1. Introduction

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a microvascular and neurodegenerative disease of the retina and is considered the most common and serious ocular complication of diabetes mellitus (DM) [

1]. DR is the leading cause of preventable blindness in working aged people (20 – 74 years old) in developed countries [

2]. Globally, 246 million of people are diagnosed with DM and the prevalence of DM is expected to reach 629 million by 2045 [

3]. Approximately one third of people with DM develop signs of DR and one third or these people have vision threatening complications [

4]. Moreover, 75% of patients with type 1 DM (T1DM) and 50% of patients with type 2 DM (T2DM) will develop DR sometime in their life [

5].

DR is classified based on the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) into non-proliferative DR (NPDR) with microaneurysms, hard exudates, cotton-wool spots, intraretinal heamorrhages, venous beadings and intraretinal microvascular abnormalities (IRMA) and proliferative DR (PDR) with external neovascularization and preretinal or vitreous heamorrhage [

6]. Diabetic Macular Edema (DME) refers to thickening of the macula and may occur in either NPDR or PDR and with PDR compose the common vision threatening complications of DR [

7].

Diabetic microangiopathy through hyperglycemia and chronic inflammation leads to capillary occlusion and thereby to retinal ischemia, elevated vascular permeability, leakage and neovascularization involving multiple biochemical signal pathways [

8]. There are many factors leading to DR, such as the duration of DM, glycemic control, hypertention, dyslipidemia, nephropathy, stroke, smoking, higher Body Mass Index (BMI), pregnancy, anemia and cataract surgery, however the exact pathogenesis remains still elusive [

9]. Despite the above risk factors, studies have revealed a substantial variation in the onset and progression of DR among different populations and the complex etiology of DR reflects the sundry treatments currently available, including anti-VEGF and glucocorticoid intravitreal medications, laser photocoagulation and vitrectomy [

10]. Although, the etiopathogenesis of DR has been studied thoroughly, the precise underlying mechanisms have not been clarified and genetic factors have shown to play a pivotal role in DR development and severity [

11].

UCHL3 (Ubiquitin Carboxyl-terminal hydrolase L3) belongs to deubiquitinating enzymes that are capable of removing ubiquitin (Ub) from protein substrates and generate free monomeric Ub, thus maintaining the dynamic balance of intracellular Ub levels [

12]. The conjunction of Ub and Ub-like proteins to intracellular proteins has emerged as a critical regulatory cellular process of paramount importance for numerous signaling pathways [

13].

UCHL3 gene is located on chromosome 13q22.2 and has been associated with oncogenesis, for instance with breast cancer and cervical carcinoma [

14]. Furthermore,

UCHL3 has deneddylating activity essential for various cellular functions and promotes insulin signaling and adipogenesis, hence contributing to retinal maintenance in stress conditions [

15]. One study has investigated the association between

UCHL3 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), such as rs4885322 (A>G), and risk of DR, but the results were inconclusive [

16].

HNMT (Histamine N-Methyltransferase) gene produces an enzyme that catalyzes the N-methylation of histamine, which is a major metabolic pathway of histamine, responsible for the termination of its neurotransmitter action [

17]. This gene is located in chromosome 2q22.1 and consists of 6 exons with approximately 34 kilobases length [

18]. The rs11558538 (C314T) SNP is located in exon 4 and is related to decreased enzyme activity and is associated with reduced risk of Parkinson’s disease [

19].

HNMT takes part in insulin signaling pathway, insulin activates insulin receptor (INSR) tyrosine kinase, which phosphorylates various proteins and activates different signaling pathways, while in the retina disrupted insulin receptor (INSR) signaling leads to cellular disfunction [

11].

Based on these observations, we decided to investigate the association between rs4885322 SNP of UCHL3 gene and rs11558538 SNP of HNMT gene with the risk of DR, which is the first in the literature to conduct such genotyping in Greek patients with DM.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

In our case–control study, we included 85 T2DM patients with DR and 71 T2DM patients without DR (NDR) matched by ethnicity and gender, who were recruited from the Department of Ophthalmology of the University General Hospital of Ioannina from January 2023 to June 2023. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of University General Hospital of Ioannina (Protocol Code: 17835 and Date of Approval: 20 July 2022). In addition, written informed consent was obtained by all the participants before entering the study and all samples were anonymized.

