Submitted:

09 January 2025

Posted:

10 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

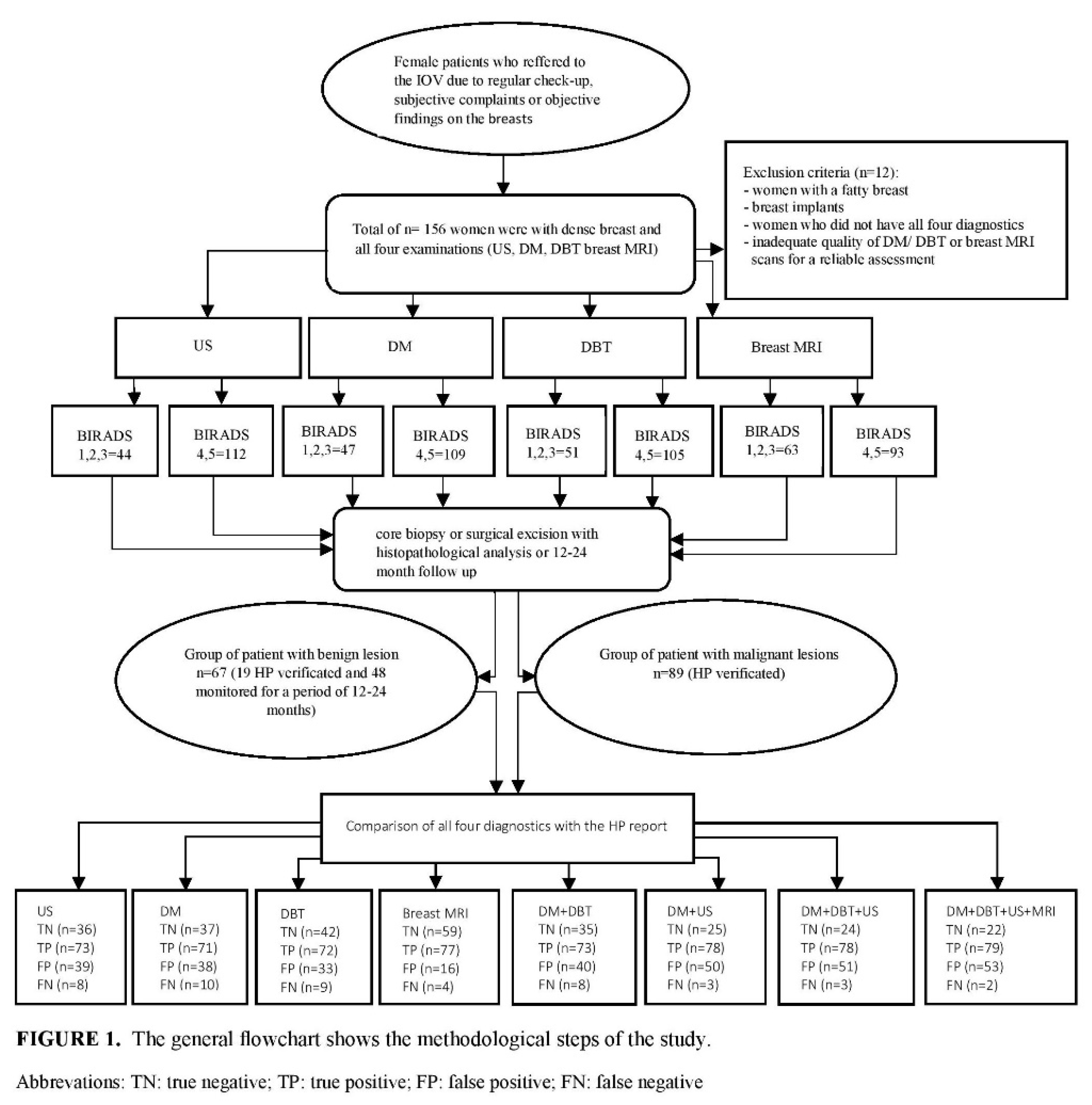

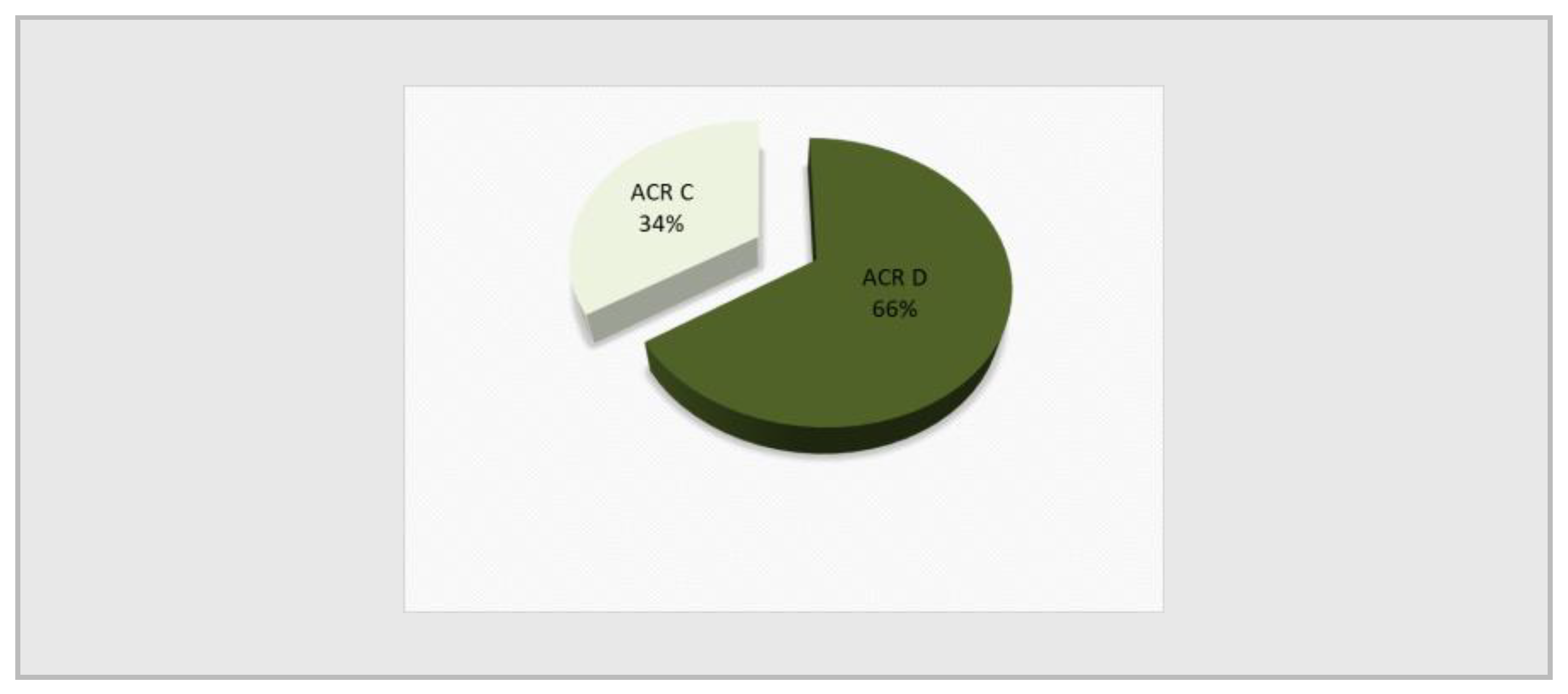

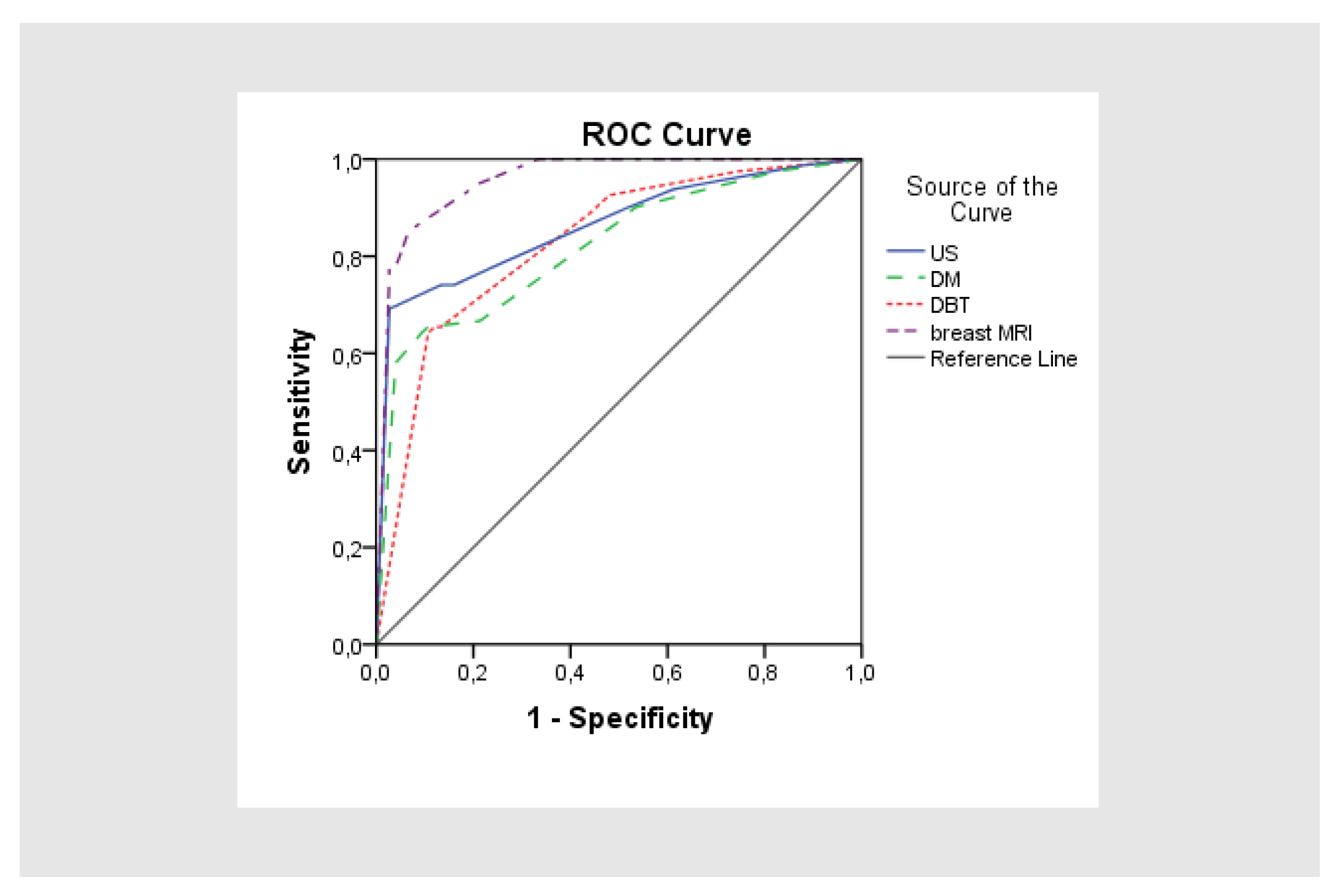

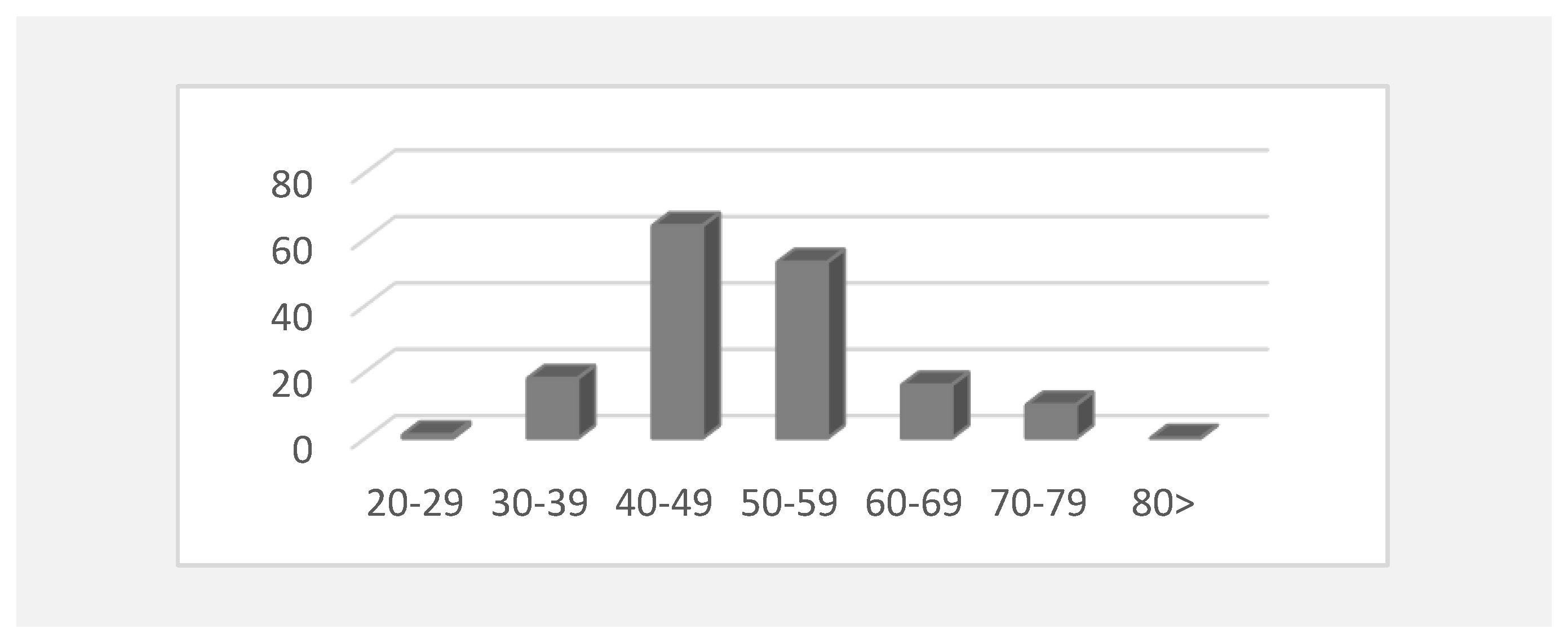

Background: The aim of this study was to assess the diagnostic accuracy for digital mammography, digital breast tomosynthesis, ultrasonography and breast MRI, as a screening methods in dense breasts, applied individually and in combination in detection of an early cancer. Methods: The retrospective study was conducted from January 2021 to september 2024 at the Oncology Institute of Vojvodina in Serbia, which included 168 women with dense breasts who were referred for an examination because of regular control or objective findings in breasts, and who underwent all 4 diagnostics