, X.X.; Zhang, Z.B.; Gao, P.J. A(2A) Receptor Activation Attenuates Hypertensive Cardiac Remodeling via Promoting Brown Adipose Tissue-Derived FGF21. Cell Metab 2018, 28, 476–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, F.M.; Maratos-Flier, E. Understanding the Physiology of FGF21. Annu Rev Physiol 2016, 78, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bookout, A.L.; de Groot, M.H.; Owen, B.M.; Lee, S.; Gautron, L.; Lawrence, H.L.; Ding, X.; Elmquist, J.K.; Takahashi, J.S.; Mangelsdorf, D.J.; et al. FGF21 regulates metabolism and circadian behavior by acting on the nervous system. Nat Med 2013, 19, 1147–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laeger, T.; Henagan, T.M.; Albarado, D.C.; Redman, L.M.; Bray, G.A.; Noland, R.C.; Münzberg, H.; Hutson, S.M.; Gettys, T.W.; Schwartz, M.W.; et al. FGF21 is an endocrine signal of protein restriction. J Clin Invest 2014, 124, 3913–3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.H.; Kim, S.Q.; Ross, R.C.; Corpodean, F.; Spann, R.A.; Albarado, D.A.; Fernandez-Kim, S.O.; Clarke, B.; Berthoud, H.R.; Münzberg, H.; et al. FGF21 acts in the brain to drive macronutrient-specific changes in behavioral motivation and brain reward signaling. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badman, M.K.; Pissios, P.; Kennedy, A.R.; Koukos, G.; Flier, J.S.; Maratos-Flier, E. Hepatic fibroblast growth factor 21 is regulated by PPARalpha and is a key mediator of hepatic lipid metabolism in ketotic states. Cell Metab 2007, 5, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Lee, M.S. FGF21 as a Stress Hormone: The Roles of FGF21 in Stress Adaptation and the Treatment of Metabolic Diseases. Diabetes Metab J 2014, 38, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, N.; Ohta, H. Pathophysiological roles of FGF signaling in the heart. Front Physiol 2013, 4, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, W.; Tucker, B.; Rye, K.A.; Ong, K.L. Fibroblast growth factor 21 in heart failure. Heart Fail Rev 2023, 28, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fon Tacer, K.; Bookout, A.L.; Ding, X.; Kurosu, H.; John, G.B.; Wang, L.; Goetz, R.; Mohammadi, M.; Kuro-o, M.; Mangelsdorf, D.J.; et al. Research resource: Comprehensive expression atlas of the fibroblast growth factor system in adult mouse. Mol Endocrinol 2010, 24, 2050–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planavila, A.; Redondo, I.; Hondares, E.; Vinciguerra, M.; Munts, C.; Iglesias, R.; Gabrielli, L.A.; Sitges, M.; Giralt, M.; van Bilsen, M.; et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 protects against cardiac hypertrophy in mice. Nat Commun 2013, 4, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Li, H.; Cao, G.; Li, P.; Zhou, H.; Sun, Y. The protective role of brown adipose tissue in cardiac cell damage after myocardial infarction and heart failure. Lipids Health Dis 2024, 23, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Su, J.; Shan, B.; Fu, X.; Zheng, G.; Wang, J.; Wu, L.; Wang, F.; Chai, X.; Sun, H.; et al. Brown adipose tissue-derived FGF21 mediates the cardioprotection of dexmedetomidine in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 18292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, M. Neuregulin 4 as a novel adipokine in energy metabolism. Front Physiol 2022, 13, 1106380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harari, D.; Tzahar, E.; Romano, J.; Shelly, M.; Pierce, J.H.; Andrews, G.C.; Yarden, Y. Neuregulin-4: a novel growth factor that acts through the ErbB-4 receptor tyrosine kinase. Oncogene 1999, 18, 2681–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vulf, M.; Bograya, M.; Komar, A.; Khaziakhmatova, O.; Malashchenko, V.; Yurova, K.; Sirotkina, A.; Minchenko, A.; Kirienkova, E.; Gazatova, N.; et al. NGR4 and ERBB4 as Promising Diagnostic and Therapeutic Targets for Metabolic Disorders. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2023, 15, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.; Xu, Y.; Wan, Q.; Feng, J.; Li, H.; Yang, J.; Zhong, H.; Zhang, Z. Plasma Neuregulin 4 Levels Are Associated with Metabolic Syndrome in Patients Newly Diagnosed with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Dis Markers 2018, 2018, 6974191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Li, M.; Zeng, T.; Hu, R.; Xu, Y.; Xu, M.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, S.; Lin, H.; et al. Association Between Insulin Resistance and Cardiovascular Disease Risk Varies According to Glucose Tolerance Status: A Nationwide Prospective Cohort Study. