1. Introduction

INCONEL® 690 alloy, developed by Special Metals Corporation (USA) – a world leader in the development of high-tech nickel alloys and materials for their welding, is characterized by excellent resistance to many corrosive aqueous media and high temperature atmospheres. The increased chromium content provides high resistance to oxidizing acids (especially nitric and hydrofluoric acids), salts, as well as resistance to hydrogen sulphide corrosion at high temperatures. The high level of nickel imparts resistance to stress corrosion cracking in chloride-containing environments as well as to sodium hydroxide solutions. The properties of INCONEL® alloy 690 are useful for various applications involving nitric or nitric/hydrofluoric acid solutions. Examples are tail-gas reheaters used in nitric acid production and heating coils and tanks for nitric/hydrofluoric solutions used in pickling of stainless steels and reprocessing of nuclear fuels. The alloy’s resistance to sulphur-containing gases makes it an attractive material for such applications as coal-gasification units, burners and ducts for processing sulphuric acid, furnaces for petrochemical processing, recuperators, incinerators, and glass vitrification equipment for radioactive waste disposal. In addition, this alloy is characterized by a reduced cobalt content, which makes it possible to use it in the nuclear industry (due to the absence of induced radioactivity due to the formation of 60Co). In various types of high-temperature water, alloy 690 displays low corrosion rates and excellent resistance to stress-corrosion cracking. In addition to its corrosion resistance, alloy 690 has high strength, good metallurgical stability, and favourable fabrication characteristics. Thus, INCONEL® alloy 690 is widely used for steam generator tubes, baffles, tube sheets, and hardware in nuclear power generation.

One of the most effective and reliable technologies for joining metal parts is electric welding. As a welding material for INCONEL® 690 products, INCONEL® 52 alloy based on the Ni-Cr-Fe system was developed. This welding product is used for gas-tungsten arc and gas-metal welding and was developed to address the evolving requirements of the nuclear industry, offering enhanced resistance to stress corrosion cracking in both nuclear and pure water environments due to its higher chromium content. INCONEL® 52 produces corrosion-resistance overlays on most low-alloy and stainless steels. It can also be used in applications requiring resistance to oxidizing acids. These materials are effective for connecting different metals such as INCONEL® and INCOLOY® alloys, as well as carbon, low-alloy, and stainless steels, and are also suitable for overlaying on steel. INCONEL® 52 is well suited for automatic welding in industrial production conditions. However, it turned out that its characteristics are not entirely suitable for remote control welding, especially in repair conditions. The most significant factors preventing such use is a decrease in corrosion resistance and mechanical strength of the weld material due to contamination with aluminium and titanium oxides. These problems have been largely eliminated in subsequent generations of welding materials for INCONEL® 690 – INCONEL® 52M and INCONEL® 52MSS.

INCONEL® 52MSS represents the third generation of INCONEL® welding products, containing 30% chromium, specifically formulated to combat intergranular stress corrosion cracking in nuclear pure water environments. Incorporating 4% molybdenum and raising the niobium content to 2.2% provides INCONEL® Filler Metal 52MSS with superior resistance to ductility-dip cracking and cold cracking during the fabrication process. Due to its low aluminum and titanium content, it provides exceptionally ”clean” weld deposits, which are typically free from inclusions, oxides, and porosity. INCONEL® 52MSS is used for fabrication and repair of nuclear components and also demonstrates excellent resistance to root cracking. The good wetting and clean welds make INCONEL® 52MSS an ideal choice for remote controlled multi-pass welds in radioactively „hot” repair situations.

Another known problem that significantly reduces the performance characteristics of welded joints made using INCONEL® Filler Metal 52 is the presence of the so-called high-temperature plasticity dip (reduction in relative elongation) in the temperature range of 1000-1200 K, which coincides with the temperature range of hot crack formation. However, for the improved Filler Metal INCONEL® 52MSS, this problem remains unstudied. The purpose of this work was to study in detail the structural, physical and mechanical properties of both INCONEL® 52 and INCONEL® 52MSS, especially in the area of possible deterioration in performance properties.

2. Methods and Experimental Results

Special specimens were developed to simulate conditions of deformation of the deposited metal of multi-pass welded joints in real structures. The samples for the studies were obtained by automatic multi-pass overlaying in an atmosphere of purified argon using a non-consumable tungsten electrode argon-arc welding (

Tungsten Inert Gas - TIG) of the studied alloy on a substrate made of INCONEL® 690 alloy (the chemical composition of INCONEL® 690 alloy is given in

Table 1).

The microstructure of INCONEL® 690 is characterized by fine grains, lacking texture, and comprising austenitic grains along with annealing twins found within the grains. There were no significant amounts of extraneous phases or boundary precipitates observed.

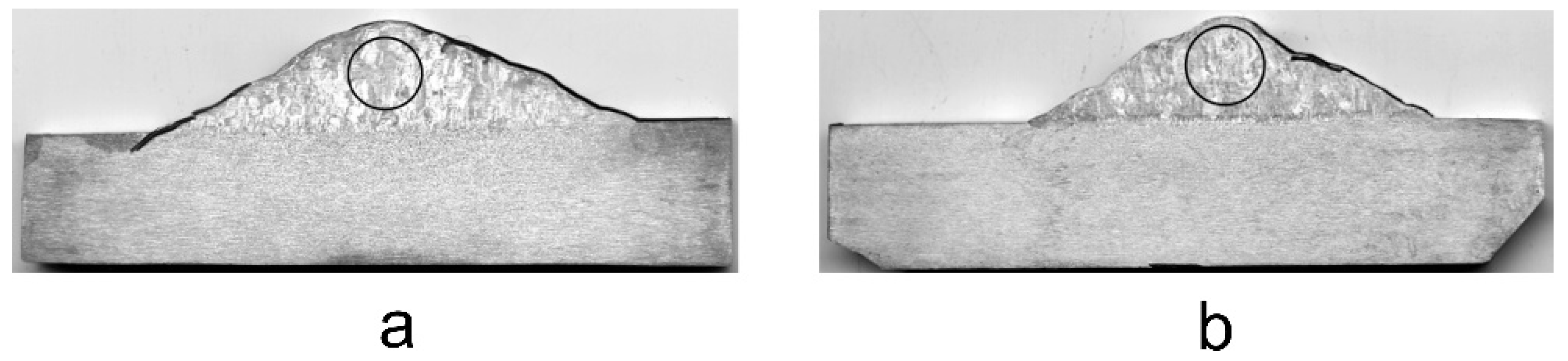

The appearance of the samples after TIG overlaying on a substrate of INCONEL® 690 is shown in

Figure 1.

The appearance of transverse sections of the surfacing after etching in acid is shown in

Figure 2.

From the obtained massive ingots, samples for research were cut out by electric spark cutting followed by mechanical grinding and polishing. The chemical composition of the studied alloys is given in

Table 2.

We studied the structural and mechanical properties of INCONEL® 52 and INCONEL® 52MSS alloys over a wide temperature range, and also obtained temperature dependences of acoustic absorption (logarithmic decrement of oscillations ) and dynamic Young's modulus .

The structural characteristics of the studied samples were investigated using various methods of optical and electron microscopy.