imaging: digital mammography (DM), digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT), ultrasonography (US) and breast MRI. According to the 5th edition of ACR BIRADS atlas, suspicious malignancy was categorized as BIRADS 4 and 5, and benign findings as BIRADS 1, 2 and 3. The reference standard for checking the diagnostic accuracy of these methods was the result of histopathology, if the biopsy is done, or stable radiological finding in the next 12-24 months. Results: The examined women were aged from 28 to 77 years. Histopathology analysis revealed malignancy in 89 women, while 67 had a benign finding (19 was biopsy verified). DM has the lowest sensitivity (87.7%) and specificity (49.3%) in an early cancer detection. Adding of DBT to DM, sensitivity increased to 88.9%, and specificity to 56%. US has a high sensitivity of 90.1%, but a very low specificity of 48%. Breast MRI has the highest sensitivity 95.1%, and specificity 78.7%. Combination of DM+DBT and US yield increased the sensitivity, but decrease the specificity because of high rate of false positive findings. The highest PPV and NPV had breast MRI, 82.8% and 93.7% respectively, and the lowest digital mammography, 65.1% and 78.7% respectively. Adding of breast MRI to DM+DBT+US didnot significant change results in a sensitivity of 97.5%, but it has decreased specificity to 29.3%. Conclusions: US in combination with DM and DBT, can significantly improve the diagnostic accuracy in screening of dense breasts, similar as breast MRI, in regions where there are no magnetic resonance units. Limiting factors are low specificity and high PPV.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Selection

