1. Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer and cause of death among women [

1]. Every woman is at risk for breast cancer. However, the level of risk is not the same for all, as this is dependent on the number, type, and combination of risk factors [

2]. The design of breast screening programmes based on the classifying women on risk factors of breast cancer may improve early diagnosis in younger age groups [

1].

For a screening test to be effective it must be safe, cost-effective, widely available, has a high detection rate and improve health outcomes. Mammography meets all these requirements [

3] and remains the mainstay in routine breast cancer screening. However, it is “

far from perfect” [

4], due to a low sensitivity (70%) which could result in a reduction of cancers detected [

4,

5]. Its sensitivity is limited due to dense breasts and tumour growth pattern making detection difficult or suggestive of benign disease [

6,

7,

8]. The decrease in sensitivity is intensified in young women with dense breasts and those who are at a higher risk of developing breast cancer (BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 mutation carriers) [

4,

5,

7,

9]. Since screening in high-risk women starts at an early age, mammography is also not ideal as there are concerns for young women to have an increased sensitivity to ionising radiation.

Breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) tends to be recommended for this category because certain breast cancers can be detected without the added radiation risk [

10]. MRI in its current use does not fulfil the criteria of a screening test, as it is not cost effective, neither rapid nor easily applied and is minimally invasive as requires the administration of intra-venous contrast [

6,

11]. However, out of all the available imaging modalities, MRI offers the highest diagnostic accuracy and sensitivity for the detection of breast cancer, irrespective of stage, type of cancer and breast density [

4,

6,

12]. MRI’s high sensitivity is due to the unmatched soft tissue contrast and functional information provided by MRI scans in conjunction with the correlation of angiogenic activity of cancers [

13]. Breast MRI is not influenced by age, breast density or any genetic mutations, therefore, any biologically relevant breast cancers are detected [

12]. The consideration of breast MRI for screening has increased greatly [

14]. The costs and lack of availability contribute to MRI being underutilised even in women at high-risk who need it the most [

6]. An abbreviated MRI protocol developed by Kuhl et al. in 2014 to counteract the limitations of time and cost of a full MRI protocol, provides promising results [

14].

This research study investigated the use of an abbreviated MRI breast protocol in the detection of breast cancer.

2. Materials and Methods

The study followed a quantitative, retrospective, comparative, non-experimental methodology.

An image data set was compiled from full protocol MRI breast examinations performed on patients between January 2019 to December 2021. A retrospective random sample of full protocol MRI breast examinations consisted of patients scanned on a 3.0-T (Tesla) MRI Philips Ingenia with a dedicated prone breast coil (7 channel coil); scanned using the same full protocol (

Table 1); had histo-pathological findings from a biopsy or availability of a 12-month of negative findings on follow-up imaging with either mammography, US, or MRI in the absence of a biopsy. The findings representing the true disease status from the gold standard were compared to findings of the original report based on the full protocol and having a pathological finding of breast lobular carcinoma. Examinations of patients with breast implants or previous breast surgery were excluded since it was essential that breast tissue was visible and not obscured. Other breast cancers besides lobular carcinoma were also excluded to satisfy uniformity of cases.

Image sequences making part of an abbreviated protocol were extracted from the full protocol (

Table 1). The image data set consisted of MR images of an abbreviated protocol for 35 examinations, with 10 examinations repeated to facilitate reliability, giving a total of 45 examinations for evaluation. The 35 cases reviewed consisted of 15 negative cases (normal) and 20 positive cases (abnormal). The histological report for the 20 abnormal cases showed lesions identified histologically as invasive lobular carcinoma with a histology grade of 2. Of these, 13 (65%) were on the left breast and 7 (35%) on the right breast. Out of 20 cases, seven (35%) had lymph node involvement. The gold standard for the normal cases was negative follow up imaging for at least 12 months with 15 cases followed by mammography (n=5), ultrasound (n=5), MRI (n=4) and DBT (n=1).

