1. Introduction

Type 2 endoleaks (T2E) may be diagnosed in up to 40% of endovascular aortic repair (EVAR) interventions, either in the early or later during the follow-up [

1]. Despite the amount of problem, the true natural history is unknown [

2]. In most of the cases, T2E resolve spontaneously within six-months; nonetheless, it has been also reported that persistent or late-onset T2E may be associated with sac enlargement leading to aneurysm rupture or the need for endovascular rescues or even surgical conversion [

3,

4,

5]. Preventive embolization of aortic collateral branches [inferior mesenteric artery (IMA), lumbar arteries, accessory renal arteries] has been proposed as a strategy to limit the incidence of T2E, as well as to prevent those potential life-threatening events [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Although recent professional vascular society guidelines advised against any kind of routine additional pre-emptive embolization during EVAR, evidence on the potential benefits is limited and sometimes conflicting [

1,

13]. The aim of our study was to evaluate the results of the preemptive embolization of the collateral branches of the abdominal aorta in patients undergoing standard bifurcated EVAR, in comparison with patients undergoing standard EVAR without embolization.

2. Materials and Methods

Ethical Statement. Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments were respected. The study observational study has been submitted to the local Ethics Committee. The data underlying this article are available in the article.

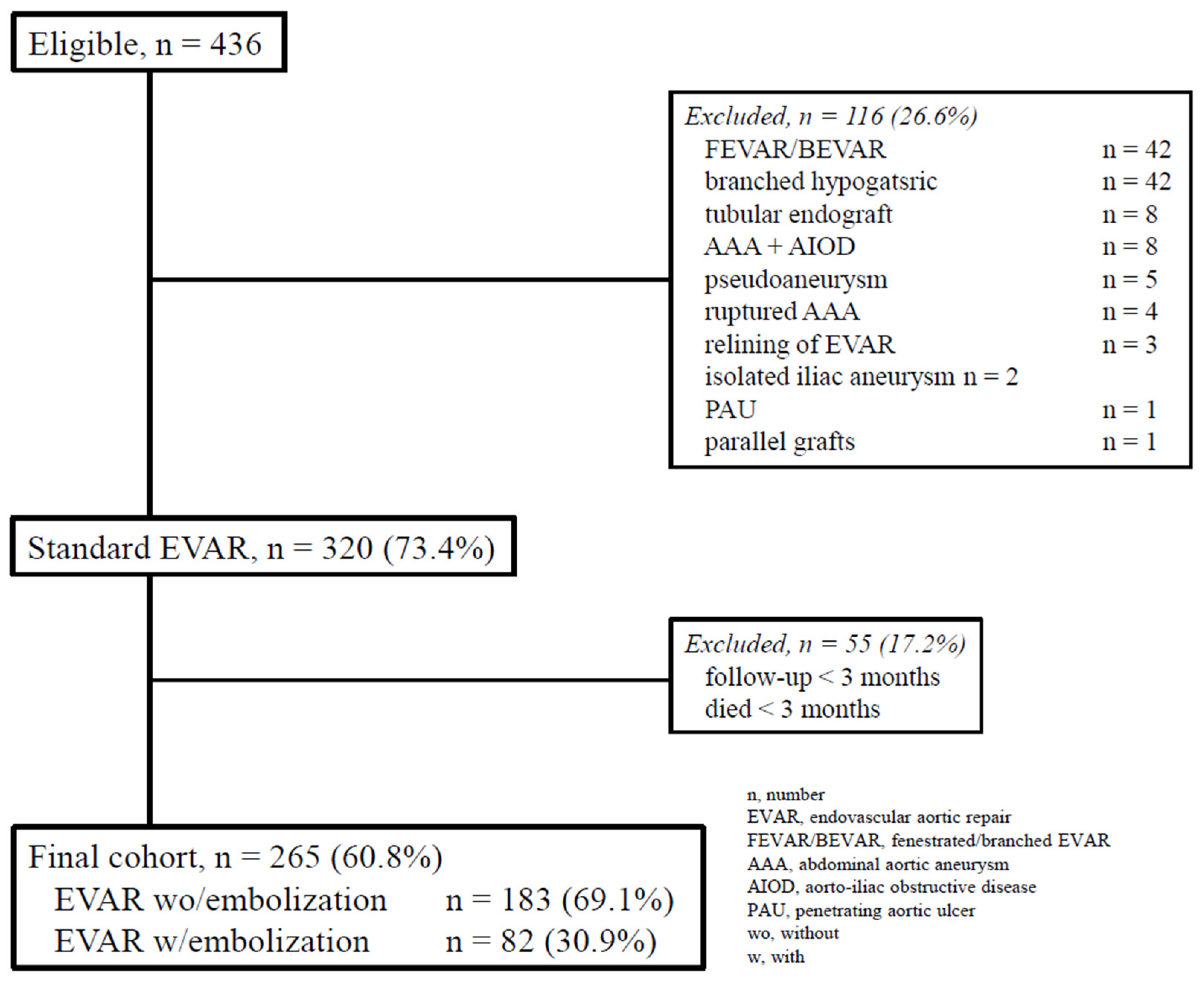

Study cohort. This is a single-center, retrospective, observational cohort study. Checklist of items followed the STROBE statement [

14]. Clinical data were recorded in a dedicated database and analyzed retrospectively. For the purposes of the present study, only data from consecutive patients treated with EVAR between October 1st, 2013, and December 31st, 2022, were identified (

Figure 1).