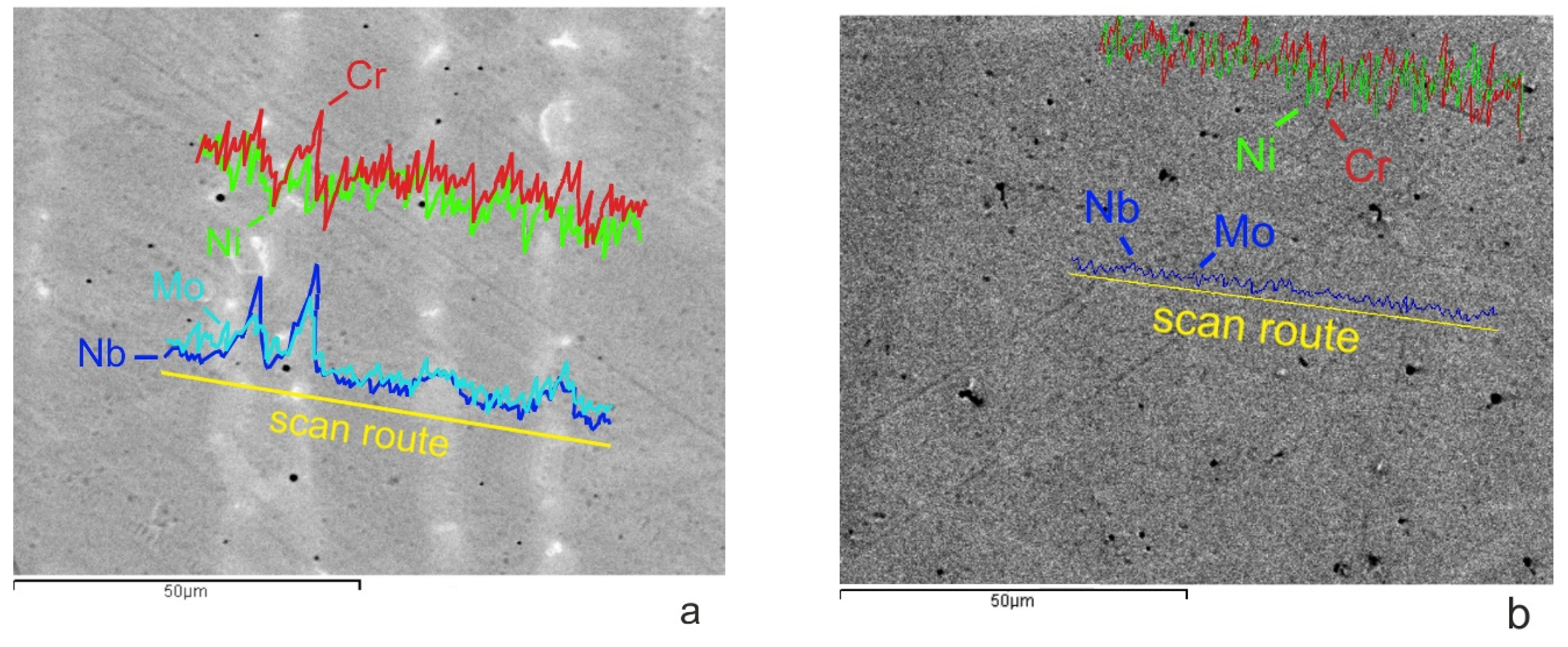

In samples of INCONEL® 52MSS alloy, significant chemical heterogeneity is observed in niobium and molybdenum (see

Figure 3a), but not observed in INCONEL® 52 alloy (see

Figure 3b).

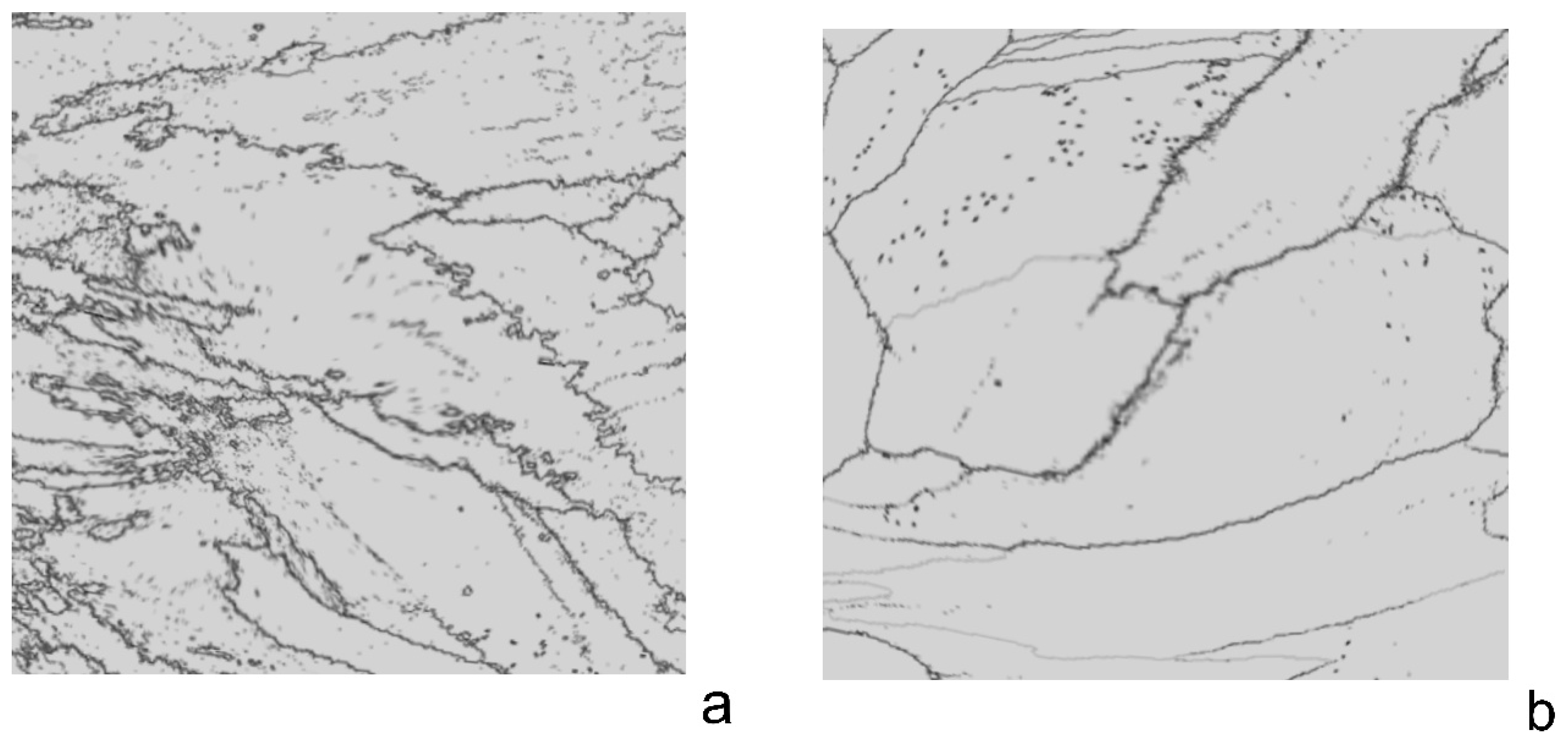

Grain boundaries analysis by the electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) method showed (see

Figure 4), that in the INCONEL® 52 alloy almost smooth grain boundaries are observed, which indicates no effective pinning. At the same time, in the INCONEL® 52MSS alloy tortuous grain boundaries are observed, and effective pinning takes place.

