1. Introduction

There is a need to highlight the role of women and their contributions to traditional crafts, especially given the growing interest in this field today. In many cultures, traditional crafts—be it weaving, embroidery, or pottery—have been part of the daily lives of women. These crafts were not only a source of beauty but also a means of survival, with women using their skills to support their families and maintain cultural traditions. But the irony is striking: the more essential women’s labor was, the more it was taken for granted.

Textile crafts, for example, weaving and spinning were once lifelines for households, requiring extraordinary technical knowledge and creative problem-solving. Women wove cloth not just to clothe their families but also to express identity, tell stories, and participate in cultural rituals. Yet, their intricate labor has often been classifies as “women’s work,” rather than recognized as a combination of artistry, engineering, and cultural preservation.

Textile industry offers a vivid example of how women’s roles in traditional crafts have been marginalized. From dyeing and spinning to weaving and embroidery, women have historically carried these traditions on their shoulders. The exclusion of women’s labor from formal historical and economic accounts perpetuates the undervaluation of their work, both culturally and economically.

In Najran, Saudi Arabia, for instance, women’s textile traditions are rich with history and meaning. The patterns and techniques they use are not merely aesthetic; they carry symbols of their communities, and a deep connection to the land. These women are not just artisans—they are guardians of heritage.

Women have long faced significant challenges in preserving the quality and increasing the production of traditional weaving while trying to balance the preservation of its authenticity with the need for innovation. Traditional weaving holds immense cultural significance, yet the weaving traditions in the Najran region have not been given the academic attention they deserve. There is a noticeable gap in research on the tools, production methods, materials, and decorations that define the craft in this region.

When it comes to preserving cultural heritage, various important studies have paved the way for understanding these practices across the Arab world. One of the most influential works is by Al-Muntasheri (2012), who examined carpet weaving in Oman. His study sheds light on how women in regions such as Dhofar and Bahla have kept these intricate traditions alive despite the pressures of modernization. Al-Muntasheri's research highlights that women have not only maintained the technical aspects of weaving but also contributed significantly to the growing economic role of the craft, both locally and internationally. His insights have been crucial in shaping our understanding of how women in Najran have adapted traditional weaving techniques while facing similar socio-economic challenges.

Similarly, Al-Zaydi (2010) focused on embroidery traditions in Yemen, particularly in Sana’a and Taiz, exploring how women used these crafts to express both their cultural and religious identities. His study emphasizes the intergenerational transmission of these skills within families, providing a deeper understanding of how such traditions have endured. Al-Zaydi also pointed out how women’s roles in textile production were often intertwined with household duties and community life, yet their contributions were frequently undervalued and overlooked.

Ben Dawoud’s (2014) research on textile production in Algeria’s Kabylie and Tizi Ouzou regions was also particularly enlightening for our study. His work illustrates how women, using local resources like natural dyes and hand-spun wool, have not only preserved cultural practices but also empowered themselves economically. Women’s craftsmanship has been integral to rural economies, providing a means of financial independence within traditional societies.

Lastly, Al-Khatib (2011) offered a compelling study of Coptic textiles in Upper Egypt, showing how women have managed to preserve and adapt these textiles to meet both local and international market demands. His research reveals that women’s involvement in textile preservation has gone beyond technical skill, representing a deep connection to religious and historical narratives that shape cultural identity.

Taken together, these studies have laid a strong foundation for understanding the vital role women across the Arab world have played in safeguarding cultural heritage through traditional crafts. Our research draws on these insights, aiming to deepen and expand the discussion on women’s contributions to both the cultural and economic legacy of regions like Najran. By addressing the gaps these studies have only partially explored, our work aims to offer a more comprehensive view of this important tradition.

The objectives of this study are to:

Explore the historical significance of traditional weaving in Najran, focusing on its roots in the Arabian Peninsula.

Investigate the tools and raw materials used in traditional weaving in Najran, and examine the role of women in developing and refining these techniques.

Identify the factors that have played a part in the preservation and continuity of traditional weaving in Najran.