The inclusion criteria were as follows:

Exclusion criteria were as follows:

VAR for symptomatic or ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA)

EVAR for penetrating aortic ulcer, isolated infrarenal dissection, abdominal aortic trauma

complex EVAR (e.g., fenestrated, branched, parallel grafts, endoanchors)

EVAR performed with tubular endograft (isolate aortic cuff, aorto-uni-iliac)

missing clinical or morphologic data

absence of follow-up data

Information collected included patient demographics, co-morbidities, morphologic characteristics of the aortic lesion, anatomic pattern of the aortic collateral branches, and postoperative events (mortality, endoleaks, reinterventions) both during hospitalization and follow-up.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Preoperative Work-Up

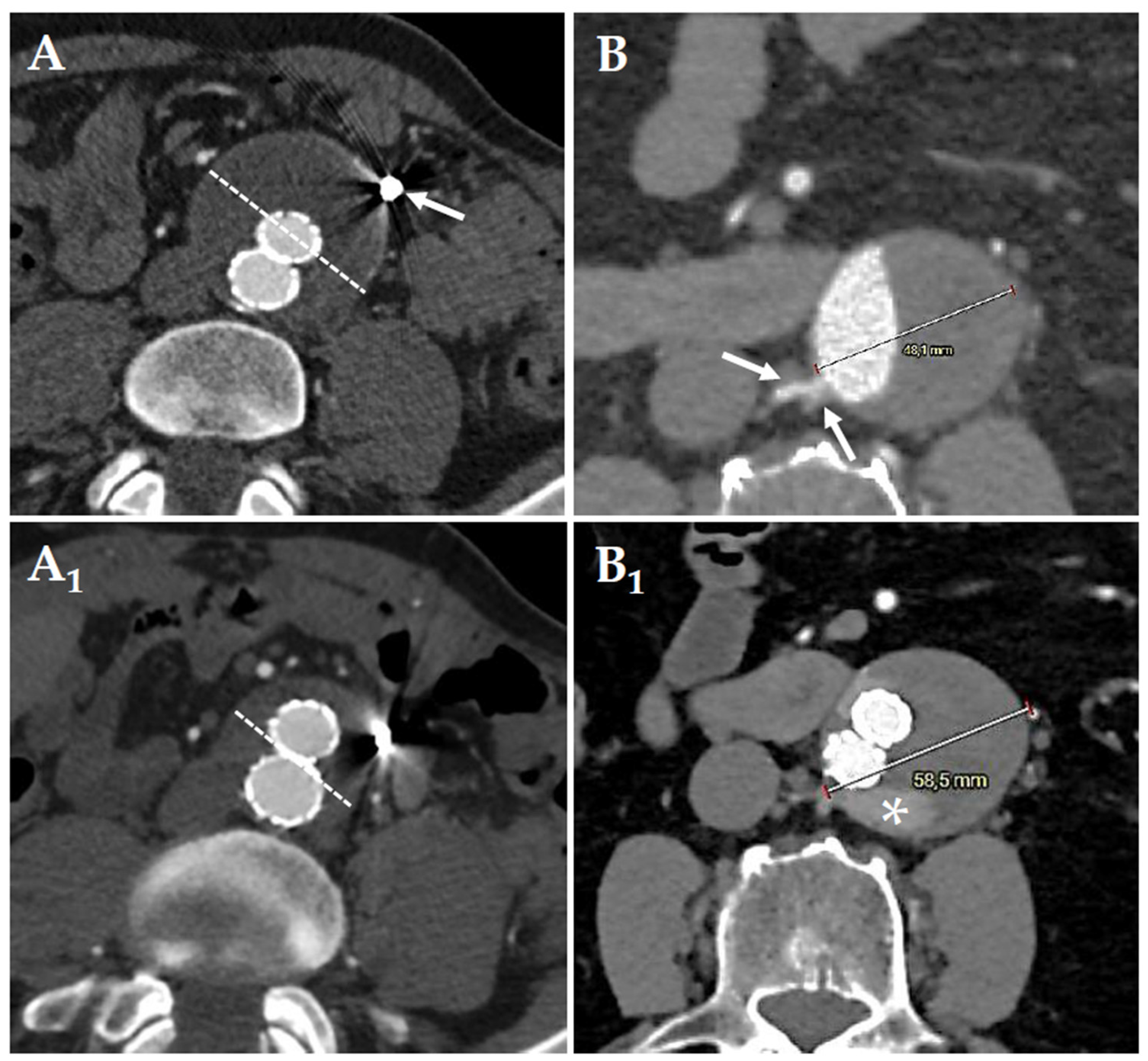

All patients underwent preoperative thoraco-abdominal computed tomography-angiography (CT-A) with acquisitions in the arterial and venous phase [

15] The software used We used a dedicated software (3Mensio

® – Pie Medical Imaging; NDL) for image reconstruction and volumetric calculation of the AAA sac. Per institutional approach, was analyzed by two different operators with >10 year of EVAR experience. Aortic measurements included maximum diameters, patency of the IMA and its diameter estimated at 10mm from the origin, number of lumbar arteries, sac thrombus calculated in percentage as the ratio of area occupied by the thrombus to area of the aneurysm at the point of maximum transverse diameter.

