Submitted:

08 January 2025

Posted:

08 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

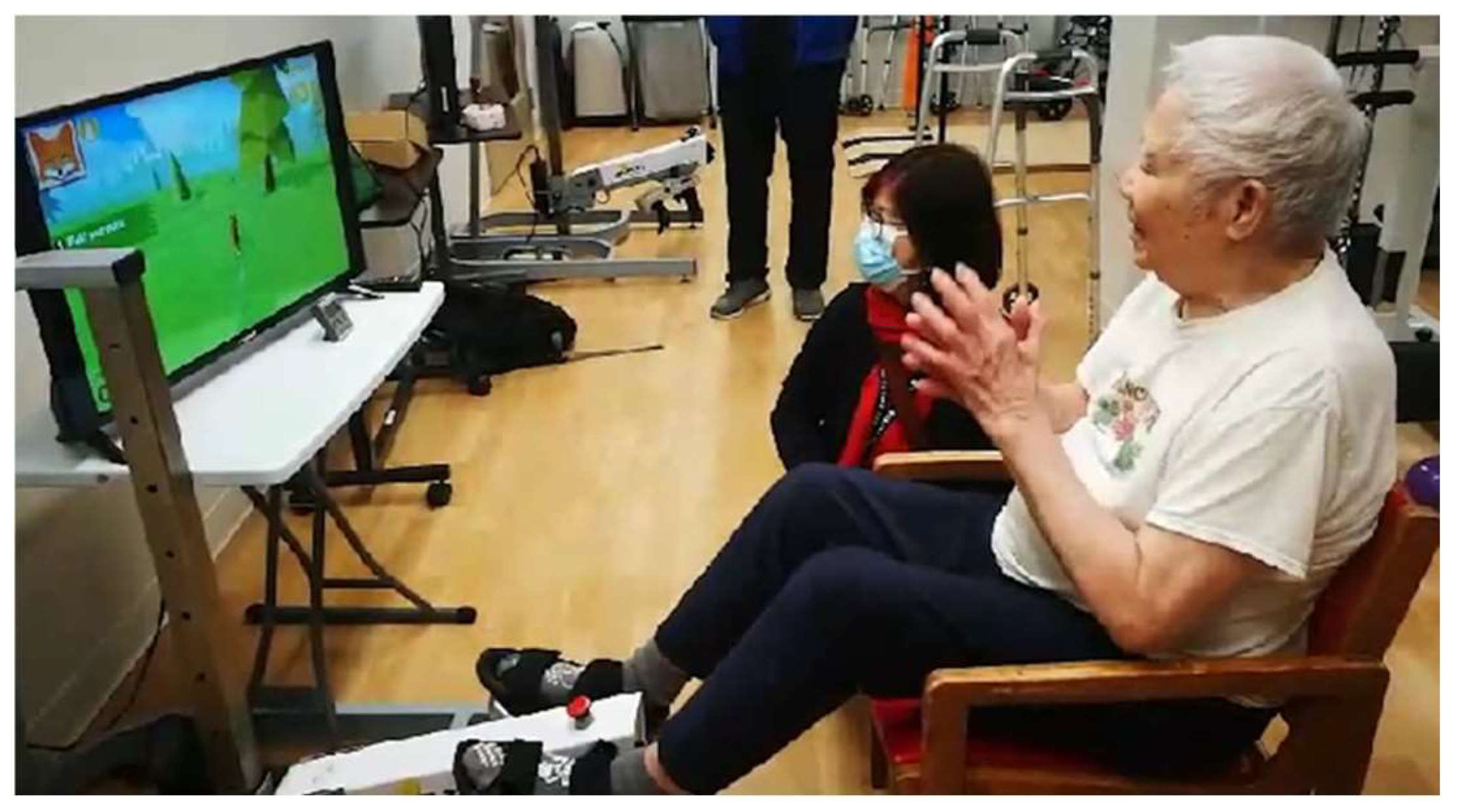

Background/Objectives: The aging population presents significant challenges to healthcare systems, with conditions like dementia severely affecting the quality of life for older adults, especially those in long-term care. Gamification has the potential to motivate older adults to engage in exercise by transforming physical activities into enjoyable experiences. Incorporating gaming elements in cycling exercises can foster a sense of interest and achievement, potentially improving health outcomes. This study aims to explore interdisciplinary staff perspectives on using a digital game to motivate cycling exercise among residents living with dementia in long-term care (LTC). Methods: This study applied a qualitative description design. Using an interpretive description approach, we conducted focus groups with 29 staff members, including recreational therapists, rehabilitation therapists, nurses, care aides, and leadership in an LTC home. The consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR) guided the data analysis to identify barriers and facilitators to adopting the digital game. Results: Engaging LTC residents living with dementia presents various challenges. Identified barriers to implementing the cycling game include cognitive and physical limitations, resistance to change, and intervention complexity. Frontline staff strategies include flexible invitations, social groups, making it fun, and building rapport. Success relies heavily on its cultural and individual relevance, along with strong support from leadership, peers, and family. Conclusions: Integrating gamification in exercise for older adults with dementia in LTC settings shows promise. However, addressing facilitators and barriers identified by staff is required. Successful implementation relies on tailoring interventions to meet residents' specific needs and preferences while addressing the identified challenges to maximize engagement and health benefits. This study adhered to the COREQ Checklist.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Study Settings and the Cycling Game

2.3. Sampling and Recruitment

2.4. Focus Group Questions

- (1)

- What are the facilitators for implementing the cycling program for residents?

- (2)

- What are the barriers to implementing the cycling program for residents?

- (3)

- What resources could support you in implementing the program?

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Data Analysis and Theoretical Framework

2.7. Ethical Considerations

2.8. Rigor

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Barriers and Enabling Strategies

3.2.1. Barrier: Cognitive and Physical Limitations

“I feel like for residents that might struggle with like visual aids, there might be some complications and problems for them [playing the cycling game].”(Group 3, John, nurse)