4. Discussion

The civilization of nations and peoples is measured by the heritage and history they possess, as well as the ability of their citizens to preserve and modernize this legacy. The heritage of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is remarkably diverse due to its vastness, rich culture, and deep-rooted civilization. Each region of the Kingdom boasts its unique character and traditions, with a special emphasis on the craft of weaving, particularly in the Najran region. This craft holds a significant role in preserving customs, traditions, and cultural identity. Traditional weaving, in essence, is more than just a craft; it is a form of artistic expression and folklore that reflects the thoughts and culture of the people.

The Najran region is located in the southwestern part of Saudi Arabia, at approximately longitude 44°, which places it on the eastern edge of the Arabian Shield, extending to the southernmost part of the Arabian Peninsula, and latitude 17°. The region covers an area of about 13,500 square kilometers, with a large portion of it consisting of desert. The land of Najran is mostly flat, with the Najran Valley running through the center, crossing the region from west to east (Al-Maraih, 1992, p. 13). Historically, the people of Najran were divided into two main groups: the Bedouins and the settled population (Al-Hadar). Each group led a distinct way of life, yet they were connected by ties of kinship, shared economic interests, and the strong bond of religion. The Bedouins, like their counterparts across the Arabian Peninsula, followed pastures and rainwater gathering areas with their herds of camels and sheep. In contrast, the settled population primarily engaged in agriculture as their main occupation (Al-Maraih, 1992, p. 15).

The Najran region has long been distinguished by its artisanal crafts, with a high number of skilled craftsmen who have possessed a keen artistic sense since ancient times (Al-Maraih, 1992, p. 95). The area's large population, fertile land, and sense of stability contributed to the flourishing of various industries. Among the most notable villages in the Najran Valley are Al-Muwafjah, Salwah, Zur Al-Harith, and Baran (1957, Vol. 11). Despite the fact that the Hijaz region during the pre-Islamic era was surrounded by religious, intellectual, and material influences that shaped its culture, the people of Najran specialized in textile production. They were even responsible for transporting textiles to Mecca to cover the Kaaba, a significant honor that underscored the reputation and quality of Najran’s textile industry (1964, Vol. 1).

Historical sources confirm that Najran, before the advent of Islam, was known for producing luxurious types of textiles, specifically made for the use of kings, or as gifts to princes, nobles, and religious figures. Kings, priests, and the wealthy would wear finely crafted fabrics, some made from pure silk or blended with other materials. Notably, some of these fabrics were embroidered with gold (1993, Vol. 7).

After the people of Najran embraced Islam, textile production continued much as it had before. A clear indication of this is the attire worn by the delegation from Najran when they visited the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him); they were draped in al-burud known as al-hibar, which were ornate striped cloaks considered among the most valuable garments of the 1st and 2nd centuries AH (7th-8th centuries AD) (1993, Vol. 7).

Further evidence of the flourishing textile industry in Najran during the time of the Prophet (peace be upon him) is found in the large quantities of textiles they produced. When the people of Najran converted to Islam, they offered the Prophet two thousand garments (new robes), which became part of their agreement with him. The text of this agreement reads

"بسم الله الرحمن الرحيم، هذا ما كتب محمد النبي رسول الله لأهل نجران، إذ كان له عليهم حكمه في كل ثمرة وفى كلّ صفراء(ذهب) وبيضاء(فضة) وسوداء ورقيق (جارية وعبد)، فأفضل ذلك عليهم (أي أبقاه لهم)، وترك ذلك كلّه لهم، على ألفي حلّة (ثوب جديد) من حلل الأواقي (تباع وتشترى بالأوقية)، في كل رجب (شهر رجب) ألف حلّة، وفى كل صفر (شهر صفر) ألف حلّة، كل حلّة أوقيّة (أي ثمن كل حلة أوقية) من الفضة....".(Safwat, n.d., Vol. 1, p. 76)

Translation: “In the name of Allah, the Most Merciful, the Most Compassionate. This is what Muhammad, the Prophet and Messenger of Allah, wrote for the people of Najran, as he had authority over them in all fruits, gold, silver, black (e.g., livestock), and servants (both male and female). He left all this to them, except for two thousand robes of al-awaqi (a type of fabric sold by weight), to be delivered: one thousand robes in Rajab (the month of Rajab) and one thousand robes in Safar (the month of Safar), with each robe valued at an uqiya (a silver weight)”.