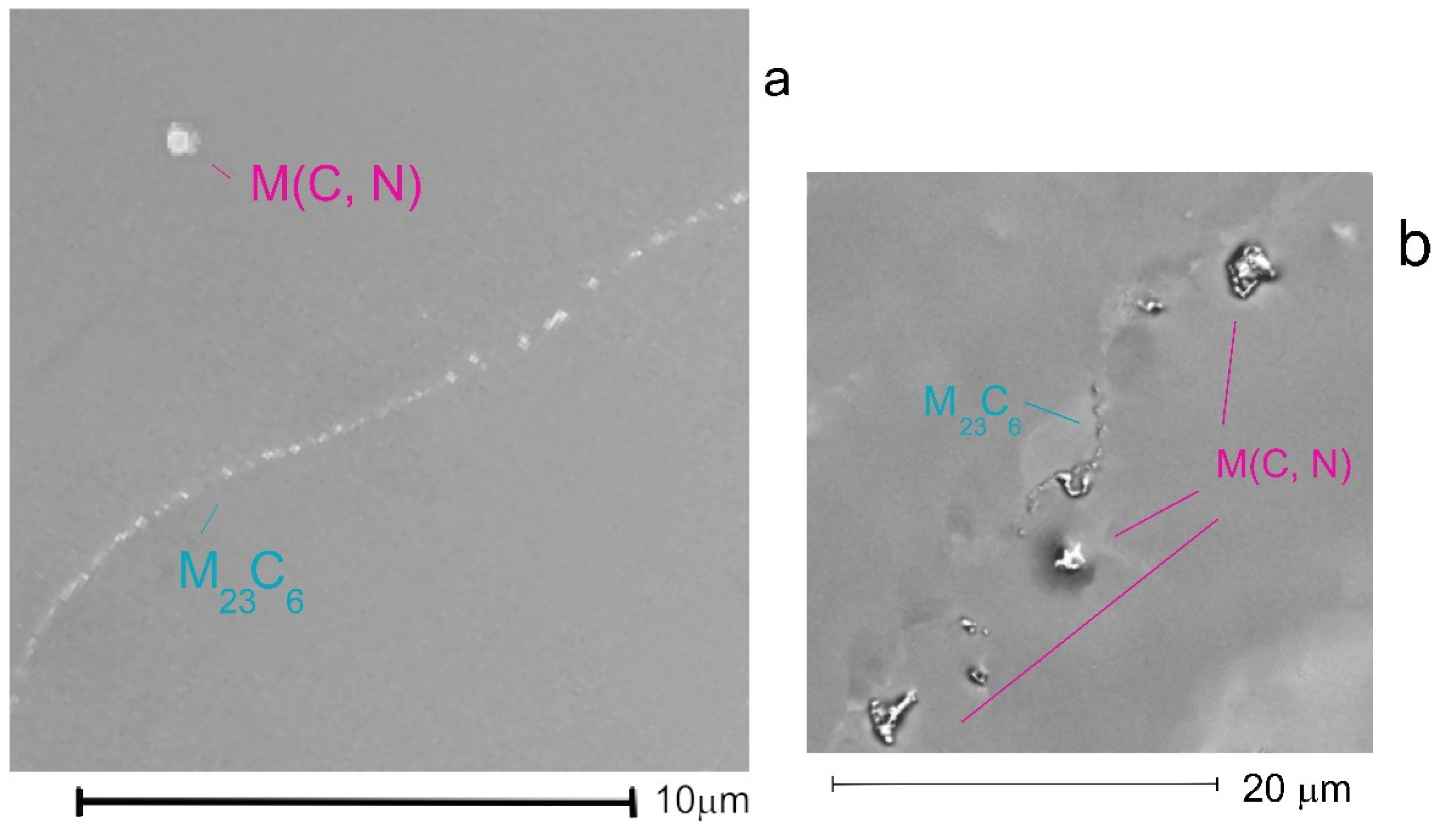

The grain boundary regions in INCONEL® 52 alloy are enriched in niobium and molybdenum with the release of niobium carbide. As a result, carbide and nitrite precipitates precipitates are observed in the alloy structure (see

Figure 5).

The straight grain boundaries of INCONEL® 52 alloy were populated with small, Cr-rich M23C6 carbides. M23C6 carbide precipitates are formed after solidification of the alloy, at a lower temperature than NbC (MC) and do not make a noticeable contribution to the pinning of grain boundaries. M(C, N) precipitates are distributed throughout the entire volume of the alloy. NbC is formed at the end of solidification of the alloy, before the formation of grain boundaries; and NbC effectively pins the migration of grain boundaries, which leads to the formation of tortuous boundaries and blocking of grains.