The mean patient age of the sample was 57.9 years with an age range of 27 to 80 years. The indications for MRI were 20 (57.1%) for breast cancer staging, 5 (14.3%) nipple discharge with a negative mammogram and ultrasound, 2 (5.7%) lesion characterisation and 8 (22.9%) screening due to family history or BRCA mutations. These clinical indications were available to radiologist when reporting on the MRI examinations performed with the full protocol.

During the image evaluation process, examinations were randomly presented to each radiologist. For each set, two radiologists, a breast specialist consultant >10 years’ experience and a resident breast specialist >5 years’ experience, completed an image quality scoring sheet.

Participating radiologists were not provided any patient history and only had access to the abbreviated protocol image sequences, which they could access from their respective workstation via the Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS). The display monitors had a 1280 x1024 (pixels) resolution with a maximum luminance of 200cd/m2. A Physikalisch Technische Werkstatten CD LUX metre model L991263 was used to measure the ambient illuminance which resulted in 39 Lux which falls within the American Association of Physicists in Medicine (report 270, 2019) recommended range.

For each set of examinations radiologists first indicated if there was a lesion present in the breast, and if yes, then more information was sought regarding the size, location, quadrant, number of lesions, lymph node involvement, and final BI-RADS score. All lesions identified were classified according to the BI-RADS classification system (American College of Radiology-BI-RADS, 2013), where a negative MRI examination was considered as BI-RADS 1 or 2 while a positive one considered as BI-RADS 3, 4 or 5. Taking BI-RADS ≥3 as the optimal classification criteria, the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) of the protocols were calculated.

Receiver Operator Characteristic (ROC) analysis was used to analyse the data. ROC curves were constructed using SPSS statistical software. A ROC curve has sensitivity (true positive) plotted on the y-axis against specificity (false positive) on the x-axis across cut-offs which generate the ROC curve. In this study the tests would represent the abbreviated and full protocols. The area under the curve (AUC) of a ROC graph is a measure which averages diagnostic accuracy across the test value spectrum [

15] (

Table 2).

3. Results

Cohen’s Kappa test was run to determine intra-rater reliability for the variables ‘is there a lesion present’ and ‘is there lymph node involvement’. The test revealed satisfactory results (k ranging between 0.6 to 0.78). The BIRADS score was assessed using the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) score (ICC score 0.6 and 0.9) which produced p-values of 0.021 and 0.0001 for radiologist A and B respectively, indicating statistically significant agreement between the readings for both individual radiologists.

Cohen’s Kappa test was also run to determine inter-rater reliability between radiologists for the same variables. The test revealed satisfactory results (k ranging between 0.6 to 0.8) as the statistical values were all < 0.05 indicating good significant inter-rater reliability. The BIRADS score was assessed also using the ICC score (ICC score ranging from 0.4 to 0.8) which produced p-values of 0.086 and 0.0001. BI-RADS score by radiologist A was lower than that of radiologist B, which led to a low inter-rater reliability.

