Submitted:

09 January 2025

Posted:

10 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Tonic and Phasic Neurotransmitters Detection Using Flexible MEAs

3. Results Conductive Polymers and Composite Coatings for Electrophysiological Recording and Neurotransmitter Detection

4. Enzymatic and Aptamer-Based Detection

5. Integration of Carbon Material in Flexible MEAs

6. Acquiring Electrochemical and Electrophysiological Measurements from a Single Device

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MEAs |

| Microelectrode arrays |

| DA |

| Dopamine |

| 5-HT |

| Serotonin |

| AD |

| Adenosine |

| ACh |

| Acetylcholine |

| MT |

| Melatonin |

| GLU |

| Glutamate |

| GABA |

| γ-aminobutyric acid |

| H2O2 |

| Hydrogen Peroxide |

| XNA |

| Xeno Nucleic Acid |

| FSCV |

| Fast Scan Cyclic Voltammetry |

| SWV |

| Square Wave Voltammetry |

| CFEs |

| Carbon Fiber Microelectrodes |

| GN |

| Guanosine |

| M-ENK |

| Methionine-enkephalin |

| CPA |

| Constant potential amperometry |

| m-PD |

| m-phenylenediamine |

| AA |

| ascorbic acid |

| DOPAC |

| 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid |

| CNT |

| carbon nanotubes |

| GC |

| Glassy carbon |

| FSCAV |

| fast-scan controlled-adsorption voltammetry |

| GCF |

| GC fiber-like |

| PPy |

| Polypyrrole |

| GO |

| graphene oxide |

| SWCNTs |

| single-wall carbon nanotube |

| NSR |

| Signal-to-noise-ratio |

| WT |

| wild type |

| MU |

| Δ19 Clock mutant |

| rGO |

| Reduced graphene oxide |

| PtNPs |

| platinum nanoparticles |

| nanoPt |

| Nano Platinum |

| TBI |

| traumatic brain injury |

| FETs |

| field-effect transistors |

| MB |

| methylene blue |

| PSB |

| poly(sulfobetaine methacrylate) |

| BDD |

| polycrystalline diamond |

| MW-PACVD |

| microwave plasma-assisted chemical vapor deposition |

| RIE |

| reactive ion etcher |

| LPCVD |

| low-stress low-pressure chemical vapor deposition |

| LIG |

| Laser-induced graphene |

| NAc |

| Nucleus Accumbens |

| BLA |

| Basolateral Amygdala |

| LFPs |

| Local Field Potentials |

| CNS |

| Central Nervous System |

| FSA |

| Fast Sampling Amperometry |

References

- A.E. Pereda, Electrical synapses and their functional interactions with chemical synapses, Nature Reviews Neuroscience 15(4) (2014) 250-263. [CrossRef]

- P. Alcami, A.E. Pereda, Beyond plasticity: the dynamic impact of electrical synapses on neural circuits, Nature Reviews Neuroscience 20(5) (2019) 253-271. [CrossRef]

- A.C. Miller, L.H. Voelker, A.N. Shah, C.B. Moens, Neurobeachin is required postsynaptically for electrical and chemical synapse formation, Current Biology 25(1) (2015) 16-28. [CrossRef]

- T.N. Lerner, L. Ye, K. Deisseroth, Communication in neural circuits: tools, opportunities, and challenges, Cell 164(6) (2016) 1136-1150. [CrossRef]

- L.A. Jorgenson, W.T. Newsome, D.J. Anderson, C.I. Bargmann, E.N. Brown, K. Deisseroth, J.P. Donoghue, K.L. Hudson, G.S. Ling, P.R. MacLeish, The BRAIN Initiative: developing technology to catalyse neuroscience discovery, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 370(1668) (2015) 20140164. [CrossRef]

- C.T. Moritz, Now is the critical time for engineered neuroplasticity, Neurotherapeutics 15(3) (2018) 628-634. [CrossRef]

- C.W. Atcherley, N.D. Laude, K.L. Parent, M.L. Heien, Fast-scan controlled-adsorption voltammetry for the quantification of absolute concentrations and adsorption dynamics, Langmuir 29(48) (2013) 14885-14892. [CrossRef]

- E.C. Rutherford, F. Pomerleau, P. Huettl, I. Strömberg, G.A. Gerhardt, Chronic second-by-second measures of l-glutamate in the central nervous system of freely moving rats, Journal of neurochemistry 102(3) (2007) 712-722. [CrossRef]

- D.J. Edell, V.V. Toi, V.M. McNeil, L. Clark, Factors influencing the biocompatibility of insertable silicon microshafts in cerebral cortex, IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 39(6) (1992) 635-643. [CrossRef]

- D. Szarowski, M. Andersen, S. Retterer, A. Spence, M. Isaacson, H.G. Craighead, J. Turner, W. Shain, Brain responses to micro-machined silicon devices, Brain research 983(1-2) (2003) 23-35. [CrossRef]

- T.D. Kozai, A.S. Jaquins-Gerstl, A.L. Vazquez, A.C. Michael, X.T. Cui, Brain tissue responses to neural implants impact signal sensitivity and intervention strategies, ACS chemical neuroscience 6(1) (2015) 48-67. [CrossRef]

- R.C. Engstrom, R.M. Wightman, E.W. Kristensen, Diffusional distortion in the monitoring of dynamic events, Analytical Chemistry 60(7) (1988) 652-656. [CrossRef]

- K. Kawagoe, P. Garris, D. Wiedemann, R. Wightman, Regulation of transient dopamine concentration gradients in the microenvironment surrounding nerve terminals in the rat striatum, Neuroscience 51(1) (1992) 55-64. [CrossRef]

- H.N. Schwerdt, M. Kim, E. Karasan, S. Amemori, D. Homma, H. Shimazu, T. Yoshida, R. Langer, A.M. Graybiel, M.J. Cima, Subcellular electrode arrays for multisite recording of dopamine in vivo, 2017 IEEE 30th International Conference on Micro Electromechanical Systems (MEMS), IEEE, 2017, pp. 549-552. [CrossRef]

- E. Castagnola, X.S. Zheng, X.T. Cui, Flexible and soft materials and devices for neural interface, Handbook of Neuroengineering, Springer2023, pp. 79-139. [CrossRef]

- L. Luan, J.T. Robinson, B. Aazhang, T. Chi, K. Yang, X. Li, H. Rathore, A. Singer, S. Yellapantula, Y. Fan, Recent advances in electrical neural interface engineering: minimal invasiveness, longevity, and scalability, Neuron 108(2) (2020) 302-321. [CrossRef]

- L. Luan, X. Wei, Z. Zhao, J.J. Siegel, O. Potnis, C.A. Tuppen, S. Lin, S. Kazmi, R.A. Fowler, S. Holloway, Ultraflexible nanoelectronic probes form reliable, glial scar–free neural integration, Science advances 3(2) (2017) e1601966. [CrossRef]

- X. Wei, L. Luan, Z. Zhao, X. Li, H. Zhu, O. Potnis, C. Xie, Nanofabricated ultraflexible electrode arrays for high-density intracortical recording, Advanced Science 5(6) (2018) 1700625. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhao, H. Zhu, X. Li, L. Sun, F. He, J.E. Chung, D.F. Liu, L. Frank, L. Luan, C. Xie, Ultraflexible electrode arrays for months-long high-density electrophysiological mapping of thousands of neurons in rodents, Nature biomedical engineering 7(4) (2023) 520-532. [CrossRef]

- X. Dai, G. Hong, T. Gao, C.M. Lieber, Mesh nanoelectronics: seamless integration of electronics with tissues, Accounts of chemical research 51(2) (2018) 309-318. [CrossRef]

- J.M. Lee, G. Hong, D. Lin, T.G. Schuhmann Jr, A.T. Sullivan, R.D. Viveros, H.-G. Park, C.M. Lieber, Nanoenabled direct contact interfacing of syringe-injectable mesh electronics, Nano letters 19(8) (2019) 5818-5826. [CrossRef]

- X.S. Zheng, Q. Yang, A. Vazquez, X.T. Cui, Imaging the stability of chronic electrical microstimulation using electrodes coated with PEDOT/CNT and iridium oxide, IScience 25(7) (2022). [CrossRef]

- Y.-M. Chen, T.-W. Chung, P.-W. Wu, P.-C. Chen, A cost-effective fabrication of iridium oxide films as biocompatible electrostimulation electrodes for neural interface applications, Journal of Alloys and Compounds 692 (2017) 339-345. [CrossRef]

- R.D. Meyer, S.F. Cogan, T.H. Nguyen, R.D. Rauh, Electrodeposited iridium oxide for neural stimulation and recording electrodes, IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 9(1) (2001) 2-11. [CrossRef]

- S. Negi, R. Bhandari, L. Rieth, F. Solzbacher, In vitro comparison of sputtered iridium oxide and platinum-coated neural implantable microelectrode arrays, Biomedical materials 5(1) (2010) 015007. [CrossRef]

- S.F. Cogan, Neural stimulation and recording electrodes, Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 10(1) (2008) 275-309. [CrossRef]

