Submitted:

09 January 2025

Posted:

10 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Data Sources

Participants

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ágh, T.; Kovács, G.; Supina, D.; Pawaskar, M.; Herman, B.K.; Vokó, Z.; Sheehan, D.V. A systematic review of the health-related quality of life and economic burdens of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2016, 21, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhausen, H.; Jensen, C.M. Time trends in lifetime incidence rates of first-time diagnosed anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa across 16 years in a danish nationwide psychiatric registry study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2015, 48, 845–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, M.; Bould, H.; Flouri, E.; Harrison, A.; Lewis, G.; Lewis, G.; Srinivasan, R.; Stafford, J.; Warne, N.; Solmi, F. Association of Emotion Regulation Trajectories in Childhood With Anorexia Nervosa and Atypical Anorexia Nervosa in Early Adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry 2021, 78, 1249–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, W.; Deter, H.-C.; Fiehn, W.; Petzold, E. Medical findings and predictors of long-term physical outcome in anorexia nervosa: a prospective, 12-year follow-up study. Psychol. Med. 1997, 27, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chesney, E.; Goodwin, G.M.; Fazel, S. Risks of all-cause and suicide mortality in mental disorders: a meta-review. World Psychiatry 2014, 13, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streatfeild, J.; Hickson, J.; Austin, S.B.; Hutcheson, R.; Kandel, J.S.; Lampert, J.G.; Ma, E.M.M.; Richmond, T.K.; Samnaliev, M.; Velasquez, K.; et al. Social and economic cost of eating disorders in the United States: Evidence to inform policy action. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 54, 851–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garner, D.M.; Garfinkel, P.E. Socio-cultural factors in the development of anorexia nervosa. Psychol. Med. 1980, 10, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.N.; Pumariega, A.J. Culture and Eating Disorders: A Historical and Cross-Cultural Review. Psychiatry 2001, 64, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agüera, Z.; Brewin, N.; Chen, J.; Granero, R.; Kang, Q.; Fernandez-Aranda, F.; Arcelus, J. Eating symptomatology and general psychopathology in patients with anorexia nervosa from China, UK and Spain: A cross-cultural study examining the role of social attitudes. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0173781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makino, M.; Tsuboi, K.; Dennerstein, L. Prevalence of eating disorders: a comparison of Western and non-Western countries. . 2004, 6, 49. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pike, K.M.; Dunne, P.E. The rise of eating disorders in Asia: a review. J. Eat. Disord. 2015, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fond, G.; Nemani, K.; Etchecopar-Etchart, D.; Loundou, A.; Goff, D.C.; Lee, S.W.; Lancon, C.; Auquier, P.; Baumstarck, K.; Llorca, P.-M. Association between mental health disorders and mortality among patients with COVID-19 in 7 countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA psychiatry 2021, 78, 1208–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunnell, D.; Appleby, L.; Arensman, E.; Hawton, K.; John, A.; Kapur, N.; Khan, M.; O’Connor, R.C.; Pirkis, J.; Caine, E.D. Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 468–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vindegaard, N.; Benros, M.E. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: Systematic review of the current evidence. Brain, Behav. Immun. 2020, 89, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agostino, H.; Burstein, B.; Moubayed, D.; Taddeo, D.; Grady, R.; Vyver, E.; Dimitropoulos, G.; Dominic, A.; Coelho, J.S. Trends in the Incidence of New-Onset Anorexia Nervosa and Atypical Anorexia Nervosa Among Youth During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Canada. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2137395–e2137395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilsbach, S.; Plana, M.T.; Castro-Fornieles, J.; Gatta, M.; Karlsson, G.P.; Flamarique, I.; Raynaud, J.-P.; Riva, A.; Solberg, A.-L.; van Elburg, A.A.; et al. Increase in admission rates and symptom severity of childhood and adolescent anorexia nervosa in Europe during the COVID-19 pandemic: data from specialized eating disorder units in different European countries. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Heal. 2022, 16, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otto, A.K.; Jary, J.M.; Sturza, J.; Miller, C.A.; Prohaska, N.; Bravender, T.; Van Huysse, J. Medical Admissions Among Adolescents With Eating Disorders During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pediatrics 2021, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Springall, G.; Cheung, M.; Sawyer, S.M.; Yeo, M. Impact of the coronavirus pandemic on anorexia nervosa and atypical anorexia nervosa presentations to an Australian tertiary paediatric hospital. J. Paediatr. Child Heal. 2021, 58, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, N.; Kadowaki, T.; Takanaga, S.; Shigeyasu, Y.; Okada, A.; Yorifuji, T. Longitudinal impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the development of mental disorders in preadolescents and adolescents. BMC Public Heal. 2023, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. Shingata Korona wirus kansenshoutaisaku no tame no gakkō ni okeru rinnjikyugyou no zisshijyoukyou ni tuite. Available online: https://www.mext.go.jp/content/20200513-mxt_kouhou02-000006590_2.pdf (accessed on 27 February ).

