1. Introduction

The temperature of discharged molten slag is approximately 1500 °C. With an annual production of more than 600 million tons of molten slag, approximately 1.54 × 1012 MJ of heat (equivalent to 5.26 × 107 tons of standard coal) is lost. By harnessing this heat, it is possible to reduce CO2 emissions by 1.42×108 tons and significantly cut energy costs.

The direct utilization of molten slag in the preparation of building materials such as glass-ceramic and cast stone has become a research hotspot [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. This approach not only achieves the resourceful utilization of slag but also fully utilizes its heat energy. Among them, the preparation process of cast stone employs the Petrurgic method. Unlike the two-step or one-step methods that involve cooling the slag into glass before nucleation and crystallization, the Petrurgic method is a heat treatment process that directly performs crystallization during the cooling process of the melt [

7]. This is similar to the process of magma cooling and solidifying into lava in a natural environment. This method has been used to manufacture cast stone pipes or plates by heating and melting basalt. A large number of studies have also applied the Petrurgic method to the preparation of glass-ceramics or cast stone from blast-furnace slag [

5,

6,

9], steel slag [

3,

10], copper slag [

7,

11], silicomanganese [

1,

4], etc.

Due to the absence of a dedicated nucleation process, slags employed in the Petrurgic method must possess excellent nucleation and crystallization properties. Current research in this field primarily focuses on adjusting the crystallization performance of slag cast stones, including the addition of nucleation agents [

1,

4,

12,

13] and optimizing crystallization temperatures [

1,

4,

12,

14]. Additionally, slags should exhibit the characteristic of “long slag” during casting and shaping, which refers to a gradual decrease in viscosity as the temperature decreases [

15,

16]. Excessively rapid crystallization rates can lead to a rapid increase in viscosity, hindering the casting process of slags. Silicon-manganese ferroalloy slags have a high production volume and high discharge temperatures, making large-scale utilization challenging [

11,

17,

18]. However, due to their high silicon and aluminum content, they are suitable for the preparation of cast stone materials. Directly utilizing silicon-manganese slags for the preparation of cast stone materials not only enhances the added value of the slags but also avoids the remelting process, contributing to energy conservation and emission reduction. This holds significant importance.

Direct air cooling of silicon-manganese slag results in the formation of an amorphous phase, thereby rendering it unsuitable for direct production of qualified cast stone products. Consequently, conditioning treatment is necessary for the silicon-manganese slag. Prior studies have demonstrated that chromium-containing modifiers effectively modulate the crystallization properties of silicon-manganese slag, facilitating the production of qualified glass-ceramics or cast stone. Deng et al. [

16] successfully synthesized CaO-MgO-Al

2O

3-SiO

2 glass-ceramics with varying Cr

2O

3 concentrations, utilizing blast furnace slag as the primary raw material via traditional smelting techniques. The results revealed that the synthesized glass-ceramics comprises dendritic diopside (primary crystalline phase) and bulk spinel (secondary crystalline phase). The samples exhibited crystallization activation energies ranging from 378 to 454 kJ/mol, with minor fluctuations. Additionally, the crystallization index increased from 0.84 to 2.80. Yang [

1] employed silicomanganese slag as the primary raw material, incorporating chrome-bearing modifier silica, iron scale, and chrome-iron slag, to successfully fabricate ordinary pyroxene glass-ceramics that meet the performance criteria of natural granite stone using the Petrurgic one-step method. The results demonstrate that the crystallization properties of the modified slag are significantly enhanced compared to the original silica manganese slag, with ferrochrome slag favoring the formation of granular or short rod-shaped pyroxene crystals with particle sizes ranging from 0.2 to 0.5 μm.

To ensure smooth operation of the casting process, the modified slag not only needs to possess excellent crystallization properties, but also maintain suitable viscosity characteristics, thus preventing a rapid increase in viscosity due to crystallization. This study focused on the improving poor crystallization properties in raw silicomanganese slag by modifying its composition, and at the same time, discussed the potential impact of crystallization on its viscosity. It is provides a theoretical basis for utilizing sensible heat to develop economically efficient and environmentally friendly low-carbon technologies, and has potential application prospects in the production of cast stone and glass ceramics building materials.

2. Materials and Experiments

2.1. Sample Preparation

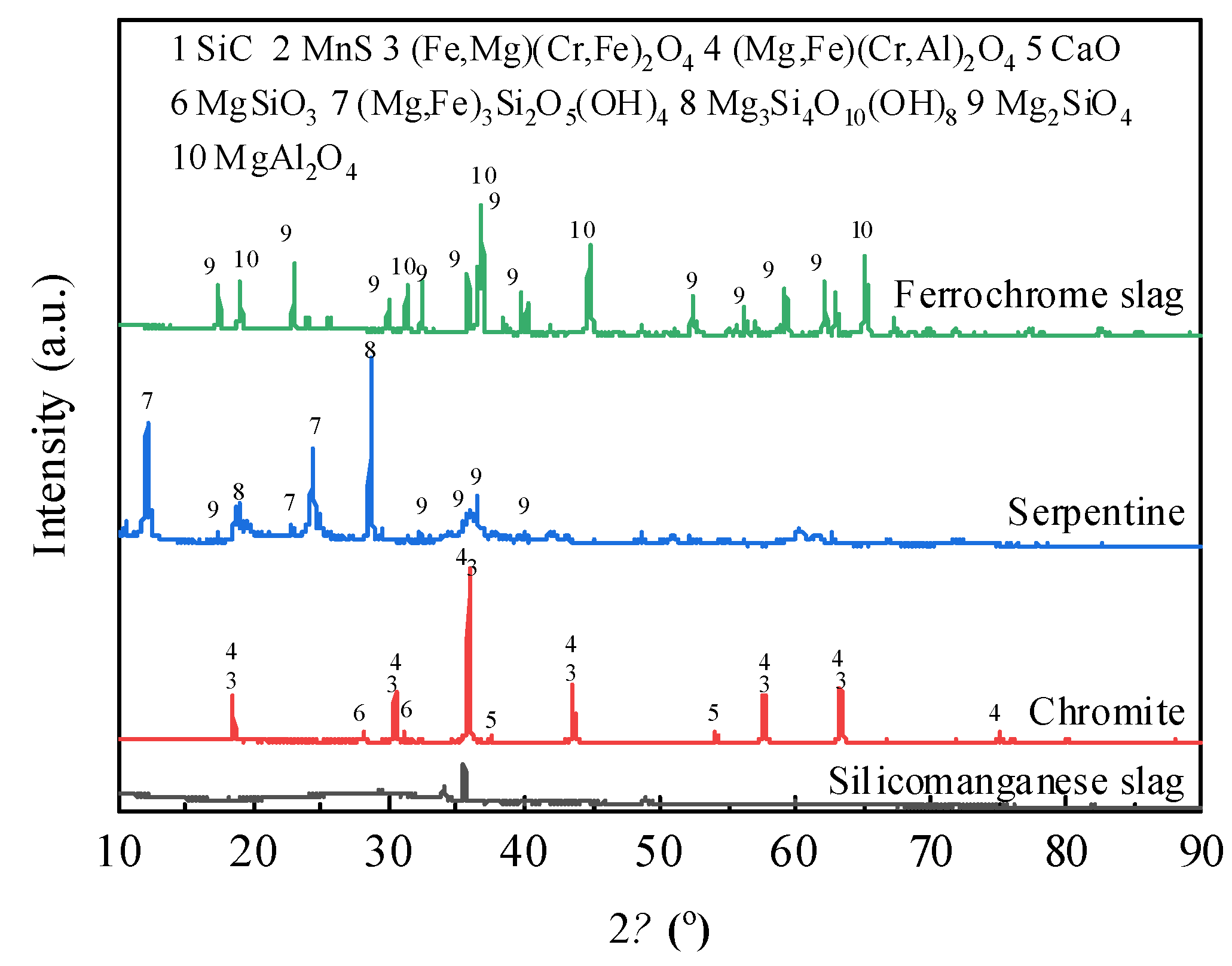

The experiments utilized raw materials including silicomanganese slag, chromite, serpentine, and ferrochrome slag, all originating from Inner Mongolia, China. The chemical and mineral compositions of the raw materials were analyzed using X-ray fluorescence (XRF) and X-ray diffraction (XRD). The respective results are presented in

Table 1 and

Figure 1. The lumpy raw materials were crushed into powder and mixed according to the ratio of silicomanganese slag: chromite: serpentine = 92:6:2 (S2) and silicomanganese slag: chromite iron slag = 80:20 (S3). The chemical composition of the mixed samples is presented in

Table 2. The 10 g uniformly mixed powder was placed in a corundum crucible and then put into a muffle furnace at 1500 °C. It was melted for 60 min under an argon (Ar) atmosphere to ensure complete melting and uniform mixing of the powder. Subsequently, they were kept at 1500 ℃, 1300 ℃, 1100 ℃ and 1000 ℃ for 30 min respectively, and then quenched, dried and crushed. The powder samples were sieved through a 0.075 mm sieve. Mineral phases were analyzed using XRD (SMART LAB (9), Rigaku, Japan) on samples of approximately 2 g at each temperature, with a scanning speed of 10 degrees per minute and a 2

