1. Introduction

The increasing demand for sustainable practices in the food and dietary supplement industry has drawn attention to food industry residues such as grape pomace, which are a rich source of various bioactive compounds, with a focus on phenolic compounds [

1,

2]. Phenolic compounds possess strong antioxidant, antimicrobial and antitumor properties, making them valuable for functional food formulations and health-related applications [

3,

4,

5,

6]. However, their inherent instability under processing, storage and digestion conditions poses a major challenge, so effective stabilization strategies are required to maintain their efficacy and improve their bioaccessibility and thus bioavailability [

7,

8]. Bioavailability refers to the proportion of a bioactive substance that is absorbed after ingestion and is available for biological activity at the target site. For a compound to reach this stage, however, it must first be bioaccessible, i.e. it must be released from the food matrix during digestion and be available for absorption in the gastrointestinal tract. Even if a compound is absorbed, its bioactivity, i.e. its ability to achieve the desired physiological or biochemical effect, depends on its stability, its interaction with metabolic pathways and its distribution in the body [

9]. Phenolic compounds are challenging because their complex chemical structure, but they are easily broken down in the acidic and enzymatic conditions found in gastric phase of digestion, reducing their functional effects such as antioxidant properties [

10,

11,

12].

Encapsulation technologies such as spray-drying offer a promising solution to these challenges by embedding phenolic compounds in protective matrices [

13]. This method not only stabilizes phenolics during processing, but also controls their release, which can improve bioavailability [

14,

15]. To optimize this process, the selection of suitable encapsulation materials is crucial, as their chemical properties significantly influence the protective function and release behaviour of the encapsulated compounds. In this study, three biopolymers — sodium alginate (SA), gum Arabic (GA) and gelatin (GEL) — were selected based on their complementary properties. SA, a natural polysaccharide derived from brown algae, forms a stable matrix due to its gelling ability, providing moderate protection for phenolic compounds [

16]. However, its limited emulsifying properties can lead to lower encapsulation efficiency (

EE), which is why combinations with other biopolymers are desirable [

17]. GA, a plant-derived polysaccharide, complements sodium alginate by providing excellent emulsifying and film-forming properties, creating a robust encapsulation matrix that minimizes aggregation and can improve the retention of phenols during spray drying [

18]. GEL, a protein-based biopolymer, further improves the encapsulation system by exhibiting pH-sensitive swelling behaviour [

19]. This property makes gelatin particularly effective for targeted release under intestinal conditions, where absorption predominantly occurs [

8,

20]. In addition, the helical protein structure of gelatin enables strong interactions with phenolic compounds, which improves their stability and controlled release [

21].

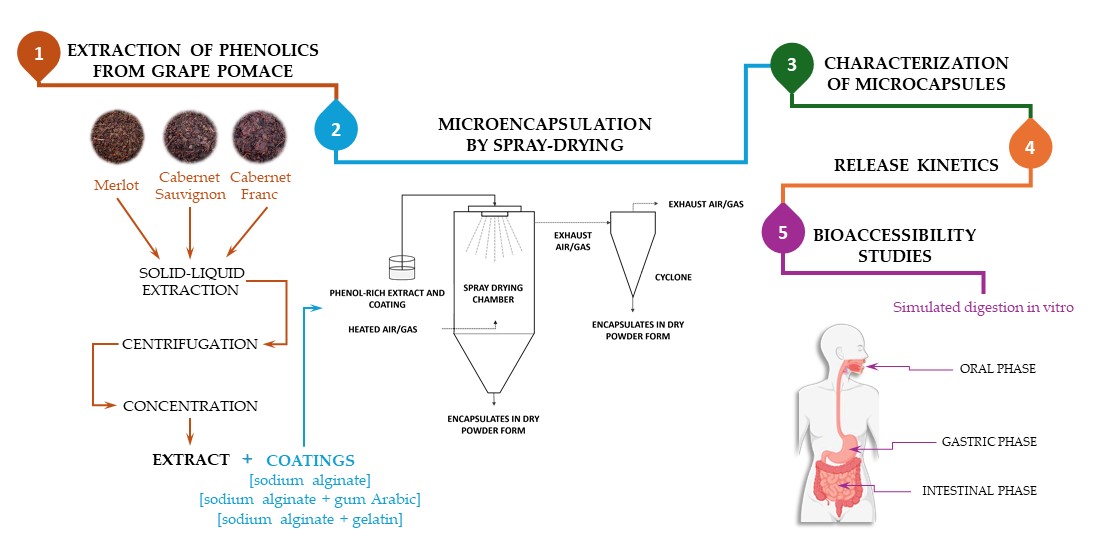

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the EE, structural properties of microcapsules, in vitro release dynamics and bioaccessibility of phenolic compounds from encapsulated grape pomace extracts by spray-drying with SA and SA-GA and SA-GEL coatings. By studying the physicochemical properties and the digestion and release profiles of these encapsulated systems, we aim to determine the most effective formulation for the protection and release of phenolic compounds.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Encapsulation Efficiency

Figure 1 shows the

EE of spray-drying for three grape pomace extracts and three coatings tested.

The lowest

EE values were recorded when only SA was used, with results below 70% for all varieties. The limited effectiveness of SA in this context could be related to a lower ability to form stable protective layers, leading to greater losses of phenolic compounds during the spray-drying process. These findings support earlier research on other encapsulation techniques, such as ionic gelation and freeze-drying, and imply that SA must be mixed with other polymers to increase the effectiveness of bioactive component encapsulation [

22,

23].

The coatings used had a statistically significant influence on the

EE. For all samples, the highest

EE (95.90 – 98.01%) was achieved with the SA-GEL coating. This excellent performance can be attributed to the improved protective properties and structural stability resulting from the SA-GEL coating. Song et al. [

24] and Cortés-Morales et al. [

25] have described the synergistic effects of combining proteins and polysaccharides as coatings leading to higher

EE due to the complementary properties, while proteins stabilize and form films, polysaccharides form gels and provide protection. Conversely, the

EE values of SA-GA ranged from 80.58% to 88.35% (

Figure 1). GA is a highly branched polysaccharide that improves emulsion stability and provides moderate protection from environmental conditions [

26,

27]. Its

EE was lower than that of the SA-GEL combination, most likely due to fact that its gel network was weaker. Nevertheless, the SA-GA coating significantly improved the

EE compared to SA alone, suggesting that it could be a promising encapsulation coating combination in situations where protein-based materials are undesirable.

2.2. Physicochemical Properties of Microcapsules

Microcapsules were produced by spray-drying grape pomace extract, rich in phenolic compounds, with a variety of alginate-based coatings. Physicochemical characterization of the microcapsules was performed by morphology analysis, X-ray powder diffraction (XRPD) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC).

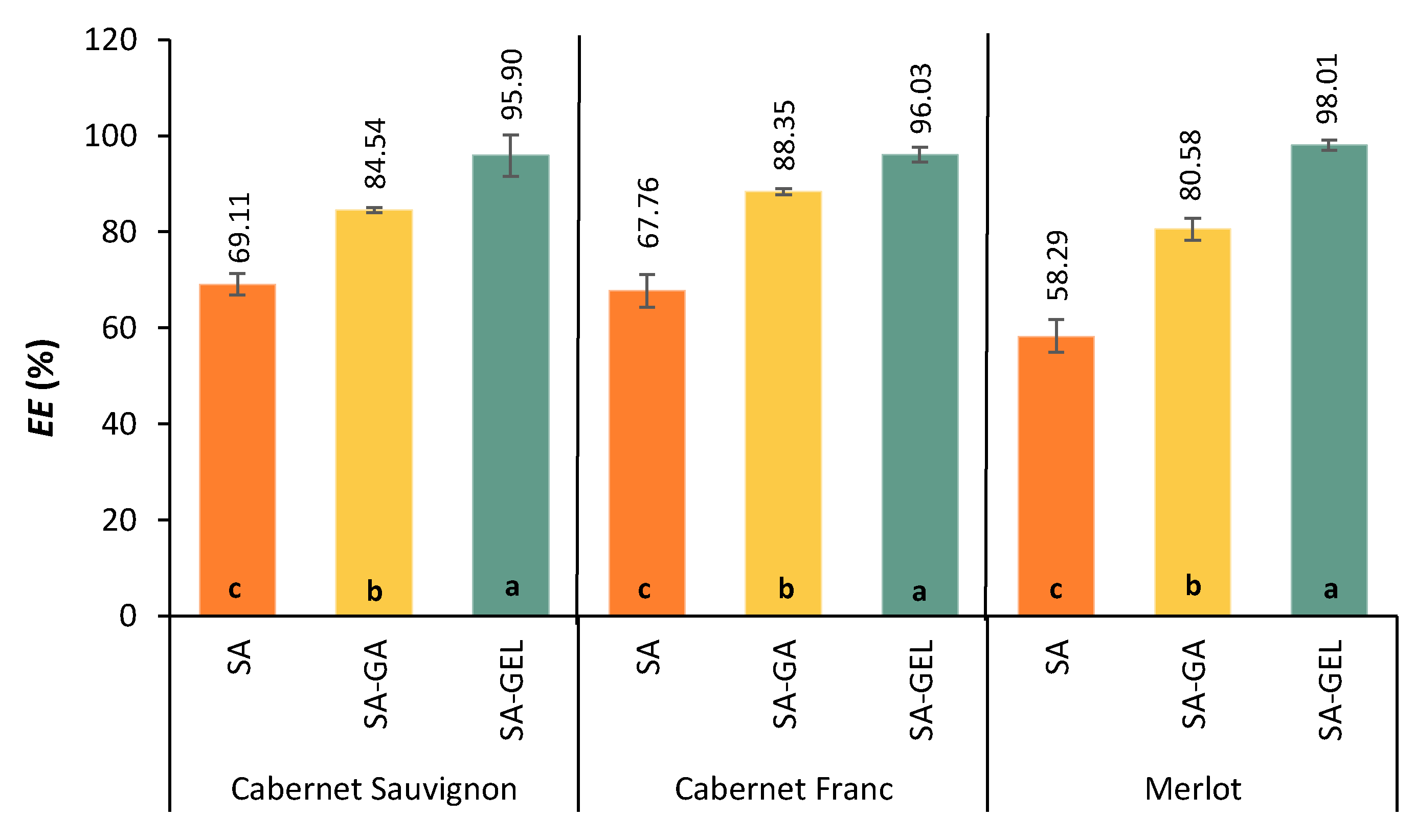

2.2.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy of Microcapsules

The morphology of the microcapsules containing different pomace extracts was explored by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The SEM images (

Figure 2) provide an insight into the structural properties of the microcapsules.

While spray-dried, SA microcapsules show mostly spherical shape, their closer inspection discloses size variation and some irregularities probably as case of aggregation of the particles by the drying process. The majority of particles have been generally smooth in surface texture with slight indentations or wrinkles, especially observed in Cabernet Sauvignon SA microcapsules (

Figure 2 SA(ii)), most likely due to moisture loss during encapsulation or process conditions. Further, some coalescence can be observed between the SA microcapsules of Cabernet Franc and Merlot extracts (

Figure 2), indicating also that the coating of SA has a limited effectiveness in preventing fusion. This phenomenon has also been observed by other studies, such as by Tonon et al. [

28] and Botrel et al. [

29]. When SA combined with GA, Cabernet Sauvignon SA-GA microcapsules resulted in more uniform shape. The surface of those particles can be more rugged (as seen for Merlot microcapsules in

Figure 2 SA-GA(ii)), owed to the properties of GA, known for its emulsifying and film-forming abilities that enhance particle stability, reducing coalescence. The combination SA-–GA provides an encapsulation matrix that is much more cohesive and hence allows better separation between particles; overall, it allows more effective encapsulation. In contrast, SA combined with gelatin, SA-GEL, gives microcapsules that maintain a generally spherical form but with some irregularities seen in Cabernet Sauvignon microcapsules (

Figure 2 SA-GEL(ii)). These irregularities could be due to lower rigidity of GEL compared to GA, leading to increased surface variability. Nevertheless, GEL may offer additional benefits such as improvement in bioavailability and controlled release of the encapsulated substances [

30].