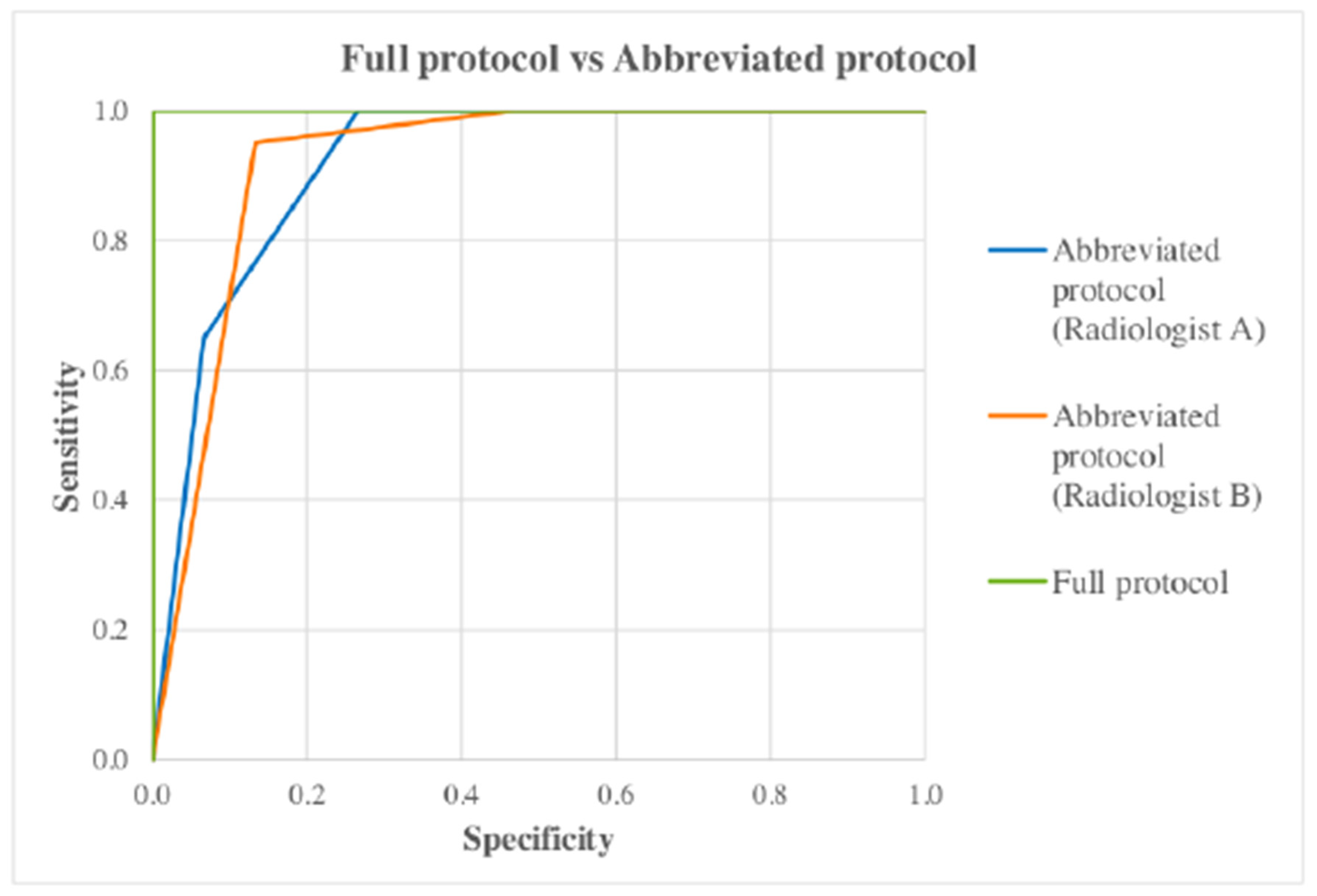

ROC curves were constructed using for the full and abbreviated protocol (for both radiologists individually) as well as for both radiologists together (

Figure 1) to show the difference in terms of diagnostic accuracy between the protocol. The gold standard was represented as either 0 or 1 depending on whether the case was positive (1) or negative (0). Other variables (full and abbreviated) would represent the BI-RADS classification given to each case for the different protocols, with higher numbers indicating greater positivity.

When all AUC were compared, the p-value (asymptotic sig. 2-tail) for each pair was >0.05 (

Table 3) indicating no significant difference in the effectiveness of the full and abbreviated protocol to detect breast cancer.

AUC were compared with each other to check for statistical significance by using a pairwise comparison design. The AUC obtained from each ROC curve was 1 for the full protocol, 0.920 and 0.922 for radiologist A and B for the abbreviated protocol respectively. The p-value for all protocols was <0.05 (

Table 4) which indicates that each test diagnosed the disease state (cancer yes/no) at a statistically significant level. This indicates that when using the abbreviated protocol the diagnostic accuracy was maintained.

3.1. Full Protocol Analysis

The ROC

AUC for the full protocol was 1, indicating the full protocol as outstanding in distinguishing between a negative and a positive case. The accuracy of the full protocol was 100% for all performance indicators (

Table 5), therefore the full protocol was accurate as the gold standard in diagnosing patients as normal or having a breast cancer present.

3.2. Abbreviated Protocol Analysis (Radiologist A - Consultant)

Since the full protocol and gold standard agreed 100%, then the full protocol could also be considered as the gold standard. The ROC

AUC for the abbreviated protocol for Radiologist A was 0.92 and considered as outstanding at discrimination.