“The challenge is resident's conditions. When they do these exercises, their heart rate may increase. Their blood pressure will be impacted, which may be a worry among family members.”(Group 5, Ting, nurse)

“There is nothing that keeps residents’ focus on one thing.”(Group7, Mary, Leadership)

3.2.2. Barrier: Resistance to Change

“A lot of residents will need staff to encourage them to do exercises because sometimes they are kind of tired.”(Group 4, Lee, care aide)

“A lot of seniors who don’t have the energy and mood. A lot of time they don’t feel well. When they don’t even want to eat, how can you ask them to exercise?”(Group7, Martha, Leadership)

3.2.3. Barrier: Intervention Complexity

“The residents will have a lot more questions. Even though it's as simple as just pedaling... I have to explain what's on the screen [to the residents], such as to coordinate pedaling with the fox chasing a rabbit.”(Group 6, Scarlett, care aide)

3.3. Enabling Strategies: Flexible Invitations, Social Groups, Making It Fun, and Building Rapport

"Exercises can promote residents’ autonomy because exercises are supposed to train their muscles to promote well-being and a sense of control. Residents can do something to improve their conditions."(Group7, Jenny, Leadership)

“I feel like the cycling game is making them use more of their brain in a fun way.”(Group 3, Joe, nurse)

“Let this resident try it first, and the rest of the people can observe, and then they would join in.”(Group 4, Jen, nurse)

“The residents feel more engaged when they can relate themselves to the game. It will be nice to have culturally familiar elements in the gamified exercise, such as incorporating Mahjong-inspired visuals or themes, which can immediately capture residents’ interest and make the activity more engaging.”(Group 1, Winnie, recreational therapist)

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Practice Implications

- Collaborate: To encourage collaborative learning from interdisciplinary teams in long-term care settings on diverse perspectives on how to adapt and tailor interventions for diverse residents

- Say “Yes” to the game: To partner with industrial partners to simplify game content and incorporate culturally relevant content to motivate residents to say “yes” to participate in the exercise games (dementia-friendly design)

- Create a supportive environment: To engage family members, residents’ peers, and diverse staff in creating a supportive and inclusive environment to boost residents’ participation rates

- Learn about benefits: To promote the benefits of residents’ participation in the cycling games among staff and residents to enhance perceived benefits and fun aspects of the exercising games

- Identify needs: To conduct pre-game assessments to ensure residents with diverse physical and cognitive capacities can be well supported and participate in these gamified exercises meaningfully

- Negotiate financial support and resources: To ensure ongoing financial support and resources for the exercising program to sustain its implementation by nursing leaders