It is also well-documented that the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) was shrouded in three Najrani garments after his death. As narrated by Ibn Abbas (may Allah be pleased with him): “The Messenger of Allah was shrouded in three Najrani garments: two robes and the shirt in which he passed away” (Ibn Majah, 1471) (2006, Vol. 10).

Based on the above, we can conclude that Najran had long been renowned for producing high-quality textiles, specifically crafted to meet the needs of the social elite in Najran. The abundance of production also reflects the level of craftsmanship in the region. Additionally, it is evident that the craft of weaving in Najran dates back to the pre-Islamic era.

4.1. Traditional Textile Production in Najran:

Textile refers to raw materials that have been transformed through a series of manual processes into threads, derived from natural fibers. These fibers may be of plant origin, such as cotton, flax, and others, or of animal origin, like wool, hair, and fur. Additionally, some insects produce fibers, such as natural silk, which comes from the silkworm. The term "textile raw materials" refers to the natural fibers that humans can convert into threads through spinning.

The processes of weaving, spinning, dyeing, and sewing are closely interconnected and also depend on the availability of both animal and plant resources. To understand the stages of traditional textile production, one must first become familiar with the key raw materials and the essential tools used in the production process.

Wool is the dense hair that covers the bodies of certain breeds of sheep, known locally as al-shiyah or al-na’jah, and referred to by Arabs as al-dhan. High-quality wool is characterized by its long, smooth fibers, while lower-quality varieties tend to be coarse and tangled. Coarse wool is typically used for weaving clothing and tents. The most beautiful natural colors of wool are black, white, and brown. Wool is one of the most important raw materials used in textile production and has been widely utilized in the Arabian Peninsula due to the abundance of sheep, with notable breeds raised in the Kingdom (Encyclopedia of Traditional Culture in Saudi Arabia, 2000, p. 415).

The weaving process begins with shearing the wool. In the past, household women would perform this task without adhering to a specific schedule. When they noticed that a sheep or lamb had grown long wool, they would ask the shepherd to hold it. They would use a blade to cut the wool in a somewhat haphazard manner. After losing about a third of the wool from the sheep, they would release it to return to the flock. Meanwhile, the fine wool would often remain stuck around the necks and hindquarters of the camels until it fell off naturally. Only at this stage could the household women gather the wool suitable for carding, using their thumb and index finger. Women would mix goat hair, sheep wool, and camel hair in preparation for spinning. They would sort the brown hair for camel and the white wool for sheep. Additionally, women would weave white belts on the floors of tents made from black wool, using white wool to adorn the edges of the black wool (Nawar, 2018, p. 272; 2009, Vol. 1).

In addition to wool, cotton, muslin, and linen were used, although these materials were mostly imported. Their threads were utilized to produce caps and various lightweight textiles. Silk was also imported from Syria and India in the form of spun and dyed threads known as ibrisim, from which luxurious women's textiles were woven (1993, Vol. 7).

From the above, we conclude that the textile industry in Najran relied on agricultural and animal production for its raw materials, which greatly contributed to the vitality of this activity in the region. Historically, women would shear the wool themselves, although this practice changed over time, with shearing typically occurring in the summer.

Traditional textile production in the Najran region goes through several stages, aimed at preparing raw materials and converting them into clean, impurity-free, uniform threads, resulting in high-quality, durable textiles with an appealing appearance. The preparation stages begin with thoroughly washing the wool and camel hair (known as ‘uq) using water and soap. In the past, a soap-like substance called al-shanan was used for cleaning. During this process, the wool and hair would be rubbed by hand and struck with a thick stick. After washing, the wool and hair are dried and then carded. Carding employs a special tool called al-bishtakah, which is a rectangular piece of wood with rows of pointed nails. During carding, the bishtakah is pulled through the wool and hair, helping to separate any adhering materials, making them ready for spinning (Encyclopedia of Traditional Culture in Saudi Arabia, 2000, pp. 398-399).