θ range of 10

o to 90

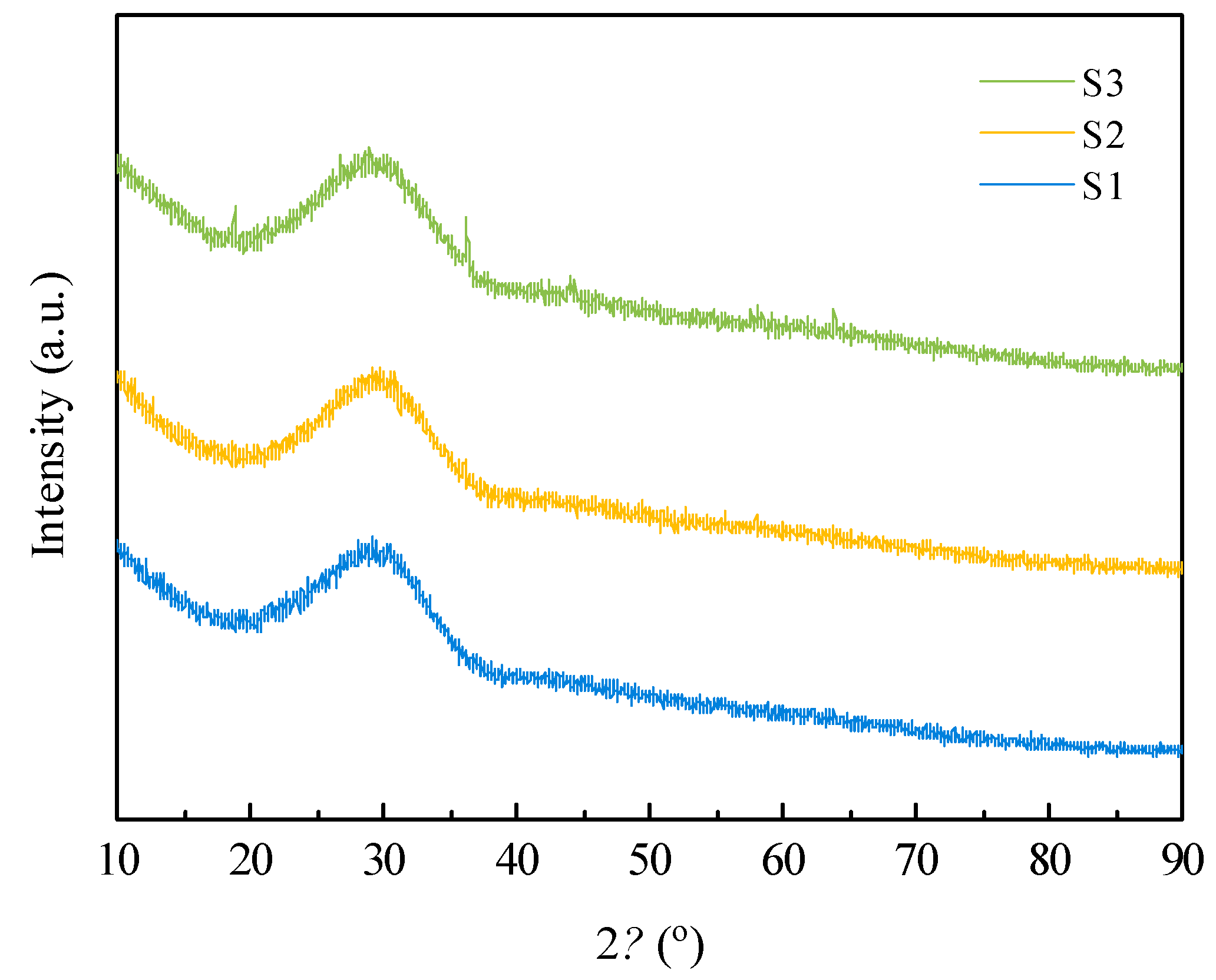

o. XRD analysis shows that the slag samples quenched at 1500 ℃ were all amorphous, as shown in

Figure 2. The XRD pattern of the quenched slag exhibits a prominent bun-shaped diffraction peak in the range of 2

θ = 20°~40°, with limited other diffraction peaks. This indicates that the samples were mainly composed of amorphous glass material, the raw material and modifier were integrated, and the chemical composition was uniform.

The corundum crucible (99% Al

2O

3) containing 500 g of mixed slag was placed in the muffle furnace, heating in Ar atmosphere with the furnace to 1500 ℃, maintained for 60 min, and then cooled to 1300 °C. The corundum crucible was removed, and the slag was quickly poured into the preheated mold, and then cover it. It was maintained at the crystallization temperature for 60 min. Subsequently, the temperature was reduced to an annealing temperature of 700 °C, maintained for 60 min, and then cooled within the furnace. The experiment simulates the mixing process of hot slag with the modifier, despite the fact that the cold slag was remelted after its mixture with the modifier. The experimental steps are depicted in

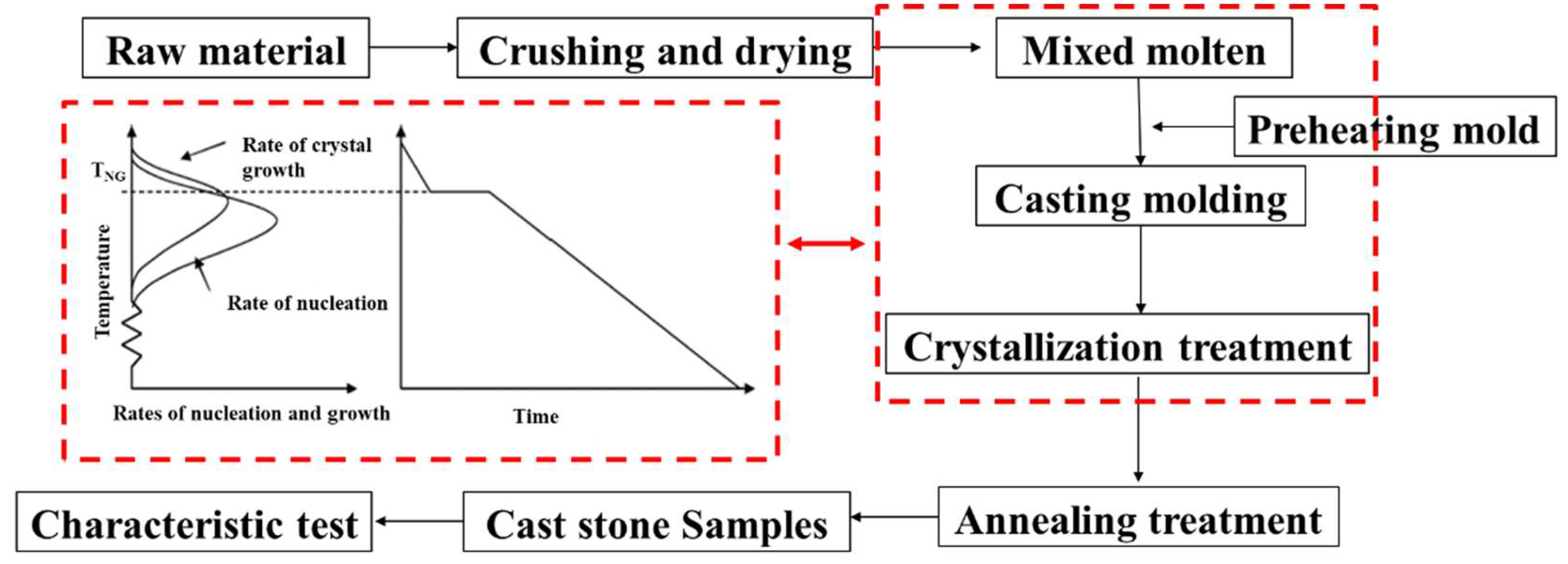

Figure 3, with the red dotted box highlighting the mechanism of the Petrurgic method.

2.2. Experimental Methods

2.2.1. Non-Isothermal DSC Measurement

The non-isothermal crystallization characteristics of silicomanganese slag were studied by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC, Netzsch STA449F3; Netzsch Instrument Inc., Germany) under an argon (Ar) atmosphere at 60 mL min–1. Approximately 50 mg of slag sample was placed into a platinum crucible with an inner diameter of 5 mm and a height of 5.5 mm. The slag was heated from room temperature to 1500 oC at 30 oC min–1 and held for 1 min to eliminate air bubbles and homogenize the chemical composition and temperature. Subsequently, the temperature was reduced to 350 °C with cooling rates of 10 °C min–1, 20 °C min–1, and 30 °C min–1. DSC data were automatically recorded during the heating and cooling cycles.

2.2.2. Viscosity Measurement

The viscosity of molten slag was measured using a rotary viscometer (Model DV2T-LV, Brookfield, USA) employing the rotary cylinder method. The heating element of the blast furnace consisted of a U-shaped MoSi2 rod, with temperature measurements conducted using a B-type (Pt-30% Rh: Pt-6% Rh) thermocouple. To prevent chemical reactions with the slag melt, molybdenum (Mo) material was utilized for the crucible, probe, and connecting rod in the experiments. Prior to each measurement, three standard silicone oils with viscosities of 0.0973 Pa s, 0.490 Pa s, and 0.985 Pa s were subjected to a 30-minute equilibration period in a constant-temperature water tank set at 25°C for viscosity calibration. Subsequently, approximately 250 g of slag was loaded into a Mo crucible shielded by a graphite crucible under Ar gas (99.99%, 0.5 NL min–1). The slag was then heated to 1550 °C and maintained at this temperature for 30 min to ensure homogenization of both the slag's temperature and chemical composition. Following this, a Mo rotor was introduced into the slag and rotated at 13 r min–1 to measure the viscosity. Throughout the continuous cooling process, the slag was cooled at a rate of 5 °C/min, and viscosity measurements were conducted at intervals to monitor changes in viscosity as the slag cooled. This comprehensive approach to measuring the viscosity of molten slag provides valuable insights into its rheological behavior under varying temperature conditions, contributing to a deeper understanding of its properties and potential applications.

2.2.3. FT-IR and XPS Spectra Measurement

The structure of the 1500 ℃ quenching slag sample was tested. The structural characteristics of the glass samples were determined using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR, Nicolet iS50, USA), with transmittance spectra recorded within the range of 4000 to 400 cm⁻¹. Additionally, X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS, AXISULTRA-DLD, Japan) was employed to investigate the chemical bonding states.

2.2.4. Physical Properties Test of Cast Stone

After cutting the heat-treated samples, the flexural strength, water absorption rate, and bulk density were tested according to the building materials standard (GB/T 18601-2009 “Natural Granite Building Panels”). The flexural test samples were 3×4×10 mm in size and tested on an electronic universal testing machine (TZS-6000, China). The flexural performance was evaluated using a four-point bending method with a crosshead speed of 0.5 mm·min-1. The water absorption rate and bulk density of the samples were measured using a ceramic water absorption vacuum device (CXK-A, China) and a precision ceramic bulk.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Mechanical Properties of Cast Stone

The glass-ceramic samples of silicomanganese slag prepared in the laboratory according to three different sets of formulations with dimensions of 40 × 40 × 10 mm were photographed as shown in

Figure 4. Unlike the other two samples, S1 has a glassy luster in its cross-section, which has been subsequently confirmed to consist almost of an amorphous phase. From table 3, the bending strength, bulk density and water absorption of modified samples S2 and S3 cast stone samples prepared by modified silicomanganese slag were 37.50 and 35.70 Mpa, 3.11 and 3.09 g·cm

-3, and 0.32% and 0.22%, respectively, meeting the requirement of GB/T18601-2009 "Natural granite building Panel" (bending strength ≥ 8.3 MPa, bulk density ≥ 2.56 g·cm

-3, water absorption ≤0.4%). Among them, according to the formula of S2, the silicomanganese slag cast stone raw stone was successfully prepared in the factory site (see

Figure 4). In this study, the method of using sensible heat to melt the modifier directly is mainly to provide a new way to solve the bulk utilization of the silicomanganese slag. Under the premise of meeting the building materials standard, the sensible heat in the silicomanganese slag was simply modified to prepare the cast stone with low production cost, which provided a theoretical basis for industrialization.