2.2.2. Thermal and Structural Analysis of Coatings and Microcapsules

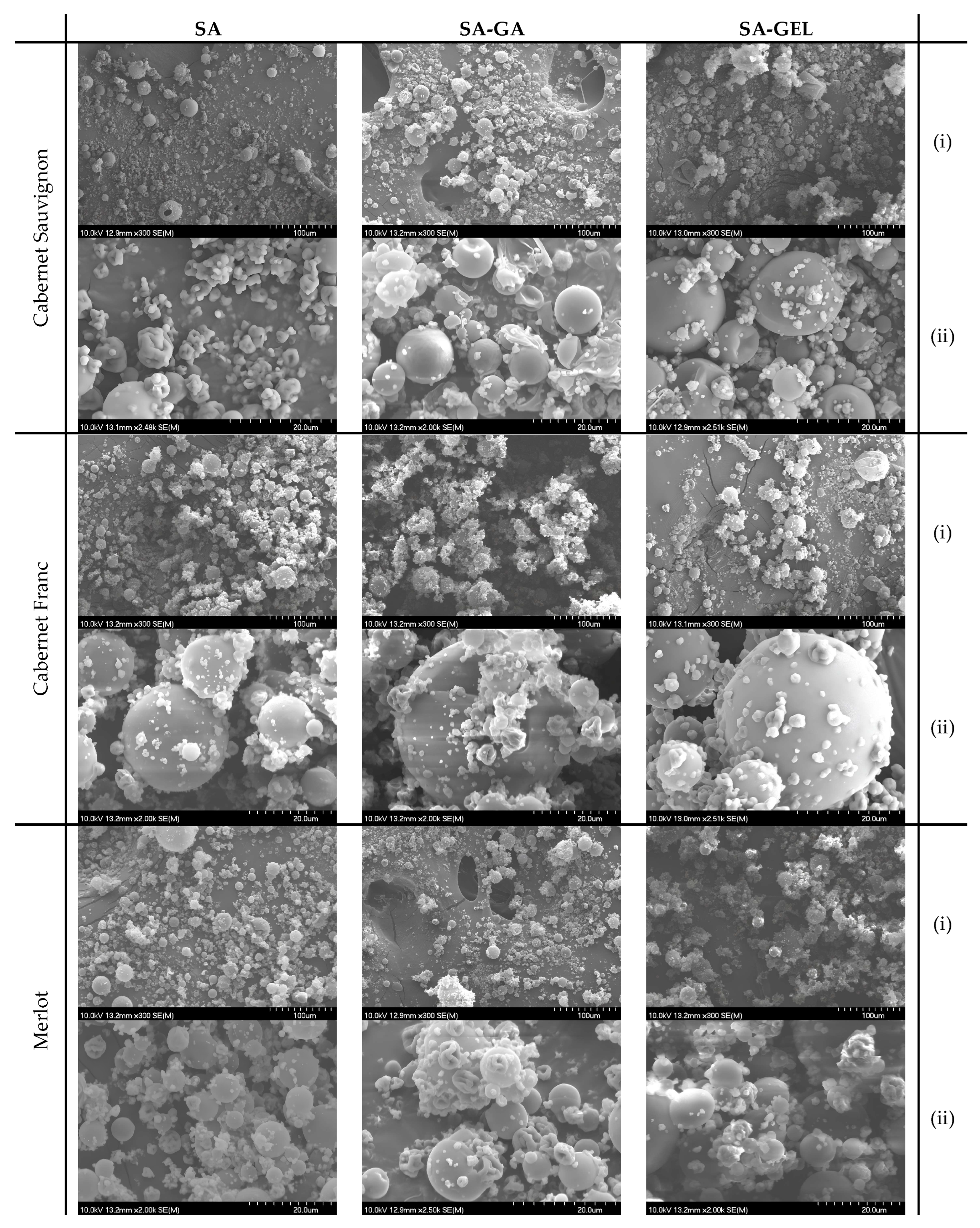

The various coatings used (SA-0, GA-0, GEL-0) as well as spray-dried microcapsules produced were analysed for their crystalline and amorphous state using XRPD and DSC.

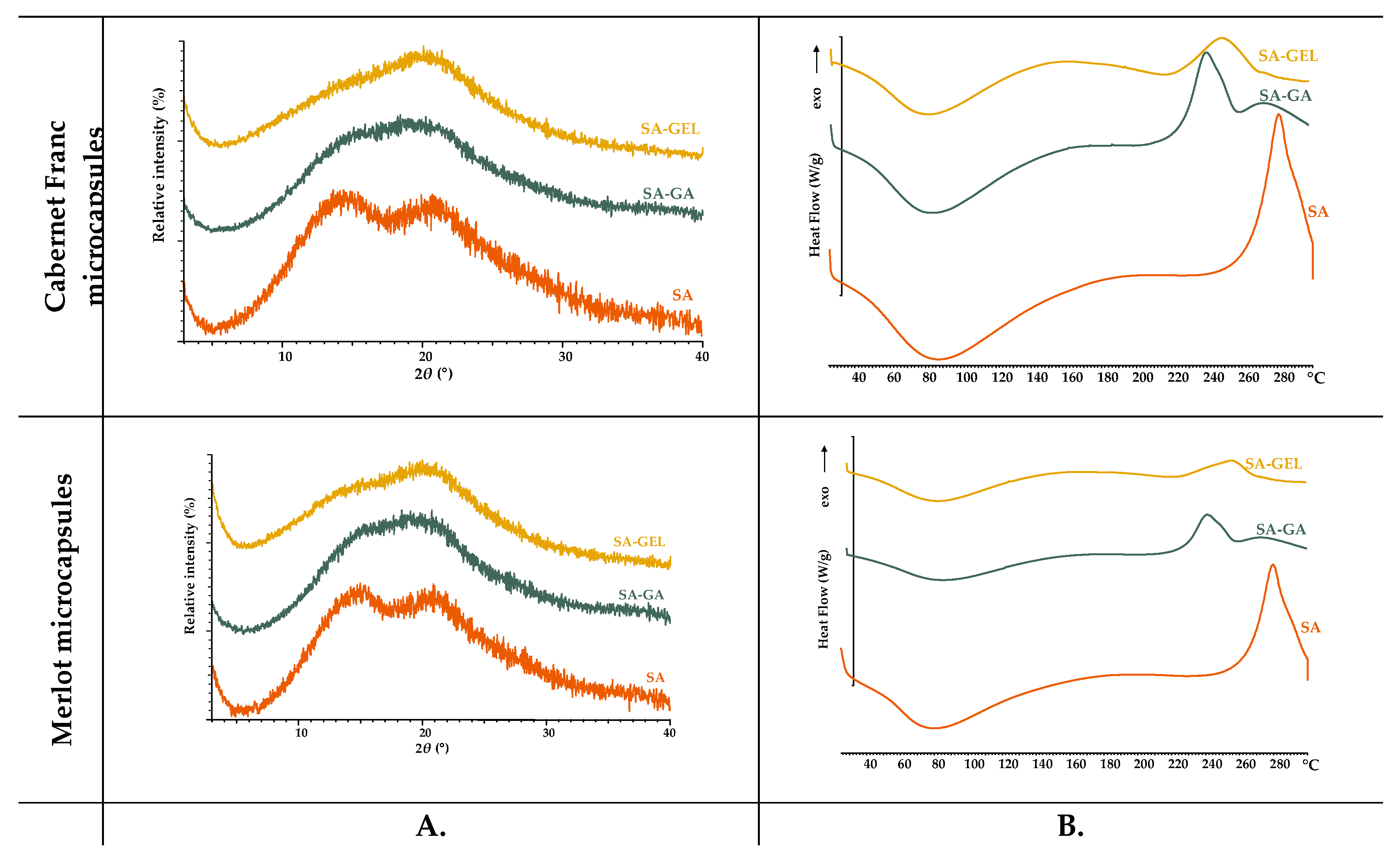

The XRPD analysis revealed that all coatings investigated are amorphous, as shown in

Figure 3A. While SA-0 shows a clearly defined peak, GA-0 and GEL-0 show broader and less pronounced peaks, all of which are characteristic of an amorphous state. As for the thermal behaviour observed by DSC, both SA-0 and GA-0 exhibit a broad endothermic peak in the low to medium temperature range (60–120 °C), which is related to dehydration. On the other hand, consistent with the findings of Guan and Zhong [

31], GA-0 demonstrated higher thermal stability as its thermogram does not display exothermic event, implying it can endure higher temperatures without undergoing degradation. In contrast, the observed degradation of SA-0 at high temperatures, specifically at 240 – 260 °C (

Figure 3B), aligns with the results of Barra et al. [

32]. The water loss of GEL-0 occurs in a slightly broader temperature range (50 – 176 °C), and followed by a pronounced endothermic peak between 230 °C and 250 °C, which represents the denaturation or melting of the helical structure. Dai et al. [

33] published that this transition reflects the structural stability and unique ordering due to the helical conformation. From the DSC results, the coatings tested in the current study have an amorphous structure, which confirms the XRPD results obtained above.

Microcapsules coated with SA-GA and SA-GEL show more similar diffraction patterns in all samples than those coated with SA. The peak intensities of all microcapsules vary slightly between 10° and 30°, which is probably due to slight interactions between the extract and the encapsulation matrix. The DSC thermograms (

Figure 3B) show a dehydration peak, as seen in the thermograms of the coatings used, followed by the thermal transitions. Sharp transitions at higher temperatures could indicate interactions between the coatings and the phenolic compounds from the grape pomace extracts. It appears that simpler polysaccharide coatings in microcapsules such as SA have sharper transitions in DSC due to more thermal degradation, while broader transitions are observed in SA-GA and SA-GEL microcapsules with a slight increase in thermal stability compared to SA microcapsules. Barra et al. [

32] interpret this as evidence of either slow degradation or more complex interactions with encapsulated material.