Table 6 illustrates the ratings of images obtained from the 35 cases by Radiologist A. There were no positive cases missed. The accuracy of the abbreviated protocol for Radiologist A was 88.6% (31/35). Performance indicators for Radiologist A are presented in table 7.

3.3. Abbreviated Protocol Analysis (Radiologist B - Resident Specialist)

The ROC

AUC for the abbreviated protocol for Radiologist B was 0.922 and considered outstanding at discrimination.

Table 5 illustrates the ratings of images obtained from the 35 cases by Radiologist B. There were no positive cases missed. The accuracy of the abbreviated protocol for Radiologist B was 80% which indicates that when using the abbreviated protocol, radiologist B accurately classified 28 out of 35 cases correctly. Performance indicators for radiologist B are presented in table 7.

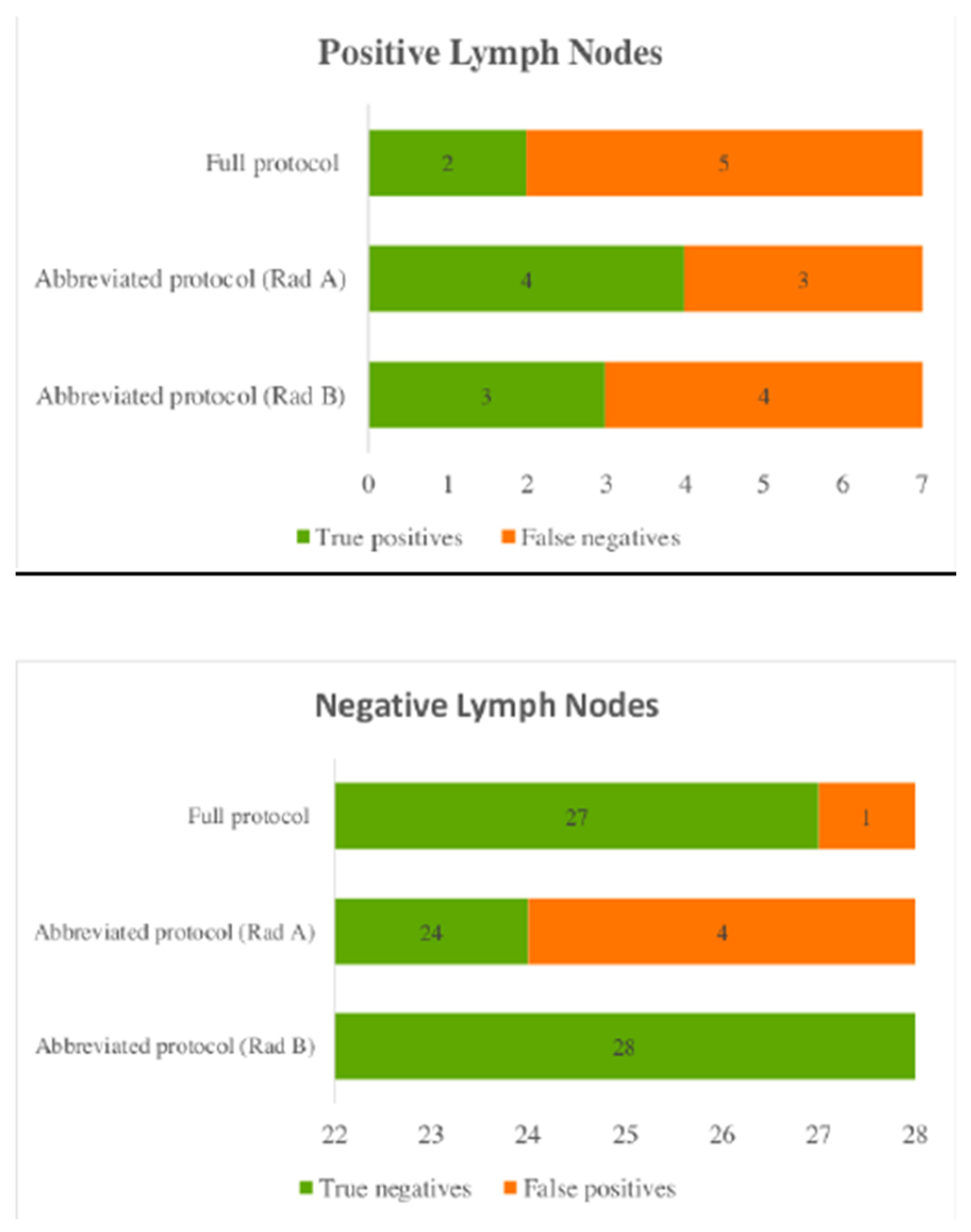

3.4. Lymph Node Involvement

Lymph node involvement was defined by any presence of disease based on the histological result. Out of the 20 breast cancer cases seven had histologically proven lymph node metastasis.

Using the abbreviated protocol radiologist A had the greatest false positives, with 4 cases marked as positive lymph nodes when they were normal. Radiologist B correctly detected all normal lymph nodes using the abbreviated protocol (

Figure 2).

3.5. Location and Number of Lesions

Using the full protocol all lesions were detected on the correct breast by both radiologists. While when using the abbreviated protocol, Radiologist A marked two cases as having a lesion on the right breast and two on the left breast, however, these cases were negative. Radiologist B marked four cases with a lesion on the right and three on the left breast, these cases were negative. There was one case where both radiologists marked both breasts having a pathology, when the breast cancer was in the left breast only.

Besides the location, the number of lesions detected for each positive case were evaluated. Using the full protocol the number of lesions for 18 out of 20 positive cases (90%) matched. While when using the abbreviated protocol, both radiologists matched 15 out of 20 (75%) positive cases.

3.6. Breast Localisation and Size of Lesion

The breast location and size of the lesion could not be accurately assessed because of the inability to correlate the specific location and size with those on the histopathological result, in retrospect. However, when compared to the full protocol, from a total of 20 cases, using the abbreviated protocol, Radiologist A matched the exact location for 12 cases while Radiologist B matched 16.