- Q. Yang, B. Wu, E. Castagnola, M.Y. Pwint, N.P. Williams, A.L. Vazquez, X.T. Cui, Integrated Microprism and Microelectrode Array for Simultaneous Electrophysiology and Two-Photon Imaging across All Cortical Layers, Advanced Healthcare Materials (2024) 2302362. [CrossRef]

- C. Boehler, D.M. Vieira, U. Egert, M. Asplund, NanoPt—a nanostructured electrode coating for neural recording and microstimulation, ACS applied materials & interfaces 12(13) (2020) 14855-14865. [CrossRef]

- C. Boehler, F. Oberueber, T. Stieglitz, M. Asplund, Nanostructured platinum as an electrochemically and mechanically stable electrode coating, 2017 39th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), IEEE, 2017, pp. 1058-1061. [CrossRef]

- B. Wu, E. Castagnola, C.A. McClung, X.T. Cui, PEDOT/CNT Flexible MEAs Reveal New Insights into the Clock Gene’s Role in Dopamine Dynamics, Advanced Science (2024) 2308212. [CrossRef]

- V. Castagnola, C. Bayon, E. Descamps, C. Bergaud, Morphology and. [CrossRef]

- X. Cui, V.A. Lee, Y. Raphael, J.A. Wiler, J.F. Hetke, D.J. Anderson, D.C. Martin, Surface modification of neural recording electrodes with conducting polymer/biomolecule blends, Journal of Biomedical Materials Research: An Official Journal of The Society for Biomaterials, The Japanese Society for Biomaterials, and The Australian Society for Biomaterials and the Korean Society for Biomaterials 56(2) (2001) 261-272. [CrossRef]

- X. Cui, D.C. Martin, Electrochemical deposition and characterization of poly (3, 4-ethylenedioxythiophene) on neural microelectrode arrays, Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 89(1-2) (2003) 92-102. [CrossRef]

- E. Castagnola, L. Maiolo, E. Maggiolini, A. Minotti, M. Marrani, F. Maita, A. Pecora, G.N. Angotzi, A. Ansaldo, L. Fadiga, Ultra-flexible and brain-conformable micro-electrocorticography device with low impedance PEDOT-carbon nanotube coated microelectrodes, 2013 6th International IEEE/EMBS Conference on Neural Engineering (NER), IEEE, 2013, pp. 927-930. [CrossRef]

- E. Castagnola, A. Ansaldo, E. Maggiolini, T. Ius, M. Skrap, D. Ricci, L. Fadiga, Smaller, softer, lower-impedance electrodes for human neuroprosthesis: a pragmatic approach, Frontiers in neuroengineering 7 (2014) 8. [CrossRef]

- D. Khodagholy, J.N. Gelinas, T. Thesen, W. Doyle, O. Devinsky, G.G. Malliaras, G. Buzsáki, NeuroGrid: recording action potentials from the surface of the brain, Nature neuroscience 18(2) (2015) 310-315. [CrossRef]

- M. Asplund, T. Nyberg, O. Inganäs, Electroactive polymers for neural interfaces, Polymer Chemistry 1(9) (2010) 1374-1391. [CrossRef]

- E. Castagnola, E.M. Robbins, B. Wu, M.Y. Pwint, R. Garg, T. Cohen-Karni, X.T. Cui, Flexible glassy carbon multielectrode array for in vivo multisite detection of tonic and phasic dopamine concentrations, Biosensors 12(7) (2022) 540. [CrossRef]

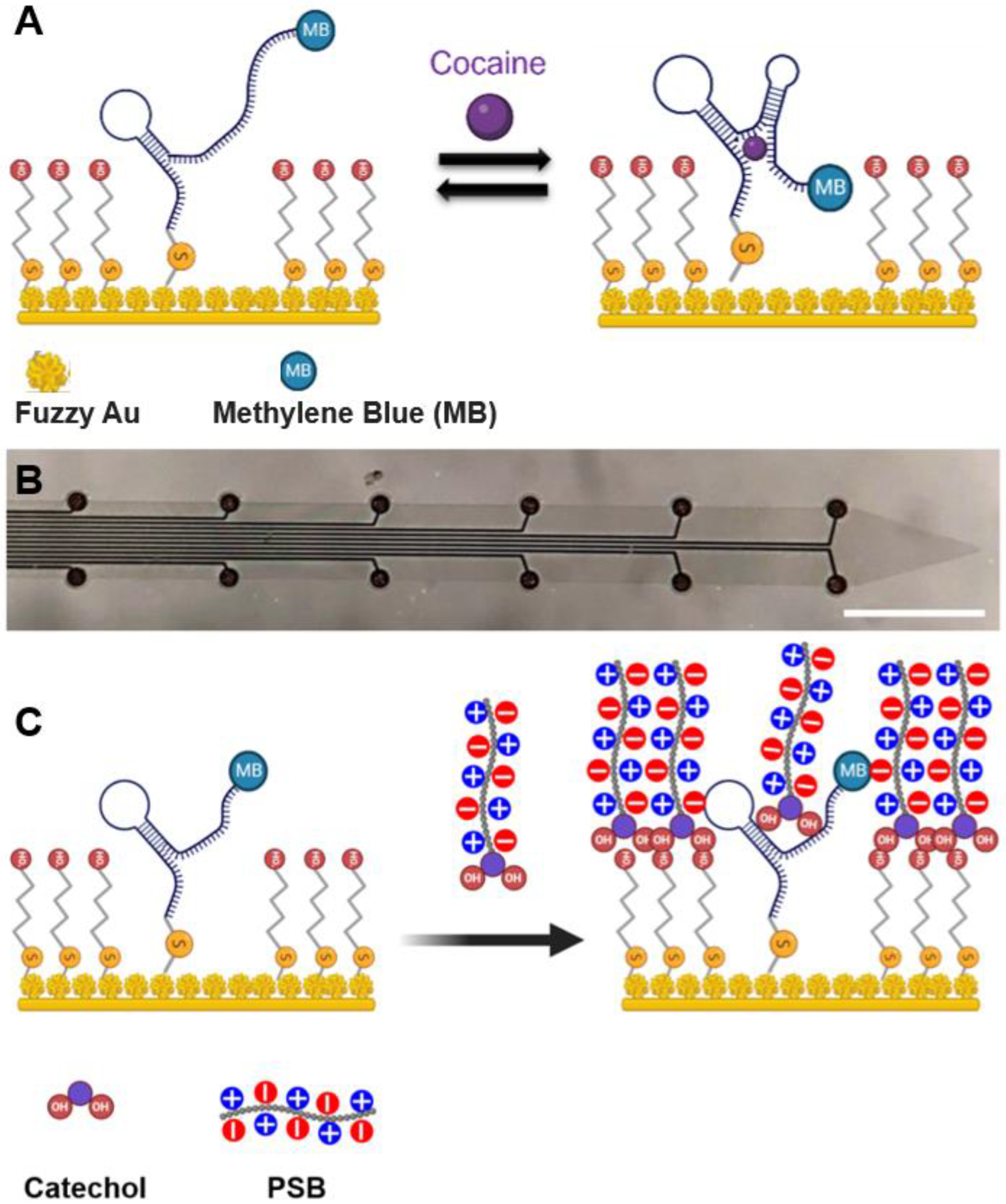

- B. Wu, E. Castagnola, X.T. Cui, Zwitterionic polymer coated and aptamer functionalized flexible micro-electrode arrays for in vivo cocaine sensing and electrophysiology, Micromachines 14(2) (2023) 323. [CrossRef]

- M.L. Huffman, B.J. Venton, Carbon-fiber microelectrodes for in vivo applications, Analyst 134(1) (2009) 18-24. [CrossRef]

- P. Puthongkham, B.J. Venton, Recent advances in fast-scan cyclic voltammetry, Analyst 145(4) (2020) 1087-1102. [CrossRef]

- B.K. Swamy, B.J. Venton, Subsecond detection of physiological adenosine concentrations using fast-scan cyclic voltammetry, Analytical chemistry 79(2) (2007) 744-750. [CrossRef]

- B.J. Venton, Q. Cao, Fundamentals of fast-scan cyclic voltammetry for dopamine detection, Analyst 145(4) (2020) 1158-1168. [CrossRef]

- E. Castagnola, E.M. Robbins, K.M. Woeppel, M. McGuier, A. Golabchi, I.M. Taylor, A.C. Michael, X.T. Cui, Real-time fast scan cyclic voltammetry detection and quantification of exogenously administered melatonin in mice brain, Frontiers in bioengineering and biotechnology 8 (2020) 602216. [CrossRef]

- E. Castagnola, K. Woeppel, A. Golabchi, M. McGuier, N. Chodapaneedi, J. Metro, I.M. Taylor, X.T. Cui, Electrochemical detection of exogenously administered melatonin in the brain, Analyst 145(7) (2020) 2612-2620. [CrossRef]

- A.L. Hensley, A.R. Colley, A.E. Ross, Real-time detection of melatonin using fast-scan cyclic voltammetry, Analytical chemistry 90(14) (2018) 8642-8650. [CrossRef]

- C. Tan, E.M. Robbins, B. Wu, X.T. Cui, Recent advances in in vivo neurochemical monitoring, Micromachines 12(2) (2021) 208. [CrossRef]

- S.J. Updike, M.C. Shults, R.K. Rhodes, B.J. Gilligan, J.O. Luebow, D. Von Heimburg, Enzymatic glucose sensors: improved long-term performance: in vitro: and: in vivo, Asaio Journal 40(2) (1994) 157-163.