2.2. Imaging Protocols:

2.3. Image Interpretation

2.4. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Analysis of Histopathological findings of needle/surgical biopsies

3.3. Statistical Analysis of Four Radiological Diagnostics US, DM, DBT and Breast MRI in Correlation with HP Results

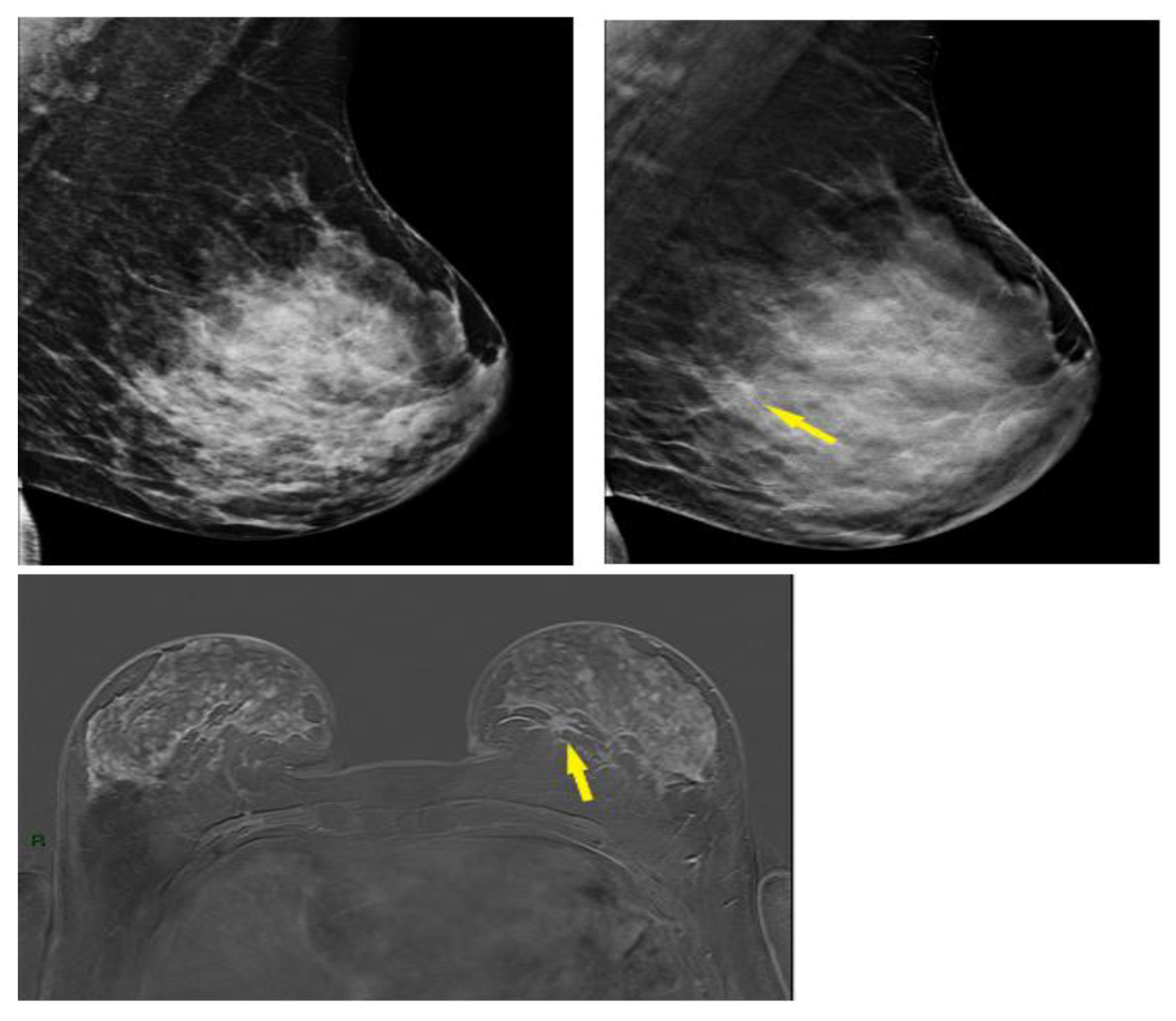

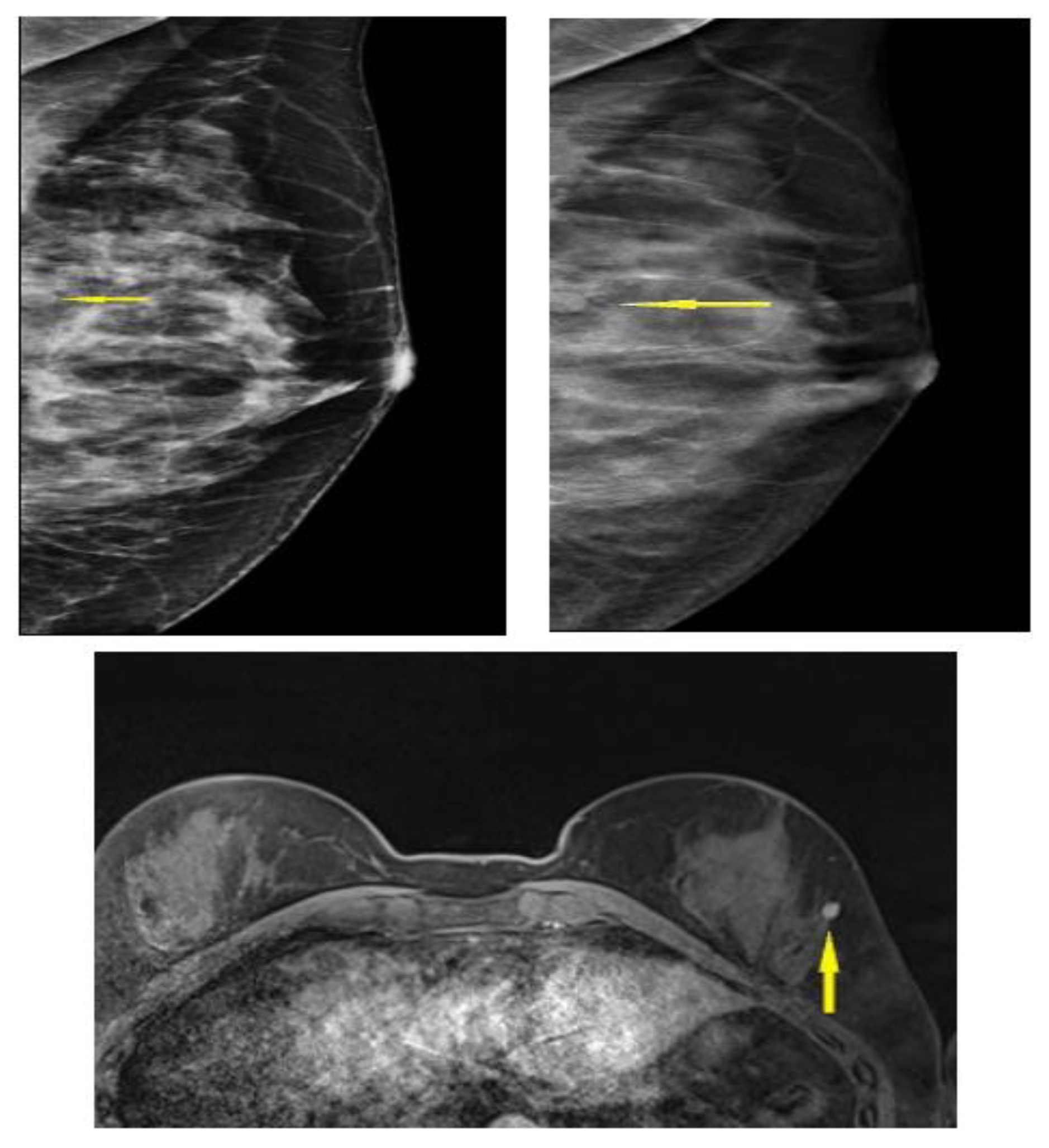

3.4. Selected Interesting Examples from Our Study

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ha, S.M.; Yi, A.;Yim D.: Jang, M.; Kwon, B.R.; Shin S.U.; et al. Digital Breast Tomosynthesis Plus Ultrasound Versus Digital Mammography Plus Ultrasound For Screening Breast Cancer in Women With Dense Breasts. Korean J Radiol 2023, 24, 274-283. PMCID: PMC10067692. [CrossRef]

- Winkler,N.S.; Raza, S.;Mackesy, M.; Birdwell R.L. Breast density: clinical implications and assessment methods. Radiographics 2015, 35, 316-324. [CrossRef]

- Sprague, BL.; Gangnon, R.E.; Burt, V.; Trentham-Dietz, A.; Hampton, J.M.; Wellman, R.D.; Kerlikowske, K.; Miglioretti, D.L. Prevalence of mammographically dense breasts in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014, 12, 106(10):dju255. [CrossRef]