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 1863–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliszewska, K.; Kretowski, A. Brown Adipose Tissue and Its Role in Insulin and Glucose Homeostasis. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, G.-X.; Ma, S.L.; Jung, D.Y.; Ha, H.; Altamimi, T.; Zhao, X.-Y.; Guo, L.; Zhang, P.; Hu, C.-R.; et al. Nrg4 promotes fuel oxidation and a healthy adipokine profile to ameliorate diet-induced metabolic disorders. Molecular Metabolism 2017, 6, 863–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Gao, M.; Liu, D. Preventing High Fat Diet-induced Obesity and Improving Insulin Sensitivity through Neuregulin 4 Gene Transfer. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 26242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klop, B.; Elte, J.W.F.; Cabezas, M.C. Dyslipidemia in Obesity: Mechanisms and Potential Targets. Nutrients 2013, 5, 1218–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell-Wiley, T.M.; Poirier, P.; Burke, L.E.; Després, J.-P.; Gordon-Larsen, P.; Lavie, C.J.; Lear, S.A.; Ndumele, C.E.; Neeland, I.J.; Sanders, P.; et al. Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 143, e984–e1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Lin, M.; Xu, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, S.; Zhang, H. Association of circulating neuregulin 4 with metabolic syndrome in obese adults: a cross-sectional study. BMC Medicine 2016, 14, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, D.B.; Ikeda, K.; Kajimoto, K.; Hirata, K.-i.; Emoto, N. Activation of neuregulin-4 in adipocytes improves metabolic health by enhancing adipose tissue angiogenesis. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2018, 504, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, H.; Guo, X.; Yan, J.; Tian, X.; Yang, W.; Cui, K.; Wang, L.; Guo, B. Neuregulin-4 alleviates isoproterenol (ISO)-induced cardial remodeling by inhibiting inflammation and apoptosis via AMPK/NF-κB pathway. International Immunopharmacology 2024, 143, 113301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Guo, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Ma, M.; Guo, B. Neuregulin-4 protects cardiomyocytes against high-glucose-induced ferroptosis via the AMPK/NRF2 signalling pathway. Biology Direct 2024, 19, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Li, Y.; Xu, X.; Cheng, Y.; Meng, B.; Xu, J.; Xiang, L.; Zhang, J.; He, K.; Tong, J.; et al. Brown adipose tissue-derived Nrg4 alleviates endothelial inflammation and atherosclerosis in male mice. Nature Metabolism 2022, 4, 1573–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziqubu, K.; Dludla, P.V.; Mthembu, S.X.H.; Nkambule, B.; Mazibuko-Mbeje, S.E. Low circulating levels of neuregulin 4 as a potential biomarker associated with the severity and prognosis of obesity-related metabolic diseases: a systematic review. Adipocyte 2024, 13, 2390833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Lin, M.; Xu, Y.; Shao, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Yang, S. Circulating neuregulin 4 levels are inversely associated with subclinical cardiovascular disease in obese adults. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 36710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, F.; Hosseinzadeh-Attar, M.J.; Alipoor, E.; Honarkar-Shafie, E.; Yaseri, M.; Vasheghani-Farahani, A. Implications of the Serum Concentrations of Neuregulin-4 (Nrg4) in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease: A Case-Control Study. J Tehran Heart Cent 2023, 18, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Zhang, C.; Bu, S.; Guo, W.; Li, T.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, C.; Feng, C.; Zong, G.; et al. The Causal Effect of Serum Lipid Levels Mediated by Neuregulin 4 on the Risk of Four Atherosclerosis Subtypes: Evidence from Mendelian Randomization Analysis. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2024, 20, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McElroy, S.J.; Castle, S.L.; Bernard, J.K.; Almohazey, D.; Hunter, C.J.; Bell, B.A.; Al Alam, D.; Wang, L.; Ford, H.R.; Frey, M.R. The ErbB4 ligand neuregulin-4 protects against experimental necrotizing enterocolitis. Am J Pathol 2014, 184, 2768–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, H.; Gerhold, K.; Mayers, J.R.; Wiest, M.M.; Watkins, S.M.; Hotamisligil, G.S. Identification of a lipokine, a lipid hormone linking adipose tissue to systemic metabolism. Cell 2008, 134, 933–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynes, M.D.; Leiria, L.O.; Lundh, M.; Bartelt, A.; Shamsi, F.; Huang, T.L.; Takahashi, H.; Hirshman, M.F.; Schlein, C.; Lee, A.; et al. The cold-induced lipokine 12,13-diHOME promotes fatty acid transport into brown adipose tissue. Nat Med 2017, 23, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinckard, K.M.; Shettigar, V.K.; Wright, K.R.; Abay, E.; Baer, L.A.; Vidal, P.; Dewal, R.S.; Das, D.; Duarte-Sanmiguel, S.; Hernandez-Saavedra, D.; et al. A Novel Endocrine Role for the BAT-Released Lipokine 12,13-diHOME to Mediate Cardiac Function. Circulation 2021, 143, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanford, K.I.; Lynes, M.D.; Takahashi, H.; Baer, L.A.; Arts, P.J.; May, F.J.; Lehnig, A.C.; Middelbeek, R.J.W.; Richard, J.J.; So, K.; et al. 12,13-diHOME: An Exercise-Induced Lipokine that Increases Skeletal Muscle Fatty Acid Uptake. Cell Metabolism 2018, 27, 1111–1120.e1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Diaz-Canestro, C.; Wang, Y.; Tse, M.A.; Xu, A. Exerkines and cardiometabolic benefits of exercise: from bench to clinic. EMBO Mol Med 2024, 16, 432–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, J.M.; Gerszten, R.E. Exercise, exerkines, and cardiometabolic health: from individual players to a team sport. J Clin Invest 2023, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, B.A.; Smith, B.J.; Volpe, S.L.; Shen, C.L. Exerkines, Nutrition, and Systemic Metabolism. Nutrients 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, D.R.; Beigi, F.; Treuer, A.V.; Hare, J.M. Deficient ryanodine receptor S-nitrosylation increases sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium leak and arrhythmogenesis in cardiomyocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007, 104, 20612–20617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Viatchenko-Karpinski, S.; Sun, J.; Györke, I.; Benkusky, N.A.; Kohr, M.J.; Valdivia, H.H.; Murphy, E.; Györke, S.; Ziolo, M.T. Regulation of myocyte contraction via neuronal nitric oxide synthase: role of ryanodine receptor S-nitrosylation. J Physiol 2010, 588, 2905–2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannehr, M.; Löhr, L.; Gelep, J.; Haverkamp, W.; Schunck, W.H.; Gollasch, M.; Wutzler, A. Linoleic Acid Metabolite DiHOME Decreases Post-ischemic Cardiac Recovery in Murine Hearts. Cardiovasc Toxicol 2019, 19, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, K.R.; Zordoky, B.N.; Edin, M.L.; Alsaleh, N.; El-Kadi, A.O.; Zeldin, D.C.; Seubert, J.M. Differential effects of soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibition and CYP2J2 overexpression on postischemic cardiac function in aged mice. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 2013, 104-105, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samokhvalov, V.; Jamieson, K.L.; Darwesh, A.M.; Keshavarz-Bahaghighat, H.; Lee, T.Y.T.; Edin, M.; Lih, F.; Zeldin, D.C.; Seubert, J.M. Deficiency of Soluble Epoxide Hydrolase Protects Cardiac Function Impaired by LPS-Induced Acute Inflammation. Front Pharmacol 2018, 9, 1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, N.; Wang, Y.; Bao, B.; Wang, M.; Li, J.; Dang, W.; Hua, B.; Song, L.; Li, H.; Li, W. 12,13-diHOME and noradrenaline are associated with the occurrence of acute myocardial infarction in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetol Metab Syndr 2023, 15, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Li, Q.; Lynes, M.D.; Yokomizo, H.; Maddaloni, E.; Shinjo, T.; St-Louis, R.; Li, Q.; Katagiri, S.; Fu, J.; et al. Endothelial Cells Induced Progenitors Into Brown Fat to Reduce Atherosclerosis. Circ Res 2022, 131, 168–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guay, C.; Regazzi, R. Exosomes as new players in metabolic organ cross-talk. Diabetes Obes Metab 2017, 19 Suppl 1, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R.; LeBleu, V.S. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science 2020, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.R.; Ding, L.L.; Xu, L.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Z.B.; Chen, X.H.; Cheng, Y.W.; Ruan, C.C.; Gao, P.J. Brown Adipocyte ADRB3 Mediates Cardioprotection via Suppressing Exosomal iNOS. Circ Res 2022, 131, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Chen, X.; Hu, G.; Li, C.; Guo, L.; Zhang, L.; Sun, F.; Xia, Y.; Yan, W.; Cui, Z.; et al. Small Extracellular Vesicles From Brown Adipose Tissue Mediate Exercise Cardioprotection. Circ Res 2022, 130, 1490–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michel, L.Y.M. Extracellular Vesicles in Adipose Tissue Communication with the Healthy and Pathological Heart. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 7745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.; Sun, Y.; Shan, X.; Yang, F.; Chu, G.; Chen, Q.; Han, L.; Guo, Z.; Wang, G. Therapeutic overexpression of miR-92a-2-5p ameliorated cardiomyocyte oxidative stress injury in the development of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Cell Mol Biol Lett 2022, 27, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinkel, R.; Penzkofer, D.; Zuhlke, S.; Fischer, A.; Husada, W.; Xu, Q.F.; Baloch, E.; van Rooij, E.; Zeiher, A.M.; Kupatt, C.; et al. Inhibition of microRNA-92a protects against ischemia/reperfusion injury in a large-animal model. Circulation 2013, 128, 1066–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wu, H.Y.; Wang, W.Y.; Zhao, Z.L.; Liu, X.Y.; Wang, L.Y. Regulation of miR-92a on vascular endothelial aging via mediating Nrf2-KEAP1-ARE signal pathway. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2017, 21, 2734–2742. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Buyel, J.J.; Hanssen, M.J.; Siegel, F.; Pan, R.; Naumann, J.; Schell, M.; van der Lans, A.; Schlein, C.; Froehlich, H.; et al. Exosomal microRNA miR-92a concentration in serum reflects human brown fat activity. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 11420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.Y.; Zheng, Y.S.; Li, Z.G.; Cui, Y.M.; Jiang, J.C. MiR-92a contributes to the cardiovascular disease development in diabetes mellitus through NF-κB and downstream inflammatory pathways. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2019, 23, 3070–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, B.; Nedergaard, J. Yes, even human brown fat is on fire! J Clin Invest 2012, 122, 486–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, F.F.; Souza-Mello, V.; Aguila, M.B.; Mandarim-de-Lacerda, C.A. Brown adipose tissue as an endocrine organ: updates on the emerging role of batokines. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig 2023, 44, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedergaard, J.; Bengtsson, T.; Cannon, B. Unexpected evidence for active brown adipose tissue in adult humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2007, 293, E444–E452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedergaard, J.; Bengtsson, T.; Cannon, B. Three years with adult human brown adipose tissue. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2010, 1212, E20–E36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedergaard, J.; Bengtsson, T.; Cannon, B. New powers of brown fat: fighting the metabolic syndrome. Cell Metab 2011, 13, 238–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinckard, K.M.; Shettigar, V.K.; Wright, K.R.; Abay, E.; Baer, L.A.; Vidal, P.; Dewal, R.S.; Das, D.; Duarte-Sanmiguel, S.; Hernández-Saavedra, D.; et al. A Novel Endocrine Role for the BAT-Released Lipokine 12,13-diHOME to Mediate Cardiac Function. Circulation 2021, 143, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinckard, K.M.; Stanford, K.I. The Heartwarming Effect of Brown Adipose Tissue. Mol Pharmacol 2022, 102, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, E.J.; Virani, S.S.; Callaway, C.W.; Chamberlain, A.M.; Chang, A.R.; Cheng, S.; Chiuve, S.E.; Cushman, M.; Delling, F.N.; Deo, R.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2018 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018, 137, e67–e492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Li, Y.; Xu, X.; Cheng, Y.; Meng, B.; Xu, J.; Xiang, L.; Zhang, J.; He, K.; Tong, J.; et al. Brown adipose tissue-derived Nrg4 alleviates endothelial inflammation and atherosclerosis in male mice. Nat Metab 2022, 4, 1573–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Guo, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Ma, M.; Guo, B. Neuregulin-4 protects cardiomyocytes against high-glucose-induced ferroptosis via the AMPK/NRF2 signalling pathway. Biol Direct 2024, 19, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouellet, V.; Routhier-Labadie, A.; Bellemare, W.; Lakhal-Chaieb, L.; Turcotte, E.; Carpentier, A.C.; Richard, D. Outdoor temperature, age, sex, body mass index, and diabetic status determine the prevalence, mass, and glucose-uptake activity of 18F-FDG-detected BAT in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011, 96, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).