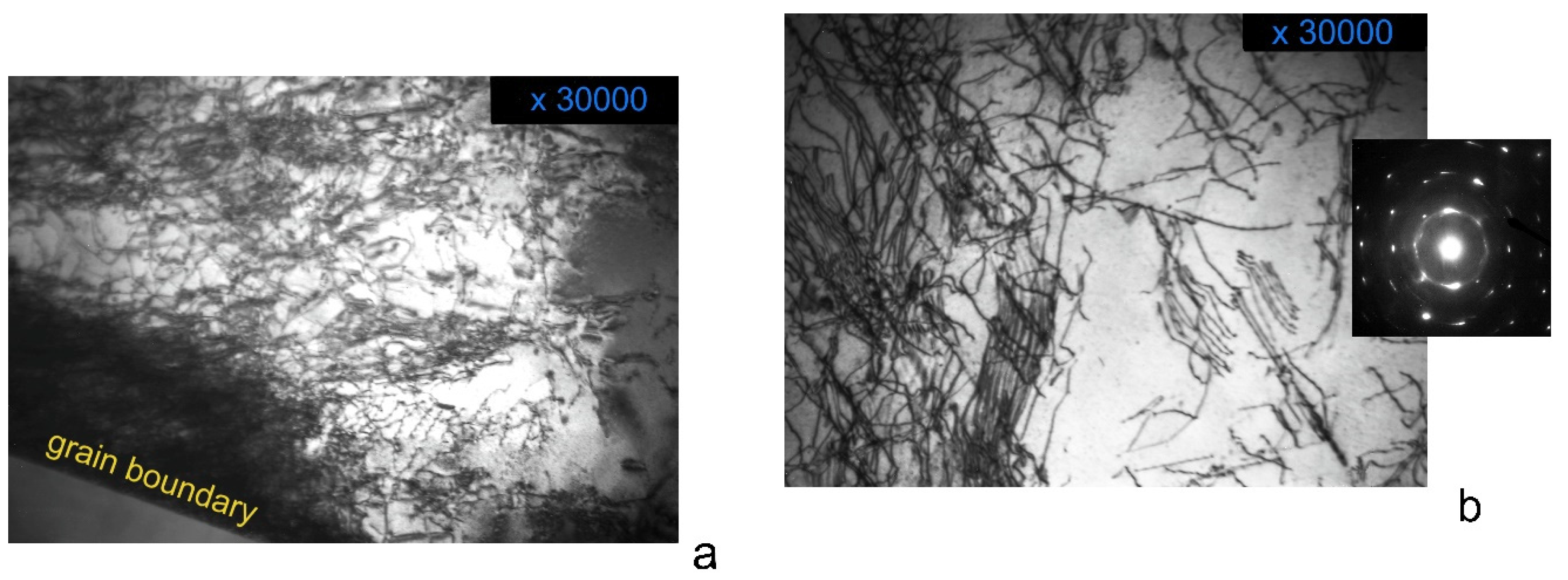

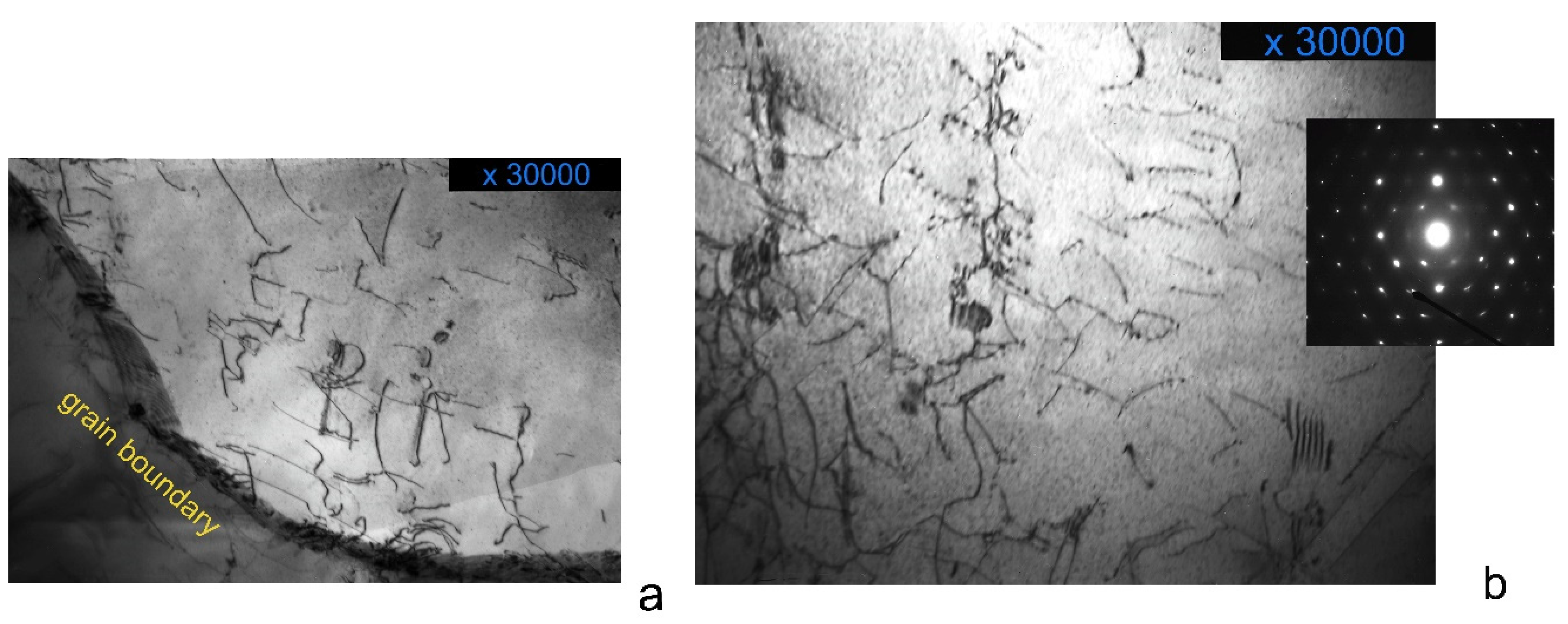

Dislocation density in grain volume in INCONEL® 52 alloy is~ 4·10

10 сm

-2, and in INCONEL® 52MSS is ~ 5·10

8 сm

-2 (see.

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). In INCONEL® 52, a significant increase in dislocation density is observed during the transition from the grain volume to the boundary (~ 2·10

11 cm

-2), which leads to a sharp gradient of local internal stresses

. At the same time, in INCONEL® 52MSS the distribution of local internal stresses is almost uniform, which can be explained by the redistribution of internal stresses along the grain boundaries in the process of diffusion of defects to the grain boundaries (blocks) [

1].

The technique for studying the mechanical properties of this alloy using the method of active constant rate deformation is described in detail in [

2,

3]. The samples were deformed by compression at a given relative strain rate

at different temperatures

. The magnitude of the deforming stresses

was determined as the ratio of the load to the initial cross-sectional area of the sample; the magnitude of the deformation

was calculated as the ratio of the change in the length of the sample during deformation to its initial length.

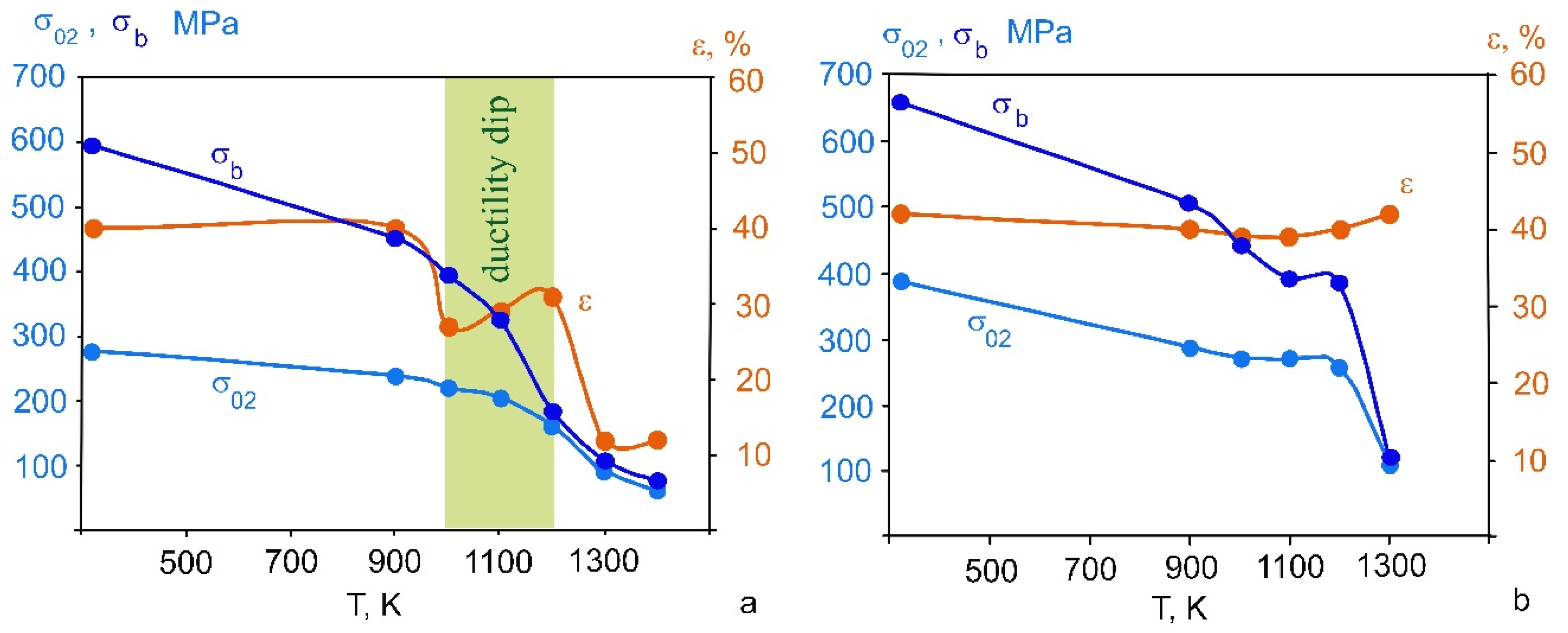

In the INCONEL® 52 alloy, a ductility dip occurs, where the relative elongation ε have reduced values, with a maximum in the temperature range of 1000-1200 K (see

Figure 8a). This temperature range coincides with the temperature range of the plasticity dip during hot cracking. At the same time, this plasticity dip is not observed in the INCONEL® 52MSS alloy (see

Figure 8b).