- E.M. Robbins, B. Wong, M.Y. Pwint, S. Salavatian, A. Mahajan, X.T. Cui, Improving Sensitivity and Longevity of In Vivo Glutamate Sensors with Electrodeposited NanoPt, ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 16(31) (2024) 40570-40580. [CrossRef]

- S. Salavatian, E.M. Robbins, Y. Kuwabara, E. Castagnola, X.T. Cui, A. Mahajan, Real-time in vivo thoracic spinal glutamate sensing during myocardial ischemia, American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 325(6) (2023) H1304-H1317. [CrossRef]

- S. Billa, Y. Yanamadala, I. Hossain, S. Siddiqui, N. Moldovan, T.A. Murray, P.U. Arumugam, Brain-implantable multifunctional probe for simultaneous detection of glutamate and GABA neurotransmitters: optimization and in vivo studies, Micromachines 13(7) (2022) 1008. [CrossRef]

- Z. Hu, Y. Li, G. Figueroa-Miranda, S. Musall, H. Li, M.A. Martínez-Roque, Q. Hu, L. Feng, D. Mayer, A. Offenhäusser, Aptamer based biosensor platforms for neurotransmitters analysis, TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 162 (2023) 117021. [CrossRef]

- G. Wu, N. Zhang, A. Matarasso, I. Heck, H. Li, W. Lu, J.G. Phaup, M.J. Schneider, Y. Wu, Z. Weng, Implantable aptamer-graphene microtransistors for real-time monitoring of neurochemical release in vivo, Nano letters 22(9) (2022) 3668-3677. [CrossRef]

- A.M. Downs, K.W. Plaxco, Real-time, in vivo molecular monitoring using electrochemical aptamer based sensors: opportunities and challenges, ACS sensors 7(10) (2022) 2823-2832.

- A.A. Grace, Dysregulation of the dopamine system in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia and depression, Nature Reviews Neuroscience 17(8) (2016) 524-532. [CrossRef]

- A.A. Grace, The tonic/phasic model of dopamine system regulation and its implications for understanding alcohol and psychostimulant craving, Addiction 95(8s2) (2000) 119-128. [CrossRef]

- L. Zhang, W.M. Doyon, J.J. Clark, P.E. Phillips, J.A. Dani, Controls of tonic and phasic dopamine transmission in the dorsal and ventral striatum, Molecular pharmacology 76(2) (2009) 396-404. [CrossRef]

- R.A. Saylor, M. Hersey, A. West, A.M. Buchanan, S.N. Berger, H.F. Nijhout, M.C. Reed, J. Best, P. Hashemi, In vivo hippocampal serotonin dynamics in male and female mice: Determining effects of acute escitalopram using fast scan cyclic voltammetry, Frontiers in neuroscience 13 (2019) 362. [CrossRef]

- Mitch Taylor, A. Jaquins-Gerstl, S.R. Sesack, A.C. Michael, Domain-dependent effects of DAT inhibition in the rat dorsal striatum, Journal of neurochemistry 122(2) (2012) 283-294. [CrossRef]

- I.M. Taylor, K.M. Nesbitt, S.H. Walters, E.L. Varner, Z. Shu, K.M. Bartlow, A.S. Jaquins-Gerstl, A.C. Michael, Kinetic diversity of dopamine transmission in the dorsal striatum, Journal of neurochemistry 133(4) (2015) 522-531. [CrossRef]

- H. Rafi, A.G. Zestos, Recent advances in FSCV detection of neurochemicals via waveform and carbon microelectrode modification, Journal of The Electrochemical Society 168(5) (2021) 057520. [CrossRef]

- J.G. Roberts, L.A. Sombers, Fast scan cyclic voltammetry: Chemical sensing in the brain and beyond, Analytical chemistry 90(1) (2018) 490. [CrossRef]

- C.J. Meunier, L.A. Sombers, Fast-scan voltammetry for in vivo measurements of neurochemical dynamics, The brain reward system (2021) 93-123. [CrossRef]

- R.B. Keithley, P. Takmakov, E.S. Bucher, A.M. Belle, C.A. Owesson-White, J. Park, R.M. Wightman, Higher sensitivity dopamine measurements with faster-scan cyclic voltammetry, Analytical chemistry 83(9) (2011) 3563-3571. [CrossRef]

- J.G. Roberts, J.V. Toups, E. Eyualem, G.S. McCarty, L.A. Sombers, In situ electrode calibration strategy for voltammetric measurements in vivo, Analytical chemistry 85(23) (2013) 11568-11575. [CrossRef]

- M. Ganesana, S.T. Lee, Y. Wang, B.J. Venton, Analytical techniques in neuroscience: recent advances in imaging, separation, and electrochemical methods, Analytical chemistry 89(1) (2017) 314-341. [CrossRef]

- S. Hafizi, Z.L. Kruk, J.A. Stamford, Fast cyclic voltammetry: improved sensitivity to dopamine with extended oxidation scan limits, Journal of neuroscience methods 33(1) (1990) 41-49. [CrossRef]

- M.L. Heien, P.E. Phillips, G.D. Stuber, A.T. Seipel, R.M. Wightman, Overoxidation of carbon-fiber microelectrodes enhances dopamine adsorption and increases sensitivity, Analyst 128(12) (2003) 1413-1419. [CrossRef]

- B.P. Jackson, S.M. Dietz, R.M. Wightman, Fast-scan cyclic voltammetry of 5-hydroxytryptamine, Analytical chemistry 67(6) (1995) 1115-1120. [CrossRef]

- K.E. Dunham, B.J. Venton, Improving serotonin fast-scan cyclic voltammetry detection: new waveforms to reduce electrode fouling, Analyst 145(22) (2020) 7437-7446. [CrossRef]

- S.E. Cooper, B.J. Venton, Fast-scan cyclic voltammetry for the detection of tyramine and octopamine, Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry 394 (2009) 329-336. [CrossRef]

- J.G. Roberts, L.Z. Lugo-Morales, P.L. Loziuk, L.A. Sombers, Real-time chemical measurements of dopamine release in the brain, Dopamine: methods and protocols (2013) 275-294. [CrossRef]

- P. Cavelier, M. Hamann, D. Rossi, P. Mobbs, D. Attwell, Tonic excitation and inhibition of neurons: ambient transmitter sources and computational consequences, Progress in biophysics and molecular biology 87(1) (2005) 3-16. [CrossRef]

- M. Sarter, C. Lustig, Forebrain cholinergic signaling: wired and phasic, not tonic, and causing behavior, Journal of Neuroscience 40(4) (2020) 712-719. [CrossRef]

- L.M.T.-G. Ruivo, K.L. Baker, M.W. Conway, P.J. Kinsley, G. Gilmour, K.G. Phillips, J.T. Isaac, J.P. Lowry, J.R. Mellor, Coordinated acetylcholine release in prefrontal cortex and hippocampus is associated with arousal and reward on distinct timescales, Cell reports 18(4) (2017) 905-917. [CrossRef]

- A.A. Grace, Phasic versus tonic dopamine release and the modulation of dopamine system responsivity: a hypothesis for the etiology of schizophrenia, Neuroscience 41(1) (1991) 1-24. [CrossRef]

- A.A. Grace, The tonic/phasic model of dopamine system regulation: its relevance for understanding how stimulant abuse can alter basal ganglia function, Drug and alcohol dependence 37(2) (1995) 111-129. [CrossRef]

- E.A. Budygin, C.E. Bass, V.P. Grinevich, A.L. Deal, K.D. Bonin, J.L. Weiner, Opposite consequences of tonic and phasic increases in accumbal dopamine on alcohol-seeking behavior, IScience 23(3) (2020). [CrossRef]

- A. Ledo, C.F. Lourenco, J. Laranjinha, G.A. Gerhardt, R.M. Barbosa, Concurrent measurements of neurochemical and electrophysiological activity with microelectrode arrays: new perspectives for constant potential amperometry, Current Opinion in Electrochemistry 12 (2018) 129-140. [CrossRef]

- M.D. Johnson, R.K. Franklin, M.D. Gibson, R.B. Brown, D.R. Kipke, Implantable microelectrode arrays for simultaneous electrophysiological and neurochemical recordings, Journal of Neuroscience Methods 174(1) (2008) 62-70. [CrossRef]

- M. Lundblad, D.A. Price, J.J. Burmeister, J.E. Quintero, P. Huettl, F. Pomerleau, N.R. Zahniser, G.A. Gerhardt, Tonic and phasic amperometric monitoring of dopamine using microelectrode arrays in rat striatum, Applied Sciences 10(18) (2020) 6449. [CrossRef]