In this study radiologists listed the size in either of all three dimensions (anteroposterior (AP), transverse (TRA) and craniocaudal (CC)) or only specified two or one size in a particular direction. Therefore, due to these limitations accurate comparison could not be made.

4. Discussion

The assessment of the abbreviated protocol for both participating radiologists showed a 100% sensitivity detecting all cancers, which was the same as that for the full protocol. Studies, such as Heacock et al. (2015) and Mango et al. (2015) showed that cancer detection rate is similar when using the abbreviated protocol. Both studies had a similar sample population to the current study, which included biopsy proven cancers. Heacock et al. (2015) reported all invasive breast cancers detected with reduced sequences while Mango et al (2015) concluded all cancers visualised by at least one of the four readers involved in their study [

16,

17]. Petrillo et al. (2017) performed a retrospective study on selected cases and both full and abbreviated protocols detected 206 out of 207 cancers, showing no difference in diagnostic performance. These comparable findings further support that the abbreviated protocol is effective for cancer detection [

18].

Although the sensitivity of the abbreviated protocol was 100%, its specificity compared to the full protocol differed. The specificity of the abbreviated protocol was significantly lower for radiologists A and B at 73.3% and 53.5% respectively when compared to that of the full protocol. The low specificity indicates an increase in the false positive rates. False positives are associated with unnecessary further imaging, biopsy, and additional follow-up examinations to exclude the presence of breast cancer [

19]. Recalls are associated with increased patient anxiety, health care costs and very rarely morbidities related with biopsy [

19,

20]. Women who undergo a biopsy due to a false positive, are 2.3 times less likely to attend future screening within 30 months after the recall [

21].

Radiologist B had lower specificity than radiologist A. This could be related to years of experience. The gap between the average expertise in reading mammograms when compared to reading MRI studies may be the reason for the limited specificity of breast MRI imaging [

22]. The study by Kuhl et al. (2014) suggests that the expertise of interpreting radiologists will help to limit false-positive diagnosis. Radiologists who wish to engage in European screening programs, must report 5000 mammograms per year. Thus, Kuhl et al. (2014) suggests that if an MRI screening program is to be implemented then the radiologic community must undergo the same process it went through with the propagation of mammographic screening process to improve MRI reporting expertise [

14].