- Berg, W.A.; Rafferty, E.A.; Friedewald, S.M.; Hruska, C.B.; Rahbar, H. Screening Algorithms in Dense Breasts: AJR Expert Panel Narrative Review. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2021, 216, 275–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, R.M.; Athanasiou, A.; Baltzer, P.A.T.; Camps-Herrero, J.; Clauser, P.; Fallenberg, E.M.; Forrai, G.; Fuchsjäger, M.H.; Helbich, T.H.; Killburn-Toppin, F.; Lesaru, M.; Panizza, P.; Pediconi, F.; Pijnappel, R.M.; Pinker, K.; Sardanelli, F.; Sella, T.; Thomassin-Naggara, I.; Zackrisson, S.; Gilbert, F.J.; Kuhl, C.K. European Society of Breast Imaging (EUSOBI). Breast cancer screening in women with extremely dense breasts recommendations of the European Society of Breast Imaging (EUSOBI). EurRadiol, 4036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Moy, L.; Heller, S.L. Digital Breast Tomosynthesis: Update on Technology, Evidence, and Clinical Practice. Radiographics 2021, 41, 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassis, I.; Lederman, D.; Ben-Arie, G.; Rosenthal, M.G.; Shelef, I.; Zigel, Y. Detection of breast cancer in digital breast tomosynthesis with vision transformers. Sci Rep 14 2024, 22149, 14. [CrossRef]