Measurements of acoustic characteristics were performed in the amplitude-independent deformation region using two different methods of mechanical spectroscopy in two mutually overlapping temperature ranges: 1. the temperature range of 77-390 K by the method of forced resonant bending vibrations of a cantilever-mounted sample [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8] at a frequency of 400 Hz; 2. in the temperature range of 293-1200 K by the method of oscillations of the inverse torsional pendulum [

4,

5] at a frequency of 0.4 Hz. In these experiments under the influence of the external cyclic force, forced vibrations of the sample under study were excited with a variation of its frequency

f near the first resonant frequency of mechanical vibrations

fr. As a result, an alternating stress

acted on the sample of material with a cyclic frequency

, and the sample under study experienced a small cyclic deformation

, which, due to the strain viscosity of the sample material, lagged in phase from the applied stress by an angle

φ. In this case,

tgφ characterizes the absorption of the energy of mechanical vibrations in

the material under study, and the dynamic modulus of elasticity is determined by

the deformation component that is in phase with the applied stress. A detailed description

of the method for measuring acoustic absorption (internal friction)

and dynamic Young's modulus

in these experiments is given in [

4,

5,

8].

These methods are characterized by low intensity of impact on the studied samples (elastic-plastic deformations with amplitude of

ε0 ~10

-7) and are non-destructive research methods [

9]. At the same time, acoustic spectroscopy has high structural sensitivity and allows studying the subtle mechanisms that control the strength and plasticity of materials.

During the acoustic measurements, the temperature was measured and stabilized with an accuracy of 50 mK. The rate of temperature change was ~ 1 K/min.

All measurements were performed in the absence of an external magnetic field.

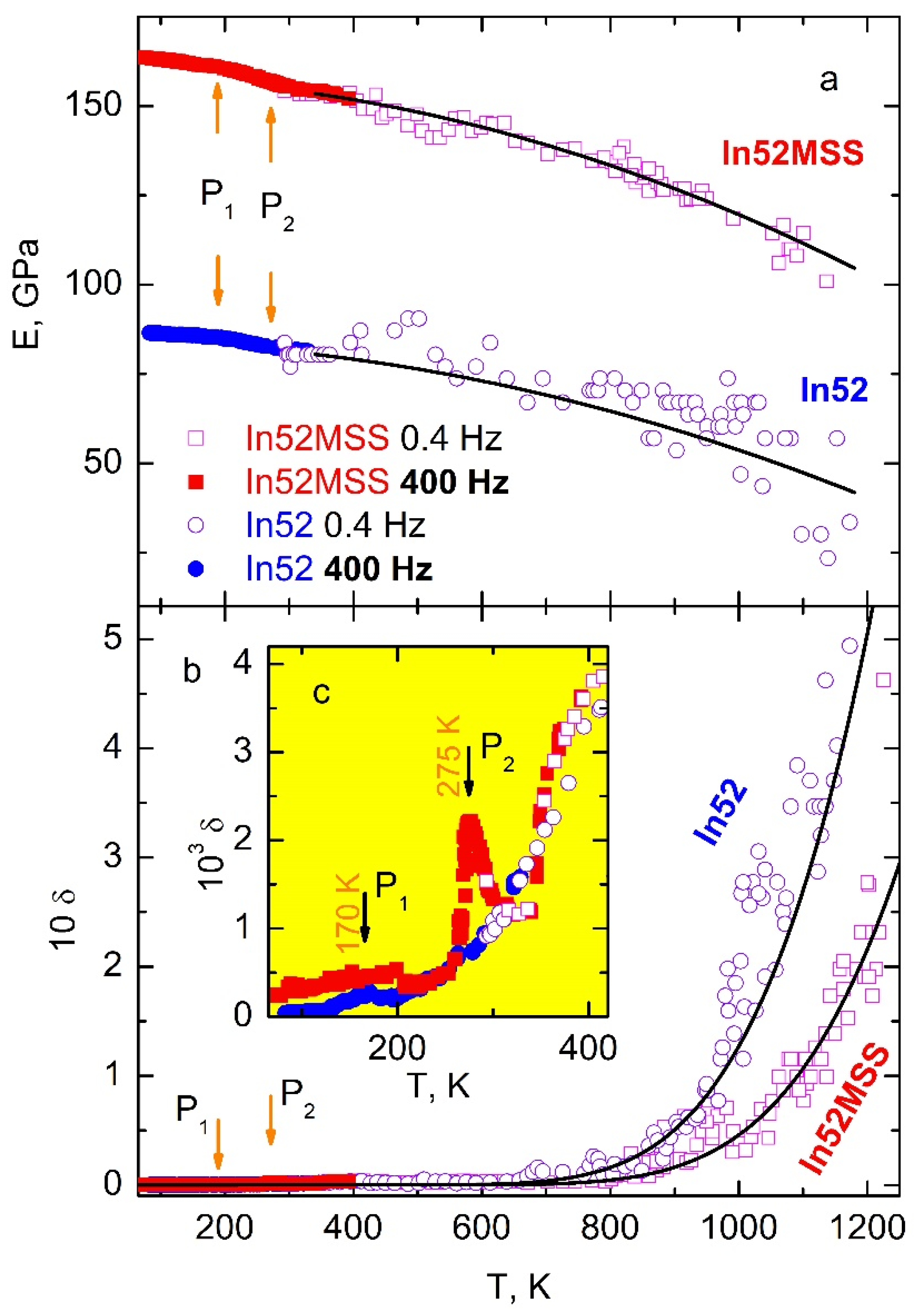

The results of the acoustic measurements are shown in

Figure 9. It should be noted that the measurement results obtained by two different methods are in good agreement in the overlapping temperature range. It was found that with increasing temperature, the dynamic Young's modulus of the samples decreases monotonically, while acoustic absorption

increases. Moreover, the dynamic Young's modulus

E(

T) in INCONEL® 52MSS alloy is twice as high as in INCONEL® 52 alloy over the entire temperature range, which, according to [

10], is most likely due not only to the increased dislocation density in INCONEL® 52 alloy, but to more efficient dislocation pinning in INCONEL® 52MSS alloy. The general trend of the temperature dependence of the dynamic Young's modulus

is satisfactorily described under the assumption of an additive contribution of the phonon and electron components [

11] (solid lines in

Figure 9a):

- adiabatic modulus of elasticity of an ideal crystal at T→0 К, - thermal phonon modulus defect; - modulus defect caused by thermal motion of conduction electrons; , and ΘD is the Debye temperature.