- J.E. Quintero, F. Pomerleau, P. Huettl, K.W. Johnson, J. Offord, G.A. Gerhardt, Methodology for rapid measures of glutamate release in rat brain slices using ceramic-based microelectrode arrays: basic characterization and drug pharmacology, Brain research 1401 (2011) 1-9. [CrossRef]

- E. Rand, A. Periyakaruppan, Z. Tanaka, D.A. Zhang, M.P. Marsh, R.J. Andrews, K.H. Lee, B. Chen, M. Meyyappan, J.E. Koehne, A carbon nanofiber-based biosensor for simultaneous detection of dopamine and serotonin in the presence of ascorbicacid, Biosensors and Bioelectronics 42 (2013) 434-438. [CrossRef]

- C. Tan, P.T. Doughty, K. Magee, T.A. Murray, S. Siddiqui, P.U. Arumugam, Effect of process parameters on electrochemical performance of a glutamate microbiosensor, Journal of the Electrochemical Society 167(2) (2020) 027528. [CrossRef]

- J.J. Burmeister, M. Palmer, G.A. Gerhardt, Ceramic-based multisite microelectrode array for rapid choline measures in brain tissue, Analytica chimica acta 481(1) (2003) 65-74. [CrossRef]

- J.J. Burmeister, F. Pomerleau, P. Huettl, C.R. Gash, C.E. Werner, J.P. Bruno, G.A. Gerhardt, Ceramic-based multisite microelectrode arrays for simultaneous measures of choline and acetylcholine in CNS, Biosensors and bioelectronics 23(9) (2008) 1382-1389. [CrossRef]

- C.E. Mattinson, J.J. Burmeister, J.E. Quintero, F. Pomerleau, P. Huettl, G.A. Gerhardt, Tonic and phasic release of glutamate and acetylcholine neurotransmission in sub-regions of the rat prefrontal cortex using enzyme-based microelectrode arrays, Journal of neuroscience methods 202(2) (2011) 199-208. [CrossRef]

- T.T.-C. Tseng, H.G. Monbouquette, Implantable microprobe with arrayed microsensors for combined amperometric monitoring of the neurotransmitters, glutamate and dopamine, Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry 682 (2012) 141-146. [CrossRef]

- C.W. Atcherley, Voltammetric Measurements Of Tonic And Phasic Neurotransmission, (2014).

- M.H. Burrell, C.W. Atcherley, M.L. Heien, J. Lipski, A novel electrochemical approach for prolonged measurement of absolute levels of extracellular dopamine in brain slices, ACS chemical neuroscience 6(11) (2015) 1802-1812. [CrossRef]

- A. Abdalla, C.W. Atcherley, P. Pathirathna, S. Samaranayake, B. Qiang, E. Peña, S.L. Morgan, M.L. Heien, P. Hashemi, In vivo ambient serotonin measurements at carbon-fiber microelectrodes, Analytical chemistry 89(18) (2017) 9703-9711. [CrossRef]

- Y. Oh, C. Park, D.H. Kim, H. Shin, Y.M. Kang, M. DeWaele, J. Lee, H.-K. Min, C.D. Blaha, K.E. Bennet, Monitoring in vivo changes in tonic extracellular dopamine level by charge-balancing multiple waveform fast-scan cyclic voltammetry, Analytical chemistry 88(22) (2016) 10962-10970. [CrossRef]

- A.E. Rusheen, T.A. Gee, D.P. Jang, C.D. Blaha, K.E. Bennet, K.H. Lee, M.L. Heien, Y. Oh, Evaluation of electrochemical methods for tonic dopamine detection in vivo, TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 132 (2020) 116049. [CrossRef]

- J.A. Johnson, N.T. Rodeberg, R.M. Wightman, Measurement of basal neurotransmitter levels using convolution-based nonfaradaic current removal, Analytical chemistry 90(12) (2018) 7181-7189. [CrossRef]

- C. Park, Y. Oh, H. Shin, J. Kim, Y. Kang, J. Sim, H.U. Cho, H.K. Lee, S.J. Jung, C.D. Blaha, Fast cyclic square-wave voltammetry to enhance neurotransmitter selectivity and sensitivity, Analytical chemistry 90(22) (2018) 13348-13355. [CrossRef]

- H. Shin, Y. Oh, C. Park, Y. Kang, H.U. Cho, C.D. Blaha, K.E. Bennet, M.L. Heien, I.Y. Kim, K.H. Lee, Sensitive and selective measurement of serotonin in vivo using fast cyclic square-wave voltammetry, Analytical chemistry 92(1) (2019) 774-781. [CrossRef]

- H. Shin, A. Goyal, J.H. Barnett, A.E. Rusheen, J. Yuen, R. Jha, S.M. Hwang, Y. Kang, C. Park, H.-U. Cho, Tonic serotonin measurements in vivo using N-shaped multiple cyclic square wave voltammetry, Analytical chemistry 93(51) (2021) 16987-16994. [CrossRef]

- Y. Oh, M.L. Heien, C. Park, Y.M. Kang, J. Kim, S.L. Boschen, H. Shin, H.U. Cho, C.D. Blaha, K.E. Bennet, Tracking tonic dopamine levels in vivo using multiple cyclic square wave voltammetry, Biosensors and Bioelectronics 121 (2018) 174-182. [CrossRef]

- D.-K. Kim, T.J. Tolliver, S.-J. Huang, B.J. Martin, A.M. Andrews, C. Wichems, A. Holmes, K.-P. Lesch, D.L. Murphy, Altered serotonin synthesis, turnover and dynamic regulation in multiple brain regions of mice lacking the serotonin transporter, Neuropharmacology 49(6) (2005) 798-810. [CrossRef]

- J. Wickens, M. Alexander, R. Miller, Two dynamic modes of striatal function under dopaminergic-cholinergic control: Simulation and analysis of a model, Synapse 8(1) (1991) 1-12. [CrossRef]

- A.G. Salinas, M.I. Davis, D.M. Lovinger, Y. Mateo, Dopamine dynamics and cocaine sensitivity differ between striosome and matrix compartments of the striatum, Neuropharmacology 108 (2016) 275-283. [CrossRef]

- S. Threlfell, S.J. Cragg, Dopamine signaling in dorsal versus ventral striatum: the dynamic role of cholinergic interneurons, Frontiers in systems neuroscience 5 (2011) 11. [CrossRef]

- A.L. Collins, B.T. Saunders, Heterogeneity in striatal dopamine circuits: Form and function in dynamic reward seeking, Journal of neuroscience research 98(6) (2020) 1046-1069. [CrossRef]

- E. Castagnola, Q. Cao, E. Robbins, B. Wu, M.Y. Pwint, U. Siwakoti, X.T. Cui, Glassy Carbon Fiber-Like Multielectrode Arrays for Neurochemical Sensing and Electrophysiology Recording, Advanced Materials Technologies (2024) 2400863. [CrossRef]

- E. Castagnola, E.M. Robbins, D.D. Krahe, B. Wu, M.Y. Pwint, Q. Cao, X.T. Cui, Stable in-vivo electrochemical sensing of tonic serotonin levels using PEDOT/CNT-coated glassy carbon flexible microelectrode arrays, Biosensors and Bioelectronics 230 (2023) 115242. [CrossRef]

- A.S. Pranti, A. Schander, A. Bödecker, W. Lang, PEDOT: PSS coating on gold microelectrodes with excellent stability and high charge injection capacity for chronic neural interfaces, Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 275 (2018) 382-393. [CrossRef]

- E. Castagnola, S. Carli, M. Vomero, A. Scarpellini, M. Prato, N. Goshi, L. Fadiga, S. Kassegne, D. Ricci, Multilayer poly (3, 4-ethylenedioxythiophene)-dexamethasone and poly (3, 4-ethylenedioxythiophene)-polystyrene sulfonate-carbon nanotubes coatings on glassy carbon microelectrode arrays for controlled drug release, Biointerphases 12(3) (2017). [CrossRef]

- E. Castagnola, L. Maiolo, E. Maggiolini, A. Minotti, M. Marrani, F. Maita, A. Pecora, G.N. Angotzi, A. Ansaldo, M. Boffini, PEDOT-CNT-coated low-impedance, ultra-flexible, and brain-conformable micro-ECoG arrays, IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 23(3) (2014) 342-350. [CrossRef]

- E. Castagnola, A. Ansaldo, E. Maggiolini, G.N. Angotzi, M. Skrap, D. Ricci, L. Fadiga, Biologically compatible neural interface to safely couple nanocoated electrodes to the surface of the brain, ACS nano 7(5) (2013) 3887-3895. [CrossRef]

- A. Ansaldo, E. Castagnola, E. Maggiolini, L. Fadiga, D. Ricci, Superior electrochemical performance of carbon nanotubes directly grown on sharp microelectrodes, ACS nano 5(3) (2011) 2206-2214. [CrossRef]