Operative Indications and Postoperative Surveillance

All interventions were performed according to the national guidelines of the Italian Society for Vascular and Endovascular Surgery (SICVE), also consistent with the most recent clinical practice guidelines on the management of abdominal aorto-iliac artery aneurysms of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) [

1,

14]. For patients included in this cohort, device selection as well as operative planning was left to surgeon’s judgment and was made according to the instructions for use of the manufacturer. Indication for aortic collateral branches embolization were as follow:

IMA, when the diameter was >3mm in diameter

lumbar or sacral arteries, when >2 in number and/or >3mm in diameter

Accessory renal artery embolization was performed to obtain an adequate landing zone at the proximal aortic neck or because they originated from the aneurysmal sac. Embolization was performed in all patients the day before EVAR through an ultrasound-guided percutaneous radial or common femoral artery access at the operator’s discretion. Through a 4Fr reverse curved catheter (Bernstein

® – Cordis; Santa Clara – CA; USA), the collateral branch was engaged; a 300-cm long floppy 0.014-inch guidewire (Pilot

® – Abbott; Lake County – IL; USA) was advanced into the collateral branch followed by a microcatheter (Dirextion™ – Boston Scientific; Marlborough – MA; USA). We used always detachable controlled-release coils (Tornado

® or Nester

® – Cook Inc.; Bloomington – IN; USA) or microvascular plug (MVP™ – Medtronic; Minneapolis – MN). For the IMA embolization, were precisely deployed between the origin of the IMA to just before the left colic artery branch, to preserve collateral circulation to the left colon via the arc of Riolan and marginal artery of Drummond. For lumbar arteries we did not use liquid agents to avoid peripheral migration and the subsequent risk of spinal cord ischemia. The follow-up protocol included a CT-A within two-months after EVAR followed by contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) every six-months during the first 2-years, and annually thereafter. A new CT-A was performed only in case of endoleak detection or aneurysm sac increase (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). During the follow-up, we evaluate T2E embolization in case of significant sac increase.

Definitions and Outcomes

Diameter and volume change were calculated at the last available CT-A, or at the time of aortic reintervention, or at the time of death if a definitive imaging study of the endograft (EG) was obtained during the patient’s terminal illness. A persistent T2E was defined if present beyond six-months after EVAR. Aneurysm sac shrinkage was defined as diameter reduction ≥1 cm according to Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS) reporting standards [

15,

16]. Significant sac enlargement was defined in case of ≥5mm diameter enlargement in comparison with the baseline preoperative CT-A. The cause of death was classified as verified only when based on autopsy findings, direct surgical observation, or imaging studies obtained during the patient’s terminal illness. The follow-up index (FUI) describes the completeness of follow-up at a given study end date and ratio of the period investigated to the potential follow-up period [

17]. The study closed December 31st, 2024: information on the aorta-related reintervention, vital status, and date of death of the individual patient was validated by death certificates, electronic records maintained by the regional health system, through interview with the general practitioner, or data certified by admission to the emergency room. For this specific study, the primary outcomes were overall survival and the freedom from aorta-related mortality (ARM), as well as the freedom from T2E-related reintervention. In case of multiple reinterventions, this latter was calculated at the first one. The secondary outcome was the assessment of freedom from aneurysm sac increase.

Statistical Analysis [18]

Clinical data were collected in a prospective manner in a single database, recorded, and tabulated in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, Wash) and analyzed retrospectively. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS, release 29.0 for Windows (IBM SPSS Inc.; Chicago – Ill; USA). Continuous variables were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk’s test and compared between groups with unpaired Student’s T-test for normally distributed values; otherwise, the Mann-Whitney U test was used. Variables that were normally distributed are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and range; otherwise, they are presented as median and 25th-75th interquartile (IQR). Categorical variables were presented using frequencies and percentages and analyzed with the Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test whether the expected cell frequencies were <5. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to evaluate the difference in covariate measurements before and after EVAR. Multivariable analysis was used to adjust the relationship between type of EVAR and 30-day mortality and survival, as well as T2E-related reintervention or sac increase. Associations that yielded a P value <0.20 on univariate screen were then included in a binary logistic regression analysis using the Wald’s forward stepwise model. The strength of the association of variables with each primary outcome was estimated by calculating the odd ratio (OR) and 95%CI (95%CI): significance criteria 0.20 for entry, 0.05 for removal. Follow-up freedom from ARM and freedom from EVAR-related reintervention were estimated according to Kaplan-Meier method and reported with standard error (SE), and associated 95%CI. The Breslow-rank test was used for any possible comparison in the follow-up of the different covariates. Time-dependent coefficients were included in Cox proportional hazards regression and survival. In addition, the estimation of need for T2E-related reintervention were implemented with a proportional hazards model proposed by Fine & Gray to consider the presence of competitive risks. All reported P values were two-sided; P value <0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

Study Cohort

Out of 436 EVARs, 265 (60.8%) were included in the final analysis: 183 (69.1%) underwent EVAR without prior embolization (group A), and 82 (30.9%) received preemptive embolization during EVAR (group B).

Table 1 reports demographic data and comorbidities: briefly, group A showed a higher ratio of female gender [n = 20 (10.9%) vs. 2 (2.5%); OR: 3.6, P = 0.028], and a higher median of age [77 (IQR, 70-81) vs. 73.5 (67-77), P = 0.001].

The vast majority [n = 238, (89.8%)] of the patient had a patent IMA, 14 (5.3%) had a mixed pattern (IMA and/or lumbar and/or accessory renal), and 13 (4.9%) had only lumbar artery patent. As far as anatomic measurements are concerned, only median IMA diameter was higher in group B [mm, 2.7 (2.3-3) vs. 3.6 (3.3-4), P < 0.001]; there were no further differences between the groups (

Table 2).

The number of patients with >3 pairs of lumbar arteries was similar in the two groups [n = 164 (89.6%) vs. 76 (92.7%); OR: 1.5, P = 0.502). In group B, one vessel was embolized in 64 (78.0%) cases, and 18 (22.0%) had two or more vessels embolized.

Outcomes Analysis

Operative mortality was never observed. Technical success was achieved in all cases. Visceral or spinal cord ischemic complications correlated with preemptive embolization did not occur. The median of follow-up was 48 months (IQR, 28-65.5), and it was not different between the two groups [45 (26-63) vs. 52.5 (29.5-72.5), P = 0.098]. The mean of follow-up index was 0.7 ± 0.3 (range, 0-1), and it was not different between the two groups (0.65 ± 0.3 vs. 0.70 ± 0.2, P = 0.158).