Thus, women would prepare the wool, transforming it from shearing to fine threads before commencing the spinning process using a spindle (Pl.1). The spindle’s function is to convert wool or camel hair into threads and is a hand-operated tool made from wooden sticks. During spinning, women would sit in a squatting position, placing the fibers in their left hand and wrapping them around their palm or a reed. The spindle would be held in the right hand, and the spinning process involves joining the fibers using a previously spun thread, known as al-ta’mah, to facilitate this operation. The left hand is raised to shoulder level while the spindle is held below with the thumb and index finger of the right hand. The thread is twisted from left to right as the left hand is lifted, and then wrapped around the spindle. This process is repeated following the same steps to obtain the desired quantity of threads, which are then wound together and collected (Al-Maliki, 2020, pp. 301-302).

Pl.1: The Spindle (Photographed by the Researchers, 2024)

The dyeing of spinning threads takes place before weaving, and it is the women who carry out this task themselves. The coloring and dyeing of threads represent a crucial stage in the textile industry, relying on extracting colors from plants available in the Najran region. This is achieved through the use of their peels, leaves, and roots to obtain these dyes, with women employing inherited methods for extraction (Al-Shammari, 2023, pp. 590-595). It is noteworthy that women used color fixatives during the dyeing process. They would dissolve these fixatives in water to allow the spun threads to absorb the dye solutions, aimed at stabilizing the colors and protecting them from the effects of air, sun, and rain. Among the fixatives used were coarse salt, black lemon, and alum. The more a weaver desired to enhance the color's intensity, the more they would repeat the process in the same dye solution (Tairah, 2010, pp. 1950-1951).

After the processes of spinning and dyeing, the meticulously twisted threads become ready for making garments and other textiles using a loom. The loom consists of a set of prepared sticks made from tree branches, smoothed and shaped according to specific measurements depending on the purpose of each stick. Women use goat hair to create tent covers, storage bags, or special saddlebags for camels. Arab women utilize a very simple loom, known as "the noto," which consists of two short sticks inserted into the ground at a specific distance determined by the width of the piece to be woven. A third stick is placed above these two sticks at a distance of about four yards, and three more sticks are arranged in the same manner. The weft is laid over the two intersecting horizontal sticks, and to maintain an accurate distance between the wefts, a flat stick called "the mensabah" is placed between them. Women use a wooden piece as a shuttle, while a short deer horn is employed to press the thread backward (Nawar, 2018, p. 273; 2007, vol. 1).

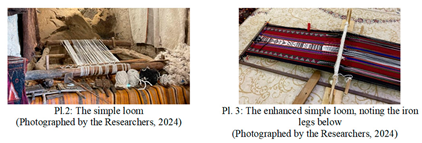

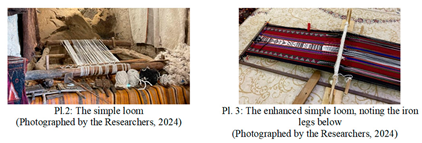

Historical sources indicate that the tools of production were made by the women themselves (Al-Maliki, 2020, pp. 301-302). It is not far-fetched to assume that the women of Najran made improvements to the tools they crafted. Upon examining the simple loom (Pl.2), it is evident that it has evolved; some looms have added iron or wooden legs, and there are slight variations among looms depending on the weaver's preferences and comfort. Inquiring whether the weavers made modifications to the looms based on their desires and production nature, based on discussions with Al-Qaḥṭānī, Dalīl, Professor at King Saud University, Saudi Arabia and an expert in archaeology and heritage studies, she stated: "This improved loom—referring to the enhanced simple loom (Pl.3) —has led the weavers to approach the blacksmith and enhance the looms with iron, and there are wooden improvements. "Although historical sources do not provide direct evidence for this, the clear demand, fame, and abundance of products woven by women in Najran serve as proof of their skill with the craft and tools. These improvements significantly enhanced the efficiency of the weavers and distinguished their output.