In this study, the abbreviated protocol was effective for demonstrating cancers however, 11.4% (4) and 20% (7) normal cases were reported as false positives for radiologist A and B respectively. In the study by [

23] the rate of false positives was 4.9% (7) and 8.4% (12) for senior (5 years’ experience) and junior (6-months experience) radiologists. The number of normal cases missed were much higher than in this study, however, the total sample size was larger (90 women). Even in other studies [

18,

24,

25], the specificity of the abbreviated protocol was always lower that of the full protocol. However, reader specificity in the current study was lower than 90%, the result reported in other studies [

9,

26]. The reason may be because the radiologists participating in the current study did not have access to previous imaging and biopsy results and were unable to confirm long-term stability and correlate any lesion findings with other imaging modalities. The readers in the study by [

27] also did not have access to previous imaging studies and obtained a comparable low specificity (45% and 52%).

The high value of NPV produced by the abbreviated protocol was 100% for both readers produced strong evidence that the abbreviated protocol was able to exclude the presence of cancer. The NPV was the same for both full and abbreviated protocols and is comparable to other studies [

14,

18,

24,

25,

28]. The higher the PPV, the lower the false positive outcomes [

29]. The PPV value for the full protocol was 100% while that of the abbreviated protocol for Radiologist A was 83.3%, better than the 74% obtained by Radiologist B. In the study by Chen et al. (2017) [

24] the PPV value for the abbreviated protocol was also lower than the full protocol at 22 % and 40% respectively.

5. Conclusions

There was no significant difference in the diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity and NPV) between the full and abbreviated protocol to detect breast cancer, produced strong evidence that the abbreviated protocol was able to exclude the presence of cancer. However, the abbreviated protocol achieved a low specificity. A low specificity and PPV has the disadvantage that subjects not having the disease will screen positive and receive unnecessary follow-up tests which may have a potential risk and contribute to increasing costs.

The abbreviated protocol is an easy and simple technique and there should be no difficulty in implementing this procedure as it is a concise version of the full protocol. No additional equipment or training for radiographers is needed and at no added cost. It involves less scanning time and reading time for the radiologists. It could enable a higher number of examinations to be performed within the same MR session and translate into cost-effectiveness and better use of resources.

When implementing a new technique there is a great chance of high false positives rates however, this may be overcome with training and an increase in reporting numbers. Further training to radiologists is required to ensure that a more uniform threshold is used when determining the need to recall patients for an abnormality. These recommendations should be considered before the implementation of an MRI abbreviated protocol as a screening tool.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, X.X. and Y.Y.; methodology, X.X.; software, X.X.; validation, X.X., Y.Y. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, X.X.; investigation, X.X.; resources, X.X.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, X.X.; writing—review and editing, X.X.; visualization, X.X.; supervision, X.X.; project administration, X.X.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Faculty Research Ethics Committee (FREC) and University Research Ethics Committee (UREC), University of Malta (FHS-2021-00038). for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to ethical reasons.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their appreciation to all participating radiologists for their contribution towards the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AUC |

Area Under the Curve |

| BI-RADS |

Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System |

| BRCA |

Breast Cancer Gene |

| DBT |

Digital Breast Tomosynthesis |

| DWI |

Diffusion Weighted Imaging |

| FREC |

Faculty Research Ethics Committee |

| ICC |

Intraclass correlation coefficient |

| MIP |

Maximum Intensity Projection |

| MRI |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| NPV |

Negative Predictive Value |

| PACS |

Picture Archiving and Communication System |

| PPV |

Positive Predictive Value |

| ROC |

Receiver Operating Characteristics |

| SPSS |

Statistical l Package for Social Sciences software |

| T |

Tesla |

| UREC |

University Research Ethics Committee |

| US |

Ultrasound |

References

- Momenimovahed, Z., & Salehiniya, H. (2019). Epidemiological characteristics of and risk factors for breast cancer in the world. Breast Cancer: Targets and Therapy, Volume 11, 151–164. [CrossRef]

- Łukasiewicz, S., Czeczelewski, M., Forma, A., Baj, J., Sitarz, R., & Stanisławek, A. (2021). Breast Cancer—Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Classification, Prognostic Markers, and Current Treatment Strategies—An Updated Review. Cancers, 13(17), 4287.