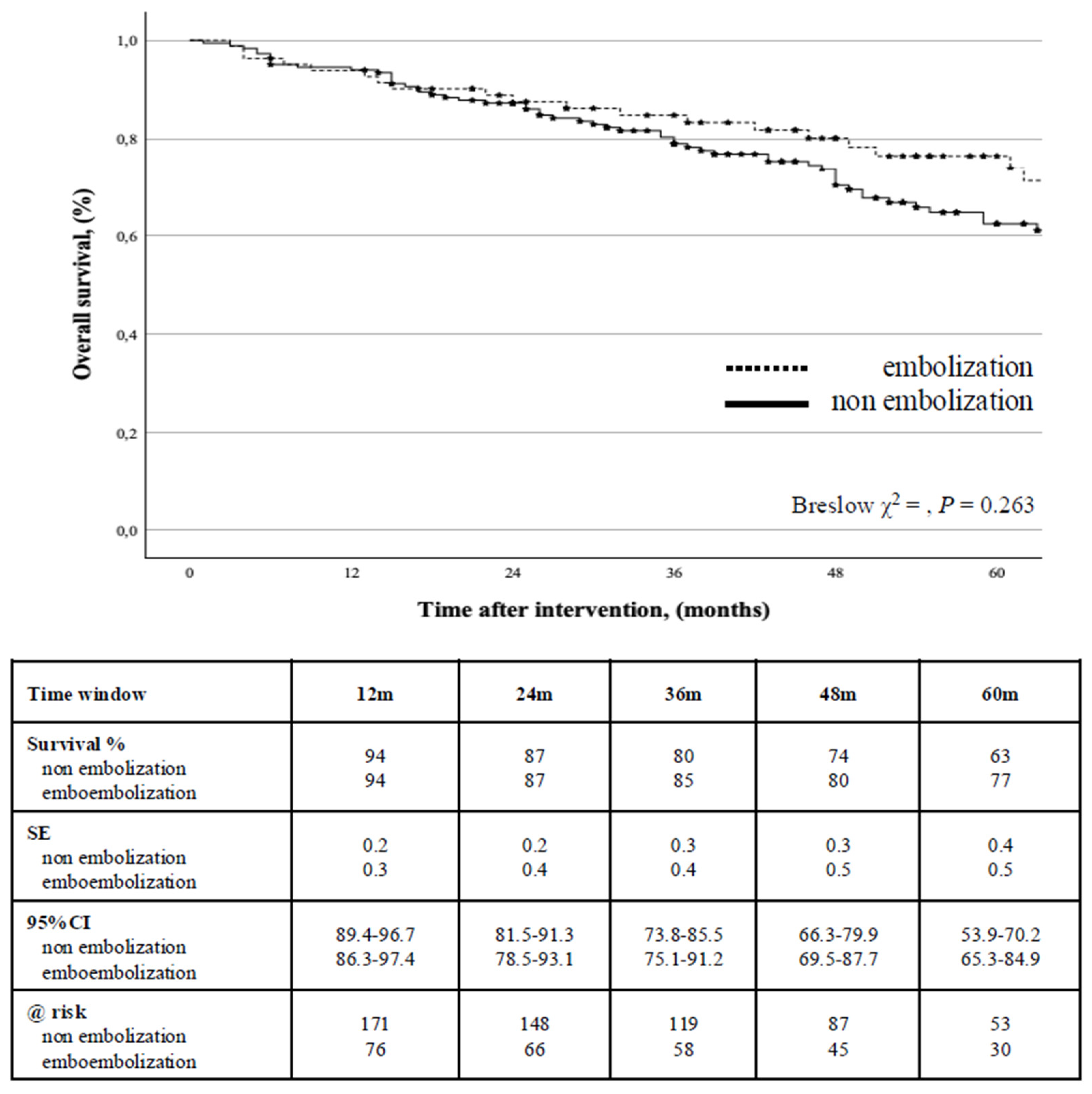

a. Survival

During the follow-up, 81 (30.6%) patients died; the estimated cumulative survival was 87% (0.2) at 2-years (95%CI: 82.6-92.9) and 67% (0.3) at 5-years (95%CI: 60.3-73.1) with no difference between the groups (P = 0.263) (

Figure 3).

Aorta-related mortality rate was 1.1% (n = 3): all of them occurred after open conversion due to EG infection (n = 2), and secondary aortic rupture (n = 1). Univariate screen identified that age >80-years, and aneurysm sac increase during the follow-up to be associated with survival; however, Cox’s regression analysis identified only age >80-years to be an independent negative predictor of survival (HR: 3.5, 95%CI: 2.27-5.50, P < 0.001,

Table 3) was associated with this outcome even when stratified for type of EVAR strategy (P < 0.001).