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. Shingata Korona wirus kansenshou no eikyou niyoru rinnjikyugyouchousa no kekka ni tuite. Available online: https://www.mext.go.jp/content/20220204-mxt_kouhou01-000004520_5.pdf (accessed on 27 February).

- Racine, N.; McArthur, B.A.; Cooke, J.E.; Eirich, R.; Zhu, J.; Madigan, S. Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA pediatrics 2021, 175, 1142–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, E.C.; Haase, A.M.; E Foster, C.; Verplanken, B. A systematic review of studies probing longitudinal associations between anxiety and anorexia nervosa. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 276, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier, S.M.; Bulik, C.M.; Thornton, L.M.; Mattheisen, M.; Mortensen, P.B.; Petersen, L. Diagnosed Anxiety Disorders and the Risk of Subsequent Anorexia Nervosa: A Danish Population Register Study. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2015, 23, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgess, A.; DiBartolo, P.M. Anxiety and perfectionism: Relationships, mechanisms, and conditions. Perfectionism, health, and well-being 2016, 177–203. [Google Scholar]

- Bastiani, A.M.; Rao, R.; Weltzin, T.; Kaye, W.H. Perfectionism in anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders 1995, 17, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlenburg, S.C.; Gleaves, D.H.; Hutchinson, A.D. Anorexia nervosa and perfectionism: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2019, 52, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vacca, M.; De Maria, A.; Mallia, L.; Lombardo, C. Perfectionism and Eating Behavior in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 580943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haycraft, E.; Blissett, J. Eating disorder symptoms and parenting styles. Appetite 2009, 54, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jáuregui Lobera, I.; Bolaños Ríos, P.; Garrido Casals, O. Parenting styles and eating disorders. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 2011, 18, 728–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, C.S.; Overall, N.C.; Henderson, A.M.E.; Low, R.S.T.; Chang, V.T. Parents’ distress and poor parenting during a COVID-19 lockdown: The buffering effects of partner support and cooperative coparenting. Dev. Psychol. 2021, 57, 1623–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, W.E.; Dumas, T.M.; Forbes, L.M. Physically isolated but socially connected: Psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID-19 crisis. Can. J. Behav. Sci. / Rev. Can. des Sci. du Comport. 2020, 52, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YOUNGMINDS. Coronavirus: Impact on young people with mental health needs. Available online: https://www.youngminds.org.uk/media/04apxfrt/youngminds-coronavirus-report-summer-2020.pdf (accessed on 27 February).

- Qi, M.; Zhou, S.-J.; Guo, Z.-C.; Zhang, L.-G.; Min, H.-J.; Li, X.-M.; Chen, J.-X. The Effect of Social Support on Mental Health in Chinese Adolescents During the Outbreak of COVID-19. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merianos, A.; King, K.; Vidourek, R. Does Perceived Social Support Play a Role in Body Image Satisfaction among College Students? J. Behav. Heal. 2012, 1, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.; Russell-Mayhew, S.; Saraceni, R. Evaluating the Effects of a Peer-Support Model: Reducing Negative Body Esteem and Disordered Eating Attitudes and Behaviours in Grade Eight Girls. Eat. Disord. 2012, 20, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirsch, A.C.; Shapiro, J.B.; Conley, C.S.; Heinrichs, G. Explaining the pathway from familial and peer social support to disordered eating: Is body dissatisfaction the link for male and female adolescents? Eating Behaviors 2016, 22, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Omari, O.; Al Sabei, S.; Al Rawajfah, O.; Abu Sharour, L.; Al-Hashmi, I.; Al Qadire, M.; Khalaf, A. Prevalence and Predictors of Loneliness Among Youth During the Time of COVID-19: A Multinational Study. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2021, 29, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houghton, S.; Kyron, M.; Hunter, S.C.; Lawrence, D.; Hattie, J.; Carroll, A.; Zadow, C. Adolescents' longitudinal trajectories of mental health and loneliness: The impact of COVID-19 school closures. J. Adolesc. 2022, 94, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, M.P. Loneliness and Eating Disorders. J. Psychol. 2012, 146, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, K.; Hards, E.; Moltrecht, B.; Reynolds, S.; Shum, A.; McElroy, E.; Loades, M. Loneliness, social relationships, and mental health in adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 289, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, M.; Reilly, E.E.; Siegel, J.A.; Coniglio, K.; Sadeh-Sharvit, S.; Pisetsky, E.M.; Anderson, L.M. Eating disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic and quarantine: an overview of risks and recommendations for treatment and early intervention. Eat. Disord. 2020, 30, 54–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Before-pandemic period Jan. 2017 - Feb. 2020 (38 months) |