- G. Baranauskas, E. Maggiolini, E. Castagnola, A. Ansaldo, A. Mazzoni, G.N. Angotzi, A. Vato, D. Ricci, S. Panzeri, L. Fadiga, Carbon nanotube composite coating of neural microelectrodes preferentially improves the multiunit signal-to-noise ratio, Journal of neural engineering 8(6) (2011) 066013. [CrossRef]

- X. Cui, D.C. Martin, Fuzzy gold electrodes for lowering impedance and improving adhesion with electrodeposited conducting polymer films, Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 103(3) (2003) 384-394. [CrossRef]

- X. Cui, J. Wiler, M. Dzaman, R.A. Altschuler, D.C. Martin, In vivo studies of polypyrrole/peptide coated neural probes, Biomaterials 24(5) (2003) 777-787. [CrossRef]

- H. Shi, C. Liu, Q. Jiang, J. Xu, Effective approaches to improve the electrical conductivity of PEDOT: PSS: a review, Advanced Electronic Materials 1(4) (2015) 1500017. [CrossRef]

- K.M. Woeppel, X.S. Zheng, Z.M. Schulte, N.L. Rosi, X.T. Cui, Nanoparticle doped PEDOT for enhanced electrode coatings and drug delivery, Advanced healthcare materials 8(21) (2019) 1900622. [CrossRef]

- C. Boehler, C. Kleber, N. Martini, Y. Xie, I. Dryg, T. Stieglitz, U. Hofmann, M. Asplund, Actively controlled release of Dexamethasone from neural microelectrodes in a chronic in vivo study, Biomaterials 129 (2017) 176-187. [CrossRef]

- M. Vázquez, J. Bobacka, A. Ivaska, A. Lewenstam, Influence of oxygen and carbon dioxide on the electrochemical stability of poly (3, 4-ethylenedioxythiophene) used as ion-to-electron transducer in all-solid-state ion-selective electrodes, Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 82(1) (2002) 7-13. [CrossRef]

- V. Castagnola, E. Descamps, A. Lecestre, L. Dahan, J. Remaud, L.G. Nowak, C. Bergaud, Parylene-based flexible neural probes with PEDOT coated surface for brain stimulation and recording, Biosensors and Bioelectronics 67 (2015) 450-457. [CrossRef]

- X.T. Cui, D.D. Zhou, Poly (3, 4-ethylenedioxythiophene) for chronic neural stimulation, IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 15(4) (2007) 502-508. [CrossRef]

- E. Musk, An integrated brain-machine interface platform with thousands of channels, Journal of medical Internet research 21(10) (2019) e16194. [CrossRef]

- H. Vara, J.E. Collazos-Castro, Enhanced spinal cord microstimulation using conducting polymer-coated carbon microfibers, Acta biomaterialia 90 (2019) 71-86. [CrossRef]

- X.S. Zheng, C. Tan, E. Castagnola, X.T. Cui, Electrode materials for chronic electrical microstimulation, Advanced healthcare materials 10(12) (2021) 2100119. [CrossRef]

- R.A. Green, R.T. Hassarati, L. Bouchinet, C.S. Lee, G.L. Cheong, F.Y. Jin, C.W. Dodds, G.J. Suaning, L.A. Poole-Warren, N.H. Lovell, Substrate dependent stability of conducting polymer coatings on medical electrodes, Biomaterials 33(25) (2012) 5875-5886. [CrossRef]

- L. Ouyang, B. Wei, C.-c. Kuo, S. Pathak, B. Farrell, D.C. Martin, Enhanced PEDOT adhesion on solid substrates with electrografted P (EDOT-NH2), Science advances 3(3) (2017) e1600448. [CrossRef]

- S. Carli, L. Lambertini, E. Zucchini, F. Ciarpella, A. Scarpellini, M. Prato, E. Castagnola, L. Fadiga, D. Ricci, Single walled carbon nanohorns composite for neural sensing and stimulation, Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 271 (2018) 280-288. [CrossRef]

- X. Luo, C.L. Weaver, D.D. Zhou, R. Greenberg, X.T. Cui, Highly stable carbon nanotube doped poly (3, 4-ethylenedioxythiophene) for chronic neural stimulation, Biomaterials 32(24) (2011) 5551-5557. [CrossRef]

- N.A. Alba, Z.J. Du, K.A. Catt, T.D. Kozai, X.T. Cui, In vivo electrochemical analysis of a PEDOT/MWCNT neural electrode coating, Biosensors 5(4) (2015) 618-646. [CrossRef]

- H. Charkhkar, G.L. Knaack, D.G. McHail, H.S. Mandal, N. Peixoto, J.F. Rubinson, T.C. Dumas, J.J. Pancrazio, Chronic intracortical neural recordings using microelectrode arrays coated with PEDOT–TFB, Acta Biomaterialia 32 (2016) 57-67. [CrossRef]

- I.M. Taylor, N.A. Patel, N.C. Freedman, E. Castagnola, X.T. Cui, Direct in vivo electrochemical detection of resting dopamine using poly (3, 4-ethylenedioxythiophene)/carbon nanotube functionalized microelectrodes, Analytical chemistry 91(20) (2019) 12917-12927. [CrossRef]

- I.M. Taylor, E.M. Robbins, K.A. Catt, P.A. Cody, C.L. Happe, X.T. Cui, Enhanced dopamine detection sensitivity by PEDOT/graphene oxide coating on in vivo carbon fiber electrodes, Biosensors and Bioelectronics 89 (2017) 400-410. [CrossRef]

- R.F. Vreeland, C.W. Atcherley, W.S. Russell, J.Y. Xie, D. Lu, N.D. Laude, F. Porreca, M.L. Heien, Biocompatible PEDOT: Nafion composite electrode coatings for selective detection of neurotransmitters in vivo, Analytical chemistry 87(5) (2015) 2600-2607. [CrossRef]

- W. Cho, F. Liu, A. Hendrix, T. Asrat, V. Connaughton, A.G. Zestos, Timed electrodeposition of PEDOT: Nafion onto carbon fiber-microelectrodes enhances dopamine detection in zebrafish retina, Journal of The Electrochemical Society 167(11) (2020) 115501. [CrossRef]

- S. Demuru, H. Deligianni, Surface PEDOT: nafion coatings for enhanced dopamine, serotonin and adenosine sensing, Journal of The Electrochemical Society 164(14) (2017) G129. [CrossRef]

- T.D. Kozai, K. Catt, Z. Du, K. Na, O. Srivannavit, M.H. Razi-ul, J. Seymour, K.D. Wise, E. Yoon, X.T. Cui, Chronic in vivo evaluation of PEDOT/CNT for stable neural recordings, IEEE transactions on biomedical engineering 63(1) (2015) 111-119. [CrossRef]

- M. Vomero, E. Castagnola, F. Ciarpella, E. Maggiolini, N. Goshi, E. Zucchini, S. Carli, L. Fadiga, S. Kassegne, D. Ricci, Highly stable glassy carbon interfaces for long-term neural stimulation and low-noise recording of brain activity, Scientific reports 7(1) (2017) 40332. [CrossRef]

- S. Nimbalkar, E. Castagnola, A. Balasubramani, A. Scarpellini, S. Samejima, A. Khorasani, A. Boissenin, S. Thongpang, C. Moritz, S. Kassegne, Ultra-capacitive carbon neural probe allows simultaneous long-term electrical stimulations and high-resolution neurotransmitter detection, Scientific reports 8(1) (2018) 6958. [CrossRef]

- R.L. McCreery, Advanced carbon electrode materials for molecular electrochemistry, Chemical reviews 108(7) (2008) 2646-2687. [CrossRef]

- B.L. Hanssen, S. Siraj, D.K. Wong, Recent strategies to minimise fouling in electrochemical detection systems, Reviews in Analytical Chemistry 35(1) (2016) 1-28. [CrossRef]

- E. He, S. Xu, Y. Dai, Y. Wang, G. Xiao, J. Xie, S. Xu, P. Fan, F. Mo, M. Wang, SWCNTs/PEDOT: PSS-modified microelectrode arrays for dual-mode detection of electrophysiological signals and dopamine concentration in the striatum under isoflurane anesthesia, ACS sensors 6(9) (2021) 3377-3386. [CrossRef]

- G. Xiao, S. Xu, Y. Song, Y. Zhang, Z. Li, F. Gao, J. Xie, L. Sha, Q. Xu, Y. Shen, In situ detection of neurotransmitters and epileptiform electrophysiology activity in awake mice brains using a nanocomposites modified microelectrode array, Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 288 (2019) 601-610. [CrossRef]

- P. Fan, Y. Wang, Y. Dai, L. Jing, W. Liang, B. Lu, G. Yang, Y. Song, Y. Wu, X. Cai, Flexible microelectrode array probe for simultaneous detection of neural discharge and dopamine in striatum of mice aversion system, Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 390 (2023) 133990. [CrossRef]