b. Reintervention for Endoleak

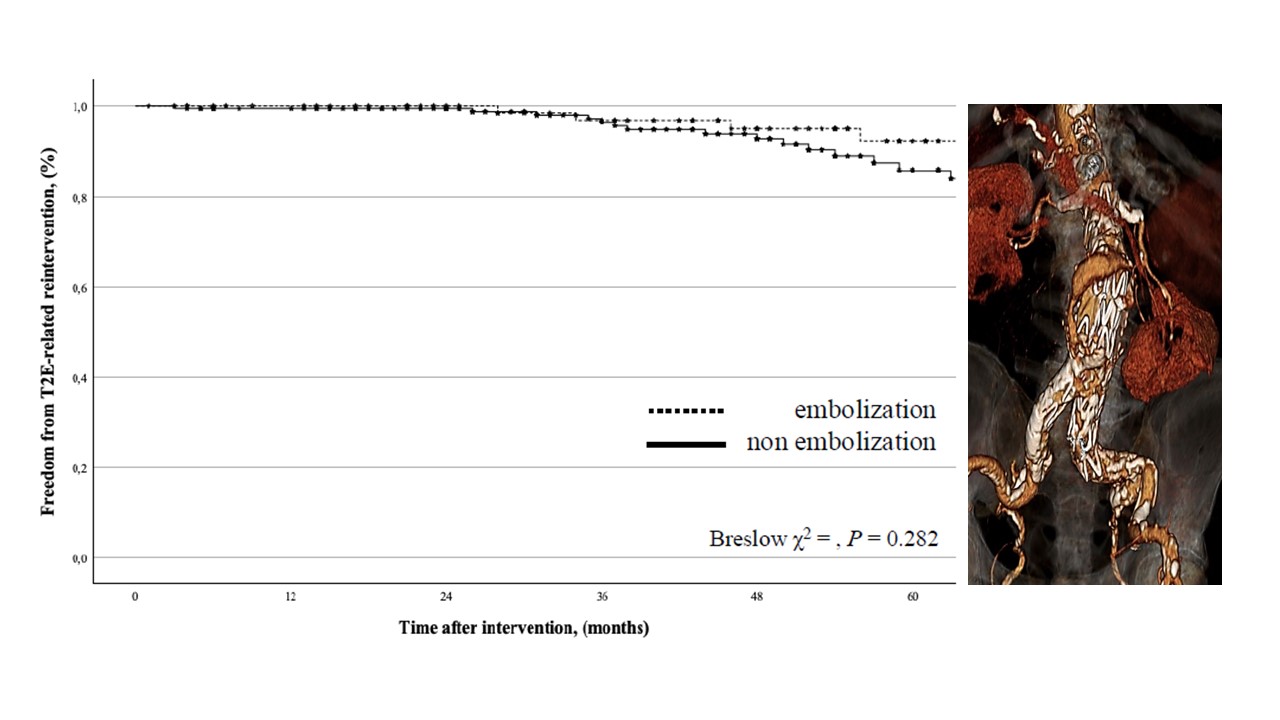

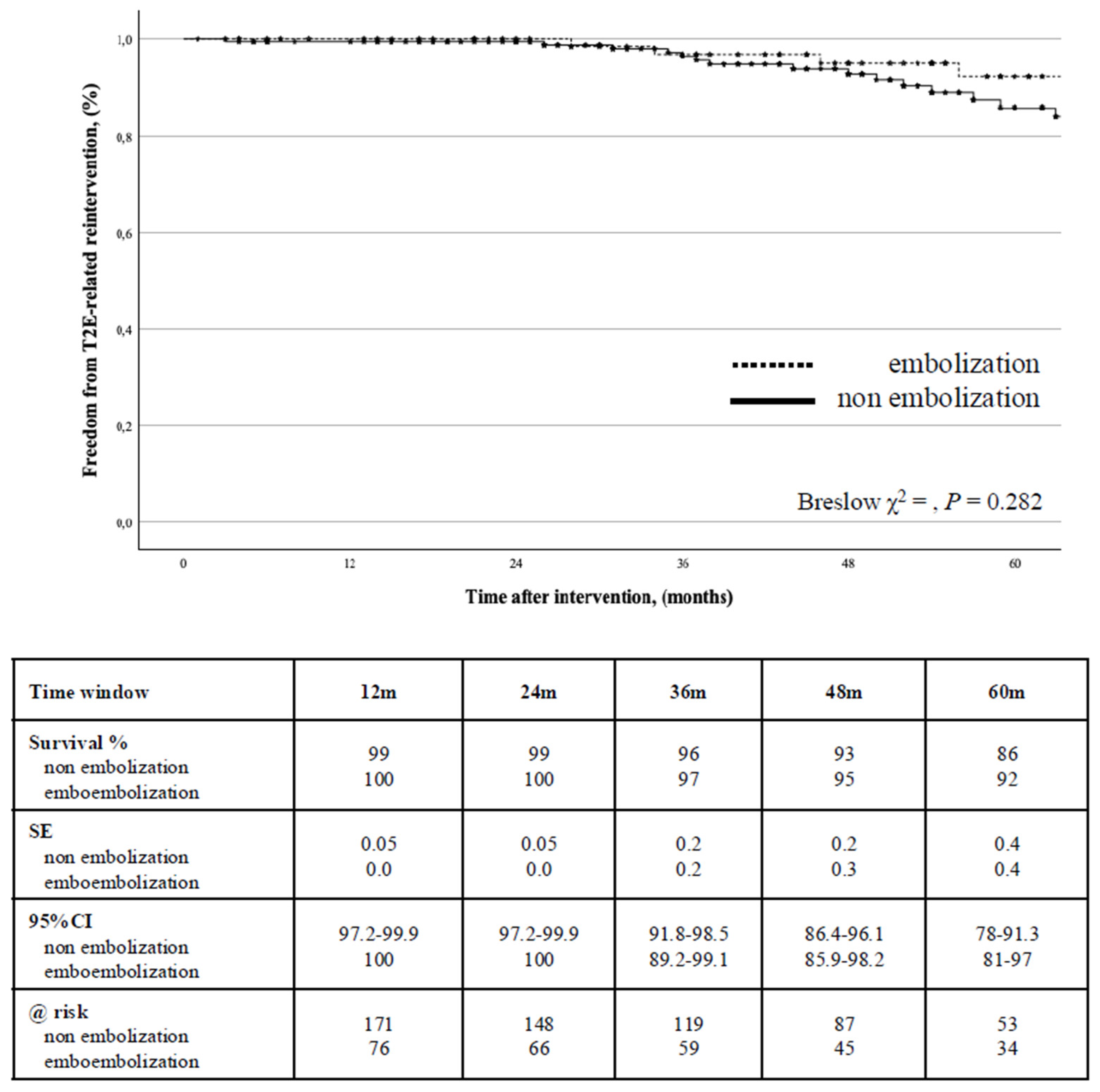

A T2E-related reintervention for endoleak was indicated in 34 (12.8%) cases. The freedom from T2E-related reintervention was 99% (0.01) at 2-years (95%CI: 99.4-99.8) and 88% (0.3) at 5-years (95%CI: 81.4-92.5): there was no difference between the groups (P = 0.282) (

Figure 4).

Univariate screen identified that age >80-years, smoking habit, conic shape of the proximal aortic neck, and the presence of more than three pairs of patent lumbar arteries were associated with T2E-related reintervention: at Cox’s regression analysis, only age > 80-years (HR: 2.4, 95%CI: 1.05-5.54, P = 0.037,

Table 3) was associated with this outcome even when stratified for type of EVAR strategy (P = 0.048).

c. Conversion to Open Repair

Conversion to open repair was necessary in 14 (5.3%) patients. Secondary aortic rupture occurred in 3 (1.1%) cases: it was never determined by T2E but always correlated to type 1 endoleak. In 3 (1.1%) indication for open conversion was EG infection, but only 1 occurred with type 1 endoleak. The freedom from open conversion was 99% (0.05) at 2-years (95%CI: 97.5-99.7) and 95% (0.3) at 5-years (95%CI: 90.3-97.6): there was no difference between the groups (P = 0.858). No covariate was associated with conversion to open repair at Cox’s regression analysis.

d. Sac Evolution

There were not differences between the groups either in terms of sac shrinkage (P = 0.783) or sac enlargement (P = 0.239). We detected 98 (37.0%) endoleaks: 23 (8.7%) type 1, 72 (27.9 %) type 2, while in 1 (0.4%) case we observed a combination of the two types. No type 3 endoleak was observed. The types of endoleak were not different between the groups (P = 0.847). At the last available CT-A the median of aneurysm diameter was lower in group B [mm, 48 (39-57.5) vs. 44 (37.7-50), P < 0.001] with a significant change from the baseline measurement in both groups (P = 0.001). The stability of the sac or any sac diameter decrease was observed in 166 (62.6%) cases; an increase in sac diameter was detected in 49 (18.5%) cases and was a significant enlargement in 35 (13.2%). Univariate screen identified that age >80-years, smoking habit, hypertension, and the presence of more than three pairs of patent lumbar arteries were associated with sac enlargement, but Cox’s regression analysis did not identify significant association with any of these variables; only age > 80-years (HR: 2.1, 95%CI: 0.97-4.62, P = 0.058) showed to increase the risk for sac enlargement.

4. Discussion

The main finding of our analysis is twofold: preemptive embolization of the aortic collateral branches during EVAR does not seem to protect from EVAR-related complications and reintervention, and age >80-years is the most important predictor for major aorta-related outcomes. Since the first phases of the EVAR era, it has been clear from several different studies that aorta-related reinterventions have been the major drawback of EVAR especially in the long-term follow-up, and primarily correlated to the development and consequences of persistent T2E [

6,