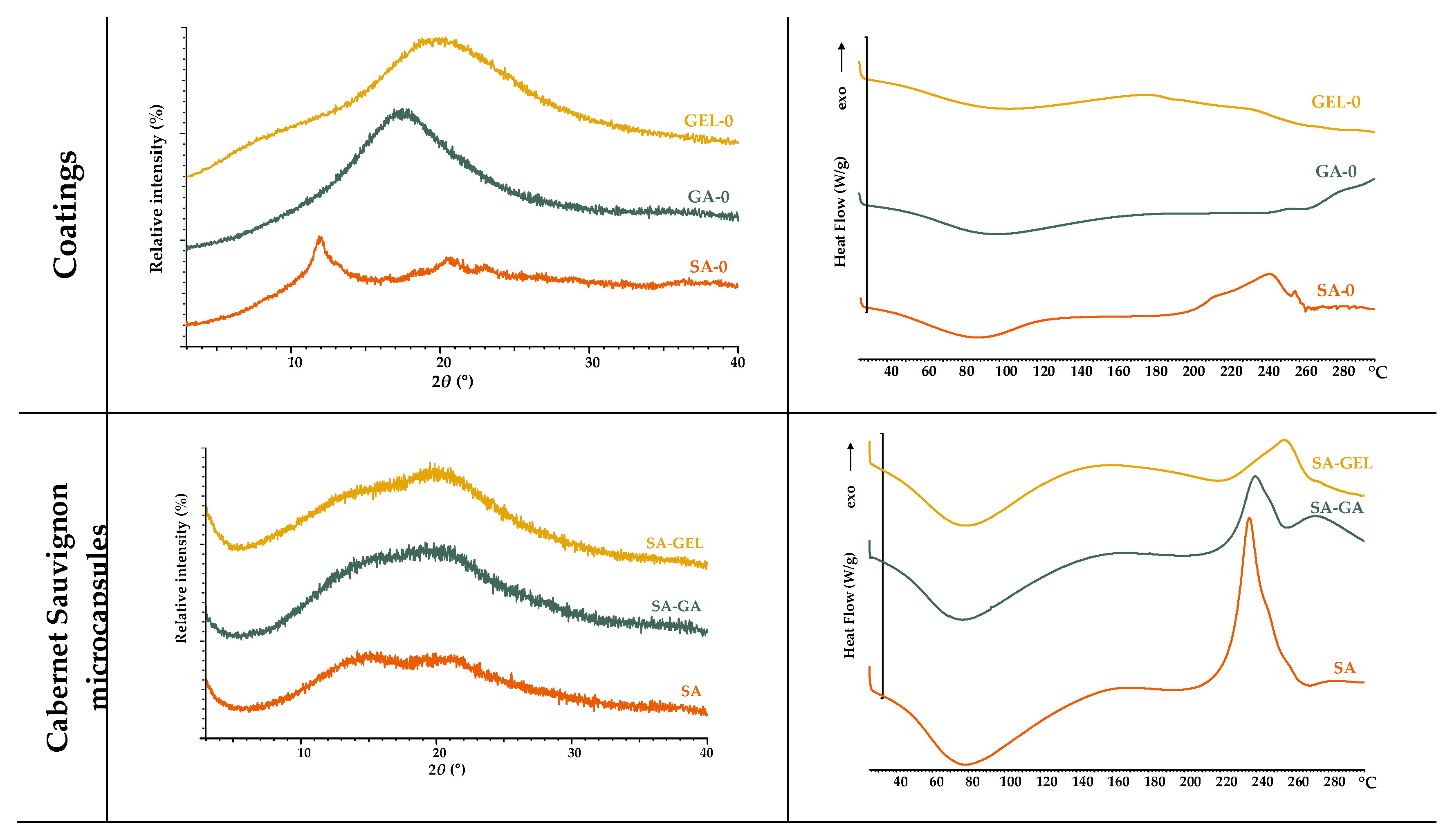

2.3. Enzyme-Free Release Study of Phenolic Compounds

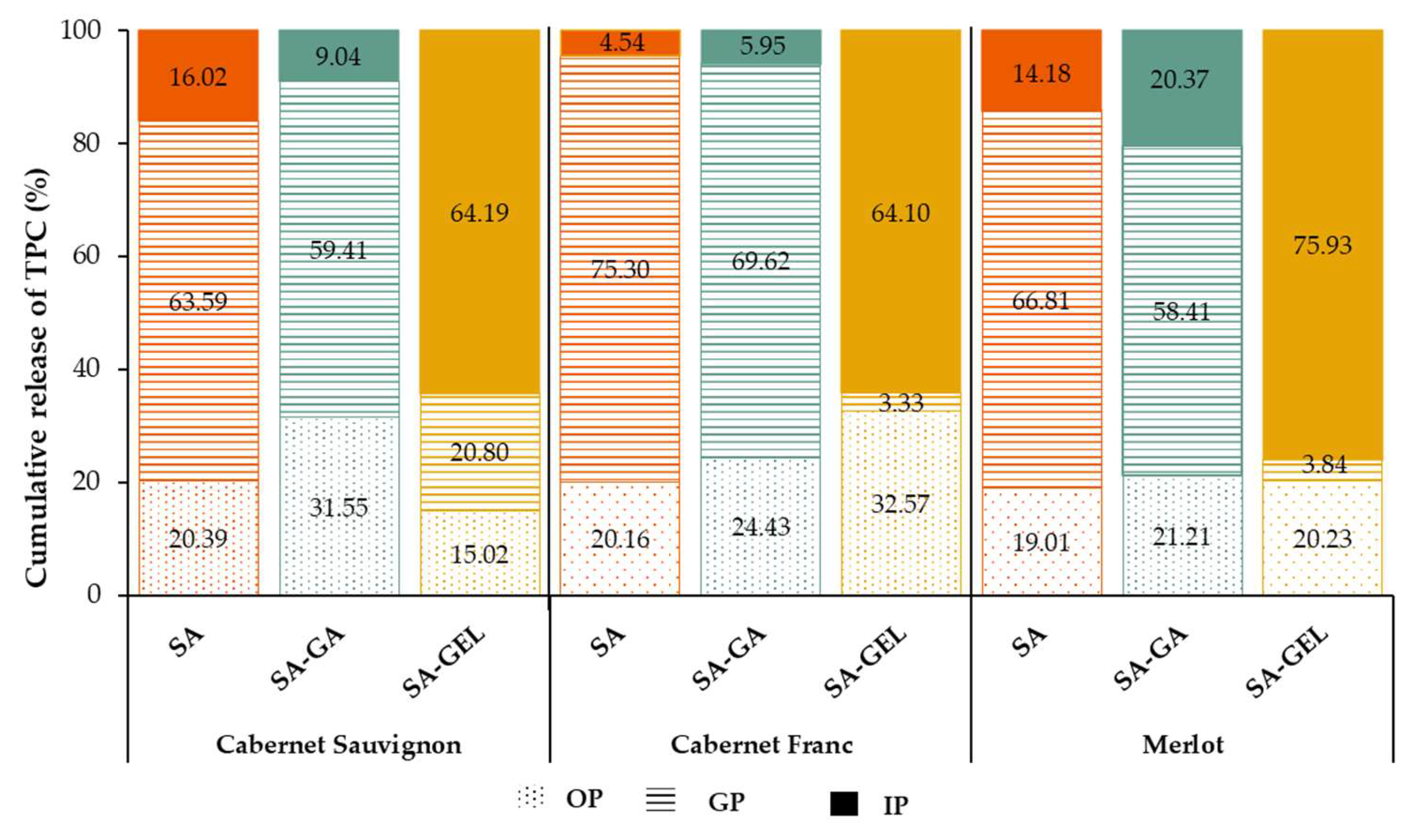

The release of total phenolic compounds (TPC) from the microcapsules under conditions mimicking the human gastrointestinal system through three digestive phases: oral (OP), gastric (GP) and intestinal (IP) phase using appropriate electrolyte solutions without digestive enzymes are shown in

Figures S1 and 4. Monitoring of TPC release under the above conditions lasted a total of 243 minutes, with OP lasting 3 minutes, after which GP was continued for 120 minutes and IP for a further 120 minutes.

The cumulative TPC release profile of microcapsules containing grape pomace extracts shows a clear release pattern across all digestive phases, as shown in

Figures S1 and 4. For microcapsules coated only with SA, TPC release starts in the OP with values between 10.42 and 13.35 mg

GAE/g

MC, indicating a rapid initial release (

Figure S1). This initial release could be due to phenolics absorbed at the surface, which are not well incorporated into the microcapsule matrix and are therefore the first to be released. During GP, SA microcapsules show an increase, reaching cumulative release values between 18.31 – 42.93 mg

GAE/g

MC for Cabernet Sauvignon, 25.31 – 63.22 mg

GAE/g

MC for Cabernet Franc and 23.16 – 55.73 mg

GAE/g

MC for Merlot microcapsules (

Figure S1). However, the release into IP is minimal, with the cumulative TPC increasing only slightly to about 51.12 – 66.23 mg

GAE/g

MC, suggesting a moderate role of SA in protecting TPC in early digestion. This is best illustrated in

Figure 4, where it can be seen that the highest release of TPC occurred in the GP (63.59 – 75.30%), where the coating should provide the greatest protection.

For all SA-GA microcapsules, the release in the OP is similar, with cumulative TPC values ranging from 11.00 to 13.61 mg

GAE/g

MC (

Figure S1). In the GP phase, the release is more substantial, reaching a peak value of 38.11 – 52.39 mg

GAE/g

MC (

Figure S1) or 58.41 – 69.62% (

Figure 4). The moderate release then continues in the IP phase, where the TPC values at the end of the IP phase are 38.93 – 55.71 mg

GAE/g

MC. Both SA and SA-GA follow a comparable release trend, but SA-GA provides slightly more protection, probably due to the additional stabilizing effects of gum Arabic. This makes SA-GA more effective in maintaining TPC stability in the early stages of digestion, especially compared to SA.

In contrast, the SA-GEL microcapsules show a very phase-specific release pattern, which distinguishes them from the SA and SA-GA coatings. During the OP, the release of TPC is minimal, with values between 4.74 – 12.89 mg

GAE/g

MC (

Figure S1). This initial retention of TPC is likely related to the minimal presence of surface phenolic compounds (SPC) in the SA-GEL microcapsules compared to the SA and SA-GA microcapsules (data not shown), which is consistent with the observed lower initial release in the oral environment. As digestion progresses to GP, TPC release from the SA-GEL microcapsules increases, reaching values between 7.33 – 11.29 mg

GAE/g

MC for Cabernet Sauvignon, 10.05 – 14.21 mg

GAE/g

MC for Cabernet Franc and 5.38 – 8.36 mg

GAE/g

MC for Merlot microcapsules (

Figure S1), corresponding to 3.33 – 20.80% of TPC (

Figure 4). The release of TPC is sustained in GP, suggesting that the SA-GEL combination retains the protective capacity for TPC in the stomach as in the mouth, preventing rapid degradation or release and allowing gradual diffusion of TPC from the microcapsules. Upon transition to IP, the SA-GEL microcapsules show a significant increase in TPC release, with cumulative values increasing to 31.53 – 39.58 mg

GAE/g

MC (

Figure S1), i.e. 64.10 – 75.93% (

Figure 4). This significant release in the IP shows that the SA-GEL coating is highly responsive to the pH conditions prevailing in the intestine. The gelatin in the coating likely swells or partially dissolves under the neutral to slightly basic pH in the intestinal phase, significantly increasing the diffusion and release of TPC. This behaviour reflects the pH-sensitive properties of gelatin, which can swell and become more permeable under intestinal conditions [

34], facilitating the targeted release of TPC at the preferred absorption site.

The release kinetics of TPC from microcapsules were evaluated using different mathematical models: first-order model, Higuchi model, Hixson-Crowell model and Korsmeyer-Peppas model (

Figure S2).

Table 1 summarizes the model parameters (

k values and the diffusion exponent

n for the Korsmeyer-Peppas model) and the statistical criteria used to evaluate the suitability of the model for data approximation. Of the statistical parameters, the R

2adj – adjusted coefficient of determination was the leading parameter in selecting the most appropriate model.

Table 1 shows that the Korsmeyer-Peppas empirical model best describes the release kinetics of TPC from SA and SA-GA microcapsules for Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot extracts (R

2adj > 0.91), as it is flexible enough to describe complex release behaviour as described in numerous articles such as Korsmeyer et al. [

35], Costa and Sousa Lobo [

36] and Siepmann and Siepmann [

37]. However, considering the graphical representation (

Figure S2), the fractional release of TPC from these microcapsules is better described by a first-order model. Therefore, the first order model is a mechanistic model and reflects the observed release kinetics more accurately. Nevertheless, the values of the diffusion exponent

n obtained for SA and SA-GA microcapsules (≤ 0.45) indicates that Fick's diffusion is the primary release mechanism (

Table 1). For Cabernet Franc, the first order model yielded the highest R

2adj of 0.937 for SA and 0.916 for SA-GA microcapsules, which is consistent with the plot in

Figure S2 and generally indicates that this model well characterizes the release kinetics for all SA and SA-GA microcapsules.

It can be seen from

Figure S2 that the release profile of the SA-GEL microcapsule was different from that of the SA and SA-GA microcapsules and cannot be fully described by any of tested models, although the Higuchi model provides the best statistical parameters to approximate the data (R

2adj between 0.801 and 0.852) (

Table 1). In this case, three phases of phenol release are observed, the first phase with a tendency to increase and then decrease, the second steady-state release in the GP followed by a gradual increase in the small intestine. This trend indicates that the release of phenolic compounds from SA-GEL microcapsules was most sensitive to the pH environment in which the release took place.

2.4. Bioaccessibility of Phenolic Compounds

Simulated digestion in vitro with digestive enzymes mimicking the human upper digestive system was performed with non-encapsulated grape pomace extracts of Cabernet Sauvignon (CS), Cabernet Franc (CF) and Merlot (M), i.e. control samples (C

CS; C

CF; C

M) and microencapsulated extracts (SA; SA-GA; SA-GEL). To assess the phenolic compounds bioaccessibility, the digestion was carried out in the OP, GP, and IP phases. The content of the individual phenolic compounds of the control samples before the simulation digestion in vitro is shown in

Tables S1–S3. The detailed chemical composition of these extracts was analysed and previously published study by Martinović et al. [

23].

During the simulated digestion, samples were taken at a certain period of time (e.g. OP3, GP123 and IP243; where the numerical index indicates the duration of digestion in minutes). These samples were analysed for TPC, total flavonoids content (TFC) and total proanthocyanidins content (TPA) as well as for the content of individual phenolic compounds such as phenolic acids, stilbenes, flavanols, flavonols and anthocyanins. The aim was to evaluate the effects of the coatings used on the release and bioaccessibility index (BI) of phenolics encapsulated by spray-drying (Figures 5D–7D). Equation (2) was used to determine the BI based on the amount of phenolic compound in the tested sample before digestion (BD) and after IP.