- Seely, J. M. (2017). How Effective Is Mammography as a Screening Tool? Current Breast Cancer Reports, 9(4), 251–258. [CrossRef]

- Chhor, C. M., & Mercado, C. L. (2017). Abbreviated MRI Protocols: Wave of the Future for Breast Cancer Screening. American Journal of Roentgenology, 208(2), 284–289. [CrossRef]

- Deike-Hofmann, K., Koenig, F., Paech, D., Dreher, C., Delorme, S., Schlemmer, H.-P., & Bickelhaupt, S. (2019). Abbreviated MRI Protocols in Breast Cancer Diagnostics: Abbreviated Breast MRI. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 49(3), 647–658. [CrossRef]

- Kuhl, C. K. (2019). Abbreviated Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) for Breast Cancer Screening: Rationale, Concept, and Transfer to Clinical Practice. Annual Review of Medicine, 70(1), 501–519. [CrossRef]

- Mootz, A. R., Madhuranthakam, A. J., Department of Radiology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical School, Texas, USA, Dogan, B., & Department of Radiology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical School, Texas, USA. (2019). Changing Paradigms in Breast Cancer Screening: Abbreviated Breast MRI. European Journal of Breast Health, 15(1), 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Roganovic, D., Djilas, D., Vujnovic, S., Pavic, D., & Stojanov, D. (2015). Breast MRI, digital mammography and breast tomosynthesis: Comparison of three methods for early detection of breast cancer. Bosnian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences, 15(4). [CrossRef]

- Kriege, M., Brekelmans, C. T. M., Zonderland, H. M., Kok, T., & Meijer, S. (2004). Efficacy of MRI and Mammography for Breast-Cancer Screening in Women with a Familial or Genetic Predisposition. The New England Journal of Medicine, 11.

- Reeves, R. A. , & Kaufman, T. (2022). Mammography. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

- Gunduru, M. , & Grigorian, C. (2021). Breast Magnetic Resonance Imaging. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539727/) 122.

- Riedl, C. C., Luft, N., Bernhart, C., Weber, M., Bernathova, M., Tea, M.-K. M., Rudas, M., Singer, C. F., & Helbich, T. H. (2015). Triple-Modality Screening Trial for Familial Breast Cancer Underlines the Importance of Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Questions the Role of Mammography and Ultrasound Regardless of Patient Mutation Status, Age, and Breast Density. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 33(10), 1128–1135. [CrossRef]

- Sung, J. S., Stamler, S., Brooks, J., Kaplan, J., Huang, T., Dershaw, D. D., Lee, C. H., Morris, E. A., & Comstock, C. E. (2016). Breast Cancers Detected at Screening MR Imaging and Mammography in Patients at High Risk: Method of Detection Reflects Tumor Histopathologic Results. Radiology, 280(3), 716–722. [CrossRef]

- Kuhl, C. K., Schrading, S., Strobel, K., Schild, H. H., Hilgers, R.-D., & Bieling, H. B. (2014). Abbreviated Breast Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): First Postcontrast Subtracted Images and Maximum-Intensity Projection—A Novel Approach to Breast Cancer Screening With MRI. JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY, 10.

- Hajian-Tilaki K. (2013). Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve Analysis for Medical Diagnostic Test Evaluation. Caspian journal of internal medicine, 4(2), 627–635.