19]. Robust evidence on the potential benefits of preemptive embolization during EVAR has been limited with conflicting results. Data from the literature reported that preemptive embolization may reduce the risk of T2E in the mid-term, but this benefit did not appear to translate into a reduction of EVAR-related reinterventions [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Our experience is consistent with these findings in the light of the fact that despite a high rate of positive remodeling of the aneurysmatic sac, namely a significant shrinkage, preemptive embolization did not protect from T2E-related reinterventions. There is plenty of literature that reported several different predictors for reintervention, being age >80-years the most important in our series [

20]. Give an unquestionable explanation why ageing patients should be more prone to T2E-related reintervention is impossible at this time; nevertheless, our data may find robust support in several experiences that reported a significantly increased risk of reintervention after EVAR in octogenarians [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Furthermore, age is an important issue in all surgical scenarios because older patients generally have a higher operative risk. As far as octogenarians are concerned, our experience confirms the results of the literature showing that life expectancy in octogenarians was significantly poorer [

23]. Considering the higher reintervention rate and the fact that a greater proportion of the population lives longer, factors such as life expectancy, risks involved in the procedure, may increase the attention toward careful patient selection especially in the older cohort. Evaluating the risk of reintervention, anatomic variables may play an important role especially after EVAR. Among the several covariates that have been associated with the risk of reintervention, the diameter of the IMA, the number of patent lumbar arteries, and the proportion of maximum aneurysm area occupied by thrombus have been identified at higher risk of a persistent T2E [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. In that anatomic circumstances, preemptive embolization has been advised to be potentially useful to limit the occurrence of persistent T2E and was initially intended to protect against life-threatening complications such as rupture and/or the need of open conversion. [

6,

7] Our analysis shows that preemptive embolization of aortic collateral branches does not confer a better protection against reintervention and open conversion notwithstanding the positive remodeling of the aneurysmatic sac. However, also another embolization strategy such as sac filling failed to prevent persistent T2E occurrence and reinterventions. Nonetheless, we can re-evaluate the glass half-full of this circumstance; secondary ruptures and aorta-related mortality never occurred in case of persistent T2E so that this condition should not be considered a malignant condition as some authors have considered it [

15,

32,

33,

34]. Therefore, all these data support the recent ESVS guidelines that advised against any kind of routine additional pre-emptive embolization during EVAR [

1,

13].