- Hadadi, I.; Clarke, J.; Rae, W.; McEntee, M.; Vincent, W.; Ekpo, E. Diagnostic Efficacy across Dense and Non-Dense Breasts during Digital Breast Tomosynthesis and Ultrasound Assessment for Recalled Women. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadhyay, N.; Wolska, J. Imaging the dense breast. J SurgOncol 2024, 130, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardanelli, F.; Magni, V.; Rossini, G.;Kilburn-Toppin, F.; Healy, N.A.; Gilbert, F.J. The paradox of MRI for breast cancer screening: high-risk and dense breasts—available evidence and current practice. Insights Imaging 2024, 15, 96. [CrossRef]

- Yi, A.; Jang, M.; Yim, D.; Kwon, BR.; Shin, SU.; Chang JM. Addition of Screening Breast US to Digital Mammography and Digital Breast Tomosynthesis for Breast Cancer Screening in Women at Average Risk. Radiology 2021, 298, 568-575. [CrossRef]

- Sudhir, R.; Sannapareddy, K.;Potlapalli, A.; Krishnamurthy, PB.; Buddha, S.; Koppula, V. Diagnostic accuracy of contrast-enhanced digital mammography in breast cancer detection in comparison to tomosynthesis, synthetic 2D mammography and tomosynthesis combined with ultrasound in women with dense breast. British Journal of Radiology 2021, 94, 20201046. [CrossRef]

- Romeih, M.; Raafat, T.A.; Ahmed, G.; Shalaby, SAM.; Ahmed, W.A.H. Value of digital breast tomosynthesis in characterization of breast lesions in dense breast. Egypt J RadiolNucl Med 2024, 55, 131. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, P.; Singh, N.; Raj, G.; Singh, R.; Malhotra, K.P.; Awasthi, N.P. Performance evaluation of digital mammography, digital breast tomosynthesis and ultrasound in the detection of breast cancer using pathology as gold standard: an institutional experience. Egypt J RadiolNucl Med 2022, 53, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Mansour, S.; Adel, L.; Mokhtar, O.; Omar O.S. Comparative study between breast tomosynthesis and classic digital mammography in the evaluation of different breast lesions. Egypt J RadiolNucl Med 2014, 45, 1053-61. [CrossRef]

- Skaane, P.; Bandos, AI.; Gullien, R.; Eben, EB.; Ekseth, U.; Haakenaasen, U.; Haakenaasen, U.; Izadi, M.; Jebsen, I.N.; Jahr, G.; Krager, M.; Niklason, L.T.; Hofvind, S.; Gur, D. Comparison of digital mammography alone and digital mammography plus tomosynthesis in a population-based screening program. Radiology 2013, 267, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Østerås,B.H.; Martinsen, A.C.T.; Gullien, R.; Skaane, P. Digital Mammography versus Breast Tomosynthesis: Impact of Breast Density on Diagnostic Performance in Population-based Screening. Radiology 2019, 293, 60-68. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, R.M.; Almalki, Y.E.; Basha, M.A.A.; Alduraibi, S.K.; Aboualkheir, M.; Almushayti, Z.A.; Aldhilan, A.S.; Aly, S.A.; Alshamy, A.A. The Impact of Adding Digital Breast Tomosynthesis to BI-RADS Categorization of Mammographically Equivocal Breast Lesions. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, J.; Yang, P.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Yang, K. Diagnostic accuracy of digital breast tomosynthesis versus digital mammography for benign and malignant lesions in breasts: a meta-analysis. Eur Radio 2014, 24(3), 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaane, P.; Bandos, A.I.; Niklason, L.T.; Sebuødegård, S.; Østerås, B.H.; Gullien, R.; Gur, D.; Hofvind, S.. Digital mammography versus digital mammography plus tomosynthesis in breast cancer screening: the Oslo Tomosynthesis Screening Trial. Radiology 2019, 291(1), 23–30. Epub 2019 Feb 19. PMID: 30777808. [CrossRef]

- Ohashi, R.; Nagao, M.; Nakamura, I.; Okamoto, T.; Sakai, S. Improvement in diagnostic performance of breast cancer: comparison between conventional digital mammography alone and conventional mammography plus digital breast tomosynthesis. Breast Cancer 2018, 25, 590–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedewald, S.M.; Rafferty, E.A.; Rose, S.L.; Durand, M.A.; Plecha, D.M.; Greenberg, J.S.; Hayes, M.K.; Copit, D.S.; Carlson, K.L.; Cink, T.M.; Barke, L.D.; Greer, L.N.; Miller, D.P.; Conant, E.F. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis in combination with digital mammography. JAMA 2014, 311, 2499–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alabousi, M.; Zha, N.; Salameh, J.P.; Samoilov, L.; Sharifabadi, A.D.; Pozdnyakov, A.; Sadeghirad, B.; Freitas, V.; McInnes, M.D.F.; Alabousi, A. Digital breast tomosynthesis for breast cancer detection: a diagnostic test accuracy systematic review and meta-analysis. EurRadiol 2020, 30, 2058-2071. Epub 2020 Jan 3. PMID: 31900699. [CrossRef]

- Marinovich, M.L.; Hunter, K.E.; Macaskill, P.; Houssami, N. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis or mammography: a meta-analysis of cancer detection and recall. J Natl Cancer Inst 2018, 110, 942–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardanelli, F.; Fallenberg, E.M.; Clauser, P.; Trimboli, R.M.; Camps-Herrero, J.; Helbich, T.H.; Forrai, G. European Society of Breast Imaging (EUSOBI), with language review by Europa Donna–The European Breast Cancer Coalition. Mammography: an update of the EUSOBI recommendations on information for women. Insights Imaging 2017, 8, 11-18. Epub 2016 Nov 16. PMID: 27854006; PMCID: PMC5265195.26. [CrossRef]