DM was defined according to the American Diabetes Association diagnostic criteria [

20]. Patients with T1DM were excluded from the study and there were no other exclusion criteria. Demographic and clinical data, including gender, age, onset and duration of DM, insulin or other antidiabetic medication used, BMI, smoking (packs/year), alcohol consumption, hemoglobin A1c levels (HbA1c), presence of hypertension, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease, stroke, anemia, pregnancy, nephropathy, cataract surgery and other medical or ophthalmological commodities. Hypertension was defined in all patients who had antihypertensive treatment or systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 140mmHg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 90mmHg. Dyslipidemia was determined if the patient had antilipemic agents or total cholesterol levels ≥ 200 mg/dl. Last but not least, nephropathy was identified when glomerular filtration rate (GFR) levels were < 60ml/min/1.73m

2, calculated with MDRD formula [

21].

All the patients, went through a complete ophthalmological examination, including the assessment of the best corrected visual acuity using the Standard Snellen Chart, slit lamp biomicroscopy, tonometry using Goldman applanation and fundoscopy after pupillary dilation. In cases where needed, fluorescein angiography was performed to confirm the diagnosis. Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) and OCT-Angiography (OCT-A) were performed in all patients to determine the presence of DME. DR was diagnosed based on the ETDRS diagnostic criteria.

2.2. Genotyping

Samples of peripheral blood (approximately 2ml) were collected from all patients. Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood samples using the NucleoSpin Blood Kit (MACHEREY-NAGEL GmbH & Co. KG, Düren, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality and concentration of purified DNA was estimated using the NanoDrop 8000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Regarding the rs11558538 polymorphism the genotyping was performed as described by Dai et al., (2013). Briefly, polymerase chain reaction – restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) was conducted to identify SNPs. The PCR system consisted of 5 μL of 2 X Master Mix (Kapa Biosystems, Wilmington, MA, USA), 10ng of genomic DNA, 0,2 μM of forward primer and 0,2 μM of reverse primer (Eurofins Genomics AT GmbH, Vienna, Austria). For rs11558538, PCR amplification was done with an initial denaturation step at 94

oC for 5 min, then 30 cycles of denaturation at 94

oC for 30 s, followed by annealing at 62

oC for 30 s, extension at 72

oC for 30 s and eventually elongation at 72

oC for 4 min. The PCR products were digested with

EcoR V at 37

oC for 1 h in 10μL of H buffer containing 2 μL of PCR product, 1 μL of 10X H buffer, 6.75 μL of double-distilled H

2O and 0.25 of restriction enzymes (TaKaRa Biotechnology, Shiga, Japan). The enzyme-digested products were isolated on 2% agarose gel and the fragments were visualized on UV light [

22]. Regarding the rs4885322 polymorphism genotyping was performed by allele specific PCR. The sequences of the primers were as follows: Common reverse: 5’ TTTCTAATACTTTCAATCCACA 3, Forward A allele: 5’ TATTGAGTTAGTGAGTAGAAAATAA 3’, and Forward G allele: 5’ TATTGAGTTAGTGAGTAGAAAATAG 3’.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The baseline characteristics of the study population were reported using descriptive statistics. Continuous variables were reported as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages.

A case-control analysis was conducted to investigate the association between genetic variants and diabetic DR. We used logistic regression models to assess the association of SNPs and DR, adjusting for sex and age. Results are reported as Odds ratios (ORs), along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

All SNPs were analyzed using three genetic models: (1) additive (risk increases per each additional risk allele, e.g., for rs4885322: AA =0, AG or GA = 1, GG = 2), (2) dominant (one or two copies of the risk allele have the same effect on the outcome, e.g., AG/GG vs. AA), and (3) recessive (both risk alleles are required to affect the outcome, e.g., GG vs. AG/AA).

The association between genetic variants and the type of DR (proliferative vs. non-proliferative) was examined among participants with DR. Logistic regression models were employed using similar genetic models (additive, dominant, recessive) as described above.

We further performed a sensitivity Analysis after excluding participants with extreme BMI values (<18.5 or >40 kg/m²) to assess the robustness of the results.