5. Conclusions

Our analysis seems to confirm that preemptive embolization of the aortic collateral branches during EVAR does not confer better aorta-related outcomes and that older age, namely >80-years, is a powerful predictor of poorer outcomes. Further, despite embolization failed against reintervention, the presence of persistent T2E cannot be considered a malignant condition owing to the absence of secondary rupture or significant increased risk of correlated reinterventions.

Author Contributions

Study design: R.B.; Data collection: all Authors and Collaborators; Data analysis: R.B.; Writing: R.B.; Critical revision and final approval: all Authors and Collaborators; Obtained funding: None; Overall responsibility: R.B.; Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study observational study has been submitted to the local Ethic Committee

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the analysis.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Schlösser FJ, Gusberg RJ, Dardik A, Lin PH, Verhagen HJ, Moll FL, Muhs BE. Aneurysm rupture after EVAR: can the ultimate failure be predicted? Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2009;37:15-22.

- Wanhainen A, Van Herzeele I, Bastos Goncalves F, Bellmunt Montoya S, Berard X, Boyle JR, D’Oria M, Prendes CF, Karkos CD, Kazimierczak A, Koelemay MJW, Kölbel T, Mani K, Melissano G, Powell JT, Trimarchi S, Tsilimparis N; ESVS Guidelines Committee; Antoniou GA, Björck M, Coscas R, Dias NV, Kolh P, Lepidi S, Mees BME, Resch TA, Ricco JB, Tulamo R, Twine CP; Document Reviewers; Branzan D, Cheng SWK, Dalman RL, Dick F, Golledge J, Haulon S, van Herwaarden JA, Ilic NS, Jawien A, Mastracci TM, Oderich GS, Verzini F, Yeung KK. Editor’s Choice -- European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2024 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Abdominal Aorto-Iliac Artery Aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2024;67:192-331. [CrossRef]

- Rayt HS, Sandford RM, Salem M, Bown MJ, London NJ, Sayers RD. Conservative management of type 2 endoleaks is not associated with increased risk of aneurysm rupture. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2009;38:718-23. [CrossRef]

- Sidloff DA, Stather PW, Choke E, Bown MJ, Sayers RD. Type II endoleak after endovascular aneurysm repair. Br J Surg 2013;100:1262-1270.

- D’Oria M, Mastrorilli D, Ziani B. Natural History, Diagnosis, and Management of Type II Endoleaks after Endovascular Aortic Repair: Review and Update. Ann Vasc Surg 2020;62:420-431. [CrossRef]

- Yu HYH, Lindström D, Wanhainen A, Tegler G, Asciutto G, Mani K. An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of pre-emptive aortic side branch embolization to prevent type II endoleaks after endovascular aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg 2023;77:1815-1821. [CrossRef]

- Li Q, Hou P. Sac Embolization and Side Branch Embolization for Preventing Type II Endoleaks After Endovascular Aneurysm Repair: A Meta-analysis. J Endovasc Ther 2020;27:109-116. [CrossRef]

- Branzan D, Geisler A, Steiner S, Doss M, Matschuck M, Scheinert D, Schmidt A. Type II endoleak and aortic aneurysm sac shrinkage after preemptive embolization of aneurysm sac side branches. J Vasc Surg 2021;73:1973-1979.e1. [CrossRef]

- Rokosh RS, Chang H, Butler JR, Rockman CB, Patel VI, Milner R, Jacobowitz GR, Cayne NS, Veith F, Garg K. Prophylactic sac outflow vessel embolization is associated with improved sac regression in patients undergoing endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg 2022;76:113-121.e8. [CrossRef]

- Kontopodis N, Galanakis N, Kiparakis M, Ioannou CV, Kakisis I, Geroulakos G, Antoniou GA. Pre-Emptive Embolization of the Aneurysm Sac or Aortic Side Branches in Endovascular Aneurysm Repair: Meta-Analysis and Trial Sequential Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Ann Vasc Surg 2023;91:90-107. [CrossRef]

- Väärämäki S, Viitala H, Laukontaus S, Uurto I, Björkman P, Tulamo R, Aho P, Laine M, Suominen V, Venermo M. Routine Inferior Mesenteric Artery Embolisation is Unnecessary Before Endovascular Aneurysm Repair. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2023;65:264-270. [CrossRef]

- Fukuda T, Matsuda H, Tanaka H, Sanda Y, Morita Y, Seike Y. Chew DK, Dong S, Schroeder AC, Hsu HW, Franko J. The role of the inferior mesenteric artery in predicting secondary intervention for type II endoleak following endovascular aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg 2019;70:1463-1468.

- Pratesi C, Esposito D, Apostolou D, Attisani L, Bellosta R, Benedetto F, Blangetti I, Bonardelli S, Casini A, Fargion AT, Favaretto E, Freyrie A, Frola E, Miele V, Niola R, Novali C, Panzera C, Pegorer M, Perini P, Piffaretti G, Pini R, Robaldo A, Sartori M, Stigliano A, Taurino M, Veroux P, Verzini F, Zaninelli E, Orso M; Italian Guidelines for Vascular Surgery Collaborators - AAA Group. Guidelines on the management of abdominal aortic aneurysms: updates from the Italian Society of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery (SICVE). J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2022;63:328-352. [CrossRef]

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Epidemiology 2007;18:800-804.