3.2. Analysis of Crystallization Performance of Silicomanganese Slag

3.2.1. Crystallization Temperature

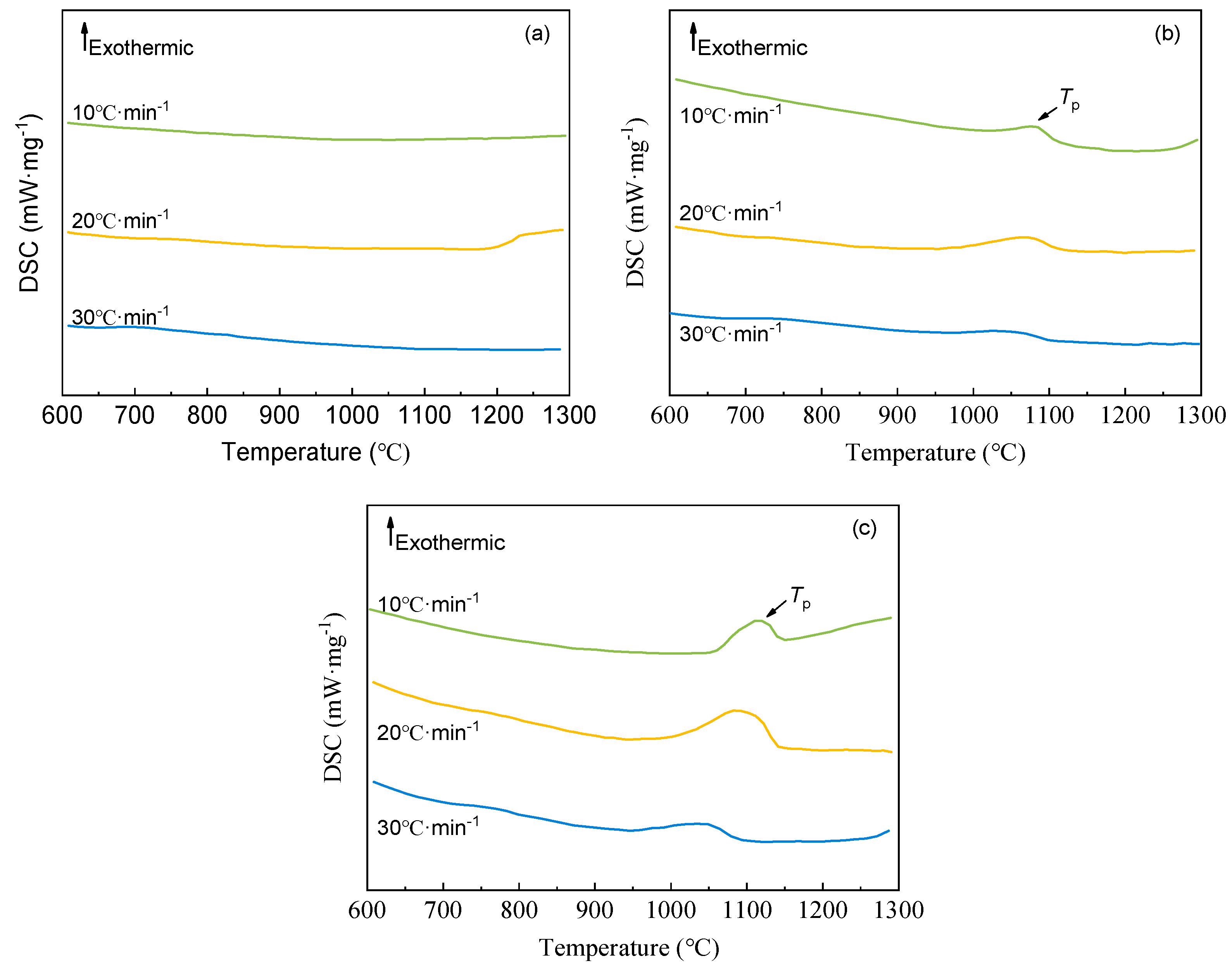

The crystallization behavior of the silicomanganese slags was investigated using the non-isothermal differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) method.

Figure 5 presents the results of the non-isothermal DSC experiments for samples S1, S2, and S3 at cooling rates of 10 ℃ min

–1, 20 ℃ min

–1, and 30 ℃ min

–1, respectively, with corresponding parameter information of theothermic peak detailed in

Table 4.

Notably, the DSC curves of the modified silicomanganese slag samples S2 and S3 exhibit distinct exothermic peaks across the three different cooling rates, indicating their propensity for crystallization. Nevertheless, the DSC curves of the raw slag sample S1 show hardly any evidence of exothermic peaks under the same cooling rate conditions. This observation suggests that the raw silicomanganese slag exhibits poor crystallization behavior, underscoring the beneficial effects of its modification in promoting crystal formation, which constitutes a key rationale for the modification efforts in this study.

Furthermore, the cooling rate is known to influence the shape and shifting of the exothermic peak. As depicted in

Figure 5(b) and (c), decreasing the cooling rate results in sharper peak shapes, increased peak intensities, and higher peak tip temperatures. Conversely, higher cooling rates yield blunter and lower exothermic peaks, and in some cases, it is difficult to identify exothermic peaks. This may be attributed to the high silicon content in the raw materials, which makes it difficult for the original slag to crystallize. Modifiers are used to promote crystallization, but at higher cooling rates, crystallization is often not sufficient, resulting in reduced crystallization exothermicity. Additionally, since the nucleation temperature of crystals is lower than the growth temperature [

19], higher cooling rates require a greater driving force to promote nucleation and crystal growth [

20,

21,

22]. As the cooling process proceeds and the temperature gradually decreases, the ion migration rate also decreases, posing a challenge to crystal growth.

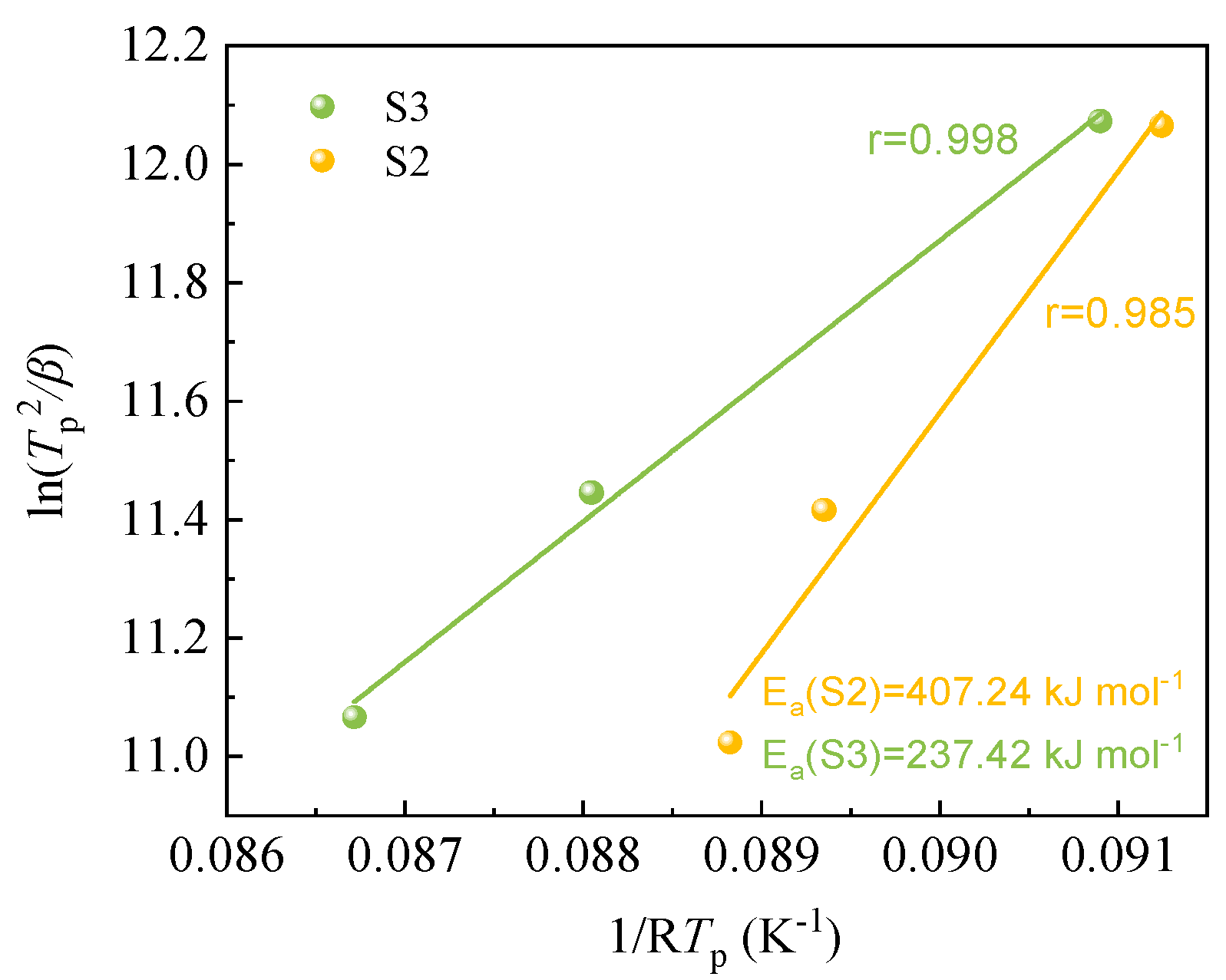

3.2.2. Crystallization Activation Energy

The above analysis shows that the addition of different modifiers affects the crystallization process of the silicomanganese slag and may lead to differences in the slag structure, and the energetic barriers that must be overcome to rearrange the atoms in the crystallization process, which ultimately leads to different crystallizability of the samples. It can be analyzed by crystallization kinetic methods [

22,

23,

24]. Various models have been established to reveal the crystallization activation energy and crystallization index of metallurgical slag and polymers under non-isothermal conditions. In this study, the analysis was conducted by Kissinger and Augis–Bennett equations [

25], and the calculated parameters are shown in

Table 4. The Kissinger equation as Eq. (1):

where

Ea (kJ·mol

–1) is the crystallization activation energy,

β (℃·min

–1) is the cooling rate,

Tp (℃) represent the maximum crystallization peak temperature value, R (8.314 J/(mol K)) is the gas constant, and C is a constant.