The next stage in textile production is the sewing process. In the Arabian Peninsula, including Najran region, garment sewing was a common craft primarily performed by women. Through this craft, they produced garments and turbans from previously woven fabrics, tailored to specific measurements. Women employed sewing needles in two distinct methods: the first, known as “Shamj,” involves spacing the stitches apart, while the second, referred to as “Shamrij,” involves closely spaced stitches, typically used for lighter fabrics. The thread used for sewing was commonly referred to as “silk” or “silka” by the Arabs (Amer, 2005, p. 103).

From the above, we conclude that weaving is a craft of innovation and production. It reflects the effort expended by the weaver in transforming raw materials like wool, hair, or fur into spun threads that meet their needs, traditions, and customs. The weaver utilizes simple tools and their own dexterity to create stunning product designs. This craft requires immense patience, precision, and the considerable time invested in producing fabrics manually. Consequently, these handcrafted products continue to be highly valued for their quality and unique designs.

Traditional and artisanal crafts are integral components of local creative industries that reflect the interaction between people and their local environment. These crafts serve as a vital means to create job opportunities, improve income, and elevate living standards, contributing to the reduction of poverty and fostering sustainable growth. Women’s crafts, in which women utilize their manual skills to produce useful or decorative items that embody the culture and nature of their region, are a fundamental aspect of these traditional crafts. Women have the freedom to express their unique tastes without being confined to rigid standards (Al-Zaid, 2023, p. 197).

The work of women in producing traditional textiles in Najran is characterized by several features that have contributed to the preservation of this heritage. Among the most notable are economic development and social dimension, and the preservation of cultural identity.

4.2. Economic Development and Social Dimension

The traditional crafts and industries sector is crucial in diversifying national income sources and providing job opportunities through relatively simple investments compared to other economic activities (Al-Zaid, 2023, p. 197). Regarding women's involvement in producing traditional textiles in Najran, references indicate that, "... women would keep their wool, spin it, and sometimes sell these threads among themselves" (2009, vol. 1). Additionally, housewives sold their wool used in making coarse woolen carpets and blankets along the borders (Nawar, 2018, p. 272).

Based on the above, we can deduce that women in Najran played a significant role in the region's economic life through their extensive expertise in textile production and their involvement in both producing and marketing their goods. Women exchanged threads among themselves, and at times purchased them from neighbors or friends to complete weaving projects or facilitate the production of textiles, reflecting a spirit of collaboration within the community. Their efforts were not confined to local markets; they extended to selling wool used in carpets and rugs in markets beyond Najran, although there is no evidence to suggest that husbands or children assisted them in transporting or selling these products. Their craftsmanship gained recognition in both local and neighboring markets, contributing to the economic vitality of the region. The abundance of raw materials, especially wool, combined with the high volume of thread production, made sales easier, and it is plausible that some women specialized in spinning and selling threads without engaging in further stages of production. Through these efforts, women in Najran not only created job opportunities for themselves but also demonstrated their entrepreneurial abilities by independently marketing their products.

Most likely, some women would keep wool, spin it, and sell threads among themselves or use them to create carpets and rugs, even selling these products outside Najran. Through these activities, women significantly contributed to strengthening the economy of Najran by producing and selling textile products and threads, creating job opportunities for themselves. Furthermore, women played an active role in marketing their products independently, reflecting their significant involvement in economic development and stability. Consequently, this involvement helps preserve traditional textile heritage and ensures the continuous realization of its economic benefits.

The social dimension in handicraft industries encompasses the utilization of all human resources, emphasizing the artisan's ability to perform such tasks within their environment. It also empowers the elderly, individuals with disabilities, and others to participate in the productive process, thereby increasing sources of income (2023, p. 197).