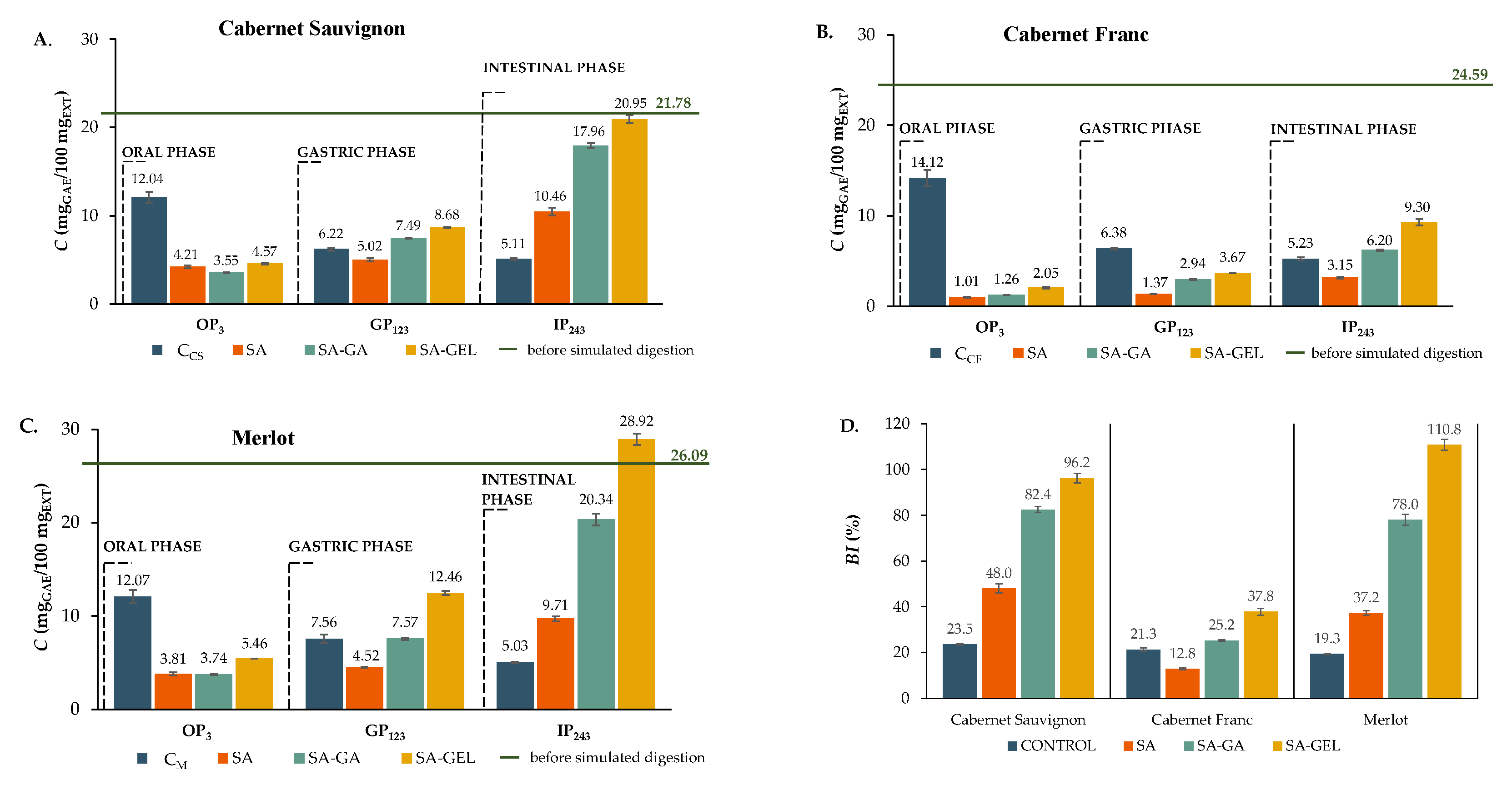

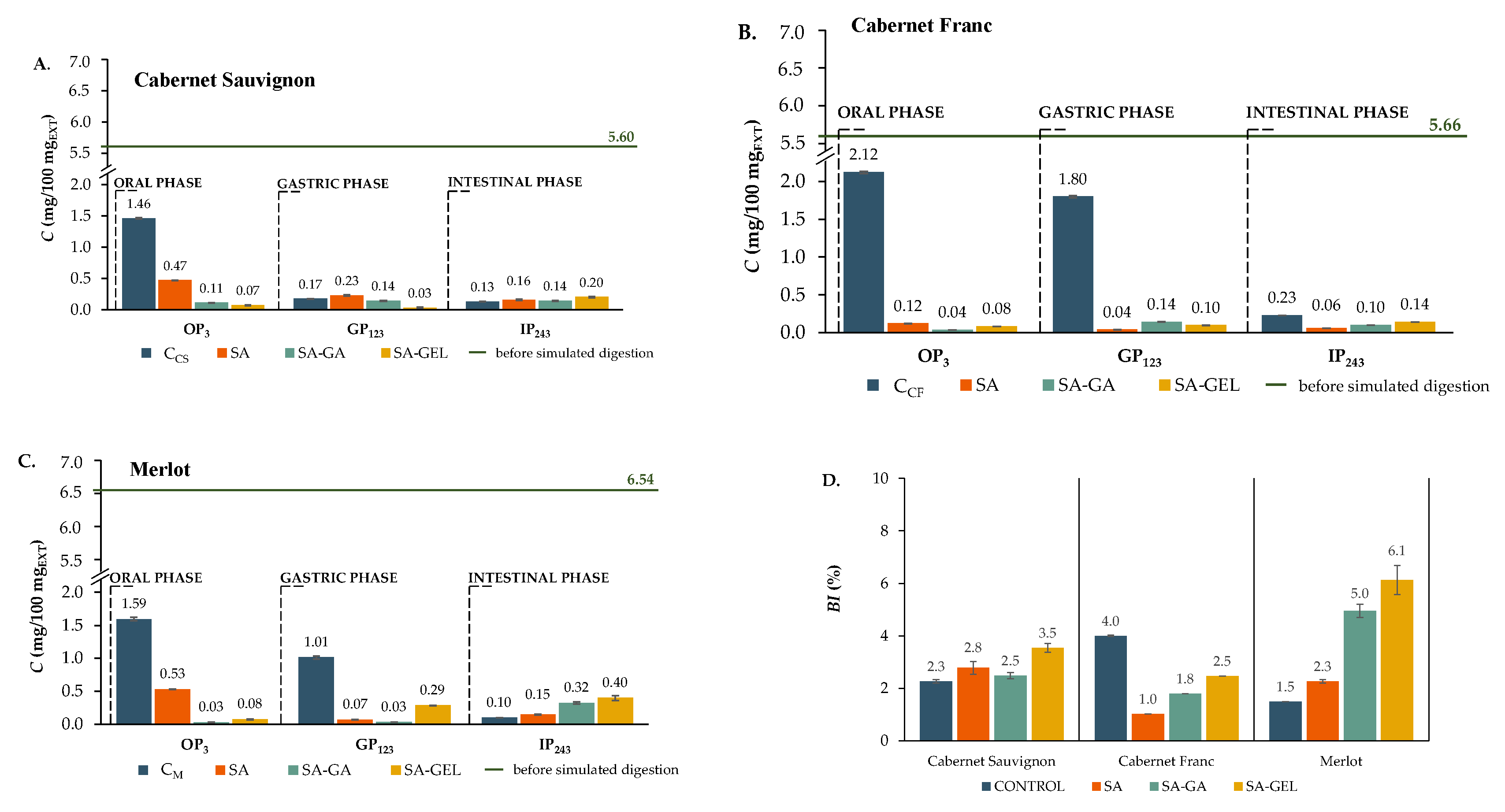

2.4.1. Total Phenolics, Total Flavonoids and Total Proanthocyanidins

The TPC, TFC and TPA released from the control samples and the microcapsules in the enzyme-containing digestion fluids after each digestion phase, as well as

BI for these samples are shown in

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7.

Encapsulated extracts in the OP showed noticeably lower TPC release than control samples for each variety (

Figure 5A-C). For instance, 14.12 mg

GAE/100 mg

EXT was released from the control C

CF, while only 1.01 to 2.05 mg

GAE/100 mg

EXT was released from the encapsulated Cabernet Franc samples, which were also the lowest concentrations of TPC released from all microcapsules (

Figure 5B). Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon showed similar release trend (

Figure 5A and C). In line with De Vos et al. [

38], this decrease in release is favourable compared to controls during OP as it protects phenolics from early degradation. In the GP, the microcapsules showed a slightly increased TPC release compared to the OP, while the release from the control samples decreased (

Figure 5A-C). According to

Figure 5A and C, the Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot microcapsules showed comparable patterns, with the SA microcapsules releasing less TPC than the control samples and the SA-GA and SA-GEL microcapsules releasing more TPC than the control samples. As described by De Vos et al. [

38] and Grgić et al. [

8] the intended outcome of phenolics encapsulation is minimized release in the acidic gastric environment in order to preserve these bioactives for subsequent intestinal absorption. This is demonstrated by the sustained release of TPC from the Cabernet Franc microcapsules during GP (

Figure 5B). In IP, the control samples showed less TPC release compared to GP, while the encapsulated samples demonstrated a gradual release of TPC compared to the controls with the Cabernet Franc SA microcapsules being the exception (

Figure 5A-C). SA-GEL microcapsules consistently achieved the highest TPC release across all varieties, with values ranging from 9.30–28.92 mg

GAE/100 mg

EXT (

Figure 5A–C). Spray-drying significantly improved the stability and bioaccessibility of TPC, which is reflected in the

BI values, which were higher in the most samples than in the controls.

BI ranged from 12.8–48.0% for SA microcapsules, 25.2–82.4% for SA-GA, and 37.8 – 110.8% for SA-GEL microcapsules (

Figure 5D). The only notable exception was Cabernet Franc SA microparticles, which showed a deviation from the general trend with lower

BI values compared to the control.

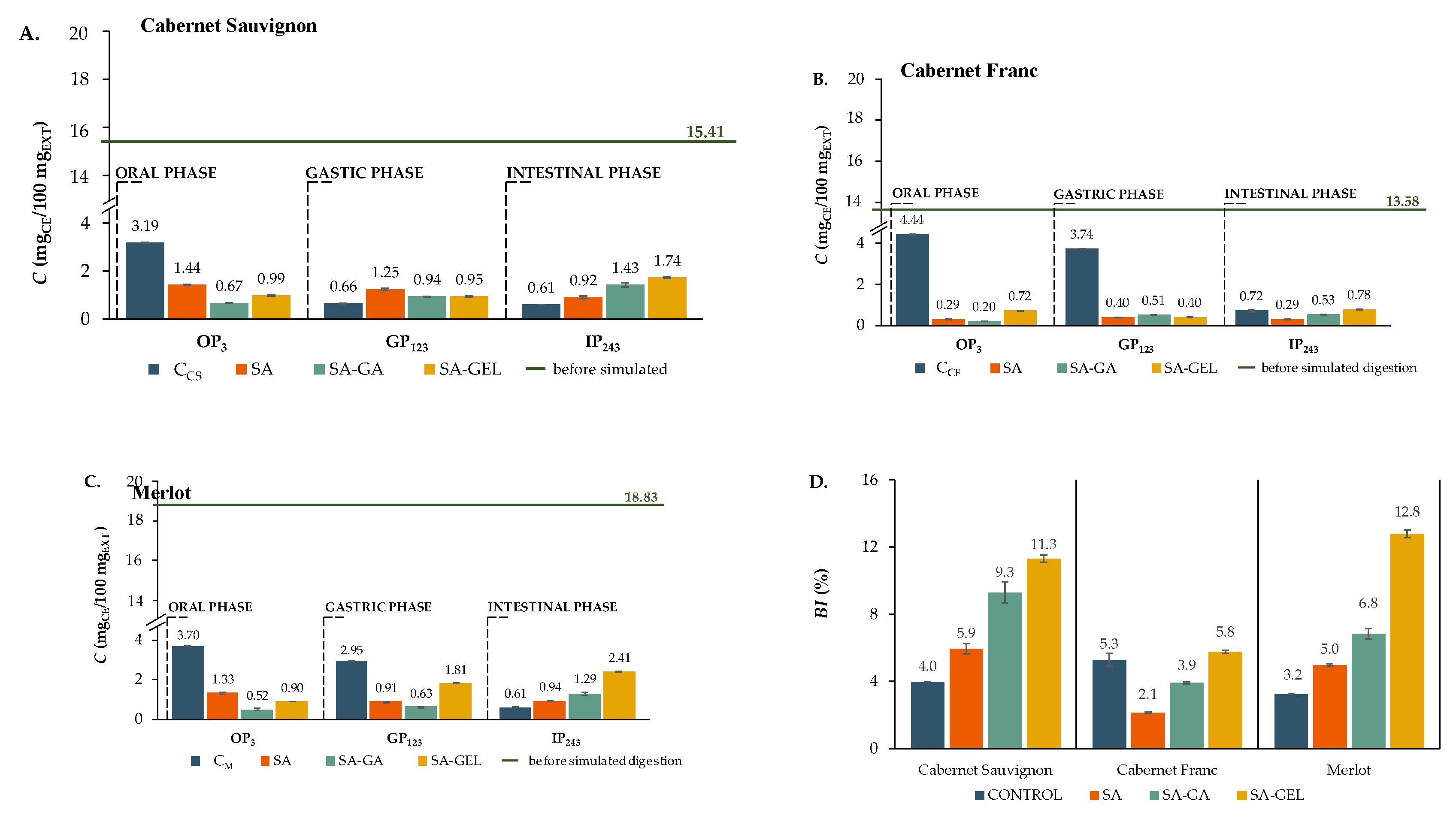

During the OP, TFC for all microcapsules were significantly lower than respective controls (3.19–4.44 mg

CE/100 mg

EXT) across all varieties (

Figure 6A–C). For example, the TFC release in OP from SA microcapsules ranged from 0.29 to 1.44 mg

CE/100 mg

EXT, while SA-GA microcapsules had a TFC release of 0.20 to 0.67 mg

CE/100 mg

EXT and SA-GEL microcapsules 0.72 to 0.99 mg

CE/100 mg

EXT. Since the early degradation of flavonoids is reduced and these compounds are preserved for the intestinal phase, which is more important for the absorption of nutrients, the lower release during OP shown in the encapsulated samples is beneficial, as Thilakarathna and Rupasinghe [

39] suggested. In addition, the controls showed an overall decrease in TFC release in GP compared to OP as well as the SA microcapsules of Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot and the SA-GEL microcapsules of Cabernet Sauvignon and Cabernet Franc (

Figure 6A–C). During GP, the Cabernet Franc and Merlot microcapsules showed lower TFC release than the control sample (

Figure 6B and C). Since flavonoids are easily degraded in the acidic environment of the stomach, this low release is beneficial. By maintaining stability during GP, the microcapsules ensure that the TFCs are available for the intestinal phase, where absorption mainly occurs as reported by Hollman [

40], and Kumar and Pandey [

41]. The IP showed many differences in TFC release, with encapsulated samples outperforming their respective controls in all varieties tested (

Figure 6A-C), with the exception of the Cabernet Franc SA and SA-GA microcapsules (

Figure 6B). This is reflected in the BI values shown in

Figure 6D. While 3.2 - 5.3% BI values were obtained for the control samples, the SA microcapsules showed 2.1 - 5.9% BI, SA-GA 3.9 - 9.3% and SA-GEL microcapsules showed the highest BI values for TFC between 5.8% to 12.8% (

Figure 6D).