- Heacock, L., Melsaether, A. N., Heller, S. L., Gao, Y., Pysarenko, K. M., Babb, J. S., Kim, S. G., & Moy, L. (2016). Evaluation of a known breast cancer using an abbreviated breast MRI protocol: Correlation of imaging characteristics and pathology with lesion detection and conspicuity. European Journal of Radiology, 85(4), 815–823. [CrossRef]

- Mango, V. L., Morris, E. A., David Dershaw, D., Abramson, A., Fry, C., Moskowitz, C. S., Hughes, M., Kaplan, J., & Jochelson, M. S. (2015). Abbreviated protocol for breast MRI: Are multiple sequences needed for cancer detection? European Journal of Radiology, 84(1), 65–70. [CrossRef]

- Petrillo, A., Fusco, R., Sansone, M., Cerbone, M., Filice, S., Porto, A., Rubulotta, M. R., D’Aiuto, M., Avino, F., Di Bonito, M., & Botti, G. (2017). Abbreviated breast dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging for lesion detection and characterization: The experience of an Italian oncologic center. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 164(2), 401–410. [CrossRef]

- Dekker, B. M., Bakker, M. F., de Lange, S. V., Veldhuis, W. B., van Diest, P. J., Duvivier, K. M., Lobbes, M. B. I., Loo, C. E., Mann, R. M., Monninkhof, E. M., Veltman, J., Pijnappel, R. M., van Gils, C. H., For the DENSE Trial Study Group, van Gils, C. H., Bakker, M. F., de Lange, S. V., Veenhuizen, S. G. A., Veldhuis, W. B., … de Koning, H. J. (2021). Reducing False-Positive Screening MRI Rate in Women with Extremely Dense Breasts Using Prediction Models Based on Data from the DENSE Trial. Radiology, 301(2), 283–292. [CrossRef]

- Tosteson, A. N. A., Fryback, D. G., Hammond, C. S., Hanna, L. G., Grove, M. R., Brown, M., Wang, Q., Lindfors, K., & Pisano, E. D. (2014). Consequences of False-Positive Screening Mammograms. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(6), 954. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y., Winget, M., & Yuan, Y. (2017). The impact of false positive breast cancer screening mammograms on screening retention: A retrospective population cohort study in Alberta, Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 108(5–6), e539–e545. [CrossRef]

- Kuhl, C. (2007). The Current Status of Breast MR Imaging Part I. Choice of Technique, Image Interpretation, Diagnostic Accuracy, and Transfer to Clinical Practice. Radiology, 244(2), 356–378. [CrossRef]

- Oldrini, G., Derraz, I., Salleron, J., Marchal, F., & Henrot, P. (2018). Impact of an abbreviated protocol for breast MRI in diagnostic accuracy. Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, 24(1), 12–16. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-Q., Huang, M., Shen, Y.-Y., Liu, C.-L., & Xu, C.-X. (2017). Application of Abbreviated Protocol of Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Breast Cancer Screening in Dense Breast Tissue. Academic Radiology, 24(3), 316–320. [CrossRef]

- Machida, Y., Shimauchi, A., Kanemaki, Y., Igarashi, T., Harada, M., & Fukuma, E. (2017). Feasibility and potential limitations of abbreviated breast MRI: An observer study using an enriched cohort. Breast Cancer, 24(3), 411–419. [CrossRef]

- Lehman, C. D., Arao, R. F., Sprague, B. L., Lee, J. M., Buist, D. S. M., Kerlikowske, K., Henderson, L. M., Onega, T., Tosteson, A. N. A., Rauscher, G. H., & Miglioretti, D. L. (2017). National Performance Benchmarks for Modern Screening Digital Mammography: Update from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium. Radiology, 283(1), 49–58. [CrossRef]

- Grimm, L. J., Soo, M. S., Yoon, S., Kim, C., Ghate, S. V., & Johnson, K. S. (2015). Abbreviated Screening Protocol for Breast MRI. Academic Radiology, 22(9), 1157–1162. [CrossRef]

- Moschetta, M., Telegrafo, M., Rella, L., Stabile Ianora, A. A., & Angelelli, G. (2016). Abbreviated Combined MR Protocol: A New Faster Strategy for Characterizing Breast Lesions. Clinical Breast Cancer, 16(3), 207–211. [CrossRef]

- Trevethan, R. (2017). Sensitivity, Specificity, and Predictive Values: Foundations, Pliabilities, and Pitfalls in Research and Practice. Frontiers in Public Health, 5, 307. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).