- X. Wang, M. Xu, H. Yang, W. Jiang, J. Jiang, D. Zou, Z. Zhu, C. Tao, S. Ni, Z. Zhou, Ultraflexible Neural Electrodes Enabled Synchronized Long-Term Dopamine Detection and Wideband Chronic Recording Deep in Brain, ACS nano (2024). [CrossRef]

- J.J. Burmeister, G.A. Gerhardt, Self-referencing ceramic-based multisite microelectrodes for the detection and elimination of interferences from the measurement of L-glutamate and other analytes, Analytical chemistry 73(5) (2001) 1037-1042. [CrossRef]

- J.J. Burmeister, D.A. Price, F. Pomerleau, P. Huettl, J.E. Quintero, G.A. Gerhardt, Challenges of simultaneous measurements of brain extracellular GABA and glutamate in vivo using enzyme-coated microelectrode arrays, Journal of neuroscience methods 329 (2020) 108435. [CrossRef]

- M. Clay, H.G. Monbouquette, Simulated Performance of Electroenzymatic Glutamate Biosensors In Vivo Illuminates the Complex Connection to Calibration In Vitro, ACS Chemical Neuroscience 12(22) (2021) 4275-4285. [CrossRef]

- S. Qin, M. Van der Zeyden, W.H. Oldenziel, T.I. Cremers, B.H. Westerink, Microsensors for in vivo measurement of glutamate in brain tissue, Sensors 8(11) (2008) 6860-6884. [CrossRef]

- A.A. Disney, C. McKinney, L. Grissom, X. Lu, J.H. Reynolds, A multi-site array for combined local electrochemistry and electrophysiology in the non-human primate brain, Journal of neuroscience methods 255 (2015) 29-37. [CrossRef]

- X. Liu, J. Liu, Biosensors and sensors for dopamine detection, View 2(1) (2021) 20200102. [CrossRef]

- S. Baluta, D. Zając, A. Szyszka, K. Malecha, J. Cabaj, Enzymatic platforms for sensitive neurotransmitter detection, Sensors 20(2) (2020) 423. [CrossRef]

- J.L. Scoggin, C. Tan, N.H. Nguyen, U. Kansakar, M. Madadi, S. Siddiqui, P.U. Arumugam, M.A. DeCoster, T.A. Murray, An enzyme-based electrochemical biosensor probe with sensitivity to detect astrocytic versus glioma uptake of glutamate in real time in vitro, Biosensors and Bioelectronics 126 (2019) 751-757. [CrossRef]

- U. Chae, J. Woo, Y. Cho, J.-K. Han, S.H. Yang, E. Yang, H. Shin, H. Kim, H.-Y. Yu, C.J. Lee, A neural probe for concurrent real-time measurement of multiple neurochemicals with electrophysiology in multiple brain regions in vivo, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 120(28) (2023) e2219231120. [CrossRef]

- G. Xiao, Y. Song, S. Zhang, L. Yang, S. Xu, Y. Zhang, H. Xu, F. Gao, Z. Li, X. Cai, A high-sensitive nano-modified biosensor for dynamic monitoring of glutamate and neural spike covariation from rat cortex to hippocampal sub-regions, Journal of Neuroscience Methods 291 (2017) 122-130. [CrossRef]

- W. Wei, Y. Song, L. Wang, S. Zhang, J. Luo, S. Xu, X. Cai, An implantable microelectrode array for simultaneous L-glutamate and electrophysiological recordings in vivo, Microsystems & Nanoengineering 1(1) (2015) 1-6. [CrossRef]

- C. Ziegler, W. Göpel, Biosensor development, Current opinion in chemical biology 2(5) (1998) 585-591. [CrossRef]

- G. Rocchitta, A. Spanu, S. Babudieri, G. Latte, G. Madeddu, G. Galleri, S. Nuvoli, P. Bagella, M.I. Demartis, V. Fiore, Enzyme biosensors for biomedical applications: Strategies for safeguarding analytical performances in biological fluids, Sensors 16(6) (2016) 780. [CrossRef]

- J.I. Reyes-De-Corcuera, H.E. Olstad, R. García-Torres, Stability and stabilization of enzyme biosensors: the key to successful application and commercialization, Annual review of food science and technology 9(1) (2018) 293-322. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li, Y. Bai, G. Han, M. Li, Porous-reduced graphene oxide for fabricating an amperometric acetylcholinesterase biosensor, Sensors and actuators B: Chemical 185 (2013) 706-712. [CrossRef]

- G. Sun, X. Wei, D. Zhang, L. Huang, H. Liu, H. Fang, Immobilization of enzyme electrochemical biosensors and their application to food bioprocess monitoring, Biosensors 13(9) (2023) 886. [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.C. Singh, Exploring the Potential of Enzyme-Immobilized MOFs: Biosensing, Biocatalysis, Targeted Drug Delivery and Cancer Therapy, Journal of Materials Chemistry B (2024). [CrossRef]

- J. Jang, H.-U. Cho, S. Hwang, Y. Kwak, H. Kwon, M.L. Heien, K.E. Bennet, Y. Oh, H. Shin, K.H. Lee, Understanding the different effects of fouling mechanisms on working and reference electrodes in fast-scan cyclic voltammetry for neurotransmitter detection, Analyst 149(10) (2024) 3008-3016. [CrossRef]

- S. Campuzano, M. Pedrero, P. Yáñez-Sedeño, J.M. Pingarrón, Antifouling (bio) materials for electrochemical (bio) sensing, International journal of molecular sciences 20(2) (2019) 423. [CrossRef]

- G.S. Wilson, R. Gifford, Biosensors for real-time in vivo measurements, Biosensors and Bioelectronics 20(12) (2005) 2388-2403. [CrossRef]

- B.R. Baker, R.Y. Lai, M.S. Wood, E.H. Doctor, A.J. Heeger, K.W. Plaxco, An electronic, aptamer-based small-molecule sensor for the rapid, label-free detection of cocaine in adulterated samples and biological fluids, Journal of the American Chemical Society 128(10) (2006) 3138-3139. [CrossRef]

- C. Zhao, K.M. Cheung, I.-W. Huang, H. Yang, N. Nakatsuka, W. Liu, Y. Cao, T. Man, P.S. Weiss, H.G. Monbouquette, Implantable aptamer–field-effect transistor neuroprobes for in vivo neurotransmitter monitoring, Science advances 7(48) (2021) eabj7422. [CrossRef]

- H. Chen, M. Xiao, J. He, Y. Zhang, Y. Liang, H. Liu, Z. Zhang, Aptamer-functionalized carbon nanotube field-effect transistor biosensors for Alzheimer’s disease serum biomarker detection, ACS sensors 7(7) (2022) 2075-2083. [CrossRef]

- W. Fu, L. Jiang, E.P. van Geest, L.M. Lima, G.F. Schneider, Sensing at the surface of graphene field-effect transistors, Advanced Materials 29(6) (2017) 1603610. [CrossRef]

- D. Sadighbayan, M. Hasanzadeh, E. Ghafar-Zadeh, Biosensing based on field-effect transistors (FET): Recent progress and challenges, TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 133 (2020) 116067. [CrossRef]

- N.S. Green, M.L. Norton, Interactions of DNA with graphene and sensing applications of graphene field-effect transistor devices: A review, Analytica chimica acta 853 (2015) 127-142. [CrossRef]

- R. Ziółkowski, M. Jarczewska, Ł. Górski, E. Malinowska, From small molecules toward whole cells detection: Application of electrochemical aptasensors in modern medical diagnostics, Sensors 21(3) (2021) 724. [CrossRef]

- F.V. Oberhaus, D. Frense, D. Beckmann, Immobilization techniques for aptamers on gold electrodes for the electrochemical detection of proteins: a review, Biosensors 10(5) (2020) 45. [CrossRef]

- Hepel, K. Kurzątkowska-Adaszyńska, Advances in design strategies of multiplex electrochemical aptasensors, Sensors 22(1) (2021) 161. [CrossRef]

- D. Kang, R.J. White, F. Xia, X. Zuo, A. Vallée-Bélisle, K.W. Plaxco, DNA biomolecular-electronic encoder and decoder devices constructed by multiplex biosensors, NPG Asia Materials 4(1) (2012) e1-e1. [CrossRef]

- I.M. Taylor, Z. Du, E.T. Bigelow, J.R. Eles, A.R. Horner, K.A. Catt, S.G. Weber, B.G. Jamieson, X.T. Cui, Aptamer-functionalized neural recording electrodes for the direct measurement of cocaine in vivo, Journal of Materials Chemistry B 5(13) (2017) 2445-2458. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wen, H. Pei, Y. Wan, Y. Su, Q. Huang, S. Song, C. Fan, DNA nanostructure-decorated surfaces for enhanced aptamer-target binding and electrochemical cocaine sensors, Analytical chemistry 83(19) (2011) 7418-7423. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu, L. Kong, H. Li, R. Yuan, Y. Chai, Electrochemical aptamer biosensor based on ATP-induced 2D DNA structure switching for rapid and ultrasensitive detection of ATP, Analytical Chemistry 94(18) (2022) 6819-6826. [CrossRef]