The release of TPA during OP was consistently lower in encapsulated samples compared to control samples for all varieties with the highest values obtained for SA-coated microcapsules (0.12–0.53 mg/100 mg

EXT) (

Figure 7A–C). This reduction in release during OP is beneficial as it prevents premature degradation of proanthocyanidins in the mouth where absorption does not occur [

42,

43]. TPA release in the GP was lower in all control samples than in the OP and remained minimal in all encapsulated samples with no discernible release trend (

Figure 7A–C). This sustained low release is beneficial as it protects the proanthocyanidins from degradation in the acidic gastric environment and ensures their preservation for the intestinal phase where absorption predominantly occurs [

43]. As with GP, the release of TPA from the control samples decreased in IP. In addition, no distinct pattern can be seen in the release of TPA from the microcapsules, except that increase TPA release was observed in all SA-GEL microcapsules in compared to the GP (

Figure 7A-C). The encapsulated Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot samples also outperformed their respective controls and also achieved higher

BI values. The

BI of TPA ranged from 1.5–4.0% for the control samples to 1.0–2.8% for SA microcapsules, 1.8–5.0% for SA-GA, and 2.5–6.1% for SA-GEL (

Figure 7D).

Overall, the SA-GEL microcapsules consistently exhibited the highest BI values for TPC, TFC and TPA across all varieties, indicating that this combination of coatings provides superior protection and release efficiency. Among the varieties, the encapsulated samples of Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot showed more consistent trends in release and bioaccessibility, while Cabernet Franc showed some deviations. However, even for Cabernet Franc, encapsulation with SA-GEL significantly improved bioaccessibility compared to controls.

2.4.2. Bioaccessibility of Individual Phenolics

The

BI values for phenolic compounds observed at the end of the IP are shown in

Table 2, while the

Supplementary Materials (

Tables S1–S3) show a release profile of all quantifiable individual phenols in the microcapsules and the control samples at all stages of the in vitro digestion.

Phenolic acids. The highest BI of gallic acid was determined for the samples CS and M from the microcapsules SA-GA (117.0–222.6%) and SA-GEL (215.5–218.5%), whereby these values were significantly increased by 4.7–5.2-fold and 4.6–9.6-fold, respectively, compared to the controls. For 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid, the most significant increase in BI values of 2.1-19.3-fold was observed for all SA-GEL microcapsules compared to the control. Syringic acid was mainly released in the oral and gastric phase, whereas all control and encapsulated CS samples showed no release in the intestinal phase, so that a calculation of the BI is not possible in this case. However, syringic acid was detected in IP for CF and M microcapsules with BI values of 59.1–102.3% and 36.8–537.8%, respectively. BI values of vanillic acid improved with encapsulation, except for CF samples, with SA-GEL achieving the highest BI for CS (87.6%) and SA-GA for M (144.4%). Ellagic acid, which was minimally released from the control samples only in the IP, showed remarkable improvements in the BI values of SA-GEL and SA-GA microcapsules for sample M with the highest BI of 107.9% and 90.6%, respectively. Spray drying led to a significant improvement in the BI values of o-coumaric acid BI, especially from M-SA-GA and M-SA-GEL microcapsules, which reached 325.7% and 464.2%, respectively. However, p-coumaric acid, which was detected in all digestion phases in the control samples with BI values between 65.4 and 272.8 %, was not present in the microcapsules, indicating possible limitations in EE or low initial concentrations. Finally, p-hydroxybenzoic acid, caffeic acid and ferulic acid were not released by the simulated digestion in all samples.

Stilbenes and flavonoids. No release was observed for the stilbenes, resveratrol and ε-viniferin tested in both control and encapsulated samples (

Tables S1–S3), indicating a significant susceptibility to digestive conditions and consistent with the literature describing their sensitivity to pH and enzyme activity [

44]. Although no release of the flavonol kaempferol was observed from all samples, two other flavonols studied, quercetin and rutin, were identified in the OP and GP for all control samples, but not for the encapsulated samples (

Tables S1–S3).

Flavanols. Epicatechin was released differently depending on the grape variety and coating. Encapsulation improved

BIs, especially for CS and M encapsulated with SA-GA and SA-GEL, which reached 53.5–97.5% and 83.6–139.2%, respectively. On the other hand, catechin was not detected in the intestinal phase and its

BI could not be calculated for all samples. Epicatechin gallate, which was not detected in the oral phase, showed high

BIs, especially for CS (113.6–356.4%) and M microcapsules (367.8–476.4%). Gallocatechin gallate exhibit-ed exceptionally high

BIs after encapsulation, reaching 692.4–2028.7% for CS, 120.3–348.2% for CF and 580.7–1970.9% for M. Procyanidin B1, which was minimally released from control samples in OP and GP, showed improved

BIs after encapsulation, reaching

BI values of 71.2–155.1% for CS and 48.4–135.4% for M. Procyanidin B2 showed limited release in most samples, but the highest

BI was obtained for M-SA-GA microcapsules (283.8%). The lower stability of procyanidin B2 in later stages of digestion could be due to its complexation with other dietary components or its rapid degradation [

42,

45].

Anthocyanins. Encapsulation improved the

BI value of oenin chloride only in the CS–SA-GEL microcapsule (63.9 %) compared to the control sample. Myrtillin chloride and petunidin chloride were only detected in the control samples in OP and GP, while they were not detected in the IP. Kuromanin chloride was not detected in any of the samples. For peonidin-3-O-glucoside chloride, a

BI value was determined in all control samples (24.0–42.4%), and encapsulation did not improve

BI values in any of the microcapsules, indicating low stability of this com-pound under the tested conditions. The results obtained are consistent with previous studies indicating the susceptibility of anthocyanins to digestive conditions, which could not be mitigated by encapsulation under the current formulation and process conditions [

46].

In general, encapsulation had the greatest effect on increasing the

BI of phenolic acids and flavanols (

Table 2) compared to control samples. The

BI of 11 phenolic compounds was enhanced by adding an additional coating to SA, indicating possible interactions between the coating matrix and the phenolic compounds [

47,

48]. For example, the hydroxyl groups of gallic acid can form stabilizing hydrogen bonds with the gelatin in SA-GEL [

49,

50], while the emulsion-stabilizing properties of gum Arabic in SA-GA create a protective environment for the syringic acid [

51,

52]. These compound-matrix interactions influence how effectively the individual phenolic acids are protected and released, and ultimately improve bioaccessibility, reflecting the ability of the coating combination to protect the active ingredients from early degradation and promote their release in the intestinal phase, where absorption is most favourable. According to the results, there were notable differences in the

BI of phenolic compounds between grape varieties, with Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon often showing greater

BI improvements than Cabernet Franc. This suggests that the effectiveness of encapsulation is not uniform across varieties, likely due to differences in the chemical composition and interactions of phenolic compounds with the coating matrices.

3. Conclusions

This study offers important information about how spray-dried microencapsulation of phenol-rich grape pomace extracts (CS, CF, and M) using various coatings (SA, SA-GA, SA-GEL) affects the release behaviour of phenolic compounds and bioaccessibility during simulated digestion in vitro. The findings demonstrated notable variations in physicochemical characteristics, release patterns, and EE, highlighting the significance of coating selection for certain functional goals.

The coatings used had a significant impact on encapsulation efficiency, regardless of the grape pomace tested. The combination of coatings resulted in a higher EE efficiency of 22.33–38.24 % and 38.76–68.14 % for SA-GA and SA-GEL microcapsules, respectively, compared to SA.

Physicochemical characterization revealed that mostly spherical particles were produced, with GA improving stability and reducing coalescence, while GEL caused surface irregularities. Thermal and structural analyses confirmed the amorphous nature of all coatings and microcapsules, as shown by XRPD and DSC results. Enzyme-free release showed coating-dependent TPC release, with the SA and SA-GA microcapsules exhibiting minimal intestinal release and the SA-GEL microcapsules achieving the highest intestinal release (64.10–75.93%), which is ideal for potential TPC absorption.

The simulated digestion study showed that encapsulation significantly improved the BI of phenolic compounds, especially phenolic acids and flavanols. SA-GEL coatings performed the best for most of the tested compounds, probably due to the pH sensitivity of gelatin, followed by SA-GA coatings. Anthocyanins and stilbenes showed lower stability, highlighting the need for improved formulations. BI varied between grape varieties, with Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon generally outperforming Cabernet Franc, highlighting the influence of coating composition and grape variety on phenolic stability and bioaccessibility.

By valorising grape pomace, these results contribute to sustainable food processing practices while meeting the growing demand for functional ingredients. Future research should focus on optimizing encapsulation for industrial-scale applications, evaluating the long-term stability of the formulations, and conducting further studies to confirm bioactivity and physiological effects, while exploring integration into commercial products to support the development of health-promoting, sustainable food products.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

The chemicals for encapsulation (coatings SA, GA, GEL) and in vitro digestion (pepsin and pancreatin enzymes and porcine bile extract) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO, USA). Reagents for spectrophotometric determination of TPC, TFC and TPA were purchased from CPA chem (Bogomilovo, Bulgaria), Alfa Aesar GmbH & Co KG (Kandel, Germany) and Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium). Authentic standards of phenolic acids, flavonols, flavan-3-ols, stilbenes and anthocyanins were purchased from Sigma Al-drich (Saint Louis, MO, USA), Extrasynthese (Genay, France), Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium) and Applihem (Darmstadt, Germany).

Grape pomace left over after the processing of Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc and Merlot grapes into wine at the Erdut winery (Erdutski vinogradi d.d., Croatia) was used. The collected grape pomace, consisted of seeds, skin and pulp, was air-dried at room temperature for 48 hours and stored in closed containers at room temperature before use. Prior to the experiments, the dried pomace was milled to a particle size of ≤ 1 mm using an ultracentrifugal mill (Retsch ZM200, Haan, Germany). The dry matter content of the pomace was measured and recorded as follows: Cabernet Sauvignon—92.91 ± 0.01%, Cabernet Franc—91.95 ± 0.02%, and Merlot—92.15 ± 0.04%.

4.2. Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Grape Pomace

Conventional extraction of the phenolic compounds from the pomace samples (1 g) was carried out with 40 mL of a 50% ethanol solution at 80 °C with continuous stirring at 200 rpm in a shaking water bath (Julabo, SW-23, Seelbach, Germany) for 120 minutes. After extraction, the mixture was centrifuged at 11,000×

g for 10 minutes (Z 326 K, Hermle Labortechnik GmbH, Germany) to separate the supernatant [

53].

The supernatant was concentrated under vacuum (48 mbar/50 °C; Büchi, R-210, Flawil, Switzerland) by halving the volume to minimize the ethanol content. The removed ethanol was replaced by an appropriate amount of redistilled water, resulting in a phenol-rich pomace extract, which was subjected to spray-dried encapsulation.

4.3. Spray-Drying Microencapsulation

The encapsulation mixture, consisting of the extract and the coating(s), was prepared in a glass vessel using a magnetic stirrer (Witeg Labortechnik GmbH, Wertheim, Germany) at room temperature 24 h. The concentration of SA was 1% (w/v), while the concentration of GA was 0.53% (w/v) and GEL 1.67% (w/v). Spray-drying of the prepared mixture was performed using a B-290 mini spray-dryer (BÜCHI Labortechnik AG, Flawil, Switzerland) equipped with a 1.5 mm nozzle cap and a 0.5 mm needle. The process was carried out at an inlet air temperature of 180 °C and an outlet temperature of 89 °C. The pumping rate was set to 25%, with an approximate air flow of 600 L/h. The resulting microcapsules (MC) were collected in a separating flask and then stored in sealed sample containers at 4 °C in the dark until further analysis.

4.4. Characterization of Microcapsules

4.4.1. Encapsulation Efficiency Determination

The

EE (%) was determined by measuring the total phenolic content in the microcapsules (TPC

MC, mg

GAE/g

db) and the surface phenolic content (SPC

MC, mg

GAE/g

db) based on the method described by Vu et al. [

54] using the following Equation (1):

As described by Tolun et al. [

55], the samples were prepared for the determination of TPC

MC and SPC

MC. Briefly, for TPC

MC 15 mg of MC was vortexed with 3 mL of an ethanol/glacial acetic acid/water solution (50:8:42, v/v/v) and the mixture was filtered through a 0.45 μm PTFE filter. For SPC

MC, 24 mg of MC was dissolved in 3 mL ethanol/methanol (1:1, v/v) and also filtered through a 0.45 μm PTFE filter.

After filtration of the samples, TPC

MC and SPC

MC were determined by the Folin–Ciocalteu method as described in

Section 4.5.1. Total Phenolic Content (TPC). The results were expressed as gallic acid equivalents per MC dry basis (mg

GAE/g

db) ± SD.

4.4.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with a Hitachi S4700 instrument (Hitachi Scientific Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at 10 kV was used to analyse the morphology of the microcapsules. Before imaging, a thin layer of gold-palladium was sputtered onto the samples.

4.4.3. X-Ray Powder Diffraction

The structural properties of the coatings and microcapsules were analysed using an X-ray powder diffractometer (BRUKER D8 Advance diffractometer, Karlsruhe, Germany) with Cu Kα radiation at λ = 1.5406 Å over an angular range of 3‒40° 2θ. Scanning was performed at 40 kV and 40 mA, and the VANTEC-1 detector was used to generate diffractograms. Data processing, including background removal, smoothing, and Kα2 stripping, was performed using DIFFRAC plus EVA software (version 13.0.0.1, Karlsruhe, Germany).