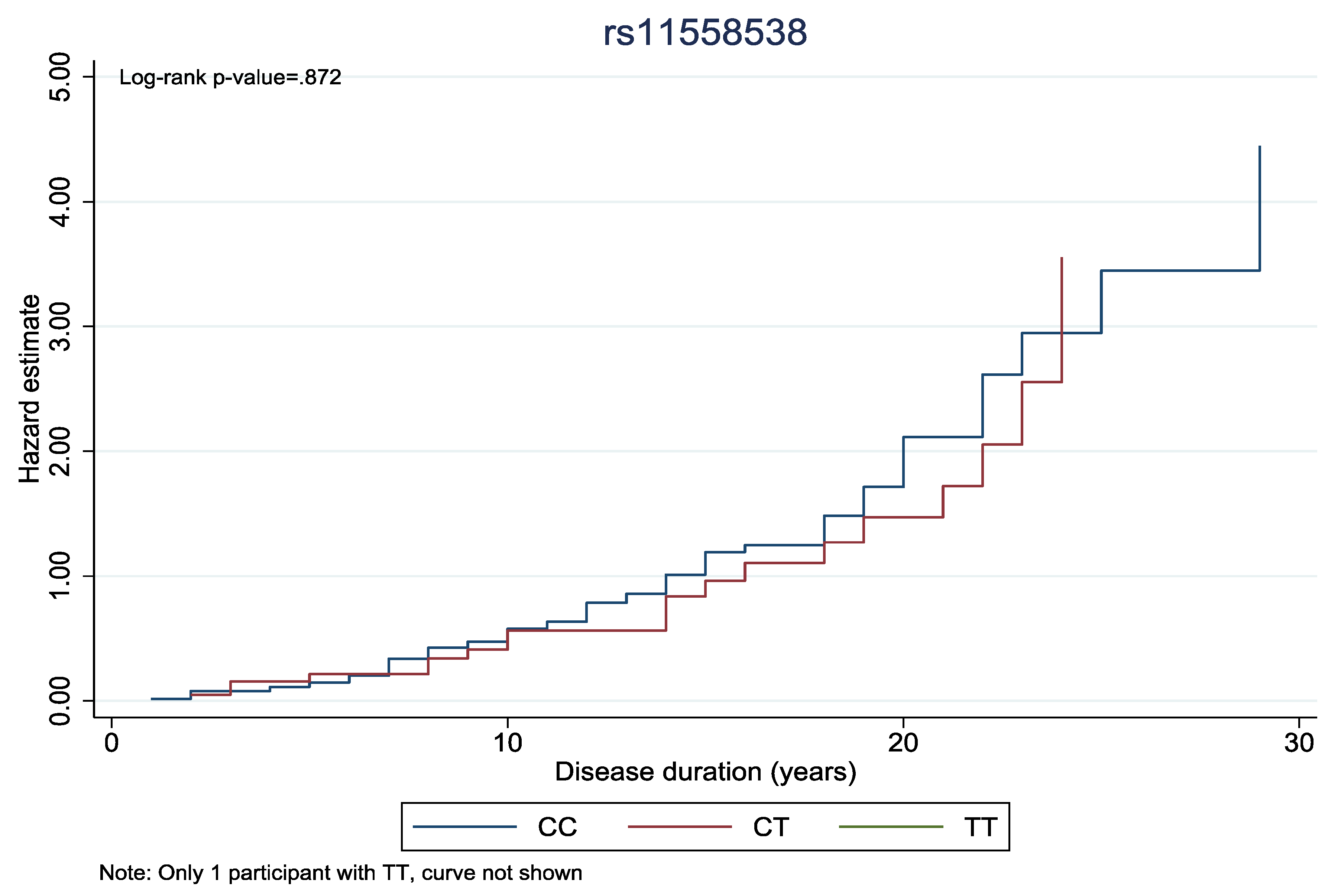

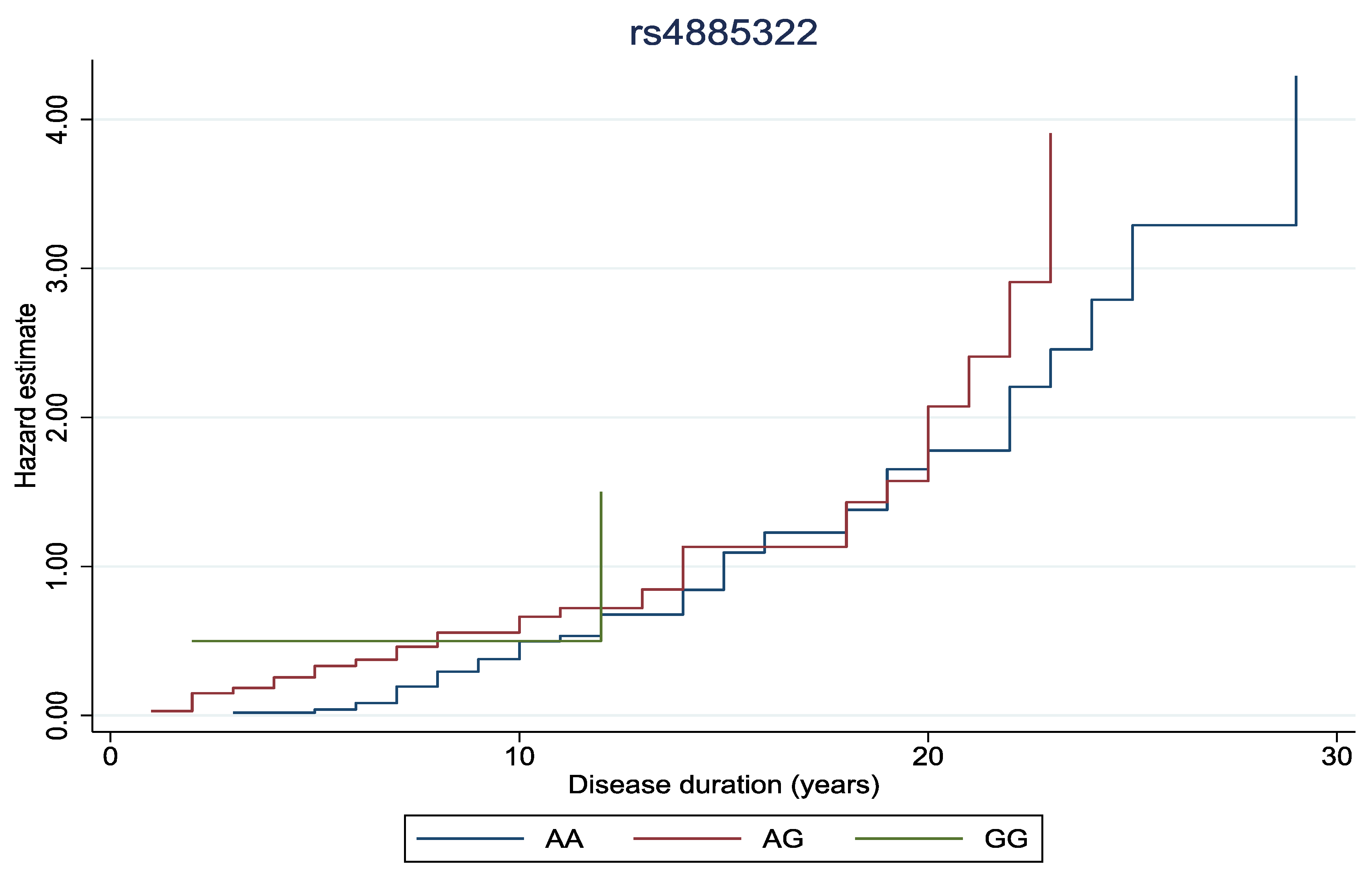

Finally, to explore the impact of genetic variants on the duration of diabetic retinopathy, cumulative hazard curves were generated. We performed log-rank tests to compare curves between genotypes.

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata v. 16.1. Results were considered statistically significant at a p-value < 0.05.

3. Results

The descriptive characteristics of the NDR and DR patients are presented in

Table 1. No significant differences were observed between the two groups in gender status, BMI, smoking, cataract surgery, presence of glaucoma, hypertension, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease, stroke, anemia, nephropathy, hypothyroidism and benign prostate hyperplasia (p-value ≥ 0.05). Although DR group showed a lower mean of age, patients presented significantly longer duration of DM and were more often under insulin therapy (p-value < 0.05). Additionally, patients with DR had elevated levels of HbA1c and almost 3 out of 4 patients (74,1%) of this group had NPDR.