According to Eq. (1), a plot of

versus

yields discrete points and a linear fitting curve (see

Figure 6). The slope and Pearson correlation coefficient of the linear fit lines are the crystallization activation energy

Ea and r, respectively, which have been represented in Fig.6. The activation energy calculation results showed that the crystallization activation energy for S2 and S3 samples were 407.24 kJ mol

–1 and 237.42 kJ mol

–1, respectively, and S3 had a lower crystallization activation energy than S2. This is attributed to the increased content of nucleating agents in the modified silicomanganese slag, which promotes non-uniform nucleation of the silicomanganese slag, and the melting point of the spinel generated by S3 is higher than that of S2, resulting in easier crystallization of S3.

3.2.3. Crystalline Phases

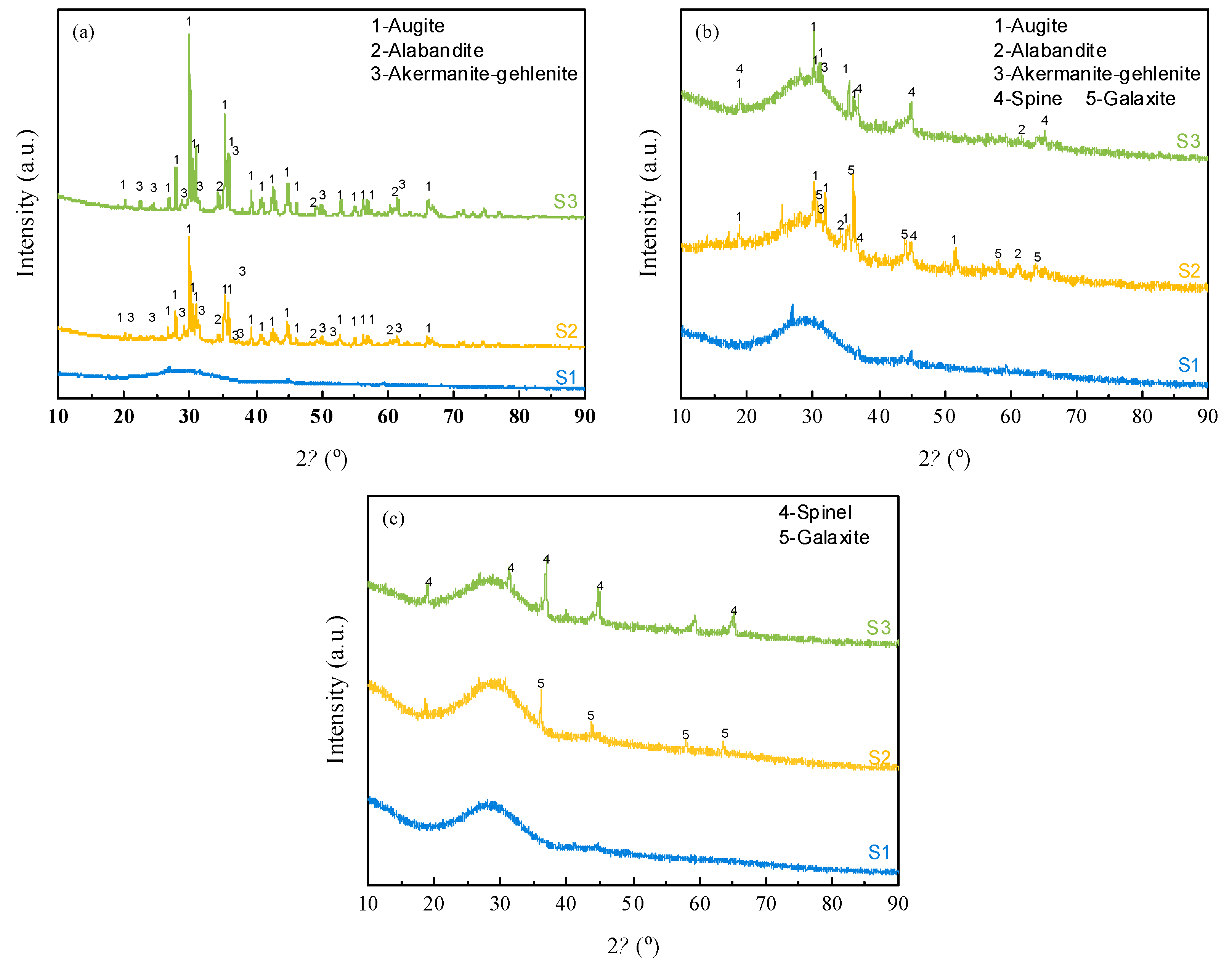

To investigate the crystallization behavior of silicomanganese slag under two modification methods, the samples were heated to 1500 ℃ to melt, then lowered to 1300 ℃, 1100 ℃ and 1100 ℃ for 30 min, and finally quenched. The corresponding XRD results are shown in

Figure 7. The XRD findings align with the non-isothermal DSC results, providing further insights into the crystallization characteristics of the studied slags. The XRD and DSC analyses converge in confirming that the raw silicomanganese slag (S1) exhibits poor crystallization tendencies. Moreover, the XRD results reveal that the positions of the diffraction peaks for samples S3 and S2 at 1000 °C are nearly identical, indicating the presence of the same crystalline phase in both. Further examination of the intensity and shift of the diffraction peaks indicates that the primary crystals in both S2 and S3 are augite, along with spinel-group minerals such as galaxite (Mn

2+, Mg)(Al, Cr

3+ ,Fe

3+)

2O

4 and normal spinel (Mg(Cr

3+, Al)

2O

4) at 1300 °C and 1100 °C, which subsequently disappear at 1000 °C. Additionally, Akermanite-gehlenite is observed in association with augite at 1000 °C.

The distinctions observed in the galaxite (Mn

2+, Mg)(Al, Cr

3+, Fe

3+)

2O

4 and normal spinel Mg(Cr

3+, Al)

2O

4 can be attributed to the chemical composition of the slag. The higher content of Mn

2+ and Fe

2+/3+ in S2, along with the elevated Mg

2+ content in S3, create favorable thermodynamic conditions for the crystallization of galaxite and normal spinel. By adjusting the chemical composition of the silicomanganese slag through the introduction of Cr

3+, Fe

2+/3+, and Mg

2+ ions in the modifier, these ions combine with Al

3+ and Mn

2+ ions in the slag to form galaxite and spinel. Furthermore, both galaxite and spinel serve as effective nucleating agents, facilitating the generation of augite and enhancing the crystalline properties of the silicomanganese slag, a finding consistent with previous research [

26,

27].

In the context of producing casting stone from silicomanganese slag, the presence of small dispersed spinel does not significantly impact the fluidity of the molten slag due to its size, while also promoting the formation of ordinary augite. Consequently, the enhanced crystallization ability of silicomanganese slag positively influences its suitability for conversion into casting stone. These findings underscore the potential benefits of improving the crystallization properties of silicomanganese slag for its downstream applications.

3.3. Analysis Of Fluidity Performance of Silicomanganese Slag

3.3.1. Viscosity of Silicomanganese Slag

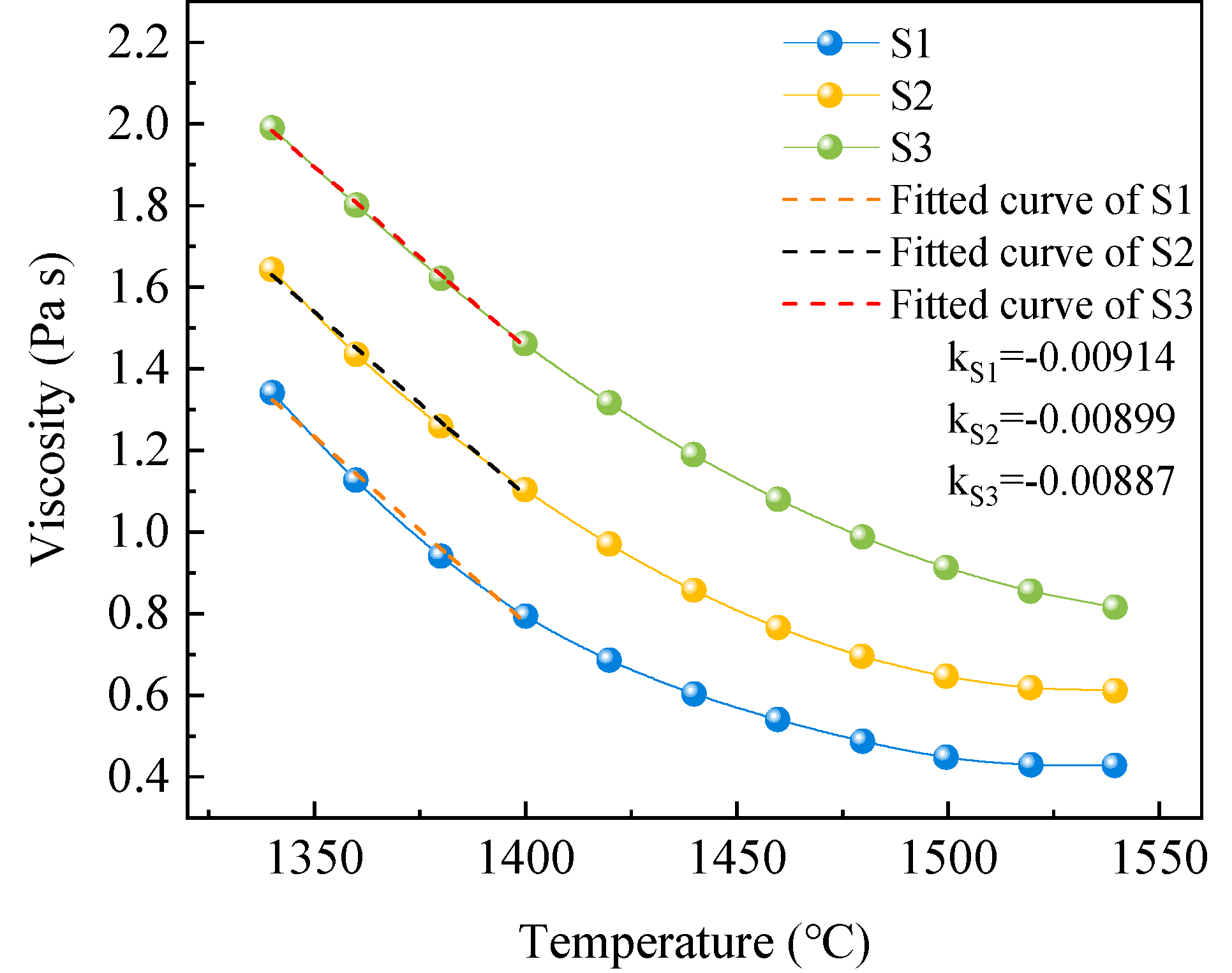

The measured viscosity of silicomanganese slag with different modifiers at various temperatures is depicted in