- Gain insights from future research: To explore further research on the long-term impacts of gamified exercise programs on residents’ physical and cognitive health outcomes by nurse researchers

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LTC | long-term care |

| CFIR | consolidated framework for implementation research |

| COREQ | Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research |

| APT | Active Passive Trainer |

| CTM | "Choose to Move" |

References

- Harper, S. Economic and Social Implications of Aging Societies. Science (1979) 2014, 346, 587–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowiak, E.; Kostka, T. Predictors of Quality of Life in Older People Living at Home and in Institutions. Aging Clin Exp Res 2004, 16, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angulo, J.; El Assar, M.; Álvarez-Bustos, A.; Rodríguez-Mañas, L. Physical Activity and Exercise: Strategies to Manage Frailty. Redox Biol 2020, 35, 101513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Northey, J.M.; Cherbuin, N.; Pumpa, K.L.; Smee, D.J.; Rattray, B. Exercise Interventions for Cognitive Function in Adults Older than 50: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Br J Sports Med 2018, 52, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papalia, G.F.; Papalia, R.; Diaz Balzani, L.A.; Torre, G.; Zampogna, B.; Vasta, S.; Fossati, C.; Alifano, A.M.; Denaro, V. The Effects of Physical Exercise on Balance and Prevention of Falls in Older People: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med 2020, 9, 2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruuskanen, J.M.; Ruoppila, I. Physical Activity and Psychological Well-Being among People Aged 65 to 84 Years. Age Ageing 1995, 24, 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, E.; Lewin, G.; Boldy, D. Barriers and Motivators to Being Physically Active for Older Home Care Clients. Phys Occup Ther Geriatr 2013, 31, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilgour, A.H.M.; Rutherford, M.; Higson, J.; Meredith, S.J.; McNiff, J.; Mitchell, S.; Wijayendran, A.; Lim, S.E.R.; Shenkin, S.D. Barriers and Motivators to Undertaking Physical Activity in Adults over 70—a Systematic Review of the Quantitative Literature. Age Ageing 2024, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, L.; Mann, J.; Battersby, L.; Parappilly, B.; Butcher, C.; Vicic, A. Gamification of Dementia Education in Hospitals: A Knowledge Translation Project. Dementia 2022, 21, 2619–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Li, R.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, S.; Ning, H. A Review on Serious Games for ADHD. ArXiv 2021, 2105. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco, T.B.F.; de Medeiros, C.S.P.; de Oliveira, V.H.B.; Vieira, E.R.; de Cavalcanti, F.A.C. Effectiveness of Exergames for Improving Mobility and Balance in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Syst Rev 2020, 9, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuah, N.M.; Ahmedy, F.; Gani, A.; Yong, L.N. A Survey on Gamification for Health Rehabilitation Care: Applications, Opportunities, and Open Challenges. Information 2021, 12, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinho, D.; Carneiro, J.; Corchado, J.M.; Marreiros, G. A Systematic Review of Gamification Techniques Applied to Elderly Care. Artif Intell Rev 2020, 53, 4863–4901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montayre, J.; Neville, S.; Dunn, I.; Shrestha-Ranjit, J.; Wright-St. Clair, V. What Makes Community-based Physical Activity Programs for Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Older Adults Effective? A Systematic Review. Australas J Ageing 2020, 39, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas-Lara, C.; Izquierdo, M.; Sáez de Asteasu, M.L.; Ramírez-Vélez, R.; Zambom-Ferraresi, F.; Zambom-Ferraresi, F.; Martínez-Velilla, N. Impact of Game-Based Interventions on Health-Related Outcomes in Hospitalized Older Patients: A Systematic Review. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2021, 22, 364–371.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivisto, J.; Malik, A. Gamification for Older Adults: A Systematic Literature Review. Gerontologist 2021, 61, e360–e372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, H.; Garcia-Agundez, A.; Müller, P.N.; Tregel, T.; Miede, A.; Göbel, S. Predicting Functional Performance via Classification of Lower Extremity Strength in Older Adults with Exergame-Collected Data. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2020, 17, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, C.H.; Biss, R.K.; Cooper, L.; Quan, A.M.L.; Matulis, H. Exergaming Platform for Older Adults Residing in Long-Term Care Homes: User-Centered Design, Development, and Usability Study. JMIR Serious Games 2021, 9, e22370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, J.; Mehrabi, S.; Li, Y.; Basharat, A.; Middleton, L.E.; Cao, S.; Barnett-Cowan, M.; Boger, J. Immersive Virtual Reality Exergames for Persons Living With Dementia: User-Centered Design Study as a Multistakeholder Team During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JMIR Serious Games 2022, 10, e29987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swinnen, N.; Vandenbulcke, M.; de Bruin, E.D.; Akkerman, R.; Stubbs, B.; Vancampfort, D. Exergaming for People with Major Neurocognitive Disorder: A Qualitative Study. Disabil Rehabil 2022, 44, 2044–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, F.M.; Huang, M.-Z.; Liao, L.-R.; Chung, R.C.; Kwok, T.C.; Pang, M.Y. Physical Exercise Improves Strength, Balance, Mobility, and Endurance in People with Cognitive Impairment and Dementia: A Systematic Review. J Physiother 2018, 64, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenborn, J. Meaningful Activities. In Dementia in Nursing Homes; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; pp. 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- van Alphen, H.J.M.; Hortobágyi, T.; van Heuvelen, M.J.G. Barriers, Motivators, and Facilitators of Physical Activity in Dementia Patients: A Systematic Review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2016, 66, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doornebosch, A.J.; Smaling, H.J.A.; Achterberg, W.P. Interprofessional Collaboration in Long-Term Care and Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2022, 23, 764–777.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorne, S. The Status and Use Value of Qualitative Research Findings. In Exploring Evidence-based Practice; Routledge, 2015; pp. 151–164.