The absence of features characteristic of structural-phase transformations in the obtained temperature dependences of the acoustic properties indicates the stability of the structure of the studied alloys in the investigated temperature range.

It has been established that the behaviour of the high-temperature acoustic absorption background is well described within the framework of the assumption of thermally activated release of dislocation lines with kinks from pinning points [

5,

13,

14] (solid lines in

Figure 9b). Within the framework of this theory, it is assumed that the behaviour of the high-temperature acoustic absorption background

can be described by the relation:

where

has the meaning of the activation energy of detachment of dislocations from pinning points, and the pre-exponential factor

is proportional to the effective length of dislocation segments.

It has been experimentally established that in the INCONEL® 52MSS alloy, more effective pinning points of dislocation segments operate with a detachment activation energy eV, while in the INCONEL 52 eV.

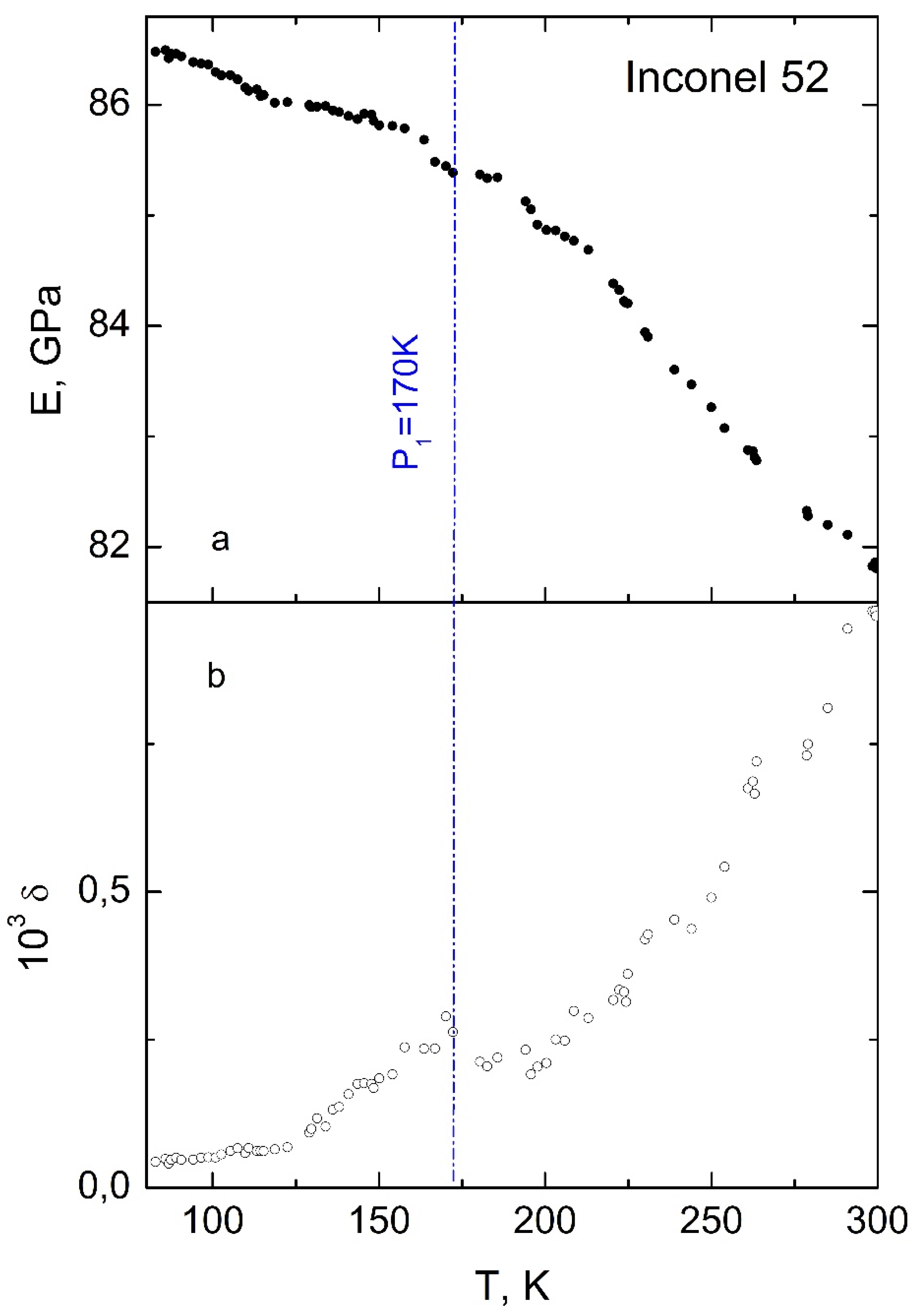

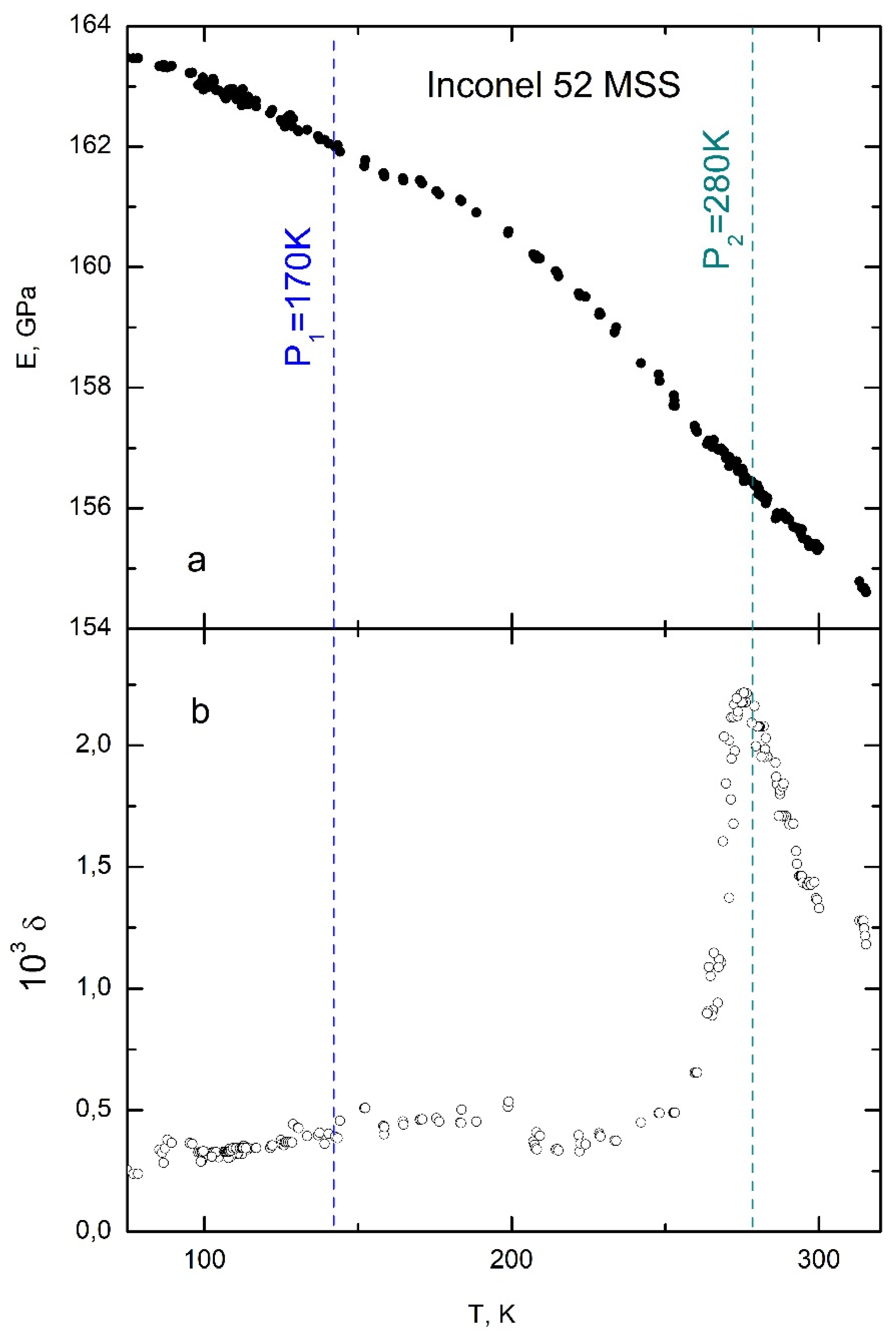

At a temperature of ~ 170 K, in the samples of INCONEL® 52 and INCONEL® 52MSS alloys, the absorption peak P

1 is observed on the temperature dependence of the logarithmic decrement of oscillations

(see

Figure 10 and

Figure 11); in addition, in the INCONEL® 52MSS alloy, at a temperature of ~ 280 K, the absorption peak P

2 is observed (see

Figure 11). These peaks correspond to characteristic inflections in the dependences of the dynamic Young's modulus

, which indicates their relaxation nature.

The application of the method of analysis of acoustic relaxation resonances described in detail in [