Figure 8. The results reveal that the viscosity of silicomanganese slag at the same temperature follows the order S1 < S2 < S3, attributable to the gradual decrease in its R value (mass%CaO/mass%SiO

2), leading to elevated viscosity and increased complexity of the aluminosilicate structure. This trend aligns with findings reported by several researchers [

28,

29,

30,

31]. Furthermore, the viscosity-temperature curves of the modified silicomanganese slags demonstrate a relatively flat profile, with all curves exhibiting an approximately hyperbolic shape, indicative of long slag characteristics (acidic slag). Notably, as the temperature decreases to the pouring temperature of the slag (1340~1400 ℃), the viscosity-temperature curves of the silicomanganese slag exhibit minimal indication of turning points caused by the generation of spinel-group minerals. The absence of crystal phase generation in S1 can be attributed to its high viscosity and the insufficient content of existing nucleating agents to promote crystal precipitation. Despite the enhancement in viscosity of S2 and S3, their crystallization performance remains superior to that of silicon manganese slag S1. This suggests that the modifier plays a more prominent role in decreasing the activation energy required for crystallization, outweighing the inhibitory effects of increased viscosity on crystallization.

The process of forming cast stone involves transforming the slag into a product with a solid geometry, requiring the cast stone to be fluid within a specific temperature range for formability [

32]. By performing a linear fit to the viscosity curves of

Figure 8 in the temperature range of 1340~1400 ℃, it was found that the slopes of S1, S2, and S3 gradually increased, with values of -0.00914, -0.00899, and -0.00887, respectively. This indicates that the viscosity of the modified silicomanganese slag changes more gradually with decreasing temperature compared to the raw silicomanganese slag. For cast stone material production, obtaining a long slag through modified slag is advantageous, as it not only reduces abrupt viscosity changes due to crystallization but also provides a certain degree of softening to stress, inhibiting the formation of defects during the cooling process and enhancing product quality. Modified silicomanganese slags S2 and S3 not only demonstrate excellent crystallization properties but also maintain good fluidity during the casting process. Due to the slow and fine crystallization, the viscosity mutation caused by crystallization is effectively avoided, which is beneficial for the casting process.

3.3.2. Activation energy for viscous flow of silicomanganese slag

The activation energy for viscous flow of molten slag is an important parameter indicator to describe the viscous behavior of slag and is an energy barrier that the cohesive flow units in slag must overcome when moving between different equilibrium states [

33]. It is usually expressed by the Arrhenius formula (Eq. (2)).

where

η is the viscosity, Pa s;

A is the pre-exponential factor;

Eη is the activation energy for viscous flow, J mol

–1;

R is the universal gas constant, J mol

–1 K

–1;

T is the absolute temperature, K.

Taking the logarithm of Eq. (2) gives the following expression:

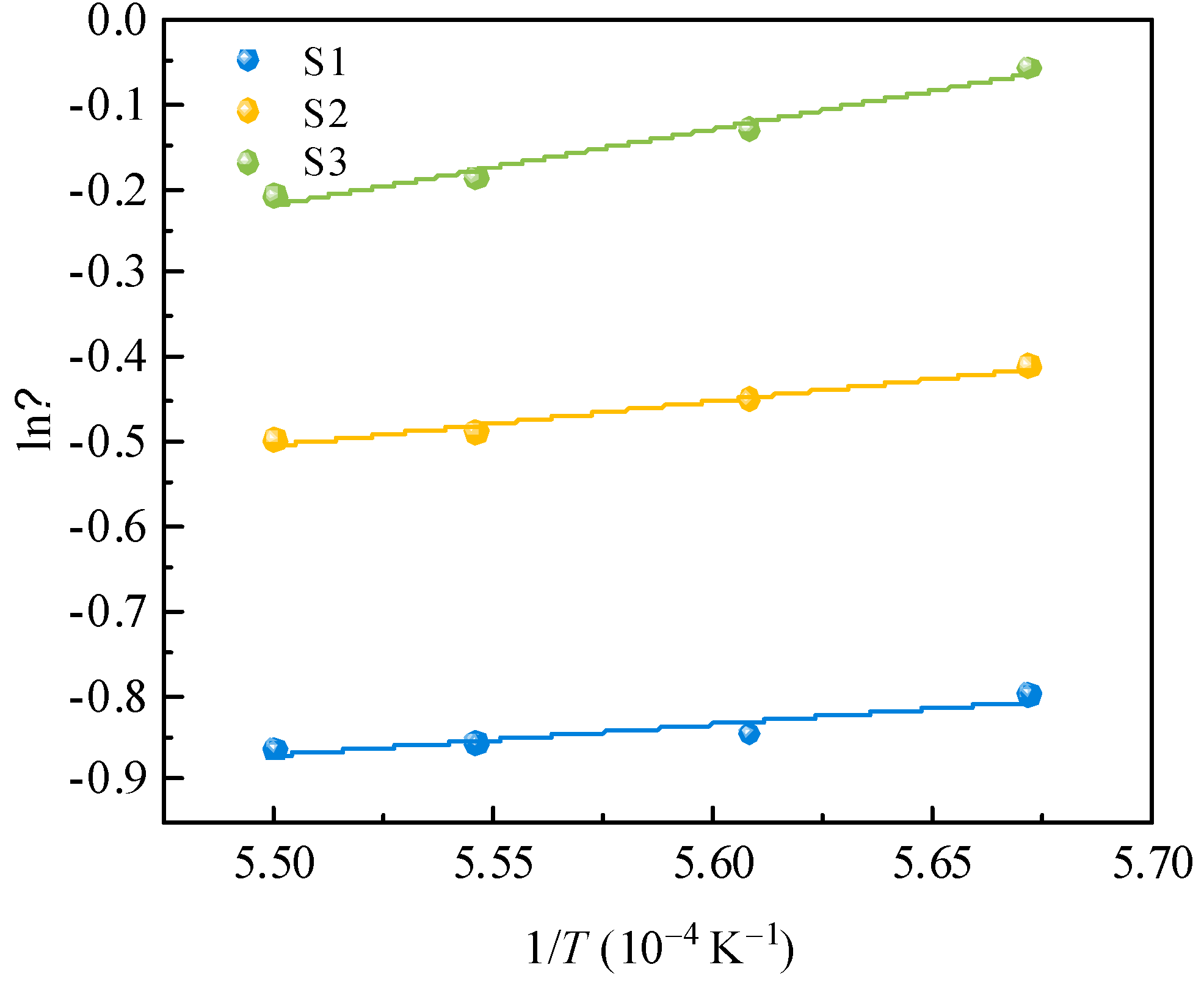

Figure 9 presents the fitted relationship between the ln

η and 1/

T. Based on the experimental data, the activation energy for viscous flow

Eη can be obtained from the slope of the fitted straight line. As can be seen in

Figure 9, ln

η has a good linear relationship with 1/

T, and the linear dependence coefficient of each fitted line is higher than 0.99. The calculated activation energy for viscous flow is shown in

Table 5. The activation energy for viscous flow before and after the modification in

Table 5 were 30.38 ± 8.34 kJ mol

–1 (S1), 43.70 ± 5.14 kJ mol

–1 (S2), and 74.93 ± 8.07 kJ mol

–1 (S3), respectively. It indicates an increased in the energy barrier for viscous flow and the formation of some more complex structural units in the slag, which results in a higher viscosity of slag melts. The activation energy for viscous flow values and viscosity values showed the same trend, indicating that the viscous flow resistance of silicomanganese slag increased after modification.