4.4.4. Differential Scanning Calorimetry

The thermal behaviour of the coatings and microcapsules were analysed using a differential scanning calorimeter (Mettler Toledo 821e DSC; Mettler Inc., Schwerzenbach, Switzerland). The samples (3–5 mg) placed in aluminium pans were heated at a constant rate of 10 °C/min in the temperature range of 25–300 °C under a constant argon flow of 150 ml/min. The thermograms were analysed using STARe software (version 9.3, Mettler Toledo; Mettler Inc., Schwerzenbach Switzerland).

4.5. Determination of Phenolic Compounds

4.5.1. Total Phenolic Content

The TPC was analysed according to the modified method proposed by Waterhouse [

56]. A mixture of 40 µL sample, 3160 µL distilled water, 200 µL Folin–Ciocalteu reagent and 600 µL sodium carbonate (20% w/v) was incubated at 40 °C for 30 minutes. The absorbance was read at 765 nm against a solvent blank and the results were expressed as the mean of three replicates ± standard deviation (SD) as gallic acid equivalents per weight of extracts (mg

GAE/100 mg

EXT).

4.5.2. Total Flavonoid Content

TFC was determined using a modified aluminium chloride method [

57]. A sample of 500 µL was mixed with 2 mL water, 150 µL 5% sodium nitrite, 150 µL 10% aluminium chloride and after 6 minutes with 1 mL 1 M sodium hydroxide. The mixture was diluted with distilled water (1.2 ml) to a total volume of 5 ml, shaken and the absorbance was read at 510 nm. The results were expressed as the mean of three replicates ± standard deviation (SD) as (+)-catechin equivalents per weight of extracts (mg

CE/100 mg

EXT).

4.5.3. Total Extractable Proanthocyanidin Content

TPA was measured using a modified acid–butanol reaction method [

58]. A mixture of ferrous sulphate heptahydrate solution and HCl-butanol (2:3, v/v) was added to 500 µL of the sample. After incubation at 95 °C for 15 minutes and cooling, the absorbance was read at 540 nm. TPA values were calculated using the molar weight of cyanidin and the extinction coefficient and expressed in mg per 100 mg of extracts as the mean of three replicates ± standard deviation (SD).

4.5.4. Individual Phenolic Compounds Determination

The content of individual phenolic compounds (phenolic acids, flavanols, flavonols, stilbenes and anthocyanins) in the control samples and the prepared microcapsules was analysed by ultra-high performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC Nexera XR, Shimadzu, Japan) with a photodiode detector. A reversed-phase Kinetex® C18 core-shell column (100 × 4.6 mm, 2.6 µm, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) was used for the separation. Samples were dissolved in appropriate solvents and concentrations, then filtered through 0.45 µm membranes and analysed using LabSolutions software (version 5.87). Individual phenolics were identified and quantified by comparing their UV–Vis spectra and retention times with authentic standards under the same chromatographic conditions. Calibration curves were generated using external standards. The results, expressed as average of triplicates ± standard deviation (SD), were obtained from all measurements.

Phenolic acids, flavanols, flavonols and stilbenes were quantified according to the method of Bucić-Kojić et al. [

59]. A linear gradient of two mobile phases was used: Phase A (1.0% acetic acid in water) and Phase B (methanol–acetonitrile, 50:50, v/v). Chromatography was performed at 30 °C with a flow rate of 1 mL/min, with the injection volume of sample 20 µL.

The anthocyanins were analysed according to Bucić-Kojić et al. [

60] using mobile phases A (water/formic acid/acetonitrile, 87:10:3, v/v/v) and B (water/formic acid/acetonitrile, 40:10:50, v/v/v). The injection volume was 20 µL at a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min.

4.6. Phenolic Compounds Release and Bioaccessibility Studies

4.6.1. Enzyme-Free Release Study

This study followed the modified INFOGEST protocol [

61] described by Martinović et al. [

22] and observed the release of phenolic compounds over 243 minutes. The process was carried out at 37 °C with constant stirring.

OP: 200 mg of the microcapsules, 4 mL of simulated salivary fluid (SSF) and 25 µL of CaCl2(H2O)2 were mixed. The pH was adjusted to 7 and the volume was made up to 10 mL with redistilled water. After 3 minutes, 2 mL were withdrawn for TPC analysis and replaced with SSF.

GP: 8 mL of simulated gastric fluid (SGF) and 5 µL of CaCl2(H2O)2 were added and the pH was lowered to 3 with 1 M HCl. The final volume was adjusted to 20 mL. Over a period of 120 minutes, samples were taken at specific intervals and the SGF was replenished.

IP: 16 mL of simulated intestinal fluid (SIF) and 40 µL of CaCl2(H2O)2 were added and the pH was adjusted to 7. The volume was increased to 40 mL and this phase lasted 120 minutes, with samples being taken at specific intervals and the SIF replenished as required.

First order, Higuchi, Hixson–Crowell and Korsmeyer–Peppas mathematical models were applied to analyse the release of phenols during enzyme-free in vitro studies. Data analysis was performed using DDSolver [

62], and the best fitting model was determined using the adjusted R² (R²

adj), the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and the model selection criterion (MSC).

4.6.2. In Vitro Simulated Digestion and Determination of Bioaccessibility Index

In vitro digestion with enzymes followed the modified INFOGEST protocol as described by Martinović et al. [

22]. Test tubes representing specific digestion time points (OP

3, GP

63, GP

123, IP

163, IP

243) were mixed with a vertical rotator (PTR-60, Grant-bio Instruments, UK) in a thermostat (TC 135 S, Lovibond, Dortmund, Germany) at 37 °C.

For the OP, 100 mg of the control sample or 200 mg of the microcapsules were mixed with 4 mL of simulated saliva fluid (SSF) and 25 µL of CaCl2(H2O)2. The pH was adjusted to 7 and the total volume was made up to 10 mL with distilled water. After 3 minutes, the OP test tube (OP3) was removed and the gastric phase (GP) began in the remaining tubes by adding 8 mL of simulated gastric fluid (SGF), 5 µL of CaCl2(H2O)2, 500 µL of pepsin and water to a total volume of 20 mL. The samples were taken at specific time points (GP63, GP123). The IP began with the addition of 8.5 mL simulated intestinal fluid (SIF), 40 µL CaCl2(H2O)2, 5 mL pancreatin solution, 2.5 mL bile extract solution and water to adjust the volume to 40 mL. Samples were collected at IP163 and IP243 to complete the digestion process. After removal, the test tubes were centrifuged (16,000× g, 4 °C, 30 min) and the supernatant was filtered through 0.45 μm membranes (Syringe filters Spheros Nylon, Agilent Technologies, USA).

To remove impurities such as salts, bile and enzyme residues, solid phase extraction was performed according to a modified method by Kamiloglu et al. [

63], as described by Martinović et al. [

22]. The prepared samples were then analysed for TPC, TFC, TPA and individual phenolic compounds.

The bioaccessibility index (

BI, %) was calculated using the following Equation (2):

where

CA is the content of phenolic compounds after complete digestion (IP

243) and

CB is the content before digestion in control sample, expressed per 100 mg extract.

4.7. Statistical Analysis

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using TIBCO Statistica software to evaluate the statistical significance of the differences between the mean values of the samples. If significant differences were found, Duncan's multiple range test was applied as a post-hoc analysis to identify specific sample groups with significant differences (

p < 0.05) [

22].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: TPC release from differently coated extracts of different grape pomace (A. – Cabernet Sauvignon, B. – Cabernet Franc and C. – Merlot) during simulated digestion without enzymes, expressed as gallic acid equivalent per microcapsule mass; Figure S2: Kinetics of TPC release from the microencapsulated extracts with different coatings SA (A.); SA-GA (B.); SA-GEL (C.) (symbols – experimental data, lines – approximate curves according to different mathematical models); Table S1. Release profile of individual phenolics from Cabernet Sauvignon control extract (CCS) and from SA, SA-GA and SA-GEL microcapsules before digestion (BD) and during all phases of simulated in vitro digestion; Table S2. Release profile of individual phenolics from Cabernet Franc control extract (CCF) and from SA, SA-GA and SA-GEL microcapsules before digestion (BD) and during all phases of simulated in vitro digestion.; Table S3. Release profile of individual phenolics from Merlot control extract (CM) and from SA, SA-GA and SA-GEL microcapsules before digestion (BD) and during all phases of simulated in vitro digestion.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M., A.B.-K.; investigation, J.M., R.A.; formal analysis, G.P., A.-M.K., G.Š; writing—original draft preparation, J.M; data curation, J.M., M.P., writing—review and editing, M.P., R.A., A.B.-K.; supervision, A.B.-K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the CROATIAN SCIENCE FOUNDATION, grant number: IP-2018-01-1227 (“Development of a sustainable integrated process for the production of bioactive isolates from food industry residues”, POPI-WinCEco); BILATERAL PROJECT CROATIA–HUNGARY, grant number: HR-HUN_2020_011 and 2019-2.1.11-TÉT-2020-00146 (˝Encapsulation of polyphenol-rich extracts from food industry residues and characterization of encapsulated particles˝); and by the MINISTRY OF HUMAN CAPACITIES, HUNGARY, grant number: TKP2021-EGA-32.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the winery of the company Erdutski vinogradi d.o.o., Croatia, for the donation of grape pomace samples.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fontana, A.R.; Antoniolli, A.; Bottini, R. Grape Pomace as a Sustainable Source of Bioactive Compounds: Extraction, Characterization, and Biotechnological Applications of Phenolics. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 8987–9003. [CrossRef]

- Almanza-Oliveros, A.; Bautista-Hernández, I.; Castro-López, C.; Aguilar-Zárate, P.; Meza-Carranco, Z.; Rojas, R.; Michel, M.R.; Martínez-Ávila, G.C.G. Grape Pomace—Advances in Its Bioactivity, Health Benefits, and Food Applications. Foods 2024, 13, 580. [CrossRef]

- Vuolo, M.M.; Lima, V.S.; Maróstica Junior, M.R. Phenolic Compounds. In Bioactive Compounds; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 33–50 ISBN 978-0-12-814774-0.

- Mišković Špoljarić, K.; Šelo, G.; Pešut, E.; Martinović, J.; Planinić, M.; Tišma, M.; Bucić-Kojić, A. Antioxidant and Antiproliferative Potentials of Phenolic-Rich Extracts from Biotransformed Grape Pomace in Colorectal Cancer. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2023, 23, 29. [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, C.M.; Dias, M.I.; Alves, M.J.; Calhelha, R.C.; Barros, L.; Pinho, S.P.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Grape Pomace as a Source of Phenolic Compounds and Diverse Bioactive Properties. Food Chem. 2018, 253, 132–138. [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, G.; Maisto, M.; Schisano, C.; Ciampaglia, R.; Narciso, V.; Hassan, S.T.S.; Tenore, G.C.; Novellino, E. Effect of Grape Pomace Polyphenols With or Without Pectin on TMAO Serum Levels Assessed by LC/MS-Based Assay: A Preliminary Clinical Study on Overweight/Obese Subjects. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 575. [CrossRef]

- Parisi, O.I.; Puoci, F.; Restuccia, D.; Farina, G.; Iemma, F.; Picci, N. Polyphenols and Their Formulations. In Polyphenols in Human Health and Disease; Elsevier, 2014; pp. 29–45 ISBN 978-0-12-398456-2.

- Grgić, J.; Šelo, G.; Planinić, M.; Tišma, M.; Bucić-Kojić, A. Role of the Encapsulation in Bioavailability of Phenolic Compounds. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 923. [CrossRef]

- Rein, M.J.; Renouf, M.; Cruz-Hernandez, C.; Actis-Goretta, L.; Thakkar, S.K.; Da Silva Pinto, M. Bioavailability of Bioactive Food Compounds: A Challenging Journey to Bioefficacy. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 75, 588–602. [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Dumont, M.-J.; Orsat, V. Encapsulation of Phenolic Compounds Present in Plants Using Protein Matrices. Food Biosci. 2016, 15, 87–104. [CrossRef]

- Neilson, A.P.; Goodrich, K.M.; Ferruzzi, M.G. Bioavailability and Metabolism of Bioactive Compounds From Foods. In Nutrition in the Prevention and Treatment of Disease; Elsevier, 2017; pp. 301–319 ISBN 978-0-12-802928-2.

- Lorenzo, J.M.; Estévez, M.; Barba, F.J.; Thirumdas, R.; Franco, D.; Munekata, P.E.S. Polyphenols: Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability of Bioactive Components. In Innovative Thermal and Non-Thermal Processing, Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability of Nutrients and Bioactive Compounds; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 309–332 ISBN 978-0-12-814174-8.