- Y. Jiang, W. Ma, W. Ji, H. Wei, L. Mao, Aptamer superstructure-based electrochemical biosensor for sensitive detection of ATP in rat brain with in vivo microdialysis, Analyst 144(5) (2019) 1711-1717. [CrossRef]

- A. Hellmann, A. Schundner, M. Frick, C. Kranz, Electrochemical detection of ATP release in-vitro and in-vivo, Current Opinion in Electrochemistry 39 (2023) 101282. [CrossRef]

- A. Azadbakht, M. Roushani, A.R. Abbasi, Z. Derikvand, Design and characterization of electrochemical dopamine–aptamer as convenient and integrated sensing platform, Analytical biochemistry 507 (2016) 47-57. [CrossRef]

- H. Abu-Ali, C. Ozkaya, F. Davis, N. Walch, A. Nabok, Electrochemical aptasensor for detection of dopamine, Chemosensors 8(2) (2020) 28. [CrossRef]

- S.N. Cuhadar, H. Durmaz, N. Yildirim-Tirgil, Multi-detection of seratonin and dopamine based on an electrochemical aptasensor, Chemical Papers 78(12) (2024) 7175-7185. [CrossRef]

- J. Li, Y. Si, Y.E. Park, J.-S. Choi, S.M. Jung, J.E. Lee, H.J. Lee, A serotonin voltammetric biosensor composed of carbon nanocomposites and DNA aptamer, Microchimica Acta 188 (2021) 1-8. [CrossRef]

- R. Li, X. Li, L. Su, H. Qi, X. Yue, H. Qi, Label-free Electrochemical Aptasensor for the Determination of Serotonin, Electroanalysis 34(6) (2022) 1048-1053. [CrossRef]

- A. Golabchi, B. Wu, B. Cao, C.J. Bettinger, X.T. Cui, Zwitterionic polymer/polydopamine coating reduce acute inflammatory tissue responses to neural implants, Biomaterials 225 (2019) 119519. [CrossRef]

- Q. Yang, B. Wu, J.R. Eles, A.L. Vazquez, T.D. Kozai, X.T. Cui, Zwitterionic polymer coating suppresses microglial encapsulation to neural implants in vitro and in vivo, Advanced biosystems 4(6) (2020) 1900287. [CrossRef]

- P. Puthongkham, B.J. Venton, Recent Advances in Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry, Analyst 145 (2020) 1087-1102. [CrossRef]

- C. Yang, M.E. Denno, P. Pyakurel, B.J. Venton, Recent trends in carbon nanomaterial-based electrochemical sensors for biomolecules: A review, Analytica chimica acta 887 (2015) 17-37. [CrossRef]

- E. Castagnola, R. Garg, S.K. Rastogi, T. Cohen-Karni, X.T. Cui, 3D fuzzy graphene microelectrode array for dopamine sensing at sub-cellular spatial resolution, Biosensors and Bioelectronics 191 (2021) 113440. [CrossRef]

- M. Devi, M. Vomero, E. Fuhrer, E. Castagnola, C. Gueli, S. Nimbalkar, M. Hirabayashi, S. Kassegne, T. Stieglitz, S. Sharma, Carbon-based neural electrodes: Promises and challenges, Journal of Neural Engineering 18(4) (2021) 041007. [CrossRef]

- E. Castagnola, A. Ansaldo, L. Fadiga, D. Ricci, Chemical vapour deposited carbon nanotube coated microelectrodes for intracortical neural recording, physica status solidi (b) 247(11-12) (2010) 2703-2707. [CrossRef]

- E.M. Robbins, E. Castagnola, X.T. Cui, Accurate and stable chronic in vivo voltammetry enabled by a replaceable subcutaneous reference electrode, Iscience 25(8) (2022). [CrossRef]

- N.T. Rodeberg, S.G. Sandberg, J.A. Johnson, P.E. Phillips, R.M. Wightman, Hitchhiker’s guide to voltammetry: acute and chronic electrodes for in vivo fast-scan cyclic voltammetry, ACS chemical neuroscience 8(2) (2017) 221-234. [CrossRef]

- C.J. Meunier, J.D. Denison, G.S. McCarty, L.A. Sombers, Interpreting dynamic interfacial changes at carbon fiber microelectrodes using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, Langmuir 36(15) (2020) 4214-4223. [CrossRef]

- T.D.Y. Kozai, N.B. Langhals, P.R. Patel, X. Deng, H. Zhang, K.L. Smith, J. Lahann, N.A. Kotov, D.R. Kipke, Ultrasmall implantable composite microelectrodes with bioactive surfaces for chronic neural interfaces, Nature materials 11(12) (2012) 1065-1073. [CrossRef]

- H.N. Schwerdt, E. Zhang, M.J. Kim, T. Yoshida, L. Stanwicks, S. Amemori, H.E. Dagdeviren, R. Langer, M.J. Cima, A.M. Graybiel, Cellular-scale probes enable stable chronic subsecond monitoring of dopamine neurochemicals in a rodent model, Communications biology 1(1) (2018) 144. [CrossRef]

- G. Guitchounts, D. Cox, 64-channel carbon fiber electrode arrays for chronic electrophysiology, Scientific Reports 10(1) (2020) 3830. [CrossRef]

- P.R. Patel, P. Popov, C.M. Caldwell, E.J. Welle, D. Egert, J.R. Pettibone, D.H. Roossien, J.B. Becker, J.D. Berke, C.A. Chestek, High density carbon fiber arrays for chronic electrophysiology, fast scan cyclic voltammetry, and correlative anatomy, Journal of Neural Engineering 17(5) (2020) 056029. [CrossRef]

- H.N. Schwerdt, D.J. Gibson, K. Amemori, L.L. Stanwicks, T. Yoshida, M.J. Cima, A.M. Graybiel, Chronic multi-modal monitoring of neural activity in rodents and primates, Integrated Sensors for Biological and Neural Sensing, SPIE, 2021, pp. 11-17. [CrossRef]

- H. Schwerdt, K. Amemori, D. Gibson, L. Stanwicks, T. Yoshida, N. Bichot, S. Amemori, R. Desimone, R. Langer, M. Cima, Dopamine and beta-band oscillations differentially link to striatal value and motor control, Science Advances 6(39) (2020) eabb9226. [CrossRef]

- E.J. Welle, P.R. Patel, J.E. Woods, A. Petrossians, E. Della Valle, A. Vega-Medina, J.M. Richie, D. Cai, J.D. Weiland, C.A. Chestek, Ultra-small carbon fiber electrode recording site optimization and improved in vivo chronic recording yield, Journal of neural engineering 17(2) (2020) 026037. [CrossRef]

- P.R. Patel, K. Na, H. Zhang, T.D. Kozai, N.A. Kotov, E. Yoon, C.A. Chestek, Insertion of linear 8.4 μm diameter 16 channel carbon fiber electrode arrays for single unit recordings, Journal of neural engineering 12(4) (2015) 046009. [CrossRef]

- H.N. Schwerdt, M.J. Kim, S. Amemori, D. Homma, T. Yoshida, H. Shimazu, H. Yerramreddy, E. Karasan, R. Langer, A.M. Graybiel, Subcellular probes for neurochemical recording from multiple brain sites, Lab on a Chip 17(6) (2017) 1104-1115. [CrossRef]

- H.N. Schwerdt, H. Shimazu, K.-i. Amemori, S. Amemori, P.L. Tierney, D.J. Gibson, S. Hong, T. Yoshida, R. Langer, M.J. Cima, Long-term dopamine neurochemical monitoring in primates, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114(50) (2017) 13260-13265. [CrossRef]

- P.R. Patel, H. Zhang, M.T. Robbins, J.B. Nofar, S.P. Marshall, M.J. Kobylarek, T.D. Kozai, N.A. Kotov, C.A. Chestek, Chronic in vivo stability assessment of carbon fiber microelectrode arrays, Journal of neural engineering 13(6) (2016) 066002. [CrossRef]

- B. Fan, C.A. Rusinek, C.H. Thompson, M. Setien, Y. Guo, R. Rechenberg, Y. Gong, A.J. Weber, M.F. Becker, E. Purcell, Flexible, diamond-based microelectrodes fabricated using the diamond growth side for neural sensing, Microsystems & nanoengineering 6(1) (2020) 42. [CrossRef]

- M. Vomero, P. Van Niekerk, V. Nguyen, N. Gong, M. Hirabayashi, A. Cinopri, K. Logan, A. Moghadasi, P. Varma, S. Kassegne, A novel pattern transfer technique for mounting glassy carbon microelectrodes on polymeric flexible substrates, Journal of Micromechanics and Microengineering 26(2) (2016) 025018. [CrossRef]

- E. Castagnola, S. Thongpang, M. Hirabayashi, G. Nava, S. Nimbalkar, T. Nguyen, S. Lara, A. Oyawale, J. Bunnell, C. Moritz, Glassy carbon microelectrode arrays enable voltage-peak separated simultaneous detection of dopamine and serotonin using fast scan cyclic voltammetry, Analyst 146(12) (2021) 3955-3970. [CrossRef]