3.4. The relationship between performance and structure of cast stone

3.4.1. FT-IR Spectra Analysis

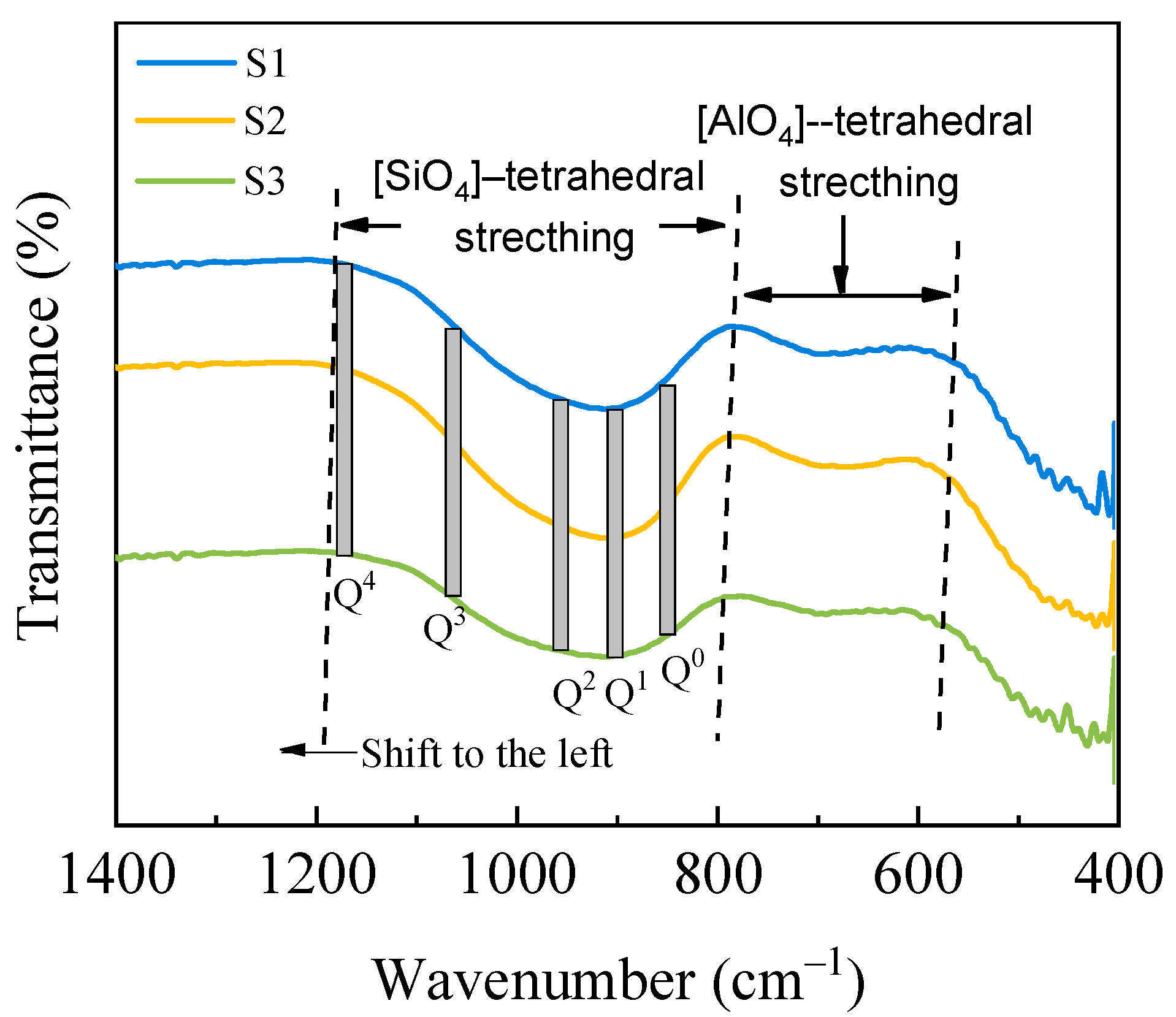

Figure 10 presents the FT-IR spectra of the raw and modified silicomanganese slag samples within the 1400–400 cm

-1 shift range, which can be divided into two distinct regions: the high-frequency region (1200–800 cm

–1) and the low-frequency region (800–600 cm

–1). The characteristic peaks in these shift ranges have been attributed based on related research by other authors, as outlined in

Table 6. The presence of [SiO

4]-tetrahedra signifies the network structure of the glass, while the widened absorption band in the 1200–800 cm

–1 range is associated with the stretching vibration of the [SiO

4]-tetrahedral Si–O bonds influenced by varying quantities of bridging oxygen Q

n (

n=0, 1, 2, 3, and 4). Additionally, Al

3+ ions function as glass network intermediates and occupy the [AlO

4]-tetrahedral structure formed by non-bridging oxygen [

34], with absorption bands in the 800–600 cm

–1 range attributed to [AlO

4]-tetrahedral stretching vibration.

This analysis places greater emphasis on the stretching vibration of the [SiO4]-tetrahedron due to the relatively higher SiO2 content in the samples, resulting in a correspondingly stronger absorption band associated with the [SiO4]-tetrahedron. Notably, the absorption bands corresponding to the [SiO4]-tetrahedral of samples S2 and S3 are observed to shift toward the high-frequency region compared to S1, indicating an increase in the number of [SiO4]-tetrahedra with more bridging oxygen. This suggests an increase in the polymerization of the modified silicomanganese slag samples S2 and S3, contributing to elevated mobility temperature and viscosity of the modified slag.

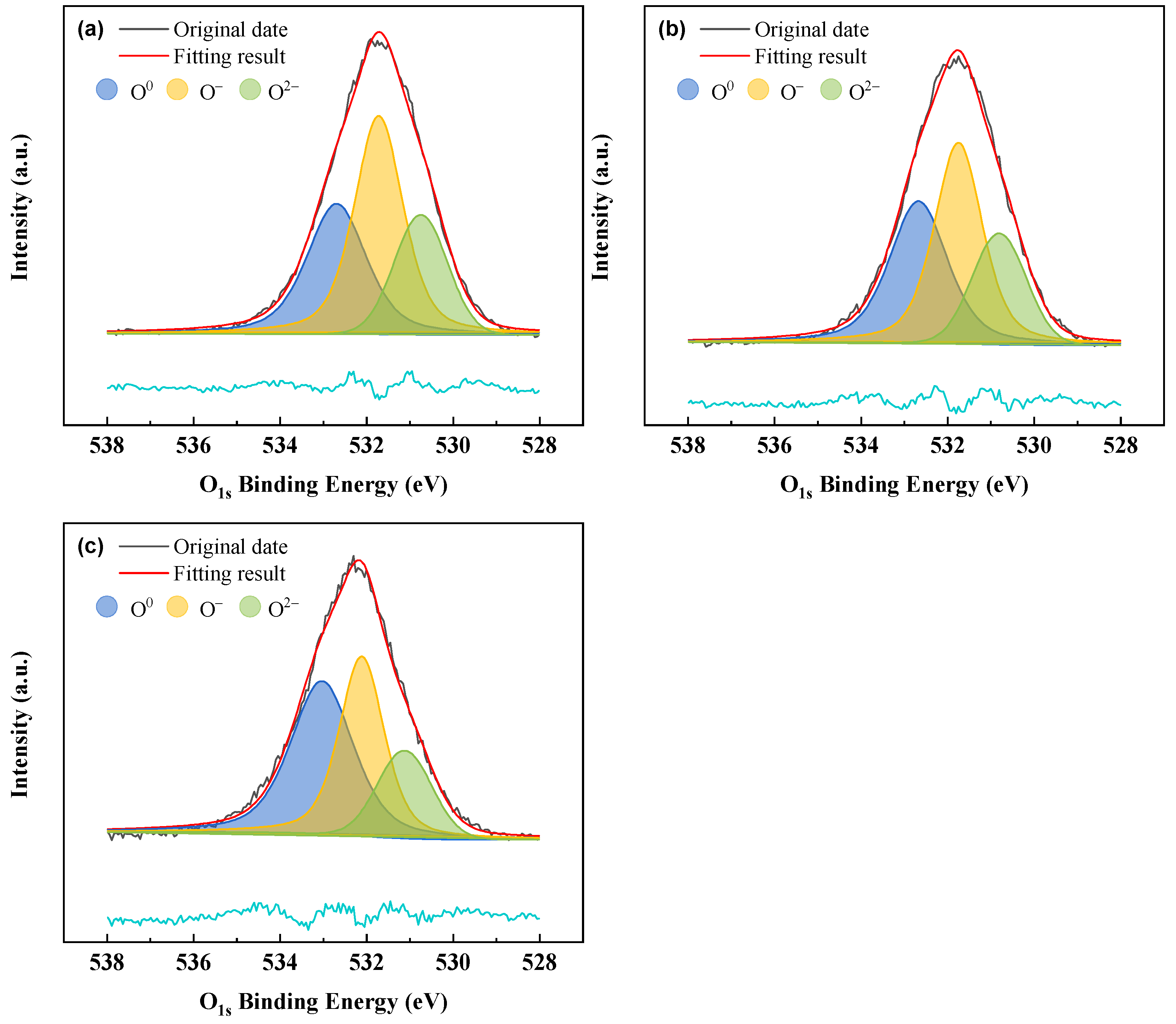

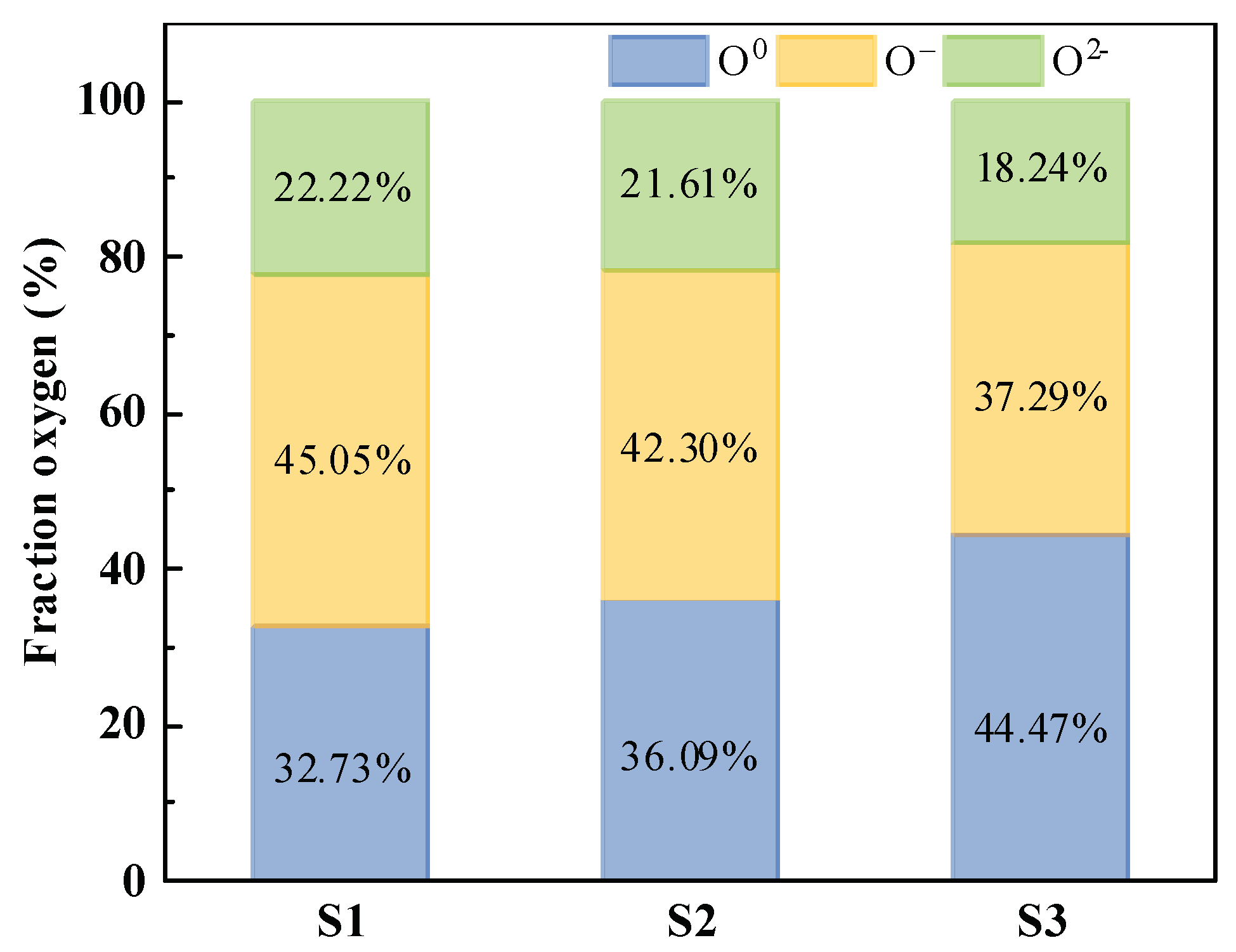

3.4.2. XPS Spectra Analysis

In order to delve deeper into the mechanism of viscosity effects on silicomanganese slag structure, the variation in the molar fraction of oxygen atoms (bridging oxygen (O