12] made it possible to establish the activation parameters of the processes responsible for the appearance of absorption peaks P

1 (activation energy

≈ 0.27V and effective attempt period

≈ 10

-11 s) and P

2 (activation energy

≈ 0.56 eV and effective attempt period

≈ 10

-13 s). The characteristic values of the activation parameters, as well as the fact that P

2 is observed only in the INCONEL® 52MSS alloy, allow us to associate this relaxation process with the appearance of new defects in the structure of this alloy, which can act as stoppers effectively interacting with dislocations. Carbide and nitrite precipitates can act as such defects appearing in the structure of the INCONEL® 52MSS alloy, but absent in the INCONEL® 52 alloy. The microscopic mechanisms responsible for the appearance of the P

1 peak currently remain unclear.

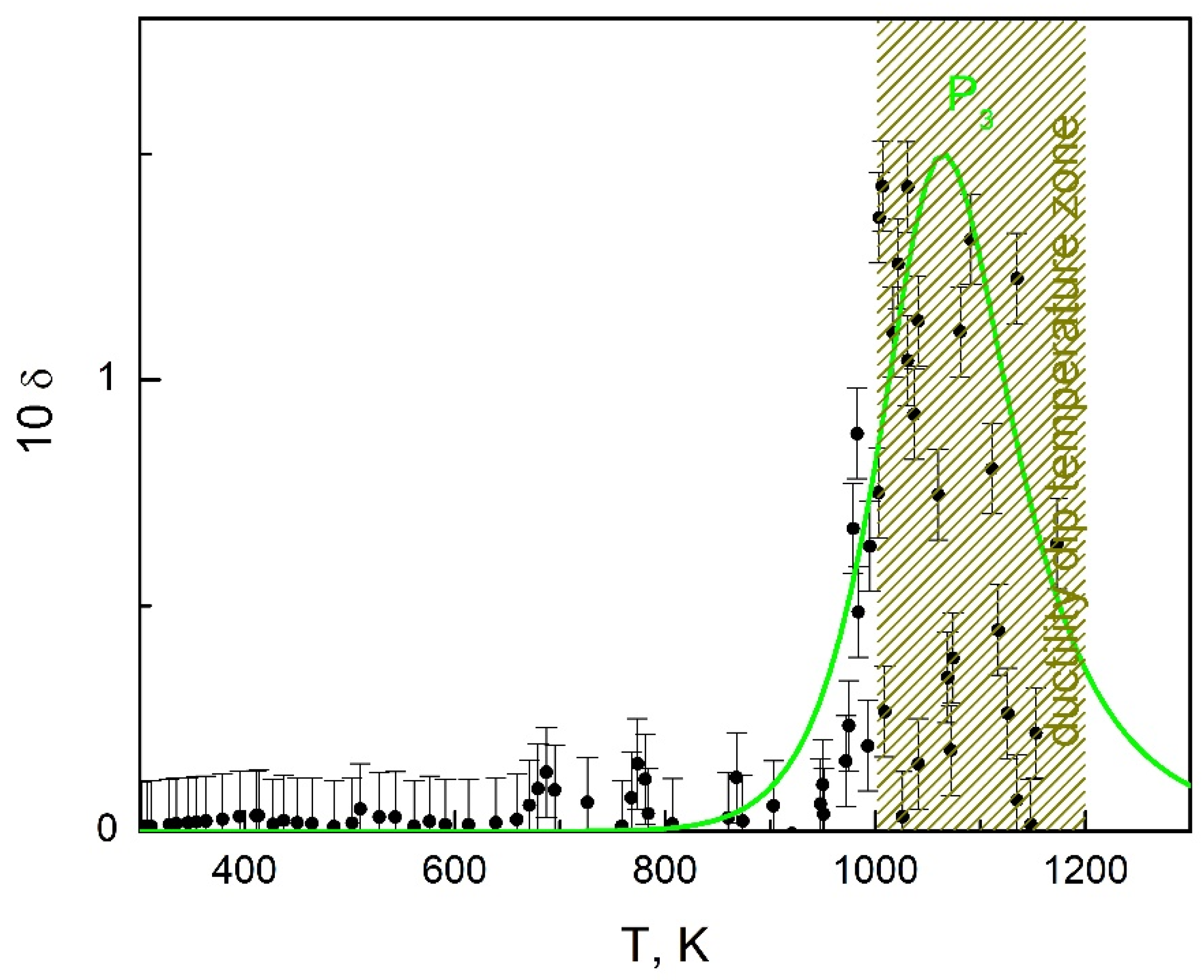

In addition, in the temperature range of 1000-1200 K, a wide diffuse peak of acoustic absorption P

3 is observed in the INCONEL® 52 alloy (see

Figure 12). It is noteworthy that P

3 is not observed in the INCONEL® 52MSS alloy, and the temperature range of its localization coincides with the temperature range of the plasticity dip. This fact allows us to associate P

3 with the emergence of favourable conditions for efficient pinning by precipitates.

Thus, a correlation of mechanical and acoustic properties is observed, which can be used to analyse the phenomenon of plasticity failure by non-destructive methods.

Figure 1.

The surface of the sample after the multipass welding seams, made TIG welding in an atmosphere of purified argon: a - wire Filler Metal INCONEL® 52 alloy; b - wire Filler Metal INCONEL® 52MSS alloy.

Figure 1.