- Boroumand, G.;Teberian, I.; Parker, L.; Rao, V.M.; Levin D.C. Screening mammography and digital breast tomosynthesis: utilization updates. Am J Roentgenol 2018, 210, 1092–1096. Epub 2018 Mar 23. PMID: 29570370. [CrossRef]

- Alsheik, N.H.; Dabbous, F.; Pohlman, S.K.; Troeger, K.M.; Gliklich, R.E.; Donadio, G.M.; Su, Z.; Menon, V.; Conant, E.F. Comparison of resource utilization and clinical outcomes following screening with digital breast tomosynthesis versus digital mammography: findings from a learning health system. AcadRadiol 2019, 26, 597–605. Epub 2018 Jul 26. PMID: 30057195. [CrossRef]

- Hadadi, I.; Rae, W.; Clarke, J.; McEntee, M.; Ekpo, E. Breast cancer detection across dense and non-dense breasts: Markers of diagnostic confidence and efficacy. ActaRadiol Open 2022, 11, 20584601211072279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariscotti, G.; Houssami, N.; Durando, M.; Bergamasco, L.; Campanino, P.P.; Ruggieri, C.; Regini, E.; Luparia, A.; Bussone, R.; Sapino, A.; Fonio, P.; Gandini, G. Accuracy of mammography, digital breast tomosynthesis, ultrasound and MR imaging in preoperativeassessment of breast cancer. Anticancer Res 2014, 34, 1219–1225. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Keymeulen K.B.I.M.; Geurts S.M.E.; Kooreman LFS.; Duijm L.E.M.; Engeles S.; Vanwetswinkel S.; et al. Clinical value of contralateral breast cancers detected by pre-operative MRI in patients diagnosed with DCIS: a population-based cohort study. EurRadiol 2023, 33, 2209–2217. Epub 2022 Sep 30. PMID: 36180645; PMCID: PMC9935702. [CrossRef]

- Roganovic, D.; Djilas, D.; Vujnovic, S.; Pavic, D.; Stojanov D. Breast MRI, digital mammography and breast tomosynthesis: Comparison of three methods for early detection of breast cancer. Bos J Basic Med Sci 2015, 15, 64–68. PMID: 26614855; PMCID: PMC4690445. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.O.; Luz, L.A.D.; Chagas, D.C.; Amorim, J.R.; Nery-Júnior, E.J.; Alves, A.C.B.R.; Abreu-Neto, FT.; Oliveira, M.D.C.B.; Silva, D.R.C.; Soares-Júnior, J.M.; Silva, B.B.D. Evaluation of the accuracy of mammography, ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging in suspect breast lesions. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2020, 75, e1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badu-Peprah, A.; Adu-Sarkodie, Y. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis, mammography and ultrasonography in preoperative assessment of breast cancer. Ghan Med J 2018, 52, 133-139. PMID: 30602798; PMCID: PMC6303551. [CrossRef]

- Kolb,T.M.; Lichy, J.; Newhouse, J.H. Comparison of the performance of screening mammography, physical examination, and breast US and evaluation of factors that influence them: an analysis of 27,825 patient evaluations. Radiology 2002, 225, 165–175. PMID: 12355001. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Yang, S.Y.; Ahn, J.H.; Ko, E.Y.; Ko, E.S.; Han, B.K.; Choi, J.S . Digital Breast Tomosynthesis versus MRI as an Adjunct to Full-Field Digital Mammography for Preoperative Evaluation of Breast Cancer according to Mammographic Density. Korean J Radiol 2022, 23, 1031-1043. Epub 2022 Sep 16. PMID: 36126953; PMCID: PMC9614296. [CrossRef]

- Jochelson, M.S.; Pinker, K.; Dershaw, D.D.; Hughes, M.; Gibbons, G.F.; Rahbar, K.; Robson, M.E.; Mangino, D.A.; Goldman, D.; Moskowitz, C.S.; Morris, E.A.; Sung, JS. Comparison of screening CEDM and MRI for women at increased risk for breast cancer: A pilot study. Eur J Radiol 2017, 97, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H. Problem solving MR imaging of the breast. RadiolClin North Am 2004, 42, 919–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bluemke, D.A.; Gatsonis, C.A.; Chen, M.H.; DeAngelis, G.A.; DeBruhl, N.; Harms, S.; Heywang-Köbrunner, S.H.; Hylton, N.; Kuhl, C.K.; Lehman, C.; Pisano, E.D.; Causer, P.; Schnitt, S.J.; Smazal, S.F.; Stelling, C.B.; Weatherall, P.T.; Schnall, M.D. Magnetic resonance imaging of the breast prior to biopsy. JAMA 2004, 292, 2735–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orel, S.G.; Schnall, M.D.; LiVolsi, V.A.; Troupin, R.H. Suspicious breast lesions: MR imaging with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiology 1994, 190, 485–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang,Y., Ren, H. Meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging and mammography for breast cancer. J Cancer Res Ther 2017, 13, 862-868. [CrossRef]