0), non-bridging oxygen (O

–), and free oxygen (O

2–)) was analyzed for different samples. Previous research by various scholars [

40,

41,

42] has indicated that the peaks located at binding energies of approximately 534 eV, 532 eV, and 531 eV in O

1s XPS spectra correspond to O

0, O

–, and O

2–, respectively.

Figure 11(a)-(c) depict the results of the deconvolution spectra of samples S1, S2, and S3 based on XPS PEAK4.1, respectively. The relative area fraction serves as a stable representation of the content of individual oxygen constituents, enabling the analysis of structural evolution using this method. The relative contents of each structural unit obtained from the sample deconvolution spectra are presented in

Figure 12. It is evident that the fraction of O

0 increases and O

– decreases after modification, with the change being more pronounced for S3 than for S2. This indicates an increase in the degree of slag polymerization, consistent with the FT-IR analysis. The degree of polymerization and viscosity of the slag are closely linked, and both FT-IR and XPS results confirm the increased viscosity of the modified samples S2 and S3.

The relationship correlating O

2–, O

–, and O

0 at high temperatures can be described by O

0 + O

2– ⇋ 2O

–, where O

2– is provided by basic oxides such as CaO, MgO, MnO, K

2O, and BaO in this system. However, the

R value decreased after modification, resulting in lower content of O

2–, leading to an increase in O

0 and complicating the network, thereby increasing the viscosity. Nevertheless, the increase in viscosity after modification is not conducive to the nucleation and growth of crystals, which contradicts the DSC results. On one hand, this contradiction is attributed to the presence of nucleating agents in the modifier, which facilitates the reduction of crystallization activation energy, promoting crystal nucleation and the generation of fine spinel phase. On the other hand, the lowered R value in the slag after modification increases O

0, thus augmenting the degree of polymerization and viscosity of the slag, which is not conducive to the precipitation of crystals.

Figure 11.

Deconvoluted results of O1S XPS spectra. (a) S1, (b) S2, (c) S3.

Figure 11.

Deconvoluted results of O1S XPS spectra. (a) S1, (b) S2, (c) S3.

Figure 12.

Relative fraction of O0, O–, and O2– in the silicomanganese slag S1, S2, and S3.

Figure 12.

Relative fraction of O0, O–, and O2– in the silicomanganese slag S1, S2, and S3.

4. Summary

The experiments involved the modification of silicomanganese slag by adding 10 mass% cold chromite and serpentine, and 20 mass% molten ferrochrome slag, resulting in samples named S2 and S3, respectively.

The main mineral phases of modified silicomanganese slag are augite and spinel-group minerals (galaxite (Mn2+, Mg)(Al, Cr3+, Fe3+)2O4) and normal spinel (Mg(Cr3+, Al)2O4)). The crystallization activation energies are 407.24 kJ mol−1 and 237.42 kJ mol−1 for S2 and S3, respectively. The precipitation of spinel group minerals was found in the quenched slag at 1300 ℃ and 1100 ℃, which plays a dual role, as a nucleation agent to dynamically promote the formation of augite, and increase of the proportion of SiO2 and polymerization of the [SiO4] structural unit in the residual liquid phase, further promoting the generation of augite in composition. The gradual precipitation of crystals effectively mitigates sudden viscosity fluctuations resulting from crystallization. The modified slag thereby demonstrates both superior crystallization ability and favorable fluidity.

The results indicate that the cast stone made from raw silicomanganese slag remains primarily amorphous phase and fractured after heat treatment. In contrast, the crystallization ability of the two modified slags has been enhanced, resulting in cast stone with overall good performance. Their physical properties, including flexural strength, bulk density, and water absorption, meet the requirements of the GB/T18601-2009 standard for “Natural Granite Building Panels” (i.e., flexural strength ≥ 8.3 MPa, bulk density ≥ 2.56 g·cm-3, water absorption ≤ 0.4%). Specifically, the flexural strengths are 37.50 MPa and 35.70 MPa, the bulk densities are 3.11 g·cm-3 and 3.09 g·cm-3, and the water absorption rates are 0.32% and 0.22%, respectively.

This demonstrates the feasibility of a simple and low-cost modification method using "molten silicomanganese slag + 10 mass% cold modifiers" or "molten silicomanganese slag + 20 mass% molten ferrochrome slag," relying on the self-induced heat of the molten silicomanganese slag.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The financial support from the Ulanqab Open Competition Mechanism Project (No. 2022JB002) is greatly acknowledged.

References

- Yang J., Li Y, Yang T.: Comparative of different modifiers on the crystallization properties of glass–ceramics derived from silicon manganese slag. Chinese Journal of Engineering. 45, 1918-1927 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Luiza F. d. L., Cláudio A. P., Janete E. Z., Robinson C. D. C.: Effect of iron on the microstructure of basalt glass-ceramics obtained by the petrurgic method. International Journal of Applied Ceramic Technology. 18, 1950-1959 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Choi M., Jung S.: Elucidation of the crystallisation mechanism of iron oxide-devoid BOF slag melt. Ironmaking & Steelmaking. 45, 441-446 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Cheng Z., Li Y., Huang Y.: Effects of different crystallization temperatures on temperature difference, crystallization and physical properties of silica manganese slag cast stone. Chinese Journal of Engineering. [CrossRef]

- Chen K., Li Y., Meng X., Meng L., Guo Z.: New integrated method to recover the TiO2 component and prepare glass-ceramics from molten itanium-bearing blast furnace slag. Ceramics International. 45, 24236-24243 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Zhao X., Li Y., Chen K., Guo Z.: Effects of high gravity on dissolution of solid modifiers in molten slag. Ceramics International. 48, 14360-14370 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Chen, K., Li, Y., Meng, L., Yi, Y., Guo, Z.: Preparation of Glass-Ceramic from Titanium-Bearing Blast Furnace Slag by “Petrurgic” Method. In: Sun, Z., et al. Energy Technology 2018. TMS 2018. The Minerals, Metals & Materials Series. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Yang T., Li Y., Zhao X., Yang J.: Preparation of densified glass-ceramics with less shrinkage cavities from molten copper slag by Petrurgic method. Ceramics International. 49, 20998-21007 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Luo Y., Wang F., Zhu H., Liao Q., Xu Y., Liu L.: Preparation and characterization of glass-ceramics with granite tailings and titanium-bearing blast furnace slags. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids. 582, 121463 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Dai W., Li Y., Cang D.: Effects of heat treatment process on the microstructure and properties of BOF slag based glass-ceramics. Chinese Journal of Engineering. 35, 1507-1512 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Liu X., Li B., Wu Y.: The pretreatment of non-ferrous metallurgical waste slag and its research progress in the preparation of glass-ceramics. Journal of Cleaner Production. 404, 136930 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Rawlings R.D., Wu JP, Boccaccini A.R.: Glass–ceramics: Their production from wastes—a review. J Mater Sci. 41, 733-761 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Guo Y., Du Y., Wang G., Xu Y., Zhang H., Deng L., Chen H., Zhao M.: The direct experimental observation and solidification mechanism of heavy metals in blast furnace slag glass-ceramics. International Journal of Applied Ceramic Technology. 21, 796-805 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Li Ba., Guo Y., Fang J.: Effect of crystallization temperature on glass-ceramics derived from tailings waste. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 838, 155503 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Liu W., Pang Z., Zheng J., Yin S., Zuo H.: The viscosity, crystallization behavior and glass-ceramics preparation of blast furnace slag: A review. Ceramics International. 50, 18090-18104 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Deng L., Jia R., Yun F., Zhang X., Li H., Zhang M., Jia X., Ren D., Li B.: Influence of Cr2O3 on the viscosity and crystallization behavior of glass ceramics based on blast furnace slag. Materials Chemistry and Physics. 240, 122212 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Cota T.G., Reis E.L., Lima R.M.F., Cipriano R.A.S.: Incorporation of waste from ferromanganese alloy manufacture and soapstone powder in red ceramic production. Applied Clay Science. 161, 274-281 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Buruiana D.L., Obreja C.-D., Herbei, E.E., Ghisman, V.: Re-Use of Silico-Manganese Slag. Sustainability. 13, 11771 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Shu Q., Li Q., Medeiros S.L.S., Klug J.L.: Development of non-reactive F-free mold fluxes for high aluminum steels: non-isothermal crystallization kinetics for devitrification. Metall. Mater. Trans. B. 51, 1169–1180 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Shi C., Li J., Cho J., Jiang F., Jung I.: Effect of SiO2 on the crystallization behaviors and in-mold performance of CaF2-CaO-Al2O3 slags for drawing-ingot-type electroslag remelting, Metall. Mater. Trans. B. 46, 2110–2120 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Shi C., Cho J., Zheng D., Li J.: Fluoride evaporation and crystallization behavior of CaF2-CaO-Al2O3-(TiO2) slag for electroslag remelting of Ti-containing steels. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 23, 627–636 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Zheng D., Shi C., Li J., Ju J.: Crystallization kinetics and structure of CaF2–CaO–Al2O3–MgO–TiO2 slag for electroslag remelting, ISIJ Int. 60, 492–498 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Shi C., Seo M., Wang H., Cho J., Kim S.: Crystallization kinetics and mechanism of CaO–Al2O3-based mold flux for casting high-aluminum TRIP steels, Metall. Mater. Trans. B. 46, 345–356 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Seo M., Shi C., Baek J., Cho J., Kim S.: Kinetics of isothermal melt crystallization in CaO-SiO2-CaF2-based mold fluxes, Metall. Mater. Trans. B. 46, 2374–2383 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Bai Z., Qiu G., Yue C., Guo M., Zhang M.: Crystallization kinetics of glass-ceramics prepared from high-carbon ferrochromium slag. Ceram. Int. 42, 19329–19335 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Sycheva G.A., Polyakova I.G., Kostyreva T.G.: Volumetric nucleation of crystals catalyzed by Cr2O3 in glass based on furnace slags, Glass. Phys. Chem. 42, 238–245 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Shelestak L.J., Chavez R.A., Mackenzie J.D.: Glasses and glass-ceramics from naturally occurring CaO-MgO-Al2O3-SiO2 materials (I) glass formation and properties. J. Non-Cryst. Solids. 27, 75–81 (1978). [CrossRef]