- S. Kassegne, M. Vomero, R. Gavuglio, M. Hirabayashi, E. Özyilmaz, S. Nguyen, J. Rodriguez, E. Özyilmaz, P. van Niekerk, A. Khosla, Electrical impedance, electrochemistry, mechanical stiffness, and hardness tunability in glassy carbon MEMS μECoG electrodes, Microelectronic Engineering 133 (2015) 36-44. [CrossRef]

- N.W. Vahidi, S. Rudraraju, E. Castagnola, C. Cea, S. Nimbalkar, R. Hanna, R. Arvizu, S.A. Dayeh, T.Q. Gentner, S. Kassegne, Epi-Intra neural probes with glassy carbon microelectrodes help elucidate neural coding and stimulus encoding in 3D volume of tissue, Journal of Neural Engineering 17(4) (2020) 046005. [CrossRef]

- N. Goshi, E. Castagnola, M. Vomero, C. Gueli, C. Cea, E. Zucchini, D. Bjanes, E. Maggiolini, C. Moritz, S. Kassegne, Glassy carbon MEMS for novel origami-styled 3D integrated intracortical and epicortical neural probes, Journal of Micromechanics and Microengineering 28(6) (2018) 065009. [CrossRef]

- E. Castagnola, N.W. Vahidi, S. Nimbalkar, S. Rudraraju, M. Thielk, E. Zucchini, C. Cea, S. Carli, T.Q. Gentner, D. Ricci, In vivo dopamine detection and single unit recordings using intracortical glassy carbon microelectrode arrays, MRS advances 3(29) (2018) 1629-1634. [CrossRef]

- E.-B.A. Faul, A.M. Broussard, D.R. Rivera, M.Y. Pwint, B. Wu, Q. Cao, D. Bailey, X.T. Cui, E. Castagnola, Batch Fabrication of Microelectrode Arrays with Glassy Carbon Microelectrodes and Interconnections for Neurochemical Sensing: Promises and Challenges, Micromachines 15(2) (2024) 277. [CrossRef]

- K.-H. Nam, M. Abdulhafez, E. Castagnola, G.N. Tomaraei, X.T. Cui, M. Bedewy, Laser direct write of heteroatom-doped graphene on molecularly controlled polyimides for electrochemical biosensors with nanomolar sensitivity, Carbon 188 (2022) 209-219. [CrossRef]

- R. Ye, D.K. James, J.M. Tour, Laser-induced graphene, Accounts of chemical research 51(7) (2018) 1609-1620. [CrossRef]

- M.G. Stanford, C. Zhang, J.D. Fowlkes, A. Hoffman, I.N. Ivanov, P.D. Rack, J.M. Tour, High-resolution laser-induced graphene. Flexible electronics beyond the visible limit, ACS applied materials & interfaces 12(9) (2020) 10902-10907. [CrossRef]

- J. Lin, Z. Peng, Y. Liu, F. Ruiz-Zepeda, R. Ye, E.L. Samuel, M.J. Yacaman, B.I. Yakobson, J.M. Tour, Laser-induced porous graphene films from commercial polymers, Nature Communications 5(1) (2014) 5714. [CrossRef]

- T.S.D. Le, H.P. Phan, S. Kwon, S. Park, Y. Jung, J. Min, B.J. Chun, H. Yoon, S.H. Ko, S.W. Kim, Recent advances in laser-induced graphene: mechanism, fabrication, properties, and applications in flexible electronics, Advanced Functional Materials 32(48) (2022) 2205158. [CrossRef]

- M. Abdulhafez, G.N. Tomaraei, M. Bedewy, Fluence-dependent morphological transitions in laser-induced graphene electrodes on polyimide substrates for flexible devices, ACS Applied Nano Materials 4(3) (2021) 2973-2986. [CrossRef]

- J. Li, Y. Liu, L. Yuan, B. Zhang, E.S. Bishop, K. Wang, J. Tang, Y.-Q. Zheng, W. Xu, S. Niu, A tissue-like neurotransmitter sensor for the brain and gut, Nature 606(7912) (2022) 94-101. [CrossRef]

- Y. Lee, M.J. Low, D. Yang, H.K. Nam, T.-S.D. Le, S.E. Lee, H. Han, S. Kim, Q.H. Vu, H. Yoo, Ultra-thin light-weight laser-induced-graphene (LIG) diffractive optics, Light: Science & Applications 12(1) (2023) 146. [CrossRef]

- M. Johnson, R. Franklin, K. Scott, R. Brown, D. Kipke, Neural probes for concurrent detection of neurochemical and electrophysiological signals in vivo, 2005 IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology 27th Annual Conference, IEEE, 2006, pp. 7325-7328. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhang, Y. Song, M. Wang, Z. Zhang, X. Fan, X. Song, P. Zhuang, F. Yue, P. Chan, X. Cai, A silicon based implantable microelectrode array for electrophysiological and dopamine recording from cortex to striatum in the non-human primate brain, Biosensors and Bioelectronics 85 (2016) 53-61. [CrossRef]

- J.A. Stamford, P. Palij, C. Davidson, C.M. Jorm, J. Millar, Simultaneous “real-time” electrochemical and electrophysiological recording in brain slices with a single carbon-fibre microelectrode, Journal of neuroscience methods 50(3) (1993) 279-290. [CrossRef]

- J.F. Cheer, M.L. Heien, P.A. Garris, R.M. Carelli, R.M. Wightman, Simultaneous dopamine and single-unit recordings reveal accumbens GABAergic responses: implications for intracranial self-stimulation, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 102(52) (2005) 19150-19155. [CrossRef]

- L.R. Walton, N.G. Boustead, S. Carroll, R.M. Wightman, Effects of glutamate receptor activation on local oxygen changes, ACS Chemical Neuroscience 8(7) (2017) 1598-1608. [CrossRef]

- C.N. Hobbs, J.A. Johnson, M.D. Verber, R.M. Wightman, An implantable multimodal sensor for oxygen, neurotransmitters, and electrophysiology during spreading depolarization in the deep brain, Analyst 142(16) (2017) 2912-2920. [CrossRef]

- Y. Oh, C. Park, D.H. Kim, H. Shin, Y.M. Kang, M. DeWaele, J. Lee, H.-K. Min, C.D. Blaha, K.E. Bennet, Monitoring in vivo changes in tonic extracellular dopamine level by charge-balancing multiple waveform fast-scan cyclic voltammetry, Analytical chemistry 88(22) (2016) 10962-10970. [CrossRef]

- D.L. Robinson, B.J. Venton, M.L. Heien, R.M. Wightman, Detecting subsecond dopamine release with fast-scan cyclic voltammetry in vivo, Clinical chemistry 49(10) (2003) 1763-1773. 2003. [CrossRef]

- K.M.W.A.P. Hashemi, Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry Analysis of Dynamic Serotonin Reponses to Acute Escitalopram, ACS Chem Neurosci. 4(5) (2013) 715–720. [CrossRef]

- B.K. Swamy, B.J. Venton, Carbon nanotube-modified microelectrodes for simultaneous detection of dopamine and serotonin in vivo, Analyst 132(9) (2007) 876-884. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ou, A.M. Buchanan, C.E. Witt, P. Hashemi, Frontiers in electrochemical sensors for neurotransmitter detection: towards measuring neurotransmitters as chemical diagnostics for brain disorders, Analytical Methods 11(21) (2019) 2738-2755. [CrossRef]

- E.S. Bucher, R.M. Wightman, Electrochemical analysis of neurotransmitters, Annual review of analytical chemistry 8 (2015) 239-261. [CrossRef]

- C. Owesson-White, A.M. Belle, N.R. Herr, J.L. Peele, P. Gowrishankar, R.M. Carelli, R.M. Wightman, Cue-evoked dopamine release rapidly modulates D2 neurons in the nucleus accumbens during motivated behavior, Journal of Neuroscience 36(22) (2016) 6011-6021. [CrossRef]

- P. Takmakov, C.J. McKinney, R.M. Carelli, R.M. Wightman, Instrumentation for fast-scan cyclic voltammetry combined with electrophysiology for behavioral experiments in freely moving animals, Review of Scientific Instruments 82(7) (2011). [CrossRef]

- E.S. Bucher, K. Brooks, M.D. Verber, R.B. Keithley, C. Owesson-White, S. Carroll, P. Takmakov, C.J. McKinney, R.M. Wightman, Flexible software platform for fast-scan cyclic voltammetry data acquisition and analysis, Analytical chemistry 85(21) (2013) 10344-10353. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhang, S.-C. Lin, M.A. Nicolelis, Spatiotemporal coupling between hippocampal acetylcholine release and theta oscillations in vivo, Journal of Neuroscience 30(40) (2010) 13431-13440. [CrossRef]

- A. Ledo, C.F. Lourenço, J. Laranjinha, G.A. Gerhardt, R.M. Barbosa, Combined in vivo amperometric oximetry and electrophysiology in a single sensor: A tool for epilepsy research, Analytical chemistry 89(22) (2017) 12383-12390. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).