- Rezvankhah, A.; Emam-Djomeh, Z.; Askari, G. Encapsulation and Delivery of Bioactive Compounds Using Spray and Freeze-Drying Techniques: A Review. Dry. Technol. 2020, 38, 235–258. [CrossRef]

- Bernal-Millán, M.D.J.; Gutiérrez-Grijalva, E.P.; Contreras-Angulo, L.; Muy-Rangel, M.D.; López-Martínez, L.X.; Heredia, J.B. Spray-Dried Microencapsulation of Oregano (Lippia Graveolens) Polyphenols with Maltodextrin Enhances Their Stability during In Vitro Digestion. J. Chem. 2022, 2022, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Perković, G.; Planinić, M.; Šelo, G.; Martinović, J.; Nedić, R.; Puš, M.; Bucić-Kojić, A. Optimisation of the Encapsulation of Grape Pomace Extract by Spray Drying Using Goat Whey Protein as a Coating Material. Coatings 2024, 14, 1101. [CrossRef]

- Abka-khajouei, R.; Tounsi, L.; Shahabi, N.; Patel, A.K.; Abdelkafi, S.; Michaud, P. Structures, Properties and Applications of Alginates. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 364. [CrossRef]

- Abourehab, M.A.S.; Rajendran, R.R.; Singh, A.; Pramanik, S.; Shrivastav, P.; Ansari, M.J.; Manne, R.; Amaral, L.S.; Deepak, A. Alginate as a Promising Biopolymer in Drug Delivery and Wound Healing: A Review of the State-of-the-Art. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9035. [CrossRef]

- Gim, S.; Zhu, Y.; Seeberger, P.H.; Delbianco, M. Carbohydrate-based Nanomaterials for Biomedical Applications. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2019, 11, e1558. [CrossRef]

- Akbarbaglu, Z.; Peighambardoust, S.H.; Sarabandi, K.; Jafari, S.M. Spray Drying Encapsulation of Bioactive Compounds within Protein-Based Carriers; Different Options and Applications. Food Chem. 2021, 359, 129965. [CrossRef]

- Madkhali, O.A. Drug Delivery of Gelatin Nanoparticles as a Biodegradable Polymer for the Treatment of Infectious Diseases: Perspectives and Challenges. Polymers 2023, 15, 4327. [CrossRef]

- Kieserling, H.; De Bruijn, W.J.C.; Keppler, J.; Yang, J.; Sagu, S.T.; Güterbock, D.; Rawel, H.; Schwarz, K.; Vincken, J.; Schieber, A.; et al. Protein–Phenolic Interactions and Reactions: Discrepancies, Challenges, and Opportunities. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Safe. 2024, 23, e70015. [CrossRef]

- Martinović, J.; Lukinac, J.; Jukić, M.; Ambrus, R.; Planinić, M.; Šelo, G.; Klarić, A.-M.; Perković, G.; Bucić-Kojić, A. In Vitro Bioaccessibility Assessment of Phenolic Compounds from Encapsulated Grape Pomace Extract by Ionic Gelation. Molecules 2023, 28, 5285. [CrossRef]

- Martinović, J.; Ambrus, R.; Planinić, M.; Šelo, G.; Klarić, A.-M.; Perković, G.; Bucić-Kojić, A. Microencapsulation of Grape Pomace Extracts with Alginate-Based Coatings by Freeze-Drying: Release Kinetics and In Vitro Bioaccessibility Assessment of Phenolic Compounds. Gels 2024, 10, 353. [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Yu, Y.; Chen, M.; Ren, Z.; Chen, L.; Fu, C.; Ma, Z.F.; Li, Z. Advancement of Protein- and Polysaccharide-Based Biopolymers for Anthocyanin Encapsulation. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 938829. [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Morales, E.A.; Mendez-Montealvo, G.; Velazquez, G. Interactions of the Molecular Assembly of Polysaccharide-Protein Systems as Encapsulation Materials. A Review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 295, 102398. [CrossRef]

- Motlagh, S.; Ravines, P.; Karamallah, K.A.; Ma, Q. The Analysis of Acacia Gums Using Electrophoresis. Food Hydrocoll. 2006, 20, 848–854. [CrossRef]

- Murmu, S.B.; Mishra, H.N. Optimization of the Arabic Gum Based Edible Coating Formulations with Sodium Caseinate and Tulsi Extract for Guava. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 80, 271–279. [CrossRef]

- Tonon, R.V.; Brabet, C.; Hubinger, M.D. Influence of Process Conditions on the Physicochemical Properties of Açai (Euterpe Oleraceae Mart.) Powder Produced by Spray Drying. J. Food Eng. 2008, 88, 411–418. [CrossRef]

- Botrel, D.A.; De Barros Fernandes, R.V.; Borges, S.V.; Yoshida, M.I. Influence of Wall Matrix Systems on the Properties of Spray-Dried Microparticles Containing Fish Oil. Int. Food Res. 2014, 62, 344–352. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, S.; Cao, J.; Zhao, S.; Wang, W. Microencapsulation of Ginger Volatile Oil Based on Gelatin/Sodium Alginate Polyelectrolyte Complex. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2016, 64, 21–26. [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Zhong, Q. The Improved Thermal Stability of Anthocyanins at pH 5.0 by Gum Arabic. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 64, 706–712. [CrossRef]

- Barra, P.A.; Márquez, K.; Gil-Castell, O.; Mujica, J.; Ribes-Greus, A.; Faccini, M. Spray-Drying Performance and Thermal Stability of L-Ascorbic Acid Microencapsulated with Sodium Alginate and Gum Arabic. Molecules 2019, 24, 2872. [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Chen, Y.; Liu, M. Thermal Properties Measurements of Renatured Gelatin Using Conventional and Temperature Modulated Differential Scanning Calorimetry. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2006, 99, 1795–1801. [CrossRef]

- Anirudhan, T.S.; Mohan, A.M. Novel pH Switchable Gelatin Based Hydrogel for the Controlled Delivery of the Anti Cancer Drug 5-Fluorouracil. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 12109. [CrossRef]

- Korsmeyer, R.W.; Gurny, R.; Doelker, E.; Buri, P.; Peppas, N.A. Mechanisms of Solute Release from Porous Hydrophilic Polymers. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 1983, 15, 25–35. [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.; Sousa Lobo, J.M. Modeling and Comparison of Dissolution Profiles. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2001, 13, 123–133. [CrossRef]

- Siepmann, J.; Siepmann, F. Mathematical Modeling of Drug Delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2008, 364, 328–343. [CrossRef]

- De Vos, P.; Faas, M.M.; Spasojevic, M.; Sikkema, J. Encapsulation for Preservation of Functionality and Targeted Delivery of Bioactive Food Components. Int. Dairy J. 2010, 20, 292–302. [CrossRef]

- Thilakarathna, S.; Rupasinghe, H. Flavonoid Bioavailability and Attempts for Bioavailability Enhancement. Nutrients 2013, 5, 3367–3387. [CrossRef]

- Hollman, P.C.H. Absorption, Bioavailability, and Metabolism of Flavonoids. Pharm. Biol. 2004, 42, 74–83.

- Kumar, S.; Pandey, A.K. Chemistry and Biological Activities of Flavonoids: An Overview. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 162750. [CrossRef]

- Ou, K.; Gu, L. Absorption and Metabolism of Proanthocyanidins. J. Funct. Foods 2014, 7, 43–53. [CrossRef]

- Niwano, Y.; Kohzaki, H.; Shirato, M.; Shishido, S.; Nakamura, K. Metabolic Fate of Orally Ingested Proanthocyanidins through the Digestive Tract. Antioxidants 2022, 12, 17. [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, C.; Marzorati, M.; Innocenti, M.; Vilchez-Vargas, R.; Vital, M.; Pieper, D.H.; Van De Wiele, T.; Mulinacci, N. Dietary Supplement Based on Stilbenes: A Focus on Gut Microbial Metabolism by the in Vitro Simulator M-SHIME®. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 4564–4575. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.Y.; Holt, R.R.; Lazarus, S.A.; Ensunsa, J.L.; Hammerstone, J.F.; Schmitz, H.H.; Keen, C.L. Stability of the Flavan-3-Ols Epicatechin and Catechin and Related Dimeric Procyanidins Derived from Cocoa. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 1700–1705. [CrossRef]

- Tarone, A.G.; Cazarin, C.B.B.; Marostica Junior, M.R. Anthocyanins: New Techniques and Challenges in Microencapsulation. Food Res. Int. 2020, 133, 109092. [CrossRef]

- Ribas-Agustí, A.; Martín-Belloso, O.; Soliva-Fortuny, R.; Elez-Martínez, P. Food Processing Strategies to Enhance Phenolic Compounds Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability in Plant-Based Foods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 2531–2548. [CrossRef]

- Sęczyk, Ł.; Sugier, D.; Świeca, M.; Gawlik-Dziki, U. The Effect of in Vitro Digestion, Food Matrix, and Hydrothermal Treatment on the Potential Bioaccessibility of Selected Phenolic Compounds. Food Chem. 2021, 344, 128581. [CrossRef]

- Hager, A.-S.; Vallons, K.J.R.; Arendt, E.K. Influence of Gallic Acid and Tannic Acid on the Mechanical and Barrier Properties of Wheat Gluten Films. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 6157–6163. [CrossRef]

- Asghari-Varzaneh, E.; Sharifian-Mobarakeh, S.; Shekarchizadeh, H. Enhancing Hamburger Shelf Life and Quality Using Gallic Acid Encapsulated in Gelatin/Tragacanth Gum Complex Coacervate. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24917. [CrossRef]

- De Souza, A.G.; Cesco, C.T.; De Lima, G.F.; Artifon, S.E.S.; Rosa, D.D.S.; Paulino, A.T. Arabic Gum-Based Composite Hydrogels Reinforced with Eucalyptus and Pinus Residues for Controlled Phosphorus Release. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 140, 33–42. [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Goyal, A. Applications of Natural Polymer Gum Arabic: A Review. Int. J. Food Prop. 2015, 18, 986–998. [CrossRef]

- Šelo, G.; Planinić, M.; Tišma, M.; Martinović, J.; Perković, G.; Bucić-Kojić, A. Bioconversion of Grape Pomace with Rhizopus Oryzae under Solid-State Conditions: Changes in the Chemical Composition and Profile of Phenolic Compounds. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 956. [CrossRef]

- Vu, H.T.; Scarlett, C.J.; Vuong, Q.V. Encapsulation of Phenolic-Rich Extract from Banana (Musa Cavendish) Peel. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 2089–2098. [CrossRef]

- Tolun, A.; Altintas, Z.; Artik, N. Microencapsulation of Grape Polyphenols Using Maltodextrin and Gum Arabic as Two Alternative Coating Materials: Development and Characterization. J. Biotech. 2016, 239, 23–33. [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.L. Determination of Total Phenolics. In Current Protocols in Food Analytical Chemistry; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2001; p. I1.1.1-I1.1.8.

- Marinova, D.; Ribarova, F.; Atanassova, M. TOTAL PHENOLICS AND TOTAL FLAVONOIDS IN BULGARIAN FRUITS AND VEGETABLES. J. Univ. Chem. Technol. Metall. 2005, 40, 255–260.

- Škerget, M.; Kotnik, P.; Hadolin, M.; Hraš, A.R.; Simonič, M.; Knez, Ž. Phenols, Proanthocyanidins, Flavones and Flavonols in Some Plant Materials and Their Antioxidant Activities. Food Chem. 2005, 89, 191–198. [CrossRef]

- Bucić-Kojić, A.; Šelo, G.; Zelić, B.; Planinić, M.; Tišma, M. Recovery of Phenolic Acid and Enzyme Production from Corn Silage Biologically Treated by Trametes Versicolor. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2017, 181, 948–960. [CrossRef]

- Bucić-Kojić, A.; Fernandes, F.; Silva, T.; Planinić, M.; Šelo, G.; Šibalić, D.; Pereira, D.M.; Andrade, P.B. Enhancement of the Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Grape Pomace Treated by Trametes Versicolor. Food. Funct. 2020, 11, 680–688.

- Brodkorb, A.; Egger, L.; Alminger, M.; Alvito, P.; Assunção, R.; Ballance, S.; Bohn, T.; Bourlieu-Lacanal, C.; Boutrou, R.; Carrière, F.; et al. INFOGEST Static in Vitro Simulation of Gastrointestinal Food Digestion. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 991–1014. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huo, M.; Zhou, J.; Zou, A.; Li, W.; Yao, C.; Xie, S. DDSolver: An Add-In Program for Modeling and Comparison of Drug Dissolution Profiles. AAPS J. 2010, 12, 263–271. [CrossRef]

- Kamiloglu, S.; Ozkan, G.; Isik, H.; Horoz, O.; Van Camp, J.; Capanoglu, E. Black Carrot Pomace as a Source of Polyphenols for Enhancing the Nutritional Value of Cake: An in Vitro Digestion Study with a Standardized Static Model. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 77, 475–481. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Encapsulation efficiency (EE, %) of phenol-rich grape pomace extracts using various coatings (SA – sodium alginate, SA-GA – combination of sodium alginate with gum Arabica, and SA-GEL – combination of sodium alginate with gelatin). Bars marked with different letters indicate statistically significant differences between the mean value of EE according to Duncan's post hoc test (p < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Encapsulation efficiency (EE, %) of phenol-rich grape pomace extracts using various coatings (SA – sodium alginate, SA-GA – combination of sodium alginate with gum Arabica, and SA-GEL – combination of sodium alginate with gelatin). Bars marked with different letters indicate statistically significant differences between the mean value of EE according to Duncan's post hoc test (p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

SEM images of microcapsules prepared with different coatings containing extracts from different grape pomace. The images are at a scale of 100 µm (i) and 20 µm (ii).