- Shi C., Shin S., Zheng D., Cho J., Li J.: Development of low-fluoride slag for electroslag remelting: role of Li2O on the viscosity and structure of the slag. Metall. Mater. Trans. B. 47, 3343–3349 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Zhang C., Cai D., Zhang J., Sasaki Y. Ostrovski O.: Effects of CaO/SiO2 ratio and Na2O content on melting properties and viscosity of SiO2-CaO-Al2O3-B2O3-Na2O mold fluxes. Metall. Mater. Trans. B. 48, 516–526 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Kim J., Sohn I.: Effect of SiO2/Al2O3 and TiO2/SiO2 ratios on the viscosity and structure of the TiO2–MnO–SiO2–Al2O3 welding flux system, ISIJ int. 54, 2050–2058 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Yu X., Wen G., Tang P., Wang H.: Investigation on viscosity of mould fluxes during continuous casting of aluminium containing TRIP steels. Ironmaking and Steelmaking. 36, 623-630 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Zheng H.W.: Effect of doping on the structure and properties of Li2O-Al2O3-SiO2 system[Dissertation], Wuhan University of Technology 2007 Wuhan.

- Kim G.H., Sohn I.: Effect of Al2O3 on the viscosity and structure of calcium silicate-based melts containing Na2O and CaF2. J. Non-Cryst. Solids. 358, 1530–1537 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Rezvani M., Farahinia L.: Structure and optical band gap study of transparent oxyfluoride glass-ceramics containing CaF2 nanocrystals. Mater. Des. 88, 252–257 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Shen Y.Y., Liu X.Y., Chen S.J., Wang Y.Y., Yan W., Li J.: Unveiling the effect of MnO/SiO2 ratios on the viscosity and structure of mold fluxes for high-Mn cryogenic steels. Ceram. Int. 49, 29308-29316 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Kim G.H., Kim C.S., Sohn I.: Viscous behavior of alumina rich calcium-silicate based mold fluxes and its correlation to the melt structure. ISIJ Int. 53, 170–176 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Liao J., Zhang Y., Sridhar S., Wang X., Zhang Z.: Effect of Al2O3/SiO2 ratio on the viscosity and structure of slags. ISIJ Int. 52, 753–758 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Wang Z., Shu Q., Sridhar S., Zhang M., Guo M., Zhang Z.: Effect of P2O5 and FetO on the viscosity and slag structure in steelmaking slags. Metall. Mater. Trans. B. 46, 758–765 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Kim J.R., Lee Y.S., Min D.J., Jung S.M., Yi S.H.: Influence of MgO and Al2O3 contents on viscosity of blast furnace type slags containing FeO. ISIJ Int. 44, 1291–1297 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Ko K.Y., Park J.H.: Effect of CaF2 addition on the viscosity and structure of CaO-SiO2-MnO slags. ISIJ Int. 53, 958-965 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Nesbitt H.W., Bancroft G.M., Henderson G.S., Ho R., Dalby K.N., Huang Y., Yan Z.: Bridging, non-bridging and free (O2-) oxygen in Na2O-SiO2 glasses: An X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopic (XPS) and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) study. J. Non-Cryst. Solids. 357, 170-180 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Hayashi M., Nabeshima N., Fukuyama H., Nagata K.: Effect of fluorine on silicate network for CaO-CaF2-SiO2 and CaO-CaF2-SiO2-FeOx glasses. ISIJ Int. 42, 352-358 (2002). [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Mineral compositions of silicomanganese slag, chromite, serpentine and ferrochrome slag.

Figure 1.

Mineral compositions of silicomanganese slag, chromite, serpentine and ferrochrome slag.

Figure 2.

XRD patterns of as-quenched silicomanganese slag samples.

Figure 2.

XRD patterns of as-quenched silicomanganese slag samples.

Figure 3.

Preparation steps of cast stone from silicomanganese slag.

Figure 3.

Preparation steps of cast stone from silicomanganese slag.

Figure 4.

Photos of laboratory and factory prepared (middle position size: 1150 × 350 × 500 mm) cast stone samples.

Figure 4.

Photos of laboratory and factory prepared (middle position size: 1150 × 350 × 500 mm) cast stone samples.

Figure 5.

DSC curves for S1 (a), S2 (b), and S3 (c) at different cooling rates.

Figure 5.

DSC curves for S1 (a), S2 (b), and S3 (c) at different cooling rates.

Figure 6.

The plot of ln(Tp2/β) versus 1/Tp. r is the Pearson correlation coefficient, the lines represent linear fitting results.

Figure 6.

The plot of ln(Tp2/β) versus 1/Tp. r is the Pearson correlation coefficient, the lines represent linear fitting results.

Figure 7.

XRD patterns of slag quenched at different temperature. (a) 1000 ℃, (b) 1100 ℃, (c) 1300 ℃.

Figure 7.

XRD patterns of slag quenched at different temperature. (a) 1000 ℃, (b) 1100 ℃, (c) 1300 ℃.

Figure 8.

Viscosity of silicomanganese slag with different modifiers at different temperatures.

Figure 8.

Viscosity of silicomanganese slag with different modifiers at different temperatures.

Figure 9.

Relationship between lnη and 1/T for silicomanganese slag with various modifiers contents.

Figure 9.

Relationship between lnη and 1/T for silicomanganese slag with various modifiers contents.

Figure 10.

FT-IR spectroscopy of the mold fluxes.

Figure 10.

FT-IR spectroscopy of the mold fluxes.

Table 1.

Chemical compositions of the raw material (mass%).

Table 1.

Chemical compositions of the raw material (mass%).

| Raw Material |

CaO |

SiO2

|

Al2O3

|

MgO |

MnO |

Fe2O3

|

K2O |

Cr2O3

|

BaO |

Total |

| Silicomanganese slag |

27.27 |

38.40 |

13.24 |

3.60 |

7.92 |

2.27 |

1.60 |

0.26 |

2.49 |

97.05 |

| Chromite |

1.04 |

8.30 |

10.25 |

9.84 |

0.56 |

26.40 |

0.06 |

40.50 |

0.00 |

96.95 |

| Serpentine |

1.53 |

43.29 |

2.01 |

39.31 |

0.22 |

11.05 |

0.06 |

0.73 |

0.00 |

98.20 |

| Ferrochrome slag |

4.90 |

28.80 |

23.20 |

26.10 |

0.60 |

4.23 |

0.12 |

9.73 |

— |

97.68 |

Table 2.

Chemical composition of mixed silicomanganese slag (mass%).

Table 2.

Chemical composition of mixed silicomanganese slag (mass%).

| Sample No. |

CaO |

SiO2

|

Al2O3

|

MgO |

MnO |

Fe2O3

|

K2O |

Cr2O3

|

BaO |

R(mass%CaO/mass%SiO2)

|

| S1 |

27.27 |

38.40 |

13.24 |

3.60 |

7.92 |

2.27 |

1.60 |

0.26 |

2.49 |

0.71 |

| S2 |

25.18 |

36.69 |

12.84 |

4.69 |

7.32 |

3.89 |

1.48 |

2.68 |

2.29 |

0.69 |

| S3 |

22.80 |

36.48 |

15.23 |

8.10 |

6.46 |

2.66 |

1.30 |

2.15 |

1.99 |

0.63 |

Table 3.

Mechanical properties of samples and national standard requirements.

Table 3.

Mechanical properties of samples and national standard requirements.

| Sample/national standard |

Flexural strength /Mpa |

Bulk density/(g/cm-3) |

Water absorption/% |

| S1 |

— |

3.03 |

0.08 |

| S2 |

37.50 |

3.11 |

0.32 |

| S3 |

35.70 |

3.09 |

0.22 |

Natural granite building slabs

(GB/T 18601-2009) |

≥8.3 |

≥2.56 |

≤0.4 |

Table 4.

Glass crystallization temperature (Tp) and FWHM of exothermic peak (ΔTf) of samples at different cooling rates.

Table 4.

Glass crystallization temperature (Tp) and FWHM of exothermic peak (ΔTf) of samples at different cooling rates.

| Cooling rate β (℃·min–1) |

Tp (℃) |

| S1 |

S2 |

S3 |

| 10 |

– |

1081 |

1114 |

| 20 |

– |

1073 |

1093 |

| 30 |

– |

1045 |

1050 |

Table 5.

Activation energy for viscous flow of different modified silicomanganese slag.

Table 5.

Activation energy for viscous flow of different modified silicomanganese slag.

| Slag No. |

S1 |

S2 |

S3 |

| Activation energy for viscous flow (kJ mol–1) |

30.38 ± 8.34 |

43.70 ± 5.14 |

74.93 ± 8.07 |

Table 6.

Assignments of FT-IR bands in spectra of studied mold fluxes.

Table 6.

Assignments of FT-IR bands in spectra of studied mold fluxes.

| Wavenumber/cm–1

|

Assignment |

Refs. |

| 600–800 |

[AlO4]-tetrahedral stretching vibration |

[35,36,37] |

| 800–1200 |

[SiO4]-tetrahedral stretching vibration |

[35,38,39] |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).