Historically, wool spinning has been predominantly associated with women rather than men (Karami, 1427 AH, p. 53). This is supported by a narration from Ibn Asakir, citing Ziyad Abu al-Sakan, who stated: "I entered upon Umm Salama, and she had a spindle in her hand. I said, 'Every time I come to you, I find a spindle in your hands.' She replied, 'It drives away the devil and dispels idle thoughts. It has reached me that the Messenger of Allah, peace be upon him, said: 'The most rewarded among you are those who have the longest spindles. It is meant those that are used in conjunction with others to produce yarn or weaving thread. Al-Khatib, in his history, reported that Ibn Abbas said: The Messenger of Allah, peace be upon him, said: 'Adorn the gatherings of your women with spindles' (1995, vol. 70).

Historical sources describe women spinning cotton in the Arabian Peninsula through a beautiful scene: "... cotton spinning was one of the main women's crafts, and during the winter, one can see them leaving the orchards after breakfast, carrying their spindles to enjoy the sunlight" (2009, vol. 1). A simple spinning wheel was often placed in front of the women’s tent section, where mothers and daughters would work together on it, known as the "wool spindle" (Nawar, 2018, p. 273; 2007, vol. 1).

We can infer the shape and design of the wool spindle from an illustration in a manuscript of Maqamat AlHariri attributed to Baghdad, dated 634 AH/1237 AD, and preserved in the National Library in Paris (2016, p. 17). This illustration depicts an Arab woman sitting in an eastern posture, facing a spinning wheel "عجلة الغزل" used to produce threads of yarn in the form of bobbins for weaving. This illustration is considered one of the most important and earliest clear depictions of a wool spindle.

Women in Najran engaged in spinning as a form of leisure and a way to utilize their free time, often never sitting idly without their spinning tools in hand. In addition to spinning, women were responsible for sewing new garments and mending torn ones. While sewing was not their only task, most women, particularly those unable to visit male tailors for their or their family's clothing needs, excelled in this craft. Even wealthy women participated in spinning, often alongside their maids and servants. For instance, "Samra, the wife of Abdul Muttalib" (the mother of Al-Harith bin Abdul Muttalib: Samra bint Jundab bin Hujayr bin Riab bin Habib bin Suwa’ah bin Amir bin Sa’sa’a bin Muawiya bin Bakr bin Hawazin) had three maids who assisted her, singing and spinning with her. The crafts of spinning and weaving served as both entertainment and a way for women to fill their leisure time (Amer, 2005, p. 210).

In Najran, mothers were keen to prepare their daughters for the roles of homemakers by teaching them the skills of spinning and weaving (2012, p. 291). Elderly women also participated in spinning the threads that were prepared as raw materials for weaving and tailoring.

From this, we can deduce that the processes of spinning and weaving were predominantly practiced at home using traditional tools, such as the primitive loom. Women in Najran often collaborated to complete textile tasks, and this craft involved participants of all ages and backgrounds. Thus, spinning and weaving in Najran was not merely a craft but also a reflection of the creative identity of women, illustrating the influence of geography and history on the development of this craft through innovation and collective learning.

This observation can be supported by the Innovation Ecosystem Theory, which relates to Collective Learning Theory, highlighting how small enterprises enhance their innovative capacity through a shared local environment that facilitates teamwork. This theory is based on the premise that increased social interaction and density lead to more significant collaborative efforts (Hassan, 2020, p. 67). Such principles align with the practices of women in traditional textile production in Najran.

Therefore, it can be asserted that women in Najran, through their mastery of traditional textile production, exemplified Collective Learning Theory. This was evident in the social dimension described in various Arabic sources regarding the methods employed by weavers in Najran, which contributed to the establishment of local markets and the formation of productive communities, thereby enriching human capital.

4.3. Women and Preservation of Cultural Identity: Examples from the Arab Region

Cultural identity encompasses a combination of religious, linguistic, ethical, cultural, ethnic, and historical characteristics, alongside customs, traditions, and behaviors that define individuals and communities. This identity creates a sense of uniqueness, distinguishing nations from one another while forming the foundation of their culture, religion, and civilization (Atiyah, 2010, p. 55). Women have historically played a central role in preserving this identity through traditional crafts, ensuring the transmission of skills and cultural knowledge across generations.