Figure 2.

SEM images of microcapsules prepared with different coatings containing extracts from different grape pomace. The images are at a scale of 100 µm (i) and 20 µm (ii).

Figure 3.

XPRD diffractograms (A.) and DSC thermograms (B.) of the coatings and microcapsules containing the tested extracts.

Figure 3.

XPRD diffractograms (A.) and DSC thermograms (B.) of the coatings and microcapsules containing the tested extracts.

Figure 4.

The percentage of total phenolic compound (TPC) release from microcapsules produced with different coatings containing the tested extracts at the end of each gastrointestinal phase.

Figure 4.

The percentage of total phenolic compound (TPC) release from microcapsules produced with different coatings containing the tested extracts at the end of each gastrointestinal phase.

Figure 5.

TPC before (green line) and after each phase of simulated gastrointestinal digestion (bars) of non-encapsulated (control, C) and microencapsulated extract (SA; SA-GA; SA-GEL) of different grape pomace (A. – Cabernet Sauvignon; B. – Cabernet Franc; C. – Merlot) and the bioaccessibility index (BI) of TPC – D.

Figure 5.

TPC before (green line) and after each phase of simulated gastrointestinal digestion (bars) of non-encapsulated (control, C) and microencapsulated extract (SA; SA-GA; SA-GEL) of different grape pomace (A. – Cabernet Sauvignon; B. – Cabernet Franc; C. – Merlot) and the bioaccessibility index (BI) of TPC – D.

Figure 6.

Total flavonoid content (TFC) before (green line) and after each phase of simulated gastrointestinal digestion (bars) of non-encapsulated (control, C) and microencapsulated extracts of different grape pomace (A. – Cabernet Sauvignon; B. – Cabernet Franc; C. – Merlot) and the BI of TPC – D.

Figure 6.

Total flavonoid content (TFC) before (green line) and after each phase of simulated gastrointestinal digestion (bars) of non-encapsulated (control, C) and microencapsulated extracts of different grape pomace (A. – Cabernet Sauvignon; B. – Cabernet Franc; C. – Merlot) and the BI of TPC – D.

Figure 7.

Total extractable proanthocyanidins content (TPA) before (green line) and after each phase of simulated gastrointestinal digestion (bars) of non-encapsulated (control, C) and microencapsulated extracts of different grape pomace (A. – Cabernet Sauvignon; B. – Cabernet Franc; C. – Merlot) and the BI of TPA – D.

Figure 7.

Total extractable proanthocyanidins content (TPA) before (green line) and after each phase of simulated gastrointestinal digestion (bars) of non-encapsulated (control, C) and microencapsulated extracts of different grape pomace (A. – Cabernet Sauvignon; B. – Cabernet Franc; C. – Merlot) and the BI of TPA – D.

Table 1.

Estimated parameters of the mathematical models used to describe the release kinetics of total phenolic compounds (k1, kH, kHC, kKP – release constants for the corresponding model; n – diffusion exponent) from microcapsules containing extracts of Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc and Merlot grape pomace prepared with various coatings, and statistical criteria for model approximation success (R2adj – adjusted coefficient of determination, AIC – Akaike information criterion, MSC – model selection criterion)

Table 1.

Estimated parameters of the mathematical models used to describe the release kinetics of total phenolic compounds (k1, kH, kHC, kKP – release constants for the corresponding model; n – diffusion exponent) from microcapsules containing extracts of Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc and Merlot grape pomace prepared with various coatings, and statistical criteria for model approximation success (R2adj – adjusted coefficient of determination, AIC – Akaike information criterion, MSC – model selection criterion)

| Matematical models |

Release rate constants and statistical criteria of model approximation success |

| Cabernet Sauvignon |

Cabernet Franc |

Merlot |

| SA |

SA-GA |

SA-GEL |

SA |

SA-GA |

SA-GEL |

SA |

SA-GA |

SA-GEL |

First order

model

|

R2adj

|

0.855 |

0.779 |

0.784 |

0.937 |

0.916 |

0.759 |

0.929 |

0.899 |

0.765 |

| AIC |

123.918 |

130.018 |

128.235 |

113.001 |

117.112 |

131.785 |

114.313 |

119.575 |

133.050 |

| MSC |

1.421 |

0.813 |

1.225 |

2.272 |

1.921 |

1.115 |

2.140 |

1.846 |

1.198 |

| k1 |

0.031 |

0.041 |

0.008 |

0.042 |

0.042 |

0.010 |

0.036 |

0.029 |

0.009 |

Higuchi

model

|

R2adj

|

0.707 |

0.418 |

0.852 |

0.788 |

0.693 |

0.833 |

0.806 |

0.887 |

0.801 |

| AIC |

135.664 |

145.806 |

122.179 |

132.628 |

138.007 |

125.930 |

130.329 |

121.545 |

130.400 |

| MSC |

0.687 |

-0.174 |

1.603 |

1.046 |

0.615 |

1.481 |

1.139 |

1.723 |

1.363 |

| kH |

8.034 |

8.588 |

5.537 |

8.354 |

8.543 |

5.849 |

8.081 |

7.776 |

5.438 |

Hixson-Crowell

model

|

R2adj

|

0.006 |

0.362 |

0.721 |

0.744 |

0.639 |

0.727 |

0.772 |

0.816 |

0.721 |

| AIC |

0.679 |

147.195 |

132.287 |

135.667 |

140.634 |

133.734 |

132.901 |

129.430 |

135.799 |

| MSC |

137.111 |

-0.261 |

0.971 |

0.856 |

0.451 |

0.993 |

0.979 |

1.230 |

1.026 |

| kHC |

0.596 |

0.007 |

0.003 |

0.007 |

0.007 |

0.003 |

0.007 |

0.006 |

0.003 |

| Korsmeyer-Peppas model |

R2adj

|

0.913 |

0.886 |

0.741 |

0.872 |

0.873 |

0.688 |

0.939 |

0.974 |

0.652 |

| AIC |

117.081 |

119.646 |

132.021 |

122.718 |

122.287 |

136.782 |

112.575 |

98.676 |

140.272 |

| MSC |

1.848 |

1.461 |

0.988 |

1.665 |

1.598 |

0.803 |

2.249 |

3.152 |

0.746 |

| kKP |

20.189 |

35.888 |

10.596 |

18.357 |

26.022 |

12.519 |

21.047 |

17.533 |

7.605 |

| n |

0.319 |

0.204 |

0.341 |

0.356 |

0.272 |

0.313 |

0.316 |

0.335 |

0.391 |

Table 2.

BI (%) of the individual phenolic compounds of the control samples (C) and the microencapsulated extracts from different grape pomace (Cabernet Sauvignon (CS), Cabernet Franc (CF), Merlot (M)).

Table 2.

BI (%) of the individual phenolic compounds of the control samples (C) and the microencapsulated extracts from different grape pomace (Cabernet Sauvignon (CS), Cabernet Franc (CF), Merlot (M)).

| Phenolics |

Sample |

|

BI (%) |

| |

CS |

CF |

M |

| Phenolic acids |

Gallic acid |

C |

|

22.4 ± 0.8 |

108.8 ± 4.9 |

47.4 ± 0.3 |

| SA |

|

42.8 ± 3.7 |

36.9 ± 0.4 |

26.9 ± 0.7 |

| SA-GA |

|

117.0 ± 4.4 |

18.2 ± 0.0 |

222.6 ± 7.3 |

| SA-GEL |

|

215.5 ± 4.4 |

95.7 ± 0.4 |

218.5 ± 27.7 |

| 3,4-Dihydroxybenzoic acid |

C |

|

18.3 ± 0.6 |

70.6 ± 0.4 |

12.3 ± 0.2 |

| SA |

|

61.7 ± 2.9 |

67.1 ± 3.7 |

66.9 ± 1.2 |

| SA-GA |

|

77.0 ± 7.5 |

74.3 ± 2.8 |

157.8 ± 2.7 |

| SA-GEL |

|

226.6 ± 3.8 |

149.0 ± 3.8 |

236.8 ± 5.7 |

| Syringic acid |

C |

|

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| SA |

|

0.0 |

102.3 ± 0.6 |

38.8 ± 1.4 |

| SA-GA |

|

0.0 |

59.1 ± 3.7 |

537.8 ± 8.3 |

| SA-GEL |

|

0.0 |

0.0 |

160.2 ± 31.2 |

| Vanillic acid |

C |

|

22.9 ± 1.1 |

29.6 ± 0.0 |

22.1 ± 0.7 |

| SA |

|

53.0 ± 0.7 |

9.5 ± 0.8 |

49.3 ± 0.0 |

| SA-GA |

|

58.5 ± 2.0 |

22.6 ± 0.5 |

144.4 ± 4.1 |

| SA-GEL |

|

87.6 ± 2.8 |

24.0 ± 0.0 |

72.4 ± 4.6 |

| Ellagic acid |

C |

|

1.7 ± 0.1 |

1.6 ± 0.0 |

15.5 ± 0.5 |

| SA |

|

9.0 ± 0.4 |

0.0 |

70.2 ± 2.3 |

| SA-GA |

|

15.0 ± 1.8 |

7.9 ± 0.2 |

90.6 ± 7.7 |

| SA-GEL |

|

38.1 ± 0.2 |

8.4 ± 0.4 |

107.9 ± 18.5 |

|

o-Coumaric acid |

C |

|

78.7 ± 12.4 |

48.1 ± 0.3 |

61.7 ± 0.6 |

| SA |

|

191.0 ± 15.8 |

63.8 ± 3.0 |

57.8 ± 14.3 |

| SA-GA |

|

287.5 ± 37.2 |

19.5 ± 1.7 |

325.7 ± 6.6 |

| SA-GEL |

|

337.2 ± 31.5 |

54.8 ± 1.8 |

464.2 ± 66.8 |

|

p-Coumaric acid |

C |

|

87.0 ± 3.3 |

272.8 ± 49.0 |

65.4 ± 2.5 |

| SA |

|

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| SA-GA |

|

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| SA-GEL |

|

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| Flavanols |

Epicatechin |

C |

|

49.8 ± 1.1 |

0.0 |

15.6 ± 0.2 |

| SA |

|

57.2 ± 1.2 |

3.6 ± 0.1 |

0.0 |

| SA-GA |

|

97.5 ± 13.0 |

4.9 ± 0.8 |

53.5 ± 0.7 |

| SA-GEL |

|

139.2 ± 1.8 |

8.8 ± 0.4 |

83.6 ± 4.7 |

| Epicatechin gallate |

C |

|

116.8 ± 13.2 |

98.8 ± 0.2 |

88.7 ± 8.8 |

| SA |

|

113.6 ± 24.0 |

5.8 ± 0.3 |

367.8 ± 45.1 |

| SA-GA |

|

186.3 ± 28.5 |

36.7 ± 3.7 |

461.0 ± 25.8 |

| SA-GEL |

|

356.4 ± 10.2 |

19.6 ± 1.6 |

476.4 ± 68.3 |

| Gallocatechin gallate |

C |

|

251.4 ± 10.4 |

150.0 ± 4.7 |

234.0 ± 0.2 |

| SA |

|

692.4 ± 22.1 |

120.3 ± 0.5 |

580.7 ± 17.3 |

| SA-GA |

|

980.7 ± 17.9 |

197.6 ± 8.7 |

1342.7 ± 10.3 |

| SA-GEL |

|

2028.7 ± 15.0 |

348.2 ± 0.9 |

1970.9 ± 1.7 |

| Procyanidin B1 |

C |

|

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| SA |

|

71.2 ± 8.1 |

0.0 |

48.4 ± 4.5 |

| SA-GA |

|

130.4 ± 4.1 |

0.0 |

119.1 ± 7.1 |

| SA-GEL |

|

155.1 ± 6.2 |

0.0 |

135.4 ± 14.9 |

| Procyanidin B2 |

C |

|

0.0 |

0.00 |

0.0 |

| SA |

|

0.0 |

11.1 ± 1.5 |

0.0 |

| SA-GA |

|

0.0 |

9.7 ± 0.1 |

283.8 ± 10.5 |

| SA-GEL |

|

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| Flavonols |

Rutin |

C |

|

0.0 |

29.0 ± 2.8 |

0.0 |

| SA |

|

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| SA-GA |

|

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| SA-GEL |

|

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| Anthocyanins |

Oenin chloride |

C |

|

34.4 ± 2.8 |

32.7 ± 2.9 |

62.6 ± 4.5 |

| SA |

|

9.1 ± 1.4 |

4.7 ± 0.1 |

14.9 ± 0.2 |

| SA-GA |

|

28.0 ± 3.6 |

3.4 ± 0.3 |

40.1 ± 0.0 |

| SA-GEL |

|

63.9 ± 10.5 |

10.2 ± 0.7 |

44.7 ± 4.6 |

| Peonidin-3-O-glucoside chloride |

C |

|

24.7 ± 4.3 |

24.0 ± 2.9 |

42.4 ± 5.9 |

| SA |

|

0.0 |

2.5 ± 0.3 |

0.0 |

| SA-GA |

|

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| SA-GEL |

|

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).