- Krueger, R.A.; Casey, M.A. Focus Group Interviewing. In Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation; Wiley, 2015; pp. 506–534.

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): A 32-Item Checklist for Interviews and Focus Groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 28. Kelly, S.E. Qualitative Interviewing Techniques and Styles. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Methods in Health Research; SAGE Publications Ltd: 1 Oliver’s Yard, 55 City Road, London EC1Y 1SP United Kingdom, 2010; pp. 307–326. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meekes, W.; Stanmore, E.K. Motivational Determinants of Exergame Participation for Older People in Assisted Living Facilities: Mixed-Methods Study. J Med Internet Res 2017, 19, e238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, H.; Baumeister, J.; Bardal, E.M.; Vereijken, B.; Skjæret-Maroni, N. Exergaming in Older Adults: The Effects of Game Characteristics on Brain Activity and Physical Activity. Front Aging Neurosci 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sondell, A.; Rosendahl, E.; Sommar, J.N.; Littbrand, H.; Lundin-Olsson, L.; Lindelöf, N. Motivation to Participate in High-Intensity Functional Exercise Compared with a Social Activity in Older People with Dementia in Nursing Homes. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0206899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, A.L.; Wagner, D.R.; Heyward, V.H. Advanced Fitness Assessment and Exercise Prescription.; Human kinetics. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bechard, L.E.; McDougall, A.; Mitchell, C.; Regan, K.; Bergelt, M.; Dupuis, S.; Giangregorio, L.; Freeman, S.; Middleton, L.E. Dementia- and Mild Cognitive Impairment-Inclusive Exercise: Perceptions, Experiences, and Needs of Community Exercise Providers. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0238187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, V.; Franke, T.; McKay, H.; Tong, C.; Macdonald, H.; Sims-Gould, J. Adapting an Effective Health-Promoting Intervention—Choose to Move—for Chinese Older Adults in Canada. J Aging Phys Act 2024, 32, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrício, L.; Franco, M. A Systematic Literature Review about Team Diversity and Team Performance: Future Lines of Investigation. Adm Sci 2022, 12, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Number | Percentage |

| Roles | ||

| Recreation | 6 | 20.7% |

| Rehabilitation | 3 | 10.3% |

| Nurse | 10 | 34.5% |

| Care aide | 9 | 31.0% |

| Practice leader or director | 7 | 24.1% |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 5 | 17.2% |

| Female | 24 | 82.8% |

| Age group | ||

| 20-30 years | 4 | 13.8% |

| 30-40 years | 8 | 27.6% |

| 40-50 years | 7 | 24.1% |

| 50-60 years | 10 | 34.5% |

| Total | 29 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).