The surface of the sample after the multipass welding seams, made TIG welding in an atmosphere of purified argon: a - wire Filler Metal INCONEL® 52 alloy; b - wire Filler Metal INCONEL® 52MSS alloy.

Figure 2.

Macrostructure multilayer deposition on a substrate of INCONEL® 690: a - Filler Metal INCONEL® 52 alloy; b - Filler Metal INCONEL® 52MSS alloy. Around the place indicated cutting blanks for research.

Figure 2.

Macrostructure multilayer deposition on a substrate of INCONEL® 690: a - Filler Metal INCONEL® 52 alloy; b - Filler Metal INCONEL® 52MSS alloy. Around the place indicated cutting blanks for research.

Figure 3.

Elemental microanalysis of INCONEL® 52 and INCONEL® 52MSS alloys: a - Filler Metal INCONEL® 52MSS alloy, chemical heterogeneity of niobium and molybdenum it is observed; b - Filler Metal INCONEL® 52 alloy, chemical homogeneity of niobium and molybdenum is observed.

Figure 3.

Elemental microanalysis of INCONEL® 52 and INCONEL® 52MSS alloys: a - Filler Metal INCONEL® 52MSS alloy, chemical heterogeneity of niobium and molybdenum it is observed; b - Filler Metal INCONEL® 52 alloy, chemical homogeneity of niobium and molybdenum is observed.

Figure 4.

Electron backscattered diffraction (EBSD) pattern of INCONEL® 52 and INCONEL® 52MSS alloys: a - serpentine grain boundaries in INCONEL® 52MSS, effective pinning is observed; b – the nearly straight, almost smooth grain boundaries in INCONEL® 52, effective pinning is absent.

Figure 4.

Electron backscattered diffraction (EBSD) pattern of INCONEL® 52 and INCONEL® 52MSS alloys: a - serpentine grain boundaries in INCONEL® 52MSS, effective pinning is observed; b – the nearly straight, almost smooth grain boundaries in INCONEL® 52, effective pinning is absent.

Figure 5.

Backscattered electron SEM image of INCONEL® 52 and INCONEL® 52MSS alloys: a - INCONEL® 52 exhibits long, straight grain boundaries with nearly continuous M23C6 carbide precipitates, which are undesirable; b - INCONEL® 52MSS shows M(C, N) precipitates and M23C6 carbides along of the grain boundaries, with noticeable grain boundary pinning due to large intragranular precipitates.

Figure 5.

Backscattered electron SEM image of INCONEL® 52 and INCONEL® 52MSS alloys: a - INCONEL® 52 exhibits long, straight grain boundaries with nearly continuous M23C6 carbide precipitates, which are undesirable; b - INCONEL® 52MSS shows M(C, N) precipitates and M23C6 carbides along of the grain boundaries, with noticeable grain boundary pinning due to large intragranular precipitates.

Figure 6.

The distribution of dislocations in the alloy INCONEL® 52 according electron diffraction: a - the border zone; b - in the grain.

Figure 6.

The distribution of dislocations in the alloy INCONEL® 52 according electron diffraction: a - the border zone; b - in the grain.

Figure 7.

The distribution of dislocations in the alloy INCONEL® 52MSS according electron diffraction: a - the border zone; b - in the grain.

Figure 7.

The distribution of dislocations in the alloy INCONEL® 52MSS according electron diffraction: a - the border zone; b - in the grain.

Figure 8.

The temperature dependence of the strength and plasticity of INCONEL® 52 and INCONEL® 52MSS alloys [

3]: a - INCONEL® 52; b - INCONEL® 52MSS. σ

02 - yield strength, σ

b - the ultimate strength, ε - maximum relative elongation (before the onset of irreversible deformation).

Figure 8.

The temperature dependence of the strength and plasticity of INCONEL® 52 and INCONEL® 52MSS alloys [

3]: a - INCONEL® 52; b - INCONEL® 52MSS. σ

02 - yield strength, σ

b - the ultimate strength, ε - maximum relative elongation (before the onset of irreversible deformation).

Figure 9.

The temperature dependences of the dynamic Young's modulus E (T) and logarithmic decrement δ (T) of the INCONEL® 52 and INCONEL® 52MSS alloys in the entire studied temperature range: a - dynamic Young's modulus E (T), solid line is theoretical dependence (1); b - logarithmic decrement δ (T), solid line is background absorption (2); c - temperature dependences of acoustic absorption in the region of peaks P1 and P2.

Figure 9.

The temperature dependences of the dynamic Young's modulus E (T) and logarithmic decrement δ (T) of the INCONEL® 52 and INCONEL® 52MSS alloys in the entire studied temperature range: a - dynamic Young's modulus E (T), solid line is theoretical dependence (1); b - logarithmic decrement δ (T), solid line is background absorption (2); c - temperature dependences of acoustic absorption in the region of peaks P1 and P2.

Figure 10.

The temperature dependences of the acoustic properties of the INCONEL® 52 alloy in the region of P1 peak: a - dynamic Young's modulus E (T); b - logarithmic decrement δ (T).

Figure 10.

The temperature dependences of the acoustic properties of the INCONEL® 52 alloy in the region of P1 peak: a - dynamic Young's modulus E (T); b - logarithmic decrement δ (T).

Figure 11.

The temperature dependences of the acoustic properties of the INCONEL® 52MSS alloy in the region of P1 and P2 peaks: a - dynamic Young's modulus E (T); b - logarithmic decrement δ (T).

Figure 11.

The temperature dependences of the acoustic properties of the INCONEL® 52MSS alloy in the region of P1 and P2 peaks: a - dynamic Young's modulus E (T); b - logarithmic decrement δ (T).

Figure 12.

Temperature dependences of acoustic absorption of INCONEL® 52M alloy in the temperature region of plasticity dip after subtraction of high-temperature background absorption (2). Solid line is the analytical approximation of absorption peak P3.

Figure 12.

Temperature dependences of acoustic absorption of INCONEL® 52M alloy in the temperature region of plasticity dip after subtraction of high-temperature background absorption (2). Solid line is the analytical approximation of absorption peak P3.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of INCONEL® alloy 690.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of INCONEL® alloy 690.

| Contents of elements, wt. % |

|---|

| C |

Mn |

Ni |

Cr |

Fe |

S |

Si |

Сu |

| 0.05 |

0.5 |

58 |

27-31 |

7-11 |

0.015 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

Table 2.

Chemical composition of the studied alloys INCONEL® 52 and INCONEL® 52MSS.

Table 2.

Chemical composition of the studied alloys INCONEL® 52 and INCONEL® 52MSS.

| Contents of elements, wt. % |

Alloy |

| INCONEL® 52 |

INCONEL® 52MSS |

| C |

0.026 |

0.023 |

| Mn |

0.24 |

0.31 |

| Ni |

58.82 |

base |

| Cr |

28.91 |

29.49 |

| Fe |

10.53 |

8.49 |

| Nb |

0.03 |

2.51 |

| Mo |

0.04 |

3.51 |

| S |

<0.001 |

0.0005 |

| P |

<0.004 |

0.004 |

| Ti |

0.55 |

0.18 |

| Al |

0.66 |

0.13 |

| Si |

0.15 |

0.11 |

| Сu |

0.02 |

0.05 |

| Mo-Nb |

0.07 |

6.10 |