After-pandemic period Mar. 2020 - Jan. 2022 (23 months) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of cases | No. of cases per month | No. of cases | No. of cases per month | |

| Total No. | 41 | 1.08 | 34 | 1.48 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1 | 0.03 | 5 | 0.22 |

| Female | 40 | 1.05 | 29 | 1.26 |

| Age groups | ||||

| 7-14 | 28 | 0.74 | 26 | 1.13 |

| 15-19 | 13 | 0.34 | 8 | 0.35 |

| Department | ||||

| Pediatrics | 10 | 0.26 | 11 | 0.48 |

| Psychosomatic Medicine | 30 | 0.79 | 22 | 0.96 |

| Psychiatry | 1 | 0.03 | 1 | 0.04 |

| No. of inpatient beds in medical centers | ||||

| 100~299 | 29 | 0.76 | 24 | 1.04 |

| 300~499 | 1 | 0.03 | 1 | 0.04 |

| 500≦ | 11 | 0.29 | 9 | 0.39 |

| Regions of medical centers | ||||

| Chuubu | 29 | 0.76 | 23 | 1.00 |

| Tohoku | 10 | 0.26 | 9 | 0.39 |

| Kinki | 1 | 0.03 | 1 | 0.04 |

| Kanto | 1 | 0.03 | 1 | 0.04 |

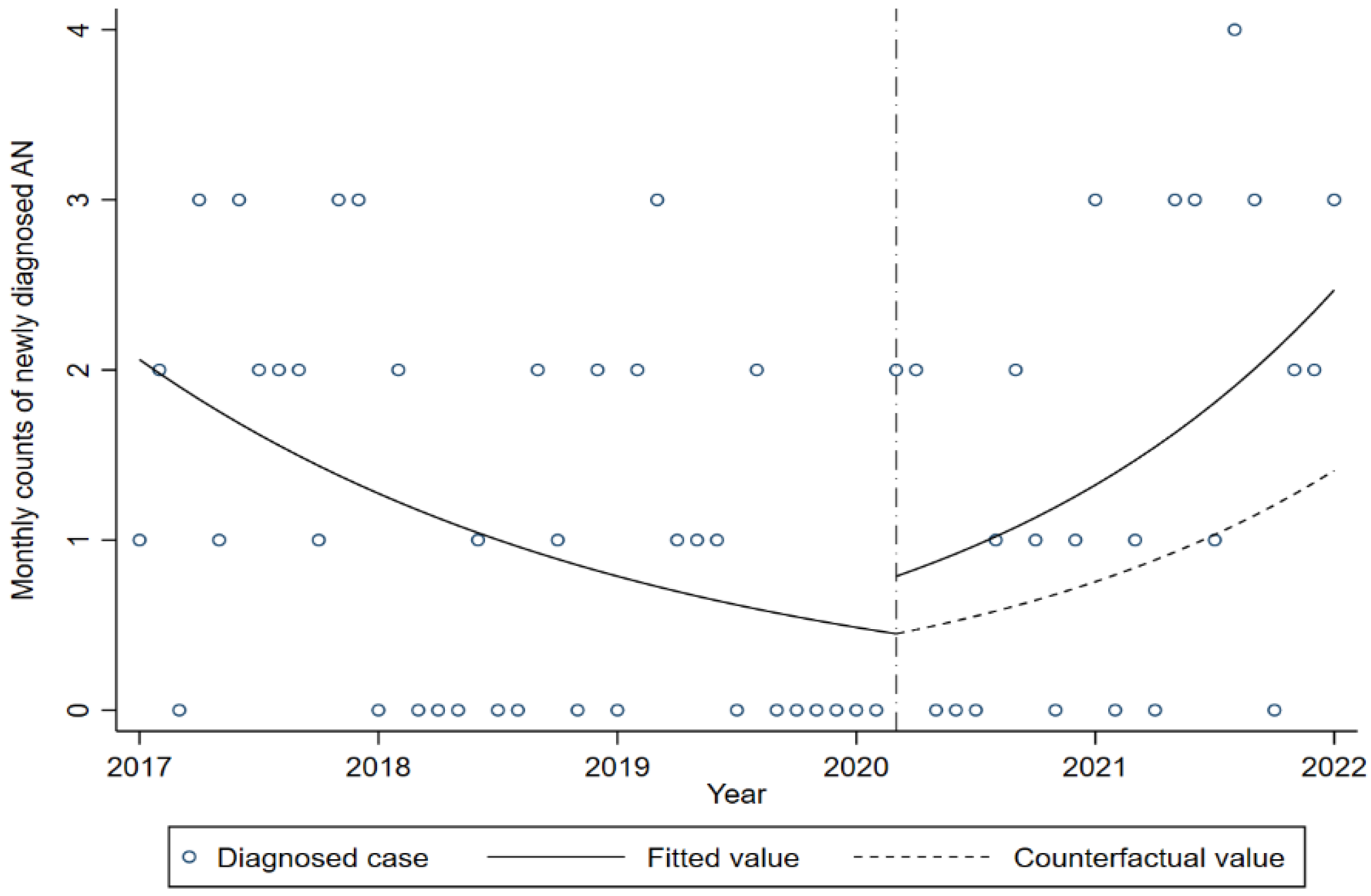

| Newly diagnosed case of AN aged 7-19 years | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence rate ratio | 95% Cofidence Interval | P-value | |

| Slope before the pandemic | 0.961 | 0.932 to 0.990 | 0.009 |

| Level-changes after the pandemic | 1.753 | 0.578 to 5.319 | 0.322 |

| Slope after the pandemic | 1.096 | 1.032 to 1.176 | 0.003 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).