The genotyping results are, also, introduced in

Table 1 and all of them were in the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Among our patients, the frequency of rs4885322 heterozygous genotype and the frequency of rs11558538 heterozygous genotype were elevated in the DR group in contrast with the NDR group. However, the presence of rs4885322 homozygous genotype and the presence of rs11558538 homozygous genotype in both groups were scarce.

In

Table 2 are demonstrated the genetic analyses of the rs4885322

UCHL3 gene SNP and of the rs11558538

HNMT gene SNP in the DR and the NDR groups based on sundry genetic models. First of all, concerning the rs4885322 SNP, the allelic effect increases the risk of DR by 2.04 times and the association is statistically significant (p-value = 0.04). Additionally, in the AG+GG vs AA model the risk of DR is elevated by 123% and the result is also statistically significant (p-value = 0.03). These associations remain statistically significant, when extreme BMI are excluded (p-value < 0.05).

The effect of the presence of the rs11558538 alleles on the development of DR is associated with 3.27 times increased risk and the result is statistically significant (p-value = 0.01). Moreover, the CT+TT vs CC model reveals an augmented risk of DR by 231%, while the allelic contrast highlights an elevated risk of DR by 205% and both these associations are statistically significant (p-value < 0.05). In fact, these correlations remain, also, statistically significant, when extreme BMI are excluded (p-value < 0.05).

Furthermore, the association of the rs4885322 and the rs11558538 SNPs with the development of PDR was examined in various genetic models (

Table 3). Nevertheless, no statistically significant associations were identified between the rs4885322 and the rs11558538 SNPs and the onset of PDR in any genetic model (p-value > 0.05).

In

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, the cumulative hazard estimate of DR in association with the duration of DM was investigated according to rs11558538 and rs4885322 SNPs, whereas no statistically significant associations were identified between the hazard estimate of DR and NDR according to the rs4885322 and the rs11558538 SNPs (p-value > 0.05).

4. Discussion

Although DR is the most common vascular disease of the retina and the most serious ocular complication of DM [

23,

24], the precise etiopathogenetic mechanisms have not been clarified and the currently available therapies are insufficient to prevent or minimize its complications [

25]. The main risk factors are DM duration, poor glycemic control, while several other risk factors have been identified, including the presence of hypertension, dyslipidemia, obesity, cardiovascular disease, stroke, nephropathy, smoking, pregnancy, anemia, and cataract surgery [

26]. The prevalence of DR varies significantly between different ethnicity groups, whereas there is an important variation in DR risk and the complexity of the disease may be explained by genetic factors, such as gene mutations and abnormal expression, which play a significant role in the onset and progression of DR [

27]. Genetic factors have been associated with the development of DR through various biological signaling pathways, such as insulin signaling, angiogenesis, neurogenesis, inflammation, adipogenesis and interaction of endothelial cells and leukocytes [

28,

29].

In our study, we aimed to investigate the association of the rs4885322 UCHL3 gene SNP and of the rs11558538 HNMT gene SNP with the onset of DR in a Greek population. We demonstrated that the rs4885322 SNP is correlated with the risk of developing DR and these findings are in accordance with a Chinese study, that presented similar findings, which although were not statistically significant. This is the first time in literature that this SNP is investigated in relation to DR in a Caucasian population and an enhanced risk of DR in T2DM patients is presented. Despite this association, the underlying molecular mechanisms remain elusive. It is suggested that the rs4885322 SNP affects the expression of UCHL3 gene and disrupt the balance of Ub level within the cell, and as a consequence insulin signaling is disarranged, leading to insulin resistance and hyperglycemia (Sharma et al., 2019).

In addition, the rs11558538 gene polymorphism is associated with the development of DR, increasing approximately 3 times the risk of DR in our findings. To our best of knowledge, this is, also, the first time in literature that this SNP is examined in accordance with DR in a Caucasian population and a positive association is observed. This SNP causes decreased activity of the expressed enzyme and an increase in histamine level, which may lead to abnormal INSR signaling and chronic hyperglycemia (Sharma et al., 2019). These results enhance the theory that genetic factors are involved in the etiopathogenesis of DR and elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

In spite of the results of our study, some limitations should be underlined. The relatively small size of the sample and the Caucasian origin limit the generalizability of our findings. Over and above that, the small number of patients with PDR was inadequate in order to shed light on a possible association of these two polymorphisms with the stage of DR. Despite these limitations, the current study elucidates the association between the rs4885322 UCHL3 gene SNP and the rs11558538 HNMT gene SNP and the risk of DR in Greek patients with T2DM.