The role of women in preserving traditional crafts is not unique to Najran. Across the Arab world, women have sustained a variety of weaving traditions, each shaped by local resources, cultural influences, and socio-economic factors.

In Oman, women in regions like Dhofar and Bahla are renowned for their carpet weaving. These handwoven carpets are created using complex techniques that have been passed down through generations. Traditionally, these carpets were crafted for household use, but they have also become a significant economic activity, contributing to local and international trade (Al-Muntasheri, 2012, pp.45-60). The vibrant carpets, often sold in markets such as Muscat's Souq, remain a symbol of cultural pride and economic empowerment.

In Yemen, women in mountainous regions like Sana’a and Taiz are renowned for their expertise in creating embroidered garments. These garments, adorned with intricate patterns, are deeply rooted in Yemen’s cultural and religious identity. The techniques used in embroidery are often taught within families, ensuring their preservation across generations. Despite the economic significance of these textiles (Al-Zaydi, 2010, pp.77-92). Today, these garments are celebrated as symbols of Yemeni heritage and are sought after in both local and international markets.

In Algeria, particularly in the Kabylie and Tizi Ouzou regions, women have long been involved in weaving traditional textiles. Using natural dyes and hand-spun wool, they produce thick blankets, curtains, and decorative pieces that are sold in local markets and used to adorn homes. The production of these textiles remains a vital source of income for many rural families, illustrating how traditional crafts can serve as both a cultural and economic cornerstone (Ben Dawoud, 2014, pp.103-118).

In Upper Egypt, women have preserved the production of handwoven Coptic textiles, which are often adorned with religious and historical symbols. Historically used as curtains or window covers, these textiles reflect a blend of cultural and artistic heritage. Women in rural areas continue to produce these embroidered fabrics, which are now sold in local and international markets, providing economic opportunities while preserving Egypt’s rich textile tradition (Al-Khatib, 2011, pp. 210-225).

In Najran, Saudi Arabia, women have been the custodians of Sadu weaving, a traditional craft that not only reflects the simplicity and purity of the desert environment but also serves as a vital part of the region's cultural identity. Sadu, a horizontal weaving method, is practiced using a ground loom to produce tightly woven, durable fabrics. The geometric patterns and vibrant colors—such as red and orange—used in Sadu designs draw inspiration from the desert surroundings, creating an artistic dialogue between the craft and the natural environment. Women in Najran have passed down these weaving skills through generations, ensuring that their cultural legacy endures despite modern challenges (UNESCO, 2024).

Women’s involvement in Sadu weaving is a testament to their creativity and resilience. Elderly Bedouin women, revered for their expertise, often train younger women within the family, reinforcing a cultural bond between generations. While historical sources lack precise details on the production capacity of early weavers, their dedication to quality and intricate design demonstrates the profound connection between their craft and their cultural identity (Amer, 2005, p. 210).

These comparative examples highlight women’s contributions to traditional textile across the Arab world. Women have served as guardians of heritage, passing down their skills and adapting their crafts to meet economic and social needs. While these contributions have often been marginalized in historical narratives, contemporary scholarship is increasingly recognizing their significance (Friedman, 1990, pp. 41-55).

This is evident through for example, the establishment of women’s associations in Oman and Yemen demonstrates how organized efforts can enhance the sustainability of traditional crafts. Similarly, Algeria and Egypt’s emphasis on using local resources for textile production shows how traditional practices can adapt to meet modern demands without losing their authenticity. Traditional weaving, such as Sadu in Saudi Arabia, is far more than a handicraft; it is an artistic expression of cultural identity and a vital contributor to economic and social life. The recognition of Sadu on UNESCO's Intangible Cultural Heritage list is a testament to its historical and cultural value. By examining the diverse weaving traditions across the Arab world, it becomes evident that women have played—and continue to play—a pivotal role in safeguarding cultural heritage. Supporting these efforts is essential to ensuring the continuity of these crafts as living traditions that enrich national identities and strengthen cultural bonds. These cases underscore the importance of creating supportive frameworks—both cultural and economic—that empower women to continue preserving these crafts.