- Pediconi, F.; Padula, S.; Dominelli, V.; Luciani, M.; Telesca, M.; Casali, V.; Kirchin, M.A.; Passariello, R.; Catalano.; C. Role of breast MR imaging for predicting malignancy of histologically borderline lesions diagnosed at core needle biopsy: prospective evaluation. Radiology 2010 , 257, 653-661. Epub 2010 Sep 30. PMID: 20884914. [CrossRef]

| Sequence | T2W TSE | T2WSTIR | DWI(EPI) | T1W 3D FLASH FS before and after bolus injection of contrast media |

| Imaging plane | axial | sagital | axial | axial |

| TR/TE (ms) (Time to repeat/time to echo) |

4900/76 | 6800/70 | 3700/60/80 | 5/3 |

| FA (0) (flip angle) |

120 |

120 |

150 |

10 |

| FOV (mm) (Field of view) |

340 | 240 | 340 | 340 |

| Matrix size | 380x380 | 320x290 | 220/220 | 380x320 |

| Slice thickness (mm) | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| Number of slices | 60 | 40 | 30 | 80 |

| Voxel size (mm) | 1x1x2 | 0,7x0,7x4 | 1,5x1,5x4 | 0,4x0,4x2 |

| Time of acquisition (s)/number of aquisition | 120/2 | 120/2 | 180/1 | 80/7 |

| B value(s/mm2) | - | - | 50;400;800 | - |

| Scan time (s) | 222 | 206 | 179 | 592 |

| Histopathological finding |

Benign lesions | Malignant lesions |

| n | n | |

| Invasive ductal carcinoma | 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 9 6 1 1 1 1 |

61 12 17 3 3 1 2 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 |

| Invasive lobular carcinoma | ||

| DCIS | ||

| LCIS | ||

| Papillary carcinoma | ||

| PCIS | ||

| Mucinous carcinoma | ||

| Metastases | ||

| Fibroadenoma | ||

| Fibrocystic breast changes (FCC) | ||

| Adenosis | ||

| Granulomatous mastitis | ||

| Papilloma | ||

| Mucocoela like lesions | ||

| TOTAL | 19 | 89 |

| Abbrevations: DCIS: ductal carcinoma in situ; LCIS: lobular carcinoma in situ; PCIS: papillary carcinoma in situ. | ||

| BI RADS category | US | Digital mammography | DBT | Breast MRI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malignant | Benign | Malignant | Benign | Malignant | Benign | Malignant | Benign | |

| 1 | 1 | 9 | 2 | 13 | 2 | 19 | 0 | 14 |

| 2 | 4 | 20 | 6 | 22 | 4 | 20 | 0 | 36 |

| 3 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 9 |

| 4 | 10 | 21 | 17 | 22 | 19 | 23 | 8 | 11 |

| 4A | 3 | 6 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 2 |

| 4B | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 4C | 4 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| 5 | 56 | 2 | 47 | 3 | 52 | 8 | 61 | 2 |

| Type of lesion | Histopathology | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malignant | Benign | Total | McNemar Test | |

| US | P<0.000 | |||

| Malignant | 73 (TP) | 39(FP) | 112 | |

| Benign | 8(FN) | 36(TN) | 44 | |

| DM | P<0.000 | |||

| Malignant | 71(TP) | 38(FP) | 109 | |

| Benign | 10(FN) | 37(TN) | 47 | |

| DBT | P<0.000 | |||

| Malignant | 72(TP) | 33(FP) | 105 | |

| Benign | 9(FN) | 42(TN) | 51 | |

| Breast MRI | P<0.000 | |||

| Malignant | 77(TP) | 16(FP) | 93 | |

| Benign | 4(FN) | 59(TN) | 63 | |

| DM+US | P<0.000 | |||

| Malignant | 78(TP) | 50(FP) | 128 | |

| Benign | 3(FN) | 25(TN) | 28 | |

| DM+DBT | P<0.000 | |||

| Malignant | 73(TP) | 40(FP) | 113 | |

| Benign | 8(FN) | 35(TN) | 43 | |

| DM+DBT+US | P<0.000 | |||

| Malignant | 78(TP) | 51(FP) | 129 | |

| Benign | 3(FN) | 24(TN) | 27 | |

| DM+DBT+US with breast MRI | P<0.000 | |||

| Malignant | 79(TP) | 53(FP) | 132 | |

| Benign | 2(FN) | 22(TN) | 24 | |

| Total | 81 | 75 | 156 | |

| Abbrevations: TP: true positive; FP: false positive; TN: true negative; FN: false negative | ||||

| Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Overall accuracy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US | 0,901 | 0,480 | 0,652 | 0,818 | 0,699 |

| DM | 0,877 | 0,493 | 0,651 | 0,787 | 0,692 |

| DBT | 0,889 | 0,560 | 0,686 | 0,824 | 0,731 |

| Breast MRI | 0,951 | 0,787 | 0,828 | 0,937 | 0,872 |

| DM+DBT | 0,901 | 0,467 | 0,646 | 0,814 | 0,692 |

| DM+DBT+US | 0,963 | 0,320 | 0,605 | 0,889 | 0,654 |

| DM+DBT+US+MRI | 0,975 | 0,293 | 0,598 | 0,917 | 0,647 |

| Abbrevations: PPV: positive predictive value; NPV: negative predictive value | |||||

| AUC | SE | P | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| US | 0.863 | 0.030 | 0.000 | 0.805-0.921 |

| DM | 0.820 | 0.034 | 0.000 | 0.754-0.886 |

| DBT | 0.828 | 0.033 | 0.000 | 0.763-0.893 |

| Breast MRI | 0.958 | 0.015 | 0.000 | 0.928-0.988 |

| Abbrevations: AUC: area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; SE: standard error; P: significance; 95% CI: 95% coefficient interval | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).