5. Conclusions

To summarize, the role of the rs4885322 UCHL3 gene SNP and of the rs11558538 HNMT gene SNP was investigated in correlation with the risk of DR and both are associated with DR risk in Greek patients with T2DM. Considering the complexity of the disease and the interaction of genetic and environmental factors, further studies with larger samples and different ethnicities should be implemented to clarify the exact association of these SNPs and DR risk.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: K.F. and G.K.; methodology: G.M. and M.G.; software: V.L. and G.M.; validation: K.F., G.M., and G.K.; formal analysis: A.C.; investigation: K.F.; data curation: V.L. and M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, K.F.; writing—review and editing, K.F. and G.M.; supervision: M.M., M.G. and G.K.; project administration, M.G. and G.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of University General Hospital of Ioannina (Protocol Code: 17835 and Date of Approval: 20 July 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DR |

Diabetic Retinopathy |

| SNP |

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism |

| T2DM |

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus |

| NDR |

Non-Diabetic Retinopathy |

| HbA1c |

Hemoglobin A1c |

| DM |

Diabetes Mellitus |

| T1DM |

Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus |

| ETDRS |

Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study |

| NPDR |

Non-Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy |

| IRMA |

Intraretinal Microvascular Abnormalities |

| PDR |

Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy |

| DME |

Diabetic Macular Edema |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| SBP |