- Franchin M, Serafini M, Tadiello M, Fontana F, Rivolta N, Venturini M, Curti M, Bush RL, Dorigo W, Piacentino F, Tozzi M, Piffaretti G. A morphovolumetric analysis of aneurysm sac evolution after elective endovascular abdominal aortic repair. J Vasc Surg 2021;74:1222-1231.e2. [CrossRef]

- Chaikof EL, Dalman RL, Eskandari MK, Jackson BM, Lee WA, Mansour MA, et al. The Society for Vascular Surgery practice guidelines on the care of patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg 2018;67:2-77.e2. [CrossRef]

- von Allmen RS, Weiss S, Tevaearai HT, Kuemmerli C, Tinner C, Carrel TP, Set al. Completeness of Follow-Up Determines Validity of Study Findings: Results of a Prospective Repeated Measures Cohort Study. PLoS One 2015;10:e0140817.

- Hickey GL, Dunning J, Seifert B, Sodeck G, Carr MJ, Burger HU, et al. EJCTS and ICVTS Editorial Committees. Statistical and data reporting guidelines for the European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery and the Interactive CardioVascular and Thoracic Surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2015;48:180-193. [CrossRef]

- van Marrewijk CJ, Fransen G, Laheij RJ, Harris PL, Buth J; EUROSTAR Collaborators. Is a type II endoleak after EVAR a harbinger of risk? Causes and outcome of open conversion and aneurysm rupture during follow-up. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2004;27:128-137. [CrossRef]

- Lomazzi C, Mariscalco G, Piffaretti G, Bacuzzi A, Tozzi M, Carrafiello G, Castelli P. Endovascular treatment of elective abdominal aortic aneurysms: independent predictors of early and late mortality. Ann Vasc Surg 2011;25:299-305. [CrossRef]

- Brown LC, Greenhalgh RM, Powell JT, Thompson SG; EVAR Trial Participants. Use of baseline factors to predict complications and reinterventions after endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Br J Surg 2010;978:1207-1217.

- Schanzer A, Greenberg RK, Hevelone N, Robinson WP, Eslami MH, Goldberg RJ, Messina L. Predictors of abdominal aortic aneurysm sac enlargement after endovascular repair. Circulation 2011;123:2848-2855. [CrossRef]

- Patel SR, Allen C, Grima MJ, Brownrigg JRW, Patterson BO, Holt PJE, Thompson MM, Karthikesalingam A. A Systematic Review of Predictors of Reintervention After EVAR: Guidance for Risk-Stratified Surveillance. Vasc Endovascular Surg 2017;51:417-428.

- Hye RJ, Janarious AU, Chan PH, Cafri G, Chang RW, Rehring TF, Nelken NA, Hill BB. Survival and Reintervention Risk by Patient Age and Preoperative Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Diameter after Endovascular Aneurysm Repair. Ann Vasc Surg 2019;54:215-225. [CrossRef]

- Rich N, Tucker LY, Okuhn S, Hua H, Hill B, Goodney P, Chang R. Long-term freedom from aneurysm-related mortality remains favorable after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in a 15-year multicenter registry. J Vasc Surg 2020;71:790-798. [CrossRef]

- Wanken ZJ, Barnes JA, Trooboff SW, Columbo JA, Jella TK, Kim DJ, Khoshgowari A, Riblet NBV, Goodney PP. A systematic review and meta-analysis of long-term reintervention after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg 2020;72:1122-1131. [CrossRef]

- Sampaio SM, Panneton JM, Mozes GI, Andrews JC, Bower TC, Kalra M, Cherry KJ, Sullivan T, Gloviczki P. Aneurysm sac thrombus load predicts type II endoleaks after endovascular aneurysm repair. Ann Vasc Surg 2005;19:302-309. [CrossRef]

- Sadek M, Dexter DJ, Rockman CB, Hoang H, Mussa FF, Cayne NS, Jacobowitz GR, Veith FJ, Adelman MA, Maldonado TS. Preoperative relative abdominal aortic aneurysm thrombus burden predicts endoleak and sac enlargement after endovascular anerysm repair. Ann Vasc Surg 2013;27:1036-1041. [CrossRef]

- Marchiori A, von Ristow A, Guimaraes M, Schönholz C, Uflacker R. Predictive factors for the development of type II endoleaks. J Endovasc Ther 2011;18:299-305. [CrossRef]

- Manunga JM, Cragg A, Garberich R, Urbach JA, Skeik N, Alexander J, Titus J, Stephenson E, Alden P, Sullivan TM. Preoperative Inferior Mesenteric Artery Embolization: A Valid Method to Reduce the Rate of Type II Endoleak after EVAR? Ann Vasc Surg 2017;39:40-47.

- Ward TJ, Cohen S, Fischman AM, Kim E, Nowakowski FS, Ellozy SH, Faries PL, Marin ML, Lookstein RA. Preoperative inferior mesenteric artery embolization before endovascular aneurysm repair: decreased incidence of type II endoleak and aneurysm sac enlargement with 24-month follow-up. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2013;24:49-55. [CrossRef]

- Steinmetz E, Rubin BG, Sanchez LA, Choi ET, Geraghty PJ, Baty J, Thompson RW, Flye MW, Hovsepian DM, Picus D, Sicard GA. Type II endoleak after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: a conservative approach with selective intervention is safe and cost-effective. J Vasc Surg 2004;39:306-313. [CrossRef]

- Jones JE, Atkins MD, Brewster DC, Chung TK, Kwolek CJ, LaMuraglia GM, Hodgman TM, Cambria RP. Persistent type 2 endoleak after endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm is associated with adverse late outcomes. J Vasc Surg 2007;46:1-8. [CrossRef]

- El Batti S, Cochennec F, Roudot-Thoraval F, Becquemin JP. Type II endoleaks after endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm are not always a benign condition. J Vasc Surg 2013;57:1291-1297. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).