Systolic Blood Pressure |

| DBP |

Diastolic Blood Pressure |

| GFR |

Glomerular Filtration Rate |

| OCT |

Optical Coherence Tomography |

| OCT-A |

Optical Coherence Tomography – Angiography |

| IQR |

Interquartile Ranges |

| OR |

Odds Ratio |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| AMD |

Age-related Macular Degeneration |

| RR |

Risk Ratio |

| INSR |

Insulin Receptor |

References

- Ulbig, M. W.; Kollias, A. N. Diabetische Retinopathie: Frühzeitige Diagnostik Und Effiziente Therapie. Dtsch. Arztebl. 2010, 107, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, N.; Mitchell, P.; Wong, T. Y. Diabetic Retinopathy. The Lancet 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Cai, Y.; Jia, Z.; Shi, S. Risk Factors and Prevalence of Diabetic Retinopathy: A Protocol for Meta-Analysis. Med. (United States) 2020, 99, E22695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heng, L. Z.; Comyn, O.; Peto, T.; Tadros, C.; Ng, E.; Sivaprasad, S.; Hykin, P. G. Diabetic Retinopathy: Pathogenesis, Clinical Grading, Management and Future Developments. Diabet. Med. 2013, 30, 640–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leley, S. P.; Ciulla, T. A.; Bhatwadekar, A. D. Diabetic Retinopathy in the Aging Population: A Perspective of Pathogenesis and Treatment. Clin. Interv. Aging 2021, 16, 1367–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, T. H.; Patel, B.; Wilmot, E. G.; Amoaku, W. M. Diabetic Retinopathy for the Non-Ophthalmologist. Clin. Med. 2022, 22, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, X.; Zhong, H.; Fang, J.; Li, X.; Shi, R.; Yu, Q. Research Progress on the Pathogenesis of Diabetic Retinopathy. BMC Ophthalmol. 2023, 23, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simó-Servat, O.; Hernández, C.; Simó, R. Diabetic Retinopathy in the Context of Patients with Diabetes. Ophthalmic Res. 2019, 62, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.-Y.; Hsih, W.-H.; Lin, Y.-B.; Wen, C.-Y.; Chang, T.-J. Update in the Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Screening, and Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy. J. Diabetes Investig. 2021, 12, 1322–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, T.; Shi, Y.; Luo, S.; Weng, J.; Wu, Y.; Zheng, X. The Role of Inflammation in Immune System of Diabetic Retinopathy: Molecular Mechanisms, Pathogenetic Role and Therapeutic Implications. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Valle, M. L.; Beveridge, C.; Liu, Y.; Sharma, S. Unraveling the Role of Genetics in the Pathogenesis of Diabetic Retinopathy. Eye (Lond). 2019, 33, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Liu, H.; Tobar-Tosse, F.; Dakal, T. C.; Ludwig, M.; Holz, F. G.; Loeffler, K. U.; Wüllner, U.; Herwig-Carl, M. C. Ubiquitin Carboxyl-Terminal Hydrolases (Uchs): Potential Mediators for Cancer and Neurodegeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.; Fu, D.; Shen, X. Z. The Potential Role of Ubiquitin C-Terminal Hydrolases in Oncogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Rev. Cancer 2010, 1806, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.; Shen, X. Ubiquitin Carboxyl-Terminal Hydrolases: Involvement in Cancer Progression and Clinical Implications. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2017, 36, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.; Setsuie, R.; Wada, K. Ubiquitin Carboxyl-Terminal Hydrolase L3 Promotes Insulin Signaling and Adipogenesis. Endocrinology 2009, 150, 5230–5239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheu, W. H. H.; Kuo, J. Z.; Lee, I. Te; Hung, Y. J.; Lee, W. J.; Tsai, H. Y.; Wang, J. S.; Goodarzi, M. O.; Klein, R.; Klein, B. E. K.; Ipp, E.; Lin, S. Y.; Guo, X.; Hsieh, C. H.; Taylor, K. D.; Fu, C. P.; Rotter, J. I.; Chen, Y. D. I. Genome-Wide Association Study in a Chinese Population with Diabetic Retinopathy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013, 22, 3165–3173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, T.; Nakamura, T.; Yanai, K. Histamine N-Methyltransferase in the Brain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raftogianis, B. B.; Aksoy, S.; Weinshilboum, R. M. Human Histamine N-Methyltransferase Gene: Structural Characterization and Chromosomal Localization. J. Investig. Med. 1996, 44, 548–554. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Jiménez, F. J.; Alonso-Navarro, H.; García-Martín, E.; Agúndez, J. A. G. Thr105Ile (Rs11558538) Polymorphism in the Histamine N -Methyltransferase (HNMT) Gene and Risk for Parkinson Disease. Med. (United States) 2016, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Classification, I. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2014. Diabetes Care 2014, 37 (SUPPL.1), 14–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouliopoulos, N.; Siasos, G.; Bouratzis, N.; Oikonomou, E.; Kollia, C.; Konsola, T.; Oikonomou, D.; Rouvas, A.; Kassi, E.; Tousoulis, D.; Moschos, M. M. Polymorphism Analysis of ADIPOQ Gene in Greek Patients with Diabetic Retinopathy. Ophthalmic Genet. 2022, 43, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, C. And DBH Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms with Parkinson’ s Disease in a Northern Chinese Population. 2021, 1689–1695. [CrossRef]

- Dulull, N.; Kwa, F.; Osman, N.; Rai, U.; Shaikh, B.; Thrimawithana, T. R. Recent Advances in the Management of Diabetic Retinopathy. Drug Discov. Today 2019, 24, 1499–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gale, M. J.; Scruggs, B. A.; Flaxel, C. J. Diabetic Eye Disease: A Review of Screening and Management Recommendations. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2021, 49, 128–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torm, M. E. W.; Dorweiler, T. F.; Fickweiler, W.; Levine, S. R.; Fort, P. E.; Sun, J. K.; Gardner, T. W. Frontiers in Diabetic Retinal Disease. J. Diabetes Complications 2023, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H. G.; Shakoor, A. Diabetic and Retinal Vascular Eye Disease. Med. Clin. North Am. 2021, 105, 455–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W. J.; An, X. D.; Zhang, Y. H.; Zhao, X. F.; Sun, Y. T.; Yang, C. Q.; Kang, X. M.; Jiang, L. L.; Ji, H. Y.; Lian, F. M. The Ideal Treatment Timing for Diabetic Retinopathy: The Molecular Pathological Mechanisms Underlying Early-Stage Diabetic Retinopathy Are a Matter of Concern. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2023, 14, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, M.; Wickremasinghe, S.; Osborne, A.; Van Wijngaarden, P.; Martin, K. R. Diabetic Retinopathy: A Complex Pathophysiology Requiring Novel Therapeutic Strategies. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2018, 18, 1257–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, J. V.; Kuffova, L.; Delibegovic, M. The Role of Inflammation in Diabetic Retinopathy. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 10319–10329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).